Wave energy extraction technology has been developed over decades, given its advantages of high wave energy density and strong persistence. To surmount the shortcomings of the high cost and inconvenience of installation and maintenance of wave energy converters (WECs), the integration of WECs with existing coastal and offshore structures has proven to be an efficient approach (Pérez-Collazo et al., 2015; Mustapa et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2019; Renzi et al., 2021).

The synergy between the breakwater and WECs, such as oscillating floating buoys, oscillating water columns (OWCs), and overtopping devices, has attracted considerable attention, given the potential advantages of infrastructure sharing. Ning et al. (2017) and Zhao et al. (2017) analytically investigated the hydrodynamic performance of using one isolated and dual oscillating pontoon as a WEC-floating breakwater integration system. They found that the dual-pontoon system has a better overall performance than the one-pontoon system when the total volume is fixed; the hydrodynamic interaction between the two pontoons is an important factor in wave energy extraction. Zhang et al. (2020) investigated the effects of wave reflection on an oscillating WEC deployed in front of a vertical solid wall. They found that the wave reflection can greatly modify the wave energy extraction performance of the WEC. Furthermore, they particularly examined the effects of water column resonance between the WEC and the rear wall. Similar results were also drawn by Kara (2021, 2022) when the wave energy extraction performance of an array of floating cylindrical WEC arranged in front of a vertical solid wall was examined using an in-house numerical tool. Zhang et al. (2021) used the Star-CCM+ software to assess the effects of gap resonance on the performance of an integration system consisting of an oscillating WEC and a floating breakwater. They found that the piston-mode gap resonance can greatly improve the wave energy extraction efficiency. The particular integration system consisting of rectangular oscillating WECs and the comb-type breakwater was investigated by Zhao et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (2022) through a series of theoretical analyses and physical experiments. The research on the oscillating WEC-breakwater integration system includes, but is not limited to, the aforementioned studies. In addition, the utilization of the OWC-breakwater integration system has been explored and investigated widely. Relative studies mainly focused on, but were not limited to, the effects of integrating OWC devices with coastal breakwaters on wave attenuation and wave energy extraction performance (Simonetti and Cappietti, 2021; Zhao et al., 2022; Mayon et al., 2023), the effects of multichamber OWCs (Gang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023), and array effects of multiple OWCs (Xu and Huang, 2018; Zheng et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2023).

In addition to the WEC-breakwater integration system, the hybrid WEC system, which comprises different types of WECs, has aroused wide interest. The hydrodynamic interaction between different types of WECs is expected to improve the wave energy extraction efficiency. Zheng and Zhang (2018) investigated the wave energy extraction performance of a hybrid WEC consisting of an oscillating floating box and a floating OWC by using a two-dimensional (2D) analytical model. They found that the wave energy efficiency of the hybrid WEC is higher than the summation of that of an isolated oscillating WEC and a floating OWC. Then, Cui et al. (2021) and Wan et al. (2023) proposed hybrid WECs similar to that proposed by Zheng and Zhang (2018) and investigated their hydrodynamic performance using a three-dimensional (3D) analytical and computational fluid dynamic (CFD) model. Through a series of physical experiments and CFD calculations, Cheng et al. (2022b) also investigated the hydrodynamic performance of a similar hybrid system combining an oscillating buoy and a floating OWC. Moreover, Cheng et al. (2022a) proposed a novel space-saving hybrid WEC system with an oscillating buoy arranged inside the chamber of a floating OWC.

Most oscillating buoy WECs considered in the above integration structures are assumed to conduct heave motion along a vertical rail. In some studies, the oscillating WECs were also assumed to be hinged on the rear structure; therefore, the oscillating WECs and the rear structure are interconnected. In this case, the oscillating WECs conduct pitch motion relative to the hinge point due to the incoming waves, and this motion can be used to drive a power take-off (PTO) system to extract wave energy. For example, such hinge connection was applied in the hybrid WEC system (Zheng and Zhang, 2018; Cui et al., 2021; Wan et al., 2023) and the WEC-breakwater integration system (Zhao et al., 2021). However, studies comparing the hydrodynamic performance of the oscillating WECs, as well as investigating different connection approaches that determine which mode motion the oscillating WECs are constrained to, are scant.

The oscillating buoys considered in most research on the integration or hybrid system were assumed to be constrained to one certain degrees of freedom (DOF), whereas few studies focused on the effects of considering all degrees of freedom of oscillating WECs. Kara (2021, 2022) considered 6-DOF cylindrical buoys in front of a vertical wall. However, this research mainly focused on the effects of wall reflection and resonance within the WEC array and between the WEC array and the vertical wall. Zeng et al. (2022) analytically examined the hydrodynamic performance of an array of cylindrical oscillating WECs with five DOFs. They found that the calculation results for the WEC array with multiple DOFs are relatively different from those constrained in heave mode. However, no integration with other structures is considered in their study.

Whether for a WEC-breakwater integration system or a hybrid WEC system, the reflection from the rear structure and gap resonance remarkably influences the performance of the oscillating WECs (Zhang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). Therefore, in this study, the hydrodynamic performance of an oscillating WEC arranged in front of a vertical solid seawall is investigated using a 2D analytical model. The same integration structure has been investigated by Zhang et al. (2020), in which the oscillating WEC is constrained to heave mode. The novelty and focus of this study involve investigating the influence of multiple DOFs of the WEC and different connection approaches (different DOFs the WEC is constrained to) on the wave energy extraction performance of a WEC-vertical wall integration system. Specifically, cases with a 3-DOF WEC and a pitching WEC hinged to the seawall are considered here, and the case with a heaving WEC is presented for comparison. The study mainly focuses on the effects of the piston-mode resonance of the water column in the gap and the coupled WEC and water column resonant motion on the wave energy extraction performance of the oscillating WEC.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The analytical model is described in Section 2. The validation of the proposed model is given in Section 3. In Section 4, a comparison study is conducted to show the effects of multiple DOFs and different connection approaches of the oscillating WEC on the wave energy extraction performance. Then, a parametric study on the 3-DOF WEC and the WEC with a hinge connection is presented. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in Section 5.

2 Mathematical Model 2.1 Problem DescriptionThe sketch of an oscillating rectangular WECs in front of a vertical seawall with two different connection approaches is shown in Fig.1. For the first case, Fig.1(a) illustrates that the 3-DOF oscillating WEC is connected to a horizontal rigid arm fixed on the vertical sea wall. In this case, wave energy is extracted only through the heave mode motion of the WEC. For the second case shown in Fig.1(b), the oscillating WEC is hinged on the seawall with a rigid arm, and pitch motion relative to the hinge point is conducted. As shown in Fig.1(b), wave energy is assumed to be extracted either through the rotation around the hinge (PTO system 1) or the change in the vertical position of the WEC relative to the hinge point (PTO system 2). The differences in the hydrodynamic characteristics of the pitching WEC with the two PTO systems are discussed in the following section.

|

Fig. 1 Sketches of oscillating WECs arranged in front of a seawall with different connection approaches. (a), connection approach 1; (b), connection approach 2. |

The practical problem is reduced to a 2D problem under the linear potential flow theory. The simplified sketch of the structure is presented in Fig.2 to describe the wave diffraction and radiation problem more clearly. A 2D Cartesian coordinate (o-xz) is established with its origin located at the intersection of the mean water surface and the vertical axis of symmetry of the WEC. The z and x axes point vertically upward and toward the solid seawall, respectively. The linear harmonic waves with small amplitude A and wave frequency ω are assumed to propagate along the positive x-axis. The water depth is presumed to be constant and denoted as h. The width and draft of the WEC are indicated as B = 2a and d, respectively. The distance between the right vertical surface of the WEC and the seawall is denoted as D. For the connection approach in Fig.1(b), the coordinate of the hinge point on the seawall is (Xh, Zh), with a relation of Xh = a + D. The reference point of the pitch motion of the WEC is assumed to be the barycenter of the WEC, which is denoted as (x0, z0). For the convenience of calculation, the density of the WEC material is assumed to be half of the water density, indicating that the draft of the WEC is half its total height and the barycenter is located at the origin.

|

Fig. 2 Denotations of the structure dimension and fluid domains. |

In the frame of linear potential flow theory, the fluid is assumed to be inviscid, irrotational, and incompressible. Then, the fluid motion can be depicted using a velocity potential Φ(x, z, t) = Re[ϕ(x, z)e−iωt], where t is time; $\mathrm{i}=$ $\sqrt{-1}$ is the imaginary unit; ϕ is the spatial velocity potential satisfying the 2D Laplace equation.

In accordance with the linear potential flow theory, ϕ can be decomposed as follows:

| $ \phi {\text{ = }}{\phi _{\text{I}}} + {\phi _{\text{D}}} + \sum\limits_{j = 1}^3 {{{\dot \zeta }_j}} {\phi _{{\text{R}}, j}} ,$ | (1) |

where ϕI is the velocity potential of the incident waves;

ϕI can be written as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} \phi_{\mathrm{I}}(x, z)=-\frac{\mathrm{i} g A}{\omega} \frac{\cosh \left[k_{0}(z+h)\right]}{\cosh \left(k_{0} h\right)} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} ~k_{0} x}, \end{equation*} $ | (2) |

where g is the gravitational acceleration, and k0 is the wave number.

As shown in Fig.2, the entire fluid region is divided into three regions, denoted as Ωn (n = 1, 2, 3). Ω1 is the region defined by x ≤ −a, −h ≤ z ≤ 0; Ω2 is the region below the WEC (−a ≤ x ≤ −a, −h ≤ z ≤ −d); Ω3 is the region between the WEC and the seawall (a ≤ x ≤ a + D, −h ≤ z ≤ 0). For convenience, the spatial velocity potentials in Ωn can be denoted uniformly as $\phi_{\mathit{χ}}^{n}$, where χ = 'S' and 'R, j' (j = 1, 2, 3) represent the scattering and radiation potential, respectively. The scattering potential ϕS is the summation of ϕI and ϕD, and is considered hereafter.

With the boundary conditions on the free surface, sea bed, body surface, and far-field, the general expressions of velocity potentials in different fluid regions can be determined using the separation method of variables. Then, the eigenfunction expansion matching method can be adopted to calculate the unknown coefficients in the velocity potentials by considering the velocity and pressure continuity on the interface of different fluid regions. In fact, the same diffraction and radiation problem were already solved by Zheng et al. (2004); therefore, the solution procedure is only briefly introduced in this section.

The velocity potentials in different fluid domains are expressed as follows:

| $ \phi _\mathit{χ}^1 = \sum\nolimits_{n = 0}^{ + \infty } {R_n^\mathit{χ} } \frac{{\cos \left[ {{\mathit{λ} _n}\left({z + h} \right)} \right]}}{{\cos \left({{\mathit{λ} _n}h} \right)}}{{\text{e}}^{{\mathit{λ} _n}\left({x + b} \right)}} + \phi _\mathit{χ} ^{{\text{p}}1}\text{,} $ | (3) |

| $ \phi_{\mathit{χ}}^{2}=A_{0}^{\mathit{χ}}+B_{0}^{\mathit{χ}} x+ \\ ~~~\sum\limits_{n=1}^{+\infty}\left[A_{n}^{\mathit{χ}} \mathrm{e}^{\beta_{n}(x-b)}+B_{n}^{\mathit{χ}} \mathrm{e}^{-\beta_{n}(x+b)}\right] \cos \left[\beta_{n}(z+h)\right]+\phi_{\mathit{χ}}^{\mathrm{p} 2}, $ | (4) |

| $ \phi_{\mathit{χ}}^{4}=\sum\limits_{n=0}^{+\infty} C_{n}^{\mathit{χ}} \frac{\cos \left[\mathit{λ}_{n}(z+h)\right]}{\cos \mathit{λ}_{n} h} \cosh \left[\mathit{λ}_{n}(x-b-D)\right], $ | (5) |

where $R_{n}^{\mathit{χ}}, A_{n}^{\mathit{χ}}, B_{n}^{\mathit{χ}}$, and $C_{n}^{\mathit{χ}}$ in Eqs. (3) – (5) are unknown coefficients; λn and βn are the eigenvalues, which can be calculated as follows:

| $ \mathit{λ}_{n}=\left\{\begin{array}{c} -\mathrm{i} k_{0}, n=0 \\ k_{n}, n=1, 2, 3, \cdots \end{array}\right. \text{,} $ | (6) |

| $ \beta_{n}=\frac{n \mathsf{π} }{(h-d)}, n=0, 1, 2, 3, \cdots, $ | (7) |

where $k_{n}$ satisfies the dispersion relations of $\omega^{2}=g k_{0} \tanh \left(k_{0} h\right)$ and $\omega^{2}=-g k_{n} \tanh \left(k_{n} h\right)(n=1, 2, 3, \cdots); \phi_{\mathit{χ}}^{\mathrm{p1}}$ and $\phi_{\mathit{χ}}^{\mathrm{pp}}$ are expressed as follows:

| $ \phi _\mathit{χ} ^{{\text{p1}}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\phi _{\text{I}}}, {\text{ }}\mathit{χ} = {\text{S}}} \\ {0, {\text{ }}\mathit{χ} = R, j} \end{array}} \right. \text{,} $ | (8) |

| $ \phi _\mathit{χ} ^{{\text{p2}}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~{{\phi _{\text{I}}}, {\text{ }}\mathit{χ} = {\text{S}}} \\ \begin{array}{l} {\delta _{j, 2}}\frac{{{{(z + h)}^2} - {{(x - {x_0})}^2}}}{{2(h - d)}} + \hfill \\ ~~~~~{\delta _{j, 3}}\left[ { - \frac{{{{(z + h)}^2}x - {{{{(x - {x_0})}^3}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{{(x - {x_0})}^3}} 3}} \right. } 3}}}{{2(h - d)}}} \right], {\text{ }}\mathit{χ} = R, j \hfill \\ \end{array} \end{array}} \right. \text{,} $ | (9) |

where δj, n indicates the Kronecker delta.

2.3 Wave Excitation Forces and Hydrodynamic CoefficientsOnce the diffraction problem is solved, the wave excitation force and moment, which is denoted as $F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(i)}$, can be calculated by integrating the hydrodynamic pressure over the wet surface of the WEC as follows:

| $ F_{\text{e}}^{(i)} = {\text{i}}\omega \rho \int_{{S_{\text{w}}}} {{\phi _{\text{s}}}} {n_i}{\text{d}}s{\text{ (}}i = 1, 2, 3{\text{)}}\text{,} $ | (10) |

where ρ is water density; Sw represents the wet surface of WEC; ni is the generalized normal vector in the ith mode (n1 = nx, n2 = nz, n3 = (z − z0)nx − (x − x0)nz). nx and nz point outward of the fluid domain. Similarly, the radiation force and moment acting on the WEC in the ith mode, which is denoted as

| $ \begin{align*} F_{\mathrm{R}}^{(i)} & =\mathrm{i} \omega \rho \int_{S_{\mathrm{w}}} \sum\limits_{j=1}^{3} \dot{\zeta}_{j} \phi_{\mathrm{R}, j} n_{i} \mathrm{d} s \\ & =\sum\limits_{j=1}^{3}\left(\mathrm{i} \omega \rho \int_{S_{\mathrm{w}}} \operatorname{Re}\left(\phi_{\mathrm{R}, j}\right) n_{i} \mathrm{d} s-\omega \rho \int_{S_{\mathrm{w}}} \operatorname{Im}\left(\phi_{\mathrm{R}, j}\right) n_{i} \mathrm{d} s\right) \\ & =\sum\limits_{j=1}^{3} \dot{\zeta}_{j}\left(\mathrm{i} \omega \mu_{j}^{i}-c_{j}^{i}\right) \text{,} \end{align*} $ | (11) |

where $\mu_{j}^{i}$ and $c_{j}^{i}$ are the added mass and radiation damping, respectively, in the ith mode induced by the unit amplitude velocity motion in the jth mode. The expressions of $F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(i)}$ and $F_{\mathrm{R}}^{(i)}$ are presented in Appendix A.

Except for the aforementioned direct method (Eqs. (10) and (11)), the wave excitation and radiation force can also be determined by the hydrodynamic identities derived from Green's theorem (Falnes, 2002). The wave excitation force can be calculated using the Haskin relation and then expressed using the far-field coefficients of radiated waves as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(i)}=\frac{-\mathrm{i} \rho g A k_{0} h R_{1}^{R, i}}{\left(\cosh \left(k_{0} h\right)\right)^{2}}\left[1+\frac{\sinh \left(2 k_{0} h\right)}{2 k_{0} h}\right] \mathrm{e}^{-\mathrm{i} k_{0} a} \end{equation*} . $ | (12) |

Similarly, the radiation damping can be expressed using the far-field coefficients of radiated waves, as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} c_{j}^{i}=\frac{\omega \rho k_{0} h}{4\left(\cosh \left(k_{0} h\right)\right)^{2}}\left[1+\frac{\sinh \left(2 k_{0} h\right)}{2 k_{0} h}\right]\left[\left(R_{1}^{\mathrm{R}, i}\right)^{*} R_{1}^{\mathrm{R}, j}+\left(R_{1}^{\mathrm{R}, j}\right)^{*} R_{1}^{\mathrm{R}, i}\right], \end{equation*} $ | (13) |

where the superscript '*' represents considering the complex conjugate.

2.4 Motion Equations and Other Hydrodynamic QuantitiesAfter solving the diffraction and radiation problem, the motion response of the oscillating WEC can be determined using the motion equation in the frequency domain. Then, the wave energy absorption and optimum PTO damping corresponding to the two cases shown in Fig.1 are presented separately.

2.4.1 Case 1For the connection approach shown in Fig.1(a), the motion equation can be expressed as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} \boldsymbol{F}_{\mathrm{e}}=\left(-\mathrm{i} \omega(\boldsymbol{M}+\boldsymbol{\mu})+\left(\boldsymbol{C}+\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathrm{PTO}}\right)+\mathrm{i} \boldsymbol{K}_{\mathrm{HS}} / \omega\right) \boldsymbol{\dot{\zeta}}, \end{equation*} $ | (14) |

where Fe is the wave excitation vector; M indicates the mass and rotary inertia matrix; μ and C are the added mass and radiation damping matrix, respectively; CPTO represents the PTO damping matrix; KHS denotes the hydrostatic stiffness matrix; $\boldsymbol{\dot{\zeta}}=\left[\dot{\zeta}_{1}, \dot{\zeta}_{2}, \dot{\zeta}_{3}\right]^{\mathrm{T}}$ is the complex velocity amplitude vector, and the superscript 'T' denotes the transpose. M, CPTO, and KHS are presented as follows:

| $ \left\{\begin{array}{l} \boldsymbol{M}=\left[\begin{array}{lll} M & & \\ & M & \\ & & I \end{array}\right], \boldsymbol{C}_{\mathrm{PTO}}=\left[\begin{array}{lll} 0 & & \\ & c_1 & \\ & & 0 \end{array}\right] \\ \boldsymbol{K}_{\mathrm{HS}}=\left[\begin{array}{lll} 0 & & \\ & \rho g B & \\ & & \\ & & \rho g\left(\frac{2 a^3}{3}-a d^2\right) \end{array}\right] \end{array}\right.,$ | (15) |

where M = ρBd is the mass of the WEC; $I=\frac{M\left(B^{2}+d^{2}\right)}{12}$ indicates the rotary inertia of the oscillating WEC relative to the barycenter; c1 denotes the damping of the linear PTO system.

Once $\boldsymbol{\dot{\zeta}}$ is determined through Eq. (14), the absorbed wave energy P can be calculated by the following equation:

| $ \begin{equation*} P=\frac{1}{2} c_{1} \dot{\zeta}_{2}^{*} \dot{\zeta}_{2}. \end{equation*} $ | (16) |

To determine the optimal PTO damping, we define a new matrix as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} \boldsymbol{S}=\left(-\mathrm{i} \omega(\boldsymbol{M}+\boldsymbol{\mu})+\boldsymbol{C}+\mathrm{i} \boldsymbol{K}_{H S} / \omega\right) . \end{equation*} $ | (17) |

Using Eq. (14) and making some rearrangements, $\dot{\zeta}_{2}$ can be calculated as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} \dot{\zeta}_{2}=\frac{a_{1}}{c_{1}+a_{2}}, \end{equation*}$ | (18) |

where

| $ a_{1}=F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(2)}+\frac{F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(1)}(\boldsymbol{S}(3, 3) \boldsymbol{S}(2, 1)+\boldsymbol{S}(3, 1) \boldsymbol{S}(2, 3))-F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(3)}(\boldsymbol{S}(1, 3) \boldsymbol{S}(2, 1)+\boldsymbol{S}(1, 1) \boldsymbol{S}(2, 3))}{\boldsymbol{S}(1, 3) \boldsymbol{S}(3, 1)-\boldsymbol{S}(1, 1) \boldsymbol{S}(3, 3)}, $ | (19) |

| $ a_{2}=\boldsymbol{S}(2, 2)-\frac{\boldsymbol{S}(2, 1)(\boldsymbol{S}(1, 3) \boldsymbol{S}(3, 2)-\boldsymbol{S}(1, 2) \boldsymbol{S}(3, 3))+\boldsymbol{S}(2, 3)(\boldsymbol{S}(3, 1) \boldsymbol{S}(1, 2)-\boldsymbol{S}(3, 2) \boldsymbol{S}(1, 1))}{\boldsymbol{S}(1, 3) \boldsymbol{S}(3, 1)-\boldsymbol{S}(1, 1) \boldsymbol{S}(3, 3)} . . $ | (20) |

Substituting Eq. (18) into Eq. (16), the maximum absorbed wave energy can be achieved when the differential equation dP/dc1 is equal to zero (Falnes, 2002). The optimal PTO damping $c_{1}^{\mathrm{opt}}$ can be determined as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} c_{1}^{\mathrm{opt}}=\left|a_{2}\right| . \end{equation*} $ | (21) |

For the connection approach shown in Fig.1(b), the motion equation can be written in the following form (Sun et al., 2011):

| $ \left[\begin{array}{cc} -\mathrm{i} \omega(\boldsymbol{M}+\boldsymbol{\mu})+\left(\boldsymbol{C}+\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathrm{PTO}}\right)+\mathrm{i} \boldsymbol{K}_{\mathrm{HS}} / \omega & \boldsymbol{A}_{J}^{\mathrm{T}} \\ \boldsymbol{A}_{J} & \mathbf{0} \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c} \dot{\boldsymbol{\zeta}} \\ \boldsymbol{F}_{\mathrm{h}} \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol{F}_{\mathrm{e}} \\ \mathbf{0} \end{array}\right], $ | (22) |

where AJ is the constraint matrix due to the hinge restriction; Fh = [

| $ \boldsymbol{A}_{J}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & 0 & Z_{\mathrm{h}} \\ 0 & 1 & -X_{\mathrm{h}} \end{array}\right]. $ | (23) |

As mentioned at the beginning of Section 2.1, two common PTO systems can be separately applied for wave energy absorption (Fig.1(b)). The PTO damping matrix corresponding to PTO systems 1 and 2 can be written as follows:

| $ {\boldsymbol{C}_{{\text{PTO}}}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 0&{}&{} \\ {}&0&{} \\ {}&{}&{{c_{2, 1}}} \end{array}} \right] \text{,} $ | (24a) |

| $ {\boldsymbol{C}_{{\text{PTO}}}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 0&{}&{} \\ {}&{{c_{2, 2}}}&{} \\ {}&{}&0 \end{array}} \right] \text{,} $ | (24b) |

In fact, the maximum absorbed wave energy by the two PTO systems is the same, and the derivation is illustrated in Appendix B. Therefore, the PTO system 1 is investigated particularly as a representative. The derivation of the optimal PTO damping for PTO system 1 is presented as follows:

S can be rewritten as follows:

| $ \boldsymbol{S} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\boldsymbol{S}_{11}}}&{{\boldsymbol{S}_{12}}} \\ {{\boldsymbol{S}_{21}}}&{{\boldsymbol{S}_{22}}} \end{array}} \right], $ | (25) |

where the sizes of S11, S12, S21, and S22 are 2 × 2, 2 × 1, 1 × 2, and 1 × 1, respectively. In accordance with Eq. (22), the following relations can be obtained:

| $ \boldsymbol{F}_{\mathrm{h}}+\left(\boldsymbol{S}_{11} \boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}+\boldsymbol{S}_{12}\right) \dot{\zeta}_{3}=\left[\begin{array}{l} F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(1)} \\ F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(2)} \end{array}\right], $ | (26) |

| $ \left(\boldsymbol{S}_{21} \boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}+\boldsymbol{S}_{22}+c_{2, 1}\right) \dot{\zeta}_{3}-\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{F}_{\mathrm{h}}=F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(3)} \text{,} $ | (27) |

where BT = [−Zh, Xh]T. Combining Eq. (26) and (27) and eliminating Fh provides the following:

| $ \begin{align*} & \left(\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{S}_{11} \boldsymbol{B}_{T}+\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{S}_{12}+\boldsymbol{S}_{21} \boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}+\boldsymbol{S}_{22}+c_{2, 1}\right) \dot{\zeta}_{3}= \\ & \quad F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(3)}+\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}}\left[\begin{array}{l} F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(1)} \\ F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(2)} \end{array}\right] . \end{align*} $ | (28) |

Therefore, $\dot{\zeta}_{3}$ can be easily expressed in the following form:

| $ {\dot \zeta _3} = \frac{{{a_3}}}{{{c_{2, 1}} + {a_4}}}, $ | (29) |

where

| $ a_{3}=F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(3)}+\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}}\left[\begin{array}{c} F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(1)} \\ F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(2)} \end{array}\right], $ | (30) |

| $ a_{4}=\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{S}_{11} \boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}+\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{S}_{12}+\boldsymbol{S}_{21} \boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}+\boldsymbol{S}_{22} . $ | (31) |

Similar to Section 2.4.1, the absorbed wave energy P can be calculated as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} P=\frac{1}{2} c_{2, 1} \dot{\zeta}_{3}^{*} \dot{\zeta}_{3} \end{equation*}. $ | (32) |

The optimal PTO damping $c_{2, 1}^{\text {opt }}$ can be calculated as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} c_{2, 1}^{\mathrm{opt}}=\left|a_{4}\right|=\left|\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{S}_{11} \boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}+\boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{S}_{12}+\boldsymbol{S}_{21} \boldsymbol{B}_{\mathrm{T}}+\boldsymbol{S}_{22}\right| \end{equation*} . $ | (33) |

The capture width ratio (CWR) or the wave energy extraction efficiency is calculated as follows:

| $ \eta = \frac{P}{{{P_{{\text{in}}}}}}\text{,} $ | (34) |

where Pin is the incident wave energy per unit wave front length,

| $ {P_{{\text{in}}}} = \frac{1}{2}\frac{{\rho g{A^2}\omega }}{{2{k_0}}}\left[ {1 + \frac{{2{k_0}h}}{{\sinh \left({2{k_0}h} \right)}}} \right]. $ | (35) |

The response amplitude operator (RAO) is defined as follows:

| $ {\text{RA}}{{\text{O}}_j} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{{\zeta _j}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\zeta _j}} A}} \right. } A}, j = 1, 2} \\ {{{{\zeta _j}a} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\zeta _j}a} A}} \right. } A}, j = 3} \end{array}} \right., $ | (36) |

where ζj is the displacement amplitude of the motion in jth mode.

The reflection coefficient Kr is the ratio of the reflected wave amplitude far from the oscillating WEC to the incident wave amplitude, which can be expressed as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} K_{\mathrm{r}}=\left|\frac{R_{1}^{\mathrm{S}}+\sum\limits_{j=1}^{3} \dot{\zeta}_{j} R_{1}^{\mathrm{R}, j}}{\frac{-\mathrm{i} g A}{\omega}}\right| . \end{equation*} $ | (37) |

The free surface elevation can be calculated by substituting the coordinates of the surface point into the following equation:

| $ \begin{equation*} A_{f}(x)=\left.\frac{\mathrm{i} \omega}{g} \phi(x, z)\right|_{z=0} . \end{equation*} $ | (38) |

As described in Subsection 2.3, the wave excitation forces and radiation damping coefficients can be calculated by the direct and indirect methods. The agreement between the results calculated by different methods can be used to validate the theoretical model (Zheng and Zhang, 2018; Zheng et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2022).

For convenience, the wave excitation forces

| $ \bar{F}_{\mathrm{e}}^{(i)}=\left\{\begin{array}{l} F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(i)} / \rho g a h, i=1, 2 \\ F_{\mathrm{e}}^{(i)} / \rho g a^{2} h, i=3 \end{array}, \right. $ | (39) |

| $ \bar{c}_{j}^{i}=\left\{\begin{array}{l} c_{j}^{i} / \rho \omega g a h, i=1, 2 \text { and } j=1, 2 \\ c_{j}^{i} / \rho \omega g a^{2} h, i=3 \text { and } j=1, 2 ; i=1, 2 \text { and } j=3 . \\ c_{j}^{i} / \rho \omega g a^{3} h, i=3 \text { and } j=3 \end{array}\right. $ | (40) |

The case with geometrical parameters of a/h = 0.2, d/h = 0.15, D/h = 0.2 is considered. The results of $\bar{F}_{\mathrm{e}}^{(i)}$ and $\bar{c}_{j}^{i}$ calculated by different methods are shown in Figs.3 and 4, respectively. The figures illustrate that the wave excitation forces and radiation damping coefficients calculated using the direct and indirect methods show good agreement.

|

Fig. 3 Normalized wave excitation forces calculated by different methods. (a), surge and heave wave excitation forces; (b), pitch wave excitation force (a/h = 0.2, d/h = 0.2, D/h = 0.2). |

|

Fig. 4 Normalized radiation damping coefficients calculated by different methods. (a), radiation damping in surge mode induced by surge and heave motion; (b), radiation damping in surge and heave mode induced by pitch motion; (c), radiation damping in heave mode induced by heave motion; (d), radiation damping in pitch mode induced by pitch motion (a/h = 0.2, d/h = 0.2, D/h = 0.2). |

The wave energy conservation law should be satisfied by the proposed theoretical model. The relation between the absorbed wave energy and reflection coefficient is written as η + Kr2 = 1. The results of reflection coefficient Kr, wave energy CWR η, and η + Kr2 for the two connection approaches shown in Fig.1 are presented in Fig.5. The geometrical parameters used in this subsection are the same as those in Subsection 3.1. The position of the hinge point for the second connection approach is defined as Xh /h = (a + D)/h = 0.4 and Zh /h = 0.4. The optimal PTO damping proposed in Subsection 2.4 is adopted in the calculation throughout the study. The finding indicates that the energy conservation law is satisfied.

|

Fig. 5 Frequency response of reflection coefficient Kr, wave energy CWR η, and η + Kr2. (a), connection approach in Fig. 1(a); (b), connection approach in Fig. 1(b). a/h = 0.2, d/h = 0.15, D/h = 0.2, Xh /h = 0.4, Zh /h = 0.4. |

The proposed theoretical model is successfully validated. Moreover, the calculation results are sufficiently convergent after truncating the infinite series of the velocity potentials (Eqs. (3) – (4)) at 30 terms applied hereafter.

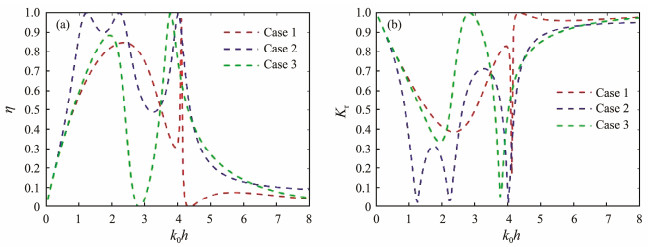

4 Results and Discussion 4.1 Comparison StudyIn this subsection, the wave energy CWR and reflection coefficient for the oscillating WECs with two different connection approaches shown in Fig.1 are compared. Moreover, the case with a 1-DOF WEC (heaving WEC) arranged in front of the seawall is presented for comparison. Note that the theoretical model for a rectangular heaving WEC arranged in front of a solid vertical wall has been proposed by Zhang et al. (2020) and, therefore, not presented here. For convenience, the oscillating WEC with three DOFs, with a hinge connection (constrained to pitch mode), and constrained to heave mode is defined in cases 1 – 3. The results of CWR η and reflection coefficient Kr for the three cases mentioned above are illustrated in Fig.6. The geometrical parameters for the three cases are the same and listed as a/h = 0.2, d/h = 0.15, and D/h = 0.2. The x and z coordinates of the hinge point for case 2 are Xh /h = 0.4 and Zh /h = 0.4, respectively.

|

Fig. 6 Frequency response of (a) wave energy CWR η and (b) reflection coefficient Kr for cases 1 – 3 (a/h = 0.2, d/h = 0.2, D/h = 0.2, Xh /h = 0.4, Zh /h = 0.4). |

As shown in Fig.6, the wave energy extraction performance for the three cases is different. Case 1 (a 3-DOF WEC) has a broader high-efficiency bandwidth for η > 0.5 in the low-frequency region of 0 < k0h < 3.5 than case 3 (a heaving WEC). For example, the frequency region for η > 0.5 for case 1 is 0.8 < k0h < 3.5, whereas that for case 3 is 0.8 < k0h < 2.4. By contrast, the wave energy extraction efficiency for case 1 at a higher frequency (3.5 < k0h < 8) is considerably lower than that for case 3, except at k0h = 4.1 where a spike is shown on the frequency response of η for case 1 due to the heave motion resonance. This finding is consistent with the frequency response of the heave RAO for cases 1 and 3, as shown in Fig.7(b). The figure illustrates that the heave RAO for case 1 decreases drastically after the spike at k0h = 4.1. Another evident difference between cases 1 and 3 is that the frequency corresponds to the zero value of η (k0h = 4.35 for case 1 and k0h = 2.8 for case 3). For the heaving WEC in case 3, the wave excitation force in heave mode and the heave radiation damping are zero at k0h = 2.8 (Figs.3(a) and 4(c)). Therefore, as shown in Fig.7, the heave RAO for case 3 is also zero at this frequency. However, the frequency corresponding to the zero heave RAO for the 3-DOF WEC (case 1) shifts toward a higher value due to the effects of multiple DOFs.

|

Fig. 7 Frequency response of RAO of the oscillating WEC and the dimensionless free surface elevation Af/A in the gap between the WEC and the sea wall for cases 1 – 3. (a), surge RAO; (b), heave RAO; (c), pitch RAO; (d), free surface elevation. |

Case 2 (a pitching WEC with a hinge connection) has the highest energy extraction efficiency among the three cases in the low-frequency region of 0.4 < k0h < 2.5. The two peaks of the CWR occur at k0h = 1.25 and 2.25, the values of which almost reach 1. As k0h increases from 2.25, the CWR decreases initially and then increases to another peak close to 1 at k0h = 4. The trimodal trend of the CWR curve is similar to that found in Zhao et al. (2021), where a floating WEC is hinged to a floating breakwater. At the frequency region of 3.5 < k0h < 8, the wave energy extraction efficiency of case 2 resembles that of case 3 but is much better than that of case 1. Moreover, case 2 has the broadest frequency region for η > 0.5, which is 0.65 < k0h < 4.35. The oscillating WEC in case 2 conducts a 1-DOF pitch motion relative to the hinge point. Thus, the RAOj (j = 1, 2, 3) for case 2 relative to the barycenter of the WEC shown in Figs.7(a) – 7(c) is proportional. The figures indicate that the peaks of η at k0h = 1.25 and 4 correspond to the two peaks of RAO for case 2. The peaks of η and RAO j (j = 1, 2, 3) for case 2 at k0h = 1.25 and 4 correspond to the pitch and heave motion resonance of the WEC, respectively, given the absence of mooring stiffness in the sway mode. The spikes shown on the frequency response of the RAO j (j = 1, 2, 3) for case 1 also verified this result (Fig.7). However, the peak of η at k0h = 2.25 corresponds to a relatively small RAO. This finding is further explained by the frequency response of the optimal PTO damping shown in Fig.8. The nondimensional optimal damping in Fig.8 has the same form as in Eq. (39), and $\bar{c}_3^{\mathrm{opt}}$ denotes the optimal PTO damping for case 3. The optimal PTO damping for case 2 reaches a peak at k0h = 2.25, which is the proximate cause of the peak of η. Moreover, as shown in Fig.7(d), the dimensionless free surface elevation at the middle point of the gap between the WEC and the sea wall shows a peak at k0h = 2.25. The relation between all these phenomena occurring at k0h = 2.25 requires in-depth research.

|

Fig. 8 Frequency response of the optimal PTO damping for cases 1 – 3. |

The oscillating WECs for cases 2 and 3 have one DOF, whereas the WEC for case 1 has three DOFs. When the WEC is free to oscillate in all three DOFs, only the coupled WEC and water column resonant motion is evident. The piston-mode resonance can also be retained when the WEC is fixed at one DOF (McIver, 2005; Kristiansen and Faltinsen, 2010). As shown in Fig.7(d), the frequency response for the free surface elevation in the gap for cases 2 and 3 shows two evident peaks but only one evident spike for case 1. The low-frequency peak of the free surface elevation in the gap for cases 2 and 3 is due to the piston-mode resonance of the water column in the gap, whereas the high-frequency peak is caused by the coupled WEC and water column resonant motion.

As shown in Fig.6(b), the variation of the reflection coefficient for the three cases against the wave frequency is opposite that of the CWR. In other words, the case with a higher CWR has a weaker wave reflection. This finding is consistent with the wave energy conservation law described in Subsection 3.2. Therefore, the results of the reflection coefficient are not presented and discussed in the following section.

The energy extraction efficiency for case 2 (with a hinged WEC), under the specified conditions, has the best overall wave energy extraction performance, whether in terms of the frequency bandwidth of η > 0.5 or the peak value of the CWR. However, case 1 (with a 3-DOF WEC) has a higher wave energy extraction efficiency at 2.5 < k0h < 3.45.

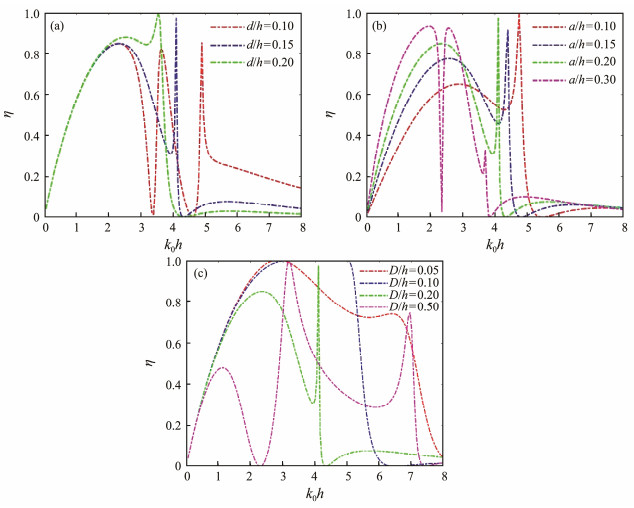

4.2 Parametric Study on Case 1 (3-DOF WEC)In this section, the influence of the draft d/h and width a/h of the oscillating WEC and the gap distance D/h between the WEC and the seawall on the wave energy extraction performance of the 3-DOF WEC shown in Fig.1(a) are investigated. The frequency response of CWR with different values of d/h, a/h, and D/h is shown in Fig.9. When one of the geometrical parameters changes, the other parameters are held constant, where a/h = 0.2, d/h = 0.15, and D/h = 0.2.

|

Fig. 9 Frequency response of the wave energy CWR η for case 1 with different (a) draft d/h, (b) width a/h, and (c) distance D/h between the WEC and the seawall. |

As shown in Fig.9(a), the draft d/h of the oscillating WEC slightly affects the wave energy extraction efficiency at a low frequency (0 < k0h < 2). As the draft d/h increases from 0.1 to 0.2, the coupled WEC and water column resonant motion frequency shifts from k0h = 4.90 to 3.55, and the CWR at a high frequency (5 < k0h < 8) decreases from above 0.15 to below 0.05.

Different from the cases with d/h = 0.15 and 0.2, two troughs at k0h = 3.35 and 4.65 are observed on the frequency response of the CWR for the case with d/h = 0.1. Specifically, the frequency response of RAOj (j = 1, 2, 3), the free surface elevation in the gap, and the phase for the case with d/h = 0.1 are shown in Fig.10. The figure presents that the two troughs on the CWR curve correspond to the troughs on the RAO2 curve. Moreover, corresponding to the peak of the CWR at k0h = 3.6, the frequency response of RAO2 and RAO3 exhibit a peak at this frequency, whereas the sway amplitude of the WEC (RAO1) reaches a trough. Interestingly, a sharp decrease at k0h = 3.6 is found in the frequency response of the surface elevation in the gap. The surface elevation in the gap is mainly dependent on the sway motion of the WEC under the considered condition because the trend of Af /A and θf /π against k0h is mainly consistent with that of RAO1 and θ1/π, respectively. This finding indicates that the free surface elevation in the gap moves upward as the WEC moves toward the sea wall, and the oscillation amplitude of the free surface enlarges with a larger sway motion amplitude of the WEC. The peak of Af /A, the CWR at k0h = 4.9, and the downward spike of θf /π are due to the coupled WEC and water column resonant motion.

|

Fig. 10 Frequency response of RAO, dimensionless free surface elevation |Af|/A, and phase for the case with d/h = 0.1. (a), RAOj; (b), θj /π; (c), |Af|/A; (d), θf /π. |

As shown in Fig.9(b), as the width a/h of the WEC increases from 0.1 to 0.3, the coupled WEC and water column resonant motion frequency decreases from 4.75 to 3.7; the corresponding peak of the CWR remains steady above 0.95 initially and suddenly drops to below 0.4 for the case with a/h = 0.3. The CWR at a low frequency (0 < k0h < 3) mainly increases as the width a/h increases, except that a downward spike occurs on the CWR curve with a/h = 0.3 at around k0h = 2.35 (similar to the case of d/h = 0.1 in Fig.9(a)). As a result, the high-efficiency region for η > 0.5 shifts toward the low-frequency region. The frequency regions where η > 0.5 for the cases with a/h = 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, and 0.3 are [1.6, 4.85], [1.1, 4.4], [0.8, 3.5], and [0.55, 2.25]∪[2.4, 3.25], respectively.

Fig.9(c) shows no evident peak and trough on the frequency response of the CWR at the specified frequency region when the oscillating WEC is arranged close to the solid seawall, for example, the cases with D/h = 0.05 and 0.1. As the distance D/h increases, the frequency response of the CWR shows a multimodal trend; the wave energy extraction efficiency at a low frequency (0 < k0h < 3) decreases significantly; the frequency bandwidth for η > 0.5 at a high frequency (3 < k0h < 8) mainly decreases. The fluctuations of the CWR curve at the specified frequency region are expected to become more frequent as the distance D/h increases, consistent with the case with a heaving WEC in front of a solid vertical wall (Zhang et al., 2020). The case where the WEC is very far from the seawall (D/h > > 0.5) is not considered here because the cost of installation, power transmission, and maintenance can increase significantly as the distance between the oscillating WEC and the seawall increases.

4.3 Parametric Study on Case 2 (Pitching WEC)In this section, a parametric study is conducted to investigate the influence of the dimension of the oscillating WEC (draft d/h and width a/h), the distance D/h between the WEC and the seawall, and the position of the hinge point on the wave energy extraction performance of a pitching WEC oscillating relative to the hinge point. The frequency response of wave energy CWR with different values of d/h, a/h, D/h, and Zh/h are shown in Fig.11. When one geometrical parameter changes, the other parameters are held constant at a/h = 0.2, d/h = 0.15, D/h = 0.2, and Zh/h = 0.4. The difference between the x coordinate of the hinge point and the connection point of the arm on the WEC is fixed when considering the effects of the width a/h of the WEC. In other words, the value of Xh/h is fixed (Xh/h = 0.4) and not equal to (a + D)/h when the effects of a/h are considered, which indicates that the rigid connection point of the arm on the WEC may not be located at the vertical axis of symmetry.

|

Fig. 11 Frequency response of the wave energy CWR η for case 2 with different (a) draft d/h, (b) width a/h, (c) distance D/h between the WEC and the seawall, and (d) position of the hinge point Zh/h. |

As shown in Fig.11(a), all peaks of the CWR at the considered frequency region shift toward the low-frequency region as the draft d/h of the WEC increases. The first trough of the CWR decreases slightly and mainly remained above 0.75 as the draft d/h increases from 0.1 to 0.2; the second trough, however, increases drastically from 0.21 to 0.59. The results reveal that the frequency region for η > 0.5, which is mainly located at a low-frequency region of 0 < k0h < 4.5, is broader with a larger draft d/h. Moreover, the wave energy extraction efficiency at a high frequency (5 < k0h < 8) is improved for the case with a larger draft d/h.

As shown in Fig.11(b), as the width a/h increases, the second and third peaks of the CWR, which correspond to the piston-mode gap resonance and the coupled WEC and water column motion resonance, respectively, shift toward the low-frequency region and become sharper. As a result, the frequency bandwidth for η > 0.5 shrinks rapidly as the width a/h increases. Specifically, the wave energy extraction efficiency at a high frequency (k0h > 4) deteriorates significantly.

As shown in Fig.11(c), when the distance D/h between the WEC and the sea wall is relatively small (D/h = 0.05), the troughs on the frequency response of the CWR are lower than 0.4, and the peaks are located at relatively high frequencies. As the distance D/h increases from 0.05 to 0.2, the peaks of the CWR shift rapidly toward the low-frequency region, and the troughs of the CWR increase significantly from below 0.4 to above 0.6. When the distance D/h is relatively large (D/h = 0.5), the frequency response of the CWR shows a very different pattern from the other cases with relatively smaller distances: the peaks of the CWR are less than 0.7, and the energy extraction efficiency is almost zero for the frequency region of 2.8 < k0h < 3.2. In this case (D/h = 0.5), the three peaks of the CWR shown in the cases with D/h = 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 combine to one small peak at a low frequency; the peaks of the CWR corresponding to the sloshing water resonance and the coupled WEC and water sloshing resonant motion are at 6.5 and 6.8, respectively. To illustrate this finding, the dimensionless free surface elevation |Af|/A and its phase θf /h along the x-axis for the case with D/h = 0.5 at k0h = 6.5 and 6.8 are shown in Fig.12. The orange area and the black thick line denote the position of the oscillating WEC and the seawall, respectively. Evidently, the standing waves with large amplitudes |Af|/A (larger than 5) occur in the gap between the WEC and seawall at k0h = 6.5 and 6.8, respectively. The free surface elevation in the gap can be overpredicted considerably because no viscosity and nonlinear effects are considered in the proposed model (Kristiansen and Faltinsen, 2010; Zhang et al., 2021), whereas the resonance frequencies are credible.

|

Fig. 12 Free surface elevation |Af|/A and phase θf /π along the x-axis for the case with D/h = 0.5 at k0h = 6.5 and 6.8. |

As shown in Fig.11(d), the position of the hinge point on the seawall slightly affects the frequency of the peaks of the CWR corresponding to the piston-mode gap resonance and the coupled WEC and water column motion resonance. This result is anticipated because the change in the hinge point position does not affect the hydrodynamic coefficients calculated from the proposed theoretical model. However, the hinge point position greatly influences the rotary characteristics of the oscillating WEC. As the z coordinate Zh/h of the hinge point increases from 0.2 to 0.8, the wave energy extraction efficiency at the frequency region of 3 < k0h < 8 increases drastically, whereas the first trough at the frequency region of 1 < k0h < 3 decreases but still remains above 0.5. A similar variation trend of the CWR against the hinge point position can also be found in Zhao et al. (2021) when the hydrodynamic performance of a floating WEC hinged to a floating breakwater was investigated.

5 ConclusionsIn this study, the hydrodynamic performance of an oscillating WEC deployed in front of a vertical solid sea wall is investigated using a 2D analytical model. The cases with a 3-DOF WEC and a WEC hinged to the seawall are considered to investigate the influence of different DOFs of the WEC on the wave energy extraction performance. The analytical model is validated against the hydrodynamic coefficients calculated using the direct and indirect methods and the wave energy conservation law.

A comparison study between the cases with a 3-DOF WEC, a WEC with a hinge connection (constrained to pitch mode), and a WEC constrained to heave mode is presented initially. The results reveal that, under the specified conditions, the piston-mode water resonance in the gap and the coupled WEC and water column resonant motion exhibit peaks in the frequency response of the CWR. The case with a pitching WEC has the largest wave energy extraction efficiency among all three cases at a low frequency (0.4 < k0h < 2.5). At a middle frequency (2.5 < k0h < 3.5), the case with a 3-DOF WEC mainly has the largest wave energy extraction efficiency. At a high frequency (3.5 < k0h < 8), the cases with a pitching WEC and a heaving WEC have similar performance, indicating improved performance compared with that of a 3-DOF WEC. In general, the case with a pitching WEC has the broadest frequency bandwidth for η > 0.5.

Through a parametric study of the cases with a 3-DOF WEC and a pitching WEC (hinged to the seawall), the following conclusions can be drawn:

1) The peaks on the frequency response of the CWR for both cases shift toward the low-frequency region as the draft and width of the WEC increase, generally accompanied by the reduction of the wave energy extraction efficiency at a high frequency. The wave energy extraction efficiency at a low frequency (around k0h = 2) increases as the width of the WEC increases.

2) The CWR for both cases is very sensitive to the distance between the WEC and the seawall. For the case with a 3-DOF WEC, the frequency response of the CWR shows a multimodal trend as the distance D/h increases. The CWR decreases significantly as D/h increases at a low frequency (0 < k0h < 3), whereas it mainly decreases initially and then increases at a high frequency (3 < k0h < 8). For the case with a pitching WEC, all peaks of the CWR shift to the low-frequency region and the troughs increase significantly as the distance D/h increases from 0.05 to 0.2; the CWR sharply decreases as D/h increases from 0.2 to 0.5.

3) The position of the hinge point on the seawall significantly influences the wave energy extraction performance of the WEC. The CWR at a high frequency (2.5 < k0h < 8) decreases significantly as the hinge position moves upward, whereas it increases at a low frequency (1 < k0h < 2.5).

The present work operates within the framework of linear potential flow theory, and it does not consider the fluid viscosity and nonlinear effects. Therefore, the wave energy CWR and the free surface elevation in the gap may be significantly overestimated, especially at the resonance frequency. The viscous and nonlinearity effects can be further investigated using physical experiments and CFD methods.

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported by the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province, China (No. 2021ZLGX04), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52171284).

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material is available in the online version of this article at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11802-025-5890-3.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Yuhan Wang. The draft of the manuscript was written by Yuhan Wang, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Cheng, Y., Du, W., Dai, S., Ji, C., Collu, M., Cocard, M., et al., 2022a. Hydrodynamic characteristics of a hybrid oscillating water column-oscillating buoy wave energy converter integrated into a π-type floating breakwater. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 161: 112299. (  0) 0) |

Cheng, Y., Fu, L., Dai, S., Collu, M., Cui, L., Yuan, Z., et al., 2022b. Experimental and numerical analysis of a hybrid WEC-breakwater system combining an oscillating water column and an oscillating buoy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 169: 112909. (  0) 0) |

Cui, L., Zheng, S., Zhang, Y., Miles, J., and Iglesias, G., 2021. Wave power extraction from a hybrid oscillating water column-oscillating buoy wave energy converter. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 135: 110234. (  0) 0) |

Falnes, J., 2002. Ocean Waves and Oscillating Systems: Linear Interaction Including Wave-Energy Extraction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 200-204. (  0) 0) |

Gang, A., Guo, B., Hu, Z., and Hu, R., 2022. Performance analysis of a coast – OWC wave energy converter integrated system. Applied Energy, 311: 118605. (  0) 0) |

Kara, F., 2021. Hydrodynamic performances of wave energy converter arrays in front of a vertical wall. Ocean Engineering, 235: 109459. (  0) 0) |

Kara, F., 2022. Effects of a vertical wall on wave power absorption with wave energy converters arrays. Renewable Energy, 196: 812-823. (  0) 0) |

Kristiansen, T., and Faltinsen, O. M., 2010. A two-dimensional numerical and experimental study of resonant coupled ship and piston-mode motion. Applied Ocean Research, 32: 158-176. (  0) 0) |

Mayon, R., Ning, D., Sun, Y., Ding, Z., and Wang, R., 2023. Experimental investigation on a novel and hyper-efficient oscillating water column wave energy converter coupled with a parabolic breakwater. Coastal Engineering, 185: 104360. (  0) 0) |

McIver, P., 2005. Complex resonances in the water-wave problem for a floating structure. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 536: 423-443. DOI:10.1017/S0022112005005021 (  0) 0) |

Mustapa, M. A., Yaakob, O. B., Ahmed, Y. M., Rheem, C. K., Koh, K. K., and Adnan, F. A., 2017. Wave energy device and breakwater integration: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 77: 43-58. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.110 (  0) 0) |

Ning, D., Zhao, X. L., Zhao, M., Hann, M., and Kang, H., 2017. Analytical investigation of hydrodynamic performance of a dual pontoon WEC-type breakwater. Applied Ocean Research, 65: 102-111. DOI:10.1016/j.apor.2017.03.012 (  0) 0) |

Pérez-Collazo, C., Greaves, D., and Iglesias, G., 2015. A review of combined wave and offshore wind energy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 42: 141-153. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2014.09.032 (  0) 0) |

Renzi, E., Michele, S., Zheng, S. M., Jin, S. Y., and Greaves, D., 2021. Niche applications and flexible devices for wave energy conversion: A review. Energies, 14: 6537. DOI:10.3390/en14206537 (  0) 0) |

Simonetti, I., and Cappietti, L., 2021. Hydraulic performance of oscillating water column structures as anti-reflection devices to reduce harbour agitation. Coastal Engineering, 165: 103837. DOI:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2020.103837 (  0) 0) |

Sun, L., Eatock Taylor, R., and Choo, Y. S., 2011. Responses of interconnected floating bodies. The IES Journal Part A: Civil & Structural Engineering, 4(3): 143-156. (  0) 0) |

Wan, C., Yang, C., Bai, X., Bi, C., Chen, H., Chen, H., et al., 2023. Numerical investigation on the hydrodynamics of a hybrid OWC wave energy converter combining a floating buoy. Ocean Engineering, 281: 114818. (  0) 0) |

Wang, C., Xu, H., Zhang, Y., and Chen, W., 2023. Hydrodynamic investigation on a three-unit oscillating water column array system deployed under different coastal scenarios. Coastal Engineering, 184: 104345. DOI:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2023.104345 (  0) 0) |

Xu, C., and Huang, Z., 2018. A dual-functional wave-power plant for wave-energy extraction and shore protection: A wave-flume study. Applied Energy, 229: 963-976. (  0) 0) |

Zeng, X. H., Wang, Q., Shi, M., Kang, Y. S., and Yu, F. J., 2022. Hydrodynamic interactions between waves and cylinder arrays of relative motions composed of truncated floating cylinders with five degrees of freedom. Journal of Fluids and Structures, 115: 103785. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, H., Zhou, B., Zang, J., Vogel, C., Fan, T., and Chen, C., 2021. Effects of narrow gap wave resonance on a dual-floater WEC-breakwater hybrid system. Ocean Engineering, 225: 108762. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y., Li, M., Zhao, X., and Chen, L., 2020. The effect of the coastal reflection on the performance of a floating breakwater-WEC system. Applied Ocean Research, 100: 102117. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y., Zhao, X., Geng, J., Goteman, M., and Tao, L., 2022. Wave power extraction and coastal protection by a periodic array of oscillating buoys embedded in a breakwater. Renewable Energy, 190: 434-456. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, X. L., Ning, D. Z., Zou, Q. P., Qiao, D. S., and Cai, S. Q., 2019. Hybrid floating breakwater-WEC system: A review. Ocean Engineering, 186: 106126. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, X., Du, X., Li, M., and Goteman, M., 2021. Semi-analytical study on the hydrodynamic performance of an interconnected floating breakwater-WEC system in presence of the seawall. Applied Ocean Research, 109: 102555. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, X., Li, F., Zhou, J., Geng, J., Zou, Q., and Qin, D., 2023. Theoretical investigation of hydrodynamic performance of multi-resonant OWC breakwater array. Applied Ocean Research, 141: 103756. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, X., Li, Y., Zou, Q., Han, D., and Geng, J., 2022. Long wave absorption by a dual purpose Helmholtz resonance OWC breakwater. Coastal Engineering, 178: 104203. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, X., Ning, D., Zhang, C., and Kang, H., 2017. Hydrodynamic investigation of an oscillating buoy wave energy converter integrated into a pile-restrained floating breakwater. Energies, 10: 712. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., Li, M., and Johanning, L., 2020. Hydrodynamic performance of a Comb-Type Breakwater-WEC system: An analytical study. Renewable Energy, 159: 33-49. (  0) 0) |

Zheng, S., and Zhang, Y., 2018. Analytical study on wave power extraction from a hybrid wave energy converter. Ocean Engineering, 165: 252-263. (  0) 0) |

Zheng, S., Antonini, A., Zhang, Y., Greaves, D., Miles, J., and Iglesias, G., 2019. Wave power extraction from multiple oscillating water columns along a straight coast. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 878: 445-480. (  0) 0) |

Zheng, Y. H., Shen, Y. M., You, Y. G., Wu, B. J., and Jie, D. S., 2004. On the radiation and diffraction of water waves by a rectangular structure with a sidewall. Ocean Engineering, 31: 2087-2104. (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24