2) College of Food Science and Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China;

3) Ocean College of Hebei Agricultural University, Qinhuangdao 066000, China

The production of Ruditapes philippinarum, one of the most important economic shellfish species in many countries, was 4139157 tons in 2018 (FAO, 2020). Globally, capture production was 498131 tons and the export share of clam accounted for 1.12% of total aquatic product exports in 2018 (FAO, 2020).

The most prominent characteristic of aquatic products is their freshness, especially for finished products (Chen et al., 2020). Usually, freshness is used as a criterion to judge the quality of aquatic products. In the aquatic products consumption of residents, the fresh aquatic products accounted for a higher share. However, owing to geographical distribution and transportation conditions, many aquatic products are not compatible with long-distance fresh transportation. To ensure the freshness and improve the survival rate of fresh aquatic products during transportation, a reliable transporttation method must be adopted.

At present, the vehicles used for aquatic product transportation in the market are inadequate, due to simple equipment and a short distance transportation capacity, which are associated with a low survival rate and a serious loss of quality in fresh aquatic products (Zhang et al., 2019). Therefore, the provision of fresh and live shellfish products to consumers is a pressing issue, and it is necessary to study the transportation modes of aquatic products. In addition, the physiological changes in aquatic products during transportation and circulation in terms of the transportation mode should also be researched (Feng et al., 2019). Furthermore, to maintain the quality of live shellfish in circulation, a series of measures should be taken to reduce their metabolic activity. Zeng et al. (2013) studied the effects of storage temperature and cold acclimation on anhydrous preservation of crucian carp (Carassius auratus gibelio). They stored the crucian carp in two anhydrous incubators at 4℃ for 24 h and found that cold acclimation was helpful to maintain aerobic and anaerobic metabolism under anhydrous preservation and decreased the damage on blood oxidation. Mi et al. (2012) studied the quality and biochemical properties of artificially hibernated crucian carp under anhydrous preservation. These studies have provided an effective artificial hibernation procedure that can be applied to deliver live crucian carp with anhydrous preservation and transportation. Following this procedure, the quality and freshness of recovered crucian carp muscle remained unchanged, when compared to those of fresh samples. It has been reported that transportation time, temperature, humidity, and oxygen level also affect the physiology and quality of live shellfish (Buen-Ursua and Ludevese, 2011; Jiménez-Ruiz et al., 2013; Barrento and Powell, 2016). Thus, from the perspective of supply chain connection, studying the impact of transportation conditions on the quality of live shellfish, exploring the key quality indicators and their restrictions, and establishing a scientific transportation method for live shellfish are crucial.

Recently, living preservation and transportation have attracted a lot of attentions, aiming at improving the quality and value of aquatic products supply chain. The effect of transport strategies on the survival and the microbiologic and physiologic characteristics of shellfish have been reported (Anacleto et al., 2013a, 2013b). However, no studies have investigated the effects of anhydrous transportation and watery transportation modes on clam physiology, in terms of variations in refrigeration ventilation and spray design of transport containers. Therefore, it is necessary to explore modifications in the transporting vehicle and to identify the optimal conditions for live transportation.

In this study, refrigeration ventilation and spray design of transport containers were tweaked. Basing on the variation, we examined the physiological responses of clams including the survival rate, condition index, and the glycogen and nucleotide content under different transportation modes. Furthermore, we investigated the effects of different temperatures (4 and 15℃) on the physiological responses of clam. The results from this study can facilitate meeting the requirements of sustainable transportation of fresh seafood, such as oysters, scallops, and clams, and the requirements of long-distance, sustainable transportation.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Sample CollectionOne hundred kilograms of living one-year-old shellfish (R. philippinarum) with mean shell length of 25.4 mm ± 1.42 mm, width of 19.37 mm ± 1.26 mm, height of 20.23 mm ± 1.65 mm, and weight of 4.18 g ± 0.58 g were harvested from a farm in Jiaozhou Bay in Qingdao City, China (35˚35΄ – 37˚09΄N, 119˚30΄ – 121˚00΄E). All clams were harvested in August 2019 with similar size.

2.2 Simulated Transport ConditionsThe harvested clams were sampled immediately on site and then treated with liquid nitrogen (HA stage). The clams were then transported to the laboratory on ice (4℃, T-Lab stage). Upon arrival, the clams were segregated into four tanks (Table 1). Two tanks were used to simulate anhydrous transport conditions at 4℃ and 15℃ respectively. The clams to be placed in anhydrous transport conditions were packed in net bags and placed inside a container in which humidity was maintained using a spray system. A container monitoring system was used to monitor the temperature and moisture of the chambers. The other two tanks were used to simulate watery transportation at 4℃ and 15℃ respectively. The temperature levels of the chambers were monitored using thermometers and data loggers. During the experimental period, the clams were not fed and underwent a photoperiod of 12-h light and 12-h dark cycle. The transport simulation was carried out for 3 d (T-1, T-2, T-3 stage). During the whole process of the experiment, the animals were handled carefully to avoid any damage caused by human intervention. The samples were collected every 24 h. One hundred clams from the tanks were sampled initially to evaluate the survival rate; 30 specimens were randomly collected and measured to evaluate the condition index; and 150 live clams were immediately dissected. For the biochemical/physiological analyses, clam tissues were treated with liquid nitrogen and immediately frozen at −80℃ for nucleotide and glycogen analyses. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

|

|

Table 1 Conditions and methods for live clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) transportation |

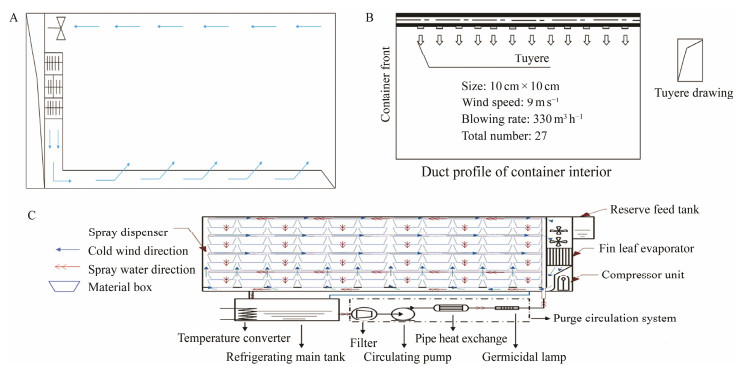

The simulated transport systems were categorized into an anhydrous transportation system and a watery transportation system. A container was used for anhydrous transport. To satisfy the living transportation environment of the shellfish, the container was modified as shown in Fig.1. Additionally, a water temperature control circulation system was established for the watery transportation (Fig.2).

|

Fig. 1 Floor plan of the container. A is the air circulation and air distribution of original container, B is the air supply scheme for refitted refrigerated containers, and C is the shellfish truck-mounted transport system. |

|

Fig. 2 The aquaculture systems (circulating water). |

The survival rate was based on the method reported by Goncalves and Nunes (2009). Briefly, 100 samples were inspected at 8:00 am every day. The clams were placed in seawater and left to rest for 1 h at 15℃. The survival rates of the clams were determined by observing their valves. The individual was recognized as alive when the shell valve closed for 30 s. Conversely, if the clam shells were open, the clam shell was tapped with a glass rod to observe the reaction of the clam shell. The clam was considered dead if the shell remained open for a long time. The survival rate was calculated with Eq. (1):

| $ {\text{Survival rate (%)}} = \frac{{{\text{Live animals}}}}{{{\text{Total animals}}}} \times 100. $ | (1) |

The glycogen content analysis was performed using a glycogen analysis kit (Beyotime; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) following manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, fresh soft tissue was drained with filter paper and weighed after rinsing with normal saline. The samples containing the alkaline solution were homogenized at a rate of 1:3 (w/v) and placed in a boiling water bath for 20 min. In order to prevent water evaporation, a preservative film was used to tie the end of the tube, and a small hole was made on the film with a needle for gas to expand and contract in cold and hot conditions. Then, the samples were cooled to room temperature using running water. After adding the developer, the samples were placed in a boiling water bath for another 5 min. A WFJ 7200 spectrophotometer (Unico Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used to determine the glycogen concentration after cooling. Glycogen content was estimated using an equivalent glucose standard by measuring the absorbance of the samples at 620 nm. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.6 Analysis of the Condition IndexThe condition index (CI) was determined based on a method reported by Mercado-Silva (2005). The weight, shell length, shell height, and shell width of clams (about 20 samples) were measured. The CI for wet tissue was calculated according to Eq. (2) (Bi et al., 2021a):

| $ CI = \frac{{{\text{Weight}}}}{{{\text{Shell length}} \times {\text{Shell height}} \times {\text{Shell width}}}} \times 100. $ | (2) |

ATP-related compounds extraction was performed following a method reported by Bi et al. (2021b). The sample (5.00 g) was mixed with 15 mL of 5% cold perchloric acid for 30 s, and the mixture was placed in a 4℃ refrigerator for 30 min after homogenization. Subsequently, the homogenate was centrifuged at 5000 r min−1 for 10 min (4℃) and the supernatant was maintained at 4℃. The precipitate was also centrifuged at the same conditions and the additional supernatant obtained was combined with the previous supernatant. Subsequently, 10 mol L−1 and 1 mol L−1 potassium hydroxide were used to neutralize the processed samples to pH 6.70, and the samples were then diluted to a final volume of 50 mL with Milli-Q purified water (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) and filtered (0.22-μm pore size). A 1260 high-performance liquid chromatography system (HPLC; Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to analyze the ATP-related compounds content. A 10-μL portion of the filtrate was injected onto a CAPCELL PAK C18 SG120 S5 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm; Shiseido Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The temperature was maintained at 40℃. A mixture of 20 mmol L−1 acetic acid, 20 mmol L−1 citric acid, and 40 mmol L−1 triethylamine was used as the eluent and was neutralized to pH 4.80 with 10 mol L−1 and then 1 mol L−1 potassium hydroxide. The detector wavelength was 260 nm, and the flow rate was 0.8 mL min−1. An ATP-related compounds standard was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). By comparing the retention times and peak areas of each sample with the nucleotide standard, the identity and quantity of the ATP-related compounds were assessed. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Adenylate energy charge (A.E.C.) (Hu et al., 2013) was calculated using Eq. (3):

| $ A.E.C.{\text{ (%)}} = \frac{{{\text{ATP}} + 0.5{\text{ADP}}}}{{{\text{ATP}} + {\text{ADP}} + {\text{AMP}}}} \times 100. $ | (3) |

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan's multiple range test were used to analyze the ATP-related compounds, free amino acids, survival rate, CI, and glycogen content of the clams. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. MetaboAnalyst 4.0 was used to perform the principal component analysis (PCA) and correlation analysis (Dong et al., 2020). The experimental data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and all experiments were performed in triplicate.

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 Simulated Transport SystemsThe transformation of the container is shown in Fig.1 and Table 2. Few modifications were made during the transformation. First, the direction of the air supply inside the container was changed from the original single direction (Fig.1A) to multiple directions (Figs.1B and C). This is because a single wind direction can only control the temperature of the clams at the edges effectively, and the clams in the center of the container cannot be subjected to temperature control. This might make the clams located in the middle of the container vulnerable to heat and bacterial infections. Wind from multiple directions provided a comprehensive wind supply, can also allow the clams in the middle of the container to cool down, and reduce the bacterial growth, which in turn can reduceclam mortality. Second, a spray system, which had 27 sprinklers, was added to the top of the container. The sprayers sprayed out a mist of water vapor, which was used to maintain the moisture inside the container during transportation. Third, a monitoring system was used in the process of clam transportation. The detection system included temperature and humidity sensors, which contained 54 probes evenly inserted into the shipping container. A detection system was used to detect the temperature and humidity in each part of the container. In addition, an automatic cooling temperature control system replaced the traditional method of adding an ice plate. Anhydrous and lowtemperature technologies have the advantages of low cost and low pollution. Temperature control is the key to anhydrous transportation, and it often requires a relatively stable cold source. In most cases, ice, which is used as a cold source for domestic transport vehicles, has the disadvantages of large consumption and difficult storage (Harmon, 2009; Fotedar and Evans, 2011). The modifications made in the container increased the transportation space and decreased transportation costs.

|

|

Table 2 Performance index of long-distance cold chain control system for shellfish |

At present, certain problems such as uncontrollable temperature and humidity, uneven temperature distribution, compressed stacking causing crushing of shellfish seedlings, and high mortality rates during transportation seriously affect the development of the clam industry (Varsamos et al., 2006; Ben-Asher et al., 2019, 2020). According to the national requirements for the construction of the shellfish industry system, combined with the characteristics and advantages of conventional cold-chain logistics by the collaboration of each professional scientific research worker to existing refrigerated containers to be modified. The refrigerated container was modified at each internal and functional module to maintain a constant low temperature and a moist environment during the transport process. These modifications were made to maintain the transportation environment of fresh seafood such as oysters, scallops, and clams and to meet the long-distance transportation requirements for the maintenance of fresh and live seafood.

As shown in Fig.2, a water temperature control circulation system was established. This system could prevent the water temperature from changing with the ambient temperature. Sterilization and filtration devices have also been added. Shellfish activities can speed up the metabolism and increase excreta, which will accelerate the deterioration of water quality and increase wastage. Circulating water can effectively reduce bacterial growth, ensuring the survival of clams.

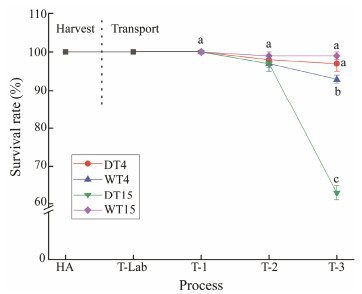

3.2 Survival Rate of Clams During ExperimentThe change in clam survival rate during harvest and transport is shown in Fig.3. The survival rate ranged from 100% to 63% throughout the harvest and the transport stages. At the harvest stage, the survival rate was 100%, and mortality did not occur initially at the beginning of the transport stage. However, 3 d after transportation, a significant difference (P < 0.05) in the survival rate was observed. In the anhydrous transport groups, the clams at 4℃ had a higher survival rate (97%) than those at 15℃ (63%). The reason might be that the temperature of 4℃ is closer to the ecological ice temperature of clams. At this temperature, clams are in a dormant or semi-dormant state with weak metabolic activities and can maintain their life vitality for a long time (Anacleto et al., 2014; Bi et al., 2021c). Studies have reported that a low transport temperature (4℃) can prolong the survival rates of Venerupis pullastra and R. philippinarum for approximately 2 and 10 days, respectively (Anacleto et al., 2013a). Buen-Ursua and Ludevese (2011) evaluated the survival rate of abalone fry by using polyethylene containers with different ice contents (5, 10, and 20 g L−1) according to the actual logistics process. The results showed that the survival rate of both groups subjected to simulated transport for 8 h and 10 h was 100%. In addition, Mi et al. (2012) reported that in the anhydrous preservation process, the artificial hibernating life span of crucian carp was 38 h through the combined effect of anesthesia and low temperature. However, when shellfish completely live out of the water and are stressed by the environment at the high temperatures of anhydrous transport, the immunity of shellfish is reduced and bacteria are more likely to accumulate, which result in an increase in the mortality of clams (Anacleto et al., 2013b). Gooch et al. (2002) reported that the growth of Vibrio spp. in shellfish rapidly increases when exposed to high temperatures, whereas it can be inhibited at chilling temperatures.

|

Fig. 3 Survival rate of clams subjected to different treatments. HA, the harvest stage of clams; T-Lab, the transportation to the laboratory stage; T-1, the simulate transport for 1 d; T-2, the simulate transport for 2 d; T-3, the simulate transport for 3 d. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different (P < 0.05). |

For the watery transportation groups at the later stage, a higher survival rate was observed at 15℃ (99%) than that at 4℃ (93%). It was found that 15℃ was a relatively comfortable environment for clams in a watery environment, which were active and consumed a lot of energy. Furthermore, in a watery environment, clams can perform aerobic respiration, and the circulation water system plays a role in purification by reducing the growth of bacteria. On the other hand, a low water temperature could cause discomfort to shellfish and even death.

It is known that when bivalves are kept in a humid and cold environment, they can survive for a long time without water due to decreased metabolism and a subsequent decrease in excretion products (Quinta and Nunes, 2001). In addition, such conditions can inhibit the growth of microorganisms, enzymatic deterioration reactions, and food spoilage (Anacleto et al., 2013b). This can be an important factor in the clam's strategy to survive longer in anhydrous transportation. In this study, a significant influence of transport temperature and mode on clam survival rate was observed. These differences were observed only after 3 d of transportation. The two modes of transportation resulted in different clam survival rates.

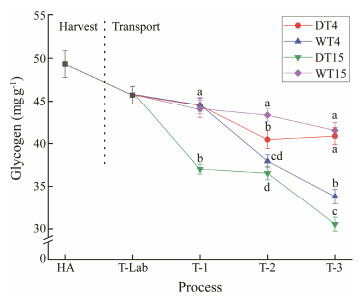

3.3 Glycogen Content AnalysisThe changes in the glycogen content of the clams are shown in Fig.4. Glycogen content decreased from the harvest stage to the end of transportation. Glycogen is the main carbohydrate reserve of bivalves, and the level of glycogen can reflect the ability of shellfish to maintain their basic survival and cope with persistent stress factors under stressful conditions (Patrick et al., 2006). Therefore, glycogen content was decreased to provide energy for the clams during the experimental period. In the anhydrous transport process, glycogen content was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the 4℃ group than in the 15℃ group. It could be speculated that 4℃ was close to the ecological ice temperature and the clams were in a dormant state. Therefore, the clams did not use their metabolic reserves when they were maintained at 4℃. In contrast, the clams were stressed by the surrounding environment when they were exposed to air at 15℃ and the glycogen content decreased to maintain energy. It has been reported that glycogen is mainly used to maintain animal survival under stressful conditions (Liu et al., 2020). Anacleto et al. (2013a) indicated that V. pullastra did not use their metabolic reserves when were kept at 4℃ compared to that at 22℃, as was the case for R. philippinarum.

|

Fig. 4 Glycogen of clams subjected to different treatments. HA, the harvest stage of clams; T-Lab, the transportation to the laboratory stage; T-1, the simulate transport for 1 d; T-2, the simulate transport for 2 d; T-3, the simulate transport for 3 d. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different (P < 0.05). |

In the watery transportation process, a significantly lower (P < 0.05) glycogen content was observed in the 4℃ group than in the 15℃ group, excluding the first day. It follows that the clams had a strong emergency response at 4℃, leading to a high level of glycogen consumption. In contrast, 15℃ was a relatively comfortable environment temperature, and the clams were not subjected to environmental stress in such an environment, which resulted in a little effect on the glycogen content.

According to the current research results, glycogen content seems to be a good physiological indicator of clams. Uzaki et al. (2003) reported a similar conclusion in R. Philippinarum exposed to oxygen-deficient waters. Li et al. (2007) indicated that reduction or depletion of metabolic reserves such as glycogen was often associated with a large number of mortalities in adult Crassostrea gigas. Albentosa et al. (2007) indicated that glycogen was the main energy source for clams during the days following starvation.

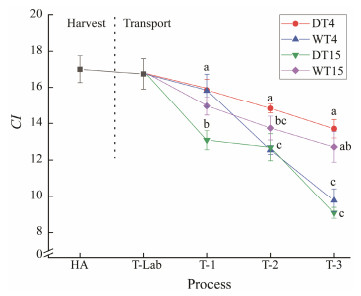

3.4 Condition Index AnalysisFig.5 shows the changes in the CI in the transport-simulated clams at different temperatures. The CI is commonly used as an indicator to assess the effect of the environment on bivalve health status and summarize the physiological/nutritional status (Mercado-Silva, 2005). The CI changed slightly initially. During the 3 d duration, the CI showed a generally decreasing trend in both the anhydrous transport and the watery transportation. A significantly higher (P < 0.05) CI level was observed at 4℃ than at 15℃ in the anhydrous transportation. The results of this study show that long periods of extremely low oxygen during transportation could exert pressure on bivalves, especially at higher temperatures. Laing and Spencer (2006) reported that higher temperatures could crack the mantle cavity of shellfish and lead to the decline of CI, which could lead to the death of animals. Similar results were found by Anacleto et al. (2013), who indicated that the CI was strongly influenced by the transport temperature, and the CI of clams at 22℃ decreased faster than that at 4℃. Pampanin et al. (2005) conducted a similar study. They considered that the CI was a beneficial physiological indicator for the mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) health status when the mussel was exposed to air.

|

Fig. 5 Condition index (CI) of clams subjected to different treatments. HA, the harvest stage of clams; T-Lab, the transportation to the laboratory stage; T-1, the simulate transport for 1 d; T-2, the simulate transport for 2 d; T-3, the simulate transport for 3 d. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different (P < 0.05). |

During the watery transport, the CI at 15℃ was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that at 4℃, except for the first day. The results indicated that the CI was strongly influenced by the temperature in the watery transportation. Mccrickard (2012) indicated that the CI has a significant influence (P < 0.05) on seasonal change. Their study revealed high CI values in specimens collected in late spring and late autumn. Moreover, Clements et al. (2018) indicated that CI was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in June than in July.

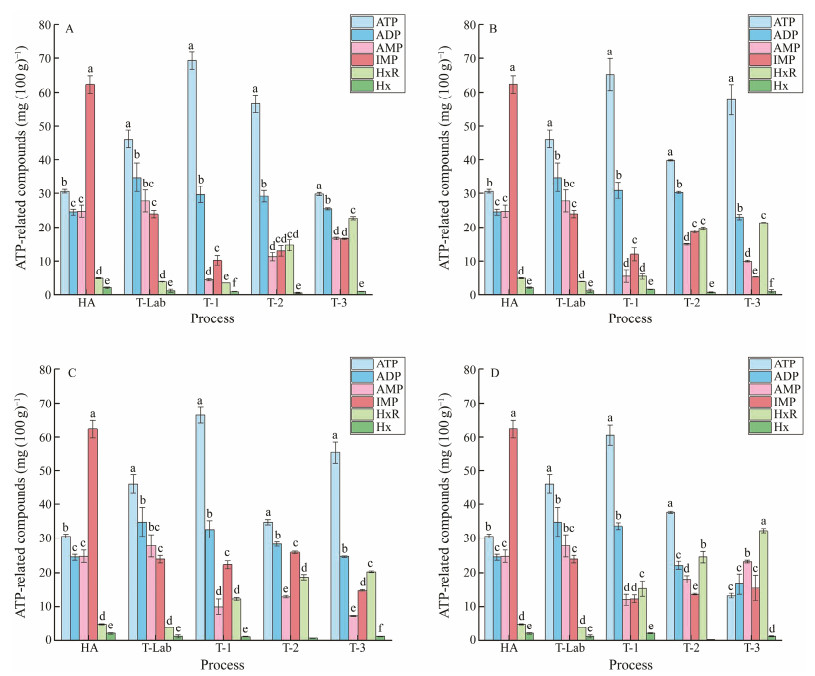

3.5 Identification and Quantification of ATP-Related CompoundsThe concentrations and species of ATP-related compounds in the clams were assessed (Fig.6). ATP and ADP were the most prominent nucleotides in the clams, whereas very low concentrations of Hx were detected in all the treatments. In the HA stage, the ATP, ADP and AMP contents showed no significant differences, and the IMP content was significantly higher (P < 0.05), while the HxR and Hx contents were significantly lower (P < 0.05) than other ATP-related compounds contents. It could be speculated that the clams were subjected to the stress of the artificial harvest during the HA stage, and IMP temporarily accumulated because of the catabolism of ATP by endogenous enzymes in molluscs normally at the beginning. Compared with the HA stage, the ATP, ADP, and AMP contents showed an increasing trend, and the IMP content showed a decreasing trend at the T-Lab stage, while the HxR and Hx contents did not significantly change. It could be speculated that the degradation pathway of ATP-related compounds from ATP to Hx did not work in that way since the clams are alive. The metabolic pathway of ATP in live animals should be a recycle from ATP to ATP.

|

Fig. 6 Nucleotides of clams subjected to different treatments. A is the DT4 group, B is the WT4 group, C is the WT15 group, and D is the DT15 group. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different (P < 0.05). |

During the transportation period, the nucleotide content significantly changed in all the treatment groups. During the anhydrous transport period, the ATP and ADP contents first increased, and then decreased, and in the T-1 stage, the highest ATP and ADP contents were observed. A significantly higher (P < 0.05) ATP content was observed in the DT4 group than that in the DT15 group. The AMP and IMP contents decreased first and increased later, and in the T-1 stage, the lowest AMP and IMP contents were observed. The AMP content was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the DT15 group than that in the DT4 group. In addition, the HxR content was initially low but increased during transportation, particularly in the DT15 group, because the breakdown from IMP to HxR was reported to be related to enzymatic activity and bacterial growth (Quinta and Nunes, 2001). It is suggested that ATP catabolism and the decomposition products were affected by the higher temperature that existed during the anhydrous transportation, as high temperatures could accelerate ATP degradation. The Hx content did not change significantly. During the watery transportation period, all the nucleotide contents, except IMP, were not significantly different between the two temperatures.

ATP and its decomposition products are the main components of nucleotides in aquatic animal muscles. They actively participate in muscle metabolism and provide energy for physiological processes (Boulais et al., 2017). There have been many studies on the degradation pathways in the muscles of fish and shellfish locally and abroad, and the pathway of ATP degradation was reported to be: ATP → ADP → AMP → IMP → HxR → Hx (Wang et al., 2007; Hong et al., 2017). Our results also showed that the ATP degradation pathway was ATP → ADP → AMP → IMP → HxR → Hx. This process involves the action of ATPase, ATP-phosphate kinase, AMP-deaminase, 5'-nucleotide enzyme, and nucleoside phosphorylase (Kuda et al., 2007). Studies have reported that the main reason for degradation of ATP to IMP is the endogenous autolysin activity (Davis et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021), while the degradation of IMP to HxR and Hx was related to enzyme activity and bacterial growth (Li et al., 2021). In our study, Hx and HxR increased during the transport period, and significantly higher levels of Hx and HxR were observed at 4℃ than at 15℃. Therefore, although the HxR and Hx contents were very low, accumulation of Hx and HxR was observed during the simulated transport period. Notably, these compounds can be used as stress indicators. This result is similar to the findings of Anacleto et al. (2013a).

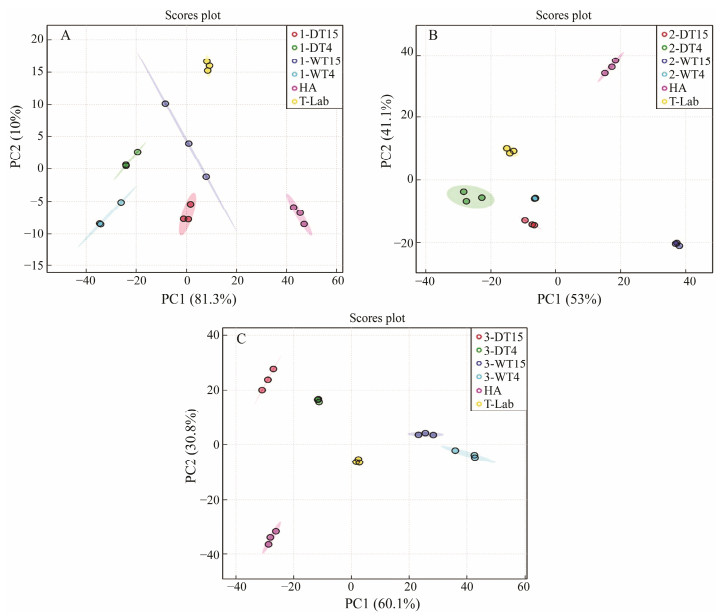

PCA was used to evaluate the differences among the ATPrelated compounds in the clams. Fig.7A shows the differrence between the harvest and the first day of transport in different modes. The results showed that the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) shared 81.3% and 10% of the gross change, respectively, representing 91.3% of the total variance. Fig.7B shows the difference between the harvest and the second day of transport in different modes. The results showed that PC1 and PC2 shared 53% and 41.1% of the gross change, respectively, representing 94.1% of the total variance. Fig.7C shows the difference between the harvest and the third day of transport in different modes. The results showed that PC1 and PC2 shared 60.1% and 30.8% of the gross change, respectively, representing 90.9% of the total variance. On the basis of the score values of PC1 and PC2, the ATP-related compounds in the clams at the harvest stages could be well distinguished from the transport stage.

|

Fig. 7 Principal component analysis (PCA) of nucleotides in clams subjected to different treatments. A is at the first day, B is at the second day, and C is at the third day. |

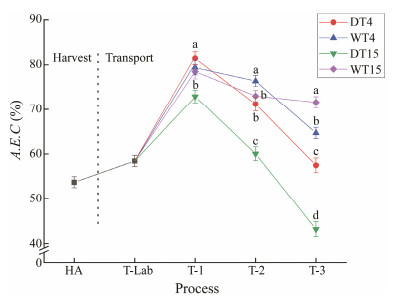

Fig.8 shows the A.E.C. values in the clams in both the anhydrous and the watery transportations. At the beginning of the treatment, the A.E.C. value was significantly lower (P < 0.05) and increased on the first day; in contrast, the A.E.C. value decreased after 2 d. The A.E.C. values of all the treatments, except for the DT15 group, were higher than 50%.

|

Fig. 8 A.E.C. (%) values of clams subjected to different treatments. HA, the harvest stage of clams; T-Lab, the transportation to the laboratory stage; T-1, the simulate transport for 1 d; T-2, the simulate transport for 2 d; T-3, the simulate transport for 3 d. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different (P < 0.05). |

Previous studies recommended that the A.E.C. value could be used as a recovery index for shellfish (Mørkøre et al., 2010). It has been reported that shellfish were in a recoverable state when the A.E.C. value was higher than 50% (Bi et al., 2021b). In our study, clams under all conditions, except for the DT15 group, showed recovery after transport for 3 days.

4 ConclusionsIn this study, the container holding clams was transformed, and a water circulation temperature control system was established. The qualities of the clams that were transported in different ways were compared based on the modified container and the temperature control system. All physiological responses measured in this study described the status of clams in the logistics chain in detail and accurately. The results demonstrated that the clams of the DT4 group had a higher survival rate than that of the DT15 group. The clams of the DT4 group showed a better pattern in these parameters (levels of CI, nucleotides, and glycogen) than those in the DT15 group. Additionally, in the watery transportation group, the survival rate, CI, glycogen content and A.E.C. values of clams generally showed a higher value in the WT15 group than in the WT4 group, which indicated that the WT15 and WT4 clams have different physiological requirements. Thus, anhydrous transportation at 4℃ was the most suitable method for this study. Overall, this study could be particularly useful for establishing shellfish transportation systems.

AcknowledgementsThis study is supported by the National Key R & D Pro-gram of China (No. 2018YFD0901004), the Innovation Team Project of Hebei Province Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (No. HBCT2018170207), the Innovation Center of Hebei Agricultural Products Processing Technology (No. 199676183H), and the Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (No. CARS-49).

Albentosa M., Fernandez-Reiriz M. J., Labarta U., Perez-Camacho A.. 2007. Response of two species of clams, Ruditapes decussatus and Venerupis pullastra, to starvation: Physiological and biochemical parameters. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 146(2): 241-249. DOI:10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.10.109 (  0) 0) |

Anacleto P., Maulvault A. L., Barrento S., Mendes R., Nunes M. L., Rosa R., et al. 2013a. Physiological responses to depuration and transport of native and exotic clams at different temperatures. Aquaculture, 408-409: 136-146. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.05.035 (  0) 0) |

Anacleto P., Maulvault A. L., Chaguri M., Pedro S., Nunes M. L., Rosa R., et al. 2013b. Microbiological responses to depuration and transport of native and exotic clams at optimal and stressful temperatures. Food Microbiology, 36(2): 365-373. DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2013.07.002 (  0) 0) |

Anacleto P., Maulvault A. L., Barrento S., Mendes R., Nunes M. L., Rosa R., et al. 2014. Effect of warming on protein, glycogen and fatty acid content of native and invasive clams. Food Research International, 64: 439-445. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2014.07.023 (  0) 0) |

Barrento S., Powell A.. 2016. The effect of transportation and re-watering strategies on the survival, physiology and batch weight of the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis. Aquaculture, 450: 194-198. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.07.021 (  0) 0) |

Ben-Asher R., Lahav O., Mayer H., Nahir R., Birnhack L., Gendel Y.. 2020. Proof of concept of a new technology for prolonged high-density live shellfish transportation: Brown crab as a case study. Food Control, 114: 107239. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107239 (  0) 0) |

Ben-Asher R., Ravid S., Ucko M., Smirnov M., Lahav O.. 2019. Chlorine-based disinfection for controlling horizontal transmission of VNN in a seawater recirculating aquaculture system growing European seabass. Aquaculture, 510: 329-336. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.06.001 (  0) 0) |

Bi S., Chen L., Sun Z., Wen Y., Xue Q., Xue C., et al. 2021a. Physiological responses of the triploid Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) to varying salinities of aquaculture seawater. Aquaculture Research, 52(6): 2907-2914. DOI:10.1111/are.15117 (  0) 0) |

Bi S., Chen L., Sun Z., Wen Y., Xue Q., Xue C., et al. 2021b. Investigating influence of aquaculture seawater with different salinities on non-volatile taste-active compounds in Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas). Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 15(2): 2078-2087. DOI:10.1007/s11694-020-00807-4 (  0) 0) |

Bi S., Xue C., Sun C., Chen L., Sun Z., Xu L., et al. 2021c. Impact of transportation and rehydration strategies on the physiological responses of clams (Ruditapes philippinarum). Aquaculture Reports, 22: 10976. (  0) 0) |

Boulais M., Soudant P., Le Goïc N., Quéré C., Boudry P., Suquet M.. 2017. ATP content and viability of spermatozoa drive variability of fertilization success in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas). Aquaculture, 479: 114-119. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2017.05.035 (  0) 0) |

Buen-Ursua S. M. A., Ludevese G.. 2011. Temperature and size range for the transport of juvenile donkey's ear abalone Haliotis asinina Linne. Aquaculture Research, 42(8): 1206-1213. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2109.2010.02712.x (  0) 0) |

Chen J., Lu Y., Yan F., Wu Y., Huang D., Weng Z.. 2020. A fluorescent biosensor based on catalytic activity of platinum nanoparticles for freshness evaluation of aquatic products. Food Chemistry, 310: 125922. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125922 (  0) 0) |

Chen S., Zhang C., Xiong Y., Tian X., Liu C., Jeevithan E., et al. 2015. A GC-MS-based metabolomics investigation on scallop (Chlamys farreri) during semi-anhydrous living-preservation. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 31: 185-195. (  0) 0) |

Clements J. C., Davidson J. D. P., McQuillan J. G., Comeau L. A.. 2018. Increased mortality of harvested eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) is associated with air exposure and temperature during a spring fishery in Atlantic Canada. Fisheries Research, 206: 27-34. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2018.04.022 (  0) 0) |

Davis P. R., Miller S. G., Verhoeven N. A., Morgan J. S., Tulis D. A., Witczak C. A., et al. 2020. Increased AMP deaminase activity decreases ATP content and slows protein degradation in cultured skeletal muscle. Metabolism, 108: 154257. DOI:10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154257 (  0) 0) |

Dong M., Qin L., Ma L. X., Zhao Z. Y., Du M., Kunihiko K., et al. 2020. Postmortem nucleotide degradation in turbot mince during chill and partial freezing storage. Food Chemistry, 311: 125900. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125900 (  0) 0) |

FAO, 2020. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in Action. Rome, 206pp, https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en.

(  0) 0) |

Feng H., Chen J., Zhou W., Rungsardthong V., Zhang X.. 2019. Modeling and evaluation on WSN-enabled and knowledge-based HACCP quality control for frozen shellfish cold chain. Food Control, 98: 348-358. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.11.050 (  0) 0) |

Fotedar S., Evans L.. 2011. Health management during handling and live transport of crustaceans: A review. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 106(1): 143-152. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2010.09.011 (  0) 0) |

Goncalves A., Pedro S. N., Duarte A., Nunes M. L.. 2009. Effect of enriched oxygen atmosphere storage on the quality of live clams (Ruditapes decussatus). International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 44(12): 2598-2605. (  0) 0) |

Gooch J. A., DePaola A., Bowers J., Marshall D. L.. 2002. Growth and survival of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in postharvest American oysters. Journal of Food Protection, 65: 970e. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-65.6.970 (  0) 0) |

Harmon T. S.. 2009. Methods for reducing stressors and main-taining water quality associated with live fish transport in tanks: A review of the basics. Reviews in Aquaculture, 1(1): 58-66. DOI:10.1111/j.1753-5131.2008.01003.x (  0) 0) |

Hong H., Regenstein J. M., Luo Y.. 2017. The importance of ATP-related compounds for the freshness and flavor of postmortem fish and shellfish muscle: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57(9): 1787-1798. (  0) 0) |

Hu Y., Zhang J., Ebitani K., Konno K.. 2013. Development of simplified method for extracting ATP-related compounds from fish meat. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi, 79(2): 219-225. DOI:10.2331/suisan.79.219 (  0) 0) |

Jiménez-Ruiz E. I., Ocaño-Higuera V. M., Maeda-Martínez A. N., Varela-Romero A., Márquez-Ríos E., Muhlia-Almazán A. T., et al. 2013. Effect of seasonality and storage temperature on rigor mortis in the adductor muscle of lion's paw scallop Nodipecten subnodosus. Aquaculture, 388-391: 35-41. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.01.006 (  0) 0) |

Kuda T., Fujita M., Goto H., Yano T.. 2007. Effects of freshness on ATP-related compounds in retorted chub mackerel Scomber japonicus. LWT – Food Science and Technology, 40(7): 1186-1190. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2006.08.009 (  0) 0) |

Laing, I., and Spencer, B. E., 2006. Bivalve cultivation: Criteria for selecting a site. Cefas Science Series Technical Report No. 136. Lowestof, 34pp.

(  0) 0) |

Li J., Zhou G., Xue P., Dong X., Xia Y., Regenstein J., et al. 2021. Spoilage microbes' effect on freshness and IMP degradation in sturgeon fillets during chilled storage. Food Bioscience, 41: 101008. DOI:10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101008 (  0) 0) |

Li S., Zhang T., Feng Y., Sun J.. 2021. Extracellular ATPmediated purinergic immune signaling in teleost fish: A review. Aquaculture, 537: 736511. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736511 (  0) 0) |

Li Y., Qin J. G., Abbott C. A., Li X., Benkendorff K.. 2007. Synergistic impacts of heat shock and spawning on the physiology and immune health of Crassostrea gigas: An explanation for summer mortality in Pacific oysters. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 293(6): R2353-2362. DOI:10.1152/ajpregu.00463.2007 (  0) 0) |

Liu S., Li L., Wang W., Li B., Zhang G.. 2020. Charac-terization, fluctuation and tissue differences in nutrient content in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) in Qingdao, northern China. Aquaculture Research, 51(4): 1353-1364. DOI:10.1111/are.14463 (  0) 0) |

Mccrickard, B. M., 2012. A study of the eastern oyster, Crasso-strea virginica, in Tampa Bay: Effects of Perkinsus marinus on reproduction and condition. Master thesis. University of South Florida.

(  0) 0) |

Mercado-Silva N.. 2005. Condition index of the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin, 1791) in Sapelo Island Georgia – Effects of site, position on bed and pea crab parasitism. Journal of Shellfish Research, 24(1): 121-126. DOI:10.2983/0730-8000(2005)24[121:CIOTEO]2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Mi H., Qian C., Mao L.. 2012. Quality and biochemical properties of artificially hibernated crucian carp for waterless preservation. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 38(6): 1721-1728. DOI:10.1007/s10695-012-9669-2 (  0) 0) |

Mørkøre T., Rødbotten M., Vogt G., Fjæra S. O., Kristiansen I. Ø., Manseth E.. 2010. Relevance of season and nucleotide catabolism on changes in fillet quality during chilled storage of raw Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Food Chemistry, 119(4): 1417-1425. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.022 (  0) 0) |

Pampanin D. M., Volpato E., Marangon I., Nasci C.. 2005. Physiological measurements from native and transplanted mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) in the canals of Venice. Survival in air and condition index. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Molecular and Integrative Physiology, 140(1): 41-52. DOI:10.1016/j.cbpb.2004.10.016 (  0) 0) |

Patrick S., Faury N., Goulletquer P.. 2006. Seasonal changes in carbohydrate metabolism and its relationship with summer mortality of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg) in Marennes-Oléron Bay (France). Aquaculture, 252(2-4): 328-338. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.07.008 (  0) 0) |

Quinta R. M. R., Nunes M. L.. 2001. Changes in baseline levels of nucleotides during ice storage of fish and crustaceans from the Portuguese coast. European Food Research and Technology, 212: 141-146. DOI:10.1007/s002170000222 (  0) 0) |

Uzaki N., Kai M., Aoyama H., Suzuki T.. 2003. Changes in mortality rate and glycogen content of the Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum during the development of oxygen-deficient waters. Fisheries Science, 69: 936-943. DOI:10.1046/j.1444-2906.2003.00710.x (  0) 0) |

Varsamos S., Flik G., Pepin J. F., Bonga S. E., Breuil G.. 2006. Husbandry stress during early life stages affects the stress response and health status of juvenile sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Fish Shellfish Immunology, 20(1): 83-96. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2005.04.005 (  0) 0) |

Wang Q., Xue C., Li Z., Fu X., Xu J., Xue Y.. 2007. Changes in the contents of ATP and its related breakdown compounds in various tissues of oyster during frozen storage. Journal of Ocean University of China, 6(4): 407-412. DOI:10.1007/s11802-007-0407-9 (  0) 0) |

Zeng P., Chen T., Shen J.. 2013. Effects of cold acclimation and storage temperature on crucian carp (Carassius auratus gibelio) in a waterless preservation. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 40(3): 973-982. (  0) 0) |

Zhang Y., Wang W., Yan L., Glamuzina B., Zhang X.. 2019. Development and evaluation of an intelligent traceability system for waterless live fish transportation. Food Control, 95: 283-297. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.08.018 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22