2) Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao 266037, China;

3) School of Marine Sciences, University of Maine, Orono, Maine 04469, USA

A central issue of community ecology is to understand why some species, but not others, are observed in a biological community on a certain spatial and temporal scale (Morin, 2011). Although niche differentiation is considered as a key factor in the coexistence of plant species (Tilman, 1984; Grubb, 2010), the important role of niche differentiation in species coexistence is also expressed by some ecologists in varying degrees of skepticism. Functional traits of species are more important than environment or evolutionary relatedness in determining the plant species co-occurrence pattern (Soliveres et al., 2014). Generally, some possible mechanisms for community assembly have been proposed, including the effects of competition, complex relationships between species niches and environmental heterogeneity, and favored and/or unfavored species combination on the co-occurrence patterns of communities (Diamond, 1975). Additionally, different factors may play a major role in structuring fish communities, such as predation and environmental factors (Englund et al., 2009; Giam and Olden, 2016).

A null model analysis is an important statistical test based on the randomization of ecological data or random sampling from a known or imagined species distribution (Gotelli, 2000), and it has been extensively applied to examine the co-occurrence patterns of different animal or plant communities. For example, null model analysis indicates that competitive exclusion is strong among distantly related species in co-occurrence patterns for Bornean vertebrates (Beaudrot et al., 2013); co-occurrence patterns of species composition are random and unstructured for ectoparasites assemblage (Gotelli and Rohde, 2002); and competitive interaction plays an important role in community assembly for the forest trees (Rooney, 2008). Null models are used to study the species co-occurrence of fish communities in lakes in Ontario (Jackson et al., 1992), stream fish communities (Yant and Karr, 1984; Peres-Neto, 2004), demersal fishes in a tropical bay in southeastern Brazil (Azevedo et al., 2006), and fish communities in the litorals of three lagoons of the Orinoco River floodplain (Gabriela and Nirson, 2017).

Temperate coastal waters or bays are generally important spawning, feeding and nursery grounds for many fish and invertebrate species, which are crucial to the recruitment of fish resources and support many local fisheries (Wafar et al., 1983; Chen, 1991). Haizhou Bay, located in the western Yellow Sea, is an important spawning, nursery and feeding ground, and fishing ground for many commercially important fish species in the Yellow Sea (Chen, 1991). Previous studies focused on species diversity, taxonomic diversity and community structure of fish assemblages and their relationships with environmental variables in the Haizhou Bay (Su et al., 2013; Wang, 2013). The fish community in the bay is divided into the northern and southern assemblages characterized by different species composition in spring and autumn (Zhang et al., 2018). With fisheries management moving towards ecosystem-based method, it is more and more important to illuminate the spatial structure of fish community and species coexistence pattern (Roafuentes and Casatti, 2017; Ruppert et al., 2018). Ascertaining coexistence mechanism of fish species is a prerequisite for better understanding of fish community dynamics, and sustainable utilization and conservation of the fish resources in the coastal waters.

Detecting the spatio-temporal variations in co-occurrence patterns of fish communities is helpful to explore the community assembly mechanism, and provides some theoretical supports for fisheries management in the Haizhou Bay. In this study, null model analysis was applied to analyze the presence-absence matrices to examine the fish species co-occurrence patterns in spring and autumn over different years in the temperate bay. The goals of this study are to: 1) test whether fish species are assembled randomly in the Haizhou Bay; 2) explore the spatial and temporal variation of fish species co-occurrence patterns; 3) find significant species pairs structuring the fish assemblages.

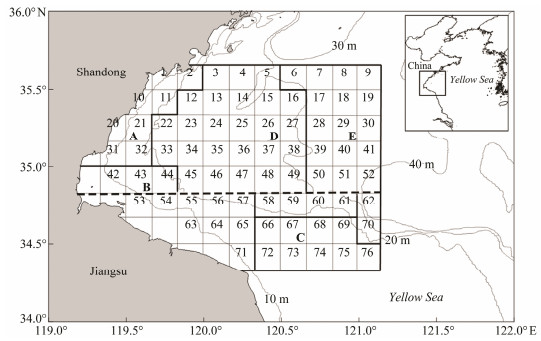

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Study AreaHaizhou Bay is located in the western Yellow Sea (Fig. 1). The depth increases from west to east in the bay. The hydrographic conditions are mainly influenced by the Yellow Sea Coastal Current along the southern Shandong Province and northern Jiangsu Province, the Yellow Sea Warm Current, and the Yellow Sea Cold Water Mass (Lin, 1989). The bay was divided into two parts at a 34°50'N boundary (Fig. 1), which primarily corresponded to waters of the northern and southern fish assemblages defined by Zhang et al. (2018).

|

Fig. 1 Bottom trawl survey area with stratified random sampling design in the Haizhou Bay. The bold dashed line divides the fish community of the bay into northern and southern assemblages (Zhang et al., 2018). Inserted map showing the survey area of Haizhou Bay in the Yellow Sea, China. |

The data were collected from the bottom trawl surveys of fish species conducted in May and October from 2013 to 2015 in the Haizhou Bay. The surveys followed a stratified random design in which the strata were defined mainly according to the oceanographic, geological, regional, and biological characteristics of the Haizhou Bay (Xu et al., 2015). The survey area was divided into 10'×10' sampling grid cells, and 18 sampling grids were randomly selected in each survey with 2, 4, 2, 7, and 3 sampling stations in stratum A, B, C, D, and E, respectively (Fig. 1). All the bottom trawl surveys were conducted using a 220 kW otter trawler during the daytime with the towing speed at about 2.5 knots and the trawling duration of about 1 hour on average. The open width of the sampling net was 25 m and the mesh size for the cod end was 17 mm. The fish samples were iced, brought back to the laboratory and identified as different species. The catches per haul in weight and number at each sampling station were recorded. The protocol for the stratified random survey design was described in details by Xu et al. (2015). The environmental factors including bottom water temperature, salinity and depth were measured simultaneously by CTD during the fish resources surveys.

2.3 Data Analysis 2.3.1 Co-occurrence patterns of fish assemblageFixed-fixed (FF) null model assumed that both the row and column sums of the original matrix were fixed, so that differences in the occurrence frequency of each species (row sums) and differences in the number of fish species per site (column sums) were preserved (Connor and Simberloff, 1979). The FF null model with low Type I error probability had a good power for detecting nonrandomness of species co-occurrence (Gotelli, 2002).

The C-score under FF null model algorithm was used to quantify the co-occurrence patterns of fish assemblage with presence-absence matrix data in the Haizhou Bay in spring and autumn from 2013 to 2015. According to its good power with algorithm described above, the C-score under FF null model had good power in dealing with noisy data (Gotelli, 2002).

The C-score quantified the average number of Checkerboard units that could be found for each species pair, which was calculated as follows (Stone and Roberts, 1990; Gotelli and Entsminge, 2001; Gotelli, 2002):

| ${C_{ij}} = ({R_i} - S)({R_j} - S), $ | (1) |

where Ri is the number of occurrences (row total) for species i, Rj is the number of occurrences for species j, and S is the number of sampling sites where both species occur. Let N = n (n-1)/2 be the number of species pairs for n species, then the C-score is:

| $C = \sum\nolimits_{i < j} {{C_{ij}}/N} .$ | (2) |

We used 30000 swaps per randomization and null distributions were generated from 10000 randomization of the focal matrix (Lehsten and Harmand, 2006; Lavender et al., 2016). The null hypothesis will be accepted when the observed value falls within the 95% confidence interval of distribution of 10000 times simulated values; the null hypothesis will be rejected when the observed value falls outside the 95% confidence interval.

2.3.2 Identification of significant species pairsThe whole matrix analysis only gave the pattern in average for co-occurrence of fish communities. Further analysis was performed to find out which particular pairs of species showed significantly positive versus negative associations. The Z-score was used to identify the significance of the C-score of each species pairs. Z-score below -2 or above 2 indicated significant aggregation or segregation (P < 0.05) (Ulrich, 2008; Gotelli and Ulrich, 2009; Echevarría and González, 2017).

The null models analyses were performed using the package EcosimR 0.1.0. (Gotelli et al., 2014). Pairwise species associations were calculated using PAIRS (Ulrich, 2008).

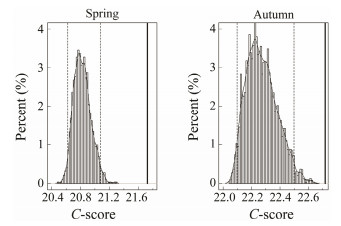

3 Results 3.1 Co-Occurrence Patterns of Fish Communities 3.1.1 Co-occurrence patterns of fish species for the whole fish assemblageThe observed C-score was significantly larger than the expected one by chance and the null hypothesis was rejected (P < 0.05), showing that fish species displayed negative co-occurrence patterns in spring and autumn from 2013 to 2015 in the whole bay (Fig. 2). The observed C-score based on the combined data of three years also showed that fish species displayed negative co-occurrence patterns both in spring and autumn, which confirmed the patterns for the whole fish assemblages in each year (Fig. 3).

|

Fig. 2 The C-score under fixed-fixed null model algorithm in spring and autumn for the whole fish assemblage. The dashed lines denote the lower and upper limits of 95% confidence interval of distribution of 10000 times simulated values; the solid line indicates the observed value. |

|

Fig. 3 The C-score under fixed-fixed null model algorithm based on the combined data from 2013 to 2015 for the whole fish assemblages in spring and autumn. The dashed lines denote the lower and upper limits of 95% confidence interval of distribution of 10000 times simulated values; the solid line indicates the observed value. |

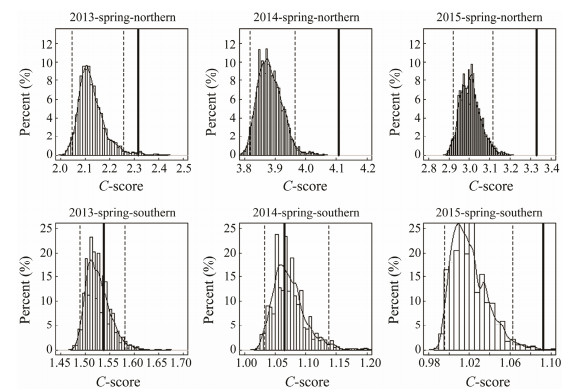

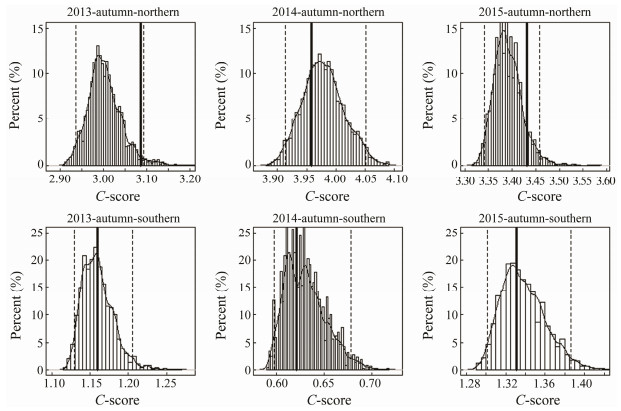

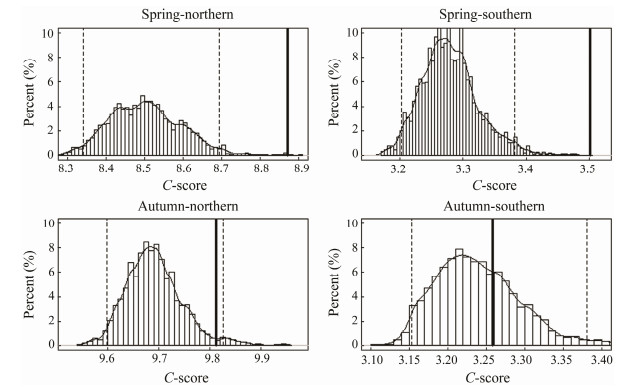

The observed C-score was significantly larger than the expected one by chance and the null hypothesis was rejected (P < 0.05), which indicated that fish species displayed negative co-occurrence patterns for the northern fish assemblages in spring from 2013 to 2015. The C-score showed that fish species were randomly distributed in 2013 and 2014, and showed negative co-occurrence pattern in 2015 for the southern assemblage in spring (Fig. 4). The observed C-score was not significantly different from the expected by chance, and the null hypothesis was accepted for the northern and southern fish assemblages in autumn over three years (Fig. 5).

|

Fig. 4 The C-score under fixed-fixed null model algorithm for the northern and southern fish assemblages in spring. The dashed lines denote the lower and upper limits of 95% confidence interval of distribution of 10000 times simulated values; the solid line indicates the observed value. |

|

Fig. 5 The C-score under fixed-fixed null model algorithm for the northern and southern fish assemblages in autumn. The dashed lines denote the lower and upper limits of 95% confidence interval of distribution of 10000 times simulated values; the solid line indicates the observed value. |

In spring, the observed C-score based on the combined data of three years was significantly larger than the expected one by chance and fish species exhibited negative co-occurrence patterns for the southern and northern fish assemblages, which confirmed the patterns in each year. In autumn, the C-score based on the combined data of all years showed that fish species in the southern and northern fish assemblages were randomly distributed (Fig. 6).

|

Fig. 6 The C-score under fixed-fixed null model algorithm based on the combined data from 2013 to 2015 in spring/autumn for the northern and southern fish assemblages. The dashed lines denote the lower and upper limits of 95% confidence interval of distribution of 10000 times simulated values; the solid line indicates the observed value. |

The numbers of fish species varied from 43 to 50 in spring and from 48 to 51 in autumn in the whole bay. In spring, 35-41 fish species in northern assemblages and 24-32 species in southern assemblages occurred from 2013 to 2015. In autumn, the numbers of fish species were 38-45 for northern assemblage and 30-40 for southern assemblage over three years. There were 30 warm temperate fish species, 12 cold temperate species, and 22 warm water species in 2013. In 2014, 27 warm temperate fish species, 9 cold temperate species, and 23 warm water species were caught. There were 22 warm temperate fish species, 10 cold temperate species, and 26 warm water species in 2015. There were more cold temperate species in the northern assemblage (Table 1).

|

|

Table 1 Numbers of fish species in spring and autumn over different years in the Haizhou Bay |

More significantly positive species pairs than negative ones were observed for the fish communities in the whole bay in both spring and autumn in different years (Table 2). Most of the segregated species pairs were composed of cold temperate species, such as Fang's blenny (Pholis fangi), Tanaka's snailfish (Liparis tanakai), fat greenling (Hexagrammos otakii) and Pacific sandlance (Ammodytes personatus), and other fish species (most species belong to warm water species or warm temperate species) for the fish communities in the whole bay. All these cold temperate species showed segregated patterns with red tongue sole (Cynoglossus joyneri) in spring over different years (Table 3). The numbers of segregated pairs of cold temperate species with other species were less in autumn than those in spring for fish communities in the whole bay.

|

|

Table 2 Numbers of significantly positive or negative species pairs for the whole assemblage in spring and autumn from 2013 to 2015 in the Haizhou Bay |

|

|

Table 3 Positive or negative species pairs for the whole assemblage in spring and autumn from 2013 to 2015 in the Haizhou Bay |

Many significantly positive species pairs were observed in the northern assemblage, which indicated a segregated pattern. However, few segregated species pairs were found in the southern assemblage (Table 4). Most segregated species pairs in the northern assemblage were formed by cold temperate species (including Fang's blenny, Tanaka's snailfish, fat greenling, Pacific sandlance) with other species. Six segregated species pairs were selected in the northern assemblage in spring of 2013, and all the pairs were formed by Pacific sandlance with others (Table 5).

|

|

Table 4 Number of significantly positive and negative species pairs for the northern and southern assemblages in spring and autumn from 2013 to 2015 in the Haizhou Bay |

|

|

Table 5 Positive and negative species pairs for the northern and southern assemblages in spring and autumn from 2013 to 2015in the Haizhou Bay |

This study showed that species co-occurrence patterns of fish assemblages were non-random and highly structured, and the fish species co-occurrence patterns kept relatively consistent and stable in different seasons and years in the whole Haizhou Bay. However, fish species co-occurrence patterns were different for the northern and southern assemblages in different seasons and years.

This study provided new evidence supporting the preponderance of non-random structure for fish communities that have been observed in different waters (Jackson, 1992; Echevarría and González, 2017). Species co-occurrence of fish assemblages were non-random and structured in the whole bay, which was similar with those of birds and mammals (Gotelli and Rohde, 2002; Pitta et al., 2012). However, it is hard to determine the extent to which the negative association is due to competitive species interactions or isolation of species (Gotelli and Rohde, 2002). Species co-occurrence patterns might vary with spatial scales (Mcnickle et al., 2017). Hoeinghaus et al. (2006) showed that fish community in temperate systems tends to show a nonrandom pattern at a regional scale, whereas it shifts to randomness at fine scale. The spatial and temporal variations of fish community structure should be incorporated into the analysis of fish species co-occurrence patterns.

Despite the tendency of negative co-occurrence patterns for the fish species, several random and aggregated species pairs were found for the fish assemblage in the Haizhou Bay. Therefore, non-random structure might result from non-random associations of only a subset of species (Krasnov et al., 2011). Cold temperate species (Fang's blenny, Tanaka's snailfish, fat greenling, Pacific sandlance) were most frequently segregated with several other species such as red tongue sole, filamentous shrimpgoby (Cryptocentrus filifer) in spring (Table 3). However, cold temperate species played less roles in significant species pairs, and most segregated species pairs were formed between cardinal fish (Apogonichthys lineatus), jewfish (Johnius belangeri) and other fish species in autumn in the bay. In the northern assemblage in different years, some cold temperate species were segregated with other species, whereas low number of pairs with significant co-occurrence patterns were found in the southern assemblage. These cold temperate species were strongly related to water temperature, which were identified as significant species pairs in the northern assemblage. It was proved that the environmental variability between the northern and southern parts of the bay was a factor resulting in the variation in the spatial distribution of cold temperate species like Fang's blenny and warm water species like red tongue sole in the bay (Wang, 2013). It showed that the water temperature and substrate were different in northern and southern areas of Haizhou Bay, and the northern assemblage was characterized by most cold temperate fish species. The distribution of Tanaka's snailfish, Fang's blenny, fat greenling, and anglerfish (Lophius litulon) shows negative correlations with temperature and positive correlations with depth in different seasons (Wang, 2013).

Environmental variables such as bottom water temperature and salinity show distinct spatial heterogeneity in spring and autumn in the Haizhou Bay (Wang, 2013; Su et al., 2013). The north-eastern waters is characterized by relatively low temperature and high salinity, and the southwestern waters has characteristics of high temperature and low salinity in the Haizhou Bay in spring. The salinity in autumn shows a similar pattern with that in spring in the bay. Bottom water temperature has no obvious pattern in autumn although it is still low in northeastern waters of the bay (Wang, 2013). The environmental heterogeneity on the bay scale has an effect on the spatial distribution of fish species with different ecological traits. For example, cold temperate species such as Pacific sandlance, Tanaka's snailfish, Fang's blenny and fat greenling widely distributed in the northern part of Haizhou Bay, whereas temperate or warm water species including red tongue sole and filamentous shrimpgoby, widely distributed in the southern part of the bay (Wang, 2013). In addition to the bay-scale heterogeneity, high and low spatial variations in environmental variables exist in the northern and southern parts of bay, respectively, which might result in negative co-occurrence of fish species in the northern waters and randomly distribution in the southern waters. The distributions of significant species pairs in the northern and southern assemblages were mainly related with the water temperature differences in the northern and southern waters of the bay. In terms of the distribution of species pairs and their habitat characteristics, environmental heterogeneity could play an important role in structuring the co-occurrence patterns for the northern and southern assemblages in the Haizhou Bay.

Gotelli and Ellison (2002) suggested that harsh environments (habitats) are the primary filtering factors for assembly rules. Azevedo et al. (2006) used unconstrained and constrained null models to examine the co-occurrence of fish communities in different seasons and three zones during summer in a tropical bay, and stated that habitat segregation could explain the pattern of reduced co-occurrence. Environmental filtering is by far the most important process structuring the fish communities (Azevedo et al., 2006). The importance of environmental filtering in driving the fish community structure is also proved by co-occurrence of fish species in tropical streams (Peres-Neto, 2004). In the Haizhou Bay, environmental heterogeneity might be a factor affecting the co-occurrence patterns of northern and southern fish assemblages. The differentiation of co-occurrence patterns between the northern and southern assemblages can lead to different implementation schemes for the conservation and management of fish resources in the northern and southern parts of the bay.

In summary, fish communities in the whole bay showed non-random species segregation patterns in the spring and autumn over different years. However, the northern and southern assemblages showed different patterns compared with the fish community in the whole bay. Positive species pairs were not always more than negative ones in significantly co-occurring species pairs. Environmental conditions had an effects on the co-occurrence patterns of fish communities in the bay. The deep understanding of co-occurrence patterns of fish communities would be helpful in the ecosystem-based management in the Haizhou Bay. Further study will be needed to explore to what extent the environmental variables or biotic interaction plays a role in affecting the co-occurrence patterns of fish species in the Haizhou Bay. These results expose the need to further explore the co-occurrence patterns in temperate coastal waters or bays.

AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to all scientific staff and crew for their assistance in data collection during the surveys. This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31772852), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. 2015 62030, 201612004), and the Public Science and Technology Research Funds Projects of Ocean (No. 201305030).

Azevedo, M. C. C. D., Araújo, F. G., Pessanha, A. L. M. and Silva, M. D. A., 2006. Co-occurrence of demersal fishes in a tropical bay in southeastern Brazil: A null model analysis. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 66(1): 315-322. (  0) 0) |

Beaudrot, L., Struebig, M. J., Meijaard, E., Van, B. S., Husson, S. and Marshall, A. J., 2013. Co-occurrence patterns of Bornean vertebrates suggest competitive exclusion is strongest among distantly related species. Oecologia, 173(3): 1053-1062. DOI:10.1007/s00442-013-2679-7 (  0) 0) |

Chen, D. G., 1991. Fishery Ecology in the Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea. China Ocean Press, Beijing, 8-20.

(  0) 0) |

Connor, E. F. and Simberloff, D., 1979. The assembly of species communities: Chance or competition?. Ecology, 60(6): 1132-1140. DOI:10.2307/1936961 (  0) 0) |

Diamond, J. M., 1975. Assembly of species communities. In: Ecology and Evolution of Communities. Cody, M. L., and Diamond, J. M., eds., Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 342-444.

(  0) 0) |

Echevarría, G. E. and González, N., 2017. Co-occurrence patterns of fish communities in littorals of three floodplain lakes of the Orinoco River, Venezuela. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 9(6): 10249-10260. DOI:10.11609/jott.2710.9.6.10249-10260 (  0) 0) |

Englund, G., Johansson, F., Olofsson, P., Salonsaari, J. and Öhman, J., 2009. Predation leads to assembly rules in fragmented fish communities. Ecology Letters, 12(7): 663-671. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01322.x (  0) 0) |

Gabriela, E. E. and Nirson, G., 2017. Co-occurrence patterns of fish communities in littorals of three floodplain lakes of the Orinoco River, Venezuela. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 9(6): 10249-10260. DOI:10.11609/jott.2710.9.6.10249-10260 (  0) 0) |

Giam, X. and Olden, J. D., 2016. Environment and predation govern fish community assembly in temperate streams. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 25(10): 1194-1205. DOI:10.1111/geb.12475 (  0) 0) |

Gotelli, N. J., 2000. Null model analysis of species co-occurrence patterns. Ecology, 81(9): 2606-2621. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[2606:NMAOSC]2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Gotelli, N. J. and Ellison, A. M., 2002. Biogeography at a regional scale: Determinants of ant species density in New England bogs and forests. Ecology, 83(6): 1604-1609. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[1604:BAARSD]2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Gotelli, N. J., and Entsminge, G. L., 2001. EcoSim: Null models software for ecology. Version 6.10. Acquired Intelligence Inc. and Kesey-Bear.

(  0) 0) |

Gotelli, N. J. and Rohde, K., 2002. Co-occurrence of ectoparasites of marine fishes: A null model analysis. Ecology Letters, 5(1): 86-94. DOI:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00288.x (  0) 0) |

Gotelli, N. J. and Ulrich, W., 2009. The empirical Bayes approach as a tool to identify non-random species associations. Oecologia, 162(2): 463-477. (  0) 0) |

Gotelli, N. J., Hart, E. M., and Ellison, A. M., 2014. EcoSimR 0.1.0. http://ecosimr.org.

(  0) 0) |

Grubb, P. J., 2010. The maintenance of species-richness in plant communities: The importance of the regeneration niche. Biological Reviews, 52(1): 107-145. (  0) 0) |

Hoeinghaus, D. J., Winemiller, K. O. and Birnbaum, J. S., 2006. Local and regional determinants of stream fish assemblage structure: Inferences based on taxonomic vs. functional groups. Journal of Biogeography, 34(2): 324-338. (  0) 0) |

Jackson, D. A., Somers, K. M. and Harvey, H. H., 1992. Null models and fish communities: Evidence of nonrandom patterns. American Naturalist, 139(5): 930-951. DOI:10.1086/285367 (  0) 0) |

Krasnov, B. R., Shenbrot, G. I. and Khokhlova, I. S., 2011. Aggregative structure is the rule in communities of fleas: Null model analysis. Ecography, 34(5): 751-761. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06597.x (  0) 0) |

Lavender, T. M., Schamp, B. S. and Lamb, E. G., 2016. The influence of matrix size on statistical properties of co-occurrence and limiting similarity null models. PLoS One, 11(3): e0151146. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0151146 (  0) 0) |

Lehsten, V. and Harmand, P., 2006. Null models for species co-occurrence patterns: Assessing bias and minimum iteration number for the sequential swap. Ecography, 29(5): 786-792. DOI:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2006.04626.x (  0) 0) |

Lin, M. H., 1989. The submarine geomorphological zones and geomorpnological types in the Yellow Sea. Marine Science of China, 13: 7-15. (  0) 0) |

Mcnickle, G. G., Lamb, E. G., Lavender, M., Cahill, J. F., Schamp, B. S., Siciliano, S. D., Condit, R., Hubbell, S. P. and Baltzer, J. L., 2017. Checkerboard score-area relationships reveal spatial scales of plant community structure. Oikos, 127: 415-426. (  0) 0) |

Morin, P. J., 2011. Community Ecology. Wiley-Blackwell, New Jersey, 3-23.

(  0) 0) |

Peres-Neto, P. R., 2004. Patterns in the co-occurrence of fish species in streams: The role of site suitability, morphology and phylogeny versus species interactions. Oecologia, 140(2): 352-360. DOI:10.1007/s00442-004-1578-3 (  0) 0) |

Pitta, E., Giokas, S. and Sfenthourakis, S., 2012. Significant pairwise co-occurrence patterns are not the rule in the majority of biotic communities. Diversity, 4(2): 179-193. DOI:10.3390/d4020179 (  0) 0) |

Roafuentes, C. A. and Casatti, L., 2017. Influence of environmental features at multiple scales and spatial structure on stream fish communities in a tropical agricultural region. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 32(1): 273-287. (  0) 0) |

Rooney, T. P., 2008. Comparison of co-occurrence structure of temperate forest herb-layer communities in 1949 and 2000. Acta Oecologica, 34(3): 354-360. DOI:10.1016/j.actao.2008.06.011 (  0) 0) |

Ruppert, J., Vigliola, L., Kulbicki, M., Labrosse, P., Fortin, M. J. and Meekan, M. G., 2018. Human activities as a driver of spatial variation in the trophic structure of fish communities on Pacific coral reefs. Global Change Biology, 24(1): e67. DOI:10.1111/gcb.13882 (  0) 0) |

Soliveres, S., Maestre, F. T., Bowker, M. A., Torices, R., Quero, J. L., García-Gómez, M. and Noumi, Z., 2014. Functional traits determine plant co-occurrence more than environment or evolutionary relatedness in global drylands. Perspectives in Plant Ecology Evolution and Systematics, 16(4): 164-173. DOI:10.1016/j.ppees.2014.05.001 (  0) 0) |

Stone, L. and Roberts, A., 1990. The checkerboard score and species distributions. Oecologia, 85(1): 74-79. DOI:10.1007/BF00317345 (  0) 0) |

Su, W., Xue, Y. and Ren, Y. P., 2013. Temporal and spatial variation in taxonomic diversity of fish in Haizhou Bay: The effect of environmental factors. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 20(3): 624-634. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1118.2013.00624 (  0) 0) |

Tilman, G. D., 1984. Plant dominance along an experimental nutrient gradient. Ecology, 65(5): 1445-1453. DOI:10.2307/1939125 (  0) 0) |

Ulrich, W., 2008. Pairs-a FORTRAN program for studying pairwise species associations in ecological matrices (Version 1.0) Available at: www.uni.torun.pl/~ulrichw.

(  0) 0) |

Wafar, M. V. M., Corre, P. L. and Birrien, J. L., 1983. Nutrients and primary production in permanently well-mixed temperate coastal waters. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 17(4): 431-446. DOI:10.1016/0272-7714(83)90128-2 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X. L., 2013. Temporal and spatial variations of the fish community structure in Haizhou Bay and its adjacent waters. Master thesis. The Ocean University of China.

(  0) 0) |

Xu, B. D., Ren, Y. P., Chen, Y., Xue, Y., Zhang, C. L. and Wan, R., 2015. Optimization of stratification scheme for a fisheryindependent survey with multiple objectives. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 34(12): 154-169. DOI:10.1007/s13131-015-0739-z (  0) 0) |

Yant, P. R., Karr, J. R. and Angermeier, P. L., 1984. Stochasticity in stream fish communities: An alternative interpretation. American Naturalist, 124(4): 573-582. DOI:10.1086/284296 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, R., Xue, Y., Zhang, C. L., Ren, Y. P. and Xu, B. D., 2018. Structural redundancy of fish assemblage in Haizhou Bay and its adjacent waters. Journal of Fisheries of China, 42(7): 1040-1049. (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18