2) College of Marine Life Science, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China

Plastics with a particle size less than 5 mm are classified as microplastics (Law and Thompson, 2014; Lang et al., 2020). Microplastics are widely distributed in both marine and freshwater environments (Eerkes-Medrano et al., 2015; Jabeen et al., 2017). Research into micro-plastics has increased rapidly due to greater awareness of the potential risks and biological effects. Microplastics are difficult to degrade (Sait et al., 2020) and exist in environments for a long time (Cózar et al., 2014). Micro-plastics have been identified as a serious global pollutant problem and are considered a serious threat to the environment by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP, 2014), the European Commission's SCHEER committee (SCHEER – Scientific Committee on Health Environmental and Emerging Risks, 2018). To control the increase in microplastic pollution, comprehensive monitoring of microplastic pollution must be undertaken.

Despite significant research into microplastics in the marine environment, information on the quantity, sources, and impacts of microplastics in rivers is still limited (Blettler et al., 2018; Koelmans et al., 2019). As a crucial carrier in freshwater ecosystems, rivers connect land to the sea and are the main source of marine microplastic pollution (Lebreton and Andrady, 2019). Recently, scientific concern for microplastics in rivers has rapidly increased, with some studies showing that microplastics in rivers are widespread and are not only concentrating microplastic pollution from land but are also an important source of microplastic pollution entering the sea (Lebreton et al., 2017).

However, research on microplastics in rivers is mainly concentrated on river mouth areas (Zhao et al., 2015; Wessel et al., 2016). Although recent studies on microplastics in the whole river reach have been carried out (Qi et al., 2019; Gong et al., 2020; Tien et al., 2020), there are still many rivers for which there is no information on microplastic pollution, and there are relatively few comparative and correlation analyses conducted between microplastics in surface waters and floodplain sediments. There is a clear need for more investigation into the quantities, distribution, and source of microplastic pollution in rivers in different regions.

The Dagu River is the largest in the Jiaodong peninsula, which is one of the most rapidly developing regional economic centers of East China. The Dagu River is an important drinking water source and is called the mother River of Qingdao. It is also responsible for the largest input of freshwater, sediment, and pollutants to Jiaozhou Bay (Wang et al., 2014).

In the present study, 14 survey stations from the headwater to the estuary area along the Dagu River were selected. The abundance, morphology, and polymer composition characteristics of microplastics in the surface waters and floodplain sediments were investigated, revealing the characteristics and distribution of microplastic pollution in the basin, and we have analyzed the sources of the microplastics. This study provides a theoretical basis and data support for understanding the transport characteristics and sources of microplastics in rivers.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Research Area and Station LayoutThe Dagu River is the largest in the Jiaodong Peninsula, which is the regional economic center of East China. It originates from the Fushan mountain of Zhaoyuan County, Yantai, flows through the western part of the Jiaodong Peninsula, and finally flows into Jiaozhou Bay at Matou Village. The Dagu River is approximately 180 km long, with a basin area of 4900 km2 and an average annual rainfall of 644.7 mm. Dagu River Basin is located in the warm temperate zone of North China and the coastal humid monsoon climate zone. It is hot and rainy in summer, cold and dry in winter, and moderate in spring and autumn with little rain (Wang et al., 2014). Through field investigation, it is found that there are no large towns and cities in the upper reaches of Dagu River and the population density is small, while there are large towns and cities, industry, and aquaculture in the lower reaches of Dagu River, with dense population and complex human activities. The terrain of the basin is high in the north and low in the south, and the terrain slope gradually becomes slow from north to south. The upper reaches of the Dagu River flow through the countryside, and the lower reaches of the river flow through large towns and cities. There are many tributaries to the Dagu River, and several reservoirs and dams have been constructed along the trunk stream. Therefore, the Dagu River has several cutoffs, especially in the upper reaches of the river.

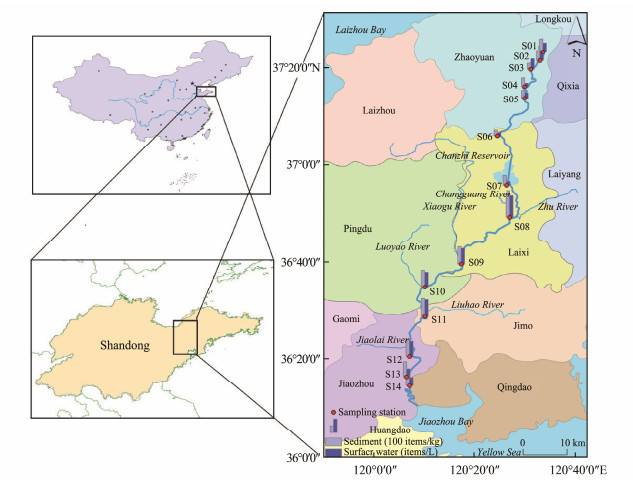

A field survey of microplastics in the surface waters and floodplain sediments of the Dagu River was carried out between August 8 and August 12, 2019. 14 survey stations were selected in the mainstream of the Dagu River. The detailed location and sampling sites are shown in Fig.1 and Table 1.

|

Fig. 1 Geographic locations and sampling station in Dagu River. |

|

|

Table 1 Sampling station of the Dagu River |

Three parallel samples were collected at one sampling station. At each sampling point, 50 L of surface water (water depths were typically less than 50 cm) by used in a pre-cleaned stainless steel bucket and filtered through a plankton net (64 μm mesh size). All the microplastics remaining in the bottom collector after filtering were transferred to a glass sampling bottle, which was labeled and stored away from light.

For floodplain sediment sampling, three parallel samples were collected at one sampling station, each with a sampling area of 15 cm × 15 cm and a thickness of 5 cm on the banks of the river. Floodplain sediments were collected into glass bottles by a steel hand shovel. The samplings are away from light and air-dried to a constant weight at the laboratory.

At each station, water samples were collected for water quality analysis, according to the Technical Specifications Requirements for Monitoring of Surface Water Waste Water (HJ/T 91-2002).

2.3 Sample PreparationMicroplastics in the surface waters were separated using the previously reported method, with a little adjustment (Ding et al., 2019). Firstly, the water sample was passed through a 0.45 μm glass filter membrane by a diaphragm vacuum pump. The filter paper was then rinsed with 30% hydrogen peroxide (Wang et al., 2018; Rose and Webber, 2019). The rinse solution was collected in a conical flask with 0.1 g FeCl2 added (Wen et al., 2018; Aliabad et al., 2019). Finally, the conical flask was incubated in a water bath at 60℃ for 24 h to remove organic matter and other substances that may affect the subsequent microscopic observation.

The digested sample was filtered using a series of stainless steel sieve apertures: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.1 and 0.01 mm turn, and the different particle sizes of debris trapped in each sieve were flushed carefully into five Petri dishes by a syringe filled with ultra-pure water. The samples were dried at 60℃ for the following analysis.

The microplastics were isolated from floodplain sediment samples by the previous method with modifications (Stock et al., 2019; Kor and Mehdinia, 2020). Firstly, the dried floodplain sediment samples were evenly spread on an enamel plate, then put in a beaker using a spoon (300 g), and 1 L high-density (1.5 g mL−1) ZnCl2 was added, stirred with a clean glass rod for 5 min, and left to stand for 5 h. Finally, the upper liquid was transferred into another beaker and left to stand for 5 h; this step was repeated twice. The upper liquid layer was collected and used for microplastic separation by the method described above.

2.4 Characterization of MicroplasticsThe abundance, color, particle size, and shape characteristics of microplastics were examined under the microscope (JNOEC XS-212-202). The microplastic abundance in surface waters was expressed as items L−1 (number of microplastics in the surface water per liter), and that in the sediments of the floodplain was expressed as items kg−1 (number of microplastics in the floodplain sediments per kg).

Microparticles (200 items) were randomly selected for infrared microspectrometer analysis (Nicolet iN10 IR Microscope, Thermo Fisher, America), including 100 from the floodplain sediments and 100 from the surface waters. The scanning spectrum range was 400 – 4000 cm−1, and the obtained spectrum was compared with the standard spectrum (OMNIC 8.2) to determine the polymer type of the microplastics. All the 200 particles were identified as microplastics.

To avoid potential artificial and airborne plastic contamination in the laboratory, all instruments and containers were carefully rinsed with ultra-pure water and tightly wrapped in tin foil and the laboratory was kept clean at all times. Lab coats, mask covers, and gloves were worn throughout the sample collection and laboratory analysis. Blanks were conducted in parallel as a control during all phases of the analytical procedure and no microplastics were found in the blank group.

2.5 Water Quality DeterminationTemperature (T), pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and dissolved oxygen (DO) were measured in situ using a portable multi-parameter water quality tester (HACH HQ40d). After collection, the water samples were kept on ice and transferred to the laboratory within 24 h. To analyze other parameters, such as five-day biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5), permanganate index (CODMn), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), ammonia nitrogen (NH4-N), nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N), nitrite (NO2-N), orthophosphate (MPO4), and suspended substances (SS), water samples were transferred to the laboratory and were analyzed using the methods described in the Technical Specifications Requirements for Monitoring of Surface Water Waste Water (HJ/T 91-2002).

2.6 Data AnalysisData and descriptions were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and SPSS vs. 22 (IBM). One-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was used to classify and test the regional significance of microplastic indicators at different stations (P < 0.05, least significant difference). The Pearson coefficient was applied to study and interpret the relationships and interactions among the microplastics and water quality indicators. A correlation coefficient close to 1 or −1 indicates the strongest positive or negative correlation between two variables, while a value close to 0 indicates that there is no linear relationship between them at a statistically significant level with P < 0.05 and/or P < 0.01.

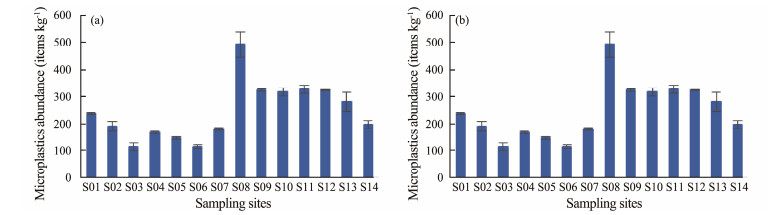

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 Abundance of MicroplasticsThe abundance of microplastics in surface waters and floodplain sediments is presented in Fig.2. The abundance of microplastics in surface waters varied from 0.68 items L−1 to 3.96 items L−1, with an average abundance of 1.95 items L−1. The surface waters of the Dagu River have moderate microplastic pollution compared to many other rivers. The abundance of microplastics in the surface waters of the Dagu River was lower than in the Pearl River (0.379 – 7.924 items L−1) (Lin et al., 2018). One reason is that microplastic pollution is worse in economically developed or densely populated areas (Xiong et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). The Pearl River flows through large cities such as Guangzhou, while the Dagu River flows through mainly rural areas. The second reason is that the Pearl River microplastics were collected by a sieve with an aperture of 20 μm, while this study used a sieve of 64 μm, which resulted in different particle sizes of micro-plastics were collected in the two studies. These two reasons resulted in higher data on the abundance of microplastics in the Pearl River than in this study. The abundance of microplastics in the surface waters of the Dagu River was higher than in the Han River ((0 – 4.29) × 10−2 items L−1) (Park et al., 2010). One reason is that Han River microplastics were collected with a 100 μm sieve, which resulted in no microplastic samples with a particle size of fewer than 100 μm being collected. In a word, the differences are not only due to the population density and the level of economic development in the areas where these rivers flow but are also closely related to the sampling and separation methods. At present, different microplastics sampling tools are used in different studies, which makes it difficult to compare and analyze microplastics in different study areas.

|

Fig. 2 Abundance distribution of microplastics collected from the Dagu River: (a) from surface waters and (b) from floodplain sediment. |

Fig.2a shows that there are significant regional differences in the abundance of microplastics in the Dagu River surface waters at each station because of the various characteristics of sampling sites and the surrounding human activities (Zhao et al., 2020). The abundance of microplastics at station S08 is the highest, which could be because the station is located at the confluence of the Dagu River, Changguang River, and Zhu River. The Zhu River passes through the urban and industrial areas of Laixi: the main industries in Laixi include food processing, textile manufacturing, rubber materials, etc., all of which could be a source of microplastics (Park et al., 2004; Geyer et al., 2017). Some investigation of micro-plastics shows that the inflow of tributaries is an important supplement of microplastics to the mainstream (Park et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). A second possible reason for the highest abundance is that the sampling station is closed to a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP). Many studies have identified WWTPs as an important source of microplastic pollution (Conley et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019; Sol et al., 2020), but there have been conflicting reports about the contribution of WWTPs to microplastics in rivers (Tien et al., 2020). Experiments have shown that 98% of microplastics can be removed by tertiary treatment technology, indicating that WWTPs have little effect on the abundance of microplastics in rivers (Murphy et al., 2016); however, many WWTPs do not meet these standards and do not monitor effluent microplastics. This study suggests that WWTP is a potential source of microplastics in rivers. The potential impact of microplastic discharge from WWTPs on the pollution of urban rivers deserves further attention.

The abundance of microplastics from S08 to S12 is significantly higher than in the other regions (P < 0.01). The river in this section flows through Laixi, Jimo, Pingdu, and Jiaozhou, which are densely populated and economically developed regions. Previous studies have shown that microplastic abundance is high in economically developed regions (Xiong et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). Meanwhile, these five sites also have tributary confluence. The abundance of microplastics near the estuary, at stations S13 and S14, was significantly reduced, which may be related to the non-tributary inflow and tidal dilution (Zhao et al., 2020). A study found that the abundance of microplastics in the surface waters of the Dagu River Estuary was 80 items m−3 (Zheng et al., 2019), which was lower than the river in this study. This could be because their sampling site was located in the river mouth downstream of S14, which is more affected by the seawater exchange. The results indicate that water exchange might have a great influence on the abundance of microplastics in estuaries.

At sites S08 – S12, which had high abundances of microplastics, NH4-N and CODMn were also high (Tables 2 and 3). The correlation analysis shows the abundance of microplastics in surface waters was significantly positively correlated with CODMn (R = 0.677**, P < 0.01) and NH4-N (R = 0.551*, P < 0.01), indicating that water contamination is usually accompanied by microplastic pollution, to a certain extent. One possible reason is that the sources and inflow processes of microplastics are similar to organic pollutants (Kataoka et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). For example, factories, WWTPs, and other point sources of pollution release microplastics directly into the river. However, the correlation between microplastic abundance and water quality parameters is not necessarily linear; for instance, the TN and TP of S01 and S02 are relatively high because the river has been polluted by rural non-point sources, but the abundance of microplastics is relatively low, which could be because microplastics from agricultural activities do not go directly into rivers as easily as other pollutants (Liu et al., 2018). More researches are needed to understand the transformation and migration differences between microplastics and other pollutants.

|

|

Table 2 Values of the water quality index |

|

|

Table 3 Pearson correlation between microplastics and water quality index |

The abundance of microplastics in floodplain sediments of Dagu River ranges from 115.5 items kg−1 to 495 items kg−1, with an average abundance of 252.7 items kg−1 (Fig.2b). The Dagu River has a lower abundance of floodplain sediment microplastics than the Yellow River ((15 – 615) items kg−1) (Gong et al., 2020), but higher than the Moshui River ((0 – 170) items kg−1) (Qi et al. 2019) and Daliao River ((66.67 ± 79.93) items kg−1) (Han et al., 2020). This demonstrates that a higher population density in the river basin increases the abundance of microplastics (Tsering et al., 2021). There is a moderate abundance of microplastics in floodplain sediments of the Dagu River. The correlation analysis shows that the abundance of microplastics in the floodplain sediments of the Dagu River is significantly correlated with the abundance in the surface waters (R = 0.873**, P < 0.01), indicating that the two have a great consistency, and may have the same pollution source.

The decline in microplastic abundance in S13 and S14 could be due to seawater exchange; however, the EC (electric conductivity) of S13 and S14 was significantly higher, and the decline in microplastic abundance in the floodplain sediments was significantly slower than in the surface water. This could be a result of a combination of several factors: the coagulates and sedimentation of microplastics due to a mixture of salt and fresh water (Long et al., 2015; Cole et al., 2016), and the increasing seawater exchange closer to the estuary. In S13, the influence of deposition, due to enrichment or polymerization, is greater than that of S14. In other words, the abundance of microplastics in surface water will decrease due to seawater exchange, and some microplastics will deposit on the floodplain sediments. This hypothesis needs to be tested by rigorous experiments.

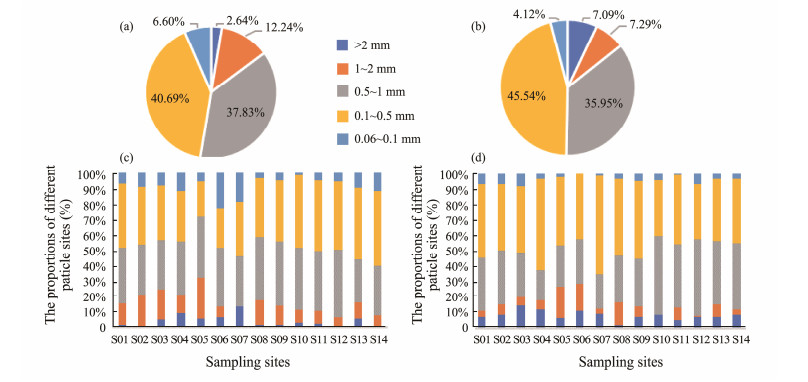

3.2 Microplastic Size CharacteristicsMicroplastics in the surface waters could be classified into five categories: 0.06 – 0.1 mm, 0.1 – 0.5 mm, 0.5 – 1 mm, 1 – 2 mm, and > 2 mm. In this study, the most abundant group in surface waters of the Dagu River was 0.1 – 0.5 mm (41%) and 0.5 – 1 mm (38%) (Fig.3a). This is consistent with the results from Wei River (< 0.5 mm, 68.1%) (Ding et al., 2019), Haihe River (0.1 – 1 mm, 54.1%) (Liu et al., 2020), Yulin River (0.064 – 0.25 mm, > 80%) (Mao et al., 2020), Fengshan River (0.05 – 0.297 mm, > 60%) (Tien et al., 2020), and Han River (0.1 – 1 mm, > 90%) (Park et al., 2020). In a word, microplastics with a particle size of 0.1 – 1 mm accounted for the largest proportion in most rivers.

|

Fig. 3 Particle size characteristics of microplastics in Dagu River and floodplain sediment: (a), the proportion of different particle size microplastics in surface waters; (b), the proportion of different particle size microplastics in floodplain sediments; (c), the distribution of particle sizes of microplastics in surface waters; (d), the distribution of particle sizes of microplastics in floodplain sediments. |

The proportion of each type of microplastic in the floodplain sediments was similar to the surface waters, with 0.1 – 0.5 mm (46%) and 0.5 – 1 mm (36%) accounting for the majority (Fig.3b). However, the proportion of microplastics (0.06 – 0.1 mm) in the floodplain was less than that in the surface waters, which may be because this size of microplastics is easily washed away by the river, while microplastics with a larger particle size (> 2 mm) deposit in the floodplain (Liu et al., 2018).

The particle size distribution has obvious spatial characteristics (Figs.3c and d). The proportion of microplastics with a particle size of 0.06 – 0.5 mm in the surface waters in the lower reaches of the Dagu River (S08 – S14) was significantly higher than in the upper reaches (S01 – S07) (P < 0.05). Correspondingly, the proportion of microplastics with a particle size of 0.06 – 0.5 mm in the floodplain sediments of the lower reaches of Dagu River (S08 – S14) was significantly higher than in the upper reaches (P < 0.05), indicating that microplastics with a particle size of 0.06 – 0.5 mm were easily transported to the lower reaches of the river and can enter the ocean. Therefore, it can be speculated that the proportion of small microplastics in the ocean is higher than that of larger microplastics. Many references to Marine micro-plastics confirm this conclusion (Zhou et al., 2018; Kanhai et al., 2020; Patti et al., 2020).

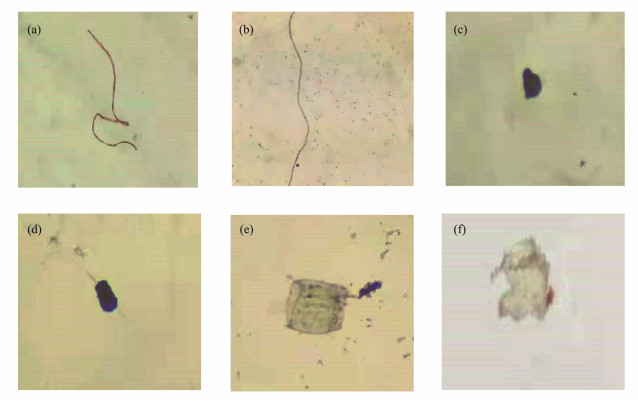

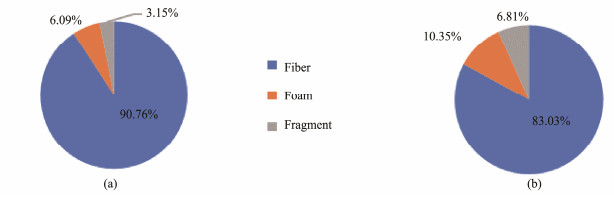

3.3 Shape Characteristics of MicroplasticsThe microplastics in surface waters and floodplain sediments were divided into three types: fiber (90.76%), foam (6.09%), and fragment (3.15%) (Figs.4 and 5). The fiber was the most common shape, which is similar to those found in Haihe River (fiber, 86.7%) (Liu et al., 2020) and Pearl River (fiber, 80.9%) (Lin et al., 2018). The source of fiber microplastics in rivers might be related to the surrounding textile industry, fabric washing, and fisheries (Alam et al., 2019). The present study shows similarities with previous studies, which have shown that fiber was the dominant microplastic (77.14%), in the seawater of Jiaozhou Bay, where the Dagu River flows (Zheng et al., 2019). It has been suggested that rivers as transportation vector of microplastics into the ocean is an important source of marine microplastic pollution (Zheng et al., 2019).

|

Fig. 4 Images of different microplastics were obtained directly by microscope. (a, b), fiber; (c, d), foam; (e, f), fragment. |

|

Fig. 5 Shape characteristics of microplastics in Dagu River and floodplain sediment: (a), the proportion of different shapes of microplastics in surface waters; (b), the proportion of different shapes of microplastics in floodplain sediments. |

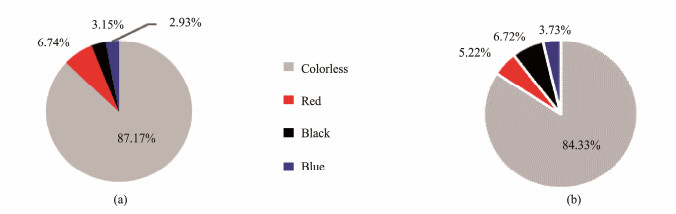

The colors of microplastics in the Dagu River surface waters and floodplain sediments can be observed through the microscope. These included colorless (87.17%), red (6.74%), black (3.15%), and blue (2.93%) microplastics (Figs.6a and b). There are several reasons for this result. First, there are many farmlands in villages near the Dagu River and industries such as vegetable greenhouses and fruit trees, which use a large amount of colorless transparent plastic: the big plastics produced by these industries are broken down into microplastics and enter the rivers (Blcasing and Amelung, 2018). Second, colored microplastics will fade under the actions of sunlight, heat, and hydrodynamics or weathering, forming colorless microplastics (Zhou et al., 2020). In addition, fish in rivers and other aquatic organisms prefer to ingest colored microplastics (Zhao et al., 2015a), which is also a potential factor for the high proportion of colorless microplastics. Different rivers show different color proportions due to microplastic sources and environmental influences. However, in a comparison of multiple rivers, light-colored microplastics accounted for the highest proportion in most studies such as Pearl River (white, 65.6%) (Lin et al., 2018) and Tuojiang River (white, 23.30% – 54.29%) (Zhou et al., 2020). Therefore, it is speculated that microplastic color will become shallower after long-term exposure to the environment.

|

Fig. 6 Color characteristics of microplastics in Dagu River and floodplain sediment: (a), the proportion of different colors of microplastics in surface waters; (b), the proportion of different colors of microplastics in floodplain sediments. |

Due to experimental limitations, it was difficult to distinguish colorless and white microplastics using an optical microscope, so white and colorless were classified as colorless. This could be one of the reasons for the differences between the results of this study and other studies. The effects of climate and hydrology on the color of microplastic require further study and discussion.

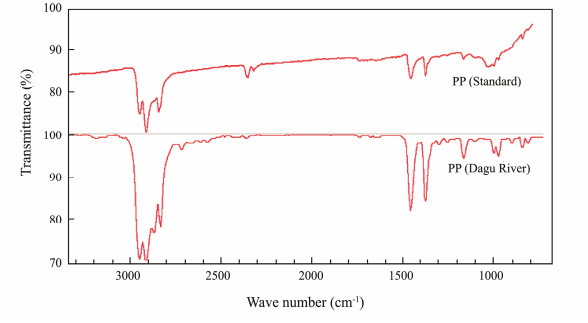

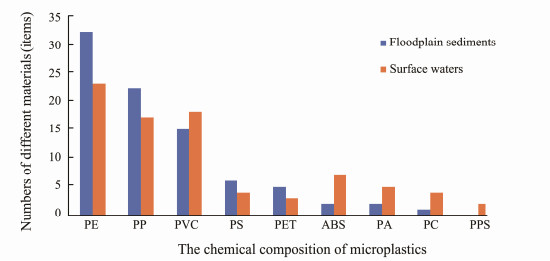

3.5 Chemical Composition and Source Analysis of MicroplasticsIdentifying microplastics solely by particle size, color, and shape may lead to other tiny particles, such as algae or salts, being mistaken for microplastics (Alam et al., 2019). In this study, 200 microparticles were randomly selected for the infrared microspectrometer detection, and the scanning spectra were compared with the standard spectra to determine the polymer types (Fig.7). In the surface water samples, 83% were identified as microplastics, and in the floodplain sediment samples, 85% were identified as microplastics. The polymer types of microplastics in the surface waters are mainly PP (23%), PE (17%), and PVC (18%). In the floodplain sediments, PP (32%), PE (22%), and PVC (15%) dominated (Fig.8). The polymer types of microplastics in surface waters were significantly correlated with that in floodplain sediments (R = 0.942**, P < 0.01), indicating that the two may have the same pollution source.

|

Fig. 7 The infrared spectra of microplastics from Dagu River, compared with standard plastics using polypropylene (PP) as an example. |

|

Fig. 8 Polymer type of microplastics in surface waters and floodplain sediments of Dagu River. PE, polyethylene; PP, polypropylene; PVC, polyvinyl chloride; PS, polystyrene; PET, polyethylene terephthalate; ABS, acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene copolymer; PA, polyamide; PC, polycarbonate; and PPS, polyether plastics. |

PP and PE were the major polymer types of microplastic particles in surface waters and floodplain sediments of the Dagu River. The main land-use type in Dagu River Basin is cultivated land (89%) (Wang et al., 2014). A previous study showed that the main polymer types of microplastics were PP and PE in the suburbs of Shanghai (Liu et al., 2018). It indicates that agricultural non-point source pollution may bring a large number of PP and PE microplastics. PP and PE are common lightweight plastics and are easily processed as colored materials due to their relatively low density, which is likely caused by the widespread use of packing material and plastic bottles. And they are most likely to be found in surface waters and floodplain sediments (Engler, 2012; Zhou et al., 2020). PS, PVC, and PPS are mainly used in industrial production and building materials. There are frequent human activities around the Dagu River, and building activities such as house repair and renovation may be the main sources of these microplastics. Lack of effective waste management and the discarding of household garbage such as clothing, plastic cups, and plastic bags might cause a large number of colored microplastic pollution, and the PET, PA, ABS, and PC detected in this study may come from these sources.

Consistent with the above argument, human activities that produce plastic waste such as farming, textile, and industrial activities, may eventually cause microplastic pollution in the Dagu River and persist in the environment. Rivers are critical to agriculture, industry, and the needs of humans and wildlife. Despite intensive research efforts, larger studies with improved experimental designs are still required, and many complex factors need to be considered in tracing microplastics from rivers.

4 Conclusions1) The present study found that microplastics are widely distributed in the surface waters and floodplain sediments of the Dagu River. Compared with investigations of microplastics from rivers in China and other countries, these results show that there is moderate microplastic pollution in the Dagu River. Both in surface waters and floodplain sediments of the Dagu River, the main particle size of microplastics was 0.1 – 1 mm, with colorless microplastics accounting for about 85%. Fiber microplastics account for approximately 90% of the total count, and the main chemical composition of microplastics is PP, PE, and PVC.

2) According to the particle size, color, shape, and polymer types, the main sources of microplastics in Dagu River might be related to the emissions from the planting industry, textile industry, and household garbage. These results support the argument that human activities are the most important cause of microplastic pollution.

3) This study shows that microplastics exist in large quantities in freshwater systems such as rivers and reservoirs, which is of significant concern. In the future, tracing the sources of microplastic solution in the Dagu River basin and the migration, transformation, ecological effects, pollution source identification, and other issues need to be further studied. Societal concern should strengthen the management of plastic waste and reduce the sources and transport of land-based microplastic pollution to the ocean.

AcknowledgementsThe study was financially supported by the National Major Special Project for Water Pollution Treatment and Control 'Technology Integration of Watershed Ecological Function Zoning Management' Project (No. 2017ZX073 01-001) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC1407601).

Alam, F. C., Sembiring, E., Muntalif, B. S., and Suendo, V., 2019. Microplastic distribution in surface water and sediment river around slum and industrial area (case study: Ciwalengke River, Majalaya district, Indonesia). Chemosphere, 224: 637-645. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.188 (  0) 0) |

Aliabad, M. K., Nassiri, M., and Kor, K., 2019. Microplastics in the surface seawaters of Chabahar Bay, Gulf of Oman (Makran Coasts). Marine Pollution Bulletin, 143: 125-133. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.04.037 (  0) 0) |

Blcasing, M., and Amelung, W., 2018. Plastics in soil: Analytical methods and possible sources. Science of the Total Environment, 612: 422-435. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.086 (  0) 0) |

Blettler, M. C. M., Abrial, E., Khan, F. R., Sivri, N., and Espinola, L. A., 2018. Freshwater plastic pollution: Recognizing research biases and identifying knowledge gaps. Water Research, 143: 416-424. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2018.06.015 (  0) 0) |

Cole, M., Lindeque, P. K., Fileman, E., Clark, J., Lewis, C., Halsband, C., et al., 2016. Microplastics alter the properties and sinking rates of zooplankton faecal pellets. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(6): 3239-3246. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.5b05905 (  0) 0) |

Conley, K., Clum, A., Deepe, J., Lane, H., and Beckingham, B., 2019. Wastewater treatment plants as a source of microplastics to an urban estuary: Removal efficiencies and loading per capita over one year. Water Research X, 3: 100030. DOI:10.1016/j.wroa.2019.100030 (  0) 0) |

Cózar, A., Echevarría, F., González-Gordillo, J. I., Irigoien, X., Úbeda, B., Hernández-León, S., et al., 2014. Plastic debris in the open ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(28): 10239-10244. (  0) 0) |

Ding, L., Mao, R., Guo, X., Yang, X., Zhang, Q., and Yang, C., 2019. Microplastics in surface waters and sediments of the Wei River, in the northwest of China. Science of the Total Environment, 667: 427-434. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.332 (  0) 0) |

Eerkes-Medrano, D., Thompson, R. C., and Aldridge, D. C., 2015. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review of the emerging threats, identification of knowledge gaps and prioritisation of research needs. Water Research, 75: 63-82. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2015.02.012 (  0) 0) |

Engler, R. E., 2012. The Complex interaction between marine debris and toxic chemicals in the ocean. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(22): 12302-12315. DOI:10.1021/es3027105 (  0) 0) |

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., and Law, K. L., 2017. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances, 3(7): 1700782. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1700782 (  0) 0) |

Gong, X., Zhang, D., and Pan, X., 2020. Pollution and characterization of microplastics in the sediments of the Yellow River. Arid Zone Research, 37(3): 790-798 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.13866/j.azr.2020.03.29 (  0) 0) |

Han, L., Li, Q., Xu, L., Lu, A., Gong, W., and Wei, Q., 2020. The pollution characteristics of microplastics in Daliao River sediments. China Environmental Science, 40(4): 1649-1658 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.19674/j.cnki.issn1000-6923.2020.0184 (  0) 0) |

Jabeen, K., Su, L., Li, J., Yang, D., Tong, C., Mu, J., et al., 2017. Microplastics and mesoplastics in fish from coastal and fresh waters of China. Environmental Pollution, 221: 141-149. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.11.055 (  0) 0) |

Kanhai, L. D. K., Gardfeldt, K., Krumpen, T., Thompson, R. C., and O'Connor, L., 2020. Microplastics in sea ice and seawater beneath ice floes from the Arctic Ocean. Scientific Reports, 10: 5004. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-61948-6 (  0) 0) |

Kataoka, T., Nihei, Y., Kudou, K., and Hinata, H., 2019. Assessment of the sources and inflow processes of microplastics in the river environments of Japan. Environmental Pollution, 244: 958-965. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.111 (  0) 0) |

Koelmans, A. A., Mohamed Nor, N. H., Hermsen, E., Kooi, M., Mintenig, S. M., and De France, J., 2019. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: Critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Research, 155: 410-422. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2019.02.054 (  0) 0) |

Kor, K., and Mehdinia, A., 2020. Neustonic microplastic pollution in the Persian Gulf. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 150: 110665. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110665 (  0) 0) |

Lang, M., Yu, X., Liu. J., Xia, T., Wang, T., Jia, H., et al., 2020. Fenton aging significantly affects the heavy metal adsorption capacity of polystyrene microplastics. Science of the Total Environment, 722: 137762. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137762 (  0) 0) |

Law, K. L., and Thompson., R. C., 2014. Microplastics in the seas. Science, 345(6193): 144-145. DOI:10.1126/science.1254065 (  0) 0) |

Lebreton, L., and Andrady, A., 2019. Future scenarios of global plastic waste generation and disposal. Palgrave Communication, 5(6): 1-11. DOI:10.1057/s41599-018-0212-7 (  0) 0) |

Lebreton, L. C. M., Zwet, J., Damsteeg, J., Slat, B., Andrady, A., and Reisser, J., 2017. River plastic emissions to the world's oceans. Nature Communications, 8: 15611. DOI:10.1038/ncomms15611 (  0) 0) |

Lin, L., Zuo, L., Peng, J., Cai, L., Fok, L., Yan, Y., et al., 2018. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in an urban river: A case study in the Pearl River along Guangzhou City, China. Science of the Total Environment, 644: 375-381. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.327 (  0) 0) |

Liu, M., Lu, S., Song, Y., Lei, L., Hu, J., Lv, W., et al., 2018. Microplastic and mesoplastic pollution in farmland soils in suburbs of Shanghai, China. Environmental Pollution, 242(A): 855-862. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.07.051 (  0) 0) |

Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Cai, C., He, Y., Chen, L., Xiong, X., et al., 2020. Occurrence and characteristics of microplastics in the Haihe River: An investigation of a seagoing river flowing through a megacity in northern China. Environmental Pollution, 262: 114261. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114261 (  0) 0) |

Long, M., Moriceau, B., Gallinari, M., Lambert, C., Huvet, A., Raffray, J., et al., 2015. Interactions between microplastics and phytoplankton aggregates: Impact on their respective fates. Marine Chemistry, 175: 39-46. DOI:10.1016/j.marchem.2015.04.003 (  0) 0) |

Mao, Y., Li, H., Gu, W., Yang, G., Liu, Y., and He, Q., 2020. Distribution and characteristics of microplastics in the Yulin River, China: Role of environmental and spatial factors. Environmental Pollution, 265(A): 115033. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115033 (  0) 0) |

Murphy, F., Ewins, C., Carbonnier, F., and Quinn, B., 2016. Wastewater treatment works (WwTW) as a source of micro-plastics in the aquatic environment. Environmental Science and Technology, 50(11): 5800-5808. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.5b05416 (  0) 0) |

Park, C. H., Kang, Y. K., and Im, S. S., 2004. Biodegradability of cellulose fabrics. Applied Polymer Science, 94(1): 248-253. DOI:10.1002/app.20879 (  0) 0) |

Park, T., Lee, S., Lee, M., Lee, J., Lee, S., and Zoh, K., 2020. Occurrence of microplastics in the Han River and riverine fish in South Korea. Science of the Total Environment, 708: 134535. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134535 (  0) 0) |

Patti, T. B., Fobert, E. K., Reeves, S. E., and Silva, K. B., 2020. Spatial distribution of microplastics around an inhabited coral island in the Maldives, Indian Ocean. Science of the Total Environment, 748: 141263. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141263 (  0) 0) |

Qi, H., Wang, Y., Zhang, D., Wang, G., and Li, X., 2019. Microplastics in Moshui River sediment: Abundance, morphology and spatail distribution. Transactions of Oceanology and Limnology, 3: 69-77. DOI:10.13984/j.cnki.cn37-1141.2019.03.009 (  0) 0) |

Rose, D., and Webber, M., 2019. Characterization of microplastics in the surface waters of Kingston Harbour. Science of the Total Environment, 664: 753-760. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.319 (  0) 0) |

Sol, D., Laca, A., Laca, A., and Díaz, M., 2020. Approaching the environmental problem of microplastics: Importance of WWTP treatments. Science of the Total Environment, 740: 140016. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140016 (  0) 0) |

Sait, S. T. L., Sørensen, L., Kubowicz, S., Vike-Jonas, K., Gonzalez, S. V., Asimakopoulos, A. G., et al., 2020. Microplastic fibres from synthetic textiles: Environmental degradation and additive chemical content. Environmental Pollution, 268(B): 115745. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115745 (  0) 0) |

Stock, F., Kochleus, C., Bänsch-Baltruschat, B., Brennholt, N., and Reifferscheid, G., 2019. Sampling techniques and preparation methods for microplastic analyses in the aquatic environment – A review. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 113: 84-92. DOI:10.1016/j.trac.2019.01.014 (  0) 0) |

Tsering, T., Sillanpää, M., Sillanpää, M., Viitala, M., and Reinikainen, S., 2021. Microplastics pollution in the Brahmaputra River and the Indus River of the Indian Himalaya. Science of the Total Environment, 789: 147968. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147968 (  0) 0) |

Tien, C., Wang, Z., and Chen, C. S., 2020. Microplastics in water, sediment and fish from the Fengshan River system: Relationship to aquatic factors and accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by fish. Environmental Pollution, 265(B): 114962. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114962 (  0) 0) |

Wang, G., Lu, J., Tong, Y., Liu, Z., Zhou, H., and Xiayihazi, N., 2020. Occurrence and pollution characteristics of microplastics in surface water of the Manas River Basin, China. Science of the Total Environment, 710: 136099-136099. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136099 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X., Jiang, D., and Zhang, H., Simulation of non-point source pollution in Dagu Watershed, Jiaodong Peninsula based on AnnAGNPS. Journal of Agro-Environment Science Model, 33 (7): 1379-1387, http://doi.org/10.11654/jaes.2014.07.018 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Wang, W., Yuan, W., Chen, Y., and Wang, J., 2018. Microplastics in surface waters of Dongting Lake and Hong Lake, China. Science of the Total Environment, 633: 539-545. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.211 (  0) 0) |

Wen, X., Du, C., Xu, P., Zeng, G., Huang, D., Yin, L., et al., 2018. Microplastic pollution in surface sediments of urban water areas in Changsha, China: Abundance, composition, surface textures. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 136: 414-423. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.09.043 (  0) 0) |

Wessel, C. C., Lockridge, G. R., Battiste, D., and Cebrian, J., 2016. Abundance and characteristics of microplastics in beach sediments: Insights into microplastic accumulation in northern Gulf of Mexico estuaries. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 109(1): 178-183. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.06.002 (  0) 0) |

Xiong, X., Wu, C., Elser, J. J., Mei, Z., and Hao, Y., 2019. Occurrence and fate of microplastic debris in middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River – From inland to the sea. Science of the Total Environment, 659: 66-73. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.313 (  0) 0) |

Xiong, X., Zhang, K., Chen, X., Shi, H., Luo, Z., and Wu, C., 2018. Sources and distribution of microplastics in China's largest inland lake – Qinghai Lake. Environmental Pollution, 235: 899-906. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.081 (  0) 0) |

Xu, X., Jian, Y., Xue, Y., Hou, Q., and Wang, L., 2019. Microplastics in the wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs): Occurrence and removal. Chemosphere, 235: 1089-1096. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.197 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, S., Zhu, L., and Li, D., 2015a. Characterization of small plastic debris on tourism beaches around the South China Sea. Regional Studies Marine Science, 1: 55-62. DOI:10.1016/j.rsma.2015.04.001 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, S., Zhu, L., and Li, D., 2015b. Microplastic in three urban estuaries, China. Environmental Pollution, 206: 597-604. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.08.027 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, W., Huang, W., Yin, M., Huang, P., Ding, Y., Ni, X., et al., 2020. Tributary inflows enhance the microplastic load in the estuary: A case from the Qiantang River. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 156: 111152. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111152 (  0) 0) |

Zheng, Y., Li, J., Cao, W., Liu, X., Jiang, F., Ding, J., et al., 2019. Distribution characteristics of microplastics in the seawater and sediment: A case study in Jiaozhou Bay, China. Science of the Total Environment, 674: 27-35. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.008 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, G., Wang, Q., Zhang, J., Li, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, M., et al., 2020. Distribution and characteristics of microplastics in urban waters of seven cities in the Tuojiang River Basin, China. Environmental Research, 189: 109893. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109893 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, Q., Zhang, H., Fu, C., Zhou, Y., Dai, Z., Li, Y., et al., 2018. The distribution and morphology of microplastics in coastal soils adjacent to the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea. Geoderma, 322: 201-208. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.02.015 (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21