2) Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266071, China;

3) Fisheries College of Jimei University, Xiamen 361021, China

Bivalve mollusks are frequently exposed to different environmental stresses and invasive or pathogenic microbes. As invertebrate, their internal defense functions are partially undertaken by haemocytes (Cheng et al., 1984). Haemocytes are responsible for recognition, phagocytosis, encapsulation, and elimination of non-self components (Hine, 1999; Lin et al., 2011a). Bivalve haemocytes are generally classified into two types, granulocytes and hyalinocytes (Hine, 1999). Granulocytes contain many cytoplasmic granules and have the ability to engulf microbial pathogens. They contain a mixture of hydrolytic enzymes that contribute to intracellular killing and are more phagocytic than hyalinocytes. Haemocyte populations in some extent vary with pathogen infections or environmental factors (Carballal et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2010). Therefore, the total haemocyte counts and the total granulocyte counts are important immune parameters.

Bivalve haemocytes could also express and secrete immune factors like pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). PRRs are the molecules in the immune signal transduction pathway and a variety of immune effectors, which also play an important role in bivalve defense (Nikapitiya et al., 2008). The PRRs are responsible for recognizing the pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and the immune recognition mediated by PRRs can trigger intracellular signaling cascades to activate the transcription of immune effectors. Recently, a lot of PRRs have been identified and characterized from scallop, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), lectins, and β-1, 3-glucan binding protein (LGBP), which could be stimulated by lipopolysaccharide and bacteria (Siva et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015). Many immune effectors involving in clearance of invasive pathogens have also been identified in scallop, such as endogenous enzymes lysozyme, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and prophenoloxidase (PO) (Pipe et al., 1993; Xing et al., 2008), which play essential roles in immune defense against pathogens, assisting, modulating and accelerating immunological processes in haemocytes (Biggar et al., 1977).

The scallop Chlamys farreri is one of the most important economic mollusks in China, and is widely cultured in the northern coastal area. Commercial harvest of scallop is threatened by high mortality in summer, which is caused by complex interactions among host, pathogen and environment, especially high temperature, various invaders or pathogens (Wan et al., 1999; Xiao et al., 2005). As a main pathogen of scallops, Vibrio anguillarum can stimulate the variations of immune parameters and its infection ability can be affected by environmental temperature. However, few studies have been conducted on the relationship between vibrio infection effect and water temperatures.

In this paper, two concentrations of V. anguillarum were injected into scallop C. farreri which were then cultured at 11℃, 17℃, 23℃ and 28℃, respectively. After the scallops were cultured for some time, the counts of total haemocytes and granulocytes, expressions of six immunityrelated genes, LPS and β-1, 3-glucan (CfLGBP), Lectin (CfLec-2), Toll like receptor (CfTLR), Lyso-zyme (CfLYZ), Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase (CfCu/Zn-SOD) and prophenoloxidase (CfPO) in haemocytes were measured. The aim of this research was to study how water temperature affects the immune reaction of haemocytes and the defense capacity of C. farreri.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Experimental Animals, Bacterial Strains and AntibodiesScallops (Chlamys farreri, 7 ± 0.3 cm shell height) were collected from Qingdao Harbor, Shandong province, China. They were acclimated at 17℃ in fiberglass tanks containing filtered seawater with a salinity of 31, and were fed on spirulina powder. The seawater was aerated and renewed daily. After two weeks, scallops were divided into four groups. One group was remained at 17℃, while the water temperatures of other three groups were gradually changed to 11℃, 23℃, and 28℃, respectively.

Gram-negative bacteria V. anguillarum (ATCC 43305/ MH67) was isolated from diseased flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) and was stored in -80℃ in our laboratory. The bacteria was cultured in marine broth 2216E at 28℃ to OD600nm = 0.2, and then was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 5 min to be harvested.

Monoclonal antibody (MAb) against haemocytes of C. farreri (MAb 1F7) and MAb against granulocyte (MAb 6H7) were produced by our laboratory. They were used as primary antibodies in ELISA (Xing and Zhan, 2005; Lin et al., 2011b).

2.2 Bacterial ChallengePrior to the experiment, the bacteria pellet was suspended in 0.01 mol L-1 phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) andadjusted to 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109 CFU mL-1 respectively. PBS included 0.14 mol L-1 sodium chloride, 3 mmol L-1 potassium chloride, 8 mmol L-1 disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate, 1.5 mmol L-1 potassium phosphate monobasic, and the pH was 7.4, then scallops from each temperature group were injected with 100 μL of different concentrations of V. anguillarum, and the control groups were injected with 100 μL PBS.

Preliminary results showed that when V. anguillarum concentration exceeded 108 CFU mL-1, 100% mortality occurred within 12 h at 28℃, while there was no significant difference in mortality between 104 CFU mL-1 group and control group at each temperature. Therefore 104 CFU mL-1 (low) and 107 CFU mL-1 (high) were selected as V. anguillarum concentrations for subsequent experiments. The scallops in each temperature group were further divided into four subgroups with 100 scallops in each one. They were then injected in the adductor muscle with 100 μL of V. anguillarum suspension with a concentration of 104 or 107 CFU mL-1, and were refered as 104 CFU mL-1 group and 107 CFU mL-1 group. For control group, 100 μL of PBS was injected. Five to seven scallops were randomly sampled from each subgroup at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72 h post injection.

2.3 Haemocytes PreparationHaemolymph was withdrawn from the adductor muscle sinus with sterilized syringes and simultaneously mixed (1:1, v/v) with precooled anticoagulant (phosphate buffered saline containing EDTA, PBS-E; 0.14 mol L-1 NaCl, 2.7 mmol L-1 KCl, 8.1 mmol L-1 Na2HPO4, 1.5 mmol L-1 KH2PO4, 19.1 mmol L-1 EDTA, pH 7.4). The mixture of haemolymph was centrifuged at 500×g for 10 min at 4℃ to collect the haemocyte pellet. The haemocyte pellet was washed and re-suspended with equal volume of PBS, sonicated for 4 min, and then were used in ELISA and quantitative real-time PCR analyses. For each scallop, haemolymph was withdrawn only one time throughout the experiment.

2.4 ELISATotal haemocytes counts (THC) and granulocytes counts were determined by ELISA. Haemocyte suspensions were coated in a micro plate (100 μL per well). At the same time, 50 mL of 0.5 mol L-1 EDTA was added to each well to eliminate endoenzyme activities. After incubated overnight at 4℃ and washed with PBS-T, each coated well was blocked with 200 μL of 3% BSA for 1 h at 37℃, washed thrice with PBS-T, and incubated successively with 100 μL of anti-haemocyte MAb 1F7, or anti-granulocyte MAb 6H7 as primary antibodies, and 100 μL of GAMAP as secondary antibodies. The samples were washed three times between each steps. After the last wash, color reaction was developed in 100 μL of 0.1% (w/v) pNPP (Sigma) in 0.05 mol L-1 carbonate-bicarbonate buffer containing 0.5 mmol L-1 MgCl2 for each well. Then the reactions were stopped by the addition of 50 μL of 2 mol L-1 NaOH. Finally, the absorbance values were measured at 405 nm with an automatic ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, US). Each measurement was performed in sextuplicate.

2.5 RNA Extraction and cDNA SynthesisThe Total RNA of haemocytes suspension was isolated with TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer's instruction and treated with RNase-free DNase (Promega RQ1 DNase I). RNA concentration was measured spectrophotometrically on a NanoDrop reader (Saveen & Werner ApS, Denmark) and the integrity and purity of RNA was examined by running in 1.0% agarose gel. The first-strand synthesis was carried out based on Promega M-MLV RT Usage information (Promega, Madison, WI) using oligo (dT)-adapter as primer. The reaction was performed at 42℃ for 1 h, terminated by heating at 95℃ for 5 min. The cDNA mix was stored at -80℃ for subsequent quantitative real-time PCR.

2.6 Quantitative Real-Time PCRThe quantitative real-time PCR was performed with the SYBR Green on an ABI 7300 Real-Time Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA) to investigate the expressions of CfLGBP, CfLec-2, CfTLR, CfLYZ, CfCu/ZnSOD and CfPO genes. Elongation factor 1α (CfEF-1α) gene was employed as house-keeping gene. All primers used in this assay were shown in Table 1. The quantitative real-time PCR was carried out in a total volume of 25 µL, containing 12.5 µL of 2× SYBR Green Master Mix (Takara, Tokyo, Japan), 4 µL of the 100 times diluted cDNA, 0.5 µL of each primers (10 mmol L-1), and 7.5 µL of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. The quantitative real-time PCR program included 95℃ for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95℃ for 5 s, 55℃ for 30 s, and 72℃ for 30 s. A melting curve of PCR products (55-95℃) was performed to ensure the detection of a single specific product. The expressions of these immunity-related genes were normalized to the expression of CfEF-1α gene for each sample. The comparative Ct method (2ΔΔCt method) was used to analyze the expression level of immunityrelated genes (Zhao et al., 2007a).

|

|

Table 1 Primers used for quantitative real-time PCR of immunity-related genes in C. farreri |

All data were expressed as means ± S.D (n = 6). Statistical analysis was carried out using the software Origin 8.0. The differences were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and P < 0.05 was considered as significance. Each measurement was performed in sextuplicate.

3 Results 3.1 Mortalities of Scallop in Challenge GroupsAfter challenged with 104 or 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum, the mortalities of scallops were showed in Table 2. No significant death was observed in 104 CFU mL-1 group at 11℃, 17℃ and 23℃, while the death occurred at 28℃. In 107 CFU mL-1 groups, the death occurred at all temperatures. In the meantime, it showed that high temperature caused high mortality.

|

|

Table 2 The cumulative morality of C. farreri with different treatments |

The results of ELISA showed that, in 104 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum challenge groups, there were no significant changes in THC at 11℃, 17℃ and 28℃ compared to the control groups (0.513 ± 0.0513) (P < 0.05) (Figs. 1A, B). With 23℃ treatment, the absorbance at 405 nm (OD405nm) was increased obviously at 3 h (0.525 ± 0.0023) (P < 0.05) (Figs. 1C and D). In 107 CFU mL-1 group, THC changed significantly at all temperatures during a part of experimental period compared to that in the control group (P < 0.05). At 11℃, THC increased obviously at 3 h (0.555 ± 0.0023) (P < 0.05), while dropped at 24 h and 36 h, and the lowest OD405nm was at 24 h (0.459 ± 0.003) (P < 0.05). At 17℃, THC increased significantly at 6 h and 12 h. At 23℃, THC increased obviously at 3 h (0.577 ± 0.0033) and 6 h (0.547 ± 0.001), then it decreased to the lowest at 24 h (0.393 ± 0.093), and then increased. However, it was still lower than the control level at 36 h and 48 h (P < 0.05). At 28℃, THC decreased significantly in all the experiment time especially at 24-48 h, which indicated that high temperature inhibit the immunity of haemocytes.

|

Fig. 1 Total haemocytes counts of C. farreri cultured at different water temperatures after injected with two concentrations of V. anguillarium suspension. Asterisk represents the statistical significance (P < 0.05). A, 11℃; B, 17℃; C, 23℃; D, 28℃. |

Considering the results with two bacteria concentrations, the extent of variation of THC was higher in 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum treatment than in 104 CFU mL-1, especially at 28℃ (P < 0.05).

3.3 Variation of Granulocytes CountsThe results of ELISA showed that 104 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum had no effects on granulocytes counts (GC) at 11℃ and 17℃ compared to control level (0.492 ± 0.004, Figs. 2A and 2B). At 23℃, GC significantly decreased only at 12 h (0.445 ± 0.007) (Fig. 2C). At 28℃, GC declined significantly at 24 h (0.415 ± 0.007) and 36 h, and then recovered gradually to control level (Fig. 2D). However, 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum induced significantly changes in GC at all temperatures during a part of experimental period compared to the control group (P < 0.05). At 11℃, GC decreased obviously at 6-48 h, and the lowest OD405nm was at 12 h (0.436 ± 0.006). At 17℃, GC decreased significantly at 12-48 h, the lowest OD405nm was at 24 h (0.425 ± 0.007). At 23℃, GC decreased obviously during all the experiment time, and the lowest OD405nm was at 12 h (0.387 ± 0.003). At 28℃, OD405nm increased obviously at 3 h (0.557 ± 0.004) and 6 h (0.525 ± 0.001), and then decreased dramatically till the end of the experiment, with the lowest value at 36 h (0.328 ± 0.003).

|

Fig. 2 Granulocytes counts of C. farreri cultured at different water temperatures after injected with two concentrations of V. anguillarium suspension. Asterisk represents the statistical significance (P < 0.05). A, 11℃; B, 17℃; C, 23℃; D, 28℃. |

Comparing the treatments with two bacteria concentrations, the extent of variation in GC was higher in 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups than in 104 CFU mL-1 groups, especially at 28℃ (Fig. 2).

3.4 Variances in CfLGBP ExpressionAfter infected with V. anguillarum, expression of CfLGBP gene was significantly up-regulated or down-regulated during a part of experimental period compared to the control, and the extent of variation of CfLGBP expression was higher in 107 CFU mL-1 group than in 104 CFU mL-1 group, especially at 28℃ (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). In 104 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups, CfLGBP gene showed no significant change at 11℃ (Fig. 3A). CfLGBP expression was up-regulated at 6 h at 17℃ (1.55-fold), and at 12 h at 23℃ (1.75-fold) (Figs. 3B, 3C). At 28℃, CfLGBP only significantly changed at 3 h and 6 h (1.55-fold) (Fig. 3D). While in 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups, CfLGBP expression was significantly up-regulated at 6 h (1.56-fold) and 12 h at 11℃. At 17℃, CfLGBP expression was obviously up-regulated at 3-24 h, and at 12 h the relative expression was up to 2.63-fold. At 23℃, the highest CfLGBP expression was at 6 h (3.1-fold). At 28℃, the CfLGBP expression reached the highest level at 6 h (2.9-fold), and was significantly down-regulated at 48 h and 72 h (0.65-fold and 0.38-fold, respectively) (Fig. 3).

|

Fig. 3 Temporal mRNA expression patterns of LGBP gene in C. farreri cultured at different water temperatures after two concentrations of V. anguillarum injection. Asterisk represents the statistical significance (P < 0.05). A, 11℃; B, 17℃; C, 23℃; D, 28℃. |

After infection, CfLec-2 expression was significantly upregulated or down-regulated during the experimental period compared to the control group, and the extent of variation of CfLec-2 expression was higher in 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups than that in 104 CFU mL-1 groups, especially at 28℃ (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4). CfLec-2 expression in 104 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups increased at 12 h at both 11℃ and 17℃, at 6-12 h at 23℃, and showed no significant changes at 28℃. In 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum group, CfLec-2 expression was significantly up-regulated at 6-24 h at both 11℃ and 17℃, 6-48 h at 23℃ (maximum increase was 5.78 fold at 12 h), and 3-24 h at 28℃ (maximum increase was 3.77-fold at 12 h).

|

Fig. 4 Temporal mRNA expression patterns of Lectin-2 gene in C. farreri cultured at different water temperatures after two concentrations of V. anguillarum injection. Asterisk represents the statistical significance (P < 0.05). A, 11℃; B, 17℃; C, 23℃; D, 28℃. |

After infection, expression of CfTLR gene was significantly up-regulated or down-regulated compared to the control group, and the extent of variation of CfTLR was higher in 107 CFU mL-1 group than that in 104 CFU mL-1 group, especially at 28℃ (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). Challenged with 104 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum, expression of CfTLR gene was significantly down-regulated at 3 h, 6 h, and upregulated at 24 h at 11℃; was down-regulated at 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h at 17℃; down-regulated at 3 h, 6 h, and up-regulated at 24 h at 23℃; and no variances were observed at 28℃. In 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups, the CfTLR expression was significantly up-regulated at 12-48 h (about 2.5-fold at 24 h) at 11℃, at 12 h and 24 h (about 3.5-fold at 12 h) at 17℃, at 6-24 h (about 4.5-fold at 6 h) at 23℃, and at 3-24 h (about 3.5-fold at 6 h) at 28℃.

|

Fig. 5 Temporal mRNA expression patterns of CfTLR gene in C. farreri cultured at different water temperatures after two concentrations of V. anguillarum injection. Asterisk represents the statistical significance (P < 0.05). A, 11℃; B, 17℃; C, 23℃; D, 28℃. |

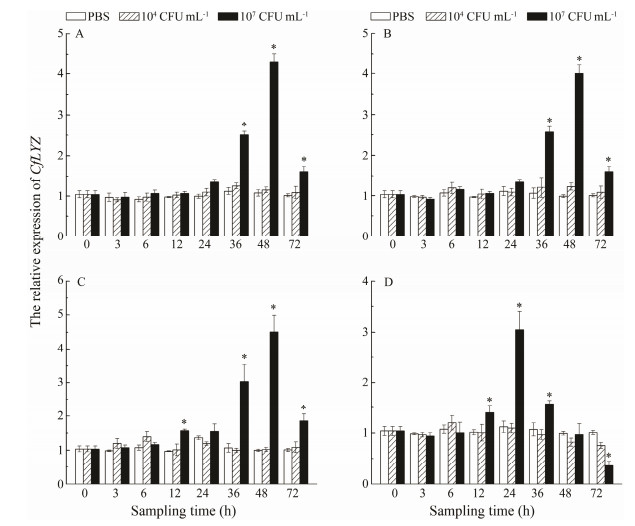

The extent of variation in CfLYZ expression was significantly higher in 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups than that in 104 CFU mL-1 groups at all temperatures (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6). There were no variances in the expression of CfLYZ in 104 CFU mL-1 groups at all the experiment temperatures. However, in 104 CFU mL-1 groups, the expression of CfLYZ significantly increased at 36-72 h at both 11℃ and 17℃; increased at 12 h, 36-72 h at 23℃ (about 4.56-fold at 6 h); increased at 12-36 h and decreased at 72 h at 28℃.

|

Fig. 6 Temporal mRNA expression patterns of CfLYZ gene in C. farreri cultured at different water temperatures after two concentrations of V. anguillarum injection. Asterisk represents the statistical significance (P < 0.05). A, 11℃; B, 17℃; C, 23℃; D, 28℃. |

After V. anguillarum infection, the extent of variation in CfSOD expression was higher in 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups than that in 104 CFU mL-1 groups at all temperatures (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7). In 104 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups, CfSOD expression was up-regulated at 3 h at 11℃, 17℃ and 28℃, and 3-12 h at 23℃. In 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups, CfSOD expression was up-regulated at 3-12 h at 11℃ (2.3-fold at 3h), at 3-6 h at 17℃ (3.2-fold at 3h), at 3-12 h, at 36 h at 23℃ (3.4-fold at 6 h), and at 3-6 h at 28℃ (3.9-fold at 6 h).

|

Fig. 7 Temporal mRNA expression patterns of CfSOD gene in C. farreri cultured at different water temperatures after two concentrations of V. anguillarum injection. Asterisk represents the statistical significance (P < 0.05). A, 11℃; B, 17℃; C, 23℃; D, 28℃. |

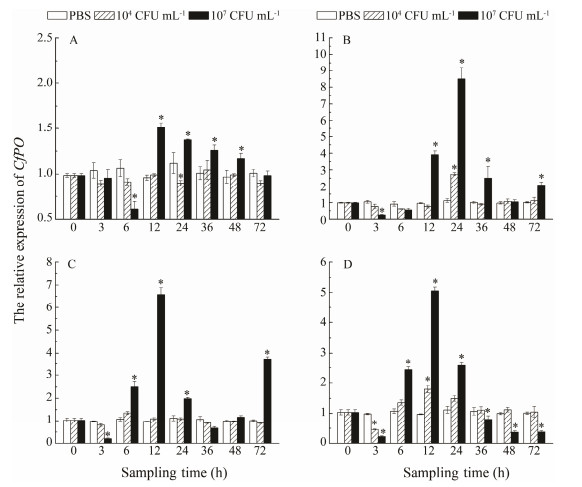

The extent of variation in CfPO expression was higher in 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum group than that in 104 CFU mL-1 groups at all temperatures (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8). In 104 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups, CfPO expression was down-regulated at 24 h at 11℃, up-regulated at 24 h at 17℃, and down-regulated at 3 h, up-regulated at 12 at 28℃, and had no variances at 23℃. In 107 CFU mL-1 V. anguillarum groups, CfPO expression was down-regulated firstly at 3h, and increased sharply at 12-48 h at 11℃ (1.5 fold at 12 h). At 17℃, it was down-regulated firstly at 3 h, and increased sharply at 12-36 h (8.5 fold at 24 h). At 23℃, it was down-regulated firstly at 3 h, and increased sharply at 6-24 h (6.7 fold at 12 h), then there was another increase at 72 h. At 28℃, it was down-regulated firstly at 3 h, and increased sharply at 6-24 h (5.0 fold at 12 h), then decreased again at 48 h and 72 h.

|

Fig. 8 Temporal mRNA expression patterns of CfPO gene in C. farreri cultured at different water temperatures after two concentrations of V. anguillarum injection. Asterisk represents the statistical significance (P < 0.05). A, 11℃; B, 17℃; C, 23℃; D, 28℃. |

Vibrio anguillarum is one of the pathogens that can cause mass mortality of scallop when water condition is deteriorated (Zhang et al., 2007). In this study, the THC, GC and the expressions of 6 immunity-related genes in scallop were investigated after the scallop was injected with two concentrations of V. anguillarum and cultured at different temperatures. The aim of this research is to explore the function of vibrio infection at different temperatures, which will be helpful for the healthy culture of scallops. Monoclonal antibodies against haemocytes or granulocytes were applied in measuring THC and GC using ELISA, which illustrated specifically the effect of V. anguillarum infection on haemocytes immunity of scallop.

The results showed that at the same temperature, THC and GC in the scallops infected with high concentration of V. anguillarum showed stronger changes and longer duration than those in the scallops infected with low concentration of V. anguillarum, and THC increased significantly in a short time. This is because the cells proliferate or haemocytes migrate immediately to the haemolymph to respond to pathogen invasion (Cheng et al., 2004). As the infection processed and mortality of scallop occurred, haemocytes gradually decreased. However, granulocytes showed a complete decrease in the whole experiment period. Granulocytes are the main immune haemocytes in bivalve. They degranulate and release lysosomes, and have an important function during the phagocytosis of invading particles. This process can cause the granulocyte counts reduce to a certain extent. Furthermore, some of them may transform into transparent haemocytes (Moura et al., 2015; Ji et al., 2017). Therefore, GC decreased in the whole infection process. With the clearance of V. anguillarum, the THC and GC gradually recovered to normal levels. This indicated that the granulocytes play an important role in the response to vibrio infection.

The high concentration infection had a significant temperature correlation. When the water temperature increased, the immune response of shellfish, the proliferation of haemocytes, as well as other physiological processes were accelerated (Choi et al., 2006). As the proliferation of haemocytes and the pathogenicity of V. anguillarum increased, the organism was able to deal with the infection in some extent. The more significant differences occurred at 23℃ than at 11℃ and 17℃. At 28℃, shellfish is under the high temperature stress. The intracellular enzyme activity is reduced, and the immune system function is inhibited (Cheng et al., 2004). With the release of reactive oxygen species, high temperature can enhance the cell self-killing effect. Additionally, when the environmental temperature is 28℃, V. anguillarum proliferates at a faster rate. Thus, infection with high concentration of V. anguillarum at 28℃ can cause huge pressure to the immune system of scallops (Zhao et al., 2007b), which leads to the high mortality. During this process, the body's energy is mainly used to fight against the invading pathogen, and the number of haemocytes, especially granulocytes, was relatively low (Wang et al., 2013).

At the same temperature, the expression levels of immunity-related genes in the haemocytes infected with high concentration of V. anguillarum were higher than those in the haemocytes infected with low concentration of V. anguillarum. The expression level of CfLec-2 gene was similar to those of CfLGBP and CfTLR (Wang et al., 2014), as the pattern recognition receptors, CfLGBP, CfLec-2 and CfTLR genes were highly expressed before 24 h. They responded rapidly and reacted to bind the pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of the invading bacteria immediately after the infection (Pees et al., 2015), which was more obvious in the scallops with more serious infection. The CfTLR expression in this study is similar to previous studies (Mateo et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011).

The initial expression of CfPO gene was significantly up-regulated, indicating that the gene expression in C. farreri was activated in different stages rather than synchronously. Studies have shown that LGBP has the function of activating the phenol oxidase progenitor system. The body uses raw materials and energy to synthesize and express some genes firstly, and then LGBP gradually activates the expression of PO gene (Cerenius et al., 2004). The expressions of CfSOD, CfLYZ genes showed the enzymes were involved in the phagocytosis with hemolytic activity (Choi et al., 2006). Haemocytes are capable of producing a mass of superoxide products in response to pathogens (Cheng et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2016). Working together with the phagocytosis, the antioxidant enzymes can eliminate the invading bacteria at the presence of SOD and LYZ. They are the main immunity-related enzymes in scallop haemocytes and can respond rapidly during immune defense (Chen et al., 2011).

The results showed that haemocytes of scallop directly or indirectly participate in the immune defense. The decrease in the number of haemocytes or granulocytes indicates the decrease of scallop immunity. When the temperature is high, the number of haemocytes or granulocytes varied more significantly. The haemocytes might be a potential marker for scallop immunity.

5 ConclusionsIn conclusion, water temperature had significant effects on haemocytes and granulocytes counts and immunity-related genes in scallop after V. anguillarum infection. The cell amount, the pattern recognition receptors, the enzymes of the haemocytes varied significantly in the process, haemocytes responded at both cellular and transcriptional levels. It indicated that the haemocytes were directly related to the immunity and might be potential marker for scallop defense.

AcknowledgementsThis research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018 YFD0900504), the Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (No. QNLM2016ORP0307), and the Key Technology R & D Program of China (No. 2012BAD17B02).

Biggar, W. D. and Sturgess, J. M., 1977. Role of lysozyme in the microbicidal activity of rat alveolar macrophages. Infection and Immunity, 16(3): 974-982. (  0) 0) |

Carballal, M. J., López, C., Azevedo, C. and Villalba, A., 1997. In vitro study of phagocytic ability of Mytilus galloprovincialis Lmk. haemocytes. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 7(6): 403-416. DOI:10.1006/fsim.1997.0094 (  0) 0) |

Cerenius, L. and Söderhäll, K., 2004. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunological Reviews, 77(1): 21-26. (  0) 0) |

Chen, G., Zhang, C., Li, C., Wang, C., Xu, Z. and Yan, P., 2011. Haemocyte protein expression profiling of scallop Chlamys farreri response to acute viral necrosis virus (AVNV) infection. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 35(11): 1135-1145. DOI:10.1016/j.dci.2011.03.022 (  0) 0) |

Chen, M., Yang, H., Delaporte, M. and Zhao, S., 2007. Immune condition of Chlamys farreri in response to acute temperature challenge. Aquaculture, 271(1): 479-487. (  0) 0) |

Cheng, T. C., 1984. A classification of molluscan hemocytes based on functional evidences. Comparative Pathobiology, 6: 111-146. (  0) 0) |

Cheng, W., Juang, F. M. and Chen, J. C., 2004. The immune response of Taiwan abalone Haliotis diversicolor supertexta and its susceptibility to Vibrio parahaemolyticus at different salinity levels. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 16(3): 295-306. DOI:10.1016/S1050-4648(03)00111-6 (  0) 0) |

Cheng, W., Tung, Y. H., Liu, C. H. and Chen, J. C., 2006. Molecular cloning and characterisation of cytosolic manganese superoxide dismutase (cytMn-SOD) from the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 21(1): 102-112. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2005.10.009 (  0) 0) |

Choi, Y. S., Lee, K. S., Yoon, H. J., Kim, I., Sohn, H. D. and Jin, B. R., 2006. Bombus ignitus Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1): cDNA cloning, gene structure, and up-regulation in response to paraquat, temperature stress, or lipopolysaccharide stimulation. Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology Part B Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 144(3): 365-371. (  0) 0) |

Hine, P. M., 1999. The inter-relationships of bivalve haemocytes. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 9(5): 367-385. DOI:10.1006/fsim.1998.0205 (  0) 0) |

Ji, A., Li, X., Fang, S., Qin, Z., Bai, C., Wang, C. and Zhang, Z., 2017. Primary culture of Zhikong scallop Chlamys farreri hemocytes as an in vitro model for studying host-pathogen interactions. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 125(3): 217. DOI:10.3354/dao03145 (  0) 0) |

Lin, T. T., Xing, J., Jiang, J., Tang, X. and Zhan, W. B., 2011a. β-glucan-stimulated activation of six enzymes in the haemocytes of the scallop Chlamys farreri at different water temperatures. Aquaculture, 315(3): 213-221. (  0) 0) |

Lin, T. T., Xing, J., Sheng, X. Z., Tang, X. Q. and Zhan, W. B., 2011b. Development of a monoclonal antibody specific to granulocytes and its application for variation of granulocytes in Chlamys farreri after acute viral necrobiotic virus (AVNV) infection. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 30: 1348-1353. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2011.03.010 (  0) 0) |

Mateo, D., Greenwood, S., Araya, M., Berthe, F., Johnson, G. and Siah, A., 2010. Differential gene expression of gamma-actin, Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2) and interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK-4) in Mya arenaria haemocytes induced by in vivo infections with two Vibrio splendidus strains. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 34(7): 710-714. (  0) 0) |

Moura, R. M., Melo, A. A., Carneiro, R. F., Rodrigues, C. R., Delatorre, P., Nascimento, K. S., Saker, S. S., Nagano, C. S., Cavada, B. S. and Sampaio, A. H., 2015. Hemagglutinating/ Hemolytic activities in extracts of marine invertebrates from the Brazilian coast and isolation of two lectins from the ma-rine sponge Cliona varians and the sea cucumber Holothuria grisea. Anais Da Academia Brasileira De Ciencias, 87(2): 973-984. DOI:10.1590/0001-3765201520140399 (  0) 0) |

Nikapitiya, C., Zoysa, M. D. and Lee, J., 2008. Molecular characterization and gene expression analysis of a pattern recognition protein from disk abalone, Haliotis discus discus. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 25(5): 638-647. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2008.08.002 (  0) 0) |

Pees, B., Yang, W., Zárate-Potes, A., Schulenburg, H. and Dierking, K., 2015. High innate immune specificity through diversified C-Type lectin-like domain proteins in invertebrates. Journal of Innate Immunity, 8(2): 129. (  0) 0) |

Pipe, R. K., Porte, C. and Livingstone, D. R., 1993. Antioxidant enzymes associated with the blood cells and haemolymph of the mussel Mytilus edulis. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 3(3): 221-233. DOI:10.1006/fsim.1993.1022 (  0) 0) |

Siva, V. S., Yang, C., Yang, J., Wang, L., Wang, L., Zhou, Z., Qiu, L. and Song, L., 2012. Association of CfLGBP gene polymorphism with disease susceptibility/resistance of Zhikong scallop (Chlamys farreri) to Listonella anguillarum. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 32(6): 1117-1123. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2012.03.017 (  0) 0) |

Tang, B., Liu, B., Wang, X., Yue, X. and Xiang, J., 2010. Physi-ological and immune responses of Zhikong scallop Chlamys farreri to the acute viral necrobiotic virus infection. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 29(1): 42-48. (  0) 0) |

Wan, Y. T. and Xiang, J. H., 1999. Studies on causation of the mass mortality of Chlamys farreri. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 30: 770-774. (  0) 0) |

Wang, J., Wang, L., Yang, C., Jiang, Q., Zhang, H., Yue, F., Huang, M., Sun, Z. and Song, L., 2013. The response of mRNA expression upon secondary challenge with Vibrio anguillarum suggests the involvement of C-lectins in the immune priming of scallop Chlamys farreri. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 40(2): 142-147. (  0) 0) |

Wang, M., Wang, L., Guo, Y., Sun, R., Yue, F., Yi, Q. and Song, L., 2015. The broad pattern recognition spectrum of the Toll-like receptor in mollusk Zhikong scallop Chlamys farreri. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 52(2): 192-201. (  0) 0) |

Wang, M., Yang, J., Zhou, Z., Qiu, L., Wang, L., Zhang, H., Gao, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, L. and Zhao, J., 2011. A primitive Toll-like receptor signaling pathway in mollusk Zhikong scallop Chlamys farreri. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 35(4): 511-520. DOI:10.1016/j.dci.2010.12.005 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X. W., Zhao, X. F. and Wang, J. X., 2014. C-type Lectin binds to β-Integrin to promote hemocytic phagocytosis in an invertebrate. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(4): 2405-2414. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M113.528885 (  0) 0) |

Xia, X., Huang, C., Zhang, D., Zhang, Y., Xue, S., Wang, X., Zhang, Q. and Guo, L., 2016. Molecular cloning, characterization, and the response of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase and catalase to PBDE-47 and -209 from the freshwater bivalve Anodonta woodiana. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 51: 200-210. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2016.02.025 (  0) 0) |

Xiao, J., Yang, H., Zhang, G., Zhang, F. and Guo, X., 2005. Studies on mass summer mortality of cultured Zhikong scallops (Chlamys farreri Jones et Preston) in China. Aquaculture, 250(3): 602-615. (  0) 0) |

Xing, J. and Zhan, W. B., 2005. Characterisation of monoclonal antibodies to haemocyte types of scallop (Chlamys farreri). Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 19: 17-25. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2004.10.006 (  0) 0) |

Xing, J., Lin, T. T. and Zhan, W. B., 2008. Variations of enzyme activities in the haemocytes of scallop Chlamys farreri after infection with the acute virus necrobiotic virus (AVNV). Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 25(6): 847-852. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2008.09.008 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, X., Zhang, S. and Liu, H., 2007. Review on research of Vibrio anguillarum-pathogenicity to aquatic animals in mari-culture. Modern Fisheries Information, 22(1): 16-19. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, J., Song, L., Li, C., Ni, D., Wu, L., Zhu, L., Wang, H. and Xu, W., 2007. Molecular cloning, expression of a big defensin gene from bay scallop Argopecten irradians and the antimicrobial activity of its recombinant protein. Molecular Immunology, 44(4): 360-368. DOI:10.1016/j.molimm.2006.02.025 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, J., Song, L., Li, C., Zou, H., Ni, D., Wang, W. and Xu, W., 2007. Molecular cloning of an invertebrate goose-type lysozyme gene from Chlamys farreri, and lytic activity of the recombinant protein. Molecular Immunology, 44(6): 1198-1208. DOI:10.1016/j.molimm.2006.06.008 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18