2) State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing 100081, China;

3) Public Meteorological Service Center of CMA, Beijing 100081, China;

4) Shandong Meteorological Bureau, Jinan 250031, China;

5) Laboratory of Cloud-Precipitation Physics and Severe Storms (LACS), Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China

Tropical cyclone (TC) precipitation can be divided into two categories. One is the precipitation within the TC circulation, which includes core region rain, envelop rain or spiral rain band, mesoscopic or microscopic system rain, unstable rain, and squall line rain; the other is TC remote precipitation (TRP), which occurs in areas in front of and away from the cyclone (Chen, 2006). Precipitation, especially torrential rainfall related to TCs, is among the serious concerns of forecasters. However, the TRP can be easily ignored and lead to suboptimal forecast performance (Cong, 2011; Cong et al., 2012).

The extreme rainfall in Henan in July 2021 set a record for hourly precipitation in Mainland China, with a maximum of 201.9 mm in Zhengzhou, resulting in heavy economic losses and casualties. On July 20, the distance between the center of TC In-fa and Zhengzhou was approximately 2000 km, exceeding the maximum radius (1100 km) of TC circulation in the Northwest Pacific Ocean (Elsberry et al., 1994). The precipitation in Zhengzhou belongs to the TRP of In-fa. In-fa plays an important role known as moisture alteration, transporting water vapor to Henan Province continually from the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea through west – southwest airflow and from the Pacific through east – southeast airflow, contributing to rainfall persistence (Ran et al., 2021; Buer et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). TRP has been consistently observed during other heavy precipitation events that have greatly affected China. For example, the largest flood in the Yellow River was influenced by TC5810 Winnie (Ding et al., 1987). During the remote influence of TC6308, the 7-day accumulated precipitation in Zhangmo, Hebei Province, reached 2050 mm (Tao, 1980). The heavy rainstorm in Beijing in 2012 was connected with TC1208 Vincente, causing 79 deaths and economic losses of 11.64 billion yuan (Yu, 2012; Xu et al., 2014).

The current number of studies on TRP is considerably less than that on precipitation within the TC circulation, focusing mostly on three aspects, namely, the definition and identification of TRP, the climate characteristics of TRP, and the mechanism of TRP. Among these concepts, the definition and identification of TRP serve as the basis for the subsequent research on TRP climate characteristics and mechanisms. The broad definition of TRP proposed by Chen (2007) is as follows: first, precipitation occurs outside the circulation of TC; second, a close connection is found between this precipitation and TC. In accordance with this definition, Cong (2011) selected the north of 10˚N and the west of 135˚E as the study area and added a condition that the daily precipitation of at least five stations ≥ 50 mm under the same weather system influence to artificially identify TRP. This research is among the few studies on TRP characteristics in China. Cote (2007) introduced the idea of predecessor rain events ahead of TCs, which are similar to TRP and developed a quantitative-qualitative approach to identify TRP. The identification method includes three measurement standards, as follows: the duration of the precipitation is more than six hours, and the radar reflectivity value in the affected area is greater than or equal to 35 dBZ; the 24-hour precipitation is greater than or equal to 100 mm; according to the radar image, a clear boundary must be found between the precipitation area and the TC circulation precipitation area, and a deep water vapor channel is observed between the TC and the precipitation area. A similar method was developed by Ding et al. (2017) with the following parameters: precipitation must be outside the TC circulation; the 24-hour precipitation must be greater than or equal to 50 mm; a clear water vapor channel must exist between the precipitation area and the TC on 850 hPa; a mid-latitude weather system must be deployed along the water vapor channel.

The three methods are used to identify TRP from either subjective or subjective-objective perspectives, with limited objective identification methods. This condition restricts the consistent study of TRP. An objective method for identifying the TRP should be developed to better understand its characteristics and to select representative TCs for TRP mechanism research.

Ren et al. (2001) established an objective synoptic analysis technique for determining TC precipitation from daily precipitation data. Wang et al. (2006) improved the technique by changing two fixed parameters. A detailed introduction of this method and a comparison analysis between this objective method and the expert subjective method are discussed by Ren et al. (2007).

Previous studies on objective TC precipitation identification mainly focused on precipitation within the TC circulation. In this study, we attempt to extend this approach to identify TRP, developing an objective synoptic analysis technique for TRP (OSAT_TRP). Section 2 discusses the data used in this study. Section 3 presents a detailed introduction to the steps of the OSAT_TRP. The rationality of this method is demonstrated through examples presented in Section 4. Section 5 illustrates the typical synoptic-scale environments of the TRP. Section 6 presents the summary and further discussions.

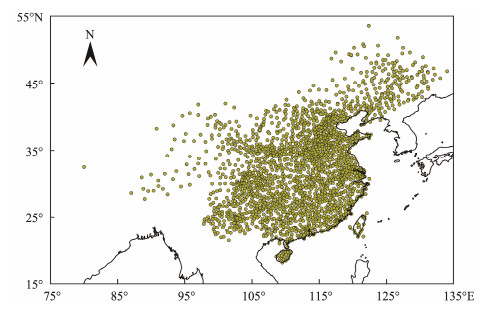

2 Data1) The daily precipitation data in this article refer to the historical observed precipitation data during 1979 – 2021 archived at 24-hour intervals at 12 UTC by the China Meteorological Administration (CMA), including 2024 rain gauge stations in China (Fig.1).

|

Fig. 1 Distribution of 2027 national meteorological stations. |

2) The historical best-track data for the period 1979 – 2021 with 6-hour intervals, including the position and strength of TCs, are obtained from the Shanghai Typhoon Institute (Ying et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2021).

3) The reanalysis data of temperature, atmospheric pressure, specific humidity, wind speed, and other meteorological elements are obtained from the European Center for Medium-range Weather Prediction (ECMWF), with spatial resolution of 0.25˚ × 0.25˚ and time resolution of four times a day (00, 06, 12, and 18 UTC) (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=form). The east – west and south – north vertical water vapor fluxes can also be obtained from ERA5, with the same spatial and temporal resolution as the reanalysis data of meteorological elements (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=form).

3 Objective Synoptic Analysis Technique for TRP (OSAT_TRP)Referring to several previous definitions of TRP (Chen, 2007; Cote, 2007; Ding et al., 2017), the three conditions that it should satisfy are summarized as follows: 1) the precipitation occurs outside the circulation of TCs, 2) the precipitation is affected by TCs, and 3) a gap exists between the TRP and TC rain belt. In this study, TRP is separated from daily precipitation data, and these conditions are realized through the following steps. This method is developed from the OSAT, which is referred to as OSAT_TPR. The specific steps are discussed in the following section.

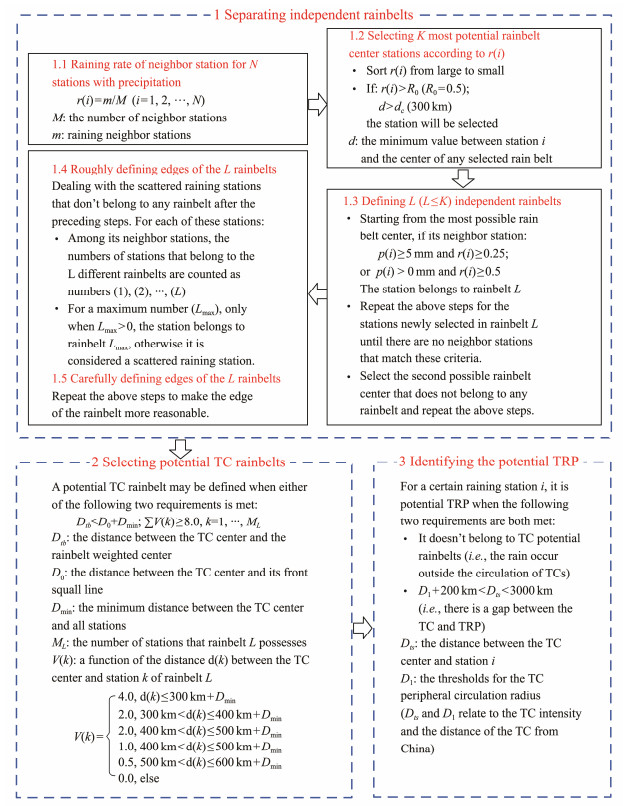

3.1 Identifying the Potential TRPInitially, independent rain belts are separated, and those related to TCs' remote effects are distinguished according to their distance from the TCs. We call this step identifying 'the potential TRP' because this step doesn't include determining the precipitation whether is affected by TCs. The three sub-steps of identifying the potential TRP are shown in Fig.S1. Independent rain belts are separated, and potential TC rain belts are selected. These steps are the same as those of OSAT (Ren et al., 2007); thus, we only provide a brief introduction here.

Firstly, the rainfall rate (r) of the neighbor station within 200 km for N stations with precipitation is calculated. The station with the maximum r is considered the most potential rain belt center, and then the next station with the largest r outside a range of 300 km away from the selected center is searched. These operations are carried out when r is greater than 0.5. Ren et al. (2007) suggested that this value should be generally set to 0.3 – 0.5. The study of the climate characteristics of TC precipitation that uses the OSAT preferred 0.5 (Yang, 2019). To maintain consistency, 0.5 is selected for this study. This operation is continuously performed to find K most potential rain belt center stations. The station belongs to rain belt L when the precipitation of its neighbor station, p, is greater than 5 mm and r is greater than 0.25 or when p is greater than 0 mm, and r is greater than 0.5. The above steps are repeated for the stations newly selected in rain belt L until no neighbor stations match these criteria. The second possible rain belt center that does not belong to any rain belt is selected by repeating the same steps. Then, we obtain L independent rain belts and some scattered rain stations that do not belong to any rain belt stations. For each of these scattered stations, among its neighbor stations, the number of stations that belong to different L rain belts is identified. For a maximum number (Lmax), only when Lmax > 0, the station belongs to the rain belt Lmax; otherwise, it is considered a scattered raining station. These steps are repeated to obtain a more reasonable edge of the rain belt. Finally, according to the distance between the rain belt weighted centers, the stations in the rain belt and the TC center are used to select potential TC rain belts (Fig.S1 Substep 2).

The potential TC rain belts refer to those within the TC circulation or the rain belts with numerous stations within the TC circulation. The TRP refers to the precipitation outside the potential TC rain belt because it requires a gap with precipitation within the TC circulation. Thus, if a station exhibits precipitation that does not fall within the potential TC rain area but satisfies the criteria of D1 + 200 km < Dts < 3000 km, then it belongs to potential TRP. In the equation, Dts indicates the distance between the TC center and the station, and D1 represents the maximum radius of the flow system surrounding the TC, distinguishing the precipitation associated with TCs from those with other weather systems. This empirical value fluctuates according to the TC intensity level (maximum continuous wind speed). To ensure a clear boundary between TRP and TC circulation, avoiding two adjacent stations experience situations where one belongs to TC precipitation and the other belongs to TRP. Considering that the length of the mesoscale convection rain band usually does not exceed 200 km. Thus, after testing the lengths of 100, 200, 300, and 500 km, 200 km has been added to D1, based on the OSAT empirical value, to ensure that TRP precipitation occurs outside the TC circulation. Moreover, the maximum remote impact distance is set to 3000 km. D1 and another parameter D0 (distance between the TC center and the squall line) used in OSAT_TRP are the same as the ones used in Ren et al. (2007). In addition, no TRP is experienced when the number of TRP stations in the entire rain belt does not exceed 3. The two conditions required by TRP, namely, the rain occurs outside the circulation of TC and a gap between the TRP and TC rain belt can be achieved through this approach.

3.2 Identifying the Strong Water Vapor Transport Belt from TCIn Section 3.1, the potential TRP is identified, but the objective assessment that the precipitation is affected by TCs has not yet been performed. Water vapor transport is very important to TRP and has been broadly used in TRP research. Integrated horizontal water vapor transport (IVT) is frequently used to describe the strong water vapor transport belt as an 'atmospheric river' (Zhu and Newell, 1998; Neiman et al., 2008; Rutz et al., 2014). In addition, Henny et al. (2022) used IVT to illustrate the connection between TC and TRP. Thus, the IVT is applied to objectively determine a strong water vapor transport belt from TCs to potential TRP. If this condition is found, then TRP exists.

Forecasters usually focus on the weather situation at 00 UTC when making daily precipitation forecasts. Therefore, the IVT at 00 UTC is used to identify the strong water vapor transport belt from TC. IVT is calculated as follows:

| $ IVT = \sqrt {I_x^2 + I_y^2}, $ |

where Ix and Iy are the west-to-east and south-to-north components of the integrated water vapor flux from the surface of the earth to the top of the atmosphere.

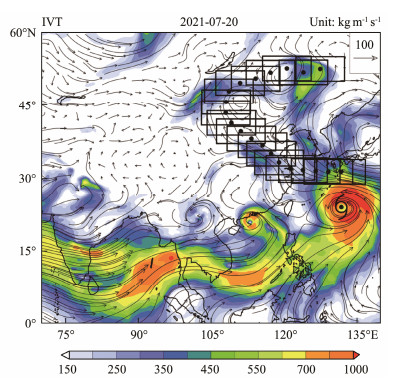

The three specific steps to identify the strong water vapor transport belt from TC are discussed in the following section. Fig.2 depicts the schematic for determining the strong steam conveyor belt at 00 UTC on July 20, 2021.

|

Fig. 2 Schematic of identifying the strong water vapor transport belt launched by TC (considering the objective separation of TRP on July 20, 2021, of TC In-fa). The shading and streamline show the integrated horizontal water vapor transport (unit: kg m−1 s −1). The position of the TC In-fa is marked with a black TC symbol. The water vapor transport track and region are shown in black points and rectangles, respectively. |

First, the TC water vapor transport track is obtained. Selecting the starting point is crucial for this step, and TC In-fa on July 20, 2021, is considered an example. If the start point is extremely close to the TC center, then the determined water vapor transport track curves around the TC center. If it is extremely far, then the water vapor transport track does not belong to the TC. When the radius and water vapor transport intensity of the circulation of TC varies greatly, a variable value of the distance between the 'starting point' and TC center is expected. Surrounding the center of the TC is an extremely strong and wide water vapor transport belt. A continuous IVT exceeding 500 kg m−1 s−1 from the TC center is considered the TC circulation, considering that the 95th percentile value of the IVT in East Asia (0˚ – 60˚N, 70˚E – 180˚E) is 539 kg m−1 s−1. The starting point of water vapor transport is set within this range to achieve a water vapor transport track revolving around the TC. According to the synoptic model (Cong, 2011) and three dominant IVT modes under the interactions of TCs and mid-low latitude systems (Tang et al., 2023), we also tried using other thresholds. Following numerous tests, the starting point is set to a changeable point, which is the first grid point located north of the TC center and with IVT < 500 kg m−1 s−1. The start point selected is moved along the overall direction, θ, of the water vapor within the 5˚ × 5˚ range centered on this point for 250 km to obtain the next track point. θ can be calculated as follows:

| $ IV{T_U} = \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^n {IV{T_{u, i}}}, $ | (1) |

| $ IV{T_V} = \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^n {IV{T_{v, i}}}, $ | (2) |

| $ \theta = {\tan ^{ - 1}}\frac{{IV{T_V}}}{{IV{T_U}}}. $ | (3) |

Subsequently, the track point of water vapor transport is determined. The maximum distance between the TRP and TC is set at 3000 km. Thus, frequent relocations of the TRP, even excessively far from the TC center, yielding an impractical result, is not a concern. The water vapor transport in China is performed 20 times. The water vapor transport track of TC In-fa obtained by this method on July 20, 2021, is shown in black points in Fig.2.

Second, the relationship area is determined. The 5˚ × 10˚ rectangular area centering around the track point of the water vapor transport is shown in black rectangles in Fig.2.

Third, the strong water vapor transport belt from TC is identified. It is composed of the grid points with IVT ≥ 150 kg m−1 s−1 in the relationship area.

3.3 Distinguishing TRPThe potential TRP identified in Section 3.1 is interpolated to 0.25 × 0.25 grid point. If the interpolated potential TRP overlaps with the strong water vapor transport belt from TC and is located north of the TC center, then it is determined as TRP. Water vapor in mid-latitude may also be transported to low-latitude areas through the southwest airflow on the east side of the TCs. During the weakening stage of TCs, such water vapor transport tracks may occasionally be identified. According to the TRP composite analysis and conceptual model (Galarneau et al., 2010; Cong, 2011), the precipitation related to this type of water vapor transport does not belong to the TRP. Moreover, previous studies (Cong, 2011) have shown that almost no TRP is located in the south of the TC. To maintain consistency in objective judgment conditions, the parameter of being located north of the TC has been added.

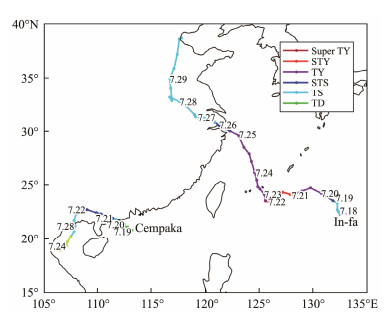

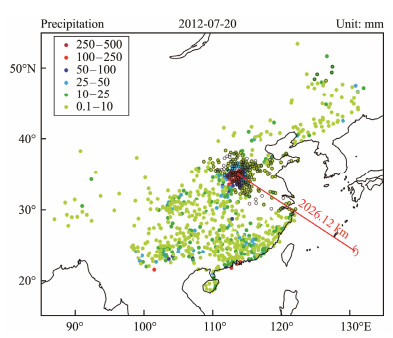

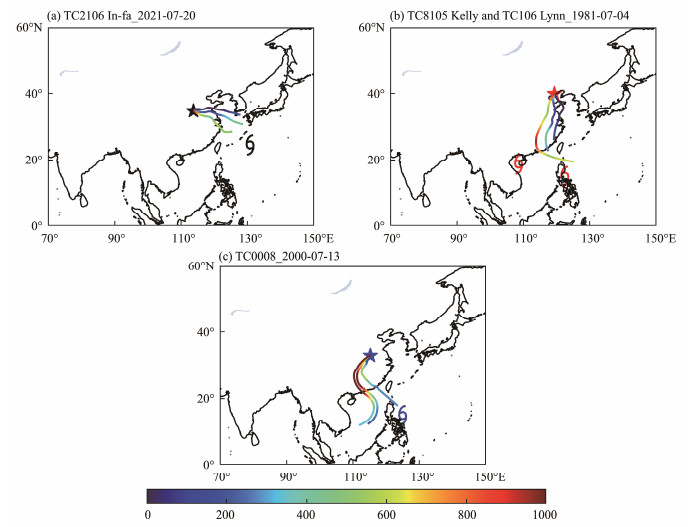

4 Verification of the OSAT_TRP Method in TC Cases 4.1 TRP Case Identification Results 4.1.1 TRP of TC2106 In-faTC2106 In-fa generated on the Northwest Pacific at 18 UTC on July 17, 2021 (Fig.3) and continuously intensified as it progressed northwest. At 06 UTC on July 20, it intensified into a typhoon. After two landfalls in Zhejiang, it shifted toward the north direction. On July 30, it transitioned into an extra TC over the Bohai Sea. The TC lasted up to 95 hours on the mainland of China, longer than any TC since 1949. Affected by TC In-fa, Henan Province experienced an extremely heavy rainfall event rarely seen in history from July 18 to 22. The maximum daily rainfall in Zhengzhou occurred on July 20, with a daily rainfall of 552.5 mm, more than twice the precipitation record of this station. In Section 3.3, we have presented the OSAT_TRP schematic and steps for distinguishing the TRP. Fig.4 shows the precipitation identification results, where the color dot represents the daily precipitation and the black circle symbolizes the TRP. The excessive precipitation in Zhengzhou was recognized as a TRP.

|

Fig. 3 Track (solid line) and intensity grades (colors) of In-fa (TC2106) and Cempaka (TC2107). |

|

Fig. 4 Daily precipitation (color dot) and TRP separated by OSAT_TRP (black circle) of TC In-fa on July 20, 2021. The position of the TC In-fa is marked with a red TC symbol. The TC center and the center of precipitation, Zhengzhou, are connected with red solid lines. |

At 00 UTC on July 20, the TC center was 2026.12 km away from the largest precipitation center, Zhengzhou, exceeding the outer circulation radius of In-fa (Figs.2 and 4). According to OSAT, no TC precipitation is found on this day. The TRP occurred outside the circulation of TC and does not belong to the TC precipitation. In addition, the precipitable water vapor in the entire region of Henan Province reached 60 mm and increased to 65 mm continually on July 21. This finding demonstrates that the water vapor content is extremely high, and the characteristics of air mass are comparable to those above tropical oceans. Fig.2 shows that these air masses primarily originate in the low latitude area and are transported by In-fa. The TRP is closely related to TC. In summary, the identification results are consistent with the actual situation and satisfy the three requirements of TRP in Section 3.

Another TC Cempaka is found in the Northwest Pacific while TC In-fa exists (Fig.3). Cempaka developed into a tropical storm from the South China Sea tropical depression around 00 UTC on July 19, and its numbering ended at 15 UTC on July 24. The water vapor transmission is relatively weak from Cempaka to the TRP area. Cempaka did not produce TRP on July 20, as indicated by the OSAT_TRP, given the absence of a strong water vapor transport belt from Cempaka attached to the precipitation area on that day (Fig.2).

The identification results of OSAT_TRP show that 388 of the 906 TCs that produced TRP between 1979 and 2020 were accompanied by at least one TC in the Northwest Pacific. Despite the fact that In-fa and Cempaka exist simultaneously, the shortest distance between them still reached 1779.6 km at 00 UTC on July 21. Therefore, further discussion on whether the OSAT_TRP can still reasonably detect the TRP when two TCs are close to each other or when only one TC exists in the Northwest Pacific is important. Therefore, the TRP identification results of TC8105, Kelly, with the largest accumulated TRP, are selected for analysis. During its impact period, another TC Lynn (TC8106) existed. In addition, the single TC with the largest accumulated TRP, the eighth tropical depression of 2000, is selected for analysis to further prove the rationality of OSAT_TRP.

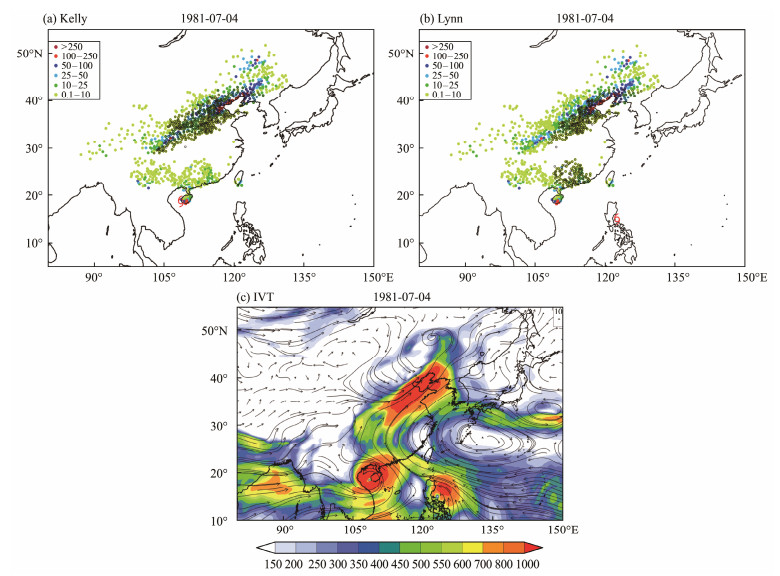

4.1.2 TRP of TC8105 Kelly and TC8106 LynnTC Kelly and Lynn originated as tropical depressions in the Northwest Pacific at 08 UTC on June 28 and 08 UTC on July 2, 1981, respectively. As they progressed westward, they intensified and developed into tropical storms near the east of the Philippines Island. They landed in Hainan Province as a super typhoon and in Guangdong Province as a severe tropical storm on July 4 and 7, respectively. Subsequently, they dissipated on July 5 and 8 in Laos and Guangxi Province, respectively (Fig.5). From June 27 to July 1, the precipitation center gradually shifted from the Yangtze River basin to the southeast coastal area, transitioning from a latitudinal to longitudinal distribution. The precipitation gradually shifted to North China on July 2. Heavy rain was experienced over the Bohai Sea on July 4, and 183.6 mm of daily precipitation was recorded in Funing, Hebei Province.

|

Fig. 5 Track (solid line) and intensity grades (colors) of Kelly (TC8105) and Lynn (TC8106). |

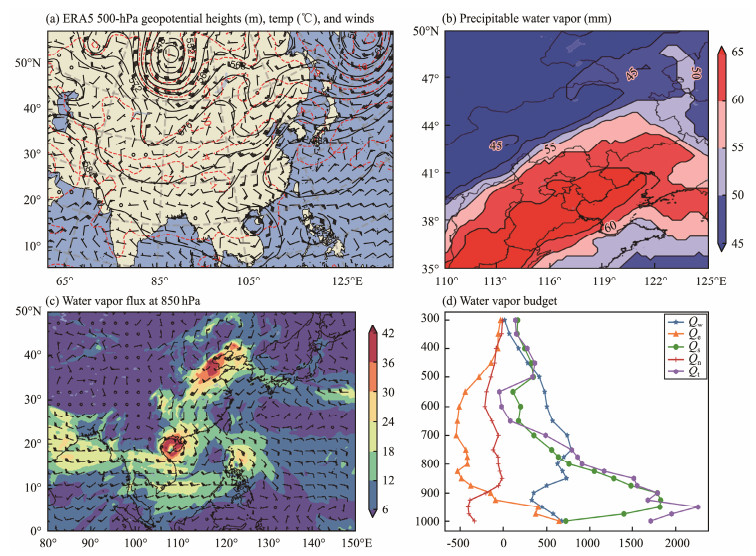

The TRP mainly occurred on July 4. Fig.6a shows that, at 00 UTC on July 4, the subtropical high is located over the ocean of southern Japan, with the ridge trending east – west and near 25˚N. The westerly trough moving eastward is blocked by the subtropical high on the west, and the southerly flow on its east converges into the southwest flow in front of the westerly trough at approximately 30˚N. The atmospheric circulation pattern of TC in the south and westerly trough provides a typical large-scale background that can benefit the occurrence of mid-latitude TRP.

|

Fig. 6 (a) 850 hPa geopotential heights (black solid line, unit: dagpm) temperature (red dashed line, unit: ℃), and wind (wind arrow); (b) precipitable water vapor (mm); (c) water vapor flux (shading, unit: g (cm s hPa) −1) at 850 hpa (d) water vapor budget at 1000 – 300 hpa (unit: kg m−1 s−1) at 00 UTC on July 4 1981. |

The 'box' model is a rectangular area. The main water vapor transport direction and the budget of water vapor in this box can be obtained by calculating the water vapor flux on the boundary of the rectangle (Miao et al., 2005). Qw, Qe, Qs, and Qn represent the water vapor fluxes at the western, eastern, southern, and northern boundaries of the 'box', respectively. Qt indicates the total budget of water vapor in the 'box'. The results show that the 'box' area of precipitation (30˚ – 45˚N, 105˚ – 125˚E) has a positive water vapor budget that concentrates at low altitudes below 700 hPa (Fig.6d), mostly from the southern boundary, and then the western boundary. The eastern boundary has weak water vapor, and the water vapor outflows from the northern boundary. The southeast flow on the east side of Kelly, together with the eastern TC and the subtropical high, transports water vapor to the main precipitation areas covered by a high value of water vapor flux over 25 g (cm s hPa) −1. At the same time, there is a strong water vapor transport channel on the west side of Kelly, which transports water vapor from the Bay of Bengal to TC and then to the precipitation area (Fig.6c). The warm and humid air mass with the precipitable water vapor greater than 50 mm covers most of the primary precipitation area, while the maximum value has reached 65 mm (Fig.6b). This finding indicates that the TRP is closely related to TC water vapor transport. Moreover, the ∆θse in the primary precipitation area exceeds 16 K, showing that the atmosphere is in a convective and unstable state (figure omitted). Once the trigger conditions for ascent are satisfied, intense convective weather occurs with the continual transfer of water vapor.

The identification result of OSAT_TRP shows that the TRP in the Bohai Rim region is jointly affected by the two TCs, while the Sichuan-Shanxi and Guangdong-Guangxi areas are affected remotely by TCs Kelly and Lynn, respectively. The precipitation in Guangdong-Guangxi is also related to Lynn's precipitation within the TC circulation (Fig.7). This finding is consistent with the water vapor transport of the two TCs. Specifically, the TC in the west affects the areas located further west, while the TC in the east exhibits less impact on the precipitation in the north but simultaneously affects Guangdong and Guangxi. In conclusion, the TRP obtained by the OSAT_TRP complies with the results of synoptic analysis findings and the three TRP determination standards. The OSAT_TRP is also capable of identifying precipitation caused by the combined influence of the two TCs.

|

Fig. 7 Daily precipitation (color dot, unit: mm), TRP separated by OSAT_TRP (black circle) of (a) Kelly (TC8105) and (b) Lynn (TC8106); (c) water vapor flux of the entire layer at 00 UTC on July 4, 1981 (color contour map, unit: kg m−1 s−1). |

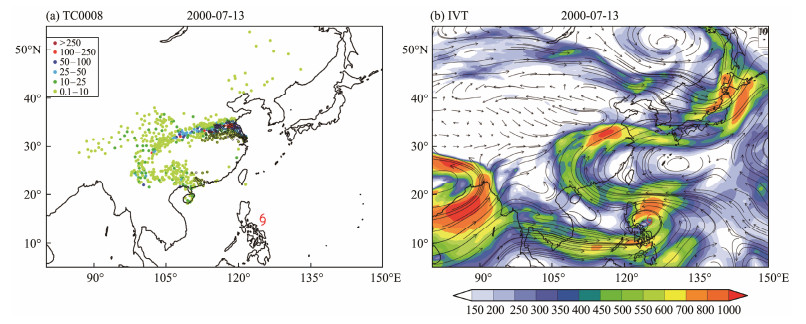

These examples demonstrate how a station can be influenced by TCs' remote effect when more than one TC is experienced in the Northwest Pacific. The behavior of OSAT_TRP when only one TC exists in the Northwest Pacific and when the TC is weak is determined. For further analysis, the tropical depression on August 8, 2000, is considered an example. On July 13, no TC precipitation was observed. The TRP was mainly located in Jiangsu, southern Shandong, southern Henan, and northern Anhui Province (Fig.8), outside the TC circulation. TC also played a crucial role in transferring water vapor to the TRP area. The identified TRP area satisfies the three criteria. OSAT_TRP can also successfully obtain a single and weak TRP of the TC.

|

Fig. 8 (a) Daily precipitation (color dot, unit: mm) and TRP separated by OSAT_TRP (black hollow circle) of TC0008 (tropical depression); (b) water vapor flux of the entire layer (color contour map, unit: kg m−1 s−1) at 00 UTC on July 13, 2000. |

The HYSPLIT trajectory model uses the Lagrangian perspective to track the movement of particles (Draxler and Hess, 1998). We use this model to track the source of air masses at the center of maximum TRP. The results show that (Fig.9) the transport track of the water vapor in the station, with the maximum TRP in the low troposphere for three days, is consistent with the obtained strong water vapor transport belt through the OSAT_TRP.

|

Fig. 9 Water vapor transmission track reaching the maximum TRP station. The colored lines indicate the track and its height (unit: m). |

In this section, the TRP values of 25 TCs obtained by OSAT_TRP and Cong's subjective and objective combination method (Cong, 2011) are compared. The results and explanations of the discrepancies are shown in Table 1. The table shows that 80% of the identified TRPs by the OSAT_TRP method are consistent with those of Cong. However, some differences between the recognition results of five TCs and those of Cong are also observed. The TRP of Matsa (TC0509) recognized by Cong cannot be obtained by OSAT_TRP due to the minor IVT in most areas of Shandong Province at 00 UTC on August 4 and 5, 2005. Although the identification of the close relationship between TRP and TC through the strong water vapor transport belt launched by the TC is inconsistent with the subjective results in a few cases, the overall rationality cannot be ignored.

|

|

Table 1 Comparison of TRP obtained by OSAT_TRP and Cong (2011) |

In addition, the two main reasons for the discrepancies in the results are as follows: the numbering of TC is discontinued and the lack of gap between the TRP obtained by OSAT_TRP and the TC rain belts. The former can be solved by extending the track of the historical TCs through the detection of TC residual vortex. The latter can be adjusted by changing the parameter of OSAT_TRP in different situations. However, the parameters used are common in OSAT, and the identification results have been proven to be reasonable in general. Therefore, to maintain consistency, a few discrepancies between the OSAT_TRP and subjective results are within the acceptable range. Therefore, the TRP obtained by OSAT_TRP is reasonable and consistent with the results obtained by combining subjective and objective methods.

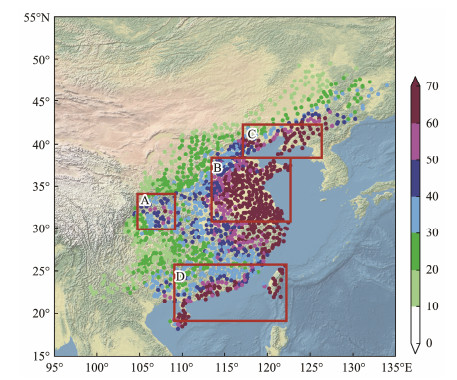

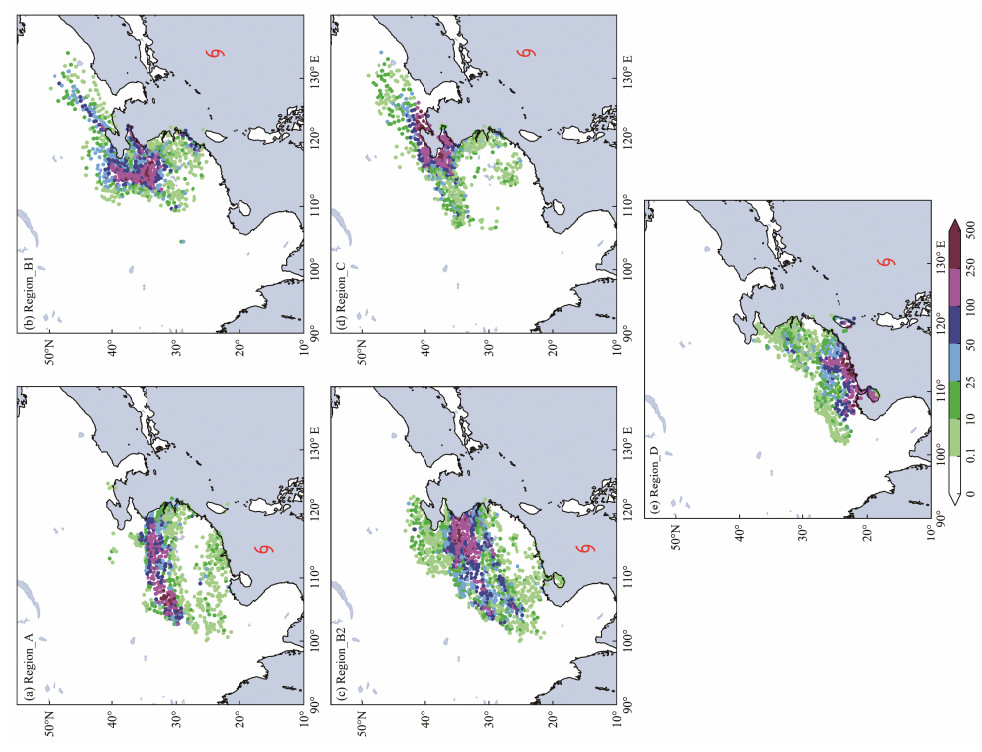

5 Application of the OSAT_TRP – Synoptic-Scale Environments of the TRPBased on the OSAT_TRP, 906 out of 1251 TCs generated in the western Pacific (including the South China Sea) between 1979 and 2020 generated TRP. Four key regions of TRP are obtained using the precipitation days, annual average precipitation of TRP (Fig.10), and TRHP obtained by the OSAT_TRP from 1979 to 2020. The adjacent areas include the Sichuan and Shanxi Provinces (region_A), the coast of the Yellow Sea (region_B), the northern coast of the Bohai Sea (region_C), and the southern coast area (region_D). Typical TCs with cumulative TRP ranking in the top 10 and a group of TCs with similar positions to typical TCs but without TRP (No_TRP group) are selected for comparison (marked as region_A0, region_B0, region_C0, and region_D0). Moreover, given the two types of TC tracks related to TRP in region_B, this area is further divided into regions_ B1 and region_ B2 (Jia et al., 2024). Most of the TCs related to TRP in region_A and region_B2 are westbound TCs, whereas northwest-bound TCs are found in other regions. The similarities and differences in weather systems during TRP occur in different areas based on these TCs. The sum of the maximum daily TRP of these TCs and their averaged locations are shown in Fig.11.

|

Fig. 10 Annual average precipitation of TRP from 1979 to 2020. The red box shows the four key regions. |

|

Fig. 11 Sum of the maximum daily TRP of TCs in key regions (unit: mm) and the average position of TCs. |

Fig.12 shows that TRPs are accompanied by the South Asia high at 200 hPa. The 1248 dagpm isoheight line covered most of southern China. TCs are located at the southeast of this line, while the TRPs appear at the south of the northernmost side of the line.

|

Fig. 12 Composited geopotential height field (black contour line, unit: dagpm, 1248 dagpm line is marked in blue) and wind (wind vector, unit: m s−1) at 200 hPa. The upper-level jet with wind speed greater than 30 m s−1 is color-shaded. The red dot line shows the TRP scope. |

The westbound TCs are mainly located at approximately 115˚E and 15˚N. TRPs are strip-like and distributed approximately 20˚ latitudes to the north of the TC. Meanwhile, an upper-level jet is found north of the TRP, contributing to upper-level divergence and ascending in the TRP region. For northwest-bound TCs located at approximately 135˚E, 20˚N, the TRP is approximately 10˚ latitudes north and 20˚ longitude west of the TC with mass-like distribution. Contrary to westbound TCs, the upper-level jet in the north of TRPs is weak. When the 1248 dagpm isoheight line extends to the west of 145˚E and envelops TCs, TRP occurs in southern China.

No South Asian High at 200 hPa exists in the NO_TRP group. The upper-level jet is stronger, broader, and further south than the TRP group. The wind speed greater than 32 m s−1 almost covered the 25˚ – 45˚N in China, which is conducive to downward motion, inhibiting the precipitation.

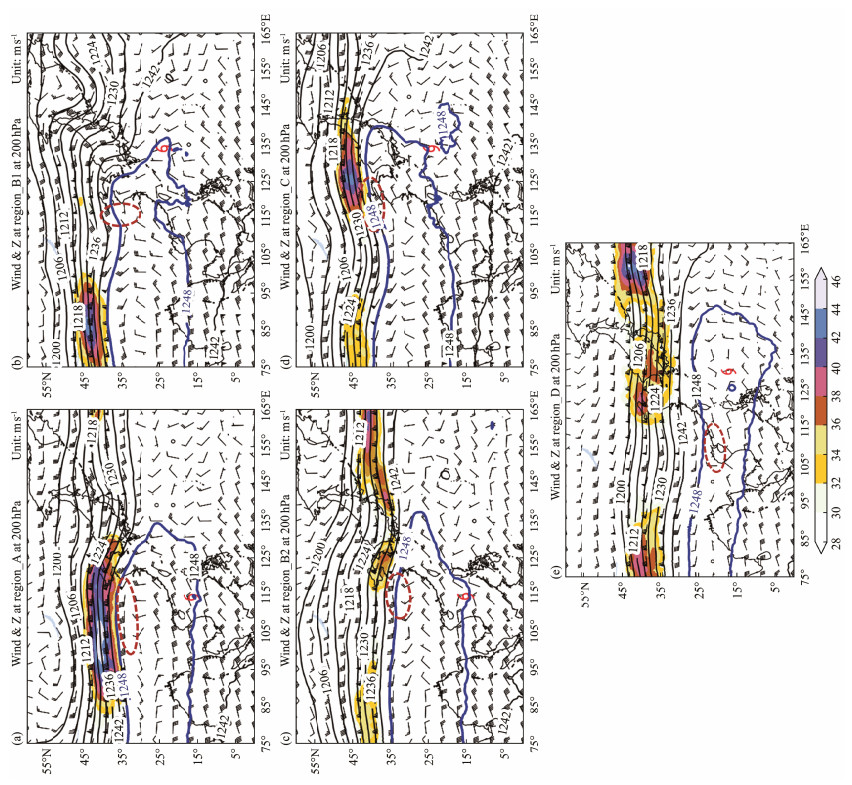

5.2 Synoptic-Scale Analyses at 500 hPaThe 588 dagpm line (Fig.13) for westbound TCs is located at approximately 25˚N, extending to the west of 115˚E. TCs are found on the southwest of the Western Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH). A south-to-west wind shear is found near the TRP, which is conducive to precipitation formation. The south of 584 dagpm line and the northwest of 588 dagpm line enclose the TRP rain belts.

|

Fig. 13 Composited geopotential height field (588 dagpm line is marked in blue) and wind at 850 hPa. |

In the northwest-bound TCs, although the 588 dagpm line does not reach the southwest of the precipitation area, the 584 dagpm line forms a high-pressure ridge in the eastern coastal area, overlapping with the ridge in the mid-latitude. TRP forms on the west of the high-pressure ridge, north of 584, and south of the 580 dagpm line. Wind shear exists in the same manner as the TRP related to westward TCs. In addition, the northwest dry and cold airflow satisfies the southward warm and humid airflow brought by TCs, conducive to the precipitation formation. The TRP in region_D relates to binary TC or TC residual vortices near Hainan Island.

In the No_TRP group, the 588 dagpm line is distributed in a block shape in the Northwest Pacific Ocean, with its center located around 155˚E. The westward TCs are far apart, whereas the northwest TCs are on the southwest side, strengthening the southeast wind between them. However, to its north is a flat westerly wind or a westerly trough that has moved to the sea, with no role in the formation of the precipitation in Mainland China for inconducive to the intersection of cold and warm air mass.

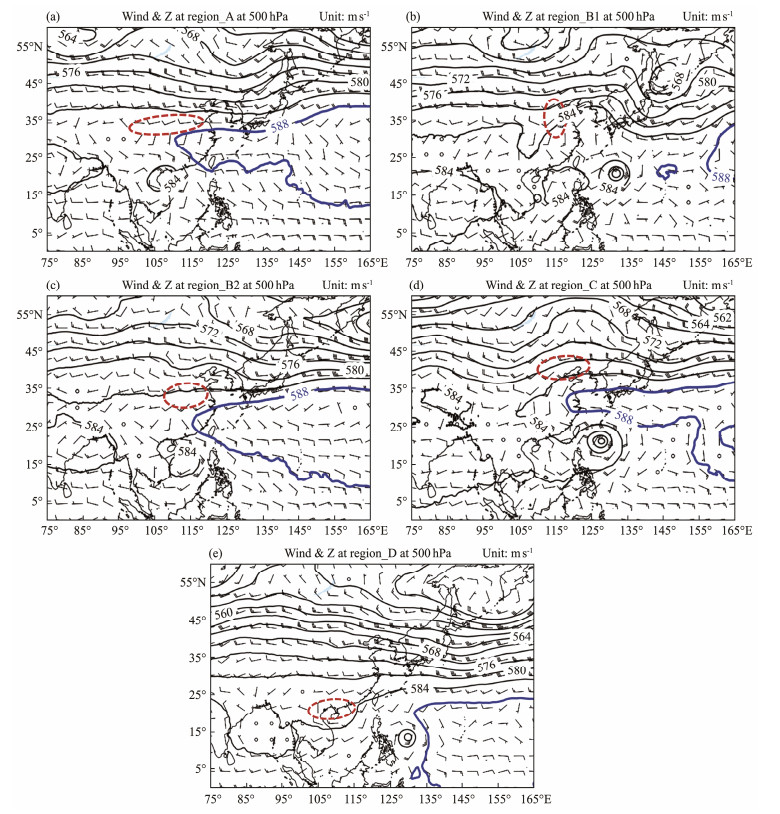

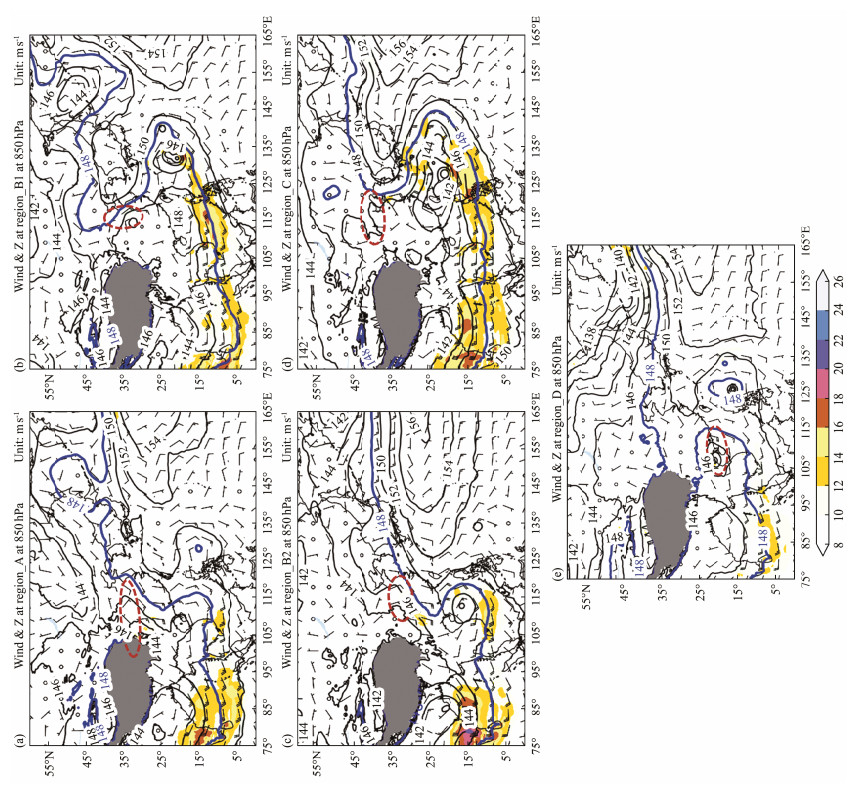

5.3 Synoptic-Scale Analyses at 850 hPaIn the TRP group, a strong subtropical high pressure can also be observed in the lower troposphere (Fig.14). The 148 dagpm line performs a meridional pattern. The TRP related to the westward TCs is located on the northwest of this line. The ridge of 148 dagpm is at approximately 25˚N and 115˚E. The southeast airflow between the TC and the ridge is guided by the subtropical high to transition into southwest airflow and then reach the TRP area.

|

Fig. 14 Composited geopotential height field and wind at 850 hPa. The upper-level jet with wind speed greater than 10 m s−1 is color-shaded. The gray shaded area represents the Tibet Plateau. |

The 148 dagpm ridge in region_B1 and region_C is at approximately 35˚N, and the precipitation area is located on the east or southeast side of the subtropical high ridge. The southeast airflow between the typhoon and the subtropical high transports high-temperature and humid air masses from the sea to the land. In region_D, TC transports water vapor to strengthen the precipitation of the binary TCs or TC residual vortex.

The 148 dagpm line shows a clearer latitudinal pattern in the No_TRP group than the 850 hPa circulation patterns of the TRP group. For westward TCs, the southern region of Huang-Huai in this group is covered by 152 dagpm high, which blocks the connection between TCs and precipitation areas. Water vapor with high temperature and humidity in the ocean cannot be transported to the north through TCs. In addition, downward motion easily appears under the control of high pressure, which resists the precipitation generation.

Significant differences in the low-level jet are observed between the two groups of TCs. In the TRP group, the wind speed in the southwest of the TCs reaches 12 m s−1, which is conducive to transporting water vapor to the vicinity of TCs. In the No_ TRP group, no low-level jet is found in the southwest of the TCs.

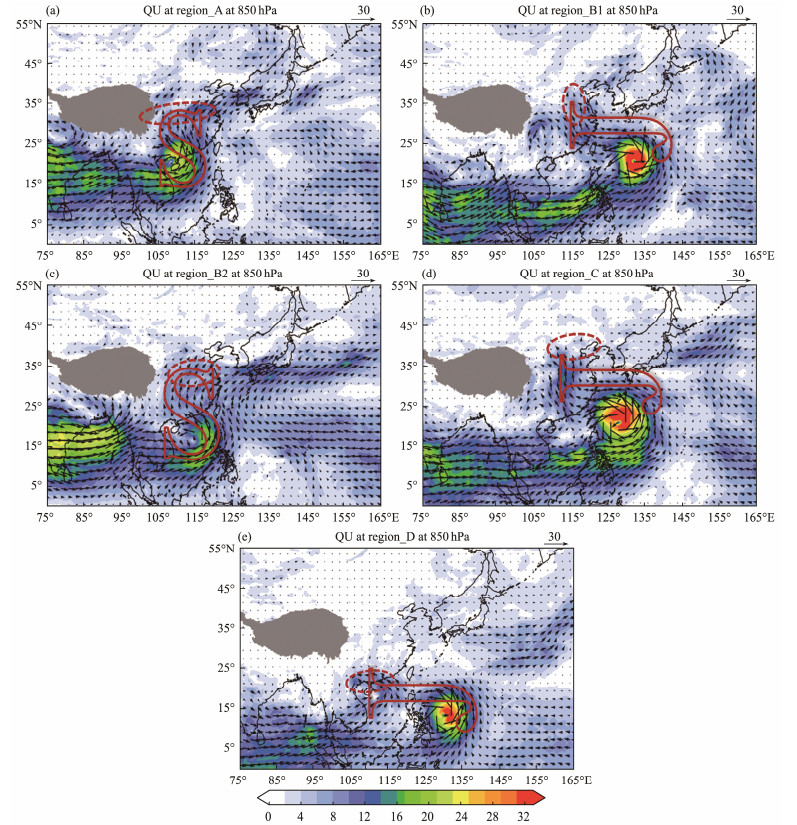

5.4 Water Vapor Transport FeaturesRegion_A (100˚ – 120˚E, 28˚ – 35˚N), region_B1 (113˚ – 123˚E, 30˚ – 40˚N), region_B2 (111˚ – 121˚E, 30˚ – 37˚N), region_C (118˚ – 125˚E, 38˚ – 41˚N), and region_D (109˚ – 121˚E, 18˚ – 25˚N) are selected as the 'box' area in the five regions to study the water vapor budget of each level. On maximum TRP day, the total water vapor transport is positive and mainly on 850 and 925 hPa. After 24 hours, the water vapor budget on the maximum water vapor transport level decreases by approximately 30%. The water vapor of the TRP related to westbound TCs is mostly obtained from the southern boundary. The water vapor sources for northwest-bound TCs are different, causing TRP in different regions.

The water vapor transport at 850 hPa is important. Fig.15 shows the significant differences in water vapor transport between the two groups. The water vapor flux in the southwest of TCs reaches 24 g (cm s hPa) −1. For westward TCs, the water vapor transport in this direction mainly relies on the westward component. After being transported by TCs, influenced by the subtropical high, this water vapor is initially transported to the northwest and then shifted northeast, forming an S-shaped pattern. The TRP is mainly distributed on the high-value area of water vapor transport flux after the transition, performing a strip-like distribution. By contrast, the southwest water vapor transport of northwestward TCs tends toward the meridional pattern compared with that of westward TCs. Then, this water vapor is transported to the northwest by the TC. This type of water vapor transport is classified as a J-shaped pattern causing mass-like distributed TRP. The influence of latitudinal water vapor transport for TRP is greater than that of meridional transport, focusing on the longitudinal and latitudinal water vapor transport separately. Water vapor transport relies more on latitudinal transport, while meridional transport is a bridge connecting middle and low latitudes.

|

Fig. 15 Composited water vapor flux field at 850 hPa (unit: g (cm s hPa) −1). |

The southwest water vapor transport is extremely weak in the No_TRP group. The southeast is the main source of water vapor transported to TCs. The water vapor flux over China of the No_TRP group is significantly weaker than that of the TRP group. In region_A0, the water vapor is contested by another relatively strong TC near Hainan Island instead of transporting northward.

The strong southwest water vapor transport is an important indicator of the TRP formation. The same characteristics are observed in the IVT. An excellent correspondence exists between the TRP and the strongest center of convergence of IVT, featuring more than −6 × 10−4 g (m2 s)−1. The divergence of IVT (

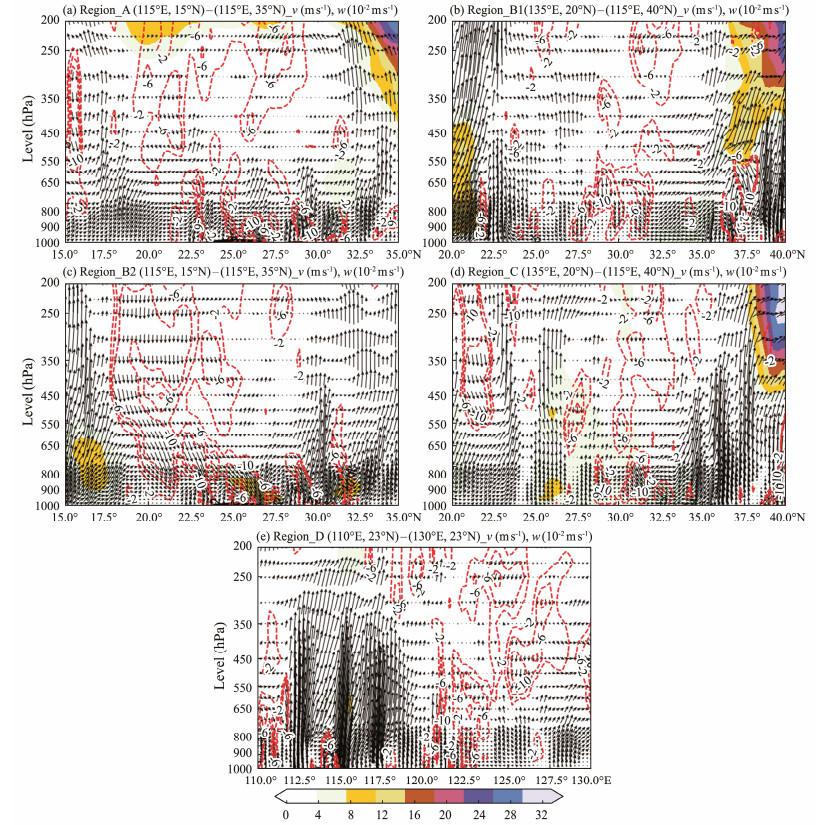

On the vertical cross section near the center of TC to the TRP area (Fig.16), ascent signatures are depicted on both sides, while downward movement is exhibited in the middle. The equivalent potential temperature in the low level of the troposphere is more than 340 K on both sides. In the middle, the low-value center of equivalent potential temperature is approximately 650 hPa. Below 650 hPa, the equivalent potential temperature decreases with altitude, i.e., ∂θe/∂p > 0, MPV1 < 0, forming a convective unstable region. In addition, high values of MPV2 are observed in the low troposphere, with values above 0.13 PVU. The study has shown that the distribution of MPV1 < 0 and MPV2 > 0 in the low troposphere is conducive to the development of precipitation. The vertical movement tilts northwards below 750 hPa. When the TRP is on the eastern coast of China (region_B and region_C), vigorous descent is evident near 25˚ – 30˚N.

|

Fig. 16 Wind on the vertical cross section through the area near the center of TC and the TRP (region_A and region_B2: 115˚E, 15˚ – 35˚N; region_B1 and region_C(135˚E, 20˚N) – (115˚E, 40˚N); region_D (110˚ – 130˚E, 23˚N). The wind vector is the composited horizontal wind (unit: m s−1) and vertical wind (unit: 10−2 m s−1). The red contour dotted line represents the vertical wind (unit: 10−2 m s−1). The color-shaded area indicates the horizontal wind ≥ 10 (unit: m s−1). |

In the No_TRP group, the upper-level jet covers areas above 450 hPa. The downward movement in the north (or west) of TC hinders the release of latent heat and the occurrence of precipitation. The potential temperature in the low level below 320 K. No high-energy tongue and high-humidity tongue, beneficial for triggering convection, are found.

In addition, the upper-level divergence is strong above 5 × 10−5 s−1, with a maximum of more than 13 × 10−5 s−1 in the TRP group, conducive to the development of the vertical movement. At 700 hPa, the potential pseudo-equivalent temperature ranges from 324 K to 332 K in the precipitation area, with a large gradient at the frontogenesis area. This finding indicates that the atmosphere has strong atmospheric baroclinicity. The intersection of cold and warm air triggers frontogenesis and ascent.

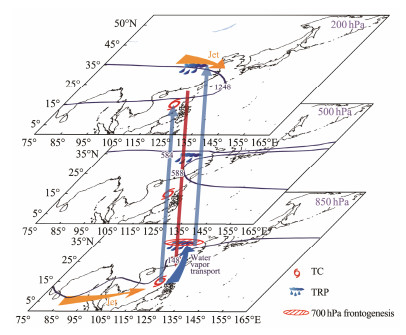

5.6 Key Synoptic-Scale Features of TRPThe typical synoptic-scale features of TRP can be obtained using the methods in this research (Fig.17). At 200 hPa, the 1248 dagpm isoheight line covered most of southern China, with TCs located at the southeast of this line and the TRP positioned in the north of this line. The upper-level jet is located north of the TRP. At 500 hPa, the WPSH is characterized by an east – west belt-shaped distribution. The TRP is located on the northwest of the 588 or 584 dagpm ridge; a south-to-west wind shear is found near the TRP. At 850 hPa, the strong WPSH can also be observed, with a meridional 148 gpm isoheight pattern. The 148 gpm ridge axes extend westward to the TRP vicinity. The low-level jet in the southwest features wind speed values over 12 m s−1. The southwest water vapor transport, which can be transferred further to the TRP area through typhoons at this level, is a key factor for inducing TRP. The two ascending movements near the TC and TRP area are evident in the middle. An acceptable correspondence is found between the 700 hPa frontogenesis zone and the TRP.

|

Fig. 17 Conceptual model of the key synoptic-scale features of the TRP. The dark blue solid contours denote the geopotential heights (1248 dagpm at 200 hPa; 588 and 584 dagpm at 500 hPa; 148 dagpm at 850 hPa). Low-level and upper-level jets are shown with orange arrows. The red vertical and blue vectors represent downward and upward movements, respectively. |

An objective synoptic analysis technique for TRP from station observations, namely, OSAT_TRP, has been developed based on the three criteria, as follows: 1) the precipitation occurs outside the circulation of TCs, 2) the precipitation is affected by TCs, and 3) a gap exists between the TRP and TC rain belt. To distinguish TRP, independent rain belts should be separated, and then those that might relate to TCs' remote effects should be distinguished according to their distance from TCs. Moreover, the TRP with the strong water vapor transport belt should be identified from the TC. The case study and comparison with the TRP from subjective and objective combination methods indicate that the OSAT_TRP can effectively identify TRP even with more than one TC in the Northwest Pacific. The OSAT_TRP is applied to select typical TRPs, and the synoptic-scale environments of the TRP are identified through composite analysis. The results reveal that the configurations of South Asian High, WPSH, and upper-level and low-level jets are important for the TRP occurrence. Southwest water vapor transport is a key factor for inducing TRP, which is positioned in the 700 hPa frontogenesis zone.

However, this method can be further improved. The TRP obtained from OSAT_TRP is compared with that of the subjective and objective combination method, and it is found that after the TC numbering is discontinued, remote precipitation still occurs. This phenomenon can be addressed by extending the track of the historical TCs through the detection of TC residual vortex. In addition, at present, only TRP is objectively recognized for TC daily precipitation, and TRP identification on a more detailed time scale can better explain the characteristics and physical mechanism of TRP. Furthermore, simulation tests through the weather research and forecasting model on representative cases can effectively reveal the physical mechanism of TRP.

Appendix

|

FigureS1 Flowchart of identifying the potential TRP in the OSAT_TRP. Each step and sub step are highlighted with red font. Black font is the detailed steps and the parameters. |

This study was supported by the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (No. KYCX22_1136), the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (No. 42275037), the Basic Research Fund of CAMS (No. 2023Z016), and the Key Laboratory of South China Sea Meteorological Disaster Prevention and Mitigation of Hainan Province (No. SCSF202202). This study was supported by the Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Climate Change.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Fumin Ren, Chenchen Ding and Li Jia. Material preparation, analysis and the draft of themanuscript was written by Li Jia, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Buer, C. L., Zhuge, A. R., Xie, Z. W., Gao, Z. T., and Lin, D. W., 2022. Water vapor transportation features and key synoptic-scale systems of the '7.20' rainstorm in Henan Province in 2021. Chinese Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 46(3): 725-744 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.2202.21226 (  0) 0) |

Chen, L. S., 2006. The evolution on research and operational forecasting techniques of tropical cyclones. Journal of Applied Meteorological Science, 6: 672-681 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Chen, L. S., 2007. Research and forecast of landing tropical cyclone rainstorm. The 14th National Symposium on Tropical Cyclone Science. Chinese Meteorological Society, Shanghai, 3-7 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Cong, C. H., 2011. On the study of the mechanism of tropical cyclone remote precipitation. PhD thesis. Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences.

(  0) 0) |

Cong, C. H., Chen, L. S., Lei, X. T., and Li, Y., 2012. A study on the mechanism of the tropical cyclone remote precipitation. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 70(4): 717-727 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Cote, M. R., 2007. Predecessor rain events in advance of tropical cyclones. Master thesis. University at Albany.

(  0) 0) |

Ding, Y. H., Xi, G. Y., and Li, Y. H., 1987. A synoptic study of the '58·7' persistent rainstorm over the middle Huang (Yellow) River. Scientia Atmospherica Sinica, 1987(1): 100-107 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.1987.01.11 (  0) 0) |

Ding, Z. Y., Zhao, X. H., Rui, X., and Gao, S., 2017. Statistical analysis of summer tropical cyclone remote precipitation events in East Asia from 2000 to 2009 and numerical simulation. Journal of Tropical Meteorology, 23(1): 37-46. DOI:10.16555/j.1006-8775.2017.01.004 (  0) 0) |

Draxler, R. R., and Hess, G. D., 1998. An overview of the HYSPLIT_4 modelling system for trajectories, dispersion, and deposition. Australian Meteorological Magazine, 47: 295-308. (  0) 0) |

Elsberry, R. L., Frank, W. M., and Holland, G. J., 1994. Globalview of Tropical Cyclones. Chen, L. S., et al., Translate. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 444pp.

(  0) 0) |

Galarneau, T. J., Bosart, L. F., and Schumacher, R. S., 2010. Predecessor rain events ahead of tropical cyclones. Monthly Weather Review, 138(8): 3272-3297. DOI:10.1175/2010MWR3243.1 (  0) 0) |

Henny, L., Thorncroft, C. D., and Bosart, L. F., 2022. Changes in large-scale fall extreme precipitation in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast United States, 1979 – 2019. Journal of Climate, 35(20): 6647-6670. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0953.1 (  0) 0) |

Jia, L., Ren, F., McBride, J. L., and Cong, C., 2024. Characteristics and preliminary causes of tropical cyclone remote precipitation over China. Journal of Ocean University of China, 23(4): 45-858. DOI:10.1007/s11802-024-5760-4 (  0) 0) |

Liang, X. D., Xia, R. D., Bao, X. H., Zhang, X., Wang, X. M., Su, A. F., et al., 2022. Preliminary investigation on the extreme rainfall event during July 2021 in Henan Province and its multi-scale processes. Chinese Science Bulletin, 67: 997-1011 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.1360/TB-2021-0827 (  0) 0) |

Lu, X. Q., Yu, H., Ying, M., Zhao, B. K., Zhang, S., Lin, L. M., et al., 2021. Western North Pacific tropical cyclone database created by the China Meteorological Administration. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, 38(4): 690-699. DOI:10.1007/s00376-020-0211-7 (  0) 0) |

Miao, Q. J., Xu, X. D., and Zhang, S. J., 2005. Whole layer water vapor budget of Yangtze River valley and moisture flux components transform in the key areas of the platea. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 63(1): 93-99 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Neiman, P. J., Ralph, F. M., Wick, G. A., Lundquist, J. D., and Dettinger, M. D., 2008. Meteorological characteristics and overland precipitation impacts of atmospheric rivers affecting the west coast of North America based on eight years of SSM/I satellite observations. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 9(1): 22-47. DOI:10.1175/2007JHM855.1 (  0) 0) |

Ran, L. K., Li, S. W., Zhou, Y. S., Yang, S., Ma, S. P., Zhou, K., et al., 2021. Observational analysis of the dynamic, thermal, and water vapor characteristics of the '7.20' extreme rainstorm event in Henan Province. Chinese Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 45(6): 1366-1383 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.2109.21160 (  0) 0) |

Ren, F., Gleason, B., and Easterling, D., 2001. A numerical technique for partitioning cyclone tropical precipitation. Journal of Tropical Meteorology, 2001(3): 308-313 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Ren, F., Wang, Y., Wang, X., and Li, W., 2007. Estimating tropical cyclone precipitation from station observations. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, 24(4): 700-711. DOI:10.1007/s00376-007-0700-y (  0) 0) |

Rutz, J. J., Steenburgh, W. J., and Ralph, F. M., 2014. Climatological characteristics of atmospheric rivers and their inland penetration over the western United States. Monthly Weather Review, 142(2): 905-921. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-13-00168.1 (  0) 0) |

Tang, J. H., Xu, X. D., Cai, W. Y., and Wang, C. Z., 2023. Water vapour multi-vortex structure under the interactions of typhoons and mid-low latitude systems during extreme precipitation in North China. Advances in Climate Change Research, 14(1): 116-125. DOI:10.1016/j.accre.2023.01.006 (  0) 0) |

Tao, S. Y.,, 1980. Heavy Rainfalls in China. Science Press, Beijing, 225pp (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Wang, J., Wu, D., Wang, C. J., Xi, L., and Liu, L., 2022. Analysis on the influence of distance typhoon on the extreme precipitation in July 2021 in Henan. Meteorological and Environmental Sciences, 45(2): 75-85 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.16765/j.cnki.1673-7148.2022.02.008 (  0) 0) |

Wang, Y. M., Ren, F. M., Wang, X. L., Li, W. J., and Shao, D. M., 2006. The study on the objective technique for partitioning tropical cyclone precipitation in China. Meteorological Monthly, 2006(3): 6-10 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Xu, H. X., Xu, X. D., Zhang, S. J., and Fu, Z. K., 2014. Long-range moisture alteration of a typhoon and its impact on Beijing extreme rainfall. Chinese Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 38(3): 537-550 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.1007/s00376-022-2069-3 (  0) 0) |

Yang, H., 2019. Research on the climate characteristics of tropical cyclone precipitation in China from 1960 to 2017. Master thesis. Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences.

(  0) 0) |

Ying, M., Zhang, W., Yu, H., Lu, X. Q., Feng, J. X., Fan, Y. X., et al., 2014. An overview of the China Meteorological Administration tropical cyclone database. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 31(2): 287-301. DOI:10.1175/JTECH-D-12-00119.1 (  0) 0) |

Yu, X. D., 2012. Investigation of Beijing extreme flooding event on July 2012. Meteorological Monthly, 38(11): 1313-1329 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhu, Y., and Newell, R. E., 1998. A proposed algorithm for moisture fluxes from atmospheric rivers. Monthly Weather Review, 126(3): 725-735. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1998)126<0725:APAFMF>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24