2) Chinese Sturgeon Research Institute, China Three Gorges Corporation, Yichang 443100, China;

3) Fisheries College, Jimei University, Xiamen 361021, China;

4) Fishery College, Zhejiang Ocean University, Zhoushan 316004, China

Biodiversity serves as the foundation for human survival and development. Biodiversity indicators are often used as important parameters for ecosystem condition assessment (McQuatters-Gollop et al., 2019). As a result of climate warming, overfishing and anthropocentric impacts, marine ecosystems are changing rapidly, which may negatively impact fish diversity and ecosystem services (Halpern et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2022). Therefore, fish diversity monitoring has become a critical issue for marine conservation and fishery management.

The traditional fishery resources survey largely depends on capture-based census methods (Zou et al., 2020). Species identification based on morphology requires considerable time and taxonomic expertise (Clark et al., 2020). These traditional methods are invasive, expensive, time-consuming and inaccessible to certain areas, making largescale surveys difficult (Fraija-Fernandez et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020b; D'Alessandro and Mariani, 2021; Kim et al., 2022). In addition, different mesh sizes and towing depths can largely affect fish species composition and diversity estimates (Fraija-Fernandez et al., 2020). Therefore, the conventional methods for monitoring fish are inadequate in terms of accommodating the increased spatial and temporal coverage (Yao et al., 2022). Revising the monitoring methods for alternative rapid and effective techniques has potential value, particularly for large-scale areas.

The environmental DNA (eDNA) approach has been popular as a method for detecting genetic materials released into the surrounding environment (Bohmann et al., 2014). Moreover, the eDNA technology offers a sensitive, effective, cost-efficient and minimally invasive method for either specific-species research or biodiversity characterisation (Taberlet et al., 2018). The eDNA metabarcoding approach has been extensively utilised in various communities and ecosystems. For example, the detection of different species communities via eDNA metabarcoding has gained increasing attention, such as fishes (Ahn et al., 2020), zooplankton (Djurhuus et al., 2018) and microbenthic invertebrates (Lobo et al., 2017). Previous studies also showed that eDNA metabarcoding is suitable for various eco-systems, including ponds and lakes (Zhang et al., 2020a), rivers (Shawa et al., 2016), estuaries (Ahn et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2020), coastal waters and the ocean (Fraija-Fernandez et al., 2020). To date, aquatic eDNA has shown great promise as an alternative or complementary monitoring tool in aquatic environments (Hunter et al., 2015).

The East China Sea (ECS) is located at a transition zone between the temperate Yellow Sea and the subtropical South China Sea (Ding et al., 2008), which is amongst the top 10 largest marginal seas of the world (Zhang, 2015). As a result of the combined influence of freshwater runoffs, currents and seasonal upwellings, the ECS is characterised by high levels of species biodiversity and fishery resources (Fan et al., 2014). Additionally, the ECS serves as an essential habitat for commercially valuable resident and migratory fish species at various life cycle stages (Zhang, 2015). However, the fishery resources and biodiversity in the ECS are under threat because of overfishing, habitat loss, pollution and biological invasions (Teh et al., 2020). In previous studies, small study areas such as the estuaries, marine conservation areas or coastal areas were used as research hotspots (Zhang et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). Despite the ecosystem's importance, largescale biodiversity monitoring in the ECS is limited, and several questions remain unanswered, such as the number of fish in the area, differences between horizontal spatial distribution and vertical distribution and differences between nearshore and offshore.

This study aimed to evaluate the potential of eDNA metabarcoding in assessing the fish community composition in the ECS. The analysis of fish diversity will also encompass both horizontal and vertical distributions. Results of this study will provide scientific evidence for fishery resource management and sustainable utilisation in the ECS.

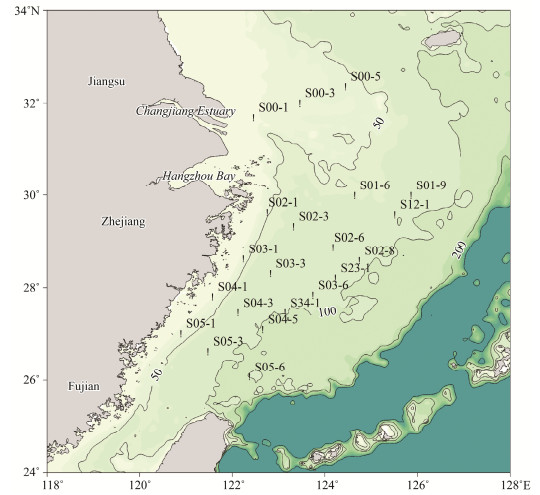

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Field SamplingThe sampling locations and sampling method were mentioned in our previous articles (Wang et al., 2020, 2021, 2022). A total of 178 seawater samples from 44 sampling locations were collected from May 14 to 24, 2019 in the ECS (Fig.1). Specifically, seawater from each depth was kept in a 3.5 L disposable sterile plastic bag before filtering. One liter of each seawater sample was vacuum-filtered through a 47 mm diameter glass fiber with a pore size of 0.45 μm. The filters were wrapped with aluminum foil and stored in a 2 mL cryogenic tube at −196℃ in liquid nitrogen. All filtration equipment was sterilized using sodium hypochlorite, washed with tap freshwater, and rinsed with commercially purified water (Wahaha, China). To improve the detection efficiency and reduce the eDNA metabarcoding costs, 85 samples from 21 stations were selected and sent to Kobe University for eDNA metabarcoding analysis.

|

Fig. 1 Map of sampling stations (black dots) in the East China Sea. Adjacent provinces and municipalities were also illustrated. In the figure, 50, 100 and 200 m isobath were labeled. Samples were divided in different groups: the south-middle-north group (south group: S03-6, S04-1, S04-3, S04-5, S05-1, S05-3, S05-6 and S34-1. middle group: S01-6, S01-9, S02-1, S02-3, S02-6, S02-8, S03-1, S03-3, S12-1 and S23-1. north group: S00-1, S00-3, and S00-5); the east-middle-west group (east group: S00-5, S01-6, S01-9, S02-6, S02-8, S12-1 and S23-1. middle group: S00-1, S00-3, S02-1, S02-3, S03-1, S03-3, S03-6, S04-3, S04-5, S05-6 and S34-1. west group: S04-1, S05-1, and S05-3); and the shallow-middle-deep group (shallow group: S00-1, S00-3, S00-5, S02-1, S03-1, S04-1, and S05-1. middle group: S01-6, S02-3, S02-6, S03-3, S04-3 and S05-3. deep group: S01-9, S02-8, S03-6, S04-5, S05-6, S12-1, S23-1, and S34-1). The base map is sourced from the First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, China. |

During the sampling process, the total depth of the sampling station, sampling depth, temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen and turbidity were also recorded. The specific values of these environmental parameters (i.e., chlorophyll, PO43−, NH4+, SiO32−, NO3− and NO2−) were determined and provided by the First Institute of Oceanography Ministry of Natural Resources (Wang et al., 2021).

2.3 eDNA Extraction, Library Preparation and SequencingThe filters were sent to the Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, Kobe University. eDNA extraction, library preparation and sequencing were conducted as detailed by Wu et al. (2021).

Total eDNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) (Minamoto et al., 2019). After extraction, eDNA was eluted from the DNeasy spin column using 100 μL of Buffer AE and stored at −20℃ before the next step.

Two-round PCR was prepared to construct fish sequencing libraries (Wu et al., 2021). In the first-round PCR, the universal primers MiFish-U targeting the mitochondrial 12S rRNA were used for teleost fish species (Miya et al., 2015). Four replicates of each eDNA samples were conducted to reduce potential bias during the PCR step. In the secondround PCR, Miseq adapter and index sequences to both complication ends were added. The indexed products were equimolar pooled, and the target bands were obtained by electrophoresis. Finally, the prepared library was sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq v2 Reagent kit with 2 × 150 bp PE (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Sterile distilled H2O was used as a negative control for DNA extraction, PCR reaction and Miseq sequencing, and then run in parallel with all eDNA samples to monitor contamination at each step (Wu et al., 2021).

2.4 Bioinformatics and Species VerificationThe data pre-processing and analysis of the MiSeq raw reads were performed with the PMiFish analytical pipeline v2.40 using Usearch v11 (http://github.com/rogotoh/PMi-Fish) (Sato et al., 2018; Miya et al., 2020; Tsuji et al., 2022). Before analysis, the parameters were set in the 'setting.txt', and the default setting was applied except for the sequence identity (≥ 98.5% was used).

The species obtained by the PMiFish pipeline were further verified. Firstly, we checked the original OTU (Operational Taxnomic Units) sequences corresponding to the listed species using the NCBI blast tool (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Secondly, fish species were further verified using FishBase (https://fishbase.se/search.php), the Fish Database of Taiwan (https://fishdb.sinica.edu.tw/), and published books on fish and fisheries resources of the East China Sea: Yamada et al. (2007), Nakabo (2013), Zhao et al. (2016), and Wu and Zhong (2021). The taxonomy was verified using the NCBI taxonomy search tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy). OTUs of fish species that were not previously recorded in the ECS or freshwater fish species were deleted. The tropical and feeding habitats were verified in FishBase and the Fish Database of Taiwan. In addition, the read numbers of species detected in the negative controls were removed from the reads of all the samples (Wu et al., 2021).

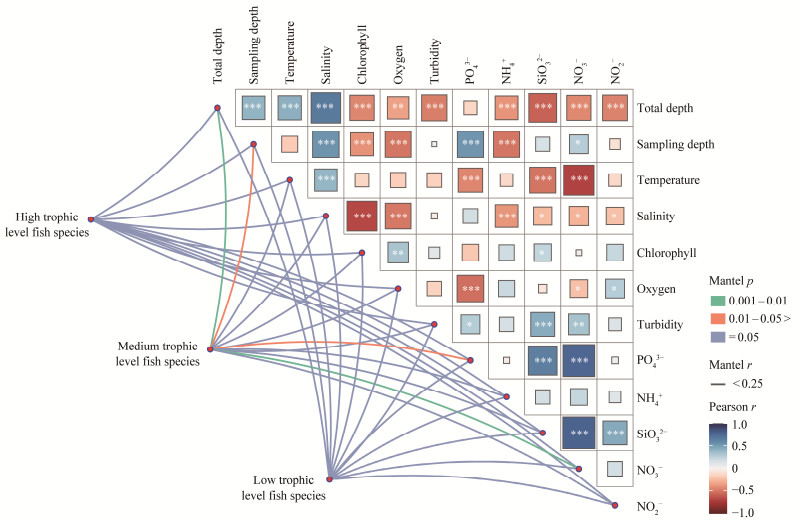

2.5 Statistical AnalysisAll statistical analyses were performed in R software (version 4.2.0). Sampling stations were classified into north-middle-south (NMS), east-middle-west (EMW) and shallow-middle-deep (SMD) considering their sampling locations (longitude and latitude) and isobaths on the horizontal level. Sampling layers were classified into surface-middle-bottom (SMB) considering their sampling depth on the vertical level. When comparing horizontal distribution patterns, all data from each set of vertical samples were combined. And when comparing vertical distributions, data from the same depth group but different horizontal locations were combined. Samples were subsampled to the same depth using 'ggplot2' and 'GUniFrac' packages. Fish diversity indexes amongst different groups were tested using the Wilcox test. The barplot used the 'reshape2', 'tidyverse', 'ggpubr' and 'rstatix' packages. The 'vegan', 'ape' and 'picante' packages were used for diversity indexes analyses. The bubble chart was created using the 'ggplot2' and 'reshape' packages. The Mantel test was conducted using the 'linkET' package to understand the impacts of environmental factors on different trophic-level fish species (https://github.com/Hy4m/linkET). The sampling stations were visualised with ArcGis 10.4.1.

3 Results 3.1 Fish Diversity in the ECSIn total, 6464839 raw reads were generated, in which 5157422 (79.8%) reads were annotated and 4967922 (76.8%) reads were finally retained after species verification. A total of 81 species of fish were detected using eDNA metabarcoding, belonging to 20 orders, 44 families and 72 genera (Table 1).

|

|

Table 1 Fish species were detected using eDNA metabarcoding in the East China Sea |

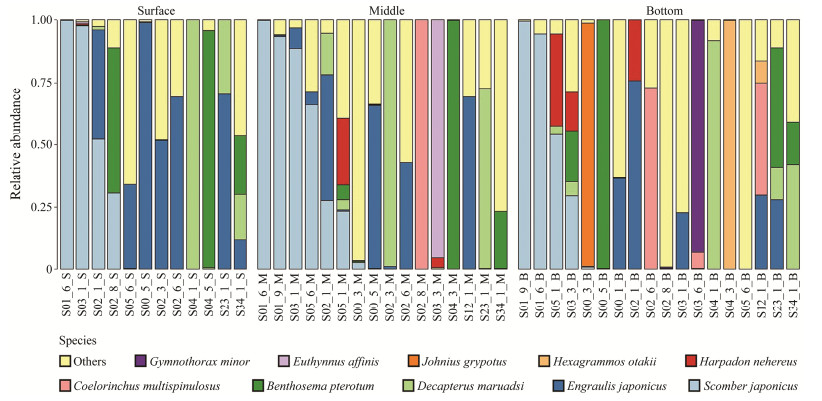

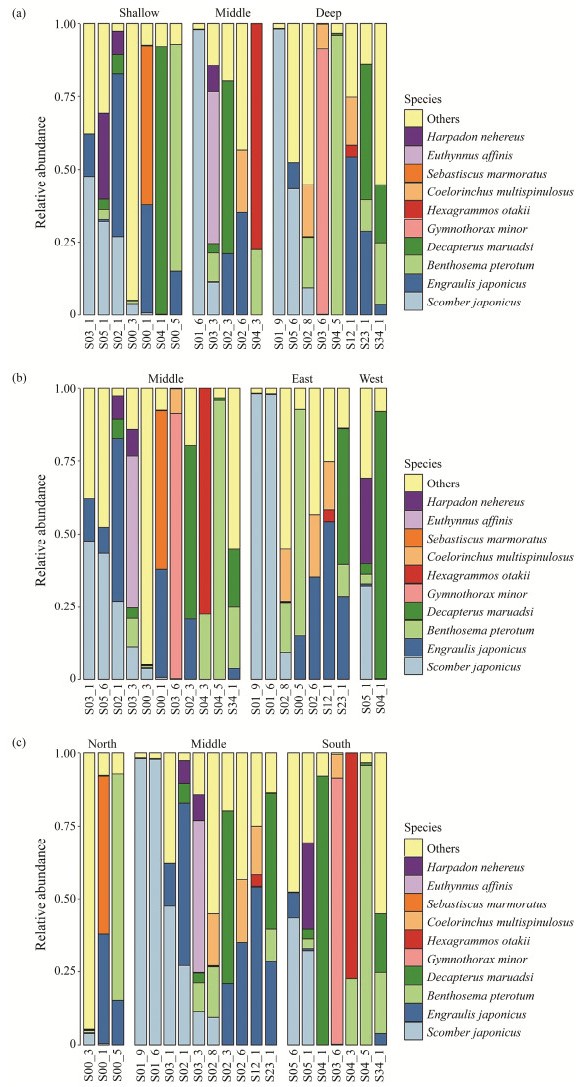

The 10 most dominant fish species were shown in Fig.2 for different sampling layers and Fig.3 for different sampling stations.

|

Fig. 2 Relative abundance of the top ten fish species in different vertical layers. |

|

Fig. 3 Relative abundance of the top ten fish species in different stations. |

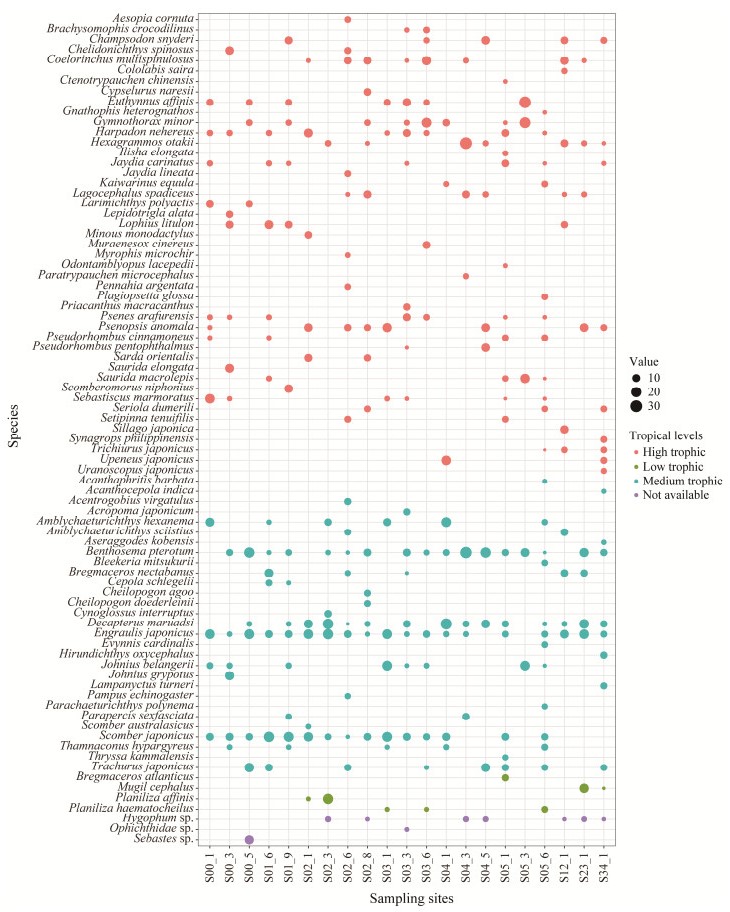

Fish diversity, trophic levels and abundance of each station are illustrated in Fig.4. The fish species richness exhibited spatial heterogeneity across sampling stations. In general, the site with the highest species richness was S05-6, where 24 species were detected. It was followed by S02-6, S03-3 and S05-1, each with 18 fish species detected. The site with the lowest species richness was S05-3, where only five fish species were detected.

|

Fig. 4 Fish diversity and abundance of each fish species monitored using the eDNA approach in the ECS. The bubble size represents the abundance of each fish species. Different colours represent various tropical levels. The trophic levels were classified into 'low trophic' (trophic index ≤ 2.8), 'medium trophic' (2.8 < trophic index < 3.5) and 'high trophic' (trophic index ≥ 3.5) in current study. |

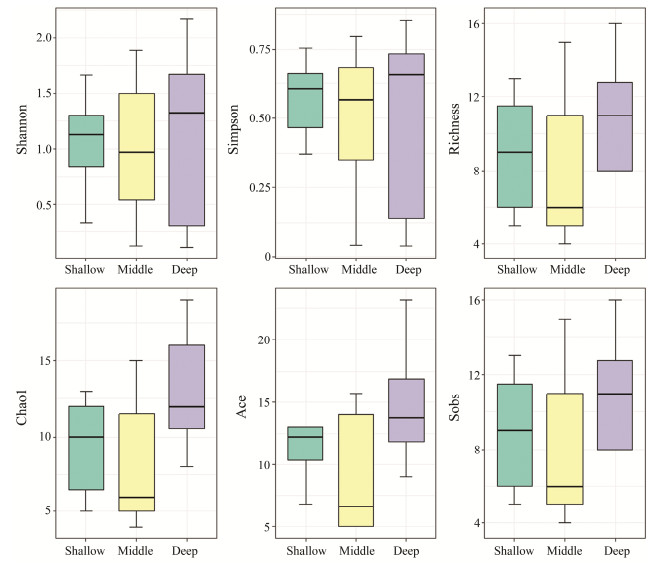

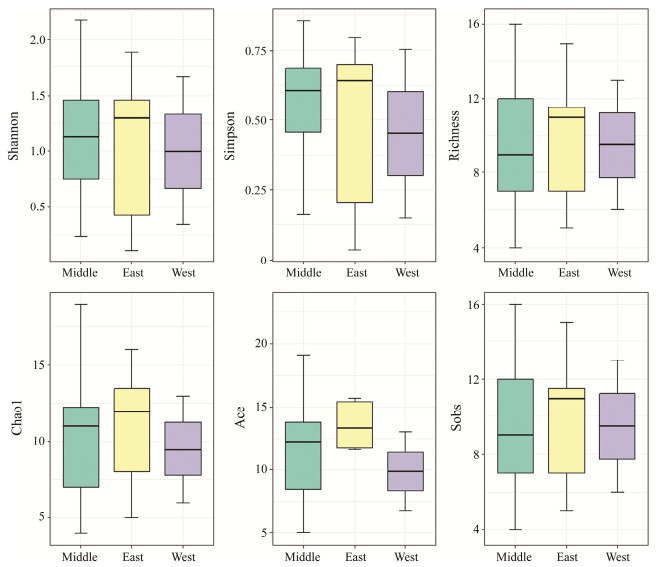

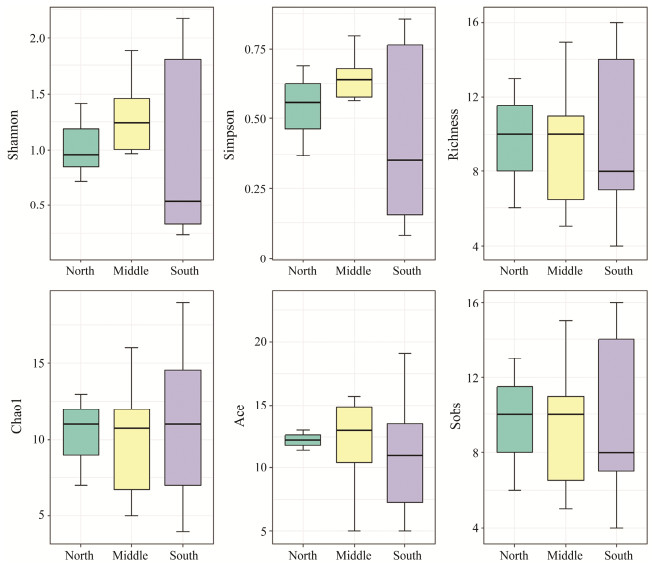

No significant differences were found in fish diversity amongst three horizontal groups, namely, EMW, NMS and SMD. The fish diversity level of East is greater than those of Middle and West in the EMW group. And the fish diversity level of Middle is greater in the NMS and SMD groups (Figs.5 – 7). A total of 18, 15, 16 fish species were shared in the SMD groups, EMW groups, and NMS groups, respectively. Engraulis japonicus was found in 19 stations except for S04-5 and S05-3. Scomber japonicus was detected in 15 stations except for S04-3, S04-5, S05-3, S12-1, S23-1 and S34-1.

|

Fig. 5 Fish diversity indexes among sampling station group. SMD represents shallow water, middle water and deep water. |

|

Fig. 6 Fish diversity indexes among sampling station group. EMW represents east area, middle area and west area. |

|

Fig. 7 Fish diversity indexes among sampling station groups. NMS represents north area, middle area and south area. |

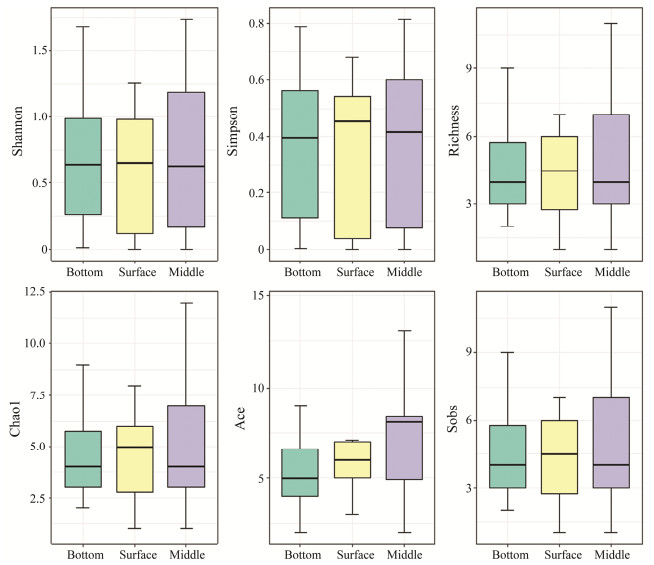

In terms of layers, the highest number of reads was found in S05-6M. Although no significant difference in fish diversity was found in SMB group, higher fish diversity was found in the surface of water (Fig.8). Of all the 81 fish species, 21 fish species were shared by the surface, middle and bottom waters. Seven fish species were only found in the surface water. Twenty three (23) fish species were only found in the middle water. Sixteen (16) fish species were only found in the bottom water. For example, the pelagicfish species Sarda orientalis was only detected in the surface water. The demersal fish species such as Muraenesox cinereus, Acanthaphritis barbata, Priacanthus macracanthus, Uranoscopus japonicus, and Aseraggodes kobensis were only detected in the bottom water.

|

Fig. 8 Fish diversity indexes among different sampling layers. SMB represents surface water, middle water and bottom water. |

The relationships between different trophic levels of fish species and environmental variables are shown in Fig.9. Fish trophic levels were divided as mentioned in Fig.4.

|

Fig. 9 Pairwise correlations of environmental variables and species with different trophic levels were related to each environmental factor by the Mantel test. |

The fish species were divided based on their trophic level, which were high, medium and low. The results indicated a significant correlation only between the species of medium trophic level and those of total depth (P < 0.01), NO2− (P < 0.01), sampling depth (P < 0.05) and turbidity (P < 0.05) of the stations.

4 DiscussionAccurate assessment of fish species diversity and distribution is crucial for effective biodiversity conservation and sustainable management of fishery resources (Yao et al., 2022). The ECS is characterised as a highly productive fishing ground and important spawning, nursing, feeding and overwintering ground for various aquatic species (Zhang, 2015). In several previous studies, the utilisation of multimesh gillnets and environmental DNA metabarcoding revealed significant findings regarding fish diversity and fish assemblage structure within the ECS (Zhang et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). However, all of those studies were limited to the coastal regions and conducted on a small scale within the ECS.

In this study, eDNA metabarcoding was utilised to comprehensively investigate the fish diversity across both horizontal and vertical dimensions on a large scale in the ECS. Despite the absence of significant differences in fish diversity indexes amongst the layers or station groups, a clear trend in fish diversity was observed: east > middle > west, middle > north > south and deep > shallow > middle across the different station levels. The surface water contributed the highest fish diversity indexes amongst the different layers. Although the surface water exhibited the highest fish diversity indexes, not all fish species can be detected in this layer. In this study, S. marmoratus and G. minor were minor demersal fishes that were exclusively observed in the bottom water layer, which may be attributed to their specific habitat requirements. Sciaenops ocellatus has been found to exhibit distribution differences with respect to both station and water layer in the ECS (Wang et al., 2022). Thus, eDNA concentrations and presence/absence data may serve as indicators of the target species' habitat preference. Jeunen et al. (2019) also demonstrated the limited vertical dispersal of eDNA between communities and emphasized the importance of vertical sampling.

Compared with our previous species-specific fish studies using the eDNA approach, Larimichthys polyactis (Wang et al., 2020) and Pampus echinogaster (Zhang et al., 2022a) were detected using eDNA metabarcoding, whereas Larimichthys crocea (Wang et al., 2021), Acanthopagrus schlegelii (Zhang et al., 2022b) and an invasive fish species S. ocellatus (Wang et al., 2022) were not detected in the current study. These results could be attributed to certain factors, such as primer bias and low concentrations of the target species. Therefore, the selection of suitable universal primers or primers specific to some genus is very important in future studies.

In addition, we found that as an increase in sampling size, the richness of fish species obtained is likely to increase. So the spatial differences in fish species abundance obtained in current groups may not necessarily be spatial differences, but may be caused by the size of the water area where the sample is sources. So, we suggest sampling from different water layers and expanding the sampling range can detect different species and obtain more comprehensive information on fish diversity in water bodies in the future eDNA metabarcoding-based researches.

In general, the current study provided support for the use of eDNA in monitoring marine fish species and demonstrated the importance of a spatially focused sampling design, particularly with regard to vertical distribution, for a comprehensive understanding of fish diversity within the research area.

5 ConclusionsThe application of eDNA metabarcoding was proved to be a highly advantageous method for assessing fish diversity within the ECS in this study, especially for the monitoring and assessment of fish diversity in large-scale horizontal and vertical layers. Due to the different water layers with different ecological fish species, more and mixed samples should be collected in deeper water bodies. The aforementioned findings and data have also made contributions to the reliable and sustainable long-term monitoring studies in the ECS.

AcknowledgementsThe eDNA metabarcoding experiment was completed using the Environmental DNA Research Platform of Dr. Toshifumi Minamoto in Kobe University. We would like to thank Dr. Qianqian Wu and Dr. Luhan Wu of Kobe University for conducting the eDNA metabarcoding experiment. This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFD2401903), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41806180), the Science and Technology Project of Zhoushan (No. 2022C41010), the Scientific Research Project of China Three Gorges Corporation (No. WWKY-2020-0079), and the Shared Voyage Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China in the East China Sea (No. NORC2019-02).

Author Contributions

Xiaoyan Wang: investigation, writing original draft, software, validation, data curation. Haobo Zhang: software, validation, data curation. Lanping Zhong: validation, data curation. Yijia Shih: writing-review and editing. Fenfen Ji: writing-review and editing. Tianxiang Gao: experimental design, funding, writing-review and editing.

Data Availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ahn, H., Kume, M., Terashima, Y., Ye, F., Kameyama, S., Miya, M., et al., 2020. Evaluation of fish biodiversity in estuaries using environmental DNA metabarcoding. PLoS One, 15: 15. (  0) 0) |

Bohmann, K., Evans, A., Gilbert, M. T., Carvalho, G. R., Creer, S., Knapp, M., et al., 2014. Environmental DNA for wildlife biology and biodiversity monitoring. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 29: 358-367. (  0) 0) |

Clark, D. E., Pilditch, C. A., Pearman, J. K., Ellis, J. I., and Zaiko, A., 2020. Environmental DNA metabarcoding reveals estuarine benthic community response to nutrient enrichment–Evidence from an in-situ experiment. Environmental Pollution, 267: 115472. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115472 (  0) 0) |

D'Alessandro, S., and Mariani, S., 2021. Sifting environmental DNA metabarcoding data sets for rapid reconstruction of marine food webs. Fish and Fisheries, 22: 822-833. DOI:10.1111/faf.12553 (  0) 0) |

Ding, H., Xu, H., Wu, J., Le Quesne, W. J. F., Sweeting, C. J., and Polunin, N. V. C., 2008. An overview of spatial management and marine protected areas in the East China Sea. Coastal Management, 36: 443-457. DOI:10.1080/08920750802445916 (  0) 0) |

Djurhuus, A., Pitz, K., Sawaya, N. A., Rojas-Marquez, J., Michaud, B., Montes, E., et al., 2018. Evaluation of marine zooplankton community structure through environmental DNA metabarcoding. Limnology and Oceanography Methods, 16: 209-221. DOI:10.1002/lom3.10237 (  0) 0) |

Fan, Y., Lan, J., Li, H., Cao, Y., Zhao, Z., Wang, J., et al., 2014. Use of lipid biomarkers for identification of regional sources and dechlorination characteristics of polychlorinated biphenyls in the East China Sea. Science of the Total Environment, 490: 766-775. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.054 (  0) 0) |

Fraija-Fernandez, N., Bouquieaux, M. C., Rey, A., Mendibil, I., Cotano, U., Irigoien, X., et al., 2020. Marine water environmental DNA metabarcoding provides a comprehensive fish diversity assessment and reveals spatial patterns in a large oceanic area. Ecology and Evolution, 10: 7560-7584. DOI:10.1002/ece3.6482 (  0) 0) |

Halpern, B. S., Frazier, M., Potapenko, J., Casey, K. S., Koenig, K., Longo, C., et al., 2015. Spatial and temporal changes in cumulative human impacts on the world's ocean. Nature Communications, 6: 7615. DOI:10.1038/ncomms8615 (  0) 0) |

Kim, E. B., Sagong, H., Lee, J. H., Kim, G., Kwon, D. H., Kim, Y., et al., 2022. Environmental DNA metabarcoding analysis of fish assemblages and phytoplankton communities in a furrowed seabed area caused by aggregate mining. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9: 788380. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2022.788380 (  0) 0) |

Lobo, J., Shokralla, S., Costa, M. H., Hajibabaei, M., and Costa, F. O., 2017. DNA metabarcoding for high-throughput monitoring of estuarine macrobenthic communities. Scientific Reports, 7: 15618. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-15823-6 (  0) 0) |

McQuatters-Gollop, A., Mitchell, I., Vina-Herbon, C., Bedford, J., Addison, P. F. E., Lynam, C. P., et al., 2019. From science to evidence – How biodiversity indicators can be used for effective marine conservation policy and management. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6: 109. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2019.00109 (  0) 0) |

Minamoto, T., Hayami, K., Sakata, M., and Imamura, A., 2019. Real-time PCR assays for environmental DNA detection of three salmonid fish in Hokkaido, Japan: Application to winter surveys. Ecological Research, 34: 237-242. DOI:10.1111/1440-1703.1018 (  0) 0) |

Miya, M., Gotoh, R. O., and Sado, T., 2020. MiFish metabarcoding: A high-throughput approach for simultaneous detection of multiple fish species from environmental DNA and other samples. Fisheries Science, 86: 939-970. DOI:10.1007/s12562-020-01461-x (  0) 0) |

Miya, M., Sato, Y., Fukunaga, T., Sado, T., Poulsen, J. Y., Sato, K., et al., 2015. MiFish, a set of universal PCR primers for metabarcoding environmental DNA from fishes: Detection of more than 230 subtropical marine species. Royal Society Open Science, 2: 150088. DOI:10.1098/rsos.150088 (  0) 0) |

Nakabo, T., 2013. Fishes of Japan: With Pictorial Keys to the Species. Tokai University Press, Tokyo, 1747pp.

(  0) 0) |

Sato, Y., Miya, M., Fukunaga, T., Sado, T., and Iwasaki, W., 2018. MitoFish and MiFish pipeline: A mitochondrial genome data-base of fish with an analysis pipeline for environmental DNA metabarcoding. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35: 1553-1555. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msy074 (  0) 0) |

Shawa, J. L. A., Clarke, L. J., Wedderburn, S. D., Barnes, T. C., Weyrich, L. S., and Cooper, A., 2016. Comparison of environmental DNA metabarcoding and survey methods in a river system. Biological Conservation, 197: 131-138. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.03.010 (  0) 0) |

Taberlet, P., Bonin, A., Zinger, L., and Coissac, E., 2018. Environmental DNA: For Biodiversity Research and Monitoring. Oxford University Press, New York, 253pp.

(  0) 0) |

Teh, L. S. L., Cashion, T., Cheung, W. W. L., and Sumaila, U. R., 2020. Taking stock: A large marine ecosystem perspective of socio-economic and ecological trends in East China Sea fisheries. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 30: 269-292. DOI:10.1007/s11160-020-09599-8 (  0) 0) |

Tsuji, S., Inui, R., Nakao, R., Miyazono, S., Saito, M., Kono, T., et al., 2022. Quantitative environmental DNA metabarcoding reflects quantitative capture data of fish community obtained by electrical shocker. Scientific Report, 12: 21524. DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-25274-3 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X., Lu, G., Zhao, L., Du, X., and Gao, T., 2021. Assessment of fishery resources using environmental DNA: The large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) in the East China Sea. Fisheries Research, 235: 105813. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2020.105813 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X., Lu, G., Zhao, L., Yang, Q., and Gao, T., 2020. Assessment of fishery resources using environmental DNA: Small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) in East China Sea. PLoS One, 15: e0244495. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0244495 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X., Zhang, H., Lu, G., and Gao, T., 2022. Detection of an invasive species through an environmental DNA approach: The example of the red drum Sciaenops ocellatus in the East China Sea. Science of the Total Environment, 815: 152865. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152865 (  0) 0) |

Wu, H., and Zhong, J., 2021. Key to Marine and Estuarial Fishes of China. China Agriculture Press, Beijing, 1437pp.

(  0) 0) |

Wu, Q., Sakata, M. K., Wu, D., Yamanaka, H., and Minamoto, T., 2021. Application of environmental DNA metabarcoding in a lake with extensive algal blooms. Limnology, 22: 363-370. DOI:10.1007/s10201-021-00663-1 (  0) 0) |

Yamada, U., Tokimura, M., Horikawa, H., and Nakabo, T., 2007. Fishes and Fisheries of the East China and Yellow Seas. Tokai University Press, Tokyo, 1262pp.

(  0) 0) |

Yao, M., Zhang, S., Lu, Q., Chen, X., Zhang, S., Kong, Y., et al., 2022. Fishing for fish environmental DNA: Ecological applications, methodological considerations, surveying designs, and ways forward. Molecular Ecology, 31: 5132-5164. DOI:10.1111/mec.16659 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, H., Li, Y., Zhong, L., Gao, T., and Wang, X., 2022a. Using environmental DNA method to clarify the distribution of Pampus echinogaster in the East China Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9: 992377. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2022.992377 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, H., Zhou, Y., Zhang, H., Gao, T., and Wang, X., 2022b. Fishery resource monitoring of the East China Sea via environmental DNA approach: A case study using black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii). Frontiers in Marine Science, 9: 848950. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2022.848950 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, J., 2015. Ecological Continuum from the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Watersheds to the East China Sea Continental Margin. Springer, Cham, 201pp.

(  0) 0) |

Zhang, S., Lu, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Zhao, J., and Yao, M., 2020a. Assessment of fish communities using environmental DNA: Effect of spatial sampling design in lentic systems of different sizes. Molecular Ecology Resources, 20: 242-255. DOI:10.1111/1755-0998.13105 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y., Pavlovska, M., Stoica, E., Prekrasna, I., Yang, J., Slobodnik, J., et al., 2020b. Holistic pelagic biodiversity monitoring of the Black Sea via eDNA metabarcoding approach: From bacteria to marine mammals. Environment International, 135: 105307. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2019.105307 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, K., Gaines, S. D., García Molinos, J., Zhang, M., and Xu, J., 2022. Climate change and fishing are pulling the functional diversity of the world's largest marine fisheries to opposite extremes. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 31: 1616-1629. DOI:10.1111/geb.13534 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, S., Xu, H., Zhong, J., and Chen, J., 2016. Zhejiang Marine Ichthyology. Zhejiang Science and Technology Press, Hangzhou, 1065pp.

(  0) 0) |

Zou, K., Chen, J., Ruan, H., Li, Z., Guo, W., Li, M., et al., 2020. eDNA metabarcoding as a promising conservation tool for monitoring fish diversity in a coastal wetland of the Pearl River Estuary compared to bottom trawling. Science of the Total Environment, 702: 134704. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134704 (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24