2) Shandong Province Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China

Storm surge is the abnormal increase and decrease of water levels caused by severe atmospheric disturbances, such as sudden air pressure changes or strong winds, and is one of the most dangerous natural disasters. Typhoons are one of the major factors causing storm surges (Zhang and Sheng, 2015). China is one of the principal countries affected by storm surges and experiences an average of nine typhoons per year. The significant influence of climate change and sea level rise have increased the hazards caused by extreme weather events, such as typhoons, storm surges, and floods in coastal cities. Xiamen is located on the southeast coast of Fujian Province, close to the Taiwan Strait, an area frequented by typhoons. According to the statistical analysis of storm surge data at the Xiamen station from 1959 – 2012, water level rise of more than 50 cm from typhoons along the coast of Xiamen occurred 145 times – approximately 2.7 times per year. The impact of extremely high water levels caused by storm surges is serious. Thus, accurate risk assessment in this regard is particularly important.

The extreme high water level caused by storm surges has a serious impact on the Xiamen area. It is particularly necessary to accurately predict the extreme water level and assess its risks. The methods for predicting and analyzing extreme high water levels are mainly divided into two types. The first type is frequency analysis method. The advantage of this type is that it has a small amount of calculation and is easy to verify. The common frequency analysis methods include Gumbel, Weibull and GEV (Generalized Extreme Value), etc. (Hou, 1993; Vogel et al., 1993; Walton, 2000; Sobey, 2005; Huang et al., 2008; Fan, 2017). It is found that this type of method is applicable to the Pacific area, and researchers have achieved a lot of achievements in the coastal areas of China Seas (Dong et al., 2008; Zhu and Li, 2011; Wang et al., 2016). However, this type of method requires a long time sequence of water level data, and the calculation result is limited to a single point. The second type is numerical model method. This method is generally carried out without long-term water level data, and use meteorological factors and astronomical tides as the driving factors for numerical simulations. The common numerical models include empirical simulation technique (EST) or Joint probability method (JPM) etc. (Samuels and Burt, 2002; Pirazzoli and Tomasin, 2007; Toro et al., 2010). Numerical model methods consume more computing resources and rely on typhoon parameter settings for modeling, so the accuracy is limited by typhoon data. The extreme water level data have been used to analyze storm surge risk based on the frequency analysis method. That is to estimate the possibility of storm surges with different severities in a certain area in the future, which is mainly used to reflect the long-term characteristics of storm surge risks (Shi et al., 2013). Many scholars have conducted some researches on the characteristics of the storm surge or the risk caused by extreme water levels in Xiamen (Jiang et al., 2000; Yuan et al., 2018).

However, the above studies did not consider the effects of special typhoons and sea level rises in the future. The contribution of astronomical tides to extreme water levels is analyzed and the time and magnitude of water level rise between two typhoon storm surges or two astronomical tides are estimated by using hourly water level data in Xiamen from 1960 – 2019 in this paper. The Gumbel method was used to calculate the water level return period, and the risk assessment was conducted under the following conditions: no sea level rise, linear sea level rise, and nonlinear sea level rise.

2 Characteristics Analysis of Water Levels 2.1 Statistical CharacteristicsThe observations at the Xiamen station provided the tide data for this work. The Xiamen station, located at Gulangyu (Fig.1), is a part of the China Ocean Observation Network. The dataset was obtained from the National Marine Data and Information Service.

|

Fig. 1 Location of Xiamen station and the tracking path of 10 typhoons. The track of typhoon Vongfong (2014) is beyond the domain but its extreme water level is 730 cm. |

This dataset contains 60 years of tidal data from 1960 –2019 with hourly observation intervals, good data quality, few interruptions, and integrity greater than 99.9%. Total potential error for tide data is estimated to be at 5 cm (Peter, 2017). Astronomical tide and tidal constituent data were obtained from the T_TIDE package (Pawlowicz et al., 2002), the storm surge level data were obtained by subtracting the astronomical tides from the total water levels. The analysis of tidal observations yields the tidal amplitudes and phases at a set of discrete frequencies, which represent the different tidal constituents (Doodson, 1921, 1928). The M2 stands for the lunar-based semi-diurnal tidal constituent, K1 stands for the lunar-solar declination diurnal tidal constituent, and O1 stands for the lunar declination diurnal tidal constituent.

The ratio of K1 + O1 constituent to M2 constituent is 0.33, showing normal semi-diurnal characteristics, meaning that there are two high and low tides in each lunar day (24 h and 50 min), and the time interval between two adjacent high and low tides is approximately 12 h and 25 min. Harmonic analysis shows that the maximum astronomical tide, minimum astronomical tide, average maximum high water, average high water, and maximum astronomical tide surge (tide height relative to average water level) are 710, 29, 580, 569, and 350 cm, respectively (Table 1).

|

|

Table 1 Basic parameters of astronomical tides, extreme water levels and typical typhoons at Xiamen station, based on the zero-point water level in Xiamen |

Fig.2 shows observed tidal and astronomical tide data through harmonic analysis. The root mean square error is 19 cm, and the agreement index (AI) – an index that characterizes the degree of agreement between observation and simulated data – is 99.58%. Values close to 1 denote the good simulation effect and 99.58% of the agreement degree show that the astronomical and observation tides are perfectly matched. The root mean square error is approximately four times of the maximum error (5 cm), meaning that the difference between the total water levels and astronomical tide levels is significant. The difference is the residual of the water level, which involves meteorological water level increase and sea level rise.

|

Fig. 2 The time series of total water levels and astronomical tides from January 1, 1960 and to December 31, 2019. |

Xiamen experiences an average of 2.7 typhoons annually, and storm surges primarily occur from July to October, especially in August and September. Although tsunamis, extratropical cyclones, and cold waves can cause water level rise, this study only addresses water level rise caused by typhoons – the primary cause of extreme water level rise.

Typhoon Herb (1996) caused the highest water levels in the history of Xiamen, followed by typhoon Dujuan (2015). The storm surges caused by these two typhoons were much higher than those caused by other typhoons. Herb, the 8th typhoon in 1996, formed in the eastern Guam Island on July 23, 1996, became a typhoon in two days, gradually strengthened as it moved west-northwest, made landfall in Taiwan on July 31, and weakened to a tropical storm with a maximum wind speed of 45 m s−1 in the center. The tropical storm strengthened into a typhoon after crossing the Taiwan Strait and made landfall in the Fujian Province. Extremely high tides appeared along the coast of Fujian owing to the astronomical high tide and the funneling effect. Dujuan (2015), the 21st typhoon of 2015, formed in the northeastern Guam Ocean on September 21, 2015 and became a typhoon on September 25, with a maximum wind speed of 55 m s−1 in the center. Dujuan made landfall in Taiwan on September 28, crossed into the Taiwan Strait the next day, and made landfall in Fujian. Omar (1992), Dan (1999), Meranti (2016), and other typhoons also caused the extreme rises in the sea levels as shown in Fig.1.

Vongfong (2014) did not affect Xiamen directly but caused a high water level of 732 cm because of the combined influence of the typhoon periphery and cold air. Meranti (2016), the most devastating recent typhoon – made direct landfall in Xiamen with maximum winds of 52 m s−1, and caused widespread damages. Eleven typhoons caused the water levels higher than the highest astronomical tide as shown in Table 1. Of the 11 typhoons selected in this study, Vongfong (2014), Dan (1999), and Haima (2016) occurred in October, and eight occurred from July to September. Xiamen experiences the astronomical spring tide in September and therefore even small water elevation changes can be disastrous. Fig.3 shows Xiamen station tidal data for five days during typhoons Omar (1992), Herb (1996), Dan (1999), Dujuan (2015), and Meranti (2016).

|

Fig. 3 Five-day water level data for typhoons Herb (time zero is 01:00 July 30, 1996), Dujuan (time zero is 00:00 September 27, 2015), Omar (time zero is 01:00 August 28, 1992), Dan (time zero is 12:00 October 7, 1999), and Meranti (time zero is 01:00 September 16, 2016). (a), total water levels; (b), astronomical tides; (c), storm surges. |

Extreme tides are linked to storm surge, astronomical tide, and tide time. The overlap of storm surge and high tide causes extremely high tides. Xiamen station is in a semi-diurnal tidal sea, and the tidal period includes semi-diurnal (12.42 h), daily (24.84 h) and spring-neap periods (14.77 d), and semi-annual (182.62 d), annual (365.25 d), and nodal cycles (18.61 yr).

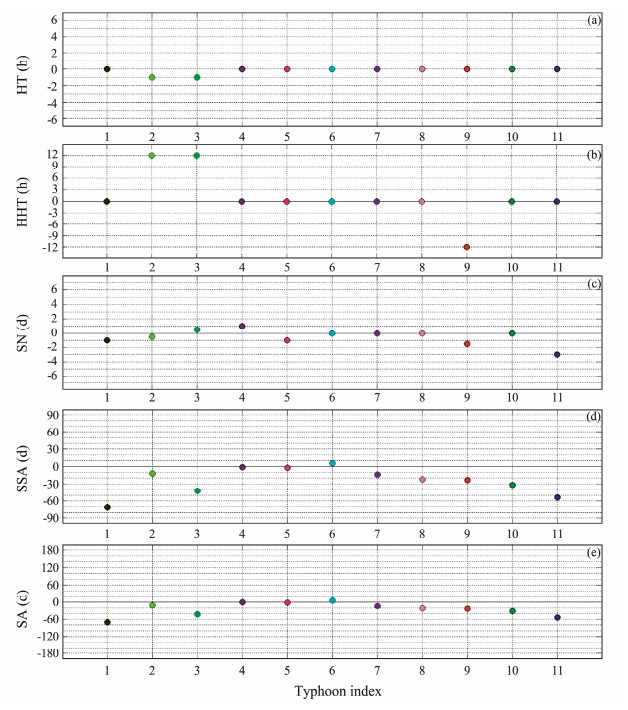

Fig.4 shows the time intervals of each extreme water level relative to the highest astronomical tide. Nine out of 11 extreme water levels coincided with high tides; typhoons 2 and 3 arrived 1 h before high tides. Typhoons 2 and 3 occurred 12 h after maximum high tides, and typhoon 9 occurred 12 h before the maximum high tide. Typhoons 6, 7, 8, and 10 coincided with the spring tide periods; other typhoons arrived within 2 h before or after the spring tide periods, except typhoon 11, which occurred 3 h before. Typhoon Haima arrived 6 days after the high-level time in semi-annual cycle and the remaining typhoons occurred before the onset of the cycle (1 – 2 d in the case of typhoons 4 and 5).

|

Fig. 4 Extreme water level times of 11 typhoons related to the time of highest astronomical tides. Zero represents the time of the highest astronomical tides; negative and positive values indicate before and after astronomical tides, respectively. (a), high tide (HT); (b), higher high tide (HHT); (c), spring-neap tidal period (SN); (d), semi-annual cycle (SSA); (e), annual cycle (SA). |

Fig.5 shows the sea level increase at the time of highest tide and the proportion of astronomical tide. The average astronomical tide was 309 cm, and the average proportion was 83.9%. Herb (1996) had the highest storm surge elevation of 115 cm and the astronomical tide accounted for 71.2% of total water level elevation. Typhoon 11 Winnie (1997) had a water elevation of 87 cm, in which the astronomical tide accounted for 75.2%. Typhoon 6 had the lowest water increase of 18 cm and the astronomical tide accounted for 95.0%. The astronomical tide accounted for more than 90% of total water level during typhoons 6, 8 and 10. Assuming that typhoon Herb (1996) occurs during the highest astronomical tide, the highest water level will be 825 cm, which is equivalent to a return period of more than 1000 yr.

|

Fig. 5 The height of maximum surges and astronomical tides, and the proportion of astronomical tide in actual sea levels during 11 typhoons. The astronomical tide is relative to the zero point of the tide. |

The Gumbel distribution is a common method for calculating the return period of marine meteorological and physical oceanographic elements and is often used to calculate high (low) water levels at different return periods (Wang and Jia, 1987; Hou, 1993; Qian et al., 2019). The Code of Hydrology for Sea Harbour (hereinafter referred to as the Code) of China stipulated that the Gumbel distribution should be used for water level frequency distribution curves. The Code suggests that other model curves, such as the lognormal, Weibull, and generalized extreme value (GEV) distributions can be selected according to the best fitting empirical accumulation frequency principle and the theoretical model. Three distribution curves including Gumbel, Weibull and GEV methods are shown in Fig.6. The fit of the three distribution models is good when the return period is less than 8 yr. The Weibull distribution curve gets worse with the increase of the return period. The GEV distribution curve fits not very well when the return period exceeds 20 yr. The Gumbel distribution curve is the best fit to the observed water levels and is finally chosen for the estimation.

|

Fig. 6 Annual observed extreme water levels and different probability distribution curves to fit the water level variation during a return period. |

The probability distribution function of extreme water levels can be expressed as the following cumulative distribution function (Fisher and Tippett, 1928):

| $ F(x) = \exp \left\{ { - {{\left[ {1 + \xi \left({\frac{{x - \mu }}{\sigma }} \right)} \right]}^{ - \frac{1}{\xi }}}} \right\} \text{,} $ | (1) |

where μ is the position parameter, σ is the scale parameter, and ξ is the shape parameter.

The corresponding probability density function is:

| $ f(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma }{\left[ {1 + \xi \left({\frac{{x - \mu }}{\sigma }} \right)} \right]^{ - \frac{1}{\xi } - 1}}\exp \left\{ { - {{\left[ {1 + \xi \left({\frac{{x - \mu }}{\sigma }} \right)} \right]}^{ - \frac{1}{\xi }}}} \right\} . $ | (2) |

The value of ξ determines the tail shape of the distribution; ξ = 0 denotes type-I extremum or Gumbel distributions.

Annual extreme water level data from 1960 – 2019 were sorted in descending order, and the Gumbel probability density distribution function was used to fit the 60-year extreme water level data as shown in Fig.7. Extreme water levels with the 10-yr, 25-yr, 50-yr, and 100-yr return periods were calculated and compared with observed extreme water levels and astronomical tides as shown in Table 1. Extreme water levels caused by Herb (1996) and Dujuan (2015) were much higher than those caused by other typhoons. The Gumbel distribution, which was calculated without involving the data of typhoons, can be considered as the background to study the impact of these typhoons on Xiamen.

|

Fig. 7 The relative water levels and return periods of eleven storm surge events. |

The 11 typhoons can be divided into three grades according to the extreme tides and water levels of the return periods. Herb (1996) and Dujuan (2015) were in the first grade with water levels of 760 and 759 cm that corresponded to 76 and 71 yr, respectively, according to the Gumbel curve. There were four second-grade typhoons with return periods from 10 – 25 yr. The remaining five typhoons had return periods of fewer than 10 yr. Meranti (2016), a third grade storm, caused serious damages in Xiamen with an extreme tidal level of 715 cm.

3.2 Sea Level RiseThe 60-yr tendency of sea level change was calculated by using the harmonic analysis results. Linear and quadratic nonlinear fittings were performed after anomaly changes to obtain linear and nonlinear sea level change tendencies, respectively.

The fitting formula are:

| $ y = 0.0255x - 6.6252, $ | (3) |

| $ y = 2.2 \times {10^{ - 6}}{x^2} + 0.0243x - 6.4815, $ | (4) |

where Eq. (3) is the linear fitting formula, and Eq. (4) is the nonlinear fitting formula, x is the month, and y is sea level change (cm). According to the linear fitting formula, the sea level is rising at a rate of 0.306 cm per year. The nonlinear fitting formula indicates the accelerating sea level rise.

According to the fitting results, linear and nonlinear sea level rise in the next 10, 25, 50, and 100 yr will be 3.06 and 3.33 cm, 7.65 and 8.45 cm, 15.30 and 17.30 cm, 30.60 and 36.19 cm, respectively. The nonlinear sea level rise of 36.19 cm will be a very large value considering the highest astronomical tide elevation of 350 cm.

The fifth IPCC report indicates that the rate of global sea level rise has been accelerating since the 20th century, by 1.7 mm yr−1 from 1901 – 2010 and 3.4 mm yr−1 from 1993 – 2016 (Wuebbles et al., 2017). Coastal sea levels in China rose by 3.2 and 3.8 mm yr−1 from 1980 – 2016 and 1993 – 2016, respectively. They are more than the average global sea level rise of 3.3 mm yr−1 in the same period (Wang et al., 2018). In this work we estimate the linear and nonlinear sea level rise rates are of 3.1 and 3.3 – 3.6 mm yr−1, respectively. The values approximately agree with those reported in previous researches (Han and Huang, 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011; Zuo et al., 2012).

Then, in 100 yr, the highest sea levels involving the linear and nonlinear sea level rise factors are estimated to be 795.2 and 800.8 cm, respectively, and correspond to a return period of approximately 1000 yr according to the current Gumbel curve. Without the strong influence of typhoons Herb (1996) and Dujuan (2015), about 5.8 – 11.1 cm water level decrease will occur in the 10 – 100-yr return period (Fig.8).

|

Fig. 8 The sea levels in 10-, 25-, 50-, and 100-yr return periods when typhoons and global sea level rise were involved. |

Hazard risk is the probability that a disastrous event occurs within a certain period. The formula for hazard risk in this paper is as following:

| $ R = 1 - {(1 - p)^n}, $ | (5) |

where R is the risk probability, p is the probability of event occurrence, and n is the number of years. The sea levels under the four situations with return periods of 10-, 25-, 50-, and 100-yr were converted into the corresponding p values according to the Gumbel distribution curve, as shown in Fig.7. n values are taken from 0 to 1000, and then the R-value distribution curves can be obtained (Fig.9). The red, blue, dot, and black lines denote the four cases. The linear and nonlinear trends were applied to the estimation with and without Herb and Dujuan, respectively. The greater the number of assessed factors is and the higher the sea level is, the lower the risk probability for a given year is. For example, when the sea levels in a 10-yr return period without and with Herb and Dujuan are 721.9 and 734.7 cm, the corresponding R-values are 0.78 and 0.65, respectively. Thus, the probabilities of the sea level reaching 721.9 and 734.7 cm within a 10-yr return period are 78% and 65%, respectively. This means that the hazard risk will increase if we exclude the influence of Herb and Dujuan in coastal engineering projects. The red line in Fig.9 represents the situation with Herb and Dujuan (also the situation for the Gumbel curve in Fig.7). The probability of this risk at the corresponding time of the return period is 63% – 65%.

|

Fig. 9 Forecasted hazard risk curves when the return period is 10 (a), 25 (b), 50 (c), and 100 (d) yr. |

The differences between the curves and the horizontal axis and between the two curves are the total and relative risk degrees, respectively. The differences between the curves gradually increase as the return period increases. Without Herb and Dujuan, the risk probability will significantly increase, and the total risk degree will increase relatively with the increase of the return period. The risk probability for the 10-yr return period increases by a maximum of 13.4%, and the total risk degree within 10 yr increases by 26.8%. The risk probability for the 25-yr return period increases by a maximum of 18.4%, and the total risk degrees within 10 and 25 yr increase by 52.2% and 72.7%, respectively. The risk probability for the 50-yr return period increases by a maximum of 22.1%, and the total risk degrees within 10, 25, and 50 yr increase by 74.0%, 62.0%, and 47.1%, respectively. The risk probability for the 100- yr return period increases by a maximum of 25.2%, and the total risk degrees in 10, 25, 50, and 100 yr increase by 94.3%, 85.4%, 72.9%, and 54.4%, respectively.

The risk probability and total risk degrees are significantly reduced when the influence of sea level rise is considered. For return periods of less than 50 yr, the risk probability of predicted water levels according to the linear trend is reduced by a maximum of 5.4% – 48.4%. The prediction based on the nonlinear trend for a 100-year return period decreases the risk probability by 56.9%. The total risk decreases by 3.1% for the 10-yr return period and by 75.4% and 69.7% within 10 and 100 yr for the 100-yr period, respectively. For the nonlinear trend, the value increases 77.5% within 100 yr.

4 ConclusionsIn this study the extreme water levels are predicted and the risks are assessment at Xiamen station based on 60- year observation data. The interaction of astronomical tide and storm surge has been analyzed and the results show that typhoons Herb (1996) and Dujuan (2015) had the greatest impact on the distribution of extreme water levels. For the 100-yr return period, the total risk within 10, 25, 50, and 100 yr increases by 94.3%, 85.4%, 72.9%, and 54.4%, respectively. The simultaneous occurrence of Herb (1996) or Dujuan (2015) with the maximum astronomical tide would raise tidal levels by 800 cm, which is exceed the 1000-year return period.

The average annual sea levels in Xiamen rose by 3.3 – 3.6 mm yr−1 from 1960 – 2019 and the rate of sea level rise is still increasing. Relative sea level rise in the next 10, 25, 50, and 100 yr are predicted to be 3.33, 8.45, 17.3, and 36.19 cm respectively. For a return period of fewer than 50 yr, the predictions when the linear sea level rise is considered get a lower risk probability, whereas the nonlinear trend is much more important for the 100-yr return period. The risk probability and risk degree are reduced maximally by 56.9% and 77.5%, respectively, over 100 yr when non-linear trend is applied.

AcknowledgementsThis study is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC140 1103), the NSFC-Shandong Joint Foundation (No. U1706 226), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51779236), and the Open Fund of Shandong Province Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering (No. kloe201903).

Dong, J. X., Zhang, T. Y., and Fu, X.. 2008. Calculation of the storm surges in the Shacheng Bay in Fujian Province in 100 years return periods. Marine Science Bulletin, 27: 9-16. (  0) 0) |

Doodson, A. T.. 1921. The harmonic development of the tide-generating potential. Geophysical Journal Royal Astronomical Society, 100: 305-329. (  0) 0) |

Doodson, A. T.. 1928. The analysis of tidal observations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 227: 223-279. (  0) 0) |

Fan, L. L., and Wang, Y. Y.. 2017. Parameter estimation and case analysis of based on generalized extreme value distribution. Journal of Capital Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 38(3): 13-17 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Fisher, R. A., and Tippett, L. H. C.. 1928. Limittimg forms of the frequency distribution of the largest or smaHest member of a sample. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 24: 180-190. DOI:10.1017/S0305004100015681 (  0) 0) |

Han, G., and Huang, W.. 2008. Pacific decadal oscillation and sea level variability in the Bohai, Yellow, and East China Seas. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 38: 2772-2783. DOI:10.1175/2008JPO3885.1 (  0) 0) |

Hou, R. K.. 1993. Calculating the annual maximum water level using the Gumbel extreme value distribution. Marine Science Bulletin, 3: 126-129. (  0) 0) |

Huang, W. R., Xu, S. D., and Nnaji, S.. 2008. Evaluation of GEV model for frequency analysis of annual maximum water levels in the coast of United States. Ocean Engineering, 35(11-12): 1132-1147. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2008.04.010 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, Y. W., Wu, P. M., and Xu, J. D.. 2000. A model with interaction of tide and surge for Xiamen Harbor. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 22: 1-6. (  0) 0) |

Liu, X., Liu, Y., Guo, L., Rong, Z. R., Gu, Y. Z., and Liu, Y. H.. 2010. Interannual changes of sea level in the two regions of East China Sea and different responses to ENSO. Global and Planetary Change, 72: 215-226. DOI:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2010.04.009 (  0) 0) |

Pawlowicz, R., Beardsley, B., and Lentz, S.. 2002. Classical tidal harmonic analysis including error estimates in MATLAB using T-TIDE. Computers and Geosciences, 28(8): 929-937. DOI:10.1016/S0098-3004(02)00013-4 (  0) 0) |

Peter, B.. 2017. Tide-surge historical assessment of extreme water levels for the St. Johns River:1928 – 2017. Journal of Hydrology, 553: 624-636. (  0) 0) |

Pirazzoli, P. A. , and Tomasin, A.. 2007. Estimation of return periods for extreme sea levels: A simplified empirical correction of the joint probabilities method with examples from the French Atlantic coast and three ports in the southwest of the UK. Ocean Dynamics, 57(2): 91-107. DOI:10.1007/s10236-006-0096-8 (  0) 0) |

Qian, L. X., Wang, H. R., Zhang, R., and Jiao, Z. Q.. 2019. Gumbel extreme hydrological frequency analysis model in situations of insufficient data. Advanced Engineering Sciences, 51(5): 41-48 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Samuels, P. G. , and Burt, N.. 2002. A new joint probability appraisal of flood risk, proceedings of the institution of civil engineers. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers–Water, Maritime and Energy, 154(2): 109-115. DOI:10.1680/wame.2002.154.2.109 (  0) 0) |

Shi, X. W., Tan, J., Guo, Z. X., and Liu, Q. Z.. 2013. A review of risk assessment of storm surge disaster. Advances in Earth Science, 28(8): 866-874 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Sobey, R. J.. 2005. Extreme low and high water levels. Coastal Engineering, 52(1): 63-77. DOI:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2004.09.003 (  0) 0) |

Toro, G. R., Resio, D. T., Divoky, D., Niedoroda, A. W., and Reed, C.. 2010. Efficient joint-probability methods for hurricane surge frequency analysis. Ocean Engineering, 37: 125-134. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2009.09.004 (  0) 0) |

Vogel, R. M., Tomas, W. J., and Mcmahon, T. A.. 1993. Floodflow frequency model selection in southwestern United States. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management, 119: 353-366. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(1993)119:3(353) (  0) 0) |

Walton, T. L. J.. 2000. Distributions for storm surge extremes. Ocean Engineering, 27: 1279-1293. DOI:10.1016/S0029-8018(99)00052-9 (  0) 0) |

Wang, H., Fan, W. J., Zhang, J. L., and Mu, L.. 2011. The characteristics of sea level changes along the coast of China in recent 31 years. Marine Science Bulletin, 30(6): 637-643 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Wang, H., Liu, K. X., Fan, W. J., Feng, J. L., Wang, G. S., Zhang, J. L., et al.. 2018. Aanalysis on the sea level anomaly high of 2016 in China coastal area. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 40(2): 43-52 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Wang, J., and Jia, S. D.. 1987. A program for extreme value analysis by using the Gumbel method. Marine Science Bulletin, 6: 87-91. (  0) 0) |

Wang, Y. J., Zhang, R., Qian, L. X., Ge, S. S., and Wang, F.. 2016. Model for probabilistic risk assessment in extreme high water level caused by rising sea level and its application – A case study in Ningbo. Journal of Catastrophology, 31(1): 213-218 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Wuebbles, D. J., Fahey, D. W., Hibbard, K. A., Dokken, D. J., Stewart, B. C., and Maycock, T. K.. 2017. Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume 1. Marine Research Press, Washington, D. C., 470pp.

(  0) 0) |

Yuan, F. C., Wu, X. R., and Lu, J. F.. 2018. Statistical characteristics of storm surges in central and southern Fujian coast. Marine Forecasts, 35: 68-75 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhang, H., and Sheng, J.. 2015. Examination of extreme sea levels due to storm surges and tides over the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Continental Shelf Research, 93: 81-97. DOI:10.1016/j.csr.2014.12.001 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, Y. M., and Li, Z. L.. 2011. Sea level variation and the effect to water level extreme distribution estimate in South China. Transactions of Oceanology and Limnology, 4: 126-133 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zuo, J., He, Q., and Chen, C.. 2012. Sea level variability in East China Sea and its response to ENSO. Water Science and Engineering, 5: 164-174. (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21