2) Key Laboratory of Submarine Geosciences and Prospecting Techniques, MOE, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China

The Bohai Sea is a semi-enclosed shelf sea surrounded by the mainland and in contact with the Yellow Sea through the Bohai Strait, thereby rendering the Bohai Strait – the only channel for sediment transport out of the Bohai Sea. The Bohai Sea has received a large number of river sediments, especially from the Yellow River that delivers about 1.10 billion tons of sediments every year (Milliman and Meade, 1983), 80% of which were mainly delivered into the Bohai Sea during the summer flood season (Bi et al., 2011). Due to the weak hydrodynamics, sediments are captured in the estuary by the stratification and sheer front (Li et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2007), 70% of which are deposited within 30 km of the estuary (Martin et al., 1993). Sediments are mainly transported out of the Bohai Sea in the form of suspended particles, and the annual suspended sediment flux (SSF) from the Bohai Sea to the Yellow Sea can reach millions of tons according to previous studies (Bornhold et al., 1986; Martin et al., 1993; Bi et al., 2011). Hence, the study of suspended sediment transport through the Bohai Strait is of great significance to the ecological environment, physicochemical cycle and sediment source in the Bohai and Yellow Sea (Lin et al., 2002; Qiao, 2008; Wang et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2015).

Numerous studies have investigated the suspended sediment transport through the Bohai Strait. Qin et al. (1986) first proposed that suspended sediment transport through the Bohai Strait follows the pattern of moving outward from the south, and inward from the north, whereby suspended sediments are delivered into the Bohai Sea from the north and out from the south under the prevailing northwest winds in winter. This trend has been confirmed through observation and numerical simulation by oceanographers (Huang et al., 1996; Fang et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2011). Recent studies have focused on winter or seasonal transports in the Bohai Strait. Bi et al. (2011) examined the seasonal variation of suspended sediment concentrations of the Yellow and Bohai Seas and calculated the suspended sediment flux through the Bohai Strait as 40 Mt based on multi-sites investigation and satellite images. Extreme weather conditions in winter also have important impacts on the sediment transport (Wu et al., 2019; Duan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Wang et al. (2020) restored the response processes of the circulation systems and the sediment transport patterns to the north wind through in-situ observations and numerical modeling simulations. They also clarified the contributions of various mechanisms to the sediment transport. Meanwhile, Wu et al. (2019) presented a novel, phaseaveraging method to estimate the net suspended sediment fluxes and found a net westward sediment transport into the Bohai Sea in result of intermittent but frequent southerly winds in northerly-wind dominated winters. However, due to the weak hydrodynamics in summer and the influence of numerous islands in the Bohai Strait, the trends and dynamic mechanisms of the suspended sediment transport of the Bohai and Yellow Sea in summer remain controversial. Zhao et al. (1995) proposed that the tidal residual currents are the main hydrodynamic force in summer using the numerical simulation in the Bohai and Yellow Sea. This finding was confirmed a posteriori truth by other studies (Huang et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2003). The total tidal flux of the Bohai strait is nearly 1.2×1011 m3, of which the tidal flux of the Laotieshan channel accouts for about 68% (Jiang et al., 2019). As for the transport trends, Zhang et al. (2018) observed that waters of the Bohai Sea flow to the Yellow Sea through the northern and southern surface layers of the Bohai Strait in summer and revealed the sediment transport into the Yellow Sea by analyzing sea-level changes.

Most previous investigations mainly focused on the seasonal variations and the sediment transport under the extreme weather in winter, but few on the short time scale in summer, especially under the influence of residual currents (Li et al., 2015). Hence, this study provided an analysis of the temporal and spatial variations of currents and suspended sediment concentrations in the Bohai Strait in summer. Tidal currents and suspended sediment concentrations were observed synchronously at 11 stations in the Bohai Strait, lasting for 25 h. The transport mechanism, trend and flux of suspended sediments in summer are then examined by using the flux mechanism decomposition method and numerical simulations. The results of this study are expected to be important to help better understand the underlying mechanism of sediment transport in Bohai Strait under the strong residual currents associated with the tidal fluctuations in Summer.

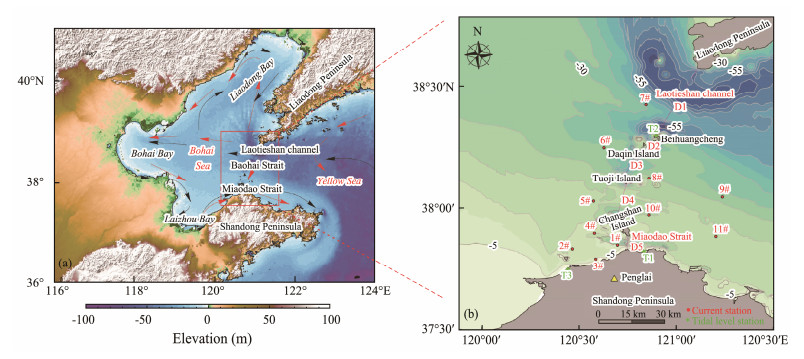

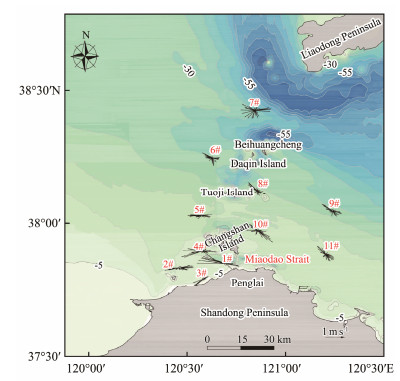

2 Study AreaThe Bohai Strait, which is located on the south of Laotieshan of Liaodong Peninsula and the north of Penglai of Shandong Peninsula (Fig.1), has the shortest length of only 109 km. The islands in the central of the Bohai Strait divide it into three distinct parts: the south, the central and the north parts (Fig.1). In the south is the Miaodao Strait (Fig.1; D5), which has a shallow depth of nearly 20 m and a width of 6.4 km. It is the main channel for the sediment transport from the Bohai Sea to the muddy area of the Yellow Sea (Bi et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014). The central part, south from Changshan island and north to Beihuangcheng (Fig.1; D4 – D2), are densely distributed by islands with complex waterways and circulations. In the north, the Laotieshan Channel (Fig.1; D1) possesses the widest width of 42 km, which occupies 2/5 of the entire Strait. It is the main channel of warm waters in the Yellow Sea to enter the Bohai Sea (Qiao, 2008). Due to the strong scour of tidal currents, there are tidal ditches with depth of exceeding 60 – 80 m in the south of the Laotieshan channel (Qin et al., 1986), which makes it the widest and deepest channel of the Bohai Strait.

|

Fig. 1 Location and stations of study area in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea. (a), the red arrows represent the summer circulations (Fang et al., 2000); the black arrows represent the winter circulations (Guan, 1994). (b), red dots indicate current stations; green dots indicate tidal stations; D1 section, Laotieshan channel; D2 section, Daqindao to Beihuangcheng Channel; D3 section, Tuoji to Daqindao channel; D4 section, Changshan to Tuoji channel; D5 section, Miaodao Strait. |

Eleven continuous observational stations were set in the Bohai Strait on August 3, 2016 (Fig.1). The observational time was extended from 10:00 on August 3 to 10:00 on August 4, with a one-hour interval. GPS positioning was used in all the stations, while electromagnetic current meter (model: JEF AEM213-D; accuracy: ± 1 cm s−1) and Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (model: FlowQuest 600 kHz; velocity accuracy: ± 2.0 mm s−1) were used to measure tidal currents. Stations with electromagnetic current meters were observed in six layers (surface layer, 0.2 H, 0.4 H, 0.6 H, 0.8 H and bottom layer) divided according to the water depth. Simultaneous tidal level observations were conducted at Beihuangcheng, Penglai western harbor and Gangluan wharf (Fig.1).

Suspended sediments were taken synchronously along with the currents measurement, whereby at station 6#, 7#, 8# and 9# water samples were taken in three layers, while at the other stations samples were taken in six layers. Subsequently, the suspended sediment concentrations (SSC) at each time were derived by laboratory filtration, drying, weighing and calibration of the water samples. Meanwhile, the calibrations were made once every 10 measurements by using double filters: the upper measured the suspended sediment concentrations, and the bottom made the correction. The measurement error did not exceed 10%. The formula is as follows:

| $ SSC = \frac{{{W_a} - {W_m} - {W_r}}}{V}, $ | (1) |

where Wa is the total weight of the filtration membranes and samples, Wm is the weight of the air filtration membrane, and Wr is the blank correction value which can be calculated by the following formula:

| $ {W_r} = \frac{1}{i}\sum\nolimits_1^i {\left({{W_{b(i)}} - {W_{f(i)}}} \right)}, $ | (2) |

where Wb is the weight of the blank corrected filtration membrane after filtration, Wf is the weight of the blank corrected filtration membrane before filtration, and i is the number of blank corrected filtration membranes.

3.2 Flux Mechanism Decomposition MethodThe flux mechanism decomposition method (FMDM) is a reliable method to study suspended sediment flux at a local and global scale (Bowden, 1964; Zhu et al., 2005) and has been widely used to examine the suspended sediment transport in Estuaries and shelves (Jay et al., 1997; Hu, 2009). In this investigation, the single-width FMDM was used to analyze the suspended sediment transport and the impact of various dynamic factors in the study area. The method is not only able to reflect the advection transport of suspended sediments but also can better show the role of vertical shear transport and tidal pump transport.

Ingram (1981) and Uncles et al. (1985) proposed the use of relative water depth to decompose instantaneous mass transport, which uses z (0 ≤ z ≤ 1) to represent the relative water depth and x to express ordinate. The instantaneous velocity (u (x, z, t)) can be divided into the sum of the mean value of the vertical line and its partial terms excluding the fluctuations of velocity.

| $ u(x, z, t) = \bar u + u' . $ | (3) |

| $ \bar u = {\bar u_0} + {\bar u_t}, {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} u' = {u'_0} + {u'_t} . $ | (4) |

The instantaneous velocity can be decomposed as follows:

| $ u(x, z, t) = {\bar u_0} + {\bar u_t} + {u'_0} + {u'_t}, $ | (5) |

where,

Similarly, the sediment concentrations can also be decomposed as follows:

| $ c(x, z, t) = {\bar c_0} + {\bar c_t} + {c'_0} + {c'_t} . $ | (6) |

The formula for calculating the average instantaneous single-width suspended sediment flux in tidal period is expressed as follows:

| $ T = \frac{1}{{{T_t}}}\int\limits_0^{{T_t}} {\int\limits_0^h {uc{\text{d}}{z_0}} } {\text{d}}t = \frac{1}{T}\int\limits_0^{{T_t}} {\int\limits_0^1 {uch{\text{d}}z{\text{d}}t} } = {h_0}{\bar u_0}{\bar c_0} + \left\langle {{h_t}{{\bar u}_t}} \right\rangle {\bar c_0} + \left\langle {{h_t}{{\bar c}_t}} \right\rangle {\bar u_0} + \left\langle {{h_t}{{\bar u}_t}{{\bar c}_t}} \right\rangle + {h_0}\overline {{{u'}_0}} \overline {{{c'}_0}} + \left\langle {{h_t}{{u'}_0}{{c'}_0}} \right\rangle + \left\langle {{h_t}{{u'}_{}}_t{{c'}_0}_{}} \right\rangle + \left\langle {{h_t}{{u'}_t}{{c'}_t}} \right\rangle \\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ = ({{\text{T}}_1}) + ({{\text{T}}_2}) + ({{\text{T}}_3}) + ({{\text{T}}_4}) + ({{\text{T}}_5}) + ({{\text{T}}_6}) + ({{\text{T}}_7}) + ({{\text{T}}_8}), $ | (7) |

where T1 represents the Euler residual current contribution, T2 represents the Stokes draft contribution, T3 represents the related terms of tide and suspended sediment variation, T4 represents the relevant terms of suspended sediment and tidal current change, T5 represents the relevant terms of vertical velocity change and SSC change, T6 and T7 represents the shear diffusion caused by mean volume and tidal vibration shear, T8 represents the vertical tidal oscillation shear.

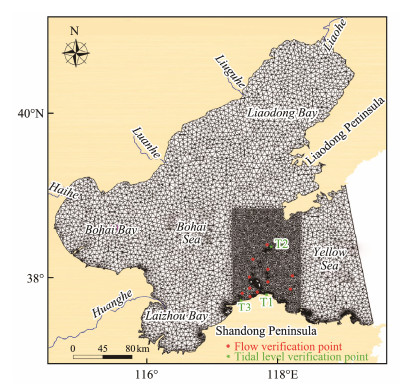

3.3 Numerical Simulation of Tidal Currents 3.3.1 Model descriptionMike 3 unstructured fluid model was used to develop a numerical simulation model of Hydro Dynamic (HD) module to simulate the tidal current field. The model used unstructured triangular meshes, which were flexible enough to fit the land-sea boundary well, and could be controlled according to the need to divide the computational domain. The model has been effectively applied in oceans, shelves and estuaries (Huang et al., 2013; Fairley et al., 2015; Qiao et al., 2016). Mike 3 is based on the Boussinesq hypothesis, which is derived from the three-dimensional incompressible RANS equation (Reynolds averaged Navies-Stokes), as well as the hydrostatic hypothesis. The free surface in the 3-D model is defined by using σ coordinate transformation method. In addition, the spatial range is subdivided into continuous non-overlapping elements by finite element method. In this model, unstructured grids were used horizontally, while structural grids were used vertically. Five layers were set to reflect the tidal current from surface to bottom, with a respective value of 0.2 evenly set for each layer. This computational domain included the sea area surrounded by A (Jiming Island in Shandong Province), B (Dengsha River in Liaoning Province) and the coastline (Fig.2). Then, based on the observation data of A and B, the four main tidal component harmonic constants M2, S2, K1 and O1 were calculated.

| $ \varsigma {\text{ = }}\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^N {\left[ {{H_i}\cos ({\sigma _i}t - {G_i})} \right]}, $ | (8) |

|

Fig. 2 Model calculation domain and grids. |

where

The bed roughness is controlled by Manning's coefficient n (n = 32 m1/3 s−1 for bottom friction), and the dimensionless empirical Smagorinsky coefficient is set as 0.28. Moreover, the horizontal eddy viscosity coefficient is calculated by the Smagorinsky formula considering the subscale grid effect, and the expression is as follows:

| $ A = c_s^2{l^2}\sqrt {2{S_{ij}}{S_{ij}}}, $ | (9) |

where A is the horizontal eddy-viscosity coefficient, cs is constant and l is the characteristic mixing length, Sij is deformation rate, which is calculated by

| $ {S_{ij}} = \frac{1}{2}\left({\frac{{\partial {u_i}}}{{\partial {u_j}}} + \frac{{\partial {u_j}}}{{\partial {u_i}}}} \right), {\text{ }}i, j = 1, 2. $ |

In order to reveal the tidal current situation of the study area, the simulation grids of the Bohai Strait have been partially densified. The simulation time was set to 61 days from July 15 to September 15, 2016, and the paper selects the data of whole August to calculate the residual tidal current and suspended sediment flux.

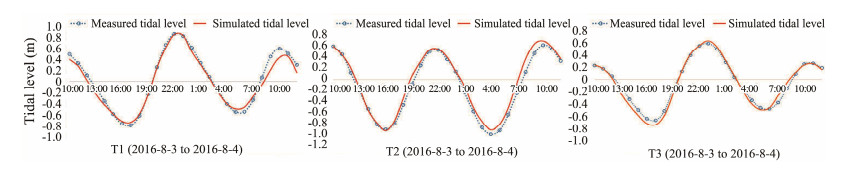

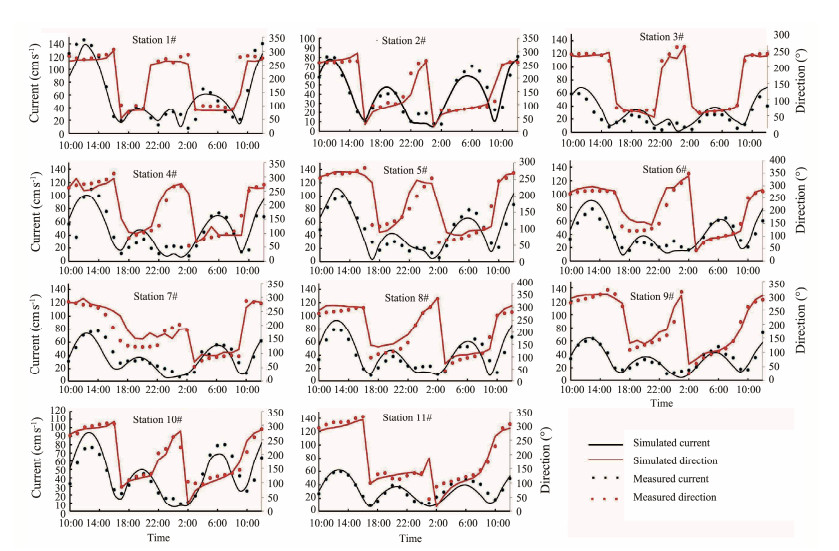

3.3.2 Model validationThe simulated tidal data were validated by the measured data from August 3 to August 4 in 2016 at Penglai western harbor (T1), Beihuangcheng (T2) and Gangluan wharf (T3) (Fig.3). The absolute differences of the highest tidal level vary from 0.01 m to 0.08 m, and the average difference is 0.05 m; the relative differences vary from 1.64% to 12.54%, with an average relative difference of 7.36%. The absolute differences of the lowest tide level vary from 0.06 to 0.07 m, and the average difference is 0.07 m; the relative differences vary from 7.21% to 12.30%, with an average relative difference of 9.31% (Table 1). The simulated tidal level is essentially consistent with the measurements. Moreover, the results showed the current features simulated with the numerical model agreed very well with the observation data recorded at the 11-station data (Fig.4). In most cases, the simulated tidal currents are also in good agreement with the measured data for all the stations. Nonetheless, slight differences remain at certain times between the measured and the simulated tidal current velocities, with a maximum mismatch of around 0.16 m s−1. This discrepancy may be because the changes of currents induced by wind and wave variations are not considered in the simulation. In short, the numerical simulation results remain reliable and be used to explore the suspended sediment transport subjected to residual currents under summer tidal fluctuations.

|

Fig. 3 Comparison of simulated and measured water levels. |

|

|

Table 1 Comparison of simulated and measured tidal level values |

|

Fig. 4 Comparison of simulated and measured currents. |

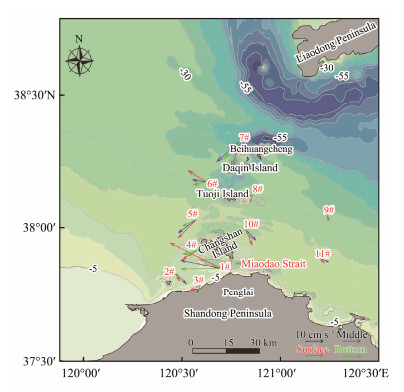

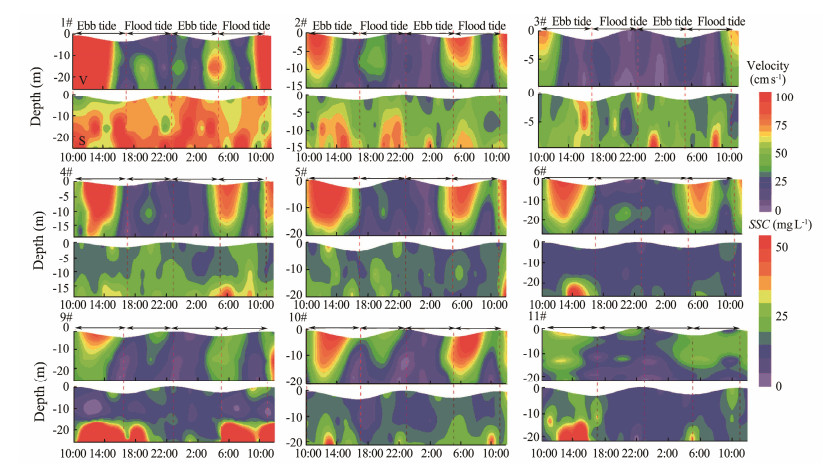

The tidal currents are irregular semi-diurnal and shows strong reciprocating flow near the Shandong Peninsula, whose reciprocating directions are parallel to the coast of Shandong Peninsula. The reciprocating currents are nonetheless weak at station 7# in the northern part of Bohai Strait (Fig.5). The average velocities at each station ranged from 29.8 to 73.4 cm s−1 during the observation period. The maximum value appeared at station 1# in Miaodao Strait, with a direction of 270°, while the minimum value was at station 3# with a direction of 70°. The energy of the tidal currents in the Bohai Strait was relatively large and the tidal current was the main hydrodynamic force (Qin et al., 1986). The maximum velocity could reach up to 1.51 m s−1, which occurred on the flood time of surface water at station 1#.

|

Fig. 5 Changes of vertical average currents at each station. |

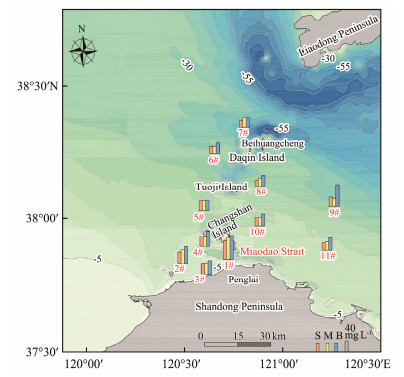

The Euler residual currents of each layer at each station were calculated according to the measured data, shown in Fig.6. The velocities of residual currents in the study area ranged from 1.5 cm s−1 to 25.0 cm s−1. The maximum value occurred in the surface layer of station 1# in Miaodao Strait with a direction of 295°, while the minimum value occurs in the middle layer of station 8# with a direction of 262°. The horizontal distribution of the residual currents was characterized by a 'high in the middle, and low in the east and west' trend, i.e., the residual currents at the stations in the Bohai Strait were stronger than those at the stations in the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea, which was mainly attributed to strait-channel effects (Chen, 2000; Zuo et al., 2012). When the water flows through the narrow Bohai Strait from the open sea during the flood and ebb tide, the water cross section becomes narrow rapidly, thereby causing the currents to converge, the energies to concentrate and the velocities to increase. Moreover, the average velocity of ebb tide is greater than that of flood tide, and the duration of ebb tide (for example, 7.5 h at station 1#) is longer than that of flood tide (6 h). The ratio of the average velocity of ebb tide to that of flood tide increased significantly from 1.30 to 2.14 from station 11# in the Yellow Sea to station 1# in the channel, and decreased down to 1.49 at station 2# in the Bohai Sea. Obviously, the existence of the channel increases the tidal current asymmetry, making the residual currents in the channel stronger than those on both sides. Vertically, the residual current velocities decrease from the surface to the bottom because of the bottom friction (Table 2). There are little differences in the surface, middle (0.6 H) and bottom residual current directions near the shore of Shandong peninsula, indicating the uniform mixing of surface and bottom water due to the strong tidal currents. Some differences were recorded at the stations off the shore. According to previous studies, the existence of thermocline renders difficult to the exchange of the waters between the surface and the bottom (Beardsley et al., 1992; Wang et al., 2014a), so the currents are different along the vertical axis.

|

Fig. 6 The distribution of vertical residual currents at each station. Red arrows, residual currents of surface layer; blue arrows, residual currents of middle layer; green arrows, residual currents of bottom layer. |

|

|

Table 2 Residual currents of surface, middle and bottom layers |

The average suspended sediment concentrations in the study area varied in the range 15.4 – 41.0 mg L−1. The maximum and minimum values appeared at station 1# (Miaodao strait) and station 6# (north of the Bohai Strait), respectively. The distribution of the SSCs is followed a trend 'high in the South and low in the north, high in the West and low in the east' (Fig.7), i.e., the SSCs of Bohai Sea are high while the concentrations of the Yellow Sea are low. Similarly, the concentrations around the Shandong Peninsula are high while the concentrations in the offshore area are low. Vertically, the SSCs increase from the surface to the bottom. SSCs tend to be high in bottom layers because of the resuspension, or advection transport of resuspended sediments in Laizhou Bay (Wang et al., 2011). The depth of the Bohai Strait increases from south to north, so the probability of resuspension in the southern channel is higher under the strong tidal current. Lin (2017) derived the sediment resuspension velocities, and suggested that sediments could resuspend in the process of ebb and flood. However, the resuspension occurs only in part of the time when the current velocities are large enough based on the comparison of SSCs and velocities (Fig.8). Moreover, except for stations 2# and 3#, the extreme of the SSCs at the other stations corresponds to the extreme velocity magnitude. However, the extreme of the SSCs at 2# and 3# stations lags 1 – 2 h behind the velocities. In addition, there are two cases mentioned above (not found) at station 1# that are in the Miaodao Strait. The SSCs at the station 1# in Miaodao Strait, which is the most important channel for the Bohai sediment transport to the outer sea (Qin et al., 1986; Wang et al., 2014), was in a high concentration state during the observation time. Therefore, resuspension may not be the main way of suspended sediment transport in the study area. The suspended sediments in the Bohai Strait have two sources: local resuspension and transportation of resuspended sediments in Laizhou Bay (Martin et al., 1993; Jiang et al., 2019). Wang et al. (2014) revealed that suspended sediments are mostly supplied by the advection of the resuspended solids in the Laizhou Bay and Yellow River, while the local resuspension is relatively small in Bohai Strait. Hence, the transport mode in the study area will be thoroughly discussed, and the importance of advection transport will be analyzed in the discussion.

|

Fig. 7 Suspended sediment concentrations of surface (S) middle (0.6 H) (M) and bottom (B) layers at each station. |

|

Fig. 8 Variation of suspended sediment concentrations and current velocities with time. |

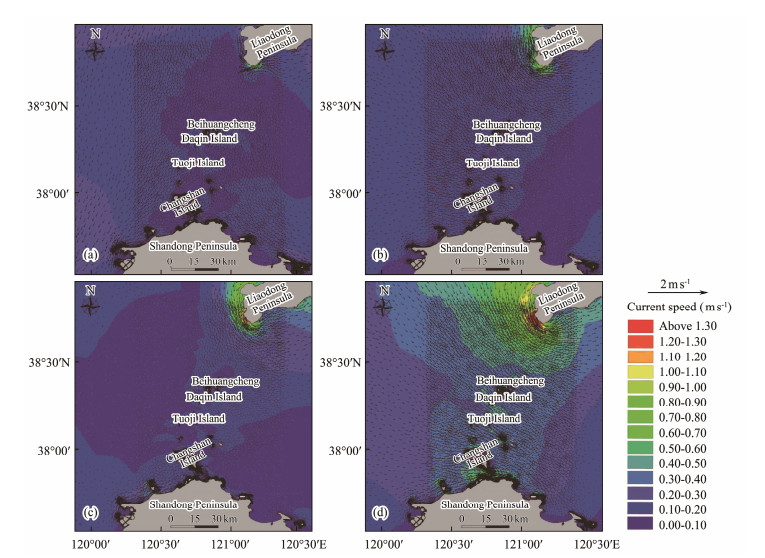

Four moments are selected to analyze the change of tide in a tide period, including the high tide, middle of ebb tide, low tide and middle of low tide. The currents in the study area are in form of obvious standing waves (Qin et al., 1986), i.e., the flow velocities reach the lowest at high tide and low tide, while the flow velocities reach the maximum at the middle of ebb tide and flood tide. The direction of simulated flood tidal currents is from Bohai Sea to Yellow Sea, and vice versa. At high tide, the velocities in Bohai Strait are generally low, being higher in the south of Liaodong Peninsula, the tail of Changshan and the coast of Shandong Peninsula, with a maximum of 1.0 m s−1; the velocities in the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea are lower than in the strait, being less than 0.6 m s−1 (Fig.9a). During ebb tide, the waters in the study area flow from the Yellow Sea to the Bohai Sea. At the middle of ebb tide, the magnitude of the velocities in the whole Bohai Strait are larger than those in the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea, and the maximum velocities can reach up to 2 m s−1, which appear in the south of Liaodong Peninsula and the tail of Changshan (Fig.9b). At low tide, the velocities reach the lowest values in a tide period, not exceeding 0.4 m s−1, and the flow direction changes from the west to the east (Fig.9c). During the flood tide, the waters flow from Bohai Sea to Yellow Sea, and the velocities reach the maximum in the middle of flood tide, yet with smaller magnitudes than those in the middle of ebb tide (Fig.9d).

|

Fig. 9 Simulated current distribution. (a), high tide; (b), middle of ebb tide; (c), low tide; (d), middle of flood tide. |

The FMDM was adopted to explain the distribution, the transport mechanism and the transport process of suspended sediments in the study area. The results show that the SSFs are between 3.8 – 89.1 g m−1 s−1 at all of the 11 stations. Moreover, the SSF direction of 2#, 10# and 11# is from Bohai Sea to Yellow Sea, as opposed to the other stations. The maximum and the minimum values appear at the station 1# and station 8#, respectively. The magnitude of each contribution shows that T1, T2 and T5 were dominant, tidal pumping effect (T3 + T4) and shear diffusion term (T6 + T7 + T8) accounted for smaller proportions. Advection item (T1 + T2) is the comprehensive sediment transport effect of the Euler residual currents and the Stokes drafts, which is not only related to the residual current values, but also to the average sediment concentrations and water depths in a local tide cycle (Hu et al., 2016). In addition, the vertical net circulation transport item (T5) is induced by the differences of residual currents vertically and the inhomogeneous vertical distributions of suspended sediments in the Bohai Strait. The vertical difference of residual currents and suspended sediments are mainly involved in the item T5, not the tidal pumping effect (Table 3). As is shown in Table 3, the advection (T1 + T2) has the greatest contribution to the whole research area, which is consistent with the previous studies (Qin et al., 1989; Wang et al., 2011), followed by T5. In addition, the Euler residual current contribution (T1) accounts for the most important proportion in the sediment transport (Lu et al., 2011).

|

|

Table 3 Suspended sediment flux (g m−1 s−1) and direction (°) in each transport item |

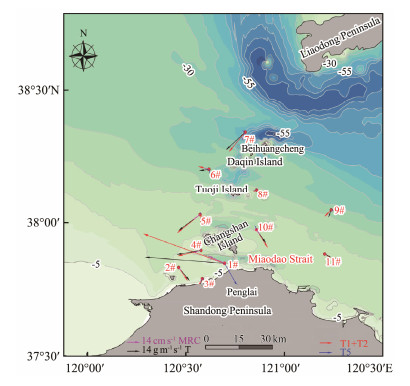

The SSF per unit area in the southern part of the Bohai Strait is the largest in the whole Bohai Strait (Fig.10), where advection transport is predominant. Based on the measured data and previous studies (Zhao et al., 1995; Jiang et al., 2019), advection plays an important role, especially at station 1#, whereby T1 is the most important part that determines the main directions of suspended sediment transport. The characteristics of transport flux correspond to those of residual currents, indicating that the southern part is an important channel for sediment transport in the Bohai and Yellow Seas and that Euler residual currents are particularly important for suspended sediment transport. The vertical net circulation also has an influence on the suspended sediment transport, mainly because of the vertical intensity variation of suspended sediment concentrations and intensity difference of residual currents vertically. Tidal pumping effect (T3 + T4) accounts for a certain proportion, which is inferior to T5. This indicates that the resuspension occur in Miaodao Strait, but not the main pattern of suspended sediment transport.

|

Fig. 10 Comparison of T, (T1 + T2), T5 and measured residual currents (MRC) at each station. |

The SSFs of stations 2#, 3#, 4#, 5#, 10#, and 11# in the central and southern Bohai Strait are lower than those of Miaodao Strait. Advection is the dominant factor, but the proportion of T5 in sediment transport has decreased significantly. These stations are distributed in the open water area, unlike 1#, which is distributed in the narrow channel and is affected by the channel effect. Therefore, the tidal currents are not as strong as those at station 1# (Fig.6), and tidal pumping effect is relatively low. Moreover, in the southern Bohai Strait, the temperature and salinity are relatively uniform along the vertical profile (Wan et al., 2004; Yuan, 2018). In addition, the vertical variation of suspended sediment concentrations is uniform and the deviation is relatively small. Although the vertical net circulation remains the second largest transport mechanism, it is still substantially smaller than the advection (Table 3).

The SSFs at stations 6#, 7#, 8# and 9#, distributed in the central and northern Bohai Strait, are generally smaller. According to Section 3.2, the great direction difference of residual currents can reach 62° and the SSCs in the bottom layers can be twice as high as those in the surface layers, so the vertical differences of residual currents and SSCs are large enough to increase T5 (Table 3). Nevertheless, tidal pumping effect is still too small to have effect on the sediment transport in the study area. The T5 of the stations in the North Yellow Sea accounts for a larger proportion than that of other areas and the vertical net circulation affects the net sediment transport alongside with advection (T1 + T2). Hence, the suspended sediment transport is mainly controlled by advection and supplemented by vertical net circulation.

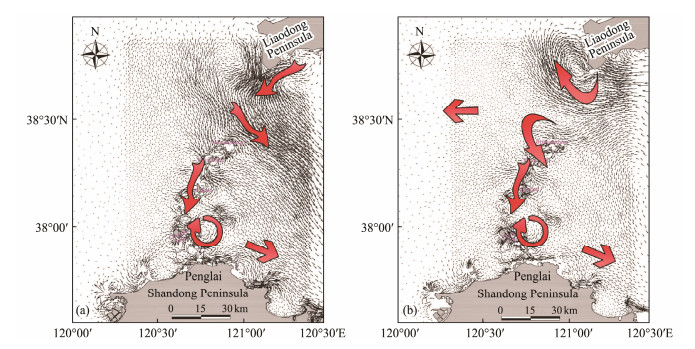

5.2 Net Sediment Transport Trend at Monthly ScaleThe study area are divided into two layers vertically, namely the surface layer and bottom layer, in order to facilitate the study of vertical suspended sediment transport characteristics. The distribution of simulated tidal residual currents in August are similar to those of measured residual currents, i.e., there is a trend of 'high in the middle, low in the east and west' (Fig.11). The residual tidal currents in the channels of the Bohai Strait are higher than the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea, and there are three high-value areas: the coast of Shandong Peninsula, the area around Miaodao Islands and Loatieshan channel. The maximum residual currents in the study area occur at the tail of Changshan in the northern part of Miaodao Strait, with a value of 56 cm s−1. According to the analysis of Section 4.1 and previous studies, tidal residual currents are the most important hydrodynamic factor for suspended sediment transport in the study area, which play an important role in sediment exchange in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea, and are the main dynamic factors for long distance transport of suspended sediments (Li et al., 2010). Therefore, the simulated residual currents can represent the transport trends of suspended sediment in summer.

|

Fig. 11 Distribution of simulated residual currents in August. (a), surface layer; (b), bottom layer. |

Regarding the transportation direction, the Bohai Strait generally has an outward transportation from the south, and inward from the north. In the Laotieshan channel, there are obvious changes in the suspended sediment transport trends vertically, whereby the main transport directions are outflow from Bohai Sea in surface layer, and inflow to Bohai Sea in the bottom layer. While there are two eddies at the bottom, clockwise in the north and anti-clockwise in the south, the main transport direction is toward the Bohai Sea. Moreover, the waters entering Bohai through Laotieshan channel divide into three parts. The first part flows clockwise into the Liaodong Bay, the second part moves westward into the Bohai Sea, and the third part moves counterclockwise to the south, which is consistent with previous observations of Bohai circulations in summer (Guan, 1994; Zhao et al., 1995) (Fig.1). Furthermore, the waters flowing to the south from the Laotieshan channel can reach the Miaodao Strait through the archipelago. In the southern and central part of Bohai Strait, the residual current directions are generally consistent along the vertical direction, which is mainly eastward to the Yellow Sea. Moreover, there are multiple eddies in the central Bohai Strait due to the numerous islands, channels and complex topography, such as the eastern vortex of Changshan Island (Fig.11).

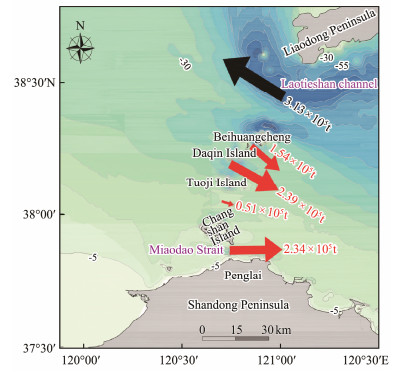

5.3 SSF in the Bohai Strait at Monthly ScaleIn order to reveal the transport process of suspended sediments in the Bohai Strait more clearly, five sections (D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5) were selected to study the SSF in the Bohai Strait in summer (Fig.1). The SSF is obtained by multiplying the projection value of hourly currents velocities in the vertical section with the cross-section area and the SSCs. The calculation time is one month, i.e., August in 2016. There is only one station in the south of the Laotieshan channel, which is not enough to represent the whole channel. According to previous studies, the variation of SSCs in Bohai Sea deep water layer are small, with an average of 10.5 mg L−1 (Qin et al., 1986). Hence, the SSCs of D1 are taken from Qin et al. (1986), while the SSCs of the others are the averages of the measured values at the stations near each section (Table 4). The direction perpendicular to the section toward the Yellow Sea is positive, and vice versa. The calculation formula is as follows:

| $ SSF = v \times \sin (\alpha - \beta) \times S \times SSC, $ | (10) |

|

|

Table 4 Cross section information and calculated SSFs |

where v is the instantaneous current velocity, α is the current direction, β is the angle of the first quadrant of the section, and S is the single width area of the section.

The net water flux and SSF of Laotieshan channel in August was 2.03×1010 m3 and 3.13×105 t respectively, with a dominating direction of being westward into Bohai. The Laotieshan channel is the largest waterway in the Bohai Strait with the largest currents, and it is the most important channel for the Yellow Sea warm water flowing into Bohai Sea. Although the SSCs near Laotieshan channel are relatively low, the immense discharge makes it the largest sediment transport channel in the whole Bohai Strait in summer. The net water flux and SSF in D2 and D3 sections are opposite to the Laotieshan channel. As shown in Fig.11, part of the water flowing into Bohai through the Laotieshan channel flows back to the Yellow Sea from the D2 and D3 sections along the counter clockwise direction, forming an anticlockwise vortex (Fig.11). The net water flux and SSF in D4 are smallest, due to the approximate balance of inflow and outflow. The Miaodao Strait (D5) is the second-largest channel for the sediment transport, with a net sediment transport capacity of 2.34×105 t from the Bohai Sea to the Yellow Sea in summer. Although the cross-section area of Miaodao Strait is relatively small, accounting for 1/24th of the total cross-section, the SSF per unit area is 2.16 t m−2 month−1, 9 times more than that of Laotieshan channel, corresponding to the results of the above flux mechanism decomposition.

The whole Bohai Strait follows the sediment transport pattern of moving outward from the south and inward from the north in summer, as observed in winter (Qin et al., 1986; Wang et al., 2020). That is, the net sediment transport directions of sections D1 in the north Bohai Strait are westward into Bohai Sea, while for other sections in south Bohai Strait they are eastward into Yellow Sea (Fig.12).

|

Fig. 12 Net transport trend and SSF of each section. Red arrows represent the SSF from the Bohai Sea to the Yellow Sea; black arrow represents the SSF from the Yellow Sea to the Bohai Sea. |

Moreover, the outflow exceeds the inflow of Bohai in August, with the net water flux of 1.4×1010 m3, i.e., same as the delivery of the rivers which flow into the Bohai Sea. Since the amount of sediments moving out from the Bohai Sea is larger than the amount in, one may conclude that sediments are mainly transported out of Bohai Sea through the Bohai Strait in August, which is in agreement with previous studies (Zhang et al., 2018). The estimate values of SSF from the Bohai Sea to the Yellow Sea reported in previous investigations ranged from 5 to 40 Mt yr−1 (Qin and Li, 1982; Martin et al., 1993; Bi et al., 2011). The SSF obtained in this study is 0.33 Mt under the action of tidal currents in the Bohai Strait in August. If the whole year could be only divided into summer and winter, as suggested by Bi et al. (2011), the SSF of the Bohai Strait in summer is 1.98 Mt, which is in the range of the values reported in previous studies. The SSCs are the vertical average of 25 h synchronously observed in summer, and the concentration references of each station are near the section. Meanwhile, the currents data simulated by one hour and the transport directions of suspended sediments are consistent with those presented in Section 4.2. Therefore, the results presented herein provide a more realistic insight of the suspended sediment flux in summer period.

6 ConclusionsThe field observations showed that the suspended sediment transport was mainly controlled by advection and also influenced by vertical net circulation, while resuspension was relatively weak in Bohai Strait. Moreover, Euler residual currents are the main dynamic mechanism of suspended sediment transport in summer. The suspended sediment flux varied between 3.8 and 89.1 g m−1 s−1, with the maximum value in the Miaodao Strait. Combined with the numerical simulation results, the sediment transport in the Bohai Strait can be found to follow the pattern of moving outward from the south, and inward from the north in summer, i.e., the sediments are carried into the Bohai Sea through the Laotieshan channel, while out of the Boahi Sea through other channels. The outflow exceeds the inflow in August, with the net water flux of 1.4×1010 m3, same as the delivery of the Rivers which flow into the Bohai Sea. Moreover, the net suspended sediment flux is estimated to be 0.33 Mt under the action of tidal currents in the Yellow Sea in August.

AcknowledgementsThis study was jointly funded by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (No. ZR2019 MD037), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41776059).

Beardsley, R., Limeburner, R., Kim, K., and Candela, J., 1992. Lagrangian flow observations in the East China, Yellow and Japan Seas. La Mer, 30(3): 297-314. (  0) 0) |

Bi, N. S., Yang, Z. S., Wang, H., Fan, D., Sun, X., and Lei, K., 2011. Seasonal variation of suspended-sediment transport through the southern Bohai Strait. Estuarine Coastal & Shelf Science, 93(3): 239-247. (  0) 0) |

Bornhold, B. D., Yang, Z. S., Keller, G. H., Prior, D. B., Wiseman, W. J., Wang, Q., et al., 1986. Sedimentary framework of the modern Huanghe (Yellow River) delta. Geo-Marine Letters, 6(2): 77-83. DOI:10.1007/BF02281643 (  0) 0) |

Bowden, K. F., 1964. The mixing processes in a tidal estuary. Advances in Water Pollution Research, 7(6): 329-346. (  0) 0) |

Chen, S. L., 2000. Hydrodynamics, sediments and strait-channel effects for the Qiqu Archipelago. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 22(3): 123-131 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0253-4193.2000.03.017 (  0) 0) |

Duan, H., Xu, J., Wu, X., Wang, H., Liu, Z., and Wang, C., 2020. Periodic oscillation of sediment transport influenced by winter synoptic events, Bohai Strait, China. Water, 12(4): 986. DOI:10.3390/w12040986 (  0) 0) |

Fairley, I., Masters, I., and Karunarathna, H., 2015. The cumulative impact of tidal stream turbine arrays on sediment transport in the Pentland Firth. Renewable Energy, 80: 755-769. DOI:10.1016/j.renene.2015.03.004 (  0) 0) |

Fang, Y., Fang, G. H., and Zhang, Q. H., 2000. Numerical simulation and dynamic study of the wintertime circulation of the Bohai Sea. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 18(1): 1-9 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.1007/BF02842535 (  0) 0) |

Guan, B. X., 1994. Patterns and structures of the currents in Bohai, Huanghai and East China Seas. Springer Netherlands, 1: 17-26 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Hu, R. J., 2009. Sediment transport and dynamic mechanism in the Zhoushan Archipelago sea area. PhD thesis. Ocean University of China.

(  0) 0) |

Hu, R. J., Ma, F., Wu, J., Zhang, W., Jiang, S., Xu, Y., et al., 2016. Sediment transport in the nearshore area of Phoenix Island. Journal of Ocean University of China, 15(5): 767-782. DOI:10.1007/s11802-016-2967-z (  0) 0) |

Huang, D., Chen, Z. Y., and Su, J. L., 1999. Application of threedimensional shelf sea model in Bohai Sea: I. Tidal current, wind-driven circulation and their interaction. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 18(5): 1-13 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Huang, D., Su, J., and Backhaus, J. O., 1999. Modelling the seasonal thermal stratification and baroclinic circulation in the Bohai Sea. Continental Shelf Research, 19(11): 1485-1505. DOI:10.1016/S0278-4343(99)00026-6 (  0) 0) |

Huang, S., Li, K., Jiang, G., and Lu, J., 2013. Research on water exchange in Pearl River Estuary based on MIKE3 model. Environmental Science and Management, 38(8): 134-140 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-1212.2013.08.034 (  0) 0) |

Ingram, R. G., 1981. Characteristics of the Great Whale River plume. Journal of Geophysical Research, 86(C3): 2017-2023. DOI:10.1029/JC086iC03p02017 (  0) 0) |

Jay, D. A., Geyer, W. R., Uncles, J. R., Vallino, J., Largier, J., and Boynton, W. R., 1997. A review of recent developments in estuarine scalar flux estimation. Estuaries, 20(2): 262-280. DOI:10.2307/1352342 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, S. H., Wang, N., Cheng, H. Y., and Yin, Y. J., 2019. The study on hydrodynamic distribution characteristics of the Bohai Strait. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 49(S1): 66-73 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Li, G., Tang, Z., Yue, S., Zhuang, K., and Wei, H., 2001. Sedimentation in the shear front of the Yellow River Mouth. Continental Shelf Research, 21(6): 607-625. (  0) 0) |

Li, G., Xue, X., Liu, Y., Wang, H., and Liao, H., 2010. Diagnostic experiments for transport mechanisms of suspended sediment discharged from the Yellow River in the Bohai Sea. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 20(1): 49-63. DOI:10.1007/s11442-010-0049-5 (  0) 0) |

Li, J., Song, J., Mu, L., Wang, Y., Li, Y., and Wang, G. S., 2015. Characteristics of sea water exchange between Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea under the effect of high wind in winter. Marine Science Bulletin, 34(6): 647-656 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Lin, J. J., 2017. Suspended sediment distribution and transport mechanism in the Penglai inshore sea area. Master thesis. Ocean University of China.

(  0) 0) |

Lin, X. P., Wu, D. X., Bao, X. W., and Jiang, W. S., 2002. Study on seasonal temperature and flux variation of the Bohai Strait. Journal of Qingdao Ocean University, 32(3): 355-360 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Lu, J., Qiao, F. L., Wang, X. H., Wang, Y. G., Teng, Y., and Xia, C. S., 2011. A numerical study of transport dynamics and seasonal variability of the Yellow River sediment in the Bohai and Yellow Seas. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science, 95(1): 39-51. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2011.08.001 (  0) 0) |

Martin, J. M., Zhang, J., Shi, M. C., and Zhou, Q., 1993. Actual flux of the Huanghe (Yellow River) sediment to the Western Pacific Ocean. Netherlands Journal of Sea Research, 31(3): 243-254. DOI:10.1016/0077-7579(93)90025-N (  0) 0) |

Milliman, J. D., and Meade, R. H., 1983. World-wide delivery of river sediment to the oceans. Journal of Geology, 91(1): 1-21. DOI:10.1086/628741 (  0) 0) |

Qiao, L., 2008. Circulation and sediments transport due winter storms in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea. PhD thesis. Ocean University of China.

(  0) 0) |

Qiao, L., Zhong, Y., Wang, N., Zhao, K., Huang, L., and Wang, Z., 2016. Seasonal transportation and deposition of the suspended sediments in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea and the related mechanisms. Ocean Dynamics, 66(5): 751-766. DOI:10.1007/s10236-016-0950-2 (  0) 0) |

Qin, Y., Zhao, Y., and Zhao, S., 1986. The Bohai Sea Geology. Science Press, Beijing, 232pp.

(  0) 0) |

Qin, Y. S., and Li, F., 1982. Study on the suspended matter of the sea water of the Bohai Gulf. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 4(2): 191-200. (  0) 0) |

Qin, Y. S., Li, F., Xu, S. M., Milliman, J., and Limeburner, R., 1989. Suspended matter in the South Yellow Sea. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 20(2): 101-112. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0029-814X.1989.02.002 (  0) 0) |

Uncles, R., Elliott, R., and Weston, S. A., 1985. Dispersion of salt and suspended sediment in a partly mixed estuary. Estuaries, 8(3): 256-269. DOI:10.2307/1351486 (  0) 0) |

Wan, X. Q., Bao, X. W., Wu, D. X., and Jiang, H., 2004. Numerical diagnostic simulation of tide-induced, wind-driven and thermohaline currents in the Bohai Sea. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 35(1): 41-47. (  0) 0) |

Wang, C. H., Liu, Z. Q., Harris, C. K., Wu, X., Wang, H. J., Bian, C. W., et al., 2020. The impact of winter storms on sediment transport through a narrow strait, Bohai, China. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125(6): 1-23. (  0) 0) |

Wang, H. J., Wang, A. M., Bi, N. S., Zeng, X. M., and Xiao, H. H., 2014. Seasonal distribution of suspended sediment in the Bohai Sea, China. Continental Shelf Research, 90: 17-32. DOI:10.1016/j.csr.2014.03.006 (  0) 0) |

Wang, H. J., Yang, Z. S., Li, Y. H., Guo, Z. G., Sun, X. X., and Wang, Y., 2007. Dispersal pattern of suspended sediment in the shear frontal zone off the Huanghe (Yellow River) Mouth. Continental Shelf Research, 27(6): 854-871. DOI:10.1016/j.csr.2006.12.002 (  0) 0) |

Wang, J., Jin, P., Bishop, P. L., and Li, F., 2011. A preliminary study on water the turbidity distribution characteristics of in the North Yellow Sea in summer. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 6(2): 288-293 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Wei, Z. X., Li, C. Y., Fang, G. H., and Wang, X. Y., 2003. Numerical diagnostic study of the summertime circulation in the Bohai Sea and the water transport in the Bohai Strait. Advances in Marine Science, 21(4): 454-464 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6647.2003.04.013 (  0) 0) |

Wu, X., Wu, H., Wang, H., Bi, N., Duan, H., Wang, C., et al., 2019. Novel, repeated surveys reveal new insights on sediment flux through a narrow strait, Bohai, China. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 124: 1-15. (  0) 0) |

Xiao, H., Wang, H. J., and Bi, N. S., 2015. Seasonal variation of suspended sediment in the Bohai and Yellow Sea and the pathway of sediment transport. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 35(2): 11-21 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yuan, X. D., 2018. Distribution and transport mechanism of suspended sediment in the southern Bohai Strait. Master thesis. Ocean University of China.

(  0) 0) |

Zhang, Z., Qiao, F., Guo, J., and Guo, B., 2018. Seasonal changes and driving forces of inflow and outflow through the Bohai Strait. Continental Shelf Research, 154: 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.csr.2017.12.012 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, B. R., Cao, D. M., Li, H. C., and Lei, F. H., 2001. Tidal mixing characters and tidal fronts phenomenons in the Bohai Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 23(4): 113-118. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0253-4193.2001.04.015 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, B. R., Zhuang, G. W., Cao, D. M., and Lei, F. H., 1995. Circulation, tidal residual currents and their effects on the sedimentations in the Bohai Sea. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 26(5): 466-473 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0029-814X.1995.05.003 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, S. X., Ding, P. X., Shi, F. Y., and Zhu, J. Y., 2005. Numerical study on residual current and its effect on mass transport in the Hangzhou Bay and the Changjiang Estuary Ⅱ. Residual current and its effect on mass transport in winter. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 22(6): 1-12. (  0) 0) |

Zuo, S., Zhang, N., Li, B., and Chen, S., 2012. A study of suspended sediment concentration in Yangshan deep-water port in Shanghai, China. International Journal of Sediment Research, 27(1): 50-60. DOI:10.1016/S1001-6279(12)60015-8 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22