2) Ocean College, Zhejiang University, Zhoushan 316021, China

Internal waves (IWs) are ubiquitous in stratified oceans. Internal tides and lee waves are two standard types of IWs, with internal tides and lee waves being two common types. Internal tides are generated when barotropic tidal currents flow over diverse topographies, such as continental slopes, sills, ridges, and submarine canyons (Baines, 1982; Lamb, 1994). Low phase speed and strong vertical shear dissipate high-mode internal tides near their generation sites, whereas low-mode internal tides can propagate for long distances in the ocean (Zhao et al., 2010, 2016). The breaking of internal tides can lead to improved turbulent mixing in the ocean, which supplies energy to the meridional overturning circulation (Munk and Wunsch, 1998; Garrett, 2003). The IWs generated by the interaction between geostrophic flow and small-scale topography are called lee waves (Nikurashin and Ferrari, 2010a, 2010b). Lee waves can obtain energy from the background flow and then transmit it to the small-scale turbulence when they break, which finally facilitates turbulent mixing in the global ocean (Legg, 2021). From the energy view, the relations between barotropic tide and large-scale seamount [O(100 km)] comprise the primary energy flux entering the ocean. Lee waves perform a crucial function in energy dissipation in the abyss, although they have a lower energy level than internal tides (Shakespeare, 2020).

Bell (1975) obtained the linear solution for internal lee waves generated by the interaction of the quasi-steady uniform flow and small-scale [O(0.1-10.0) km] topographies in a stratified fluid. Lee waves can radiate out only when f < |k·U0| < N, where U0 is the background flow velocity; k is the topographic wavenumber vector; f and N are the local Coriolis and buoyancy frequencies, respectively. The factor that decides the nonlinearity of lee waves is identified as the lee wave Froude number: Frlee = NH/U0, where H is the topography height. For subcritical topography, Frlee < < Frleec (Frleec ≈ 0.7 in 2D simulations), the subsequent lee wave is linear, and the energy flux increases quadratically with Frlee. However, for the supercritical case (Frlee > Frleec), the lee wave is nonlinear, and its energy flux stops increasing with Frlee due to upstream blocking and splitting (Winters and Armi, 2014; Sun et al., 2022). Based on this theory, numerous studies have approximated the energy conversion rate from background flows to lee waves in the global ocean. The energy conversion rates range from 0.15 to 0.75 TW (Scott et al., 2011; Melet et al., 2014; Nikurashin et al., 2014; Wright et al., 2014; Trossman et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018).

Most of the previous studies concentrated on internal tides and lee waves separately (Aguilar et al., 2006; Dossmann et al., 2016; Cusack et al., 2017; He and Lamb, 2021; Chesnokov et al., 2022). However, barotropic tidal currents and background flows coexist at many IW generation sites. Shakespeare (2020) expanded Bell's theory of linear IW and considered the linear coupling of internal tides and lee waves. His work depicted that the presence of tides suppresses the energy flux into lee waves by 13% – 19%. Dossmann et al. (2020) conducted experiments on the mechanism of IWs by including the blend of an oscillatory flow and a steady flow in the laboratory. Compared with Shakespeare's theory, they also examined the structure and energy flux of IWs. However, their experiments emphasized the asymmetry of IW beams in the small mean excursion distance parameter є = kU0/ω (є < 0.1), where ω is the tidal frequency. The energetics of IWs in large є (є ≈ 0.5) still needs clarification.

Consistent with the global distribution of mean excursion distance parameters specified by Dossman et al. (2020), є ≈ 0.1 occurs near the midocean ridge, whereas є reaches about 0.5 near the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. The present study expands their work by referring to the global mean excursion distance parameter distribution. A numerical tank is developed to perform a series of 2D experiments and examine the energetics of internal tides and lee waves generated by barotropic tidal currents and background flows with diverse intensities. This paper is arranged as follows: In Section 2, the model configuration and analysis methods are presented. In Section 3, the physical processes and energetics of internal tides and lee waves, as well as their interaction, are investigated. In Section 4, the conclusions are discussed.

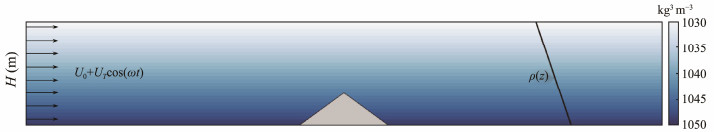

2 Model Configuration and Methods 2.1 Model ConfigurationThe Massachusetts Institute of Technology general circulation model (MITgcm; Marshall et al., 1997) is implemented to simulate the internal tide and the lee wave in this paper. The model has been effectively applied in replicating fluid motions at the laboratory scale (Kurkina et al., 2016; He et al., 2023). A diagram of the model setup is presented in Fig.1. The domain is 8 m in length and 0.2 m in depth; it has a uniform vertical resolution (∆z = 0.0025 m) and a variable horizontal resolution (from ∆x = 0.005 m at the center to ∆x = 0.1 m near the boundary). The bottom topography is established as a triangle to represent an isolated ridge in the ocean, which has a maximum height of h0 = 6 cm and a slope of dh/dx = 0.75. The time step ∆t is 0.05 s, and the data output occurs every 0.5 s. The combination of background flow and barotropic tidal currents (u = U0 + UTcos(ωt)) is added into the model from the left boundary.

|

Fig. 1 Schematic of the experimental setup, where the gray triangle denotes the topography. |

Linear stratification is applied in all these experiments. The density (ρ) linearly rises from 1030 kg m−3 at the surface to 1050 kg m−3 at the bottom. Thus, the buoyancy frequency is a constant (N2 = 0.94 rad s−2), which is determined as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} N^{2}=-\frac{g}{\rho} \frac{\mathrm{~d} \rho}{\mathrm{~d} z}, \end{equation*} $ | (1) |

where g is the gravity acceleration. Rotation is not considered in this model as the focus is not on generation processes near the Coriolis frequency.

Several dimensionless parameters, such as Frlee and є, determine the dynamical properties of IWs. Frlee establishes the nonlinearity of the lee wave. For Frlee < < Frleec, the lee wave is entirely linear, and its dynamical characteristics can be well predicted by linear theory. Its energy flux increases quadratically with Frlee, similar to previous studies (Mayer and Fringer, 2017, 2020). For Frlee > Frleec, the subsequent lee waves are nonlinear, and their energy flux ceases to increase with increasing Frlee. The separation of energy conversion to propagating lee waves and nonpropagating components is intricate and not fully comprehended. Thus, Frlee > Frleec is set in all experiments, except Case T0 (Table 1).

|

|

Table 1 Parameters for simulations |

The mean excursion parameter є quantifies the distance traveled by a particle moving with a steady background flow in relation to the topographic length throughout a tidal period. є also quantifies the comparative magnitude of the quasi-Doppler shift and, thus, the asymmetry between the upstream and the downstream beams. A total of 19 experiments are devised in this study. In Cases T0 and UT1 – UT9, the tidal frequency ω = 0.65 rad s−1, and the barotropic velocity amplitude UT = 0.0025 m s−1. In Cases T0 (U1 – U9), only the barotropic tidal current forcing (background flow) is included, whereas in Cases UT1 – UT9, the barotropic tidal current forcing and background flow are both added to the model. The dimensionless parameters of each experiment are presented in Table 1.

2.2 MethodsThe energetics of internal tides and lee waves were determined to identify the propagation and dissipation of these two types of IWs that are contingent on the velocity and density data obtained from the numerical model. Normalized horizontal velocity u* is defined to characterize the structures of IWs as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} u^{*}(x, z, t)=\frac{u(x, z, t)-U_{0}}{U_{0}}, \end{equation*} $ | (2) |

where u(x, z, t) is the horizontal velocity acquired from the model.

Kinetic energy density Ek (KE) and the available potential energy density Ea (APE) are expressed as follows:

| $ \begin{gather*} E_{\mathrm{k}}=\frac{1}{2} \rho_{0}\left(u^{2}+w^{2}\right), \end{gather*} $ | (3) |

| $ \begin{gather*} E_{\mathrm{a}}=\frac{1}{2} \frac{g^{2} \rho^{\prime 2}}{\rho_{0} N^{2}}, \end{gather*} $ | (4) |

where ρ0 is the reference density. $\rho^{\prime}(x, z, t)=\rho(x, z, t)-$\bar{\rho}(z)$ is the perturbation density correlated with IWs, which is the variance between instantaneous density ρ and background density

| $ \begin{gather*} \varepsilon=4 v\left[\overline{\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}\right)^{2}}+\overline{\left(\frac{\partial w}{\partial z}\right)^{2}}+\overline{\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} \frac{\partial w}{\partial z}\right)}+\frac{3}{4} \overline{\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}+\frac{\partial w}{\partial x}\right)^{2}}\right], \end{gather*} $ | (5) |

| $ \begin{gather*} S^{2}=\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\right)^{2} \end{gather*}, $ | (6) |

where $\overline{(\cdot)}$ is the mean over a tidal period and ν = 1 × 10−6 m2 s−1 is the molecular viscosity.

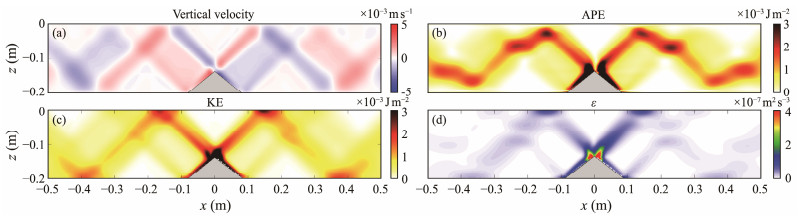

3 Results 3.1 Internal Tide CharacteristicsFig.2 demonstrates the results of experiment T0. Fig.2(a) establishes that in the lack of a steady background flow (є = 0), symmetrical internal tide beams are generated above the ridge. The angle θ between the beams and the horizontal direction is in line with the theoretical angle from the linear dispersion relation. The topographic criticality parameter $\mathit{γ}=\frac{\mathrm{d} h}{\mathrm{~d} x} / s=0.83 < 1$, where $\frac{\mathrm{d} h}{\mathrm{~d} x}$ is the slope of the topography, s is the slope of the internal tide beams, and γ < 1 denotes that the topography is subcritical. Thus, two beams are radiated from the ridge. Away from the ridge, dissipation leads to wider, weaker beams. The beams are reflected when propagating to the surface and bottom with the change in velocity direction. Figs.2(b) and 2(c) illustrate the period-averaged APE and KE of Case T0. The energy above the topography reveals a symmetrical structure, and the greatest energy emerges on the top of the topography. Large energy can be also identified at the surface and bottom reflection points. Energy declines quickly after reflection. This result is consistent with the turbulent dissipation rate shown in Fig.2(d).

|

Fig. 2 Snapshots of the internal tide (a) vertical velocity at t = 125 s, (b) period-averaged APE, (c) period-averaged KE, and (d) turbulent dissipation rate. |

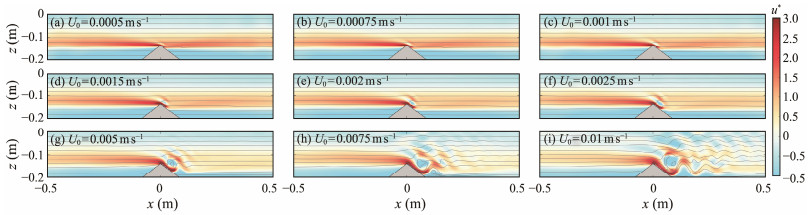

Fig.3 presents the spatial distribution of the normalized horizontal velocity u* for the lee wave in Cases U1 – U9. With the increase in U0, a distinct lee wave structure appears behind the topography, and the disturbance on isopycnals becomes more prominent with a greater influence range. In Case U9, the wave structure expands downstream beyond 0.5 m. Because Frlee > Frleec in Cases U1 – U9 (Table 1), the lee wave is characterized by blocking and it propagates above the topography with a vertical scale of U0/N. An intense downslope jet emerges at the top of the ridge. As the background flow velocity rises, the downslope jet velocity near the top of the ridge also increases, and the isopycnals experience more intense shifts. These results agree with the conclusions of Klymak et al. (2010). This jet, formed on the lee side, descends along the slope. The low-density fluid displaces the high-density fluid and forms jet shear and density inversion in the descending downslope jet. This development causes a localized dissipation hotspot (Winters and Armi, 2012; Winters, 2016).

|

Fig. 3 (a) – (i) Snapshots of normalized horizontal velocity u* of the lee wave under different background flow velocities from U0 = 0.0005 – 0.01 m s−1 at t = 125 s, where the background color shows the normalized horizontal velocity, and the solid lines depict the isopycnals. |

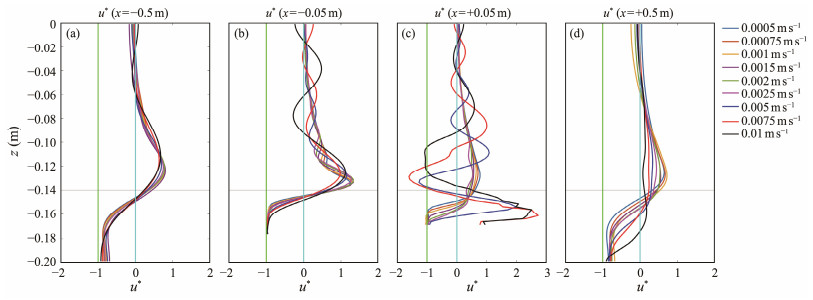

Fig.4 demonstrates the vertical profiles of the horizontal normalized velocity u* at x = ±0.05 m and x = ±0.5 m. Far from the topography in the upstream direction (x = −0.5 m), an accelerated jet emerges above the ridge with a peak speed exceeding 1.5U0. The vertical range of the jet is slightly smaller than 0.1 m, which is almost the same in Cases U1 – U9. Below the jet, the fluid is blocked and stagnant, whereas above the jet, the fluid has a velocity of U0. In front of the topography (x = −0.05 m), positive and negative velocities occur in turn. This indicates the generation of lee waves. The accelerated layer is thinner, and the maximum speed is more than 2U0. Behind the topography (x = +0.05 m), the results in Cases U1 – U6 differ from those in Cases U7 – U9. In Cases U1 – U6, similar structures emerge as x = −0.05 m with a weaker maximum speed, which is lower than 2U0. By contrast, in Cases U7 – U9, a layer with almost zero velocity is above z = −0.15 m. Below this layer, a downslope jet has a maximum velocity exceeding 3U0. The farthest location in the downstream direction is at x = +0.5 m. The vertical profiles of u* are similar to those at x = −0.5 m. However, the u* in Cases U7 – U9 are smaller than those in the other experiments because of the compelling blocking due to the lee waves.

|

Fig. 4 Normalized horizontal velocity profile at t = 125 s, where (a), (b), (c), and (d) are the velocity structures at x = −0.5, −0.05, 0.05, and 0.5 m, respectively. The horizontal gray line indicates the top plane of the topography, the vertical cyan line represents u* = 0, and the vertical green line signifies u* = −1. Different U0 are indicated by solid lines in diverse colors. |

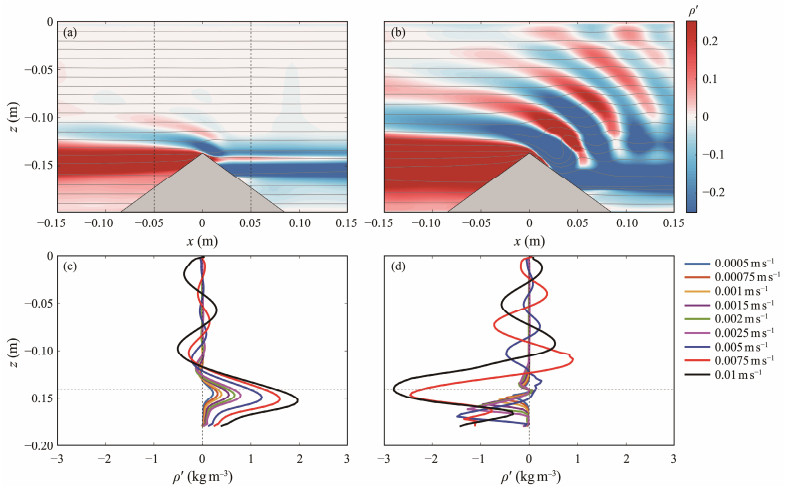

Figs.5(a) – 5(b) explain the density perturbation in Cases U4 (U0 = 0.0015 m s−1) and U7 (U0 = 0.005 m s−1), where the lee waves are clearly revealed by the fluctuations of positive and negative density perturbations. The growth of the background velocity expands the wavelength and the influence range of lee waves. The vertical profiles of the density perturbation at x = ±0.05 m (dashed line in Fig.5(a)) are presented in Figs.5(c) and 5(d). Positive perturbations are primarily produced in the upstream direction (Fig.5(c)). In Case U9, the maximum value and range of the positive perturbation increase with U0 and reach 2 kg m−3 and 0.11 m, respectively. In the downstream direction, negative density perturbations are foremost in Cases U1 – U6. In Cases U7 – U9, positive and negative density perturbations exist alternately due to powerful lee waves.

|

Fig. 5 Snapshots of density perturbation for (a) U0 = 0.0015 m s−1 (Frlee = 38.8) and (b) U0 = 0.005 m s−1 (Frlee = 11.6) at t = 125 s and (c) density perturbation at x = −0.05 m, and (d) x = +0.05 m with different U0. The vertical dashed line in (a) indicates the profile corresponding to (c) and (d) for x = ±0.05 m, the horizontal dashed line in (c) and (d) denotes the top plane of the topography, and the vertical dashed line indicates ρ' = 0. |

In this part, the energetics of IWs around the topography with the joint effect of background flow and barotropic tidal currents are examined.

Dossman et al. (2020) specified four regimes for IWs due to the combination of a steady flow and an oscillatory flow. Consistent with the dispersion relation of internal waves, the frequency of IWs is formulated as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} \bar{\omega}=\omega-k \cdot U_{0} \text{,} \end{equation*} $ | (7) |

where ω is the frequency of the oscillatory flow, and k·U0 is a quasi-Doppler frequency shift induced by the steady flow U0 onto the IWs of the horizontal wavenumber k.

In the first regime, ω = 0, which relates to the classical lee wave generated by the steady background flow.

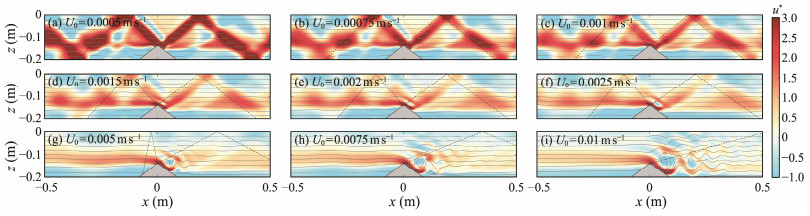

In the second and third regimes, the oscillation is prompted by upstream or downstream currents. The influence of Doppler shift causes the frequencies of the upstream and downstream beams to become $\bar{\omega}_{\text {up }}=\omega+k \cdot U_{0}$ and $\bar{\omega}_{\text {down }}$ $=\omega-k \cdot U_{0}$, respectively. Thus, the intrinsic frequency of IWs and the angle between IW beams and horizontal direction are modified due to the upstream and downstream flows and lead to an asymmetric pattern (Fig.6).

|

Fig. 6 (a) – (i) Snapshots of the normalized horizontal velocity u* of internal tides and lee waves under coupled flow velocity conditions from U0 = 0.0005 – 0.01 m s−1 at t = 125 s, where the background color indicates the normalized horizontal velocity, the dashed lines represent the theoretical beams, and the solid lines depict the isopycnals. |

The final regime is the 'tidal lee wave', which has a larger wavenumber than the classical lee wave and only arises under the effect of barotropic tidal currents. This case is beyond the scope of this paper.

The manifestation of the background flow results in a substantial asymmetry between the upstream and downstream beams; the upstream beam is steeper than the downstream one. The asymmetry is more distinct with the increase in the background flow velocity, which is consistent with the theoretical values (Fig.6). When U0 < UT (Figs.6(a) – 6(e)), the wavefield remains governed by the internal tides. Then, with the increase in U0, the lee waves steadily occur, and the downstream motion becomes disordered. When U0 > UT (Figs.6(g) – 6(i)), lee waves become the dominant, and the internal tides are virtually invisible.

The modal decomposition of IWs distributes their energy among modes. The full-depth tidal currents of each component can be reconstructed by the addition of barotropic tidal currents to baroclinic tidal currents, where the horizontal tidal currents and the vertical displacement can be expressed as follows:

| $ \left\{\begin{array}{c} u(z, t)=\sum\limits_{m=0}^{\infty} u_{m}(z, t)=\sum\limits_{m=0}^{\infty}\left[\hat{u}_{m}(t) \cdot \Pi_{m}(z)\right] \\ \eta(z, t)=\sum\limits_{m=1}^{\infty} \eta_{m}(z, t)=\sum\limits_{m=0}^{\infty}\left[\hat{\eta}_{m}(t) \cdot \phi_{m}(z)\right] \end{array}\right., $ | (8) |

where u and η denote the horizontal velocity and displacement, respectively; $\hat{u}_{m}$ and $\hat{\eta}_{m}$ are the mth modal magnitudes of the horizontal velocity and displacement, respectively; Πm and ϕm are the normal mode of the horizontal velocity and displacement, respectively.

By solving the Taylor-Goldstein equation:

| $ \left\{\begin{array}{c} \phi_{z z}+\left(\frac{N^{2}}{\left(U_{0}-c\right)^{2}}-\frac{U_{0}^{\prime \prime}}{\left(U_{0}-c\right)^{2}}-k_{h}^{2}\right) \phi=0 \\ \phi(0)=\phi(H)=0 \end{array}\right., $ | (9) |

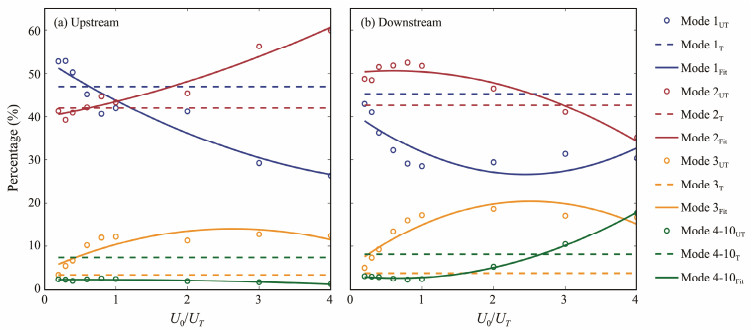

where the normal mode ϕ and wave phase speed c are obtained, where kh is the horizontal wave number, and the prime indicates the z derivative. The structure of Π is acquired from the derivative of ϕ with respect to z. The amplitude of each mode is calculated using the method of Cao et al. (2015). Subsequently, the kinetic energy of each mode is determined. The first 10 modes are included in modal decomposition, which is enough to reconstruct the velocity and displacement. The proportion of modal energy in the total energy at each vertical profile is computed initially. Next, they are averaged between x = −0.5 m (x = 0.1 m) and x = −0.1 m (x = 0.5 m), as presented in Fig.7. Modes 4 – 10 possess less energy; therefore, they are collectively called high modes.

|

Fig. 7 Horizontally averaged KE shares for each mode in (a) upstream and (b) downstream, where the different colors indicate diverse modes, the circles and solid lines indicate the simulation results and the fitting results (quadratic fitting), respectively, and the dashed lines depict the Case T0 results. |

The proportions of each mode in the upstream and downstream directions are similar when the internal tides alone are regarded. The sum of the first two modes comprises 80% of the total energy. However, the modal energy proportions change substantially when internal tides and lee waves are regarded. In Cases UT1 – UT9, mode-2 energy slowly governs and becomes ultimately higher than mode-1 energy. Mode-3 energy is also improved compared with Case T0.

In the upstream direction, with the rise in U0/UT, the proportions of mode-2 and mode-3 rise by around 20% and 10%, respectively, whereas that of mode-1 declines by approximately 27%. In the downstream direction, the first two modes' energy decreases, high-mode waves can propagate longer distances without dissipating rapidly at the generation site, and the proportions of energy are substantially improved. The mode-3 wave can explain up to about 20% of the energy, which is far greater than that of the mode-3 wave (3.7%) in Case T0. The energy of the high-mode waves is greater than that of the energy in Case T0 when U0/UT ≥ 3, and the maximum value is 20% in Case UT9.

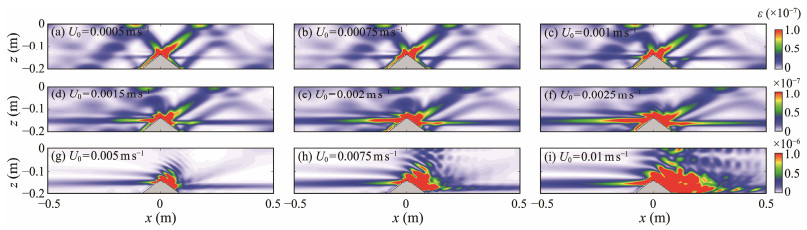

The deviation in turbulent dissipation rate is discussed subsequently. Dissipation enhancement due to diverse background flow intensities is different. In Cases UT1 – UT6, the beam structures of the internal tides remain apparent, the internal tide generation site presents an area of strong dissipation, and the background flow can considerably strengthen the dissipation. In Case UT1, the maximum dissipation value can be as high as 2.17 × 10−5 m2 s−3, which is two orders of magnitude greater than that in Case U1 (3.41 × 10−7 m2 s−3). The upstream beam slowly fades, and the lee wave structure becomes evident when the background flow velocity keeps rising. When U0/UT > 1 (Figs. 8(g) – 10(i)), the dissipation due to internal tides can be ignored, and lee waves lead. In Cases U and UT, the dissipation under these situations is basically the same. In Case UT9, the greatest value of dissipation is as high as 2.35 × 10−4 m2 s−3, which is essentially the same as that in Case U9 (2.37 × 10−4 m2 s−3).

|

Fig. 8 (a) – (i) Snapshots of the turbulent dissipation rate (ε, unit: m2 s−3) of internal tides and lee waves under coupled flow velocity conditions from U0 = 0.0005 – 0.01 m s−1 at t = 125 s. |

|

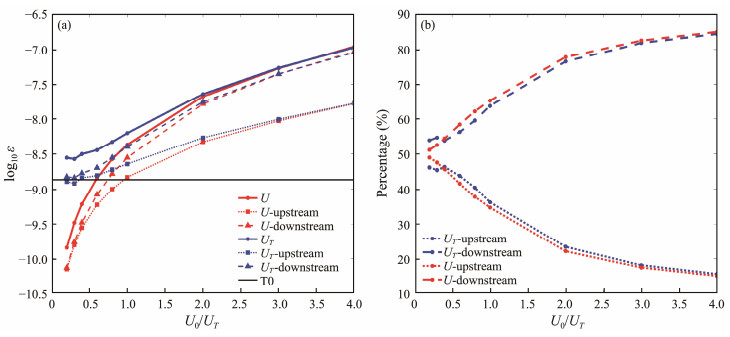

Fig. 9 (a) Area-integrated turbulent dissipation rate (m4 s−3) plot against U0/UT, where the vertical coordinates are in logarithmic form, and (b) the upstream and downstream dissipation results are in percentage form. |

|

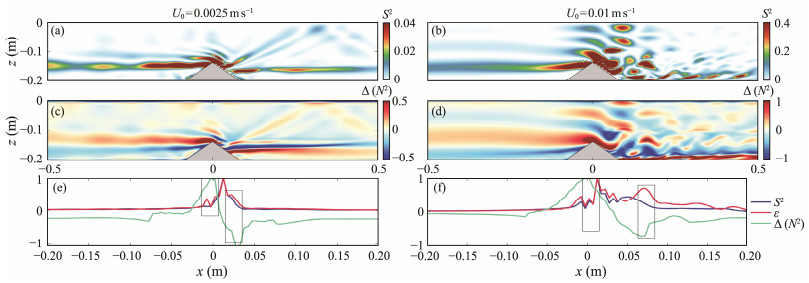

Fig. 10 (a) and (b) Snapshots of shear S2; (c) and (d) buoyancy frequency perturbation ∆(N2) at t = 125 s; (e) and (f) normalized shear, dissipation, and buoyancy frequency perturbation for Case UT6 (left panel) and Case UT9 (right panel), respectively, where N2 is determined by instantaneous value minus the initial N2. The rectangular gray boxes in (e) and (f) denote the dissipation enhancement due to diapycnal perturbation. |

Fig.9(a) shows the results of the area-integrated turbulent dissipation rate within 0.5 m upstream and downstream of the topography. The logarithmic outcomes of the integrated dissipation present a logarithmic increase when only the background flow is included in the analysis. The dissipation at a low background flow velocity resembles that due to the internal tide alone when tidal currents are regarded. However, the upstream and downstream distributions of dissipation are immensely dissimilar. The change between upstream and downstream dissipation slowly rises with the increase in U0.

Fig.9(b) establishes that the upstream and downstream dissipation are similar in Cases U1 – U3 and UT1 – UT3. The existence of internal tide marginally increases the upstream and downstream dissipation difference. The upstream (downstream) energy proportion slowly decreases (increases) from the original ca. 50% with the rise in background flow velocity, and the adjustment is more sensitive at low velocities. When U0/UT ≥ 2, the upstream and downstream dissipation ratio is preserved at 1:4. The influence of the tidal currents increases the upstream (downstream) dissipation ratio (downstream), with a difference of approximately 2% – 3%.

Fig.10 presents the results of velocity shear S2 and buoyancy frequency perturbations ∆(N2) to explain the dissipation mechanism further. The beam remains visible downstream, and the lee wave emerges at the lee side of the topography, as illustrated in Fig.10(a). The flow at the topography peak accelerates downslope as a thin, intensified jet, and a shear arises near the region where the lee wave is generated. The jet compensates for the transport shortage in the blocked layer, which makes the fluid overturn. This condition generates mixing across the isopycnals, transfers energy to the turbulence, and enhances the dissipation.

Fig.10(e) presents the vertical integration results of shear, dissipation, and buoyancy frequency perturbation. The vertical integration outcomes of the three are normalized by dividing the maximum value of their respective integrals. The pattern of dissipation and shear remains fundamentally the same. However, the positions where the value of dissipation is marginally greater than that of the shear relate to the two extreme positions of the buoyancy frequency perturbation. At these two positions (rectangular boxes in Fig.10(e)), diapycnal perturbation also facilitates dissipation but is weaker compared with the velocity shear.

Figs.10(b), 10(d), and 10(f) show that in Case UT9, the beam structure disappears, and the lee wave occupies the downstream. The shear strength near the topography can reach 10 times that of Case UT6. The buoyancy frequency perturbation structure becomes complicated, and the downslope jet is more distinct. The buoyancy frequency perturbation can exceed 1 rad s−2 and results in the total inversion of the isopycnals. Fig.10(f) exhibits how the dissipation peaks that are different from the local shear variations in the blocking area and lee wave development area correspond precisely to the extreme value of the buoyancy frequency perturbations (rectangular boxes in Fig.10(f)). The dissipation is remarkably improved at the downstream location. The main reason for dissipation at this point is local mixing due to the inversion of the isopycnals rather than shear.

4 ConclusionsIn the present paper, the MITgcm numerical model is used to explain the energetics of IWs triggered by diverse flows over the topography systematically. Variations in IW energy, dissipation are compared under three scenarios: barotropic tidal currents alone, background flow alone and their superposition. The main conclusions are as follows:

1) When only background flow exists, streaky lee waves with variations in the upstream and downstream wave fields are generated. The structures are complicated and close to the topography, with upstream blocking and hydraulic control of the downslope jet along the topography. Internal tides propagate in the form of beams at low background flow velocities when superposition cases are considered. However, the influence of Doppler shift results in asymmetrical upstream and downstream beam directions.

2) The modal decomposition outcomes reveal that the influences on the energy distribution of different modes in the upstream and downstream vary in the presence of the background flow. In the upstream, the mode-1 wave energy share declines from 52% to 27%, the mode-2 wave energy share rises from 40% to a maximum of 60%, and the mode-3 energy share increases by about 10%. In the downstream, the energy shares of the first two modes decrease by 15% – 20%, and the energy of the high modes is remarkably enhanced.

3) Dissipation enhancement varies with background flow intensity. At low background flow velocities (Cases UT1 – UT3), the presence of internal tides increases dissipation by one to two orders of magnitude to Cases U1 – U3. The integral difference between upstream and downstream turbulent dissipation rises with background flow velocity and finally stabilizes at about 1:4. The main reason for dissipation is velocity shear. However, as the background flow continues to increase, the isopycnal overturn due to the lee waves and the flow velocity shear jointly influence dissipation.

In this paper, a series of numerical experiments are devised to simulate the wave characteristics generated around topography, highlighting the roles of background flow and barotropic tidal currents in the ocean energy balance. However, compared with the real ocean, this experiment is performed under simplified conditions. For example, Coriolis frequency is vital for the generation of IWs in the real ocean and directly influences the dispersion relation. Future studies should incorporate more complex models to depict the related dynamical processes more realistically.

AcknowledgementThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41876015).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Zenghao Jiang: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing – original draft. Xu Chen: conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing. Jing Meng: data curation, supervision, funding acquisition. Anzhou Cao: validation, writing – review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Aguilar, D. A., Sutherland, B. R., and Muraki, D. J., 2006. Laboratory generation of internal waves from sinusoidal topography. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 53(1-2): 96-115. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2005.09.015 (  0) 0) |

Baines, P. G., 1982. On internal tide generation models. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers, 29(3): 307-338. DOI:10.1016/0198-0149(82)90098-X (  0) 0) |

Bell, T. H., 1975. Topographically generated internal waves in the open ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 80(3): 320-327. DOI:10.1029/JC080i003p00320 (  0) 0) |

Cao, A. Z., Li, B. T., and Lv, X. Q., 2015. Extraction of internal tidal currents and reconstruction of full-depth tidal currents from mooring observations. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 32(7): 1414-1424. DOI:10.1175/JTECH-D-14-00221.1 (  0) 0) |

Chesnokov, A. A., Gavrilyuk, S. L., and Liapidevskii, V. Yu., 2022. Mixing and nonlinear internal waves in a shallow flow of a three-layer stratified fluid. Physics of Fluids, 34(7): 075104. DOI:10.1063/5.0093754 (  0) 0) |

Cusack, J. M., Naveira Garabato, A. C., Smeed, D. A., and Girton, J. B., 2017. Observation of a large lee wave in the drake passage. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 47(4): 793-810. DOI:10.1175/JPO-D-16-0153.1 (  0) 0) |

Doron, P., Bertuccioli, L., Katz, J., and Osborn, T. R., 2001. Turbulence characteristics and dissipation estimates in the coastal ocean bottom boundary layer from PIV data. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 31(8): 2108-2134. DOI:10.1175/1520-0485(2001)031<2108:TCADEI>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Dossmann, Y., Rosevear, M. G., Griffiths, R. W., Hogg, A. M., Hughes, G. O., and Copeland, M., 2016. Experiments with mixing in stratified flow over a topographic ridge. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121(9): 6961-6977. DOI:10.1002/2016JC011990 (  0) 0) |

Dossmann, Y., Shakespeare, C., Stewart, K., and Hogg, A. M., 2020. Asymmetric internal tide generation in the presence of a steady flow. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125(10): e2020JC016503. DOI:10.1029/2020JC016503 (  0) 0) |

Garrett, C., 2003. Internal tides and ocean mixing. Science, 301(5641): 1858-1859. DOI:10.1126/science.1090002 (  0) 0) |

He, X., Chen, X., Li, Q., Xu, T., and Meng, J., 2023. Numerical simulations and an updated parameterization of the breaking internal solitary wave over the continental shelf. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 128(11): e2023JC019975. DOI:10.1029/2023JC019975 (  0) 0) |

He, Y., and Lamb, K. G., 2021. Mode-one internal tides propagating across a geostrophic current. Physics of Fluids, 33(9): 096606. DOI:10.1063/5.0064964 (  0) 0) |

Klymak, J. M., Legg, S. M., and Pinkel, R., 2010. High-mode stationary waves in stratified flow over large obstacles. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 644: 321-336. DOI:10.1017/S0022112009992503 (  0) 0) |

Kurkina, O. E., Kurkin, A. A., Pelinovsky, E. N., Semin, S. V., Talipova, T. G., and Churaev, E. N., 2016. Structure of currents in the soliton of an internal wave. Oceanology, 56(6): 767-773. DOI:10.1134/S0001437016060072 (  0) 0) |

Lamb, K. G., 1994. Numerical experiments of internal wave generation by strong tidal flow across a finite amplitude bank edge. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 99(C1): 843. DOI:10.1029/93JC02514 (  0) 0) |

Legg, S., 2021. Mixing by oceanic lee waves. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 53(1): 173-201. DOI:10.1146/annurev-fluid-051220-043904 (  0) 0) |

Marshall, J., Adcroft, A., Hill, C., Perelman, L., and Heisey, C., 1997. A finite-volume, incompressible Navier Stokes model for studies of the ocean on parallel computers. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 102(C3): 5753-5766. DOI:10.1029/96JC02775 (  0) 0) |

Mayer, F. T., and Fringer, O. B., 2017. An unambiguous definition of the Froude number for lee waves in the deep ocean. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 831: R3. DOI:10.1017/jfm.2017.701 (  0) 0) |

Mayer, F. T., and Fringer, O. B., 2020. Improving nonlinear and nonhydrostatic ocean lee wave drag parameterizations. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 50(9): 2417-2435. DOI:10.1175/JPO-D-20-0070.1 (  0) 0) |

Melet, A., Hallberg, R., Legg, S., and Nikurashin, M., 2014. Sensitivity of the ocean state to lee wave-driven mixing. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 44(3): 900-921. DOI:10.1175/JPO-D-13-072.1 (  0) 0) |

Munk, W., and Wunsch, C., 1998. Abyssal recipes Ⅱ: Energetics of tidal and wind mixing. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅰ: Oceanographic Research Papers, 45(12): 1977-2010. DOI:10.1016/S0967-0637(98)00070-3 (  0) 0) |

Nikurashin, M., and Ferrari, R., 2010a. Radiation and dissipation of internal waves generated by geostrophic motions impinging on small-scale topography: Theory. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 40(5): 1055-1074. DOI:10.1175/2009JPO4199.1 (  0) 0) |

Nikurashin, M., and Ferrari, R., 2010b. Radiation and dissipation of internal waves generated by geostrophic motions impinging on small-scale topography: Application to the southern ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 40(9): 2025-2042. DOI:10.1175/2010JPO4315.1 (  0) 0) |

Nikurashin, M., Ferrari, R., Grisouard, N., and Polzin, K., 2014. The impact of finite-amplitude bottom topography on internal wave generation in the southern ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 44(11): 2938-2950. DOI:10.1175/JPO-D-13-0201.1 (  0) 0) |

Scott, R. B., Goff, J. A., Naveira Garabato, A. C., and Nurser, A. J. G., 2011. Global rate and spectral characteristics of internal gravity wave generation by geostrophic flow over topography. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 116(C9): C09029. DOI:10.1029/2011JC007005 (  0) 0) |

Shakespeare, C. J., 2020. Interdependence of internal tide and lee wave generation at abyssal hills: Global calculations. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 50(3): 655-677. DOI:10.1175/JPO-D-19-0179.1 (  0) 0) |

Sun, H., Yang, Q. X., Zheng, K. W., Zhao, W., Huang, X. D., and Tian, J. W., 2022. Internal lee waves generated by shear flow over small-scale topography. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 127(6): e2022JC018547. DOI:10.1029/2022JC018547 (  0) 0) |

Trossman, D. S., Arbic, B. K., Richman, J. G., Garner, S. T., Jayne, S. R., and Wallcraft, A. J., 2016. Impact of topographic internal lee wave drag on an eddying global ocean model. Ocean Modelling, 97: 109-128. DOI:10.1016/j.ocemod.2015.10.013 (  0) 0) |

Winters, K. B., 2016. The turbulent transition of a supercritical downslope flow: Sensitivity to downstream conditions. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 792: 997-1012. DOI:10.1017/jfm.2016.113 (  0) 0) |

Winters, K. B., and Armi, L., 2012. Hydraulic control of continuously stratified flow over an obstacle. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 700: 502-513. DOI:10.1017/jfm.2012.157 (  0) 0) |

Winters, K. B., and Armi, L., 2014. Topographic control of stratified flows: Upstream jets, blocking and isolating layers. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 753: 80-103. DOI:10.1017/jfm.2014.363 (  0) 0) |

Wright, C. J., Scott, R. B., Ailliot, P., and Furnival, D., 2014. Lee wave generation rates in the deep ocean. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(7): 2434-2440. DOI:10.1002/2013GL059087 (  0) 0) |

Yang, L., Nikurashin, M., Hogg, A. M., and Sloyan, B. M., 2018. Energy loss from transient eddies due to lee wave generation in the southern ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 48(12): 2867-2885. DOI:10.1175/JPO-D-18-0077.1 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Z., Alford, M. H., Girton, J. B., Rainville, L., and Simmons, H. L., 2016. Global observations of open-ocean mode-1 M2 internal tides. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 46(6): 1657-1684. DOI:10.1175/JPO-D-15-0105.1 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Z., Alford, M. H., MacKinnon, J. A., and Pinkel, R., 2010. Long-range propagation of the semidiurnal internal tide from the Hawaiian Ridge. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 40(4): 713-736. DOI:10.1175/2009JPO4207.1 (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24