2) Sanya Oceanographic Institution, Ocean University of China, Sanya 572024, China

Microorganisms, algae and animals adhere to and accumulate on the surface of marine facilities in a process known as marine biofouling (AF) (YebraKiil et al., 2004; Callow and Callow, 2011). Marine biofouling accelerates the corrosion of metallic substrates, increases the hydrodynamic drag of ships, causes marine equipment to malfunction, and affects aquaculture systems (Schultz, 2007; Schultz et al., 2011; Lacoste and Gaertner-Mazouni, 2015; Bannister et al., 2019). The most economical and effective approach to combatting biofouling is to apply AF coatings, especially self-polishing coatings containing tributyltin (TBT) (Sousa et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2020). However, TBT has been banned altogether by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) since 2008 due to its severe effects on the non-target species such as dolphins (Lejars et al., 2012; Ciriminna et al., 2015). Therefore, the primary mission for marine antibiofouling is to develop environmentally friendly materials, including self-polishing polymers (Yonehara et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2017), low surface energy materials (van Zoelen et al., 2014), biodegradable materials (Ma et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2018), amphiphilic polymers (Tsibouklis and Nevell, 2003; Jiang and Cao, 2010), zwitterionic materials (Chen et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2012), proteinresistant coatings (Banerjee et al., 2011) and self-generating hydrogels (Xie et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2016). These materials have a certain AF performance according to relevant research, but they are not widely used because of their imperfections in the marine environment.

Self-polishing coatings are the most economical, effective and widely used AF technology, and novel tin-free AF coatings achieve similar AF performance and lower toxicity to organic tin-based AF paints without a significant cost increase (Chambers et al., 2006; Antizar-Ladislao, 2008; Wu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). Acrylic polymers are common hydrolysable polymers. Yonehara et al. (2001) have suggested that the erosion rates of AF coatings containing acrylic copolymer are related to the hydrophilicity and zinc acrylate content. Kiil et al. (2001) analyzed the hydrolysis rate and erosion rate of AF coatings by detailed mathematical models and rotating experiments and found that the hydrolysis rate can be effectively controlled by adjusting the zinc acrylate content, which plays a decisive role in the effective release of biocides. Yonehara et al. (2001) also pointed out that paints tended to be less flexible as the zinc acrylate content increased. In addition, the hydrolysis of the acrylate resin pendant groups gradually removes them from the surface of the coating, reducing both biological attachment and fuel consumption. Therefore, continuous and stable renewal of self-polishing AF coatings can effectively increase their service life (Chambers et al., 2006). However, developing the antifouling resins and coatings with the above excellent performance is not an easy task, and no companies or research institutions have been truly successful thus far.

EA and BA improve the flexibility of the resin as soft monomers, the hydrophilic carboxyl groups of AA and MAA can provide better water solubility. These monomers are cheap, easy to polymerize and provide better mechanical strength (Ma et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2020). In this work, the long-term AF copolymer (ACZn-x) was designed and synthesized by free radical polymerization and dehydration condensation based on the monomers synergistic effect, and marine AF coatings were prepared based on it. Hydrolysis of the side chains produces continuously renewed surfaces, and the broken low-toxic small molecules are less harmful to the environment. The comprehensive performance was evaluated by static simulation, antibacterial, anti-algae and marine field tests. Our aim is to develop an inexpensive, controllable hydrolysis and environmentally friendly self-polishing AF material.

2 Experiment 2.1 MaterialsEthyl acrylate (EA), butyl acrylate (BA), acrylic acid (AA), methacrylic acid (MAA), butyl alcohol, butyl acetate and xylene were all purchased from Datang Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China. 2, 2-Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), dodecyl mercaptan, zinc oxide (ZnO) and benzoic acid were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Nutrient agar and nutrient broth were purchased from Beijing Land Bridge Technology Co., Ltd., sodium chloride was purchased from Tainjin Dingshengxin Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., and all of the above reagents were used as received. Natural seawater (NSW) was filtered and sterilized at 121℃ prior to use.

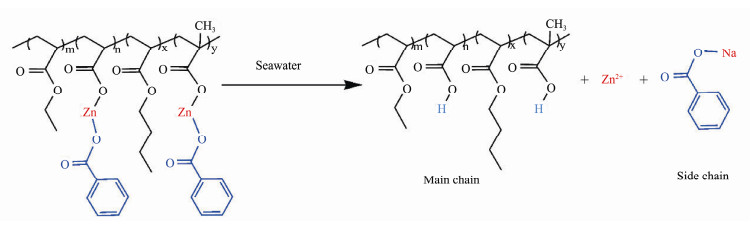

2.2 Preparation of ACZn-xThe strategy for synthesizing ACZn-x is schematically described in Scheme 1. Typically, 120 g of mixed solvent (xylene: butyl alcohol = 4:1, wt.%) and 0.32 g of dodecyl mercaptan were added to a three-necked flask with a blender, condensation tube and thermometer at 85℃. A mixture of EA, BA, AA, MAA and 0.64 g AIBN was introduced into the above flask in 10 portions that were added every 15 min. The polymerization was carried out at 85℃ for 2.5 h, yielding a colorless or yellowish acrylate polymer (abbreviated as AP). Next, 162 g of AP, 19.7 g of ZnO, 24.3 g of benzoic acid and 43 g of mixed solvent (xylene: butyl alcohol: butyl acetate = 4.4:1:10.6, wt %) were introduced into another three-necked flask at 85℃ for several hours until the mixture was transparent or translucent to obtain the zinc-based acrylate copolymers, which were named ACZn-x, where x is the molar content of ZnO. The molecular compositions and characterization data of ACZn-x are summarized in Table 1. It is worth noting that the viscosity of the resin is directly proportional to the content of ZnO, which can roughly reflect the molecular weight of macromolecules. The molecular weight of the resin used in AF coatings is not too large or cross-linked, and the resin with moderate viscosity indicates that the resin has better fluidity and film formation.

|

|

Table 1 Molecular compositions and characterization of the ACZn-x |

The structure of ACZn-x was determined by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (NICOLET AVATAR-360, KBr disc method) and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1HNMR) spectroscopy (Bruker AVAN CE-III NMR (600 MHz) with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as the solvent and tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed by a thermal analyzer (Netzsch STA 449 PC/TG) at a heating rate of 10℃min−1 under N2 at 25 – 800℃. The viscosity of ACZn-x was measured by a Brookfield Viscometer at 25℃. The surface morphology and roughness were characterized using a LEXT OLS4000 laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM). Sterilization of all experimental equipment was completed in an MLS-3750 autoclave sterilizer (Sanyo, Japan), the cultivation of bacteria was completed in an HZQF160 incubator shaker (Harbin Donglian company), and the cultivation of algae was completed in an MLR-350H versatile environmental test chamber (Sanyo, Japan).

2.4 Self-Polishing Performance AnalysisThe self-polishing ability of ACZn-x was determined in static NSW at room temperature. The copolymers were evenly coated on the ABS panel (100 mm × 80 mm × 2 mm) with a coating thickness of approximately 100 μm and put in the ventilated place to dry naturally to constant weight (W0). The completely dried samples were incubated in static NSW, removed every 7 d, rinsed with distilled water (Wwett), and dried to a constant dry weight (Wdryt).

The mass loss was calculated according to the following equation:

| $ \text { Mass loss }\left(\mathtt{μ} \mathrm{g} \mathrm{cm}^{-2} \mathrm{~d}^{-1}\right)=\frac{W_{\text {dry }} t-W_{\text {dry }}(t+7)}{7 S}. $ | (1) |

The water absorption was calculated according to the following equation:

| $ {\text{Water absorption }}({\mathtt{μ} \text{g c}}{{\text{m}}^{ - {\text{2}}}}{{\text{d}}^{ - {\text{1}}}}) = \frac{{{W_{{\text{wet}}}}t - {W_{{\text{dry}}}}t}}{{7S}}, $ | (2) |

where Wwett, Wdryt and S represent the wet weight and dry weight of the panel at time t and the area of the ABS panel, respectively. To understand the self-polishing properties of copolymers in detail, the surface morphology and roughness of each cycle was characterized by a LEXT OLS4000 LSCM. Each sample was tested three times.

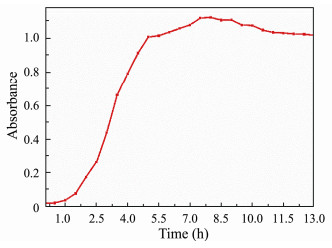

2.5 Antibacterial Activity EvaluationAntibacterial assays of the ACZn-x copolymers were evaluated for S. aureus and E. coli (Fernandes et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2017), which were provided by the microbiology laboratory at the College of Marine Life Sciences, Ocean University of China. All bacteria with good recovery at 37℃ were added to sterile fluid nutrient medium (nutrient broth: 33 g, distilled water: 1000 mL, sterilized for 20 min at 121℃), cultivated to the index level (Fig.1) and diluted to a lower concentration. Two hundred microliters of bacterial suspension were added to the control glass and coating surface for continuous culture for another 24 h and then diluted to a reasonable concentration range (approximately 108 CFU mL) by the tenfold dilution method. Then, 200 µL of the aforementioned bacterial suspension was added to the solid medium and spread on the plate to ensure complete absorption, and each sample was tested 5 times. After incubation for 20 h at 37℃, the colonies were counted.

The antibacterial activity was calculated as follow:

| $ R = \frac{{{N_{\text{0}}} - {N_i}}}{{{N_{\text{0}}}}} \times 100\% {\text{ }}, $ | (3) |

where R is the bacteriostasis rate (%) and N0 and Ni represent the number of bacterial colonies in the blank control sample and the modified sample, respectively.

|

Fig. 1 Growth curves of E. coli. |

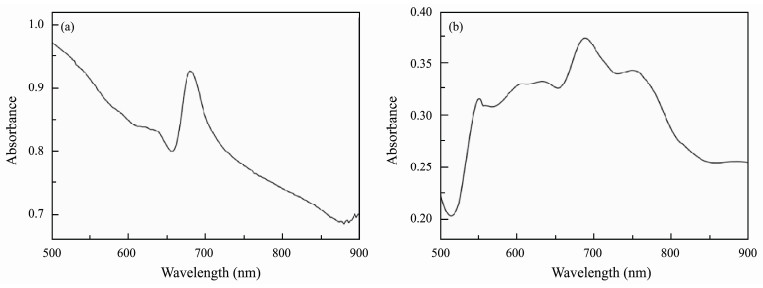

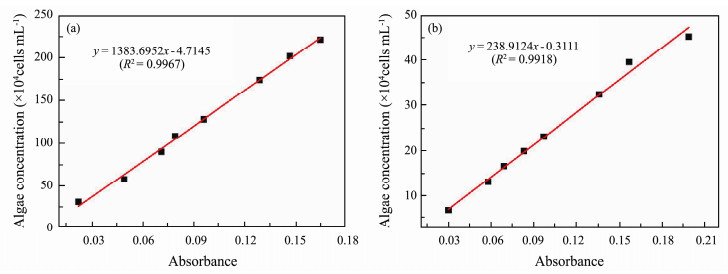

The anti-algae activity of resins was carried out by N. closterium and P. subcordiformis (Xu et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015), which were provided by the species room of Ocean University of China. After filtering some natural seawater and sterilization at 121℃, various nutrients and algae were added to seawater cooled to 20℃ to form algal nutrient solutions (Table 2), which were cultured in an artificial climate incubator (temperature: 21℃, light intensity: 4000 lux, light to dark ratio of 12 h: 12 h). After one week, the cells were diluted with nutrient solution to measure their absorbance by UV/visible spectroscopy at the optimum wavelength (Fig.2) and different concentrations (determined by blood plate counting). The absorbance-cell concentration curve was made according to the values of absorbance and cell concentration (Fig.3). Next, 25 mL of diluted algal solution at the same concentration was placed into a flat weighing bottle coated with dry acrylate resin. The absorbance of the algal solution was tested every 12 h, the algal concentration under this absorbance was calculated according to the absorbance-cell concentration curve, and the time-absorbance-algae concentration curve was plotted to determine the inhibitory effect of these resins on the growth of algae.

|

|

Table 2 Formula of nutrient solution |

|

Fig. 2 Wavelength scanning of (a) N. closterium and (b) P. subcordiformis. |

|

Fig. 3 Standard work curves of (a) N. closterium and (b) P. subcordiformis. |

The anti-algae rate was calculated as follow:

| $ R=\left(\frac{A_0-A_i}{A_0}\right) \times 100 \% $ | (4) |

where R is the anti-algae rate (%) and A0 and Ai represent the number of algae in the control and modified samples, respectively.

2.7 Marine Field TestMarine field tests can reflect the real biofouling degree of copolymers and coatings in marine environments, which is an important means to evaluate AF conditions. This test was performed at Jiaozhou Bay, Qingdao, China, following GB5370-2007 on January 21, 2018. All the tested resins and marine coatings with the tested resins (Table 3) were evenly coated on poly(vinyl chloride) substrates and submerged at a depth of 0.2 – 2 m off floating rafts. Every several months, the sample panels were taken from seawater, observed and photographed, and then immediately replaced in the marine environments.

|

|

Table 3 Composition of marine antifouling coatings containing ARZn-x copolymers |

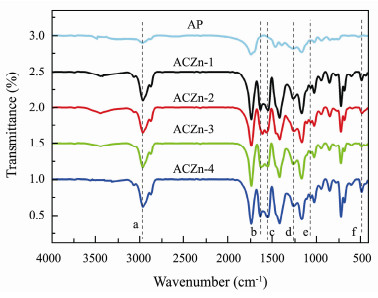

AP and the ACZn-x with hydrolysable side chains were designed and synthesized according to Scheme 1, and these chemical structures were characterized by FTIR and 1H NMR (Figs.4, 5). As shown in Fig.1, no C=C peaks were observed in the 1630 – 1620 cm−1 range in the spectrum of AP sample, indicating that AP was synthesized by polymerization of small molecules. For all samples, there is a very strong -CH2CO- peak at 2963.7 cm−1 and symmetric and asymmetrical stretching oscillations of -COO- at 1064.3 cm−1 and 1259.1 cm−1, respectively. A small peak at 3293.5 cm−1 in all samples was ascribed to the stretching vibrations of the O-H, indicating that some carboxyl groups are still present in ACZn-x; in other words, the monomers in AP do not fully react. In the ACZn-x spectrum, the peaks at 1626 cm−1 and 1545 cm−1 represent the asymmetric stretching vibration of benzoate and the stretching vibration of the benzoate frame, and the peak at 489 cm−1 in ACZn-x is attributed to the stretching vibration of Zn-O, which proves that zinc was successfully introduced into the resin system. All the above information shows that ACZn-x materials were synthesized by the reaction of ZnO with AP and benzoic acid.

|

Fig. 4 FTIR spectra of AP and ACZn-x. a, 2963.7 cm−1; b, 1626 cm−1; c, 1545 cm−1; d, 1259.1 cm−1; e, 1064.3 cm−1; f, 489 cm−1. |

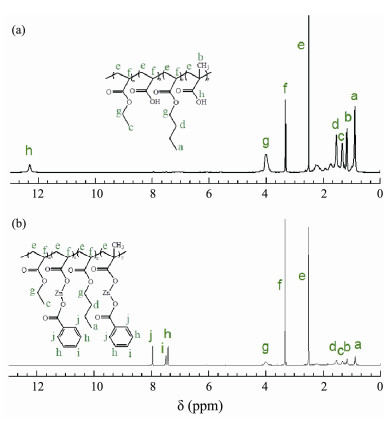

Fig.5 shows the 1H NMR spectra of AP and ACZn-x. Complete displacement of chemical shifts associated with the protons in the main chain of AP at 2.48 and 3.32 ppm indicates successful polymerization reaction of C=C in acrylic monomers. The characteristic signals of AP (Fig. 5a) appear at 12.29 ppm, arising from the methyne proton associated with the carboxyl group, which contributes to the peaks at 0.88 – 1.51 ppm and 4.01 ppm, formed from the protons of the methyl and methylene groups in AP and ACZn-x (Fig.5). As shown in Fig.5b, the new signal characteristics at 7.39 – 7.97 ppm resulted from the addition of protons to benzene in ACZn-x. Hence, the successful copolymerization of AP and ACZn-x was confirmed by 1H NMR.

|

Fig. 5 1HNMR spectra of (a) AP and (b) ACZn-x in DMSO. |

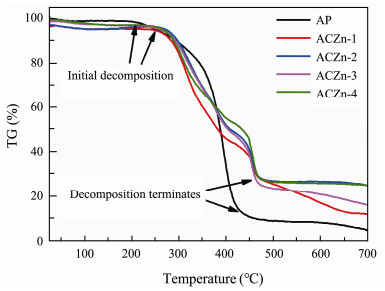

Fig.6 illustrates the TG curves of AP and ACZn-x containing zinc benzoate hydrolyzing side chains under a N2 atmosphere (Jiang et al., 2020). There are two obvious stages in the process of thermal decomposition for pure AP. The first stage at 30 – 95℃ results from the evaporation of some impurities, such as oligomers and absorbed water, and the other stage at 195 – 490℃ is caused by the hemolytic scission of chains due to H-H bonds and random scission of the macromolecule backbone (Ferriol et al., 2003). In contrast with the pure AP sample, ACZn-x has three distinct decomposition processes, which occur at 40 – 120℃, 250 – 400℃ and 430 – 480℃. The first and second stages of ACZn-x decomposition are very similar to the thermal decomposition process of the pure AP sample; they could be due to the evaporation of some impurities and the scission of the H-H bond and the macromolecule backbone, respectively. The third stage that occurs from 430℃ to 480℃ significantly deviates from that of the AP sample and may be associated with the carbonization of zinc benzoate on the side chains of the ACZn-x. The temperature at which the initial and terminal decomposition of the ACZn-x occurs is higher than that of pure AP, and the ACZn-x has more residual carbon than pure AP, which indicates that the thermal stability of ACZn-x is improved, especially that of the ACZn-2.

|

Fig. 6 TG curves of AP and ACZn-x. |

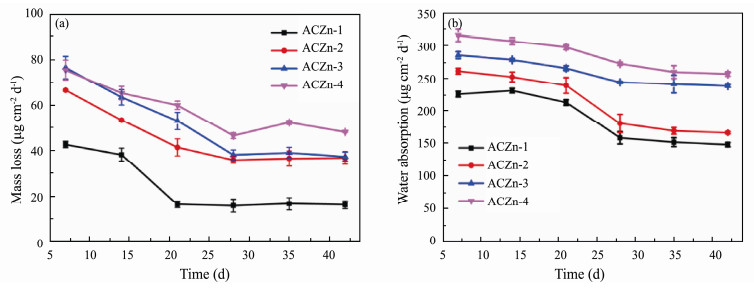

Fig.7 shows the time dependence of the mass loss and water absorption of ACZn-x in static NSW at room temperature. In Fig.7a, after being immersed in NSW for 7 d, all resins began to suffer varying degrees of mass loss, indicating that all resins hydrolyzed in NSW due to the ion exchange reaction of zinc acrylate resin with sodium ions in seawater; this reaction leads to the shedding of zinc benzoate side chains from the main backbone of zinc acrylate copolymer, and the weights of the resins decrease (Yebra et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2017). The maximum mass loss of AcZn-4 (an estimated 47 μg cm−2 d−1) and the minimum mass loss of ARZn-1 (an estimated 16 μg cm−2 d−1) are noted from the overall trend, which reveals the fastest hydrolysis rate of AcZn-4 and the slowest hydrolysis of ARZn-1 in all resins. The hydrolysis rate of the resin is related to the zinc ester groups in the copolymers. Moreover, the earlier hydrolysis is faster than the later hydrolysis in NSW, so after the resin had soaked for a while, the mass loss of the resin began to slow. It has been proven that our novel ACZn-x can achieve relatively stable self-polishing in NSW if the number of zinc ester groups is adjusted. The water absorption properties of all ACZn-x in Fig.7b show that all the resins have varying degrees of water absorption in NSW because the hydrophilic carboxyl group is formed by hydrolysis on the side chains of the acrylate resins and a hydration layer is produced on the surface. The water absorption of ACZn-4 and ACZn-3 is greater than that of ACZn-2 and ACZn-1 because the former contains more hydrolysable zinc ester groups. After soaking for a while in NSW, the water absorption of resins began to decrease; this phenomenon was consistent with the mass loss trend. The hydrolysis of resins may be rapid and unstable in the initial stage of static immersion, increasing the number of hydrophilic groups on the surface and reaching dynamic equilibrium at the side chains in the later stage. In addition, the absorbability of the resin surface leads to swelling of the coating. The resin becomes more swollen with increasing water absorption and the mechanical properties of the resins decrease, which reduces the adhesion between the resin coating and the substrate, causing the coating to obvious wrinkles and the easily fall off. In brief, maintaining reasonable water absorption can improve the mechanical properties of the resin.

|

Fig. 7 Time dependence of mass loss (a) and water absorption (b) of ACZn-x in static NSW. |

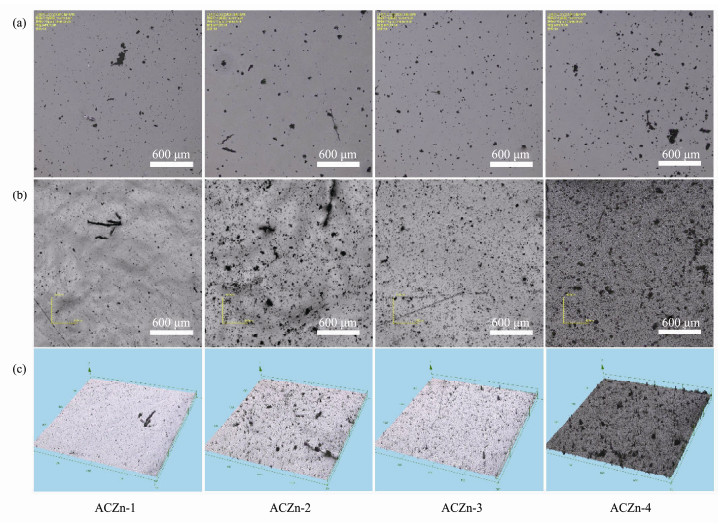

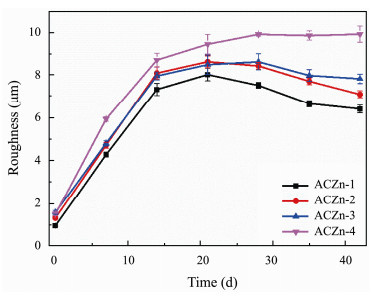

Coating morphology and roughness are important parameters that affect biofouling behavior and can change the contact ability of marine fouling at the material surface (Kumar et al., 2018; Dai et al., 2019). Surface morphology images and roughness of the ACZn-x copolymers in static NSW obtained by by LEXT OLS4000 LSCM are shown in Figs.8, 9. Before immersion, the surfaces of all samples were smooth and clean, with only a few black spots on the surface shown in Fig.8, and the roughness (Ra) was less than 1.5 μm. After immersion for 6 cycles in static NSW, the surface of the 2D diagram in Fig.8b shows that all coatings have obvious wrinkles and more black spots, and the 3D images in Fig.8c show that the surface of the coatings presents many jagged and uneven impurities. This uneven state is more pronounced with increasing zinc content, indicating that the surface polishing rate is too fast to form a smooth surface. The time dependence of the roughness of the ACZn-x copolymers in Fig.9 shows that the surface has a very small roughness (Ra ≤ 1.5 μm) before any test. The polymers first increase and then tend to be stable with prolonged immersion time, which is mainly related to the hydrolyzing structure of the side chain of zinc-based acrylate resins. The trend of the change in surface roughness is similar to that of the mass loss.

|

Fig. 8 Surface morphology images of the ACZn-x copolymers by LEXT OLS4000 LSCM. (a), before any tests; (b), 2D; (c), 3D diagrams after 6 cycles of the static simulation experiment. |

|

Fig. 9 Time dependence of roughness for the ACZn-x copolymers after immersion in static NSW. |

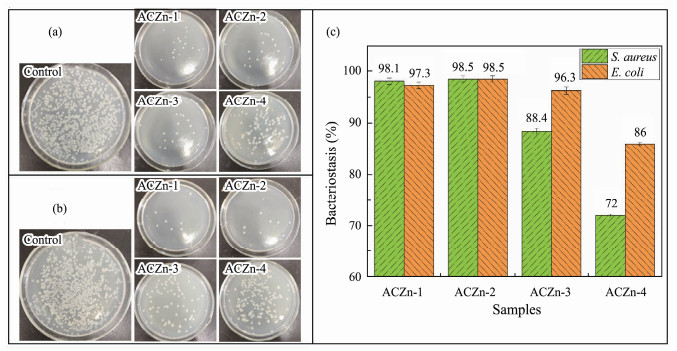

The attachment of bacteria on the contaminated surface is conducive to the formation of biofilms in the biological fouling process (Achinas et al., 2019). The development of excellent AF coatings must first reduce the occurrence of the microbial biofilm process. Fig.10 shows the antibacterial efficiency of ACZn-x copolymers on S. aureus and E. coli measured by the spread plate test after 20 h of incubation at 37℃. Here, we used a blank glass sheet without the ACZn-x samples as a control and the resin coatings containing the ACZn-x samples as the experimental group. There were relatively few bacterial colonies on the surfaces of the experimental groups compared to that of the control group. Therefore, it can be observed from the number of live bacteria on the plates that the ACZn-x samples have obvious antibacterial properties against S. aureus and E. coli, and the inhibition rate of ACZn-x for S. aureus was better than that for E. coli. The relative antibacterial properties of ACZn-x for S. aureus and E. coli, as shown in Fig.10c, are ACZn-2 > ACZn-1 > ACZn-3 > ACZn-4 (S. aureus: 98.5 > 97.3 > 96.3 > 86; E. coli: 98.5 > 98.1 > 88.4 > 72). ARZn-2 has the strongest antibacterial properties against S. aureus and E. coli.

|

Fig. 10 Antibacterial images of ACZn-x on (a) S. aureus, (b) E. coli., and (c) bacteriostasis of the ACZn-x. |

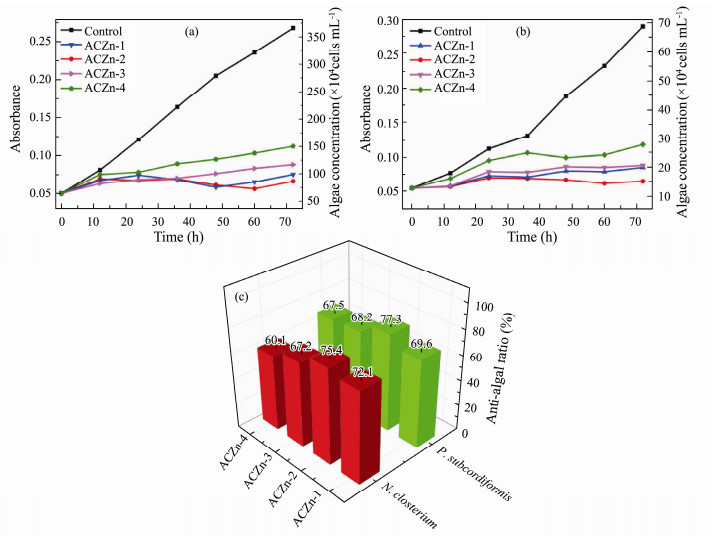

The attachment of marine algae greatly affects the speed of marine ships and the normal use of equipment, so excellent AF coatings should ideally have the ability to inhibit the growth of algae (Finlay, 2002). In Fig.11, the time-absorbance-algal concentration curves of ACZn-x on N. closterium and P. subcordiformis are plotted. The ACZn-x samples had a good inhibitory effect on N. closterium and P. subcordiformis, as shown in Figs.11a, b, and their anti-algae rates were above 60%. The best anti-algal activity was 75.4% and 77.3% on N. closterium and P. subcordiformis, respectively (Fig.11c). Moreover, ACZn-2 and ACZn-1 had stronger inhibitory effects on N. closterium and P. subcordiformis than ACZn-3 and ACZn-4. The relative algal inhibition of N. closterium and P. subcordiformis by the four resins was ACZn-2 > ACZn-1 > ACZn-3 > ACZn-4 (N. closterium: 75.4 > 72.1 > 67.2 > 60.1; P. subcordiformis: 77.3 > 69.6 > 68.2 > 67.5). ARZn-2 had the best algae inhibition on N. closterium and P. subcordiformis compared to the other ACZn-x.

|

Fig. 11 Time-absorbance-algae concentration curve of ACZn-x on (a) N. closterium, (b) P. subcordiformis, and (c) the anti-algal ratio of ACZn-x. |

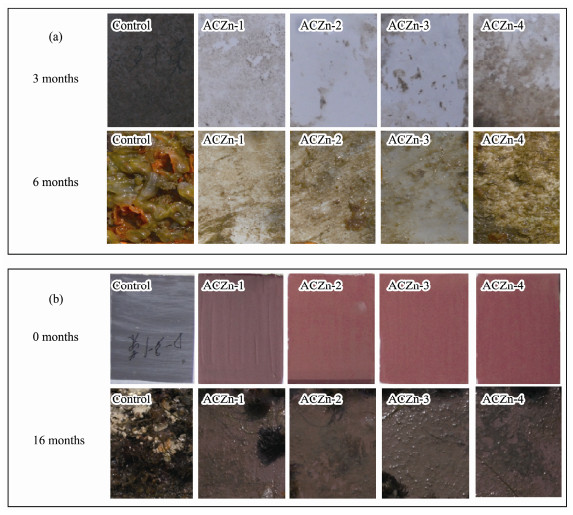

Fig.12 shows the AF performances of the ARZn-x copolymers and marine coatings with ARZn-x copolymers in Jiaozhou Bay, Qingdao, China. The control panel without any resins or coatings is covered by a layer of biological silt, mollusks containing the larva of barnacles, mussels, and macroalgae and calcified fouling organisms after 3, 6 and 16 months, respectively, which indicates the presence of severe biological fouling in the testing site. The panels coated with ACZn-x copolymers were covered with little biological silt after immersion for 3 months, and these panels were covered with some biological silt and a small amount of multicellular organisms after 6 months. Similarly, the AF coatings with the ACZn-x copolymers that were immersed in the marine environment for 16 months had a small amount of biological mucus and silt on their surfaces. This result indicates that the ACZn-x copolymers we designed and synthesized have obvious inhibitory effects on marine biofouling. The zinc-based acrylate resins were washed with seawater in a marine environment, and the zinc benzoate side chain broke off from the acrylic copolymer backbone into the marine environment. Additionally, the hydrophilic surface was enhanced, which was conducive to further hydrolysis of the resin, and the fouling organisms attached to the coating surface also fell off. As shown in Fig.12, the fouling degree of ACZn-4 was much higher than that of ACZn-1, ACZn-2 and ACZn-3, which indicates that when the carboxyl content reached 40%, the antifouling ability of the resin was reduced.

|

Fig. 12 Typical surface antifouling images of the (a) ARZn-x copolymers and (b) marine coatings with ARZn-x copolymers after immersion in seawater in Jiaozhou Bay, Qingdao, China, over different time periods. |

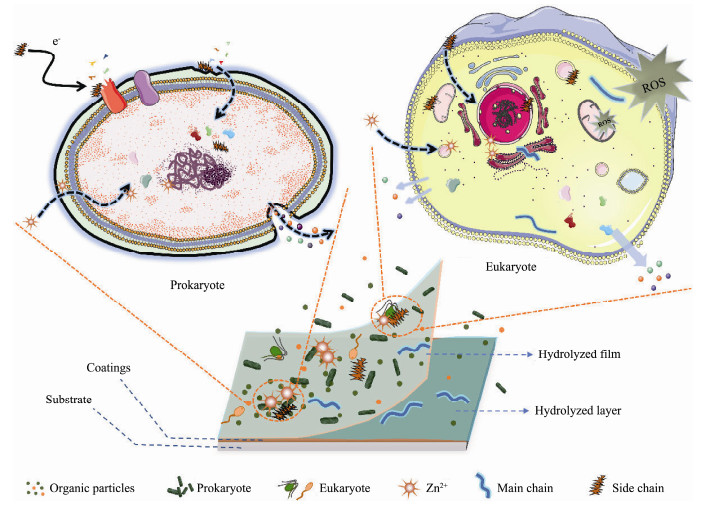

The hypothetical mechanisms of the antifouling action of ACZn-x and marine coatings containing ACZn-x resins are described in Fig.13. The AF properties of ACZn-x copolymers and the corresponding marine coatings can be attributed to their ability to repel organisms or destroy cellular structures. Zinc-based acrylic copolymers immersed in seawater or marine environments have hydrolytic properties, and their hydrolysis process is shown in Fig.14. Some of the microbial membranes (bacteria, algae and protozoan larvae) that attached to the coating surface can be dissolved in the marine environment with the hydrolysis of the ACZn-x copolymer, and the smooth hydrated layer produced by hydrolysis further prevents new organisms from attaching. For prokaryotes, such as bacteria, the negatively charged benzoate adsorbs to their cell wall surfaces and destroys the cell structure, leading to a decrease in the electric potential of the cell membrane and impairment of the function of the intracellular proton pump. Additionally, Zn2+ and benzoates enter the cell and absorb on the plasma membrane to interfere with proteins and DNA, causing cytoplasm to leak and eventually leading to cell death (Di Pasqua et al., 2007; Formigari et al., 2007; Arokiyaraj et al., 2017). The differences in the cell wall structures and the abilities of gram-positive bacteria (such as S. aureus) and gram-negative bacteria (such as E. coli) to resist harmful substances result in different cell mortality rates and death times (Kenawy et al., 2007). For eukaryotes, such as algae and protozoans, Zn2+ and benzoates attach to the surface of the cell wall and cell membrane to perforate the membrane, and intrusion of oil into the cell can reduce the mitochondrial membrane potential and promote mitochondrial depolarization. Simultaneously, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced under the influence of Zn2+ cause mitochondrial respiratory disorders, resulting in the easier leakage of intracellular proteins, cytochrome and Ca2+. Zn2+ and benzoates entering the cell interfere with the balance of trace elements such as Ca2+ in the cell. Eventually, leakage and imbalance of components within the cell can lead to cell death (Hepler, 2005; Bakkali et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2021). In addition, large amounts of antifoulants in marine AF coatings can more directly kill microorganisms on the coating surface and have a more durable and effective antifouling ability (Xie et al., 2020).

|

Fig. 13 Hypothetical mechanisms of the antifouling action of the ACZn-x copolymers and marine coatings under marine conditions. |

|

Fig. 14 Hydrolytic process of the ACZn-x copolymers. |

A series of ACZn-x copolymers were designed and synthesized based on a synergistic AF strategy. These copolymers can produce relatively stable hydrolysis in static artificial seawater, and the hydrolysis rate increases with an increase in the molar ratio of ZnO. In addition, we studied the antibacterial and anti-algae activities of ACZn-x polymers in the laboratory, and their antibacterial rate was above 70% and the anti-algae rate was above 60%. In particular, the antibacterial rates of ACZn-1 and ACZn-2 were above 97%, and their anti-algae rate was above 69%. Marine field tests showed that these resins have excellent AF performance for more than 6 months in marine environments, and the corresponding coating still showed good AF ability after immersion for 16 months. Notably, the AF mechanisms of these copolymers have been described. The above experimental results provide a new opportunity for the preparation of long-lasting AF coatings.

AcknowledgementsThis project was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project (No. 2019YFC0312101), the Scientific Research Project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City Administration (No. SKJC-2020-01-015), and the Hainan Provincial Key Research and Development Project (No. ZDYF2021GXJS029).

Achinas, S., Charalampogiannis, N., and Euverink, G. J. W., 2019. A brief recap of microbial adhesion and biofilms. Applied Sciences, 9(14): 2801. DOI:10.3390/app9142801 (  0) 0) |

Antizar-Ladislao, B., 2008. Environmental levels, toxicity and human exposure to tributyltin (TBT)-contaminated marine environment. A review. Environment International, 34(2): 292-308. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2007.09.005 (  0) 0) |

Arokiyaraj, S., Vincent, S., Saravanan, M., Lee, Y., Oh, Y. K., and Kim, K. H., 2017. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Rheum palmatum root extract and their antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol, 45(2): 372-379. DOI:10.3109/21691401.2016.1160403 (  0) 0) |

Bakkali, F., Averbeck, S., Averbeck, D., and Idaomar, M., 2008. Biological effects of essential oils – A review. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 46(2): 446-475. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106 (  0) 0) |

Banerjee, I., Pangule, R. C., and Kane, R. S., 2011. Antifouling coatings: Recent developments in the design of surfaces that prevent fouling by proteins, bacteria, and marine organisms. Advanced Materials, 23(6): 690-718. DOI:10.1002/adma.201001215 (  0) 0) |

Bannister, J., Sievers, M., Bush, F., and Bloecher, N., 2019. Biofouling in marine aquaculture: A review of recent research and developments. Biofouling, 35(6): 631-648. DOI:10.1080/08927014.2019.1640214 (  0) 0) |

Callow, J. A., and Callow, M. E., 2011. Trends in the development of environmentally friendly fouling-resistant marine coatings. Nature Communications, 2(1): 1-10. (  0) 0) |

Chambers, L. D., Stokes, K. R., Walsh, F. C., and Wood, R. J. K., 2006. Modern approaches to marine antifouling coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology, 201(6): 3642-3652. DOI:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2006.08.129 (  0) 0) |

Chen, R., Li, Y., Tang, L., Yang, H., Lu, Z., Wang, J., et al., 2017. Synthesis of zinc-based acrylate copolymers and their marine antifouling application. RSC Advances, 7(63): 40020-40027. DOI:10.1039/C7RA04840H (  0) 0) |

Chen, S., Zheng, J., Li, L., and Jiang, S., 2005. Strong resistance of phosphorylcholine self-assembled monolayers to protein adsorption: Insights into nonfouling properties of zwitterionic materials. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 127(41): 14473-14478. DOI:10.1021/ja054169u (  0) 0) |

Chen, Z., Zhao, W., Mo, M., Zhou, C., Liu, G., Zeng, Z., et al., 2015. Architecture of modified silica resin coatings with various micro/nano patterns for fouling resistance: Microstructure and antifouling performance. RSC Advances, 5(118): 97862-97873. DOI:10.1039/C5RA17179B (  0) 0) |

Ciriminna, R., Bright, F. V., and Pagliaro, M., 2015. Ecofriendly antifouling marine coatings. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering, 3(4): 559-565. DOI:10.1021/sc500845n (  0) 0) |

Dai, G., Xie, Q., Ai, X., Ma, C., and Zhang, G., 2019. Self-generating and self-renewing zwitterionic polymer surfaces for marine anti-biofouling. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 11(44): 41750-41757. DOI:10.1021/acsami.9b16775 (  0) 0) |

Di Pasqua, R., Betts, G., Hoskins, N., Edwards, M., Ercolini, D., and Mauriello, G., 2007. Membrane toxicity of antimicrobial compounds from essential oils. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 55(12): 4863-4870. DOI:10.1021/jf0636465 (  0) 0) |

Fernandes, S. C. M., Sadocco, P., Alonso-Varona, A., Palomares, T., Eceiza, A., Silvestre, A. J. D., et al., 2013. Bioinspired antimicrobial and biocompatible bacterial cellulose membranes obtained by surface functionalization with aminoalkyl groups. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 5(8): 3290-3297. DOI:10.1021/am400338n (  0) 0) |

Ferriol, M., Gentilhomme, A., Cochez, M., Oget, N., and Mieloszynski, J. L., 2003. Thermal degradation of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA): Modelling of DTG and TG curves. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 79(2): 271-281. DOI:10.1016/S0141-3910(02)00291-4 (  0) 0) |

Finlay, J. A., Callow, M. E., Schultz, M. P., Swain, G. W., and Callow, J. A., 2002. Adhesion strength of settled spores of the green alga Enteromorpha. Biofouling, 18(4): 251-256. DOI:10.1080/08927010290029010 (  0) 0) |

Formigari, A., Irato, P., and Santon, A., 2007. Zinc, antioxidant systems and metallothionein in metal mediated-apoptosis: Biochemical and cytochemical aspects. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Toxicology & Pharmacology, 146(4): 443-459. (  0) 0) |

Hepler, P. K., 2005. Calcium: A central regulator of plant growth and development. The Plant Cell, 17(8): 2142-2155. DOI:10.1105/tpc.105.032508 (  0) 0) |

Huang, C., Brault, N. D., Li, Y., Yu, Q., and Jiang, S., 2012. Controlled hierarchical architecture in surface-initiated zwitterionic polymer brushes with structurally regulated functionalities. Advanced Materials, 24(14): 1834-1837. DOI:10.1002/adma.201104849 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, S., and Cao, Z., 2010. Ultralow-fouling, functionalizable, and hydrolyzable zwitterionic materials and their derivatives for biological applications. Advanced Materials, 22(9): 920-932. DOI:10.1002/adma.200901407 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, W., Jin, X., Li, H., Zhang, S., Zhou, T., and Xie, H., 2020. Modification of nano-hybrid silicon acrylic resin with anticorrosion and hydrophobic properties. Polymer Testing, 82: 106287. DOI:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2019.106287 (  0) 0) |

Kenawy, E., Worley, S. D., and Broughton, R., 2007. The chemistry and applications of antimicrobial polymers: A state-of-the-art review. Biomacromolecules, 8(5): 1359-1384. DOI:10.1021/bm061150q (  0) 0) |

Kiil, S., Weinell, C. E., Pedersen, M. S., and Dam-Johansen, K., 2001. Analysis of self-polishing antifouling paints using rotary experiments and mathematical modeling. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research, 40(18): 3906-3920. DOI:10.1021/ie010242n (  0) 0) |

Kumar, A., Mills, S., Bazaka, K., Bajema, N., Atkinson, I., and Jacob, M. V., 2018. Biodegradable optically transparent terpinen-4-ol thin films for marine antifouling applications. Surface and Coatings Technology, 349: 426-433. DOI:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.05.074 (  0) 0) |

Lacoste, E., and Gaertner-Mazouni, N., 2015. Biofouling impact on production and ecosystem functioning: A review for bivalve aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture, 7(3): 187-196. DOI:10.1111/raq.12063 (  0) 0) |

Lejars, M., Margaillan, A., and Bressy, C., 2012. Fouling release coatings: A nontoxic alternative to biocidal antifouling coatings. Chemical Reviews, 112(8): 4347-4390. DOI:10.1021/cr200350v (  0) 0) |

Liu, X., Gan, K., Liu, H., Song, X., Chen, T., and Liu, C., 2017. Antibacterial properties of nano-silver coated PEEK prepared through magnetron sputtering. Dental Materials, 33(9): e348-e360. DOI:10.1016/j.dental.2017.06.014 (  0) 0) |

Ma, C., Xu, L., Xu, W., and Zhang, G., 2013. Degradable polyurethane for marine anti-biofouling. Journal of Materials Chemistry. B, Materials for Biology and Medicine, 1(24): 3099-3106. DOI:10.1039/c3tb20454e (  0) 0) |

Ma, C., Yang, H., Zhou, X., Wu, B., and Zhang, G., 2012. Polymeric material for anti-biofouling. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 100: 31-35. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.04.045 (  0) 0) |

Schultz, M. P., 2007. Effects of coating roughness and biofouling on ship resistance and powering. Biofouling, 23(5): 331-341. DOI:10.1080/08927010701461974 (  0) 0) |

Schultz, M. P., Bendick, J. A., Holm, E. R., and Hertel, W. M., 2011. Economic impact of biofouling on a naval surface ship. Biofouling, 27(1): 87-98. DOI:10.1080/08927014.2010.542809 (  0) 0) |

Sousa, A. C. A., Pastorinho, M. R., Takahashi, S., and Tanabe, S., 2014. History on organotin compounds, from snails to humans. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 12(1): 117-137. DOI:10.1007/s10311-013-0449-8 (  0) 0) |

Tsibouklis, J., and Nevell, T. G., 2003. Ultra-low surface energy polymers: The molecular design requirements. Advanced Materials, 15(78): 647-650. DOI:10.1002/adma.200301638 (  0) 0) |

Wendy, V. Z., Buss, H. G., Ellebracht, N. C., Lynd, N. A., Fischer, D. A., Finlay, J. A., et al., 2014. Sequence of hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues in amphiphilic polymer coatings affects surface structure and marine antifouling/fouling release properties. ACS Macro Letters, 3(4): 364-368. DOI:10.1021/mz500090n (  0) 0) |

Wu, G., Li, C., Jiang, X., and Yu, L., 2016. Highly efficient antifouling property based on self-generating hydrogel layer of polyacrylamide coatings. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 133(42): 1-11. (  0) 0) |

Wu, Y., Wu, W., Zhao, W., and Lan, X., 2020. Revealing the antibacterial mechanism of copper surfaces with controllable microstructures. Surface and Coatings Technology, 395: 125911. DOI:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.125911 (  0) 0) |

Xie, C., Guo, H., Zhao, W., and Zhang, L., 2020. Environmentally friendly marine antifouling coating based on a synergistic strategy. Langmuir, 36(9): 2396-2402. DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b03764 (  0) 0) |

Xie, L., Hong, F., He, C., Ma, C., Liu, J., Zhang, G., et al., 2011. Coatings with a self-generating hydrogel surface for antifouling. Polymer, 52(17): 3738-3744. DOI:10.1016/j.polymer.2011.06.033 (  0) 0) |

Xie, Q., Xie, Q., Pan, J., Ma, C., and Zhang, G., 2018. Biodegradable polymer with hydrolysis-induced zwitterions for antibiofouling. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 10(13): 11213-11220. DOI:10.1021/acsami.8b00962 (  0) 0) |

Xu, J., Zhao, W., Peng, S., Zeng, Z., Zhang, X., Wu, X., et al., 2014. Investigation of the biofouling properties of several algae on different textured chemical modified silicone surfaces. Applied Surface Science, 311: 703-708. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.05.140 (  0) 0) |

Xu, W., Ma, C., Ma, J., Gan, T., and Zhang, G., 2014. Marine biofouling resistance of polyurethane with biodegradation and hydrolyzation. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 6(6): 4017-4024. DOI:10.1021/am4054578 (  0) 0) |

Yebra, D. M., Kiil, S., and Dam-Johansen, K., 2004. Antifouling technology – Past, present and future steps towards efficient and environmentally friendly antifouling coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings, 50(2): 75-104. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2003.06.001 (  0) 0) |

Yebra, D. M., Kiil, S., Dam-Johansen, K., and Weinell, C., 2005. Reaction rate estimation of controlled-release antifouling paint binders: Rosin-based systems. Progress in Organic Coatings, 53(4): 256-275. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2005.03.008 (  0) 0) |

Yonehara, Y., Yamashita, H., Kawamura, C., and Itoh, K., 2001. A new antifouling paint based on a zinc acrylate copolymer. Progress in Organic Coatings, 42(3): 150-158. (  0) 0) |

Zhou, W., Wang, Y., Ni, C., and Yu, L., 2021. Preparation and evaluation of natural rosin-based zinc resins for marine antifouling. Progress in Organic Coatings, 157: 106270. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106270 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22