The exhaust gases produced by ocean-going vessels in shipping contain a large amount of NOx and SOx and other harmful components, which have a negative impact on the marine ecological environment (Wang et al., 2009; Hassellöv et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2021). Therefore, the development of new technologies and equipment for desulfurization and denitration is of great importance. The fluidic oscillator is a flow control device that produces unsteady jets without additional moving parts, which has great application potential for the mass transfer enhancement of gas-liquid in the field of desulfurization and denitration. At present, it has been widely used in chemical engineering, aerospace, separation control, heat and mass transfer enhancement, and so on (Woszidlo and Wygnanski, 2011; He et al., 2015; Raman et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2019).

According to the driving mechanism of the fluidic oscillator, it can be categorized into wall-attachment and jet-interaction fluidic oscillators (Hao et al., 2020). In this paper, the wall-attachment fluidic oscillator is studied, which is mainly composed of a power nozzle, chamber region, two feedback loops, and two exit channels.

Numerous investigations of the fluidic oscillator have been done since it was first proposed in the 1960s (Warren, 1962). Zimmerman et al. (2011) conducted the oscillating airflow into the water to produce microbubbles, and the oscillating airflow is generated by a fluid oscillator. Tesar (2014) connected the fluid oscillator to the aerator and found that the pulsating jet produced by the fluid oscillator could effectively generate microbubbles. The generation of microbubbles plays an important role in mass transfer between gas and liquid (Yin et al., 2015). However, the study of gas-liquid flow in fluid oscillators has not been carried out. McDonough et al. (2017) studied the influence of the geometry of the fluid oscillator on oscillation frequency. The results show that the decrease of the splitter distance and the increase of the angle of the two outlet channels are beneficial to improve the oscillation frequency. Pandey and Kim (2018) explored the influence of geometric parameters on internal flow characteristics of fluid oscillators. Hao et al. (2020) used the large eddy simulation and visual experiment to study the jet deflection mechanism in the fluid oscillator. It is pointed out that the pressure difference between the left and right sides of the chamber is an important factor driving the main jet deflection. Bobusch et al. (2013) investigated the flow field characteristics of the fluid oscillator by experiments. They found that the inlet and outlet characteristic parameters of the chamber have an important influence on the flow field characteristics.

In the previous literature, the fluid oscillator study is mainly focused on the flow characteristics of single-phase fluids. However, the investigations of the bubble breakup and bubble motion in the fluid oscillator have not attracted enough attention from scholars. Interestingly, the power nozzles and chambers of the fluid oscillator have similar geometry to the Venturi bubble generator, and the special deflecting oscillation characteristics of the fluid oscillator are more conducive to bubble breakup. Therefore, fluid oscillators have great potential for applications in producing microbubbles.

In this work, bubble movement in fluidic oscillator was studied, which lay a foundation for the subsequent investigation of bubble breakup. Although the motion behavior of bubbles in fluid oscillators has not attracted much attention, the research methods and experimental results of bubble motion in the Venturi bubble generator are valuable. Ding et al. (2021) investigated the bubble transport process in a new two-stage series venturi bubble generator, which provides a new idea for the design of a bubble generator. Zhao et al. (2018) and Wang et al. (2021) use high-speed camera technology to analyze the movement of bubbles in the Venturi bubble generator. They found that there was a deceleration process in diverging section of the Venturi bubble generator, which was the key factor of bubble breakup. Moreover, Ravelet et al. (2011) studied the dynamic characteristics and breakup of bubbles in the turbulent field through a high-speed camera experiment. Risso and Fabre (1998) explored the deformation and breakup of bubbles in the turbulent flow. Their results show that it is of great significance to study bubble dynamics in the flow field. Liu et al. (2021) investigated the influence of deflecting oscillation of the main jet on bubble motion and bubble breakup in the fluidic oscillator. Compared with other fluidic bubble generators, there are periodic deflecting jets in the oscillating chamber of the fluidic oscillator, which can effectively strengthen the bubble breakup. In addition, when the jet deflects to one side of the oscillating chamber, a low-pressure area is generated on the other side, which can increase the residence time of bubbles and is conducive to bubble breakup.

From the analysis of the above scholars, it can be noted that the bubble breakup is closely related to the characteristics of bubble motion. The main objective of this paper, by studying the velocity, trajectory, and deformation ratio of bubbles, is to reveal the action mechanism of deflecting oscillation in the oscillating chamber of the fluidic oscillator on bubble motion. The results of studies can provide a reliable basis for the theoretical and numerical simulation of bubble breakup as well as gas-liquid mass transfer enhanced by the fluidic oscillator in the future.

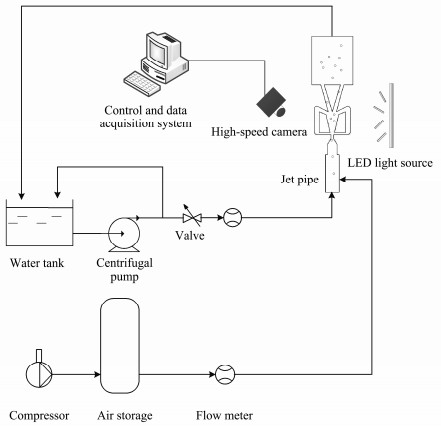

2 Experimental Procedure 2.1 Experimental SetupThe visualization technology was used to study the movement process of bubbles in the fluidic oscillator at experiments. The whole experiment was conducted at 20℃ with air and water as working fluids. The schematic of the experimental system is shown in Fig. 1. The experimental system could be divided into three parts: water supply system, gas supply system, and high-speed camera system. The water supply system mainly consists of CDM vertical multistage centrifugal pump, rectangular tank, electromagnetic flowmeter, valve, and corresponding pipelines. The gas supply system is composed of a gas compressor, air storage tank, gas flowmeter. The highspeed camera system is mainly composed of a high-speed camera (model number: FASTCAM Mini WX), computer, corresponding control software, and LED backlight board. Water flow rate varied from 0 L min−1 to 30 L min−1 and airflow rate covered the range of 0.01 L min−1 – 0.05 L min−1. The liquid Reynolds number (Re) was used for correlation analysis. The Reynolds number is defined as Re

|

Fig. 1 Schematic of the experimental system. |

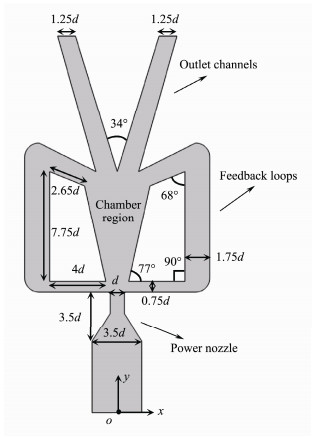

The experimental model of the fluid oscillator was made of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), which had good light transmittance to ensure clear images. Fig. 2 presents the geometrical dimensions of the fluidic oscillator. The throat width d is 4 mm. The other dimensions of the fluidic oscillator would be made non-dimensional by using the throat width d. The depth of the entire oscillator is 2d.

|

Fig. 2 Dimensions of the fluidic oscillator. |

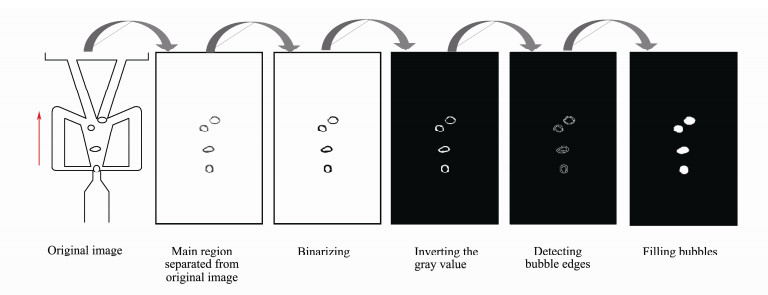

The size, shape, and motion parameters of bubbles were obtained from images by MATLAB. The process is shown in Fig. 3. At first, the bubbles in main region were separated from the original image to save the processing time. Next, the image was binarized and the gray value of the image was inverted (Zhao et al., 2018). In order to capture the bubble boundary, Canny algorithm (Canny, 1986) was used to detect the edge of the bubble. Finally, the closed edges were filled to obtain a complete bubble.

|

Fig. 3 Schematics of image processing. |

Assuming that the diameter of the bubble in the twodimensional image is the same as that of the circular bubble with the same area, the equivalent diameter of the bubble can be approximately considered to be the diameter of the two-dimensional bubble. It can be calculated (Zhou et al., 2012):

| $ {D_e} = \sqrt {\frac{{4A}}{{\text{π }}}}, $ | (1) |

where A is the projected area of the bubble.

All pixel points in the bubble image are added up and their average value is calculated. The average value is taken as the centroid coordinate of the bubble. It is given by:

| $ {x_c} = \sum\nolimits_{i, j \in {{\Omega }}} {i/N}, $ | (2) |

| $ {y_c} = \sum\nolimits_{i, j \in {{\Omega }}} {j/N}, $ | (3) |

where xc and yc represent the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the centroid respectively. N is the total number of pixels in the bubble region.

The velocity of the bubbles in horizontal and vertical directions can be calculated by the distance of the centroid of the bubbles in two adjacent frames:

| $ {U_{x, {\text{ }}n}} = \frac{{{x_{n + 1}} - {x_n}}}{{\Delta t}}, $ | (4) |

| $ {U_{y, {\text{ }}n}} = \frac{{{y_{n + 1}} - {y_n}}}{{\Delta t}}, $ | (5) |

where n is the nth image (n = 1, 2, 3, …), (xn, xn+1) and (yn, yn+1) are the coordinates of the centroid of the bubble in the two adjacent frames.

The velocity and acceleration of the bubble are calculated by Eqs. (4) and (5):

| $ U = \sqrt {U_x^2 + U_y^2}, $ | (6) |

| $ a = {{\Delta U} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\Delta U} {\Delta t}}} \right. } {\Delta t}}, $ | (7) |

where ΔU is the bubble velocity variation in two adjacent frames, Δt is the time interval.

During the movement of the bubble in the fluid oscillator, the bubble is deformed by various forces. To quantitatively describe the change of bubble shape, the deformation ratio E is used to calculate (Di Marco et al., 2003):

| $ E = \frac{a}{b}, $ | (8) |

where a and b are long-axis and short-axis of bubbles respectively. E = 1 means the spherical bubble.

3 Results and DiscussionIn order to study the dynamic characteristics of bubbles in the fluid oscillator, at first, the characteristics of bubble transportation are investigated (Section 3.1), and then the velocity and acceleration of bubbles are explored (Section 3.2). Since the diameter of initial bubbles affects the dynamic characteristics, the influence of the diameter of initial bubbles on the bubble velocity and trajectory is studied (Section 3.3). Finally, the effect of special deflection oscillation in the fluidic oscillator on the bubble deformation ratio is investigated (Section 3.4).

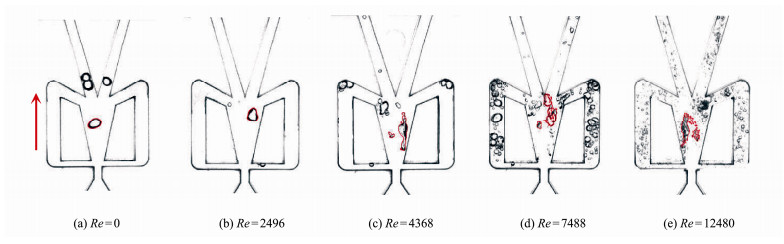

3.1 Transport Characteristics of Bubbles in the Fluidic OscillatorFig. 4 presents the bubbles along the flow direction in the chamber region of the fluidic oscillator with different liquid Reynolds numbers. It can be seen that the movement of bubbles in a fluid oscillator is complicated and variable. With the increasing of liquid Reynolds numbers, the bubble deforms first, then shear-off-induced bubble breakup and multiple breakup occur. For Re = 4368, as shown in Fig. 4(c), the bubble breakup owing to shear-off process in the flow field. For higher Reynolds numbers (shown in Figs. 4(d) and (e)), the multiple breakup appears in the oscillating chamber. It is noted that the flow field characteristics of the fluidic oscillator play an important role in the shape of bubbles. This paper mainly focuses on the dynamic characteristics and movements of bubbles in the fluidic oscillator. So only the motion states before bubble breakup at low Reynolds numbers are considered.

|

Fig. 4 Bubble transportation process in the fluidic oscillator. |

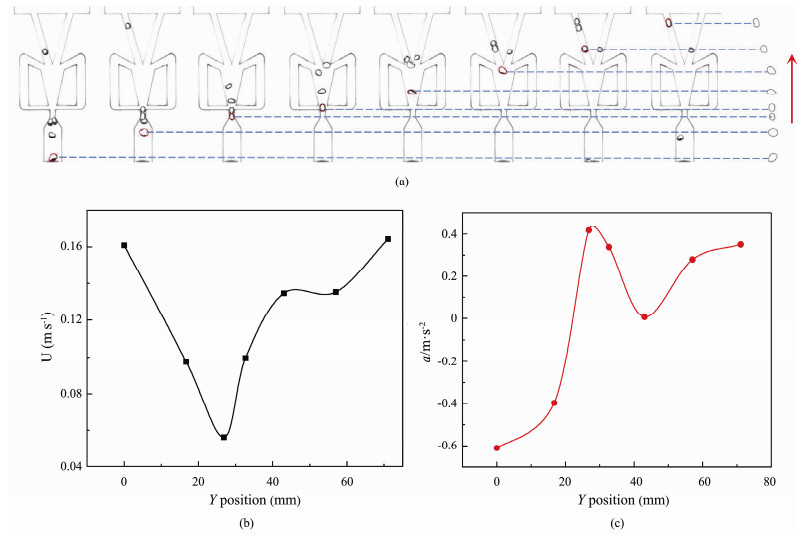

To investigate the dynamics of bubbles under different Reynolds numbers in the fluidic oscillator, the velocity and acceleration of bubbles and the trajectory of bubbles are studied. Fig. 5(a) shows the movement path of bubbles in the fluidic oscillator at Re = 0 (stagnant water). As the bubbles are mainly affected by gravity and buoyancy in stagnant water, the bubbles keep straight motion from the inlet to the oscillating chamber and then deflect under the induction of the outlet branch as shown in Fig. 5(a).

|

Fig. 5 Characteristics of bubble motion at Re = 0. (a), process of bubble motion; (b), variations of velocity; (c), variations of acceleration. |

The variation of bubble velocity and acceleration at Re = 0 are reported in Figs. 5(b) and (c). There are two stages in the variation of bubble velocity in stagnant water: deceleration and acceleration. When the bubbles move to the oscillator nozzle, some of the bubbles gather at the nozzle due to the influence of the nozzle structure, which makes the bubble speed decrease rapidly. Once the bubble passes through the nozzle, the bubble velocity increases dramatically. Bubbles randomly enter an outlet branch and leave the oscillator. According to the change of acceleration in Fig. 5(c), the bubble acceleration increases first, then decreases, and increases finally, which indicates that the bubble is in a motion state of acceleration fluctuation.

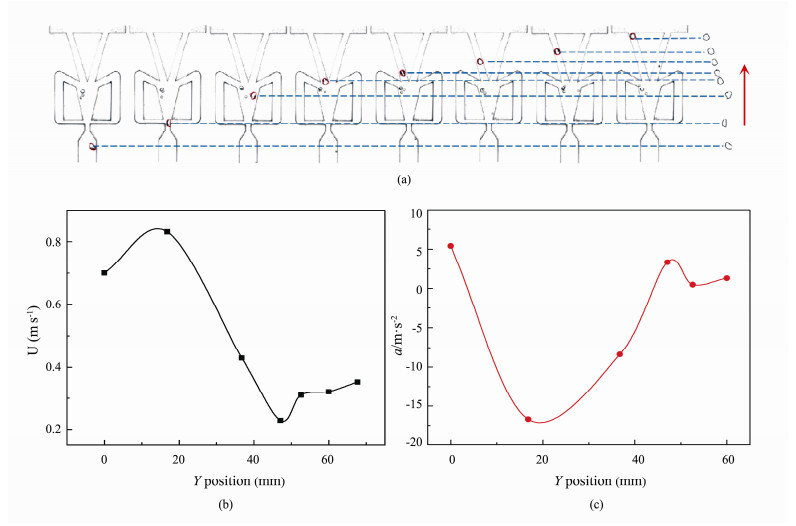

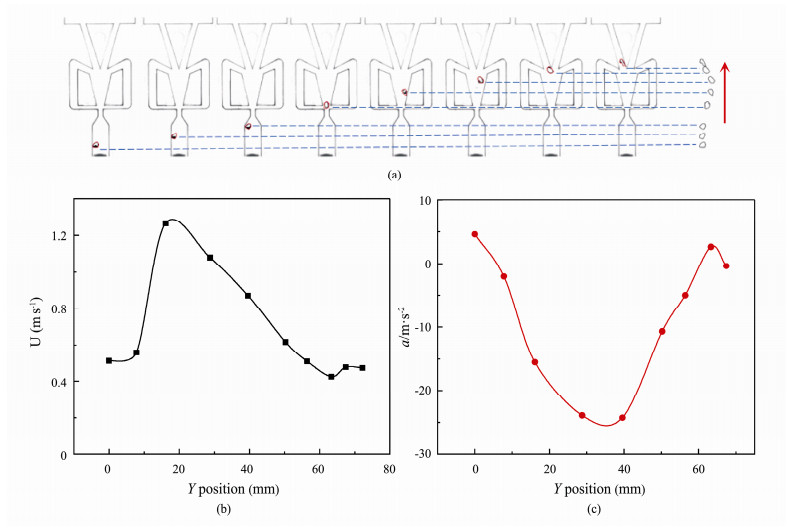

The trajectory of the bubble in fluidic oscillator at Re = 2496 and Re = 3744 are represented in Figs. 6(a) and 7(a). Compared with the bubbles in stagnant water in Fig. 5(a), the movement trajectory of bubbles exhibits obvious deflection. This is because the fluid deflects and oscillates in the oscillating chamber with increasing the Reynolds number, which drives the bubbles to move. As a result, the bubble trajectory is deflected.

|

Fig. 6 Characteristics of bubble motion at Re = 2496. (a), process of bubble motion; (b), variations of velocity; (c), variations of acceleration. |

|

Fig. 7 Characteristics of bubble motion at Re = 3744. (a), process of bubble motion; (b), variations of velocity; (c), variations of acceleration. |

The velocities and accelerations of bubbles in Re = 2496 and Re = 3744 have similar variations, as shown in Figs. 6(b), (c) and Figs. 7(b), (c) respectively. However, it is significantly different from the bubble in stagnant water. When the Reynolds number increases, the change of bubble velocity through complex processes. At first, the bubble velocity increases. Because the oscillator inlet is a converging structure, the converging structure increases the velocity of the liquid, thereby increasing the velocity of the bubble movement. The bubbles pass through the throat into an oscillating chamber with a diverging structure. The liquid velocity in the oscillating chamber decreases, which results in the bubble velocity decreasing. The oscillating chamber of the fluidic oscillator is similar to the diverging section of a venturi bubble generator. Zhao et al. (2019) found that the velocity of the bubble in the diverging section of the venturi bubble generator decreased, which is consistent with the velocity variation of the bubble in the chamber region of the fluidic oscillator. According to the variation acceleration in Fig. 6(c) and Fig. 7(c), it can be seen that the bubble in the oscillating chamber is a deceleration process in which the acceleration gradually increases. Bie et al. (2021) found that a low-pressure region appeared in the oscillating chamber. The low-pressure region was located near the outlet branch of the oscillating chamber. The change of bubble acceleration in the decelerating process may be caused by the influence of the low-pressure region. Finally, the bubble enters the outlet branch of the fluidic oscillator, and the movement speed increases slowly.

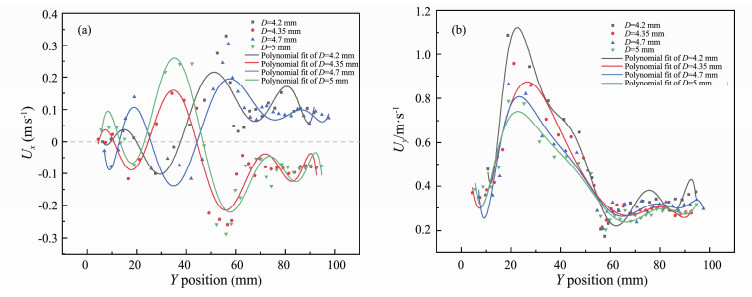

3.3 The Influence of Initial Bubble Diameter on Bubble Movement Speed and TrajectoryAs discussed in Section 3.2, the bubble experienced different processes of velocity and acceleration in the fluid oscillator. However, studies by Li et al. (2016) show that the diameter of initial bubble has an important influence on the dynamic characteristics of bubbles. Therefore, to further explore the dynamics of bubbles in the fluid oscillator, the effects of different initial bubble diameters on velocity and trajectory were investigated.

According to the coordinates of the bubble centroid at different time intervals, the velocity Ux of the bubble in the horizontal direction and the velocity Uy in the vertical direction can be obtained. The variation of horizontal and vertical velocities of bubbles with different initial bubble diameters in the process of movement in the fluidic oscillator at Re = 2496 are represented in Fig. 8. As can be seen from Fig. 8(a), the horizontal velocity fluctuates between positive and negative after the bubble enters the oscillating chamber, which is caused by the continuous oscillation of the fluid in the chamber region of the fluidic oscillator. When the bubble enters the outlet branch, the fluid no longer deflects and oscillates, so the horizontal velocity of the bubble tends to be stable. In addition, the horizontal velocity tends to increase with the increase of the initial bubble diameter, which indicates that bubbles with a large initial diameter are easily deflected by the flow field. However, the vertical velocity of the bubble tends to decrease with the increase of the initial bubble diameter (see Fig. 8(b)), which may be due to the fact that the bubble with a larger diameter is subjected to larger resistance in the vertical direction.

|

Fig. 8 The influence of the diameters of initial bubble on bubble velocity. |

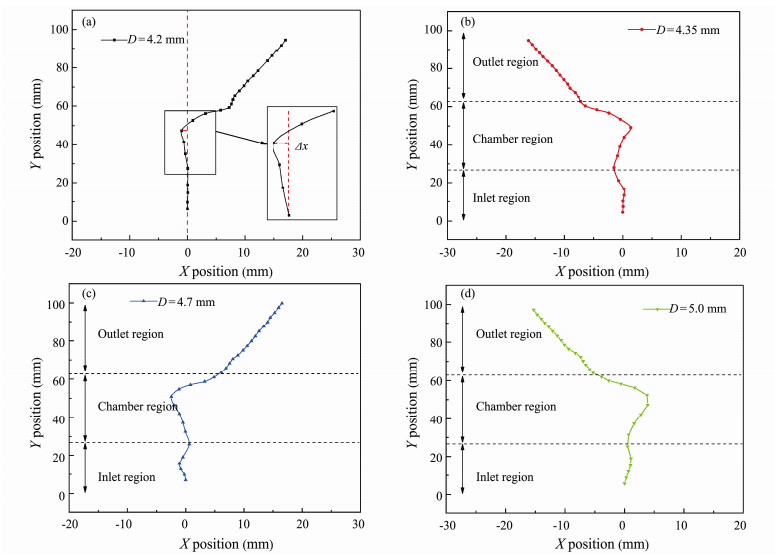

Bubbles are subjected to various forces in the fluidic oscillator. The force acting on the bubble has an important influence on the movement trajectory of the bubble. Besides, the force acting on the bubble is closely related to the bubble size. Therefore, the influence of the initial bubble diameter on the bubble motion trajectory was investigated. By extracting the coordinates of the centroid of the bubble in the experimental image to determine the position of the bubble, the motion trajectory of the bubble in the fluidic oscillator can be obtained. Fig. 9 shows the movement of bubbles with different diameters of the initial bubble in the fluidic oscillator when Re = 2496. After entering the chamber region through the throat, the bubble with an initial diameter of 4.2 mm is gradually deflected towards the left side of the chamber region. Because of the oscillation of the fluid in the chamber region, the bubbles are deflected to the right side at a relatively short distance and then leave the fluidic oscillator along the outlet branch. Obviously, the trajectory of the bubble exhibits zigzag motion. It should be noted that the deflection of the bubble in the chamber region and the outlet branches of the inflow is also random. Previous studies have found that there are mainly three types of bubble motion trajectories, which are linear, zigzag, and helical (Ellingsen and Risso, 2001; Tomiyama et al., 2002; Brenn et al., 2006). Tomiyama et al. (2002) observed the zigzag trajectory in the experiment, which has a good similarity with this paper.

|

Fig. 9 The influence of difference of initial bubble diameter on bubble trajectory. |

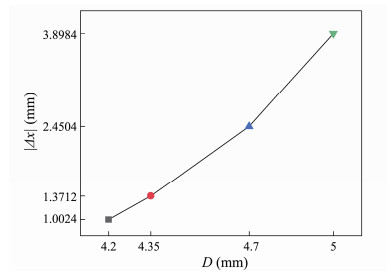

Bubbles with initial diameters of 4.35 mm, 4.7 mm and 5 mm have similar trajectories to the bubbles with initial diameters of 4.2 mm as shown in Figs. 9(b) – (d). However, the degree of the horizontal deflection is different. In order to quantitatively describe the bubble deflection degree, the maximum offsets from the vertical centerline during the bubble movement is defined as deflection degree Δx, as shown in Fig. 9(a). The maximum offsets for bubbles with different initial diameters are calculated and plotted in Fig. 10. Obviously, the maximum offset increases with the diameter of the initial bubble. This is due to the fact that the bubbles with larger initial diameters are more likely to be affected by the flow field oscillation to offset the centerline.

|

Fig. 10 The relationship between the horizontal offset of the bubble and the initial bubble diameter. |

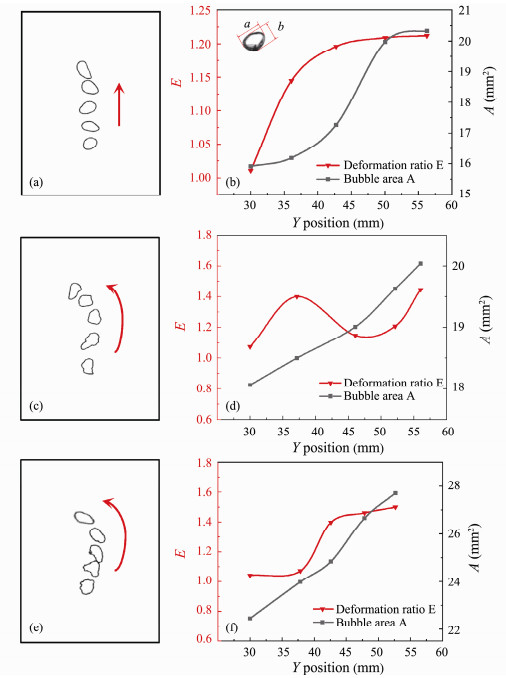

Based on the above analysis, there is a deceleration process of bubbles in the chamber region of the fluid oscillator, and the deceleration process of bubbles has a great influence on the shape of bubbles. Thus, the deformation ratio of the bubble is analyzed to investigate the influence of the deceleration process on the shape of the bubble. In order to observe the deformation of the bubble in the chamber region clearly, the contour of the same bubble at different time intervals is extracted from the experimental image and put in the same picture, as shown in Figs. 11(a), (c), and (e).

|

Fig. 11 Variations of bubble area and deformation ratio. (a) and (b), Re = 0; (c) and (d), Re = 2496; (e) and (f), Re = 3744. |

Figs. 11(b), (d), and (f) show the change of bubble deformation ratio and projected area during the bubble movement in the chamber region of the fluidic oscillator at different Reynolds numbers. It can be seen from Fig. 11(a) that when Re = 0 (stagnant water), the shape of the bubble transforms from sphere to ellipsoid. At the same time, the bubble deformation ratio increases from about 1.0 to about 1.2, and remains stable at about 1.2. Moreover, as the bubble deformation ratio increases, the bubble projected area gradually increases. With the increasing Reynolds number, a deflecting oscillation of the fluid occurs in the chamber region of the fluidic oscillator, which dramatically promotes the deformation of the bubbles. The surface of the bubble is no longer smooth, but appears depressed and bulge, as shown in Figs. 11(c) and (e). For Re = 2496, the deformation ratio of the bubble increases from 1.0 to 1.4. Although the deformation ratio of bubbles fluctuates, the projected area of bubbles increases with the movement of bubbles. For Re = 3744, both the bubble deformation ratio and the projected area increase with the movement of the bubble. At last, the bubble deformation ratio remains stable at about 1.5. Compared with the bubble in stagnant water, the increase of Reynolds number results in irregular folds on the bubble surface, while the bubble surface in stagnant water is smooth. The deflecting oscillation of the fluid strongly promotes the deformation of the bubble.

4 ConclusionsTo investigate the motion of individual bubbles in the fluidic oscillator, an experiment with a high-speed camera system was carried out. Digital image analysis technology was used to process the images captured in the experiment. The results could be concluded as follows:

1) The velocity of the bubble increases as it enters the oscillator. Once the bubble passes through the throat into the chamber region, the bubble experienced a significant deceleration process. Finally, the velocity increases again after the bubble enters the outlet branch.

2) With the increasing diameter of the initial bubble, the horizontal velocity of the bubble increases, while the vertical velocity decreases. The movement trajectory of bubbles is zigzag in the fluidic oscillator, and the maximum offset increases with the increase of the initial diameter of the bubble.

3) The deflecting oscillation in the chamber region of the fluidic oscillator intensifies the deformation of the bubble. As the bubble moves, the projected area of the bubble increases gradually.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22178329), the Taishan Scholars Program, the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Nos. ZR2020ME175, ZR2020QE192), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 202165002).

Bie, H., Huang, C., An, W., Li, Y., and Lin, Z., 2021. Numerical simulation of internal flow characteristics of feedback fluidic oscillator. CIESC Journal, 72(3): 1504-1511. DOI:10.11949/0438-1157.20201883 (  0) 0) |

Bobusch, B. C., Woszidlo, R., Bergada, J. M., Nayeri, C. N., and Paschereit, C. O., 2013. Experimental study of the internal flow structures inside a fluidic oscillator. Experiments in Fluids, 54(6): 1-12. DOI:10.1007/s00348-013-1559-6 (  0) 0) |

Brenn, G., Kolobaric, V., and Durst, F., 2006. Shape oscillations and path transition of bubbles rising in a model bubble column. Chemical Engineering Science, 61(12): 3795-3805. DOI:10.1016/j.ces.2005.12.016 (  0) 0) |

Canny, J., 1986. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 8(6): 679-698. DOI:10.1109/TPAMI.1986.4767851 (  0) 0) |

Di Marco, P., Grassi, W., and Memoli, G., 2003. Experimental study on rising velocity of nitrogen bubbles in FC-72. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 42(5): 435-446. DOI:10.1016/s1290-0729(02)00044-3 (  0) 0) |

Ding, G., Li, Z., Chen, J., and Cai, X., 2021. An investigation on the bubble transportation of a two-stage series venturi bubble generator. Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 174: 345-356. DOI:10.1016/j.cherd.2021.08.022 (  0) 0) |

Ellingsen, K., and Risso, F., 2001. On the rise of an ellipsoidal bubble in water: Oscillatory paths and liquid-induced velocity. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 440: 235-268. DOI:10.1017/s0022112001004761 (  0) 0) |

Hao, Z. R., Liu, G., Wang, Y., and Ren, W. L., 2020. Studies on the drive mechanism of the main jet deflection inside a fluidic oscillator. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 59(20): 9629-9641. DOI:10.1021/acs.iecr.9b06678 (  0) 0) |

Hassellöv, I. M., Turner, D. R., Lauer, A., and Corbett, J. J., 2013. Shipping contributes to ocean acidification. Geophysical Research Letters, 40(11): 2731-2736. DOI:10.1002/grl.50521 (  0) 0) |

He, J., Yin, K., Peng, J., Zhang, X., Liu, H., and Gan, X., 2015. Design and feasibility analysis of a fluidic jet oscillator with application to horizontal directional well drilling. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 27: 1723-1731. DOI:10.1016/j.jngse.2015.10.040 (  0) 0) |

Li, X., Ma, X., Zhang, L., and Zhang, H., 2016. Dynamic characteristics of ventilated bubble moving in micro scale venturi. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, 100: 79-86. DOI:10.1016/j.cep.2015.11.009 (  0) 0) |

Liu, G., Bie, H., Hao, Z., Wang, Y., Ren, W., and Hua, Z., 2021. Microbubble generation driven by the oscillation in a selfexcited fluidic oscillator. AIChE Journal, 68(1): 1-14. DOI:10.1002/aic.17428 (  0) 0) |

McDonough, J. R., Law, R., Kraemer, J., and Harvey, A. P., 2017. Effect of geometrical parameters on flow-switching frequencies in 3D printed fluidic oscillators containing different liquids. Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 117: 228-239. DOI:10.1016/j.cherd.2016.10.034 (  0) 0) |

Pandey, R. J., and Kim, K. Y., 2018. Numerical modeling of internal flow in a fluidic oscillator. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology, 32(3): 1041-1048. DOI:10.1007/s12206-018-0205-x (  0) 0) |

Raman, G., Packiarajan, S., Papadopoulos, G., Weissman, C., and Raghu, S., 2016. Jet thrust vectoring using a miniature fluidic oscillator. The Aeronautical Journal, 109(1093): 129-138. DOI:10.1017/s0001924000000634 (  0) 0) |

Ravelet, F., Colin, C., and Risso, F., 2011. On the dynamics and breakup of a bubble rising in a turbulent flow. Physics of Fluids, 23(10): 1-12. DOI:10.1063/1.3648035 (  0) 0) |

Risso, F., and Fabre, J., 1998. Oscillations and breakup of a bubble immersed in a turbulent field. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 372: 323-355. DOI:10.1017/s0022112098002705 (  0) 0) |

Tesar, V., 2014. Microbubble generator excited by fluidic oscillator's third harmonic frequency. Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 92(9): 1603-1615. DOI:10.1016/j.cherd.2013.12.004 (  0) 0) |

Tomiyama, A., Celata, G. P., Hosokawa, S., and Yoshida, S., 2002. Terminal velocity of single bubbles in surface tension force dominant regime. International Journal of Multiphase Flow, 28(9): 1497-1519. DOI:10.1016/s0301-9322(02)00032-0 (  0) 0) |

Wang, H., Liu, D., and Dai, G., 2009. Review of maritime transportation air emission pollution and policy analysis. Journal of Ocean University of China, 8(3): 283-290. DOI:10.1007/s11802-009-0283-6 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X. Y., Shuai, Y., Zhang, H. M., Sun, J. Y., Yang, Y., Huang, Z. L., et al., 2021. Bubble breakup in a swirl-venturi microbubble generator. Chemical Engineering Journal, 403: 11. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126397 (  0) 0) |

Woszidlo, R., and Wygnanski, I., 2011. Parameters governing separation control with sweeping jet actuators. 29th AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference. 3172, DOI: 10.2514/6.2011-3172.

(  0) 0) |

Wu, Y., Yu, S., and Zuo, L., 2019. Large eddy simulation analysis of the heat transfer enhancement using self-oscillating fluidic oscillators. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 131: 463-471. DOI:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.11.070 (  0) 0) |

Yin, J., Li, J., Li, H., Liu, W., and Wang, D., 2015. Experimental study on the bubble generation characteristics for an venturi type bubble generator. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 91: 218-224. DOI:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstrans-fer.2015.05.076 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, J., Wei, Q., Wang, S., and Ren, X., 2021. Progress of ship exhaust gas control technology. Science of the Total Environment, 799: 149437. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149437 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, L., Sun, L., Mo, Z., Du, M., Huang, J., Bao, J., et al., 2019. Effects of the divergent angle on bubble transportation in a rectangular Venturi channel and its performance in producing fine bubbles. International Journal of Multiphase Flow, 114: 192-206. DOI:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2019.02.003 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, L., Sun, L., Mo, Z., Tang, J., Hu, L., and Bao, J., 2018. An investigation on bubble motion in liquid flowing through a rectangular Venturi channel. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, 97: 48-58. DOI:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2018.04.009 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, Y., Li, H., and Sun, B., 2012. Multiphase Flow Parameters Measurement Based on Digital Image Processing Technology. Science Press, Beijing, 1-37.

(  0) 0) |

Zimmerman, W. B., Zandi, M., Hemaka Bandulasena, H. C., Tesar, V., James Gilmour, D., and Ying, K., 2011. Design of an airlift loop bioreactor and pilot scales studies with fluidic oscillator induced microbubbles for growth of a microalgae Dunaliella salina. Applied Energy, 88(10): 3357-3369. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.02.013 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22