2) Qingdao Fishery Technology Service Station, Qingdao 266071, China;

3) Qingdao Marine Management Support Center, Qingdao 266071, China;

4) Key Laboratory of Testing and Evaluation for Aquatic Product Safety and Quality, Laboratory of Quality & Safety Risk Assessment for Aquatic Products, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

Drug residue exceeding the recommended limits is one of the most important problems in the aquatic products' safety in China. The problem highly impacted the global trading of both marine and fresh water aquatic products from China. Therefore, it is of great significance to study drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics in aquatic animals, for improving our understanding on the underlying mechanism for controlling drug residues, and thus to provide a solid foundation for solving the problem of excessive drug residues and to boost the international reputations of Chinese aquatic products.

Enrofloxacin (ENR) is a third generation synthetic quinolone that is effective against most gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, mycoplasmas, chlamydia and rickettsia (Idowu et al., 2010). The majority of aquatic animal pathogens including Aeromonas salmonicida, Vibrio salmonicida, Vibrio anguillarum and Yersinia rucheri are sensitive to ENR (Bowser and Babish, 1991; Martinsen et al., 1992; Huang et al., 2019). ENR is therefore widely used to treat aquatic animal infections (Dalsgaard and Bjerregaard, 1991; Martinsen et al., 1992; Bowser et al., 1994; Maluping et al., 2005; Yang, 2005). ENR can be metabolized into active product of ciprofloxacin (CIP) in vivo. In recent years, residues of ENR and its metabolites were often found in aquaculture products because of the unreasonable usage of the drug. What is more serious is the increasing resistance of bacteria to these drugs that results in serious deterioration of the ecological environment and even threatening to human health. To ensure consumer's food safety, many countries and regions have regulated the maximum residue limit for ENR in aquatic products. The European Union (EU) stipulates the maximum residue limit of ENR in muscle of finned fish for 100 μg kg−1. The maximum residue limit of ENR in aquatic products is also 100 μg kg−1 in China.

Metabolism of drugs in aquatic animals is closely related to the administration mode and time, drug dosage, water temperature and so on. For the same drug, the metabolic time in vivo varies with the different method and time of administration or the different dosage. Pharmacokinetics of ENR have been widely studied in fingerling rainbow, Atlantic salmon, red pacu, sea bass, seabream, Korean catfish, brown trout, allogynogenetic silver crucian carp, turbot, snakehead fish, nile tilapia and largemouth bass (Bowser et al., 1992; Martinsen and Horsberg, 1995; Lewbart et al., 1997; Intorre et al., 2000; Rocca et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2006; Koc et al., 2009; Fang et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2015; Teles et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2019). With a HPLC, Li et al. (2009) evaluated the concentration of ENR in tissues of carp following intravenous and orally administration. The results indicated that intravenous administration led to more rapid absorption, less retaining time and higher peak concentration than orally administration. However, intravenous administration or/and intraperitoneal injection used in previous studies are not suitable for large-scale aquaculture practice. An oral administration with medicated feed is a more practical approach for disease control with a high fish population. The metabolism and pharmacokinetics of a drug might be greatly different depending on aquaculture species and drug administration mode.

Carp (Cyprinus carpio), with its delicious meat and rich nutrition, is one of the major fish species consumed in China (Fisheries and Fisheries Administration Bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture, 2021). Therefore, the aims of this study were to develop a HPLC-MS/MS method for determination of trace levels of ENR and its major metabolite CIP in different tissues of carp, and to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of ENR, after a single oral administration at a dosage of 40 mg kg−1 bw in medicated feed to carp. It is expected to provide a theoretical basis for establishing the withdrawal time of ENR in a more realistic practice of fish production and a reference for the rational and standardized usage of ENR in aquaculture industry.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Chemicals and ReagentsMethanol, acetonitrile and n-hexane were of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade and purchased from Merck Corporation (Darmstadt, Germany). Formic acid and ammonium acetate were of HPLC grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). ENR and CIP analytical standards were obtained from Dr. Ehrenstorfer GmbH (Augsburg, Germany). Anhydrous sodium sulfate was of superior pure grade purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, China). A Milli-Q system (Millipore, USA) was used to provide purified water in the laboratory. ENR hydrochloride crude drug (98.0% purity) was obtained from the National Aquatic Products Quality Inspection Center (Qingdao, China).

2.2 Instrumentation and Chromatographic ConditionsAnalysis of ENR and CIP was conducted with a Thermo Fisher TSQ Quantum Access system equipped with an ESI source and interfaced to a Surveyor HPLC system (Thermo Fisher, USA). Data were analyzed using Xcalibur Software, Version 2.0, after acquisition with the HPLC-MS/MS system supplemented with a Surveyor Autosampler and a MS Pump.

Mass spectrometry data were collected in positive ion mode with a Spray voltage of 4500 V, a sheath gas of 12 L·min −1, an auxiliary gas of 2 L min −1 and a transfer capillary temperature of 350℃. A multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was applied for the analytes' identification and quantification. The optimized parameters for the analytes and internal standards (ISs) were as follows. The quantitative ion pair were m/z 360/316 for ENR, m/z 332/288 for CIP, m/z 365/321 for ENR-D5 and m/z 340/322 for CIP-D8, and the qualitative ion pairs were m/z 360/245 for ENR, m/z 332/245 for CIP.

Chromatographic separation was performed on a Waters Xterra MS C18 column (3.5 μm, 2.1 mm×150 mm) (Phenomenex, USA). Gradient elution was used with the mobile phases (A) 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution including 5 mmol L−1 ammonium acetate and (B) methanol. The elution was conducted at a flow rate of 200 μL min−1 as follows: 0–0.5 min, 10% B; 0.5–2.0 min, 10%–90% B; 2.0–5.0 min, 90% B; 5.0–5.1 min, 90%–10% B; 5.1–7.0 min 10% B. The valve was set to direct LC flow to the mass spectrometer from 1.5 to 5.0 min with the remaining LC eluent diverted to waste.

2.3 Preparation of Stock and Working SolutionsThe primary stock solution of ENR, CIP and their internal standards ENR-D5 and CIP-D8 (1.0 mg mL−1) was prepared by dissolving an accurately weighed quantity of corresponding compound in methanol, respectively. The working solution of the mixture of ENR and CIP at a concentration of 1.0 μg mL−1 was prepared by serial dilution of the stock solution with methanol. This mixture and further dilutions were used for spiking of carp tissue samples. The working solution of the mixture IS (1.0 μg mL−1) was obtained by diluting the ENR-D5 and CIP-D8 stock solution with methanol. All stock solutions and working solutions were stored at 4℃ and brought to room temperature before use.

2.4 Calibration Standard and QC SamplesThe final concentrations of calibration standard samples were 2.0, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0, 50.0, 100 and 200 ng mL−1. Quality control (QC) samples were freshly and independently prepared at 3 concentration levels (low, medium and high), representing the entire range of calibration. The added volume was less than 5% of the total volume of the samples in order to maintain the integrity of the matrix. The final three concentration levels of QC samples were 2, 10, 40 μg kg−1 for ENR and CIP, respectively. All spiked samples were stored at −20℃. Fresh calibration standard samples and QC samples were prepared each day for method validation.

2.5 Sample PreparationTissue samples, including 2 mL plasma, 2 g muscle, 2 g gill, 2 g skin and 1 g liver, were spiked with 50 μL ENR internal standard solution (1 μg mL−1). After incubation in the dark for 10 min, 2 g anhydrous sodium sulfate was added and ENR was ultrasonically extracted using 8 mL acetonitrile containing 1% formic acid. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 4000 rmin−1 for 10 min. The sample was extracted two more times and the supernatants were combined. The combined extract was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen at 40℃ and then re-dissolved in 1 mL of the mobile phase solvent. The samples were further defatted by extracting with 2 mL n-hexane, then the aqueous phase was centrifugated at 14000 rpm and was filtered through a 0.22 μm cellulose acetate membrane. A volume of 10 μL of the solution thus prepared was used for HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

2.6 Validation of the Analytical MethodThe method was validated for selectivity, linearity, sensitivity, precision, accuracy, extraction recovery, and stability.

To check the potential interference of endogenous substances for analytes and IS in carp tissues, the selectivity was investigated by analyzing carp blank tissue samples (without analyte and IS) and compared with carp tissue samples spiked with IS at the concentration level of LOQ (the limit of quantification) (n = 6).

Linearity was assessed for ENR and CIP in the concentration range of 5–200 ng mL−1 at six concentration levels. The calibration curve was constructed by plotting the peak area ratios (y) of the analytes to IS against the spiked concentrations of the analytes (x) with a 1/x weighted linear least squares regression. LOQ is defined as the lowest concentration of spiked sample with the signal/noise ratio no less than 10, and was determined by the analysis of six replicates of LOQ samples in three separate validation batches. The accuracy of each LOQ samples should be within ± 20% with a precision no greater than 20%.

The intra-daily accuracy and precision were determined by analyzing ENR and CIP in different tissues of carp spiked with low, medium and high QC samples on one occasion. Whereas the inter-daily accuracy and precision were determined by analyzing ENR and CIP in different tissues spiked with the three concentration levels of QC samples on three consecutive separate occasions and with three separate calibration curves (one run for each day). The precision and the accuracy was expressed by relative standard deviation (RSD, %) and the relative errors (RE, %), respectively.

For the evaluation of the recoveries of ENR and CIP, different tissues of carp were spiked with low, medium and high QC concentration levels in six replicates for each level. The tissues thus spiked were then extracted, and the concentrations of the targeted analytes and IS were determined. The detected concentrations were compared with those regularly extracted QC samples to determine their recoveries, including the analytes and IS.

The stability of ENR and CIP determination in samples was studied under a variety of storage and handling conditions using low and high QC samples. For short-term and long-term stability, QC samples were exposed at room temperature for 8 h and stored at −20℃ for 7 d, respectively. And freeze-thawing stability was assessed by analyzing samples through three freeze-thawing cycles. These results were obtained by a comparison with the nominal values and were expressed in the relative standard deviation (RSDs, %) and REs (%).

2.7 Pharmacokinetic Study 2.7.1 Fish and acclimationHealthy carp (1000 g ± 50 g) were obtained from a local fishery farm and kept in a flow-through water tank for two weeks at 18℃ ± 1℃ and were fed once every morning and evening. Oxygen content was kept close to saturated levels by bubbling air through airy stones. Neither ENR nor CIP were found in the muscle, blood, skin, gill or liver of fishes tested in the control group before the start of the experiments.

2.7.2 Oral administration of ENRCrude drug of ENR hydrochloride was dissolved in distilled water with albumin added and was mixed into the feed. Then the feed was dried at 30℃ in an air oven dryer to a constant weight.

The fish were randomly divided into control and treatment groups. No ENR was given for the control group. For the treatment (medicated) group, ENR was administered with medicated feed at a dosage of 40 mg kg−1 bw. After one half-hour of the drug administration, the water was changed and the residual bait was removed. Dosed fish were fed continuously with commercial pellet feed (without ENR) the day after medication and for the rest of the experimental period. The experiments were performed at a water temperature of 18℃ ± 1℃.

2.7.3 Sampling of fish tissuesAfter oral administration, six fishes were sampled from each group at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, 36 h and 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 30, 40 and 80 d. At each time point of sampling, approximately 5 mL of blood was collected into syringes from the caudal artery of each fish and transferred to a centrifuge tube whose internal surface was covered with anticoagulant. Animals were then euthanized by concussion and muscle, liver, gill and skin were sampled. Plasma was isolated from a blood sample by centrifugation at 4000 rmin−1 for 10 min. All samples were stored at −20℃ until analysis with a HPLC-MS/MS method described above.

2.7.4 Pharmacokinetic analysisPharmacokinetic analysis was performed using the computer program Drug and Statistics (DAS version 2.0, Research Center for Clinical Drug, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China). The program used a compartmental open model based on non-linear regression analysis to analyze the concentration-time data for tissues.

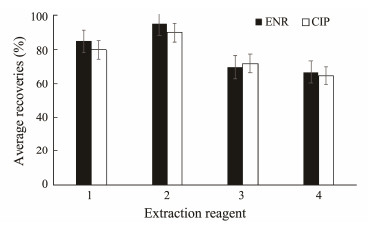

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 Method Development 3.1.1 Sample preparationClassical extraction reagents of ENR and CIP include pure organic solvents (acetonitrile, methanol, dichloromethane, etc.), buffer solution (phosphate buffer), organic solvents with a certain proportion of acid or alkali, and acetonitrile-water or methanol-water solution. It was found that the extraction efficiency of the pure organic solvents was low. Phosphate buffer was another choice as the extraction reagent, but it was time-consuming and laborious for passing through the SPE cartridge. When the acetonitrile-water was used as the extraction reagent, it is difficult to concentrate for extracts with a higher content of protein. In view of the fact that both ENR and CIP are soluble in weak acid solution and acetonitrile has a strong tissue permeability, we expect acetonitrile with formic acid could be a good choice for the extraction solvent. For comparison, samples of blank carp liver were spiked with standard ENR and CIP solutions at a concentration level of 20 μg kg−1, and extracted with different solvents. The concentrations of ENR and CIP were then determined according to the procedure described in Section 2.5 and the recoveries were calculated. The results showed that acetonitrile with 1% formic acid was easy to concentrate with an acceptable recovery (> 90% in any case at this concentration level) compared with other extraction reagents (Fig.1). Furthermore, our results in Section 3.2.4 also showed that all of the recoveries of ENR and CIP for different carp tissues were satisfactory while using acetonitrile with 1% formic acid as the extraction reagent. Therefore, acetonitrile with 1% formic acid was chosen for our method development.

|

Fig. 1 Averaged recoveries of ENR and CIP for carp liver samples at a spiking level of 20 μg kg−1, extracted with different reagents (n = 3 for each experiment). 1, acetonitrile with 2% formic acid; 2, acetonitrile with 1% formic acid; 3, dichloromethane; 4, acetonitrile. |

The addition of anhydrous sodium sulfate can effectively remove water and other impurities in the extracts. At the same time, sodium sulfate can also promote the denaturation and dispersion of proteins, to prevent the coagulation of samples for a better extraction. The defatting (removal of lipids and proteins) of the extracts was accomplished by using n-hexane after the concentration procedure, followed by centrifugation of the aqueous phase at 14000 r min−1 to remove proteins and other impurities. The results showed that the purification of samples was satisfactory for the subsequent HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

3.1.2 Optimization of mass spectrometric conditionsMass spectrometric optimization was performed by direct infusion of single analyte solutions of interest to HPLC-MS/MS. In order to optimize ESI conditions for ENR, CIP and IS, quadrupole full scans were carried out in both positive and negative ion detection modes, with a better response achieved in positive ionization. In the Q1 full scan, the protonated precursor [M+H]+ of ENR, CIP, ENR-D5 and CIP-D8 were m/z 360, 332, 365 and 340, respectively. Then in the MS2 scan, in order to obtain the maximum sensitivity, collision energy was chosen separately for each ion product, and the ion m/z 316, 288, 321 and 322 were selected as the quantification product ions of ENR, CIP, ENR-D5 and CIP-D8, respectively. Therefore, the ion transitions monitored for quantification were m/z 360/316 for ENR, m/z 332/288 for CIP, m/z 365/321 for ENR-D5 and 340/322 for CIP-D8. Other parameters were optimized and shown in Section 2.2. The chromatographic run was divided into two scan events, each containing a set of optimized MS parameters for the compounds of interest eluting within a given time period to ensure the highest sensitivity.

3.1.3 Optimization of liquid chromatographic conditionsA common and practical Waters Xterra MS C18 column (3.5 μm, 2.1 mm×150 mm) was used in our study. In order to achieve the maximum signal response and suitable retention time, the percentage of organic phase in the mobile phase at the beginning was low to ensure the retention of the analytes in the column. The retention time shortened with increasing the percentage of organic phase. In this study, methanol was selected as the organic phase due to its better selectivity compared with acetonitrile. The aqueous portion of the mobile phase was also optimized. The results showed that a good separation could be achieved by using a 0.1% formic acid solution (including 5 mmol L−1 ammonium acetate) as the aqueous portion of the mobile phase with gradient elution.

3.2 Validation of the Analytical Method 3.2.1 SelectivityTypical MRM chromatograms of blank carp tissue samples (muscle, liver, gill, plasma, skin), blank carp tissue samples spiked with ENR and CIP at LOQ levels, and the samples from carp tissues 4 h after administration are recorded under the above HPLC-MS/MS conditions. The chromatograms indicate that the targets are well separated at these conditions, with retention time of 3.03 min and 3.00 min for ENR and CIP, respectively. The results also illustrated that no significant interference from endogenous substances were observed at the retention times of the analytes with their concentrations in blank samples far below the LOQs (determined in Section 3.2.2).

3.2.2 Linearity and LOQsThe calibration curves were validated at six levels over the concentration range of 2.0–200 ng mL−1. Typical equations of the calibration curves and the correlation coefficient (r2) value were as follows:

| $ \begin{array}{l} y=2.3463 \times 10^{-3} x+3.9116 \times 10^{-4}, r^2=0.9999 \text { (for ENR), } \\ y=1.4754 \times 10^{-2} x-2.2909 \times 10^{-3}, r^2=0.9997 \text { (for CIP), } \end{array} $ |

where y represents the ratio of peak area of the analyte to that of IS, and x represents the concentration of the analyte. Good linearity of ENR and CIP in the concentration range was observed, with a LOQ of 2 μg kg−1 (defined as in Section 2.6) for both ENR and CIP.

3.2.3 Accuracy and precisionAssay precision was calculated using the relative standard deviation (RSD, %). Accuracy is described as the relative deviation in the calculated value (E) of a standard from that of its true value (T) expressed as a percentage (RE, %). It was calculated using the formula:

| $ R E(\%)=(E-T) / T \times 100. $ |

The results of accuracy and precision for ENR and CIP determination are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The RE% was in the range of −4.67% to 2.00% for ENR and of −6.93% to −2.33% for CIP. Both the intra-daily and inter-daily precisions were pretty good with RSDs less than 15%. These results met the acceptable criteria for bioanalytical purpose.

|

|

Table 1 Accuracy and precision for determination of ENR in different carp tissues |

|

|

Table 2 Accuracy and precision for determination of CIP in different carp tissues |

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the extraction recoveries were in the ranges of 97.4%–99.8%, 96.5%–102% and 95.3%–102% for ENR at low, medium and high levels, respectively; while they were 93.1%–97.5%, 94.0%–97.7% and 93.2%–97.9% for CIP at low, medium and high levels, respectively. These recoveries are concentration independent and are sufficiently high for a pharmacokinetics study.

3.2.5 StabilityAs can be seen in Table 3, at the three sample storage conditions tested, the RSDs were in the range of 3.19% to 5.22% with REs in the range of −4.98% to −2.25% for ENR, while the RSDs were 4.30% to 6.20% with REs in the range of −8.45% to −5.79% for CIP. These results demonstrated that the determination of ENR and CIP in carp tissues was stable throughout various sample storage process in the experiment.

|

|

Table 3 Stability of ENR and CIP determination in samples under various storage conditions (n = 6) |

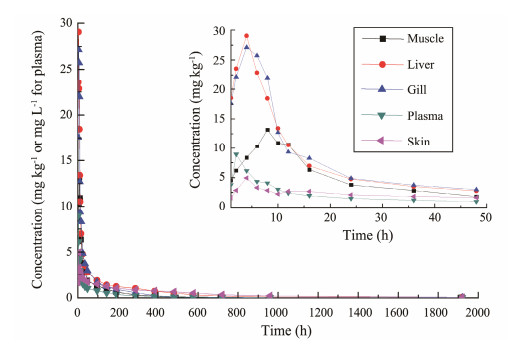

After a single oral administration of ENR to carps at a dosage of 40 mg kg−1 bw and a water temperature of 18℃ ± 1℃, the ENR concentration-time data from different tissues were best fit to a two-compartment open pharmacokinetic model with first-order absorption. The pharmacokinetic equations were:

| $ {C_{{\text{muscle}}}} = 21.06{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.08t}} - 22.61{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.27t}} + 1.55, $ |

| $ {C_{{\text{liver}}}} = 2.92{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.02t}} - 8.20{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.08t}} + 5.28, $ |

| $ {C_{{\text{gill}}}} = 38.27{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.11t}} + 3.16{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.01t}} - 41.43, $ |

| $ {C_{{\text{plasma}}}} = 0.06{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.07t}} - 1.04{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.07t}} + 0.98, $ |

| $ {C_{{\text{skin}}}} = 2.31{{\text{e}}^{ - 0.07t}} - 4.01{{\text{e}}^{ - 1.17t}} + 1.70 . $ |

The absorption half-lives (t1/2ka) of ENR in muscle, liver, gill, plasma and skin ranged from 0.59 to 9.35 h. The distribution half-lives (t1/2α) of the drug was the highest in liver and this value differs widely from the other tissues. The elimination half-lives (t1/2β) of the drug ranged from 104 to 310 h in the corresponding tissues (Table 4).

|

|

Table 4 Pharmacokinetic parameters of ENR after a single oral administration to carp at a dosage of 40 mg kg−1 bw and a water temperature of 18℃ |

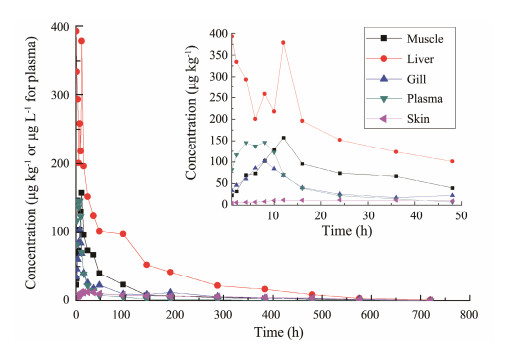

As early as 1 h after ENR administration, we could detect low levels of CIP in tissues. However, the CIP concentration-time data in plasma could not be described by a one- or two-compartment open model but by a non-compartmental model. The AUC0-t of CIP was the highest in liver with a half-life ranging from 84 to 318 h, depending on the tissue. The time to peak concentration in liver was 1 h, which is the shortest, indicating the metabolism of ENR to CIP in liver was the most rapid while it was the slowest in skin (Table 5).

|

|

Table 5 Pharmacokinetic parameters of CIP following a single oral administration of ENR to carp at a dosage of 40 mg kg−1 bw and a water temperature of 18℃ |

After a single oral ENR administration, ENR concentration level in plasma peaked at 8.94 μg mL−1 after 2 h, and a peak concentration of 13.15 mg kg−11 was observed in muscle after 8 h. All of the peak concentrations for liver, gill and skin occurred at 4 h. The peak concentrations (Cmax) were in the order of gill > liver > muscle > plasma > skin and the time to peak concentration (tmax) was the most rapid for plasma (Fig.2 and Table 4).

|

Fig. 2 ENR concentration-time profiles following a single oral administration of ENR at a dosage of 40 mg kg−1 bw and a water temperature of 18℃ (n = 6). |

CIP was detected after 1 h post-treatment in carp tissues at different times. However, CIP levels were significantly lower than ENR levels and the peak time was later than ENR except for liver. For an example, CIP peak concentration in muscle was 157.29 μg kg−1 with the peak occurring at 12 h, while ENR peak concentration in muscle was 13.15 mg kg−1 with the peak at 8 h (Fig.3 and Table 5).

|

Fig. 3 CIP concentration-time profiles following a single oral administration of ENR at a dosage of 40 mg kg−1 bw and a water temperature of 18℃ (n = 6). |

In plasma, the k12 value was lower than the k21, indicating that ENR stayed in the central compartment longer than in the peripheral compartment. Therefore, ENR distribution (from the central compartment to the peripheral compartment) was slow in plasma. In contrast, k12 was higher than k21 in muscle, gill and skin, suggesting that ENR remained in the peripheral compartment longer.

The t1/2β values were different in different tissues. It was the longest in skin, and the shortest in gill. Correspondingly, the k10 value in skin was the smallest and that in gill was the largest, suggesting a slow elimination rate from skin and a rapid rate from gill. We found a t1/2β value of 132.37 h in carp plasma at a water temperature of 18℃, which is similar to two other studies (Liang et al., 2010, 2012). But it differs from the 25 h reported for seabass at 15℃, 42.1 h for koi carp at 27–28℃, 161.10 h for European eel at 23–25℃, 64.66 h for crucian carp at 25℃ and 90.79 h for largemouth bass at 28℃ (Intorre et al., 2000; Fang et al., 2007; Udomkusonsri et al., 2007; Fan et al., 2017; Shan et al., 2019). Water temperature affects the kinetic profile of many drugs, and a temperature increment of 1℃ corresponds to a 10% increase in the metabolic and excretory rates in fish (Bowser et al., 1992; Kleinow et al., 1994; Rigos et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2019, Luo et al., 2020). However, species-specific differences and altered experimental conditions may also affect this property.

After a single oral administration of ENR to carp, the highest Cmax was found in gill (37.12 mg kg−1), followed by liver (29.05 mg kg−1), muscle (13.15 mg kg−1), plasma (8.94 mg kg−1) and skin (4.95 mg kg−1). This order correlates well with the primary excretory routes in the gill and liver. The Cmax values in our study were higher than those previously reported (Fang et al., 2012, 2015) and maybe caused by a high feed concentration (Yang, 2005) used in this study. We found that the Cmax in gill and liver were 2.82 and 2.21 times higher than that in muscle, respectively, which was similar to the result reported by Liang et al. (2012).

The AUC is a measure of the amount of drug entering the body and is an important indicator of drug absorption in fish tissues. After ENR administration, the AUC values of ENR in carp tissues were in the order of liver > gill > skin > muscle > plasma. The AUC in carp liver was almost twice that in muscle, while that in plasma was half that in muscle. The AUC in each tissue differs greatly at the same ENR dosage, indicating that the ENR accumulation capacity was different between carp tissues. The accumulation ability of liver was higher than any other tissues. This is similar to results previously reported for many other animals indicating that most of the absorbed drugs accumulate in liver and then released slowly into the blood for peripheral distribution (Xu et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2017; Meng et al., 2019).

The apparent distribution volume (Vd) of ENR was 4.40 L kg−1 in plasma of carp after oral administration. The calculated values indicated an adequate distribution from plasma to peripheral compartmental tissues. This Vd value in carp plasma was larger than the 1.5 L kg−1 found in koi carp, 2.56 L kg−1 in fingerling rainbow trout, 2.57 L kg−1 in Fenneropenaeus chinensis and 2.21 L kg−1 in largemouth bass (Bowser et al., 1992; Fang et al., 2004; Udomkusonsri et al., 2007; Shan et al., 2019). However, our result was similar to those found for turbot with Vd values of 3.96 and 4.97 L kg−1 after oral administration of ENR at 16 and 18℃ (Liang et al., 2012).

3.3.4 Metabolism of ENREnrofloxacin is de-ethylated to CIP in many animal species (Idowu et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2019). In terrestrial animal tissues, the corresponding AUC ratios of CIP to ENR ranged from 35% to 55% (Fang et al., 2007). However, in aquatic animals, the rate of transformation of ENR to CIP is significantly less. For instance, CIP in F. chinensis hemolymph was detected with an AUC ratio of CIP to ENR at 1.2% (Fang et al., 2004). Ciprofloxacin was also detected after intravenous and oral administration of ENR to Korean catfish with AUC ratios of CIP to ENR at 4.44% and 3.33%, respectively (Kim et al., 2006). In sea bass, CIP was detected occasionally in plasma at concentrations close to the LOD, while it was at concentrations significantly lower than those of ENR in liver and other tissues (Intorre et al., 2000). Ciprofloxacin was also found after oral administration of ENR in red pacu (Lewbart et al., 1997). However, CIP was not detected in serum samples of the seabream after intravenous and oral administrations of ENR (Rocca et al., 2004).

In our present study, the AUC ratio of CIP to ENR in carp muscle was 1.54%, similar to that reported by Fang et al. (2004). We also determined CIP concentration levels in each other tissue of carp, which has not been routinely done in previously reported studies (e.g., Intorre et al., 2000; John et al., 2020) and may be related to the analytical method used for quantitation. The HPLC-MS/MS method used in this study allowed the simultaneous qualitative and quantitative determination of ENR and of its main metabolite CIP. This represents an advantage compared with the HPLC methods used in other studies and also possesses a higher sensitivity and selectivity.

3.3.5 Withdrawal time of ENR and CIPThe national standard of the People's Republic of China GB31650-2019 provides a value of 100 μg kg−1 as the maximum residue limit of ENR in muscle (expressed as the total of ENR and CIP). We studied the elimination of ENR in muscle in order to determine the withdrawal time of ENR in fish products destined for consumer market. The drug concentration (calculated as the sum of ENR and CIP) in edible muscle tissue of carp was monitored, and the elimination time was then determined to be 24 d when the drug concentration in carp muscle dropped to below 100 μg kg−1.

However, it should be noted that there are many factors affecting the pharmacokinetics and residue elimination times in aquatic animals, including animal species and physiological differences, drug dosage, route of administration, water temperature, salinity and pH. Among these factors, we found that water temperature is the most influential factor. The suggested withdrawal time (24 d in this study) was obtained under the experimental conditions (18℃ water temperature, single bait administration at a dosage of 40 mg kg−1 bw). And the clinical withdrawal time should be determined according to the specific fish species and the actual breeding environmental conditions.

4 ConclusionsA rapid and sensitive HPLC-MS/MS method was developed and validated for simultaneous quantitation of ENR and CIP in carp tissues. The method was successfully applied to the pharmacokinetic study of ENR and CIP in carp after a single oral administration of ENR in medicated feed. The results revealed that ENR was metabolized mainly in the form of prototype drug after entering into the carp tissues, and only 1.54% of de-ethylation of ENR occurred. The total concentration of ENR and CIP in edible muscle tissue of carp was below 100 μg kg−1 after 24 days at a water temperature of 18℃.

AcknowledgementThe study was supported by the Central Public-Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (No. 20 20TD71).

Bowser, P. R., and Babish, J. G., 1991. Enrofloxacin in salmonids. Veterinary and Human Toxicology, 33(S1): 46-48. (  0) 0) |

Bowser, P. R., Wooster, G. A., and Hsu, H. M., 1994. Laboratory efficacy of enrofloxacin for the control of Aeromonas salmonicida infection in rainbow trout. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 6(4): 288-291. DOI:10.1577/1548-8667(1994)006<0288:LEOEFT>2.3.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Bowser, P. R., Wooster, G. A., St. Leger, J., and Babish, J. G., 1992. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in fingerling rainbow trout (Oncorhynhus mykiss). Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 15: 62-71. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2885.1992.tb00987.x (  0) 0) |

Dalsgaard, I., and Bjerregaard, J., 1991. Enrofloxacin as an antibiotic in fish. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 87: 300-302. (  0) 0) |

Fan, J., Shan, Q., Wang, J., Liu, S., Li, L., and Zheng, G., 2017. Comparative pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in healthy and Aeromonas hydrophila-infected crucian carp (Carassius auratus gibelio). Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 40(5): 580-582. DOI:10.1111/jvp.12392 (  0) 0) |

Fang, W. H., Yu, H. J., Cai, Y. Q., Zhou, K., and Huang, D. M., 2007. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in European eel (Anguilla anguilla) after a single oral gavage. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 14(4): 622-629 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-8737.2007.04.014 (  0) 0) |

Fang, X., Liu, X., Liu, W., and Lu, C., 2012. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in allogynogenetic silver crucian carp, Carassius auratus gibelio. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 35: 209-212. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2011.01309.x (  0) 0) |

Fang, X., Zhou, J., and Liu, X., 2015. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in snakehead fish, Canna argus. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 39: 209-212. (  0) 0) |

Fang, X. X., Wang, Q., and Li, J., 2004. Pharmacokinetics of enroflxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in Fenneropenaeus chinensis. Journal of Fisheries of China, 28: 36-41 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Fisheries and Fisheries Administration Bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture, 2021. China Fishery Statistical Yearbook. China Agriculture Press, Beijing, 24.

(  0) 0) |

Huang, Z. Y., Fang, L. X., Song, C., Fan, L. M., Meng, S. L., Qiu, L. P., et al., 2019. Antibiotic enrofloxacin in fishery: A review. Journal of Agriculture, 9(11): 57-62 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Idowu, O. R., Peggins, J. O., Cullison, R., and Bredow, J., 2010. Comparative pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in lactating dairy cows and beef steers following intravenous administration of enrofloxacin. Research in Veterinary Science, 89: 230-235. DOI:10.1016/j.rvsc.2009.12.019 (  0) 0) |

Intorre, L., Cecchini, S., Bertini, S., Cognetti, A. M., Soldani, G., and Mengozzi, G., 2000. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in the seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquaculture, 182(1-2): 49-59. DOI:10.1016/S0044-8486(99)00253-7 (  0) 0) |

John, A. G., Gregory, A. L., and Mark, G. P., 2020. Population pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in clinically diseased or injured eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina carolina), yellow-bellied sliders (Trachemys scripta scripta), and river cooters (Pseudemys concinna). Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 43(2): 222-230. DOI:10.1111/jvp.12843 (  0) 0) |

Kim, M. S., Lim, J. H., Park, B. K., Hwang, Y. H., and Yun, H. I., 2006. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in Korean catfish (Silurus asotus). Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 29: 397-402. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2006.00783.x (  0) 0) |

Kleinow, K. M., Jarboe, H. H., Shoemaker, K. E., and Greenless, K. J., 1994. Comparative pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of oxolinic acid in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science, 51(5): 1205-1211. DOI:10.1139/f94-120 (  0) 0) |

Koc, F., Uney, K., Atamanalp, M., Tumer, I., and Kaban, G., 2009. Pharmacokinetic disposition of enrofloxacin in brown trout (Salmo trutta fario) after oral and intravenous administrations. Aquaculture, 295: 142-144. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.06.004 (  0) 0) |

Lewbart, G., Vaden, S., Deen, J., Manaugh, C., Whitt, D., Doi, A., et al., 1997. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in the red pacu (Colossoma brachypomum) after intramuscular, oral and bath administration. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 20: 124-128. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2885.1997.00814.x (  0) 0) |

Li, C. Y., Li, J. C., Lu, T. Y., Wang, D., and Hou, X. L., 2009. Pharmacokinetic of enrofloxacin in carp following different ways of administration. Journal of Jimei University (Natural Science), 14(3): 234-239 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Liang, J. P., Li, J., Zhang, Z., Wang, Q., Liu, D. Y., and Wang, J. Q., 2010. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in plasma of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) after a single intramuscular and oral administration. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 6: 1122-1129. (  0) 0) |

Liang, J. P., Li, J., Zhao, F. Z., Liu, P., and Chang, Z. Q., 2012. Pharmacokinetics and tissue behavior of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in turbot Scophthalmus maximus at two water temperatures. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 30(4): 644-653. DOI:10.1007/s00343-012-1228-2 (  0) 0) |

Luo, J. J., Zhang, X. Z., Song, Y., Jiang, X. Y., Lai, C. Q., Liu, C. Z., et al., 2020. Metabolism and elimination of enrofloxacin and its metabolites in Acipenser gueldenstaedtii at different water temperature. Journal of Food Safety and Quality, 11(6): 1749-1757 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Luo, J. J., Zou, R. J., Song, Y., Huang, H., Han, D. F., Li, J. W., et al., 2019. Metabolism and elimination rule of enrofloxacin and its metabolites in Carassius auratus gibelio. China Animal Health Inspection, 36(7): 95-103. (  0) 0) |

Maluping, R. P., Lavilla-Pitogo, C. R., DePaola, A., Janda, J. M., Krovacek, K., and Greko, C., 2005. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Aeromonas spp., Vibrio spp. and Plesiomonas shigelloides isolated in the Philippines and Thailand. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 25(4): 348-350. (  0) 0) |

Martinsen, B., and Horsberg, T. E., 1995. Comparative single-dose pharmacokinetics of four quinolones, oxolinic acid, flumequine, sarafloxacin, and enrofloxacin, in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) held in seawater at 10℃. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 39(5): 1059-1064. (  0) 0) |

Martinsen, B., Oppegaard, H., Wichstrom, R., and Myhr, E., 1992. Temperature-dependent in vitro antimicrobial activity of four 4-quinolones and oxytetracycline against bacteria pathogenic to fish. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 36(8): 1738-1743. (  0) 0) |

Meng, Y., Zhu, X. H., Li, B. P., Chen, X. H., Shen, M. F., Yang, H. S., et al., 2019. Residues elimination rules of enrofloxacin and its metabolites in channel catfish (Ietalurus puntaus) under pond culture conditions. Journal of Huazhong Agricultural University, 38(1): 97-102 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Rigos, G., Alexis, M., Andriopoulou, A., and Nengas, I., 2002. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of oxytetracycline in sea bass, Dicentrarchus iabrax, at two temperatures. Aquaculture, 210: 59-67. (  0) 0) |

Rocca, G. D., Salvoa, A., Malvisia, J., and Sellob, M., 2004. The disposition of enrofloxacin in seabream (Sparus aurata L.) after single intravenous injection or from medicated feed administration. Aquaculture, 232(1-4): 53-62. (  0) 0) |

Shan, Q., Wang, J. X., Zheng, G. M., Zhu, X. P., Yang, Y. H., Ma, L. S., et al., 2019. Pharmacokinetics and tissue residues of enrofloxacin in the largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) after oral administration. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 43(2): 147-152. (  0) 0) |

Teles, J. A., Castello, L. C., Del, M., Pilarski, F., and Reyes, F. G. R., 2016. Pharmacokinetic study of enrofloxacin in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) after a single oral administration in medicated feed. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 39(2): 205-208. (  0) 0) |

Udomkusonsri, P., Arthitvong, S., Klangkaew, N., and Kusucharit, N., 2007. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in koi carp (Cyprinus carpio) after various routes of administration. Kasetsart Journal (Nature Science), 41(5): 62-68. (  0) 0) |

Xu, W. H., Lin, L. M., Zhu, X. B., Wang, X. T., and Kang, X. L., 2004. Residues of enrofloxacin and its metabolite in Jifu Tilapia and Penaeus chinensis. Fisheries Science, 23(7): 5-8 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang, Q. H., AI, X. H., Liu, Y. T., Xu, N., and Zhao, F., 2017. Studies on elimination dynamics of enrofloxacin residues and its metabolites in channel catfish at two different water temperatures. Acta Hydrobiological Sinica, 41(4): 781-786 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang, X. L.

, 2005. New Handbook of Fishery Medicine. China Agricultural Press, Beijing, 208-209 (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22