2) Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Xiamen 361005, China;

3) Research Center for Oceanography, Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jakarta 11048, Indonesia;

4) Observation and Research Station of Coastal Wetland Ecosystem in Beibu Bay, Ministry of Natural Resources, Beihai 536015, China

Mangrove forests along the tropical and subtropical coasts have high levels of biological productivity (Alongi, 2009) and rich diversity of benthic fauna as an important component of the ecosystem (Chen et al., 2013). Man-grove plants provide organic matter and nutrients critical to the benthic fauna primarily through litterfall (Kieckbusch et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2013). In addition, the com-plex aboveground structures of mangrove plants provide the physical structure for benthic fauna to inhabit and pro-tect them from environmental stresses and predators (Chen et al., 2013).

The benthic fauna plays an important role between the mangrove detritus at the base of the food web and the consumers at higher trophic levels in mangrove ecosystems (Macintosh, 1980). The knowledge of the importance of autotrophic sources in supporting the faunal community is fundamental for understanding the relationship between fauna and flora in different environments, which is vital for the development of conservation priorities and effec-tive management policies for ecosystems (Connolly et al., 2005).

Mangrove-derived organic carbon generally contributes a majority of food sources for benthic fauna within man-grove forests (Giarrizzo et al., 2011; Abrantes et al., 2015). In addition to mangrove materials, macrobenthos can also utilize other organic matters, such as autochthonous micro-and macrophytobenthos, and tidally imported allochtho-nous sources, including plankton-or seagrass-derived or-ganic matters (Bouillon et al., 2004; Kieckbusch et al., 2004; Thimdee et al., 2004). Sesarmid crabs, as the most common crustacean group in mangrove forests, are main-ly dependent on the mangrove leaf litter; however, they also utilize sediments and invertebrates to supplement their food sources (Lee et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2016). Fiddler crabs in mangrove forests, represented by Uca spp., are mainly deposit feeders (Hsieh et al., 2002; Meziane and Tsuchiya, 2002). Therefore, the food sources of benthic fauna in mangrove forests are suggested to be partly re-lated to the composition of the sedimentary organic mat-ter in mangroves (Bouillon et al., 2004). Where the man-grove forest receives substantial exogenous carbon sources, such as plankton, macroalgae and seagrass, these sources also play important roles in sustaining secondary produc-tion (Bouillon et al., 2002; Kieckbusch et al., 2004; Thimdee et al., 2004).

Indonesia, with a total mangrove area of 31100 km2, represents the global hotspot in terms of mangrove extent (Giri et al., 2011), while the trophic relationship between mangroves and benthic fauna is currently poorly under-stood in this area. In this study, the primary food sources of epifauna and sediment carbon sources were investi-gated in an oceanic mangrove forest in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Recent studies have found that the mangrove sediments in this area were rich in organic carbon (Murdiyarso et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018), and the sediments mainly consisted of mangrove detritus (Chen et al., 2018). Whether the mangrove-derived organic carbon could make an important contribution to the food sources of epifauna in the oceanic mangrove forest was further tested in this study. We hypothesized that the mangrove-derived orga-nic carbon comprises the majority of the sediment organic carbon and the mangrove carbon generally provides ma-jor food sources for epifauna.

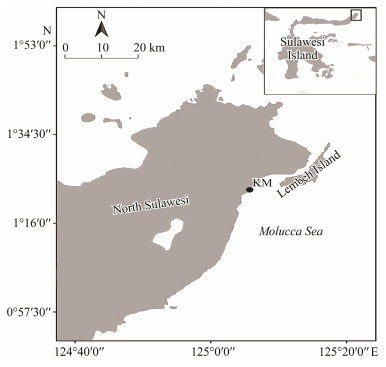

2 Methods 2.1 Study AreaThe study was conducted in a mangrove forest located in Kema (1°22'56.47 〞N, 125°5'43.65〞E) in North Sula-wesi, Indonesia (Fig. 1). The mangrove forest, dominated by Rhizophora apiculata Bl., extends about 200 m from its land fringe to the sea fringe. Seagrass meadow dominated by Enhalus acoroides (Linnaeus f.) Royle, 1839 and Tha-lassia hemprichii (Ehrenberg) Ascherson, 1871 occurs at the sea fringe of the forest (Chen et al., 2017). This area has a typical equatorial climate, and the mean tempera-tures at sea level are nearly uniform, varying by only a few degrees throughout the year, from 20 to 28℃. Tides in this area are mixed and mainly semidiurnal and fluctuate slightly, with an annual tidal range of 2.4 m (Chen et al., 2017).

|

Fig. 1 Location of the sampling sites. |

Samples were collected in August 2015 (dry season). The individuals of epifauna on the mud surface, in burrows and prop root gaps near the ground, and on the trees were collected. In the sampling area, surface sediment samples (6 replicates) were collected to a depth of 5 cm using hand-held PVC corers (inner diameter 70 mm). The epifauna and sediment samples were kept in a cool box and transported to the laboratory. The epifauna were identified and divi-ded into four feeding guilds, including carnivorous, omnivorous, phytophagous, and planktophagous (Lai and He, 1998; Vannini et al., 2001; Alfaro, 2008; Poon et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2016; Quan et al., 2018).

We defined the potential primary sources for sediment carbon and the food sources of epifauna as mangrove-de-rived organic carbon, imported seagrass-derived organic carbon and suspended particulate organic matter (SPOM) by tides in this study. Macroalgae was not taken into ac-count as a source because it was not observed within the forest. Senescent leaves of R. apiculata, representing the initial stage of leaf material entering the food web, were collected from 9 different trees by shaking the trunk, and five leaves from each tree were combined into one sample. To collect the SPOM, seawater that is far away from man-grove and seagrasses was collected in a plastic bottle. After passing through a 75 μm mesh, it was filtered through a precombusted 0.7 μm GF/F filter (Whatman) in the labo-ratory. For seagrass, leaf samples were collected in three replicate quadrats of 625 cm2 at the sea fringe of the man-grove forest, and the tissues were cleaned to remove epi-phytes and sands.

2.2 Sample AnalysisFor crabs, the muscle tissue of the whole body was used for isotopic analysis after removal of the gut and intesti-nal system. The muscle tissues of mollusks were removed from their shell and analyzed together. For the small snail Optediceros breviculum, five or six individuals were pool-ed into one sample. All fauna samples were ground into fine powder after freeze drying. Plant tissues were dried at 60℃ for 24 h and the sediment samples were air-dried after removing the visible animals, plant residues and stones (Chen et al., 2017). For isotopic analysis, all ground sam-ples of epifauna, seagrass leaves and sediments were placed into silver cups, acidified with diluted HCl (5%) and then oven dried at 40℃ to remove the carbonates. Filtered samples of SPOM for isotope analysis were acidified by fuming overnight over 1 mol L-1 HCl to remove inorganic carbonates. No acidification was done for mangrove sam-ples, because no carbonate was expected to be present in the leaves.

The carbon and nitrogen isotopic compositions of the samples were measured using a Thermo Flash EA 1112 HT-Delta V Advantages system. The stable isotopic composi-tions were reported in the δ notation (‰) as the ratio of the heavy (13C or 15N) to the light (12C or 14N) stable iso-tope in the sample (Rsample) relative to that of a standard (Rstandard), i.e., δX = 1000 × [(Rsample/Rstandard)-1], with the standard being Vienna Peedee Belemnite (VPDB) for car-bon and atmospheric N2 for nitrogen and R = 13C/12C or 15N/14N.

2.3 Statistical AnalysesThe differences in carbon and nitrogen isotopic compositions among the three primary food sources were com-pared using the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test, per-formed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0, Chicago, IL, USA). The potential contributions of the three primary sources to sediment carbon composition and epifauna diet were estimated using a Bayesian stable isotope mixing model, SIMMR. The SIMMR model required the input of values representing isotopic shifts between consumers and their potential food sources (trophic enrichment factors, TEFs). The TEF of δ15N was 3.3‰ ± 0.26‰ for the car-nivorous group and was 2.2‰ ± 0.3‰ for the other three feeding groups; for δ13C, the TEF was 1.3‰ ± 0.3‰ for all feeding groups (McCutchan et al., 2003; Park et al., 2017).

3 Results 3.1 δ13C and δ15N Values of the Primary Sources and SedimentThree primary food sources can be clearly distinguished in the dual-isotope signatures (Table 1). Mangrove leaves had the most negative δ13C value (-30.11‰) among the three primary sources, while the most enriched δ13C was measured in seagrass leaves. Mangrove and seagrass leaves had the highest δ15N values (about 4‰). Mangrove sedi-ment was more δ13C-depleted than the other two alloch-thonous sources (seagrass leaves and SPOM), and its δ13C value was closer to that of mangrove leaves than to the values of these two sources. The SIMMR model analysis results showed that mangrove-derived carbon contributed 64.90% of the organic carbon in the benthic sediment.

|

|

Table 1 δ13C and δ15N values of the primary sources and the proportional contributions of different sources to sediment organic carbon in Kema mangrove forest |

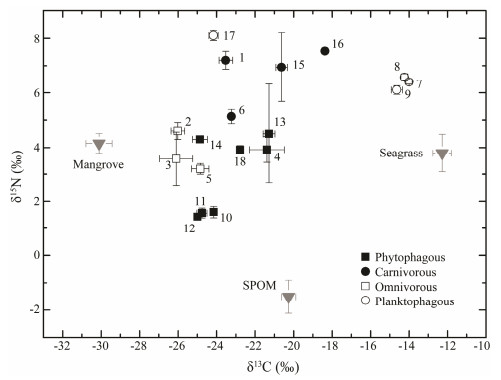

A total of 18 epifauna species (some individuals were identified only to genus) were collected from the Kema mangrove forest, including 6 crustacean species, 3 bivalve species and 9 gastropod species (Fig. 2 and Table 2). These species were classified as carnivorous (4 species), omni-vorous (3 species), phytophagous (7 species), and plank-tophagous (4 species).

|

Fig. 2 Dual-isotope plots of δ13C and δ15N (mean and standard deviation) for epifauna samples and their potential food sources. 1, Epixanthus dentatus; 2, Parasesarma semperi; 3, Sesarma sp.; 4, Tubuca coarctata; 5, Metopograpsus frontalis; 6, Penaeus sp.; 7, Anadara antiquata; 8, Anadara sp.; 9, Callista erycina; 10, Littoraria scabra; 11, Littoraria pallescens; 12, Littoraria articulata; 13, Pirenella cingulata; 14, Terebralia sulcata; 15, Chicoreus capucinus; 16, Bedevina birileffi; 17, Optediceros breviculum; 18, Nerita chamaeleon. |

|

|

Table 2 Species of epifauna collected from the Kema mangrove forest and their feeding guilds |

The epifauna had a broad range of δ13C values, from -26.10‰ to -13.80‰, and the δ15N values varied from 1.44‰ to 9.46‰ (Fig. 2). The most depleted δ13C, about -26‰ for the two sesarmid crabs, was closer to the man-grove signal than those of other primary sources, and it was 4‰ more enriched than mangrove signal. The three bi-valve species, i.e., Anadara antiquata, Anadara spp. and Callista erycina, had the highest δ13C values (about -14‰) and were about 2‰ more depleted than the seagrass sig-nal. The three littorinid species showed little variability in δ15N value, ranging from 1.44‰ to 1.60‰, and their δ13C values lied between those of the mangrove and SPOM signals. The δ13C and δ15N values of the epifauna did not differ significantly among the four feeding guilds.

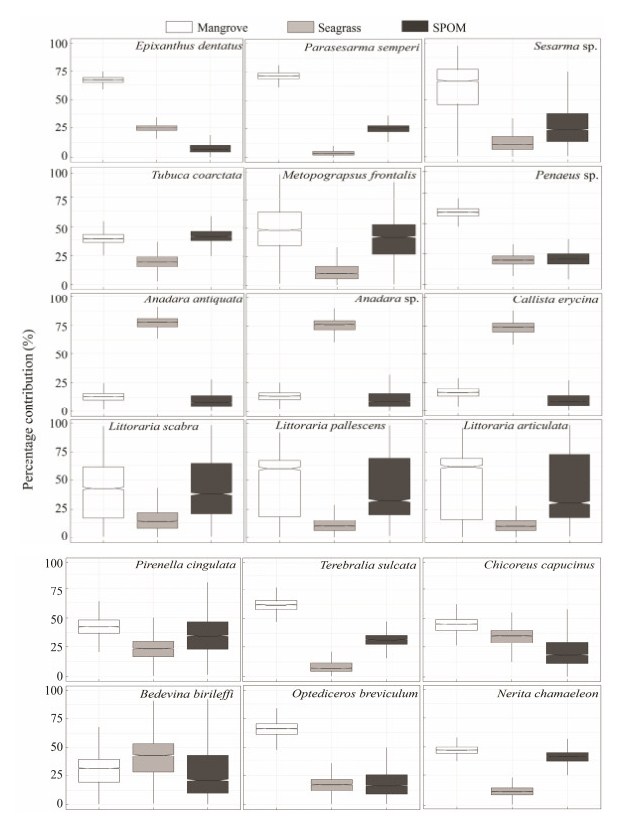

3.3 Potential Food Sources of the EpifaunaThe SIMMR mixing model estimations showed a dis-similarity in the composition of primary food sources as-signed to different epifauna species (Fig. 3). Overall, man-grove-derived carbon predominantly comprised the food sources of epifauna of variable feeding guilds, including Epixanthus dentatus, Parasesarma semperi, Penaeus sp., Optediceros breviculum, Terebralia sulcata and Littora-ria spp. The highest proportional contribution of mangrove was 71.7% for P. semperi, with E. dentatus following. For the three littorinid species and T. coarctata, mangrove-de-rived carbon and SPOM made a similar contribution to their food sources. Seagrass was found to dominate the food sources of three planktophagous species, A. antiquata, Ana-dara sp. and C. erycina.

|

Fig. 3 Boxplots representing the potential proportional contributions of the primary food sources to the diets of epifauna in the Kema mangrove forest. The centerline in the box is the median of all solutions and the box is drawn around the 25th and 75th quartiles, thus, representing 50% of the solutions. |

Mangrove detritus is generally the major source of the accumulated carbon in mangrove sediments, while allo-chthonous organic matter may provide high OC inputs to the sediments when a high rate of input from riverine or tidal sources occurs (Jennerjahn and Ittekkot, 2002). The surface sediment in the Kema mangrove had a δ13C value close to that of the mangrove signature which is about 2‰ more enriched in δ13C than the mangrove leaves, while the sediment organic carbon was primarily comprised of the autochthonous mangrove source. The more depleted δ13C and higher proportional contribution of mangrove to sediment organic carbon measured in this study and in another oceanic mangrove in North Sulawesi (Chen et al., 2018) than those in other estuarine mangrove forests (Xue et al., 2009; Ranjan et al., 2011), which may suggest a more important role of autochthonous mangrove source in sedi-ment carbon accumulation in the oceanic mangrove for-ests.

Although seagrass meadow occurred at the seaward fringe of the mangrove forest, seagrass-derived carbon had a much lower contribution than that of mangrove carbon. This was similar to our previous finding that mangrove-derived car-bon accounted for > 80% of the sediment organic carbon at another oceanic mangrove adjacent to seagrass meadow in Wori, North Sulawesi (Chen et al., 2018). A recent study also suggested that mangrove forests could export carbon to their adjacent seagrass meadows, and mangrove detri-tus contributed a higher proportion than that of autoch-thonous seagrass to the sediment organic carbon in tropi-cal areas (Chen et al., 2017).

4.2 Contribution of Mangrove-Derived Carbon to the Food Sources of EpifaunaNumerous studies have demonstrated that in mangrove forest which receives allochthonous organic matter inputs, the mangrove materials have limited importance to the diet of consumers associated with the mangrove habitat (Bouillon et al., 2002; Kieckbusch et al., 2004; Thimdee et al., 2004). For instance, the major food source of the benthic fauna in an estuarine mangrove was attributed to SPOM rather than to mangrove tissues (Yang et al., 2017). However, higher uptake of mangrove carbon by benthic consumers is usually accompanied by a decrease in the importance of allochthonous carbon input in the sediment (Bouillon et al., 2002). The present study found that the mangrove-derived carbon was the major food source for the majority of the epifauna collected in Kema mangrove forest, where the sediment carbon was mainly comprised of mangrove source. This was consistent with a previous finding that mangrove carbon could be an important source for consumers in a habitat where other primary sources are much less available (Giarrizzo et al., 2011). Al-Maslamani et al. (2013) also suggested that the fauna resident within an arid mangrove forest with a small amount of inwelling carbon were mainly dependent on local retained nutrients (Al-Maslamani et al., 2013). The contribution of mangrove carbon could be up to 84% for prawn tissues in a Malaysia mangrove forest where the sediment mainly contained mangrove detritus (Chong et al., 2001).

The δ13C and δ15N values of the epifauna collected in this study were not clearly distinguished among the four feeding guilds, and mangrove-derived carbon could be the major food sources for epifauna belonging to different feeding guilds. In addition to those phytophagous species, e.g., sesearmid crabs which mainly feed on mangrove tis-sues (Chen et al., 2014), some epifauna of other feeding guilds are deposit feeders (Hsieh et al., 2002; Meziane and Tsuchiya, 2002) and could uptake mangrove detritus during scraping materials from the sediment surface. We therefore suggest that mangrove-derived carbon can directly (via grazing plant tissues) or indirectly (via deposit feedings) make an important contribution to the food sources of epifauna in Kema mangrove forest where the allochtho-nous input of organic carbon is low.

In this study, benthic diatoms were not taken into ac-count, although they have also been recognized as an im-portant primary food source for the benthic fauna (Bouil-lon et al., 2002). Considering the benthic diatoms had higher δ13C values (-20.6‰ -12.1‰) than the mangrove signa-ture (Newell et al., 1995; Bouillon et al., 2002), the pro-portional contribution assigned to the mangrove source in this study might be underestimated. The food sources of benthic fauna will be investigated in the future consider-ing benthic diatoms as one potential food source.

4.3 Food Sources of Different Faunal GroupsThe highest contribution of mangrove-derived carbon to the food source was found in P. semperi crabs, con-sistent with previous findings that sesarmid crabs relied on mangrove source (Kristensen et al., 2010). However, sesarmid crabs must use supplementary N sources, inclu-ding sediments and invertebrates, as mangrove leaves are high in the C:N ratio and the crabs are capable of utilizing carbon but not nitrogen from leaf litter (Lee, 1997; Thongtham and Kristensen, 2005). The sediment in the Kema mangrove forest had a δ13C signature similar to that of mangrove leaves, and the P. semperi crabs were 1.3‰ more enriched in δ13C signature than mangrove sediment, sug-gesting that the crabs could also use other sources for food. A recent study found that macroalgae could even domi-nate the food source of sesarmid crabs over mangrove tis-sues when the macroalgae was present in the forest (Gao et al., 2018).

Littorinid snails are generally herbivores, grazing on mi-croalgae, filamentous algae, bacteria, and mangrove tis-sues. Their dietary differences appear to be related to food composition and abundance on different parts of the man-grove trees where they attach rather than active food se-lection (Alfaro, 2008). The δ13C values of the three lit-torinids in this study varied within a narrow range from -25.09‰ to -24.14‰, indicating a similarity in their diets, which were mainly comprised of mangrove and SPOM. There was a difference in food source between two pota-midid snails, P. cingulata and T. sulcata, with T. sulcata relying more on the mangrove source. However, T. sul-cata collected from an estuarine mangrove in Vietnam showed a δ13C value close to those of sources other than mangrove plants (Tue et al., 2012).

Previous studies showed that the δ13C value of fiddler crabs, representing another important faunal group, was generally higher than that of the mangrove signature (Rodelli et al., 1984; Kon et al., 2009), suggesting that they selectively feed on δ13C-enriched sources and were much less dependent on mangrove source than sesarmid crabs. A study conducted in estuarine mangrove forest showed that mangrove source represented < 25% of the primary food source of Uca sp. (Le et al., 2017), and a negligible contribution of mangrove was detected in the diet of U. maracoani crabs in Curuçá Estuary in Brazil (Giarrizzo et al., 2011). However, mangrove-derived carbon com-prised 24.0% – 52.9% (with a mean of 39.2%) of the food source of T. coarctata in the Kema mangrove forest, close to the contribution of SPOM. Because fiddle crabs are generally deposit feeders (Hsieh et al., 2002; Meziane and Tsuchiya, 2002) and mangrove source could be utilized during their scraping sediment materials rich in mangrove source. Kon et al. (2009) also found that Uca crabs de-pended on mangrove detritus for food in a mangrove fo-rest where the isotopic compositions of the sediment organic carbon were very close to the mangrove leaf values.

4.4 Seasonal Variation in the Food Sources of EpifaunaThe faunal community shows seasonal changes in com-position and distribution (Al-Maslamani et al., 2013; Zou et al., 2018), and the feeding behaviors of epifauna might vary with their life stages (Tue et al., 2012). It has been found that the δ13C of epifauna was significantly and ne-gatively correlated with their body sizes and that their diet could present an ontogenetic increase in the contribution of mangrove detritus (Tue et al., 2012). In this study, we did not address the seasonal variation in the food sources of epifauna and the samples of each faunal species were combined together for analysis without considering their body sizes. We considered that this would not prevent us from detecting the role of mangrove-derived carbon as a major food source of epifauna in this study. The benthic en-vironment in the Kema mangrove forest did not signifi-cantly vary across seasons (Sprintall et al., 2003). Bouillon et al. (2004) has suggested that the lack of considera-tion of seasonal variation would not limit the assessment of the general patterns of food sources of benthic fauna in mangrove forests. Nevertheless, we are proposing more de-tailed studies to compare the food sources of benthic fauna in mangrove forests with different allochthonous carbon loadings, and their seasonal variation in composition and size (i.e., life stage) conditions will be considered.

5 ConclusionsThe present study investigated the primary food sources of epifauna in a tropical oceanic mangrove forest. The results showed that the benthic sediment mainly consisted of mangrove detritus, and a majority of the collected epi-fauna species were more dependent on mangrove source than on other allochthonous sources, such as seagrass and phytoplankton. The results suggested that mangrove-de-rived carbon contribute significantly to the food sources of the epifauna inhabiting tropical oceanic mangrove fo-rest where the allochthonous input of organic carbon is low.

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported by the National Key Tech-nologies Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFC0506101), the China-ASEAN Maritime Fund 'Monitoring and Conservation of the Coastal Ecosystems in the South China Sea', and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31101876). The authors are grateful to Mr. Asep Rasyidin, Mr. Mochtar Djabar and Dr. Xijie Yin for their assistance with field sampling and laboratory analysis.

Abrantes, K. G., Johnston, R., Connolly, R. M. and Sheaves, M., 2015. Importance of mangrove carbon for aquatic food webs in wet-dry tropical estuaries. Estuaries and Coasts, 38(1): 383-399. DOI:10.1007/s12237-014-9817-2 (  0) 0) |

Alfaro, A. C., 2008. Diet of Littoraria scabra, while vertically migrating on mangrove trees: Gut content, fatty acid, and stable isotope analyses. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 79(4): 718-726. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2008.06.016 (  0) 0) |

Al-Maslamani, I., Walton, M. E. M., Kennedy, H. A., Al-Mo-hannadi, M. and Le Vay, L., 2013. Are mangroves in arid environments isolated systems? Life-history and evidence of dietary contribution from inwelling in a mangrove-resident shrimp species. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 124: 56-63. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2013.03.007 (  0) 0) |

Alongi, D. M., 2009. The Energetics of Mangrove Forests. Springer Verlag, Dordrecht, 216pp.

(  0) 0) |

Bouillon, S., Koedam, N., Raman, A. V. and Dehairs, F., 2002. Pri-mary producers sustaining macro-invertebrate communities in intertidal mangrove forests. Oecologia, 130(3): 441-448. DOI:10.1007/s004420100814 (  0) 0) |

Bouillon, S., Moens, T., Overmeer, I., Koedam, N. and Dehairs, F., 2004. Resource utilization patterns of epifauna from man-grove forests with contrasting inputs of local versus imported organic matter. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 278: 77-88. DOI:10.3354/meps278077 (  0) 0) |

Chen, G., Azkab, M. H., Chmura, G., Chen, S., Sastrosuwondo, P., Ma, Z., Dharmawan, I. W. E., Yin, X. and Chen, B., 2017. Mangroves as a major source of soil carbon storage in ad-jacent seagrass meadows. Scientific Reports, 7(1): 42406. DOI:10.1038/srep42406 (  0) 0) |

Chen, G., Chen, B., Yu, D., Tam, N. F. Y., Ye, Y. and Chen, S., 2016. Soil greenhouse gas emissions reduce the contribution of mangrove plants to the atmospheric cooling effect. Environ-mental Research Letters, 11(12): 124019. DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/11/12/124019 (  0) 0) |

Chen, G., Yu, D., Ye, Y. and Chen, B., 2013. Impacts of man-grove vegetation on macro-benthic faunal communities. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 33(2): 327-366 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.5846/stxb201111091699 (  0) 0) |

Chen, S., Chen, B., Sastrosuwondo, P., Dharmawan, I. W. E., Ou, D., Yin, X., Yu, W. and Chen, G., 2018. Ecosystem car-bon stock of a tropical mangrove forest in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 37(12): 85-91. DOI:10.1007/s13131-018-1290-5 (  0) 0) |

Chen, S., Chen, G., Chen, B., Ye, Y. and Ma, Z., 2014. Feeding ecology of sesarmid crabs in mangroves. Acta Ecologica Sini-ca, 34(19): 5349-5359 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.5846/stxb201301160110 (  0) 0) |

Chong, V. C., Low, C. B. and Ichikawa, T., 2001. Contribution of mangrove detritus to juvenile prawn nutrition: A dual stable isotope study in a Malaysian mangrove forest. Marine Bio-logy, 138(1): 77-86. DOI:10.1007/s002270000434 (  0) 0) |

Connolly, R. M., Gorman, D. and Guest, M. A., 2005. Move-ment of carbon among estuarine habitats and its assimilation by invertebrates. Oecologia, 144(4): 684-691. DOI:10.1007/s00442-005-0167-4 (  0) 0) |

Gao, X., Wang, M., Wu, H., Wang, W. and Tu, Z., 2018. Effects of Spartina alterniflora invasion on the diet of mangrove crabs (Parasesarma plicata) in the Zhangjiang Estuary, China. Jour-nal of Coastal Research, 34(1): 106-113. DOI:10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-17-00002.1 (  0) 0) |

Giarrizzo, T., Schwamborn, R. and SaintPaul, U., 2011. Utiliza-tion of carbon sources in a northern Brazilian mangrove eco-system. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 95(4): 447-457. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2011.10.018 (  0) 0) |

Giri, C., Ochieng, E., Tieszen, L. L., Zhu, Z., Singh, A., Love-land, T., Masek, J. and Duke, N., 2011. Status and distribu-tion of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 20(1): 154-159. DOI:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00584.x (  0) 0) |

Hsieh, H. L., Chen, C. P., Chen, Y. G. and Yang, H. H., 2002. Diversity of benthic organic matter flows through polychaetes and crabs in a mangrove estuary: δ13C and δ34S signals. Ma-rine Ecology Progress Series, 227: 145-155. DOI:10.3354/meps227145 (  0) 0) |

Jennerjahn, T. C. and Ittekkot, V., 2002. Relevance of mangroves for the production and deposition of organic matter along tro-pical continental margins. Naturwissenschaften, 89(1): 23-30. DOI:10.1007/s00114-001-0283-x (  0) 0) |

Kieckbusch, D. K., Koch, M. S., Serafy, J. E. and Anderson, W. T., 2004. Trophic linkages among primary producers and con-sumers in fringing mangroves of subtropical lagoons. Bulletin of Marine Science, 74(2): 271-285. (  0) 0) |

Kon, K., Kawakubo, N., Aoki, J. I., Tongnunui, P., Hayashizaki, K. I. and Kurokura, H., 2009. Effect of shrimp farming or-ganic waste on food availability for deposit feeder crabs in a mangrove estuary, based on stable isotope analysis. Fisheries Science, 75(3): 715-722. DOI:10.1007/s12562-009-0060-x (  0) 0) |

Kristensen, D. K., Kristensen, E. and Mangion, P., 2010. Food partitioning of leaf-eating mangrove crabs (Sesarminae): Ex-perimental and stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N) evidence. Es-tuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 87(4): 583-590. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2010.02.016 (  0) 0) |

Lai, T. and He, B., 1998. Studies on the macrobenthos species diversity for Guangxi mangrove areas. Guangxi Science, 5(03): 7-13 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.13656/j.cnki.gxkx.1998.03.002 (  0) 0) |

Le, Q. D., Haron, N. A., Tanaka, K., Ishida, A., Sano, Y., Dung, L. V. and Shirai, K., 2017. Quantitative contribution of pri-mary food sources for a mangrove food web in Setiu lagoon from east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, stable isotopic (δ13C and δ15N) approach. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 9: 174-179. DOI:10.1016/j.rsma.2016.12.013 (  0) 0) |

Lee, O. H. K., Williams, G. A. and Hyde, K. D., 2001. The diets of Littoraria ardouiniana and L. melanostoma in Hong Kong mangroves. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 81(6): 967-973. DOI:10.1017/S002531540100491X (  0) 0) |

Lee, S. Y., 1997. Potential trophic importance of the faecal ma-terial of the mangrove sesarmine crab Sesarma messa. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 159: 275-284. DOI:10.3354/meps159275 (  0) 0) |

Lin, J., Huang, Y., Arbi, U. Y., Lin, H., Azkab, M. H., Wang, J., He, X., Mou, J., Liu, K. and Zhang, S., 2018. An ecological survey of the abundance and diversity of benthic macrofauna in Indonesian multispecific seagrass beds. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 37(6): 82-89. DOI:10.1007/s13131-018-1181-9 (  0) 0) |

Macintosh, D., 1980. Ecology and productivity of Malaysian man-grove crab populations (Decapoda: Brachyura). The Asian Sym-posium on Mangrove Environment. Kuala Lumpur: 354-377. (  0) 0) |

Mccutchan, J. H., Lewis, W. M., Kendall, C. and Mcgrath, C. C., 2003. Variation in trophic shift for stable isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. Oikos, 102(2): 378-390. DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12098.x (  0) 0) |

Meziane, T. and Tsuchiya, M., 2002. Organic matter in a sub-tropical mangrove-estuary subjected to wastewater discharge: Origin and utilisation by two macrozoobenthic species. Jour-nal of Sea Research, 47(1): 1-11. DOI:10.1016/S1385-1101(01)00092-2 (  0) 0) |

Murdiyarso, D., Purbopuspito, J., Kauffman, J. B. and Mcgrath, C. C., 2015. The potential of Indonesian mangrove forests for global climate change mitigation. Nature Climate Change, 5(12): 1089-1092. DOI:10.1038/nclimate2734 (  0) 0) |

Newell, R. I. E., Marshall, N., Sasekumar, A. and Chong, V. C., 1995. Relative importance of benthic microalgae, phytoplank-ton, and mangroves as sources of nutrition for penaeid prawns and other coastal invertebrates from Malaysia. Marine Bio-logy, 123(3): 595-606. DOI:10.1007/BF00349238 (  0) 0) |

Park, H. J., Park, T. H., Kang, C. K. and Kang, H. Y., 2017. Comparative trophic structures of macrobenthic food web in two macrotidal wetlands with and without a dike on the tem-perate coast of Korea as revealed by stable isotopes. Marine Environmental Research, 131: 134-145. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2017.09.018 (  0) 0) |

Poon, D. Y. N., Chan, B. K. K. and Williams, G. A., 2010. Spa-tial and temporal variation in diets of the crabs Metopograp-sus frontalis (Grapsidae) and Perisesarma bidens (Sesarmidae): Implications for mangrove food webs. Hydrobiologia, 638(1): 29-40. DOI:10.1007/s10750-009-0005-5 (  0) 0) |

Quan, W., Ying, M., Zhou, Q. and Xu, C., 2018. Carbon source analysis of bivalve-culture based on stable carbon isotope technique. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University, 27(2): 175-180 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Ranjan, R. K., Routh, J., Ramanathan, A. L. and Klump, J. V., 2011. Elemental and stable isotope records of organic matter input and its fate in the Pichavaram mangrove-estuarine se-diments (Tamil Nadu, India). Marine Chemistry, 126(1): 163-172. (  0) 0) |

Rodelli, M. R., Gearing, J. N., Gearing, P. J., Marshall, N. and Sasekumar, A., 1984. Stable isotope ratio as a tracer of man-grove carbon in Malaysian ecosystems. Oecologia, 61(3): 326-333. DOI:10.1007/BF00379629 (  0) 0) |

Sprintall, J., Potemra, J. T., Hautala, S. L., Bray, N. A. and Pandoe, W. W., 2003. Temperature and salinity variability in the exit passages of the Indonesian Throughflow. Deep-Sea Re-search Part Ⅱ, 50(12): 2183-2204. DOI:10.1016/S0967-0645(03)00052-3 (  0) 0) |

Thimdee, W., Deein, G., Sangrungruang, C. and Matsunaga, K., 2004. Analysis of primary food sources and trophic rela-tionships of aquatic animals in a mangrove-fringed estuary, Khung Krabaen Bay (Thailand) using dual stable isotope tech-niques. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 12(2): 135-144. DOI:10.1023/b:wetl.0000021674.76171.69 (  0) 0) |

Thongtham, N. and Kristensen, E., 2005. Carbon and nitrogen balance of leaf-eating sesarmid crabs (Neoepisesarma versi-color) offered different food sources. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 65(1): 213-222. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2005.05.014 (  0) 0) |

Tue, N. T., Hamaoka, H., Sogabe, A., Quy, T. D., Nhuan, M. T. and Omori, K., 2012. Food sources of macro-invertebrates in an important mangrove ecosystem of Vietnam determined by dual stable isotope signatures. Journal of Sea Research, 72: 14-21. DOI:10.1016/j.seares.2012.05.006 (  0) 0) |

Vannini, M., Cannicci, S. and Fratini, S., 2001. Prey selection of Epixanthus dentatus (Crustacea: Brachyura: Eriphiidae) as determined by its prey remains. Journal of the Marine Bio-logical Association of the United Kingdom, 81(3): 455-459. DOI:10.1017/S0025315401004088 (  0) 0) |

Xue, B., Yan, C., Lu, H. and Bai, Y., 2009. Mangrove-derived organic carbon in sediment from Zhangjiang Estuary (China) mangrove wetland. Journal of Coastal Research, 25(4): 949-956. DOI:10.2112/08-1047.1 (  0) 0) |

Yang, M., Gao, T., Xing, Y., Yu, Z., Ying, N. and Wen, A., 2017. Study on the food sources of mangrove macrobenthos in Lian-zhou Bay. Guangxi Sciences, 24(5): 490-497 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.13656/j.cnki.gxkx.20170920.001 (  0) 0) |

Yu, J., Chen, P. M. and Feng, X., 2016. Food habits and trophic levels for 4 species of economical shrimps in the Pearl River Estuary shallow waters. Journal of Southern Agriculture, 47(5): 736-741 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zou, L., Yao, X., Yamaguchi, H., Guo, X., Gao, H., Wang, K. and Sun, M., 2018. Seasonal and spatial variations of macro benthos in the intertidal mudflat of southern Yellow River Del-ta, China in 2007/2008. Journal of Ocean University of China, 17(2): 437-444. DOI:10.1007/s11802-018-3313-4 (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19