2) College of Fisheries, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, China;

3) Guangxi Beibu Gulf Marine Research Center, Guangxi Academy of Sciences, Nanning 530007, China

Horseshoe crabs are an ancient group of invertebrates that have survived for more than 450 million years (Rudkin and Young, 2009). There are three extant Asian species, namely mangrove horseshoe crab, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda; tri-spine horseshoe crab, Tachypleus tridentatus; and coastal horseshoe crab, T. gigas, which can be found along the west coast of the Pacific Ocean. They are ecologically significant in coastal and estuarine food webs as prey and predators, providing proteinand lipid-rich eggs to shorebird populations, and reflecting the general health of coastal ecosystems (Botton, 2009; Kwan et al., 2018, 2021). Despite the IUCN Red List status of C. rotundicauda was currently 'data deficient', the status is under reassessment in view of recent reports describing the apparent population declines in some Asian regions (Wang et al., 2020). The extensive loss of mangrove habitats and the widespread event of fishing bycatches in Asia may have affected the existence of C. rotundicauda populations (John et al., 2018; Supadminingsih et al., 2019). Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda is legally protected in China, Bangladesh, Indonesia and India, despite the limited baseline data of their population status and habitat requirements (Wang et al., 2020).

The reproduction ecology of Atlantic horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus has been studied extensively (Smith et al., 2017). The spawning pairs in amplexus migrate to sandy estuarine beaches, lay thousands of eggs in the mid to upper-intertidal zones, and deposit them at 15 cm or deeper beneath the sediment (Weber and Carter, 2009; Botton et al., 2010) to minimize the adverse impacts from wave action, extreme temperature and osmotic fluctuation (Rudloe, 1979; Botton et al., 1994; Penn and Brockmann, 1994). Fertilized eggs undergo embryonic development within the sediment, followed by the hatching of trilobite larvae (first instars) after 2-4 weeks.

The processes and mechanisms of larval hatching of horseshoe crabs, which occurs beneath the sand remain largely unknown. For L. polyphemus, the larval abundance peaks at high spring tides (Botton and Loveland, 2003; Ehlinger et al., 2003). Although hatching can occur without external stimuli (Jegla, 1979; Ehlinger and Tankersley, 2003), it appears that environmental cues relevant to tidal inundation, such as hydration, osmotic shock and mechanical agitation, can stimulate or facilitate eclosion, which help the dispersal of larvae away from the nesting locations (Ehlinger and Tankersley, 2003; Botton et al., 2010). A previous laboratory study observed the 2-5 times higher hatching levels of L. polyphemus stage-21 embryos when exposed to 24-h submergence at high tide compared to controls incubated using moist paper towels (Ehlinger and Tankersley, 2003).

The developmental ecology study of Asian horseshoe crabs is limited compared to their Atlantic counterpart, Limulus polyphemus. The existing data for Asian species are largely descriptive and assumed to be the same as those of L. polyphemus. Horseshoe crab egg clusters are usually found on estuarine beaches with well-oxygenated sand to maximize egg survival (Nelson et al., 2015; Mohamad et al., 2019), while the spawning adults of C. rotundicauda are frequently sighted in the vicinity of muddy mangrove swamps even during low tides (Cartwright-Taylor, 2015; Fairuz-Fozi et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2019). Therefore, C. rotundicauda larval hatching and dispersal mechanisms might be different.

The aim of this study was to examine the hatching response of C. rotundicauda embryos within the 'nests' under continuous simulated tidal cycles. We did not attempt to investigate the effects of environmental parameters (cues) and their interactions in a complete factorial design. Our primary focus was to understand embryonic responses to varying tidal conditions, along with the changes in environmental parameters, to replicate the tidal processes at the spawning habitats. These findings can enhance our understanding of the developmental ecology of Asian horseshoe crabs, which will be helpful for the management and conservation of Asian horseshoe crabs.

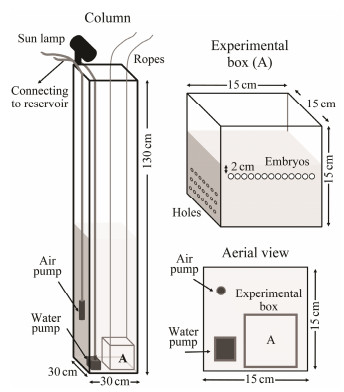

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Experimental SetupFive replicates of experimental setups were prepared. Each experimental setup consisted of a tall acrylic tank (hereafter 'column'; 130 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm), a rectangular acrylic box (hereafter 'experimental box', 15 cm × 15 cm × 15 cm) and a reservoir for water storage (Fig. 1). Each experimental box contained a 9-cm sediment layer obtained from the spawning habitats of C. rotundicauda in the northern Beibu Gulf. There were small holes on three lateral sides of the box, except for the side where embryos were placed (Fig. 1). The box was located at the bottom of the column throughout the experiment. An air pump and a water pump were placed within the column. The water pump was connected to the reservoir to simulate the tidal cycles. A sun lamp was positioned on the top of the column to replicate the natural daylight (Fig. 1).

|

Fig. 1 The experimental setups maintained under simulated tidal conditions. |

The northern Beibu Gulf has a diurnal tidal cycle which typically experiences one high and one low tide every lunar day. Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda eggs were mostly found within the high tide zones with elevated, mildly sloping substratum (Fairuz-Fozi et al., 2018; Zauki et al., 2019). During high tides, preliminary studies demonstrated that the average water level inundating the high-density spawning area along the northern Beibu Gulf shore was approximately 120 cm. In the present experiment, filtered artificial seawater was pumped gradually from the reservoir into the column until reaching the maximum level at 120 cm after 30 min at simulated high tides. Similarly, during simulated falling tides, the seawater was completely withdrawn from the columns within the same duration of time. Simulated rising and falling tides were manipulated once every day in the morning (08:00) and late evening (20:00), respectively. The light: dark cycle of the system was set to 12 h: 12 h.

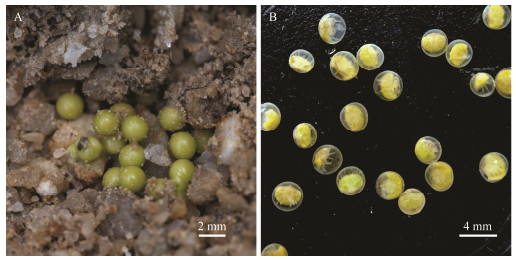

2.2 Experimental AnimalsCarcinoscorpius rotundicauda eggs were collected from Jiaodong and Yuzhouping beaches in the northern Beibu Gulf, China during summer 2020. Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda eggs were distinguished from T. tridentatus by their discernably smaller size (diameter 1.9-2.2 mm versus 3.0-3.3 mm for T. tridentatus) with greenish-yellow color (Fig. 2a). The eggs were cultured in the laboratory until reaching the late-stage (stage 20) embryos (Fig. 2b). A stage- 20 embryo was characterized by the following criteria: 1) opaque chorion has split, 2) there is an active rotation within the clear inner egg membrane, 3) prosomatic appendages are fully segmented, and 4) its size is about double of the fertilized egg diameter.

|

Fig. 2 (A) Developing eggs and (B) stage-20 embryos of C. rotundicauda. C. rotundicauda eggs are distinguished from T. tridentatus by their discernably smaller size with greenish-yellow color, while the stage-20 embryos have apparently larger size with active rotation activity in the clear inner egg membrane. |

Thirty developing embryos were randomly selected and placed in each experimental box at the depth of 1.5 cm within the sediment following the actual depth of C. rotundicauda nests in the natural field (1.5-5.0 cm; FairuzFozi et al., 2018). The use of developing embryos in this study was to eliminate the potential data interference caused by the unfertilized or dead undeveloped eggs, which were difficult to be visually distinguished even under microscopic inspection (Vasquez et al., 2015). The embryos were arranged linearly in front of a lateral side of the experimental box (Fig. 1), so that the hatching process could be clearly observed. The number of experimental embryos was similar to the actual range of the average eggs per nest (20-72) in their spawning habitats (Khan, 2003). The developing larvae were incubated under the following environmental conditions during high tides similar to their spawning habitats along the Beibu Gulf shores: water temperature 30℃, salinity 20, dissolved oxygen DO 6 mg L-1 and pH 7.7. To depict the variations of environmental parameters during the simulated rising and falling tides, temperature, DO and volumetric water content were measured in the environment near the embryos. Water temperature and DO were determined using a handheld YSI DO meter (ProODO, OH, USA), whereas volumetric water content was obtained with a portable soil analyzer (PRSENS, Shandong, China). The measurements were repeated three times and the average value was considered as the final value.

2.3 Video-Based MeasurementsThe experiment lasted for eight weeks, which encompassed the entire incubation period for most embryos to complete the development and survive to be the trilobite larvae (2-4 weeks; Botton et al., 2010). The numbers of 1) embryos with active rotation within the clear inner egg membrane (hereafter 'rotating embryos'), 2) hatched trilobite larvae that remained within the 'nests' (hereafter 'hatched larvae'), and 3) emerged larvae from the sediment surface (hereafter 'emerged larvae'), were recorded during simulated rising/falling tides through videos. Since the experimental embryos/larvae could not be tagged individually, the counting was based on the number of observations. The cumulative survival rate was calculated by deducting the count of embryos with apparent signs of decay that remained within the sediment at the end of the experiment. The entire video recordings lasted for 50 min for each simulated rising and falling tidal process, respectively (10 min prior to the simulated rising/falling tides, 30 min for tidal processes with gradual changes in water levels, and 10 min after reaching the maximum/minimum water levels). The total counts of embryonic/larval activities during the simulated rising/falling tides were categorized as follows: water levels 0 cm, 1-40 cm, 41-80 cm, 81-119 cm and 120 cm, and vice versa.

2.4 Statistical AnalysisAll data were examined for normality and homogeneity of variance prior to the analysis. Regardless of any possible arithmetic transformations, the abundance data did not meet the normality requirements. Thus, non-parametric Scheirer-Ray-Hare extension of Kruskal-Wallis tests was employed to determine the differences among experimental weeks and water levels during the simulated rising and falling tides, respectively. Once a significant difference was found, Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to examine the differences among experimental weeks or water levels, followed by multiple comparisons between experimental groups with Bonferroni's correction. The above statistical analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM, NY, USA), and Scheirer-Ray-Hare extension of the Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted following the modified SPSS protocol of Shen et al. (2013).

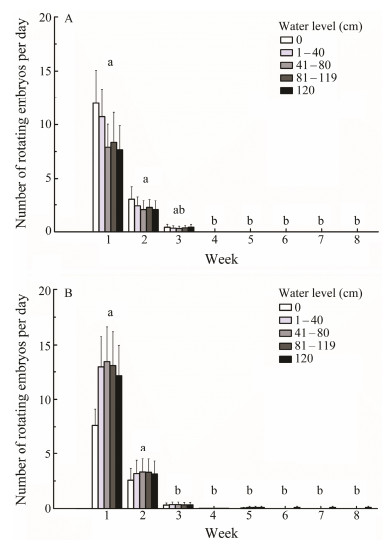

3 Results 3.1 Embryonic Rotation ActivitiesCumulative survival rates for C. rotundicauda embryos at the end of the eight-week experiment ranged from 40% to 95%. The number of 'rotating embryos' (i.e., embryos with the active rotation within clear inner egg membrane) was significantly different among the experimental weeks, but not across water levels during both simulated rising and falling tides (Table 1, Fig. 3). The count of rotating embryos was significantly higher during the first two weeks of the experiment, regardless of the simulated tidal conditions (Fig. 3). It is also important to note a 60%-77% increase in the number of rotating embryos at 1-120 cm water levels compared to that at 0 cm, however, the difference was insignificant (Fig. 3A).

|

|

Table 1 Statistical analysis results of observation counts of embryonic/larval activities among experimental weeks, water levels and their interactions during simulated rising and falling tides using Scheirer-Ray-Hare extension of Kruskal-Wallis test |

|

Fig. 3 Number of embryos (mean ± standard error) with active rotation within the clear inner egg membrane ('rotating embryos') among varying experimental weeks and water levels during the simulated (A) rising and (B) falling tides (n = 5). The data were analyzed by the post-hoc Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by multiple Mann-Whitney U tests with the statistical difference among weeks (P < 0.05) represented by different lowercase letters. |

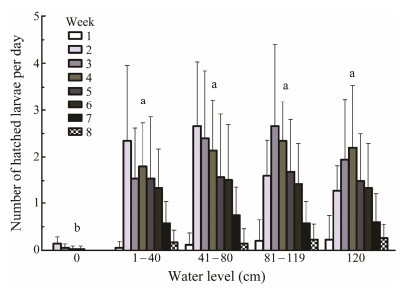

The percentage of embryos hatched and developed into the trilobite stage varied from 3.8% to 29.5% per week. The results demonstrated that the water level, but not the experimental time, during the stimulated rising tides has a significant effect on the larvae hatching (Table 1, Fig. 4). A significantly higher number of hatched larvae was observed when the water level was between 1 cm and 120 cm than those with no water level change (i.e., water level 0 cm, Fig. 4). However, the count of hatched larvae that was retained within the sediment during the simulated falling tides was statistically similar at varying water levels across the experimental weeks (Table 1).

|

Fig. 4 Number of hatched larvae (mean ± standard error) retained in the sediment under varying water levels during the simulated rising tides (n = 5). The data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by multiple Mann-Whitney U tests with the statistical difference among weeks (P < 0.05) represented by different lowercase letters. |

The cumulative emergence rates of trilobite larvae from the sediment ranged 0-47%. The number of emerged larvae was statistically indistinguishable at different water levels and among the experimental time (Table 1). The duration between larval hatching and emergence was approximately 2-6 weeks.

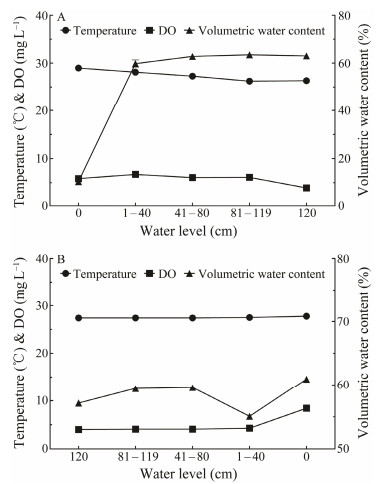

3.3 Changes in Environmental Conditions During Simulated Tidal CyclesWater temperature within the sediment remained relatively stable between 26℃ and 29℃ during the simulated rising tides (Fig. 5). Dissolved oxygen level declined gradually from around 6 mg L-1 to 4 mg L-1 when the water level reached 120 cm. Volumetric water content increased dramatically from 11% before the water rising to 60% after the water level achieved 40 cm, and maintained at approximately 63% throughout the water rising process.

|

Fig. 5 Primary environmental parameters, including water temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO) and volumetric water content within sediments at different water levels during the simulated (A) rising and (B) falling tides. |

During the simulated falling tides, water temperature in the environment near the embryos within the sediment was 27-28℃. Dissolved oxygen concentration experienced a nearly double increase from 4.0-4.3 mg L-1 during the water falling process to 8.4 mg L-1 when the water was completely drained from the experimental setups (Fig. 5). Volumetric water content rose steadily from 57% to 61%, except for a drop at the water level of 1-40 cm.

4 DiscussionLarval hatching is a sophisticated process involving physiological and ecological transitions throughout the developmental stages within the life cycle (Warkentin, 2011). The hatching process occurs only after the completion of morphological and physiological functional trait development, which allows their survival, growth and reproduction in an open environment (Warkentin, 2011). Previous studies demonstrated that the larval hatching in marine organisms can be triggered by chemical/biochemical substances (Tankersley et al., 2002; Ziegler and Forward, 2007), physical disturbances (Griem and Martin, 2000; Martin et al., 2011), and sudden changes in physiochemical conditions such as hydration and hypoxia (Ehlinger and Tankersley, 2003; Polymeropoulos et al., 2016). These cues can help larval hatching and emergence during suitable environmental conditions that often maximize survival and growth rates (Botton et al., 2010; Vasquez et al., 2015).

The hatching process of the embryos of C. rotundicauda and other Asian horseshoe crabs is virtually unknown. For their Atlantic counterpart L. polyphemus, major releases of larvae were coincided with high spring tides, particularly when localized storms with strong onshore winds occurred, and the water reached the level of the nests (Rudloe, 1979). Similarly, previous laboratory studies demonstrated that hatching of L. polyphemus embryos was stimulated by the environmental cues relevant to high water conditions such as hydration, hypoosmotic shock and agitation (Ehlinger and Tankersley, 2003; Botton et al., 2010). However, it is unknown whether and how the tidal cycles of submersed and dry/moisture conditions, and the associated changes in temperature, salinity and other environmental parameters, affect the hatching process. The present results found that the number of C. rotundicauda larvae was significantly higher during the water rising process when the embryos were inundated by tidal water. The embryonic rotation within the transparent inner membrane is a characteristic behavior during the latter stage of development prior to hatching. In this study, there was also a 60%-77% increase in the number of rotating embryos at 1-120 cm water levels compared to that before the water rising (0 cm) in the first week (Fig. 3A). This difference was not significant, probably due to the greater variation of responses among experimental replicates (Fig. 3). The findings were consistent with that of L. polyphemus, reaffirming the important role of hydration in triggering the hatching in horseshoe crab embryos. A possible explanation is that hydration can induce a hypoosmotic shock and cause the embryos to swell and eventually rupture to release the developed larvae (Hayakawa et al., 1985; Ehlinger and Tankersley, 2003). The secretion of osmotically active solutes, such as hexose and uronic acid, into the perivitelline fluid can maintain the slightly hyperosmotic osmolarity of embryos at around 750 mmol kg-1, which corresponded to an approximate salinity of 30 (Sugita, 1988; Ehlinger and Tankersley, 2003).

In addition to hydration and osmotic shock, other environmental triggers such as external agitation induced by wave action and hypoxic condition may also play roles in the hatching of horseshoe crab embryos. Ehlinger and Tankersley (2003) observed that L. polyphemus stage-21 embryos exhibited a higher hatching rate when exposed to simulated agitation using a flat tray shaker at a speed of 60 r min-1 for 30 min with the addition of hydration and sand provision. In the present study, external agitation was likely to be present when the large amount of water entering and outflowing during simulated tidal cycles, even though the magnitude of agitation was not quantified during the experiment. Hypoxia was also frequently cited as one of the important triggers for egg hatching in myriad assortments of fish, amphibians and reptiles (Warkentin, 2002; Doody, 2011; Polymeropoulos et al., 2016). Hypoxic conditions (i.e., O2 < 2 mg L-1) were not observed during the present experiment, despite an apparent reduction in DO level to around 4 mg L-1 at the maximum water level (120 cm) during the simulated rising tides. In the experiment by Ehlinger and Tankersley (2003), hypoxia was not observed to facilitate the hatching of L. polyphemus embryos. Instead of being an environmental trigger, hypoxia might be an unfavorable incubation condition for C. rotundicauda eggs because the clusters are naturally deposited at the shallow depths of 2-5 cm within the sediment, where the anaerobic conditions in muddy mangrove areas can be avoided (Fairuz-Fozi et al., 2018). A laboratory study also pointed out that the three-day exposures at DO 2 and 4 mg L-1 decreased feeding rate, respiration rate and scope for growth of the early instars of T. tridentatus (Shin et al., 2014). The current findings also supported the hypothesis that hatched larvae would remain in nests for several more weeks (circa 2-6 weeks in this study) before being transported from the breeding grounds (Rudloe, 1979; Botton et al., 2010; Srijaya et al., 2014).

Overall, the present results enhance the holistic understanding of hatching process of C. rotundicauda embryos under continuous tidal cycles. The transport of emerged larvae was not explored in this study, but warrants further investigation. Trilobite larvae are weak swimmers; however, high densities of juvenile Asian horseshoe crab populations are found several kilometers away from the nearby nesting sites (Seino et al., 2000; authors' personal observations), and crowded along the outer edges of mangrove forests (Xie et al., 2020). We postulate that the newly hatched larvae are passively transported by tidal creeks among mangrove patches. The settlement process may also be aided by chemical cues from submerged coastal vegetations (Butler and Tankersley, 2020). It is also suggested that the larvae are able to swim vertically to take advantage of selective tidal stream transport in the appropriate direction (Botton et al., 2010).

5 ConclusionsThis study provides novel insight into larval hatching response of C. rotundicauda to environmental conditions during continuous tidal cycles. The number of embryos with active rotation activity was significantly higher during the first two weeks of the experiment, regardless of the tidal conditions. On the other hand, water level during the rising tides was found to influence the hatching, in which a statistically higher count of hatched larvae occurred after the beginning of rising tides. Larval emergence rates did not vary among different experimental time and water levels. The findings are consistent with the available data from both previous laboratory studies and field observations of L. polyphemus that high water conditions, including hydration, osmotic shock and possibly agitation, can stimulate or facilitate the hatching of horseshoe crabs. The results can deepen the understanding of Asian horseshoe crab developmental ecology and identify their critical habitat requirements, which will facilitate the management strategies.

AcknowledgementsThis study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32060129), Guangxi BaGui Youth Scholars Programme, and Guangxi Recruitment Program of 100 Global Experts. The assistance from Dr. Justin Bopp of Michigan State University, U.S. for proof reading this article is highly appreciated.

Botton, M. L., 2009. The ecological importance of horseshoe crabs in estuarine and coastal communities: A review and speculative summary. In: Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. Tanacredi, J. T., et al., eds., Springer, Massachusetts, Boston, 45-63.

(  0) 0) |

Botton M. L., Loveland R. E.. 2003. Abundance and dispersal potential of horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) larvae in the Delaware estuary. Estuaries, 26: 1472-1479. DOI:10.1007/BF02803655 (  0) 0) |

Botton M. L., Colon C. P., Sclafani M., Loveland R. E., Elbin S., Parkins K.. 2021. The relationships between spawning horseshoe crabs and egg densities: Recommendations for the assessment of populations and habitat suitability. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 31: 1570-1583. DOI:10.1002/aqc.3559 (  0) 0) |

Botton M. L., Loveland R. E., Jacobsen T. R.. 1994. Site selection by migratory shorebirds in Delaware Bay, and its relationship to beach characteristics and abundance of horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus eggs. The Auk, 111: 605-616. (  0) 0) |

Botton M. L., Tankersley R. A., Loveland R. E.. 2010. Developmental ecology of the American horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus. Current Zoology, 56: 550-562. DOI:10.1093/czoolo/56.5.550 (  0) 0) |

Brockmann H. J.. 1990. Mating behavior of horseshoe crabs, Limulus polyphemus. Behaviour, 114: 206-220. DOI:10.1163/156853990X00121 (  0) 0) |

Butler C. B., Tankersley R. A.. 2020. Smells like home: The use of chemically-mediated rheotaxes by Limulus polyphemus larvae. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 525: 151323. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2020.151323 (  0) 0) |

Cartwright-Taylor, L., 2015. Studies of horseshoe crabs around Singapore. In: Changing Global Perspectives on Horseshoe Crab Biology, Conservation and Management. Carmichael, R. H., et al., eds., Springer, Zug, Cham, 193-211.

(  0) 0) |

Doody J. S.. 2011. Environmentally cued hatching in reptiles. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 51(1): 49-61. DOI:10.1093/icb/icr043 (  0) 0) |

Ehlinger G. S., Tankersley R. A.. 2003. Larval hatching in the horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus: Facilitation by environmental cues. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 292(2): 199-212. DOI:10.1016/S0022-0981(03)00180-1 (  0) 0) |

Ehlinger G. S., Tankersley R. A., Bush M. B.. 2003. Spatial and temporal patterns of spawning and larval hatching by the horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus, in a microtidal coastal lagoon. Estuaries, 26: 631-640. DOI:10.1007/BF02711975 (  0) 0) |

Fairuz-Fozi N., Satyanarayana B., Zauki N. A. M., Muslim A. M., Husain M. L., Ibrahim S., et al. 2018. Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda (Latreille, 1802) population status and spawning behaviour at Pendas coast, Peninsular Malaysia. Global Ecology and Conservation, 15: e00422. DOI:10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00422 (  0) 0) |

Griem J. N., Martin K. L. M.. 2000. Wave action: The environmental trigger for hatching in the California grunion Leuresthes tenuis (Teleostei: Atherinopsidae). Marine Biology, 137: 177-181. DOI:10.1007/s002270000329 (  0) 0) |

Hayakawa M., Tanimoto S., Kondoand A., Nakazawa T.. 1985. Changes in osmotic pressure and swelling in horseshoe crab embryos during development: (horseshoe crab embryo/swelling/water influx/perivitelline fluid/osmotic pressure). Development, Growth & Differentiation, 27(1): 51-56. (  0) 0) |

Jegla T. C.. 1979. The Limulus bioassay for ecdysteroids. Biological Bulletin, 156: 103-114. DOI:10.2307/1541006 (  0) 0) |

John B. A., Nelson B. R., Sheikh H. I., Cheung S. G., Wardiatno Y., Dash B. P., et al. 2018. A review on fisheries and conservation status of Asian horseshoe crabs. Biodiversity and Conservation, 27(14): 3573-3598. DOI:10.1007/s10531-018-1633-8 (  0) 0) |

Khan R. A.. 2003. Observations on some aspects of the biology of horseshoe crab, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda (Latreille) on mud flats of Sunderban estuarine region. Records of the Zoological Survey of India, 101: 1-23. (  0) 0) |

Kwan B. K. Y., Un V. K. Y., Cheung S. G., Shin P. K. S.. 2018. Horseshoe crabs as potential sentinel species for coastal health: Juvenile haemolymph quality and relationship to habitat conditions. Marine and Freshwater Research, 69: 894-905. DOI:10.1071/MF17210 (  0) 0) |

Kwan K. Y., Bopp J., Huang S., Chen Q., Wang C. C., Wang X., et al. 2021. Ontogenetic resource use and trophic dynamics of endangered juvenile Tachypleus tridentatus among diversified nursery habitats in the northern Beibu Gulf, China. Integrative Zoology, 16(6): 908-928. DOI:10.1111/1749-4877.12495 (  0) 0) |

Liao Y., Hsieh H. L., Xu S., Zhong Q., Lei J., Liang M., et al. 2019. Wisdom of Crowds reveals decline of Asian horseshoe crabs in Beibu Gulf, China. Oryx, 53(2): 222-229. DOI:10.1017/S003060531700117X (  0) 0) |

Martin K., Bailey K., Moravek C., Carlson K.. 2011. Taking the plunge: California grunion embryos emerge rapidly with environmentally cued hatching. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 51(1): 26-37. DOI:10.1093/icb/icr037 (  0) 0) |

Mohamad F., Mohd Sofa M. F. A., Manca A., Ismail N., Che Cob Z., Ahmad A. B.. 2019. Nests placements and spawning in the endangered horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus (Leach, 1819) (Merostomata: Xiphosurida: Limulidae) in Sabah, Malaysia. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 39: 695-702. DOI:10.1093/jcbiol/ruz070 (  0) 0) |

Nelson B. R., Satyanarayana B., Zhong J. M. H., Shaharom F., Sukumaran M., Chatterji A.. 2015. Episodic human activities and seasonal impacts on the Tachypleus gigas (Müller, 1785) population at Tanjung Selangor in Peninsular Malaysia. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 164: 313-323. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2015.08.003 (  0) 0) |

Penn D., Brockmann H. J.. 1994. Nest-site selection in the horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus. The Biological Bulletin, 187(3): 373-384. DOI:10.2307/1542294 (  0) 0) |

Polymeropoulos E. T., Elliott N. G., Frappell P. B.. 2016. The maternal effect of differences in egg size influence metabolic rate and hypoxia induced hatching in Atlantic salmon eggs: Implications for respiratory gas exchange across the egg capsule. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 73(8): 1173-1181. DOI:10.1139/cjfas-2015-0358 (  0) 0) |

Rudkin, D. M., and Young, G. A., 2009. Horseshoe crabs - An ancient ancestry revealed. In: Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. Tanacredi, J. T., et al., eds., Springer, Massachusetts, Boston, 25-44.

(  0) 0) |

Rudloe A.. 1979. Locomotor and light responses of larvae of the horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus (L.). Biological Bulletin, 157: 494-505. DOI:10.2307/1541033 (  0) 0) |

Seino S., Uda T., Tsuchiya Y., Maeda K., Sannami T.. 2000. Field observation of geomorphological features of the spawning site and dispersion of hatchlings of the horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus - Towards mitigation planning for the rare species. Ecology and Civil Engineering, 3(1): 7-19. DOI:10.3825/ece.3.7 (  0) 0) |

Shen X., Qi H., Liu X., Ren X., Li J.. 2013. Two-way non-parametric ANOVA in SPSS. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics, 30: 913-914 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Shin P. K. S., Chan C. S., Cheung S. G.. 2014. Physiological energetics of the fourth instar of Chinese horseshoe crabs (Tachypleus tridentatus) in response to hypoxic stress and reoxygenation. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 85(2): 522-525. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.10.023 (  0) 0) |

Smith D. R., Brockmann H. J., Beekey M. A., King T. L., Millard M. J., Zaldivar-Rae J.. 2017. Conservation status of the American horseshoe crab, (Limulus polyphemus): A regional assessment. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 27(1): 135-175. DOI:10.1007/s11160-016-9461-y (  0) 0) |

Srijaya T. C., Pradeep P. J., Hassan A., Chatterji A., Shaharom F., Jeffs A.. 2014. Oxygen consumption in trilobite larvae of the mangrove horseshoe crab (Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda; Latreille, 1802): Effect of temperature, salinity, pH, and light-dark cycle. International Aquatic Research, 6(1): 1-15. DOI:10.1007/s40071-014-0058-6 (  0) 0) |

Sugita, H., 1988. Environmental adaptations of embryos. In: Biology of Horseshoe Crabs. Sekiguchi, K., ed., Science House Co., Ltd., Tokyo, 195-224.

(  0) 0) |

Supadminingsih F. N., Wahju R. I., Riyanto M.. 2019. Composition of blue swimming crab Portunus pelagicus and horseshoe crab Limulidae on the gillnet fishery in Mayangan Waters, Subang, West Java. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation, 12(1): 14-24. (  0) 0) |

Tankersley R. A., Bullock T. M., Forward Jr. R. B., Rittschof D.. 2002. Larval release behaviors in the blue crab Callinectes sapidus: Role of chemical cues. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 273(1): 1-14. DOI:10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00135-1 (  0) 0) |

Vasquez M. C., Johnson S. L., Brockmann H. J., Julian D.. 2015. Nest site selection minimizes environmental stressor exposure in the American horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus (L.). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 463: 105-14. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2014.10.028 (  0) 0) |

Wang C. C., Kwan K. Y., Shin P. K. S., Cheung S. G., Itaya S., Iwasaki Y., et al. 2020. Future of Asian horseshoe crab conservation under explicit baseline gaps: A global perspective. Global Ecology and Conservation, 24: e01373. DOI:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01373 (  0) 0) |

Warkentin K. M.. 2002. Hatching timing, oxygen availability, and external gill regression in the tree frog, Agalychnis callidryas. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, 75(2): 155-164. DOI:10.1086/339214 (  0) 0) |

Warkentin K. M.. 2011. Environmentally cued hatching across taxa: Embryos respond to risk and opportunity. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 51: 14-25. DOI:10.1093/icb/icr017 (  0) 0) |

Weber, R. G., and Carter, D. B., 2009. Distribution and development of Limulus egg clusters on intertidal beaches in Delaware Bay. In: Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. Tanacredi, J. T., et al., eds., Springer, New York, USA, 249-266.

(  0) 0) |

Zauki N. A. M., Satyanarayana B., Fairuz-Fozi N., Nelson B. R., Martin M. B., Akbar-John B., et al. 2019. Citizen science frontiers horseshoe crab population regain at their spawning beach in East Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Environmental Management, 232: 1012-1020. (  0) 0) |

Ziegler T. A., Forward R. B.. 2007. Control of larval release in the Caribbean spiny lobster, Panulirus argus: Role of chemical cues. Marine Biology, 152(3): 589-597. DOI:10.1007/s00227-007-0712-2 (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21