2) China Nuclear Power Engineering Co., Ltd., Shenzhen 518172, China;

3) First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao 266061, China;

4) Key Laboratory of Marine Science and Numerical Modeling, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao 266061, China

As low-carbon energy, nuclear power is currently the only clean energy source that can replace fossil fuels on a large scale (Mathew, 2022) and is crucial for ensuring China's national energy security. For safety reasons, all nuclear power plants in operation and under construction in China are located along the coastline. Coastal nuclear power plants typically use seawater as cooling water and discharge waste heat into the sea. This increases the seawater temperature, which affects local marine ecosystems (Yu and Zhang, 2008; Li et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2022). Thus, in the layout and design of nuclear power plants, it is necessary to consider the self-purification capacity of water bodies for the resulting thermal pollution.

The main mode of cooling for heated water bodies is heat dissipation to air through the water surface. Thus, in nuclear power plant engineering, the heat transfer coefficient of the water surface (hereafter Ks) is an important parameter in the design of thermal discharge, which determines the installed capacity of power plants (Lin et al., 2021). This coefficient is typically defined as the change in the heat flux of the water surface when the water surface temperature changes by 1℃, comprehensively reflecting the cooling capacity of the heated water body induced by evaporation, convection, and longwave radiation (Pu, 1994).

In the last few decades, scholars around the world have conducted several studies on the measurement and parameterization of Ks and have developed numerous empirical formulas and algorithms for estimating this coefficient (Ryan et al., 1974; Chen et al., 1989; Adams et al., 1990; Pu, 1994; Chen and Mao, 1995; Mao and Chen, 2007). Commonly used algorithms in thermal discharge design in China include Regulation for Hydraulic and Thermal Model in Cooling Water Projects (SL 160-2012) and Code for Design of Cooling for Industrial Recirculating Water (GB/T 50102-2014). However, because of different additional cooling terms, there are significant differences between the Ks values estimated using the two algorithms, which usually confuses engineering designers when choosing algorithms. Furthermore, both algorithms were developed through measurements at cooling ponds and inland lakes (Chen et al., 1989; Chen and Mao, 1995), and their applicability in offshore engineering requires further verification. The Gunneberg formula (see Zhang and Tong, 1986) is also an extensively used algorithm for calculating Ks in studies on thermal discharge (Zhou et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007; Duan et al., 2012). It is only a function of the water surface temperature and wind speed, making it very convenient to use.

Heat exchange at the sea surface is an important component of air-sea interactions in physical oceanography. Because of difficulties in measurement and calculation, the bulk method is currently a commonly used algorithm for calculating air-sea heat exchange. This method is a parameterized algorithm developed on the basis of the Monin-Obukhov similarity theory (Liu et al., 1979). It can be used to calculate air-sea heat fluxes using conventional ocean and meteorological parameters, such as sea surface temperature (SST), air temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed. Scientists have developed various bulk algorithms, among which the coupled ocean-atmosphere response experience (COARE) (Fairall et al., 1996, 2003; Edson et al., 2013) is one of the most extensively used algorithms in physical oceanography studies and numerical models (Zhang et al., 2023).

In this study, we conducted in situ observations near a coastal nuclear power plant and used the COARE and Gunneberg algorithms to evaluate the applicability of current Ks calculation algorithms in China, including SL 160-2012 and GB/T 50102-2014, in coastal areas. The algorithms are briefly introduced in Section 2. The observation and evaluation results are presented in Section 3, and Section 4 provides the conclusion of this study.

2 Algorithms and Methods 2.1 SL 160-2012The SL 160-2012 algorithm is the current water conservancy industry standard in cooling water projects in China and probably originates from a study on evaporation and scattering in the water surface of heated water bodies by Chen et al. (1989). In this algorithm, Ks is represented as follows:

| $ \begin{gather*} K s=(k+b) \alpha+4 \varepsilon \sigma\left(T_{s}+273\right)^{3}+\Delta K s, \end{gather*} $ | (1) |

| $ \Delta K s=80(1+k m)\left[b\left(T_{s}-T_{a}\right)+\Delta e\right] / \alpha, $ | (2) |

| $ k=\partial e_{s} / \partial T_{s}, $ | (3) |

| $ b=0.66 P / 1000, $ | (4) |

| $ \alpha=\left[22.0+12.5 V_{w}^{2}+2.0\left(T_{s}-T_{a}\right)\right]^{1 / 2}, $ | (5) |

| $ m=0.378\left(T_{s}+273\right) / P, $ | (6) |

| $ \Delta e=e_{s}-e_{a}, $ | (7) |

where α denotes the water surface evaporation coefficient in units of W m−2 hPa−1, ε denotes water surface emissivity (taken as 0.97), σ denotes the Stafan-Boltzman constant (taken as 5.67 × 10−8 W m−2 ℃−4), Ts denotes the water surface temperature in units of ℃, Ta denotes the air temperature 1.5 m above the water surface in units of ℃, es denotes the saturated water vapor pressure corresponding to the water surface temperature in units of hPa, ea denotes the water vapor pressure 1.5 m above the water surface in units of hPa, Vw denotes the wind speed 1.5 m above the water surface in units of m s−1, and P represents the atmospheric pressure 1.5 m above the water surface in units of hPa.

2.2 GB/T 50102-2014The GB/T 50102-2014 algorithm is a national standard of cooling for industrial recirculating water and refers to a study on the universal formula for the evaporation coefficient of heated water bodies by Mao and Chen (2007). With the exception of the additional cooling term ΔKs, this algorithm is consistent with SL 160-2012. It can be written as follows:

| $ \begin{gather*} K s=(k+b) \alpha+4 \varepsilon \sigma\left(T_{s}+273\right)^{3}+\Delta K s, \end{gather*} $ | (8) |

| $ \Delta K s=\left[b\left(T_{s}-T_{a}\right)+\Delta e\right] / \alpha . $ | (9) |

The Gunneberg formula depends only on the water surface temperature and wind speed (see Zhang and Tong, 1986) and can be represented as Eq. (10):

| $ \begin{equation*} K s=2.2 \times 10^{-7} \times\left(T_{s}+273.15\right)^{3}+\left(1.5+1.12 V_{2}\right) \times 10^{-3} \times\left[\left(\left(2501.7-2.366 T_{s}\right) \times 25509 \times 10^{\frac{7.56 T_{s}}{T_{s}+239.7}}\right) /\left(T_{s}+239.7\right)^{2}+1621\right], \end{equation*} $ | (10) |

where V2 denotes the wind speed 2 m above the water surface in units of m s−1.

2.4 COARE AlgorithmIn the ocean, the upward heat flux (QT) from the sea surface primarily includes three processes: latent heat flux (QE), sensible heat flux (QS), and surface longwave radiation (QLW).

| $ \begin{equation*} Q_{T}=Q_{E}+Q_{S}+Q_{L W} . \end{equation*} $ | (11) |

In the COARE algorithm, these values are respectively represented as

| $ {Q_E} = {\rho _a}{L_e}{C_E}U({q_s} - {q_a}), $ | (12) |

| $ Q_{S}=\rho_{a} C_{p} C_{H} U\left(T_{s}-T_{a}\right), $ | (13) |

| $ \begin{equation*} Q_{L W}=\varepsilon \sigma\left(T_{s}+273\right)^{4}, \end{equation*} $ | (14) |

where ρa denotes the air density; CE and CH denote the transfer coefficients for latent heat and sensible heat, respectively; U represents the wind speed; Le denotes the latent heat of evaporation; Cp denotes the specific heat of air at constant pressure; qs and qa denote the saturated specific humidity at the sea surface and the specific humidity of air, respectively; Ts and Ta denote the SST and air temperature, respectively.

Ks can be calculated as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} K s=\left(Q_{T}-Q_{T, \infty}\right) /\left(T_{s}-T_{s, \infty}\right), \end{equation*} $ | (15) |

where ∞ denotes far-field. QT and Ts denote the total upward heat flux and SST of heated water bodies caused by thermal discharge, respectively; QT, ∞ and Ts, ∞ denote the total upward heat flux and SST observed at a distance where the thermal discharge is not affected (Pu, 1994).

After approximately 30 years of development, multiple versions of the COARE algorithm have been proposed. In this study, the new version of COARE 3.6 was adopted. Some specific technical details are provided by Fairall et al. (2003) and Edson et al. (2013).

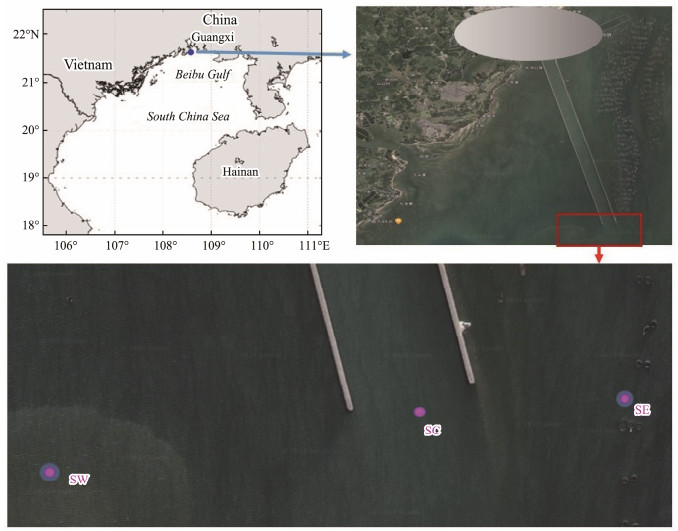

3 Observation and Evaluation 3.1 Field ObservationsField observations were performed in the northwestern South China Sea near a coastal nuclear power plant (Fig.1). In this power plant, thermal wastewater is discharged into the sea through an open channel approximately 6.2 km long. Three observation stations, SC, SE, and SW, were set up near the drainage outlet using fishing boats. SC was located at the outer end of the drainage channel (21˚ 36.5377΄N, 108˚34.6044΄E), SE was located approximately 500 m east of SC, and SW was located approximately 950 m west of SC.

|

Fig. 1 Observation location and station settings. |

Ocean and atmospheric parameters, including the SST, air temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed, were measured at each station. The SST was measured using the RBRduet3 T.D logger, air temperature and humidity were measured using an HMP155a probe, and wind speed was measured using a Young 05108 monitor. The sampling frequencies of these instruments were 1 Hz, and the data were averaged over 30-min time segments. The observations lasted for approximately 3 days, from 18:30 on July 20 to 19:00 on July 23, 2023, and 145 sets of data were then used for the following analysis.

At the three stations, the observation height of wind was approximately 3.3 m above the sea surface. The observation heights of air temperature and relative humidity were 2.3 m at SC and 2.8 m at the other two stations. To the north of SE, an acoustic Doppler current profiler (Nortek Signature 500) with a sampling frequency of 2 Hz was fixed on the sea floor to measure surface waves and tides using the acoustic surface tracking (AST) method. Because of instrument malfunction, the observed atmospheric pressure data were not available. In the following analysis, it was simply set to 1010 hPa.

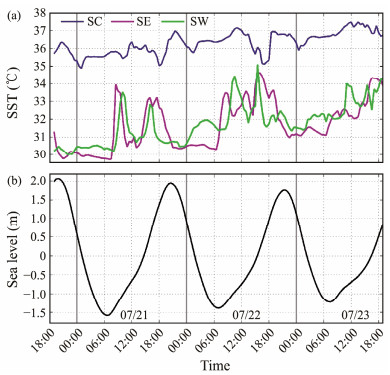

3.2 Observation ResultsFig.2a shows the SSTs measured at the three stations. The SST at SC ranged from 34.9℃ to 37.5℃, which was significantly higher than those at the other two stations. The other two stations are located on the east and west sides of SC, and their SSTs are roughly the same, ranging from 29.7℃ to 35.1℃. The SSTs of these two stations were approximately 0.7℃ – 6.7℃ lower than that of SC, with an average of 4.6℃ (Table 1).

|

Fig. 2 Sea surface temperature (SST) measured at three stations (a) and sea level height measured near SE (b). |

|

|

Table 1 Average oceanic and atmospheric parameters observed and calculated at three stations and the increments Δ caused by thermal discharge |

The tides exhibited obvious diurnal variations during the 3-day observations, with a maximum tidal range of 3.65 m (Fig.2b). The changes in tides have little effect on the SST at SC but have a significant impact on the SSTs at SE and SW. During the ebb tide, both SE and SW were less affected by thermal drainage because of the flow of seawater toward the open sea, and the SST was low. During the flood tide, the two stations were significantly affected by thermal drainage, resulting in higher SSTs and a significantly smaller SST difference than SC.

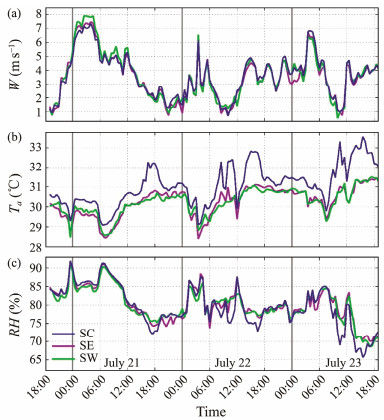

The wind speed, air temperature, and relative humidity measured at the three stations are shown in Fig.3. Overall, the differences in wind speed and relative humidity at the three stations were not significant during the observation period. The wind speed was approximately between 0.5 and 7.9 m s−1, and the relative humidity was between 66% and 92%. However, there were significant differences in the air temperature between SC and the other two stations; the air temperature at SC was higher than those at SE and SW by an average of 0.8℃ (Table 1). This was mainly related to changes in the local environment caused by the heated water body.

|

Fig. 3 Wind speed (W) (a), air temperature (Ta) (b), and relative humidity (RH) (c) measured at three stations. |

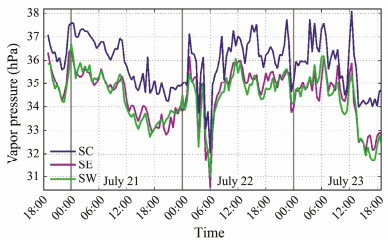

The water vapor pressure is an important parameter in the calculation of Ks, which depends on the air temperature and relative humidity and can be calculated as follows:

| $ \begin{equation*} e_{a}=R H \times 6.112 \mathrm{e}^{\frac{17.67 T_{a}}{T_{a}+243.5}} . \end{equation*} $ | (16) |

Corresponding to an increase in the air temperature, the water pressure at SC increased by approximately 1.4 hPa (Fig.4).

|

Fig. 4 Water vapor pressure calculated using air temperature and relative humidity at three stations. |

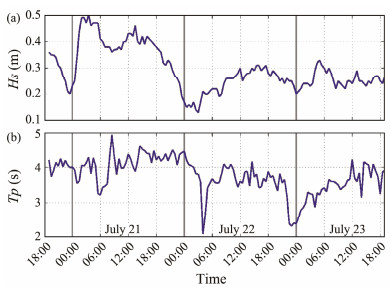

Surface waves have a significant impact on the dynamic and thermal processes in the upper ocean and are typically used to calculate upper ocean turbulent mixing (Tang et al., 2024) and air-sea fluxes (Fairall et al., 2003; Edson et al., 2013). Because the observation area was located in shallow offshore waters, surface waves were weak, with significant wave heights ranging from 0.13 to 0.50 m and peak periods ranging from 2.1 to 4.9 s during the observation period (Fig.5).

|

Fig. 5 Significant wave height (Hs) (a) and peak period (Tp) (b) measured near SE. |

Fig.6 shows the sensible heat flux, latent heat flux, and upward longwave radiation of the sea surface calculated using the COARE 3.6 algorithm at the three stations. The trends of changes in latent and sensible heat fluxes at the three stations were roughly the same; however, the magnitude of the former was significantly greater than that of the latter. The average latent and sensible heat fluxes at SC were 287.2 and 41.2 W m−2, respectively, whereas those at SE and SW were only 119.1 and 9.5 W m−2, and 125.6 and 10.4 W m−2, respectively, during the 3-day observations. The trend of upward longwave radiation was roughly consistent with the SST, with averages of 504.3, 474.8, and 475.3 W m−2 at SC, SE, and SW, respectively.

|

Fig. 6 Sensible heat flux (Qs) (a), latent heat flux (QE) (b), and longwave radiation of the sea surface (QLW) (c) calculated using the COARE 3.6 algorithm at three stations. |

In general, the surface heat flux at SC was significantly higher than that of the other two stations. The average SST at SC was 4.6℃ higher than those at the other two stations; however, the total upward heat flux of SC increased by 225.3 W m−2 during the 3-day observation period; 73% of the contribution came from changes in latent heat flux (Table 1).

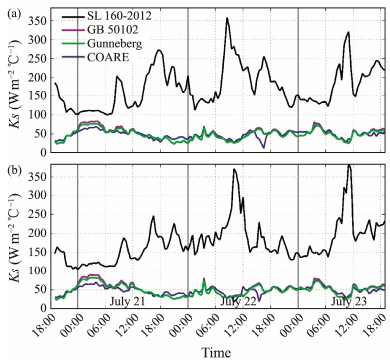

Fig.7 shows the Ks values calculated using various algorithms based on the observation data of the three stations. In these calculations, the observed wind speed was adjusted to the height required by other algorithms based on the empirical formulas in the COARE algorithm. The calculation results of SL 160-2012 were significantly higher than those of the other methods. The mean Ks was 48.5 W m−2 ℃−1 with the COARE algorithm (Table 2), 48.8 W m−2 ℃−1 with the Gunneberg formula, and 50.4 W m−2 ℃−1 with GB/T 50102-2014. However, it was as high as 176.3 W m−2 ℃−1 with SL 160-2012.

|

Fig. 7 Heat transfer coefficient Ks calculated using various algorithms based on data obtained at (a) SE and (b) SW. |

|

|

Table 2 Average heat transfer coefficient Ks calculated using various algorithms (W m−2 ℃−1) |

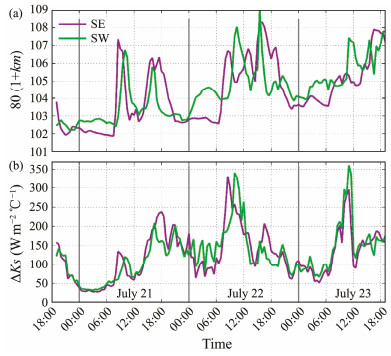

This notably higher value was mainly due to the additional cooling term ΔKs in SL 160-2012. In SL 160-2012, the coefficient of ΔKs is 80(1 + km)/α, whereas it is only 1/α in GB/T 50102-2014. The value of 80(1 + km) was approximately between 102 and 109 (Fig.8a), which is more than 100 times larger than the corresponding item in GB/T 50102-2014. This large value significantly increased the estimation of Ks. During the 3-day observation period, only ΔKs was greater than 127.0 W m−2 ℃−1 in this algorithm (Fig.8b), which was significantly greater than Ks calculated using the other algorithms. Furthermore, even for SL 160-2012, the ratio of ΔKs to Ks was 72%, significantly greater than the expected range of 2% – 20% when this algorithm was developed (Chen et al., 1989).

|

Fig. 8 Coefficient 80(1 + km) (a) and additional cooling term ΔKs (b) in the SL 160-2012 algorithm based on data from SE and SW. |

This abnormally large additional cooling term may be due to incorrect unit conversion. When Chen et al. (1989) developed this algorithm, the unit of water vapor pressure used was kPa, whereas, in SL 160-2012, the unit was hPa. Therefore, the coefficient of ΔKs in SL 160-2012 should be reduced 100 times to 0.8(1 + km)/α, implying that Eq. (2) should be corrected to

| $ \begin{equation*} \Delta K s=0.8(1+k m)\left[b\left(T_{s}-T_{a}\right)+\Delta e\right] / \alpha . \end{equation*} $ | (17) |

If this term is corrected, the value of ΔKs in SL 160-2012 becomes very close to that in GB/T 50102-2014, and the mean Ks calculated using the corrected SL 160-2012 algorithm decreases to 50.5 W m−2 ℃−1, which is also very close to the value in GB/T 50102-2014 (Table 2). Previous studies may have noticed this error and adjusted the coefficient of ΔKs to decrease the estimated Ks (Hou et al., 2019).

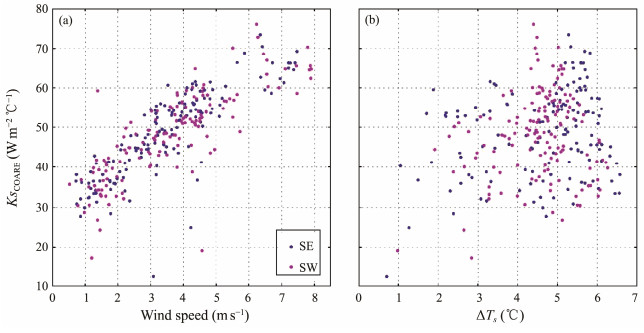

3.4 DiscussionBecause of the distribution of land and sea and changes in water depth, there are typically significant spatial variations in marine and meteorological elements in nearshore waters. To avoid the impact of these variations, the three stations we observed were set close, which resulted in the SSTs at SE and SW being affected by the thermal discharge of the nuclear power plant during the flood tide (Fig.2). However, Ks calculated using COARE3.6 were primarily affected by sea surface winds and were not sensitive to SST differences between stations (Fig.9).

|

Fig. 9 Heat transfer coefficient Ks calculated using the COARE algorithm as a function of sea surface wind speed (a) and SST differences at SC (b). The blue and pink dots represent the SE and SW results, respectively. |

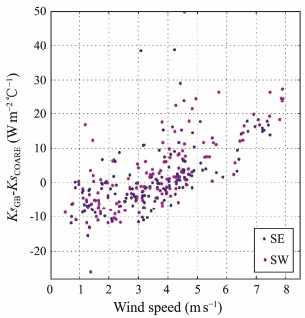

Although Ks calculated using GB/T 50102-2014 was roughly consistent with the calculation results of the COARE algorithm and the Gunneberg formula, there were certain differences between them. The difference increased roughly with an increase in sea surface winds (Fig.10). Therefore, further studies are required to improve the calculation of the heat transfer coefficient, especially the relationship between the coefficient and wind.

|

Fig. 10 Deviation between the heat transfer coefficient Ks calculated using the GB/T 50102-2014 and COARE algorithms as a function of sea surface wind speed. The blue and pink dots represent the SE and SW results, respectively. |

In this study, 3-day on-site observations were performed within the thermal discharge area of a nuclear power plant in the northwestern South China Sea. During this observation period, the average SST increase caused by thermal discharge was 4.6℃, with a maximum value of 6.7℃. The increase in SST had little effect on wind speed but significantly affected air temperature and, thus, water vapor pressure. In these observations, as the SST increased, the average air temperature at the thermal discharge outlet increased by 0.8℃, and the water vapor pressure increased by 1.4 hPa.

These observation data were used to evaluate the performance of several commonly used Ks calculation algorithms. The results indicate that SL 160-2012 is not suitable for calculating Ks in offshore areas because it significantly overestimates the cooling capacity of the water surface. However, GB/T 50102-2014 performed well, and its calculation results were generally consistent with those obtained using the COARE algorithm and the Gunneberg formula. In the 3-day observations, the average Ks values estimated using these three algorithms were 50.4, 48.5, and 48.8 W m−2 ℃−1, respectively, with a difference of less than 4% between them; however, Ks estimated using SL 160-2012 was as high as 176.3 W m−2 ℃−1.

The abnormally large value obtained using SL 160-2012 is due to its incorrect additional cooling term ΔKs, which was falsely increased by 100 times because of unit conversion errors. If this error is corrected, its estimated Ks and ΔKs are very close to those of GB/T 50102-2014. Therefore, the GB/T 50102-2014 algorithm is recommended for thermal drainage engineering in coastal nuclear power plants. Conversely, when developing new industry standards, this error in SL 160-2012 should be corrected to obtain a reasonable Ks value.

There were also certain differences among Ks values calculated using GB/T 50102-2014, the COARE algorithm, and the Gunneberg formula. Therefore, it is necessary to further study the cooling capacity of water surfaces using direct measurements of sea surface heat fluxes in the thermal discharge areas of nuclear power plants to develop new national or industry standards and provide accurate design parameters for the construction of coastal nuclear power plants.

AcknowledgementsThis study is supported by the Laoshan Laboratory (No. LSKJ202201600), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41821004).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Chuanjiang Huang and Jingsong Guo. The draft of the manuscript was written by Qichao Zhu and Chuanjiang Huang, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Adams, E. E., Douglass, J. C., and Karl, R. H., 1990. Evaporation from heated water bodies: Predicting combined forced plus free convection. Water Resources Research, 26(3): 425-435. DOI:10.1029/WR026i003p00425 (  0) 0) |

Chen, H., and Mao, S., 1995. Calculation and verification of a universal water surface evaporation coefficient formula. Advances in Water Science, 6(2): 116-120 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Chen, H., He, S., Liu, C., Zhang, S., Mao, S., and Zhao, D., 1989. Experimental study on mass and heat exchange at air-water interface of heated water body. Shuili Xuebao, 10: 27-36 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Chen, X., Zhu, J., and Han, L., 2007. Defining methods of the heat transfer coefficient and its analysis of sensitiveness. Water Sciences and Engineering Technology, 5: 9-13 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Duan, G., Zhang, Y., and Xue, C., 2012. Numerical simulation of thermal discharge in alluvial river. Yellow River, 34(4): 135-137 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Edson, J. B., Raju, J. V. S., Weller, R. A., Bigorre, S., Plueddemann, A., Fairall, C. W., et al., 2013. On the exchange of momentum over the open ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 43: 1589-1610. (  0) 0) |

Fairall, C. W., Bradley, E. F., Hare, J. E., Grachev, A. A., and Edson, J. B., 2003. Bulk parameterization of air-sea fluxes: Updates and verification for the COARE algorithm. Journal of Climate, 16: 571-591. (  0) 0) |

Fairall, C. W., Bradley, E. F., Rogers, D. P., Edson, J. B., and Young, G. S., 1996. Bulk parameterization of air-sea fluxes for TOGA COARE. Journal of Geophysical Research, 101: 3747-3764. (  0) 0) |

Fu, Q., Zhu, L. X., Shen, A. L., and Li, D. J., 2015. Survey and comparison of seasonal influences of thermal discharge from coastal power plant on zooplankton community. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 45(7): 25-33 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

GB/T 50102-2014, 2014. Code for Design of Cooling for Industrial Recirculating Water. China Planning Press, China Electricity Council, Beijing, 228pp (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Hou, S., Tang, B., Wang, Y., Li, J., and Sun, Q., 2019. Study on several issues related to thermal discharge of coastal NPPs. Marine Environmental Science, 38(6): 927-938 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Li, X. Y., Li, B., and Sun, X. L., 2014. Effects of a coastal power plant thermal discharge on phytoplankton community structure in Zhanjiang Bay, China. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 81(1): 210-217. (  0) 0) |

Lin, J., Zou, X., Huang, F., and Yao, Y., 2021. Quantitative estimation of sea surface temperature increases resulting from the thermal discharge of coastal power plants in China. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 164: 112020. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112020 (  0) 0) |

Liu, Q., Zhou, L., Zhang, W., Zhang, L., Tan, Y., Han, T., et al., 2022. Rising temperature contributed to the outbreak of a macrozooplankton Creseis acicula by enhancing its feeding and assimilation for algal food nearby the coastal Daya Bay nuclear power plant. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 238: 113606. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113606 (  0) 0) |

Liu, W. T., Katsaros, K. B., and Businger, J. A., 1979. Bulk parameterization of air-sea exchanges of heat and water vapor including the molecular constraints at the interface. Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 36(9): 1722-1735. (  0) 0) |

Mao, S., and Chen, H., 2007. Study and application of universal formula for evaporation coefficient of heated water bodies. Advances in Science and Technology of Water Resources, 27(6): 85-89 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Mathew, M. D., 2022. Nuclear energy: A pathway towards mitigation of global warming. Progress in Nuclear Energy, 143: 104080. DOI:10.1016/j.pnucene.2021.104080 (  0) 0) |

Pu, P., 1994. Studies on the formulae for calculating evaporation and heat loss coefficient from water surface in China (Ⅱ). Journal of Lake Sciences, 6(3): 201-210 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Ryan, P. J., Harleman, D. R. F., and Stolzenbach, K. D., 1974. Surface heat loss from cooling ponds. Water Resources Research, 10(5): 930-938. (  0) 0) |

SL 160-2012, 2012. Regulation for Hydraulic and Thermal Model in Cooling Water Projects. China Water Power Press, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing, 33pp (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Tang, R., Huang, C., Dai, D., and Wang, G., 2024. Evaluation of nonbreaking wave-induced mixing parameterization schemes based on a one-dimensional ocean model. Journal of Ocean University of China, 23(3): 567-576. DOI:10.1007/s11802-024-5687-9 (  0) 0) |

Yu, F., and Zhang, Y., 2008. The review on the effects of thermal effluent from nuclear plants on the marine ecosystem. Radiation Protection Bulletin, 28(1): 1-7 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhang, S., and Tong, L., 1986. Experimental study on indoor water surface heat dissipation coefficient. Water Resources Protection, 2(2): 1-9 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhang, W., Zhang, J., Guan, C., and Sun, J., 2023. Impacts of surface exchange coefficients on simulations of Super Typhoon Megi (2010) using a coupled ocean-atmosphere-wave model. Journal of Ocean University of China, 22(3): 587-600. DOI:10.1007/s11802-023-5409-8 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, L., Sun, Y., Zhang, X., and Sun, C., 2006. Alternative projects of warm water drainage for the second-stage construction of Huanghua power plant. Marine Science Bulletin, 35(5): 43-49 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24