2) Laboratory for Marine Drugs and Bioproducts of Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266003, China

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are ligandgated ion channels mediating the fast synaptic transmission of the neurotransmitter in our nervous system (Le Novere et al., 1995; Romanelli et al., 2007; Taly et al., 2009). The nAChRs are widely distributed throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems including several regions of the brain (Deneris et al., 1991). They influence many physiological processes and have a strong relationship with many neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, schizophrenia, anxiety, and depression (Liu et al., 2006). There are a wide variety of nAChR subtypes expressed in the central nervous system. One of the most occurring subtypes is the α7 nAChR (Séguéla et al., 1993; Paterson et al., 2000). The α7 nAChR is assembled by five identical α7 subunits and has high affinity for α-bungarotoxin and methyllycaconitine (MLA), and is highly permeable for Ca2+ ions (Jensen et al., 2005). Hence, the α7 nAChR is an important drug target to treat various neuronal disorders (Liu et al., 2006; Taly et al., 2009; Beinat et al., 2015; Skok et al., 2016; Zanetti et al., 2016; Corradi et al., 2016; Kalkman et al., 2016).

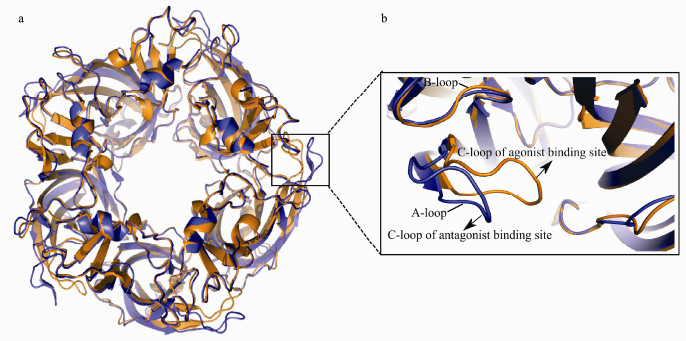

During the past few decades, considerable efforts have been made toward the development of agonists or antagonists of the nAChRs in the brain (Bunnelle et al., 2004; Hansen et al., 2005; Brams et al., 2011; Beinat et al., 2016; Ondachi et al., 2017). There are various ligands targeting the α7 nAChR, and they are classified into agonists, antagonists, allosteric modulators, and indirect regulators based on their modes of action and pharmacological effects. Most of the agonists or antagonists discovered so far target the orthosteric ligand binding site that is between two adjacent subunits of the extracellular domain of the nAChR. The orthosteric binding site is constituted of Loop A, B and C (Fig. 1). Agonists and antagonists present certain degree of selectivity toward the conformational state of the nAChR (Hansen et al., 2005; Hibbs et al., 2009). In general, the competitive antagonists can potently bind with the closed state of the α7 receptor and prevent the conformational changes necessary for the channel opening, while agonists can trigger the conformational changes, leading to the opening of the channel (Fig. 1) (Gao et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2006).

|

Fig. 1 a) Top view of the superimposed crystal structures of the α7 nAChR chimera with open C-loop in blue (PDB ID: 4HQP) and closed C-loop in orange (PDB ID: 3SQ6). b) Magnified showing the binding site of the agonist and antagonist of the nAChR. |

It is important to develop a reliable and efficient computational approach for differentiation of the agonists and antagonists of the nAChR. Our previous study showed that the ligand efficiency could be used for differentiation of the agonists from the antagonists of the nAChR based on a systematical analysis of the ligands bound with the crystal structures of the acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP) (Ma et al., 2017). The present study was undertaken to further study the relationship between ligand efficiency and ligand efficacy, and to evaluate the feasibility of using ligand efficiency to differentiate the agonists from antagonists of the nAChR. The large number of the α7 nAChR ligands were reported (table S1), which gave rise to the possibility to test our assumptions from previous study (Ma et al., 2017).

2 Computational Methods 2.1 MOE Binding Affinity CalculationMolecular docking was performed using MOE with the AMBER10: EHT force field (Kitchen et al., 2004; Vilar et al., 2008). The 123 α7 nAChR ligands (Table S1) were sketched in ChemDraw and minimized in MOE. Docking of these ligands into the orthosteric binding site of the α7 nAChR crystal structures bound with agonist (PDB ID: 3SQ6) (Li et al., 2011) and antagonist (PDB ID: 4HQP) (Huang et al., 2013) was performed using the MOE. The induced fit docking approach was applied with consideration of the side chain flexibility of residues at the binding site. The ligand binding site of 3SQ6 was defined using the bound ligands in the crystal structures, and the ligand binding site of 4HQP was defined using the snake toxins in the crystal structure. Ten docking conformations of the ligands were produced, and the top five scored conformations with minimum binding energy were selected for analysis.

2.2 Ligand SizeThe number of heavy atoms for the nAChR ligands was calculated using ChemDraw.

2.3 Ligand Binding Affinity and Ligand EfficiencyThe ligand binding affinity (ΔG) was calculated using the average of the binding energy corresponding to the top five scored conformations. All the ligands were docked into the binging site with closed or open conformational state. Ligand efficiency (Δg) was determined using the equation:

| $ \Delta g = \Delta G/{N\;_{{\rm{heavy\;atoms }}}}, $ | (1) |

where ΔG is the binding free-energy change (or ligand binding affinity) and N heavy atoms is the number of heavy or non-hydrogen atoms (Andrews et al., 1984; Hopkins et al., 2004; Brams et al., 2011).

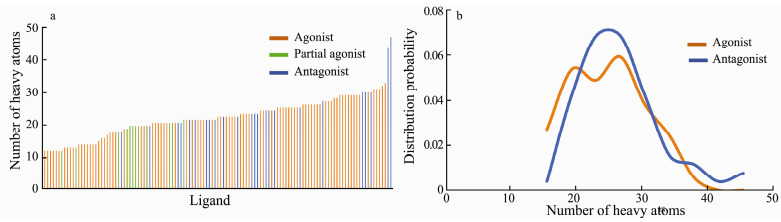

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 Ligand SizeIn the previous study the ligand efficacy was discovered to correlate to their size or the number of heavy atoms that they contained (Ma et al., 2017). In this study 123 α7 nAChR ligands, including 87 agonists, 12 partial agonists and 24 antagonists were collected from the literature, and the number of heavy atoms for these ligands was calculated using ChemDraw. To our surprise, when the α7 nAChR ligands are arranged in ascending order according to the number of heavy atoms, the agonist, partial agonist, and antagonist show a less regular distribution than that discovered in the previous study. As shown in Fig. 2a, the agonists are distributed on each position of the horizontal axis, while the antagonists are mainly located in the middle of the horizontal axis, with only a few of them distributed to the right. When the number of heavy atoms are no more than 17, the ligands are full agonist or partial agonist of the α7 nAChR, which is consistent with results from previous ligand size-ligand efficacy relationship analysis. However, when the number of heavy atoms are more than 17, the distribution of the agonists and antagonists becomes irregular, and their distribution probability is essentially overlapped (Fig. 2b). Notably, the ligand size distribution boundary between agonists and antagonists is not clearly defined. Indeed, for certain amount of nAChR antagonists they have a relatively small size but can still form a unique structure configuration to stabilize the conformation of the C-loop into open conformation. The number of heavy atoms merely is therefore not a reliable component for differentiation of the agonists from the antagonists of the nAChR.

|

Fig. 2 Distribution of the number of heavy atoms for agonists and antagonists of the α7 nAChR. a) Ranking distribution of the α7 nAChR agonist (orange), partial agonist (green) or antagonist (blue) based on the ligand size (number of heavy atoms) in an order form low to high. b) Histogram frequency distribution of agonist (orange) or antagonist (blue) with the relationship of the α7 nAChR ligand size. |

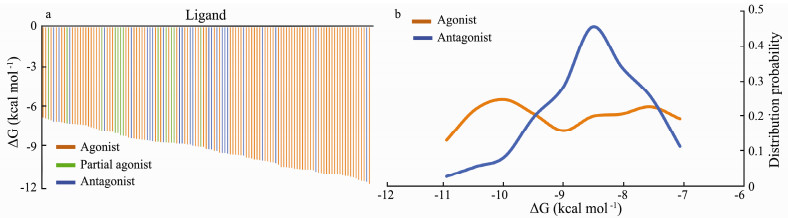

In the previous study, the ligand efficacy was found to have no relationship with ligand binding affinity (Ma et al., 2017). Here, we re-evaluated the relationship between ligand binding affinity and their efficacy by docking of the α7 nAChR ligands to the crystal structures of the α7 nAChR chimera bound with agonist and antagonist. Ranking of the ligands based on their binding affinity resulted in irregular distribution (Figs. 3a, b) and the agonist and antagonist are distributed irregularly along the horizontal axis. In line with the results from our previous studies, the ΔG cannot be used for differentiation of the agonists from the antagonists of the nAChR.

|

Fig. 3 Predicted binding affinity distribution for α7 nAChR agonist and antagonist. a) Ranking distribution of the α7 nAChR agonist (orange), partial agonist (green) or antagonist (blue) based on the ligand binding free energy (ΔG) in an order from the high to the low. b) Histogram frequency distribution of agonist (orange) or antagonist (blue) with the relationship of the α7 nAChR ligand smaller binding free energy (ΔG). |

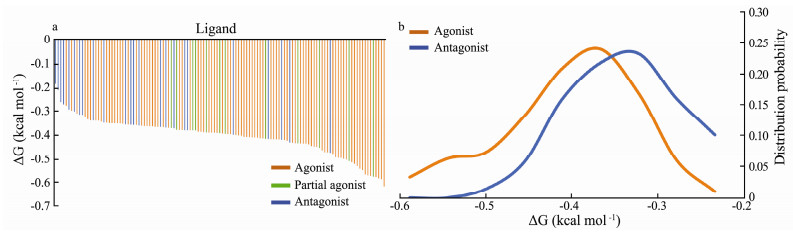

Ligand efficiency can be simply defined as ligand binding in terms of free energy per heavy atom (Andrews et al., 1984; Kuntz et al., 1999). When the values of the ligand efficiency are ranked in a descending order, most antagonists are distributed to the left of the horizontal axis, while most agonists are distributed to right of the horizontal axis (Fig. 4a). Several studies (Hibbs et al., 2009; Brams et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2017) showed that the α7 nAChR ligands with higher efficiency tend to cap the C-loop into a more closed conformation, in line with the observations that full and partial agonists are inclined to capture the conformation of the C-loop in fully and partially closed conformation. From the view of the distribution probability (Fig. 4b), the value of the ligand efficiency for the agonists is more left shifted than for the antagonists. Obviously, the ligand efficiency is more powerful than the number of heavy atoms and ligand binding affinity for differentiation the agonists from the antagonists of the nAChR. Based on the values shown in Fig. 4b, when the value of the ligand efficiency is less than -0.45 (kcal mol-1), it is more probable to be an agonist. By contrast, when the value is more than -0.3 (kcal mol-1), this ligand is more likely to be an antagonist. It has to be noted that there is still substantial overlap for the ligand efficiency between -0.45 and -0.3 (kcal mol-1). Overall, in comparison to ligand size and binding affinity, ligand efficiency could be a more reliable indicator for differentiating the agonists from the antagonists of the nAChR, as the ligand efficiency takes into account both the ligand size and ligand binding affinity.

|

Fig. 4 Distribution of the α7 nAChR ligand binding efficiency. a) Ranking distribution of the α7 nAChR agonist (orange), partial agonist (green) or antagonist (blue) based on the ligand efficiency (Δg) in order from the high to the low. b) Histogram frequency distribution of agonist (orange) or antagonist (blue) with the relationship of the α7 nAChR ligand efficiency (Δg). |

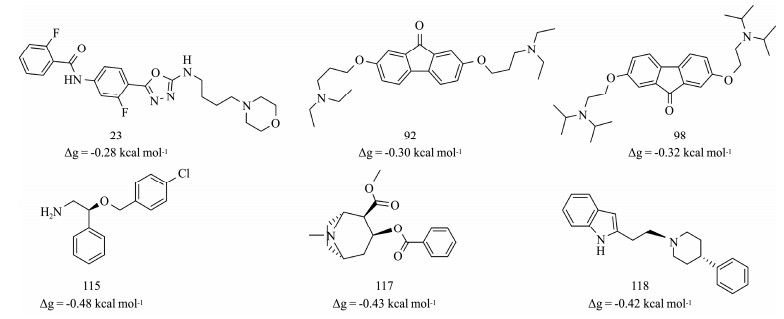

It might not be enough to differentiate the agonist and antagonist of the nAChR only from an aspect of binding affinity and ligand size. The ligand structure or configuration should be an additional component to be considered for evaluation of the ligand efficacy of the nAChR. Without consideration of the ligand configuration, its efficacy can be underestimated or overestimated only by their calculated binding efficiency. As shown in Fig. 4, some of the antagonists (115, 117, 118) can distribute in the area of high efficiency, while some of the agonists (23, 92, 98) are located in the area with low efficiency. As shown in Fig. 5, agonists 23, 92, and 98 contain multiple aromatic rings. These rings are linked through flexible and rotatable bonds, which can appropriately orient their position to form a linear shape to cross the narrow cleft of the closed C-loop (Fig.S1). Although ligands 23, 92, and 98 have more heavy atoms than normal agonists, they can still stabilize the C-loop into closed conformation. By contrast, antagonist 115, 117, and 118 are relatively small, but they have aromatic rings located at their two terminals connected by rotatable bonds. As shown in Fig.S2, they can adjust their conformation through the flexible linker to form an arched shape, with their two terminal aromatic rings forming π-π stacking with Y193 and W145 of the binding site, respectively. Hence, they can still stabilize the open conformation of the C-loop by forming π-π stacking interactions with aromatic residues of the binding site despite their relatively small ligand size.

|

Fig. 5 Structure and ligand efficiency (Δg) of compound 23, 92, 98, 115, 117 and 118. |

By statistical analysis of 123 α7 nAChR ligands, including 87 agonists, 12 partial agonists and 24 antagonists, we found that the number of heavy atoms or ligand binding affinity cannot be used for differentiation of the agonists from the antagonists of the nAChR. By contrast, the ligand efficiency that considers both ligand binding affinity and size for the agonists is overall more left shifted in comparison to the antagonists. However, it has to be noted that we still cannot use the values of the ligand efficiency to differentiate the agonists from the antagonists unless the values are either relatively high (more than -0.3 kcal mol-1) or relatively low (less than -0.45 kcal mol-1). Therefore, our study suggests that accurate prediction of the agonist or antagonist of the nAChR is challenging, and it is not enough to only consider the ligand binding affinity and size. The innate structure or configuration of the ligands has to be considered and should be used as an extra component for determination of the ligand efficacy of the nAChR in future studies.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 201762011 for R. Y.), National Laboratory Director Fund from the Qingdao National Laboratory of Marine Science and Technology (No. QNLM201709), and the NSFC-Shandong Joint Fund (No. U1406402). The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding from the above sources.

Andrews, P. R., Craik, D. J. and Martin, J. L., 1984. Functional group contributions to drug-receptor interactions. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 27: 1648-1657. DOI:10.1021/jm00378a021 (  0) 0) |

Beinat, C., Banister, S. D., Herrera, M., Law, V. and Kassiou, M., 2015. The therapeutic potential of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7 nAChR) agonists for the treatment of the cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs, 29: 529-542. DOI:10.1007/s40263-015-0260-0 (  0) 0) |

Beinat, C., Banister, S. D., Herrera, M. and Kassiou, M., 2016. The recent development of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) ligands as therapeutic candidates for the treatment of central nervous system (CNS) diseases. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 22: 2134-2151. DOI:10.2174/1381612822666160127114125 (  0) 0) |

Brams, M., Pandya, A., Kuzmin, D., van Elk, R., Krijnen, L., Yakel, J. L., Tsetlin, V., Smit, A. B. and Ulens, C. A., 2011. A structural and mutagenic blueprint for molecular recognition of strychnine and d-tubocurarine by different cys-loop receptors. PLoS Computational Biology, 9: e1001034. DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001034 (  0) 0) |

Bunnelle, W. H., Dart, M. J. and Schrimpf, M. R., 2004. Design of ligands for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: The quest for selectivity. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 4: 299-334. DOI:10.2174/1568026043451438 (  0) 0) |

Cheng, X., Wang, H., Grant, B., Sine, S. M. and McCammon, J. A., 2006. Targeted molecular dynamics study of C-loop closure and channel gating in nicotinic receptors. Plos Computational Biology, 2: e134. DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020134 (  0) 0) |

Corradi, J. and Bouzat, C., 2016. Understanding the bases of function and modulation of α7 nicotinic receptors: Implications for drug discovery. Molecular Pharmacology, 90: 288-299. DOI:10.1124/mol.116.104240 (  0) 0) |

Deneris, E. S., Connolly, J., Rogers, S. W. and Duvoisin, R., 1991. Pharmacological and functional diversity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 12: 34-40. DOI:10.1016/0165-6147(91)90486-C (  0) 0) |

Gao, F., Bren, N., Burghardt, T. P., Hansen, S., Henchman, R. H., Taylor, P., McCammon, J. A. and Sine, S. M., 2005. Agonist-mediated conformational changes in acetylcholinebinding protein revealed by simulation and intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280: 8443-8451. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M412389200 (  0) 0) |

Hansen, S. B., Sulzenbacher, G., Huxford, T., Marchot, P., Taylor, P. and Bourne, Y., 2005. Structures of Aplysia AChBP complexes with nicotinic agonists and antagonists reveal distinctive binding interfaces and conformations. Embo Journal, 24: 3635-3646. DOI:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828 (  0) 0) |

Hibbs, R. E., Sulzenbacher, G., Shi, J., Talley, T. T., Conrod, S., Kem, W. R., Taylor, P., Marchot, P. and Bourne, Y., 2009. Structural determinants for interaction of partial agonists with acetylcholine binding protein and neuronal α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Embo Journal, 28: 3040-3051. (  0) 0) |

Hopkins, A. L., Groom, C. R. and Alex, A., 2004. Ligand efficiency: A useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discovery Today, 9: 430-431. DOI:10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7 (  0) 0) |

Huang, S., Li, S. X., Bren, N., Cheng, K., Gomoto, R., Chen, L. and Sine, S. M., 2013. Complex between α-bungarotoxin and an α7 nicotinic receptor ligand-binding domain chimaera. Biochemical Journal, 454: 303-310. DOI:10.1042/BJ20130636 (  0) 0) |

Jensen, A. A., Frolund, B., Liljefors, T. and Krogsgaard-Larsen, P., 2005. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Structural revelations, target identifications, and therapeutic inspirations. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 48: 4705-4745. DOI:10.1021/jm040219e (  0) 0) |

Kalkman, H. O. and Feuerbach, D., 2016. Modulatory effects of α7 nAChRs on the immune system and its relevance for CNS disorders. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 73: 2511-2530. DOI:10.1007/s00018-016-2175-4 (  0) 0) |

Kitchen, D. B., Decornez, H., Furr, J. R. and Bajorath, J., 2004. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: Methods and applications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 3: 935-949. DOI:10.1038/nrd1549 (  0) 0) |

Kuntz, I. D., Chen, K., Sharp, K. A. and Kollman, P. A., 1999. The maximal affinity of ligands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96: 9997-10002. DOI:10.1073/pnas.96.18.9997 (  0) 0) |

Le Novere, N. and Changeux, J. P., 1995. Molecular evolution of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: An example of multigene family in excitable cells. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 40: 155-172. DOI:10.1007/BF00167110 (  0) 0) |

Li, S. X., Huang, S., Bren, N., Noridomi, K., Dellisanti, C. D., Sine, S. M. and Chen, L., 2011. Ligand-binding domain of an α7-nicotinic receptor chimera and its complex with agonist. Nature Neuroscience, 14: 1253-1259. DOI:10.1038/nn.2908 (  0) 0) |

Liu, Z., Neff, R. A. and Berg, D. K., 2006. Sequential interplay of nicotinic and GABAergic signaling guides neuronal development. Science, 314: 1610-1613. DOI:10.1126/science.1134246 (  0) 0) |

Ma, Q., Tae, H. S., Wu, G., Jiang, T. and Yu, R., 2017. Exploring the relationship between nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligand size, efficiency, efficacy and C-loop opening. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 57: 1947-1956. DOI:10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00152 (  0) 0) |

Ondachi, P. W., Castro, A. H., Luetje, C. W., Wageman, C. R., Marks, M. J., Damaj, M. I., Mascarella, S. W., Navarro, H. A. and Carroll, F. I., 2017. Synthesis, nicotinic acetylcholine binding, and in vitro and in vivo pharmacological properties of 2'-fluoro-(carbamoylpyridinyl)deschloroepibatidine analogues. Acs Chemical Neuroscience, 7: 1004-1012. (  0) 0) |

Paterson, D. and Nordberg, A., 2000. Neuronal nicotinic receptors in the human brain. Progress in Neurobiology, 61: 75-111. DOI:10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00045-3 (  0) 0) |

Romanelli, M. N., Gratteri, P., Guandalini, L., Martini, E., Bonaccini, C. and Gualtieri, F., 2007. Central nicotinic receptors: Structure, function, ligands, and therapeutic potential. ChemMedChem, 2: 746-767. DOI:10.1002/cmdc.200600207 (  0) 0) |

Séguéla, P., Wadiche, J., Dineley-Miller, K., Dani, J. A. and Patrick, J. W., 1993. Molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain alpha 7: A nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. Journal of Neuroscience, 13: 596-604. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993 (  0) 0) |

Skok, M. and Lykhmus, O., 2016. The role of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and α7-specific antibodies in neuroinflammation related to alzheimer disease. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 22: 2035-2049. DOI:10.2174/1381612822666160127112914 (  0) 0) |

Taly, A., Corringer, P. J., Guedin, D., Lestage, P. and Changeux, J. P., 2009. Nicotinic receptors: Allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 8: 733-750. DOI:10.1038/nrd2927 (  0) 0) |

Vilar, S., Cozza, G. and Moro, S., 2008. Medicinal chemistry and the molecular operating environment (MOE): Application of QSAR and molecular docking to drug discovery. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 8: 1555-1572. DOI:10.2174/156802608786786624 (  0) 0) |

Zanetti, S. R., Ziblat, A., Torres, N. I., Zwirner, N. W. and Bouzat, C., 2016. Expression and functional role of α7 nicotinic receptor in human cytokine-stimulated Natural Killer (NK) cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 29: 16541-16552. (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18