2) Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory, Zhuhai 519000, China;

3) Key Laboratory of Eutrophication and Red Tide Prevention of Guangdong Higher Education Institutes, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, China

In last several decades, as a result of an increase in bloom frequency and intensity and biogeographic expansion of benthic microalgae, Benthic Harmful Algal Blooms (BHABs) have had a growing impact in more areas, threatening human health, the survival of benthic fauna, and the economy (GEOHAB, 2012; Berdalet et al., 2017; GlobalHAB, 2017).

BHABs are mainly induced by benthic dinoflagellates of three genera: Ostreopsis, Gambierdiscus and Prorocentrum. The genus Gambierdiscus can produce ciguatoxins (CTXs), which cause ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP) in tropical regions. Ostreopsis cf. ovata produce several toxins which have been associated with human health problems during blooms (Ciminiello et al., 2008, 2012; Deeds and Schwartz, 2010; Rossi et al., 2010). Some benthic Prorocentrum spp. have been reported to produce complex toxin molecules, such as okadaic acid (OA) and its analogues (dinophysistoxins, DTXs), prorocentrolides, prorocentrol, borbotoxins, and other unknown toxins (Torigoe et al., 1988; Ten-Hage et al., 2002; An et al., 2010; Sugahara et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2017; Nascimento et al., 2017). OA and/or DTXs bioaccumulate in clams, crabs, and mussels, and are responsible for diarrhetic shellfish poisoning (DSP) to humans consuming contaminated seafood (Tubaro et al., 1996; Vale and Sampayo, 2002; Li et al., 2012).

Benthic Prorocentrum is a dominant group in the benthic dinoflagellate community distributed in a variety of marine benthic habitats (Delgado et al., 2006; Richlen and Lobel, 2011; Tester et al., 2014; Giussani et al., 2017; Boisnoir et al., 2019). Blooms caused by several harmful benthic Prorocentrum species have been recorded, e.g., Prorocentrum arabianum (a synonym of P. concavum) at the Gulf of Oman in May, 1995 (Morton et al., 2002); P. lima in the Dardanelles during the middle summer period of 2013 (Turkoglu, 2016); Prorocentrum rhathymum off the Myanmar coast in March 2012 (Su and Koike, 2013) and in the Bangaram Lagoon of Lakshadweep archipelago in March 2018 (Thomas et al., 2021). Recently, a benthic harmful P. concavum bloom occurred at Xincun Bay, Hainan Island, China, in August 2018, which is the first BHAB found in China (Zou et al., 2020). High cell densities of P. concavum were recorded, both on macrophyte substrates and in the water column (Zou et al., 2020). Extraction of a field sample of P. concavum caused an over 50% mortality rate of brine shrimp larvae (Zou et al., 2020). Though the toxin molecules have not yet been identified in this case, considering the findings of previous studies showing that P. concavum can produce unknown cytotoxic or ichthyotoxic toxins (Yasumoto et al., 1987; Morton et al., 2002), it is reasonable to believe that the bloom caused by P. concavum was harmful to the marine benthic ecosystem and a threat to public health.

Abiotic factors, including light, hydrodynamics, nutrients, and temperature, are considered to affect benthic algal abundance and population dynamics (Fraga et al., 2012), while the role of biotic factors has been less investigated. The possibility of allelopathy–any direct or indirect and commonly negative effect of one plant on another as a result of plant-produced chemical compounds released into the environment (Willis, 1985)–between macrophytes and benthic microalgae has gained great interest. This is because allelopathic interactions are especially common between fully aquatic species, and may be caused by the severe competition for space and the prevention of shade cast by epiphytic and planktonic autotrophs (Gross, 2003). The most important is that allelopathy can be an economical and environmentally-friendly way to eliminate BHABs.

Both field and laboratory studies indicate the occurrence of allelopathic interactions between macrophytes and microalgae. Phytoplankton with lower densities were found with the presence of certain macrophytes in situ, e.g., Potamogeton crispus, Chara australis, Myriophyllum verticillatum and Stratiotes aloides (Hilt et al., 2006; Mulderij et al., 2009; Pakdel et al., 2013). Nuitrient competition was of important but cannot explain the observed patterns solely. Allelopathy may occur and offer reasonable explanations. In addition, macrophytes were found to support lower epiphytes. The results of research carried out along the coasts of the northern Mediterranean Sea showed that abundances of Ostreopsis on the surface of seaweeds were significantly lower than on the rocks, which may be due to the production of allelopathic compounds (Totti et al., 2010). Many reports about allelopathy between macrophytes and microalgae were based on the laboratory studies. Inhibitory effects on microalgae growth were found when microalgae were cultured in a medium with addition of some materials, i.e., live leaves, exudates, and powders and extracts from certain macrophytes. The inhibitory properties of the macrophytes were attributed to the production and/or release of allelopathically active compounds acting as natural antialgal agents (Harrison and Chan, 1980; Gross and Sütfeld, 1994; Nakai et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2008; Vanderstukken et al., 2011; Laabir et al., 2013). Macroalgae including Corallina pilulifera, Ulva rigida, Rhodymenia pseudopalmata, Dictyota dichotoma etc. showed negative allelopathic effects on microalgae (Jeong et al., 2000; Accoroni et al., 2015). Allelopathic interaction on microalgae of several competitive aquatic angiosperms such as Myriophyllum, Ceratophyllum and Zostera were also studied extensively (Harrison and Chan, 1980; Nakai et al., 2000; Gross et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2008; Laabir et al., 2013; Amorim et al., 2019). Studies of allelopathic interactions between macrophytes and harmful benthic dinoflagellates appear rare so far. Three macroalgae tested under laboratory conditions, including U. rigida, R. pseudopalmata, and D. dichotoma, showed inhibitory effects on the growth of Ostreopsis cf. ovata (Accoroni et al., 2015). Ben Gharbia et al. (2017) reported that Ulva rigida induced a significant decrease in cell densities of three benthic dinoflagellates, Coolia monotis, Prorocentrum lima, and Ostreopsis cf. ovata, at the end of co-culturing. Understanding the relationship between harmful benthic dinoflagellates and marine macrophytes is urgent as the outbreak frequency and affected areas of BHABs are increasing and the distributions areas of harmful benthic dinoflagellates are expanding.

To investigate the possible allelopathic interactions between the BHAB dinoflagellate P. concavum and major seagrasses in Xincun Bay, we conducted a field survey of the cell densities of P. concavum on major substrates, sediment (outside and inside seagrass meadow (S. M.)), Enhalus acoroides and Thalassia hemperichi at the bloom forming site over a time course of 12 months. The results of the field survey showed that cell densities of P. concavum differ markedly between four substrates. E. acoroides supported the lowest cell densities of P. concavum. Thus, E. acoroides was selected to test its effects on P. concavum growth and photosynthetic activity under laboratory conditions to find out whether allelopathic interactions possibly occur between them.

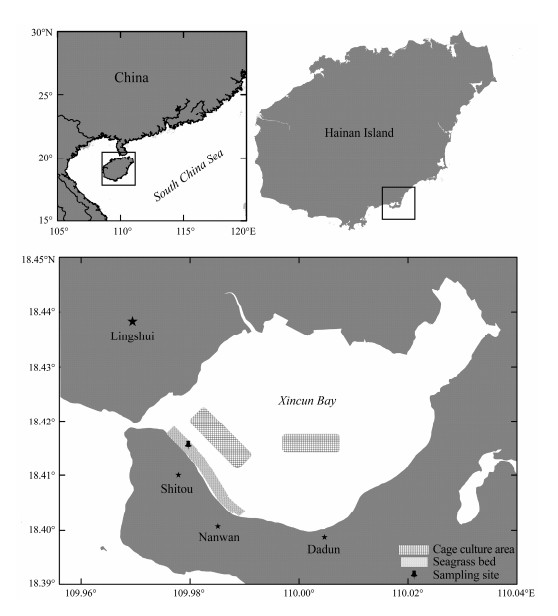

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Sample CollectionAll samples used for this study were collected in Xincun lagoon, Hainan Island (Fig.1). A harmful benthic dinoflagellate bloom caused by P. concavum was discovered in summer of 2018 at this location (Zou et al., 2020). Belonging to a tropical area and with sediments mainly constituted by fine sand-clay type sediment, the south coast of Xincun lagoon is characterized by dense and continuous seagrass beds (Yang and Yang, 2009). Three macrophytes, including E. acoroides, T. hemperichii and Halophila ovalis, constitute the seagrass meadows at the sample collection site. Among these meadows, E. acoroides and T. hemperichii occupy the most spatial coverage.

|

Fig. 1 Map of China showing the sample collection site. |

To determine the cell abundance of P. concavum on the surface of the sediment inside or outside the seagrass meadows (S. M.), substrate with the same defined area was trapped and transferred into a sealed bag, and subjected to treatments similar to those for the macrophytes described below. Fresh leaves of two macrophytes were carefully cut and put in sealed bags with the surrounding sea water, preventing the suspension of epibenthic algae on the macrophytes. Samples were put in an ice box after collection. The sealed bags containing macrophyte leaves and in situ sea water were shaken vigorously to thoroughly remove the microalgae from the macrophytes. Sea water containing re-suspended microalgae in the sealed bag was filtered through 10 μm pore size nylon mesh, and the residual sea water and nylon mesh were gently transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube. The macrophyte leaves were blotted dry before weighing. After the microalgae were fixed by Lugol solution, the samples were stored in the dark before being counted. Densities of P. concavum in the samples were counted with a counting slide after homogenization using an upright light microscope (OLYMPUS CX23).

2.3 Cultivation of P. concavumThe clonal isolate of P. concavum was established using the capillary pipette technique (Hoshaw and Rosowski, 1973) from the bloom of summer 2018. Stock cultures of P. concavum were maintained at 25℃ under a 12 h: 12 h light: dark cycle and an illumination intensity of 130 μmol photons m−2 s−1, with L1 medium (Hoshaw and Rosowski, 1973) applied by using artificial seawater (Harrison et al., 1980). P. concavum cultures used in the following experiments were cultured in the exponential phase.

2.4 E. acoroides Sampling and Pre-TreatmentLess damaged plants were selected and collected carefully to keep their leaves and belowground parts intact. Samples were washed with ambient seawater immediately to detach epiphytes, debris and sand before kept in a plastic bag filled with in situ sea water. Afterwards, the E. acoroides samples were washed carefully by using filtered artificial seawater (FASW), and then observed using a stereomicroscope to make sure that the epiphytes were removed as much as possible. Finally, the macrophytes were treated with chloramphenicol solution (50 mg L−1), and then rinsed in FASW twice to remove bacteria.

2.5 Co-Incubations of P. concavum and Fresh E. acoroides LeavesThree different weights of fresh E. acoroides leaves, 2, 4, and 8 g L−1 fresh weight (FW), were tested on the dinoflagellate P. concavum. Germanium dioxide (6 mg L−1) was added to the culture media used in these co-incubation experiments to prevent the growth of diatoms. Clean fresh leaves of E. acoroides were blotted dry with filter paper, cut into fragments, weighed, and put separately into 250 mL cell culture flasks containing 80 mL culture medium inoculated with a concentration of 500 cells mL−1 of P. concavum. The obtained tested concentrations of E. acoroides leaves were comparable to records observed in the field survey (Huang and Huang, 2009). All controls were prepared in the way as same as the treatments, but without addition of macrophyte leaves. Both treatments and controls were performed in triplicate and incubated in an incubator under the conditions described above (Section 2.3) for 10 d. Every 2 days, two samples (1.2 mL each) were taken from each flask after homogenization of the medium. Then one was fixed by adding Lugol solution and preserved in the darkness to assess the cell densities, and the other sample was acclimated in the dark for 15 min before measuring photosynthesis activity. At the end of the experiment, 1 aliquot (30 mL) was taken from each flask. After the pH was measured, the aliquots were filtered (Whatman GF/F, diameter 25 mm, porosity 0.7 μm) and stored at −20℃ using polyethylene bottles for nutrient analysis.

2.6 Preparation of an Aqueous Extract of E. acoroidesFresh leaves of E. acoroides, kept in sealed bags filled with a little sea water to avoid evaporation, were stored in an ice box after being collected in situ, and were transferred to the laboratory immediately. The E. acoroides leaves were cleaned with tap water to detach epiphytes and debris on the leaves, before being dried in the shade at room temperature. After its weight reached a constant, the E. acoroides leaves were ground carefully using a mortar and pestle, and then stored in an air-tight centrifuge tube in the dark at 4℃ until use.

Ground E. acoroides material was extracted with artificial seawater (1 L solvent per 20 g plant dry mass) at 25℃ in the dark for 48 h, using a magnetic stirrer. The crude extract was filtered through 20 μm pore size nylon mesh and a 0.22 μm pore size filter (Millipore MCE) successively to eliminate debris and bacteria, and then was stored at 4℃ in the dark until use.

2.7 Cultures with a Crude Aqueous Extract of E. acoroidesDifferent volumes of crude aqueous extract of E. acoroides were added to tissue culture flasks containing autoclaved artificial sea water to obtain final concentrations equivalent to 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2 g DW (dry weight) per liter of E. acoroides. The tissue culture flasks were inoculated with P. concavum cells to obtain a final cell density of about 500 cells mL−1 after the nutrients were added as described previously. The final culture volume was 100 mL. Flasks containing 500 cells mL−1 P. concavum without the addition of the crude aqueous extract of E. acoroides were used as controls. All treatments and controls were carried out in triplicate. The incubation of the flasks were under the same conditions as previously described for two weeks. Two kinds of aliquots (1 and 1.5 mL) were taken from every flask after the medium was homogenized every 2 days, while 1 mL aliquots were fixed with Lugol solution and stored in the dark before counting, and 1.5 mL aliquots were used to assess the photosynthetic activity of the microalgae.

2.8 Determination of P. concavum GrowthP. concavum cell densities were monitored every 2 days as described previously. To express the growth of microalgae, specific growth rates (μ) were determined using the equation:

| $ \mu = \frac{{\ln {N_t} - ln{N_0}}}{T}, $ | (1) |

where Nt and N0 are the final density and the initial density, respectively, and T is the interval time (days) of two measurements. Following the method of Guillard (1973), the maximum specific growth rate (μmax) was calculated using the cell densities at the beginning (N0) and the end (Nt) of the exponential phase. Microalgae cell density reduction of the treatments in comparison of the controls were calculated by the equation:

| $ x(\%) = (1 - \frac{{{N_t}}}{{{N_0}}}) \times 100, $ | (2) |

where Nt and N0 are the cell density of the treatments and the controls, respectively.

2.9 Determination of P. concavum Photosynthetic ActivityThe photosynthesis efficiency of the microalgae was assessed by construction of Rapid Light Curves (RLCs), using parameters acquired from measurements of PHYTO-PAM (WALZ, Germany). Microalgae samples were measured after the 15 min dark-adaption period. RLCs were fitted with the equation proposed by Platt et al. (1980):

| $ rETR = {P_S} \times (1 - \exp (- \alpha \times I/{P_S})) \times \exp (- \beta \times I/{P_S}), $ | (3) |

where PS is the coefficient relevant to maximal Relative Electron Transport Rate (rETRmax), I is the actinic light intensity, α is the initial slope of RLCs reflecting the efficiency of light energy utilization, and β is light suppression parameter. When β = 0, rETRmax is PS and rETRmax was calculated through equation

| $ \begin{gathered} r E T R_{\max }=P_S \times(\alpha /(\alpha+\beta)) \times(\beta /(\alpha+\beta)) \wedge(\beta / \alpha) \\ \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\text { at } \beta>0. \end{gathered}$ | (4) |

Meanwhile, the Fv/ Fm, a core parameter reflecting the maximum quantum yield of PSII photochemistry, was used to assess the microalgae physiological status measured by the same instruments mentioned above.

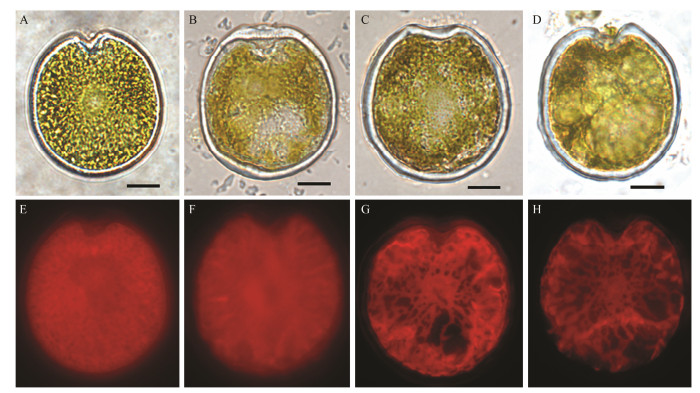

2.10 Effect of E. acoroides Aqueous Extract on P. concavum MorphologyDinoflagellate cell morphology were studied through a light and fluorescence microscope, Olympus BX 61 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and photographs were taken with a camera of QImaging Retiga 4000R (QImaging, Surrey, British Columbia, Canada) at the end of the experiment (Day 14). Characteristics of the nucleus were observed after the cells of the microalgae had been stained with Sybr Green (1:100000 V/V, Sigma Aldrich, Saint louis, USA) for 1 min. The arrangements of chloroplasts in the microalgae cells were also examined through chloroplast autofluorescence observed under the fluorescence microscope.

2.11 Nutrient AnalysisAnalysis of the main nutrients, including NO3−, NO2−, and PO43− at the end of the co-incubation experiment of P. concavum and fresh leaves of E. acoroides, was conducted following the methods described in previous researches (Bendschneider and Robinson, 1952; Mullin and Riley, 1955; Murphy and Riley, 1962). The nitrate is reduced to the nitrite using a cadmium-copper filings column. The nitrite is determined using spectrophotometry after reacting with sulphanilamide and N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine successively. Exact nitrate concentration in samples was acquired by subtracting the nitrite concentration from the nitrate concentration. The phosphorus reacts with Ammonium molybdate, and then the product is reduced by Ascorbic acid before determining with spectrophotometry.

2.12 Statistical AnalysisAll descriptive analytical values presented are in the form of the mean ± standard error (SE). When data were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test, α = 0.05) and the variances were homogeneous (Levene test, α = 0.05), data were analyzed by Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA. In some cases, transformations were needed to remove heteroscedasticity. Tukey's pairwise comparison test or Duncan's multiple range test were applied when one-way ANOVA revealed significant effects. When transformations failed to make the data fit the assumptions of parametric tests, non-parametric tests (i.e., Kruskal-Wallis test) were performed. All data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA). It was considered significant when P < 0.05.

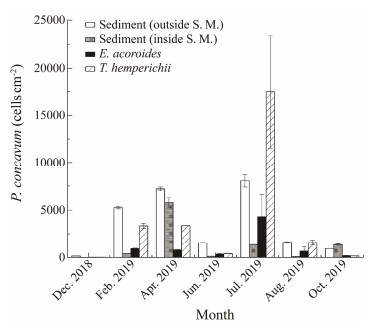

3 Results 3.1 Distribution of P. concavum on Sediments and Macrophytes In SituCell densities of P. concavum on sediments and macrophytes fluctuated dramatically throughout the year (December, 2018–October, 2019) (Fig.2). P. concavum cells on three substrates, sediment (outside S. M.), E. acoroides, T. hemperichii, reached maximum densities in July, 2019 (8053, 4304, and 17483 cells cm−2 for sediment (outside S. M.), E. acoroides, and T. hemperichii respectively) while the maximum densities of P. concavum on sediment (inside S. M.) (5798 cells cm−2) was recorded in April, 2019. The minimum cell densities on four substrates were all registered in December 2018 (132, 0, 6, and 7 cells cm−2 for sediment (outside S. M.), sediment (inside S. M.), E. acoroides, and T. hemperichii respectively). Two-way ANOVA revealed that both substrate type and month significantly affected the cell abundances of P. concavum (P = 0.000 for both substrate type and month). Sediment (outside S. M.) and T. hemperichii supported significantly higher cell abundances of P. concavum than Sediment (inside S. M.) and E. acoroides (Student-Neuman-Keuls test, P < 0.05). And there is no significant difference between cell abundances on Sediment (outside S. M.) and T. hemperichii and between Sediment (inside S. M.) and E. acoroides. As for month, Student-Neuman-Keuls test separated seven months into three clusters. Cell densities of P. concavum in July, 2019 were significantly higher than those in the other six months followed by cell densities in April, 2019, which was significantly higher than those in the other five months.

|

Fig. 2 Cell densities of P. concavum on four substrates over 12 months (December, 2018–October, 2019). The results of two-way ANOVA showed that cell densities of P. concavum were significantly affected by substrate type and month (P = 0.00 for both factors). |

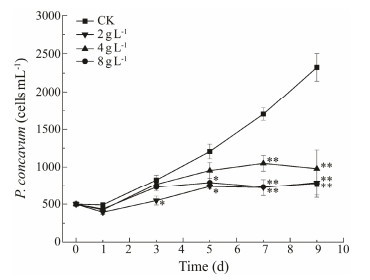

The results showed that P. concavum growth was significantly inhibited by fresh E. acoroides leaves. Though the specific growth rates of P. concavum were 0.23, 0.23, and 0.25 d−1 for treatments with addition of 2, 4 and 8 g L−1 (FW) leaves, respectively, which was comparable to that of the controls (0.19 d−1). Cultures with the treatments entered stationary phases quickly, after just a few days of exponential growth (2 days for 4 and 8 g L−1 treatments, 4 days for 2 g L−1 treatments) (Fig.3). Compared to the controls, cell abundances of P. concavum were reduced in a range of 58% to 66% across all treatments at the end of the experiments. The inhibitory effect was marked, as cell densities of P. concavum in all the treatments were significantly lower than those in the controls in the last two sampling days of the experiment (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.000 and P = 0.001 for day 7 and day 9, respectively). Tukey's pairwise comparison test separated the treatments from the controls, and no significant difference was revealed among the effects of three different concentrations.

|

Fig. 3 Growth pattern of P. concavum cells growing with different weights of fresh leaf fragments of E. acoroides. * and ** indicate statistically significant differences with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05), and Tukey's pairwise comparison test (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 respectively) when compared to the controls. |

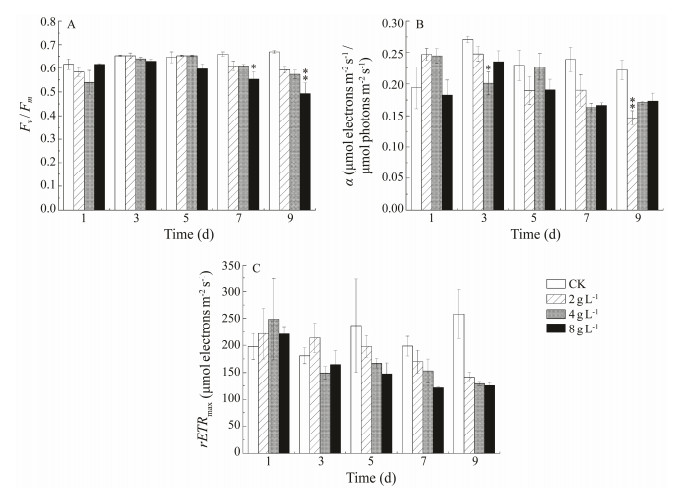

Regarding two parameters, α and rETRmax, derived from the fitting of RLCs reflecting photosynthesis activity of microalgae cells, weak effects were observed in co-incubation of P. concavum and fresh E. acoroides leaves (Figs.4 B and C). The initial slope (α), reflecting the efficiency of light energy utilization, of the three treatments was lower than that of the controls on days 3, 7 and 9. Statistically significant differences were recorded between the controls and the medium concentration treatment on day 3 (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.044; Tukey's pairwise comparison test, P = 0.033), and between the controls and the lowest concentration treatment on day 9 (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.011; Tukey's pairwise comparison test, P = 0.008). At the end of the experiment, the reduction of α in all the treatments compared to the controls ranged from 22% to 34%. As for rETRmax of microalgae in the treatments, obvious but not statistically significant decreases between 45% and 51% was found when compared to the controls (Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.066) on day 9.

|

Fig. 4 Photosynthetic parameters of P. concavum cells co-incubated with different weights of fresh E. acoroides leaves. * and ** indicate statistically significant differences with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05), and Tukey's pairwise comparison test (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) when compared to the controls. |

Fresh E. acoroides leaves induced more important inhibitory effects on Fv/ Fm of microalgae cultures in the treatments, revealing that the microalgae physiological status was undermined by the presence of fresh E. acoroides leaves (Fig.4A). The Fv/ Fm of cultures co-incubated with the highest concentration of leaves decreased consistently during day 3 and day 7. The decrease became statistically significant at day 7 (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.034; Tukey's pairwise comparison test, P = 0.022) and more pronounced at day 9 (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.007; Tukey's pairwise comparison test, P = 0.005) in comparison to the controls. The Fv/ Fm of cultures in the other treatments with lower concentrations of leaves also underwent reductions, but none of those decreases was statistically significant.

3.2.3 On chemical-physical properties of culture mediaIn co-incubation of P. concavum and fresh E. acoroides leaves, concentrations of major nutrients in the media were affected by the fresh E. acoroides leaves (Table 1). The concentration of NO3− in medium with the highest concentration of leaves was significantly lower than that of the controls at the end of the experiment (Kruskal-Wallis test P = 0.019, pairwise comparison test P = 0.019). However, it remained saturated for dinoflagellate growth. Marked decreases of PO43− concentrations in the treatments were observed too, in which the decrease in cultures with addition of the medium concentration of leaves was statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis test P = 0.033, pairwise comparison test P = 0.028). Regarding the pH of the media in the co-incubation experiment, no significant difference was revealed between the treatments and the controls at the end of the experiment. Comparing values of pH in different treatments, a significantly higher value was observed in the treatments with the medium concentration of leaves than that in the treatments with the highest concentration of leaves (Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.019, pairwise comparison test, P = 0.017).

|

|

Table 1 Results of the Kruskal-Wallis test and pairwise comparison test of the nutrient concentrations (μmol L−1) and pH (mean ± SE) in the co-incubation experiment at the end of the experiment (*P < 0.05) |

Aqueous extracts of E. acoroides leaves reduced the growth of P. concavum (Fig.5). After exposure of 24 h, cell densities in treatments with 1.6 and 3.2 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts were significantly lower than those in the controls (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.002; Tukey's pairwise comparison test, P < 0.05) while no difference were recorded between cell densities in other treatments with addition of lower concentrations of aqueous extracts and the controls. Growth rates of cultures in treatments were comparable with those of the controls (0.20 d−1) during exponential growth phases. P. concavum cultures in the controls and the treatments with addition of 0.4 and 0.8 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts remained in exponential growth during day 1 and the end of the experiment (day 13). P. concavum cultures with 3.2 and 1.6 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts entered stationary phase at day 5 and day 11 respectively. In comparison to the controls, cell densities in the treatments with two highest concentrations of aqueous extracts were significantly lower (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.000; Tukey's pairwise comparison test, P < 0.05) at the end of the experiment (day 13). Cell densities reduction was 51% and 76% for 1.6 and 3.2 g DW L−1 treatments respectively. Tukey's pairwise comparison test divided the controls and the treatments into three clusters corresponding to the concentrations of aqueous extracts applied, suggesting that the inhibitory effects induced by aqueous extracts of E. acoroides leaves were dose-dependent.

|

Fig. 5 Growth patterns of P. concavum cells growing with addition of aqueous extraction of E. acoroides. The letters, a, b, and c, indicate statistically significant differences between cell abundances in the control and treatments at the end of the experiment (one-way ANOVA P < 0.05, Tukey's pairwise comparison test P < 0.05). |

Aqueous extracts of E. acoroides leaves caused inhibitory effects on Fv/ Fm of P. concavum cells (Fig.6A). Fv/ Fm of P. concavum cells in the controls ranged from 0.53 to 0.58, suggesting that cultures of the controls were in healthy condition during the incubation period. 0.4 and 0.8 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts did not show any negative effects on Fv/ Fm of P. concavum cells. Inhibition on Fv/ Fm of microalgal cells caused by 1.6 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts was statistically significant at day 5 (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.002; Tukey's pairwise comparison test, P = 0.050). Fv/ Fm of P. concavum cells in the treatments with addition of 3.2 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts were lower than those in the controls throughout the experiment. The inhibitory effect of 3.2 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts was statistically significant (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05; Tukey's pairwise comparison test, P < 0.05) during day 5 and the end of the experiment (day 13). Inhibition on α of P. concavum cells induced by aqueous extracts of E. acoroides leaves was observed too (Fig.6B). The α value of P. concavum cells cultured with addition of 3.2 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts was significantly lower than that of the controls at day 11. No significant difference was observed between rETRmax of the treatments and the controls over the course of the experiment (Fig.6C).

|

Fig. 6 Photosynthetic parameters of P. concavum cells growing with addition of aqueous extraction of E. acoroides. The letters, a, b, and c, indicate statistically significant differences between Fv/Fm of the control and treatments with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05), and Tukey's pairwise comparison test (P < 0.05). ** indicate statistically significant differences with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05), and Tukey's pairwise comparison test (P < 0.01) when compared to the controls. |

Observations of cell morphology at the end of the experiment revealed some obvious morphological damage to the cells of P. concavum. Plasmolysis was observed in the treatments with addition of 1.6 and 3.2 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts of E. acoroides. Weaker chloroplast autofluorescence was observed in the treatments with 3.2 g DW L−1 aqueous extracts, associated with the arrangement of chloroplasts being less compact than those of the controls (Fig.7).

|

Fig. 7 Light (A–D), fluorescence (E–H) microscope photographs of P. concavum cells. A and E, control; B and F, cells cultured with the addition of 1.6 g DW L−1 aqueous extract; and cells cultured with the addition of 3.2 g DW L−1 aqueous extract (C, D, G, and H). Scale bars, 10 μm. |

Epibenthic dinoflagellates were found to colonize a variety of substrates, and some species were reported to be more abundant on certain substrates, which were called substrate preference. Some epibenthic dinoflagellate species present preferences among biotic substrates. The results of surveys conducted along the northwestern coast of Cuba showed that both P. lima and Gambierdiscus toxicus presented in much higher abundances on Phaeophyta than on Chlorophyta and Rhodophyta (Delgado et al., 2006). Boisnoir et al. (2019) reported that in the Lesser Antilles, epibenthic dinoflagellate group were more abundant on Thalassia testutinium than those on Halodule and Halophila. The distribution of Prorocentrum spp. and Coolia spp. followed the same pattern. In contrast, cell abundances of Gambierdiscus spp. on Halophila were higher than those on T. testutinium, Halodule, and Syringodium spp.. Consistently, T. hemperichii supported more cells of P. concavum than E. acoroides, suggesting preference of P. concavum on T. hemperichii. Moreover, some species were found to show preference for abiotic substrates. O. ovata occurred in significantly lower densities on thalli of seaweed in comparison with those on abiotic substrates including mollusc shells and rocks (Totti et al., 2010). Similarly, P. concavum colonized on sediment (outside S. M.) showed significantly higher abundances than those settled on E. acoroides.

Both abiotic and biotic factors need to be taken into account when trying to explain the observed pattern of epibenthic dinoflagellates distribution. The attributes of the substratum, such as the structure, architecture, and texture of surface have been suggested to affect the substrate preference of epiphytic dinoflagellates (Parsons and Preskitt, 2007). In Hawaii, P. lima, Gambierdiscus sp. and C. monotis preferred macroalgae with microfilament morphology and O. sp. 1 showed preferences for macroblade macroalgae (Parsons and Preskitt, 2007). Boisnoir et al. (2019) suggested that morphology alone cannot fully account for the observed patterns. The physical and chemical environmental conditions of microhabitats (light intensity, flowrelated disturbance and nutrient availability) may also interfere with the interaction between epibenthic dinoflagellates and the substrate (Gregg and Rose, 1982). Nutrient competition between macrophytes and microalgae can lead to a decrease in microalgae on macrophytes. Filzgerald (1969) suggested that a decrease in epiphyte growth on various aquatic angiosperms and macroalgae was caused by nitrogen limitations, in consideration of the inhibitory effects on epiphytes in cultures of Cladophora sp., Pithophtora oedogonium, Ceratophyllum sp., Myriophyllum sp., and so forth. E. acoroides growing at the sample collection site were under phosphorus limitation (Yu et al., 2012), indicating nutrient competition may exist between the epiphytes and E. acoroides, and possibly have a negative effect on epiphytic growth. Herbivory could also be effective in controlling cell abundance of epiphytes on macrophytes. Bire et al. (2013) reported that Ostreopsis spp. and associated epibenthic dinoflagellates can be consumed by herbivores when they are browsing on macroalgae. Besides, living substrate supports a lower density of epibionts, indicating the possibility of allelopathic chemical production (Pawlik, 1993). Gloss suggested that the prevention of shading caused by epiphytic and planktonic primary producers may be one of the ultimate causes for allelopathic interaction in fully aquatic speices (Gross, 2003). In Xincun Bay, severe shading caused by epiphytes did occur. A dramatic increase in epiphytes on E. acoroides as a result of the increase in nitrogen loading, related to the development of aquaculture and tourism, causing shading on the E. acoroides, has undermined the photosynthesis of E. acoroides (Huang and Huang, 2009), which may induce allelopathic interaction of E. acoroides with epiphytes.

4.2 Allelopathic Effect of Macrophytes on MicroalgaeInhibitory effects of macrophytes on microalgae can be induced by several mechanisms, such as the competition for light or nutrients, changes in pH, and the production of allelopathic chemicals. The photosynthesis of dense submergent macrophytes can elevate the concentrations of DO (dissolved oxygen) and the pH (Frodge et al., 1990), making the environment unfavorable for microalgae growth. In the co-incubation experiment, no significant changes of pH levels in the treatments were recorded at the end of the experiment, suggesting that the inhibition caused by the macrophytes E. acoroides was not due to changes in pH. In contrast, significant losses of nutrients in the medium of the treatments were shown at the end of the experiment. A remarkable feature of seagrasses, known as luxury consumption, is their action of taking up nutrients in excess of their immediate metabolic needs (Romero et al., 2006), and may account for these losses. However, the residual concentrations of nitrogen (NO3−) were still at saturation levels for the requirements of dinoflagellates (Smayda, 1997). The possibility of phosphate limitation in the treatments with addition of 4 g L−1 FW leaves, in which the lowest concentration of PO43− (0.7 μmol L−1) was recorded, alone cannot explain the inhibitory effects on P. concavum in this co-incubation experiment, as the concentrations of phosphate in the other two treatments were above the limitation levels (Smayda, 1997). Finally, it is very likely that the E. acoroides leaves inhibited the growth of P. concavum through the release of allelopathic chemicals. The inhibitory effects recorded in the cultures of P. concavum growing with a crude aqueous extract of E. acoroides further suggested the potential of E. acoroides to produce chemicals that act as anti-algae compounds suppressing the growth and even causing death of P. concavum cells. Similar inhibitory effects of aqueous extract from E. acoroides on microalgae have been reported before (Zhu et al., 2019). The allelopathic interactions on microalgae caused by macrophytes suggested that macrophytes are promising alternative resources to control HABs (Hu and Hong, 2008; Tang and Gobler, 2011).

Though chemical analyses of allelopathic compounds in E. acoroides were not performed in this study, we recognize that such an interaction likely occurred. Multiple biological activities have been found in E. acoroides extracts, including antioxidant and antibacterial activities, chemical defenses toward herbivores, and antialgal effects (Paul et al., 1990; Qi et al., 2008; Kannan et al., 2010, 2012; Zhu et al., 2019). So far, various phenolic acids and flavones, namely p-coumaric acid, p-hydroxy benzoic acid, protocatechuic acid, ferulic acid, gallic acid, luteolin, apigenin, luteolin-4-O-glucuronide, luteolin-3-glucuronide, luteolin-3', 7-O-dig-lucuronides, luteolin-7-O-glucuronide, chrysoeriol, and chrysoeriol-7-O-glucuronide, have been identified from the extracts of E. acoroides (Rajeshwari, 1990; Athiperumalsami et al., 2008; Qi et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2019). Some of these compounds have been shown to be antialgal. Low-molecular phenols isolated from Schoenoplectus lacustris have been reported to show antialgal effects toward the green alga Selenastrum capricornutum (D'Abrosca et al., 2006), and the most active one was Protocatechuic acid. Gallic acid, together with the other three polyphenols identified from the water-soluble fraction of Myriophyllum spicatum, were responsible for the algicidal effects of M. spicatum on Microcystis aeruginosa (Nakai et al., 2000). Furthermore, it has been reported that the aqueous extracts of E. acoroides can inhibit the growth of Phaeocystis globosa, and luteolin-7-O-glucuronide was found to be one of the incriminated compounds (Zhu et al., 2019).

4.3 Effect of E. acoroides on P. concavum Photosynthesis and MorphologyThe inhibition of photosynthetic activity, the primary physiological process of competing autotrophs, is an effective defense strategy induced by a variety of aquatic angiosperms (Gross, 2003). The results of the experiments with E. acoroides aqueous extract showed that the photosynthetic efficiency of P. concavum cells was inhibited by the extract. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2019) reported that the chlorophyll-a content and photosynthetic efficiency of Phaeocystis globosa were reduced by an aqueous extract of E. acoroides. Previous studies showed that PSII is the target site for the majority of allelochemicals (Gross, 2003). Leu et al. (2002) reported that tellimagrandin II, the major active substance of Myriophyllum spicatum, caused a higher temperature of the maximum temperature of the B-band and a higher redox midpoint potential to non-heme iron, proving that tellimagrandin II inhibits the activities of PSII. Two allelopathic polyphenols, pyrogallic acid and gallic acid, could induce significant decreases of PSII and the entire electron transport chain activities of the microalga M. spicatum (Zhu et al., 2010). However, the details of photosynthetic efficiency inhibition induced by E. acoroides aqueous extract require further research.

Morphological and structural cellular changes, including deformed cells, lysis of the membrane, plasmolysis, vacuolization, and degradations in intracellular organelles were reported when microalgae cells were exposed to certain extracts of macrophytes, or coexisted with the macrophytes (Laabir et al., 2013; Ben Gharbia et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2019). Our results that two highest concentrations of E. acoroides aqueous extract altered the morphology of P. concavum cells are in accordance with the observation in Phaeocystis globosa cultured with E. acoroides aqueous extract. The damages of P. globosa included vacuolization, plasmolysis, and organelle destruction (Zhu et al., 2019).

In conclusion, our results highlighted the significant differences of the abundance of the benthic HAB dinoflagellate P. concavum on sediments and macrophytes, and the negative effects of submergent seagrass E. acoroides on P. concavum, which can very likely be attributed to allelopathy. Put another way, dense microalgae threaten the survival of seagrasses, and the reduction in the occupation of seagrass may in turn facilitate the formation of microalgae blooms. Our results, together with other experiments demonstrating the inhibitory effects of macrophytes on HAB microalgae, may provide new strategies for coastal management to mitigate, control, or prevent HABs.

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42076144, 41876173), and the Special Foundation for National Science and Technology Basic Research Program of China (No. 2018FY100 200).

Accoroni, S., Percopo, I., Cerino, F., Romagnoli, T., Pichierri, S., Perrone, C., et al., 2015. Allelopathic interactions between the HAB dinoflagellate Ostreopsis cf. ovata and macroalgae. Harmful Algae, 49: 147-155. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2015.08.007 (  0) 0) |

Amorim, C. A., Moura-Falcão, R. H. D., Valença, C. R., Souza, V. R. D., and Moura, A. D. N., 2019. Allelopathic effects of the aquatic macrophyte Ceratophyllum demersum L. on phytoplankton species: Contrasting effects between cyanobacteria and chlorophytes. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia, 31: e21. DOI:10.1590/s2179-975x1419 (  0) 0) |

An, T., Winshell, J., Scorzetti, G., Fell, J. W., and Rein, K. S., 2010. Identification of okadaic acid production in the marine dinoflagellate Prorocentrum rhathymum from Florida Bay. Toxicon, 55(2): 653-657. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.08.018 (  0) 0) |

Athiperumalsami, T., Kumar, V., and Jesudass, L. L., 2008. Survey and phytochemical analysis of seagrasses in the Gulf of Mannar, southeast coast of India. Botanica Marina, 51(4): 8. DOI:10.1515/BOT.2008.038 (  0) 0) |

Ben Gharbia, H., Kefi-Daly Yahia, O., Cecchi, P., Masseret, E., Amzil, Z., Herve, F., et al., 2017. New insights on the speciesspecific allelopathic interactions between macrophytes and marine HAB dinoflagellates. PLoS One, 12(11): e0187963. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0187963 (  0) 0) |

Bendschneider, K., and Robinson, R. J., 1952. A new spectrophotometric method for the determination of nitrite in sea water. Marine Research, 11: 87-96. (  0) 0) |

Berdalet, E., Tester, P. A., Chinain, M., Fraga, S., Lemée, R., Litaker, W., et al., 2017. Harmful algal blooms in benthic systems: Recent progress and future research. Oceanography, 30(1): 36-45. DOI:10.5670/oceanog.2017.108 (  0) 0) |

Biré, R., Trotereau, S., Lemée, R., Delpont, C., Chabot, B., Aumond, Y., et al., 2013. Occurrence of palytoxins in marine organisms from different trophic levels of the French Mediterranean coast harvested in 2009. Harmful Algae, 28: 10-22. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2013.04.007 (  0) 0) |

Boisnoir, A., Pascal, P. Y., Cordonnier, S., and Lemee, R., 2019. Spatio-temporal dynamics and biotic substrate preferences of benthic dinoflagellates in the Lesser Antilles, Caribbean Sea. Harmful Algae, 81: 18-29. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2018.11.012 (  0) 0) |

Ciminiello, P., Dell'Aversano, C., Fattorusso, E., Forino, M., Tartaglione, L., Grillo, C., et al., 2008. Putative palytoxin and its new analogue, ovatoxin-a, in Ostreopsis ovata collected along the ligurian coasts during the 2006 toxic outbreak. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 19(1): 111-120. DOI:10.1016/j.jasms.2007.11.001 (  0) 0) |

Ciminiello, P., Dell'Aversano, C., Iacovo, E. D., Fattorusso, E., Forino, M., Tartaglione, L., et al., 2012. Unique toxin profile of a Mediterranean Ostreopsis cf. ovata strain: HR LC-MSn characterization of ovatoxin-f, a new palytoxin congener. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 25(6): 1243-1252. DOI:10.1021/tx300085e (  0) 0) |

D'Abrosca, B., Dellagreca, M., Fiorentino, A., Isidori, M., Monaco, P., and Pacifico, S., 2006. Chemical constituents of the aquatic plant Schoenoplectus lacustris: Evaluation of phytotoxic effects on the green alga Selenastrum capricornutum. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 32(1): 81-96. DOI:10.1007/s10886-006-9354-y (  0) 0) |

Deeds, J. R., and Schwartz, M. D., 2010. Human risk associated with palytoxin exposure. Toxicon, 56(2): 150-162. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.05.035 (  0) 0) |

Delgado, G., Lechuga-Devéze, C. H., Popowski, G., Troccoli, L., and Salinas, C. A., 2006. Epiphytic dinoflagellates associated with ciguatera in the northwestern coast of Cuba. Revista de Biología Tropical, 54: 299-310. (  0) 0) |

Filzgerald, G. P., 1969. Some factors in the competition or antagonism among bacteria, algae, and aquatic weeds. Journal of Phycology, 5(4): 351-359. DOI:10.1111/j.1529-8817.1969.tb02625.x (  0) 0) |

Fraga, S., Rodríguez, F., Bravo, I., Zapata, M., and Marañón, E., 2012. Review of the main ecological features affecting benthic dinoflagellate blooms. Cryptogamie, Algologie, 33(2): 171-179. DOI:10.7872/crya.v33.iss2.2011.171 (  0) 0) |

Frodge, J. D., Thomas, G. L., and Pauley, G. B., 1990. Effects of canopy formation by floating and submergent aquatic macrophytes on the water quality of two shallow Pacific Northwest lakes. Aquatic Botany, 38(2): 231-248. DOI:10.1016/0304-3770(90)90008-9 (  0) 0) |

GEOHAB, 2012. Global Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms Core Research Project: HABs in Benthic Systems. Berdalet, E., et al., eds., IOC of UNESCO and SCOR, Paris and Newark, 64pp.

(  0) 0) |

Giussani, V., Asnaghi, V., Pedroncini, A., and Chiantore, M., 2017. Management of harmful benthic dinoflagellates requires targeted sampling methods and alarm thresholds. Harmful Algae, 68: 97-104. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2017.07.010 (  0) 0) |

GlobalHAB, 2017. Global Harmful Algal Blooms, Science and Implementation Plan. Berdalet, E., et al., eds., IOC of UNESCO and SCOR, Delaware and Paris, 64pp.

(  0) 0) |

Gregg, W. W., and Rose, F. L., 1982. The effects of aquatic macrophytes on the stream microenvironment. Aquatic Botany, 14: 309-324. DOI:10.1016/0304-3770(82)90105-X (  0) 0) |

Gross, E. M., 2003. Allelopathy of aquatic autotrophs. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 22(3-4): 313-339. DOI:10.1080/713610859 (  0) 0) |

Gross, E. M., and Sütfeld, R., 1994. Polyphenols with algicidal activity in the submerged macrophyte Myriophyllum spicatum L. Acta Hortic. International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS). Leuven, Belgium, 710-716.

(  0) 0) |

Gross, E. M., Erhard, D., and Iványi, E., 2003. Allelopathic activity of Ceratophyllum demersum L. and Najas marina ssp. intermedia (Wolfgang) Casper. Hydrobiologia, 506(1): 583-589. DOI:10.1023/B:HYDR.0000008539.32622.91 (  0) 0) |

Guillard, R. L. R., 1973. Division rates. In: Handbook of Phycological Methods: Cultures Methods and Growth Measurements. Stein, J. R., ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 290-311.

(  0) 0) |

Harrison, P. G., and Chan, A. T., 1980. Inhibition of the growth of micro-algae and bacteria by extracts of eelgrass (Zostera marina) leaves. Marine Biology, 61(1): 21-26. DOI:10.1007/BF00410338 (  0) 0) |

Harrison, P. J., Waters, R. E., and Taylor, F. J. R., 1980. A broad spectrum artificial sea water medium for coastal and open ocean phytoplankton. Journal of Phycology, 16(1): 28-35. DOI:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1980.00028.x (  0) 0) |

Hilt, S., Ghobrial, M. G. N., and Gross, E. M., 2006. In situ allelopathic potential of Myriophyllum Verticillatum (Haloragaceae) against selected phytoplankton species Journal of Phycology, 42 (6): 1189-1198, DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00286.x.

(  0) 0) |

Hoshaw, R. W., and Rosowski, J. R., 1973. Methods for microscopic algae. In: Handbook of Phycological Methods. Stein, J. R., ed., Cambridge University Press, New York, 53-67.

(  0) 0) |

Hu, H., and Hong, Y., 2008. Algal-bloom control by allelopathy of aquatic macrophytes–A review. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering in China, 2(4): 421-438. DOI:10.1007/s11783-008-0070-4 (  0) 0) |

Huang, D. J., and Huang, X. P., 2009. Effects of caged fish farm on the biological and ecological characteristics of Enhalus acoroides in Xincun Lagoon of Hainan, China. Journal of Oceanography in Taiwan Strait, 28(2): 199-204. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-8160.2009.02.008 (  0) 0) |

Jeong, J. H., Jin, H. J., Sohn, C. H., Suh, K. H., and Hong, Y. K., 2000. Algicidal activity of the seaweed Corallina pilulifera against red tide microalgae. Journal of Applied Phycology, 12(1): 37-43. DOI:10.1023/A:1008139129057 (  0) 0) |

Kannan, R. R. R., Arumugam, R., and Anantharaman, P., 2010. In vitro antioxidant activities of ethanol extract from Enhalus acoroides (L. F.) Royle. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 3(11): 898-901. DOI:10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60216-7 (  0) 0) |

Kannan, R. R. R., Arumugam, R., and Anantharaman, P., 2012. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of Indian seagrasses against urinary tract pathogens. Food Chemistry, 135(4): 2470-2473. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.070 (  0) 0) |

Laabir, M., Grignon-Dubois, M., Masseret, E., Rezzonico, B., Soteras, G., Rouquette, M., et al., 2013. Algicidal effects of Zostera marina L. and Zostera noltii Hornem. extracts on the neuro-toxic bloom-forming dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella. Aquatic Botany, 111: 16-25. DOI:10.1016/j.aquabot.2013.07.010 (  0) 0) |

Leu, E., Krieger-Liszkay, A., Goussias, C., and Gross, E. M., 2002. Polyphenolic allelochemicals from the aquatic angiosperm Myriophyllum spicatum inhibit photosystem II. Plant Physiology, 130(4): 2011-2018. DOI:10.1104/pp.011593 (  0) 0) |

Li, A., Ma, J., Cao, J., and McCarron, P., 2012. Toxins in mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) associated with diarrhetic shellfish poisoning episodes in China. Toxicon, 60(3): 420-425. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.04.339 (  0) 0) |

Luo, Z., Zhang, H., Krock, B., Lu, S., Yang, W., and Gu, H., 2017. Morphology, molecular phylogeny and okadaic acid production of epibenthic Prorocentrum (Dinophyceae) species from the northern South China Sea. Algal Research, 22: 14-30. DOI:10.1016/j.algal.2016.11.020 (  0) 0) |

Morton, S. L., Faust, M. A., Fairey, E. A., and Moeller, P. D., 2002. Morphology and toxicology of Prorocentrum arabianum sp. nov., (Dinophyceae) a toxic planktonic dinoflagellate from the Gulf of Oman, Arabian Sea. Harmful Algae, 1(4): 393-400. DOI:10.1016/S1568-9883(02)00047-1 (  0) 0) |

Mulderij, G., Mau, B., de Senerpont Domis, L. N., Smolders, A. J. P., and Van Donk, E., 2009. Interaction between the macrophyte Stratiotes aloides and filamentous algae: Does it indi cate allelopathy?. Aquatic Ecology, 43(2): 305-312. DOI:10.1007/s10452-008-9194-7 (  0) 0) |

Mullin, J. B., and Riley, J. P., 1955. The spectrophotometric determination of nitrate in natural waters, with particular reference to sea-water. Analytica Chimica Acta, 12: 464-480. DOI:10.1016/S0003-2670(00)87865-4 (  0) 0) |

Murphy, J., and Riley, J. P., 1962. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta, 27: 31-36. DOI:10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88444-5 (  0) 0) |

Nakai, S., Inoue, Y., Hosomi, M., and Murakami, A., 2000. Myriophyllum spicatum-released allelopathic polyphenols inhibiting growth of blue-green algae Microcystis aeruginosa. Water Research, 34(11): 3026-3032. DOI:10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00039-7 (  0) 0) |

Nascimento, S. M., Mendes, M. C. Q., Menezes, M., Rodríguez, F., Alves-de-Souza, C., Branco, S., et al., 2017. Morphology and phylogeny of Prorocentrum caipirignum sp. nov. (Dinophyceae), a new tropical toxic benthic dinoflagellate. Harmful Algae, 70: 73-89. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2017.11.001 (  0) 0) |

Pakdel, F. M., Sim, L., Beardall, J., and Davis, J., 2013. Allelopathic inhibition of microalgae by the freshwater stonewort, Chara australis, and a submerged angiosperm, Potamogeton crispus. Aquatic Botany, 110: 24-30. DOI:10.1016/j.aquabot.2013.04.005 (  0) 0) |

Parsons, M. L., and Preskitt, L. B., 2007. A survey of epiphytic dinoflagellates from the coastal waters of the island of Hawai'i. Harmful Algae, 6(5): 658-669. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2007.01.001 (  0) 0) |

Paul, V. J., Nelson, S. G., and Sanger, H. R., 1990. Feeding preferences of adult and juvenile rabbitfish Siganus argenteus in relation to chemical defenses of tropical seaweeds. Marine Ecology Progress Series. Oldendorf, 60(1): 23-34. (  0) 0) |

Pawlik, J. R., 1993. Marine invertebrate chemical defenses. Chemical Reviews, 93(5): 1911-1922. DOI:10.1021/cr00021a012 (  0) 0) |

Platt, T., Gallegos, C. L., and Harrison, W. G., 1980. Photoinhibition of photosynthesis in natural assemblages of marine phytoplankton. Journal of Marine Research, 38(4): 687-701. (  0) 0) |

Qi, S. H., Zhang, S., Qian, P. Y., and Wang, B. G., 2008. Antifeedant, antibacterial, and antilarval compounds from the South China Sea seagrass Enhalus acoroides. Botanica Marina, 51(5): 441. DOI:10.1515/BOT.2008.054 (  0) 0) |

Rajeshwari, M., 1990. Seagrass ecosystem of Coromandel coast. Final report submitted to Department of Chemical Engineering, IIT Madras, 167pp.

(  0) 0) |

Richlen, M. L., and Lobel, P. S., 2011. Effects of depth, habitat, and water motion on the abundance and distribution of ciguatera dinoflagellates at Johnston Atoll, Pacific Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 421: 51-66. DOI:10.3354/meps08854 (  0) 0) |

Romero, J., Lee, K. S., Pérez, M., Mateo, M. A., and Alcoverro, T., 2006. Nutrient dynamics in seagrass ecosystems. In: Seagrasses: Biology, Ecology and Conservation. Larkum, A. W. D., et al., eds., Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 227-254.

(  0) 0) |

Rossi, R., Castellano, V., Scalco, E., Serpe, L., Zingone, A., and Soprano, V., 2010. New palytoxin-like molecules in Mediterranean Ostreopsis cf. ovata (dinoflagellates) and in Palythoa tuberculosa detected by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Toxicon, 56(8): 1381-1387. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.08.003 (  0) 0) |

Smayda, T. J., 1997. Harmful algal blooms: Their ecophysiology and general relevance to phytoplankton blooms in the sea. Limnology and Oceanography, 42(5part2): 1137-1153. DOI:10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1137 (  0) 0) |

Su, M., and Koike, K., 2013. A red tide off the Myanmar coast: Morphological and genetic identification of the dinoflagellate composition. Harmful Algae, 27: 149-158. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2013.05.010 (  0) 0) |

Sugahara, K., Kitamura, Y., Murata, M., Satake, M., and Tachibana, K., 2011. Prorocentrol, a polyoxy linear carbon chain compound isolated from the toxic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum hoffmannianum. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 76(9): 3131-3138. DOI:10.1021/jo102585k (  0) 0) |

Tang, Y. Z., and Gobler, C. J., 2011. The green macroalga, Ulva lactuca, inhibits the growth of seven common harmful algal bloom species via allelopathy. Harmful Algae, 10(5): 480-488. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2011.03.003 (  0) 0) |

Ten-Hage, L., Robillot, C., Turquet, J., Le Gall, F., Le Caer, J. P., Bultel, V., et al., 2002. Effects of toxic extracts and purified borbotoxins from Prorocentrum borbonicum (Dinophyceae) on vertebrate neuromuscular junctions. Toxicon, 40(2): 137-148. DOI:10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00200-8 (  0) 0) |

Tester, P. A., Kibler, S. R., Holland, W. C., Usup, G., Vandersea, M. W., Leaw, C. P., et al., 2014. Sampling harmful benthic dinoflagellates: Comparison of artificial and natural substrate methods. Harmful Algae, 39: 8-25. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2014.06.009 (  0) 0) |

Thomas, L. C., Nandan, S. B., and Padmakumar, K. B., 2021. First report on an unusual bloom of the potentially toxic epibenthic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum rhathymum from Bangaram Lagoon of the Lakshadweep archipelago: Arabian Sea. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 41: 101549. DOI:10.1016/j.rsma.2020.101549 (  0) 0) |

Torigoe, K., Murata, M., Yasumoto, T., and Iwashita, T., 1988. Prorocentrolide, a toxic nitrogenous macrocycle from a marine dinoflagellate, Prorocentrum lima. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 110(23): 7876-7877. DOI:10.1021/ja00231a048 (  0) 0) |

Totti, C., Accoroni, S., Cerino, F., Cucchiari, E., and Romagnoli, T., 2010. Ostreopsis ovata bloom along the Conero Riviera (northern Adriatic Sea): Relationships with environmental conditions and substrata. Harmful Algae, 9(2): 233-239. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2009.10.006 (  0) 0) |

Tubaro, A., Florio, C., Luxich, E., Sosa, S., Loggia, R. D., and Yasumoto, T., 1996. A protein phosphatase 2A inhibition assay for a fast and sensitive assessment of okadaic acid contamination in mussels. Toxicon, 34(7): 743-752. DOI:10.1016/0041-0101(96)00027-X (  0) 0) |

Turkoglu, M., 2016. First harmful algal bloom record of tyco-planktonic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima (Ehrenberg) F. Stein, 1878 in the Dardanelles (Turkish Straits System, Turkey). Journal of Coastal Life Medicine, 4(10): 765-774. DOI:10.12980/jclm.4.2016J6-184 (  0) 0) |

Vale, P., and Sampayo, M. A. D. M., 2002. First confirmation of human diarrhoeic poisonings by okadaic acid esters after ingestion of razor clams (Solen marginatus) and green crabs (Carcinus maenas) in Aveiro lagoon, Portugal and detection of okadaic acid esters in phytoplankton. Toxicon, 40(7): 989-996. DOI:10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00095-8 (  0) 0) |

Vanderstukken, M., Mazzeo, N., Colen, W. V., Declerck, S. A. J., and Muylaert, K., 2011. Biological control of phytoplankton by the subtropical submerged macrophytes Egeria densa and Potamogeton illinoensis: A mesocosm study. Freshwater Biology, 56(9): 1837-1849. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2011.02624.x (  0) 0) |

Willis, R. J., 1985. The historical bases of the concept of allelopathy. Journal of the History of Biology, 18(1): 71-102. DOI:10.1007/BF00127958 (  0) 0) |

Wu, C., Chang, X. X., Dong, H. J., Li, D. F., and Liu, J. Y., 2008. Allelopathic inhibitory effect of Myriophyllum aquaticum (Vell.) Verdc. on Microcystis aeruginosa and its physiological mechanism. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 28(6): 2595-2603. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2032(08)60061-X (  0) 0) |

Yang, D., and Yang, C., 2009. Detection of seagrass distribution changes from 1991 to 2006 in Xincun Bay, Hainan, with satellite remote sensing. Sensors, 9: 830-844. DOI:10.3390/s90200830 (  0) 0) |

Yasumoto, T., Seino, N., Murakami, Y., and Murata, M., 1987. Toxins produced by benthic dinoflagelltes. The Biological Bulletin, 172(1): 128-131. DOI:10.2307/1541612 (  0) 0) |

Yu, Z. Q., Deng, H., Wu, K. W., Du, J., and Ma, M., 2012. Nutrient contents of dominant seagrass species and their affecting factors in Hainan Province. Journal of East China Normal University (Natural Science), (4): 131-141. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-5641.2012.04.016 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, J., Liu, B., Wang, J., Gao, Y., and Wu, Z., 2010. Study on the mechanism of allelopathic influence on cyanobacteria and chlorophytes by submerged macrophyte (Myriophyllum spicatum) and its secretion. Aquatic Toxicology, 98(2): 196-203. DOI:10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.02.011 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, J., Xiao, H., Chen, Q., Zhao, M., Sun, D., and Duan, S., 2019. Growth inhibition of Phaeocystis globosa induced by luteolin-7-O-glucuronide from seagrass Enhalus acoroides. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14): 2615. DOI:10.3390/ijerph16142615 (  0) 0) |

Zou, J., Li, Q., Lu, S., Dong, Y., Chen, H., Zheng, C., et al., 2020. The first benthic harmful dinoflagellate bloom in China: Morphology and toxicology of Prorocentrum concavum. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 158: 111313. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111313 (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21