Goatfishes are tropical marine perciform fish belonging to the family Mullidae, including more than 60 species (Uiblein, 2007). The rosy goatfish Parupeneus rubescens is considered one of the essential goatfish species in the Arabian Gulf used as seafood at fish markets in Saudi Arabia. Despite its economic and ecologic importance, the ichthyoparasitological problems related to Parupeneus rubescens are in general scarce for this region, particularly those associated with parasitic copepods that may affect them. Some research projects have focused on copepod parasites of goatfishes (Izawa, 1976; Dojiri and Cressey, 1987; Ho et al., 1999; Ho and Lin, 2007; Anh Tuan et al., 2015; Paschoal et al., 2016; Cardoso et al., 2017; Soler-Jiménez et al., 2019; Abdel-Gaber et al., 2020a, b, c). Taeniacanthidae Wilson, 1911 is a unique copepod family within the order Poecilostomatoida with either parasitic members on marine fish or associated with sea urchins (Dojiri and Humes, 1982; Boxshall and Halsey, 2004). Taeniacanthids exhibit a high degree of host specificity at both the generic and specific levels (Boxshall and Halsey, 2004). Copepods of the genus Irodes are usually parasitic on the gills, nostrils, and branchial cavities of their fish hosts (Dojiri and Cressy, 1987; Ho and Lin, 2007). Irodes was proposed by Wilson (1911) and established as its type-species Ⅰ. gracilis, which was formerly known as Bomolochus gracilis Heller, 1865. However, due to his inclusion of other species of Bomolochus von Nordmann, 1832, which created confusion in diagnosing the newly erected genus, Ho (1969) rejected Irodes. This decision was followed by Kabata (1979), Balarman (1983), and Pillai (1985). Nevertheless, due to the discovery of four other taeniacanthids that share certain derived character states with B. gracilis, Dojiri and Cressey (1987) resurrected the genus Irodes and redefined it accordingly.

The identification and classification of copepods are fundamentally based on their morphological and anatomical features (Huys and Boxshall, 1991; Ho, 2001; Boxshall and Halsey, 2004), which is very limited due to the relatively low number of the copepodologists (Hamza et al., 2007; Ramdane, 2009). Therefore, to complement the study of the phylogenetic relationships among copepod families based on the morphological characters, a different approach employing molecular data is necessary (Ferrari and von Vaupel Klein, 2019). Many other genetic markers complement those conventional approaches (Baek et al., 2016). Among various molecular markers, phylogenetic studies based on the 18S rRNA gene sequences have proven to be useful for investigating the evolutionary history of the crustaceans (Graybeal, 1994) and other metazoans (Aguinaldo et al., 1997). The versatile systematic utility of 18S rRNA gene is due to different evolutionary rates among different regions of the gene (Mindell and Honeycutt, 1990) in conjunction with a large size and a conserved function (Olsen and Woese, 1993). Due to such advantages, 18S rRNA gene sequence help to assess the phylogenetic relationships among copepod families containing highly modified morphological characters. Huys et al. (2007) found that nuclear ribosomal genes of 18S and 28S rRNA include semi-conserved domains that intersperse with divergent regions, allowing for a wide range of taxonomic levels in phylogenetic reconstruction. Few mitochondrial genomes of copepods have been published so far (Wang et al., 2011; Easton et al., 2014), although others claim that copepod mitochondrial genomes retained pancrustacean features and maintained calanoid-specific patterns (Kim et al., 2013), or adapted to harsh environments by mitogenome rearrangements (Cameron et al., 2007; Ki et al., 2009).

There is, however, little information on the copepods in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, this study was designed to provide the first report for the parasite Irodes parupenei Ho and Lin, 2007 in Parupeneus rubescens inhabiting Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. The copepod species was identified and characterized through morphological and molecular analyses.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Fish CollectionA total of 80 specimens of the rosy goatfish, Parupeneus rubescens (Family: Mullidae), were randomly collected during the period of January–October 2020 from the Arabian Gulf, Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. They were transported to Parasitology Research Laboratory at the Zoology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Fish were thoroughly tested for parasitic species, according to the technique proposed by Ravichandran et al. (2007).

2.2 Parasitological StudiesRecovered parasites were carefully removed from the gill region of infected fish under a stereo-dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ18, NIS ELEMENTS software), washed in a sterile 0.9% saline solution, and preserved for further detailed examination in 70% ethanol. The preserved samples were cleared for 24 h with lactophenol, then the different body parts and appendages were examined. All drawings were made with the aid of a camera lucida. Using Olympus ocular micrometer, the different body parts of the selected copepods were measured. The average values with the range were given in parentheses. Morphological terminology follows the guidelines of El-Rashidy and Boxshall (2014). Sewell's style (1949) was adopted for the armature formula of the swimming legs, in which the spines and setae are denoted by Roman and Arabic numerals, respectively.

2.3 Molecular Analysis 2.3.1 DNA extraction and Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)The genomic DNA was extracted from the preserved copepod samples using DNeasy tissue kit© (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the recommended protocol. The quality and purity of DNA were quantified with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The 18S rRNA gene was targeted and amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and subsequently sequenced. PCR amplification was carried out using the same protocol and primers of the previous study of Huys et al. (2012). PCR amplicons were visualized on 1.5% TBE agarose gel stained with SYBR Safe DNA gel stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada) by UV transilluminator.

2.3.2 Sequence alignment and Phylogenetic analysisThe amplicons were sequenced bidirectionally with ABI PRISM 310TM DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), then were analyzed using BLASTn, and aligned using ClustalW multiple alignments (Thompson et al., 1994) implemented in BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor ver. 5.0.9 (Hall, 1999). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the method of Maximum Parsimony (MP) focused on uniform rates among sites of the Tamura-Nei model (Tamura and Nei, 1993) on Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016). This analysis was performed using a heuristic search strategy of Nearest-Neighbor-Interchange (NNI) with random addition sequences followed by tree-bisection reconnection branch-swapping (TBR) with 1000 bootstrap replicates (Felsenstein, 1985) under appropriate substitution Nucleotide models.

3 ResultsTwelve out of eighty (15%) specimens of the examined rosy goatfish, Parupeneus rubescens, were naturally infected by a female copepod parasite known as Irodes parupenei Ho and Lin, 2007 in the gills region.

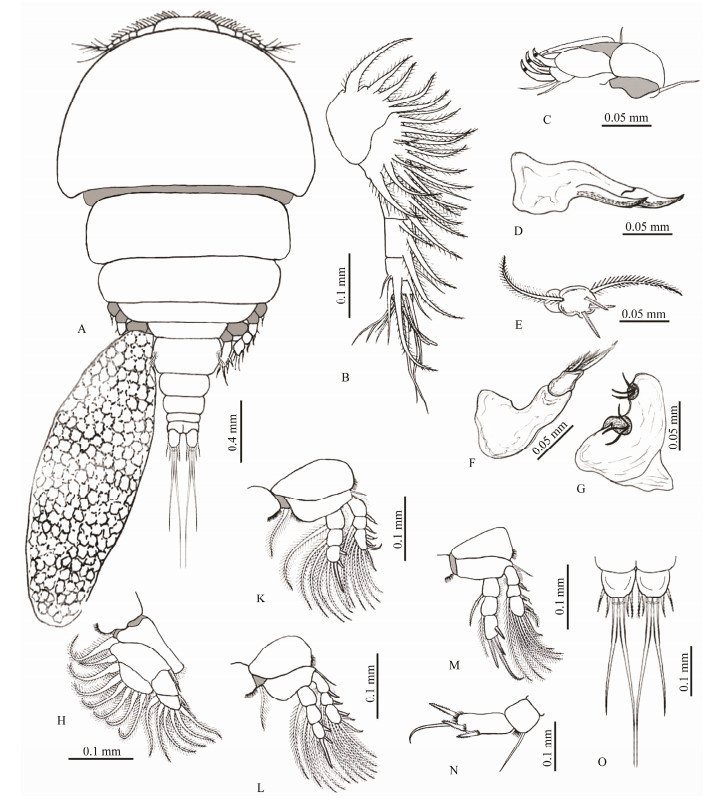

3.1 Microscopic Examination 3.1.1 Adult females (Fig.1)

|

Fig. 1 Irodes parupenei. A, the whole body of an adult female; B, antennule; C, antenna; D, mandible; E, maxillue; F, maxilla; G, maxilliped; H, leg 1; K, leg 2; L, leg 3; M, leg 4; N, leg 5; O, caudal rami. |

Body flattened. Prosome longer than Urosome, comprising of broad cephalothorax of about 40% of the total body length and four well-separated pedigers that distinctly broad. Urosome comprising of genital somite and four free abdominal somites without ornamentation. Genital somite with convex lateral margins bearing three long setae. Caudal ramus provided with six setae (four short and two long). Eggsac oblong with large eggs.

3.1.2 DimensionsBody length 1.81 (1.58–2.1) (excluding setae on caudal rami); cephalothorax 0.58 (0.56–0.63) × 0.75 (0.71–0.78); urosome length 0.45 (0.39–0.49); genital somite wider than long 0.163 (0.150–0.172) × 0.236 (0.197–0.243); four abdominal somites 0.092 (0.089–0.095) × 0.140 (0.132–0.145), 0.085 (0.080–0.089) × 0.134 (0.127–0.137), 0.080 (0.075–0.082) × 0.107 (0.097–0.111), and 0.055 (0.046–0.059) × 0.113 (0.110–0.118), respectively, from anterior to posterior; caudal rami length 0.070 (0.065–0.078), width 0.037 (0.031–0.039); and egg sac 0.632 (0.618–0.651) × 0.341 (0.335–0.367).

3.1.3 DescriptionRostral area broadly protruded anteriorly on the apex of the cephalothorax. First antenna (antennule) 6-segmented, with an armature formula of 20, 4, 3, 4, 2 + 1 aesthetasc, and 7 + 1 aesthetasc. Second antenna (antenna) uniramous, 4-segmented, proximal segment (coxobasis) largest and carrying one seta, then strongly flexed outwardly at the junction between the second and third segment. The second one carries a simple seta and the third one has one process and one curved claw, while the terminal segment consists of two claws and four setae. Mandible with two blades of serrate anterior edge. First maxilla (maxillule) lobate with five setae. Second maxilla (maxilla) 2-segmented, and the distal segment provided with three spines. Maxilliped 2-segmented with distal one carrying six setae. Legs 1–4 biramous, Leg 1 with 2-segmented exopod and endopod. Legs 2–4 with 3-segmented exopod and endopod. Armature formulae of legs 1–4 as:

Leg 1: exopod Ⅰ-0; 0–9 endopod 0–1; 0–7

Leg 2: exopod Ⅰ-0; Ⅰ-1; Ⅲ, Ⅰ, 5 endopod 0–1; 0–2; Ⅱ, Ⅰ, 3

Leg 3: exopod Ⅰ-0; Ⅰ-1; Ⅱ, Ⅰ, 5 endopod 0–1; 0–2; Ⅱ, 1, 2

Leg 4: exopod Ⅰ-0; Ⅰ-1; Ⅱ, Ⅰ, 5 endopod 0–1; 0–1; Ⅰ, Ⅲ

Leg 5 segmented in two; the proximal segment with one seta, and the distal segment with three spines and one seta. Leg 6 with three setae located in the area of the egg sac attachment area.

3.1.4 Adult malesAdult males were not observed in this study.

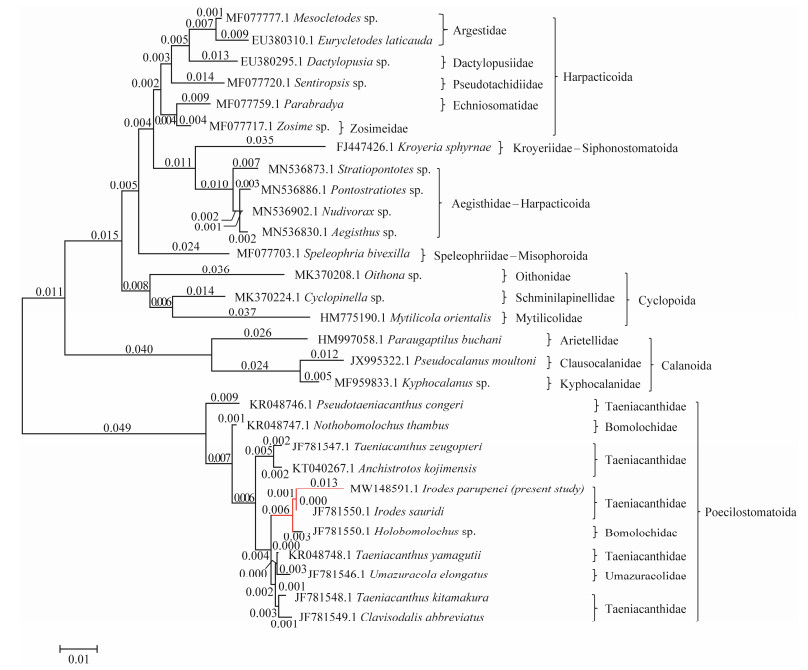

3.2 Molecular AnalysisA total of 1442 bp with 49.4% GC content was evaluated and deposited in GenBank under the accession number MW148591.1 for the 18S rRNA gene of the existing taeniacanthid Copepoda species. Phylogenetic analysis was performed by aligning the partial and complete sequences of the 18S rRNA gene with 29 taxa representing six copepod orders using a maximum likelihood method (Table 1, Fig.2).

|

|

Table 1 Copepoda species used in the phylogenetic analysis of Irodes parupenei for their corresponding 18S rRNA gene region |

|

Fig. 2 Molecular phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−5881.50) is shown. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach and then selecting the topology with a superior log-likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site (next to the branches). |

The results showed that the 18S rRNA gene sequences of this taeniacanthid species revealed 90.12%–91.18% identity with Harpacticoida, 89.21% with Siphonostomatoida, 89.92% with Misophrioida, 90.21%–90.95% with Cyclopoida, 87.51%–87.85% with Calanoida, and 96.38%–98.75% with Poecilostomatoida (Table 1). Among Poecilostomatoida, the present species bears 96.38%–98.75% similarity with taxa of Taenicanthidae, 97.36%–98.34% with Bomolochidae, and 97.78% with Umazuracolidae.

Among Poecilostomatoida, the maximum identity (98.75%) with the lowest divergent value was recorded between the present taeniacanthid species and Irodes sauridi (gb| JF 781550.1), followed by Taeniacanthus yamaguti (97.92%, gb| KR048748.1), Taeniacanthus kitamakura (97.78%, gb| JF781548.1), Clavisodalis abbreviates (97.71%, gb| JF78 1549.1), Taeniacanthus zeugopteri (97.23%, gb| JF7815 47.1), Anchistrotos kojimensis (97.16%, gb| KT030267.1), and Pseudotaeniacanthus congeri (96.38%, KR048746.1) (Table 1). The overall mean distance between the studied species and other taeniacanthids was 0.02.

The ME tree showed that the cluster containing all of the copepod species was divided into two separate and distinct clades (Fig.2). The first clade contains some copepod species belonging to Harpacticoida (representing by Argestidae, Dactylopusiidae, Pseudotachidiidae, Ectinosomatidae, Zosimeidae, and Aegisthidae), Siphonostomatoida (represented by Kroyeriidae), Misophrioida (represented by Speleophriidae), Oithonidae, Schminlapinellidae, and Mytilicolidae of the order Cyclopoida, and Calanoida (represented by Arietellidae, Clausocalanidae, and Kyphocalanidae). The second clade comprises the other copepod species belonging to the Taeniacanthidae, Bomolochidae, and Umazuracolidae families of the order Poecilostomatoida. The ME tree revealed the studied species is closely related to Irodes sauridi (gb| JF781550.1) in the same taxon.

4 DiscussionParasitic copepods utilize an extraordinary range of hosts, occurring on virtually every available phylum in the marine environment (Boxshall and Halsey, 2004). Little information is known about the parasitic fish copepods in the Arabian Gulf (Ho, 2001; Hamza et al., 2007; Ramdane, 2009; Abdel-Gaber et al., 2020a, c). Thus, the current study focused on investigating copepod parasites infecting the goatfish Parupeneus rubescens (Mullidae) from the coasts of the Arabian Gulf in Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. Members of the Irodes genus have high host specificity to various goatfish species that inhabited different geographical locations of India, Kenya, Kuwait, China, and Vietnam (Uma Devi and Shyamasundari, 1980; Dojiri and Cressey, 1987; Ho and Lin, 2007).

The taeniacanthid copepods species described herein agree with the previous illustrations of Irodes parupenei given by Ho and Lin (2007) from the marine goatfish' nostrils Parupeneus spilurus and P. multifasciatus landed at Ma-gong Fishing Port in Penghu County of Taiwan, China by their external morphology and host preferences. It differs from the previously described species in the type of host species and its geographical distribution. This study indicates that those species are synonymous.

The current Irodes species can be differentiated from the other congeners of the Irodes genus with the most related host species, such as Irodes upenei Yamaguti, 1954 isolated from the gills of Parupeneus indicus, Parupeneus macronema, Parupeneus cyclostomus, and Parupeneus barleenius, in the presence of nine elements on the terminal exopodal segment for the second leg (vs. eight in Ⅰ. upenei), the presence of three spines and one setae on the distal segment of the fifth leg (vs. four short setae in Ⅰ. upenei), and the anal segment without ornamentation (vs. the short row of spinules near insertion of each caudal ramus in Ⅰ. upenei); and differed from Ⅰ. sauridi Pillai, 1963 collected from Parupeneus cyclostomus and Upeneus vittatus by having minute outermost spine of terminal endopod segment of leg 4 (vs. conspicuous in Ⅰ. parupenei), and the ventral surface of the anal segment with four rows of spinules in the anterior portion and a row of spinules near insertion of each caudal ramus (vs. absent in Ⅰ. parupenei).

In addition, there are some differences between the present Irodes species and the other congeners infecting different host types, such as Ⅰ. remipes Dojiri and Cressey (1987) collected from Plotosus lineatus and Cnidoglanis macrocephalus by the presence of two sclerotized ridges forming V-shaped structure in the rostral area (vs. absent in Ⅰ. parupenei), the second segment of antennule with 5 spines (vs. 4 in Ⅰ. parupenei), the appearance of strongly curved spine (resembling hooks) of the second segment and outermost spine of third exopodal segment of leg 3 (vs. not curved in Ⅰ. parupenei), almost equal width of thoracic segments bearing legs 2 and 3 (vs. distinct varying size in Ⅰ. parupenei), and the presence of a single row of minute spinules near insertion of each caudal ramus (vs. unornamented in Ⅰ. parupenei); from Ⅰ. anguillaris Uma Devi and Shyamasundari (1980) infected Plotosous anguillaris by having three-segmented antenna with four spiniform setae and one slender setae (vs. that observed in Ⅰ. parupenei); from Ⅰ. callionymi Yamaguti, 1939 in the presence of 4-segmented abdomen (vs. 3-segments in Ⅰ. callionymi), and the presence of nine setae in the terminal exopodal segment of leg 1 (vs. 7 in Ⅰ. callionymi); from Irodes gracilis Heller, 1865 that isolated from Sphyrna zygaena, S. tiburo, S. lewini, S. diplana, Carcharhinus maculipinnis, Rhynchobatus djiddensis, Carcharhinus leucas, Rhizoprionodon acutus, and Chiloscyllium indicum; by having two small rounded processes at antero-ventral region and a large bifid sclerotized part bearing transverse shelf-like protuberance (vs. absent in Ⅰ. parupenei), and the presence of 5 spines on the second segment of antennule (vs. 4 in Ⅰ. parupenei).

Until now, all valid species of Irodes can be identified from their congeners using the generic features in the available key of Ho et al. (1999). However, most Irodes species are challenging to identify because of the morphological similarities and the lack of detailed descriptions. Thus more detailed researches on both morphological and molecular analyses are needed for accurate identification. Copepods are exceptional arthropods because, with only a few complete mitogenomes published, they already present many deviations from the reference gene order (Feng et al., 2016; Su et al., 2016). The current study focused on the genetic marker 18S rRNA for precise identification of the recovered taeniacanthid species, which is consistent with Dippenaar (2009), Huys et al. (2009), Song et al. (2009), and Cepeda et al. (2012). The results indicated that the analysis of the DNA sequence for the target genes offers invaluable information on the taxonomic position of copepod species.

According to Huys et al. (2002) and Ho et al. (2003), copepods are classified into three infraorders, Progymnoplea Lang, 1948, Gymnoplea Giesbrecht, 1892, and Podoplea Giesbrecht, 1892. The current dendrogram was split into two clades representing copepod species by the last two infraorders of Gymnoplea and Podoplea. Herein, the basal taxon of Misophrioida and Calanoida in Neocopepods was observed. In addition to being a sister-group to the members of Podoplea, these results agreed with the previous data of Ho (1990), Huys and Boxshall (1991), Ho (1994), Ho et al. (2003), Blanco-Bercial et al. (2011), and Huys et al. (2012) indicating that these orders are the most primitive ones within Neocopepoda and Podoplea.

Previously, Dahms (2004), Jenner (2009), and Schizas et al. (2015) reported that the taxa of copepods within the Podoplea infraorder diversified into two clades: MHPSM-clade including Monstrilloida, Harpacticoida, Poecilostomatoida, Siphonostomatoida, Mormonilloida; and MCG-clade was including Misophrioida, Cyclopoida, and Gelyelloida. The current phylogeny represented those two clades and Monstrilloida, Mormonilloida, and Gelyelloida were not considered. Additionally, Walter and Boxshall (2019) reported that Poecilostomatoida comprises more than sixty families. Our molecular study provided nodal support for the monophyly of the bomolochiform complex. In 1987, Dojiri and Cressey mentioned the phylogenetic relationship within the bomolochiform complex consists of three closely related families including Bomolochidae, Taenicanthidae, and Tuccidae, while there is a close relationship between the former two families. Huys et al. (2012) assumed that Umazuracolidae belongs to this group of families. Herein, Umazuracolidae is related to the fish-parasitizing families of Bomolochidae and Taeniacanthidae that referred to a close similarity in the morphology of the antenna and mouthparts as mentioned by Dojiri and Cressey (1987).

There is a sister-group of the Bomolochidae + Taeniacanthidae in the current study, which agreed with Kabata (1979), Dojiri and Humes (1982), and Humes and Dojiri (1984). Both of these families have a mosaic of plesiomorphic and apomorphic characters based on the setation of the first antenna, the structure and shape of the rostral area, the antenna of the female specimens, the structure of prosome, the location and shape of maxilliped, and the spinulation of legs 2–4. In the present study, the monophyly of Taeniacanthidae was not supported by strict consensus due to the Irodes species that appeared to be closely related to Holobomolochus sp., which is consistent with the observation of Huys et al. (2012). Herein, Taeniacanthidae includes five genera, Pseudotaeniacanthus, Taeniacanthus, Anchistrotos, Clavisodalis, and Irodes. By comparing the 18S rRNA gene query, the current copepod parasite was detected to be a distinct species related closely to Irodes sauridi (JF781550.1).

It can be concluded that the present study provided valuable information about a taeniacanthid copepod species Irodes parupenei Ho and Lin, 2007, which can infect rosy goatfish Parupeneus rubescens. Future studies on the functions of other genes are necessary to understand better about this species.

AcknowledgementThis study was supported by the Researchers Supporting Project of King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (No. RSP-2021/25).

Abdel-Gaber, R., Alghamdi, M., Abu Hawsah, M., Ali, S., and Yehia, R. S.. 2020a. Light and scanning electron microscopic studies of Lepeophtheirus salmonis (Siphonostomatoida: Caligidae) infecting the rosy goatfish Parupeneus rubescens. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 12(2): 282-287. (  0) 0) |

Abdel-Gaber, R., Al-Quraishy, S., Dkhil, M. A., Alghamdi, M., Alghamdi, J., and Kadry, M.. 2020b. Morphology and phylogeny of Taeniacanthus yamagutii Shiino, 1956 (Hexanauplia: Taeniacanthidae), a copepod infecting the gills of rosy goatfish Parupeneus rubescens (Mullidae) in the Arabian Gulf. Journal of Ocean University of China, 19: 1409-1420. DOI:10.1007/s11802-020-4474-5 (  0) 0) |

Abdel-Gaber, R., Al-Quraishy, S., Dkhil, M. A., Elamin, M., and Alghamdi, M.. 2020c. Morphological analysis of Caligus elongatus von Nordmann, 1832 (Copepoda: Caligidae) from the rosy goatfish Parupeneus rubescens (Mullidae). Microscopy Research and Technique, 83(11): 1369-1380. DOI:10.1002/jemt.23528 (  0) 0) |

Aguinaldo, A. M., Turbeville, J. M., Linford, L. S., Rivera, M. C., Garey, J. R., Raff, R. A., et al.. 1997. Evidence for a clade of nematodes, arthropods, and other moulting animals. Nature, 387: 489-493. DOI:10.1038/387489a0 (  0) 0) |

Anh Tuan, D. N., Sang, T. Q., and Binh, D. T.. 2015. Parasites of goatfishes (Parupeneus spp. ) in Khanh Hoa Province, Vietnam, preliminary results. Journal of Fisheries Science and Technology, 2015(Special issue): 10-15. (  0) 0) |

Baek, S. Y., Jang, K. H., Choi, E. H., Ryu, S. H., Kim, S. K., Lee, J. H., et al.. 2016. DNA barcoding of metazoan zooplankton copepods from South Korea. PLoS One, 11(7): e0157307. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0157307 (  0) 0) |

Balarman, S., 1983. Discussion on the validity of the genera of Taeniacanthidae (Crustacea, Copepoda). In: Selected Papers on Crustacea. Rabindranath, P., ed., The Aquarium, Trivandrum, 207pp.

(  0) 0) |

Blanco-Bercial, L., Bradford-Grieve, J., and Bucklin, A.. 2011. Molecular phylogeny of the Calanoida (Crustacea: Copepoda). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 59: 103-113. DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.01.008 (  0) 0) |

Boxshall, G. A., and Halsey, S. H., 2004. An Introduction to Copepod Diversity. Part Ⅱ. The Ray Society, London, 966pp.

(  0) 0) |

Cameron, S. L., Johnson, K. P., and Whiting, M. F.. 2007. The mitochondrial genome of the screamer louse Bothriometopus (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera): Effects of extensive gene rearrangements on the evolution of the genome. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 65: 589-604. DOI:10.1007/s00239-007-9042-8 (  0) 0) |

Cardoso, L., Martins, M. L., Cadorin, D. I., Bonfim, C. N. C., and de Oliveira, R. L. M.. 2017. First record of Hamaticolax scutigerulus (Copepoda: Bomolochidae) in Brazil, ectoparasite of the spotted goatfish Pseudoupeneus maculatus (Actinopterygii: Mullidae). Acta Scientiarum Biological Sciences, 39(2): 251-258. DOI:10.4025/actascibiolsci.v39i2.34100 (  0) 0) |

Cepeda, G. D., Blanco-Bercial, L., Bucklin, A., Berón, C. M., and Viñas, M. D.. 2012. Molecular systematic of three species of Oithona (Copepoda, Cyclopoida) from the Atlantic Ocean: Comparative analysis using 28S rDNA. PLoS One, 7(4): e35861. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0035861 (  0) 0) |

Dahms, H. U.. 2004. Exclusion of the Polyarthra from Harpacticoid and its reallocation as an underived branch of the Copepoda (Arthropoda, Crustacea). Invertebrate Zoology, 1(1): 29-51. DOI:10.15298/invertzool.01.1.03 (  0) 0) |

Dippenaar, S. M.. 2009. Estimated molecular phylogenetic relationships of six siphonostomatoid families (Copepoda) symbiotic on elasmobranchs. Crustaceana, 82: 1547-1567. DOI:10.1163/001121609X12511103974538 (  0) 0) |

Dojiri, M., and Cressey, R. F.. 1987. Revision of the Taeniacanthidae (Copepoda: Poecilostomatoida) parasitic on fishes and sea urchins. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology, 447: 1-250. (  0) 0) |

Dojiri, M., and Humes, A. G.. 1982. Copepods (Poecilostomata: Taeniacanthidae) from sea urchins (Echinoidea) in the Southwest Pacific. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 74: 381-436. DOI:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1982.tb01159.x (  0) 0) |

Easton, E. E., Darrow, E. M., Spears, T., and Thistle, D.. 2014. The mitochondrial genomes of Amphiascoides atopus and Schizopera knabeni (Harpacticoida: Miraciidae) reveal similarities between the copepod orders Harpacticoida and Poecilostomatoida. Gene, 538: 123-137. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2013.12.053 (  0) 0) |

El-Rashidy, H. H., and Boxshall, G. A.. 2014. A new parasitic copepod (Cyclopoida: Bomolochidae) from a ponyfish (Leiognathidae) caught in Egyptian Mediterranean waters, with a review of hosts and key to species of Nothobomolochus. Systematic Parasitology, 87: 111-126. DOI:10.1007/s11230-013-9462-3 (  0) 0) |

Felsenstein, J.. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution, 39: 783-791. DOI:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x (  0) 0) |

Feng, H., Wang, L. X., Huang, J., Jiang, J., Tang, D., Fang, R., et al.. 2016. Complete mitochondrial genome of Sinergasilus polycolpus (Copepoda: Poecilostomatoida). Mitochondrial DNA Part A, 27: 2960-2962. DOI:10.3109/19401736.2015.1060460 (  0) 0) |

Ferrari, F. D., and von Vaupel Klein, J. C.. 2019. Rhabdomoplea, a new superorder for the thaumatopsylloid copepods: The consequence of an alternative hypothesis of copepod phylogeny. Crustaceana, 92: 177-188. DOI:10.1163/15685403-00003850 (  0) 0) |

Giesbrecht, W.. 1892. Systematik und Faunistik der pelagischen Copepoden des Golfes von Neapel. Fauna und Flora des Golfes von Neapel, 19: 1-831. (  0) 0) |

Graybeal, A.. 1994. Evaluating the phylogenetic utility of genes–A search for genes informative about deep divergences among vertebrates. Systematic Biology, 43: 174-193. DOI:10.1093/sysbio/43.2.174 (  0) 0) |

Hall, T. A.. 1999. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, 41: 95-98. (  0) 0) |

Hamza, F., Boxshall, G., and Kechemir-Issad, N.. 2007. A new species of Prohatschekia Nune-Ruivo, 1954 (Copepoda: Hatschekiidae) parasitic on Scorpaena elongata (Cadenat) of Algeria. Systematic Parasitology, 67: 119-124. DOI:10.1007/s11230-006-9076-0 (  0) 0) |

Heller, C., 1865. Crustaceen. In: Reise der Osterreichischen Fregatte Novara urn die Erde in der Jahren 1857, 1858, 1859 unter den Befehlen des Commodore B. von Wullerstorf-Urbair, Zoologischen Theil. Karl Gerold's Sohn Wien, Vienna, 388 (in German).

(  0) 0) |

Ho, J. S.. 1969. Copepods of the family Taeniacanthidae (Cyclopoida) parasitic on fishes in the Gulf of Mexico. Bulletin of Marine Science, 19: 111-130. (  0) 0) |

Ho, J. S.. 1990. Phylogenetic analysis of copepod orders. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 10: 528-536. DOI:10.1163/193724090X00410 (  0) 0) |

Ho, J. S.. 1994. Copepod phylogeny: A reconsideration of Huys & Boxshall's 'parsimony versus homology'. Hydrobiologia, 292(293): 31-39. (  0) 0) |

Ho, J. S.. 2001. Why do symbiotic copepods matter?. Hydrobiologia, 453/454: 1-7. DOI:10.1023/A:1013139212227 (  0) 0) |

Ho, J. S., and Lin, C. L.. 2007. Two new species of taeniacanthid copepods (Poecilostomatoida) parasitic on marine fishes of Taiwan. Systematic Parasitology, 67: 73-80. DOI:10.1007/s11230-006-9073-3 (  0) 0) |

Ho, J. S., Dojiri, M., Gordon, H., and Deets, G. B.. 2003. A new species of Copepoda (Thaumatopsyllidae) symbiotic with a brittle star from California, USA, and designation of a new order Thaumatopsylloida. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 23: 582-594. DOI:10.1651/C-2391 (  0) 0) |

Ho, J. S., Kim, Ⅰ. H., and Sey, O.. 1999. New species of Irodes (Copepoda, Taeniacanthidae) parasitic on the goatfish from Kuwait, with a key to the species of Irodes. Pakistan Journal of Marine Sciences, 8: 123-129. (  0) 0) |

Humes, A. G., and Dojiri, M.. 1984. Current concepts of taeniacanthid copepods associated with Echinoidea. Crustaceana, 7: 258-266. (  0) 0) |

Huys, R., and Boxshall, G. A., 1991. Copepod Evolution. The Ray Society, London, 468pp.

(  0) 0) |

Huys, R., Fatih, F., Ohtsuka, S., and Llewellyn-Hughes, J.. 2012. Evolution of the bomolochiform superfamily complex (Copepoda: Cyclopoida): New insights from ssrDNA and morphology, and origin of umazuracolids from polychaete-infesting ancestors rejected. International Journal for Parasitology, 42: 71-92. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.10.009 (  0) 0) |

Huys, R., Llewellyn-Hughes, J., Conroy-Dalton, S., Olson, P. D., Spinks, J. N., and Johnston, D. A.. 2007. Extraordinary host switching in siphonostomatoid copepods and the demise of the Monstrilloida: Integrating molecular data, ontogeny and antennulary morphology. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 43: 368-378. DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.004 (  0) 0) |

Huys, R., Lopez-Gonzalez, P. J., Roldan, E., and Luque, A. A.. 2002. Brooding in cocculiniform limpets (Gastropoda) and familial distinctiveness of the Nucellicolidae (Copepoda): Misconceptions reviewed from a chitonophilid perspective. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 75(2): 187-217. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2002.tb01422.x (  0) 0) |

Huys, R., MacKenzie-Dodds, J., and Llewellyn-Hughes, J.. 2009. Cancrincolidae (Copepoda, Harpacticoida) associated with land crabs: A semiterrestrial leaf of the ameirid tree. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 51: 143-156. DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.12.007 (  0) 0) |

Izawa, K.. 1976. A new parasitic copepod, Tegobomologus nasicola gen. et sp. nov. (Cyclopoida: Bomolochidae), from a Japanese goatfish. Publs Seto Marine Biological Laboratory, 23: 289-298. DOI:10.5134/175934 (  0) 0) |

Jenner, R. A.. 2009. Higher-level crustacean phylogeny: Consensus and conflicting hypotheses. Arthropod Structure and Development, 39(2): 143-153. (  0) 0) |

Kabata, Z., 1979. Parasitic Copepoda of British Fishes. The Ray Society, London, 468pp.

(  0) 0) |

Ki, J. S., Park, H. G., and Lee, J. S.. 2009. The complete mitochondrial genome of the cyclopoid copepod Paracyclopina nana: A highly divergent genome with novel gene order and atypical gene numbers. Gene, 435: 13-22. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2009.01.005 (  0) 0) |

Kim, S., Lim, B. J., Min, G. S., and Choi, H. G.. 2013. The complete mitochondrial genome of Arctic Calanus hyperboreus (Copepoda, Calanoida) reveals characteristic patterns in calanoid mitochondrial genome. Gene, 520: 64-72. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2012.09.059 (  0) 0) |

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K.. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7. 0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 33: 1870-1874. (  0) 0) |

Lang, K.. 1948. Copepoda 'Notodelphyoida' from the Swedish west-coast with an outline on the systematics of the Copepods. Arkiv fö r Zoologi, 40(14): 1-36. (  0) 0) |

Mindell, D., and Honeycutt, R. L.. 1990. Ribosomal RNA in vertebrates: Evolution and phylogenetic applications. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 21: 541-566. DOI:10.1146/annurev.es.21.110190.002545 (  0) 0) |

Olsen, G. J., and Woese, C. R.. 1993. Ribosomal RNA: A key to phylogeny. FASEB J, 7: 113-123. DOI:10.1096/fasebj.7.1.8422957 (  0) 0) |

Paschoal, F., Pereira, A. N., and Luque, J. L.. 2016. Colobomatus kimi sp. nov. (Copepoda: Philichthyidae) parasitic in the dwarf goatfish Upeneus parvus Poey, 1852 (Perciformes: Mullidae) in the South Atlantic Ocean. Zootaxa, 4174(1): 176-191. DOI:10.11646/zootaxa.4174.1.13 (  0) 0) |

Pillai, N. K.. 1963. Copepods of the family Taeniacanthidae parasitic on South Indian fishes. Crustaceana, 6: 110-128. DOI:10.1163/156854063X00507 (  0) 0) |

Pillai, N. K., 1985. The Fauna of India: Copepod Parasites of Marine Fishes. Zoological Society of India, Calcutta, 900pp.

(  0) 0) |

Pritchard, M. H., and Kruse, G. O. W., 1982. The Collection and Preservation of Animal Parasites. Technical Bulletin No. 1. The Harold W. Manter Laboratory. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 141pp.

(  0) 0) |

Ramdane, Z., 2009. Identification et écologie des ectoparasites Crustacés des poissons Téléostéens de la côte Est algérienne. Thèse de doctorat de l'Université Badji Moktar Annaba, 235pp.

(  0) 0) |

Ravichandran, S., Ajith Kumar, T. T., Ronald Ross, P., and Muthulingam, M.. 2007. Histopathology of the infestation of parasitic isopod Joryma tartoor of the host fish Parastromates niger. Research Journal of Parasitology, 2(1): 68-71. DOI:10.3923/jp.2007.68.71 (  0) 0) |

Schizas, N. V., Dahms, H. U., Kangtia, P., Corgosinho, P., and Galindo, A. M.. 2015. A new species of Longipedia Claus, 1863 (Copepoda: Harpacticoida: Longipediidae) from Caribbean mesophotic reefs with remarks on the phylogenetic affinities of Polyarthra. Marine Biology Research, 11(8): 789-803. DOI:10.1080/17451000.2015.1013556 (  0) 0) |

Sewell, R. B. S.. 1949. The littoral and semi-parasitic Cyclopoida, Monstrilloida and Notodelphyoida. Scientific Reports of the John Murray Expedition, 9(2): 17-199. (  0) 0) |

Soler-Jimenez, L. C., Morales-Serna, F. N., Aguirre-Macedo, M. L., McLaughlin, J. P., and Jaramillo, A. G.. 2019. Parasitic copepods (Crustacea, Hexanauplia) on fishes from the lagoon flats of Palmyra Atoll, Central Pacific. Zookeys, 833: 85-106. DOI:10.3897/zookeys.833.30835 (  0) 0) |

Song, C., Fang, J., Li, X., Liu, H., and Chao, C. T.. 2009. Identification and characterization of 27 conserved microRNAs in citrus. Planta, 230: 671-685. DOI:10.1007/s00425-009-0971-x (  0) 0) |

Su, Y. B., Wang, L. X., Kong, S. C., Chen, L., and Fang, R.. 2016. Complete mitochpndrial genome of Lernaea cyprinacea (Copepoda: Cyclopoida). Mitochondrial DNA Part A, 27: 1503-1504. DOI:10.3109/19401736.2014.953112 (  0) 0) |

Tamura, K., and Nei, M.. 1993. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 10: 512-526. (  0) 0) |

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G., and Gibson, T. J.. 1994. Clustal W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research, 22: 4673-4680. DOI:10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 (  0) 0) |

Uiblein, F.. 2007. Goatfishes (Mullidae) as indicators in tropical and temperate coastal habitat monitoring and management. Marine Biology Research, 3: 275-288. DOI:10.1080/17451000701687129 (  0) 0) |

Uma, D. V., and Shyamasundari, K.. 1980. Studies on the copepod parasites of fishes of the Walter Coast: Family Taeniacanthidae. Crustaceana, 39(2): 197-198. DOI:10.1163/156854080X00085 (  0) 0) |

von Nordmann, A., 1832. Mikrographische Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte der Wirbellosen Thiere. G. Reimer, Berlin, 150pp.

(  0) 0) |

Walter, T. C., and Boxshall, G., 2019. World of Copepods database. Nothobomolochus Vervoort, 1962. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species. http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=128611.

(  0) 0) |

Wang, M. X., Sun, S., Li, C. L., and Shen, X.. 2011. Distinctive mitochondrial genome of Calanoid copepod Calanus sinicus with multiple large non-coding regions and reshuffled gene order: Useful molecular markers for phylogenetic and population studies. BMC Genomics, 12: 73. DOI:10.1186/1471-2164-12-73 (  0) 0) |

Wilson, C. B.. 1911. North American parasitic copepods belonging to the family Frgasilidae. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 39: 263-400. DOI:10.5479/si.00963801.39-1788.263 (  0) 0) |

Yamaguti, S.. 1939. Parasitic copepods from fishes of Japan. Part 5. Caligoida, Ⅲ. Jubilee Volume for Professor Sadao Yoshida, 2: 443-487. (  0) 0) |

Yamaguti, S.. 1954. Parasitic copepods from fishes of Celebes and Borneo. Publications of the Seto Marine Biological Laboratory, 3(3): 137-160. (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21