2) Department of Investigation, Sichuan Police College, Luzhou 646000, China;

3) Mechanical Engineering, Texas A&M University at Qatar, Doha 23874, Qatar

More than 70% of the earth is covered by water and with the increase of the world's population and shortage of natural resources onshore, more countries have been searching for additional resources offshore. However, because of the complexity of the underwater environment and unknown hazards, most of the underwater world still remains unreachable for humans. To make underwater resources more accessible to humans, scientists and researchers have been examining ways and means to make deepsea explorations possible. Therefore, many underwater robotic vehicles, such as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), have been developed to reach areas that are too hazardous for humans to directly explore. ROVs, however, are not suitable for nontrivial and precise tasks due to their high operation cost and high operator skills requirements (Marani et al., 2009; Mohan and Kim, 2015). AUVs provide solutions to the problems experienced with ROVs and create other challenges that researchers must deal with in underwater missions, such as maintenance of underwater pipelines, deepsea explorations, and military applications (Korkmaz et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019). The most important characteristic of AUVs is their ability to perform precise tasks by an appended manipulator system. The autonomous underwater vehiclemanipulator system (AUVMS) can perform delicate tasks, such as drilling, sampling, and coring, with precision, efficiency, and autonomy that will make it the tool of trade in the future (Cieslak et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Simetti and Casalino, 2016; Sugiyama and Toda, 2016).

To enhance the performance of the AUVMS, many control schemes have been proposed by researchers. For example, Wang et al. (2017) applied adaptive control methods to overcome the uncertainties of the kinematics and dynamics of the AUVMS, and Esfahani et al. (2015) presented a time-delay control for the AVUMS by fuzzytuning the terminal sliding mode control. Huang et al. (2016) analyzed the disturbance acting on the AUVMS through the kinematic and dynamic models of the system and proposed an observer-based coordinated control scheme for the AUVMS. Sagara et al. (2010) developed a digital-type disturbance compensation control scheme for the AUVMS system using a disturbance observer and resolved-acceleration control scheme.

Most of the above studies focused on anti-disturbance control methods using an accurate model of the AUVMS and sophisticated optimization techniques (Klein and Huang, 1983; Chen et al., 2016). However, because of the irregularity of the AUVMS's shapes, measurement errors, hydrodynamic uncertainties, and time-varying dynamical characteristics, obtaining an accurate mathematical model is difficult. In addition, overcomplicated control schemes are impractical for real-life applications.

Active disturbance rejection control (ADRC) was initially proposed by (Han, 1998), and later many other researchers followed suit (e.g., Gao et al., 2002; Huang and Xue, 2014). The essential idea behind ADRC is the inclusion of the external disturbance and internal uncertainties as a 'generalized total disturbance' and the use of an extended state observer (ESO) to estimate and eliminate the disturbance in the nonlinear forward and feedback control loops (Fu and Tan, 2016). The ADRC design is independent of the system model and can explicitly mitigate the effects of the system's nonlinearities, unknown disturbances, and dynamic uncertainties. However, the complexity of the structure of the ADRC and the necessity for tuning numerous parameters is the Achilles heel of this scheme. To overcome this disadvantage, several researchers proposed a linear ADRC (LADRC) scheme with a simple structure and less parameters to tune (Gao, 2003; Ramírez et al., 2014; Morales et al., 2015). The LADRC scheme has been efficiently applied to many industrial systems (e.g., Du et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Ran et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018). Therefore, the use of the LADRC control technique to control the AUVMS is subject to multiple nonlinearities, highly coupled terms, uncertainties, and unknown disturbances is proposed here. Because the sliding mode control (SMC) scheme has better robustness properties than the PD control (Sun et al., 2018), SMC is combined here with ADRC to formulate the sliding-mode active disturbance rejection control (SMADRC) and address the control problem of the AUVMS.

As the AUVMS is a multi-input and multi-output system, many of the SMADRC's parameters must be tuned during implementation. To avoid the tedious process of parameter tuning, fuzzy logic control (FLC) is used here to achieve self-tuning. In 1973, Mamdani was one of the first researchers to successfully implement FLC to a laboratory steam engine plant and achieved good control results (Mamdani and Assilian, 1975). The same technique was effectively used to control a milling process, and its robust stability was analyzed through the circle criterion (Guerra et al., 2003). Therefore, such an FLC technique can be extended to fuzzify the LESO and SMC controllers in the LADRC scheme. Moreover, fuzzy ADRC has been studied by some researchers and successfully applied to real-life systems (e.g., Pan et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011; Su et al., 2017). However, most of the aforementioned works mainly focused on the fuzzification of the PD controller of the LADRC, but not on the LESO itself. Motivated by the aforementioned works, the fuzzification of the SMC and LESO parameters both based on the tracking error and its derivatives is proposed here to formulate the fuzzy sliding mode active disturbance rejection controller (FSMADRC) scheme.

In this work, a new FSMADRC technique is proposed to address the control problem of the AUVMS. The main contributions of this work are as follows. First, the proposed FSMADRC can achieve good trajectory tracking by the AUVMS where complex disturbances, modeling uncertainties, and coupling terms are lumped into a total disturbance and compensated by the SMADRC. Second, the fuzzy control scheme perform parameter online selftuning, which is very valuable for the practical implementation of the proposed control technique on real systems. Finally, it provides a framework for extending the proposed fuzzy rules to other SMADRC techniques.

This paper is organized as follows: The dynamic model of an AUVMS is presented in Section 2. The FSMADRC design method is given and the convergence and estimation errors of LESO are analyzed in Section 3. The setup of the simulation is described in Section 4, and the simulation results are illustrated in Section 5. Finally, some conclusions are drawn in Section 6.

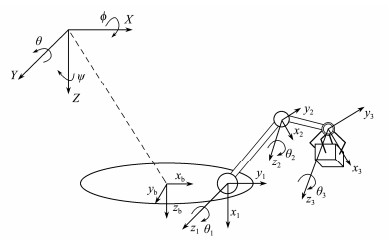

2 Dynamic Model of an AUVMSAn AUVMS with a two-link and three-joint manipulator is considered here, and its structure is shown in Fig.1. First, Ie (X, Y, Z) is defined as the earth-fixed coordinate system (inertial coordinate system), Ib (xb, yb, zb) is defined as the body-fixed coordinate system of the vehicle, and It = [xt, yt, zt]T is defined as the task space (or manipulator effector) coordinate system. The standard form of the proposed 9-degree-of-freedom (DOF) AUVMS dynamic model can be written as follows (Fossen, 1994):

|

Fig. 1 Structure of an autonomous underwater vehicle with a two-link and three-joint manipulator. |

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{\ddot q}}}+{\mathit{\boldsymbol{C}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}+{\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}+{\mathit{\boldsymbol{G}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}})+{\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}})={{\mathit{\pmb{τ}}}}_{c}+{{\mathit{\pmb{τ}}}}_{d}, $ | (1) |

where

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}}(q)=\left[\begin{array}{cc}{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}}}_{v}({{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{v})& {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{H}}}}^{\rm T}({{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{m})\\ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{H}}}({{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{m})& {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}}}_{m}({{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{m})\end{array}\right] , $ |

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{C}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}})=\left[\begin{array}{cc}{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{C}}}}_{v}({{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{v}, {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}}_{v})& 0\\ 0& {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{C}}}}_{m}({{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{m}, {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}}_{m})\end{array}\right], $ |

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}})=\left[\begin{array}{cc}{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}}_{v}({{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{v}, {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}}_{v})& 0\\ 0& {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}}_{m}({{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{m}, {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}}_{m})\end{array}\right], $ |

| $ \mathit{\boldsymbol{G}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}){{\mathit{\boldsymbol{ = }}}}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{G}}_v}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_v})}\\ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{G}}_m}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_m})} \end{array}} \right], \mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}, \mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}) = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}}_v}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}, \mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}})}\\ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}}_m}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}, \mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}})} \end{array}} \right], $ |

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tau }}_c} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tau }}_v}}\\ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tau }}_m}} \end{array}} \right], {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tau }}_d} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tau }}_{dv}}}\\ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tau }}_{dm}}} \end{array}} \right]. $ |

Then,

The vector of damping effects, including friction and hydrodynamic forces, is represented by

Of note, only the rotation of the manipulator around the z-axis in the body-fixed coordinate system is considered in this study. In addition, the vehicle and manipulator are considered rigid bodies, and the manipulator is assumed to be made up of cylindrical elements.

The AUVMS consists of a 6-DOF vehicle and 3-DOF manipulator. Therefore, the system has more DOFs than the task space, making it kinematically redundant. The transformation relationship from the task space coordinates to system states (configuration space) is given by Ismail and Dunnigan, (2011):

| $ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot I}}}}_{t}={\mathit{\boldsymbol{J}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}, $ | (2) |

where

To accurately perform underwater operations with the AUVMS, the complex underwater environment should be modeled and analyzed. A cylindrical element moving in deep water with density ρ will have hydrodynamic forces acting on it, which will be discussed in the next section.

2.1 Added MassWhen an object accelerates through a liquid, the body will also accelerate the water surrounding it, therefore, there is an added mass force in the opposite direction that affects the body motion. The effect of the added mass can be described by a matrix IA∈

| $ \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{R}}_A}}\\ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{T}}_A}} \end{array}} \right] = - {\mathit{\boldsymbol{I}}_A}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot v}}}_r}}\\ {{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tilde \omega }}}_r}} \end{array}} \right] - \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tilde \omega }}}_r}}&0\\ {{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tilde v}}}_r}}&{{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tilde \omega }}}_r}} \end{array}} \right]{{\bf{I}}_A}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot v}}}_r}}\\ {{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot \omega }}}_r}} \end{array}} \right], $ | (3) |

where vr and ωr represent the relative angular and linear velocities with respect to the ocean current velocity in the body-fixed coordinate system and

The buoyancy force vector is given by

| $ \left[\begin{array}{c}{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{R}}}}_{GB}\\ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{T}}}}_{GB}\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{c}{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{f}}}}_{G}+{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{f}}}}_{B}\\ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{r}}}}_{G}\times {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{f}}}}_{G}+{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{r}}}}_{B}\times {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{f}}}}_{B}\end{array}\right], $ | (4) |

where RGB and TGB are the resultant forces and moment of buoyancy and gravity; fB and fG denote the buoyancy and gravity force vectors; and rB and rG represent the position vectors of the buoyancy and mass centers, respectively.

2.3 Lift and Drag ForcesThe lift and drag forces refer to the forces acting on the body due to vortex shedding, pressure, and viscous forces. When a rigid body moves in the fluid, the lift forces are orthogonal to the fluid velocity and drag forces are parallel to it.

First, a first-order Gauss-Markov process is employed to model the kinematics of the ocean currents (Kim et al., 2014).

| $\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{{\dot v}_c} = - {\varepsilon _v}{v_c} + {\omega _v}}\\ {{{\dot \alpha }_c} = - {\varepsilon _\alpha }{\alpha _c} + {\omega _\alpha }}\\ {{{\dot \beta }_c} = - {\varepsilon _\beta }{\beta _c} + {\omega _\beta }} \end{array}, } \right.$ | (5) |

where vc is the ocean current velocity; αc and βc represent the orientation of the ocean current; εc, εα, and εβ are positive constants; and ωv, ωα, and ωβ are the Gaussian white noises.

The dynamic model of drag force FD can be presented as follows (Fossen, 1994; Avila and Adamowski, 2011):

| ${F_D} = {D_S}{v_r} + \frac{1}{2}\rho {C_D}({{\rm{R}}_{\rm{e}}},\alpha ){\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}}}(\alpha )v_r^2{\rm{sign}}\left| {{v_r}} \right| + o(v_r^3)' $ | (6) |

where DS is the linear skin-friction coefficient and FS = DSvr is the linear skin-friction forces. A(α) is a frontal projected area of the body and α is the attack angle. CD(Re, α) is the drag coefficient. The term

In underwater environments, the lift forces acting on a rigid body are only caused by vortex shedding and can be expressed as follows (Shah et al., 2017; Shah and Hong, 2018):

| $ {F_L} = \frac{1}{2}\rho {C_L}({{\rm{R}}_{\rm{e}}},\alpha )A(\alpha )v_r^2{\rm{sign}}\left| {{v_r}} \right|.$ | (7) |

Similarly, both the lift and drag coefficients, CL and CD, are determined by the Reynolds number Re, angle of attack α, and Keulegan-Carpenter number (KC number) (Baykal et al., 2014). The range of values of these coefficients can be empirically determined, as shown in Table 1.

|

|

Table 1 Lift and drag coefficients of a cylinder |

The lift and drag forces are conveniently defined along the relative velocity axis. The frictional force vector can be written as:

| $ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}_L} = {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{v}}}_r}^T{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}_L}{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{v}}}_r},{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}_D} = {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{v}}}_r}^T{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}_D}{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{v}}}_r}, $ | (8) |

where DL and DD are diagonal matrices containing the lift and drag coefficients. Thus, the external hydrodynamic disturbance in this paper can be represented as

| $ {{\mathit{\pmb{τ}}}}_{d}={\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{D}+{\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{L}+{{\mathit{\pmb{τ}}}}_{o}, $ | (9) |

where FD and FL are the drag force and lift forces due to vortex shedding, respectively, and τo is other external unknown and unmeasurable disturbances, such as current loads and diffractions forces.

To obtain a relatively accurate model of the AUVMS, the following properties are introduced.

Property 1. The maximum angle of the manipulator and the maximal velocity of the vehicle are considered to be finite, which means that vector q is bounded:

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}\in {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}}_{q}=\left\{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}\in {\mathbb{R} }^{9}:\Vert {\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}\Vert \le {\Vert {\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}\Vert }_{{{{\rm max}}}}\right\}.$ | (10) |

Property 2. The inertia matrix M(q) is symmetric and the positive definite function of q. The 2-norm of M(q) also is bounded:

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}})={{\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}}}^{\rm T}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}})>0, $ | (11) |

| $ \forall {\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}\in {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}}_{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\delta }_{1}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}})\le \Vert {\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}})\Vert \le {\delta }_{2}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}), $ | (12) |

where δ1(q) and δ2(q) are the position vector scalar-valued functions.

Property 3. For the AUVMS system, there are some relationships between matrices

| $ \left\{\begin{array}{l} \xi^{\mathrm{T}}[\dot{\boldsymbol{M}}(\boldsymbol{q})-2 \boldsymbol{C}(\boldsymbol{q}, \dot{\boldsymbol{q}})] \boldsymbol{\xi}=0, \forall \boldsymbol{\xi} \in \mathbb{R}^{9}, \forall \boldsymbol{q} \in \mathbb{R}^{9} \\ {[\dot{\boldsymbol{M}}(\boldsymbol{q})-2 \boldsymbol{C}(\boldsymbol{q}, \dot{\boldsymbol{q}})]^{T}=[\dot{\boldsymbol{M}}(\boldsymbol{q})-2 \boldsymbol{C}(\boldsymbol{q}, \dot{\boldsymbol{q}})]} \end{array}\right. . $ | (13) |

Property 4. There is an upper bound for the Coriolis matrix:

| $ \left\{\begin{array}{l} \forall \boldsymbol{q} \in \boldsymbol{D}_{q}, \|\boldsymbol{C}(\boldsymbol{q}, \dot{\boldsymbol{q}})\| \leq \sigma\|\dot{\boldsymbol{q}}\|_{\max }^{2} \\ \sigma=\sup\limits_{\boldsymbol{q} \in \boldsymbol{D}_{q}}\left\{\boldsymbol{C}_{b}(\boldsymbol{q})\right\} \end{array}\right., $ | (14) |

where Cb(q) is a scalar-valued function of the position vector q.

Property 5. In the dynamic model of the AUVMS, the damping matrix is positive definite (Santhakumar and Kim, 2011):

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{>}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{0}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{ }}}\forall {\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}\in {\mathbb{R} }^{9}, \forall {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}\in {\mathbb{R} }^{9}.$ | (15) |

Using the above properties, the upper bound of ‖M(q)‖ can be obtained. To design the control law, the following is defined:

| $ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}) = \mathit{\boldsymbol{\hat M}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}) + \Delta \mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}})}\\ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{C}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}, \mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}) = \mathit{\boldsymbol{\hat C}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}, \mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}) + \Delta \mathit{\boldsymbol{C}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}})} \end{array}} \right., $ | (16) |

where

Using Eqs. (1) and (16), the dynamic model of the AUVMS can be rewritten as:

| $ \hat{\boldsymbol{M}}(\boldsymbol{q}) \ddot{\boldsymbol{q}}+\hat{\boldsymbol{C}}(\boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{q}) \dot{\boldsymbol{q}}+\boldsymbol{D}(\boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{q}) \dot{\boldsymbol{q}}+\boldsymbol{G}(\boldsymbol{q})+\boldsymbol{F}^{\prime}(\boldsymbol{q}, \dot{\boldsymbol{q}})=\boldsymbol{\tau}_{c}+\boldsymbol{\tau}_{d}, $ | (17) |

where

| $ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}}^{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{'}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{(q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}})={\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}})+\Delta {\mathit{\boldsymbol{M}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{\ddot q}}}+\Delta {\mathit{\boldsymbol{C}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}}.$ | (18) |

In this section, the design problem of SMADRC is studied for the AUVMS, which is separated into 9 SISO subsystems for constructing LESO. Then, the estimation error analyses of the LESO and the closed-loop stability of the SMADRC are discussed. Then, an FSMADRC method is developed to self-tune the parameters of the proposed LESO and SMC.

3.1 SMADRC DesignThe traditional ADRC is made up of a tracking differentiator, nonlinear state feedback control law, and a nonlinear ESO, which can deal with unknown disturbances, coupling effects, and uncertainties. However, the nonlinear functions in the ADRC can be replaced by linear ones to obtain a simpler structure. Hence, the LADRC is adopted here, where the PD controller in the LADRC is replaced by an SMC. For simplicity and no loss of generality, the AUVMS is decomposed into nine subsystems, and an SMADRC is designed for each subsystem in a similar manner to the remaining eight subsystems until an overall SMADRC is obtained for the AUVMS.

The dynamic Eq. (17) of the AUVMS can be rewritten as follows:

| $ \hat{\boldsymbol{M}}(\boldsymbol{q}) \ddot{\boldsymbol{q}}+\hat{\boldsymbol{C}}(\boldsymbol{q}, \dot{\boldsymbol{q}}) \dot{\boldsymbol{q}}=\boldsymbol{\tau}_{c}+\overline{\boldsymbol{\tau}}_{d}, $ | (19) |

where

| $ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\bar \tau }}}_d} = {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_d} - ({\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}},{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}} + {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{F}}}'}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}},{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot q}}}) + {\mathit{\boldsymbol{G}}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{q}}})). $ | (20) |

Then, the AUVMS Eq. (18) can be written in an unfolded form as:

| $ \left[\begin{array}{cccc}{a}_{11}& {a}_{12}& \cdots & {a}_{19}\\ {a}_{21}& {a}_{22}& & \\ ⋮& & \ddots & \\ {a}_{91}& & & {a}_{99}\end{array}\right]\times \left[\begin{array}{c}{\ddot{y}}_{1}\\ {\ddot{y}}_{2}\\ ⋮\\ {\ddot{y}}_{9}\end{array}\right]+\left[\begin{array}{cccc}{c}_{11}& {c}_{12}& \cdots & {c}_{19}\\ {c}_{21}& {c}_{22}& & \\ ⋮& & \ddots & \\ {c}_{91}& & & {c}_{99}\end{array}\right]\times \left[\begin{array}{c}{\dot{y}}_{1}\\ {\dot{y}}_{2}\\ ⋮\\ {\dot{y}}_{9}\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{c}{u}_{1}\\ {u}_{2}\\ ⋮\\ {u}_{9}\end{array}\right]+\left[\begin{array}{c}{f}_{1}\\ {f}_{2}\\ ⋮\\ {f}_{9}\end{array}\right], $ | (21) |

in which

Some traditional methods can deal with highly coupled systems (20) via feed-forward decoupling algorithms and diagonal matrix decoupling (e.g., Lin and Mon, 2005; Yang et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2013; Barbalata et al., 2018). However, these methods are too complex to apply to an AUVMS case with complex uncertainties and disturbances. In this study, a novel technique is developed to lump the coupling terms from the other subsystems into a total disturbance to be estimated by the LESO.

Taking the first subsystem as an example and from Eq. (21), the dynamics of the first subsystem can be written as:

| $ {a}_{11}{\ddot{y}}_{1}+{a}_{12}{\ddot{y}}_{2}+\cdots {a}_{19}{\ddot{y}}_{9}+{c}_{11}{\dot{y}}_{1}+{c}_{12}{\dot{y}}_{2}\cdots +{c}_{19}{\dot{y}}_{9}={u}_{1}+{f}_{1}.$ | (22) |

Using the total disturbance concept, Eq. (22) can be rewritten as:

| $ {\ddot{y}}_{1}(t)={b}_{1}{u}_{1}(t)+{\xi }_{1}, $ | (23) |

where

| $ {\left\{ \begin{array}{l} {\xi _1} = \frac{{{f_1} - ({a_{12}}{{\ddot y}_2} + \cdots {a_{19}}{{\ddot y}_9} + {c_{11}}{{\dot y}_1} + \cdots {c_{19}}{{\dot y}_2})}}{{{a_{11}}}}\\ {b_1} = \frac{1}{{{a_{11}}}} \end{array} \right., } $ | (24) |

where ξ1 is the total disturbance of the first subsystem, including hydrodynamic forces, coupling terms, Coriolis and centrifugal terms, and other unknown disturbances, and b1 is the input parameter.

Assumption 1. The derivative of the total disturbance term ξ1 exists and it is bounded (Shao and Gao, 2016).

The lumped disturbance is defined as an extended state variable x3 = ξ1 and its time derivative

| $ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{{\dot x}_1} = {x_2}}\\ {{{\dot x}_2} = {b_1}{u_1} + {\xi _1}}\\ {{{\dot x}_3} = {w_1}}\\ {{y_1} = {x_1}} \end{array}.} \right.$ | (25) |

Using Eq. (24), one can propose a LESO as follows:

| $\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{{\dot z}_1} = {z_2} - {l_1}({z_1} - {y_1})}\\ {{{\dot z}_2} = {z_3} - {l_2}({z_1} - {y_1}) + {b_1}{u_1}}\\ {{{\dot z}_3} = - {l_3}({z_1} - {y_1})} \end{array}, } \right.$ | (26) |

where l1, l2, and l3 are the LESO parameters to be determined later. By choosing the parameters in Eq. (26) appropriately, the outputs of the LESO will converge to x1, x2, and x3 (Shao and Gao, 2016).

The observer gains can be given as:

| $ [\begin{array}{ccc}{l}_{1}& {l}_{2}& {l}_{3}\end{array}]=[\begin{array}{ccc}{\beta }_{1}{\omega }_{o1}& {\beta }_{2}{\omega }_{o1}^{2}& {\beta }_{3}{\omega }_{o1}^{3}\end{array}], $ | (27) |

where ωo1 is the observer bandwidth of the LESO and βi, and i = 1, 2, 3 are selected to ensure that s3 + l1s2 + l2s + l3 is a Hurwitz ploynomial. For example, one can let s3 + l1s2 + l2s + l3=(s+ωo1), and then the binomial coefficients can be determined by

| $ {\beta }_{i}=\frac{(n+1)!}{i!(n+1-i)!}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}1\le i\le n+1, $ | (28) |

where n = 2 is the order of the subsystem, i.e.,

| $ {\beta }_{1}=3, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\beta }_{2}=3, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\beta }_{3}=1.$ | (29) |

Next, before designing the SMADRC scheme for the subsystem Eq. (23), we recall the following lemma.

Lemma 1 (Ioannou and Sun, 1995): For V(t):[0, ∞) ∈R, if

| $ \dot{V}(t)\le -\alpha V(t)+\gamma (t), {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}\forall t\ge {t}_{0}\ge 0, $ | (30) |

then V(t) satisfies

| $ V(t)\le {e}^{-\alpha (t-{t}_{0})}V({t}_{0})+{\displaystyle {\int }_{{t}_{0}}^{t}{e}^{-\alpha (t-\tau)}}\gamma (\tau){{{\rm d}}}\tau .$ | (31) |

The sliding surface is defined as

| $ s={c}_{1}{\hat{e}}_{1}+{\dot{\hat{e}}}_{1}, $ | (32) |

where c1 > 0 is a given parameter, ê1 = ŷ1 − y1d = z1− y1d, ŷ1 is the output of the LESO, and y1d is the bounded desired output. Then, an SMC scheme is presented as follows:

| $ u=\frac{-{k}_{1}s+{\ddot{y}}_{1d}-c{\dot{\hat{e}}}_{1}-{\hat{\xi }}_{1}}{{b}_{1}}, $ | (33) |

where

Theorem 1: System Eq. (23) with the SMADRC scheme Eq. (33) and LESO Eq. (26) is considered. Choosing the sliding mode parameter k1 > 1/2 in the SMADRC leads to a bounded closed-loop system tracking error and bounded estimation error of the LESO. Moreover, if parameter k1 and parameter ωo1 in LESO Eq. (26) are large enough, then the tracking and estimation errors can converge asymptotically to zero. The convergence speed is dependent on parameter ωo1 in the LESO and k in the SMC.

Proof. From Eqs. (25) and (26), the error equation of the LESO can be obtained as:

| $ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{e_1} = {z_1} - {y_1}}\\ {{{\dot e}_1} = {e_2} - {l_1}{e_1}}\\ {{{\dot e}_2} = {e_3} - {l_2}{e_1}}\\ {{{\dot e}_3} = {w_{\bf{1}}} - {l_3}{e_1}} \end{array}.} \right.$ | (34) |

Then, Eq. (34) can be rewritten as follows:

| $ \mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot e}} = (\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}} - \mathit{\boldsymbol{LC}})\mathit{\boldsymbol{e}} + \mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}{w_1}, $ | (35) |

where L = [l1, l2, l3]T, and A, C, and D are given as follows:

| $ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{{A}}}}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}0& 1& 0\\ 0& 0& 1\\ 0& 0& 0\end{array}\right], {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{{C}}}}={\left[\begin{array}{c}1\\ 0\\ 0\end{array}\right]}^{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{T}}}}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.05em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\hspace{0.17em}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{{D}}}}=\left[\begin{array}{c}0\\ 0\\ 1\end{array}\right].$ |

For convenience, the state transformation of e can be defined as follows (Shao and Gao, 2016):

| $ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{e_1} = \omega _{o1}^{ - 2}{\eta _1}}\\ {{e_2} = \omega _{o1}^{ - 1}{\eta _2}}\\ {{e_3} = {\eta _3}} \end{array}, } \right.$ | (36) |

which can be rewritten as

| $ \mathit{\boldsymbol{e}} = \mathit{\boldsymbol{A\eta, }}$ | (37) |

where e= [e1 e2 e3]T, η= [η1 η2 η3]T, and Λ = diag{ω−2 o1, ω−1 o1, 1}. The combination of Eqs. (35) and (37) obtained

| $ \boldsymbol{\Lambda} \dot{\boldsymbol{\eta}}=(\boldsymbol{A}-\boldsymbol{L} \boldsymbol{C}) \boldsymbol{\Lambda} \boldsymbol{\eta}+\boldsymbol{E} w_{1}. $ | (38) |

Referring to the definition of Shao and Gao (2016), the error dynamics of LESO can be represented as

| $ \frac{1}{\omega_{o 1}} \dot{\boldsymbol{\eta}}=\boldsymbol{A}_{e} \boldsymbol{\eta}+\frac{1}{\omega_{o 1}} \boldsymbol{E} w_{1} $ | (39) |

where

| $ {{\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}}}}_{e}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}-{\beta }_{1}& 1& 0\\ -{\beta }_{2}& 0& 1\\ -{\beta }_{3}& 0& 0\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}-3& 1& 0\\ -3& 0& 1\\ -1& 0& 0\end{array}\right].$ | (40) |

Because Ae is a Hurwitz polynomial, for positive matrix Q there always exists a positive matrix P satisfying the following Lyapunov equation:

| $ \boldsymbol{A}_{e}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{P}+\boldsymbol{P}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{A}_{e}+\boldsymbol{Q}=0 $ | (41) |

Then, the following Layapunov function is considered:

| $ {V_o} = \frac{1}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P\eta }}\mathit{\boldsymbol{.}} $ | (42) |

The time differential of Vo can be obtained as

| $ \begin{array}{l} {{\dot V}_o} = \frac{1}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}{{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\dot \eta }}}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P\eta }} + \frac{1}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P\dot \eta }}\\ \;\;\;\mathit{ = }{({\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}}_e}\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }} + \frac{1}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}{{\mathit{\dot \xi }}_1})^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P\eta }} + {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P}}({\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}}_e}\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }} + \frac{1}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}{{\mathit{\dot \xi }}_1})\\ \mathit{ } = {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}}_e^{\rm{T}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P\dot \eta }} + \frac{1}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}{(\mathit{\boldsymbol{D}}{{\mathit{\dot \xi }}_1}{\rm{)}}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P\eta }} + {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}}_e}\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }} + \frac{1}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{PD}}{{\mathit{\dot \xi }}_1}\\ \mathit{ } = {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}}_e^{\rm{T}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{P}} + \mathit{\boldsymbol{P}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{A}}_e})\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }} + \frac{2}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}{\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{PD}}{{\mathit{\dot \xi }}_1}\\ {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} \le - {\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^{\rm{T}}}\mathit{\boldsymbol{Q\eta }} + \frac{2}{{{\omega _{o1}}}}\left\| {\mathit{\boldsymbol{PD}}} \right\| \cdot \left\| \mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }} \right\| \cdot \left| {{{\mathit{\dot \xi }}_1}} \right|\\ \;\;\;\;\; \le - {\lambda _{\min }}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{Q}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^2}{\kern 1pt} + \frac{{2\left\| {\mathit{\boldsymbol{PD}}} \right\| \cdot \left\| \mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }} \right\| \cdot \left| {{{\mathit{\dot \xi }}_1}} \right|}}{{{\omega _{o1}}}} \end{array} $ | (43) |

Because ξ1 = z1 is bounded, if parameter ωo1 is sufficiently large, then this choice will lead to

Furthermore, the following Lyapunov function is considered:

| $ {V}_{s}(t)=\frac{1}{2}{s}^{2}.$ | (44) |

Then, from Eq. (32), the differential of s can be written as

| $ \dot{s}={c}_{1}\dot{\hat{e}}+\ddot{\hat{e}}={c}_{1}\dot{\hat{e}}+{\ddot{\hat{y}}}_{1}-{\ddot{y}}_{1d}={c}_{1}\dot{\hat{e}}+{b}_{1}u+{\xi }_{1}-{\ddot{y}}_{1d}+{\dot{\hat{e}}}_{2}, $ | (45) |

where

| $ {\dot{V}}_{s}(t)=s({c}_{1}\dot{\hat{e}}+{\ddot{y}}_{1d}-{\ddot{y}}_{1d}-{k}_{1}\hat{s}-{c}_{1}\dot{\hat{e}}+{\xi }_{1}-{\hat{\xi }}_{1}+{\dot{\hat{e}}}_{2}), $ | (46) |

which can be rewritten as

| $ {\dot{V}}_{s}(t)=-{k}_{1}\cdot {s}^{2}+s({\xi }_{1}-{\hat{\xi }}_{1}+{\dot{\hat{e}}}_{2}).$ | (47) |

By defining

| $ {\dot{V}}_{s}(t)\le -{k}_{1}\cdot {s}^{2}+\frac{1}{2}{s}^{2}+\frac{1}{2}{\Delta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{2}=-(2{k}_{1}-1){V}_{s}+\frac{1}{2}{\Delta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{2}.$ | (48) |

From Lemma 1,

| $ \begin{array}{l}{V}_{s}(t)\le {e}^{-\alpha (t-{t}_{0})}{V}_{s}({t}_{0})+{\displaystyle {\int }_{{t}_{0}}^{t}{e}^{-\alpha (t-\tau)}}\gamma (\tau){{{\rm d}}}\tau \\ ={e}^{-(2k-1)(t-{t}_{0})}{V}_{s}({t}_{0})+\frac{1}{2}{\displaystyle {\int }_{{t}_{0}}^{t}{e}^{-(2k-1)(t-\tau)}}{{{\rm d}}}\tau \\ {\mathit{\boldsymbol{=}}}{e}^{-(2k-1)(t-{t}_{0})}{V}_{s}({t}_{0})+\frac{1}{2(2k-1)}{\zeta }_{1}^{2}(1-{e}^{-(2k-1)(t-{t}_{0})})\end{array}.$ | (49) |

When k1 > 1/2,

| $ \underset{t\to \infty }{\mathrm{lim}}{V}_{s}(t)\le \frac{1}{2(2{k}_{1}-1)}{\Delta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{2}.$ | (50) |

From Eqs. (42) and (44), the following close-loop Lyapunov function is considered:

| $ V={V}_{s}+{V}_{e}.$ | (51) |

Using Eqs. (43), (48) and (50) leads to

| $\dot V = {\dot V_s} + {\dot V_e} \le - (2{k_1} - 1){V_s} - {\lambda _{\min }}(\mathit{\boldsymbol{Q}}){\mathit{\boldsymbol{\eta }}^2} $ |

| $ +\frac{1}{2}{\Delta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{2}+\frac{2\Vert {\mathit{\boldsymbol{PD}}}\Vert \cdot \Vert {\mathit{\boldsymbol{η}}}\Vert \cdot \left|{\dot{\xi }}_{1}\right|}{{\omega }_{o1}}.$ | (52) |

From Eq. (52), the tracking error of the closed-loop system converges to a bounded neighborhood of zeros, and the convergence rate of the system is determined by sliding mode parameter k1 and observer parameter ωo1. The controllers and their stability for the other subsystems can be established and verified in a similar manner. Eq. (33) clearly shows that only two parameters need to be tuned for the first subsystem. In a similar manner, one can design an SMADRC scheme for each subsystem culminating in the development of an overall SMADRC scheme for the AUVMS with 18 parameters to be tuned, which is less than the number of parameters to be tuned when PID is used instead SMC.

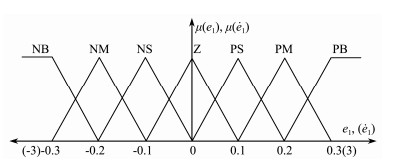

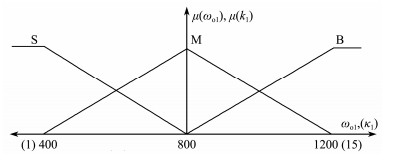

3.2 FSMADRC DesignFLC has been effectively used in the control of complex nonlinear systems, which is the main reason why FLC is proposed here for parameter self-tuning. Self-tuning is achieved by using relationships between the tracking errors and parameters of the SMC and LESO. The FLC procedure is demonstrated using the first subsystem of the AUVMS to show how to develop its FSMADRC while considering that the other subsystems are treated in a similar manner. The inputs of the FLC are the error (e1) and its derivative (ė1), in which e1 = r1 − y1, where r1 is the desired output and y1 is the actual system output. The outputs of the FLC are k1 and ωo1. In this work, Mamdani's fuzzy inference rule is adopted. There are seven fuzzy sets of e1 and ė1, which consist of negative big (NB), negative medium (NM), negative small (NS), zero (Z), positive small (PS), positive medium (PM), and positive big (PB). There are also three fuzzy sets of k1 and ωo, consisting of small (S), medium (M), and big (B). Here, the FLC is designed based on the principle that large errors correspond to low gains and small errors correspond to high gains. Then, the relationship between e1 and ė1 and parameters k1 and ωo is described in the fuzzy language and rules shown in Tables 2 and 3. The fuzzy membership functions μ(e1), μ(ė1), μ(ωo1) and μ(k1) are chosen as triangular distributions, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

|

Fig. 2 Membership functions of e1 and ė1. |

|

Fig. 3 Membership functions of ωo1 and k1. |

|

|

Table 2 Fuzzy rules of k1 |

|

|

Table 3 Fuzzy rules of ωo1 |

The fuzzy sets of e and ė are chosen as [−0.3, 0.3] and [−3, 3], and the fuzzy sets of ωo1 and k1 are chosen as [400, 1200] and [1, 15], respectively. The structure of the FSMA- DRC is shown in Fig.4. Large values for parameter ωo1 improve the effectiveness of the LESO. However, the bandwidth of the LESO can be too large in real-life applications (Gao, 2003), so a balance must be considered between the bandwidth values and their suitability for implementation.

|

Fig. 4 Structure of the FSMADRC. |

After the design completion of the first FSMADRC, the FSMADRCs for self-tuning the parameters of the remaining subsystems of the AVUMS can be developed in a similar manner.

4 Description of the TasksThe AUVMS is comprised of a 6-DOF vehicle and 3- DOF manipulator, whose parameters are chosen as Table 4. First, an open-loop analysis is conducted on the AUVMS to analyze the ocean current effects on the vehicle. Then, two typical tasks are carried out to test the control performance of the proposed FSMADRC.

4.1 Task IIn underwater operations, the capability of the AUVMS to keep the arm balanced while moving a grasped object is important. In Task I, the AUVMS is required to move

to a specified location to pick weights, move the weights to another location, and then return to the starting point. Therefore, the AUVMS will move from position [0.012 −4.71 −2.885]T at time t = 0 s in the earth-fixed coordinate system to the pick-up point [5.78 −4.69 −0.13]T at time t = 5 s along the first desired trajectory to pick up an object with 3.25 kg weight. When the AUVMS arrives at the dropoff point at t = 10 s following the second trajectory, the object will be dropped off there. Then, following a third desired trajectory, the vehicle reverses the course to the stop position at [3.945 −3.412 −5.03]T and reaches it time t = 15 s. The joint angles of the manipulator are kept at [θ1 θ2 θ3]T= [60˚ 30˚ 20˚]T.

The desired motion trajectories of the vehicle are chosen as a cubic time polynomial given by

| $ \begin{array}{l}\left\{\begin{array}{l}X:0.012-2\times {10}^{-3}{t}^{2}+5\times {10}^{-2}{t}^{3}\\ Y:-4.71-6\times {10}^{-3}{t}^{2}-1.35\times {10}^{-3}{t}^{3}\\ Z:-2.885-4.63\times {10}^{-2}{t}^{2}+1.145\times {10}^{-1}\times {t}^{3}\end{array}\right\}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{ }}}0\le t\le 5s\\ \left\{\begin{array}{l}X:5.947-2\times {10}^{-2}{t}^{2}-2.5\times {10}^{-3}{t}^{3}\\ Y:-4.456-1.86\times {10}^{-3}{t}^{2}+1.85\times {10}^{-3}{t}^{3}\\ Z:-1.0028-1.23\times {10}^{-3}{t}^{2}-8.5\times {10}^{-4}\times {t}^{3}\end{array}\right\}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{ }}}5s<t\le 10s\\ \left\{\begin{array}{l}X:8.5125-2.105\times {10}^{-2}{t}^{2}+5.1\times {10}^{-5}\times {t}^{3}\\ Y:-2.78-4.5\times {10}^{-2}{t}^{2}-2.8125\times {10}^{-3}{t}^{3}\\ Z:-1.8572+5.862\times {10}^{-2}{t}^{2}-4.85\times {10}^{-3}\times {t}^{3}\end{array}\right\}, {\mathit{\boldsymbol{ }}}10s<t\le 15s\end{array}.$ | (53) |

To reduce the power consumption of the vehicle when moving in deep waters, the frequent switching of the rudder angle should be avoided. Therefore, the amplitude of the variation of the path angles (roll, yaw, and pitch angles) should also be included in the closed-loop system.

4.2 Task IIThe inertia coupling forces always act on the vehicle to force it to vibrate when the manipulator swings at a high frequency. The accuracy of the hovering operations of the AUVMS is important to study; therefore, in Task II, the AUVMS is required to hover at a fixed position. Task II is designed to test the capability of the FSMADRC in dealing with rapidly changing external forces and high coupling effects. In this task, only the angles of the manipulator joints are allowed to vary, and the vehicle is kept in still mode. The working position of the AUVMS is set as [0 0 0]T in the earth-fixed coordinate frame.

In addition, during the moving process, the roll, yaw, and pitch angles of the vehicle remain at zero, whereas the joints' angle trajectories of the manipulator are given by

| $ \left\{ \begin{array}{l} {\theta _1} = (- 2.21 - 28.521t + 2.862{t^2})\sin (3.024 - 0.2132t - 0.212{t^2} - 0.035{t^3})\\ {\theta _2} = (3.015 - 10.2135t - 1.021{t^2})sin(0.6631 + 0.645t + 0.36{t^2} - 0.0664{t^3})\\ {\theta _3} = (3.3232 - 10.046t - 1.0454{t^2})\sin (0.2155 + 0.06446t - 0.1245{t^2} - 0.00213{t^3}) \end{array} \right. $ | (54) |

In this section, the control performance of the FSMA- DRC will be studied, and compared with PID controllers and classic FLC (CFLC), which are chosen respectively as

| $ \left\{ \begin{array}{l} {\tau _{PID}} = {K_p} + {K_i}\int {e{\rm{d}}t + {K_d}} e\\ {\tau _{{\rm{CFLC}}}} = {K_c}{U_{{\rm{CFLC}}}} \end{array} \right. $ | (55) |

where Kp, Ki, and Kd are the parameters of the PID controller, Kc is the output scaling gain of the CFLC controller, and UCFLC is its control output.

In accordance with the membership functions in Tasks I and II, the fuzzy sets for both tasks are chosen as [−0.3, 0.3] for the error, [−3, 3] for the derivative of the error, [1, 15] for the bandwidth of the controller, and [400, 1200] for the bandwidth of the observer. Here, all SMC parameters ci, i = 1, …, 9 of the subsystems are set to be 10.

5.1 Results of Task IThe simulation results of Task I are shown in Figs. 5– 11. The 3D view of the moving trajectories of the center of gravity of the vehicle controlled by different controllers are depicted in Fig.5. The tracking errors are shown in Fig.6, which also shows that the FSMADRC can track the desired trajectories more accurately than the CFLC and PID, especially during picking up and dropping off the weights.

|

Fig. 5 Trajectory of the AUV in Task I in a 3D view: (green) desired trajectory, (dashed-black) using FSADRC, (blue) using CFLC, (red) using PID control. |

|

Fig. 6 Trajectories of the tracking error of the AUV in Task I: (black) using FSMADRC, (blue) using CFLC, and (red) using PID control. |

The LESO can estimate the disturbance resulting from the additional load weight picked up by the AUVMS and cancel its effect in the closed-loop system. Thus, the proposed method can ensure that the FSMADRC spends less buffering time to track the desired trajectories.

Fig.7 shows that the proposed FSMADRC can keep the manipulator stable when picking up and dropping off the load weight and spends less time restoring the original angles. However, the other two controllers were not able to achieve this objective. Next, as shown in Fig.8, the roll, yaw, and pitch angle trajectories resulting from using the FSMADRC switch much more smoothly than those resulting from the PID and CFLC schemes. Moreover, the FSMADRC achieves better control performance with less energy consumed than the CFLC and PID, as shown in Fig.9. The disturbance estimation performance of the LESOs is shown in Fig.10, in which e1 – e9 correspond to the total disturbance estimation errors of the LESO in each of the nine subsystems. Clearly, the estimation errors converge to a small neighborhood of zero, which ensures an effective rejection of the total disturbance.

|

Fig. 7 Trajectories of joint angles of the AUVMS in Task I: (black) using FSMADRC, (blue) using CFLC, and (red) using PID control. |

|

Fig. 8 Path angle of the AUV in Task I: (black) using FS- MADRC, (blue) using CFLC, and (red) using PID control. |

|

Fig. 9 Comparison of the power consumption in Task I. |

|

Fig. 10 Total disturbance estimation error of each LESO in Task I. |

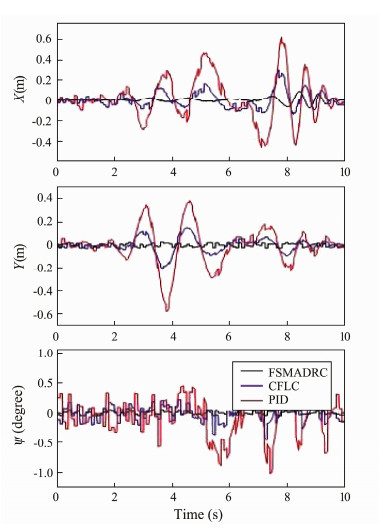

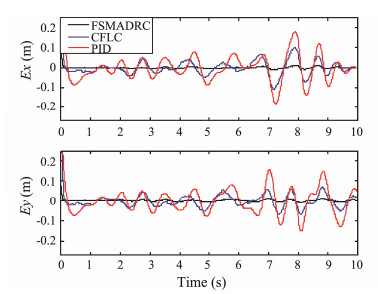

The simulation results of Task II are presented in Figs. 11–14. Figs. 11 and 12 show that the proposed method can track the swaying trajectories and keep the vehicle stable in a fixed position relatively better than the PID and CFL control schemes. In addition, the yaw angle of the AUV- MS under the FSMADRC exhibits better stability performance than that under the other two controllers. Fig.13 shows that the FSMADRC demonstrates better performance in trajectory tracking by the end effector than that under the PID or CFL control scheme. Moreover, the FS- MADRC consumes less energy than the other two controllers while performing Task II, as shown in Fig.14.

|

Fig. 11 Trajectory tracking errors of the joint angles of the AUVMS in Task II: (black) using FSMADRC, (blue) using CFLC, and (red) using PID control. |

|

Fig. 12 Position response and yaw angle of the AUV in Task II: (black) using FSMADRC, (blue) using CFLC, and (red) using PID control. |

|

Fig. 13 Trajectory tracking errors of the end effector of the AUVMS in Task II: (black) using FSMADRC, (blue) using CFLC, and (red) using PID control. |

|

Fig. 14 Power consumption comparison for Task II. |

Underwater robotics has attracted a lot of attention from the research community for applications previously deemed impossible to be performed by humans. Applications, such as surveys, security, explorations, subsea engineering, and oil/gas explorations, require spot discoverries and manipulation. Oftentimes, the aforementioned tasks/ missions are executed using ROVs or divers, which is costly and often puts human life at risk. Underwater vehicles equipped with manipulator(s) have proven to provide a cost-effective solution to deep-sea missions and put human operators out of harm's way. An underwater vehicle equipped with a two-link and three-joint manipulator is studied here for performing routine tasks under uncertain and harsh environmental conditions. The FSMADRC method is used in the closed-loop system to address the tracking problem of the AUVMS, and the results are compared with those of the commonly used PID and CFL control schemes. The simulation results show that FSMA- DRC achieves better control performance than the PID and CFLC schemes. The proposed FSMADRC is independent of the AUVMS model and only needs limited knowledge of the system's model. Finally, the proposed scheme achieves better control performance than the other two reference control methods with less power consumption. In addition, the FSMADRC can determine (selftune) the appropriate parameters adaptively, which makes it very suitable for real-life applications and can be easily extended to other vehicle systems.

AcknowledgementsThis work is supported in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 201964012), the Open Foundation of Henan Key Laboratory of Underwater Intelligent Equipment (No. KL02A 1802), and the National Natural Science Foundations of China (Nos. 61603361 and 51979256), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2017MEE015).

Avila, J. P. and Adamowski, J. C., 2011. Experimental evaluation of the hydrodynamic coefficients of a ROV through Morison's equation. Ocean Engineering, 38(3): 2162-2170. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2011.09.032 (  0) 0) |

Barbalata, C., Dunnigan, M. and Petillot, Y., 2018. Coupled and decoupled force/motion controllers for an underwater vehiclemanipulator system. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 96(6): 1-23. DOI:10.3390/jmse6030096 (  0) 0) |

Baykal, C., Sumer, B. M., Fuhrman, D. R., Jacobsen, N. G. and Fredsøe, J., 2014. Numerical investigation of flow and scour around a vertical circular cylinder. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 373(2033): 20140104. DOI:10.1098/rsta.2014.0104 (  0) 0) |

Chen, W., Yang, J., Guo, L. and Li, S., 2016. Disturbance observer based control and related methods – An overview. IEEE Transaction on Industrial Electronics, 63(2): 1083-1095. DOI:10.1109/TIE.2015.2478397 (  0) 0) |

Cieslak, P., Ridao, P., and Giergiel, M., 2015. Autonomous underwater panel operation by GIRONA500 UVMS: A practical approach to autonomous underwater manipulation. IEEE International Conference on Robotics & Automation. Seattle, WA, 529-536, DOI: 10.1109/icra.2015.7139230.

(  0) 0) |

Du, B., Wu, S., Han, S. and Cui, S., 2016. Application of linear active disturbance rejection controller for sensorless control of internal permanent-magnet synchronous motor. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 63(5): 3019-3027. DOI:10.1109/TIE.2016.2518123 (  0) 0) |

Esfahani, H. N., Azimirad, V. and Danesh, M., 2015. A time delay controller included terminal sliding mode and fuzzy gain tuning for underwater vehicle manipulator systems. Ocean Engineering, 107: 97-107. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2015.07.043 (  0) 0) |

Fossen, T. I., 1994. Guidance and Control of Ocean Vehicles. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 99-113, DOI: 10.1016/0005-1098(96)82331-4.

(  0) 0) |

Fu, C. and Tan, W., 2016. Linear active disturbance rejection control: Analysis and tuning via IMC. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 63(4): 2350-2359. DOI:10.1109/tie.2015.2505668 (  0) 0) |

Gao, Z., 2003. Scaling and bandwidth-parameterization based controller tuning. Proceedings of the 2003 American Control Conference. Denver, 4989-4996, DOI: 10.1109/ACC.2003.1242516.

(  0) 0) |

Gao, Z., Huang, Y. and Han, J., 2002. An alternative paradigm for control system design. IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, 25(5): 4578-4585. DOI:10.1109/cdc.2001.980926 (  0) 0) |

Guerra, R. E. H., Schmitt-Braess, G. and Haber, R. H., 2003. Using circle criteria for verifying asymptotic stability in PIlike fuzzy control systems: Application to the milling process. IEEE Proceedings – Control Theory and Applications, 150(6): 619-628. DOI:10.1049/ip-cta:20030795 (  0) 0) |

Han, J., 1998. Active disturbance rejection controller and its applications. Control and Decision, 13(1): 19-23 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Huang, Y. and Xue, W., 2014. Active disturbance rejection control: Methodology and theoretical analysis. ISA Transactions, 53(4): 963-976. DOI:10.1016/j.isatra.2014.03.003 (  0) 0) |

Huang, H., Tang, Q., Li, H., Le, L., Li, W. and Pang, Y., 2016. Vehicle-manipulator system dynamic modeling and control for underwater autonomous manipulation. Multibody System Dynamics, 47(3): 125-147. (  0) 0) |

Ioannous, P. A., and Sun, J., 1995. Robust Adaptive Control. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1-24, DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4471-5058-9_118.

(  0) 0) |

Ismail, Z. H. and Dunnigan, M. W., 2011. Tracking control scheme for an underwater vehicle-manipulator system with single and multiple sub-regions and sub-task objectives. IET Control Theory & Applications, 5(5): 721-735. DOI:10.1049/iet-cta.2010.0174 (  0) 0) |

Kim, Y., Mohan, S. and Kim, J., 2014. Task space-based control of an underwater robotic system for position keeping in ocean currents. Advanced Robotics, 28(16): 1109-1119. DOI:10.1080/01691864.2014.913504 (  0) 0) |

Klein, C. A. and Huang, C. H., 1983. Review of pseudoinverse control for use with kinematically redundant manipulators. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 13(2): 245-250. DOI:10.1109/TSMC.1983.6313123.119 (  0) 0) |

Korkmaz, O., Ider, S. K., and Özgören, M. K., 2013. Control of an underactuated underwater vehicle manipulator system in the presence of parametric uncertainty and disturbance. 2013 American Control Conference. Washington, D. C., 578-584, DOI: 10.1109/ACC.2013.6579899.

(  0) 0) |

Li, J., Xia, Y., Qi, X. and Gao, Z., 2016. On the necessity, scheme and basis of the linear-nonlinear switching in active disturbance rejection control. IEEE Transaction on Industrial Electronics, 62(2): 1425-1435. DOI:10.1109/TIE.2016.2611573 (  0) 0) |

Li, X. G., Wang, H. D., Li, M., Ling, Z., Xiao, H. and Hou, D., 2018. Linear active disturbance rejection controller design for underwater vehicle manipulators with 2-links. IEEE 2018 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), 18(8): 875-880. DOI:10.1109/CAC.2018.8623694 (  0) 0) |

Lin, C. M. and Mon, Y. J., 2005. Decoupling control by hierarchical fuzzy sliding-mode controller. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, 13(4): 593-598. DOI:10.1109/tcst.2004.843130 (  0) 0) |

Liu, X., Tang, L. and Zhou, L., 2011. Fuzzy active disturbance rejection control of three-motor synchronous system. Control Engineering & Applied Informatics, 13(4): 51-57. DOI:10.1109/tcst.2004.843130 (  0) 0) |

Mamdani, E. H. and Assilian, S., 1975. An experiment in linguistic synthesis with a fuzzy logic controller. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 7(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1016/S0020-7373(75)80002-2 (  0) 0) |

Marani, G., Choi, S. K. and Yuh, J., 2009. Underwater autonomous manipulation for intervention missions AUVs. Ocean Engineering, 36(1): 15-23. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2008.08.007 (  0) 0) |

Mohan, S. and Kim, J., 2015. Coordinated motion control in task space of an autonomous underwater vehicle-manipulator system. Ocean Engineering, 104: 155-167. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2015.05.011 (  0) 0) |

Morales, R., Sira-Ramírez, H. and Somolinos, J. A., 2015. Linear active disturbance rejection control of the hovercraft vessel model. Ocean Engineering, 96: 100-108. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2014.12.031 (  0) 0) |

Pan, W., Xiao, H., and Wang, C., 2010. Design of ship course controller based on optimal active disturbance rejection technique. In: Advances in Computer Science, Environment, Ecoinformatics, and Education. CSEE 2011. Communications in Computer and Information Science. Lin, S., and Huang, X., eds., Springer, Berlin, 232-236.

(  0) 0) |

Ramírez-Neria, M., Sira-Ramírez, H., Garrido-Moctezuma, R. and Luviano-Juárez, A., 2014. Linear active disturbance rejection control of underactuated systems: The case of the Furuta pendulum. ISA Transaction, 53(4): 920-928. DOI:10.1016/j.isatra.2013.09.023 (  0) 0) |

Ran, M., Wang, Q. and Dong, C., 2016. Stabilization of a class of nonlinear systems with actuator saturation via active disturbance rejection control. Automatica, 63: 302-310. DOI:10.1016/j.automatica.2015.10.010 (  0) 0) |

Sagara, S., Yatoh, T. and Shimozawa, T., 2010. Digital RAC with a disturbance observer for underwater vehicle-manipulator systems. Artificial Life & Robotics, 15(3): 270-274. DOI:10.1007/s10015-010-0806-7 (  0) 0) |

Santhakumar, M., and Kim, J., 2011. Modelling, simulation and model reference adaptive control of autonomous underwater vehicle manipulator systems. International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems. Gyeonggi-do, 643-648, DOI: doi.org/10.1049/ip-cta:20030795.

(  0) 0) |

Shah, U. H. and Hong, K. S., 2018. Active vibration control of a flexible rod moving in water: Application to nuclear refueling machines. Automatica, 93: 231-243. DOI:10.1016/j.automatica.2018.03.048 (  0) 0) |

Shah, U. H., Hong, K. S. and Choi, S. H., 2017. Open-loop vibration control of an underwater system: Application to refueling machine. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 22(4): 1622-1632. DOI:10.1109/TMECH.2017.2706304 (  0) 0) |

Shao, S. and Gao, Z., 2016. On the conditions of exponential stability in active disturbance rejection control based on singular perturbation analysis. International Journal of Control, 90(10): 2085-2097. (  0) 0) |

Simetti, E. and Casalino, G., 2016. Manipulation and transportation with cooperative underwater vehicle manipulator systems. IEEE Journal of Ocean Engineering, 42(4): 1-18. DOI:10.1109/JOE.2016.2618182 (  0) 0) |

Su, T. J., Wang, S. M., Tsai, S. H. and Tsou, T. Y., 2017. Design of fuzzy and linear active disturbance rejection control for insulin infusion in type 1 diabetic patients. International Journal of Fuzzy Systems, 19: 1966-1977. DOI:10.1007/s40815-017-0318-x (  0) 0) |

Sugiyama, N., and Toda, M. A., 2016. Nonlinear disturbance observer using delayed estimates its application to motion control of an underwater vehicle-manipulator system. 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Daejeon, 2007-2013, DOI: 10.1109/IROS.2016.7759316.

(  0) 0) |

Sun, Z., Zheng, J., Man, Z., Wang, H. and Lu, R., 2018. Sliding mode-based active disturbance rejection control for vehicle steer-by-wire systems. IET Cyber-Physical Systems: Theory & Applications, 3(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1049/iet-cps.2016.0013 (  0) 0) |

Wang, Y., Jiang, S., Chen, B. and Wu, H., 2017. Trajectory tracking control of underwater vehicle-manipulator system using discrete time delay estimation. IEEE Access, 99(5): 7435-7443. DOI:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2701350 (  0) 0) |

Xu, T., Wang, J., Shi, W., Wang, J. and Chen, Z., 2019. A Localization algorithm using a mobile anchor node based on region determination in underwater wireless sensor networks. Journal of Ocean University of China, 18(2): 394-402. DOI:10.1007/s11802-019-3724-x (  0) 0) |

Yang, H., Sun, J., Xia, Y. and Zhao, L., 2018. Position control for magnetic rodless cylinders with strong static friction. IEEE Transaction on Industrial Electronics, 65(7): 5806-5815. DOI:10.1109/TIE.2017.2782198 (  0) 0) |

Yang, M., Li, R. and Chu, T., 2013. Controller design for disturbance decoupling of Boolean control networks. Automatica, 49(1): 273-277. DOI:10.1016/j.automatica.2012.10.010 (  0) 0) |

Yang, Q., Su, H. and Tang, G., 2016. Approximate optimal tracking control for near-surface AUVs with wave disturbances. Journal of Ocean University of China, 15(5): 789-798. DOI:10.1007/s11802-016-2986-9 (  0) 0) |

Yang, Y. P., Zhao, Y. X., Hao, Y. L. and Du, H. Y., 2012. Decoupling control system for AUV hovering near-surface. Systems Engineering and Electronics, 34(3): 572-577 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhang, W., Xu, H. and Ding, X., 2015. Design and dynamic analysis of an underwater manipulator. Proceedings of the 2015 Chinese Intelligent Automation Conference, 338: 399-409. DOI:10.1007/978-3-662-46466-3_40 (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19