2) Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Fisheries Research Institute, Urumqi 830002, China

The brine shrimp Artemia Leach, 1819 (Crustacea: Anostraca) is a small planktonic crustacean living in hypersalinity habitats all over the world except the Antarctic (Vanhaecke et al., 1987; Van Stappen, 2002). The genus contains several bisexual species and numerous parthenogenetic populations (Asem et al., 2020; Sainz-Escudero et al., 2021). Both bisexual and parthenogenetic Artemia have two reproductive modes: oviparity producing resting eggs (cysts) and ovoviviparity producing free-swimming nauplii in a single individual's lifespan, and females have the ability to switch between the two reproduction modes (Lavens and Sorgeloos, 1987; Nambu et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2019). As Artemia nauplii are favorite living foods for larval fishes and crustaceans, and resting eggs are easy to store and circulate, resting eggs have great economic value and are commercially harvested and traded around the world. In addition to the large number of wild populations, Artemia are also cultured in manmade brine ponds in countries like Brazil, Vietnam, China, Philippines and Thailand (Van Stappen et al., 2020).

Artemiaresting eggs, which are gastrulas and each contains some 3000 – 4000 cells (Clegg and Conte, 1980), represent the diapause stage in Artemia lifecycle and allow Artemia to overwinter and survive harsh conditions (Lavens and Sorgeloos, 1987). Among brine shrimps, Artemia monica Verrill, 1869 in Mono Lake (Lenz, 1980; Drinkwater and Crowe, 1991) and the parthenogenetic Artemia in Dabancheng Salt Lake (Ren et al., 1996) were reported to produce benthic resting eggs (see further). All other Artemia species/populations produce resting eggs floating on the water surface, though a certain fraction of benthic resting eggs may coexist with the floating ones (e.g., Abatzopoulos et al., 2006; Arashkevich et al., 2009; Litvinenko et al., 2016). This is different from resting eggs of many other planktonic animals, which usually sink to the sediments after being laid, e.g., resting eggs of rotifers (Gilbert, 2017) and copepods (Tachibana et al., 2019). The floating capacity of resting eggs brings obvious benefits to the life and procreation of Artemia. For instance, they can be kept away from the lower oxygen of bottom waters, exposed to light, and blown leeward and aggregated along the shoreline, where they have more opportunities to encounter the low salinity water (from precipitation/runoff) and higher temperature in the next warming season. Moreover, floating eggs have more opportunities of dispersal by wind and aquatic migratory bird transportation (Proctor, 1964; Van Stappen, 2002; Eimanifar et al., 2006). Because it is difficult to catch resting eggs from sediments, the commercial harvestability of Artemia resting eggs is largely dependent on their buoyancy. Although the buoyancy of Artemia resting eggs is a character of both biological and economical importance, few studies have been documented. Sorgeloos (1996) and Abatzopoulos et al. (2006) compared the resting egg buoyancy of Artemia urmiana Günther, 1899 (Urmia Lake, Iran) and Artemia franciscana Kellogg, 1906 (Great Salt Lake, USA) and found that the former species had a higher fraction of sinking eggs than the latter species. Ren et al. (1996) tested the buoyancy of resting eggs from Dabancheng Salt Lake (Xinjiang, China) and found they were not floating until increasing the salinity to 140. Litvinenko et al. (2016) found that the hatching rate of floating resting eggs was significantly higher than that of sinking eggs in most Western Siberia lakes, but might not be so obvious in some seasons or lakes. Sura and Belovsky (2016) reported that selective harvesting of floating eggs had caused a decrease in the buoyancy of resting eggs in the Great Salt Lake, and the mortality of nauplii was negatively related with the buoyancy of resting eggs. Their experimental study also showed that parents with adequate food sources tended to produce floating eggs, while undernourished parents tended to produce sinking eggs even if they were hatched from floating eggs.

The habitat of Artemia varies considerably in many aspects such as ion composition, climatic condition, altitude, etc. (Triantaphyllidis et al., 1998). Since the buoyancy of resting eggs is dependent on the specific weight or the salinity of ambient water, we suppose that the habitat salinity may exert a selection pressure on the buoyancy of resting eggs, and thereby the buoyancy of resting eggs from different Artemia populations may be different and is correlated with their habitat salinity. To test this hypothesis, we compared the buoyancy of resting eggs from different Artemia populations. Moreover, previous studies have suggested that the absence of floating capacity in resting eggs of A. monica was a consequence of their thin shell (Drinkwater and Crowe, 1991), and the lower floating capacity of A. urmiana resting eggs (compared with those of A. fran- ciscana) was because of their narrower and more compressed alveolae in the shell (Abatzopoulos et al., 2006). To further examine the relationships between the buoyancy and some intrinsic features of resting eggs, the dry weight of intact and decapsulated eggs, the chorion thickness, the weight and volume proportions of the chorion in the intact eggs were also studied in this paper.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Artemia Resting EggsResting eggs were from 25 hypersaline habitats, including 21 inland salt lakes and 4 coastal solar salterns. Their locations, abbreviated codes, habitat salinities, sampling time, reproductive modes, and hatching percentages are shown in Table 1. Hatching percentages of resting eggs were determined at salinity of 30 and temperature of 25℃. For some populations, resting eggs were treated with 3% H2O2 for 40 min to break diapause before determining the hatching rate. In a previous study, Sura and Belovsky (2016) accounted that resting egg buoyancy was unlikely influenced by cyst viability or the length of time the resting eggs were in diapause. The hatching rate of their oldest sample (stored for 23 years) was 40%. Accordingly, only resting egg samples with a minimum hatching percentage of 40% were used in the present study.

|

|

Table 1 Artemia resting eggs used in the present study |

The buoyancy of Artemia resting eggs was tested with solutions of gradient salinities (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160, 180, 200, 220, 240, 260, 280, 300, 320). To determine the FS50 (salinity with 50% resting eggs floating; see below) precisely, resting eggs of some populations were tested under additional salinities, e.g., salinities of 10, 30 and 50 were used when testing the buoyancy of KXC resting eggs. Solutions with salinities of 0 to 260 were prepared by dissolving NaCl in distilled water, and higher-salinity solutions were prepared by dissolving MgCI2·6H2O in distilled water.

Buoyancy experiments were conducted in 150 mm (height) × 18 mm (diameter) test tubes each containing 10-cm deep experimental medium. At the beginning of each test, a small number (100 – 200) of non-damaged resting eggs were put into each test tube, and incubated at 0℃ for 12 h and then at 20℃ for 1 h. Resting eggs floating on the water surface and sinking to the bottom of test tubes were counted, respectively. Sometimes there were few resting eggs suspending in the water column, 50% of such eggs were counted as floating eggs and the other 50% as sinking eggs. Three replicates were performed for each test. The following parameters/terms were used:

| $ \text { Percentage of floating resting eggs }(\mathrm{PF})=\frac{\text { Number of floating resting eggs }}{\text { Number of floating resting eggs }+\text { Number of sinking resting eggs }} \times 100 \% \text {. } $ |

Fraction of the 'apparent specific weight' of resting eggs (FSW): The difference of PF values between two neighboring experimental salinities. For example, if PFs were 25% and 45% at the neighboring salinities of 40 and 60 respectively, the FSW40 – 60 would be: 45% − 25% = 20%. Here the 'apparent specific weight' is an ideal concept, and it is expressed by the salinity at which eggs are expected to suspend in the water column (in the above example, the 'apparent specific weight' of the eggs of the fraction should range from 40 to 60).

FS50: The salinity that 50% of resting eggs float. It was estimated on the linear regression equation obtained from PF values under several key salinities.

2.3 Determination of the Dry Weight of Intact and Decapsulated EggsFor each population, a small number of resting eggs were incubated in distilled water at 0℃ for 12 h to make sure the resting eggs fully hydrated. Then eggs were divided into two groups. One group of eggs were decapsulated using 8% NaClO solution for 2 – 3 min, washed with distilled water until there were no impurities; the other group were untreated. Then 50 – 150 intact or decapsulated eggs were counted, and put into a 0.2-mL centrifuge tube (pre-heated at 65℃ for 24 h), dried at 65℃ for 24 h, and then weighed using a MYA 5.4Y (Radwag Wagi Electroniczne) electronic balance. The average weight of individual egg was calculated. Three replicates were performed for each population. The following parameter was calculated for each population:

| $ \text { Weight percentage of chorion in intact eggs }=\frac{\text { Average weight of intact eggs }-\text { Average weight of decapsulated eggs }}{\text { Average weight of intact eggs }} \times 100 \% $ |

Resting eggs were incubated in seawater with a salinity of 30 at 0℃ for 12 h. Then eggs were divided into two groups for determining diameters of intact and decapsulated eggs (method of decapsulation, see above), respectively. Diameters were measured using an Olympus SZX16 stereomicroscope equipped with an Olympus DP74 camera. For each population, 100 intact and 100 decapsulated eggs were measured, respectively. The volume of each egg was calculated using the volume formula for a solid sphere:

| $ V = 4/3πr^{3}, $ |

where V and r are the volume and radius of the egg, respectively. The following parameters are calculated:

| $ \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\text { Chorion thickness }=\text { (Average diameter of intact eggs }-\text { Average diameter of decapsulated eggs }) / 2 \text {, }\\ \text { Volume percentage of chorion in intact eggs }=\frac{\text { Average volume of intact eggs }-\text { Average volume of decapsulated eggs }}{\text { Average volume of intact eggs }} \times 100 \%$ |

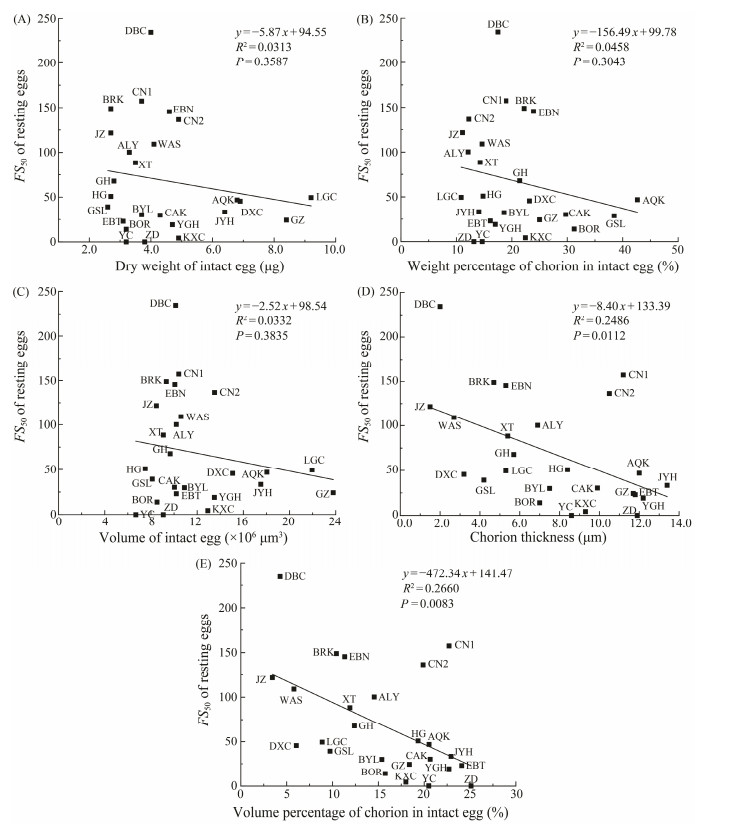

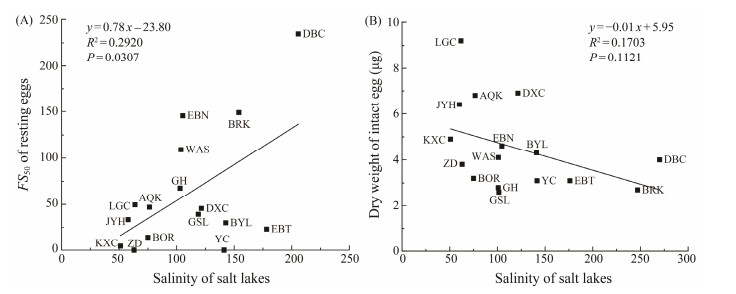

To analyze factors that potentially influence the buoyancy of resting eggs, correlation and regression analyses were conducted between 1) the FS50 and the dry weight of intact eggs; 2) the FS50 and the weight percentage of the chorion in intact eggs; 3) the FS50 and the volume of intact eggs; 4) the FS50 and the chorion thickness; 5) the FS50 and the volume percentage of the chorion in intact eggs; 6) the FS50 and the habitat salinity; 7) the habitat salinity and the dry weight of resting eggs. We suppose that the selection effect of salinity on the buoyancy of resting eggs (if any) may become observable only after an accumulation of enough generations. A directional evolution of resting egg buoyancy was observed after 20 years' selective catching of floating eggs (Sura and Belovsky, 2016). Considering the data availability and the salinity fluctuation between different years/seasons, the mean of salinities recorded during the 30 years until the sampling time was adopted as the habitat salinity of each population. Original salinity data were obtained from literature or measured on site. When salinities of different stations were provided in a literature, their mean was used as the salinity value of the lake. In case salinities of different months/dates were provided in a literature, they were averaged first, and then the mean of different years was calculated. Due to the high variation of salinities among different ponds in an artificial salt production system (coastal solar salterns), and the unavailability of salinities for some inland populations (see Notes of Table 1), 9 populations were excluded from the last two analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using OriginPro 2018C, and P values calculated by GraphPad Prism Version 5.01. The difference was considered significance when P < 0.05.

3 Results 3.1 Buoyancy of Resting EggsThe left column of Fig.1 shows PF values at different salinities. For JZ, XT, JYH, BRK, GH, CN1 and WAS populations (The full names of the abbreviations can be referred in Table 1), the minimum salinity with some resting eggs floating was 20 (Figs.1A, C, F, I, L, N and V). It was 40 for CN2 population (Fig.1O), and 180 for DBC population (Fig.1J). For the remaining 16 populations, some eggs were floating in distilled water (Figs.1B, D, E, G, H, K, M, P – U, W – Y). The salinity at which all resting eggs were floating (i.e., PF = 100%) varied from 80 to 320, with the lowest value being recorded in YGH and ZD populations (Figs.1D, K), and the highest value in DBC population (Fig.1J). The change of PF with the increase of salinity varied among populations, and could be roughly classified into three patterns. 1) The PF increased at a constant speed (a linear increase), represented by JZ, DBC, GH and DXC populations (Figs.1A, J, L, T); 2) PF increased slowly under lower and higher salinities, while increased rapidly under median salinities (a S-curve increase), represented by XT, EBN, BRK, CN1, CN2, ALY, and WAS populations (Figs.1C, H, I, N – P, V); 3) PF increased rapidly under lower salinities, represented by HG, YGH, YC, JYH, AQK, ZD, CAK, GZ, KXC, LGC, GSL, EBT, BYL and BOR populations (Figs.1B, D – G, K, M, Q – S, W – Y).

|

Fig. 1 A comparison of the buoyancy of resting eggs from 25 different Artemia populations. Left column, percentage of floating resting eggs (PF) under different salinities (mean ± SD). Right column, distribution of the fraction of 'apparent specific weight' (FSW). '–x' means a salinity interval between a neighboring lower salinity and salinity x, e.g., '–20' means the salinity of 0 – 20 (to be continued). |

In terms of FS50 (Table 2), the lightest resting eggs were represented by the populations ZD, YC (FS50 not determined because over 50% resting eggs were floating in distilled water) and KXC (FS50 = 4.3), while the DBC population had the heaviest resting eggs (FS50 = 234.5). There were 14 populations (HG, XT, YGH, JYH, AQK, GH, CAK, GZ, LGC, DXC, GSL, EBT, BYL, BOR) with their FS50 values between 10 and 100, and 7 populations (JZ, EBN, BRK, CN2, ALY, CN1, WAS) with their FS50 values between 100 and 200.

|

|

Table 2 Biometric values and FS50 for Artemia resting eggs from 25 localities |

As shown by the FSW values (Fig.1), the composition of the 'apparent specific weight' of resting eggs varied greatly among the studied populations. Eighteen populations (HG, XT, YGH, YC, JYH, AQK, ZD, CAK, CN1, CN2, ALY, GZ, KXC, LGC, GSL, EBT, BYL and BOR) exhibited a singlepeak distribution pattern (Figs.1B' – G', K', M' – S', U', W' – Y'). The other seven populations (JZ, EBN, BRK, DBC, GH, DXC, WAS) showed a multiple-peak or a non-peaked distribution pattern (Figs.1A', H' – J', L', T', V'), and resting eggs of these populations usually had wider ranges in the distribution of 'apparent specific weight'.

3.2 Biometrical Parameters of Resting EggsThe largest diameter of intact eggs was recorded for GZ (356.8 µm ± 16.2 µm), followed by LGC (347.4 µm ± 22.7 µm), AQK (325.4 µm ± 13.7 μm) and JYH (322.2 µm ± 16.6 μm), while the smallest value was in YC (233.8 µm ± 10.2 µm). For decapsulated eggs, LGC possessed the largest diameter (336.8 µm ± 21.7 µm), while the smallest diameters were found in YC (216.6 µm ± 12.8 µm) population (Table 2). Values of chorion thickness ranged from 1.5 µm (JZ) to 13.4 µm (JYH) (Table 2).

The average dry weight of intact eggs ranged from 2.6 μg (GSL) to 9.2 μg (LGC), that of decapsulated eggs varied from 1.6 μg (GSL) to 8.2 μg (LGC). The lightest chorion was recorded for JZ (0.3 μg), while the heaviest chorion was seen in AQK (2.9 μg) (Table 2).

3.3 Correlation AnalysisCorrelation analyses did not show any significant correlation (P > 0.05) between FS50 and the dry weight of intact eggs (Fig.2A), between FS50 and the weight percentage of chorion in intact eggs (Fig.2B), as well as between FS50 and the volume of resting eggs (Fig.2C). However, significant negative correlations were detected between FS50 and chorion thickness (R2 = 0.2486, P = 0.0112) (Fig.2D), and between FS50 and the volume percentage of chorion in intact eggs (R2 = 0.2660, P = 0.0083) (Fig.2E). Their relationship could be expressed by y = −8.40x + 133.39 (Fig.2D) and y = −472.34x + 141.47 (Fig.2E), respectively.

|

Fig. 2 Relationships between FS50 and selected biometric parameters of Artemia resting eggs. The indeterminable FS50 of ZD and YC populations (see Table 2) are set to be 0. |

A positive correlation was found between FS50 and habitat salinity (R2 = 0.2920, P = 0.0307). Their relationship could be expressed as y = 0.78x − 23.80 (Fig.3A). There seemed to be a negative relationship between habitat salinity and the dry weight of intact eggs, though the relationship is not statistically significant (P = 0.1121; Fig.3B).

|

Fig. 3 Relationships between habitat salinity and the FS50 of Artemia resting eggs (A), and between habitat salinity and the dry weight of intact eggs (B). The indeterminable FS50 of ZD and YC populations (see Table 2) are set to be 0. |

Present results show that the buoyancy or the 'apparent specific weight' of Artemia resting eggs varies greatly among different populations (Fig.1). The FS50 of ZD and YC population is not detectable because over 50% of resting eggs float in distilled water, while it is as high as 234.5 for DBC population (Table 2). Eimanifar et al. (2006) documented that floating eggs of A. urmiana had higher haplotype diversity and nucleotide diversity than sinking eggs. Sura and Belovsky (2016) found that the percentage of floating resting eggs produced by floater parents (hatched from floating eggs) was 2.1 times higher than that of the eggs produced by sinker parents (hatched from sinking eggs). Both studies suggested that the buoyancy of resting eggs might have some kind of genetic component. Hence, the remarkable difference in the resting egg buoyancy among populations may be (at least partly) explained by the difference of their genetic basis. Moreover, among the 10 bisexual populations, only DXC (10.0%) shows a multi-peak distribution in the 'apparent specific weight' (Fig.1T'), while in the 13 parthenogenetic populations, 38.5% (EBN, BRK, DBC, GH and WAS) have a multi-peak distribution (Figs. 1H' – J', L', V'), suggesting that parthenogenetic populations seem to have higher diversity in the 'apparent specific weight' of resting eggs. This may be related to the different ploidies and different clones that each parthenogenetic population has. However, non-genetic factors may also affect the floating capacity of resting eggs, e.g., it can be affected by the food condition of parents (Sura and Belovsky, 2016; see Introduction).

For most (of the 16) populations with habitat salinity available (Table 1), there are some resting eggs that cannot float in their habitat salinity. For instance, percentages of resting eggs floating in their habitat salinity are 89.5%, 95.1%, 23.0%, 52.1%, 22.5%, 76.8%, 95.7%, 64.0%, 94.4%, 42.5% for JYH, AQK, EBN, BRK, DBC, GH, KXC, LGC, DXC and WAS populations, respectively (Figs.1F – J, L, R‒ T, V). This is perhaps because these samples (except for BRK) were collected from coastal waters, where sinking resting eggs deposited in the sediment might have been suspended by waves and catching activities (DBC sample containing resting eggs that were forced to the shore by wind and waves). Resting eggs of BRK were collected from open waters with a boat, but might also contain eggs suspended from the sediment, because this lake is only 0.3 – 0.8 m in depth and is prevailing with northwest wind (Ren et al., 1996). Resting eggs of YC, ZD, GSL, EBT, BYL and BOR were almost completely floating at their respective habitat salinity (Figs.1E, K, U, W – Y). Eggs of ZD, BOR, EBT and YC were collected along the shoreline. For these lakes, more than 99% eggs float at a lower-than-habitat salinity (60, 60, 140 and 140, respectively; Fig.1), suggesting that few resting eggs are sinking in their natural habitat. For GSL and BYL populations, unfortunately, we do not have the information about the collecting method of the samples.

No significant correlation is found between the FS50 and the dry weight of resting eggs (Fig.2A), between the FS50 and the volume of intact resting eggs (Fig.2B), and between FS50 and the weight percentage of chorion in intact eggs (Fig.2C). On the contrary, a significant negative correlation is found between FS50 and the thickness of chorion (Fig.2D), and between FS50 and the volume percentage of chorion in intact eggs (Fig.2E). These results provide a statistical support to a previous conclusion that the buoyancy of resting eggs is largely determined by the chorion thickness. For instance, the absence of floating capacity in resting eggs of A. monica is thought to be owing to their thin shell (Drinkwater and Crowe, 1991). Resting eggs of A. franciscana have a greater floating capacity than eggs of A. urmiana, because the egg shell of A. urmiana has a thinner alveolar layer than that of A. franciscana (Sorgeloos, 1997; Abatzopoulos et al., 2006).

Baitchorov and Nagorskaja (1999) reported a positive correlation between the dry weight of resting eggs and habitat salinity, but this is not supported by the present study (Fig.3B). The difference in results of these two studies is likely because different populations are studied. Samples of Baitchorov and Nagorskaja (1999) were collected from Crimea, Kazakhstan and Altai area, while the present study included some Qinghai-Tibet Plateau populations with altitudes over 4200 m above sea level. These high altitude populations (e.g., LGC, JYH, AQK) have remarkably bigger size and weight (Table 2). Since the habitat salinities of these populations are not higher than most other Artemia habitats, their large egg size is apparently not induced by high salinity. It is perhaps relative to their cold habitat climate (Van Stappen et al., 2003).

A recent study demonstrated that the selective harvesting against floating resting eggs in the Great Salt Lake had caused a decrease of resting egg buoyancy during 1991 to 2011 (Sura and Belovsky, 2016), suggesting that selective evolution of resting egg buoyancy could occur within a relatively short period. Present analysis shows a positive relationship between FS50 and habitat salinity (Fig.3A). This seems to support the hypothesis that lower salinity may induce a selective evolution toward producing resting eggs with better floating capacity, while higher salinity induces an evolution toward producing heavier resting eggs. However, this hypothesis need to be further tested because of the following reasons. 1) The salinity of some lakes has considerable fluctuation among years/seasons, and for some lakes the existing salinity records are few and may be bias towards certain seasons/years. 2) In addition to genetic selection, phenotypic plasticity induced by the site salinity as well as other factors may also influence the buoyancy of resting eggs. 3) The resting egg bank of a population may be composed of both floating and sinking eggs, to what extent a resting egg sample can represent the natural egg bank may be dependent on the collecting method (see above). For DBC population, Ren et al. (1996) reported that the salinity to float resting eggs was 140 – 175, while it was 180– 320 in the present study (Fig.1). Sampling methods may be a reason for such big difference in results of the two studies, though there may be also other reasons such as the change of salinity between sampling years. 4) A higher fraction of heavier resting eggs may be collected in a higher salinity season than that in a lower salinity season. For instance, Litvinenko et al. (2016) found that at a salinity of more than 180 g L−1, the number of benthic resting eggs decreased and the number of planktonic resting eggs increased in some Siberian populations, which was probably due to the improvement of their buoyancy at high salinity. Unfortunately, it is almost impossible to collect samples from water body and/or upper sediment properly representing the resting egg bank of a lake, not only because the sediment may contain eggs deposited in years, but also because the distribution of floating resting eggs is very uneven at the water surface.

In conclusion, the floating capacity and the distribution pattern of the 'apparent specific weight' of resting eggs vary greatly among different Artemia populations. The chorion of the resting egg is a major structure that provides the buoyancy of resting eggs. Habitat salinity seems to be an environmental factor inducing directional selection on the buoyancy of resting eggs, with Artemia living in lower salinity waters tending to produce lighter resting eggs and vice versa. However, this hypothesis needs to be further tested by more intensive and ingenious samplings.

AcknowledgementsThis study is supported by the Science and Technology Project of Tibet Autonomous Region (Nos. XZ201703GB-04, XZ202102YD0022C), and the Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2020C26008). We are grateful to Ms. Bakytgul Ospan, Mr. Jianbao Liu, Mr. Hongjun Zhang, Mr. Liwei Luan, Mr. Dian'an Zhang, Mr. Rongchang Tian and Mr. Pengfei Wang for providing samples of resting eggs and the collecting information of some samples. We thank Miss Ran Gao for her help in the experiment. We also thank Prof. Zengjun Du for clarifying the determination time of salinities reported by Sang (2018).

Abatzopoulos, T. J., Baxevanis, A. D., Triantaphyllidis, G. V., Criel, G., Pador, E. L., Van Stappen, G., et al., 2006. Quality evaluation of Artemia urmiana Günther (Urmia Lake, Iran) with special emphasis on its particular cyst characteristics (International study on Artemia LXIX). Aquaculture, 254(1): 442-454. (  0) 0) |

Abatzopoulos, T. J., Kastritsis, C. D., and Triantaphyllidis, C. D., 1986. A study of karyotypes and heterochromatic associations in Artemia, with special reference to two N.Greek populations. Genetica, 71(1): 3-10. (  0) 0) |

Abatzopoulos, T. J., Zhang, B., and Sorgeloos, P., 1998. Artemia tibetiana: Preliminary characterization of a new Artemia species found in Tibet (People's Republic of China).International study on Artemia. LIX. International Journal of Salt Lake Research, 7(1): 41-44. (  0) 0) |

Arashkevich, E. G., Sapozhnikov, P. V., Soloviov, K. A., Kudyshkin, T. V., and Zavialov, P. O., 2009. Artemia parthenogenetica (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) from the Large Aral Sea: Abundance, distribution, population structure and cyst production. Journal of Marine Systems, 76(3): 359-366. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2008.03.015 (  0) 0) |

Asem, A., and Sun, S. C., 2014. Biometric characterization of Chinese parthenogenetic Artemia (Crustacea: Anostraca) cysts, focusing on its relationship with ploidy and habitat altitude. NorthWestern Journal of Zoology, 10(1): 149-157. (  0) 0) |

Asem, A., Eimanifar, A., and Sun, S. C., 2016. Genetic variation and evolutionary origins of parthenogenetic Artemia (Crustacea: Anostraca) with different ploidies. Zoologica Scripta, 45(4): 421-436. DOI:10.1111/zsc.12162 (  0) 0) |

Asem, A., Eimanifar, A., Rastegar-Pouyani, N., Hontoria, F., De Vos, S., Van Stappen, G., et al., 2020. An overview on the nomenclatural and phylogenetic problems of native Asian brine shrimps of the genus Artemia Leach, 1819 (Crustacea, Anostraca). ZooKeys, 902(2): 1-15. (  0) 0) |

Baitchorov, V. M., and Nagorskaja, L. L., 1999. The reproductive characteristics of Artemia in habitats of different salinity. International Journal of Salt Lake Research, 8(4): 287-291. (  0) 0) |

Chang, M. S., Asem, A., and Sun, S. C., 2017. The incidence of rare males in seven parthenogenetic Artemia (Crustacea: Anostraca) populations. Turkish Journal of Zoology, 41: 138-143. DOI:10.3906/zoo-1512-67 (  0) 0) |

Clegg, J. S., and Conte, F. P., 1980. A review of the cellular and developmental biology of Artemia. In: The Brine Shrimp Artemia, Volume 2, Physiology, Biochemistry, Molecular Biology. Persoone, G., et al., eds., Universa Press, Wetteren, 211-254.

(  0) 0) |

Drinkwater, L. E., and Crowe, J. H., 1991. Hydration state, metabolism, and hatching of Mono Lake Artemia resting eggs. Biological Bulletin, 180(3): 432-439. DOI:10.2307/1542343 (  0) 0) |

Eimanifar, A., Rezvani, S., and Carapetian, J., 2006. Genetic differentiation of Artemia urmiana from various ecological populations of Urmia Lake assessed by PCR amplified RFLP analysis. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 333(2): 275-285. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2006.01.002 (  0) 0) |

Gilbert, J. J., 2017. Resting-egg hatching and early population development in rotifers: A review and a hypothesis for differences between shallow and deep waters. Hydrobiologia, 796(1): 235-243. DOI:10.1007/s10750-016-2867-7 (  0) 0) |

Lavens, P., and Sorgeloos, P., 1987. The cryptobiotic state of Artemia resting eggs, its diapause deactivation and hatching: A review. In: Artemia Research and Its Applications, Volume 2, Metabolism and Development, Enzymes Related to Nucleotide and Metabolism, Genome Structure and Expression. Decleir, W., et al., eds., Universa Press, Wetteren, Belgium, 27-64.

(  0) 0) |

Lenz, P. H., 1980. Ecology of an alkali-adapted variety of Artemia from Mono Lake, California, USA. In: The Brine Shrimp Artemia, Volume 3, Ecology, Culturing, Use in Aquaculture. Persoone, G., et al., eds., Universa Press, Wetteren, Belgium, 79-96.

(  0) 0) |

Leonova, G. A., Bobrov, V. A., Bogush, A. A., Bychinskii, V. A., and Anoshin, G. N., 2007. Geochemical characteristics of the modern state of salt lakes in Altai Krai. Geochemistry International, 45(10): 1025-1039. DOI:10.1134/S0016702907100060 (  0) 0) |

Li, W. H., 1988. Hydrochemical characteristics and water quality evaluation of Altun Mountain Nature Reserve. Xinjiang Environmental Protection, 1988(1): 13-16 (in Chinese). (  0) 0) |

Liang, K. Y., 1987. The salt lake and its geological and hydrogeological conditions in Xinjiang. Arid Zone Research, 1987(1): 3-10 (in Chinese). (  0) 0) |

Litvinenko, L. I., Litvinenko, A. I., and Boiko, E. G., 2016. Brine Shrimp Artemia in Western Siberia Lakes. Siberian Publishing Company 'Nauka', Novosibirsk: 295pp. (  0) 0) |

Liu, C. S., and Wang, H. Y., 1995. The bait analysis on Artemia sinica in saltlake at Shanxi Yuncheng. Journal of Shanxi Teacher's University, 9(1): 36-38 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Liu, J. Y., Zheng, M. P., and Luo, J., 1998. Study of Artemia in Lagkor Co, Tibet, I: Biological feature. Journal of Lake Sciences, 10(002): 92-96 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.18307/1998.0215 (  0) 0) |

Liu, S. S., Liu, X. F., Jia, Q. X., Kong, F. J., Zheng, M. P., and Lü, G. J., 2014. Assessment of spatial distribution and cysts resources of Artemia in late autumn in Dangxiong Co salt lake. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 34(1): 26-33. DOI:10.1016/j.chnaes.2013.11.004 (  0) 0) |

Ma, L., and Wang, W., 2003. Comparison of the biological characteristics of two Artemia populations from Aqikekule Lake and Gahai Lake. Marine Sciences, 27(11): 34-37 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Ma, Z. Z., 1995. Preliminary studies on algae in salt pans and saline lakes of northern China. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 26(3): 317-322 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Makkaveev, P. N., and Stunzhas, P. A., 2017. Salinity measurements in hyperhaline brines: A case study of the present Aral Sea. Oceanology, 57(6): 892-898. DOI:10.1134/S0001437017060091 (  0) 0) |

Mirabdullayev, I. M., Joldasova, I. M., Mustafaeva, Z. A., Kazakhbaev, S., Lyubimova, S. A., and Tashmukhamedov, B. A., 2004. Succession of the ecosystems of the Aral Sea during its transition from oligohaline to polyhaline water body. Journal of Marine Systems, 47(1): 101-107. (  0) 0) |

Mura, G., and Nagorskaya, L., 2005. Notes on the distribution of the genus Artemia in the former USSR countries. Journal of Biological Research, 4: 139-150. (  0) 0) |

Nambu, Z., Tanaka, S, and Nambu, F., 2004. Influence of photoperiod and temperature on reproductive mode in the brine shrimp, Artemia franciscana. Journal of Experimental Zoology, Part A. Comparative Experimental Biology, 301A (6): 542-546.

(  0) 0) |

Pan, Z. Q., Sun, J. H., Li, M. R., and Bian, B. Z., 1991. The biometrics of Artemia parthenogenetica from different localities in Shandong and Xinjiang. Transactions of Oceanology and Limnology, 1991(2): 62-69 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Proctor, V. W., 1964. Viability of crustacean eggs recovered from ducks. Ecology, 45(3): 656-658. DOI:10.2307/1936124 (  0) 0) |

Ren, M. L., Guo, Y., Wang, J. L., Su, R., Li, H., and Ren, B., 1996. Survey of Artemia Ecology and Resources in Inland Salt Lakes in Northwest China. Heilongjiang Science and Technology Press, Harbin: 260pp (in Chinese). (  0) 0) |

Sainz-Escudero, L., López-Estrada, E. K., Rodríguez-Flores, P. C., and García-París, M., 2021. Settling taxonomic and nomenclatural problems in brine shrimps, Artemia (Crustacea: Branchiopoda: Anostraca), by integrating mitogenomics, marker discordances and nomenclature rules. PeerJ, 9: e10865. DOI:10.7717/peerj.10865 (  0) 0) |

Sang, J., 2018. Analysis of bacterial diversity in Yuncheng Salt Lake and polyphasic taxonomy of four novel halophilic bacteria. Master thesis. Shandong University (Weihai) (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Sorgeloos, P., 1997. Determination and identification of biological characteristics of Artemia urmiana for application in aquaculture. In: The Lake Urmiah Cooperation Project. Sorgeloos, P., ed., Laboratory of Aquaculture and Artemia Reference Center, Belgium, 1-50.

(  0) 0) |

Sura, S. A., and Belovsky, G. E., 2016. Impacts of harvesting on brine shrimp (Artemia franciscana) in Great Salt Lake, Utah, USA. Ecological Applications, 26(2): 407-414. DOI:10.1890/15-0776 (  0) 0) |

Tachibana, A., Nomura, H., and Ishimaru, T., 2019. Impacts of longterm environmental variability on diapause phenology of coastal copepods in Tokyo Bay, Japan. Limnology and Oceanography, 64(1): S273-S283. (  0) 0) |

Triantaphyllidis, G. V., Abatzopoulos, T. J., and Sorgeloos, P., 1998. Review of the biogeography of the genus Artemia (Crustacea, Anostraca). Journal of Biogeography, 25(2): 213-226. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.252190.x (  0) 0) |

Van Stappen, G., 2002. Zoogeography. In: Artemia: Basic and Applied Biology. Abatzopoulos, T. J., et al., eds., Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 171-224.

(  0) 0) |

Van Stappen, G., Sui, L. Y., Hoa, V. N., Tamtin, M., Nyonje, B., De Medeiros Rocha, R., et al., 2020. Review on integrated production of the brine shrimp Artemia in solar salt ponds. Reviews in Aquaculture, 12(2): 1054-1071. DOI:10.1111/raq.12371 (  0) 0) |

Van Stappen, G., Sui, L. Y., Xin, N. H., and Sorgeloos, P., 2003. Characterisation of high-altitude Artemia populations from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, PR China. Hydrobiologia, 500: 179-192. DOI:10.1023/A:1024658604530 (  0) 0) |

Vanhaecke, P., Tackaert, W., and Sorgeloos, P., 1987. The biogeography of Artemia: An updated review. In: Artemia Research and Its Applications, Volume 1, Morphology, Genetics, Strain Characterization, Toxicology. Sorgeloos, P., et al., eds., Universa Press, Wetteren, 129-155.

(  0) 0) |

Wang, S. F., and Sun, S. C., 2007. Comparative observations on the cyst shells of seven Artemia strains from China. Microscopy Research and Technique, 70(8): 663-670. DOI:10.1002/jemt.20451 (  0) 0) |

Wang, S. M., and Dou, H. S. (chief eds.), 1998. Lakes in China. Science Press, Beijing: 580pp (in Chinese). (  0) 0) |

Wang, Z. C., Asem, A., Okazaki, R. K., and Sun, S. C., 2019. The critical stage for inducing oviparity and embryonic diapause in parthenogenetic Artemia (Crustacea: Anostraca): An experimental study. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 37(5): 1669-1677. DOI:10.1007/s00343-019-8322-7 (  0) 0) |

Wu, Q., Zheng, M. P., Nie, Z., and Bu, L. Z., 2012. Natural evaporation and crystallization regularity of Dangxiongcuo carbonate-type salt lake brine in Tibet. Chinese Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, 28(9): 1895-1903 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Xiao, Y. K., Shirodkar, P. V., Liu, W. G., Wang, Y. H., and Jin, L., 1999. Study on boron isotope geochemistry of salt lakes in Qaidam Basin, Qinghai. Progress in Natural Science, 9(7): 38-44 (in Chinese). (  0) 0) |

Xu, M. Q., Cao, H., Jia, Q. X., Gao, Y. R., and Chen, S. G., 2002. Preliminary study of plankton community diversity of the Gahai Salt Lake in the Qaidam Basin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Biodiversity Science, 10(1): 38-43 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang, G., Hou, L., and Cai, H. Y., 1996. Study on the karyotypes of four Artemia populations from salt lakes in China. Zoological Research, 17 (4): 489-493 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Yin, X. C., Yin, H., Zhou, K. X., Zhang, D. C., and Shi, J. P., 2001. Development and utilization of salt algae (Dunaliella salina) and brine shrimp (Artemia spp.) in the plateau salt lake of China. Journal of Salt Lake Research, 9(1): 4-8 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhang, R. S., Liu, F. Q., Zhao, X. X., and Zheng, J. Y., 1990. Studies on the chromosomal ploidy composition of the brine shrimp, Artemia spp. Acta Zoologica. Sinica, 36 (4): 412-419 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Zhang, R. X., Liao, L., Yin, C. T., and Guli, N., 2013. Isolation, antibacterial activity and growth characters of halophilic microorganisms from Dabancheng Salt Lake, Xinjiang. Biotech World, 10(7): 2-3 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zheng, M. P., Liu, X. F., and Zhao, W., 2007. Tectonogeochemical and biological aspects of salt lakes on the Tibetan Plateau. Acta Geologica Sinica, 81 (12): 1698-1708 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Zheng, M. P., Xiang, J., Wei, X. J., and Zheng, Y., 1989. Salt Lakes on Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. Beijing Science and Technology Press, Beijing, 431pp (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Zheng, X. Y., Zhang, M. G., Xu, C., and Li, B. X., 2002. An Overview of Salt Lakes in China. Science Press, Beijing, 415pp (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21