Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is a component of the solar radiation spectrum and can be divided into two bands at the Earth's surface, including UVA (wavelength, 320 – 400 nm) and UVB (wavelength, 280–320 nm). Excess UVR is considered a harmful environmental factor for living organisms (Rastogi and Sinha, 2009). It can damage many biological systems because it induces the formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in DNA, damages the photosynthetic apparatus, and decreases photosynthetic and growth rates (Villafañe et al., 2004). Moreover, as a consequence of ozone layer depletion, increased UVB levels can decrease primary productivity and alter phytoplankton population structures (Gao et al., 2007, Häder et al., 2015).

Marine benthic dinoflagellate assemblages are essential participants in marine ecosystems (Faust, 1991). Research on harmful benthic dinoflagellates, which produce toxins that can threaten the health of marine organisms and humans via the food chain (Mangialajo et al., 2008; Luo et al., 2017), has steadily increased over the last decade. As epiphytic or benthic species, these organisms are normally found on bottom substrates, such as rocks, macroalgae, corals, and seagrass, to which they attach and proliferate (Shears et al., 2009). The results of numerous field investigations indicate that benthic dinoflagellates are widely distributed in intertidal and subtidal zones where solar irradiance can vary from low levels to over 1000 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (Cohu and Lemée, 2012). Similar to other epiphytes, benthic dinoflagellates inevitably experience high light irradiance due to variations in solar irradiation, which can be attributed to column mixing, tidal changes, and diurnal variation. Toxin-producing benthic dinoflagellates are mainly distributed in temperate and tropical regions, where they undergo complex solar radiation exposure patterns (Gómez et al., 2005; Ferrier-Pagès et al., 2007).

Marine autotrophic organisms have evolved photoprotective mechanisms to resist photodamage from excess light and UVR. The non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) process is an effective photoprotective strategy that allows such organisms to dissipate excess light energy and protect their photosynthetic apparatus. NPQ dissipation is related to the activity of the xanthophyll cycle and achieved via de-epoxidation of photoprotective xanthophyll pigments, which, in dinoflagellates, are mainly diadinoxanthin and diatoxanthin (Briantais, 1994; Venn et al., 2006). Another photoprotective method commonly employed is the synthesis of ultraviolet-absorbing compounds (UVACs), which are mainly composed of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in marine algae (Sinha et al., 1998). These compounds have a high UVR extinction coefficient and a characteristic UV absorption peak of 310–360 nm (Banaszak et al., 2006). MAAs are involved in the resistance of autotrophic organisms to UVR damage and can be induced by high light or UVR levels (Taira and Taguchi, 2017). The inherent and induced contents of MAAs are species-specific. An investigation of over 110 marine algal species indicated that dinoflagellates and haptophytes exhibit higher MAA synthesis rates than other algal groups (Jeffrey et al., 1999).

Some researchers speculate that benthic dinoflagellates can synthesize high concentrations of UVACs to resist UV damage. Thus, in the present study, Prorocentrum lima, a globally distributed and toxic benthic dinoflagellate species (Nagahama et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2017), was selected to study the effects of different light and UVR intensities. The objective of this work is to understand the photoprotective mechanisms of harmful benthic dinoflagellates in response to excess light and UVR intensities.

2 Materials and MethodsP. lima (SD4) was isolated from Hainan Island, Hainan Province, China (Zhang et al., 2015), and cultured at the Research Center for Harmful Algae and Marine Biology, Jinan University. The strain was maintained at 25℃ in f/2 medium (Guillard and Ryther, 1962) under irradiation by a white light-emitting diode (LED) at 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 with a 12 h: 12 h light: dark period.

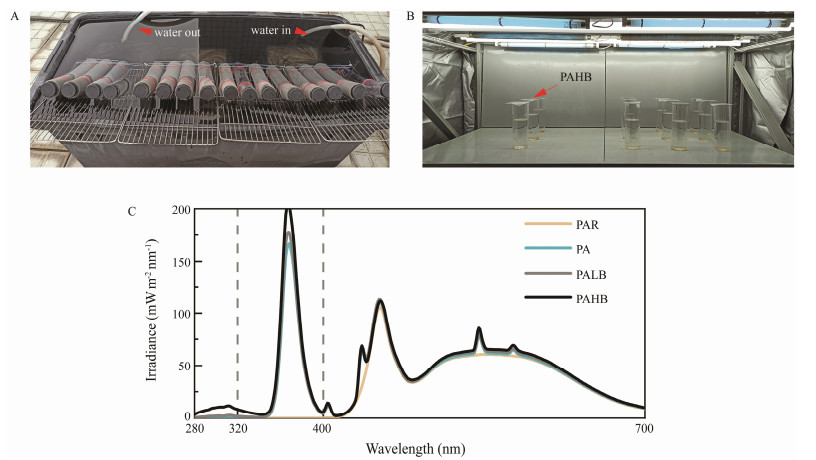

2.1 Outdoor ExperimentsAlgal cells in the exponential growth phase were diluted to 500 cells mL−1 in f/2 culture medium and placed into quartz tubes (diameter, 2 cm; height, 20 cm). Two irradiation treatments were then applied. In the first set of treatments, different light intensities (3%, 6%, 12%, 25%, 50%, and 100% solar radiation) were achieved by using different layers of neutral filters to cover the tubes (one layer reduces the light intensity in the treatment by approximately 50%). In the second set of treatments, different UVR intensities comprising three kinds of photosynthetic active radiation (PAR), PA (PAR + UVA), and PAB (PAR + UVA + UVB), were achieved using different cutoff filters. The tubes containing the algae were transferred to a control bath (Eyela, Japan) with circulating water at 25℃ ± 1℃ and cultured for 16 days (Fig. 1A).

|

Fig. 1 (A) In the outdoor culture, quartz tubes (diameter, 2 cm; height, 20 cm) containing P. lima were wrapped in different UV cutoff filters and neutral filters and immersed in a black water tank. The tank was connected to a control bath with circulating water for temperature control. The inlet and outlet water pipes are indicated by red arrows. Three such water tanks were used for the outdoor experiment. (B) In the indoor culture, P. lima was placed in quartz tubes (diameter, 4 cm; height, 20 cm) wrapped in different UV cutoff filters and cultured under artificial light. Two UVB lamps were wrapped by different layers of neutral filter to provide two levels of UVB irradiance. (C) Light spectra detected in the indoor cultures. UVA, UVB = ultraviolet A, ultraviolet B; PAR = photosynthetically active radiation; PA = PAR + UVA; PALB = PAR + UVA + UVB (0.05 W m−2); PAHB = PAR + UVA + UVB (0.3 W m−2). |

The algae were cultured at 25℃ indoors for 18 d with exposure to PAR (100 μmol photons m−2 s−1), PA (PAR + UVA, UAV = 4.2 W m−2 or 21 μmol photons m−2 s−1), PALB (PA + low UVB, UVB = 0.05 W m−2 or 0.25 μmol photons m−2 s−1), or PAHB (PA + high UVB, UVB = 0.3 W m−2 or 1.5 μmol photons m−2 s−1) to clarify the effects of UVB on P. lima (Fig. 1B). The PAR, UVA, and UVB light sources were LED (Opple, China), TL-D (Philips, Germany), and G15TBE (Sankyo Denki, Japan), respectively. The spectrum of each treatment was measured by a spectrometer (Hopoocolor, China; Fig. 1C).

2.3 Solar Irradiance and UVR TreatmentsThe outdoor cultures received solar radiation and were monitored by QSI2100 (Biospherical Instruments Inc., USA) and PMA2100 (Solar Light, USA) devices, which recorded solar PAR, UVA, and UVB levels every 1 or 5 min. Different cutoff filters were used for the UVR treatments: 1) PAR – the quartz tubes were covered with 395 nm cutoff filters (Ultraphan, Digefra, Munich, Germany) transmitting wavelengths > 395 nm; 2) PA – the quartz tubes were covered with 320 nm cutoff filters (Montagefolie, Folex, Dreieich, Germany) transmitting wavelengths > 320 nm; and 3) PAB – the quartz tubes were covered with 295 nm cutoff filters (Ultraphan, Digefra) transmitting wavelengths > 295 nm.

2.4 Measurement of Specific Growth RatesThe samples were fixed with Lugo's solution, and the cell numbers were counted under an optical microscope (CX31, Olympus, Japan). The growth rate (μ) was calculated as follows:

| $ \mu=\ln \left(C_{n} / C_{0}\right) /\left(t_{n}-t_{0}\right), $ |

where Cn and C0 represent the final and initial cell concentrations (cells mL−1), respectively. The μ of each treatment was measured in sextuplicate.

2.5 Measurement of UVAC and Pigment ConcentrationsExactly 15 mL of cell culture medium was obtained before and after the treatments and filtered through Whatman GF/F filters. The filtrates were extracted by methanol (3 mL) overnight at 4℃ and then centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 × g (Eppendorf, Germany). Absorbance measurements of the supernatant were obtained within the wavelength range of 280 – 700 nm using a scanning spectrophotometer (U-3900, Hitachi, Japan). UVAC concentrations were expressed as the peak optical density at 310 – 370 nm (Dunlap and Yamamoto, 1995). Chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentrations were calculated following the method of Porra (2002). Pigment samples from the indoor experiments were extracted by acetone and measured by a high-performance liquid chromatographic system (Agilent 1100, USA) with a C18 column (4.6 mm, 180 mm; Waters, USA). Pigment separation was performed following the method of Barlow et al. (1993). Chlorophyll and carotenoids were detected by absorbance at 440 nm. Pigment peaks were identified by comparing their retention times with those of the standards.

2.6 Measurement of Damage and Recovery RatesAfter outdoor acclimation, the algal cultures were transferred to small quartz tubes (10 mL) at a density of less than 20 μg Chl a per mL and dark-adapted for 15 min. The tubes were then covered with filters to conduct P, PA, and PAB treatments. A 1200 W xenon lamp (HMI, Osram, Germany) was used as the UVR source. The lamp was adjusted to provide specific intensities of PAR (2000 μmol photons m−2 s−1), UVA (36 W m−2 or 180 μmol photons m−2 s−1), and UVB (5.2 W m−2 or 26 μmol photons m−2 s−1), which are similar to the corresponding intensities observed at noon on a sunny day. After 30 min of exposure to an artificial solar irradiance lamp, photochemical efficiency (Y') and NPQ were measured by a Phyto-PAM device (Walz, Germany) every 3 or 15 min, and the exposure–response curves (ERCs) were created. The ratio of Y' was calculated by dividing the Y'-value of different light intensities of solar irradiance (3%–50%) with the Y'-value of 100% solar irradiance (Guan and Li, 2017). The rate of UVR-induced damage to the photosynthetic apparatus (k, min−1) and corresponding repair rate (r, min−1) were estimated according to previous studies (Lesser et al., 1994) as follows:

| $ Y_{n}^{\prime} / Y_{0}{ }^{\prime}=r /(r+k)+k /(r+k) \times \exp (-(r+k) t) Y_{n}^{\prime}, $ |

where Yn' and Y0' are the Y'-values at time tn and t0, respectively.

2.7 Data AnalysisAll experiments were performed in triplicate. Differences among the treatments were tested by one-way ANOVA (Tukey's test) with SPSS 16.0. A confidence level of 95% was used in all analyses.

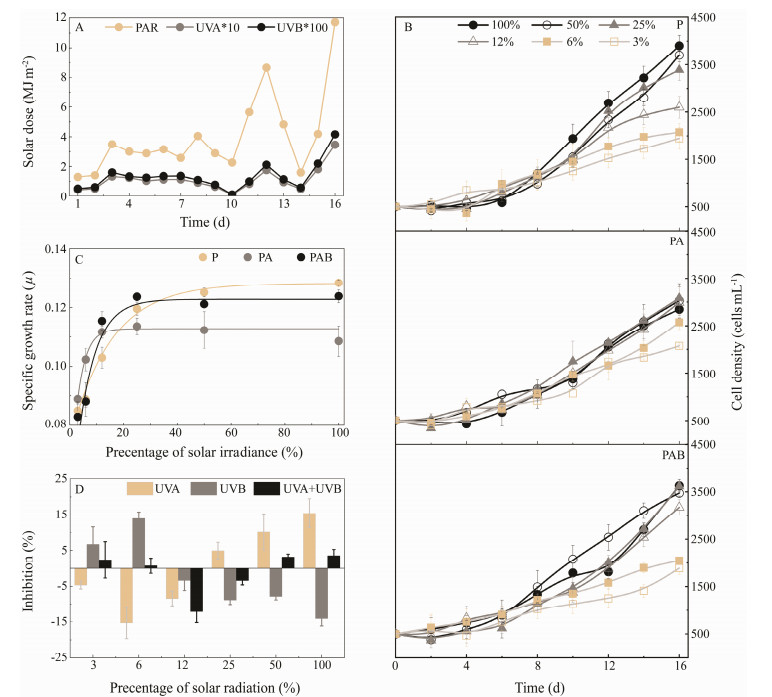

3 Results 3.1 Long-Term Effects of Different UVR and Solar Light IntensitiesDuring the 16 d of acclimation under solar irradiance, the average intensities of PAR, UVA, and UVB radiation were 475 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 2.52 W m−2 (12.6 μmol photons m−2 s−1), and 0.3 W m−2 (1.5 μmol photons m−2 s−1), respectively. Two phases were defined according to the weather conditions during the experiment. Phase 1, which included the first 20 d, represented rainy or cloudy conditions and featured a relatively low level of solar irradiance, as shown in Fig. 2A. The relative cell densities observed among the different treatments were similar in this phase (shown in Fig. 1B). The doses of solar irradiance in Phase 2, which included days 11–16 of the experiment, were approximately 2 – 4 times higher than the average values in Phase 1 (Fig. 2A). Rapid growth and variations in cell densities among the different treatments were observed in Phase 2 (Fig. 2B).

|

Fig. 2 (A) Doses of solar radiation of PAR (400 – 700 nm), UVA (320–400 nm) and UVB (280 – 320 nm) during the 16-d experiment. (B) Cell density throughout the experiments under different light intensities (3% – 100% solar light) and different UVR exposures (PAR, PA, PAB). (C) Specific growth rate (μ) of PAR, PA and PAB on day 16 as a function of acclimated light intensity (3% – 100% solar irradiance). (D) Inhibition of different UV wavebands (UVA, UVB, and UVA + UVB) on μ under different acclimated light intensities. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations (n = 6). PAR means photosynthetically active radiation; PA means PAR with UVA, PAB means PAR with UVA and UVB, UV means ultraviolet. |

The relationships between μ and percentage of solar irradiance under the conditions of P, PA, and PAB were calculated with formula y = a + b × exp (c × x). In all cases, the formula fit the relationship (R2 > 0.95, Fig. 2C). The initial slopes of the curves under PA (0.0070 ± 0.0007) and PAB (0.0065 ± 0.0005) were higher than that under P (0.0029 ± 0.0002; P < 0.05, Fig. 2C).

Under 3% – 12% solar irradiance, which is lower than the light saturation point, UVA negatively inhibited algal growth, indicating that UVA radiation enhances growth under lightlimited conditions (Fig. 2D). With light intensities > 12% solar irradiance, UVA positively whereas UVB negatively affected the algal growth (Fig. 2D). This finding suggests that UVA inhibits algal growth whereas UVB may moderate this inhibition under high solar irradiance.

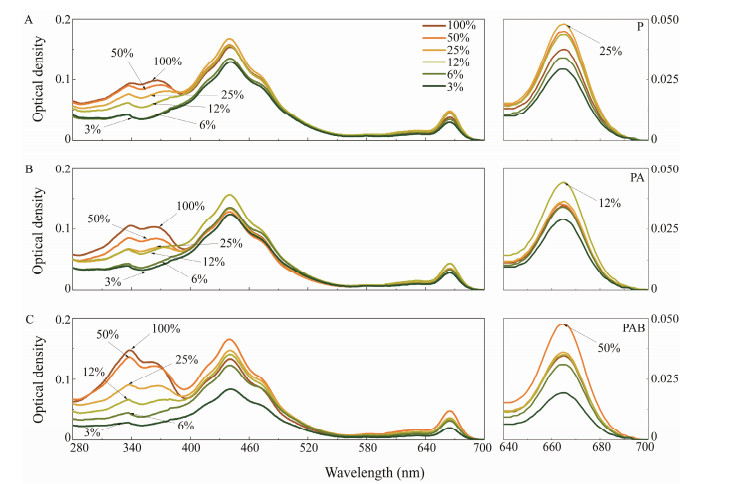

As shown in Fig. 3, photosynthetic pigments wavelengths of 640 – 700 nm with a peak at 665 nm. The highest optical densities at 665 nm in the P, PA, and PAB treatments occurred at solar irradiances of 25%, 12%, and 50%, respectively. Absorption by UVACs occurred at wavelengths of 280 – 400 nm with peaks at 334 and 365 nm. The optical densities of UVACs under the P, PA, and PAB treatments consistently increased according to the percentage of solar irradiance.

|

Fig. 3 Spectral absorption characteristics after 16 days of acclimation to various light intensities under the (A) PAR, (B) PA, and (C) PAB treatments. PAR = photosynthetically active radiation, PA means PAR with UVA, PAB means PAR with UVA and UVB, UV = ultraviolet. |

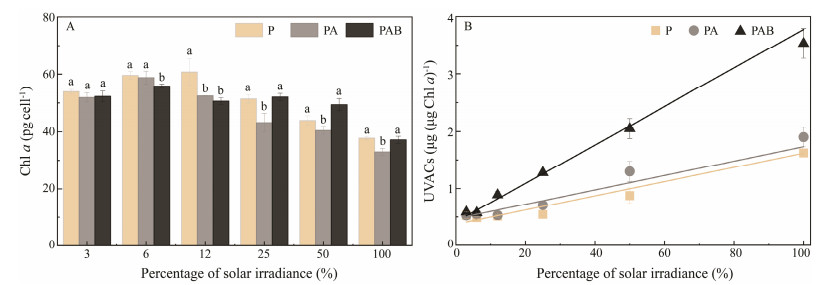

Fig. 4A illustrates the relationship between Chl a and UVACs and the percentage of solar irradiance under different UVR treatments. When the light intensities were > 12% solar irradiance, the cellular contents of Chl a under the PA treatment were all lower than those under the P and PAB treatments (P < 0.05) and no significant difference between P and PAB was found (P < 0.05). Associations between the contents of UVACs and percentage of solar irradiance under different UVR treatments were fitted using linear equations (R2 > 0.95, Fig. 4B). The slope of the PAB model (0.034 ± 0.002) was approximately three times greater than those of the PA (0.013 ± 0.002) and PAR (0.012 ± 0.001) models, which indicates that UVB may be the main radiation band inducing the synthesis of UVACs.

|

Fig. 4 Effect of different UVR and solar light intensities on the contents of (A) Chl a and (B) UVACs. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). Different lowercase letters between two bars indicate a statistical difference within treatments. Chl a means chlorophyll a; UVACs means ultraviolet-absorbing compounds; PAR means photosynthetically active radiation; PA means PAR with UVA, PAB means PAR with UVA and UVB, UV means ultraviolet. |

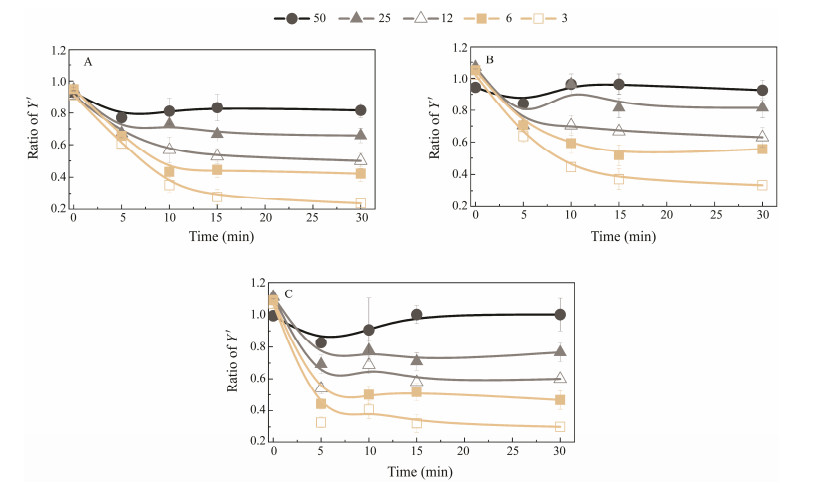

As shown in Fig. 5, the Y'-value ratio and solar irradiance percentage were positively correlated, suggesting that photoacclimation occurs within the 16-day treatment period. P. lima samples grown at 100% solar irradiance under different UVR treatments (P, PA, or PAB) showed lower decreases in effective photochemical efficiency than those grown at other solar irradiance percentages (3%–50%). In addition, the ratio of Y'-values at other light intensities to that at 100% solar irradiance was less than 1 at most points of time.

|

Fig. 5 Plots of the effective photochemical efficiency (Y') ratio of X to Y' under 100% solar irradiance. X indicates the ratio of Y' at solar irradiances of 50%, 25%, 12%, 6%, and 3%. Y' ratios for the (A) PAR, (B) PA, and (C) PAB treatments. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations (n = 6). PAR means photosynthetically active radiation; PA means PAR with UVA, PAB means PAR with UVA and UVB, UV means ultraviolet. |

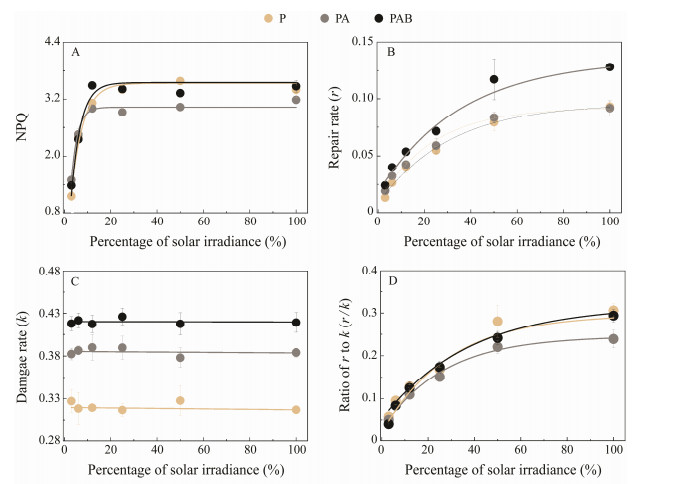

The relationship between NPQ and light intensity was fitted by an exponential equation (R2 > 0.95, Fig. 6A). NPQ values remained steady at solar irradiances greater than 25%. The NPQ values of the P and PAB treatments were significantly higher than that of PA when solar irradiance intensities were > 25% (P < 0.05).

|

Fig. 6 Plots of (A) NPQ, (B) repair rate (r, min−1), (C) damage rate (k, min−1), and (D) r/k ratio under the PAR, PA, and PAB treatments with artificial light exposure as a function of the acclimated light intensity. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations (n = 6). NPQ means non-photochemical quenching; PAR means photosynthetically active radiation; PA means PARwith UVA, PAB means PAR with UVA and UVB, UV means ultraviolet. |

The k and corresponding r of each treatment were estimated according to the ERCs (Figs. 6B, C). The results showed that different levels of solar irradiance do not affect k under different UVR treatments (P > 0.05, Fig. 6C). By contrast, the r values observed at solar irradiances of 50% and 100% under the PA treatment were significantly lower than those under the P and PAB treatments (P < 0.05, Fig. 6B). Thus, the ratio of r to k (r/k) with 100% irradiance under the PA treatment was significantly lower than those under the P and PAB treatments (P < 0.05, Fig. 6D).

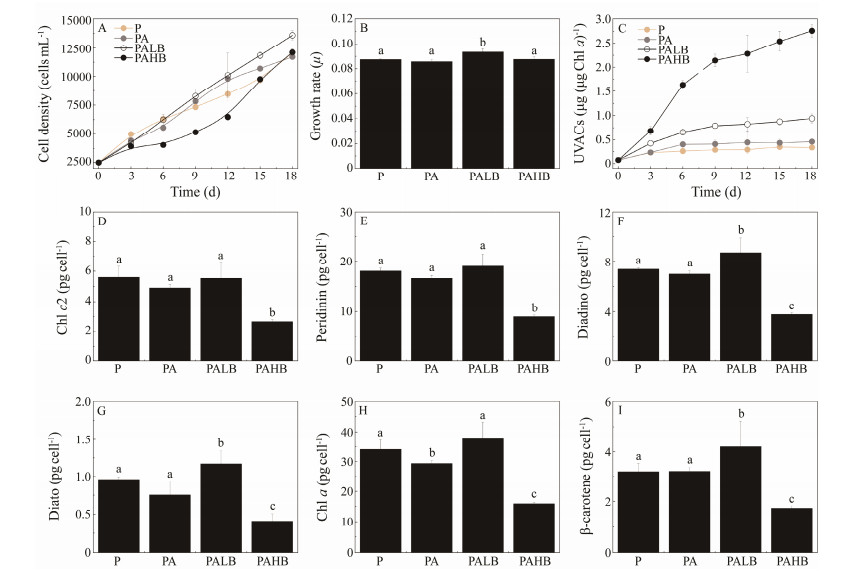

3.3 Evidence of the Effect of UVR on Indoor AcclimationDuring indoor acclimation, the cell densities in the PA treatment were significantly higher than those in PAR on days 12 and 15 (P < 0.05, Fig. 7A), confirming that UVA addition can enhance the growth of P. lima. The highest cell density and growth rate were observed under low UVB addition (PALB; Figs. 7A, B). The growth rate under PAHB was not significantly different compared with that under PAR (Fig. 7B). No difference in cell density for PAHB was noted between days 3 and 6. Then, following day 6, the cell density increased (P > 0.05, Fig. 7A). Similar growth patterns were also observed with 100% PAB treatment during outdoor acclimation (Fig. 2B). In this experiment, samples showed growth stagnation from day 10 to day 12. After day 12, they showed growth acceleration with increasing solar dosage.

|

Fig. 7 (A) Cell densities, (B) growth rates, (C) UVAC contents, and (D – I) pigments accumulated in indoor conditions under PAR, PA, PALB, and PAHB treatments. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). Different lowercase letters between bars indicate a statistical difference within treatments. Diadino means diadinoxanthin; diato means diatoxanthin; UVACs means ultraviolet-absorbing compounds; PAR means photosynthetically active radiation; PA means PAR with UVA, PALB means PAR with UVA and low UVB (0.05 W m−2), PAHB means PAR with UVA and high UVB (0.3 W m−2), UV means ultraviolet. |

The concentration of UVACs in the PAHB treatment increased from 0.09 (day 0) to 1.63 μg μg−1 Chl a (day 6; Fig. 7C), which might result in the stagnation of growth of PAHB. The highest concentration of UVACs (2.76 μg μg−1 Chl a) among different UVR treatments was observed in PAHB on day 18. The concentration of UVACs under PALB (0.94 μg μg−1 Chl a) was significantly higher than those under PA (0.46 μg μg−1 Chl a) and PAR (0.35 μg μg−1 Chl a; P < 0.05). P. lima exposed to PALB revealed the highest contents of Chl a and photoprotective pigments, particularly diadinoxanthin (Fig. 7F), diatoxanthin (Fig. 7G), and β-carotene (Fig. 7I). The enhanced UVB (PAHB) treatment showed the lowest contents of pigments (P < 0.05, Figs. 7D–I).

4 DiscussionThe present study investigated the combined effects of light and UVR intensities on P. lima in the long- and short- term scales. The simulated conditions represented different vertical distributions of algae exposed to solar light, i.e., those occurring during low tide and at noon in intertidal flats. The results indicate that P. lima not only endures high solar irradiance and UVR, but also has a complex strategy for responding to or even benefiting from UVR.

UVA significantly enhanced the growth when solar light levels were < 12%, and significantly decreased the growth when solar light levels were > 12% (Fig. 2B). The positive effect of UVA on algal growth has been widely reported in several species, including Gracilaria lemaneiformis (Xu and Gao, 2010), Sargassum horneri (Guan et al., 2016), and Ulva olivascens and Fucus spiralis (Ehling-Schulz et al., 1997). Xu and Gao (2016) investigated macroalgae from different families and found that the majority of the species can utilize UVA for photosynthesis. However, in some situations UVA restrictions can accelerate the growth. It has been reported that the enhancements in UVA are common in limited-light conditions, such as cloudy days, and carbon fixation is mainly driven by longer UVA wavelengths (340–400 nm) (Mengelt and Prézelin, 2005). In the present study, because the UVA waveband used in the indoor experiments was 340 – 400 nm, growth under PA increased, even when the UVA irradiance was > 4 W m−2 (Fig. 1C).

Surprisingly, UVB addition significantly increased growth compared with that under PA with > 12% solar irradiance (Fig. 2B). UVB radiation is considered a negative factor in the growth and photosynthesis of photoautotrophic organisms. However, several assays have reported a beneficial effect of UVB radiation on the performance of photosynthesis. The marine brown alga Dictyota dichotoma, for example, exhibits low photosynthesis recovery rates under UVB depletion and high recovery rates under UVB after sunlight-induced photoinhibition (Flores-Moya et al., 1997). Another study suggested that UVB may be involved in the simultaneous impairment and recovery of photosynthesis (Flores-Moya et al., 1999). Enhancements in recovery induced by UVB have also been observed in several other macroalgae species, including seaweeds Gracilarica lemaneiformis (Rhodophyta) (Xu and Gao, 2010) and Zygnemopsis decussata (Chlorophyta) (Figueroa et al., 2009), freshwater macroalgae (Bautista-Saraiva et al., 2018), and other aquatic plants (Hanelt et al., 2006). Many studies have revealed that the most positive effects of UVB are on tropical and subtropical species that experience intense solar radiation exposure, indicating that the UVB strategy may be used to adapt to high solar irradiance. The P. lima strain in the present study was isolated from Hainan Province, which is located in a tropical region (Zhang et al., 2015).

UVB exposure promoted k and the corresponding r. Thus, the r/k ratio of P. lima under PAB is higher than that under PA in high-light exposure conditions. The r/k ratio represents the turnover rate of the D1 protein, which is the main UVR damage target protein and influences the activity of PSII and degree of photoinhibition in cells. Hanelt et al. (2006) reported that reductions in r under PA treatment cause the highest inhibition of Y' during high light exposure, which may be alleviated in cells acclimated by UVB addition. Greenberg et al. (1989) found that the turnover rate of the D1 protein under UVB exposure is higher than that measured under PAR illumination alone.

UVB may also play a role in stimulating and maintaining photoprotective compounds (Figueroa et al., 2009). Chl a and photoprotective pigments were readily degraded in the presence of UVA in both indoor and outdoor experiments (Figs. 4A and 7C). UVA had no significant effect on the ratio of UVACs to Chl a, suggesting that P. lima does not efficiently protect Chl a, the most important photosynthetic pigment, under UVA radiation. However, the contents of UVACs were significantly enhanced by UVB, indicating that UVB is the main UVAC induction band in P. lima. Moreover, the contents of diadinoxanthin and diatoxanthin, the main xanthophyll cycle pigments in dinoflagellates, were enhanced by low UVB in the indoor experiments. Xanthophyll pigments not only contribute to NPQ but may also help stabilize thylakoid chloroplasts and ROS quenching (Havaux and Niyoji, 1999; Brini, 2017). Acclimation under low doses of UVB promote the synthesis of β-carotene, which is known as an efficient antioxidant compound (Rakhimberdieva et al., 2004). Research indicates that the accumulation of β-carotene can prevent photosynthetic damage from UVA or blue light (White and Jahnke, 2002). The pigment results obtained in the present study support the hypothesis that low doses of UVB may stimulate the cellular photoprotective pathway to ameliorate the damage caused by UVR exposure.

The mechanism by which UVB facilitates the growth and photosynthesis of algae remains unknown. One possible mechanism might be related to the production of UVACs (mainly MAAs) under UVB enhancement. Growth rates are accelerated by high contents of UVACs, which implies that MAAs play a pivotal role in the growth of P. lima under UVR irradiance. High concentrations of MAAs in cells provide efficient photoprotection against UVR-induced damage. Approximately 30% of the photons striking the photosynthetic apparatus are reportedly restrained by MAAs in cyanobacteria (Garcia-Pichel et al., 1993). Taira and Taguchi (2017) applied several PAR radiation intensities and found different concentrations of MAAs in the cells of the dinoflagellate Scrippsiella sweeneyae. Extensive UVR-induced damage was observed under the condition of low MAA content induced by low PAR; by contrast, high UVR tolerance was observed in the presence of high MAA contents. On the other hand, MAAs may function as antenna compounds that capture UVR energy into the photosynthetic pathway. In the haptophyte Phaeocystis antarctica, some MAA species, such as shinorine, Gly, and mycosporine-Gly/Val, are able to transmit absorbed UVR energy to Chl a via the photosynthetic pathway (Moisan and Mitchell, 2001). Whether marine algae use short UV wavelengths (i.e., UVB) for photosynthesis is yet unclear (Neori et al., 1986; Holm-Hansen et al., 1993).

5 ConclusionsThis study confirmed that UVA and UVB have positive effects on P. lima and help the species accommodate different light conditions. When light is limited, P. lima can utilize UVA and UVB to supply extra energy for growth. Under intense light, P. lima may use UVB as a signal to induce greater photoprotection by increasing the contents of UVACs and photoprotective pigments, as well as enhancing the recovery rate required to reduce UVR damage.

AcknowledgementsThe work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41706126, 41876173 and 41606176).

List of AbbreviationsUV, Ultraviolet; UVA, ultraviolet A; UVB ultraviolet B; UVR, Ultraviolet radiation; PAR, photosynthetically active radiation; PA, PAR photosynthetically active radiation with ultraviolet A; PAB, photosynthetically active radiation with ultraviolet A and B; PALB, photosynthetically active radiation with ultraviolet A and low B; PAHB, photosynthetically active radiation with ultraviolet A and high B; Chl a, chlorophyll a; Chl c2, chlorophyll c2; UVAC, ultraviolet-absorping compound; NPQ, non-photochemical quenching; MAAs, mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs); Y', photochemical efficiency; ERCs, exposureresponse curves; k, damage rate; r, repair rate; Diato, diatoxanthin; Diadino, Diadinoxanthin.

Banaszak, A. T., Santos, M. G. B., LaJeunesse, T. C. and Lesser, M. P., 2006. The distribution of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) and the phylogenetic identity of symbiotic dinoflagellates in cnidarian hosts from the Mexican Caribbean. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 337(2): 131-146. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2006.06.014 (  0) 0) |

Barlow, R. G., Mantoura, R. F. C., Gough, M. A. and Fileman, T. W., 1993. Pigment signatures of the phytoplankton composition in the northeastern Atlantic during the 1990 spring bloom. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 40(1-2): 459-477. DOI:10.1016/0967-0645(93)90027-K (  0) 0) |

Briantais, J. M., 1994. Light-harvesting chlorophyll a-b complex requirement for regulation of Photosystem Ⅱ photochemistry by non-photochemical quenching. Photosynthesis Research, 40(3): 287-294. DOI:10.1007/BF00034778 (  0) 0) |

Brini, F., 2017. Photosynthesis under stressful environmental conditions: Existing challenges. In: Environment and Photosynthesis: A Future Prospect. Singh et al., eds., Studium Press, India, 68-91.

(  0) 0) |

Cohu, S. and Lemée, R., 2012. Vertical distribution of the toxic epibenthic dinoflagellates Ostreopsis cf. ovata, Prorocentrum lima and Coolia monotis in the NW Mediterranean Sea. CBM-Cahiers de Biologie Marine, 53(3): 373. (  0) 0) |

Dunlap, W. C. and Yamamoto, Y., 1995. Small-molecule antioxidants in marine organisms: Antioxidant activity of mycosporine-glycine. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 112(1): 105-114. DOI:10.1016/0305-0491(95)00086-N (  0) 0) |

Ehling-Schulz, M., Bilger, W. and Scherer, S., 1997. UV-B-induced synthesis of photoprotective pigments and extracellular polysaccharides in the terrestrial cyanobacterium Nostoc commue. Journal of Bacteriology, 179(6): 1940-1945. DOI:10.1128/jb.179.6.1940-1945.1997 (  0) 0) |

Faust, M. A., 1991. Morphology of ciguatera-causing Prorocentrum lima (Pyrrophyta) from widely differing sites. Journal of Phycology, 27(5): 642-648. DOI:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1991.00642.x (  0) 0) |

Ferrier-Pagès, C., Richard, C., Forcioli, D., Allemand, D. and Shick, M. P. M., 2007. Effects of temperature and UV radiation increases on the photosynthetic efficiency in four scleractinian coral species. The Biological Bulletin, 213(1): 76-87. DOI:10.2307/25066620 (  0) 0) |

Figueroa, F. L., Korbee, N., Carrillo, P., Medina-Sánchez, J. M., Mata, M. and Bonomi, J., 2009. The effects of UV radiation on photosynthesis estimated as chlorophyll fluorescence in Zygnemopsis decussata (Chlorophyta) growing in a high mountain lake (Sierra Nevada, Southern Spain). Journal of Limnology, 68(2): 206-216. DOI:10.4081/jlimnol.2009.206 (  0) 0) |

Flores-Moya, A., Hanelt, D., Figueroa, F. L., Altamirano, M., Viñegla, B. and Salles, S., 1999. Involvement of solar UV-B radiation in recovery of inhibited photosynthesis in the brown alga Dictyota dichotoma (Hudson) Lamouroux. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 49(2-3): 129-135. DOI:10.1016/S1011-1344(99)00046-9 (  0) 0) |

Gao, K., Li, G., Helbling, E. W. and Villafane, V. E., 2007. Variability of UVR effects on photosynthesis of summer phytoplankton assemblages from a tropical coastal area of the South China Sea. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 83(4): 802-809. DOI:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00154.x (  0) 0) |

Garcia-Pichel, F. and Castenholz, R. W., 1993. Occurrence of UV-absorbing, mycosporine-like compounds among cyanobacterial isolates and an estimate of their screening capacity. Apply Environmental Microbiology, 59(1): 163-169. DOI:10.1128/aem.59.1.163-169.1993 (  0) 0) |

Gómez, I., Figueroa, F. L., Huovinen, P., Ulloa, N. and Morales, V., 2005. Photosynthesis of the red alga Gracilaria chilensis under natural solar radiation in an estuary in southern Chile. Aquaculture, 244(1-4): 369-382. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.11.037 (  0) 0) |

Greenberg, B. M., Gaba, V., Canaani, O., Malkin, S., Mattoo, A. K. and Edelman, M., 1989. Separate photosensitizers mediate degradation of the 32-kDa photosystem Ⅱ reaction center protein in the visible and UV spectral regions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 86(17): 6617-6620. DOI:10.1073/pnas.86.17.6617 (  0) 0) |

Guan, W. C. and Li, P., 2017. Dependency of UVR-induced photoinhibition on atomic ratio of N to P in the dinoflagellate Karenia mikimotoi. Marine Biology, 164(2): 31. DOI:10.1007/s00227-016-3065-x (  0) 0) |

Guan, W. C., Chen, H., Wang, T. G., Chen, S. and Xu, J. T., 2016. Effect of the solar ultraviolet radiation on the growth and fluorescence parameters of Sargassum horneri. Journal of Fisheries of China, 40(1): 83-91 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Guillard, R. R. L. and Ryther, J. H., 1962. Study of marine planktonic diatoms: I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 8(2): 229-239. (  0) 0) |

Häder, D. P., Williamson, C. E., Wängberg, S. Å., Rautio, M., Rose, K. C. and Gao, K. S., 2015. Effects of UV radiation on aquatic ecosystems and interactions with other environmental factors. Photochemical and Photobiological Sciences, 14(1): 108-126. DOI:10.1039/C4PP90035A (  0) 0) |

Hanelt, D., Hawes, I. and Rae, R., 2006. Reduction of UV-B radiation causes an enhancement of photoinhibition in high light stressed aquatic plants from New Zealand lakes. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 84(2): 89-102. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.01.013 (  0) 0) |

Havaux, M. and Niyogi, K. K., 1999. The violaxanthin cycle protects plants from photooxidative damage by more than one mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 96(15): 8762-8767. DOI:10.1073/pnas.96.15.8762 (  0) 0) |

Holm-Hansen, O., Helbling, E. W. and Lubin, D., 1993. Ultraviolet radiation in Antarctica: Inhibition of primary production. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 58(4): 567-570. DOI:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1993.tb04933.x (  0) 0) |

Jeffrey, S. W., MacTavish, H. S., Dunlap, W. C., Vesk, M. and Groenewoud, K., 1999. Occurrence of UVA-and UVB-absorbing compounds in 152 species (206 strains) of marine microalgae. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 189: 35-51. DOI:10.3354/meps189035 (  0) 0) |

Lesser, M. P., Cullen, J. J. and Neale, P. J., 1994. Carbon uptake in a marine diatom during acute exposure to ultraviolet B radiation: Relative importance of damage and repair. Journal of Phycology, 30(2): 183-192. DOI:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1994.00183.x (  0) 0) |

Luo, Z., Zhang, H., Krock, B., Lu, S., Yang, W. and Gu, H., 2017. Morphology, molecular phylogeny and okadaic acid production of epibenthic Prorocentrum (Dinophyceae) species from the northern South China Sea. Algal Research, 22: 14-30. DOI:10.1016/j.algal.2016.11.020 (  0) 0) |

Mangialajo, L., Bertolotto, R., Cattaneo-Vietti, R., Chiantore, M., Grillo, C. and Lemee, R., 2008. The toxic benthic dinoflagellate Ostreopsis ovata: Quantification of proliferation along the coastline of Genoa, Italy. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 56(6): 1209-1214. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.02.028 (  0) 0) |

Mengelt, C. and Prézelin, B. B., 2005. UVA enhancement of carbon fixation and resilience to UV inhibition in the genus Pseudo-nitzschia may provide a competitive advantage in high UV surface waters. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 301: 81-93. DOI:10.3354/meps301081 (  0) 0) |

Moisan, T. A. and Mitchell, B. G., 2001. UV absorption by mycosporine-like amino acids in Phaeocystis antarctica Karsten induced by photosynthetically available radiation. Marine Biology, 138(1): 217-227. DOI:10.1007/s002270000424 (  0) 0) |

Nagahama, Y., Murray, S., Tomaru, A. and Fukuyo, Y., 2011. Species Boundaries in the toxic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima (Dinophyceae, Prorocentrales), based on morphological and phylogenetic characters. Journal of Plankton Research, 47(1): 178-189. (  0) 0) |

Neori, A., Vernet, M., Holm-Hansen, O. and Haxo, F. T., 1986. Relationship between action spectra for chlorophyll a fluorescence and photosynthetic O2 evolution in algae. Journal of Plankton Research, 8(3): 537-548. DOI:10.1093/plankt/8.3.537 (  0) 0) |

Porra, R. J., 2002. The chequered history of the development and use of simultaneous equations for the accurate determination of chlorophylls a and b. Photosynthesis Research, 73(1-3): 149-156. (  0) 0) |

Rakhimberdieva, M. G., Stadnichuk, I. N., Elanskaya, I. V. and Karapetyan, N. V., 2004. Carotenoid-induced quenching of the phycobilisome fluorescence in photosystem Ⅱ-deficient mutant of Synechocystis sp. FEBS Letters, 574(1-3): 85-88. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.087 (  0) 0) |

Rastogi, R. P. and Sinha, R. P., 2009. Biotechnological and industrial significance of cyanobacterial secondary metabolites. Biotechnology Advances, 27(4): 521-539. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.04.009 (  0) 0) |

Shears, N. T. and Ross, P. M., 2009. Blooms of benthic dinoflagellates of the genus Ostreopsis; An increasing and ecologically important phenomenon on temperate reefs in New Zealand and worldwide. Harmful Algae, 8(6): 916-925. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2009.05.003 (  0) 0) |

Sinha, R. P., Klisch, M., Gröniger, A. and Häder, D. P., 1998. Ultraviolet-absorbing/screening substances in cyanobacteria, phytoplankton and macroalgae. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 47(2-3): 83-94. DOI:10.1016/S1011-1344(98)00198-5 (  0) 0) |

Taira, H. and Taguchi, S., 2017. Cellular mycosporine-like amino acids protect photosystem Ⅱ of the Dinoflagellate Scrippsiella sweeneyae from ultraviolet radiation damage. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 174: 27-34. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.07.015 (  0) 0) |

Venn, A. A., Wilson, M. A., Trapidd-rosenthal, H. G., Keely, B. J. and Douglas, A. E., 2006. The impact of coral bleaching on the pigment profile of the symbiotic alga, Symbiodinium. Plant, Cell and Environment, 29(12): 2133-2142. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.001587.x (  0) 0) |

Villafañe, V. E., Buma, A. G., Boelen, P. and Helbling, E. W., 2004. Solar UVR-induced DNA damage and inhibition of photosynthesis in phytoplankton from Andean lakes of Argentina. Archiv für Hydrobiologie, 161(2): 245-266. DOI:10.1127/0003-9136/2004/0161-0245 (  0) 0) |

White, A. L and Jahnke, L. S., 2002. Contrasting effects of UV-A and UV-B on photosynthesis and photoprotection of betacarotene in two Dunaliella spp. Plant and Cell Physiology, 43(8): 877-884. DOI:10.1093/pcp/pcf105 (  0) 0) |

Xu, J. T. and Gao, K. S., 2010. Use of UV-A energy for photosynthesis in the red macroalga Gracilaria lemaneiformis. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 86(3): 580-585. DOI:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2010.00709.x (  0) 0) |

Xu, J. T. and Gao, K. S., 2016. Photosynthetic contribution of UV-A to carbon fixation by macroalgae. Phycologia, 55(3): 318-322. DOI:10.2216/15-91.1 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, H., Li, Y., Cen, J. Y., Wang, H. L., Cui, L., Dong, Y. L. and Lu, S. H., 2015. Morphotypes of Prorocentrum lima (Dinophyceae) from Hainan Island, South China Sea: Morphological and molecular characterization. Phycologia, 54(5): 503-516. DOI:10.2216/15-8.1 (  0) 0) |

2021, Vol. 20

2021, Vol. 20