2) Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266237, China;

3) National Engineering Research Center for Oceanic Fisheries, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, 201306, China;

4) Key Laboratory of Sustainable Exploitation of Oceanic Fisheries Resources, Ministry of Education, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, 201306, China;

5) Key Laboratory of Oceanic Fisheries Exploration, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Shanghai, 201306, China;

6) Scientific Observing and Experimental Station of Oceanic Fishery Resources, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Shanghai, 201306, China;

7) Marine Fisheries Research Institute of Zhejiang, Zhoushan, 316021, China

Ommastrephid squids are characterized by short lifecycle, rapid growth, early maturation, high migratory capacity, and complicated recruitment patterns (Boyle, 1990; Dunning and Wormuth, 1998; Rodhouse, 2008). Most squids inhabit in the waters of the shelf, slope, and open oceans, with the depths from the surface to 2000 m (Anderson and Rodhouse, 2001). Squids play a critical role in the marine food weds, serving as prey for large-size marine animals and predator for small-size fish and zooplankton (Cherel and Weimerskirch, 1995; Parry, 2006). Many squids are economically important and considered as the crucial commercial fishery target among global distant-water fisheries (Arkhipkin et al., 2015). Annual catches of Ommastrephid squids in the recent decade are over two million tons, accounting for about 50% of the cephalopod catches in the world (Chen et al., 2008). Among the Ommastrephid squids, the oceanic squid such as Japanese flying squid Todarodes pacificus in the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea and the westerns Pacific Ocean (Kang et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2019), the Nototodarus sloanii in New Zealand waters (Jackson et al., 2000), the neon flying squid Ommastrephes bartramii in the North Pacific Ocean (Bower and Ichii, 2005) and the jumbo flying squid Dosidicus gigas in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (Nigmatullin et al., 2001) are the most important species in terms of catches and economic values. The two latter squid specie are the main fishing targets by Chinese squid-jigging fisheries. Mainland China started to exploit O. bartramii in 1993 and D. gigas in 2001. Both catches accounted for a large amount of the total catches in China (Chen et al., 2008).

Ommastrephes bartramii is an abundant squid species widely distributed in the North Pacific Ocean (Bower and Ichii, 2005). The O. bartramii population includes two seasonal spawning cohorts: the winter-spring cohort and the autumn cohort. Each cohort has different geographical stocks (Chen and Chiu, 2003). The former cohort comprises the western and central-eastern stocks, and the latter cohort comprises the central and eastern stocks (Ma et al., 2011). Both cohorts perform south-to-north migration from the spawning ground in the subtropical front to the feeding ground in the subarctic domain. At present, O. bartramii is mainly captured by China (including Chinese Taipei) and Japan (Ichii et al., 2006). Mainland China targeted the western winter-spring cohort on the fishing ground between 35°–50°N and 150°–175°E (Chen et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2015). The annual catch in China accounts for more than 80% of the total catches of O. bartramii in the North Pacific Ocean (Chen et al., 2008).

For D. gigas, it is a large-size squid species widely distributed in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (Argüelles et al., 2001). This squid is largely utilized by hundreds of international squid-jigging fishing vessels from Asia-Pacific (e.g., China and Japan) and South America-Pacific countries (e.g., Peru and Chile) (Taipe et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2008). Most fishing operations occur at night, using powerful lamps attracting the squids. At present, four major fishing grounds are largely exploited in the Gulf of California, the offshore waters of the Costa Rica Dome, the high seas at the equator between 5°N–5°S and 130°– 90°W, and the coastal and oceanic regions off Peru and Chile (Hernández-Herrera et al., 1998; Waluda et al., 2004; Zeidberg and Robison, 2007; Morales-Bojórquez and Pacheco-Bedoya, 2016). In the Southern Hemisphere, the most abundant fishing grounds are located in the oceanic regions off Peru, which are mainly exploited by Chinese fishing vessels (Hu et al., 2019). The total catches of D. gigas from China are the highest and accounted for about 50% of the total catches in the world (Chen et al., 2008).

The yearly catch of O. bartramii and D. gigas from China is high; however, it tends to demonstrably fluctuate across years (Paulino et al., 2016; Igarashi et al., 2017). According to previous studies, one important reason causing the fluctuation is the climate-driven regional environmental changes on the fishing ground, which can strongly affect squid distribution and abundance (Igarashi et al., 2018; Frawley et al., 2019). Pelagic fishery enterprises from China have assigned hundreds of squid-jigging vessels into the Pacific Ocean to exploit O. bartramii and D. gigas. Without understanding the impacts of local environmental variability on squid abundance and distribution, or the cause of synchronous fluctuations in O. bartramii and D. gigas, the enterprises are difficult to decide where to fish and what the number of the fishing vessels should be assigned in the Northwest Pacific Ocean and in the Southeast Pacific Ocean. Thus, for more effective fisheries management, it is essential to examine the associations between the two squid species, especially the synchronous fluctuations in abundance and distribution in relation to the climatic and environmental factors.

In this study, catch per unit effort (CPUE) and the latitudinal gravity centers (LATG) of fishing effort were used to indicate squid abundance and distribution, respectively. The synchronous fluctuations in abundance and distribution of O. bartramii in the Northwest Pacific Ocean and D. gigas in the Southeast Pacific Ocean were investigated. The impacts of two Niño indices (i.e., Niño 3.4 and 1+2 region) and regional water surface temperature on the two squid species were further assessed. The purposes of this study were to 1) examine the synchronous fluctuations in CPUE and LATG between O. bartramii and D. gigas; 2) evaluate the impacts of environmental factors on variability of squid abundance and distribution; and 3) explore the possible cause that responsible for the observed synchronicity and provide some important implications for Chinese squid-jigging fisheries.

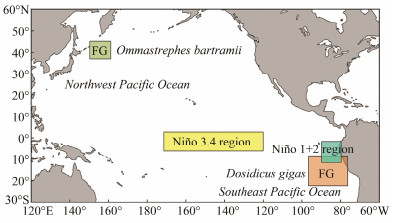

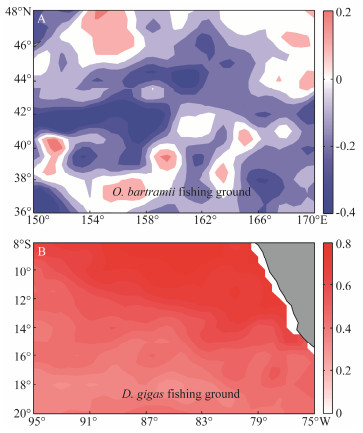

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Fisheries Data CollectionCommercial logbook data for Chinese O. bartramii and D. gigas squid-jigging fisheries grouped by 0.5°×0.5° grid cell and by month were obtained from the National Data Center for Distant-water fisheries of China, Shanghai Ocean University. The fishing months from September to November for both squids were the most important fishing seasons due to the extremely high squid abundance and catches. Thus, data from September to November during 2006–2015 were used in the analysis. The data contained fishing effort (days fished), the location of fishing ground (latitude and longitude in degrees) and catch (unit: tonnes). Fishing locations for the O. bartramii and D. gigas fisheries were primarily bounded by 36°– 48°N and 150°–170°E in the Northwest Pacific Ocean and by 8°–20°S and 95°–75°W in the Southeast Pacific Ocean, respectively (Fig. 1).

|

Fig. 1 The geographical distribution of fishing ground (FG) for Ommastrephes bartramii in the high seas of Northwest Pacific Ocean and Dosidicus gigas outside of the exclusive economic zone off Peru in the Southeast Pacific Ocean. The Niño 3.4 and Niño 1+2 regions are also shown on the map. |

In this study, we examined the variability in the abundance and distribution of O. bartramii and D. gigas from September to November during 2006–2015. For shortlived squid species, abundance and distribution can be effectively indicated by CPUE and the latitudinal gravity centers (LATG) of fishing effort (Cao et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2016). The CPUE (catch per unit effort) within a 0.5° × 0.5° fishing grid for the two squid species were calculated by the following equation (Cao et al., 2009):

| ${\rm{CPU}}{{\rm{E}}_{}} = \frac{{\sum {{\rm{Catc}}{{\rm{h}}_{}}} }}{{\sum {{\rm{Fishing effor}}{{\rm{t}}_{}}} }}, $ | (1) |

where ∑Catch is the sum of catch for all the fishing vessels within a fishing grid; and ∑Fishing effort is the sum of fishing days for all the fishing vessels within a fishing unit. For Chinese squid-jigging fishing vessels in the western and southeastern Pacific Ocean, they were equipped with almost same fishing powers with similar engines, lamps. And fishing activities were all performed at night without bycatch (Chen et al., 2008). Thus, CPUE was used as a proxy to indicate squid abundance for the two squids.

The monthly LATG for the two squid fishery was calculated using the following equation (Li et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2016):

| ${\rm{LAT}}{{\rm{G}}_m}{\rm{ = }}\frac{{\sum {{\rm{(Latitud}}{{\rm{e}}_{{\rm{(}}i{\rm{, }}m{\rm{)}}}} \times {\rm{Fishing effor}}{{\rm{t}}_{{\rm{(}}i{\rm{, }}m{\rm{)}}}}{\rm{)}}} }}{{\sum {{\rm{Fishing effor}}{{\rm{t}}_{{\rm{(}}i{\rm{, }}m{\rm{)}}}}} }}, $ | (2) |

where Latitude(i, m) is the latitude within the ith fishing unit in month m; Fishing effort(i, m) is the total fishing efforts within the ith fishing unit in month m. In addition, correlations between annual CPUE and LATG for each squid fishery were examined statistically using Pearson's r correlation analysis.

2.2 Oceanographic Variables and Climatic IndexSea surface temperature (SST) was considered as a critical environmental driver for the distribution and abundance of squid species (Yu et al., 2015). In this study, the monthly SST was from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Optimum Interpolation (OI) SST Version2 with spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. The SST data were grouped on a 0.5°×0.5° latitude/longitude grid to match with the spatial resolution of fishery data.

The monthly SST anomaly (SSTA) in the Niño 3.4 region (between 5°N–5°S and 120°–170°W, close to O. bartramii fishing ground) and Niño 1+2 region (between 0°– 10°S and 90°–80°W, close to D. gigas fishing ground) were used as indicators to represent the climate variability in the Northwest and the Southeast Pacific Ocean, respectively. Many studies have proved that Niño 3.4 and 1+2 SST yielded significant impacts on environmental changes on the fishing ground of O. bartramii and D. gigas, respectively (Chen et al., 2007; Alabia et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016). Therefore, the climate index data from Niño 3.4 and 1+2 regions were selected and obtained from the IRI/ LDEO Climate Data Library during the period from January 2005 to December 2015 (http://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/SOURCES/.Indices/).

2.3 Impacts of Environmental Changes on SquidsTo explore the connection between the climate variability in the Northwest and the Southeast Pacific Ocean, the relationship between the SSTA in the Niño 3.4 and Niño 1+2 regions were initially evaluated by using crosscorrelation functions (CCF). Moreover, in order to understand the impacts of large-scale climate variability on the local water thermal conditions, correlations between monthly Niño 3.4 SSTA/Niño 1+2 SSTA and monthly SST anomaly on each fishing ground were also calculated based on spatial correlation analysis.

Histogram analysis was applied to define the suitable and optimal environmental range for O. bartramii and D. gigas by relating fishing effort to the SST (Zainuddin et al., 2006). Through the analysis above, the proportion of favorable-SST area (PFSST) and the latitudinal location of the optimal SST were further determined and compared between O. bartramii and D. gigas by month. The monthly PFSST from September to November was calculated based on the percentage of suitable SST ranges favorable for the distribution of O. bartramii and D. gigas accounting for the whole fishing ground. Moreover, the relationships between PFSST and the optimal SST latitude and the CPUE and LATG were examined to explore how squid abundance and distribution varied with different environmental conditions. Finally, the years of 2007 (a La Niña year), 2012 (a normal climate year) and 2015 (an El Niño year) were selected to compare the SST change on the fishing ground and its influence on the movement of LATG of O. bartramii and D. gigas under different climate conditions.

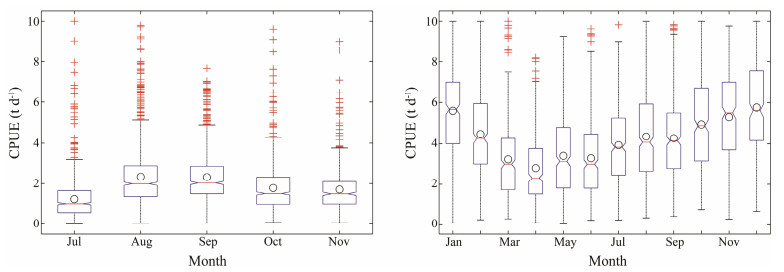

3 Results 3.1 Temporal Variations in CPUE and LATGThe monthly CPUE from July to November for O. bartramii and from January to December for D. gigas were shown in Fig. 2. Both squid fishery displayed a high degree of monthly variability. The O. bartramii CPUE tended to increase from July to August and then decreased in the following months. For the D. gigas CPUE, it decreased from January to April and then increased in the subsequent fishing months. By comparing the two squid fisheries, opposite fluctuation trends in the monthly average CPUE were observed from September to November. Decreased O. bartramii CPUE corresponded to increased D. gigas CPUE in each month.

|

Fig. 2 Monthly catch per unit effort (CPUE) of Ommastrephes bartramii from July to November and Dosidicus gigas from January to December during 2006–2015. The open circles indicate the monthly average CPUE. |

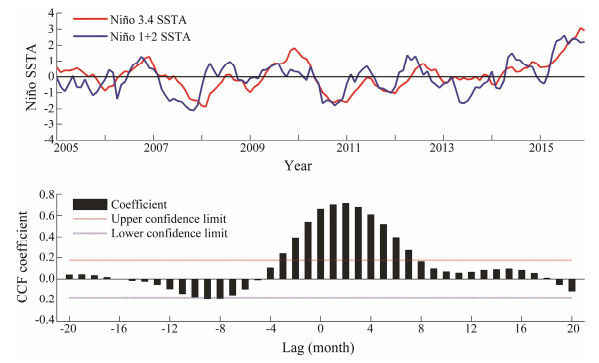

The CPUE and LATG from September to November over 2006–2015 were chosen to compare the two squid fisheries (Fig. 3). Interannual variability and synchronous fluctuation were observed in the O. bartramii and D. gigas CPUEs with significant negative correlations between them (r = −0.889, P < 0.001). With an opposing annually variability trend, statistically significant negative correlations were also found between the LATG of O. bartramii and D. gigas (r = −0.820, P < 0.001), suggesting that the LATG of O. bartramii performed northward movement, while the D. gigas also generally shifted northward.

|

Fig. 3 Squid abundance (catch per unit effort, CPUE) and distribution (latitudinal gravity centers, LATG) of Ommastrephes bartramii and Dosidicus gigas from September to November over 2006–2015. |

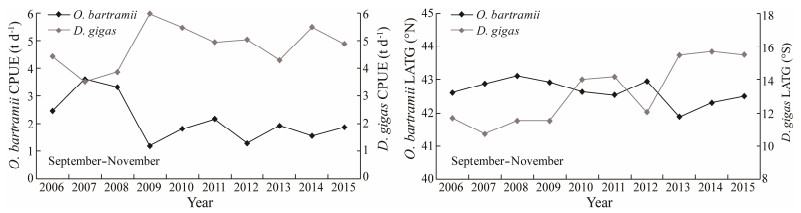

Time series of SSTA in the Niño 3.4 and Niño 1+2 were examined from 2005 to 2015 (Fig. 4). Results suggested that a basically consistent trend was observed between them. Furthermore, a significantly positive cross-correlation was found between the Niño 3.4 SSTA and Niño 1+2 SSTA at time lag of (−3)–7 months. With time-lag of 2 months, the highest correlation coefficient was 0.7135, implying that the variability trends of the SSTA within the two Niño regions were largely similar and synchronously occurred.

|

Fig. 4 The time series of Niño 3.4 index and Niño 1+2 index from 2005 to 2015 (upper panel) and the cross-correlation coefficient between them (lower panel). |

Because the O. bartramii fishing ground and D. gigas fishing ground were close to the Niño 3.4 region and Niño 1+2 region, respectively (Fig. 1), we then examined the influences of Niño 3.4 SSTA/Niño 1+2 SSTA on the SSTA in each adjacent fishing ground. Correlations between the Niño 3.4 SSTA and the SSTA on the O. bartramii fishing ground showed a significant negative relationship (Fig. 5). However, in terms of the SSTA on the D. gigas fishing ground, the Niño 1+2 SSTA was positively correlated with it (Fig. 5).

|

Fig. 5 Spatial distribution of correlation coefficient (A) between the Niño 3.4 index and the sea surface temperature anomaly (SST) anomaly on the fishing ground of Ommastrephes bartramii (upper panel); and (B) between the Niño 1+2 index and the sea surface temperature (SST) anomaly on the fishing ground of Dosidicus gigas (lower panel). |

Using the histogram analysis, the fishing efforts for O. bartramii fishery during September to November occurred in areas where SST ranged from 4℃ to 25℃. However, most high fishing efforts were obtained in the waters where SST varied primarily between 11℃ and 20℃. The highest fishing effort in fishing ground tended to be centered at 15℃ SST (Fig. 6). Distribution of fishing effort of D. gigas fishery in relation to SST indicated that the D. gigas fishing ground occurred between 10℃ and 25℃ SST. The high fishing effort was mainly taken in fishing grounds where the SST ranged from 16℃ to 20℃. The highest fishing efforts most frequently occurred at 18℃ SST (Fig. 6). Based on these results, the suitable SST ranges for O. bartramii and D. gigas during September to November were defined at 11–20℃ and 16–20℃, respectively. The optimal SST for O. bartramii and D. gigas corresponded to 15℃ and 18℃, respectively. The suitable SST ranges for the two squids were then used to determine the PFSST.

|

Fig. 6 Fishing efforts in relation to sea surface temperature (SST) for Ommastrephes bartramii (upper panel) and Dosidicus gigas (lower panel) from September to November over 2006–2015. |

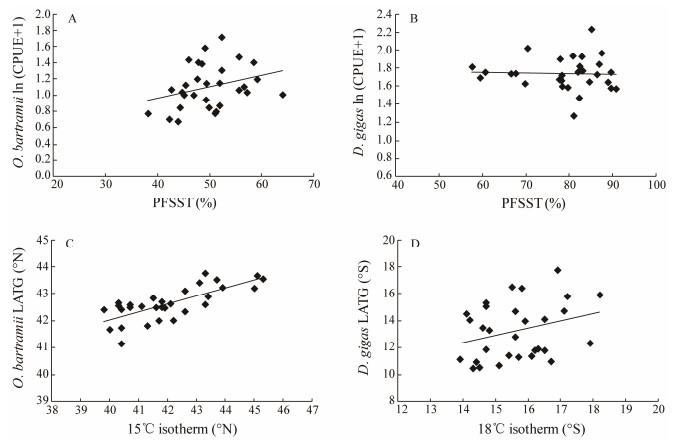

The monthly O. bartramii CPUEs were significantly increased with the PFSST (areas with SST between 11–20℃) on the fishing ground in the Northwest Pacific Ocean (Fig. 7A) (P < 0.05). For the correlation between D. gigas CPUEs and PFSST (areas with SST between 16–20℃) in the Southeast Pacific Ocean, no significant relationship was found; however, most high CPUEs occurred with enlarged PFSST (Fig. 7B). Significant positive relationship were also found between the monthly latitudinal location of 15℃ isotherm and O. bartramii LATG (Fig. 7C) (P < 0.001), as well as between the monthly latitudinal location of 18℃ isotherm and D. gigas LATG (Fig. 7D) (P < 0.05).

|

Fig. 7 The relationship between the natural log-transformed catch per unit effort (CPUE) and proportion of favorable-SST area (PFSST) for (A) Ommastrephes bartramii and (B) Dosidicus gigas, and between the latitudinal gravity centers (LATG) and the average latitude of the optimal SST isotherm for (C) Ommastrephes bartramii and (D) Dosidicus gigas during September–November 2006–2015. |

We compared the interannual variability in PFSST on the O. bartramii fishing ground and D. gigas fishing ground month by month from September to November (Fig. 8). During September, O. bartramii PFSST ranged from 45.1% in 2012 to 64% in 2015. For D. gigas, the PFSST varied between 60.6% and 89.6%. Statistically significant negative correlations (r =−0.714, P < 0.05) were found between O. bartramii PFSST and D. gigas PFSST in September. In October, the range of O. bartramii PFSST was from 42.2% in 2009 to 59.1% in 2006. The highest D. gigas PFSST reached up to 89.6% in 2013, while the lowest value was observed in 2015. A significantly negative relationship (r = −0.787, P < 0.01) was also found between them in October. However, for the PFSST in November, the relationship between the squid stocks was not significant (r = −0.326, P = 0.179). It was observed that opposite fluctuation in the PFSST was found from 2006 to 2008 and from 2010 to 2014, while the variability trend was similar with other years.

|

Fig. 8 Monthly proportion of favorable-SST area (PFSST) for Ommastrephes bartramii and Dosidicus gigas from September to November, respectively. |

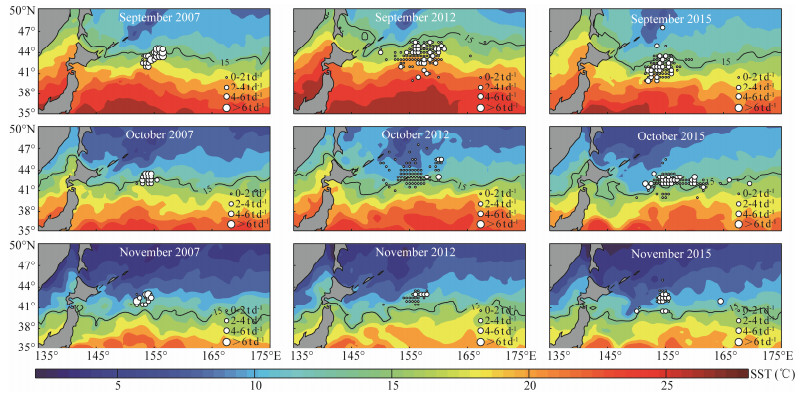

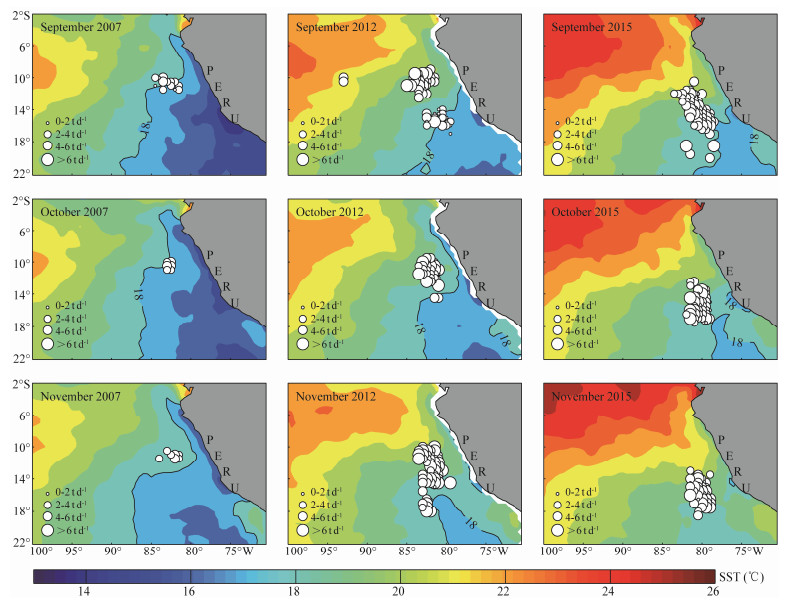

The location of the most preferred SST isotherms for O. bartramii and D. gigas were drawn in Figs. 9 and 10. It was found that the 15℃ isoline from September to November in 2007 and 2012 was distributed in the northern regions on the fishing ground of O. bartramii relative to the year in 2015. For D. gigas, it was clear that the 18℃ isoline for each month was distributed in the northern, middle and southern regions on the fishing ground. Specifically, the 18℃ isoline moved out of the fishing ground in November 2015, as the SST on the fishing ground was higher than 18℃.

|

Fig. 9 Contour maps of sea surface temperature (SST) with optimal SST isotherm (15℃) for Ommastrephes bartramii from September to November over 2007, 2012 and 2015. |

|

Fig. 10 Contour maps of sea surface temperature (SST) with the optimal SST isotherm (18℃) for Dosidicus gigas from September to November over 2007, 2012 and 2015. |

Due to only 1-year life cycle, both O. bartramii and D. gigas are very sensitive to the climatic and environmental conditions on the spawning and fishing grounds at various spatio-temporal scales (Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, the catch, CPUE and LATG of the two squid species showed significant monthly and yearly variations (Ibánez et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2019). For O. bartramii, its abundance was low in July and relatively high from August to November. Such variability trends in CPUE of O. bartramii were consistent with its migration behavior (Yu et al., 2016). The western winter-spring O. bartramii stock mostly migrated into the fishing ground in August and back into the spawning ground in November (Bower and Ichii, 2005). Based on the characteristics of the life history, Chinese fishermen started to fish O. bartramii in July every year (Yu et al., 2015). For D. gigas fishery off Peru, the high CPUE occurred From July to December, it also corresponded to the migration route of D. gigas from the nearshore waters off Peru to the open sea outside the EEZ waters off Peru (Xu et al., 2018). Our results were consistent with previous conclusions on seasonal changes of abundance of O. bartramii and D. gigas.

Regarding the annual CPUE and LATG between O. bartramii and D. gigas, our results showed the significantly negative relationship between them, while both CPUE and LATG changed synchronously for the two squids. To our knowledge, this is the first study to find such results. Interestingly, it was found that high CPUE of O. bartramii generally corresponded to low CPUE of D. gigas, and the movements of LATG of these two squid species were basically similar from September to November during 2006–2015. For O. bartramii stock, the CPUE was low in 2009 and 2015 and high in 2007 and 2008. Based on previous findings, O. bartramii was strongly affected by the El Niño and La Niña events (Chen et al., 2007). Generally, the El Niño events are not favorable for the formation of fishing ground with productive squid abundance (Yu et al., 2019). Therefore, the occurrence of the El Niño events in 2009 and 2015 led to the low CPUE of O. bartramii. On the contrary, in 2007 and 2008, the La Niña event and the normal climate condition resulted in high abundance of O. bartramii. However, it was found that the CPUEs of D. gigas in 2009 and 2015 were high in this study. According to the findings from the previous studies, the El Niño events commonly yielded enlarged poor habitats for D. gigas and consequently led to relatively low abundance of it (Ichii et al., 2002; Waluda et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2012). The opposite results were likely due to the different data used in the analysis. This analysis only included the months with high CPUEs of D. gigas from September to November. The influences of the El Niño and La Niña events on O. bartramii and D. gigas are quite complicated, depending on the intensity and type of the anomalous climate conditions.

4.2 The Effect of SST on O. bartramii and D. gigas Abundance and DistributionIt was well known that various environmental factors such as SST, sea surface height (SSH), chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) concentration played crucial roles in regulating the abundance and distribution of squid species (Waluda and Rodhouse, 2006; Robinson et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2015). However, among these factors, SST was considered as the most important one during the whole life of ommastrephid squids (Yatsu et al., 2000; Ichii et al., 2009). SST directly affects squid spawning location, breeding time and behavior, migration, feeding, growth, survival and physiological metabolism, etc (Pecl and Jackson, 2008; Rosa et al., 2011; Frawley et al., 2019). Squid species can quickly respond to SST changes. They will move to suitable habitat if the SST in the original region is not favorable for inhabiting (Xu et al., 2016; Yu and Chen, 2018). SST is frequently used in many studies to model the habitat formation and identify spatio-temporal changes of fishing ground for squid species (Chen et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2019).

In the Northwest Pacific Ocean, the SST is the most suitable index to explore fishing grounds of O. bartramii. For example, the fishing ground of O. bartramii can be identified by dense distribution of isotherm surface water layer, convergence of warm and cold waters and thermal layer based on the SST (Shen et al., 2004). The suitable SST range for O. bartramii varied with seasons and fishing locations. The seasonal and spatial distributions of O. bartramii were largely explained by 7–17℃ SST in winter and 11–18℃ in summer (Alabia et al., 2015). The 17℃ and 20℃ SST isotherms are regarded as the fishing ground index with high O. bartramii abundance in the west of 155°E, and between 155° and 160°E (Chen, 1997). These results are consistent with our findings. Moreover, the SST contributes the highest to the habitat model gain comparing to other factors, indicating that the habitat formation of O. bartramii is highly vulnerable to drastic changes in SST (Alabia et al., 2015).

With regard to D. gigas, there are four major fishing grounds in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, the suitable ranges of SST for D. gigas vary with seasons and different geographical distributions (Medellín-Ortiz et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2018). Previous studies showed that jumbo squids off Peru usually live in waters with SST ranging from 17 to 22℃ (Waluda et al., 2006), which is in accordance with the results in this study. Habitat modeling method revealed that the weighing of SST relative to SSH and Chl-a also contributed the highest to the suitable habitat model (Hu et al., 2010). Furthermore, strong relationship was found between SST and CPUE for the two squids. Interannual variability in squid abundance and distribution are closely linked to variations in SST on the spawning and fishing ground (Cao et al., 2009; Ichii et al., 2011). Given that SST can define the limits of the habitat of squids, this study employed SST as the only environmental variable to analyze the SST-related synchronous fluctuations in abundance and distribution of O. bartramii and D. gigas.

4.3 Possible Causes of Synchronous Fluctuations of O. bartramii and D. gigas and Its ImplicationsA growing number of studies proved that large-scale climate changes have yielded strong impacts on local environmental conditions on the fishing ground of pelagic fish (Tian et al., 2003; Zainuddin et al., 2006). In this study, it was found that the change trends of SSTA in the Niño 3.4 and Niño 1+2 regions showed the similar variability pattern during 2006–2015. The negative relationship was found between Niño 3.4 SSTA and the SSTA on the fishing ground of O. bartramii, while the positive one was found between the Niño 1+2 SSTA and the SSTA on the fishing ground of D. gigas, suggesting that the SST on the fishing ground of these two squids was dramatically influenced by the large-scale synchronous SSTA variability in the Niño 3.4 and 1+2 regions. Considering all the information, the possible causes of synchronous fluctuations in abundance and distribution of O. bartramii and D. gigas can be indicated. The fishing ground of the two squids O. bartramii and D. gigas are in the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere respectively. Synchrony in SST changes occurred in the Niño 3.4 and Niño 1+2 regions, leading to the synchronous opposite fluctuations in the SST on the fishing ground of O. bartramii in the Northwest Pacific Ocean and on the fishing ground of D. gigas in the Southeast Pacific Ocean off Peru. Opposite changes in SST led to increased O. bartramii PFSST corresponding to decreased D. gigas PFSST from September to November over 2006–2015, resulting in synchronous opposing changes in CPUE. At the same time, the movement of the latitudinal location of the optimal SST for O. bartramii was in phase with the shift of optimal SST for D. gigas, yielding similar movement pattern of the LATG. Our findings suggest that the potential mechanism behind synchronous opposing changes in abundance and similar movement in the latitudinal distribution of the two squid species was due to simultaneous variations in the PFSST and the latitudinal location of the optimal SST front, which were strongly influenced by the large-scale variability of the SSTA in the Niño 3.4 and Niño 1+2 regions. Understanding synchronous fluctuations in CPUE and LATG of O. bartramii and D. gigas has important implications for Chinese squid fisheries management. Based on the present study, how the CPUE and LATG of the two squids synchronously fluctuated with the environmental conditions can be deduced. The fishermen then can make correct fishing decisions. For example, with the decreasing trends in CPUE of O. bartramii and the concurrent increasing trends for D. gigas CPUE, the fishermen can decrease the number of fishing vessels in the western Pacific and increase the number of fishing vessels in the southeastern Pacific off Peru.

AcknowledgementsThis study was financially supported by the National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2019YFD0901405), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 4190 6073), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (No. 19ZR1423000), the Open Fund for Key Laboratory of Sustainable Exploitation of Oceanic Fisheries Resources in Marine Fisheries Research Institute of Zhejiang (No. 2020 KF002), and the Shanghai Universities First-Class Disciplines Project (Fisheries A).

Alabia, I. D., Saitoh, S. I., Hirawake, T., Igarashi, H., Ishikawa, Y., Usui, N., Kamachi, M., Awaji, T. and Seito, M., 2016. Elucidating the potential squid habitat responses in the central North Pacific to the recent ENSO flavors. Hydrobiologia, 772(1): 215-227. DOI:10.1007/s10750-016-2662-5 (  0) 0) |

Alabia, I. D., Saitoh, S. I., Mugo, R., Igarashi, H., Ishikawa, Y., Usui, N. and Seito, M., 2015. Seasonal potential fishing ground prediction of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the western and central North Pacific. Fisheries Oceanography, 24(2): 190-203. DOI:10.1111/fog.12102 (  0) 0) |

Anderson, C. I. and Rodhouse, P. G., 2001. Life cycles, oceanography and variability: Ommastrephid squid in variable oceanographic environments. Fisheries Research, 54(1): 133-143. DOI:10.1016/S0165-7836(01)00378-2 (  0) 0) |

Argüelles,, J, ., Rodhouse, P. G., Villegas, P. and Castillo, G., 2001. Age, growth and population structure of the jumbo flying squid Dosidicus gigas in Peruvian waters. Fisheries Research, 54(1): 51-61. DOI:10.1016/S0165-7836(01)00380-0 (  0) 0) |

Arkhipkin, A. I., Rodhouse, P. G., Pierce, G. J., Sauer, W., Sakai, M., Allcock, L., Arguelles, J., Bower, J. R., Castillo, G., Ceriola, L., Chen, C. S., Chen, X. J., Diaz-Santana, M., Downey, N., Gonzalez, A. F., Granados, A. J., Green, C. P., Guerra, A., Hendrickson, L. C., Ibanez, C., Ito, K., Jereb, P., Kato, Y., Katugin, O. N., Kawano, M., Kidokoro, H. and Kulik, V. V., 2015. World squid fisheries. Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture, 23(2): 92-252. (  0) 0) |

Bower, J. R. and Ichii, T., 2005. The red flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii): A review of recent research and the fishery in Japan. Fisheries Research, 76(1): 39-55. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2005.05.009 (  0) 0) |

Boyle, P. R., 1990. Cephalopod biology in the fisheries context. Fisheries Research, 8(4): 303-321. DOI:10.1016/0165-7836(90)90001-C (  0) 0) |

Cao, J., Chen, X. and Chen, Y., 2009. Influence of surface oceanographic variability on abundance of the western winter–spring cohort of neon flying squid Ommastrephes bartramii in the NW Pacific Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 381: 119-127. DOI:10.3354/meps07969 (  0) 0) |

Chen, C. S. and Chiu, T. S., 2003. Variations of life history parameters in two geographical groups of the neon flying squid, Ommastrephes bartramii, from the North Pacific. Fisheries Research, 63(3): 349-366. DOI:10.1016/S0165-7836(03)00101-2 (  0) 0) |

Chen, X. J., 1997. An analysis on marine environment factors of fishing ground of Ommastrephes bartramii in Northwestern Pacific. Journal of Shanghai Fishery University, 6(4): 263-267 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Chen, X. J., Liu, B. L., Tian, S. Q., Qian, W. G. and Li, G., 2009. Forecasting the fishing ground of Ommastrephes bartramii with SST-based habitat suitability modeling in northwestern pacific. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 40(6): 707-713 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Chen, X. J., Zhao, X. H. and Chen, Y., 2007. Influence of El Niño/La Niña on the western winter–spring cohort of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 64(6): 1152-1160. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsm103 (  0) 0) |

Chen, X., Liu, B. and Chen, Y., 2008. A review of the development of Chinese distant-water squid jigging fisheries. Fisheries Research, 89(3): 211-221. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2007.10.012 (  0) 0) |

Chen, X., Tian, S., Chen, Y. and Liu, B., 2010. A modeling approach to identify optimal habitat and suitable fishing grounds for neon flying squid (Ommostrephes bartramii) in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Fishery Bulletin, 108(1): 1-14. (  0) 0) |

Cherel, Y. and Weimerskirch, H., 1995. Seabirds as indicators of marine resources: Black-browed albatrosses feeding on ommastrephid squids in Kerguelen waters. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 129(1-3): 295-300. (  0) 0) |

Dunning, M. C. and Wormuth, J. H., 1998. The ommastrephid squid genus Todarodes: A review of systematics, distribution, and biology (Cephalopoda: Teuthoidea). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology, 586(2): 385-392. (  0) 0) |

Frawley, T. H., Briscoe, D. K., Daniel, P. C., Britten, G. L., Crowder, L. B., Robinson, C. J. and Gilly, W. F., 2019. Impacts of a shift to a warm-water regime in the Gulf of California on jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas). ICES Journal of Marine Science, 76(7): 2413-2426. (  0) 0) |

Hernández-Herrera, A., Morales-Bojórquez,, E, ., Cisneros-Mata, M. A., Nevárez-Martínez,, M., O. and Rivera, -Parra G. I., 1998. Management strategy for the giant squid (Dosidicus gigas) fishery in the Gulf of California, Mexico. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Reports, 39: 212-218. (  0) 0) |

Hu, G., Boenish, R., Gao, C., Li, B., Chen, X., Chen, Y. and Punt, A. E., 2019. Spatio-temporal variability in trophic ecology of jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas) in the southeastern Pacific: Insights from isotopic signatures in beaks. Fisheries Research, 212: 56-62. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2018.12.009 (  0) 0) |

Hu, Z. M., Chen, X. J., Zhou, Y. Q., Qian, W. G. and Liu, B. L., 2010. Forecasting fishing ground of Dosidicus gigas based on habitat suitability index off Peru. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 32(5): 67-75 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Ibánez,, C., M., Argüelles,, J, ., Yamashiro, C., Sepúlveda,, R., D., Pardo-Gandarillas, M. C. and Keyl, F., 2016. Population dynamics of the squids Dosidicus gigas (Oegopsida: Ommastrephidae) and Doryteuthis gahi (Myopsida: Loliginidae) in northern Peru. Fisheries Research, 173: 151-158. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2015.06.014 (  0) 0) |

Ichii, T., Mahapatra, K., Okamura, H. and Okada, Y., 2006. Stock assessment of the autumn cohort of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the North Pacific based on past largescale high seas driftnet fishery data. Fisheries Research, 78(2-3): 286-297. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2006.01.003 (  0) 0) |

Ichii, T., Mahapatra, K., Sakai, M. and Okada, Y., 2009. Life history of the neon flying squid: Effect of the oceanographic regime in the North Pacific Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 378: 1-11. DOI:10.3354/meps07873 (  0) 0) |

Ichii, T., Mahapatra, K., Sakai, M., Wakabayashi, T., Okamura, H., Igarashi, H. and Okada, Y., 2011. Changes in abundance of the neon flying squid Ommastrephes bartramii in relation to climate change in the central North Pacific Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 441: 151-164. DOI:10.3354/meps09365 (  0) 0) |

Ichii, T., Mahapatra, K., Watanabe, T., Yatsu, A., Inagake, D. and Okada, Y., 2002. Occurrence of jumbo flying squid Dosidicus gigas aggregations associated with the countercurrent ridge off the Costa Rica Dome during 1997 El Niño and 1999 La Niña. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 231: 151-166. DOI:10.3354/meps231151 (  0) 0) |

Igarashi, H., Ichii, T., Sakai, M., Ishikawa, Y., Toyoda, T., Masuda, S. and Awaji, T., 2017. Possible link between interannual variation of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) abundance in the North Pacific and the climate phase shift in 1998/ 1999. Progress in Oceanography, 150: 20-34. DOI:10.1016/j.pocean.2015.03.008 (  0) 0) |

Igarashi, H., Saitoh, S. I., Ishikawa, Y., Kamachi, M., Usui, N., Sakai, M. and Imamura, Y., 2018. Identifying potential habitat distribution of the neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) off the eastern coast of Japan in winter. Fisheries Oceanography, 27(1): 16-27. DOI:10.1111/fog.12230 (  0) 0) |

Jackson, G. D., Shaw, A. G. P. and Lalas, C., 2000. Distribution and biomass of two squid species off southern New Zealand: Nototodarus sloanii and Moroteuthis ingens. Polar Biology, 23(10): 699-705. DOI:10.1007/s003000000141 (  0) 0) |

Kang, Y. S., Kim, J. Y., Kim, H. G. and Park, J. H., 2002. Longterm changes in zooplankton and its relationship with squid, Todarodes pacificus, catch in Japan/East Sea. Fisheries Oceanography, 11(6): 337-346. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2419.2002.00211.x (  0) 0) |

Lee, D., Son, S. H., Lee, C. I., Kang, C. K. and Lee, S. H., 2019. Spatio-temporal variability of the habitat suitability index for the Todarodes pacificus (Japanese common squid) around South Korea. Remote Sensing, 11(23): 2720. DOI:10.3390/rs11232720 (  0) 0) |

Li, G., Chen, X. J., Lei, L. and Guan, W. J., 2014. Distribution of hotspots of chub mackerel based on remote-sensing data in coastal waters of China. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 35(11-12): 4399-4421. DOI:10.1080/01431161.2014.916057 (  0) 0) |

Ma, J., Chen, X. J., Liu, B. L., Tian, S. Q., Li, S. L. and Cao, J., 2011. Review of fisheries biology of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the North Pacific Ocean. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University, 20(4): 563-570 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Medellín-Ortiz, A., Cadena-Cárdenas,, L, . and Santana, -Morales O., 2016. Environmental effects on the jumbo squid fishery along Baja California's west coast. Fisheries Science, 82(6): 851-861. DOI:10.1007/s12562-016-1026-4 (  0) 0) |

Morales-Bojórquez,, E, . and Pacheco, -Bedoya J. L., 2016. Jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas: A new fishery in Ecuador. Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture, 24(1): 98-110. (  0) 0) |

Nigmatullin, C. M., Nesis, K. N. and Arkhipkin, A. I., 2001. A review of the biology of the jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae). Fisheries Research, 54(1): 9-19. DOI:10.1016/S0165-7836(01)00371-X (  0) 0) |

Parry, M., 2006. Feeding behavior of two ommastrephid squids Ommastrephes bartramii and Sthenoteuthis oualaniensis off Hawaii. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 318: 229-235. DOI:10.3354/meps318229 (  0) 0) |

Paulino, C., Segura, M., Chac, ón and G, ., 2016. Spatial variability of jumbo flying squid (Dosidicus gigas) fishery related to remotely sensed SST and chlorophyll-a concentration (2004– 2012). Fisheries Research, 173(2): 122-127. (  0) 0) |

Pecl, G. T. and Jackson, G. D., 2008. The potential impacts of climate change on inshore squid: Biology, ecology and fisheries. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 18(4): 373-385. DOI:10.1007/s11160-007-9077-3 (  0) 0) |

Robinson, C. J., Gómez-Gutiérrez,, J, ., and, de León and D., A. S., 2013. Jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas) landings in the Gulf of Cali fornia related to remotely sensed SST and concentrations of chlorophyll a (1998 – 2012). Fisheries Research, 137: 97-103. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2012.09.006 (  0) 0) |

Rodhouse, P. G., 2008. Large-scale range expansion and variability in ommastrephid squid populations: A review of environmental links. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Report, 49: 83-89. (  0) 0) |

Rosa, A. L., Yamamoto, J. and Sakurai, Y., 2011. Effects of environmental variability on the spawning areas, catch, and recruitment of the Japanese common squid, Todarodes pacificus (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae), from the 1970s to the 2000s. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(6): 1114-1121. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsr037 (  0) 0) |

Shen, X., Fan, W. and Cui, X., 2004. Study on the relationship of fishing ground distribution of Ommastrephes bartrami and water temperature in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Marine Fisheries Research, 25(3): 10-14 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Taipe, A., Yamashiro, C., Mariategui, L., Rojas, P. and Roque, C., 2001. Distribution and concentrations of jumbo flying squid (Dosidicus gigas) off the Peruvian coast between 1991 and 1999. Fisheries Research, 54(1): 21-32. DOI:10.1016/S0165-7836(01)00377-0 (  0) 0) |

Tian, Y., Akamine, T. and Suda, M., 2003. Variations in the abundance of Pacific saury (Cololabis saira) from the northwestern Pacific in relation to oceanic-climate changes. Fisheries research, 60(2-3): 439-454. DOI:10.1016/S0165-7836(02)00143-1 (  0) 0) |

Waluda, C. M. and Rodhouse, P. G., 2006. Remotely sensed mesoscale oceanography of the Central Eastern Pacific and recruitment variability in Dosidicus gigas. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 310: 25-32. DOI:10.3354/meps310025 (  0) 0) |

Waluda, C. M., Yamashiro, C. and Rodhouse, P. G., 2006. Influence of the ENSO cycle on the light-fishery for Dosidicus gigas in the Peru Current: An analysis of remotely sensed data. Fisheries Research, 79(1-2): 56-63. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2006.02.017 (  0) 0) |

Waluda, C. M., Yamashiro, C., Elvidge, C. D., Hobson, V. R. and Rodhouse, P. G., 2004. Quantifying light-fishing for Dosidicus gigas in the eastern Pacific using satellite remote sensing. Remote Sensing of Environment, 91(2): 129-133. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2004.02.006 (  0) 0) |

Wang, J., Chen, X., Tanaka, K., Cao, J. and Chen, Y., 2017. Environmental influences on commercial oceanic ommastrephid squids: A stock assessment perspective. Scientia Marina, 81(1): 37-47. DOI:10.3989/scimar.04497.25B (  0) 0) |

Xu, B., Chen, X., Tian, S., Qian, W. and Liu, B., 2012. Effects of El Niño/La Niña on distribution of fishing ground of Dosidicus gigas off Peru waters. Journal of Fisheries of China, 36(5): 696-707 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1231.2012.27419 (  0) 0) |

Xu, J., Chen, X. J., Chen, Y., Ding, Q. and Tian, S. Q., 2016. The effect of sea surface temperature increase on the potential habitat of Ommastrephes bartramii in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 35(2): 109-116. DOI:10.1007/s13131-015-0782-9 (  0) 0) |

Xu, L., Chen, X., Guan, W., Tian, S. and Chen, Y., 2018. The impact of spatial autocorrelation on CPUE standardization between two different fisheries. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 36(3): 973-980. DOI:10.1007/s00343-018-6294-7 (  0) 0) |

Yatsu, A., Watanabe, T., Mori, J., Nagasawa, K., Ishida, Y., Meguro, T. and Sakurai, Y., 2000. Interannual variability in stock abundance of the neon flying squid, Ommastrephes bartramii, in the North Pacific Ocean during 1979 – 1998: Impact of driftnet fishing and oceanographic conditions. Fisheries Oceanography, 9(2): 163-170. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2419.2000.00130.x (  0) 0) |

Yu, W. and Chen, X., 2018. Ocean warming-induced rangeshifting of potential habitat for jumbo flying squid Dosidicus gigas in the Southeast Pacific Ocean off Peru. Fisheries Research, 204: 137-146. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2018.02.016 (  0) 0) |

Yu, W., Chen, X., Yi, Q. and Chen, Y., 2016. Spatio-temporal distributions and habitat hotspots of the winter – spring cohort of neon flying squid Ommastrephes bartramii in relation to oceanographic conditions in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Fisheries Research, 175: 103-115. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2015.11.026 (  0) 0) |

Yu, W., Chen, X., Yi, Q. and Tian, S., 2015. A review of interaction between neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) and oceanographic variability in the North Pacific Ocean. Journal of Ocean University of China, 14(4): 739-748. DOI:10.1007/s11802-015-2562-8 (  0) 0) |

Yu, W., Chen, X., Zhang, Y. and Yi, Q., 2019. Habitat suitability modelling revealing environmental-driven abundance variability and geographical distribution shift of winter-spring cohort of neon flying squid Ommastrephes bartramii in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 76(6): 1722-1735. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsz051 (  0) 0) |

Yu, W., Yi, Q., Chen, X. and Chen, Y., 2016. Modelling the effects of climate variability on habitat suitability of jumbo flying squid, Dosidicus gigas, in the Southeast Pacific Ocean off Peru. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 73(2): 239-249. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsv223 (  0) 0) |

Zainuddin, M., Kiyofuji, H., Saitoh, K. and Saitoh, S. I., 2006. Using multi-sensor satellite remote sensing and catch data to detect ocean hot spots for albacore (Thunnus alalunga) in the northwestern North Pacific. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 53(3-4): 419-431. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2006.01.007 (  0) 0) |

Zeidberg, L. D. and Robison, B. H., 2007. Invasive range expansion by the Humboldt squid, Dosidicus gigas, in the eastern North Pacific. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(31): 12948-12950. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0702043104 (  0) 0) |

2021, Vol. 20

2021, Vol. 20