2) Field Observation and Research Station of Haizhou Bay Fishery Ecosystem, Ministry of Education, Qingdao 266003, China;

3) Function Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Laoshan Laboratory, Qingdao 266237, China

Species distribution patterns is one of the most popular concerns in ecology (Thorson et al., 2015). A lot of researches have been conducted to improve understanding of species distribution and habitat suitability of spatially aggregated species (Defeo et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). In the context of spatial management policies, proper projections of future species distributions are particularly needed to establish species management and conservation measures (Zhang et al., 2022), as well as to inform fisheries management (Bond et al., 2011; Marzloff et al., 2016; González-Andrés et al., 2021), in conjunction with future environmental conditions. In this regard, Species Distribution Models (SDMs) provide an effective tool to quantify the relationship between species and the environment and are often used for predicting species distribution (Pollock et al., 2014). In recent years, there has been a rapid development in this field and a large number of statistical analysis techniques have been used in the construction of the SDMs.

Meanwhile, it is important to note that the performance of SDMs could be impaired by a wide range of factors, which have not been fully understood. Particularly, typical SDMs tend to focus only on the effects of environmental factors, whereas species distributions are influenced not only by environmental factors but also by inter-relationships among species (Warton et al., 2015; Ovaskainen et al., 2017a; Zeng and Wiens, 2021). Additionally, spatial autocorrelation effects are rarely taken into account in the modeling process. To address these general concerns, Joint Species Distribution Models (JSDMs) have been proposed to handle environmental factors and interspecific relationships simultaneously, which provide a feasible approach for analyzing the structure of biomes and clustering process (Pollock et al., 2014; Ovaskainen et al., 2016b). With the applications of JSDMs, relevant studies have evaluated the response of species to environmental factors, the co-occurrence of species, and the impact of climate change (Clark et al., 2014; Ovaskainen et al., 2016a, 2016b). Currently, JSDMs have become an indispensable tool for predicting the distribution of species.

As a relative novel method, JSDMs have not been fully examined in terms of performance evaluation and influencing factors (Wilkinson et al., 2019; Poggiato et al., 2021; Wilkinson et al., 2021). In this study, we focus on the role of spatial autocorrelation, an issue that should be concerned for both single-species and multi-species models. Spatial autocorrelation is a phenomenon in modelling species distributions in which samples are not independent of each other in nearby locations (Legendre, 1993). Spatial autocorrelation typically emerges when species distributions are determined by unknown or unmeasured environmental variables or biological interactions (Legendre and Fortin, 1989; Legendre, 1993; Ovaskainen et al., 2016b). Meanwhile many other processes could also be involved, such as the dispersal of organisms, interactions between species related to distance, inappropriate specifications of the species-environment relationships, and the neglect of environmental variables with spatial structure (Legendre and Legendre, 2012). The latter issues are sometimes termed as spatial dependency rather than spatial autocorrelation (Legendre et al., 2002).

The effects of spatial autocorrelation on species distri-bution models are multi-faceted. On the one hand, the presence of spatial autocorrelation in the data inflates the significance test with Type Ⅰ error (Kühn, 2007), i.e., it may lead to falsely believe that a phenomenon or effect exists when in fact it does not. Thus, predictions that do not take into account spatial autocorrelation (i.e., assuming independence between data points) lead to biased estimates of fixed effects (known environmental variables) and overestimates of their statistical significance (Legendre et al., 2002; Ovaskainen et al., 2016b). In the spatially structured environment, spatial autocorrelation may also impact the assessment of model prediction performance (Ovaskainen et al., 2010; Kissling et al., 2012). Many studies with traditional species distribution models often ignore the effect of spatial autocorrelation when predicting species distributions, which may result in inaccurate results (Zhang et al., 2022). On the other hand, if the spatial autocorrelation can be appropriately incorporated into the modelling processes, it may help to capture more accurately the heterogeneity of geospatial variation, and improve our understanding of community composition, geographic distribution, and competitive dynamics (Griffith and Peres-Neto, 2006). For example, Thorson et al. (2015) used spatial factor analysis (SFA) to study the distributions of 10 bird species, and the results showed that considering spatial structure can improve the fitting and prediction of models by sharing information among species compared to single-species distribution models. Thus, spatially-structured models are recommended to reveal the geographic distribution patterns as well as the effects of environmental factors on community growth and competitive outcomes.

Methods for dealing with spatial autocorrelation have been greatly developed in ecological research, based on the need for spatial processes and non-independent points (Dormann et al., 2007; Zimmermann et al., 2010). For example, Simultaneous Autoregressive Model (SAR) and Conditional Autoregressive Model (CAR) contain spatial weight matrices, in which the neighborhoods of each sampling location and the weights of each neighborhood are included in the standard linear model. Another approach is the Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) where linear predictors include random effects and within-subject errors can be spatially autocorrelated (Pinheiro and Bates, 2006). Generalized Least Square (GLS) includes the process of adding a weight matrix calculated from the correlation function to both sides of the regression equation to obtain the least squares estimator (Cliff and Ord, 1981), and to model the spatial correlation between position and neighboring positions in the variance-covariance matrix (Anselin, 2013; Cressie, 2015). Nevertheless, most of the relevant methods with single species have considered spatial autocorrelation in their treatment of model errors, and the information have been rarely used for improving prediction directly. On the other hand, the joint species distribution model can explicitly delineate the effects of spatial random processes by sharing information among species, and ultimately improve the predictive power of the model (Wisz et al., 2013). For example, Ovaskainen et al. (2016a) used the spatially structured latent factor model to statistically calculate the missing environmental factors and interspecific relationships, and the results showed that the predictive performance was greatly improved when the model included spatial latent factors. However, there is a lack of research on the role of spatial autocorrelation in emerging joint species distribution models (Clark et al., 2014; Ovaskainen et al., 2016a), and many studies use independent effects to reflect random spatial process (Hernandez et al., 2006).

In order to elucidate the effect of spatial autocorrelation on the joint species distribution model, this study adopted the Hierarchical Modelling of Species Communities (HMSC) framework to predict species distribution at the community level (Ovaskainen and Abrego, 2020). The model has been developed to reflect similarities and correlations between spatially adjacent units by including a hierarchy of areas representing different spatial units (Ovaskainen and Abrego, 2020). We explicitly considered the spatial autocorrelation and developed three HMSC models according to the model specification of random effects. The performances of the three models were compared in terms of explanatory performance, species responses to the environment, and model predictability. In addition, model's predictive power was evaluated through cross-validation, in which we also considered different levels of sample size by random resampling with respect to the potentials of data-dependent performances of SDMs (Hernandez et al., 2006). The objectives of this study are to clarify the influence of spatial autocorrelation on the predictive ability of HMSC models, and the effects of sample size on the performances of JSDMs. The study may provide guidance on the structural specification for joint species distribution modelling, which can support biodiversity conservation and marine spatial planning.

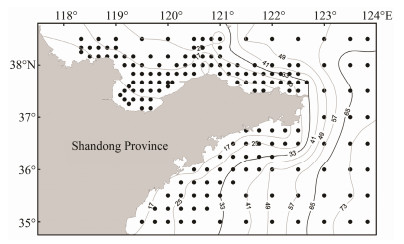

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Data CollectionSpecies distribution data were obtained from a bottom trawl survey of fishery resources conducted in the coastal waters of Shandong Province, China in August, 2017, within the range of 35˚ – 38.5˚N, 118˚ – 124˚E. The fishery resources survey included a total of 155 sampling stations in this area (Fig.1). The survey vessel was an otter trawler of 220 kW with a net gap height of approximately 7.53 m, a width of approximately 15 m, and a cod-end mesh size of 17 mm. The net was towed with the speed of 2 – 3 kn for about 1 h per sampling station, and the trawl surveys were all scheduled during the day. The catch at each station was standardized by trawl time (1 h) and trawl speed (3 kn) to obtain catch per net haul (i.e., relative catch Y, kg h−1).

|

Fig. 1 Bottom trawl survey stations of fishery resources in the coastal waters of Shandong. The gray curves represent bathymetric contours. |

In order to meet the data requirements in model fitting, the top ten dominant species in terms of frequency of occurrence were selected for modeling in JSDMs, mainly including fishes and shrimps (Table 1). The selected species accounted for more than sixty percent of the total biomass of the community, among which the yellow goosefish (Lophius litulon) and the Tanaka's snailfish (Liparis tanakae) are predatory species and goby and shrimp are prey species, which shape strong trophic relationships among the species.

|

|

Table 1 Major species included in the species distribution modeling in the coastal waters of Shandong |

Environmental data considered in this study included water depth (Depth), sea bottom temperature (SBT), sea bottom salinity (SBS), and chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) concentration. The first three data were derived from the ocean circulation model FVCOM (Finite-volume Coastal Ocean Model) (Chen et al., 2016), which simulated the sea area in the range of 118˚ – 124˚E and 35˚ – 39˚N with a resolution of 0.5΄ × 0.5΄ and a total of 16617 grid points. Chl-a data were obtained from the satellite data website (https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/). To accommodate to the species distribution data, the Kriging interpolation was used to estimate the environmental data of corresponding stations of the biological data (Hartman and Hössjer, 2008).

2.2 HMSC ModellingHMSC is a type of JSDM proposed by Ovaskainen et al. (2017b). It is a flexible tool for the hierarchical modeling of species communities using a Bayesian hierarchical approach. The model uses linear regression to integrate the effects of environmental variables and latent variables (LV), which can represent unconsidered environmental factors or interspecific relationships (Zhang et al., 2018). Thus the effects of species on each other can be accounted at the same time in addition to the effects of environmental variables (Ovaskainen et al., 2017b). The HMSC model has a hierarchical structure which enables to synthesize the information on spatio-temporal structure, species characteristics, and phylogeny between species (Ovaskainen et al., 2016b, 2017a). The current development of HMSC plays an increasingly important role in ecological research and contributes largely to understand species distribution dynamics and ecosystem function (Ovaskainen et al., 2017a, 2017b). The general format of HMSC can be written as:

| $ {y_{ij}} \sim D({L_{ij}}, \sigma _j^2), {L_{ij}} = L_{ij}^F + L_{ij}^R, $ |

where yij denotes the abundance of species j at sampling site i, D is the statistical distribution according to the type of data used. Lij denotes the linear prediction, modeled with both fixed effects

| $ L_{ij}^F = \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{{n_c}} {{x_{ik}}{\beta _{kj}}}, L_{ij}^R = \sum\limits_{h = 1}^{{n_f}} {{\eta _{ih}}{\lambda _{jh}}}, $ |

where xik is the measured covariate k = 1, ···, nc for sam-pling unit i, βkj is the regression coefficient that measure how species j responds to covariate k, ηih is the latent factor h = 1, ···, nf, and the factor loading λjh measures how species j responds to the latent factor h. In the model without spatial structure (M_id), the latent factors are assumed to be normally distributed with zero mean and unit variance (Bhattacharya and Dunson, 2011), ηih ~ N (0, 1). To bring spatial structure for the latent factors (M_sp), we assume the exponential function fh (dii') = exp (−dii' /αh) in the variance-covariance matrix of ηih, where dii' is the spatial distance between the sampling units i and i', αh is the spatial scale of the latent factor h.

Options for error distributions include 'normal distribution' for continuous data, 'probability distribution' for presence-absence data, and 'poisson distribution' for count data, and the log-transformed normal distribution was chosen for this study. The modelling framework offer great flexibility for the analysis of species distribution data, and can be more easily extended to include more complex structure (Latimer et al., 2006).

2.3 Model FittingIn this study, we examined different structures of random effects to address the existence of spatial associations and spatial dependence. Accordingly, three HMSC model types were developed, including models without random effects (M_nr), models with independent random effects (M_id), and models with spatial random effects (M_sp). Among them, M_nr was essentially a multivariate regression model with only environmental variables, which meant spatial associations were not considered in this model. M_id included random effects that were independent among the sampling sites investigated, which accounted for the potential spatial associations. M_sp incorporated spatial random effects according to the latitude and longitude of the sampling location, which addressed both spatial associations and spatial dependence, so that samples in close proximity are closely correlated with each other (Defeo et al., 2017). The influences of spatial random effects on the HMSC model were evaluated based on the differences in the outputs of the three models in terms of fitting and predictions.

In all the models above, relative biomass data were used as the response variable, log-transformed (ln(Y + 1)) to minimize the effect of extreme values and to satisfy the requirements of the HMSC model as the log-normal distribution. The measured environmental variables, including water depth, bottom water temperature, bottom salinity, and Chl-a concentration, were used as candidate explanatory variables, which were then selected with a step-wise approach. The final choice of environmental variables to be included in the model was based on the WAIC (Widely Applicable Information Criterion) value of the corresponding model, and a smaller WAIC value indicates a better model fit (Ovaskainen and Abrego, 2020). Considering the possibility of linear and non-linear relationships between environmental factors and biomass (Guan et al., 2009), quadratic terms of the environmental variables were included as predictors to accommodate the non-linear response to environmental factors. Additionally, the values of effective sample sizes (ess) and potential scale reduction factors (psrf) were used to evaluate the convergence of model fitting with MCMC sampling of the model (Ovaskainen and Abrego, 2020). The larger the value of ess, the weaker the autocorrelation between the variables, and the closer the upper limit of the value of psrf is to 1, the better the convergence of model fitting with MCMC sampling of the model.

2.4 Model EvaluationBased on the optimal models selected for different ran-dom effect structures, the fitting and prediction of different models were evaluated and compared. We firstly examined the variance of the community distribution explained by environmental variables and random effects in the three models. The variance partitioning was implemented by computing Variance-Partitioning function in the 'HMSC' package, which calculated the relative contribution of each fixed or random effect to the total explainable variance. We further compared the fitted relationships between environmental factors and biological responses in different models. The construct Gradient function of the 'HMSC' package was used to construct an environmental gradient on the environmental data, and the predict function was used to predict the response of different species to the concerned environmental factors, given all other environmental factors fixed.

The predictive performances of the models were assessed using the cross-validation method. Two indicators, RMSE (root mean squared error) and R2 (coefficient of determination), were used to assess the degree of fit and predictability of the model. RMSE measures the deviation of the predicted value from the true value (Hyndman and Koehler, 2006).

| $ RMSE = \frac{1}{n}\sqrt {\sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {{{({O_i} - {P_i})}^2}} }, $ | (1) |

where Oi denotes the true value, and Pi denotes the predicted value. n is the number of observations.

R2 measures the correlation between observation and predictions, ranging between 0 and 1, with the R2 value closer to 1 indicating the better model fit or prediction (Xu et al., 2015).

| $ {R^{\text{2}}} = 1 - \frac{{SSE}}{{SST}}, $ | (2) |

where SSE stands for sum of squared errors, and SST stands for sum of squared total deviations.

Considering the influence of data size on the predictive performance of SDMs, we simulated different levels of data availability in this study. Specifically, 50, 100, and 150 sampling sites were randomly drawn from 155 stations in the coastal waters of Shandong to construct three sample size gradients, and three versions of the HMSC models were developed, predicted, and evaluated, respectively, in order to evaluate the data-dependent performances. A two-fold cross-validation was used in the model predictability assessment, i.e., the raw data was randomly divided into two sets, where 50% was selected as the training set to build the model and the remaining 50% was used as the validation set to assess the predictive performance of the model. RMSE and R2 were calculated for each prediction separately to indicate the prediction ability of their model, and this process was repeated 100 times.

3 Results 3.1 Optimal ModelsAs the WAIC value was not available (Infinitely) for M_nr, the AIC value was used insteadly for model selection here. The variables selected based on the AIC values were slightly different from those of WAIC, mainly because of the random effects included in other models. Based on the WAIC values, the environmental variables selected were water depth, bottom water temperature (SBT) and chlorophyll-a concentration (Chl-a) (Table 2). In the comparison of random effect models, M_sp always had a relatively smaller WAIC than that of M_id with the same environmental variables, and the optimal M_sp had the lowest WAIC value of 2045 (Table 2). In all three optimal models, SBT and Chl-a had a quadratic relationship with the response variable.

|

|

Table 2 Environment variable selection for HMSC models |

Overall, all three models had ess larger than 1000 and psrf values around the value of 1, indicating satisfying convergence (Table 3). However, M_sp had a relatively smaller value of ess and a larger value of psrf compared to the other two models. Comparison of the ess and psrf values for β (the regression coefficients from fixed effects represent species niches) and Ω (species-to-species covariances from random effects) of M_sp revealed that the autocorrelation of the β parameter was significantly lower than that of the Ω parameter (Table 3).

|

|

Table 3 Convergence examination of the major parameters (mean value) in HMSC for major fishery species in the coastal waters of Shandong Province |

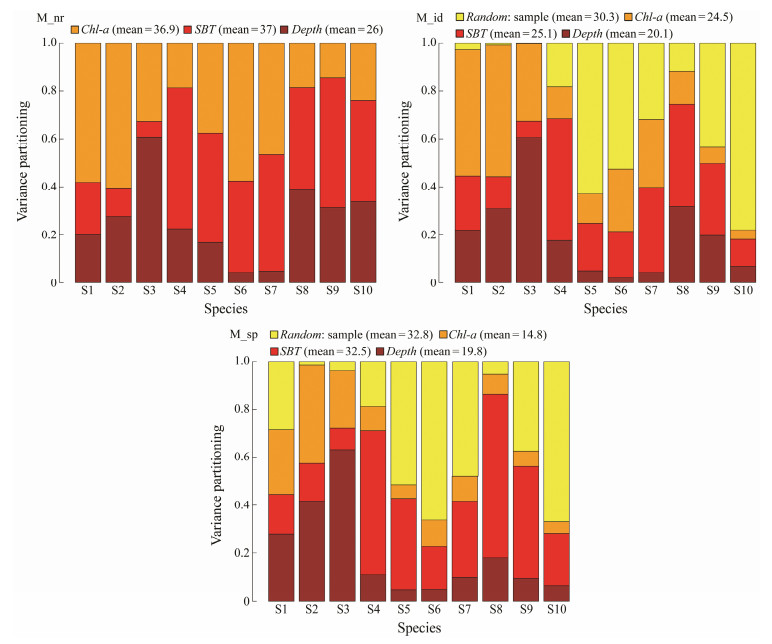

We examined the division of variance among explanatory variables to delineate the contribution of each environmental factor to the fitting of these three different models. For the fixed effects, the variance partitioning showed that SBT provided the largest explainable proportion relative to the other environmental factors, with 37%, 25.1%, and 32.5% in the three models, respectively (Fig.2). Chl-a provided secondary contribution to explained variations, with 36.9% and 24.5% in M_nr and M_id, respectively, and much lower value of 14.8% in M_sp. Water depth showed the least percentage of explained variations in M_nr and M_id. Regarding the role of random effects, the percentage values of explained variations were large in both M_id and M_sp, which were 30.3% and 32.8%, respectively.

|

Fig. 2 Variance partitioning of explained rates for 10 fish and shrimp species in the coastal waters of Shandong Province. The values indicate the proportion of explained variance corresponding to water depth (Depth), bottom water temperature (SBT), and chlorophyll-a concentration (Chl-a), as well as the random effects in HMSC. |

In addition, the contribution of fixed and random factors varied substantially among species. For S5 (Pinkgray goby), S6 (Chub mackerel) and S10 (Japanese snapping shrimp), random effects accounted for more than half of the explained variance. For S1 (Fang's blenny) and S7 (Japanese anchovy), the relative contribution of random effects was significantly smaller in M_id than in M_sp (Fig.2).

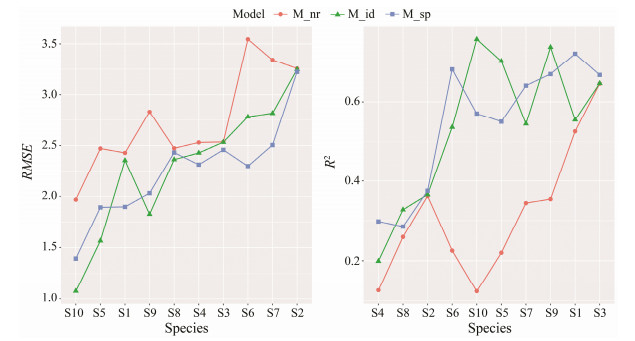

We further examined the results of model fitting for each species using RMSE and R2 (Fig.3). The RMSE of the fitted M_nr were larger than those of the other models, and R2 were smaller for all 10 species. M_id and M_sp showed comparable performances, where M_id had better fitting for S5, S8 (Japanese sand shrimp), S9 (Mantis shrimp), and S10, while M_sp had better fitting for the others. It should be noted that all the models showed poor fitting to some species, such as S4 (branded goby), and fair performances for others, such as S1 and S3 (Tanaka's snailfish). In addition, the three models showed similar results for some species, including S2 (yellow goosefish), S3 and S8, consistent with the results that random effects played a trivial role in the explained variations for those species.

|

Fig. 3 Comparison of the model fitting of three HMSC models for the major species in the coastal waters of Shandong Province. The species were ranked according to the metrics in Y-axes for clearer display. |

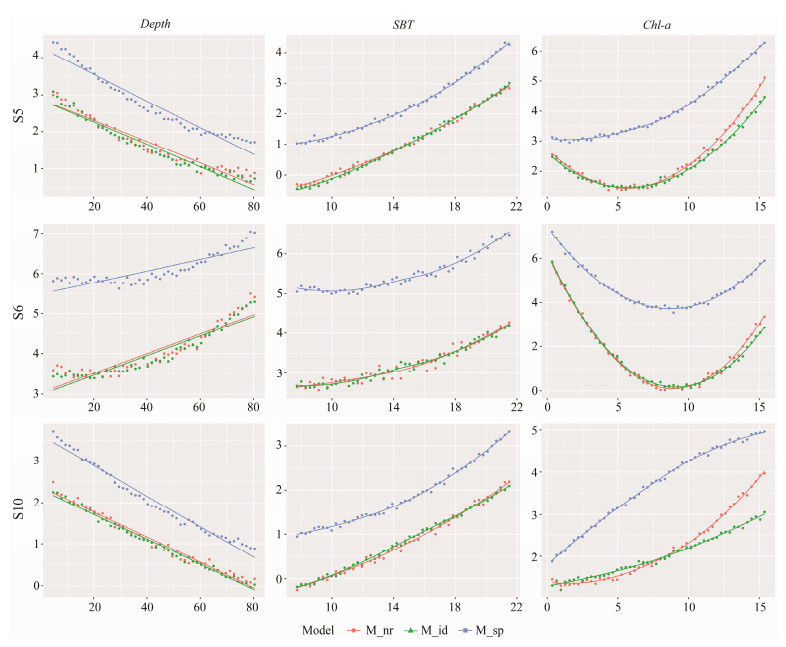

For each species, the three models differed in predicting species responses to environmental factors. In particular, the predicted response curve by M_sp was substantially different from those of the other models, while M_nr and M_id showed more similar predictions. Taking S5 as an example (Fig.4), all three models showed that there was a negative correlation between the species and water depth, a positive correlation with bottom water temperature, and a significant non-linear relationship with Chl-a. However, the effects of each environmental variable became significantly stronger in M_sp. For Chl-a, the M_nr and M_id predicted a low biomass of pinkgray goby at about 5 mg m−3, significantly different from the shape of the M_sp curve. The results were similar for S6 and S10, where all three models showed consistent correlation with water depth and bottom water temperature, and nonlinear relationship with Chl-a, while the effect in M_sp remained stronger than in the other two models.

|

Fig. 4 Response of three selected species to environmental factors predicted by HMSC models in the coastal waters of Shandong Province. |

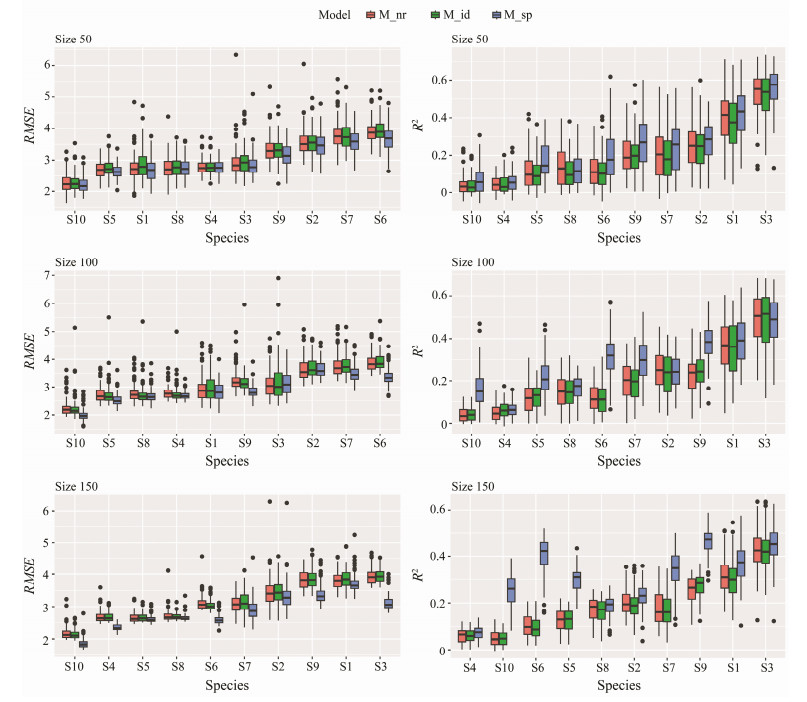

We used the three models to predict the spatial distribution of the 10 species in the coastal waters of Shandong. We examined the RMSE and R2 of the 10 species corresponding to each of the three models for three sample sizes (Fig.5, the results were ranked from the smallest to the largest according to their mean values).

|

Fig. 5 Comparison of the prediction performance of three HMSC models for major species in the coastal waters of Shandong Province. The species were ranked according to the metrics in Y-axes for clearer display. |

Overall, the predictive power of the model gradually improved as the sample size increased. At low sample size levels (size = 50), the average RMSE of M_nr, M_id, and M_ sp ranged 2.26 – 3.89, 2.27 – 3.93, and 2.21 – 3.66, respectively, with small differences among the models. The RMSE of M_sp was slightly lower than that of the two models. At the medium sample size level (size = 100), there was a significant decrease in prediction errors relative to the low sample size scenario, and the mean RMSEs of M_nr, M_ id, and M_sp took values ranging from 2.26 to 3.89, 2.25 to 3.91, and 1.99 to 3.64, respectively. The range of RMSE values for M_nr remained essentially unchanged, the RMSE values for M_id decreasing slightly, and for M_sp was much lower. At a high sample size level (size = 150), the average RMSE further decreased, and the differences between M_sp and the other two models increased substantially (Fig.5).

The results for R2 were similar, i.e., at low sample size, there was little difference in the results of the three models, with R2 below 0.2 for most of the species; at 50 size levels, the average R2 of M_nr, M_id, and M_sp were 0.206, 0.193, and 0.241, respectively. Whereas the improvement of M_sp was obvious as the sample sizes increased, with the average R2 above 0.2 for almost all species at high sample sizes. With 150 samples, the average R2 of M_nr, M_id, and M_sp were 0.189, 0.186, and 0.306, respectively.

4 Discussion 4.1 Spatial Random EffectsThe analysis of spatial distribution is complicated by the presence of spatial autocorrelation, which may confound the results of species distribution model (Dormann et al., 2007). As Zimmermann et al. (2010) pointed out, for most studies that spatial stability is assumed, i.e., the effects of spatial autocorrelation and environmental correlation are constant throughout the study area, which might ultimately bias the model results. This study analyzed the effect of incorporating spatial random effects on the predictive performance of the model using the HMSC framework that had been recently developed. Based on a Bayesian approach, this framework allowed flexibility in integrating observation bias, missing data, and spatial structure of data, and more readily include complex structures compared to traditional species distribution models (e.g., GLM and GAM) (Gelfand et al., 2005; Latimer et al., 2006). Compared to the models without random effects or with independent random effects, the inclusion of spatial random effects substantially improved the performances of HMSC, indicating the necessity of accounting for spatial autocorrelation, which was consistent with the conclusion of Zhang et al. (2022). In addition, failure to account for spatial autocorrelation may lead to imprecision and inaccuracy in parameter estimates, inferences about the significance of explanatory variables and model predictions (Cliff and Ord, 1981). Therefore, we recommend to incorporate spatial random effects into JSDMs in future studies to provide insight into the underlying mechanisms that shape species distribution.

As mentioned above, spatial autocorrelation can reflect biological processes such as dispersal, important environmental factors that were not considered in the study, or nonlinear effects that were not adequately captured, which cannot be handled by non-spatial models (Legendre et al., 2002). In any case, spatial autocorrelation has large impacts on statistical inference from spatial data (Dormann, 2007). Dormann et al. (2007) noted that spatial autocorrelation in species distribution models might bias coefficient estimates, which was consistent with our examination on the speciesenvironment relationships in HMSC. In addition, for the three models in this study, M_nr (without random effects) had the lowest R2 corresponding to each species, suggesting that the model fitted poorly when random effects were not considered. On the contrary, the models with too much flexibility in random effects could be overfitted (Zhang et al., 2022), for example, M_id that assumed independent random effects among sampling sites had an R2 values of 0.8 when fitting some species such as S9 (Mantis shrimp) and S10 (Japanese snapping shrimp), whereas the R2 values were substantially reduced in the prediction, implying a fair possibility of overfitting in M_id. In this sense, M_sp that constrained the random effects by spatial autocorrelation provided better performances by reducing the chances of overfitting as indicated by the WAIC values (Table 2).

Meanwhile, it is important to note that the role of spatial random effects in HMSC do not directly account for the underlying mechanisms of spatial autocorrelation. Many ecological processes may lead to the emerge of spatial autocorrelation, such as external environmental and historical factors limiting the movement of organisms, dispersal mechanisms of organisms, and other behavioral factors leading to the spatial aggregation of species (Dormann et al., 2007). In addition, spatial autocorrelation can also be attributed to observational bias as well as differences in the sampling scheme (Warton et al., 2015), so the specific factors of spatial autocorrelation are difficult to identify. We emphasize that the estimates of latent variables in HMSC cannot provide direct evidence for any of the specific reasons, but should be interpreted from ecological inferences with necessary supportive information.

4.2 Response to Environmental FactorsOur results of variance partitioning showed that both independent random effects and spatial random effects accounted for a large proportion of explainable variance for the 10 fish and shrimp species (Fig.2). This suggested that most species distributions were influenced not only by the three environmental variables considered in this study, but also by other unmeasured biotic or abiotic factors, as pointed out by Warton et al. (2015). In the HMSC models, random effects are represented by latent variables, which may correspond to interactions between species, encompassing the spatial attraction of species to each other (Cheng and Zhou, 1997), or they may represent the effects of missing environmental factors, which need to be interpreted in the context of biological or ecological information. In our studied species assemblage, the large contribution of random effects in S5 (pinkgray goby), S6 (chub mackerel), S7 (Japanese anchovy), S9 (mantis shrimp), and S10 (Japanese snapping shrimp) may be due to the fact that shrimps are the dominant prey for most fishes (Zhu, 1989), leading to strong biotic interactions among the species. The proportion of explained variance for S1 (Fang's blenny) was larger by the spatial random effects than the independent random effects, suggesting that Fang's blenny may be more spatially correlated to other species. The results also suggest the advantages of joint species distribution model over the traditional species distribution model, as species are closely related to each other through biological processes such as predation, competition, and mutualistic co-existence, thus single-species distribution models lead to an unnecessary loss of information (Zhang et al., 2018).

In terms of predicting species response to environment-tal factors (Fig.4), the outputs of M_nr and M_id were quite similar, while M_sp was significantly different. However, the trends of species' responses to environmental factors were generally consistent, and in line with our knowledge about the basic ecological traits of each species. For example, water depth is an important factor influencing the distribution of species in most studies of the marine environment, as it can directly affect various hydrological conditions, including transparency, Chl-a content, salinity, and flow velocity (Chen, 2017). And in this study, there was a negative correlation between the biomass of the pinkgray goby and water depth, due to the species' habitat preference in shallow depths along the Shandong coast (Cheng and Zhou, 1997). Similarly, according to their living habitat, Japanese snapping shrimps are more likely to be found in shallow water (Zhu, 1989), whereas chub mackerel are more likely to be found in deeper water (Cheng and Zhou, 1997), resulting in negative or positive correlation in the fitted models, respectively. Additionally, the species response to Chl-a concentration is also consistent with ecological understanding. As Chl-a mainly reflects the level of primary productivity in the marine environment, and mackerel, a pelagic fish, is more closely related to plankton (Cheng and Zhou, 1997) and more influenced by Chl-a concentration. Similarly, Japanese drum shrimp, a crustacean arthropod that mainly uses phytoplankton as prey, also has a positive correlation with Chl-a concentration (Zhu, 1989). The results suggest that the specification of random effects in HMSC does not impact the inferences of species response to environment in the qualitative sense, but substantially changes the quantitative results.

4.3 Effect of Sample SizeThis study showed that the effects of increasing sample size differed among the HMSC models specified with different random structures (Fig.5). Specifically, there were no significant changes in the R2 values of the predictive results in M_nr and M_id as the sample size increases. In other word, with the increase of sample size, the prediction accuracy of M_nr and M_id was not obviously improved, which means that increasing the survey stations and improving the sample size is less useful or cost-effective for the improvement of model prediction, and further optimization must be carried out by improving the model structure. For M_sp model, the results were mixed, i.e., the R2 corresponding to S5 (pinkgray goby), S6 (chub mackerel), S7 (Japanese anchovy), S9 (mantis shrimp), and S10 (Japanese snapping shrimp) were significantly improved at the high sample sizes, whereas for S4 (branded goby), the predicted R2 was consistently low in all three models. In addition, for S1 (Fang's blenny) and S3 (Tanaka's snailfish), the predictive R2 was fair in the three models, and the performances did not improve significantly with increasing sample size. This might be due to the relatively large biomass and clear distributional characteristics of these species, which made predictions achieved using simple models with common environmental factors (Mod et al., 2015). Hernandez et al. (2006) pointed out that models with a small sample size could be appropriate for some habitat-specific species, while widely distributed species were more difficult to predict (Elith et al., 2006), which could also explain the species-specific differences in predictability. The results implied that the differences in data quality as well as differences in the species attribution may dominate the performances of different modeling approaches (Araújo and Williams, 2000).

On the other hand, overall M_sp outperformed M_nr and M_id in prediction, reaching larger R2 values with large sample sizes. Therefore, the inclusion of spatial random effects in the model would greatly improve the predictive power of the model, confirming the result of Ovaskainen et al. (2016b). However, it should be noted that the model with spatial random effects was less stable compared to the other two models, showing superior performances only in the larger sample sizes. Therefore, in practice, we recommend to develop more complex models for predictive analyses based on larger sample sizes to achieve the most reliable results. In addition, spatial random effects were not always effective for different species. For example, for S2 (yellow goosefish) and S8 (Japanese sand shrimp), although the average biomass was also larger, the R2 value did not significantly increase with increasing sample size, probably because the species were not affected by the latent variables identified by HMSC (Zhang et al., 2020). In particular, the prediction of rare species whose data are unavailable may be investigated firstly by choosing simpler distribution models

4.4 Shortcomings and ProspectsIn this study, the cross-validation method was used to evaluate the predictive performances of HMSC with respect to spatial random effects. As the processes of cross-validation resample data within the surveyed area, and because spatial autocorrelation exists between the training and the validating data, the tests are not truly independent, which may result in over-optimistic results of species distribution (Hernandez et al., 2006). As the pattern of species interactions or their dependence on latent variables may change over time and space, the treatment of spatial autocorrelation could become problematic when the model is projected to a new geographic region or time period. Similarly, the use of non-linear predictors and interactions between environmental variables might enhance the model fit but could impair the transferability of the model in time and space at the same time (Wood, 2017). Therefore, further studies on the predictive models with independent data for training and testing are needed, and the structural complexity of JSDMs should be carefully considered with respect to the research purpose especially in the case of extrapolation.

In addition, this study showed that the predictive accuracy varied considerably for different species in the models, with different responses to model structure and sample size, which may be attributed to the ecological characteristics of the species per se (Lin et al., 2023). Many researchers have concerned that species traits may affect the accuracy of model predictions (Bartolino et al., 2011; Compton et al., 2012; Grüss et al., 2017) and there were strong relationships between model performance and the spatial extent, tolerance and marginality of species distributions (Hernandez et al., 2006). Therefore, species traits should also be considered in multispecies distribution modelling for future studies to enhance model predictability, which is helpful to provide reliable scientific advices for supporting ecological conservation and management programs.

5 ConclusionsIn this study, we used the HMSC framework to model the multispecies distribution of a marine fish assemblage, in which spatial associations and spatial dependence was deliberately accounted for. We tested different structures of random effects to address the existence of spatial associations and spatial dependence, and assessed the predictive performances at different levels of sample sizes. Our results demonstrated that spatial random effects could substantially influence the results of the joint species distribution, and increasing sample size had a strong effect on the predictive accuracy of the spatially-structured model, suggesting that optimal model selection should be dependent on sample size. In addition, this study showed that the predictive accuracy varied considerably among different species in the models, which may be attributed to the ecological characteristics of the species per se. Therefore, species traits should also be considered in multispecies distribution modelling for future studies to enhance model predictability. The results of this study may contribute to providing reliable scientific advices for ecological conservation and management programs.

AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to our colleagues and the students in our laboratory for their work in field sampling and sample analyses. This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFD2401301).

Author Contributions

Tianheng Xu and Chongliang Zhang conceived the working hypotheses and study design. Tianheng Xu led the literature research on species distribution and ecological modelling. Chongliang Zhang led operation of statistical analyses. Tianheng Xu collated and analysed the data and led the writing. All authors critically edited manuscript drafts.

Data Availability

The data and references presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The present study was performed according to the standard operation procedures (SOPs) of the Guide for the Use of Experimental Animals of the Ocean University of China. All animal care and use procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ocean University of China.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Anselin, L., 2013. Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models. Springer Science & Business Media, 160pp.

(  0) 0) |

Araújo, M. B., and Williams, P. H., 2000. Selecting areas for species persistence using occurrence data. Biological Conservation, 96(3): 331-345. DOI:10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00074-4 (  0) 0) |

Bhattacharya, A., and Dunson, D. B., 2011. Sparse Bayesian in-finite factor models. Biometrika, 98(2): 291-306. DOI:10.1093/biomet/asr013 (  0) 0) |

Bond, N., Thomson, J., Reich, P., and Stein, J., 2011. Using spe-cies distribution models to infer potential climate change-induced range shifts of freshwater fish in south-eastern Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research, 62(9): 1043-1061. DOI:10.1071/MF10286 (  0) 0) |

Chen, C., Gao, G., Zhang, Y., Beardsley, R. C., Lai, Z., Qi, J., et al., 2016. Circulation in the Arctic Ocean: Results from a high-resolution coupled ice-sea nested Global-FVCOM and Arctic-FVCOM system. Progress in Oceanography, 141: 60-80. DOI:10.1016/j.pocean.2015.12.002 (  0) 0) |

Chen, X. J.,, 2017. Fisheries Resources and Fishing Grounds. China Ocean Press, Beijing, 460pp.

(  0) 0) |

Cheng, Q. T., and Zhou, C. W.,, 1997. Ichthyology of Shandong Province. Shandong Science and Technology Press, Jinan, 256pp.

(  0) 0) |

Clark, J. S., Gelfand, A. E., Woodall, C. W., and Zhu, K., 2014. More than the sum of the parts: Forest climate response from joint species distribution models. Ecological Applications, 24(5): 990-999. DOI:10.1890/13-1015.1 (  0) 0) |

Cliff, A. D., and Ord, J. K., 1981. Spatial Processes: Models & Applications. Taylor & Francis, 237pp.

(  0) 0) |

Compton, T. J., Morrison, M. A., Leathwick, J. R., and Carbines, G. D., 2012. Ontogenetic habitat associations of a demersal fish species, Pagrus auratus, identified using boosted regression trees. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 462: 219-230. DOI:10.3354/meps09790 (  0) 0) |

Cressie, N., 2015. Statistics for Spatial Data. John Wiley & Sons, 887pp.

(  0) 0) |

Defeo, O., Barboza, C. A., Barboza, F. R., Aeberhard, W. H., Cabrini, T. M., Cardoso, R. S., et al., 2017. Aggregate patterns of macrofaunal diversity: An interocean comparison. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 26(7): 823-834. DOI:10.1111/geb.12588 (  0) 0) |

Dormann, C. F., 2007. Assessing the validity of autologistic re-gression. Ecological Modelling, 207(2-4): 234-242. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.05.002 (  0) 0) |

Dormann, C. F., McPherson, J. M., Araújo, M. B., Bivand, R., Bolliger, J., Carl, G., et al., 2007. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data: A review. Ecography, 30(5): 609-628. DOI:10.1111/j.2007.0906-7590.05171.x (  0) 0) |

Elith, J., Graham, C. H., Anderson, R. P., Dudík, M., Ferrier, S., Guisan, A., et al., 2006. Novel methods improve prediction of species' distributions from occurrence data. Ecography, 29(2): 129-151. DOI:10.1111/j.200-6.0906-7590.04596.x (  0) 0) |

Gelfand, A. E., Schmidt, A. M., Wu, S., Silander Jr., J. A., La-timer, A., and Rebelo, A. G., 2005. Modelling species diversity through species level hierarchical modelling. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C: Applied Statistics, 54(1): 1-20. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9876.2005.00466.x (  0) 0) |

González-Andrés, C., Sanchez-Lizaso, J. L., Cortés, J., and Pen-nino, M. G., 2021. Predictive habitat suitability models to aid the conservation of elasmobranchs in Isla del Coco National Park (Costa Rica). Journal of Marine Systems, 224: 103643. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2021.103643 (  0) 0) |

Griffith, D. A., and Peres-Neto, P. R., 2006. Spatial modeling in ecology: The flexibility of eigenfunction spatial analyses. Ecology, 87(10): 2603-2613. DOI:10.1890/00129658(2006)87-[2603:SMIETF]2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Grüss, A., Thorson, J. T., Sagarese, S. R., Babcock, E. A., Karnauskas, M., Walter Ⅲ, J. F., et al., 2017. Ontogenetic spatial distributions of red grouper (Epinephelus morio) and gag grouper (Mycteroperca microlepis) in the US Gulf of Mexico. Fisheries Research, 193: 129-142. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2017.04.006 (  0) 0) |

Guan, W. J., Chen, X. J., Gao, F., and Li, G., 2009. Environmental effects on fishing efficiency of Scomber japonicus for Chinese large lighting purse seine fishery in the Yellow and East China Seas. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 16(6): 949-958 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Hartman, L., and Hössjer, O., 2008. Fast kriging of large data sets with Gaussian Markov random fields. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 52(5): 2331-2349. DOI:10.1016/j.csda.2007.09.018 (  0) 0) |

Hernandez, P. A., Graham, C. H., Master, L. L., and Albert, D. L., 2006. The effect of sample size and species characteristics on performance of different species distribution modeling methods. Ecography, 29(5): 773-785. DOI:10.1111/j.09067590.20-06.04700.x (  0) 0) |

Hyndman, R. J., and Koehler, A. B., 2006. Another look at mea-sures of forecast accuracy. International Journal of Forecasting, 22(4): 679-688. DOI:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.03.001 (  0) 0) |

Kissling, W. D., Dormann, C. F., Groeneveld, J., Hickler, T., Kühn, I., McInerny, G. J., et al., 2012. Towards novel approaches to modelling biotic interactions in multispecies assemblages at large spatial extents. Journal of Biogeography, 39(12): 2163-2178. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02663.x (  0) 0) |

Kühn, I., 2007. Incorporating spatial autocorrelation may invert observed patterns. Diversity and Distributions, 13(1): 66-69. DOI:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2006.00293.x (  0) 0) |

Latimer, A. M., Wu, S., Gelfand, A. E., and Silander Jr., J. A., 2006. Building statistical models to analyze species distributions. Ecological Applications, 16(1): 33-50. DOI:10.1890/04-0609 (  0) 0) |

Legendre, P., 74. Spatial autocorrelation: Trouble or new para-digm?. Ecology, 6: 1659-1673. DOI:10.2307/1939924 (  0) 0) |

Legendre, P., and Fortin, M. J., 1989. Spatial pattern and ecolo-gical analysis. Vegetatio, 80: 107-138. DOI:10.1007/BF00048036 (  0) 0) |

Legendre, P., and Legendre, L., 2012. Numerical Ecology. Else-vier, 870pp.

(  0) 0) |

Legendre, P., Dale, M. R., Fortin, M. J., Gurevitch, J., Hohn, M., and Myers, D., 2002. The consequences of spatial structure for the design and analysis of ecological field surveys. Ecography, 25(5): 601-615. DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0587.2002.250508.x (  0) 0) |

Lin, L., Liu, Y., Yan, Y., and Kang, B., 2023. Optimizing efficiency and resilience of no-take marine protected areas for fish conservation under climate change in coastal China Seas. Conservation Biology: The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology, 38(2): e14174. DOI:10.111-1/cobi.14174 (  0) 0) |

Marzloff, M. P., Melbourne-Thomas, J., Hamon, K. G., Hoshino, E., Jennings, S., Van Putten, I. E., et al., 2016. Modelling marine community responses to climate-driven species redistribution to guide monitoring and adaptive ecosystem-based management. Global Change Biology, 22(7): 2462-2474. DOI:10.1111/gcb.13285 (  0) 0) |

Mod, H. K., le Roux, P. C., Guisan, A., and Luoto, M., 2015. Biotic interactions boost spatial models of species richness. Ecography, 38(9): 913-921. DOI:10.1111/ecog.01129 (  0) 0) |

Ovaskainen, O., Abrego, N., Halme, P., and Dunson, D., 2016a. Using latent variable models to identify large networks of speciesto-species associations at different spatial scales. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7(5): 549-555. DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.12501 (  0) 0) |

Ovaskainen, O., and Abrego, N.,, 2020. Joint Species Distribution Modelling: With Applications in R. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 372pp.

(  0) 0) |

Ovaskainen, O., Hottola, J., and Siitonen, J., 2010. Modeling species co-occurrence by multivariate logistic regression generates new hypotheses on fungal interactions. Ecology, 91(9): 2514-2521. DOI:10.1890/10-0173.1 (  0) 0) |

Ovaskainen, O., Roy, D. B., Fox, R., and Anderson, B. J., 2016b. Uncovering hidden spatial structure in species communities with spatially explicit joint species distribution models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7(4): 428-436. DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.12502 (  0) 0) |

Ovaskainen, O., Tikhonov, G., Dunson, D., Grøtan, V., Engen, S., Sæther, B. E., et al., 2017a. How are species interactions structured in species-rich communities? A new method for analysing time-series data. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1855): 20170768. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2017.0768 (  0) 0) |

Ovaskainen, O., Tikhonov, G., Norberg, A., Blanchet, F. G., and Abrego, N., 2017b. How to make more out of community data? A conceptual framework and its implementation as models and software. Ecology Letters, 20(5): 561. DOI:10.1111/ele.12757 (  0) 0) |

Pinheiro, J., and Bates, D., 2006. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS. Springer Science & Business Media, 1135pp.

(  0) 0) |

Poggiato, G., Münkemüller, T., Bystrova, D., Arbel, J., Clark, J. S., and Thuiller, W., 2021. On the interpretations of joint modeling in community ecology. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 36(5): 391-401. DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2021.01.002 (  0) 0) |

Pollock, L. J., Tingley, R., Morris, W. K., Golding, N., O'Hara, R. B., Parris, K. M., et al., 2014. Understanding co-occurrence by modelling species simultaneously with a Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5(5): 397-406. DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.12180 (  0) 0) |

Thorson, J. T., Scheuerell, M. D., Shelton, A. O., See, K. E., and Kristensen, K, 2015. Spatial factor analysis: A new tool for estimating joint species distributions and correlations in species range. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 6(6): 12359. DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.12359 (  0) 0) |

Warton, D. I., Blanchet, F. G., O'Hara, R. B., Ovaskainen, O., Taskinen, S., Walker, S. C., et al., 2015. So many variables: Joint modeling in community ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30(12): 766-779. DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.007 (  0) 0) |

Wilkinson, D. P., Golding, N., Guillera-Arroita, G., Tingley, R., and McCarthy, M. A., 2019. A comparison of joint species distribution models for presence-absence data. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 10: 198-211. DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.13106 (  0) 0) |

Wilkinson, D. P., Golding, N., Guillera-Arroita, G., Tingley, R., and McCarthy, M. A., 2021. Defining and evaluating predictions of joint species distribution models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 12: 394-404. DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.13518 (  0) 0) |

Wisz, M. S., Pottier, J., Kissling, W. D., Pellissier, L., Lenoir, J., Damgaard, C. F., et al., 2013. The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: Implications for species distribution modelling. Biological Reviews, 88(1): 15-30. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00235.x (  0) 0) |

Wood, S. N.,, 2017. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 496pp.

(  0) 0) |

Xu, B. D., Zhang, C. L., Xue, Y., Ren, Y. P., and Chen, Y., 2015. Optimization of sampling effort for a fishery-independent survey with multiple goals. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 187: 1-16. DOI:10.1007/s10661-015-4483-9 (  0) 0) |

Zeng, Y., and Wiens, J. J., 2021. Species interactions have pre-dictable impacts on diversification. Ecology Letters, 24(2): 239-248. DOI:10.1111/ele.13635 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, C. L., Chen, Y., Xu, B. D., Xue, Y., and Ren, Y. P., 2018. Comparing the prediction of joint species distribution models with respect to characteristics of sampling data. Ecography, 41(11): 1876-1887. DOI:10.1111/ecog.03571 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, C. L., Chen, Y., Xu, B. D., Xue, Y., and Ren, Y. P., 2019. How to predict biodiversity in space? An evaluation of modelling approaches in marine ecosystems. Diversity and Distributions, 25(11): 1697-1708. DOI:10.1111/ddi.12970 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, C. L., Xu, B. D., Xue, Y., and Ren, Y. P., 2020. Evaluating multispecies survey designs using a joint species distribution model. Aquaculture and Fisheries, 5(3): 156-162. DOI:10.101-6/j.aaf.2019.11.002 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y., Jiao, Y., and Latour, R. J., 2022. Nonlinearity and spatial autocorrelation in species distribution modeling: An example based on weakfish (Cynoscion regalis) in the Mid-Atlantic Bight. Fishes, 8(1): 27. DOI:10.3390/fishes8010027 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y., Yu, H., Zhang, C. L., Xu, B. D., Ji, Y., Ren, Y. P., et al., 2023. Impact of life history stages on fish species interactions and spatio-temporal distribution. Fisheries Research, 266: 106792. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2023.106792 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, N. S.,, 1989. Crustaceology. Science Press, Beijing, 341pp.

(  0) 0) |

Zimmermann, N. E., Edwards Jr., T. C., Graham, C. H., Pearman, P. B., and Svenning, J. C., 2010. New trends in species distribution modelling. Ecography, 33(6): 985-989. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06953.x (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24