2) Scientific Observing and Experimental Station of Fishery Resources for Key Fishing Grounds, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People's Republic of China, Zhoushan 316021, China;

3) Key Laboratory of Sustainable Utilization of Technology Research for Fishery Resources of Zhejiang Province, Zhoushan 316021, China;

4) School of Water Resources & Hydropower Engineering, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China

The East China Sea is located in the western part of the North Pacific Ocean. With a vast continental shelf area and a zigzag coastline, it consists of a large land and marginal sea area (Yagi et al., 2014). Numerous rivers, such as the Yangtze, Qiantang and Aojiang Rivers, flow into the East China Sea and transport large amounts of sediment and nutrient salts. Affected by monsoons and the Kuroshio Current, the East China Sea has complex hydrological characteristics, forming an ecosystem with abundant species and large amounts of biomass. It has sufficient prey organisms and nutrients, and provides good breeding, feeding and overwintering conditions for a variety of fishes. It is an important area for fishery resources (Ichikawa and Beardsley, 2002). Numerous estuaries in the East China Sea area, as the economic hub of the coastal area, have been intensively populated for a long time, which has damaged the marine biological environment to a certain extent, with a declining trend in biological resources and a decrease in biodiversity (Han et al., 2015). As a result of global climate change and overfishing of some fishery resources (Zhang et al., 2018), the fish population structure in the East China Sea area has been characterized by individual miniaturization, underaging, and advancement of sexual maturity, and spawning grounds have been frequently damaged, with a continuous decline in the quality of catches (Zhang et al., 2019). Since the 1990s, deep-water drift-net technology has been introduced in East China Sea waters, and the fishing production for Branchiostegus japonicus has reached a large scale, with its catch ranking first among all types of catch in deep-water drift nets (Bo et al., 2005). Additionally, as the fishery has developed rapidly in recent years, Branchiostegus japonicus becomes an important species in the offshore capture fishery of the East China Sea.

The red tilefish B. japonicus belongs to Perciformes, Branchiostegidae and Branchiostegus, and is a warm-water, high-quality demersal fish distributed in the coastal areas of China, North Korea, Japan and South Korea (Zhu et al., 1963). B. japonicus does not migrate long distances, has cave-dwelling habits, and is mainly caught by deep-water drift nets, with a small amount of bycatch by trawl and longline fishing (Xu et al., 2021). This species has high economic value, and has long been closely scrutinized by scholars (Taek et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2018). Given that B. japonicus is a high-quality benthic fish, its conservation plays an important role in maintaining the diversity of the entire aquatic ecosystem. By conserving this species, other species that depend on it can also be protected. This is conducive to promote the conservation of marine biodiversity. Thus it is important to explore whether the population structure and biological characteristics of B. japonicus have changed in the East China Sea and to determine how this species responds to fishery management measures.

Reproduction can give birth to young juveniles of parental fish and perpetuate the fish population, which includes a series of processes, such as gonadal development, maturation, spawning, and sperm-egg unions (Russo et al., 2022). In the process of adapting to the ever-changing habitats, each fish species has developed a unique reproductive strategy that results in greater adaptability to the environment. Reproductive biology is a prerequisite for the implementation of reproductive strategies in fish (John and Cassandra, 2022). The study of the reproductive biology of fish can help researchers better grasp the dynamic changes in fish populations, which is of practical significance for the conservation and effective utilization of fishery species. B. japonicus is not a traditional fishing target in China, and there are relatively few studies on its reproductive biology, most of which were conducted many years ago (Yamashita et al., 2022). No systematic reports on the reproductive biology of B. japonicus in the East China Sea have been published in recent years. This study was conducted to investigate the reproductive biology of B. japonicus obtained from March to December of 2021 in the East China Sea through assessments of standard length and weight, sex ratio, length at first sexual maturity, reproductive period, fecundity, and spawning type, with the aim of providing basic information for the conservation and sustainable utilization of B. japonicus species.

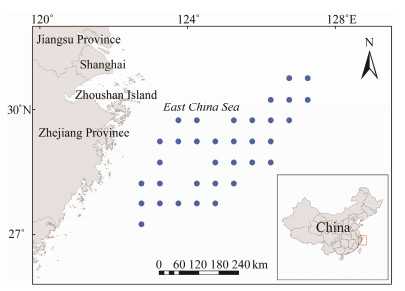

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Data SourceThe samples were caught by the deep-water drift net vessel Zhepu Fishing 72688 and the longline fishing vessel 72666 in the East China Sea. The longline fishing vessel was allowed to be used during the fishing moratorium, which ensured the completeness of the sampling time of this experiment. The collection period was from March to December of 2021, and the sea area covered 27˚00΄ – 31˚00΄N, 122˚30΄ – 127˚30΄E (Fig.1). A total of 461 individuals of B. japonicus were sampled (Fig.2, Table 1). After sampling, the samples were transported to the laboratory to measure standard length, body weight and other conventional biological data; the samples were subsequently dissected and observed. According to the existing standardized stages of gonad development (Yin et al., 1995), gonad development can be divided into six stages, including stages Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅳ, Ⅴ, and Ⅵ. In B. japonicus, the presence of transparent waterabsorbing eggs in the ovary indicates that the female individual is mature. The testis is not filamentous, but has a certain width and thickness, and the presence of milky white semen after crushing means that the male individual is mature (Yamashita et al., 2011). Referring to other researches (Flores et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022), the samples with ovaries that had developed to Stage Ⅲ and above were selected for the determination of the fecundity of B. japonicus in this research. The whole ovary was fixed with an 8% formalin solution, which was used to calculate the fecundity and egg diameter frequency distribution, and biological data such as gonad weight and net weight were also measured.

|

Fig. 1 Sampling stations in the East China Sea. Based on the standard map service website of the Ministry of Natural Resources, GS (2016) No. 2923, the standard map is produced with the base map boundaries unchanged. |

|

Fig. 2 B. japonicus collected from the East China Sea. |

|

|

Table 1 Sample composition of B. japonicus in the East China Sea |

Length metrics for B. japonicus were measured using a straightedge. The standard length is the distance from the anterior tip of the snout to the terminus of the vertebral column, which is accurate to 1 mm. The weight metrics were measured using an electronic balance. The body weight and net weight were accurate to 0.1 g, and the gonad weight was accurate to 0.01 g.

The 50% individual first sexual maturity standard length (L50) was calculated using the logistic regression, where all females used for the characterization of reproductive biology were used to fit a sexual maturity curve and estimate the L50, which was grouped in 10 mm standard length intervals. The proportion of sexual maturity in each standard length group was calculated using the following formula (van der Velde et al., 2009):

| $ P = \frac{1}{{1 + \exp \left[ { k({L_{{\text{Tmid}}}} {L_{50}})} \right]}}. $ | (1) |

Here, P is the proportion of sexual maturity in each standard length group, LTmid is the median of the standard length groups, L50 is the sexually mature standard length of 50% of individuals, and k is a parameter.

The gonadosomatic index (GSI) was calculated as follows:

| $ GSI = 100 \times \frac{{{W_G}}}{{{W_N}}}. $ | (2) |

Here, WG (g) is the gonad weight and WN (g) is the net weight.

Fecundity was calculated using the mass analysis method. After the surface moisture of the 60 mature ovary samples of B. japonicus were collected, 0.05 – 0.15 g samples were randomly selected from the anterior, middle, and posterior portions of each ovary, and the number of eggs was measured by evenly and discretely counting the eggs. This value was then converted to the number of eggs contained in the whole ovary.

Absolute fecundity is calculated as follows:

| $ F = \frac{{{N_{\text{s}}}}}{{{W_{\text{s}}}}} \times {W_G}. $ | (3) |

Here, F (eggs) is the absolute fecundity, Ns (eggs) is the number of egg in the sample, and Ws (g) is the sample mass.

Standard length relative fecundity is calculated as follows:

| $ {F_L} = \frac{F}{L}. $ | (4) |

Here, FL (eggs) is standard length relative fecundity, L (mm) is standard length.

Body weight relative fecundity is calculated as follows:

| $ {F_W} = \frac{F}{W}. $ | (5) |

Here, FW (eggs) is body weight relative fecundity and W (g) is body weight.

The spawning pattern was determined according to the egg diameter frequency distribution of the mature samples during the breeding period. During actual anatomical observation, it was found that the development of eggs in the ovaries of B. japonicus was inconsistent due to the presence of eggs with different sizes. In addition, some ovary samples showed post spawning traces. Thus, individuals with stage Ⅳ ovaries that had not yet shown traces of spawning were selected, and egg diameters were observed and measured by using a LEICA M205 C optical microscope. Here, 50 eggs were randomly measured in each sample, and the frequency distribution of egg diameters was plotted.

Excel 2010 and R (version 4.3.1) software were utilized for relevant data processing and statistical analysis.

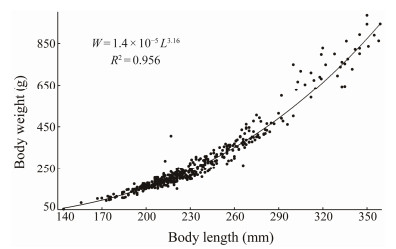

3 Results and Analysis 3.1 Relationship Between Body Weight and Standard LengthA power function relationship existed between the body weight (W) and standard length (L) of B. japonicus, and the regression equation was W = 1.4×10–5 L3.16, R2 = 0.956 (Fig.3).

|

Fig. 3 Relationship between body weight and standard length of B. japonicus in the East China Sea. |

The sex ratio of B. japonicus with different lengths is shown in Table 2. Among the 461 B. japonicus samples, 228 were female, 206 were male, and 27 were juvenile with undefined sex. The group ratio of female to male was 1.11:1, and chi-square test results showed that the ratio of female to male was consistent at 1:1 (χ2 = 1.11, P = 0.291). When the length of B. japonicus was less than 180 mm, there were far more females than males. In the 181 – 260 mm length group, females and males were approximately the same. In the 261 – 300 mm length group, there were fewer males that accounted for only 15% of the total number of males. In the group that the length was more than 300 mm, the proportion of males increased significantly.

|

|

Table 2 Sex ratio in different standard length groups of B. japonicus in the East China Sea |

The sex ratio of B. japonicus differed among months of the year (Table 3). The proportion of males was greater than that of females in March and December. The proportion of females increased significantly in May, which was substantially greater than that of males. From June to November, the proportions of males and females were roughly the same.

|

|

Table 3 Sex ratio of B. japonicus in the East China Sea based on month |

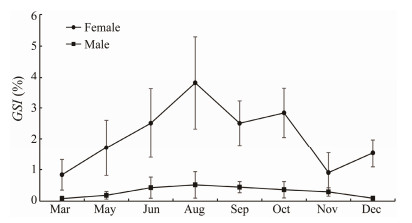

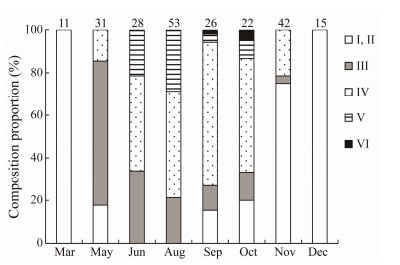

In females, all ovaries in March and December were classified as stages Ⅰ and Ⅱ. The GSI ranged from 0.8% ± 0.6% to 1.5% ± 0.4% (Figs.4 and 5), which is hypothesized to represent the early developmental stage of the ovaries of B. japonicus from December to March of the following year. In May, a large number of stage Ⅲ individuals appeared, accounting for approximately 68% of the total samples, and were accompanied by a small number of stage Ⅳ-developing individuals, with a GSI of 1.7% ± 0.9%. In June, all ovarian individuals were above stage Ⅲ, with stage Ⅲ and Ⅳ predominating, and a few stage Ⅴ individuals appeared, with a gonadal index of 2.5% ± 1.1%. Thereafter, the GSI continued to increase, peaking at 3.8% ± 1.5% in August, with an increase in the number of stage Ⅴ individuals. From September to October, the ovarian individuals were predominantly stage Ⅳ and stage Ⅱ, and mainly postovulatory ovarian recovery individuals. In November the gonadal index decreased to 0.9% ± 0.6%, with fewer stage Ⅳ individuals and predominant stage Ⅱ individuals (Figs. 4 and 5). It is hypothesized that only a small proportion of B. japonicus may still spawn in November. Compared with females, males had smaller GSI, and the trend of GSI was the same as that of females except those in October and December, with more sexually mature individuals observed from May to November.

|

Fig. 4 Changes in the gonadosomatic index (GSI) of B. japonicus in the East China Sea. |

|

Fig. 5 Monthly changes in the composition of each stage of ovarian development of B. japonicus in the East China Sea. |

In summary, it is hypothesized that the spawning period of B. japonicus in the East China Sea is from May to November, and the peak spawning period may be from June to October.

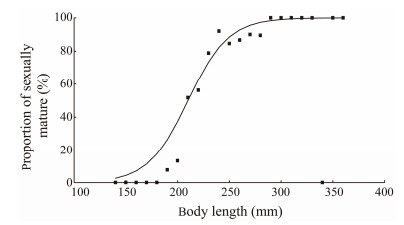

3.4 Length at First Sexual MaturityAmong the individuals with gonadal development at stage Ⅲ and above, the smallest observed sexually mature standard length of B. japonicus was 180 mm, corresponding to a body weight of 113.6 g, a maturity coefficient of 0.87, and a gonadal development of stage Ⅲ. After regression of logistic equations, it was concluded that 50% of B. japonicus individuals had a first-time sexually mature standard length of 210.0 mm, and the relationship between the proportion of sexually mature individuals and the group of standard lengths was P = 1/{1 + exp[−0.051(LTmid − 210.0)]}, R2 = 0.791 (Fig.6).

|

Fig. 6 Proportion of sexually mature individuals in different size classes of B. japonicus in the East China Sea. |

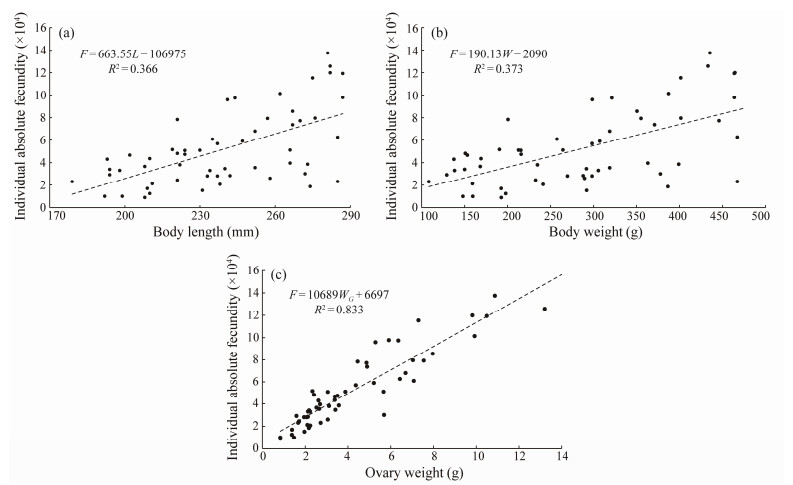

The absolute fecundity of sexually mature B. japonicus ranged from 8795 to 137513 eggs per tail, with a mean value of 51441 ± 33232 eggs per tail. The relative fecundity for standard length ranged from 42 to 489 eggs mm–1, with a mean value of (210 ± 117) eggs mm–1. The relative fecundity for body weight ranged from 46 to 390 eggs g–1, with a mean value of (184 ± 89) eggs g–1. The absolute fecundity was linearly related to standard length, body weight and gonadal weight, and the highest correlation was noted with gonadal weight (Fig.7). The relative fecundity fluctuated within a certain range, and there was no significant trend of change in the relationship between standard length and body weight.

|

Fig. 7 Absolute fecundity in relation to the standard length, body weight and ovary weight of B. japonicus in the East China Sea. |

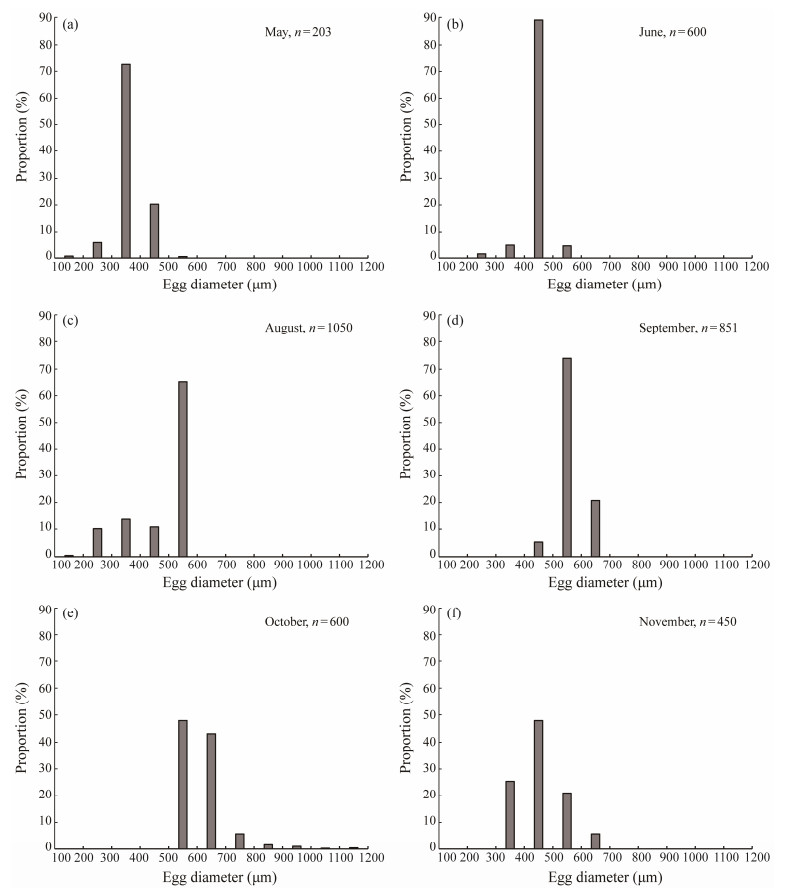

Seventy-five samples at stage Ⅳ of ovarian development were selected, and egg diameters were measured (Fig.8, n = 3754). The range of egg diameters ranged from 0.17 to 1.21 mm, and the average egg diameter was 0.51 mm ± 0.12 mm. The average egg diameter was small in May, which was during the developmental stage. The average egg diameter increased from June to October, which was during the reproductive period. The average egg diameter gradually decreased in November. In addition, the monthly egg diameter distribution had only one peak.

|

Fig. 8 Egg diameter distribution of B. japonicus in the East China Sea in different months. |

The sex ratio is closely related to the fecundity of fish populations and reflects the long-term adaptation of species to their environment (Kobayashi et al., 2011). Generally, the female-to-male ratio of fish populations is close to 1:1 because most fish differentiate between males and females simultaneously. Sexual transition can be completed in the early stages of individual development, and this sex differentiation is genetically controlled (Nitzan et al., 2016). In this study, the sex ratio of B. japonicus in East China Sea waters differed significantly according to standard length, with females far outnumbering males when the standard length was less than 180 mm and males far outnumbering females when the standard length was greater than 300 mm. The phenomena of a large proportion of females in a small breeding population, an equal proportion of males and females in a medium-length population, and a significant increase in males in a large breeding population contrasted with the variation in sex ratios of Scomberomorus niphonius (Mu et al., 2018) and Scomber japonicus (Zhou et al., 2022), which exhibited opposite sex ratio changes. This may be due to different mechanisms controlling the sex ratio in different fish species. Sex ratios can vary across a range of standard lengths and body weights, which is an ecological adaptation that can be determined by the environmental conditions under which populations live and the evolutionary process occurs (Gong et al., 2015). The dominant standard length group in this study ranged from 180 to 300 mm, and the overall sex ratio showed a grester proportion of females than males. In some small-bodied fish populations, females can selectively control their sex ratio to ensure better reproductive success (Cheng et al., 2010), which may result in a greater proportion of females. However, Yamashita (2007) reported that the growth rate of male B. japonicus was faster than that of female B. japonicus. Combined with the large differences in GSI between the sexes in the present study, it is clear that females require more energy for their reproductive activities. It is possible that energy was not fully replenished due to the insufficient feeding capacity and the intensity of feeding during the reproduction period, which resulted in a lower frequency of females than that of males among the large B. japonicus individuals. Moreover, the frequency of females was lower than that of males among large B. japonicus. In addition, larger males may allow males to be more competitive and thus achieve greater reproductive success.

4.2 Reproductive PeriodAccording to Andrés et al. (2007), females with a GSI greater than 2.5% were considered mature individuals. In this study, a few females reached 2.5% GSI in May. In addition, a small number of stage Ⅳ individuals began to appear in August when GSI continued to increase and a maximum value of 3.8% ± 1.5% was observed. A fluctuating trend in the GSI was noted from September to October, but the mean value was still above 2.5%. The trend of GSI change in males was basically the same as that in females. Combined with the proportions of each developmental stage of the ovary in different months, it was hypothesized that the spawning period of B. japonicus in East China Sea waters occurs from May to November, and its peak spawning period may be from June to October. Xia et al. (2005) hypothesized that the spawning period of B. japonicus was June to October, which was basically consistent with the results of this study. Iseki et al. (2022) hypothesized that the spawning period of B. japonicus was from July to October, which was different from the results of this study. The area investigated in their study was the fishing ground of Niigata Prefecture in the northern part of the Sea of Japan. The differences in the habitat environment (e.g., water temperature, salinity, and dissolved oxygen, etc.) and the types of food ingested may affect the gonadal maturation and spawning time of the fish (Zeng et al., 2020). During the reproductive period of fish, the response to the living conditions is more sensitive and stricter, which may lead to changes in the reproduction time of the same fish in different geographical populations. In addition, the reproduction duration of B. japonicus is longer. When external conditions change significantly, population proliferation is not easily affected, which also reflects the response of the reproductive behavior of the fish to environmental factors (Xu et al., 2003). Hayashi et al. (1977) reported that the breeding season of B. japonicus is also affected by the age of the fish and differences in the age and size of the fish may cause the breeding period to vary somewhat. This notion should be further investigated. In the future, more studies on the reproductive characteristics of B. japonicus based on age and standard length should be performed.

4.3 Fecundity and Spawning PatternThe fecundity of fish can determine the recruitment of juvenile fish and affect the resource status of this species in the next few years. Fecundity can be used as an important index to evaluate the differences between the same population in different years and different geographical locations (Blom and Kennedy, 2016). In this study, the absolute fecundity of B. japonicus ranged from 8795 to 137513 eggs per tail, with an average of 51441 ± 33232 eggs per tail. Compared with the results of Xia et al. (2005), the egg diameter of individuals in this study was smaller, the fecundity was greater, and the magnitude of fecundity varied greatly. Mollet et al. (2000) reported that under high fishing pressure, fish exhibit changes in biological characteristics, such as increased fecundity and reduced egg diameter to maintain population reproduction. In addition to being affected by genetic and environmental factors, fecundity is also closely related to other indicators, such as age that affects the individual fecundity of fish and the starting time of the reproductive period (Bergstad et al., 2021). In the follow-up studies, indicators in addition to the sea conditions can provide more rigorous and reliable experimental results.

For the spawning pattern of B. japonicus, Fig.8 shows that there was only one peak in the monthly egg diameter distribution of B.japonicus, and the GSI also showed a single peak, with the highest value observed in August. Therefore, it was preliminarily hypothesized that the spawning pattern of B. japonicus in the East China Sea occurred once a year.

However, it is well known that mature eggs in the gonads are still likely to be absorbed (Xie et al., 1996), and it is soccasionally difficult to achieve ideal results by observing the frequency of egg diameter distribution. In future research, we will observe additional gonadal tissue sections of B. japonicus, and pay attention to the collection of mature gonadal samples. In addition, the study will reflect the relationship between fecundity and standard length and body weight more comprehensively from the statistical point of view, so as to make a more in-depth study on the biological reproductive characteristics of B. japonicus.

4.4 Length at First Sexual MaturityIn this study, the minimum observed sexually mature standard length of B. japonicus in the East China Sea was 180 mm, corresponding to a body weight of 113.6 g. The logistic equation regression showed that 50% of B. japonicus individuals had a standard length of 210.0 mm at sexual maturity. Compared with Yamashita's L50 = 253 mm (Yamashita et al., 2011), the values obtained in this study were smaller. Saraux et al. (2019) noted that in the face of strong pressure, a lack of prey organisms or intense competition, many marine fishes experience physiological and morphological trait changes, such as sexual maturity advancement and individual miniaturization. Age at sexual maturity and standard length are important characteristics for promoting the adaptation of fishes to the changes in the external environment. Comparing the research results of other biological characteristics in this paper with those in previous studies, B. japonicus had the characteristics of high fecundity, small egg diameter, and decreased L50 (Table 4). It is hypothesized that B. japonicus in the East China Sea may face strong fishing pressure, forcing it to maintain the stability of the original population through new reproductive strategies such as early sexual maturity and improved fecundity. It should be noted that one limitation of this study is the small number of mature ovary samples, and more mature gonadal samples should be collected in future spawning seasons.

|

|

Table 4 Comparison of the biological characteristics of B. japonicus from the East China Sea at different periods |

We conducted a preliminary study on the reproductive biology of B. japonicus in the East China Sea, assessing the relationships between body weight and standard length, sex ratio, length at first sexual maturity, spawning period, fecundity and spawning pattern. The results showed a power function relationship between body weight and standard length. The male-to-female ratio was close to 1:1, and the sex ratio exhibited significant differences among the different standard length groups. The fish spawned mainly in June-October, and the spawning pattern occured once a year. The length of the first sexual maturity of 50% of B. japonicus individuals can be employed as a basic index to establish the minimum biologically catchable standard.

AcknowledgementsThis study was funded by the Key Technology and System Exploration of Quota Fishing, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Fishery Management Fund Project (No. 36, 2017), and the Zhejiang Fishery Resources Survey Special Project (No. HYS-CZ-202314).

Author Contributions

Wendan Xuan: methodology, formal analysis and original draft preparation. Wenbin Zhu: paper review and editing, visualization, supervision and project administration. Haobo Zhang, Tian Wu, and Yixiang Zhao: software analysis. Kai Zhu and Pengfei Li, review and edit paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data and references presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The samples of Branchiostegus japonicus collected in the course of the experiments were obtained from fishing vessels, and the samples were already dead when they were transported to the laboratory in chilled form. The experimental protocol did not violate the requirements of relevant laboratory animal welfare and ethics, and complied with the experimental regulations.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Bergstad, O. A., Hunter, R. H., Cousins, N. J., Bailey, D. M., and Jorgensen, T. H., 2021. Notes on age determination, size and age structure, longevity and growth of co-occurring macrourid fishes. Journal of Fish Biology, 99(3): 1032-1043. DOI:10.1111/jfb.14801 (  0) 0) |

Blom, M., and Kennedy, J., 2016. Spatial variation in fecundity of Norwegian coastal cod, Gadus morhua (Linnaeus), along the coast of Norway. Fisheries Research, 183: 401-403. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2016.05.023 (  0) 0) |

Bo, Z. L., Zhou, W. X., Xue, L. J., and Chen, W. P., 2005. Survey on Branchiostegus resourece in the north part of the East China Sea and in the southern part of Yellow Sea. Journal of Fisheries of China, 29 (5): 676-681, DOI: CNKI:SUN:SCKX.0.2005-05-015 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Cheng, J. Y., and Zhang, X. J., 2010. Review of biology and fishery of major anglerfish. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 17 (1): 161-167, DOI: CNKI:SUN:ZSCK.0.2010-01-020 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Flores, A., Wiff, R., and Eduardo, D., 2015. Using the gonadosomatic index to estimate the maturity ogive: Application to Chilean hake (Merluccius gayi gayi). Journal of Marine Science, 72(2): 508-514. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsu155 (  0) 0) |

Flores, A., Wiff, R., Ganias, K., and Marshall, C. T., 2019. Accuracy of gonadosomatic index in maturity classification and estimation of maturity ogive. Fisheries Research, 210: 50-62. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2018.10.009 (  0) 0) |

Gong, Y. Y., Chen, Z. Z., Zhang, J., and Jiang, Y. E., 2015. Feeding habits of Diaphus chrysorhynchus from continental slope region in northern South China Sea in autumn. South China Fisheries Science, 11(5): 90-99 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.2095-0780.2015.05.011 (  0) 0) |

Han, Z. Q., Xu, H. X., Shui, B. N., Zhou, Y. D., and Gao, T. X., 2015. Lack of genetic structure in endangered large yellow croaker Larimichthys crocea from China inferred from mitochondrial control region sequence data. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 61: 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.bse.2015.04.025 (  0) 0) |

Hayashi, Y., 1977. Studies on the maturity and the spawning of the red tilefish in the East China Sea – Ⅰ Estimation of the spawning season from the monthly changes of gonad index. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi, 43: 1273-1277. DOI:10.2331/suisan.43.1273 (  0) 0) |

Ichikawa, H., and Beardsley, R. C., 2002. The current system in the Yellow and East China Seas. Journal of Oceanography, 58(1): 77-92. DOI:10.1023/A:1015876701363 (  0) 0) |

Iseki, T., Yagi, Y., Uehara, S., Kajihara, N., and Fujii, T., 2022. Age and growth of red tilefish Branchiostegus japonicus in two fishery grounds off the Kaetsu region, Niigata Prefecture, northern Sea of Japan. Fisheries Science, 88(6): 667-676. DOI:10.1007/s12562-022-01629-7 (  0) 0) |

John, W., and Cassandra, P., 2023. Life history of the endemic Hawaiian hogfish Bodianus albotaeniatus: Age, growth, and reproduction. Journal of Fish Biology, 103(2): 443-447. DOI:10.1111/jfb.15428 (  0) 0) |

Kobayashi, T., Ishibashi, R., Yamamoto, S., Otani, S., Ueno, K., and Murata, O., 2011. Gonadal morphogenesis and sex differentiation in cultured chub mackerel, Scomber japonicas. Aquaculture Research, 42(2): 230-239. DOI:10.1111/J.1365-2109.2010.02616.X (  0) 0) |

Lin, J., Li, Z. G., Wan, R., and Huang, C. W., 2022. Fecundity characteristics of spawning stocks of Coilia mystus in Yangtze Estuary. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University, 31(5): 1023-1031 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.12024/jsou.20220403830 (  0) 0) |

Mollet, H. F., Cliff, G., Pratt, H. L., and Stevens, J. D., 2000. Reproductive biology of the female shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus Rafinesque, 1810, with comments on the embryonic development of lamnoids. Fishery Bulletin, 98(2): 299-318. DOI:10.1046/j.1444-2906.2000.00066.x (  0) 0) |

Mu, X. X., Zhang, C., Zhang, C. L., Xu, B. D., Xue, Y., Tian, Y. J., et al., 2018. The fisheries biology of the spawning stock of Scomberomorus niphonius in the Bohai and Yellow Seas. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 25(6): 1308-1316 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1118.2018.17346 (  0) 0) |

Nitzan, T., Slosman, T., Gutkovich, D., Weller, J. I., Hulata, G., Zak, T., et al., 2016. Maternal effects in the inheritance of cold tolerance in blue tilapia (Oreochromis aureus). Environmental Biology of Fishes, 99(12): 975-981. DOI:10.1007/s10641-016-0539-0 (  0) 0) |

Russo, C., Drewery, M., Chang, C. T., Savage, M., Sanchez, L., Varga, Z., et al., 2022. Assessment of various standard fish diets on growth and fecundity of platyfish (Xiphophorus maculatus) and medaka (Oryzias latipes). Zebrafish, 19(5): 181-189. DOI:10.1089/zeb.2022.0004 (  0) 0) |

Saraux, C., Beveren, E. V., Brosset, P., Queiros, Q., Bourdeix, J., Dutto, G., et al., 2018. Small pelagic fish dynamics: A review of mechanisms in the Gulf of Lions. Deep-Sea Research Part II – Topical Studies in Oceanography, 159: 52-61. DOI:10.1016/J.DSR2.2018.02.010 (  0) 0) |

Taek, J. Y., Min, Y. C., Hye, Y. K., and Hwa, J. C., 2008. Age and growth of the red tilefish, Branchiostegus japonicus in the northern East China Sea. Journal of Environmental Biology, 29(4): 437-441. DOI:10.2112/06-0665.1 (  0) 0) |

Velde, T. V., Griffiths, S. P., and Fry, G. C., 2009. Reproductive biology of the commercially and recreationally important cobia Rachycentron canadum in northeastern Australia. Fisheries Science, 76(1): 33-43. DOI:10.1007/s12562-009-0177-y (  0) 0) |

Wang, K. L., Chen, Z. Z., Xu, Y. W., Sun, M. S., Wang, H. H., Cai, Y. C., et al., 2021. Biological characteristics of Decapterus maruadsi in the northern South China Sea. Marine Fisheries, 43(1): 12-21 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.13233/j.cnki.mar.fish.2021.01.002 (  0) 0) |

Xia, L. J., Shi, Z. H., Wang, J. G., Lu, J. X., and Zhao, R. X., 2005. The present situation of biology and aquaculture of Branchiostegus japonicus. Fishery Modernization, 4: 25-26 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-9580.2005.04.010 (  0) 0) |

Xie, X. J., He, X. F., and Long, T. C., 1996. Reproductive biology of Silurus meridionalis: Time, environmental conditions and behaviour of spawning. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 20: 17-24 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.1007/BF02951625 (  0) 0) |

Xu, G. Q., Chen, F., Zhang, H. L., Li, P. F., and Zhu, W. B., 2018. Selectivity of three kinds of gillnets for Branchiostegus japonicus in East China Sea. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 48(8): 34-42 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.20170297 (  0) 0) |

Xu, G. Q., Zhu, W. B., Zhou, Y. D., and Xu, L. X., 2021. Longline hook selectivity for Branchiostegus japonicus (Houttuyn, 1782) and Dentex tumifrons (Temminck & Schlegel, 1843) in the East China Sea. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 21(8): 401-413. DOI:10.4194/1303-2712-v21804 (  0) 0) |

Xu, H. X., Liu, Z. F., and Zhou, Y. D., 2003. Variation of Trichiurus haumela productivity and recruitment in the East China Sea. Journal of Fisheries of China, 4(4): 322-327 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0615.2003.04.006 (  0) 0) |

Yagi, M., Yamada, M., Shimoda, M., Uchida, J., Kinoshita, T., Shimizu, K., et al., 2014. Length-weight relationships of 22 fish species from the East China Sea. Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 31(1): 252-254. DOI:10.1111/jai.12648 (  0) 0) |

Yamashita, H., 2007. Geographical difference in body length composition of red tilefish Branchiostegus japonicus in the East China Sea. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi, 73(6): 1074-1080. DOI:10.2331/suisan.73.1074 (  0) 0) |

Yamashita, H., Sakai, T., Katayama, S., and Tokai, T., 2011. Reexamination of growth and maturation of red tilefish Branchiostegus japonicus in the East China Sea. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi, 77: 188-198. DOI:10.2331/SUISAN.77.188 (  0) 0) |

Yamashita, H., Shiode, D., and Tokai, T., 2009. Longline hook selectivity for red tilefish Branchiostegus japonicus in the East China Sea. Fisheries Science, 75(4): 863-874. DOI:10.1007/s12562-009-0115-z (  0) 0) |

Yin, M. C., 1995. Fish Ecology. China Agriculture Press, Beijing, 293pp (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Yu, W. J., Shen, J. Z., Gong, J., Li, Q., Li, C. S., Wang, K. X., et al., 2018. Reproductive biology of Hemiculter bleekeri in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Freshwater Fisheries, 48(3): 53-60 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.13721/j.cnki.dsyy.2018.03.008 (  0) 0) |

Zeng, X., Tanaka, K. M., Mazur, M. D., Wang, K., Chen, Y., and Zhang, S., 2020. Effects of habitat on reef fishes biodiversity and composition in rocky reefs. Aquatic Biology, 29: 137-148. DOI:10.3354/ab00731 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, C. I., Seo, Y. I., Kang, H. J., and Lim, J. H., 2019. Exploitable carrying capacity and potential biomass yield of sectors in the East China Sea, Yellow Sea, and East Sea/Sea of Japan large marine ecosystems. Deep-Sea Research Part II – Topical Studies in Oceanography, 163: 16-28. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2018.11.016 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, K., Zhang, J., Xu, Y. W., Sun, M. S., Chen, Z. Z., and Yuan, M., 2018. Application of a catch-based method for stock assessment of three important fisheries in the East China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 37(2): 102-109. DOI:10.1007/s13131-018-1173-9 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, H. L., Yan, L. P., Zhang, H., and Li, J. S., 2022. Age and growth characteristics of chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus) reproductive stock in the central East China Sea. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 29(4): 608-617 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.12264/JFSC2021-0364 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, Y. D., Zhang, C. L., and Cheng, Q. T.,, 1963. Fishes of East China Sea. China Science Press, Beijing, 241-243.

(  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24