2) College of Meteorology and Oceanography, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha 410073, China

Intraseasonal oscillation or low-frequency oscillation (ISO) pertain to periodic changes in atmospheric circulation or meteorological elements with time scales ranging from 10 d to a season. ISO presents an obvious seasonal difference, and in the Northern Hemisphere summer, this intraseasonal oscillation is called 'BSISO' (Wang and Xie, 1997). Unlike the typical Madden-Julian oscillation (MJO), which mainly propagates from west to the east along the equator, activities of the BSISO are more active in the northern Indian Ocean, the South China Sea and the northwest Pacific Ocean with northward extensions (Wang and Xie, 1997; Annamalai and Slingo, 2001; Lawrence and Webster, 2002; Lee et al., 2013). The air-sea interaction process associated with BSISO convection has been the focus of research for many years. The dynamic and thermal effects of BSISO on the ocean are significant, which can lead to intraseasonal frequency changes in sea surface temperature (SST), sea surface height (SSH), evaporation rate, and deep ocean temperature (Ye and Wu, 2015; Wang et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2020). In addition, many studies have shown that BSISO also has an important influence on El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events, the Asian monsoon system (especially the South Asia monsoon and the SCS monsoon), and precipitation in peripheral areas (Kessler and Kleeman, 2000; Roxy and Tanimoto, 2012; Chen et al., 2020).

Although it is indisputable that strong air-sea interactions have been observed along the propagation of the MJO and BSISO, most studies have focused on the intraseasonal variation above the sea surface, such as winds, SST, evaporation and other phenomena (Hsu and Weng, 2000; Webber et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2018). However, few studies have concentrated on the effects of ISO on marine variables in subsurface and deeper ocean waters. The development of remote sensing technology notably improved the ease of obtaining data above the sea surface, such as global SST and SSH, while deep ocean observations have remained scarce. For example, a significant limitation of ARGO floats is their poor spatiotemporal resolution and regional variability. Also, the reliability and accuracy of model output data still needs improvement. In addition, the thermodynamic and dynamic mechanisms in deep oceans at different scales are complex, leaving many fundamental principles still unsolved.

Previous studies on the response of deep ocean temperature to ISO are concentrated primarily around the equatorial Indian Ocean in winter, which is the most active area of the MJO. For example, Matthews et al.(2007, 2010) showed that surface wind stress anomalies associated with the MJO can force eastward-propagating oceanic equatorial Kelvin waves that extend downward to 1500 m. Beyond that, the intraseasonal amplitude of deep ocean anomalies are nearly six times that of the observed annual cycle. However, thus far, there have been few studies of these phenomena in the Western Pacific Ocean. The influence of BSISO-related convection on subsurface and deep ocean waters over the SCS is worth further study because BSISO activity appears to be a factor in one of the most active regions of the East Asian monsoon.

2 Data and Methods 2.1 DataThe temperature and salinity of the entire SCS are obtained from the HYbrid Coordinate Ocean Model (HYCOM; https://www.hycom.org/hycom/). HYCOM is a collaboration between the University of Miami modeling group and the Naval Research Lab, and the output data integrate multiple observations, such as satellite altimeter data, and data from expendable bathy thermographs (XBT), conductivity-temperature-depth devices (CTD), and ARGO floats. The horizontal resolution of daily HYCOM data is 1/12˚ × 1/12˚, while the vertical resolution ranges from the surface to 5000 m on the bottom, with a total of 40 layers (Chassignet et al., 2007). In this paper, 21 years (1996 – 2016) of model data were selected for analysis.

Existing meteorological and oceanographic reanalysis data contain outgoing longwave radiation (OLR), SST, and air-sea flux grid data. The daily OLR and SST are both from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data (NOAA; https://www.noaa.gov/). These databases mainly contain Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) infrared (IR) satellite data, in which the OLR is interpolated on 1˚ × 1˚ and SST on 0.25˚ × 0.25˚ resolution (Reynolds et al., 2007). We also used a third version of global sea surface flux products developed by the Objectively Analyzed air-sea Heat Fluxes (OAFlux) project at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) (http://www.uop.whoi.edu/). The products of OAFlux are the sum of surface meteorological variables, including shortwave (SWF) and longwave (LWF) radiative fluxes, ocean evaporation, heat fluxes, and other factors collected on a daily and 1˚ × 1˚ basis (Yu et al., 2008).

To confirm whether HYCOM can reproduce the signals influenced by BSISO, we conducted a comparison of multiple datasets. We compared the data using Optimum Interpolation SST (OISST) from NOAA. By comparison to recent years, BSISO was active in 2009. Thus, we selected the dataset from the summer half of 2009 for comparison. Figure one shows the comparison of SST anomalies in the southern SCS (10˚ – 15˚N, 110˚ – 115˚E) over this time period. As shown in Fig. 1, the periodic changes and trends of SST anomalies are basically the same, but the range of HYCOM variations was less than that of OISST, which has been a common problem with data from these models (Duvel and Vialard, 2007). Therefore, because of its lower variability, our study used HYCOM data as most suitable for analyzing ISO activities in the SCS.

|

Fig. 1 The evolution of area-averaged SST anomalies derived from HYCOM (blue line) and OISST (red line) during the summer half-year of 2009. |

The mixed layer is the near-surface layer of the ocean formed by solar radiation, precipitation, wind force, and other factors. The temperature, salinity, and density of the ocean mixed layer are nearly uniform on a vertical scale. The mixed layer is comprised of surface waters that are directly associated with the atmosphere. The energy, momentum, and material exchange between the ocean and atmosphere occur through the mixed layer, so it plays an important role in the study of air-sea interactions (Lukas and Lindstrom, 1991; Anderson et al., 1996). There are multiple ways to calculate the mixed layer depth, but they are generally divided into two categories: 'difference methodology' and 'gradient methodology' (An et al., 2012). This study include areas of the SCS where monsoon precipitation is frequent and abundant during summer. However, when wind stress and vertical mixing are weak along with abundant precipitation a phenomenon often occurs in which a 'shallow mixing layer' with a larger density gradient develops in the surface waters. To avoid this, we use the average temperature and salinity of 0 – 10 m to replace the value of the sea surface. We calculated a density value from the averaged surface salinity and temperature, which is 0.5℃ lower than the averaged surface temperature. The depth of this density defines the bottom of the mixed layer, which is the mixed layer depth (Wu et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2007).

2.3 Upper Ocean Temperature EquationA useful approach to study intraseasonal variations in seawater temperature is to consider the heat balance in the upper ocean layer. As discussed by Stevenson and Niiler (1983), the equation governing the upper ocean temperature T, which results from the heat and mass conservation equation, as:

| $ \frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial t}} + \vec V \cdot \nabla T + \omega \frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial z}} = \frac{1}{{\rho {C_p}}}\frac{{\partial Q}}{{\partial z}} + \frac{\partial }{{\partial z}}\left({K\frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial z}}} \right), $ | (1) |

where Q denotes the net surface heat flux, ρ and Cp represent the reference density and specific heat of seawater, respectively,

By integrating Z of Eq. (1) from the sea surface to a depth of an isotherm, we obtained an equation for estimating the upper ocean temperature above −h depth:

| $ \frac{{\partial \bar T}}{{\partial t}} = \frac{{{Q_0} - {Q_{ - h}}}}{{\rho {C_p}h}} - \vec V \cdot \nabla \bar T - \nabla \cdot \left({\int\limits_{ - h}^0 {\vec V'T'{\text{d}}z} } \right) - \frac{{\bar T - {T_{ - h}}}}{h}{\omega _e}, $ | (2) |

where

| $ {\omega _e} = \frac{{\partial h}}{{\partial t}} + {\vec V_{ - h}} \cdot \nabla h + {\omega _{ - h}}, $ |

and

| $ {Q_{ - h}} = {Q_0}(0.58{e^{ - h/0.35}} + 0.42{e^{ - h/23}}) . $ | (3) |

Therefore, Eq. (2) is the upper ocean temperature equation above −h depth. The left side of the equation represents an average temperature change, the first term on right is the thermal forcing, the second and third terms are the horizontal temperature advection, and the last term is vertical entrainment. Based on the data for temperature, salinity, current velocity of HYCOM, and the air-sea flux of QAFlux, we can determine the contribution of each element in this equation.

2.4 BSISO AnalysisMany studies have demonstrated that BSISO activities have two significant frequencies of intraseasonal oscillation, one of approximately 10 – 25 d and another of 30 – 60 d (Jiang et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2013). Usually, the intensity of 30 – 60 d activities is stronger than the former, so we chose the 30 – 60 d period for our study. Figs. 2a – c shows 30 – 60 d bandpass-filtered OLR anomalies based on empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis, which represents the different BSISO convection phases in the SCS area. These three EOF modes explain two-thirds of the total variance (EOF1, 30.3%; EOF2, 18.8%; EOF3, 9.9%). They show that BSISO-related convection spread to the equatorial western Pacific, strengthens at approximately 15˚N, and dissipates over subtropical mainland China. The time series of three principal components has obvious sinusoidal characteristics (Fig. 2d), which suggest that the lifecycle of the 30 – 60 d band passed ISO in the SCS is approximately 40 d.

|

Fig. 2 Three leading EOF modes: (a) EOF1, (b) EOF2 and (c) EOF3 of 30 – 60-day bandpass filtered daily OLR anomalies over the SCS for 1996 – 2016; (d) is the time series of three EOF models (EOF1 is black line, EOF2 is blue line, EOF3 is red line). This figure is quoted from Jia et al. (2020). |

By using 21 years (1996 – 2016) of daily anomaly OLR and MLD (based on HYCOM data) to compute the ratio of 10 – 90 d bandpass variance to unfiltered variance, we obtained a geographical distribution of BSISO-related variance (Figs. 3a – b). Fig. 3a shows that ISO convective activities in boreal summer are most active in the equatorial Indian Ocean followed by the South China Sea and the Northwest Pacific Ocean. The variance of MLD corresponds to the OLR, with the maximum occurring over the SCS. There are two centers of MLD variance in this region; one is located in the south-central part of the SCS (6˚ – 12˚N), and the other is in the northern SCS (16˚ – 22˚N). Whereas it is much weaker in equatorial Indian.

|

Fig. 3 Variance in the BSISO-related anomalies of the (a) OLR and (b) MLD in summer (May – October). Power spectra of BSISO-related anomalies of the (c) OLR and (d) MLD over the SCS in summer. The red curve represents the red-noise spectrum. The lower and upper blue dashed curves are the 5% and 95% red-noise significance levels, respectively. |

Moreover, the power spectra analysis of OLR anomalies over the SCS (Fig. 3c) concentrates in two intraseasonal periods, like the BSISO cycle, as are the power spectra of the MLD (Fig. 3d). Therefore, our data confirm that the MLD of the SCS in summer has obvious ISO characteristics. As mentioned above, BSISO convection can influence the physical factors of the air-sea interface, such as wind, waves, precipitation, sunlight, and other factors. MLD is susceptible to such meteorological conditions, so it seems possible to prove that BSISO activities may influence MLD in the SCS area.

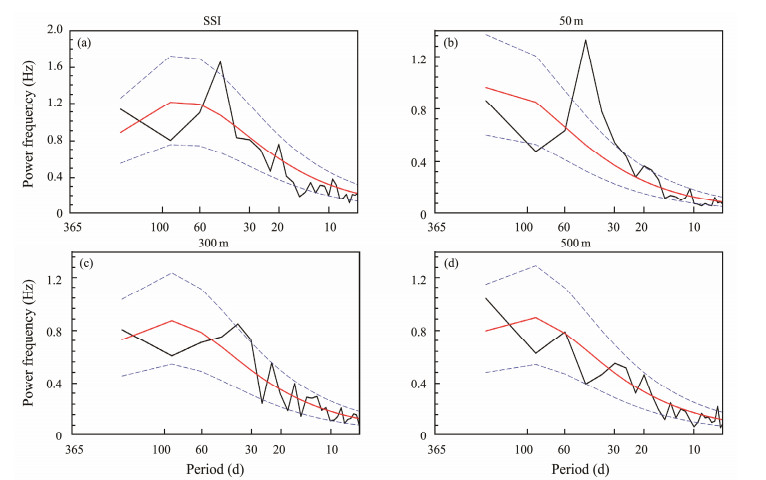

3.2 ISO of Upper Ocean TemperatureThere have been many studies on the ISO of SST. However, a remaining question concerns whether the temperature below the sea surface also has such oscillation features. Based on HYCOM data, we further analyzed the temperature at the sea surface, 50 m, 300 m and 500 m in the SCS by power spectra. The power spectra analysis of SST anomalies over the SCS (Fig. 4a) is concentrated in two intraseasonal periods (20 and 50 days), as is the lifecycle of the BSISO activities. However, at deeper depths, the oscillation period is in the range of 30 – 60 d and the signal of the 10 – 20 d oscillation is very weak (Figs. 4b – d). This is because the SST is affected by the radiation flux, but the deep ocean is primarily affected by dynamic processes such as horizontal flow and entrainment velocity. When the depth is greater than 50 m, the power frequency of temperature also decreases rapidly, indicating that the ISO characteristics of seawater gradually weaken with increasing depth. However, when the depth exceeds 500 m, there remains no obvious signal of intraseasonal oscillation. This result differs from previous studies on the effect of the MJO on the Indian Ocean in winter, which suggests that the Kelvin waves forced by the MJO can extend downward to 1500 m. This may be because the MJO convective activities in the equatorial Indian Ocean are much stronger in winter, or terrain of the SCS limits propagation of Kelvin waves.

|

Fig. 4 As shown in Figs. 3c – d but here for the (a) sea surface, (b) 50 m, (c) 300 m and (d) 500 m seawater temperatures over the SCS in summer. |

To explore the spatiotemporal variation of BSISO-related convection and MLD for periods of 30 – 60 d, we used composite analysis of strong ISO events (i.e., outliers exceeding standard deviation) according to the principal components of EOF analysis in Section 2.4 above (Roxy et al., 2013). In each oscillation event, Day zero refers to the number of days in which the most active convection occurs (i.e., the maximum negative OLR anomalies), and the numbers before or after Day zero are marked as positive or negative days. By the composite analysis with time series in Section 2.4, a strong ISO event can be considered to be a 40-day cycle with respect to Day zero, which is roughly in line with the average period of the BSISO. Fig. 5 shows the composite 30 – 60 d anomalies of OLR and 1000 hPa wind during different phases of BSISO over the SCS, which are based on the selected BSISO events from 1996 to 2016. We divided the northward propagation from the equator to subtropical East Asia into nine phases (concentrated on days −20, −15, −10, −5, 0, +5, +10, +15 and +20).

|

Fig. 5 Composites of BSISO-related OLR anomalies (shaded) and 1000 hPa horizontal wind anomalies (vector) centered at days −20, −15, −10, −5, 0, +5, +10, +15 and +20 in terms of BSISO active events. Day 0 indicates the day on which deep convection of BSISO reaches a maximum over the SCS, and positive (negative) days indicate the days after (before). |

Fig. 6 shows the composited MLD and SST anomalies based on the BSISO index, which exhibits a significant northward propagation related to each BSISO phase in Fig. 5. On Day zero, when convection is active, the MLD in the central and southern parts of the SCS is a positive anomaly, while it is negative only in the northern coastal region. As the BSISO-related convection propagates northward, positive MLD anomalies also gradually propagate to the northern part of the SCS in the same manner and show the strongest sign on day +5. The suppressed phase follows similar rules with opposite features to the MLD. In terms of spatial and temporal distribution, the positive MLD anomalies lag behind the 1/8 lifecycle (by approximately 5 d) of the BSISO active convection but are 1/8 cycles ahead of the cold SST. In previous studies, it has been shown that the SST anomalies lag behind approximately 10 days of the BSISO (Wang et al., 2018). In conclusion, the suppressed (enhanced) MLD followed a lagging change rule with negative (positive) BSISO convection during summer in the SCS. Next, we will analyze the reasons.

|

Fig. 6 As in Fig. 5 but for MLD anomalies (shaded) and SST anomalies (contour) related to each phase of BSISO active events. |

On an intraseasonal time scale, the variation in MLD is influenced by sea surface dynamic factors (such as wind and currents) and thermal factors (solar radiation, evaporation, etc.), which results in an intensity change in turbulent mixing (Qiu, 2002; Huang et al., 2010; Girishkumar et al., 2013). On Day zero, the whole SCS is basically under the control of active convection and accompanied by enhanced southwestward wind speed and precipitation. Thus, the MLD disrupted and deepened in the process of wave mixing. Moreover, the enhanced wind speed leads to strong sea surface evaporation, and cumulus clouds accompanied by convective activities weaken the shortwave radiation received by the ocean. Both factors cause negative heat flux anomalies at the air-sea boundary and lead to a heat loss state of the upper ocean in the southern SCS. This is another reason for the deepening of the MLD.

As mentioned above, the variation in MLD lags behind the one-eighth lifecycle (approximately 5 d) of the BSISO phase. For example, on Day zero, the center of BSISO convection is located at 15˚N, while the center of MLD is five latitude degrees south of it. We now explore how the BSISO affects these factors. Figure seven shows the latitude-based lead-/lag-time diagram of the OLR, 10 m neutral wind speed and net heat flux anomalies along the section from 110˚E to 130˚E. The daily net heat flux (qnet, positive downward) results from combining the OAFlux latent and sensible heat fluxes with the ISCCP ocean surface radiation. The qnet is determined as:

| $ {\text{qnet}} = {\text{SWF}} \downarrow - {\text{ LWF}} \uparrow - {\text{ LHF}} \uparrow - {\text{ SHF}} \uparrow, $ | (3) |

where SWF↓ is net shortwave radiation flux, LWF↑ is net longwave radiation flux, LHF↑ is latent heat flux and SHF↑ is sensible heat flux. Among them, shortwave radiation is the main source of qnet over the sea surface, and its magnitude is far greater than the others.

Several features are visible in Figure seven. First, intraseasonal oscillations of qnet and wind speed propagate northward over the SCS, as well as OLR anomalies. Second, the position of qnet is almost coincident with OLR anomalies, while the wind speed obviously lags by approximately 5 days, and the extreme value is also 2 latitude degrees to the south. The results show that the wind field of the sea surface is very consistent with the intraseasonal variation in MLD. The distribution of the sea surface wind requires further analysis in two ways. The West Northern Pacific (WNP) summer monsoon trough is cyclonic, which is an important precursor of low-frequency convective activities. In addition to cyclonic vorticity, the southwest airflow is equally important for the lower troposphere of the monsoon trough. As shown in Figure five, the center of cyclonic circulation accompanied by the BSISO sets in the northwest location of convective activities (OLR anomalies). Under such a configuration, the maximum sea surface wind speed should be located to the south of a convection center, that is, the area where the wind anomalies coincide with the southwest airflow. This explains why both the maximums of MLD and 10 m wind speed occur on day +5, not Day zero. In addition, this observation indirectly suggests that wind stress is the main factor for the intraseasonal variability in MLD over the SCS.

|

Fig. 7 Latitude-based lead-/lag-time diagram of the composite raw pentad anomalies along the section of 110˚E to 130˚E for (a) OLR (shaded) and qnet (contour); (b) OLR (shaded) and 10 m neutral wind speed (contour). The lead-/lag-time in days with positive (negative) values indicates the number of days after (before) Day zero, equivalent to that shown in Fig. 5. |

Similar to the salient intraseasonal oscillation of MLD forced by the BSISO, upper ocean temperature also shows prominent variability on intraseasonal timescales over the SCS (Fig. 8). From the whole spatial and temporal distribution, the cold (warm) temperature anomalies from the surface to depth lag behind the positive (negative) phase of the BSISO convection, which is the same as the relationship between SST and MJO or BSISO activities in previous studies. However, significant differences remain between the sea surface and deep layer on different days, as well as in the southern and northern regions of the SCS. Taking the positive phase of BSISO as an example, the cold temperature signal is first excited at the depth of the thermocline on day −15 and then propagates northward. On day −10, the seawater temperature anomalies of the thermocline are opposite to the warm SST south of 12˚N. With the enhancement of BSISO convection, the SST and deep ocean temperature anomalies gradually show a consistent cold state and then expand to the northern part of the SCS. In the southern SCS, the seawater temperature anomalies of the thermocline are ahead of the SST and are almost synchronous with the BSISO phase. However, in the northern part of the SCS, such characteristics are not obvious. On the other hand, the BSISO-related seawater temperature anomalies in the southern SCS areas are stronger than those in the northern SCS areas. This is due to the more intense wind speed in the southern region, as does the SST. This is analyzed in the next section.

|

Fig. 8 As in Fig. 6 but for the cross section of ocean temperature anomalies (shaded) based on HYCOM data. Longitude is averaged over 110˚ – 120˚E. Dotted areas are statistically significant at the 99% confidence level based on a significant t test. Black dotted line is the MLD. |

Based on the upper ocean temperature equation, we calculated composite upper ocean temperature anomalies and the other items on the right side of Eq. (2). The three terms on the left (Ec, horizontal temperature advection; Eq, thermal forcing; Ew, vertical entrainment) is expressed as follows:

| $ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {Ec = \frac{{{Q_0} - {Q_{ - h}}}}{{\rho {C_p}h}}} \\ {Eq = - \vec V \cdot \nabla \bar T - \nabla \cdot \left({\int\limits_{ - h}^0 {\vec V'{\text{ }}T'{\text{d}}z} } \right)} \\ {Ew = - \frac{{\bar T - {T_{ - h}}}}{h}{\omega _e}} \end{array}} \right. . $ | (4) |

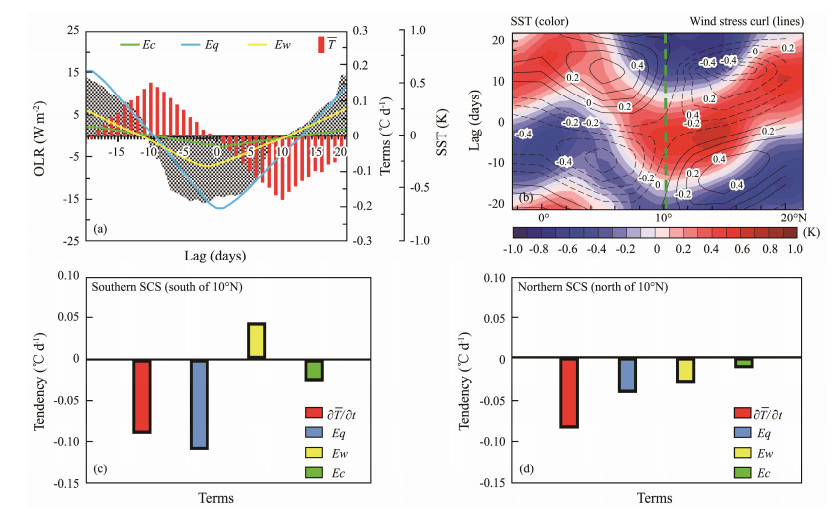

The averaged temperature anomalies

|

Fig. 9 (a) Temporal evolution of the composite terms of Eq. (2) in the SCS, for averaged seawater temperature ( |

However, the vertical entrainment term is a process of marine dynamics caused by sea surface wind stress. A negative wind stress curl can cause warm seawater to accumulate and sink through Ekman convergence, and a positive wind stress curl may cause the lift of cold seawater below the thermocline. The anomalous lift (descend) of the thermocline is closely associated with the westerly wind anomalies and intensification of the positive (negative) wind stress curl in the SCS. Take Day 0 to day +15 for instance; abnormal southwest winds prevail over the whole SCS and the wind stress curl south of 10˚N is negative, which makes warm water sink and the mixed layer deepen, then causing warm temperature anomalies of the thermocline. The SST of the SCS lags behind the BSISO convection and shows cold SST anomalies. Hence, it makes the SST anomalies contrary to the temperature of the thermocline in the southern SCS. However, the wind stress curl north of 10˚N is positive (cold water rise), which causes cold anomalies of the thermocline as well as the cold SST. The latitude-based lead-/lag-time diagram (Fig. 9b) clearly shows the north – south gap of the SCS. In the southern SCS, the positive (negative) wind stress curl overlaps the warm (cold) SST anomalies. While the situation reverses in the northern SCS. In addition, the SST anomalies usually lag behind the BSISO. Therefore, during the initial phase of the BSISO, the temperature anomalies of the thermocline change obviously opposite to the SST in the southern SCS but not in the northern SCS.

Figs. 9c – d shows the four terms of Eq. (2) in the southern (south of 10˚N) and northern (north of 10˚N) SCS from Day zero to day +10. In the initial stage of the BSISO, as the temperature gradually decreases, the contribution of the vertical entrainment term is opposite in the southern and northern areas. Obviously, it has a reverse effect on the cold sea temperature in the southern SCS, as mentioned above. However, the vertical entrainment term enhances the decrease in temperature in the northern part by increasing subsurface cold water.

5.3 Physical MechanismThe 30 – 60 d BSISO convective activities can affect the upper ocean by changing the surface heat flux and dynamic processes over the SCS. Active convection can reduce downward shortwave radiation and lead to cold SST anomalies, which reach a maximum approximately 10 d (1/4 lifecycle) later. Meanwhile, the weak wind speed and latent heat flux north of the convection tend to form warm SST anomalies. However, the dynamic processes related to wind stress are more complex. During the active phase of BSISO, a negative wind stress curl caused by abnormal southwest winds can lead to subsidence of warm water and deepening of the MLD in the southern SCS (south of 10˚N). Therefore, under the force of vertical entrainment, the SST anomalies are contrary to the temperature of the thermocline in the southern SCS. Furthermore, the wind stress curl is weaker, and the force of vertical entrainment is not apparent at the time in the northern area. Therefore, the water temperature becomes consistently warm in the northern upper ocean. As the BSISO convection weakens and moves northward, the SST of the southern SCS tends to warm. For negative BSISO convection, the opposite is true. The asymmetry of heat flux and wind stress on both sides of the BSISO convection is the main reason for the oscillations of the mixed layer and upper ocean temperature. As the BSISO propagates in the meridional direction from south to north, the deferred response of the air-sea interaction can also result in a difference in the space-time phase (Fig. 10).

|

Fig. 10 Schematic diagram showing the effect of BSISO on the MLD and upper ocean temperature over the SCS. The difference in the thermal and dynamic forcing processes at each BSISO phase is the main reason for the intraseasonal oscillation of the upper ocean. |

In addition, BSISO convection may also cause anomalies of currents and mesoscale eddies, especially in the central and southern SCS, which is known as 'intensified in the southern basin' (Zu et al., 2019). Based on satellite altimeter data, we find that during the active phase of the BSISO, the SCS western boundary current obviously strengthens due to the southwestern jet. In zones of increased western boundary currents, the MLD will decrease, and the ocean temperature will turn chilly. Moreover, the largest changes in MLD and SST anomalies occur in southern Vietnam and western Philippine Islands, which are the regions with strong eddy kinetic energy (EKE) in summer (figures omitted). These are also important reasons for the differences that occur between the northern and southern SCS. Due to limited space, we can just talk briefly in this paper and suggest that these phenomena deserve further investigation.

6 ConclusionsBased on multiple reanalysis and observational data we used upper ocean layer balance equations to identify MLD and heat flux variations in the SCS in summer. We also analyzed fundamental processes and verified mechanisms by which the BSISO influences the MLD and upper ocean temperature as well as how they cause different anomalies of intraseasonal oscillation. The main conclusions of this study are summarized as follows:

1) The mixed layer in the SCS exhibits an intraseasonal oscillation of 30 – 60 d and shows a strong correlation between BSISO time-space distribution features. The MLD increases (decrease) during the positive (negative) phase of the BSISO. The evolution of the MLD usually lags behind the BSISO-related convection by approximately one-eighth lifecycle (5 d). Therefore, the center of positive (negative) MLD develops on the south side of the active (inactive) BSISO convection.

2) There are also significant intraseasonal oscillations of seawater temperature both on the surface and subsurface of the SCS. However, it is noteworthy that the variabilities in seawater temperature in different layers are not vertically consistent. Temperature near the thermocline changes ahead of SST. As a result, during the initial phase of the BSISO, the temperature anomalies of the thermocline clearly change opposite to the SST, especially in the southern SCS.

3) With the method of composite analysis and an upper ocean temperature equation, we verified physical mechanisms of how the BSISO affects MLD and upper ocean temperatures. Changes in heat flux and wind stress within the surface layer caused by BSISO-related convection are dominant factors. The vertical entrainment term mainly caused by BSISO-related wind stress can initiate vertical motion of seawater, which leads to temperature anomalies in deeper layers. The thermal forcing is sensitive to BSISO convection and usually synchronizes with OLR anomalies. It is an important source for the heat budget of the upper ocean. During the whole cycle of BSISO these two terms have a combined effect on the alternate temperature anomalies over the SCS.

7 DiscussionQuestions addressed in this study require further consideration. The first relates to the limitation of available data. Daily marine reanalysis data are scarce and the SCS lacks long-term anchorage buoy observations, such as the Research Moored Array for African-Asian-Australian Monsoon Analysis and Predictio (RAMA). Therefore, we used HYCOM reanalysis data in this research paper. Although many studies have confirmed the superiority of HYCOM data, the reliability of the conclusion still needs to be confirmed due to the lack of ability for multiple data comparisons.

In previous studies, there were many different definitions for MLD, while the two main categories were 'density gradient' and 'temperature difference'. Many papers have mentioned that the former is more accurate in most cases, as it both considers the factors of temperature and salinity. In addition to the methods used in this paper, other methods, such as '0.8℃ lower than the temperature of 10 m depth', are also evaluated. The experimental results show that the conclusion is similar. Furthermore, the 'temperature difference' can avoid the effect of 'freshwater skin', which is common in rainy summers.

With the analysis of features and formation mechanisms, we studied the effect of BSISO on mixed layer and upper ocean temperatures over the SCS, which provides an effective mechanism for air-sea interactions. Therefore, based on our analyses, we suggest that BSISO-related convection may also affect other marine factors, such as salinity, sea surface height (SSH), thermocline, and the barrier layer. It is worth investigating other related oceanic phenomena (marine organisms, marine acoustics) since we summarized the general rules of upper ocean ISO.

AcknowledgementThis study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41830964).

An, Y. Z., Zhang, R., Wang, H. Z., Chen-Jian, and Chen, Y. D., 2012. Study on calculation and spatio-temporal variations of global ocean mixed layer depth. Chinese Journal of Geophysics, 55(7): 2249-2258 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Anderson, S. P., Weller, R. A., and Lukas, R. B., 1996. Surface buoyancy forcing and the mixed layer of the western Pacific warm pool: observations and 1d model results. Journal of Climate, 9(12): 3056-3085. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(1996)009<3056:SBFATM>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Annamalai, H., and Slingo, J. M., 2001. Active/break cycles: Diagnosis of the intraseasonal variability of the Asian summer monsoon. Climate Dynamics, 18(1-2): 85-102. DOI:10.1007/s003820100161 (  0) 0) |

Chassignet, E. P., Hulburt, H. E., Smedstad, O. M., Halliwell, G. R., and Hogan, P. J., 2007. The HYCOM (hybrid coordinate ocean model) data assimilative system. Journal of Marine Systems, 65(1-4): 60-83. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2005.09.016 (  0) 0) |

Chen, X., Li, C., and Li, X., 2020. Influences of ENSO on boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation over the western Pacific in decaying summer. Climate Dynamics, 54(7-8): 3461-3473. DOI:10.1007/s00382-020-05183-9 (  0) 0) |

Duvel, J. P., and Vialard, J., 2007. Indo-Pacific sea surface temperature perturbations associated with intraseasonal oscillations of tropical convection. Journal of Climate, 20(13): 3056-3082. DOI:10.1175/JCLI4144.1 (  0) 0) |

Girishkumar, M. S., Ravichandran, M., and Mcphaden, M. J., 2013. Temperature inversions and their influence on the mixed layer heat budget during the winters of 2006 – 2007 and 2007 – 2008 in the Bay of Bengal. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 118(5): 2426-2437. DOI:10.1002/jgrc.20192 (  0) 0) |

Hsu, H. H., and Weng, C. H., 2000. Northwestward propagation of the intraseasonal oscillation in the western North Pacific during the boreal summer: Structure and mechanism. Journal of Climate, 14(18): 3834-3850. (  0) 0) |

Huang, B. Y., Xue, Y., Zhang, D. X., Kumar, A., and McPhaden, M. J., 2010. The NCEP GODAS ocean analysis of the Tropical Pacific mixed layer heat budget on seasonal to interannual time scales. Journal of Climate, 23(18): 4901-4925. DOI:10.1175/2010JCLI3373.1 (  0) 0) |

Jia, W. T., Zhang, W. M., Zhu, J. H., and Sun, J. L., 2020. The effect of boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation on evaporation duct and electromagnetic propagation over the South China Sea. Atmosphere, 11(12): 1298. DOI:10.3390/atmos11121298 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, X., Li, T., and Wang, B., 2004. Structures and mechanisms of the northward propagating boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation. Journal of Climate, 17(5): 1022-1039. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<1022:SAMOTN>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Kessler, W. S., and Kleeman, R., 2000. Rectification of the Madden-Julian oscillation into the ENSO cycle. Journal of Climate, 43(13): 3560-3575. (  0) 0) |

Lawrence, D. M., and Webster, P. J., 2002. The boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation: Relationship between northward and eastward movement of convection. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 59(9): 1593-1606. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(2002)059<1593:TBSIOR>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Lee, J. Y., Wang, B., Wheeler, M. C., Fu, X., Waliser, D. E., and Kang, I. S., 2013. Real-time multivariate indices for the boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation over the Asian summer monsoon region. Climate Dynamics, 40(1-2): 493-509. DOI:10.1007/s00382-012-1544-4 (  0) 0) |

Lukas, R., and Lindstrom, E., 1991. The mixed layer of the western equatorial Pacific Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research, 96(S01): 3343. DOI:10.1029/90JC01951 (  0) 0) |

Matthews, A. J., Singhruck, P., and Heywood, K. J., 2007. Deep ocean impact of a Madden-Julian Oscillation observed by Argo floats. Science, 318(5857): 1765-1769. DOI:10.1126/science.1147312 (  0) 0) |

Matthews, A. J., Singhruck, P., and Heywood, K. J., 2010. Ocean temperature and salinity components of the Madden-Julian oscillation observed by Argo floats. Climate Dynamics, 35(7-8): 1149-1168. DOI:10.1007/s00382-009-0631-7 (  0) 0) |

Paulson, E. A., 1977. Irradiance measurements in the upper ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 7(6): 952-956. DOI:10.1175/1520-0485(1977)007<0952:IMITUO>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Qiu, B., 2002. The Kuroshio extension system: Its large-scale variability and role in the midlatitude ocean-atmosphere interaction. Journal of Oceanography, 58(1): 57-75. DOI:10.1023/A:1015824717293 (  0) 0) |

Reynolds, R. W., Smith, T. M., Liu, C., Chelton, D. B., Casey, K. S., and Schlax, M. G., 2007. Daily high-resolution-blended analyses for sea surface temperature. Journal of Climate, 20(22): 5473-5496. DOI:10.1175/2007JCLI1824.1 (  0) 0) |

Roxy, M., and Tanimoto, Y., 2012. Influence of sea surface temperature on the intraseasonal variability of the South China Sea summer monsoon. Climate Dynamics, 39(5): 1209-1218. DOI:10.1007/s00382-011-1118-x (  0) 0) |

Roxy, M., Tanimoto, Y., Preethi, B., Terray, P., and Krishnan, R., 2013. Intraseasonal SST-precipitation relationship and its spatial variability over the tropical summer monsoon region. Climate Dynamics, 41(1): 45-61. DOI:10.1007/s00382-012-1547-1 (  0) 0) |

Stevenson, J. W., and Niiler, P. P., 1983. Upper ocean heat budget during the Hawaii-to-Tahiti shuttle experiment. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 13(10): 1894-1907. DOI:10.1175/1520-0485(1983)013<1894:UOHBDT>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Sun, C. X., Liu, Q. Y., and Jia, Y. L., 2007. Annual and interannual variations of the mixed layer in the South China Sea. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 37(2): 197-203 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Wang, B., and Xie, X., 1997. A model for the boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 54(1): 72-86. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(1997)054<0072:AMFTBS>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Wang, T., Yang, X. Q., Fang, J., Sun, X., and Ren, X., 2018. Role of air-sea interaction in the 30 – 60-day boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation over the western North Pacific. Journal of Climate, 31(4): 1653-1680. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-17-0109.1 (  0) 0) |

Webber, B. G., Matthews, A. J., and Heywood, K. J., 2010. A dynamical ocean feedback mechanism for the Madden-Julian oscillation. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society: A Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, Applied Meteorology and Physical Oceanography, 136(648): 740-754. (  0) 0) |

Wu, W., Tomczak, M., Fang, X., and Wu, D., 2001. The barrier layer in the southern region of the South China Sea. Chinese Science Bulletin, 46(16): 1388-1392. DOI:10.1007/BF03183396 (  0) 0) |

Ye, K., and Wu, R., 2015. Contrast of local air-sea relationships between 10 – 20-day and 30 – 60-day intraseasonal oscillations during May – September over the South China Sea and western North Pacific. Climate Dynamics, 45(11): 3441-3459. (  0) 0) |

Yu, L., Jin, X., and Weller, R. A., 2008. 2008: Multidecade global flux datasets from the Objectively Analyzed Air-Sea Fluxes (OAFlux) Project: Latent and sensible heat fluxes, ocean evaporation, and related surface meteorological variables. OAFlux Project Tecnology Report. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, OA-2008-1.

(  0) 0) |

Zu, T., Xue, H., Wang, D., Geng, B., Zeng, L., Liu, Q., et al., 2019. Interannual variation of the South China Sea circulation during winter: Intensified in the southern basin. Climate Dynamics, 52(3): 1917-1933. (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22