Human activities, including marine traffic, fishing, pollution and climate change, have severely threatened cetaceans, especially near shore (Davidson et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2022). There are several nearshore cetaceans including Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin and common bottlenose dolphins, inhabiting Chinese waters (IUCN, 2022). The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) has been designated as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species (Jefferson and Smith, 2016; Jefferson et al., 2017). It is the only Class I wildlife species in the family Delphinidae in the Catalogue of Aquatic Wildlife under Key State Protection. They are widely distributed in the Indo-Pacific region (the currently available estimate is 5692 individuals), and one of the important habitats is located in China with 4730 individuals accounting for about 83% of the known abundance in the world (IUCN, 2022). There are several resident populations of humpback dolphin in the China seas, including Northern Beibu Gulf (NBG), coastal waters of Southwestern Hainan (SH), coastal waters of Eastern Zhanjiang (EZ), Pearl River Estuary (PRE) and Xiamen Bay (XM) (Jefferson and Hung, 2004; Tang et al., 2021). Humpback dolphins have a long life-span of at least 38 years, but few females give birth to more than three calves in 14 years, suggesting a low reproductive output and/or low calf survival rate (Jefferson et al., 2012). Also, their habitat is close to areas with intensive anthropogenic impact. Their diet overlaps with that of coastal human populations (Ning et al., 2020), therefore they compete intensely with human beings for survival. The sound used by dolphins for social communication coincides with vessel noise well within their audible range (Sims et al., 2012). Current local threats to humpback dolphins across their fragmented range in China is likely underestimated (Huang and Karczmarski, 2014). The most recent study predicts that the Pearl River Estuary metapopulation, the largest recorded in the world, will decline by about 87% in three generations and has met the criteria of Critically Endangered (CR) according to IUCN Criterion (Chan, 2019). Thus, the species conservation and relevant environment management issues are of serious concern.

In coastal waters, marine traffic is of special concern because of the high flux density, the diversity of vessels, their noise levels and speed (Mattson et al., 2005; Richardson et al., 2013). Although the interactions vary with species, the particular population, study areas, vessel types and speeds (Nowacek et al., 2001; New et al., 2013; Senigaglia et al., 2016), most studies conclude that exposure to marine traffic has both short-term and long-term effects on nearshore cetaceans (Grech and Marsh 2008; McWhinnie et al., 2018). Changes in activity and socializing (Lundquist et al., 2012; Papale et al., 2012), fatal and non-fatal injuries (Kraus et al., 2005; Lundquist et al., 2012; Burgess et al., 2018), and a decline in population growth rates based on low recruitment rates, delayed sexual maturity and long-term energy depletion (Schoeman et al., 2020) are some of the consequences. In order to facilitate decision-making related to conservation, a comprehensive risk assessment of the affect of marine traffic on coastal dolphins is needed.

Marine traffic is a major threat to humpback dolphins (Li, 2020) because of the high degree of coastal development and increased shipping throughout their ranges. Injuries and fatal blunt trauma have been reported in Chinese waters (Parsons and Jefferson 2000; Jefferson et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018; Chan and Karczmarski, 2019). Karczmarski et al. (1997) and Marcotte et al. (2015) report that increased boat activity increases length of dives and harmful noise (Sims et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017).

The semiquantitative spatial vulnerability approach is an improved risk assessment tool based on the abundant history of risk and vulnerability (Turner et al., 2003; Davidson et al., 2012; Hodgson et al., 2016). This approach identifies conflict areas that focus on combined animal and human activities and directly assesses the risk and vulnerability. Exposure risk is analyzed based on the overlap between the distribution of the animals and the threats to them. Then several aspects of their sensitivity to threats are evaluated, and finally the vulnerability to certain threats is assessed. Analogous research has been successfully applied to polar bears, blue whales, humpback whales and narwhals (Laidre et al., 2008; Maxwell et al., 2013; Hauser et al., 2018). However, it is rare to use this method to assess the risks of marine traffic on nearshore cetaceans, including humpback dolphins.

Detailed research, synthesizing the spatial and demographic characteristics of humpback dolphins in Chinese waters, combined with the definition and availability of sea routes, an explicit risk assessment framework using the semiquantitative spatial vulnerability approach has been used to evaluate the vulnerability of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins to marine traffic in the main habitats of China. An additional six years of field data have also been included. This study could strengthen Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin conservation policy decisions, and might be applicable to other coastal dolphins.

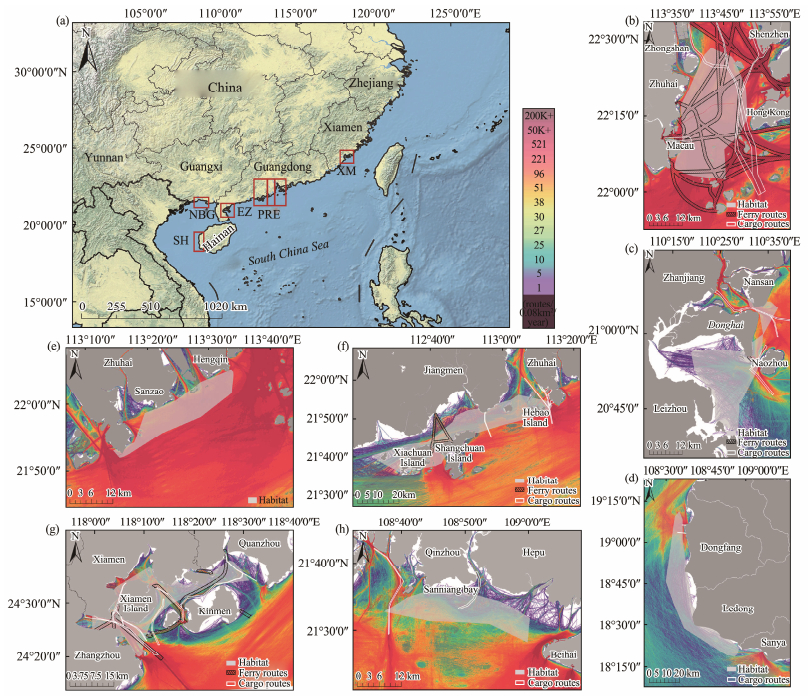

2 Methods 2.1 Study AreaThe five Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin populations selected for this study include Xiamen Bay (XM), Pearl River Estuary (PRE), coastal waters of Eastern Zhanjiang (EZ), Northern Beibu Gulf (NBG), and the coastal waters of Southwestern Hainan (SH). A recent photo-identification study in EZ showed that the distribution range of particular dolphin individuals includes both Zhanjiang Bay and Leizhou Bay waters and should be considered as one population (Xu et al., 2015). Also, multiple quantitative measures indicate that the dolphins in PRE represent three socially distinct and spatially discrete units: Eastern, Middle, and Western PRE subpopulations (EPRE, MPRE, and WPRE, respectively) (Chan, 2019). We have divided the PRE into these three independent units. A cross-matched analysis of photographic catalogs of individual dolphins collected in the PRE, EZ, NBG and SH shows that there was no re-sighting of individual dolphins within the 4 study areas, making them four independent management units and possibly distinct populations (Tang et al., 2021). There was a highly significant genetic difference between the humpback dolphin in XM and the nearest population in the PRE, making XM an independent unit (Chen et al., 2010a). Therefore, a total of seven units were recognized (Fig. 1).

|

Fig. 1 (a) Study area of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin in China (Chen et al., 2018; Chan, 2019; Peng et al., 2020), (b) Eastern-Pearl River Estuary (EPRE), (c) coastal waters of Eastern Zhanjiang (EZ), (d) coastal waters of Southwestern Hainan (SH), (e) Middle Pearl River Estuary (MPRE), (f) Western Pearl River Estuary (WPRE), (g) Xiamen Bay (XM), (h) Northern Beibu Gulf (NBG). Vessel traffic flow was expressed in different colors (purple to red), shaded grey area represents the distribution of humpback dolphin, ferry routes was represented by black line, and cargo vessel routes was represented by white line. |

Exposure to potential marine traffic by area was estimated according to the overlap of sea routes with the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin distribution. The sighting points of dolphins were projected onto the map. The four units (XM, EZ, NBG and SH) were established on the relevant references (Wang et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021a, 2021b), and the other three habitats in PRE were based on our 2015 – 2021 field investigations (Guo et al., 2022). The home range of dolphins was delineated using Minimum Convex Polygon (MCP) (Rako-Gospic et al., 2017; Cobarrubia-Russo et al., 2020).

The passenger ferry route information was downloaded from the OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org/). A 500 m buffer was implemented on both sides of the core route to accurately represent the actual lane width. This buffer was designed to account for ship deviations from the core route, as observed in the AIS data, which can be accessed at http://www.shipxy.com. Furthermore, it considered the possibility of ships making detours to avoid collisions. To comprehensively address potential risks, we also evaluated two alternative lane widths: 250 m and 750 m. These three widths were chosen to represent narrower, actual, and wider lane configurations, respectively. Contours of cargo vessel routes were drawn on the basis of the official chart from the Maritime Safety Administration of the People's Republic of China (https://ais.msa.gov.cn/). Large cargo ships typically adhere to prescribed waterways based on specific water depth requirements for their navigation. Consequently, our primary focus is on assessing the potential adverse effects of exposure risks by comparing various widths of ferry lanes.

Vessel routes were superimposed on dolphin distribution, and subsequently, the overlap area of the ship routes with the habitat was calculated. Finally the overlap ratio (xi, range 0 – 1) was determined by dividing the overlapping area by the entire habitat area. The exposure risk (Ei, range 1 – 3) of each area to potential marine traffic was calculated according to the following formula (Hodgson et al., 2016; Hauser et al., 2018):

| $ {E_i} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {2.667{x_i}{\text{ + 1, }}0 \leqslant {x_i} < 0.75} \\ {3, {\text{ }}{x_i} > 0.75} \end{array}} \right. . $ | (1) |

Any factors that could affect the vulnerability of the dolphins to marine traffic were taken into consideraton in the sensitivity score (range 1 – 3). They include biological influences, exposure frequency, and biological and ecological characteristics of threatened (sub)populations (Gardali et al., 2012; Hodgson et al., 2016; Hauser et al., 2018). Biological influences include vessel disturbance, vessel collision, and noise. Frequency of exposure is represented by vessel traffic flow; the data was visualized from Marine Traffic. Biological and ecological characteristics include sensitivity to climate change, relative population abundance and current status. The specific scoring criteria were as follows:

Disturbance caused by vessels received a score of 1 when there was no evidence of behavioral responses or if the presence of vessels did not elicit any observable reaction. It received a score of 2 if there was evidence supporting moderate behavioral responses or short-term (within a day) spatial displacement in the presence of vessels, and a score of 3 if there were data supporting intense behavioral responses or long-term (> 1 day) spatial displacement. The potential for vessel collision was categorized as 1 when there was no evidence that collisions had caused direct injury or when such collisions were unlikely to occur. It was scored as 2 if there was evidence that collisions had caused sub-lethal effects or if there was a possibility of injury resulting from collisions. It received a score of 3 if there was evidence of documented mortality or major injuries resulting from vessel collisions. The acoustic impacts of vessel sounds were scored as 1 if there was no evidence to suggest that underwater noise would interfere with animals. It received a score of 2 if evidence suggested that noise had the potential to mask auditory signals or result in short-term hearing loss. It was scored as 3 if there was substantial evidence that underwater sound could mask communication, affect sound production parameters, or impact long-term hearing loss, ultimately leading to chronic health effects.

Vessel frequency was scored as 1 if sea lanes had no or only a small overlap with dolphins' habitat, and maritime traffic flow was low within the habitat. It was scored as 2 if there was a moderate overlap between sea lanes and habitats, and maritime traffic flow was moderate. It received a score of 3 if there was a large overlap between sea lanes and habitats, and maritime traffic flow was high.

Sensitivity to climate change was designated a score of 1 for relatively low sensitivity, 2 for intermediate sensitivity, and 3 for the highest sensitivity. Subpopulation size was scored as 1 if the size was larger than the upper quartile of the overall abundance in China. It was scored as 2 if the size was smaller than the upper quartile but larger than the lower quartile. A score of 3 was assigned if the size was smaller than the lower quartile. Population trends received a score of 1 for increasing subpopulations, 2 for stable subpopulations, and 3 for decreasing subpopulations. A score of 2 was assigned to subpopulations with an unknown status to avoid assuming positive or negative trends in the absence of data.

A broad review of the literature was conducted for the seven assessment indicators. Given that all humpback dolphins in China are of one species and share similar ecological characteristics, all units received the same score for disturbance, acoustic impacts and climate change. The other 4 indicators were objectively scored according to unit-specific references. The sensitivity score for each (sub)population was calculated from the mean score across all 7 factors.

2.4 Vulnerability CalculationVulnerability is a synthetic assessment based on the combination of the effect of spatial exposure and several aspects of sensitivity to vessels (Hauser et al., 2018). Vulnerability for each unit (Vi, range 1 – 9) was calculated by the following formula:

| $ {V_i} = {E_i} \times {S_i} . $ | (2) |

Ei, exposure score, range 1 – 3; Si, sensitivity score, range 1 – 3.

(Sub) populations that had no spatial overlap with the routes were not excluded because we only mapped ferry and cargo vessels routes. However, the hotspots of fishing boats have not been identified. In addition, some smallsized vessels that have potential effects on the dolphins did not necessarily sail on the projected vessel routes in the open water of the dolphin habitat. Thus, the risk posed by marine traffic could not be eliminated.

2.5 Analysis of Marine Traffic Exposure EffectsThe EPRE is deemed to be the most vulnerable among the seven habitats. Thus, additional field data was collected to analyze the effects of marine traffic in order to make specific conservation suggestions.

Boat-based field surveys were conducted from October 2015 to December 2021, with sea state ≤ 3 on the Beaufort scale. Surveys did not follow predetermined routes but searched for dolphins inshore waters at depths less than 30 m and less than 20 km from shore, which are the preferred habitats for humpback dolphins (Jefferson and Curry, 2015). Each survey was staffed with range 2 – 3 experienced observers. Once the humpback dolphins were sighted and the initial behavior of the animals was recorded (Chan and Karczmarski, 2017), environmental data, geographic location, passing vessels and animal behavior were recorded at the start and end of the encounter and in 10-minute intervals throughout. Vessel numbers and names were recorded. Relevant information was found in the AIS service provided by the maritime safety administration of the People's Republic of China.

Both fishing and non-fishing vessels were documented. Dolphin response to passing vessels was described as no reaction, attraction and avoidance. The Chi-Squared Test determined the significant differences among responses to the various vessels.

2.6 Uncertainty AnalysisUncertainty (range 1 – 3) to both exposure and sensitivity variables was analyzed to reflect the knowledge gap between/within study areas, and to consummate the scoring system.

Exposure uncertainty (range 1 – 3) was scored according to: low uncertainty (score 1): dolphin range based on multiple years of observation (3+) reported in scientific papers or reports, representing 3+ survey methods in multiple portions of the (sub)population's annual range; moderate uncertainty (score 2): dolphin range is based on < 3 years of observation reported in scientific papers or reports, represents < 3 survey methods that are sampled in only limited portions of the (sub)population annual range, or is estimated from models; and high uncertainty (score 3): dolphin range is generalized based on a few published scientific papers or reports with limited spatial coverage. Range may represent best estimates of seasonal rather than annual range.

Sensitivity uncertainty (range 1 – 3) was scored according to: low uncertainty (score 1): two or more empirical studies conducted directly on the (sub)population, with consensus between studies; moderate uncertainty (score 2): a single study conducted directly on the (sub)population from multiple studies but with conflicting results, or studies conducted on a related (sub)population; and high uncertainty (score 3): no studies directly on this (sub)population or adjacent (sub)population.

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 Exposure to Marine TrafficIn this study, 85% of the humpback dolphin distribution overlapped with either one or both ferry and cargo vessel routes (Fig. 1) There was an overlap of 9% ± 11% and exposure scores of 1.23 ± 0.31 (Table 1). Notably, XM and EPRE regions exhibited relatively high overlap ratios (XM: 0.21, EPRE: 0.31), consequently yielding high exposure scores (XM: 1.56, EPRE: 1.82). When the width of the lanes was reduced to 500 m, the overlap ratios for these two regions decreased to 0.15 and 0.20, leading to a decline in exposure scores to 1.40 and 1.54, respectively. Conversely, when the lane width was expanded to 1500 m, the overlap ratios increased to 0.28 and 0.41, resulting in elevated exposure scores of 1.74 and 2.09. Notably, the exposure score for MPRE was the lowest (MPRE: 1) due to the absence of a designated ship channel on the official chart. SH exhibited a relatively low exposure score (SH: 1) as the vessel route occupied only a minimal portion of the dolphin range (overlap ratio = 0.001). Although interactions between dolphins and fishing vessels have been documented (Chen et al., 2016; Or, 2017), the activity of fishing vessels is unpredictable. There is not enough data to accurately delineate the working area of fishing vessels.

|

|

Table 1 Exposure (E), sensitivity (S), vulnerability, and uncertainty (U) scores of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (sub)populations |

The great variation in exposure in these units is mainly dependent on the number of routes. Most routes in EPRE were positively correlated with the economic and geographical environment of the area and result in the highest exposure risk. A large number of passenger ferry routes have been set up in Lingding Bay, which strongly overlaps with the dolphin habitat (Chen et al., 2010b; Karczmarski et al., 2016; Or, 2017). In addition, two cargo routes connect Guangzhou and Shekou Ports to the open waters and pass through the dolphin habitat resulting in a high risk of exposure. Xiamen Bay is another high exposure area because several high-speed ferry and cargo routes penetrate dolphin habitats (Wang et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019).

A high degree of exposure results in a high injury rate. For example, there are a high number of collisions and/or propeller cuts in EPRE and XM (Wang et al., 2018; Chan and Karczmarski, 2019). Net entanglement and collisions are the most common causes of death for humpback dolphins in EPRE (Jefferson et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2022). 10% of the dolphins have physical injuries indicative of vessel collisions, propeller cuts and fishing-gear entanglements as illustrated in the Hongkong photo-identification catalog (Chan and Karczmarski, 2019). In XM, the second highest exposure risk area, the external injury rate was as high as 11.7%, which should be of concern given the small population size (n = 60, Wang et al., 2018). It is crucial to emphasize that in the event of a future increase in vessel traffic, which would necessitate the expansion of shipping lanes, the risk of injury could potentially worsen. Injury rates have not yet been calculated and reported for other habitats. However, several dolphin injuries of all types have been confirmed (Chen et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019).

3.2 Sensitivity to Marine TrafficSensitivity scores for the seven (sub)populations ranged from 2.43 to 2.86 (Table 1). Humpback dolphins have sensitivity scores of 3 for disturbance and the impact of noise. Except for the SH population, sensitivity to collision for the other six sites was 3.

The mere presence of vessels affects dolphin behavior and has a long-term impact on their use of the habitat. They display longer diving times in heavy traffic areas, and change directions and increase their swimming speeds to flee approaching ferries at high speeds. Also they change course and increase swimming speeds to follow fishing vessels at low speeds (Ng and Leung, 2003; Piwetz, 2012; Piwetz et al., 2021). A monthly shift of primary boat-dolphin interaction sites has been identified, which indicates the possibility of long-term impact (Wu et al., 2020). Noise generated by vessels also has potential impacts. Many studies document that vessel noise interferes with key biological functions from hearing masking, temporary or permanent damage to the auditory system, and, in some cases, death. Vessel noise elevates the background sound pressure of dolphins' habitats, and can be heard by the dolphins within their highly sensitive frequency range. It also overlaps with biologically significant sound frequencies and masks dolphin sounds at close range (Sims et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). There may be temporary changes in hearing sensitivity when the noise is particularly loud and/or the animals are constantly exposed to it. More and more incidents of dolphins straying into rivers were found in EPRE (Wu et al., 2018), which may be related to agerelated hearing loss, or compromised hearing due to longterm exposure to noise (Li et al., 2013; Finneran, 2015). Under chronic and/or repeated exposure to vessel noise, humpback dolphins and other cetaceans may even be killed (Li et al., 2018).

There are reports of sub-lethal and/or lethal injuries by collision in the six habitats (Chen et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Chan and Karczmarski, 2019; Li et al., 2019). Although no published evidence is currently available for SH, the possibility of collision cannot be excluded.

The sensitivity score of all (sub)populations to climate change is 3 (Fu et al., 2021). In essence, climate change has the potential to disrupt the ecological characteristics of habitats that are currently suitable for humpback dolphins. This disruption may force these dolphins to migrate to regions with a heightened exposure risk to vessel traffic. Furthermore, climate change can lead to alterations in the marine food-web structure, directly impacting fish population sizes (Cheung et al., 2013). These changes can indirectly affect the diet of humpback dolphins, potentially reducing their energy intake (Ning et al., 2020). If the current diet offers less energy and the dolphins are exposed to increased vessel traffic, it may lead to higher energy consumption, ultimately influencing the population's development.

Vessel frequency showed significant discrepancy among the seven study areas, and also in various waters within the same area (Fig. 1). There was high marine traffic flow in the waters of both EPRE and MPRE, which are of ecological importance for the dolphins. Although the MPRE has no defined sea lanes, the high number of vessels and low number of dolphins make this unit the most sensitive (Chen et al., 2010b; Chan, 2019). Unlike PRE, there is a thin part of the dolphin range in SH with high marine traffic, consequently it become the less vulnerable population.

Details of population sizes are presented in Table 2. The PRE population of 2059 humpback dolphins is the biggest population in the world. It is, unfortunately, declining (Chan, 2019). EZ and NBG populations are also declining as indicated by genetic analyses (Zhang et al., 2020). XM is currently the smallest known population in China with only 70 individuals and is also likely declining (Chen et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2020). There is no published demographic research for the SH population and the status remains unknown, but an interview from the official media suggested that 201 dolphins have been cataloged by investigators (see Hainan Daily Press).

|

|

Table 2 Summary of the ecological characteristics of humpback dolphins in China |

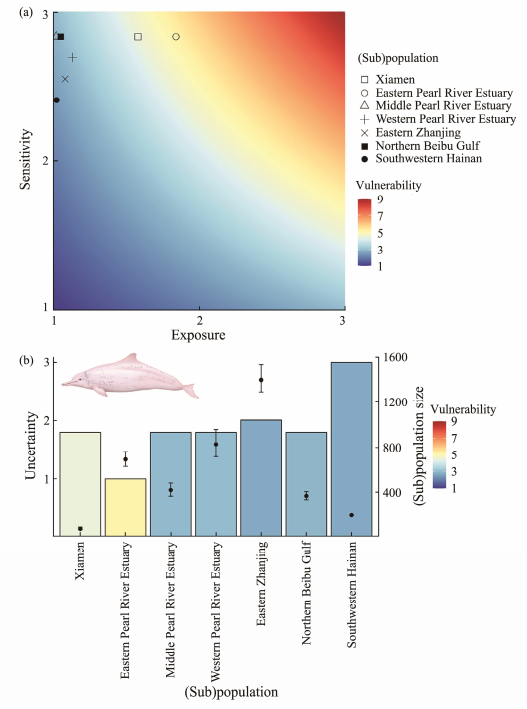

(Sub) population-specific vulnerability scores range from 2.43 to 5.21 (Fig. 2); an intermediate level among all units was 3.36 ± 1.04 (Table 1). Among the risks to (sub)populations, the EPRE and XM were relatively vulnerable at 5.21 and 4.47, respectively, largely because of high exposure to the vessel routes and specific features of their biology and ecology. The SH and EZ populations have relatively low vulnerability (SH: 2.43, EZ: 2.73) reflecting the low frequency of vessels and specific ecological conditions. The MPRE, WPRE, and NBG (sub)populations have a moderate vulnerability (2.86, 3.02, 2.95, respectively).

|

Fig. 2 Exposure, sensitivity and vulnerability scores across the seven Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (sub)populations (a), uncertainty scores and summary of humpback dolphins number across seven humpback dolphin (sub)populations in China (b). |

High vulnerability to vessels represents grimmer impacts of marine traffic on humpback dolphins. The areas with a high vulnerability score have a higher rate of injuries. The dolphins are also more likely to be disturbed by passing vessels, as, for example, being subjected to noise. Several adverse effects would have a combined impact on the survival of humpback dolphins. Although trauma may not cause death, it compromises their health conditions and diminishes the quality of the dolphins' habitats (Chan and Karczmarski, 2019). Physically weak animals living in compromised conditions would of course be further affected by passing vessels. Their daily energy budgets would be affected (Stockin et al., 2008; New et al., 2020) and communication interfered with (Sims et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017), which eventually accelerates a population decline.

Because the number of dolphins in EZ is the largest and there are fewer boats, it is a low vulnerable area (Xu et al., 2015). However, only one of three potential suitable habitats simulated in EZ was confirmed by field surveys, the others were located in strong shipping areas (Lin et al., 2021), suggesting that marine traffic is still of a great concern in low vulnerability areas. A recent study in NBG confirmed that the displacement of the humpback dolphin population from its original location was due to the interference of small high-speed boats (Li et al., 2015). These investigations all emphasize that populations with low vulnerability should receive the same attention as others with high vulnerability.

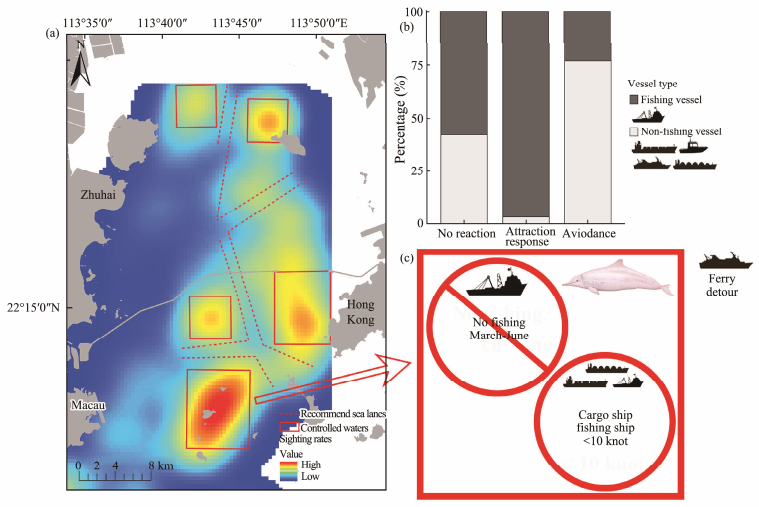

3.4 Influences of Types of Marine Traffic on Humpback Dolphin BehaviorDuring the 2015 – 2021 survey, 210 interactions between humpback dolphins and vessels were recorded (Fig. 3). 53.8% were identified as behavioral responses to both fishing and non-fishing vessels. The responses were significantly different (χ2 = 65.19, P < 0.01) since they were generally attracted to fishing vessels (83.1%) and avoided non-fishing vessels (95.2%).

|

Fig. 3 Suggested controlled areas for Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins and recommended sea lanes (red dash line) in Eastern Pearl River Estuary based on the distribution (Guo et al., 2022) (a), interactions recorded between the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins and vessels (b), conservation practices for different vessel types in control areas (c). |

Humpback dolphins approached fishing vessels probably due to increased success of foraging since. The vessels gather or stir up schools of fish (Bonizzoni et al., 2022). However, interactions with fishing vessels also increases collisions and/or entanglement with fishing gear. Although few studies have focused on the effect of noise on dolphins it is clear that it interferes with communications (Jensen et al., 2009; Pirotta et al., 2015), and increases the risk of injury and death (Bonizzoni et al., 2022). The PRE stranding data from 2003 to 2017 documents a total of 25 humpback dolphins were killed by collisions or propeller cuts. The majority, 20, were stranded in EPRE, and 2 in MPRE and 3 in WPRE (Sun et al., 2022). Fishing-gear entanglement also has higher incidence in EPRE than other two regions. Due to deficiency in fish resource in EPRE, dolphins forage following fishing vessels which increases the risk of injury.

The avoidance of non-fishing vessels is essentially due to the interference of marine traffic on dolphin behavior, which has also been observed in other cetaceans (Pirotta et al., 2015; Wisniewska et al., 2018; Sprogis et al., 2020). Previous studies have documented that most humpback dolphins are deterred by high-speed non-fishing vessels (Ng and Leung, 2003; Piwetz, 2012; Li et al., 2015). In less disruptive situations individuals make use of low vessel density periods or regions to return to their original activities (Marley et al., 2017). When the level of interaction between vessel and dolphin is high enough to significantly alter the cumulative behavioral budget of dolphins, it induces adverse biological consequences such as decreasing survival and the reproductive success which is amplified in population-level effects (Bas et al., 2017). Although most non-fishing vessels do not directly target humpback dolphins, long-term disturbance due to dense vessel traffic flow leads to a decrease in their relative abundance; this has been observed in other cetaceans (Bejder et al., 2006).

3.5 Uncertainty AssessmentUncertainty has been used in this study to characterize a knowledge gap in order to guide future studies and conservation practices. Uncertainty scores for the seven (sub)populations ranged from 1.25 to 2.50 (Table 1). It was commonly higher for the less vulnerable (sub)populations, particularly for SH, which have not currently been studied with respect to population size nor status, underscoring the need for more data and continued monitoring in the region (Fig. 2). The EPRE is the most vulnerable subpopulation with the lowest uncertainty, prompting the need for urgent conservation practices.

Animal distribution is the foundation of all conservation efforts and for all risk assessment. The habitats of humpback dolphins in the seven areas were quite delineated, therefore their exposure uncertainty is acceptable. However, in the context of the rapidly changing offshore environment, a dolphin's use of a particular habitat may change in space and over time, so field study ensures the best suitable conservation measures. Besides, biological and ecological features of humpback dolphins may affect their response to vessels and the severity of impact. Though several studies have focused on the potential biological impacts of marine traffic on humpback dolphins, considering the unique ecological and biological characteristics of seven habitats for them, habitat-specific ecological study is needed to better understand local populations; area-based risk assessment is also required to customize conservation measures.

3.6 Protection StrategySeveral strategies to mitigate the impact of vessel disturbance have proven effective. These include detours around animal habitats, avoiding visible animals, minimizing noise and reducing boat speed (Silber et al., 2012; Huntington et al., 2015; McWhinnie et al., 2018; Frantzis et al., 2019; Mei et al., 2021). Modifying ship noise, defining marine protected areas (MPAs) within which shipping activities would be restricted, and seasonal and geographical restrictions have all been proposed as solutions for reducing the impact of shipping noise on humpback dolphins (Li et al., 2018). In this study, we suggest spatial management with seasonal constraints, which define the management framework based on the spatio-temporal distribution characteristics of humpback dolphins.

The EPRE area with the highest vulnerability score was chosen as the case for protection in this study, similar conservation practices could be applied in other habitats. Controlled areas were first defined according to the core distribution of humpback dolphins (Fig. 3) (Guo et al., 2022). Then, management regulations were formulated for different types of vessels based on references and our empirical study:

1) Fishing vessels prohibited from control waters from March to June. Intensive fishing practices contribute to elevated injury rates, and any compromise in individual health conditions amplifies the overall vulnerability of the entire population. In order to decrease disturbance to the overall viability of the population, special attention should be paid to pregnant or lactating dolphins. Mothers are in the most vulnerable life stage due to their high energy demands. Fisheries interactions or disturbance disrupt foraging, resulting in reduced body reserves and eventually decreased reproductive success (Farmer et al., 2018). Mother-calf pairs are also often more sensitive to vessel disturbance (Dunlop et al., 2010). Studies show that the birth peak is from March to June (Jefferson et al., 2012). Therefore, this measure would not only reduce the risk of dolphin injury but also reduce the feeding pressure from overfishing. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the fishing closure period mandated by the Chinese Government extends from May 1st to April 15th. This time frame partially aligns with the proposed control period. Hence, implementing the proposed measures in May would be readily achievable.

2) The speeds of cargo and fishing ships should be limited to below 10 knots in the control waters. This reduces the risk of both disturbance and collision. When a fishing boat operates below 10 knots, it attracts dolphins; cargo ships at higher speeds (about 10 – 12 knots) disturb them. According to the simulation model, the probability of a lethal injury to cetaceans asymptotically approaches 1 when vessel speeds are above 15 knots, and drops below 0.5 at 11.8 knots (Vanderlaan and Taggart, 2007). Therefore, it is better to limit the ship speed to less than 10 knots.

3) High-speed ferries should detour the control waters and avoid the habitats to reduce interference and collisions. If it is necessary to pass through the habitat, it is strongly recommended to use one of two defined sea lanes with 1000 m width (Fig. 3). During our survey, dolphins were usually disturbed by ferries at a speed of more than 30 knots, and the noise masks communication (Sims et al., 2012). Thereforeit it is best for high-speed ferries to avoid the areas that dolphins frequent. Our results show that exposure and vulnerability are closely related to ferry sea lanes that overlap with the habitat. Reducing the proportion of overlap is a possible solution to alleviate the exposure risk and vulnerability.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFF1301603), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2021A1515011467) in China, the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai), China (Nos. 311020003 and 31102 1004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32201290), and the 71st batch of China Postdoctoral Science Funding (No. 2022M713560). We sincerely thank the Guangdong Pearl River Estuary Chinese White Dolphin Reserve and Guangdong Jiangmen Chinese White Dolphin Provincial Nature Reserve for assistance with the sample collection of the stranded dolphins.

Bas, A. A., Christiansen, F., Öztürk, B., Öztürk, A. A., Erdogan, M. A., and Watson, L. J., 2017. Marine vessels alter the behaviour of bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus in the Istanbul Strait, Turkey. Endangered Species Research, 34: 1-14. DOI:10.3354/esr00836 (  0) 0) |

Bejder, L., Samuels, A., Whitehead, H., Gales, N., Mann, J., Connor, R., et al., 2006. Decline in relative abundance of bottlenose dolphins exposed to long-term disturbance. Conservation Biology, 20(6): 1791-1798. DOI:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00540.x (  0) 0) |

Bonizzoni, S., Hamilton, S., Reeves, R. R., Genov, T., and Bearzi, G., 2022. Odontocete cetaceans foraging behind trawlers, worldwide. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 32(3): 827-877. DOI:10.1007/s11160-022-09712-z (  0) 0) |

Burgess, M. G., McDermott, G. R., Owashi, B., Peavey Reeves, L. E., Clavelle, T., Ovando, D., et al., 2018. Protecting marine mammals, turtles, and birds by rebuilding global fisheries. Science, 359(6381): 1255-1258. DOI:10.1126/science.aao4248 (  0) 0) |

Chan, S. C. Y., 2019. Demography and socio-ecology of IndoPacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) metapopulation in the Pearl River Estuary. PhD thesis. Hong Kong.

(  0) 0) |

Chan, S. C. Y., and Karczmarski, L., 2017. Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in Hong Kong: Modelling demographic parameters with mark-recapture techniques. PLoS One, 12(3): e0174029. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0174029 (  0) 0) |

Chan, S. C. Y., and Karczmarski, L., 2019. Epidermal lesions and injuries of coastal dolphins as indicators of ecological health. EcoHealth, 16(3): 576-582. DOI:10.1007/s10393-019-01428-0 (  0) 0) |

Chen, B., Gao, H., Jefferson, T. A., Lu, Y., Wang, L., Li, S., et al., 2018. Survival rate and population size of Indo‐Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in Xiamen Bay, China. Marine Mammal Science, 34(4): 1018-1033. DOI:10.1111/mms.12510 (  0) 0) |

Chen, B., Xu, X., Jefferson, T. A., Olson, P. A., Qin, Q., Zhang, H., et al., 2016. Conservation status of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) in the northern Beibu Gulf, China. Advances in Marine Biology, 73: 119-139. (  0) 0) |

Chen, C., Jefferson, T. A., Chen, B., and Wang, Y., 2022. Geographic range size, water temperature, and extrinsic threats predict the extinction risk in global cetaceans. Global Change Biology, 28(22): 6541-6555. DOI:10.1111/gcb.16385 (  0) 0) |

Chen, L., Caballero, S., Zhou, K., and Yang, G., 2010a. Molecular phylogenetics and population structure of Sousa chinensis in Chinese waters inferred from mitochondrial control region sequences. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 38(5): 897-905. DOI:10.1016/j.bse.2010.09.009 (  0) 0) |

Chen, T., Hung, S. K., Qiu, Y., Jia, X., and Jefferson, T. A., 2010b. Distribution, abundance, and individual movements of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in the Pearl River Estuary, China. Mammalia, 74(2): 117-125. DOI:10.1515/mamm.2010.024 (  0) 0) |

Cheung, W. W. L., Sarmiento, J. L., Dunne, J., Frölicher, T. L., Lam, V. W. Y., Deng Palomares, M. L., et al., 2013. Shrinking of fishes exacerbates impacts of global ocean changes on marine ecosystems. Nature Climate Change, 3(3): 254-258. DOI:10.1038/nclimate1691 (  0) 0) |

Cobarrubia-Russo, S. E., Barreto-Esnal, G. R., MoleroLizarraga, A. E., and Mariani-Di Lena, M. A., 2020. Individual home ranges of Tursiops truncatus and their overlap with ranges of Stenella frontalis and fishermen in Aragua, Venezuela, South Caribbean. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 100(5): 857-866. DOI:10.1017/S0025315420000557 (  0) 0) |

Davidson, A. D., Boyer, A. G., Kim, H., Pompa-Mansilla, S., Hamilton, M. J., Costa, D. P., et al., 2012. Drivers and hotspots of extinction risk in marine mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109: 3395-3400. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1121469109 (  0) 0) |

Dunlop, R. A., Cato, D. H., and Noad, M. J., 2010. Your attention please: Increasing ambient noise levels elicits a change in communication behaviour in humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1693): 2521-2529. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2009.2319 (  0) 0) |

Farmer, N. A., Noren, D. P., Fougères, E. M., Machernis, A., and Baker, K., 2018. Resilience of the endangered sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus to foraging disturbance in the Gulf of Mexico, USA: A bioenergetic approach. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 589: 241-261. DOI:10.3354/meps12457 (  0) 0) |

Finneran, J. J., 2015. Noise-induced hearing loss in marine mammals: A review of temporary threshold shift studies from 1996 to 2015. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 138(3): 1702-1726. DOI:10.1121/1.4927418 (  0) 0) |

Frantzis, A., Leaper, R., Alexiadou, P., Prospathopoulos, A., and Lekkas, D., 2019. Shipping routes through core habitat of endangered sperm whales along the Hellenic Trench, Greece: Can we reduce collision risks?. PLoS One, 14(2): e0212016. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0212016 (  0) 0) |

Fu, J., Zhao, L., Liu, C., and Sun, B., 2021. Estimating the impact of climate change on the potential distribution of IndoPacific humpback dolphins with species distribution model. PeerJ, 9: e12001. DOI:10.7717/peerj.12001 (  0) 0) |

Gardali, T., Seavy, N. E., DiGaudio, R. T., and Comrack, L. A., 2012. A climate change vulnerability assessment of California's at-risk birds. PLoS One, 7(3): e29507. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0029507 (  0) 0) |

Grech, A., and Marsh, H., 2008. Rapid assessment of risks to a mobile marine mammal in an ecosystem-scale marine protected area. Conservation Biology, 22(3): 711-720. DOI:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00923.x (  0) 0) |

Guo, L., Luo, D., Yu, R. Q., Zeng, C., Huang, N., Wang, H., et al., 2022. Habitat decline of the largest known Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) population in poorly protected areas associated with the hypoxic zone. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9: 1048959. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2022.1048959 (  0) 0) |

Hauser, D. D. W., Laidre, K. L., and Stern, H. L., 2018. Vulnerability of Arctic marine mammals to vessel traffic in the increasingly ice-free northwest passage and northern sea route. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(29): 7617-7622. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1803543115 (  0) 0) |

Hodgson, E. E., Essington, T. E., and Kaplan, I. C., 2016. Extending vulnerability assessment to include life stages considerations. PLoS One, 11(7): e0158917. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0158917 (  0) 0) |

Huang, S. L., and Karczmarski, L., 2014. Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins: A demographic perspective of a threatened species. Primates and Cetaceans, 2: 249-272. (  0) 0) |

Huntington, H. P., Daniel, R., Hartsig, A., Harun, K., Heiman, M., Meehan, R., et al., 2015. Vessels, risks, and rules: Planning for safe shipping in Bering Strait. Marine Policy, 51: 119-127. DOI:10.1016/j.marpol.2014.07.027 (  0) 0) |

IUCN. 2022. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-1, https://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed on 2022.

(  0) 0) |

Jefferson, T. A., and Curry, B. E., 2015. Humpback dolphins: A brief introduction to the genus Sousa. Advances in Marine Biology, 72: 1-16. (  0) 0) |

Jefferson, T. A., and Hung, S. K., 2004. A review of the status of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) in Chinese waters. Aquatic Mammals, 30(1): 149-158. DOI:10.1578/AM.30.1.2004.149 (  0) 0) |

Jefferson, T. A., and Smith, B. D., 2016. Re-assessment of the conservation status of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) using the IUCN Red List criteria. Advances in Marine Biology, 73: 1-26. (  0) 0) |

Jefferson, T. A., Hung, S. K., and Lam, P. K. S., 2006. Strandings, mortality and morbidity of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in Hong Kong, with emphasis on the role of organochlorine contaminants. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 8(2): 181-193. (  0) 0) |

Jefferson, T. A., Hung, S. K., Robertson, K. M., and Archer, F. I., 2012. Life history of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin in the Pearl River Estuary, southern China. Marine Mammal Science, 28(1): 84-104. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00462.x (  0) 0) |

Jefferson, T. A., Smith, B. D., Braulik, G. T., and Perrin, W., 2017. Sousa chinensis (errata version published in 2018). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e. T82031425A 123794774, https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T82031425A50372332.en. Accessed on 2022.

(  0) 0) |

Jensen, F. H., Bejder, L., Wahlberg, M., Aguilar de Soto, N., Johnson, M., and Madsen, P. T., 2009. Vessel noise effects on delphinid communication. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 395: 161-175. DOI:10.3354/meps08204 (  0) 0) |

Karczmarski, L., Huang, S. L., Or, C. K. M., Gui, D., Chan, S. C. Y., Lin, W., et al., 2016. Humpback dolphins in Hong Kong and the Pearl River Delta: Status, threats and conservation challenges. Advances in Marine Biology, 73: 27-64. (  0) 0) |

Karczmarski, L., Thornton, M., and Cockcroft, V. G., 1997. Description of selected behaviours of humpback dolphins Sousa chinensis. Aquatic Mammals, 23: 127-133. (  0) 0) |

Kraus, S. D., Brown, M. W., Caswell, H., Clark, C. W., Fujiwara, M., Hamilton, P. K., et al., 2005. North Atlantic right whales in crisis. Science, 309(5734): 561-562. DOI:10.1126/science.1111200 (  0) 0) |

Laidre, K. L., Stirling, I., Lowry, L. F., Wiig, O., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., and Ferguson, S. H., 2008. Quantifying the sensitivity of Arctic marine mammals to climate-induced habitat change. Ecological Applications, 18(sp2): S97-S125. DOI:10.1890/06-0546.1 (  0) 0) |

Li, M., Wang, X., Hung, S. K., Xu, Y., and Chen, T., 2019. Indo‐ Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in the Moyang River Estuary: The western part of the world's largest population of humpback dolphins. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 29(5): 798-808. DOI:10.1002/aqc.3055 (  0) 0) |

Li, S., 2020. Humpback dolphins at risk of extinction. Science, 367(6484): 1313-1314. (  0) 0) |

Li, S., Liu, M., Dong, L., Dong, J., and Wang, D., 2018. Potential impacts of shipping noise on Indo-Pacific hump-back dolphins and implications for regulation and mitigation: A review. Integrative Zoology, 13(5): 495-506. DOI:10.1111/1749-4877.12304 (  0) 0) |

Li, S., Wang, D., Wang, K., Hoffmann-Kuhnt, M., Fernando, N., Taylor, E. A., et al., 2013. Possible age-related hearing loss (presbycusis) and corresponding change in echolocation parameters in a stranded Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(22): 4144-4153. DOI:10.1242/jeb.091504 (  0) 0) |

Li, S., Wu, H., Xu, Y., Peng, C., Fang, L., Lin, M., et al., 2015. Midto high-frequency noise from high-speed boats and its potential impacts on humpback dolphins. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 138(2): 942-952. DOI:10.1121/1.4927416 (  0) 0) |

Liu, M., Dong, L., Lin, M., and Li, S., 2017. Broadband ship noise and its potential impacts on Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins: Implications for conservation and management. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 142(5): 2766-2775. DOI:10.1121/1.5009444 (  0) 0) |

Lin, M., Liu, M., Lek, S., Dong, L., Zhang, P., Gozlan, R. E., et al., 2021. Modelling habitat suitability of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin using artificial neural network: The influence of shipping. Ecological Informatics, 62: 101274. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101274 (  0) 0) |

Liu, M., Lin, M., Lusseau, D., and Li, S., 2021a. Intrapopulation variability in group size of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis). Frontiers in Marine Science, 8: 671568. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2021.671568 (  0) 0) |

Liu, M., Lin, M., Tang, X., Dong, L., Zhang, P., Lusseau, D., et al., 2021b. Group size of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis): An examination of methodological and biogeographical variances. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8: 655595. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2021.655595 (  0) 0) |

Lundquist, D., Gemmell, N. J., and Würsig, B., 2012. Behavioural responses of dusky dolphin groups (Lagenorhynchus obscurus) to tour vessels off Kaikoura, New Zealand. PLoS One, 7(7): e41969. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0041969 (  0) 0) |

Marcotte, D., Hung, S. K., and Caquard, S., 2015. Mapping cumulative impacts on Hong Kong's pink dolphin population. Ocean & Coastal Management, 109: 51-63. (  0) 0) |

Marley, S. A., Salgado Kent, C. P., Erbe, C., and Parnum, I. M., 2017. Effects of vessel traffic and underwater noise on the movement, behaviour and vocalisations of bottlenose dolphins in an urbanised estuary. Scientific Reports, 7(1): 13437. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-13252-z (  0) 0) |

Mattson, M. C., Thomas, J. A., and St. Aubin, D., 2005. Effects of boat activity on the behavior of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in waters surrounding Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. Aquatic Mammals, 31(1): 133-140. DOI:10.1578/AM.31.1.2005.133 (  0) 0) |

Maxwell, S. M., Hazen, E. L., Bograd, S. J., Halpern, B. S., Breed, G. A., Nickel, B., et al., 2013. Cumulative human impacts on marine predators. Nature Communications, 4(1): 2688. DOI:10.1038/ncomms3688 (  0) 0) |

McWhinnie, L. H., Halliday, W. D., Insley, S. J., Hilliard, C., and Canessa, R. R., 2018. Vessel traffic in the Canadian Arctic: Management solutions for minimizing impacts on whales in a changing northern region. Ocean & Coastal Management, 160: 1-17. (  0) 0) |

Mei, Z., Han, Y., Turvey, S. T., Liu, J., Wang, Z., Nabi, G., et al., 2021. Mitigating the effect of shipping on freshwater cetaceans: The case study of the Yangtze finless porpoise. Biological Conservation, 257: 109132. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109132 (  0) 0) |

New, L., Lusseau, D., and Harcourt, R., 2020. Dolphins and boats: When is a disturbance, disturbing?. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7: 353. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2020.00353 (  0) 0) |

New, L. F., Harwood, J., Thomas, L., Donovan, C., Clark, J. S., Hastie, G., et al., 2013. Modelling the biological significance of behavioural change in coastal bottlenose dolphins in response to disturbance. Functional Ecology, 27(2): 314-322. DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.12052 (  0) 0) |

Ng, S. L., and Leung, S., 2003. Behavioral response of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) to vessel traffic. Marine Environmental Research, 56(5): 555-567. DOI:10.1016/S0141-1136(03)00041-2 (  0) 0) |

Ning, X., Gui, D., He, X., and Wu, Y., 2020. Diet shifts explain temporal trends of pollutant levels in Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) from the Pearl River Estuary, China. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(20): 13110-13120. (  0) 0) |

Nowacek, S. M., Wells, R. S., and Solow, A. R., 2001. Shortterm effects of boat traffic on bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, in Sarasota Bay, Florida. Marine Mammal Science, 17(4): 673-688. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01292.x (  0) 0) |

Or, C. K., 2017. Socio-spatial ecology of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in Hong Kong and the Pearl River Estuary. PhD thesis. Hong Kong.

(  0) 0) |

Papale, E., Azzolin, M., and Giacoma, C., 2012. Vessel traffic affects bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) behaviour in waters surrounding Lampedusa Island, South Italy. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 92(8): 1877-1885. DOI:10.1017/S002531541100083X (  0) 0) |

Parsons, E. C., and Jefferson, T. A., 2000. Post-mortem investigations on stranded dolphins and porpoises from Hong Kong waters. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 36(2): 342-356. DOI:10.7589/0090-3558-36.2.342 (  0) 0) |

Peng, C., Wu, H., Wang, X., Zhu, Q., Jefferson, T. A., Wang, C. C., et al., 2020. Abundance and residency dynamics of the Indo‐Pacific humpback dolphin, Sousa chinensis, in the Dafengjiang River Estuary, China. Marine Mammal Science, 36(2): 623-637. DOI:10.1111/mms.12663 (  0) 0) |

Pirotta, E., Merchant, N. D., Thompson, P. M., Barton, T. R., and Lusseau, D., 2015. Quantifying the effect of boat disturbance on bottlenose dolphin foraging activity. Biological Conservation, 181: 82-89. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.003 (  0) 0) |

Piwetz, S., 2012. Short note: Influence of vessel traffic on movements of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) off Lantau Island, Hong Kong. Aquatic Mammals, 38(3): 325-331. DOI:10.1578/AM.38.3.2012.325 (  0) 0) |

Piwetz, S., Jefferson, T. A., and Würsig, B., 2021. Effects of coastal construction on Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) behavior and habitat-use off Hong Kong. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8: 572535. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2021.572535 (  0) 0) |

Rako-Gospić, N., Radulović, M., Vučur, T., Pleslić, G., Holcer, D., and Mackelworth, P., 2017. Factor associated variations in the home range of a resident Adriatic common bottlenose dolphin population. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 124(1): 234-244. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.07.040 (  0) 0) |

Richardson, W. J., Greene Jr., C. R., Malme, C. I., and Thomson, D. H.,, 2013. Marine Mammals and Noise. Academic Press, Beijing, 576pp.

(  0) 0) |

Schoeman, R. P., Patterson-Abrolat, C., and Plön, S., 2020. A global review of vessel collisions with marine animals. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7: 292. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2020.00292 (  0) 0) |

Senigaglia, V., Christiansen, F., Bejder, L., Gendron, D., Lundquist, D., Noren, D. P., et al., 2016. Meta-analyses of whalewatching impact studies: Comparisons of cetacean responses to disturbance. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 542: 251-263. DOI:10.3354/meps11497 (  0) 0) |

Silber, G. K., Vanderlaan, A. S., Tejedor Arceredillo, A., Johnson, L., Taggart, C. T., Brown, M. W., et al., 2012. The role of the international maritime organization in reducing vessel threat to whales: Process, options, action and effectiveness. Marine Policy, 36(6): 1221-1233. DOI:10.1016/j.marpol.2012.03.008 (  0) 0) |

Sims, P. Q., Hung, S. K., Würsig, B., and Miyazaki, N., 2012. High-speed vessel noises in west hong kong waters and their contributions relative to Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis). Journal of Marine Sciences, 12: 169103. (  0) 0) |

Sprogis, K. R., Videsen, S., and Madsen, P. T., 2020. Vessel noise levels drive behavioural responses of humpback whales with implications for whale-watching. eLife, 9: e56760. DOI:10.7554/eLife.56760 (  0) 0) |

Stockin, K. A., Lusseau, D., Binedell, V., Wiseman, N., and Orams, M. B., 2008. Tourism affects the behavioural budget of the common dolphin Delphinus sp. in the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 355: 287-295.

(  0) 0) |

Sun, X., Guo, L., Luo, D., Yu, R. Q., Yu, X., Liang, Y., et al., 2022. Long-term increase in mortality of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in the Pearl River Estuary following anthropic activities: Evidence from the stranded dolphin mortality analysis from 2003 to 2017. Environmental Pollution, 307: 119526. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119526 (  0) 0) |

Tang, X., Lin, W., Karczmarski, L., Lin, M., Chan, S. C. Y., Liu, M., et al., 2021. Photo-identification comparison of four Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin populations off Southeast China. Integrative Zoology, 16(4): 586-593. DOI:10.1111/1749-4877.12537 (  0) 0) |

Turner, B. L., Kasperson, R. E., Matson, P. A., McCarthy, J. J., Corell, R. W., Christensen, L., et al., 2003. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(14): 8074-8079. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1231335100 (  0) 0) |

Vanderlaan, A. S. M., and Taggart, C. T., 2007. Vessel collisions with whales: The probability of lethal injury based on vessel speed. Marine Mammal Science, 23(1): 144-156. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00098.x (  0) 0) |

Wang, X., Jutapruet, S., Huang, S. L., Turvey, S., Wu, F., and Zhu, Q., 2018. External injuries of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in Xiamen, China, and its adjacent waters as an indicator of potential fishery interactions. Aquatic Mammals, 44(3): 285-292. DOI:10.1578/AM.44.3.2018.285 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X., Wu, F., Turvey, S. T., Rosso, M., and Zhu, Q., 2016. Seasonal group characteristics and occurrence patterns of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in Xiamen Bay, Fujian Province, China. Journal of Mammalogy, 97(4): 1026-1032. DOI:10.1093/jmammal/gyw002 (  0) 0) |

Wisniewska, D. M., Johnson, M., Teilmann, J., Siebert, U., Galatius, A., Dietz, R., et al., 2018. High rates of vessel noise disrupt foraging in wild harbour porpoises (Phocoena phocoena). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1872): 20172314. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2017.2314 (  0) 0) |

Wu, F., Wang, X., Ding, X., Dai, Y., Zhao, L., and Zhu, Q., 2019. Occurrences of Xiamen Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis Osbeck, 1765), in waters of Weitou Bay, China. Acta Theriologica Sinica, 39(6): 608. (  0) 0) |

Wu, H., Peng, C., Huang, H., Jefferson, T. A., Huang, S. L., Chen, M., et al., 2020. Dolphin-watching tourism and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in Sanniang Bay, China: Impacts and solutions. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 66(1): 17. DOI:10.1007/s10344-019-1355-6 (  0) 0) |

Wu, Y., Xie, L., Huang, S. L., Li, P., Yuan, Z., and Liu, W., 2018. Using social media to strengthen public awareness of wildlife conservation. Ocean & Coastal Management, 153: 76-83. (  0) 0) |

Xu, X., Song, J., Zhang, Z., Li, P., Yang, G., and Zhou, K., 2015. The world's second largest population of humpback dolphins in the waters of Zhanjiang deserves the highest conservation priority. Scientific Reports, 5: 8147. DOI:10.1038/srep08147 (  0) 0) |

Zeng, Q., Lin, W., Dai, Y., Zhong, M., Wang, X., and Zhu, Q., 2020. Modeling demographic parameters of an edge-of-range population of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin in Xiamen Bay, China. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 40: 101462. DOI:10.1016/j.rsma.2020.101462 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, P., Zhao, Y., Li, C., Lin, M., Dong, L., Zhang, R., et al., 2020. An Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin genome reveals insights into chromosome evolution and the demography of a vulnerable species. iScience, 23(10): 101640. DOI:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101640 (  0) 0) |

2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23