The intertidal zone is one of the most sensitive ecosystems in the ocean, which is located at the junction of terrestrial and marine ecosystems. The beach occupies most of the temperate and tropical coastlines and is the most extensive intertidal system in the world (Wright and Short, 1983). It is an important place for recreation and entertainment as well as a buffer zone against the ocean (Sun et al., 2014). It is well known that beaches are rich in biological resources (McLachlan and Brown, 2006), and they are also vital feeding areas for commercial fish and bivalves (Schlacher et al., 2008). The beach ecosystem is composed of specialized organisms which can adapt to live in movable substrates and special harsh environments. These species all play important roles in the ecological functions of the beach ecosystem, such as primary producers (algae), decomposers (bacteria), and consumers (heterotrophic bacteria, meiofauna and macrofauna). Free-living marine nematodes are one of the most diverse organisms in the sandy beach. Nematodes are the most abundant metazoans in sediments, which dominate benthic meiofauna communities comprising more than half of the total abundance (Giere, 2009). A conservative estimation suggests that there may be 6900 described species and up to 50000 species if the undescribed species are also included (Appeltans et al., 2012). Due to their small body size, short generation period, and high turnover rates, nematodes process a considerable amount of energy in the benthic ecosystem (Giere, 2009). Nematode assemblage distributions are mainly influenced by environmental variables such as precipitation, amount of available organic matter, chlorophyll a concentration, temperature, dissolved oxygen, salinity, pH and sediment medium grain size (Harris, 1972; Fenchel, 1978; Nicholas, 2001; Giere, 2009; Hua et al., 2012; Hua et al., 2019; Cai et al., 2020; Baia et al., 2021). The sediments granularity was considered to be an important physical factor on nematode distribution and diversity in sandy beach ecosystem (Giere, 2009; Hua et al., 2016a; Cai et al., 2020). It is generally believed that fine sands, with a particle size of 125 – 250 μm, were most conducive to the growth of microbenthos and meiobenthos (Fenchel, 1978). At the same time, as a place for people's recreation, human disturbance has a significant impact on the beach. Studies have shown that excessive human trampling can reduce the abundance and species diversity of marine nematodes (Santos et al., 2021).

Species diversity indices have been extensively applied to evaluate the environmental conditions of estuaries (Cai et al., 2020), beaches (Santos et al., 2021), deep seas (Liao et al., 2020), and mangroves (Cai et al., 2020). They were also applied to assess the effects of oil pollution (Lv et al., 2011), heavy metal pollution (Hua et al., 2021), and coldwater mass effect (Xu et al., 2016). However, species diversity indices, including species richness and Shannon-Wiener diversity index, were derived from species abundance data, which did not take account of the diverse biological and autecological requirements of the taxa. These species attributes differ in space and time, but can not always reflect the ecological role played by certain taxa in the ecosystem (Sheaves, 2006). That is, changes in these species' attributes did not necessarily mean changes in ecosystem stability (Friberg et al., 2011). In contrast, functional diversity based on functional traits can predict ecosystem functioning to a certain extent, because these traits determine how organisms respond to non-biological environments (Bremner et al., 2003). However, in comparison to species diversity, methods of quantifying functional diversity are less well developed (Petchey and Gaston, 2002).

In the recent decade, with the increasing use of functional traits analyses to understand how environmental disturbances affect species' functional role, nematode functional traits analyses have received extensive attention (Liu et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2020; Kasia et al., 2021). Several traits of nematodes, such as feeding type, life strategy, and morphological features, were thought to be related to important ecological functions (Schratzberger et al., 2007). Additionally, the nematode functional traits, especially feeding type and life strategy, were revealed to be influenced by sediment granularity, water depth (Schratzberger et al., 2007), cold water mass (Liu et al., 2018), strong bottom water currents (Liao et al., 2020), sediment dissolved oxygen concentration (Kasia et al., 2021), etc., representing nematodes adaption to persist in a particular environment. However, the functional diversity indices were rarely applied for nematode community. An understanding of how nematodes functional diversity indices change following the environmental disturbances are urgently needed. On the other hand, the relationship between nematode species features and functional traits is still not fully established (Grzelak et al., 2016; Materatski et al., 2018). Several studies revealed a strong positive correlation between nematodes functional richness and species diversity metrics, indicating that increasing species richness might lead to increasing functional diversity (Schratzberger et al., 2007; Kasia et al., 2021). However, some other studies did not find a consistent pattern of internal connection between species and functional diversity (Leduc et al., 2013; Baldrighi and Manini, 2015). It has been reported that the inconsistent pattern of internal connection between species and functional diversity may depend on the types of functional traits in the analysis, species redundancy (Hooper et al., 2005), and environmental filtering in the study areas (Petchey and Goston, 2006). Therefore, the relationship between nematode species features and functional traits under different circumstances requires further investigation.

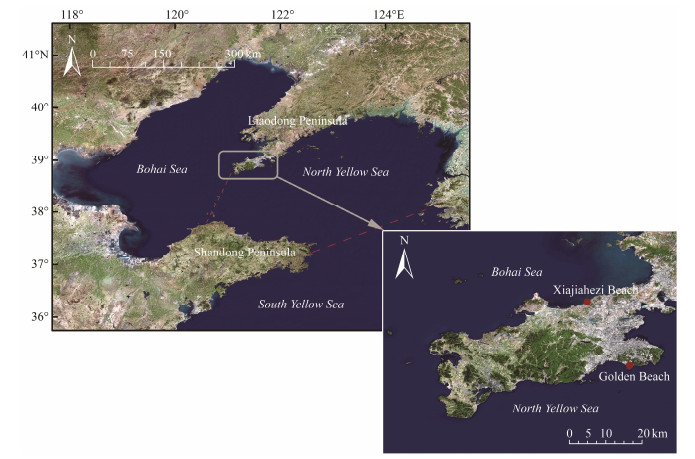

Dalian city, located at the southernmost tip of China's Liaodong Peninsula, borders the Yellow Sea at the east and the Bohai Sea at the west. It is a popular destination for domestic tourists and foreign visitors. Several studies on meiofauna, including marine nematode, were conducted at sandy beaches in Dalian (Lv et al., 2011; Hua et al., 2016b). Most of them focused on the distribution, abundance, and taxa assemblage of meiofauna, and revealed high abundance and dominance of nematode that can predict the important ecological role of nematode (Hua et al., 2016b). Some studies investigated the variation of nematode community structure related to natural (Song et al., 2021) or anthropogenic disturbance (Lv et al., 2011) in Dalian sandy beaches. However, only a few studies mainly focused on sandy beach nematodes diversity, while they did not involve the functional traits and functional diversity indices. Two sandy beaches in the present study are located on different coasts of the Liaodong peninsula, facing different seas, namely the Bohai Sea and the North Yellow Sea. Since the hydrological state of the two seas differed with respect to waves, tides, coastal currents, etc., the environmental variables are assumed to vary between the two beaches. Here, we applied the species diversity indices and functional diversity indices for the whole nematode community. We evaluated the spatial and seasonal variations of environmental variables of the study beaches, and their effects on nematode species diversity and functional diversity. The aims of the present study were to: 1) understand the environmental drivers for nematode species diversity and functional diversity in the study beaches, and how the nematode species change in response to specific environmental pressures; 2) investigate whether species diversity and functional diversity reveal similar response to the environmental changes.

2 Material and Methods 2.1 Study AreaDalian is located at the southernmost tip of the Liaodong Peninsula, bordering the Yellow Sea in the east and the Bohai Sea in the west. It is a warm temperate monsoon region. The annual mean temperature is 8 – 11℃. It is not severe cold in winter and not sweltering heat in summer. Its mild climate and multiple beaches as well as its importance in the modern history of China have attracted tourists. In 2015, Dalian received more than 60 million visitors. The present study chose two of the most famous sandy beaches in Dalian, namely Xiajiahezi Beach (121˚30΄E, 39˚02΄N) and Golden Beach (121˚35΄E, 38˚52΄N). Xiajiahezi Beach (XB in short) is located on the coast to the Bohai Sea. It is 1.2 km long and with an average slope of 1.3˚. The average height of spring tide is 233 cm, while 194 cm of neap tide (National marine data and information service, 2015). Golden Beach (GB in short) is located on the coast to the North Yellow Sea, with an average slope of 9.0˚. It is 1.0 km long and about 300 m wide. The average height of spring tide is 292 cm, while 235 cm of neap tide (National Marine Data and Information Service, 2015). Since the two beaches are located along different seas, the hydrodynamic regime differed with respect to waves, tides, coastal currents, etc. The Bohai Sea is a semi-enclosed continental shelf sea, and is surrounded by land at the north, west, and south. It is shallow, with a mean depth of 18 m. Currents are generally weak with a maximum surface velocity < 1.5 m s−1. Significant wave height is 0.3 – 0.7 m in near shore areas, and can reach 1.1 m in the Bohai Strait and the central Bohai Sea (Song and Duan, 2019). The tides in this area are irregular semi-diurnal tides, with a tidal range of 2 – 3 m. The Yellow Sea is between the Chinese mainland and the Korean Peninsula, and the line between the Chengshan Cape of China and the Changshan of Korea is the boundary between the North Yellow Sea and the South Yellow Sea. The mean water depth is 38 m in the North Yellow Sea (Su and Yuan, 2005). The tides in this area are regular semi-diurnal, with a tidal range of 2 – 4 m, and a current velocity of 1.5 – 2.5 m s−1 (Xu, 2002). The wave height is 2.0 – 6.0 m in autumn and winter in the North Yellow Sea (Su and Yuan, 2005).

|

Fig. 1 Map of sampling beaches. |

Two transects orientated perpendicular to the waterline with 100 m space each other were set up for nematodes sampling at each beach. Along each transect, three equally distanced sampling sites from high-water line to low-water line were established. In order to investigate the seasonal responses of nematode communities, sampling was conducted in December 2015, as well as April, July, and October of 2016 using Plexiglass cores (inner diameter of 4.8 cm). At each sampling site, three replicated core samples were collected to a depth of 20 cm. Two additional core samples were collected at each site for analyses of granulometric composition, chlorophyll a (Chl-a) concentration, and total organic matte (OM) content. The sea water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and pH were measured using In-Situ Smartroll MP at each beach.

2.3 Laboratory ProcessThe samples were stained with Rose Bengal for 24 – 48 h, and then sieved with 500-μm and 31-μm mesh sieves for extracting meiofauna. All meiofauna specimens were sorted and counted manually. From each sample, 200 randomly collected nematodes were mounted on permanent slides after a transparent treatment to prevent dehydration (Danovaro, 2010). Each nematode was identified to the species level, indicated by the genus name followed by sp.1, sp.2 according to Platt and Warwick(1983, 1988), Warwick et al. (1998), and Nemys online identification keys (Bezerra et al., 2021) using an Olympus BHS compound microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Sediment grain size was analyzed by the Laser Granularity Analyzer. Phi (Φ) = −log2 of grain size in mm were calculated and the medium grain size (MdΦ) indicated the central tendency or the average in particle size distribution. Sediment Organic matter content was measured using the K2Cr2O7-H2SO4 oxidization method (Liu et al., 2007). The sediment Chl-a concentration in the sediment was determined using the spectrophotoflurimetry method of Lorenzen and Jeffrey (1980) and Liu et al. (1998).

2.4 Definition of Functional GroupsNematode species were classified into functional groups using traits following a functional group classification for feeding type and life-history strategies. According to the buccal cavity morphology, nematode specimens were assigned to four different feeding types: selective deposit feeders (1A), non-selective deposit feeders (1B), epigrowth feeders (2A), and predators or omnivores (2B) (Wieser, 1953). Life-history strategies, namely individual colonizerpersistent (c-p) classes, were assigned following the family and genus list compiled by Bongers et al. (1991, 1995), Bongers and Bongers (1998). Each specimen was classified from 1 to 5 according to the list. Nematodes with short generation period, high egg production rates, and an ability to form dauer larvae are assigned extreme colonizers (c-p = 1), while nematodes with a long-life span and low reproduction rates are extreme persisters (c-p = 5). The family c-p class was assigned if a genus was not present in the Bongers' list.

2.5 Diversity IndicesNematode species abundance data (ind 10 cm−2) was fourth root transformed before statistical analyses. The nematode diversity indices per site were calculated, including species number (S), Margalef index (d), Shannon-Wiener diversity index (Hʹ, loge), Pielou evenness index (Jʹ), and Simpson index (1−λ) using the function DIVERSE in PRIMER v7 (Clarke and Gorley, 2015).

Functional diversity indices were calculated based on two datasets: a sampling site by species table, and a species by functional traits table including two traits, feeding type classification and c-p scores. Based on Gower dissimilarity matrix from the two traits, functional indices were calculated using dbFD function in the FD package. The functional diversity indices included functional richness (FRic), functional evenness (FEve), functional divergence (FDiv), functional dispersion (FDis) and Rao's quadratic entropy index (RaoQ) (Rao, 1982; Villéger et al., 2008; Linden et al., 2012). FRic measures the niche space occupied by all species in the community. FEve measures the evenness of species abundance distribution in a functional trait space. FDiv indicates how the abundance of species is spread along the functional trait volume. When the most abundant species are all clustered together in the functional trait range, the FDiv is low. Whereas, when the most abundant species possess extreme trait values, being far from each other in the functional trait space volume, the FDiv is high. FDis is the mean distance in multidimensional trait space of individual species to the centroid of all species. RaoQ treats each species as points in the multidimensional trait space mainly calculate the variation of species distance, and use Gower distance to measure the distance between species and biological traits (Rao, 1982; Villéger et al., 2008). Species were coded for the extent to which they displayed the categories of each biological traits using the 'binary'. The score was 0 or 1, and 0 means no affinity to a trait category while 1 means affinity.

2.6 Statistical AnalysisUsing the software ArcGis 10.2 to draw the map of sampling sites. IBM SPSS Statistics v20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform correlation analysis between nematode species diversity indices and functional diversity indices.

Multivariate analyses were performed using the PRIMER v7 + PERMANOVA add-on package (Anderson et al., 2008). Principal coordinates analysis (PCO) was performed to assess the overall differences in environmental variables on the basis of a (symmetric) resemblance matrix. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) were used to assess the differences of nematode species and functional diversity indices among beaches and months, as well as to assess the differences of their potential interactions. The tests of homogeneity of dispersion (PERMDISP) were performed to determine whether a significant PERMANOVA result is caused by the homogeneity of the sample dispersion within the group. Pairwise comparison of the observed significant differences was conducted further. The P-levels of the pairwise tests were corrected by Bonferroni corrections. A Distance-Based Linear Model (DistLM) using a forward selection procedure was applied to test the relationship between environmental variables with the nematode abundance and diversity indices of two beaches combined or each beach individually.

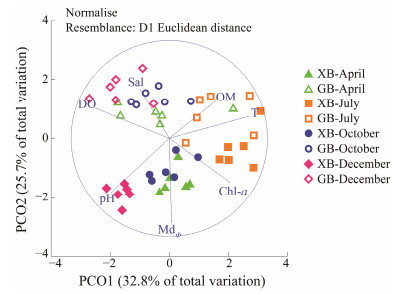

3 Results 3.1 Environmental VariablesThe environmental variables of Xiajiahezi Beach (XB) and Golden Beach (GB) were averaged by sampling time and listed in Table 1. These variables varied spatially and seasonally. PCO plot detected the spatial and seasonal differences of environmental variables (Fig.2). A difference among seasons was noted along the first principal coordinate (PCO1), and a difference between beaches was observed along the second principal coordinate (PCO2). The two principal coordinates explained 58.5% of the total environmental variability. High positive correlations (> 0.5) of seawater temperature and Chl-a concentration with PCO1, as well as high negative correlations of dissolved oxygen concentration and pH value with PCO1, were observed, explaining 32.8% of the seasonal environmental variability (Fig.2). Higher values of Chl-a concentration, and lower values of oxygen concentration, pH were observed in hotter months. The spatial variation was mainly due to MdΦ, pH, and sea water salinity, which had high correlations with PCO2 (Fig.2). The environment of XB is characterized with fine granularity, lower salinity, higher pH, higher Chl-a concentration.

|

|

Table 1 Mean values of environmental variables at two study beaches |

|

Fig. 2 PCO plot based on environmental variables. Abbreviations are same with Table 1. |

PERMANOVA test also revealed significant effects of site, time, and the interaction between them on different environmental variables (Table 2). All examined environmental variables except OM content were significantly different between the two beaches (Table 2). Sea water pH, Chl-a concentration and sediment MdΦ were higher while temperature and DO were lower at XB sites than at GB sites (Table 2). At the same time, PERMDISP analysis suggested a cautious interpretation of the significant differences in DO and MdΦ may be caused by the within-group dispersion. Significant time effects on all examined environmental variables except MdΦ were revealed by PERMANOVA results (Table 2), indicating significant seasonal variations of these variables. However, PERMDISP analyses showed significant P-values of all these variables with significant differences except pH. In order to reveal seasonal variations of environmental variables, the analyses of variance were conducted at the two beaches separately. At both beaches, temperatures significantly differed among seasons (Table 3), and the pairwise tests showed that the differences of temperature between every two sampling months were significant (Bonferroni correction, P-level of 0.05/6 pairwise comparisons resulted in a P-level of 0.008). In addition, PERMANOVA and PERMDIST results showed that pH, DO and Chl-a concentration also significantly differed among seasons at XB sites, while salinity, DO and Chl-a concentration significantly differed among seasons at GB sites (Table 3). In addition, the pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences of pH, DO, and Chl-a between July and December at XB sites (Bonferroni correction, P < 0.008 and PERMDIST P > 0.05). At GB sites, salinity and DO differed significantly between July and December (Bonferroni correction, P < 0.008 and PERMDIST P > 0.05).

|

|

Table 2 Results of PERMANOVA and PERMDISP tests of environmental variables under two crossed, fixed factors: site (XB and GB) and time (April, July, October and December) |

|

|

Table 3 Results of PERMANOVA and PERMDISP tests performed on environmental variables of XB and GB separately |

The mean nematode abundance varied from 54.6 to 928.9 ind (10 cm2)−1 (Table 4). Annual mean nematode abundance was (597.8 ± 336.9) ind (10 cm2)−1 and (202.2 ± 327.7) ind (10 cm2)−1 at XB and GB respectively. PERMANOVA tests based on nematode abundance demonstrated a significant spatial variation, with higher nematode abundance at XB sites than that at GB sites (P < 0.01, Table 5). PERMDISP results showed a significant P value of nematode abundance, indicating that differences between beaches were mainly caused by differences in dispersion of data within beaches. A significant seasonal variation of nematode abundance was also proved by PERMANOVA results (Table 5). In addition, the pairwise comparison results revealed higher nematode abundance in April compared to those in December, July and October (Bonferroni correction, P < 0.008). According to PERMDISP results, nematode abundance showed a similar distribution in each sampling time. Significant interaction effects between sites and time were found for nematode abundance (P < 0.05).

|

|

Table 4 Mean values of nematode abundance (ind (10 cm2)−1), species and functional diversity indices at the study beaches |

|

|

Table 5 Results of PERMANOVA and PERMDISP tests performed on nematode datasets |

In general, species diversity indices (S, d, H', 1 − λ) were lower at GB than that at XB (Table 4). PERMANOVA results revealed significant differences of all these indices between two beaches, and no significant P-values for them were revealed by PERMDISP results, indicating homogeneity of the sample dispersion within beaches. S, d, H' and 1 − λ also differed significantly among sampling months (Table 5). No significant interaction effects between sites and time were found for these diversity indices. According to the analyses conducted separately, S, d, H' and 1 − λ appeared no significant seasonal difference at XB, while they were significantly higher in April than in December at GB (Bonferroni correction, P-level of 0.05/6 pairwise comparisons resulted in a P-level of 0.008).

3.3 Nematode Functional DiversityCompared to the values at XB sites, the functional diversity indices (FRic, FEve, FDis, RaoQ) were significantly higher at GB (Table 4), highlighting a significant site effect on these indices. However, the PERMDISP results showed a different distribution of FRic within beaches (P < 0.05, Table 5). A cautious interpretation of the significant differences in FRic may be caused by the within-group dispersion. No significant P-values of other functional indices were revealed by PERMDISP, indicating the significant differences were mainly due to the site effect. Although a significant time effect was observed in FDis and RaoQ, the PERMDISP results indicated the significant P-levels for these indices (Table 5). The further pairwise tests were performed breaking down the two beaches separately and showed that there were no significant time effects on functional diversity at both of these two beaches.

3.4 Relationships Between Nematode Diversity Indices and Environmental VariablesThe results of DistLM analyses revealed that environmental variables could explain the variations of nematode species diversity and functional diversity (Table 6). Among them, MdΦ was the most prominent variable which could best explain nematode abundance (38.0%), species diversity (S, d, J', H', 1 − λ), and functional diversity (FRic, FEve, FDis, and RaoQ) of the two study beaches (P < 0.01). In addition, sea water temperature, salinity, DO, pH, and sediment Chl-a concentration also exhibited correlations with nematode datasets. Among them, DO and pH were significantly related to S, d, or H' (P < 0.05). Salinity was involved in all functional diversity models, but exhibited different correlations (Table 6).

|

|

Table 6 Results of DistLM test for nematode features |

The further DistLM analyses were performed on nematode datasets breaking down the two beaches separately (Table 7). Environmental variables (i.e., OM, DO, MdΦ, temperature, and salinity) explained 61.7% of the observed variabilities of the nematode abundance at XB sites. Among these factors, OM and DO could explain 48.5% of the variability, significantly influencing the nematode abundance. Temperature was involved in nematode abundance, S, J', H', FDiv, FDis and RaoQ models, and was identified as a significant predictor of FDis and RaoQ. pH was identified as a significant predictor of J', explaining 29.4% of the observed variances. In addition, DO, MdΦ, and salinity were also involved in the species diversity indices models, but exhibited a weaker correlation. At the same time, MdΦ seemed to be a strong predictor of nematode functional diversity indices FEve, FDis, and RaoQ, explaining more than 15% of the observed variance. Salinity, DO, Chl-a were also strong predictors of FRic, FEve, and RaoQ, respectively (Table 7).

|

|

Table 7 Results of DistLM test for nematode features at the two beaches |

At GB sites, environmental variables worked together to produce an influence on nematode features (Table 7). Temperature was involved in nematode abundance, S, d, H', 1 − λ, FRic, FDis, and RaoQ models, and was identified as a significant predictor of S, H' and FDis. MdΦ was related to nematode abundance, species diversity indices (i.e., S, J', H', 1 − λ), functional diversity indices FRic and FDiv, and was a strong predictor of FDiv, explaining 50.6% of the observed variances. Salinity was also involved in most models, and significantly related to RaoQ. Although no significant correlation between OM and nematode parameters was observed, OM was included in most models of nematode species and functional diversity indices. In addition, pH, DO, and Chl-a were also responsible for the variations of different nematode indices in GB sites (Table 7).

3.5 Relationships Between Species Diversity Indices and Functional Diversity IndicesThe results of Pearson correlation analysis showed that FEev, FDis, and RaoQ significantly negatively correlated with S, d, H' and 1 − λ (Table 8). However, FRic, FEev, FDis, and RaoQ significantly positively correlated with J' (Table 8).

|

|

Table 8 Pearson correlation coefficients between species diversity indices (S, d, J', H', 1 − λ) and functional diversity indices (FRic, FEve, FDiv, FDis, RaoQ) |

Nematode abundance and diversity indices differed between two beaches and were strongly related with environmental variables in this study. The study beaches are located on different coasts of the Liaodong Peninsula and facing different seas, namely the Bohai Sea and the North Yellow Sea. It has been reported that hydrodynamic regime of the two seas differed with respect to waves, tides, coastal currents, etc (Xu, 2002; Su and Yuan, 2005; Song and Duan, 2019). For example, the current velocity in the North Yellow Sea is 1.5 – 2.5 m s−1 (Xu, 2002), while currents are generally weak with a maximum surface velocity of no more than 1.5 m s−1 in the Bohai Sea (Song and Duan, 2019). The particular hydrodynamic regime interacted with sediment particle size, leading to finer sediment particles at XB and coarser sands at GB. Furthermore, coarse and fine particle beaches will present different physical, chemical, and biological environments. According to the results of this study, the examined environmental variables differed significantly between the two beaches and the spatial variation between them was mainly due to sediment grain size (namely MdΦ), Chl-a concentration, pH, and salinity. The environmental characteristics of XB are fine granularity, higher Chl-a concentration, higher pH, and lower salinity.

The results of correlation analyses in the present study showed that the most distinguished differences in nematode abundance, species diversity indices (S, d, H', 1 − λ) and functional diversity indices (FRic, FEve, FDis, and RaoQ) between the two beaches were mainly caused by sediment grain size (MdΦ). The sediment grain size was considered to be an important physical factor on nematode spatial distribution and diversity (Giere, 2009; Hua et al., 2016a; Cai et al., 2020). It was generally believed that fine sands, with a particle size of 125 – 250 μm, were most conducive to the growth of microbenthos and meiobenthos (Fenchel, 1978). In this study, sediment MdΦ varied from 2.54 to 2.82 at XB sites, indicating high proportion of fine sands here. However, a high proportion of coarse sands, with a particle size of 500 – 2000 μm, was observed at most GB sites. Hua et al. (2016a) revealed that nematode abundance in temperate zone sandy beaches is highly correlated with sediment MdΦ, and sediments which is mainly composed of fine sand possess a higher nematode abundance compared to coarser sands. The results of this study were consistent with the findings of Hua et al. (2016a), revealing a significant higher nematode abundance in fine sands. Although nematode abundance tends to increase in fine sediments, diversity has been reported to be higher in coarser sediments (Heip et al., 1985; Vanaverbeke et al., 2011; Hua et al., 2016a). The increased microhabitat heterogeneity in coarser sediments can support more diverse communities (Heip et al., 1985; Gheskiere et al., 2005). However, several studies have highlighted the importance of sediment biogeochemistry, food availability and sediment oxygenation prevailing in sediments, rather than granulometry per se to structuring nematode communities (Vanaverbeke et al., 2011; Ingels et al., 2018). Our results indicate a higher nematode species diversity in finer sands compared to coarse sands, in favor of the idea that higher food availability in finer sediments allows for more diverse nematode assemblages. This was supported by a higher value of Chl-a concentration found in fine sand beach (XB) compared to coarse sand beach (GB) in this study. Ingels et al. (2018) also demonstrated that the nematode community in finer sediments was diverse in species because fine sediments were usually associated with greater concentrations of nutrients contained between the fine grains and may promote coexistence of nematode genera and species.

With respect to nematode functional diversity, it responded differently from species diversity to the variation of MdΦ. The results of Pearson correlation analyses proved a significant negative correlation between functional diversity indices (FEev, FDis, and RaoQ) with species diversity indices (S, d, and H') in the present study. To be specific, S, d, H' and 1 − λ of XB were significantly higher than those of GB, while FEve, FDis, and RaoQ were just the reverse. Functional diversity is the extent of functional differences among the species in a community. The functional diversity indices would show how the functionally defined assemblages varied spatially in response to environmental variables. FEve is the evenness of abundance distribution in filled niche space, FDis is the mean distance in multidimensional trait space of individual species to the centroid of all species, and RaoQ is the diversity and difference within and between the communities (Rao, 1982). Hence, the higher functional diversity, the better the taxa distributed in the traits space, indicating lower niche overlap and better resource utilization. In the present study, higher FEve, FDis and RaoQ were observed at sampling sites from GB, indicating better resource utilization at these sites with coarse sands. It can be proved by the dominance of nematodes with more specialist types of traits (namely epistrate feeders, predators, K-strategy nematodes), such as nematodes that belong to the genus Oncholaimus, Chromadorita, Enopolaimus, Enoplus, Dichromadora. On the other hand, more generalist types of traits (namely deposit feeders, r-strategy nematodes), such as species that belong to the genuses Daptonema, Sabatieria, Setosabatieria, Bathylaimus, dominated at XB sites with fine sand sediments. The increasing interspecific competition for less abundant resources and spaces resulted in a high niche overlap, and was responsible for the low functional diversity at these XB sites. According to the idea that microhabitat heterogeneity increased in coarser sediments, coarse-grained sandy beach has more gaps and can provide more space, which allows for more diverse nematodes (Gheskiere et al., 2005). Results of the present study deemed that, to be precise, marine nematodes in coarse-grained sandy beaches may have higher functional diversity rather than species diversity.

It is undeniable that other environmental variables, such as temperature, pH, DO, and salinity, were also related to nematode abundance, species diversity indices and functional diversity indices to a certain extent in this study. Among them, pH and salinity differed significantly between the study beaches, which might be another possible reason for the spatial variation in nematode communities. However, the variations of pH (the mean value of 8.1 vs. 7.9) and salinity (the mean value of 30.4 vs. 31.5) were under an appropriate range of fluctuation, which was unlikely to bring notable effects on structuring nematode communities. Moreover, available knowledge suggested that nematodes remain unaffected, or even increased in abundance or diversity when lowering the pH to 7.5 or lower (Ingels et al., 2018; Hua et al., 2019). We therefore suggested that these environmental variables were not the main factors causing spatial variations of nematode communities between the two study beaches.

4.2 Responses of Nematode Diversity to the Environmental Seasonal VariationIn the present study, significant seasonal differences of temperature, Chl-a concentration, DO content, and pH were observed at both of the sampling beaches. According to the results, temperature, pH, DO content and Chl-a concentration significantly differed among seasons at XB sites, while temperature, salinity, DO content and Chl-a concentration significantly differed among seasons at GB sites. Correspondingly, nematode abundance and diversity indices (S, d, H', 1 − λ) showed significant seasonal variation at both beaches, and were strongly related with the environmental variables.

Previous studies have demonstrated that temperature was one of the main factors that control the structure of meiofauna communities on the beach by promoting meiofauna reproduction (Rieta, 2011), or affecting the growth and availability of their food resources, such as bacteria and diatoms (Harris, 1972). In the present study, nematode abundance, S, d, H', 1 − λ were observed extraordinarily higher in April than those in December at both beaches, especially at sites of GB. The increasing temperature can promote breeding of marine nematodes (Harris, 1972), and nematode abundance will increase in spring as a result (Nicholas, 2001). At the same time, the appropriate temperature in spring is also conducive to the growth and reproduction of benthic microalgae, which can affect the habitat of nematode because of the trophic value of the microalgae (Armonies and Reise, 2000). Chl-a is commonly used to denote the number of live microalgae reaching the sea floor. Nematodes often appeared abundant and diverse in sediments with high Chl-a concentration (Hua et al., 2021). In the present study, Chl-a concentration exhibited a significant seasonal variation at both beaches, while a relatively high value was observed in April and a significant low value was observed in December. Therefore, nematodes abundance, S, d, H', and 1 − λ increased dramatically in spring, but decreased to the lowest in winter.

At the same time, other environmental variables, such as DO, pH, salinity, etc. were also correlated with nematode abundance, S, d, H', and 1 − λ. With the increasing temperature, bacteria proliferation was promoted and oxygen consumption increased. With decreasing DO content, nematode abundance and diversity might decline (Hua et al., 2012). However, the DO content at most sampling sites were quite high all the year round, and low values of DO content were occasionally observed at low tidal sites in July which likely limited the nematode abundance and diversity in this study. The water acidity, recorded in pH-units, correlated with DO content. Abnormal level of pH together with other stress factors, such as extreme temperatures, anoxic, and salinity, can be detrimental (Giere, 2009). A slight alkalinity of seawater (pH 7.5 – 8.5) was recorded at both study beaches. However, a slight fluctuation of water acidity related with DO content was observed in summertime, which was likely to limit the nematode abundance and diversity in this study. Several studies demonstrated that the abundance of meiofauna, including marine nematode, was closely related to seasonal rainfall and salinity (Baia et al., 2021). In the present study, salinity was related to nematode abundance, species diversity and functional diversity indices at both study beaches. The annual mean precipitation is 550 – 950 mm and the majority of rainfall (approximately 60% – 70%) occurs during summer in Dalian (Jin, 2021). Salinity decreases with the increasing precipitation and is strongly related to seasonal fluctuation of temperature at study beaches. Therefore, low level of nematode abundance, S, d, H', and 1 − λ in July might be the ultimate responses to the temperature-related factors, such as DO content, water acidity, and salinity. In addition, the study beaches are popular visiting places for tourists and a large number of tourists visit them in summer. Trampling on the beaches would increase the density of sand and compressed space, which adversely affected marine nematodes in the sediments. Several studies have revealed that human trampling caused a decrease in the abundance and diversity of marine nematodes (Santos et al., 2021). Therefore, anthropogenic disturbance might have a strong influence on seasonal variations in nematode abundance and diversity.

Unexpectedly, functional diversity indices did not vary significantly among sampling months. Although these functional diversity indices were still correlated with seasonal variation of environmental variables to a certain extent, they might not be as sensitive as species diversity to seasonal fluctuation of these environmental variables.

4.3 Internal Connection Between Species Diversity and Functional DiversityMany studies deemed that there was a direct internal connection between species diversity and functional diversity. Schratzberger et al. (2007) demonstrated that there was a strong relationship between the number of species or genera and functional features, that was, under a constant set of environmental conditions, an increase in the number of species should lead to an increase in functional diversity. Zhong et al. (2020) studied macrofauna and revealed that high values of functional diversity mainly occurred with high species diversity, uniform trait distribution and small niche overlap. The study conducted by Kasia et al. (2021) revealed a strong positive correlation between nematode functional richness and species diversity metrics (species richness, Simpson and Shannon diversity). However, functional diversity indices (FRic, FEve, FDis, RaoQ) negatively correlated with species diversity indices S, d, H', and 1 − λ in the present study. In fact, several other studies did not find a consistent pattern of internal connection between species and functional diversity either (Leduc et al., 2013; Baldrighi and Manini, 2015). It has been inferred that the inconsistent pattern of internal connection between species and functional diversity may depend partly on community assembly (Hooper et al., 2005). According to the concepts of niche differentiation and limiting similarity, functional traits of coexisting organisms differ at a certain level, which means that increasing species richness should lead to an increasing functional diversity (Hooper et al., 2005). However, strong environmental filters could limit species composition to a relatively restricted range of functional traits, thereby limiting the degree of functional diversity (Hooper et al., 2005; Petchey and Goston, 2006). In this case, increasing species richness would just lead to a finer division of the available niche space rather than a greater functional diversity. Therefore, the studies investigating the internal connection between species diversity and functional diversity revealed different results under different circumstances. Furthermore, the limited number of nematode functional traits were involved in calculating functional diversity indices in these studies, which might influence the pattern of internal connections. In fact, a range of biological traits of nematodes, including morphological, physiological or behavioral features, are thought to be related to important ecological functions (Schratzberger et al., 2007). The more functional traits performed, the better the internal connections described. Kasia et al. (2021) once concluded that for predicting species diversity, several functional traits being considered at the same time can get a better result than each trait being applied alone. We believe that it will improve the future study of the internal connections of species diversity and functional diversity, if more biological traits are involved in calculating functional diversity indices.

Here, we would like to pay more attention to the signals provided by the species and functional diversity indices. Species diversity is often characterized by various indices, reflecting the abundance and uniformity of biological communities. It is sensitive to environmental changes, and is widely recommended as a useful indicator for environmental quality assessments (Semprucci et al., 2014; Bianchelli et al., 2018). The Functional diversity, based on the functional traits of different groups, can describe the changes of traits values within a community, and can be regarded as an early warning signals of disturbance (Mulder et al., 2012; Mouillot et al., 2013). In particular, functional diversity is assumed to be a better predictor of ecosystem functioning than classical species diversity (Gagic et al., 2015) because competitive interactions and responses to habitat filtering reflect, at least partly, functional traits (Mouillot et al., 2013). An opposite pattern between nematode species and functional diversity to the environmental variations was observed in the present study. At XB, higher species richness and H', but lower functional diversity (FRic, FEve, FDis, and RaoQ) represented higher functional redundancy. Functional redundancy also could be measured by the ratio RaoQ/H'. when the ratio increased, functional redundancy decreased and vice versa (Linden et al., 2012). Higher functional redundancy indicated relatively similar nematode functional traits and overlapped niches. To be specific, the results indicated that many species may have similar or even the same features and ecological functions in the community. Disappearance or replacement of one species (for example, species with similar or identical ecological functions) was unlikely to cause changes in ecosystem functions. Therefore, the beach ecosystem at XB was stable with high resistance to environmental changes. On the contrary, higher RaoQ but lower H' at GB sites meant lower functional redundancy, representing an ecosystem with fewer species but lower niche overlap. Disappearance or replacement of any species will change the ecosystem stability. Though species and functional diversities of sandy intertidal nematodes revealed inconsistent response to environmental changes, the warning signals of ecosystem stability provided by these indices were complementary. Therefore, the application of both functional diversity and species diversity was demonstrated to effectively reflect ecosystem stability instead of using only one type of biologi-cal indicators.

5 ConclusionsA significant inter-beaches variability of nematode species diversity indices and functional diversity indices was observed in this study. This variability reflected the observed spatial variations mainly in sediment MdΦ. Nematodes in fine-grained sediments had higher species diversity, while nematodes in coarse-grained sandy beaches had higher functional diversity. The higher H' but lower RaoQ in finer sediment indicated a nematode community being more resistant to environmental changes and a more stable ecosystem, while the coarse sands nematode community was on the contrary. In terms of seasonal differences, nematode abundance and the species diversity indices (S, d, H', 1 − λ) fluctuated with variations of temperature, Chl-a, DO, pH, and salinity within the study beaches. However, functional diversity indices did not show significant seasonal variations and exhibited weak correlation with the studied environmental variables. Functional diversity indices appeared not to be as sensitive as species diversity to seasonal fluctuation of temperature, Chl-a, DO, pH, and salinity. Overall, the present study showed how species and functional diversity indices change across environmental conditions and how environmental variables likely affect the indices. A decrease in the number of species in coarse sands, accompanied by an increase in functional diversity, can be regarded as an early warning signal of disturbance. Although negative correlations between species diversity and functional diversity indices were revealed, the warning signals of ecosystem stability provided by the indices were complementary. At the same time, if more biological traits are involved in calculating functional diversity indices, it will be helpful for the future study of the internal connections of species diversity and functional diversity.

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41976100, 41576153). We would like to thank all the members of the Laboratory of Biological Oceanography and Benthic Ecology in Ocean University of China for their assistance and support in the field sampling and laboratory processing activities.

Anderson, M. J., Gorley, R. N., and Clarke, K. R., 2008. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods. Plymouth, UK, 214pp.

(  0) 0) |

Appeltans, W., Ahyong, S. T., Anderson, G., Angel, M. V., Artois, T., Bailly, N., et al., 2012. The magnitude of global marine species diversity. Current Biology, 22: 2189-2202. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.036 (  0) 0) |

Armonies, W., and Reise, K., 2000. Faunal diversity across a sandyshore. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 196: 49-57. DOI:10.3354/meps196049 (  0) 0) |

Baia, E., Rollnic, M., and Venekey, V., 2021. Seasonality of pluviosity and saline intrusion drive meiofauna and nematodes on an Amazon freshwater-oligohaline beach. Journal of Sea Research, 170: 102022. DOI:10.1016/j.seares.2021.102022 (  0) 0) |

Baldrighi, E., and Manini, E., 2015. Deep-sea meiofauna and macrofauna diversity and functional diversity: Are they related?. Marine Biodiversity, 45(3): 469-488. DOI:10.1007/s12526-015-0333-9 (  0) 0) |

Bezerra, T. N., Eisendle, U., Hodda, M., Holovachov, O., Leduc, D., Mokievsky, V., et al., 2021. Nemys: World Database of Nematodes. Accessed at http://nemys.ugent.be on 2021-09-27, DOI: 10.14284/366.

(  0) 0) |

Bianchelli, S., Buschi, E., Danovaro, R., and Pusceddu, A., 2018. Nematode biodiversity and benthic trophic state are simple tools for the assessment of the environmental quality in coastal marine ecosystems. Ecological Indicators, 95(1): 270-287. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.07.032 (  0) 0) |

Bongers, T., Alkemade, R., and Yeates, G. W., 1991. Interpretation of disturbance induced maturity decrease in marine nematode assemblages by means of the maturity index. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 76: 135-142. DOI:10.3354/meps076135 (  0) 0) |

Bongers, T., and Bongers, M., 1998. Functional diversity of nematodes. Applied Soil Ecology, 10: 239-251. DOI:10.1016/S0929-1393(98)00123-1 (  0) 0) |

Bongers, T., de Goede, R. G. M., Korthals, G. W., and Yeates, G. W., 1995. Proposed changes of c-p classification for nematodes. Russian Journal of Nematology, 3: 61-62. (  0) 0) |

Bremner, J., Rogers, S. I., and Frid, C. L. J., 2003. Assessing functional diversity in marine benthic ecosystems: A comparison of approaches. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 254: 11-25. DOI:10.3354/meps254011 (  0) 0) |

Cai, L. Z., Fu, S. J., Zhou, X. P., Tseng, L. C., and Hwang, J. S., 2020. Benthic meiofauna with emphasis on nematode assemblage response to environmental variation in the intertidal zone of the Danshuei River estuary, northwest Taiwan. Ecological Research, 35(5): 857-870. DOI:10.1111/1440-1703.12159 (  0) 0) |

Clarke, K. R., and Gorley, R. N., 2015. PRIMER v7: User Manual/Tutorial (Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research). PRIMER-E, Plymouth, 296pp.

(  0) 0) |

Danovaro, R., 2010. Methods for the Study of Deep-Sea Sediments Their Functioning and Biodiversity. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 458.

(  0) 0) |

Fenchel, T. M., 1978. The ecology of micro- and meiobenthos. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 9: 99-121. DOI:10.1146/annurev.es.09.110178.000531 (  0) 0) |

Friberg, N., Bonada, N., Bradley, D. C., Dunbar, M. J., Edwards, F. K., Grey, J., et al., 2011. Biomonitoring of human impacts in freshwater ecosystems: The good, the bad and the ugly. Advances in Ecological Research, 44: 1-68. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-374794-5.00001-8 (  0) 0) |

Gagic, V., Bartomeus, I., Jonsson, T., Taylor, A., Winqvist, C., Fischer, C., et al., 2015. Functional identity and diversity of animals predict ecosystem functioning better than species-based indices. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences, 282: 1-8. (  0) 0) |

Gheskiere, T., Vincx, M., Urban-Malinga, B., Rossano, C., Scapini, F., and Degraer, S., 2005. Nematodes from wave-dominated sandy beaches: Diversity, zonation patterns and testing of the isocommunities concept. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 62: 365-375. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2004.09.024 (  0) 0) |

Giere, O., 2009. Meiobenthology: The Microscopic Motile Fauna of Aquatic Sediments. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 538.

(  0) 0) |

Grzelak, K., Gluchowska, M., Gregorczyk, K., Winogradow, A., and Weslawski, J. M., 2016. Nematode biomass and morphometric attributes as biological indicators of local environmental conditions in arctic fjords. Ecological Indicators, 69: 368-380. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.04.036 (  0) 0) |

Harris, R. P., 1972. The distribution and ecology of the interstitial meiofauna of a sandy beach at Whitsand Bay, East Cornwall. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 52(1): 1-18. DOI:10.1017/S0025315400018531 (  0) 0) |

Heip, C., Vinx, M., and Vranken, G., 1985. The ecology of marine nematodes. Oceanography and Marine Biology, 23: 399-489. (  0) 0) |

Hooper, D. U., Chapin, F. S., Ewel, J. J., Hector, A., Inchausti, P., Lavorel, S., et al., 2005. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: A consensus of current knowledge. Ecological Monographs, 75: 3-35. DOI:10.1890/04-0922 (  0) 0) |

Hua, E., Li, J., Dong, J., Xu, F. F., and Zhang, Z. N., 2012. Responses of sandy beach nematodes to oxygen deficiency: Microcosm experiments. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 32(13): 3975-3986 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.5846/stxb201106080765 (  0) 0) |

Hua, E., Mu, F. H., Zhang, Z. N., Yang, S. C., Zhang, T., and Li, J., 2016a. Nematode community structure and diversity pattern in sandy beaches of Qingdao, China. Journal of Ocean University of China, 15: 33-40. DOI:10.1007/s11802-016-2686-5 (  0) 0) |

Hua, E., Sun, Y. T., Zhang, Z. N., He, L., Cui, C. Y., and Mu, F. H., 2019. Effects of reduced seawater pH on nematode community composition and diversity in sandy sediments. Marine Environmental Research, 150: 104773. DOI:10.1016/j.maren-vres.2019.104773 (  0) 0) |

Hua, E., Zhang, Z. N., Zhou, H., Mu, F. H., Li, J., Zhang, T., et al., 2016b. Meiofauna distribution in intertidal sandy beaches along China shoreline (18˚ – 40˚N). Journal of Ocean University of China, 15(1): 19-27. DOI:10.1007/s11802-016-2740-3 (  0) 0) |

Hua, E., Zhu, Y. M., Huang, D. M., and Liu, X. S., 2021. Are free-living nematodes effective environmental quality indicators? Insights from Bohai Bay, China. Ecological Indicators, 127: 107756. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107756 (  0) 0) |

Ingels, J., dos Santos, G., Hicks, N., Vazquez, Y. V., Neres, P. F., Pontes, L. P., et al., 2018. Short-term CO2 exposure and temperature rise effects on metazoan meiofauna and free-living nematodes in sandy and muddy sediments: Results from aflume experiment. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 502: 211-226. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2017.07.012 (  0) 0) |

Jin, Z. X., 2021. Analysis of Dalian City climate change in recent 50 years. Territory and Natural Resources Study, 4: 16-21 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Kasia, S., Paula, C., Soraia, V., and Helena, A., 2021. What makes a better indicator? Taxonomic vs functional response of nematodes to estuarine gradient. Ecological Indicators, 121: 107113. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107113 (  0) 0) |

Leduc, D., Rowden, A. A., Pilditch, C. A., Maas, E. W., and Probert, P. K., 2013. Is there a link between deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystem function?. Marine Ecology, 34(3): 334-344. DOI:10.1111/maec.12019 (  0) 0) |

Liao, J. X., Wei, C. L., and Yasuhara, M., 2020. Species and functional diversity of deep-sea nematodes in a high energy submarine canyon. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7: 591. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2020.00591 (  0) 0) |

Linden, P. V. D., Patrício, J., Marchini, A., Cid, N., Neto, J. M., and Marques, J. C., 2012. A biological trait approach to assess the functional composition of subtidal benthic communities in an estuarine ecosystem. Ecological Indicators, 20: 121-133. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.02.004 (  0) 0) |

Liu, C. L., Zhu, Z. G., He, X. L., Zhang, B., and Ning, X., 2007. Rapid determination of organic carbon in marine sediment samples by potassium dichromate oxidation ferrous sulphate titrimetry. Rock and Mineral Analysis, 26(3): 205-208 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0254-5357.2007.03.008 (  0) 0) |

Liu, H., Wu, Y. P., Gao, S. D., and Zhang, Z. N., 1998. The variations of chlorophyll-a and phaeophytin in the sediment of Jimo shrimp pond before the outbreak of shrimp disease. Transactions of Oceanology and Limnology, 1: 65-69. (  0) 0) |

Liu, X. S., Liu, Q. H., Zhang, Y., Hua, E., and Zhang, Z. N., 2018. Effects of Yellow Sea Cold Water Mass on marine nematodes based on biological trait analysis. Marine Environmental Research, 141: 167-185. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2018.08.013 (  0) 0) |

Lorenzen, C. J., and Jeffrey, S. W., 1980. Determination of chlorophyll in seawater. UNESCO Technical Papers in Marine Science, 35(1): 1-12. (  0) 0) |

Lv, Y., Zhang, W. D., Gao, Y., Ning, S. X., and Yang, B., 2011. Preliminary study on responses of marine nematode community to crude oil contamination in intertidal zone of Bathing Beach, Dalian. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 62(12): 2700-2706. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.09.018 (  0) 0) |

Materatski, P., Ribeiro, R., Moreira-Santos, M., Sousa, J. P., and Adão, H., 2018. Nematode biomass and morphometric attributes as descriptors during a major Zostera noltii collapse. Marine Biology, 165(2): 1-17. DOI:10.1007/s00227-018-3283-5 (  0) 0) |

McLachlan, A., and Brown, A. C., 2006. The Ecology of Sandy Shores. Academic Press, Burlington, 392. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-372569-1.X5000-9

(  0) 0) |

Mouillot, D., Graham, N. A. J., Villéger, S., Mason, N. W. H., and Bellwood, D. R., 2013. A functional approach reveals community responsesto disturbances. Trendsin Ecology and Evolution, 28: 167-177. DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.004 (  0) 0) |

Mulder, C., Boit, A., Mori, S., Vonk, J. A., Dyer, S. D., Faggiano, L., et al., 2012. Distributional (in)congruence of biodiversityecosystem functioning. Advances in Ecological Research, 48: 1-88. (  0) 0) |

National Marine Data and Information Service, 2015. Tide Tables. Maritime Press, Beijing, 536 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Nicholas, W. L., 2001. Seasonal variations in nematode assemblages on an Australian temperate ocean beach; the effect of heavy seas and unusually high tides. Hydrobiologia, 464(1/3): 17-26. DOI:10.1023/A:1013985732009 (  0) 0) |

Petchey, O. L., and Gaston, K. J., 2002. Functional diversity (FD), species richness and community composition. Ecology Letters, 5(3): 402-411. DOI:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00339.x (  0) 0) |

Petchey, O. L., and Gaston, K. J., 2006. Functional diversity: Back to basics and looking forward. Ecology Letters, 9(6): 741-758. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00924.x (  0) 0) |

Platt, H. M., and Warwick, R. M., 1983. Free-Living Marine Nematodes. Part I British Enoplids. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 307.

(  0) 0) |

Platt, H. M., and Warwick, R. M., 1988. Free-Living Marine Nematodes. Part II British Chromadorids. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 502.

(  0) 0) |

Rao, C. R., 1982. Diversity and dissimilarity coefficients: A unified approach. Theoretical Population Biology, 21(1): 24-43. DOI:10.1016/0040-5809(82)90004-1 (  0) 0) |

Riera, R., Núez, J., Brito, M. D. C., and Tuya, F., 2011. Seasonal variability of a subtropical intertidal meiofaunal assemblage: Contrasting effects at the species and assemblage-level. Vie et Milieu – Life and Environment, 61(3): 129-137. (  0) 0) |

Santos, T. M. T., Petracco, M., and Venekey, V., 2021. Recreational activities trigger changes in meiofauna and free-living nematodes on Amazonian macrotidal sandy beaches. Marine Environmental Research, 167: 105289. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2021.105289 (  0) 0) |

Schlacher, T. A., Schoeman, D. S., Dugan, J., Lastra, M., Jones, A., Scapini, F., et al., 2008. Sandy beach ecosystems: Key features, sampling issues, management challenges and climate change impacts. Marine Ecology, 29: 70-90. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0485.2007.00204.x (  0) 0) |

Schratzberger, M., Warr, K., and Rogers, S. I., 2007. Functional diversity of nematode communities in the southwestern North Sea. Marine Environmental Research, 63(4): 368-389. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2006.10.006 (  0) 0) |

Semprucci, F., Balsamo, M., and Frontalini, F., 2014. The nematode assemblage of a coastal lagoon (Lake Varano, southern Italy): Ecology and biodiversity patterns. Scientia Marina, 78: 579-588. DOI:10.3989/scimar.04018.02A (  0) 0) |

Sheaves, M., 2006. Scale-dependent variation in composition of fish fauna among sandy tropical estuarine embayments. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 310: 173-184. DOI:10.3354/meps310173 (  0) 0) |

Song, H. L., Mu, F. H., Sun, Y., and Hua, E., 2021. Comparison of community structure and diversity of free-living marine nematodes in the sandy intertidal zone of Dalian in winter. Haiyang Xuebao, 43(8): 139-151 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.12284/hyxb2021060 (  0) 0) |

Song, J. M., and Duan, L. Q., 2019. The Bohai Sea. In: World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation. Volume II: The Indian Ocean to the Pacific. Sheppard, C., ed., Academic Press, United Kingdom, 377-394, DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-08-100853-9.00024-5.

(  0) 0) |

Su, J. L., and Yuan, Y. L., 2005. Hydrology in China Offshore. Ocean Press, Beijing, 367 (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Sun, X. Y., Zhou, H., Hua, E., Xu, S. H., Cong, B. Q., and Zhang, Z. N., 2014. Meiofauna and its sedimentary environment as an integrated indication of anthropogenic disturbance to sandy beach ecosystems. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 88: 260-267. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.08.033 (  0) 0) |

Vanaverbeke, J., Merckx, B., Degraer, S., and Vincx, M., 2011. Sediment-related distribution patterns of nematodes and macrofauna: Two sides of the benthic coin?. Marine Environmental Research, 71: 31-40. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2010.09.006 |

Villéger, S., Mason, N. W. H., and Mouillot, D., 2008. New multidimensional functional diversity indices for a multifaceted framework in functional ecology. Ecology, 89: 2290-2301. DOI:10.1890/07-1206.1 (  0) 0) |

Warwick, R. M., Platt, H. M., and Somerfield, P. J., 1998. Free-Living Marine Nematodes. Part III British Monhysterids. The Linnean Society of London and the Estuarine and Coastal Sciences Association, London, 296.

(  0) 0) |

Wieser, W., 1953. Die Beziehung zwischen Mundhohlengestalt, Ernahrungsweise und Vorkommen bei freilebenden marinen Nematoden. Eine skologisen-morphologische studie. Arkiv fiir Zoologie, 4: 439-484. (  0) 0) |

Wright, L., and Short, A., 1983. Morphodynamics of beaches and surf zones in Australia. In: Handbook of Coastal Processes and Erosion. Komar, P. D., ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, 35-64.

(  0) 0) |

Xu, F. X., 2002. Lectures on ocean wave forecast part 5: Geographical distribution and seasonal variation of ocean waves. Marine Forecasts, 19(2): 74-79 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-0239.2002.02.012 (  0) 0) |

Xu, M., Liu, Q. H., Zhang, Z. N., and Liu, X. S., 2016. Response of free-living marine nematodes to the southern Yellow Sea Cold Water Mass. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 105(1): 58-64. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.02.067 (  0) 0) |

Zhong, X., Qiu, B. C., and Liu, X. S., 2020. Functional diversity patterns of macrofauna in the adjacent waters of the Yangtze River Estuary. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 154: 111032. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111032 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22