2) Key Laboratory of Marine Ecological Monitoring and Restoration Technologies, Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR), Shanghai 201206, China;

3) East China Sea Forecast and Disaster Reduction Center of the Ministry of Natural Resources, Shanghai 200136, China

Dissolved oxygen (DO) in seawater is one of the essential environmental elements for the survival and reproduction of marine organisms and is closely associated with the structure and function of the ecosystem (Hietanen et al., 2012; Rabalais et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2017). Hypoxia is generally defined as an aquatic DO concentration of less than 2 mg L−1 (Diaz and Rosenberg, 1995) and has been widely observed in various estuarine and coastal regions during the last few decades. Changes in the redox environment of the water body due to the nearshore hypoxia zones might also affect the material circulation and biogeochemical processes, resulting in the activation of heavy metals, causing multiple ecological and environmental problems (Turner et al., 2008; Bianchi and Allison, 2009), reducing biodiversity, and changing the structure of ecological communities (Rabalais and Turner, 2001). Hypoxia in the Chang-jiang Estuary (CE) is seasonal; and hypoxic events occur in the wet seasons with massive runoffs. Hypoxia zones often occur in the area between the CE and approximately 50 m of the inner continental shelf.

The mechanism of hypoxia in the CE, which is the result of the interaction of physical-chemical-biological factors, is quite complex. Hypoxia is mainly controlled by the stratification of water and the decomposition of organic matter (Li et al., 2002; Wei et al., 2007; Wang, 2009; Li et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015). Furthermore, the rise in nutrient input by rivers stimulated the increase in the intensity and area of the hypoxic phenomenon (Zhang et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2017). In recent years, some studies have explored the influence of some physical factors on the development of this phenomenon, such as the south water mass intrusion (Wang, 2009; Wei et al., 2015; Qian et al., 2017), upwelling (Wei et al., 2017a), wind (Ni et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017), and topography below the ocean (Wang, 2009; Wei et al., 2015). Water mass conditions and the physical topography of the CE are the main contributors to the development of hypoxia, whereas human activities (Zhang et al., 2010) are supporting factors.

Many scholars have studied the formation mechanism of hypoxia in the CE and its adjacent waters. Particularly, the bottom hypoxic water mass in the southern segment of the CE in summer was from the nearshore Kuroshio branch current, which was mixed with the subsurface water of the South China Sea via the Luzon Strait, invading the East China Sea at the northeastern corner of Taiwan, and finally reaching the offshore area of CE via the East China Sea shelf basin (Qian et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2021). The water mass is characterized by low temperature (< 19℃), high salinity (> 34.4), and low DO. After entering the East China Sea, the long-distance transport process on the nearshore shelf of the East China Sea further consumed the DO of bottom water, making it on the verge of hypoxia when arriving at the waters adjacent to the CE. Finally, a large area of hypoxia zone was developed because of the further DO consumption by the decomposition of organic matter in summer (Chi et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2017b, 2021).

The water mass in the CE of the hypoxic area is dominated by the East China Sea shelf water (ECSSW) (Chi et al., 2017), with the temperature and salinity between the Changjiang Diluted Water (CDW) and Kuroshio subsurface water (KSW), and with a long bottom water residence time of approximately ten days. Simultaneously, the ECSSW formed a stabilized seawater pycnocline together with the surface fresh water. Consequently, exchanges between water bodies are restricted, leading to the formation of a hypoxic area (Chi et al., 2017). Liu et al. (2018) suggested that the hypoxic area in the CE was also affected by sea currents from the junction of the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea in the northern segment.

However, most of the current researches involved the hypoxic cases that occurred in a certain year; on the whole, the changes of locations and interactions among different water masses during the hypoxic periods cannot be found. Therefore, the changes of different water masses affecting the locations and intensities of various hypoxia zones should be further investigated according to the continuous survey data. Fortunately, the researchers collected consecutive temperature, salinity, and DO data in the CE for six years. Based on the survey data of the hypoxic area, this study analyzed the structure of water masses in the hypoxic area of the CE and discussed their impact on the formation of hypoxia in a long-term series. The results provide the basis for the understanding of formation mechanism and early warning of the hypoxic occurrence in the CE.

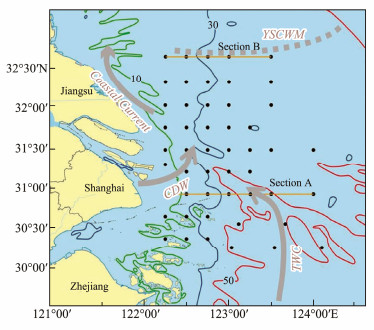

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Study AreaThe study area (Fig.1) ranges from 123.0° to 123.5°E in longitude and from 30.5° to 32.5°N in latitude. A steep slope to the east of the 30-m isobath and a shoal area to the west are generally observed; this slope has the characteristics of a submarine canyon, extending from southeast to northwest. Regarding the hydrodynamics, the CDW, ECSSW, Tsugaru Warm Current (TWC) or KSW, Yellow Sea cold water mass (YSCWM), and the coastal current are the main components affecting the current system in the study area (Qi et al., 2017). The Changjiang River delivers large fresh-water with abundant nutrients and the low-density CDW floats over the saline oceanic seawater, forming a river plume front during summer. The influence scope of the CDW is within the 31 isohaline, and the 26 isohaline is defined as the salinity of the CDW core area (Mao et al., 1963; Le, 1984). The KSW is primarily originated from the bottom TWC as a Kuroshio branch (Qi et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018), and the temperature and salinity of the deep water of the TWC range from 17℃ to 23℃ and 34.2℃ to 34.7℃, respectively (Weng and Wang, 1989). The YSCWM comes from the bottom water of the Yellow Sea of China, and its distinguishing feature is its low core temperature (4.6℃–9.3℃); however, its temperature is generally below 20℃ at the junction with the CDW (Zhu et al., 1998; Li and Su, 1999). The mixing between the large runoff and saline sea-water forms the ECSSW in the CE. The coastal current flowing northward was steadily affected by the southwest summer monsoon. Many water masses engage in complex interactions and exchanges in the CE, but different water masses with unique temperatures or salinity are easily identified.

|

Fig. 1 Sampling sites in the study area off the CE and its adjacent waters. |

Hydrological and chemical parameters in August 2011 and from 2013 to 2017, including temperature, salinity, and DO concentration, were obtained by using the SBE25 CTD (conductivity-temperature-depth) (No. 0393) at 50 stations (Fig.1). The DO concentration was obtained in accordance with the water-quality determination of the DO optical sensor method (ISO 17289-2014). Water samples were analyzed at the depth interval of 1 m, from 1 m to the bottom.

Every field investigation generally lasted 3 – 4 weeks and an unexpected typhoon may occasionally interrupt the survey. The duration of most hypoxia zones in the CE was short because of some short-term change factors (Zhang et al., 2018). Data collection was incomplete because of the impact of the typhoon in 2012; thus, hypoxic areas could not be fully captured owing to the restriction in the position of the monitoring stations. The specific dates of the year, month, and day during the field survey are recorded to determine the changes in hypoxia events accurately (2011: 8/17 – 9/13; 2013: 8/4 – 9/6; 2014: 8/7 – 8/29; 2015: 8/14 – 9/12; 2016: 8/16 – 9/9; 2017: 8/3 – 8/25).

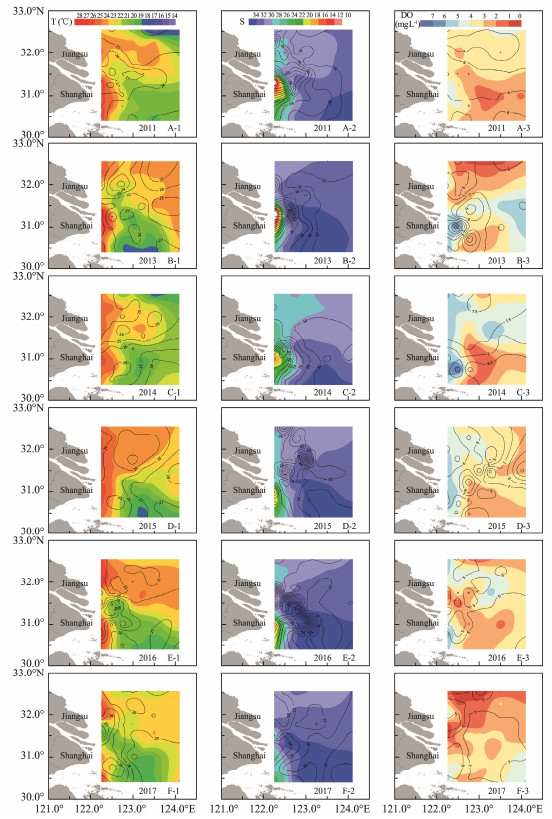

3 Results 3.1 Horizontal Distribution of Temperature, Salinity, and DOAccording to the horizontal distribution of temperature, salinity, and DO in 2011 and 2013 – 2017 (Fig.2), the distribution characteristics of thermohaline and hypoxia zones were similar in 2011 and 2014 and in 2013 and 2017. The hypoxic area was distributed in the southern region of the CE in 2011 and 2014, whereas in the northern region in 2013 and 2017.

|

Fig. 2 Horizontal distribution maps of temperature, salinity, and DO with isolines for the surface water and color maps for the bottom layer. A-1 – F-1 for temperature, A-2 – F-2 for salinity, and A-3 – F-3 for DO. |

The letters represent years in Fig.2; A denotes 2011 and B to F for each year from 2013 to 2017; -1 stands for temperature, -2 for salinity, and -3 for DO. The surface and bottom range of temperature, salinity, and DO are shown in Table 1.

|

|

Table 1 Hydrological and chemical parameters in the monitored area |

In 2011, a high-temperature water input, which was evident in the southern branch of CE, was found at the nearbottom waters in the nearshore area. This input was invaded northward by the TWC in the eastern part of 122.5°E, which was close to 31.5°N. Therefore, the gradient of the bottom water temperature in the southern region was observed from the coastal to the offshore areas. The YSCWM (< 19℃) was also found in the northern part of the study area. The salinity gradually increased from the coastal to the offshore areas. The CDW tongue turned to the northeast from the Yangtze Estuary, and the effect of CDW was observed. Simultaneously, TWC invasion was not seriously identified in the near-bottom waters in the southern sea area, mainly located in the east of 123°E and south of 31.0° N. Hypoxia appeared in the bottom layer and was distributed in the southern part of the study area. In 2014, two high-temperature tongues of the CDW in bottom waters were more evident than that in 2011, and the direction was in line with the outflowing CDW in estuaries. Low-temperature water (< 22℃) was found in most southeast areas. The water mass affected by the YSCWM (< 19℃) appeared (Zhu et al., 1998) similar to that in 2011. The surface salinity distribution showed that the intensity of the CDW is weaker than that in 2011, and the bottom high-salt water (salinity > 34) northward invasion was weak, reaching approximately 31.0°N. The hypoxic phenomenon occurred at the bottom layer between 122.5° – 123.5°E and 30.5° – 31.5°N.

In 2013, 2016, and 2017, the distributions of hypoxia zones were independent in the northern and southern areas of the Yangtze River Estuary. In 2013, the KSW (< 19℃), appeared in the southern part of the bottom water. The high-salinity water (> 34) invaded northward to 31.5°N, and the hypoxia area was distributed in the bottom water (122.5°– 124°E; 32.0°– 32.5°N). In 2016, high saline water, larger than 34 at the bottom, with a low temperature of 22℃, invaded from southeast to northwest until 122.5°E and 31.5°N. Most of the bottom waters was mild hypoxia (DO < 3 mg L−1), and hypoxia was sporadically distributed in the northern, central, and southern regions of the study area. In 2017, the invasion intensity of low-temperature and high-salt water in the bottom layer was similar to that in 2016, and hypoxia was distributed in the region between 122.25°– 124°E and 31.0°– 32.5°N. The northern segment covered the entire northern sea area on the western side of 31.0°N latitude line, whereas the southern segment was distributed sporadically.

In 2015, the input of the CDW was not observed, the water mixed deeply, and only part of mild hypoxia, which is the lowest level of the hypoxic phenomenon during the study years, was found at the bottom.

Considering horizontal distribution, the CDW, TWC in the south area and the YSCWM in the north interacted and influenced each other. In 2011 and 2014, the intrusion of the southern water mass was weak, and hypoxia zones occurred in the southern area. In 2013, 2016, and 2017, the intrusion intensity of the bottom water mass increased. A high-salinity water mass (> 34) invaded northward from approximately 31.5°N and westward to 122.0°– 122.5°E. Hypoxia was distributed nearshore and south of the Yellow Sea, and divided into two segments by the waters at 31.5°– 32.0°N. The hypoxic phenomenon occurred in 2011, 2014, and 2015 with the lowest DO, < 2.0 mg L−1, and severe hypoxia emerged in 2013, 2016, and 2017 because of the general low DO, < 1.0 mg L−1 in the study area (Table 1).

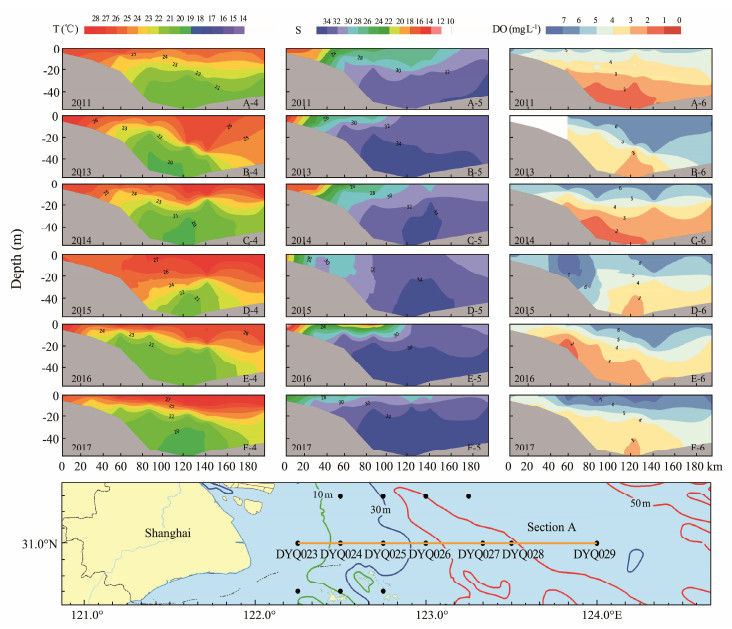

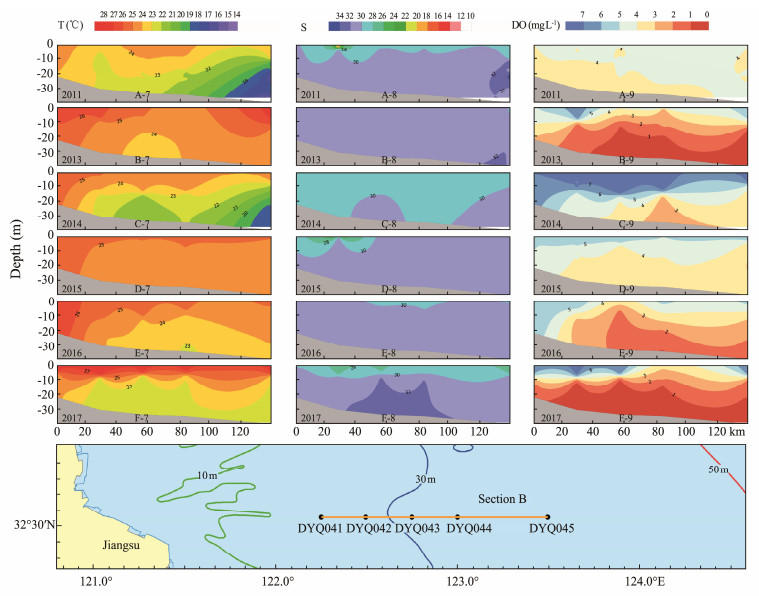

3.2 Vertical Distributions of Temperature, Salinity, and DO Along Typical TransectsSection A in the southern branch of the Yangtze Estuary and section B in the north of the study area were chosen in this paper, and the profiles of temperature, salinity, and DO from 2011 to 2013–2017 are illustrated (Figs.3 and 4); mark numbers of 4, 5, and 6 represent the temperature, salinity, and DO of section A, whereas 7, 8, and 9 represent those of section B, respectively. The seafloor topography of section B is gentle, and the water depth on the shore side was deeper than that of section A. Meanwhile, the water depth on the seaward side was shallower.

|

Fig. 3 Vertical profiles of temperature, salinity, and DO for section A. A-4 – F-4 for temperature, A-5 – F-5 for salinity, and A-6 – F-6 for DO. |

|

Fig. 4 Vertical profiles of temperature, salinity, and DO for section B. A-7 – F-7 for temperature, A-8 – F-8 for salinity, and A-9 – F-9 for DO. |

The temperature gradually decreased from surface to bottom, and the annual distribution was similar. The distributions of salinity were slightly different yearly and were similar in 2011, 2014, and 2016 (Fig.3). The salinity values gradually increased from the nearshore to the offshore area, demonstrating that the extending of CDW. The lines of salinity 30 displayed in the range from the station DYQ027 (123.3°E) to DYQ029 (124.0°E), and the salinity of the water was higher than 30 from 20 m below the surface to the bottom, forming a stable water mass structure. The characteristic of the salinity distribution in 2013 was similar to those in the previous years. The line of salinity 30 is limited in the area near the station DYQ026 (123.0°E), and the influence range of the CDW was relatively small. Compared with 2013, the influence range of the diluted water was smaller in 2017. In 2015, the diluted water was not found on the water surface according to the salinity distribution, and the isoline was almost vertically distributed.

The vertical distribution of DO revealed that the hypoxia zone in 2011 was located in the waters below 20 m, possibly extending from station DYQ025 (122.75°E) to station DYQ028 (123.5°E), with a length of 70 km and a thickness of 30 m. The distribution of hypoxia zones in 2014 was similar to that in 2011. This phenomenon appeared at a depth of 20 m, extending approximately 70 km, and the thickness of the hypoxic water layer was approximately 30 m. In 2016, the hypoxia zone was located at a depth of 20 m, just below the station DYQ025 (122.75°E) on the seaward slope of the continental shelf that extends to the deep sea. Hypoxia was absent in 2013, 2015, and 2017 on the whole and only some mild hypoxic phenomena were detected.

Hypoxia zones were generally found in 2011, 2014, and 2016, together with the stratification of water column. Meanwhile, the hypoxia events were absent in 2015 without the stratification, and were not observed in 2013 and 2017 with the weak diluted water intensity.

3.2.2 Vertical distributions in section BIn 2011 and 2014, the lower waters near the station DYQ045 (123.5°E) was invaded by the YSCWM at less than 19℃, and the temperature gradient from the surface to the bottom was evident (Fig.4). The water-temperature ranges in 2013 and 2015 were narrow, and the difference between the surface and bottom layers was not observed. In 2016, the temperature gradually decreased from the surface to the bottom. In 2017, the temperature also decreased downward and the difference between the surface and bottom was large, with the evident gradient change.

The salinity gradient from the surface to the bottom in section B was weaker than that of section A. The salinity in 2013, 2015, and 2016 was between 30 and 32 and that in 2014 was between 28 and 30, demonstrating the disappearance of the gradient. Salinity stratification was observed in 2011 and 2017, but the salinity range was small. The role of CDWs disappeared in this region.

According to the DO vertical distribution, the east-west length of the continuous extremely low-oxygen zone (< 1 mg L−1) in 2013 was approximately 90 km, starting from the station DYQ042 (122.5°E), and the hypoxic layer thickness was approximately 10 m. Hypoxia waters (< 2 mg L−1) stretched across the east and west, from the station DYQ041 to station DYQ042 (122.25°–122.5°E). Longitudinal hypoxia first appeared near the station DYQ042 at 15 m deep, and the hypoxic area was close to the surface. In 2016, the the hypoxia zone was located in the lower waters from the station DYQ043 (122.75°E) to station DYQ045 (123.5°E), and the hypoxia first appeared at approximately 10 m below the station DYQ043, with an east-west length of approximately 80 km and a thickness of approximately 10 m. In 2017, hypoxic water appeared in the middle and lower layers of the entire study area, – with the shallowest of only 5 m below the station DYQ044 (123.0°E). Severe hypoxia (DO < 1 mg L−1) almost stretched across the east and west of the study area, with an average thickness of approximately 15 m.

3.3 Different Water Masses Associated with the Hypoxia ZonesThe water depth of the study area ranged from 10 to 70 m. Massive runoff of the Changjiang is discharged into the East China Sea during the wet season in July/August/ September each year. Consequently, high-temperature and low-salinity CDW could extend out from the CE northeastwardly and southeastwardly, covering the low-temperature and high-salinity KSW and the ECSSW with thermohaline characteristics between the CDW and KSW (Zhu et al., 2016; Chi et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). The YSCWM occasionally appeared in the northeast part of the current study area in 2011 and 2014. The interaction of different water masses was discussed by the salinity and temperature distribution.

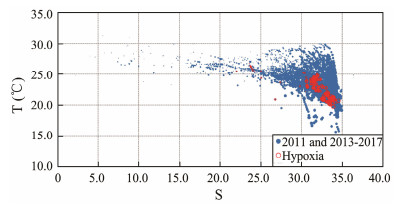

A scatter plot was established on the water temperature and salinity data from the study area in 2011 and from 2013 to 2017. The water masses of hypoxia were marked with red circles (Fig.5). The size of the dot represents the water depth; that is, a large dot indicates a deep water sample (the same symbols hold for Figs.6 – 8). The hypoxic phenomenon could be frequently found in the KSW, with salinity larger than 33.5℃ and temperature less than 22.0℃, and in the ECSSW, with lower salinity and higher temperature than the KSW. The red circles are separated into two clusters in Fig.5. Simultaneously, the YSCWM with a temperature lower than 20℃ is shown in Fig.5, whose water temperature was the lowest among water masses.

|

Fig. 5 Temperature-salinity scatter plot with the hypoxic sample points for 2011 and 2013 – 2017. A large dot indicates a deep water monitoring point. |

|

Fig. 6 Temperature-salinity scatter plots and the corresponding hypoxic points in 2011 and 2014 (above panel), 2013 and 2017 (middle panel), and 2015 and 2016 (below panel). |

|

Fig. 7 Three typhoon routes and the wind direction out of the CE in August, 2012. |

|

Fig. 8 Distribution of bottom DO concentrations in August 2012. |

Combined with the previous horizontal and vertical distributions of hypoxia zones, the current study area where hypoxia occurred was divided into the southern and northern segments (Zhu et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Particularly, the southern and northern segments were dominated by the KSW and ECSSW, respectively (Fig.5). The stratification caused by the CDW and the topography were important factors for the hypoxia emergence in the southern segment. Moreover, the KSW-dominated hypoxia zones in the southern segment were deep, ranging from −45 to −70 m. By contrast, the ECSSW-dominated hypoxia zones in the northern segment were shallow, ranging from −10 to −50 m.

4 Discussion 4.1 Feature of Hypoxia in the CEAs early as August 1999 (Li et al., 2002), the hypoxia zones was mainly found in two regions in the north and south of the CE: one is in the CE and another is distributed along the Zhejiang coast. The onset, duration, and extinction time of hypoxia in two regions are independent (Zhu et al., 2011; Chi et al., 2017).

Different from other scholars, the region of the current study is located in the northern region according to Chi et al. (2017), but divided into the north and south segments at a finer level by the boundary between 31.5°N and 32.0° N. The survey revealed the presence of deep grooves in the south segment, where the hypoxic area is located on a steep hill (122.5°– 123.0°E). The water depth in the north segment is only approximately 30 m. However, hypoxia was more severe in the north segment than in the south segment, and the hypoxia range extended further outside the current investigation area.

Horizontal and vertical distributions of hypoxia zones were discussed. In section A, the DO concentration was controlled by the stratification of water column, whereas in section B, the effect of the CDW almost disappeared, and the degree of thermohaline stratification was considerably weaker. The southern region (take section A as an example) is stratified; thus, the oxygen penetration from the surface to the bottom is difficult (Chen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016). Meanwhile, the decomposition of bottom organic materials consumes oxygen furtherly (Zhu et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, the southern hypoxia region is formed, mainly controlled by the stratification.

The stratification of water column in the northern segment (take section B as an example) was weak. Zhu et al. (2016) studied the particulate organic carbon (POC) and nutrient index in the South Yellow Sea and found that the content of POC was high in August, demonstrating high primary productivity and organic matter supply at the surface and additional high nutrient content at the bottom. This finding suggested that hypoxia in the South Yellow Sea was mainly controlled by biochemical degradation and oxygen consumption, which can be used as a reference for the severe hypoxia in the northern segment of our study. That is, the hypoxia events were not controlled by the stratification but mostly by biochemical degradation instead. This was different from the idea proposed by Chi et al. (2017), that hypoxia in the CE might be dominated by the pycnocline. So, the driving mechanism of hypoxia in the CE was different between the north and south segments.

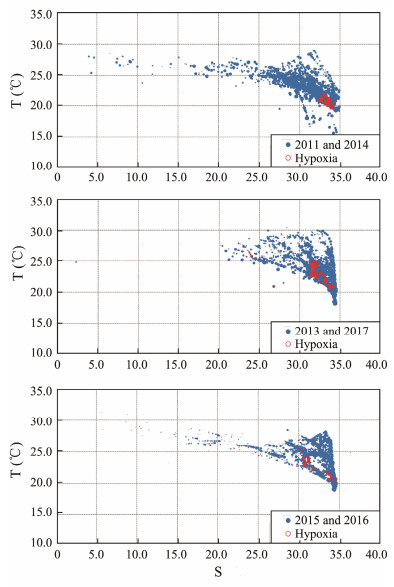

4.2 Regulation of Water Masses to Hypoxia ZonesVaried distributions of hypoxia zones in different years showed the changes in the dominant water mass. Hypoxia occurred in the southern segment in 2011 and 2014, in the northern segment in 2013 and 2017, and in both segments in 2016. However, hypoxia was not observed in 2015. The temperature-salinity relationship of the waters in the study area, especially those from the corresponding hypoxic zones, was shown in Fig.6 in 2011 and 2014 (above panel), 2013 and 2017 (middle panel), and 2015 and 2016 (below panel) (Fig.6).

The temperature and salinity of the above two panels in Fig.6 revealed that hypoxia was mainly found in the KSW, whereas only at a few stations observed hypoxia in the ECSSW in 2011 and 2014. Hypoxia was mainly found in the ECSSW in 2013 and 2017. Comparing the above two panels of Fig.6, more influences of CDW with a salinity of less than 20 were observed in 2011 and 2014 than in 2013 and 2017. The YSCWM occurred in the study area in 2011 and 2014 but not in 2013 and 2017, and additional high-temperature and high-salinity water masses were observed in 2013 and 2017. Consequently, hypoxia in the northern segment was induced by the strong northwestward intrusion of KSW. The stratification due to the additional extension of CDW was the main reason for hypoxia in the southern segment in 2011 and 2014. More hypoxic phenomena were found in 2013 and 2017 compared to in 2011 and 2014.

No hypoxic phenomenon was observed in 2015, but two segments of hypoxic areas emerged in 2016. The below panel of Fig.6 shows almost the same characteristics as the above two panels. Hypoxia could usually co-occur in the KSW and ECSSW. Such features were also demonstrated in the horizontal and vertical distributions of hypoxia in 2016. Hypoxia was witnessed more frequently in the southern segment of the study area than in the northern segment (Zhu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018, 2019). Nevertheless, the hypoxic intensity in the northern segment was substantially larger than that in the southern segment, according to the lowest DO contents. The input of land nutrients, even causing eutrophication, increase the biomass of phytoplankton and other organisms. As these organisms die and defecate, the organic matters sink and decay, which depletes DO in the surrounding waters (Zhu et al., 2011; Qian, 2017). Hypoxia in the northern segment was mainly attributed to the oxidation of organic matters (Zhu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020). The researches adding some biochemical elements and processes will be done in the future.

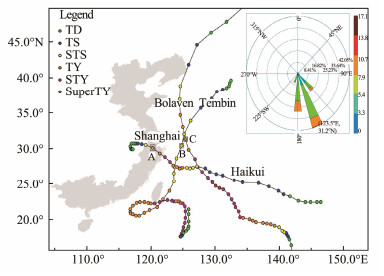

4.3 Impact of the Typhoon on the Hypoxic AreaTyphoon data in August 2012 were acquired from the 'CMA-STI Tropical Cyclone Best Path Dataset' of the China Typhoon Network (www.typhoon.gov.cn). Based on the national standard of 'Grade of Tropical Cyclone' (GB/T 19201-2006), subject to the average wind speed for 2 min before punctuality to punctuality, typhoon intensity was partitioned into the following: 1, tropical depression (TD; 10.8 – 17.1 m s−1); 2, tropical storm (TS; 17.2 – 24.4 m s−1); 3, severe tropical storm (STS; 24.5 – 32.6 m s−1); 4, typhoon (TY; 32.7 – 41.4 m s−1), 5, severe typhoon (STY; 41.5 – 50.9 m s−1); and 6, super typhoon (SuperTY; ≥ 51.0 m s−1).

Typhoon Haiku in 2012 (No. 11) was located at site A at 6 o'clock on August 8, with the latitude and longitude of 120.3°E and 30.1°N, respectively (Fig.7). With the lowest central pressure of 980 hPa and a 2-min average maximum wind speed near the center of approximately 33 m s−1, this typhoon landed in Ningbo, China, with a grade of TY. Typhoon Tempin in 2012 (No. 14) was located at site B at 12 o'clock on August 29, with the latitude and longitude of 124.8°E and 30.4°N, respectively (Fig.7). With the lowest central pressure of 980 hPa and a 2-min average maximum wind speed near the center of approximately 30 m s−1, the typhoon was of the grade STS. Typhoon Bolaven in 2012 (No. 15) was located at site C at 12 o'clock on August 27, with the latitude and longitude of 125.4°E and 31.3°N, respectively (Fig.7). With the lowest central pressure of 960 hPa and a 2-min average maximum wind speed near the center of approximately 35 m s−1, the typhoon was of the grade TY. According to the buoy wave data, wave heights in the study area when Typhoons Haikui, Tempin, and Bolaven passed across were 5 – 7 m, 3 – 4 m, and 7.5 – 9.5 m, respectively. Typhoons had a notable impact on the dynamic features of the study area. The wind direction was mainly southeastern out of the CE during August 12 – 22, 2012 (Fig.7).

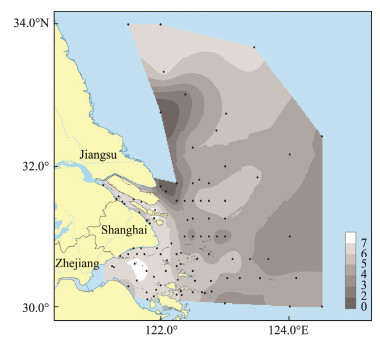

The bottom DO data in the study area were collected on August 12, 15, and 16, 18 to 22, and on September 1 and 2 in 2012 (Fig.8) to study the impact of the typhoon on the hypoxic phenomenon in the study area. The locations of the hypoxic zones in the monitoring area in 2012 were remarkably different from in other years. Moreover, sites with DO < 2 mg L−1 were found in the in-shore area of Jiangsu. The DO in the inner CE ranged from 6 to 7 mg L−1, whereas DO < 5 mg L−1 was observed in most waters in the CE. Even DO < 4 mg L−1 was found in the eastern segment. Affected by the three typhoons, the position of the hypoxic area in the study area moved northwestward, reaching the seacoast of Jiangsu in 2012. Compared with other years, the extent of the hypoxic area in 2012 was significantly reduced.

Overall, three typhoons hit the field of investigation in August 2012. The paths of the three typhoons show their direct impacts on the waters. Typhoons were not observed in other years during the 10-year period. The occurrence of a typhoon has a positive effect on the homogeneous mixing of water bodies. However, the duration of typhoon influence is difficult to identify; that is, the time for restoring the hypoxic phenomenon after the typhoon passes through cannot be determined. Strong wind could relieve hypoxia conditions by supplying DO through mixing, but it accelerated the formation of hypoxia afterward as a result of the enhanced phytoplankton bloom induced by wind mixing and high organic decomposition rates consuming more DO (Ni et al., 2016). Thus, special follow-up investigation should be carried out in a detailed manner.

5 ConclusionsThis paper analyzed the plane and vertical distribution characteristics of temperature, salinity, and DO and discussed the dominant water masses regulating hypoxia in the CE and its adjacent waters during a period of six years.

1) The hypoxia area was generally divided into two parts in the CE. The southern segment was out of the south branch of the CE, and the northern segment was in the junction zones between the South Yellow Sea and CE. The two segments were divided along the latitude line of 31.5° – 32°N. Hypoxia occasionally appeared in the two segments simultaneously. Hypoxia in the southern segment occurred more frequently than that in the northern segment.

2) The intensity of the KSW northwestern intrusion had a close connection with the location of hypoxia zones. Hypoxia in the southern segment appeared when the Changjiang River runoff was large and the northwestern intrusion of the KSW was weak. Simultaneously, the YSCWM emerged in the bottom water of the northwestern area, such as in the summer of 2011 and 2014. On the contrary, Hypoxia in the northern segment appeared when the strong KSW northwestern intrusion reached 31.5°N or further north in 2013 and 2017.

3) The occurrence of hypoxia in the southern segment was dominated by strong stratification and the long residence time of the low-oxygen KSW, and severe hypoxia in the northern segment was dominated by organic matter decomposition.

The location and range of hypoxia zones could be predicted for the early warning according to the relationship between the southern segment hypoxia and the temperature-salinity characteristics of the KSW over the years. The typhoon process has a significant impact on the positions of hypoxia zones in August, 2012.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFC310 1702); the Pilot Project of Early Warning Monitoring of Hypoxia and Ocean Acidification in the Changjiang Estuary of the Ministry of Natural Resources of China (MNR) (2020–2022); the Key Laboratory of Marine Ecological Monitoring and Restoration Technologies, MNR (No. ME MRT202009); the Key Laboratory of Marine Ecosystem Dynamics, Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources (No. MED202005); the Yangtze Delta Estuarine Wetland Ecosystem Observation and Research Station, Ministry of Education & Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (No. ECNU-YDEWS-2020).

Bianchi T. S., Allison M. A.. 2009. Large-river delta-front estuaries as natural 'recorders' of global environmental change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(20): 8085-8092. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0812878106 (  0) 0) |

Cai W. J., Huang W. J., Lutherlll G. W., Pierrot D., Li M., Testa J., et al. 2017. Redox reactions and weak buffering capacity lead to acidification in the Chesapeake Bay. Nature Communications, 8(369): 1-12. (  0) 0) |

Chen C. C., Gong G. C., Shiah F. K.. 2007. Hypoxia in the East China Sea: One of the largest coastal low-oxygen areas in the world. Marine Environmental Research, 64: 399-408. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2007.01.007 (  0) 0) |

Chen, J. F., Li, D. W., Jin, H. Y., Jiang, Z. B., Wang, B., Wu, B., et al., 2020. Changing nutrients, oxygen and phytoplankton in the East China Sea. In: Changing Asia-Pacific Marginal Seas. Atmosphere, Earth, Ocean & Space. Chen, C. T., and Guo, X., eds., Springer, Singapore, 155-178, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4886-4_10.

(  0) 0) |

Chen X., Shen Z., Li Y., Yang Y.. 2015. Physical controls of hypoxia in waters adjacent to the Yangtze Estuary: A numerical modeling study. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 97(1-2): 349-364. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.05.067 (  0) 0) |

Chi L. B., Song X. X., Yuan Y. Q., Wang W. T., Zhou P., Fan X., et al. 2017. Distribution and key influential factors of dissolved oxygen off the Changjiang River Estuary (CRE) and its adjacent waters in China. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 125: 440-450. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.09.063 (  0) 0) |

Diaz R. J., Rosenberg R.. 1995. Marine benthic hypoxia: A review of its ecological effects and the behavioural responses of benthic macrofauna. Oceanography and Marine Biology – An Annual Review, 33: 245-303. (  0) 0) |

Hietanen S., Jäntti H., Buizert C., Jürgens K., Labrenz M., Voss M., et al. 2012. Hypoxia and nitrogen processing in the Baltic Sea water column. Limnology and Oceanography, 57(1): 325-337. DOI:10.4319/lo.2012.57.1.0325 (  0) 0) |

Le K. F.. 1984. A preliminary study of the path of the Chang-jiang diluted water I. Model.. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 15(2): 157-167. (  0) 0) |

Li D. J., Zhang J., Huang D. J., Wu Y., Liang J.. 2002. Oxygen depletion off the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Estuary. Science in China Series D – Earth Sciences, 32(8): 686-694. (  0) 0) |

Li F. Q., Su Y. S.. 1999. Analysis of Marine Masses. Ocean University of Qingdao Press, Qingdao, 1-397.

(  0) 0) |

Li H. L., Chen J. F., Lu Y., Jin H. Y., Wang K., Zhang H. S.. 2011. Seasonal variation of DO and formation mechanism of bottom water hypoxia of Changjiang River Estuary. Journal of Marine Science, 29(3): 78-87. (  0) 0) |

Liu B., Zhang X., Zeng J. N., Du W.. 2018. The origin and process of hypoxia in the Yangtze River Estuary. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 38(1): 187-194 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Mao H. L., Gan Z. J., Lan S. F.. 1963. A preliminary study of the Yangtze diluted water and its mixing processes. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 5(3): 183-206. (  0) 0) |

Ni X. B., Huang D. J., Zeng D. Y., Zhang T., Li H. L., Chen J. F.. 2016. The impact of wind mixing on the variation of bottom dissolved oxygen off the Changjiang Estuary during summer. Journal of Marine Systems, 154: 122-130. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2014.11.010 (  0) 0) |

Qi J. F., Yin B. S., Zhang Q. L., Yang D. Z., Xu Z. H.. 2017. Seasonal variation of the Taiwan Warm Current water and its underlying mechanism. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 35(5): 1045-1060. DOI:10.1007/s00343-017-6018-4 (  0) 0) |

Qian, W., 2017. On the hypoxia in the Pearl River and Changjiang River Estuaries. PhD thesis. Xiamen University.

(  0) 0) |

Qian W., Dai M. H., Xu M., Kao S. J., Du C. J., Liu J. W., et al. 2017. Non-local drivers of the summer hypoxia in the East China Sea off the Changjiang Estuary. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science, 198: 393-399. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2016.08.032 (  0) 0) |

Rabalais N. N., Turner R. E.. 2001. Coastal and Estuarine Studies. Coastal Hypoxia: Consequences for Living Resource and Ecosystems. American Geophysical Union, Washington D. C., 461pp.

(  0) 0) |

Rabalais N. N., Cai W. J., Carstensen J., Conley D. J., Fry B., Hu X., et al. 2014. Eutrophication-driven deoxygenation in the coastal ocean. Oceanography, 27(1): 172-183. DOI:10.5670/oceanog.2014.21 (  0) 0) |

Turner R. E., Rabalais N. N., Justic D.. 2008. Gulf of Mexico hypoxia: Alternate states and a legacy. Environmental Science Technology, 42: 2323-2327. DOI:10.1021/es071617k (  0) 0) |

Wang B., Chen J. F., Jin H. Y., Li H. L., Huang D. J., Cai W. J.. 2017. Diatom bloom-derived bottom water hypoxia off the Changjiang Estuary, with and without typhoon influence. Limnology and Oceanography, 62: 1552-1569. DOI:10.1002/lno.10517 (  0) 0) |

Wang B. D.. 2009. Hydromorphological mechanisms leading to hypoxia off the Changjiang Estuary. Marine Environmental Research, 67: 53-58. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2008.11.001 (  0) 0) |

Wang B. D., Wei Q. S., Chen J. F., Xie L. P.. 2012. Annual cycle of hypoxia off the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Estuary. Marine Environmental Research, 77: 1-5. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2011.12.007 (  0) 0) |

Wang H. J., Dai M. H., Liu J. W., Kao S. J., Zhang C., Cai W. J., et al. 2016. Eutrophication-driven hypoxia in the East China Sea off the Changjiang Estuary. Environmental Science Technology, 50: 2255-2263. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.5b06211 (  0) 0) |

Wei H., He Y. C., Li Q. J., Liu Z. Y., Wang H. T.. 2007. Summer hypoxia adjacent to the Changjiang Estuary. Journal of Marine System, 67: 292-303. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2006.04.014 (  0) 0) |

Wei Q. S., Wang B. D., Chen J. F., Xia C. S., Qu D. P., Xie L. P.. 2015. Recognition on the forming vanishing process and underlying mechanisms of the hypoxia off the Yangtze River Estuary. Science China – Earth Sciences, 58(4): 628-648. DOI:10.1007/s11430-014-5007-0 (  0) 0) |

Wei Q. S., Wang B. D., Yu Z. G., Chen J. F., Xue L.. 2017a. Mechanisms leading to the frequent occurrences of hypoxia and a preliminary analysis of the associated acidification off the Changjiang Estuary in summer. Science China – Earth Sciences, 60: 360-381. DOI:10.1007/s11430-015-5542-8 (  0) 0) |

Wei Q. S., Wang B. D., Zhang X. L., Ran X. B., Fu M. Z., Sun X., et al. 2021. Contribution of the offshore detached Changjiang (Yangtze River) diluted water to the formation of hypoxia in summer. Science of the Total Environment, 764: 1-11. (  0) 0) |

Wei Q. S., Yu Z. G., Wang B. D., Wu H., Sun J. C., Zhang X. L., et al. 2017b. Offshore detachment of the Changjiang River plume and its ecological impacts in summer. Journal of Oceanography, 73: 277-294. DOI:10.1007/s10872-016-0402-0 (  0) 0) |

Weng X. C., Wang C. M.. 1989. A study on Taiwan Warm Current water. Journal of Ocean University of Qingdao, 19(1): 159-168 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang D., Yin B., Chai F., Feng X., Xue H., Gao G., et al. 2018. The onshore intrusion of Kuroshio subsurface water from February to July and a mechanism for the intrusion variation. Progress in Oceanography, 167: 97-115. DOI:10.1016/j.pocean.2018.08.004 (  0) 0) |

Zhang J., Gilbert D., Gooday A. J., Levin L., Naqvi S. W. A., Middelburg J. J., et al. 2010. Natural and human-induced hypoxia and consequences for coastal areas: Synthesis and future development. Biogeosciences, 7(5): 1443-1467. DOI:10.5194/bg-7-1443-2010 (  0) 0) |

Zhang J., Zhang Z. F., Liu S. M., Wu Y., Xiong H., Chen H. T.. 1999. Human impacts on the large world rivers: Would the Changjiang (Yangtze River) be an illustration?. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 13(4): 1099-1105. DOI:10.1029/1999GB900044 (  0) 0) |

Zhang W., Moriarty J. M., Wu H., Feng Y.. 2021. Response of bottom hypoxia off the Changjiang River Estuary to multiple factors: A numerical study. Ocean Modelling, 159: 101751. DOI:10.1016/j.ocemod.2021.101751 (  0) 0) |

Zhang W., Wu H., Zhu Z.. 2018. Transient hypoxia extent off Changjiang River Estuary due to mobile Changjiang River plume. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123(12): 9196-9211. DOI:10.1029/2018JC014596 (  0) 0) |

Zhang W., Wu H., Hetland R. D., Zhu Z.. 2019. On mechanisms controlling the seasonal hypoxia hot spots off the Changjiang River Estuary. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 124: 8683-8700. DOI:10.1029/2019JC015322 (  0) 0) |

Zheng J. J., Gao S., Liu G. M., Wang H., Zhu X. M.. 2016. Modeling the impact of river discharge and wind on the hypoxia off Yangtze Estuary. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 16: 2559-2576. DOI:10.5194/nhess-16-2559-2016 (  0) 0) |

Zhu J. R., Xiao C. Y., Shen H. T., Zhu S. X.. 1998. The impact of the Yellow Sea cold water mass on the expansion of the Changjiang diluted water. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 29(4): 389-394. (  0) 0) |

Zhu J. R., Zhu Z. Y., Lin J., Wu H., Zhang J.. 2016. Distribution of hypoxia and pycnocline off the Changjiang Estuary, China. Journal of Marine System, 154: 28-40. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2015.05.002 (  0) 0) |

Zhu Z., Wu H., Liu S. M., Wu Y., Huang D. J., Zhang J., et al. 2017. Hypoxia off the Changjiang Estuary and in the adjacent East China Sea: Quantitative approaches to estimating the tidal impact and nutrient regeneration. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 125: 103-114. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.07.029 (  0) 0) |

Zhu Z. Y., Zhang J., Wu Y., Zhang Y. Y., Lin J., Liu S. M.. 2011. Hypoxia off the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Estuary: Oxygen depletion and organic matter decomposition. Marine Chemistry, 125: 108-116. DOI:10.1016/j.marchem.2011.03.005 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22