2) Division of Oceanic Dynamics and Climate, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266100, China;

3) Qingdao Hatran Ocean Intelligence Technology Company Limited, Qingdao 266404, China

Explosive cyclone (hereafter EC), which is also called 'meteorological bomb', refers to a type of an extratropical cyclone with rapid intensification. Sanders and Gyakum (1980) firstly proposed the definition of EC to be an extratropical cyclone (the latitude of surface cyclone's center normalized to 60˚N), whose central sea level pressure (SLP) decreases at least 24 hPa within 24 h. An extratropical cyclone is usually accompanied by severe weather disasters including heavy rainfall, strong winds, and so on. Since the first climatologic and synoptic study of Sanders and Gyakum (1980), many studies were conducted in terms of statistical analyses, large-scale environment analyses and development mechanism analyses.

ECs are frequently observed in the east of continent such as the northwestern Pacific and northwestern Atlantic in cold seasons, especially the warm side of Kuroshio and Gulf Stream (Sanders and Gyakum, 1980; Roebber, 1984; Gyakum et al., 1989). Chen et al. (1992) analyzed 30-yr (1958–1987) observation data and pointed out that there existed two regions favorable to explosive cyclogenesis in eastern Asia region: one over the east of Japan Sea, and the other over the northwestern Pacific, east and southeast of Japan. Particularly, Lim and Simmonds (2002) suggested that the most explosive cyclones appeared in the northwestern Pacific. Yoshida and Asuma (2004) classified these cyclones into three types depending on positions of formation and of rapid development: the Okhotsk-Japan Sea (OJ-type) cyclones, which had the smallest deepening rate, originated over the eastern Asian continent and developed over the Japan Sea or the Okhotsk Sea; the Pacific Ocean-Land (PO-L-type) cyclones, which had the medium deepening rate, formed over the Asian continent and developed over the northwestern Pacific Ocean; and the Pacific Ocean-Ocean (PO-O-type) cyclones, which had the largest deepening rates, formed and developed over the northwestern Pacific Ocean. Heo et al. (2015) investigated the development mechanisms of an EC that occurred on 3–4 April 2012 over the Japan Sea through the numerical simulation and sensitivity experiments of using the Weather and Research Forecasting (WRF) model.

Many statistical analyses revealed that large-scale environment might provide favorable conditions for cyclone's development before cyclogenesis (Gyakum et al., 1992; Bullock and Gyakum, 1993). Yoshida and Asuma (2004) pointed out that OJ-type cyclones usually had a short-wave, upper-level jet stream and a strong baroclinic zone in the lower level. PO-L-type cyclones, associated with a zonally stretched jet stream, had a remarkable mid-level baroclinic zone. PO-O-type cyclones with a strong jet stream also had a distinct baroclinic zone in the mid-level, and a large water vapor budget (precipitation minus evaporation) appeared around the cyclone center. For large-scale oceanic circulation condition, meridional gradient of sea surface temperature (SST) played an important role for the cyclogenesis (Hanson and Long, 1985).

Many studies have been investigated to explore the development mechanism of explosive cyclones in different regions (Roebber, 1984, 1989; Sanders, 1986; Gyakum et al., 1989; Bullock and Gyakum, 1993; Wang and Rogers, 2001; Lim and Simmonds, 2002; Hirata et al., 2015). Previous studies have indicated that explosive cyclones were dominantly driven by the following factors:

1) The dynamic tropopause folding. Uccellini and Keyser (1985) found that stratospheric air invaded into troposphere by dynamic tropopause folding, causing the rapid development of cyclone. Ding et al. (2001) made statistics with explosive cyclones over the Pacific and the Atlantic, respectively. Their results showed that geostrophic transformation caused by non-zonal upper-level jet forced the momentum of jet transport downward, playing a key role for the development of cyclone.

2) The interaction between upper-level and low-level potential vorticity (PV). PV has been a key element to understand the thermodynamics and dynamics process of explosive cyclone since Hoskins et al. (1985). Čampa and Wernli (2012) indicated that development of extratropical cyclones can be seen as the interplay of three positive PV anomalies: an upper-level stratospheric intrusion, low-tropospheric diabatically produced PV, and a warm anomaly at the surface acting as a surrogate PV anomaly. Wang and Rogers (2001) pointed out that upper-level and low-level PV anomaly created a coherent cyclonic circulation from the tropopause to surface when cyclones attained their maximum intensity. This vertical coherent was called as 'PV tower'. Many researchers (e.g., Thorncroft et al., 1993; Martin, 1998; Posselt and Martin, 2004) indicated that the tropospheric high PV might extend equatorward and curve cyclonically to a 'hook-shaped' structure (known as a 'PV hook') during intensively deepening processes. Pang and Fu (2017) studied the characteristics of upper-tropospheric PV further. They found that the common feature of three EC cases is a 'hook-shaped' high-PV streamer wrapping counterclockwise around the center of surface cyclones on the southern and eastern sides and an 'arch-shaped' low-PV tongue that wrapped the high 'PV hook' head from the north.

3) The latent heat release (LHR). Many studies have showed that LHR have an important influence on the development of explosive cyclone (Anthes et al., 1983; Gyakum, 1983; Reed and Albright, 1986; Liou and Elsberry, 1987). The advection of warm air coupled with the ascent of moist air may enhance warming on the eastern side of the surface low during the condensation. This process further intensified the low-level gradient of temperature and consequently increased the magnitude of the advection of warm air there. The LHR may have significant impacts on both the static stability of the atmosphere as well as the distribution of PV and potential temperature. A significant LHR can result in the growth of a low-level PV anomaly, which in turn may have significant effects on low-level vorticity and self-development of synoptic cyclones. As the low strengthened, there can be more precipitation and latent heating, and so the feedback cycle continues, leading to further development of the cyclone.

An OJ-type cyclone was initially formed over the Japan Sea around 18 UTC 9 November 2013. This cyclone attracted us with many different characteristics from ordinary cyclone observed in this region, including its central sea level pressure, deepening rate and wind speed. It had the minimum SLP of 959.0 hPa, and the maximum deepening rate of 2.9 Bergeron which was much larger than the mean deepening rate of 1.33 Bergeron indicated by Yoshida and Asuma (2004). According to the facsimile weather map provided by Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), the maximum instantaneous wind speed of 42.7 m s−1 was observed in Erimo Misaki station in Hokkaido, and precipitation of 76.5 mm h−1 was also observed in Iki airport at Nagasaki Prefecture, which broke the local record of precipitation in November.

This paper aims to investigate the synoptic condition and development mechanism of this EC by using the reanalysis data, satellite imagery, upper-level and surface observation data. The WRF-3.5 modeling results will be used to examine the development mechanism of this EC. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the data and methodology. Section 3 presents overview of this explosive cyclone. Section 4 provides the observational analyses. Section 5 discusses the WRF modeling results. Finally, Section 6 presents conclusion and discussion.

2 Data and Methodology 2.1 DataThe data utilized in the present study are as follows:

1) NL (Final) Operational Global Analysis data provided by National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP). Download link is http://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds083.2/.

2) Upper air observation data provided by University of Wyoming. Download link is http://www.weather.uwyo.edu/upperair/sounding.htm.

3) Surface observation data provided by Global Telecommunications System (GTS). Download link is http://222.195.136.24/forecast.html.

4) Multi-Functional Transport Satellites-1R (MTSAT-1R) infrared satellite imagery provided by Kochi University of Japan. Download link is http://weather.is.kochi-u.ac.jp.

2.2 Methodology 2.2.1 Potential vorticityIn an isobaric coordinate system, the expression of PV is written as:

| $ \text{PV}=-g\left(\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}+f\right)\frac{\partial \theta }{\partial p}.$ | (1) |

Here, the unit of PV is defined as PVU which is 10−6 K kg−1 m2 s−1. g is gravitational acceleration, u and v are zonal and meridional wind speed, respectively. θ is potential temperature, and f is the Coriolis parameter.

2.2.2 PV tendency equationWu (2002) deduced the generalized PV based upon Ertel (1942). According to the thermodynamic energy equation and continuity equation, the PV tendency equation can be written as:

| $ \frac{\partial q}{\partial t}=-{\stackrel{\rightharpoonup }{V}}_{h}\cdot \nabla q+\frac{pg}{RT}w\frac{\partial q}{\partial p}+\frac{1}{\rho }{\stackrel{\rightharpoonup }{\omega }}_{a}\cdot {\nabla }_{3}\dot{\theta }.$ | (2) |

Here, ▽3 is a three-dimensional gradient operator, i.e., ▽3=i·∂/∂x+j·∂/∂y+k·∂/∂z, q represents PV,

This cyclone formed over the Japan Sea around 18 UTC 9 November 2013 and developed during its moving northeastward to the Okhotsk Sea. According to classification proposed by Yoshida and Asuma (2004), this cyclone is classified as OJ-type cyclone.

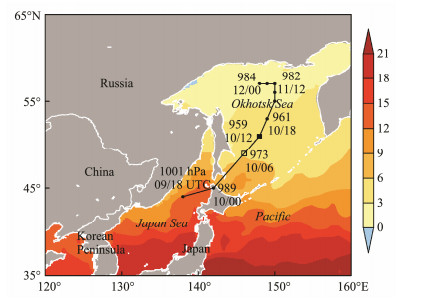

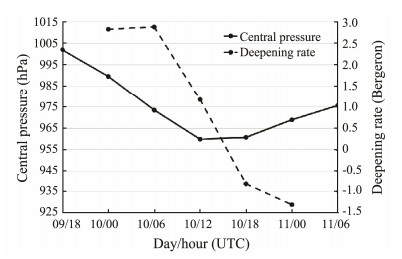

4-day (from 9 to 12 November 2013) mean SST derived from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) together with the moving track of cyclone center① are shown in Fig.1. As influenced by Tsushima Current, SST in southeast is significantly warmer than that in northwest of Japan Sea. SST of cradle where cyclone generated is about 12℃. Fig.2 presents the time series of central SLP and its deepening rate associated with this cyclone. At 18 UTC 9, the cyclone center with SLP of 1001.8 hPa was observed around (138˚E, 44˚N) over the Japan Sea. After 6 h, the cyclone center moved north-eastward from Japan Sea to the north of Hokkaido around (142˚E, 45˚N). By 06 UTC 10, the central SLP dropped rapidly to 973.4 hPa and reached its maximum deepening rate of 2.9 Bergeron as cyclone moved to (146˚E, 49˚N) over the Okhotsk Sea. During the next 6 h, the SLP continued decreasing to the minimum of 959.8 hPa, although the deepening rate was about 1.1 Bergeron. After 12 UTC 10, the cyclone center moved north-north-eastward and went to the Okhotsk Sea around 00 UTC 11 November 2013.

① The position of cyclone center is determined by the minimum of sea level pressure from FNL data.

|

Fig. 1 4-day (9 to 12 November 2013) mean sea surface temperature (shaded, 3℃ interval) and the moving track of cyclone center (solid line) from 18 UTC 9 to 00 UTC 12 November 2013. |

|

Fig. 2 Time series of central sea level pressure (solid line, hPa) and its deepening rate (dashed line, Bergeron) associated with the cyclone from 18 UTC 9 to 06 UTC 11 November 2013. |

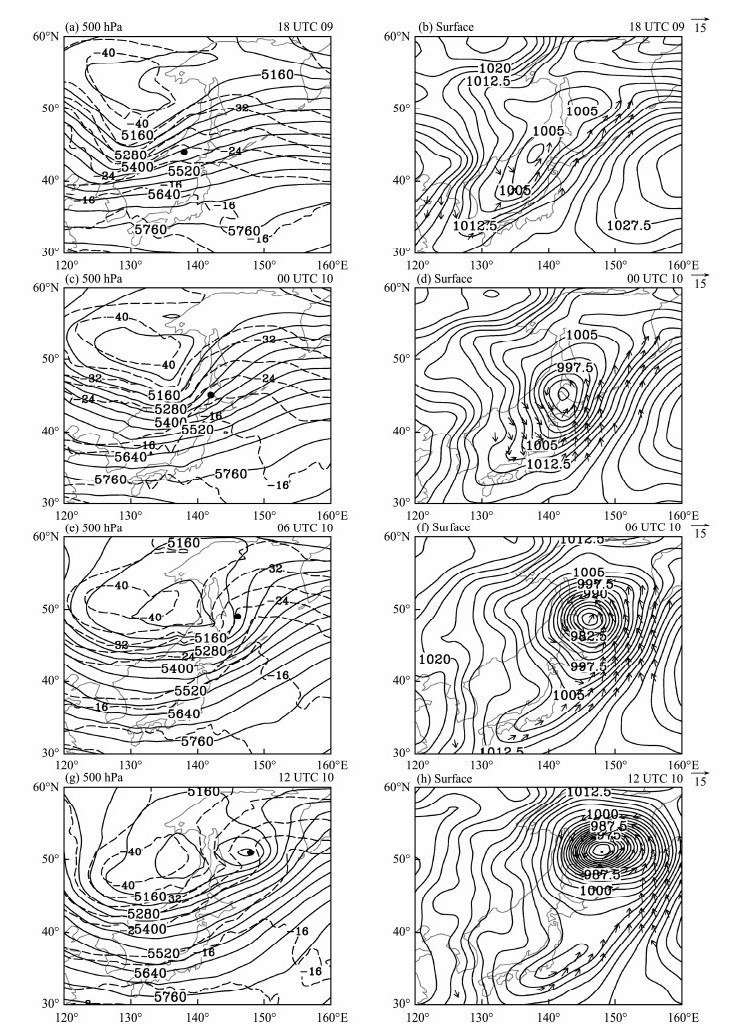

Weather maps from 18 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013 are shown in Fig.3. At 18 UTC 9 (Fig.3a), a cold vortex characterized by −40℃ isotherm was located around (128˚E, 55˚N) at 500 hPa. Associated with this cold vortex, there was a NNE-SSW oriented trough over the northeastern Asia, which was located about 8 longitude degree in the west of surface cyclone center. At surface map (Fig.3b), a NE-SW oriented synoptic-scale cyclone formed in the southeast of 500 hPa trough aloft.

|

Fig. 3 Weather charts: (a) 500 hPa geopotential height (solid line, 60 gpm interval) and air temperature (dashed line, 4℃ interval); (b) surface pressure (solid line, 2.5 hPa interval) and 10-m wind (arrow, greater than 10 m s−1) at 18 UTC 9 November 2013. The dots denote the central positions of cyclone. (c) and (d), (e) and (f), (g) and (h) same as (a) and (b), but for 00 UTC 10, 06 UTC 10, and 12 UTC 10 November 2013, respectively. |

During the next 12 h (Figs. 3c, 3e), the cold vortex surrounded by −40℃ isotherm at 500 hPa shrank slightly and moved southeastward. The 500 hPa trough turned to a NW-SE orientation gradually. The horizontal distance between 500 hPa trough and surface cyclone center became short. In the downstream of the upper ridge, the cyclone developed obviously and both isobars and isotherms appeared as 'S-shaped' over the Okhotsk Sea. At the surface (Figs. 3d, 3f), the cyclone moved northeastward with central pressure dropping rapidly. The remarkable cold front extended from the north of Hokkaido to the south of Kyushu. The southeastern quadrant of cyclone was surrounded by strong wind.

By 12 UTC 10, the cold vortex at 500 hPa strengthened from 5100 gpm to 5040 gpm and located over the lower-level cyclone center vertically (Fig.3g). The upper trough weakened further. At the surface, the cyclone moved to the Okhotsk Sea with its minimum central SLP of 959.8 hPa (Fig.3h). The cyclone center was surrounded by weak wind.

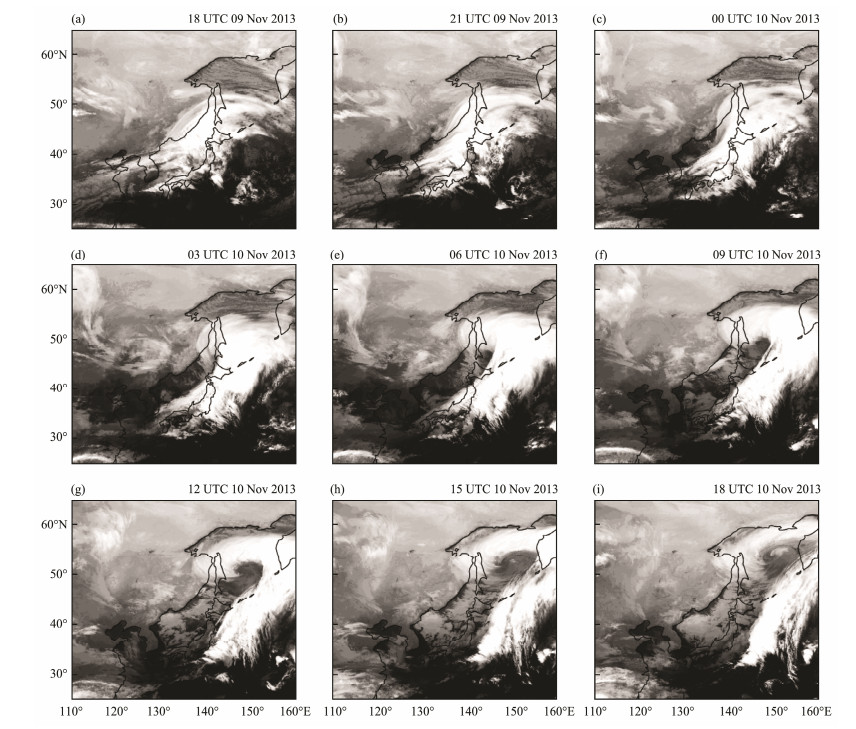

3.2 Evolutionary ProcessFig.4 displays 3-hourly MTSAT-1R infrared satellite imagery supplied by the Kochi University of Japan. According to the cloud features and synoptic analyses mentioned above, the evolutionary process of this EC may be classified into four stages: the initial stage, developing stage, mature stage and dissipating stage. The detailed evolutionary processes of this EC are described as follows.

|

Fig. 4 MTSAT-1R infrared satellite imagery from 18 UTC 9 to 18 UTC 10 November 2013 with 3-hour interval. |

At 18 UTC 9 (Fig.4a), the Japan Sea was occupied by a cloud system. In the southern side of this cloud, there existed a 'swallow-tailed-shaped' edge. During the next 3 h (Fig.4b), the anticlockwise movement of the northern part of this cloud made the whole cloud appear as 'S-shaped' structure. The cyclone under investigation generated in the southern side of the ENE-WSW oriented cloud band. The period from 18 UTC to 23 UTC 9 is the initial stage of this cyclone. During that period, the cyclone moved faster and its central SLP dropped about 12.3 hPa.

3.2.2 Developing stage (00 UTC 10–06 UTC 10 November 2013)By 00 UTC 10 (Fig.4c), the cloud system moved northeastward and covered the Japan Islands. The northwestern side of cloud band shrunk gradually, and the whole cloud looked more likely to be 'comma-shaped' structure. During the next 3 h (Fig.4d), the cloud system with three parts of head, notch and tail moved northeastward further. Up to 06 UTC 10 (Fig.4e), namely the moment of maximum deepening rate, the head of cloud continued to roll up anticlockwise and moved to the Okhotsk Sea. The tail of cloud was in NE-SW orientation and strengthened than before. The whole cloud system evolved into the 'spiralshaped' structure, suggesting the explosive development. During the developing stage, the cyclone moved fastest and its central SLP dropped about 16.0 hPa.

3.2.3 Mature stage (07 UTC 10–12 UTC 10 November 2013)During the next 3 h (Fig.4f), the cloud system moved along NNE-orientation and the head of spiral-shaped cloud rolled up cyclonically further and showed 'hook-shaped' structure. The tail of cloud strengthened further. By 12 UTC 10 (Fig.4g), the spiral head continued rolling up sharply and expanded its coverage over the Okhotsk Sea. There exhibited a 'eye-shaped' cloud-free area surrounded by the head and notch of cloud. The distinct tail of cloud extended about 15 degrees in latitude. The cloud system exhibited 'question mark-shaped' structure. Meanwhile, the cyclone attained its maximum intensity. During the mature stage, the cyclone moved slowly and its central SLP dropped about 14.0 hPa.

3.2.4 Dissipating stage (13 UTC 10–18 UTC 10 November 2013)After 13 UTC 10 (Figs. 4h, i), the 'question mark-shaped' cloud head started to loose its original structure over the Okhotsk Sea. The notch part was broken and the tail moved northeastward slowly. During the dissipating stage, the cyclone moved slowly and its central SLP reached to 961.0 hPa. As we will focus on the developing stage of this cyclone, thus the detailed analyses will be made in the following sections.

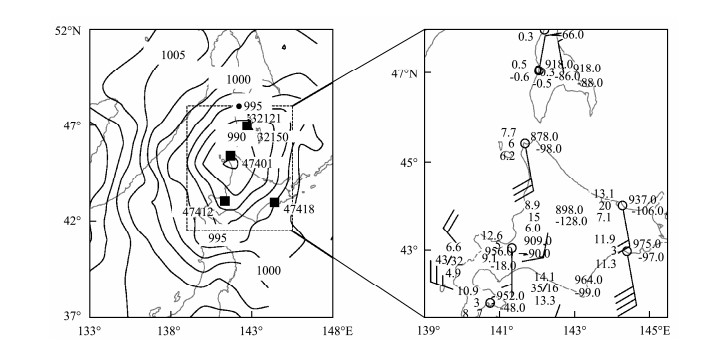

4 Observational Analyses 4.1 Developing ProcessThe cyclone evolved into its developing stage after 00 UTC 10 November 2013. The cyclone center (142˚E, 45˚N) was located near the Station Wakkanai (141.7˚E, 45.4˚N) based on sea level pressure field interpolated by the ground station (left panel of Fig.5). From the map of ground station (right panel of Fig.5), it can be seen that the sea level pressure was 987.8 hPa at station 47401, where 3-hourly pressure decrease reached to 9.8 hPa, air temperature was 7.7℃, and the dew-point temperature was 6.2℃. The prevailing wind direction in station 47401 was southeasterly to southerly, the wind speed was about 12 m s−1. At that moment, the maximum wind speed around the cyclone center occurred at station 47418 (144.4˚E, 43˚N), where prevailing wind direction was southeasterly by southerly, and the wind speed was about 16 m s−1. There existed an obvious cyclonic shear in the southwest of cyclone center.

|

Fig. 5 Left panel: The map of surface observation stations and sea surface pressure interpolated by observation data at 00 UTC 10 November 2013. The solid dot indicate surface observation station 32121, the solid square indicate surface and upper observation station 32150 (UHSS Juzhno-Sahalinsk), 47401 (Wakkanai) and 47412 (Sapporo). Right panel: The surface observation map within the dashed box of the left panel. |

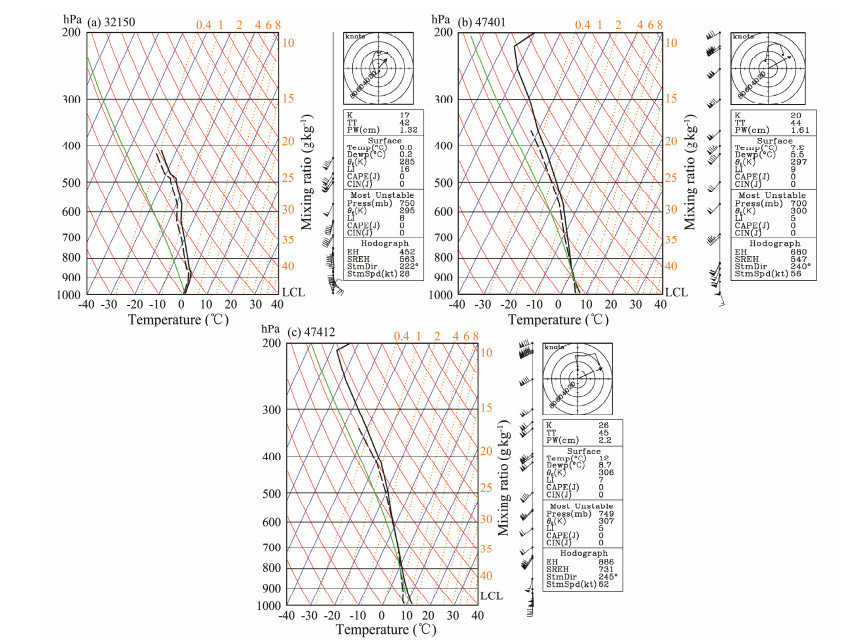

Skew T-logp diagrams at stations 32150, 47401, 47412, which may reflect the stability state of atmosphere, were shown in Fig.6. Station 32150 was located in the north of cyclone center, while station 47401 was near cyclone center, and station 47412 was located in the south of cyclone center. In skew T-logp diagrams of these three stations, the condition profile was completely located in the left of the air temperature. Air temperature profile was close to dew-point temperature profile, suggesting that the atmosphere tended to be saturated with a large amount of water vapors. Especially at station 47412, the air temperature profile coincided closely with dew-point temperature from 800 hPa to 600 hPa, indicating that the lower atmosphere had more moisture in the south of cyclone. The wind profiles showed that the prevailing wind direction was southeasterly near ground at stations 32150 and 47401. The prevailing wind direction exhibited clockwise rotation with height increase, suggesting the existence of warm advection. Southerly wind prevailed near ground at station 32150, which was beneficial to the transporting of warm and moist air into the cyclone center.

|

Fig. 6 Skew T-logp diagrams at station (a) 32150, (b) 47401 and (c) 47412 at 00 UTC 10 November 2013, respectively. The black solid line indicates air temperature, the black broken line indicates dew-point temperature, green line indicates the state curve, and LCL indicates lifting condensation level. |

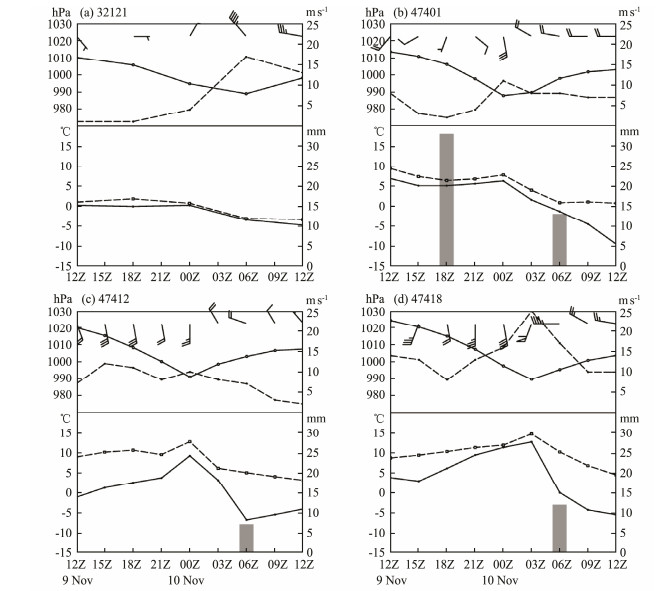

Fig.7 shows the time series of various atmospheric variables at stations 32121, 47401, 47412, 47418 from 12 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013, respectively. At station 32121 (Fig.7a), the prevailing wind direction turned instantly from northeast to northwest from 00 UTC 10 to 03 UTC 10. At the same time, the wind speed increased from 2 m s−1 to 18 m s−1 sharply. At stations 47401 and 47412 (Figs. 7b, 7c), the decrease of surface pressure about 26 hPa and 30 hPa were seen before the passage of cyclone, respectively. The prevailing wind direction turned instantly from south to northwest from 00 UTC 10 to 03 UTC 10. At station 47418 (Fig.7d), the prevailing wind direction turned instantly from southwest to west from 03 UTC 10 to 06 UTC 10. Meanwhile, the wind speed increased to 25 m s−1. At stations 47401, 47412 and 47418 (Figs. 7b, 7c, and 7d), the increase of air temperature and dew-point temperature occurred associated with the passage of surface cyclone, respectively. Up to 06 UTC 10, the 6 hourly accumulated precipitations were 13 mm, 7 mm and 12 mm at stations 47401, 47412 and 47418, respectively. Especially, the 6 hourly accumulated precipitation was 33 mm at station 47401 at 18 UTC 09 (Fig.7b).

|

Fig. 7 Time series of the sea level pressure (top panel, solid line), wind direction (top panel, barb), wind speed (top panel, dashed line), air temperature (bottom panel, dashed line), dew-point temperature (bottom panel, solid line) and precipitation (bottom panel, bar) at stations (a) 32121, (b) 47401, (c) 47412, (d) 47418 from 12 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013. |

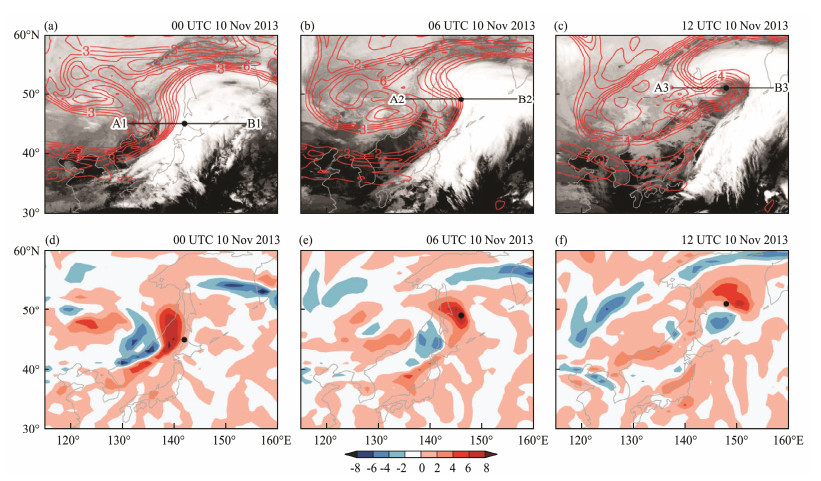

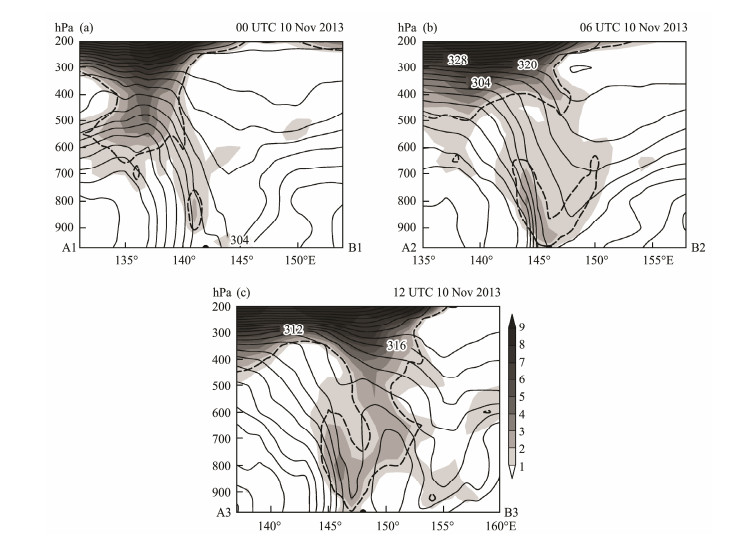

PV is a very useful tool to understand the development mechanism of EC (Hoskins et al., 1985). Figs. 8a, 8b, and 8c show the horizontal distributions of PV at 300 hPa to-gether with infrared satellite imagery from 00 UTC 10 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013. The lines in Figs. 8a, 8b, 8c will be used for the vertical cross-section analyses later. It can be seen that the high-PV air penetrated southward with its maximum value greater than 8.0 PVU (Fig.8a). As the time elapsed, the eastern sector of the PV system moved northeastward close to the surface cyclone center and exhibited a cyclonic roll-up, producing a strong horizontal PV gradient. Up to 12 UTC 10, the PV covered the surface cyclone center and showed a 'hook-shaped' structure (Fig.8c). By this time, the 'hook-shaped' PV closely inset the vacancy of 'question mark-shaped' cloud.

|

Fig. 8 Distribution of (a) 300 hPa PV (red line, 1 PVU interval) and infrared satellite cloud (shaded); (d) 300 hPa advection of PV (shaded, 2 PVU s−1 interval) at 00 UTC 10 November 2013. (b) and (e), (c) and (f) same as (a) and (d), but for 06 UTC 10 and 12 UTC 10 November 2013, respectively. |

Figs. 8d, 8e, 8f show the evolution of horizontal advection term of PV at 300 hPa from 00 UTC 10 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013. At 00 UTC 10 (Fig.8d), there existed positive horizontal advection in the right. The cyclone center was located in the right of positive horizontal advection with value of 2 PVU s−1. 6 h later (Fig.8e), the surface cyclone center was covered by the positive horizontal advection with the value greater than 8 PVU s−1, suggesting the rapid development of cyclone. Up to 12 UTC 10 (Fig.8f), the value of positive horizontal advection above surface cyclone center decreased to 4 PVU s−1, suggesting the slower development of cyclone.

Figs. 9a, 9b, and 9c show the vertical cross-section of PV and equivalent potential temperature along a west-east line in Figs. 8a, 8b, and 8c. PV contour of 1.6 PVU indicates the position of the dynamic tropopause. During the initial stage (Fig.9a), a gradual tropopause intrusion occurred in the upstream of surface cyclone center from 200 hPa to 600 hPa with a sharp gradient of PV. The PV at 800 hPa was weaker. 6 h later (Fig.9b), a region of significant positive PV developed from surface to 700 hPa and the value of PV core reached up to 3.0 PVU. Up to 12 UTC 10 (Fig.9c), the PV contour of 1.6 PVU of low-level extended upward and connected with upper-level PV. The interaction between upper and low-level PV led to the rapid deepening of explosive cyclone, which induced the low-level cyclonic circulation.

|

Fig. 9 Zonal profiles of (a) PV (shaded, 1 PVU interval) and equivalent potential temperature (solid line, 4 K interval; the dashed line indicates 1.6 PVU) along the cyclone's center at 00 UTC 10 November 2013. (b) At 06 UTC 10 November 2013. (c) At 12 UTC 10 November 2013. |

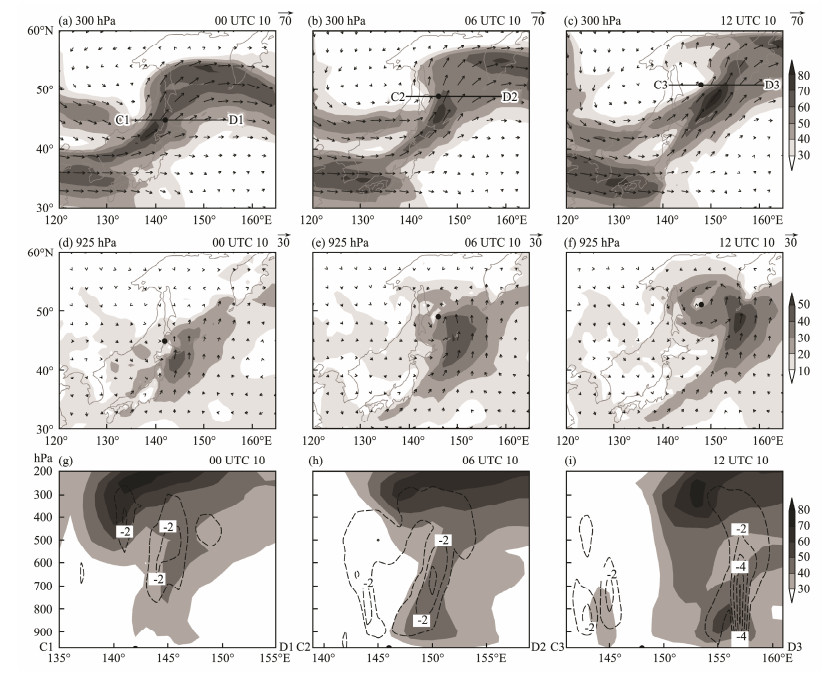

Fig.10 shows upper-level jet and low-level jet as well as the interaction between them. For upper-level jet at 300 hPa, one can see that there existed a pronounced southwest-northeast orientated jet over the Japan Sea-Okhotsk Sea at 00 UTC 10 (Fig.10a). The wind speed of jet core was stronger than 70 m s−1. The surface cyclone center was located in the right of jet core. 6 hours later (Fig.10b), the surface cyclone center was located in the left of jet core. Up to 12 UTC 10 (Fig.10c), the wind speed of jet core increased to 80 m s−1. The surface cyclone center was still located in the left of jet core. For low-level jet at 925 hPa, there existed a region of jet in the southeast of surface cyclone center with a great component of south wind at 00 UTC 10 (Fig.10d). The wind speed of jet core was stronger than 40 m s−1. As the time elapsed, the low-level jet developed and evolved into a 'comma-shaped' structure, which was similar to the shape of cloud (Fig.10e). At that time, the range of jet core extended although the wind speed of jet core remained. Up to 12 UTC 10 (Fig.10f), the wind speed of jet core increased to 50 m s−1. Figs. 10g, 10h, and 10i show the vertical profiles of horizontal wind speed and vertical velocity along the lines in Figs. 10a, 10b, 10c, respectively. It is seen that the upper-level gale extended downward and funneled from the tropopause to surface, which suggests the interaction between the upper-level and low-level PV. At 12 UTC 10 (Fig.10f), the strong upward motion was located in the two sides of cyclone, and the upward motion over the cyclone center was weak.

|

Fig. 10 (a) 300 hPa wind vector (arrow) and wind speed (shaded, 10 m s−1 interval) at 00 UTC 10 November 2013; (d) 925 hPa wind vector (arrow) and wind speed (shaded, 10 m s−1 interval) at 00 UTC 10 November 2013; (g) the profile of horizontal wind speed (shaded, 10 m s−1 interval) and vertical velocity (dashed line, 1.0 Pa s−1 interval) at 00 UTC 10 November 2013 along the line C1D1. (b), (e), (h) same as (a), (d), (g), but for 06 UTC 10.(c), (f), (i) same as (a), (d), (g), but for 12 UTC 10 November 2013. |

As the observational analyses using FNL data, which were 6 hourly time interval and 1˚×1˚ spatial resolution, were not sufficient enough to depict the evolutionary processes and spatial structure of this explosive cyclone, thus, in the following, we will rely on WRF modeling results to examine the detailed characteristic and development mechanism of the present EC case.

5.1 Model DescriptionThe atmospheric model used in the present study is WRF v3.5. Its main specifications are listed in Table 1. In the present WRF modeling, horizontal resolution is 10 km × 10 km with 550×450 horizontal grid points, and the vertical levels are 28. In the present study, planetary boundary layer scheme with YSU scheme (Hong et al., 2006), cumulus parameterization scheme with Kain-Fritsch scheme (Kain, 2004), long-wave radiation scheme with RRTM scheme (Mlawer et al., 1997), short-wave radiation scheme with Dudhia scheme (Dudhia, 1989), and microphysics scheme with Lin scheme (Lin et al., 1983), were employed respectively. The initial field is supplied by FNL data. The boundary condition is updated by FNL data every 6-hour.

|

|

Table 1 Specifications for WRF modeling |

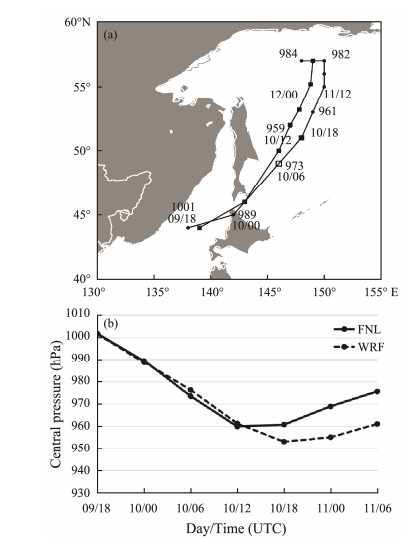

Comparison between WRF modeling results and FNL data was made in terms of moving track and sea level pressure. It is found that WRF model reproduced the cyclone moving track northeastward from the Japan Sea to Okhotsk Sea reasonably well compared with the FNL data from 18 UTC 9 to 06 UTC 11 November 2013 (Fig.11a). Fig.11b presents the time series of the minimum sea level pressure derived from FNL data and WRF modeling results, respectively. The sharp decrease of central sea level pressure from 18 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 was observed in both FNL data and WRF modeling results, suggesting that the WRF simulation revealed the whole evolutionary process of this EC. After 12 UTC 10, the sea level pressure recovered in FNL data, however, the WRF simulation result continued to decrease until 18 UTC 10. Based on analyses above, it can be inferred that this EC was reproduced reasonably well by WRF v3.5 modeling.

|

Fig. 11 (a) The trajectories of cyclone center provided by WRF modeling results (dashed line) and FNL data (solid line: Time interval between every two solid circles or squares is 6 h. (b) Time series of sea level central pressure (hPa) derived from FNL data (solid line) and WRF modeling results (dashed line). |

According to the analyses aforementioned, upper-level and low-level PV had significant influences on the development of cyclone. In the following, we will select 300 hPa and 850 hPa representing the upper-level and low-level, respectively. For six particular time at 21 UTC 09, 00 UTC 10, 03 UTC 10, 06 UTC 10, 09 UTC 10, 12 UTC 10 November 2013, each term in PV tendency equation at 300 hPa and 850 hPa, respectively will be analyzed based on WRF modeling results.

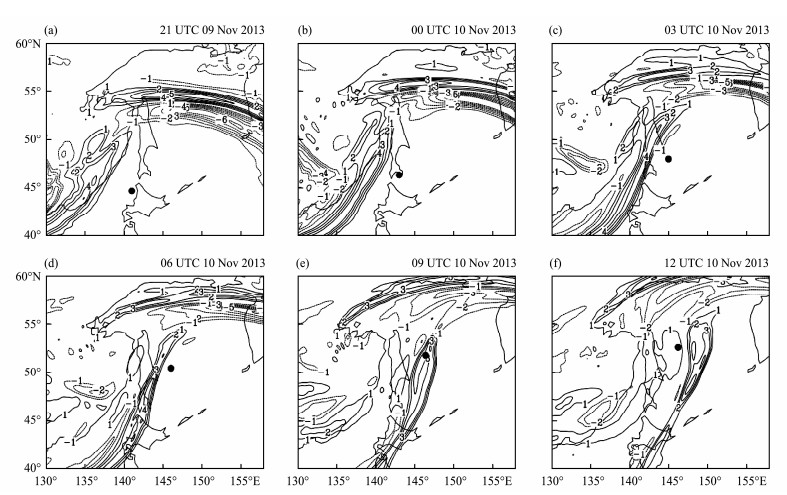

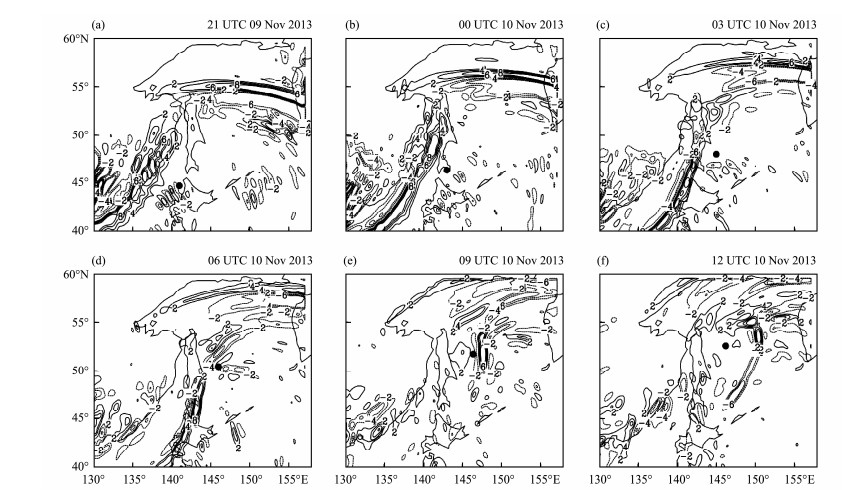

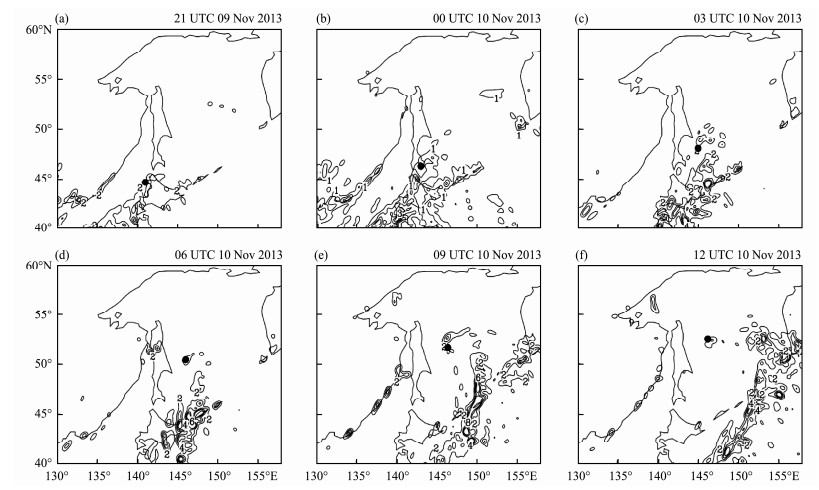

5.3.1 PV tendency at 300 hPaEach term in PV tendency equation at 300 hPa is analyzed. For local time change term of PV (Fig.12), at 21 UTC 09 November 2013, there existed a positive area (covered by the contour of 3–4 PVU (3 h)−1) over the east coast of Eurasia (Fig.12a). As the time elapsed (Figs. 12b-d), this positive area exhibited a strip shape and moved eastward to the cyclone center gradually. Up to 09 UTC 10 (Fig.12e), this positive area was located over the surface cyclone center. By 12 UTC 10 (Fig.12f), this positive area moved cross the cyclone center and was located over the east of cyclone center.

|

Fig. 12 Local time change of potential vorticity at 300 hPa from 21 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013 with 3 hour interval [in unit of PVU (3 h)−1]. The black dot denotes the central positions of cyclone. |

In the following part, the balance of PV tendency equation at 300 hPa will be analyzed. As analyzed in Eq. (2), the local time change of PV is totally balanced by three terms which was named as the horizontal advection of PV, the vertical advection of PV, and the diabatic heating term of PV. Generally, at 300 hPa, the horizontal advection of PV is around −6–4 PVU (3 h)−1, the vertical advection of PV is around −0.04–0.02 PVU (3 h)−1, and the diabatic heating term of PV is around −2–2 PVU (3 h)−1.

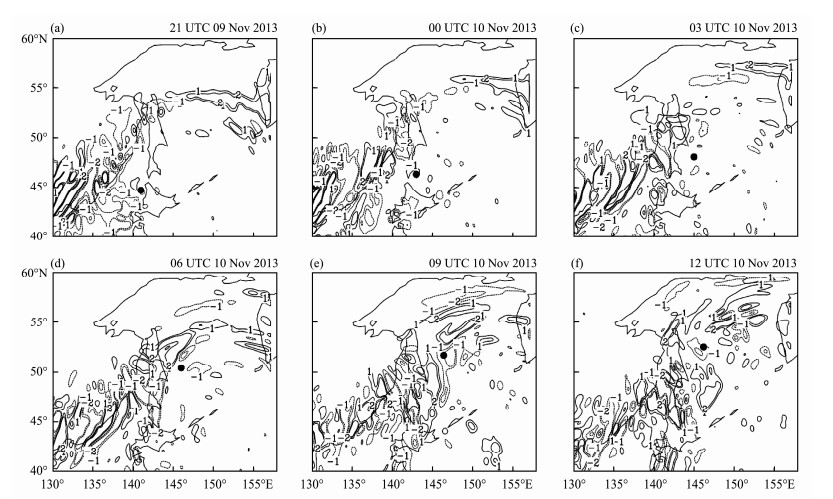

For horizontal advection of PV (Fig.13), at 21 UTC 09 November 2013, there existed a positive area (covered by the contour of 2–6 PVU (3 h)−1) over the east coast of Eurasia, which was corresponded to the local time change term of PV (Fig.13a). As the time elapsed (Figs. 13b–f), this positive area also moved eastward gradually in correspondence with the positive local time change term of PV, suggesting that the horizontal advection of PV has tight connection with the time change of PV. As the term of vertical advection of PV is about two orders of magnitude smaller than the term of horizontal advection of PV, so the role of vertical advection of PV can be neglected, and the horizontal distribution of vertical advection of PV is not shown. For the diabatic heating term of PV (Fig.14), it contributed about −1–1 PVU (3 h)−1 to the change of PV in the cyclone center area.

|

Fig. 13 Horizontal advection of potential vorticity at 300 hPa from 21 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013 with 3 hour interval [in unit of PVU (3 h)−1]. The black dot denotes the central positions of cyclone. |

|

Fig. 14 Diabatic heating term of potential vorticity at 300 hPa from 21 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013 with 3 hour interval [in unit of PVU (3 h)−1]. The black dot denotes the central positions of cyclone. |

In the following part, the balance of PV tendency equation at 850 hPa will be analyzed. Similar with 300 hPa, the local time change of PV at 850 hPa is also totally balanced by the horizontal advection of PV, the vertical advection of PV, and the diabatic heating term of PV. Generally, at 850 hPa, the horizontal advection of PV is around 1–2 PVU (3 h)−1), the vertical advection of PV is around 0.01–0.02 PVU (3 h)−1), and the diabatic heating term of PV is around 1–8 PVU (3 h)−1).

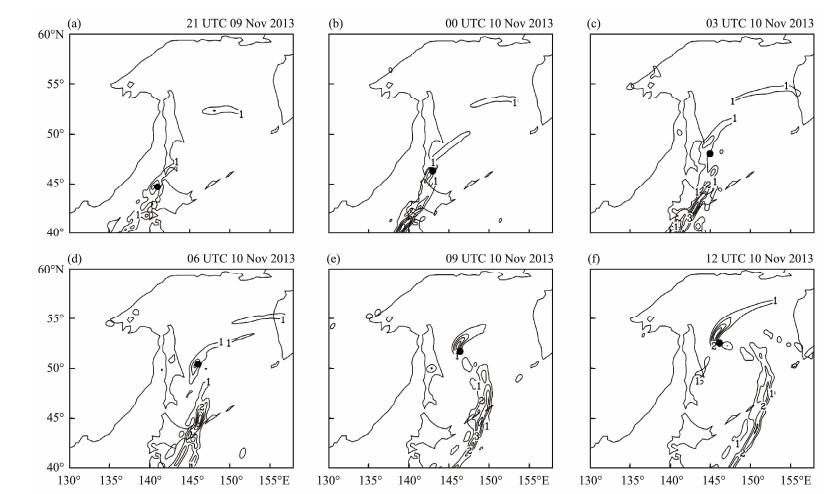

Each term in PV tendency equation at 850 hPa is analyzed. For local time change term of PV (Fig.15), at 21 UTC 09 November 2013, there existed a positive area (covered by the contour of 1–2 PVU (3 h)−1)) over the surface cyclone center (Fig.15a). As the time elapsed (Figs. 15b–f), this positive area was almost located over the surface low center synchronously.

|

Fig. 15 Local time change of potential vorticity at 850 hPa from 21 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013 with 3 hour interval [in unit of PVU (3 h)−1]. The black dot denotes the central positions of cyclone. |

For the horizontal advection term of PV (Fig.16), at 21 UTC 09 November 2013, there existed a positive area (covered by the contour of 4–6 PVU (3 h)−1)) over the surface cyclone center, which was corresponded to the local time change term of PV (Fig.15a). As the time elapsed (Figs. 16b–f), this positive area was almost lo cated over the surface cyclone center, in correspondence with the positive local time change term of PV. This term contributed about 2–6 PVU (3 h)−1) to the change of PV in the cyclone center area, suggesting that the horizontal advection term of PV may play a significant influence on the change of PV.

|

Fig. 16 Horizontal advection of potential vorticity at 850 hPa from 21 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013 with 3 hour interval [in unit of PVU (3 h)−1]. The black dot denotes the central positions of cyclone. |

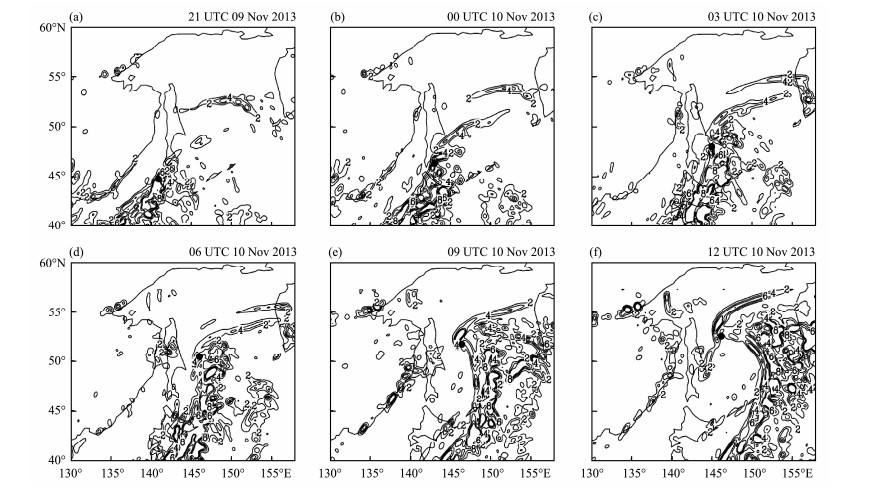

As the term of vertical advection of PV is on the order of 0.01–0.02 PVU (3 h)−1), which is only about two orders of magnitude smaller than the term of horizontal advection of PV, so this term can be neglected, and its horizontal distribution is not shown. For the diabatic heating term (Fig. 17), it contributed about 1–2 PVU (3 h)−1) to the change of PV, suggesting that the diabatic heating term had considerable influence on the change of PV.

|

Fig. 17 Diabatic heating term of potential vorticity at 850 hPa from 21 UTC 9 to 12 UTC 10 November 2013 with 3 hour interval [in unit of PVU (3 h)−1]. The black dot denotes the central positions of cyclone. |

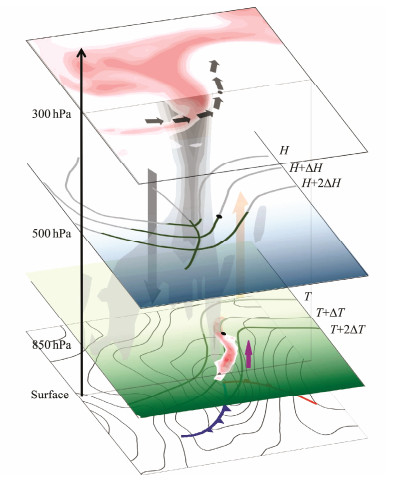

This paper presents observational and numerical modeling analyses of an EC from 9 to 11 November 2013 over the Japan Sea-Okhotsk Sea. A maximum deepening rate of 2.9 Bergeron was observed between 00 UTC 10 and 12 UTC 10 November 2013. Its central SLP attained the minimum value of 959.0 hPa around 12 UTC 10 November 2013. Based on the analyses of infrared satellite data, reanalysis data, weather maps, upper and surface observation data as well as WRF modeling results, the schematic diagram of this cyclone's structure at developing stage is summarized in Fig.18. The main findings of the present study are as follows.

|

Fig. 18 Schematic diagram of cyclone (red shading represents high PV at 300 hPa and PV anomaly at 850 hPa, gray shading represents vertical distribution of PV. Black arrow represents upper-level jet at 300 hPa, gray arrow represents downdraft, orange arrow represents updraft. Contours at 500 hPa indicate geopotential height. Contours at 850 hPa indicate air temperature, and the purple thick arrow represents low-level jet. Blue line represents cold front, red line represents warm front at surface. |

1) The upper-level PV extended downward, and connected with lower-level PV. The interaction between upper-level PV and low-level PV might lead to the rapid development of explosive cyclone.

2) Upper-level jet transported dry and cold air downward, while low-level jet transported moist and warm air upward, which strengthened the lower-level atmosphere's instability and supplied favorable conditions for the rapid intensification of cyclone. Meanwhile, the cyclone reached its maximum deepening rate when the upper-level jet and low-level jet interacted vertically.

3) By analyzing each term in PV tendency equation based on the WRF modeling results, it is shown that horizontal advection term of PV at 300 hPa and 850 hPa played a dominant role for the change of PV. At 850 hPa, the diabatic heating term had considerable influence on the change of PV.

6.2 DiscussionThis EC was quite different from other OJ-type cyclones in term of intensity and deepening rate as previously indicated by Yoshida and Asuma(2004, 2008). They showed a small contribution of LHR on the development of OJ-type cyclones. Heo et al. (2015) also studied an OJ-type explosive cyclone on 3–4 April 2012. The comparison between the EC case of Heo et al. (2015) and the present case is summarized in Table 2. It is obvious that these two EC cases are quite different in terms of occurrence of time, maximum deepening rate, the maximum instantaneous wind speed, as well as the dominant development mechanism.

|

|

Table 2 Comparison of two EC cases |

Heo et al. (2015) showed that LHR was an important factor for the development of their EC case. Based on the present WRF modeling results, we infer that diabatic heating term played a significant role for the development of the present EC case. Thus, it seemed that the role of diabatic heating on the development of OJ-type EC could not be neglected. However, it should be pointed out that the findings of the present study was only from the analyses of one OJ-type EC case. Thus, in future, it will be quite necessary to diagnose more OJ-type EC cases in order to verify the role of diabatic heating on the development of EC.

AcknowledgementsAll authors express their sincerely thanks to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) for financial support (Nos. 41775042 and 41275049). They also acknowledged NCEP/NCAR in USA for providing FNL data, the Kochi University in Japan for providing infrared satellite data, University of Wyoming in USA for providing upper observation data, and GTS for providing surface observation data. Miaomiao Jing expressed her great thanks to Mr. Baitang Sun, Dr. Shuqin Zhang, Dr. Yawen Sun, Miss Shan Liu and Mr. Lijia Chen for their kind helps to this paper.

Anthes, R. A., Kuo, Y. H. and Gyakum, J. R., 1983. Numerical simulations of a case of explosive marine cyclogenesis. Monthly Weather Review, 111: 1174-1188. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1983)111<1174:NSOACO>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Bullock, T. A. and Gyakum, J. R., 1993. A diagnostic study of cyclogenesis in the western North Pacific Ocean. Monthly Weather Review, 121: 65-75. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1993)121<0065:ADSOCI>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Čampa, J. and Wernli, H., 2012. A PV perspective on the vertical structure of mature midlatitude cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 69: 725-740. DOI:10.1175/JAS-D-11-050.1 (  0) 0) |

Chen, S. J., Kuo, Y. H., Zhang, P. Z. and Bai, Q. F., 1992. Climatology of explosive cyclones off the East Asian coast. Monthly Weather Review, 120: 3029-3035. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1992)120<3029:COECOT>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Ding, Z., Wang, J. and Zhai, Z., 2001. Research on composite diagnosis and mechanisms of explosive cyclones. Quarterly Journal of Applied Meteorology, 12: 30-40. (  0) 0) |

Dudhia, J., 1989. Numerical study of convection observed during the winter monsoon experiment using a mesoscale two-dimensional model. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 46: 3077-3107. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(1989)046<3077:NSOCOD>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Ertel, H., 1942. Ein neuer hydrodynamischer wirbelsatz. Meteorologische Zeitschrift, 59: 271-281. (  0) 0) |

Gyakum, J. R., 1983. On the evolution of the QE Ⅱ Storm, Ⅱ: Dynamic and thermodynamic structure. Monthly Weather Review, 111: 1156-1173. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1983)111<1156:OTEOTI>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Gyakum, J. R., Anderson, J. R., Grumm, R. H. and Gruner, E. L., 1989. North Pacific cold-season surface cyclone activity: 1975–1983. Monthly Weather Review, 117: 1141-1155. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<1141:NPCSSC>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Gyakum, J. R., Roebber, P. J. and Bullock, T. A., 1992. The role of antecedent surface vorticity development as a conditioning process in explosive cyclone intensification. Monthly Weather Review, 120: 1465-1489. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1992)120<1465:TROASV>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Hanson, H. P. and Long, B., 1985. Climatology of cyclogenesis over the East China Sea. Monthly Weather Review, 113: 697-707. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1985)113<0697:COCOTE>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Heo, K. Y., Seo, Y. W., Ha, K. J. and Park, K. S., 2015. Development mechanisms of an explosive cyclone over East Sea on 3–4 April 2012. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans, 70: 30-46. DOI:10.1016/j.dynatmoce.2015.03.001 (  0) 0) |

Hirata, H., Kawamura, R., Kato, M. and Shinoda, T., 2015. Influential role of moisture supply from the Kuroshio / Kuroshio extension in the rapid development of an extratropical cyclone. Monthly Weather Review, 143: 4126-4144. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-15-0016.1 (  0) 0) |

Hong, S., Noh, Y. and Dudhia, J., 2006. A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. Monthly Weather Review, 134: 2318-2341. DOI:10.1175/MWR3199.1 (  0) 0) |

Hoskins, B. J., Mcintyre, M. E. and Robertson, A. W., 1985. On the use and significance of potential vorticity maps. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 111: 877-946. DOI:10.1002/qj.49711147002 (  0) 0) |

Kain, J. S., 2004. The Kain-Fritsch convective parameterization: An update. Journal of Applied Meteorology, 43: 170-181. DOI:10.1175/1520-0450(2004)043<0170:TKCPAU>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Lim, E. P. and Simmonds, I., 2002. Explosive cyclone development in the Southern Hemisphere and a comparison with Northern Hemisphere events. Monthly Weather Review, 130: 2188-2209. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(2002)130<2188:ECDITS>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Lin, Y. L., Farley, R. D. and Orville, H. D., 1983. Bulk parameterization of the snow field in a cloud model. Journal of Climate and Applied Meteorology, 22: 1065-1092. DOI:10.1175/1520-0450(1983)022<1065:BPOTSF>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Liou, C. S. and Elsberry, R. L., 1987. Heat budgets of analysis and forecasts of an explosive deepening maritime cyclone. Monthly Weather Review, 115: 1809-1824. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1987)115<1809:HBOAAF>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Martin, J. E., 1998. The structure and evolution of a continental winter cyclone. Part Ⅰ: Frontal structure and the occlusion process. Monthly Weather Review, 126: 303-328. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1998)126<0303:TSAEOA>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Mlawer, E. J., Taubman, S. J., Brown, P. D., Iacono, M. J. and Clough, S. A., 1997. Radiative transfer for inhomogeneous atmosphere: RRTM, a validated correlated-k model for the longwave. Journal of Geophysical Research–Atmosphere, 102(D14): 16663-16682. DOI:10.1029/97JD00237 (  0) 0) |

Pang, H. and Fu, G., 2017. Case study of potential vorticity tower in three explosive cyclone over Eastern Asia. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 74: 1445-1454. DOI:10.1175/JAS-D-15-0330.1 (  0) 0) |

Posselt, D. J. and Martin, J. E., 2004. The effect of latent heat release on the evolution of a warm occluded thermal structure. Monthly Weather Review, 132: 578-599. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(2004)132<0578:TEOLHR>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Reed, R. J. and Albright, M. D., 1986. A case study of explosive cyclogenesis in the eastern Pacific. Monthly Weather Review, 114: 2297-2319. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1986)114<2297:ACSOEC>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Roebber, P. J., 1984. Statistical analysis and updated climatology of explosive cyclones. Monthly Weather Review, 112: 1577-1589. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1984)112<1577:SAAUCO>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Roebber, P. J., 1989. On the statistical analysis of cyclone deepening rates. Monthly Weather Review, 117: 2293-2298. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2293:OTSAOC>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Sanders, F., 1986. Explosive cyclogenesis in the west-central North Atlantic Ocean, 1981–84. Part Ⅰ: Composite structure and mean behavior. Monthly Weather Review, 114: 1781-1794. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1986)114<1781:ECITWC>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Sanders, F. and Gyakum, J. R., 1980. Synoptic-dynamic climatology of the 'bomb'. Monthly Weather Review, 108: 1589-1606. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<1589:SDCOT>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Thorncroft, C. D., Hoskins, B. J. and McIntyre, M. E., 1993. Two paradigms of baroclinic-wave life-cycle behavior. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 119: 17-55. DOI:10.1002/qj.49711950903 (  0) 0) |

Uccellini, L. W. and Keyser, D., 1985. The President's Day cyclone of 18–19 February 1979: Influence of upstream trough amplification and associated tropopouse folding on rapid cyclogenesis. Monthly Weather Review, 113: 962-988. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1985)113<0962:TPDCOF>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Wang, C. C. and Rogers, J. C., 2001. A composite study of explosive cyclogenesis in different sectors of the North Atlantic. Part Ⅰ: Cyclone structure and evolution. Monthly Weather Review, 29: 1481-1499. (  0) 0) |

Wu, R., 2002. Atmospheric Dynamics. China Higher Education Press, Beijing, 73-75 (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Yoshida, A. and Asuma, Y., 2004. Structures and environment of explosively developing extratropical cyclones in the northwestern Pacific region. Monthly Weather Review, 132: 1121-1142. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(2004)132<1121:SAEOED>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Yoshida, A. and Asuma, Y., 2008. Numerical study of explosively developing extratropical cyclones in the northwestern Pacific region. Monthly Weather Review, 136: 712-740. DOI:10.1175/2007MWR2111.1 (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19