2) Daya Bay Marine Biology Research Station, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen 518121, China;

3) University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

4) School of Pharmaceutical Science, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China;

5) Key Laboratory of Vegetation Restoration and Management of Degraded Ecosystems, South China National Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China

Along the world's coastal regions, there are a large number of macroalgae that live from the littoral zone to the depth with sufficient light for photosynthesis (Liu, 2018; Rybak, 2018). Macroalgae are important marine life and renewable resources (Gao et al., 2018, 2020) and play an important role in coastal ecosystems (Wells et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2018). As producers, macroalgae supply the high trophic levels via herbivory and detrital food chains, as well as refugia (Ware et al., 2019), and they also provide humans with foods, industrial products, medicines, biofuels, etc. (Yang, 2016; Ktari, 2017; Gao et al., 2020). Among these marine macroalgae, green algae (Chlorophyta) are the most abundant in coastal areas (Yang, 2016; Liu, 2018; Rybak, 2018), and in some areas they even account for more than 50% of total macroalgal biomass (Wells et al., 2007). The genus Ulva is one of the most widespread green macroalgae genera. Most of Ulva species have a large frond area (Rybak, 2018), which enables them to have high nutrient affinity (Luo et al., 2012; Li et al., 2019) and rapid growth rate, as well as high efficiency in nutrient removal from environment (Luo et al., 2012). Therefore, the Ulva species is often considered as an excellent candidate for biofilters to combat eutrophication and improve the health and sustainability of marine ecosystems (Gao et al., 2018). The Ulva species is also able to adapt to environmental changes more readily than other species, so its abundance can often be considered as an indicator of the effects of anthropogenic activities and changes in water quality of coastal ecosystems (Wells et al., 2007; Rybak, 2018). In addition, the Ulva species is a potential candidate for biofuels (Lum et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2018), foods (Roleda and Heesch, 2021) and medicines (Ktari, 2017).

Anthropogenic activities and climate change are exacerbating the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events such as typhoons. Passage of typhoons are normally accompanied by heavy rains, which brings a lot of freshwater from the land into the sea, and lowers salinity; moreover, this freshwater often contains abundant nutrient, leading to an increase of nutrient content in seawater (Li et al., 2009). Both the salinity and nutrients changes are known to affect the physiology of marine organisms, no exception for macroalgae. For example, the salinity decreased from 25 to 8 psu reduced the photosynthesis, superoxide dismutase activity, and cell-soluble sugars of Ulva prolifera (Xiao et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017). The extreme decrease in salinity from 45 to 5 psu even reduced the cellular proteins and soluble sugars of Ulva pertusa (Wang et al., 2007). In Ulva fasciata, changing salinity altered its growth in the early life history stage (Chen and Zou, 2015), and an optimal salinity of 15 psu was observed for its zoospore regeneration (Mantri et al., 2011). Apart from the change in salinity, the environmental nutrient increase generally improved the growth of Ulva reticulata and enhanced its nutrient uptake rate, chlorophyll a (Chl a) and cell nutrient content (Buapet et al., 2008). Such a stimulating effect was also observed in Ulva lactuca (Huang et al., 2022) and in Ulva intestinalis (Cohen and Fong, 2004). However, all of these studies focused on the effects of the change in separate salinity or nutrient on the physiology of Ulva species, but a few focused on their interaction (Kamer and Fong, 2001) although such an interactive effect often occurs in nature.

Daya Bay, a semi-enclosed subtropical bay, is geographically located in the northern part of the South China Sea between Shenzhen and Huizhou in Guangdong Province near Hong Kong (22.5˚N to 22.9˚N, 114.5˚E to 114.9 ˚E), with an area of about 600 km2 and depths ranging from 5 to 18 m (Xu, 1989). This bay hosts large populations of fish and benthic animals and rich biodiversity (Huang et al., 2005). Since the establishment of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone in the 1980s, Daya Bay and adjacent areas have experienced rapid industrial and mariculture development, resulting in a serious ecosystem degradation (Wang et al., 2008). To uncover the underlying mechanisms, many studies have been conducted to investigate the physicochemical variables and planktonic characteristics (e.g., Song et al., 2004, 2021; Wang et al., 2008). Yet, a few studies focused on macroalgae, although over 200 species of macroalgae live in this bay (Yang, 2016; Shi et al., 2021; Wan et al., 2022), which prevent a depth understanding of the reason for ecosystems degradation. On the other hand, about 5 typhoons land in the Daya Bay annually, and over 70% of them bring more than 100 mm of rainfalls within 24 h (He and Qiu, 2015). Together with the heavy rains, the land-based inputs of nutrient-rich freshwater usually cause salinity to drop from 33 psu to less than 20 psu and nitrate concentration to rise above 50 µmol L−1 in this bay (Song et al., 2004). To what extent such changes in salinity and nitrogen affect macroalgae is still unclear. Only when these factors are studied experimentally can we better understand why macroalgae proliferated and ecosystems then deteriorated.

In this study, we cultured a green macroalga Ulva fasciata Diels under a matrix of salinity (31, 20 and 10 psu) and nitrogen levels (5, 20 and 60 µmol L−1) in the Daya Bay and monitored its photosynthetic property during cultivation. U. fasciata is a dominant species in this bay (Shi et al., 2021; Wan et al., 2022), and is representative and widespread along coastal waters from the Bohai Sea to the South China Sea, China (Liu, 2018). In addition, studying the effects of the changes in salinity and nitrogen would be useful to predict the growth and succession of U. fasciata, which dominate nutrient dynamics and serve as foods for microbial, meio- and macrofaunal communities in the Daya Bay.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Sampling Protocol and Experimental DesignDuring a summer period (June 27 – 29, 2022), we conducted an experiment to investigate the effects of reduced salinity and nitrogen (N) enrichment on the Chlorophyta Ulva fasciata at the Daya Bay Marine Biology Research Station of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Specimens of U. fasciata was collected from a fish raft located 500 m offshore in the Daya Bay (114˚31´E, 22˚ 44´N), in the northern South China Sea. After collecting the specimens (16:00, local time), thalli of U. fasciata were placed in a dark carrying bucket and returned to the station laboratory within 15 min, where the uniform and healthy thalli were collected, carefully washed to remove adhering epiphytes or sediment, and cut into 2 cm × 2 cm squares with a sterilized blade.

The cutted thallus pieces were used to explore the effects of reduced salinity and N enrichment as follows: A total of 20 pieces of the cutted thalli were placed in each 1-L transparent PET culture bottle filled with 950 mL medium, and 3 saline gradients were prepared to mimic the extreme salinity reduction caused by rainfall, i.e., Sal 31 psu (field condition, control), 20 and 10 psu according to the salinity fluctuation in coastal or estuarine waters (Li et al., 2009; Li, 2019). The freshened medium with Salinity of 20 and 10 psu was obtained by mixing field seawater with highly purified freshwater. Before the mix ing, the seawater was filtered through a polycarbonate membrane with a pore size of 0.2 µm (Isopore, Merck Millipore Ltd.), and the ultrapure water was enriched with nutrients N (NaNO3) and P (NaH2PO4) to the same levels as field to eliminate the effects of nutrients alteration. As the background micronutrients in field seawater are complicated and unclear to us, we did not adjust the content of micronutrients in the medium to exclude the effects of improper adjustment. To mimic the effect of nutrients input from land, exogenous nitrogen (NaNO3) was added into all 3 salinity treatments at a final concentration of 20 µmol L−1 and 60 µmol L−1, within the N-enriched range in the Daya Bay (Ke et al., 2019). The field nutrient status (about 5 µmol L−1) was used to serve as control.

Under sunlight, cultivation of U. fasciata (three replicate for each treatment, 27 cultures in total) began at sunset (18:00, local time) to eliminate the shock effect of strong light, and lasted 48 h in a tank with continuously pumped surface seawater for temperature control. During cultivation, the photosynthetic efficiency of U. fasciata from each culture bottle was measured at the time of sunset on the first day (18:00 p.m., the initial state) and the next noon (12:00 p.m.) and sunset time (18:00 p.m.) using a portable chlorophyll fluorometer (AquaPen AP-100C, Photon Systems Instruments, Prague, Czech Republic) and photosynthetic instrument (YZQ-201A, Yizongqi Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

2.2 Chlorophyll FluorescenceTo determine the maximum photochemical quantum yield (FV/FM) of photosystem Ⅱ (PSII) of U. fasciata, 3 thallus pieces were randomly taken from each culture flask and dark-adapted in a fluorometer cuvette in a growth chamber for 15 min at a temperature set to field conditions. Then, the maximum (FM) and minimum fluorescence (FO) of each sample were measured under a weakly modulated measuring light with a saturation light pulse (3000 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 600 ms). To obtain the effective PSII photochemical quantum yield (ΦPSII), the maximum (FM') and instantaneous fluorescence (Ft) were measured under field light condition. The FV/FM and ΦPSII were calculated (Genty et al., 1989) as:

| $\frac{F_V}{F_M}=\frac{F_M-F_O}{F_M} ; \Phi_{P S H}=\frac{F_M^{\prime}-F_t}{F_M^{\prime}} . $ | (1) |

The relative electron transport rate (rETR) of PSII was measured under 7 different actinic light intensities (PAR, μmol photons m−2 s−1), for 60 s exposure at each light intensity, and the rETR was estimated (Schreiber, 2004) as:

| $ rETR = {\Phi _{PSH}} \times 0.5 \times PAR \times 0.84t, $ | (2) |

where 0.5 and 0.84 indicate the absorbed light energy evenly distributed to PSII and PSI and the efficiency of absorbed light energy, respectively. Then, the rETR was plotted against light intensity to obtain a rapid light response curve (RLC).

2.3 Photosynthetic Oxygen Evolution MeasurementThe photosynthetic O2 evolution rate versus irradiance (P vs. E) curve of U. fasicata was determined at 9 light intensities (i.e., 0, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Photosynthetic O2 evolution was measured using a photosynthetic instrument equipped with LED lights to provide a range of 0 – 2400 μmol photons m−2 s−1 in a 15-mL photosynthetic chamber, in which the temperature was maintained with an equipped cooler (Li et al., 2022; Wan et al., 2022).

To measure the O2 evolution rate, 0.10 – 0.20 g fresh weight (FW) algal thalli was placed in the photosynthetic chamber and dark-acclimated for 30 min at field temperature (i.e., 31℃) (Li et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). The rate of O2 evolution was then monitored under a range of light intensities as mentioned above. The photosynthetic rate was calculated by normalizing the O2 evolution rate to the fresh weight of algal thalli and expressed as μmol O2 g FW−1 h−1. Before measuring the P vs. E curve, the O2 consumption rate was measured in the dark to calculate the dark respiration rate (Rd, μmol O2 g FW−1 h−1). Unfortunately, we missed the Pn and Rd measurements at 36 and 48 h time points in the N enrichment treatment due to the unavailability of photosynthetic instrument.

2.4 Cell CompositionAt the beginning and end of cultivation, thalli of U. fasicata were collected to measure the pigment, carbohydrate, and protein contents and antioxidant activities.

To determine the pigment content, 0.10 g of fresh thalli were transferred to 10 mL of absolute methanol and ground with silica sand (HF-24, Hefan Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and extracted overnight at 4℃ in the dark. After centrifugation at 4℃ for 10 min (10000 g), the optical absorption spectra of the supernatant were measured using a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan). Chlorophyll a (Chl a) and carotenoid (Car) contents were calculated according to Wellburn (1994).

To measure the carbohydrate content, 0.20 g of fresh thalli was ground with 2 mL distill water. Then, the mixture was transferred to a 5 mL tube and incubated in boiled water for 10 min. After centrifugation, the carbohydrate in the supernatant was measured using a carbohydrate assay kit (A045-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Engineering Company, China) with an anthrone-sulfuric acid method (Laurentin and Edwards, 2003).

To measure the protein content, 0.10 g of fresh thalli were extracted in 2 mL 0.1 mol L−1 phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and ground. After centrifugation, the protein in the supernatant was measured using a soluble protein assay kit (A045-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Engineering Company, China) with the bicinchoninic acid method (Smith et al., 1985). With this protein extraction, the cellular superoxide dismutase activity (SOD) was measured using an assay kit according to manufacture's protocol (A001-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Engineering Company, China).

2.5 Statistical AnalysisThe photosynthetic parameters derived from the RLC or P vs. E curve, i.e., maximum relative electron transfer rate (rETRmax) or photosynthetic O2 evolution rate (Pmax, μmol O2 (g FW)−1 h−1 and saturation irradiance (EK, μmol photons m−2 s−1) were calculated (Henley, 1993) as:

| $ {P_n} = {P_{\max }} \times \tanh (\alpha \times \frac{I}{{{P_{\max }}}}) + {R_d}, $ | (3) |

where Pn indicates rETR or photosynthetic rate (μmol O2 (g FW)−1 h−1) and Rd indicates dark respiration rate (μmol O2 (g FW)−1 h−1) (for RLC, Rd was set to 0), and EK was calculated as:

| $ {E_K} = ({P_{\max }} + {R_d})/\alpha . $ | (4) |

Means and standard deviations (mean and SD) were presented in the figures. Paired t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni posttests (Prism 8, Graphpad software) were used to determine the significant difference between different salinity or nitogen treatments, at confidence level of 0.05.

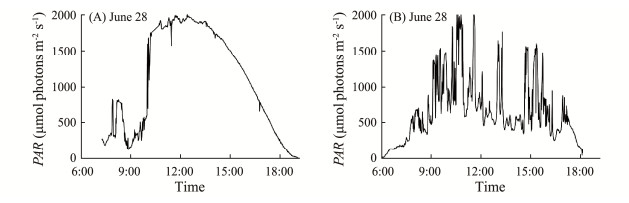

3 ResultsDuring the experimental days (June 27 – 29), incident photosynthetically active solar radiation (PAR) reached up to 1920 μmol photons m−2 s−1 at midday in the Daya Bay (Fig.1). Seawater temperature and salinity at the sampling site were 31.16℃ and 31.35 psu, while concentrations of total inorganic nitrogen, phosphorus and silicate were 4.76, 0.08 and 17.56 µmol L−1, respectively (data not shown).

|

Fig. 1 Incident photosynthetic active radiation (PAR, µmol photons m−2 s−1) at the experimental site in Daya Bay, during the experimental days (A, June 28 and B, June 29, 2022). |

Cell composition and antioxidant capacity of U. fasicata at the beginning (T0) and end (T48) of cultivation are shown in Table 1. Chl a and Car content at T0 were 0.36 ± 0.01 and 0.28 ± 0.03 mg g−1 FW, respectively; whereas carbohydrate and protein content were 16.9 ± 2.66 and 0.13 ± 0.02 mg g−1 FW, respectively, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was 249.8 ± 2.00 U g−1 FW. Compared with T0, Chl a and carbohydrate content at T48 were reduced by ca. 33% and ca. 90%, respectively, while SOD activity was increased by ca. 20%. Chl a, Car, carbohydrate and protein content increased when salinity decreased from 31 to 10 psu, while SOD activity decreased when salinity decreased from 31 to 20 psu and then increased to 10 psu (Table 1). The N enrichment increased cellular pigments, carbohydrate and protein content, and SOD activity at field salinity (Sal 31 psu), but decreased them at lower salinity (e.g., Sal 10 psu) (Table 2).

|

|

Table 1 Cellular chlorophyll a (Chl a), carotenoids (Car), carbohydrate and protein contents (mg g−1 FW), and superoxide dismutase activity (SOD, U mg−1 protein) of U. fasciata before (T0) and after 48 h cultivation (T48) under 3 salinity gradients. Numbers show the means and standard deviations (mean ± sd, n = 3); and uppercase and lowercase letters show significant differences between T0 and T48 at Sal 31 psu and between different salinities at T48, respectively |

|

|

Table 2 Ratio of chlorophyll a (Chl a), carotenoids (Car), carbohydrate and protein content and superoxide dismutase activity (SOD) of U. fasciata under nitrogen enrichment (N20, N60) to that under field condition (NCR) after 48 h of cultivation under 3 salinity gradients. Numbers are presented as the means and standard deviations (mean ± sd, n = 3) |

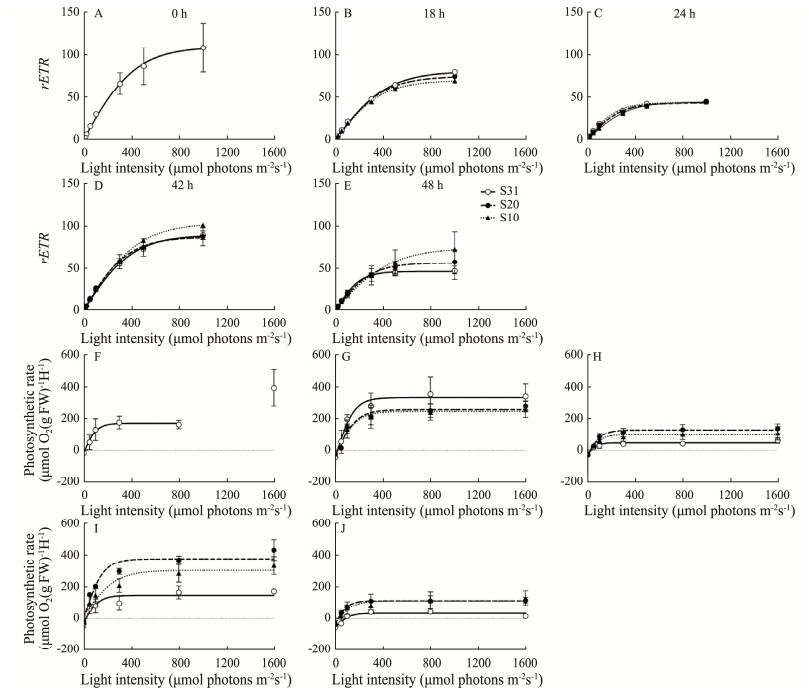

The photosynthetic characteristics of U. fasicata under 3 salinity conditions are shown in Fig.2. Based on the rapid light response curves (RLCs, Figs.2A – E), there was little or no photoinhibition even when the PAR irradiance was above 1000 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Lower salinity significantly reduced the photosynthetic efficiency during short-term cultivation (The 18 h cultivation is defined as 'short-term'.) (paired t-test, p < 0.001) (Figs.2B, G). This reduction effect weakened with increasing cultivation time and returned to a stimulation effect after 24 h of cultivation (Figs.2A – E). The results of the curve of photosynthetic O2 evolution rate versus irradiance (P vs. E) confirmed such an effect transition, which went from the negative to the positive range (Figs.2F–J). In addition, the photosynthetic efficiency measured at midday (Figs.2B, G, D, I) was higher than that measured at dusk (Figs.2C, H, E, J), indicating a diurnal rhythm in the photophysiology of macroalgae.

|

Fig. 2 Rapid light response curves (RLCs, A–E) and photosynthetic O2 evolution rate (µmol O2 (g FW)−1 h−1) vs. irradiance (µmol photons m−2 s−1) (P vs. E) curves (F–J) of U. fasciata measured at time-points 0 h (A, F), 18 h (B, G), 24 h (C, H), 42 h (D, I) and 48 h (E, J) during cultivation periods. The points show the mean values of the measurements on three independent cultures, and the error bars show the standard deviations (n = 3), often within the symbols. |

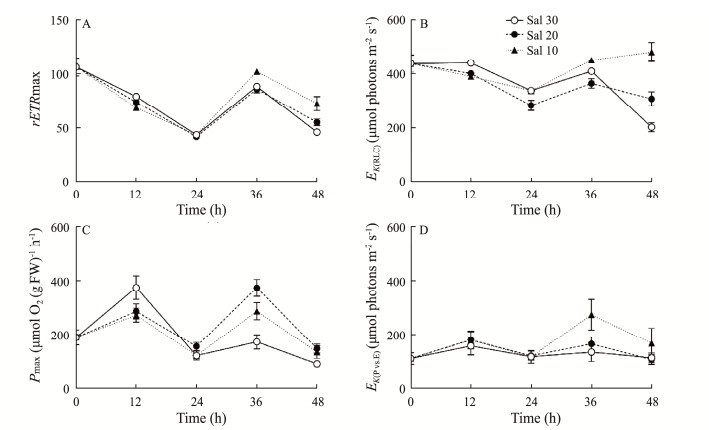

The RLC-derived maximum rETR (rETRmax) of U. fasicata in Sal 10 psu was 13% lower than that in Sal 31 at 18 h of cultivation, but 15% and 56% higher at 42 and 48 h of cultivation, respectively (Fig.3A). Such the culture-time-related negative and positive effects also occurred for the saturation irradiance (EK) (Fig.3B). Based on the maximum photosynthetic rate (Pmax) derived from the P vs. E curve, this was 27% lower in Sal 10 psu than that in Sal 31 psu at 18 h of cultivation (375.5 vs. 273.2 µmol O2 (g FW)−1 h−1), but 66% and 47% higher at 42 and 48 h of cultivation, respectively (Fig.3C). A similar effect due to reduced salinity also occurred in the EK(P vs. E) derived from the P vs. E curve (Fig.3D). Moreover, the EK(RLC) derived from the RLCs was 2 to 4 times higher than the EK(P vs. E) derived from the P vs. E curves at different seawater freshening and at different measurement time-points (Figs.3B, D), indicating the different light dependence of chlorophyll fluorescence and O2 production.

|

Fig. 3 Time-series changes in the photosynthetic parameters derived from the RLC curves (A, maximum relative electron transfer rate, rETRmax; and B, saturation irradiance, EK(RLC), µmol photons m−2 s−1) and from the P vs. E curves (C, maximum photosynthetic O2 evolution rate, Pmax, µmol O2 (g FW)−1 h−1; and D, saturation irradiance, EK(P vs. E), µmol photons m−2 s−1) of U. fasciata cultured in 3 saline gradients. The points show the mean values of the measurements on three independent cultures, and the error bars show the standard deviations (n = 3), often within the symbols. |

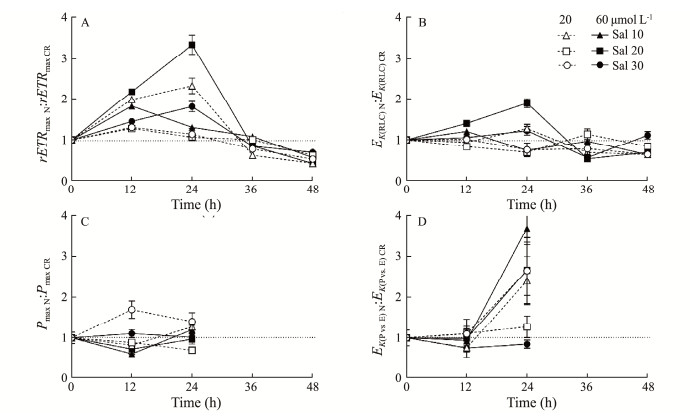

To investigate the effect of the N enrichment, we compared the photosynthetic parameters derived from the RLC or P vs. E curves of the N enrichment treatments with those of the field conditions, and showed their ratios in Fig.4. In general, N enrichment increased both the photosynthetic efficiency (rETRmax and Pmax) and saturation irradiance (EK) as the ratio was above 1; and N enrichment at 20 and 60 µmol L−1 varied the degree of stimulation among the different salinity treatments. Such a stimulation by N enrichment was more evident at rETRmax after 24 h of cultivation (Fig.4A), with a maximum value of 230% at 60 µmol L−1 N enrichment in Sal 20 psu; furthermore, an interactive effect of reduced salinity and enriched N occurred when compared to that under field conditions (ca. 80%, Sal 31 psu). With increasing cultivation time, stimulatory effect of N enrichment became less pronounced and was even undetectable 40 h later. Finally, the different stimulation of N enrichment on the photosynthetic parameters derived from the RLCs and the P vs. E curves again indicates the different light dependence of chlorophyll fluorescence and O2 production.

|

Fig. 4 Time-series changes in the ratio of photosynthetic parameters of U. fasciata under N-enriched conditions (N20, N60) to those under field conditions (NCR): the RLC-derived maximum relative electron transfer rate (A, rETRmax) and saturation irradiance (B, EK(RLC)), and the P vs. E curve-derived maximum photosynthetic O2 evolution rate (C, Pmax) and saturation irradiance (D, EK(P vs. E)). The points show the mean values of the measurements on three independent cultures, and the error bars show the standard deviations (n = 3), often within the symbols. |

It is known that freshwater input from land, caused by heavy rainfall, simultaneously reduces salinity and increases nutrients in coastal waters (Li et al., 2009). It is often assumed that the decrease in salinity osmotically stresses macroalgae, while the increase in nutrients benefits them (Buapet et al., 2008; Xiao et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2022). This sparked our interest in investigating how this concurrent change affects the physiology of U. fasicata, a dominant species in the Daya Bay. We found that the reduced salinity decreased the photosynthetic efficiency of U. fasicata during short-term cultivation, but this negative effect became weaker and reversed to a positive effect with increasing cultivation duration. In addition, nitrogen enrichment mitigated the negative effect of reduced salinity during short-term cultivation. This provides insight into the flourishing of macroalgae in coastal waters where salinity and nutrients often covary strongly due to the land-derived inputs, including the Daya Bay.

Unlike animals, algae do not have the ability to expel excess water when extracellular salinity is lower than intracellular salinity, but have to respond to hypoosmotic stress by passively tolerating an increase in cell volume or reducing osmotically active solutes in the cells (Kirst, 1989), resulting in the change in cellular ultrastructure, a lack of cell metabolites, and decrease in growth due to an increase in defense costs (Kirst, 1989; Chen and Zou, 2015; Li et al., 2017). Reduced salinity can also directly lead to a lack of dissolved ions, such as carbonate, whose availability is low at low salinity (Zhai et al., 2005), as well as a lack of the ions transported across the cell membrane, leading to a decrease in the algal photosynthesis (Wang et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2016). In addition, osmotic stress can also stimulate the production of intracellular ROS, leading to cellular toxicity when the generation of ROS exceeds the antioxidant defenses or disrupts the redox signaling, thus inhibiting algal photosynthesis (Luo and Liu, 2011). Thus, oxidative stress can also suppress the synthesis of e.g. the D1 protein at the transcriptional and translational levels, thereby reducing the photosynthetic capacity of algae (Kojima et al., 2008). Consistently, a stressful effect of reduced salinity on the photosynthetic efficiency of U. fasicata was observed within a short-term cultivation (Figs.2 and 3). However, after a long-term acclimation (e.g., termed as > 24 h), reduced salinity stimulated the photosynthesis of U. fasicata, as shown by the promotion of photosynthetic efficiency (Figs.2 and 3). The Ulva species is normally considered euryhaline and has developed a novel strategy to protect itself against the stress caused by the altered salinity. A good example of this adaptability is the opportunistic species Ulva flexuosa, which presents in a very broad Salinity gradient from marine to freshwater system (Rybak, 2018). Another stimulatory effect of lower salinity has been reported to enhance zoospore induction of U. fasciata (Mantri et al., 2011).

Furthermore, it is common that the primary reduction in photosynthetic capacity due to salinity stress is followed by partial or complete recovery (Li et al., 2019), but the time required for this depends on the degree of hypoosmotic stress (Fig.3) and is also species-specific (Cohen and Fong, 2004; Mantri et al., 2011; Li et al., 2017). To date, the mechanism of low salinity-triggered stimulation of photosynthetic capability is still unclear, although one of the main proposed mechanisms is to maintain osmotic balance with the environment by adjusting the water and potassium ion (K+) content of cell tissue in the short term (Kamer and Fong, 2001), and to increase the intercellular solutes such as amino acids and glucose during a long-term acclimation (Edwards et al., 1988; Kirst, 1989). Adaptation to reduced salinity is also supported by an increase in the cellular pigment, carbohydrate, and protein contents, as shown here (Table 1) or in other studies (Kamer and Fong, 2001; Cohen and Fong, 2004; Li, 2019). The mechanism of the stimulatory effect of reduced salinity on algal photosynthesis needs further investigation.

Normally, nutrient N is a limiting factor for the growth and productivity of algae in the Daya Bay, as shown by the phytoplankton blooms after N supply (Wang et al., 2008; Song et al., 2021). In this study, we also demonstrated that N enrichment mitigated the stressful effects of reduced salinity on photosynthesis of U. fasicata during short-term cultivation (Fig.4). In principle, adequate N supply can promote the content and activity of N-containing compounds such as RubisCO, a key rate-limiting enzyme, and consequently the substrate content of algal photosynthesis (García-Sánchez et al., 1993), and stimulate photosynthetic physiological processes and increase photosynthetic capacity (Fig.4). Nitrogen supply can also activate oxidative phosphorylation in the cells, a biochemical process that promotes carbon fixation and increase the photosynthetic capacity of macroalgae (Huppe et al., 1992). In addition, U. fasicata has a higher ability to take up nutrients from seawater at low salinity (Kamer and Fong, 2001), which may help to maintain osmotic balance with the environment and maintain cell viability (Fig.4). According to Cohen and Fong (2004), algae are able to utilize all osmolytes, including NO3−, to maintain osmotic balance. Thus, after NO3− has been taken up and pooled in the tissue, the requirement for K+ as an osmolyte can be reduced. Another advantage of NO3− as an osmolyte is the need for NO3− to maintain growth. Therefore, N enrichment could promote algal growth by directly contributing to osmoregulation, thus alleviating the stress caused by reduced salinity (Kamer and Fong, 2001; Cohen and Fong, 2004) and promoting the photosynthetic efficiency of U. fasicata (Fig.4). Our results also show that N enrichment at lower salinity decreases the content of Chl a, carbohydrates and proteins in cells (Table 2). We hypothesise that the lower salinity resulted in a greater release of the precursors of these macromolecules than the promotion of enriched N to the photosynthates, leading to a decrease in Chl a, carbohydrate and protein content. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon needs to be further investigated.

5 ConclusionsIn this study, we found that reduced salinity decreased photosynthesis of U. fasicata in the short term, while enrichment with nutrient nitrogen attenuated this negative effect. The negative effect caused by reduced salinity became weaker and reversed to a positive effect with increasing acclimation time, which expands our understanding of how U. fasicata responds to different salinity and nutrient conditions it is exposed to under natural conditions. Our results, along with others (e.g., Kamer and Fong, 2001; Cohen and Fong, 2004), shed light on the future flourishing of Ulva species in the Daya Bay, where salinity and nutrients may interact more strongly due to more input from land and increasingly heavy rainfall events.

AcknowledgementsThis study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 20022YFC3102 405), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42425004, 32371665) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Nos. 2022A151501 1461, 2022A151501 1831).

Author Contributions

Mingyue Wan, Lingling Bai, Li Li and Guangyan Ni contributed to performing the experiment. Mingyue Wan, Lingling Bai, and Guangyan Ni contributed to the experimental designs and data analysis. Mingyue Wan, Lingling Bai, Li Li, Yehui Tan and Guangyan Ni contributed to the paper writing. All authors approved this version to be submitted.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Buapet, P., Hiranpan, R., Ritchie, R. J., and Prathep, A., 2008. Effect of nutrient inputs on growth, chlorophyll, and tissue nutrient concentration of Ulva reticulata from a tropical habitat. Science Asia, 34: 245-252. DOI:10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2008.34.245 (  0) 0) |

Chen, B., and Zou, D., 2015. Altered seawater salinity levels affected growth and photosynthesis of Ulva fasciata (Ulvales, Chlorophyta) germlings. Acta Oceanologia Sinica, 34(8): 108-113. DOI:10.1007/s13131-015-0654-3 (  0) 0) |

Cohen, R. A., and Fong, P., 2004. Physiological responses of a bloom-forming green macroalga to short-term change in salinity, nutrients, and light help explain its ecological success. Estuaries, 27(2): 209-216. DOI:10.1007/BF02803378 (  0) 0) |

Edwards, D. M., Reed, R. H., and Stewart, W. D. R., 1988. Osmoacclimation in Enteromorpha intestinalis: Long-term effects of osmotic stress on organic solute accumulation. Marine Biology, 98: 467-476. DOI:10.1007/BF00391537 (  0) 0) |

Gao, G., Burgess, G., Wu, M., Wang, S., and Gao, K., 2020. Using macroalgae as biofuel: Current opportunities and challenges. Botanic Marina, 63: 355-371. DOI:10.1515/bot-2019-0065 (  0) 0) |

Gao, G., Clare, A. S., Rose, C., and Caldwell, G. S., 2018. Ulva rigida in the future ocean: Potential for carbon capture, bioremediation, and biomethane production. Global Change Biology Bioenergy, 10: 39-51. DOI:10.1111/gcbb.12465 (  0) 0) |

García-Sánchez, M. J., Fernández, J. A., and Niell, F. X., 1993. Biochemical and physiological responses of Gracilaria tenuistipitata under two different nitrogen treatments. Physiologia Plantarum, 88: 631-637. DOI:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1993.tb01382.x (  0) 0) |

Genty, B., Briantais, J. M., and Baker, N. R., 1989. The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 990: 87-92. DOI:10.1016/S0304-4165(89)80016-9 (  0) 0) |

He, W., and Qiu, Z., 2015. Analysis of typhoons affecting Zhaoqin City during 2004 to 2012. Modern Agricultural Science and Technology, 17: 3 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Henley, W. J., 1993. Measurement and interpretation of photosynthetic light-response curves in algae in the context of photoinhibition and diel changes. Journal of Phycology, 29: 729-739. DOI:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1993.00729.x (  0) 0) |

Huang, H., Lin, Q., Lin, Y., Jia, X., Li, C., and Wang, W., 2005. Spatial-temporal variation of large macrobenthic animals in cage culture sea area in Daya Bay. Chinese Environmental Science, 25: 412-416 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Huang, Y., Ye, C., Zhang, C., Zhang, B., Tang, C., Zheng, L., et al., 2022. Effects of nitrogen enrichment on growth, photosynthesis pigments and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of Ulva lactuca. International Core Journal of Engineering, 8(6): 332-341. (  0) 0) |

Huppe, H. C., Vanlerberghe, G. C., and Turpin, D. H., 1992. Evidence for activation of the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway during photosynthetic assimilation of NO3− but not NH4+ by a green alga. Plant Physiology, 100: 2096-2099. DOI:10.1104/pp.100.4.2096 (  0) 0) |

Kamer, K., and Fong, P., 2001. Nitrogen enrichment ameliorates the negative effects of reduced salinity on the green macroalga Enteromorpha intestinalis. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 218: 87-93. DOI:10.3354/meps218087 (  0) 0) |

Ke, Z., Tan, Y., Huang, L., Liu, J., Xiang, C., Zhao, C., et al., 2019. Significantly depleted N in suspended particulate organic matter indicating a strong influence of sewage loading in Daya Bay, China. Science of the Total Environment, 650: 759-768. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.076 (  0) 0) |

Kirst, G. O., 1989. Salinity tolerance of eukaryotic marine algae. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology, 41: 21-53. (  0) 0) |

Kojima, K., Oshita, M., Hayashi, H., and Nishiyama, Y., 2008. Role of elongation factor G in the inhibition of the synthesis of the D1 protein of photosystem Ⅱ under oxidative stress. In: Photosynthesis. Energy from the Sun. Allen, J. F., et al., eds. Springer, Dordrecht, 1313-1316.

(  0) 0) |

Ktari, L., 2017. Pharmacological potential of Ulva species: A valuable resource. Journal of Analysis and Pharmaceutical Research, 6(1): 00165. (  0) 0) |

Laurentin, A., and Edwards, C. A., 2003. A microtiter modification of the anthrone-sulfuric acid colorimetric assay for glucose-based carbohydrates. Analitical Biochemisty, 315: 143-145. DOI:10.1016/S0003-2697(02)00704-2 (  0) 0) |

Li, G., Wan, M., Mai, G., Huang, L., Tan, Y., and Zou, D., 2022. Comparative study on photophysiology of four macroalgae from the Zhongsha Atoll, with special reference to the effects of temperature rise. Journal of Tropical Oceanography, 41(3): 101-110 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Li, G., Wu, Y., and Gao, K., 2009. Effects of typhoon Kaemi on coastal phytoplankton assemblages in the South China Sea, with special reference to the effects of solar UV radiation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeoscience, 114: G040 29. (  0) 0) |

Li, H., Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Zheng, X., Liu, F., and Jiao, N., 2019. Nitrogen uptake and assimilation preferences of the main green tide alga Ulva prolifera in the Yellow Sea, China. Journal of Applied Phycology, 31: 625-635. (  0) 0) |

Li, Y., Wang, D., Xu, X., Gao, X., Sun, X., and Xu, N., 2017. Physiological responses of a green algae (Ulva prolifera) exposed to simulated acid rain and decreased salinity. Photosynthetica, 55(4): 623-629. (  0) 0) |

Liu, T.,, 2018. Atlas of Common Macroalgae in the Yellow Sea, Bohai Sea and East China Sea. China Ocean Press, Beijing, 1-25.

(  0) 0) |

Luo, M., and Liu, F., 2011. Salinity-induced oxidative stress and regulation of antioxidant defense system in the marine macroalga Ulva prolifera. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 409: 223-228. (  0) 0) |

Lum, K. K., Kim, J., and Lei, X., 2013. Dual potential of microalgae as a sustainable biofuel feedstock and animal feed. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 4: 53. (  0) 0) |

Luo, M., Liu, F., and Xu, Z., 2012. Growth and nutrient uptake capacity of two co-occurring species, Ulva prolifera and Ulva linza. Aquatic Botany, 100: 18-24. (  0) 0) |

Mantri, V. A., Singh, R. P., Bijo, A. J., Kumari, P., Reddy, C. R. K., and Jha, B., 2011. Differential response of varying salinity and temperature on zoospore induction, regeneration and daily growth rate in Ulva fasciata (Chlorophyta, Ulvales). Journal of Applied Phycology, 23: 243-250. (  0) 0) |

Roleda, M. Y., and Heesch, S., 2021. Chemical profiling of Ulva species for food applications: What is in a name?. Food Chemistry, 361: 130084. (  0) 0) |

Rybak, A. S., 2018. Species of Ulva (Ulvophyceae, Chlorophyta) as indicators of salinity. Ecological Indicators, 85: 253-261. (  0) 0) |

Schreiber, U., 2004. Pulse-amplitude-modulation (PAM) fluorometry and saturation pulse method: An overview. In: Chlorophyll a Fluorescence: A Signature of Photosynthesis. Papageorgiou G. C., ed., Springer, Dordrecht, 279-319.

(  0) 0) |

Shi, X., Zou, D., Hu, S., Mai, G., Ma, Z., and Li, G., 2021. Photosynthetic characteristics of three cohabitated macroalgae in the Daya Bay, and their responses to temperature rise. Plants, 10: 2441. (  0) 0) |

Smith, P. K., Krohn, R. I., Hermanson, G. T., Mallia, A. K., Gatner, F. H., Provenzano, M. D., et al., 1985. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Analitical Biochemisty, 150: 76-85. (  0) 0) |

Song, X., Huang, L., Zhang, J., Yin, J., Tan, Y., and Liu, S., 2004. Variation of phytoplankton biomass and primary production in Daya Bay during spring and summer. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 49(11-12): 1036-1044. (  0) 0) |

Song, X., Li, Y., Xiang, C., Su, X., Xu, G., Tan, M., et al., 2021. Nitrogen and phosphorus enrichments alter the dynamics of plankton community in Daya Bay, northern South China Sea: Results of mesocosm studies. Marine and Freshwater Research, 72(11): 1632-1642. (  0) 0) |

Wan, M., Wang, Z., Mai, G., Ma, Z., Xia, X., Tan, Y., et al., 2022. Photosynthetic characteristics of macroalgae Ulva fasciata and Sargassum thunbergii in the Daya Bay of the South China Sea, with special reference to the effects of light quality. Sustainability, 14: 8063. (  0) 0) |

Wang, Q., Dong, S., Tian, X., and Wang, F., 2007. The effects of circadian rhythms of fluctuating salinity on the growth and biochemical composition of Ulva pertusa. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 37(6): 911-915 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Wang, Y., Lou, Z., Sun, C., and Sun, S., 2008. Ecological environment changes in Daya Bay, China, from 1982 to 2004. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 56(11): 1871-1879. (  0) 0) |

Ware, C., Dijkstra, J. A., Mello, K., Stevens, A., O'Brien, B., and Ikedo, W., 2019. A novel three-dimensional analysis of functional architecture that describes the properties of macroalgae as a refuge. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 608: 93-103. (  0) 0) |

Wellburn, A. R., 1994. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of Plant Physiology, 144: 307-313. (  0) 0) |

Wells, E., Wilkinson, M., Wood, P., and Scanlan, C., 2007. The use of macroalgal species richness and composition on intertidal rocky seashores in the assessment of ecological quality under the European Water Framework Directive. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 55: 151-161. (  0) 0) |

Xiao, J., Zhang, X., Gao, C., Jiang, M., Li, R., Wang, Z., et al., 2016. Effect of temperature, salinity and irradiance on growth and photosynthesis of Ulva prolifera. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 35(10): 114-121. (  0) 0) |

Xu, G.,, 1989. Environments and Resources of Daya Bay. Anhui Press of Science and Technology, Hefei, 1-22 (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Yang, Y.,, 2016. Coastal Environmental Bioremediation and Seaweed Resource Utilization. Science Press, Beijing, 364pp (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Zhai, W., Dai, M., Cai, W. J., Wang, Y., and Wang, Z., 2005. High partial pressure of CO2 and its maintaining mechanism in a subtropical estuary: The Pearl River Estuary, China. Marine Chemistry, 93: 21-32. (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24