2) Weihai Fisheries Technology Extension Center, Weihai 264200, China;

3) College of Life Sciences, Yantai University, Yantai 264005, China;

4) College of Life Sciences, Ludong University, Yantai 264025, China;

5) School of Life Sciences, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200241, China

Cytokines can induce the migration of immune cells to the sites of infection or injury in the inflammatory response (Bagiolini, 1998). Cytokines comprise many regulatory molecules including interleukins, interferons and chemokines which function within the immune system. More and more evidences support the understanding that IL-17, a proinflammatory cytokine, plays an important role in the immune response against foreign pathogens and contributes to the pathology of many autoimmune and allergic conditions. IL-17 is the prototype member of IL-17 superfamily, and a T-cell-derived cytokine with proinflammatory activity, which is initially identified as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 8 (Rouvier et al., 1993; Yao et al., 1995). The IL-17 family of cytokines contain six members (IL-17A-F) and the IL-17 receptor family is composed of five members (IL-17RA-RE). IL-17 family function through their receptor IL-17R. A common feature among IL-17 cytokine family members is the conserved IL-17 domain which contains five spatially highly conserved cysteine residues involved in the formation of intrachain disulfide linkages. Such structure is similar to a common motif found in the growth factors such as transforming growth factor and nerve growth factor (Gerhardt et al., 2009; Pappu et al., 2010; Hymowitz, 2014). It is reported that IL-17 family and their receptor family have little homology to any other known cytokines and receptors, indicating that they have a distinct ligand-receptor signaling system that appears to be highly conservative among vertebrates (Kawaguchi et al., 2004; Gaffen, 2009; Wu et al., 2013).

IL-17 can strongly synergize with other cytokines and activate transcription factors such as NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light chain enhancer of activated B cells) and AP-1 (activator protein 1), placing it in the central inflammatory network. Additionally, IL-17 can stimulate epithelial, endothelial fibroblastic cells and macrophages, inducing other inflammatory cytokines (Kazunori et al., 2002; Gaffen, 2004; Iwakura et al., 2011). Therefore, IL-17 plays a key role in host defense against the bacterial and fungal infections. In addition, IL-17 can express in some autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease (Bessis and Boissier, 2001; Fujino et al., 2003; Nakae et al., 2003; Witowski et al., 2004; Langrish et al., 2005; Park et al., 2005; Aas, 2010).

IL-17 homologs have been isolated and characterized in many vertebrates, such as Homo sapiens, Gallus gallus, Danio rerio, Takifugu rubripes, Bos taurus and Mus musculus (Rouvier et al., 1993; Min and Lillehoi, 2002; Gunimaladevi et al., 2006; Riollet et al., 2006; Korenaga et al., 2010). In recent years, IL-17 genes in invertebrates have also been investigated with great interests. A number of IL-17 ligands have been found in genome database of invertebrates such as Ciona intestinalis, Caenorhabditis elegans, Branchiostoma floridae, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (Kono et al., 2011). However, only a few invertebrate IL-17 genes have been isolated and characterized. Roberts et al. (2008) isolated the IL-17 homolog from a Crassostrea gigas hemocyte cDNA library for the first time. Then the other five C. gigas IL-17 members (B-F) genes have also been identified by searching and analyzing the C. gigas genome (Li et al., 2014). In addition, the molecular cloning and functional characterization of IL-17 genes in Pinctada fucata have been reported (Wu et al., 2013).

Till now, the IL-17 gene in O. ocellatus has not yet been studied. O. ocellatus, affiliated to Octopodidae under the phylum Mollusca, is one of the most important economic species along the northern coast of China. O. ocellatus is susceptible to bacterial and viral infections. In order to improve its survival rate, the function of its immunity genes need be researched. In present study, we isolated and characterized IL-17 gene homolog from the O. ocellatus hemocytes cDNA library, which was named as OoIL-17. With quantitative real-time PCR, the relative expression level of OoIL-17 in a variety of healthy tissues and the hemocytes stimulated by gram-negative V. anguillarum and gram-positive M. luteus were determined. The aims of our study were 1) to isolate the full-length IL-17 homologous cDNA from O. ocellatus, 2) to investigate the tissue distribution and expression pattern of OoIL-17 at mRNA level in healthy body and upon bacterial challenge with V. anguillarum and M. luteus, and 3) to explore the potential functions of OoIL-17 in suppression of bacterial growth. These results will help us better understand the regulatory mechanism of OoIL-17 in the molluscan immune system.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Animals and BacteriaNatural healthy O. ocallatus specimens used in this study were obtained from a seafood market in Yantai, Shandong Province, China, with an average body weight of 36 g and body length of 15 cm. The octopuses were kept in seawater at room temperature with aeration for 7 days before they were used for the experiment.

V. anguillarum and M. luteus were used for the bacterial stimulation. V. anguillarum was inoculated into 2216E medium and cultured at 28℃ overnight. M. luteus was inoculated into LB medium and cultured at 37℃ overnight. The two bacteria were then collected by centrifugation at 10000 r min−1 for 10 min, respectively.

2.2 Healthy Tissue CollectionThe tissues, including muscle, mantle, hemocytes, hepatopancreas, stomach, gill, gonad and systemic heart, were collected from six individuals randomly. They were ground in liquid nitrogen and then resuspended in 1 mL TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlabad, CA, USA). The hemolymph was collected from the carpocerite using a syringe with a equal volume of anticoagulant (450 mmol L−1 NaCl, 0.1 mol L−1 glucose, 15 mmol L−1 sodium citrate and 10 mmol L−1 EDTA, pH 7.0) (Wei et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2015). Samples were immediately centrifuged at 4000 r min−1 at 4℃ for 5 min to harvest the hemocytes. Samples were then stored at −80℃ for further analysis.

2.3 RNA Extraction and Synthesis of cDNAThe total RNA was extracted from adult tissues and hemolymph using TRIzol reagent following the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Takara) to remove DNA contamination if any and then frozen at −80℃. The quality and quantity of the total RNA were evaluated through 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry with the NanoPhotometer Pearl.

Reverse transcription and cDNA synthesis were performed with 1 μg of total RNA and random hexamer primers by using M-MLV kit (Takara) following the manufacturer's protocol.

2.4 Molecular Isolation and Sequence Analysis of OoIL-17All plasmids in the octopus cDNA library were transferred into Trans5α competent cells, and the PCR product was sequenced by amplification with the universal primer (Table 1). The sequence of OoIL-17 was screened from the above sequencing results.

|

|

Table 1 Primers used in this study |

The cDNA and deduced amino acid sequences were analyzed using the BLAST algorithm (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) for homology alignment and similarity search. The protein domains were predicted with the simple modular architecture research tool (SMART) version 4.0 (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/), and the homology analysis was conducted using the Ident and Sim Analysis provided at http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms/. Multiple sequence alignment was performed with the Clustal W Multiple Alignment program. The presumed 3D structures were established using the SWISS-MODEL predication algorithm and displayed by PyMOL version 0.97. Phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the deduced amino acid sequences by the MrBayes method.

2.5 Bacterial StimulationOctopuses were immersed in bacterial suspension (1×107 CFU mL−1 V. anguillarum or M. luteus) or left unstimulated (Kong et al., 2010). Six individuals each group were randomly sampled at the indicated time points (0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h) after the challenge. Hemolymph was collected from the carpocerite using a syringe and mixed with an equal volume of anticoagulant (450 mmol L−1 NaCl, 0.1 mol L−1 glucose, 15 mmol L−1 sodium citrate and 10 mmol L−1 EDTA, pH 7.0). The mixture was then centrifuged at 3000 r min−1 and 4℃ for 10 min to harvest hemocytes.

2.6 Quantitative qRT-PCR of OoIL-17 in Different Tissues and at Different Times after ChallengeOoIL-17-Fw/Rv (Table 1, Amplification Efficiency = 0.99), the specific primer pair used in this experiment, was designed based on the sequence of OoIL-17 using Primer Premier 5. The relative expression of OoIL-17 was determined using β-actin (Table 1) as the reference. The qRT-PCR amplification was carried out on a Mastercycler ep realplex (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) in a 50 μL solution containing 25 μL 2 × SYBR Premix Ex TaqII (Tli RNaseH Plus), 1 μL 50 × ROX Reference Dye, 2 μL primer-Fw, 2 μL primer-Rv, 4 μL cDNA templates, 16 μL sterile water. The qRT-PCR amplification was performed with LightCycler 480 at 95℃ for 5 min pre-incubation, followed by 45 cycles of 95℃ for 15 s and 60℃ for 45 s. Finally, the melting curve was analyzed to detect single amplification. Fluorescent signal accumulation was recorded at the 60℃ 45 s phase during each cycle under the control of LightCycler 480 Software 1.5.

2.7 Bioinformatic Analysis and Phylogenetic Tree ReconstructionThe homologous nucleotide sequences of OoIL-17 and its deduced protein sequence were confirmed by a BLAST search against the databases of NCBI and Ensembl. Multiple sequence alignment was performed with ClustalX 2.1 and DNAMAN 7.0. The phylogenetic tree was constructed through MrBayes 3.2.3.

2.8 Statistical AnalysisThe relative mRNA abundance of OoIL-17 was calculated with 2−ΔΔCT method. Significance analysis was performed by t test. P < 0.05 indicates significant difference, and P < 0.01 indicates extremely significant difference.

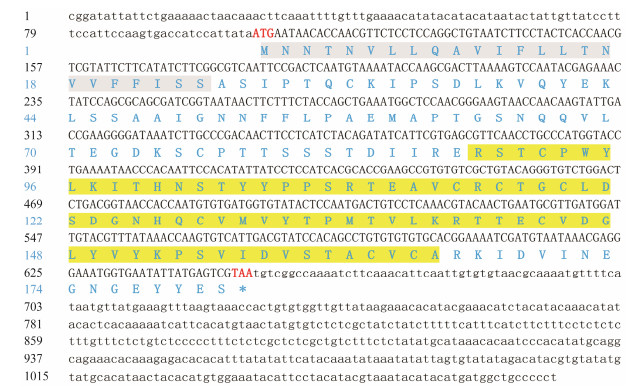

3 Results 3.1 Molecular Characterization of Full-Length OoIL-17 cDNAAfter sub-cloning, we obtained the full-length cDNA sequence of OoIL-17 (GenBank accession no. KX925 403). Furthermore, both 5'- and 3'-ends of the entire cDNA were cloned by RACE. The full-length OoIL-17 cDNA is 1083 bp in length, including a 5' untranslated region (UTR) of 104 bp, a 3' UTR of 433 bp and an open reading frame (ORF) of 546 bp. The ORF is predicted to encode a polypeptide of 181 amino acids with a theoretical isoelectric point of pH 5.35 and a predicted molecular mass of 19.824 kDa. Similar to those of other species, the predicted peptide of OoIL-17 contains a conserved IL-17 domain (amino acids 89–165) and a signal peptide (amino acids 1−24) (Fig. 1).

|

Fig. 1 Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of OoIL-17. Nucleotides are in black letters and amino acids are in blue letters. The UTRs are denoted in lowercase letters, and the ORF is denoted in uppercase letters. The initiation and termination codons are in red letters. The signal peptide is shaded with gray. The IL-17 domain is shaded by yellow. |

BLAST analysis revealed that the amino acid sequence of OoIL-17 is similar to IL-17 from other animals, e.g., 86% to that of Octopus bimaculoides (XP_014769326.1) and 35% to that of Homo sapiens (EAX04362.1). Multiple sequence alignment of OoIL-17 with other fourteen animal IL-17 finds six highly conserved cysteine residues at positions 31, 76, 92, 114, 116, 119, 128, 144, 162 and 164. The disulfide bridges are formed between positions 114 and 162 and 119 and 164, respectively, which are involved in stabilizing the canonical cysteine knot. A conserved phosphorylation site is found at position 90 (Fig. 2).

|

Fig. 2 Multiple alignment of full-length amino acid sequences of IL-17 from different species. Amino acids with different colors indicate various homology levels. The alignment was generated with DNAMAN program. The species and GenBank accession numbers or Ensembl numbers are as follows: Homo sapiens, EAX04362.1; Mus musculus, AAB05222.1; Gallus gallus, CAD38489.1; Lethenteron camtschaticum, BAF93839.1; Ciona intestinalis, NP_001123348.1; Apostichopus japonicas, PIK38783.1; Lingula anatine, XP_013408964.1; Octopus ocellatus, ATB53128.1; Octopus bimaculoides, XP_014769330.1; Pinctada fucata, AGC24392.1; Mytilus galloprovinclalis, AKM49935.1; Hyriopsis cumingii, AMR93991.1; Crassostrea virginica, XP_022344403.1; Haliotis rufescens, AGZ03660.1; Crassostrea gigas, ABO93467.1. |

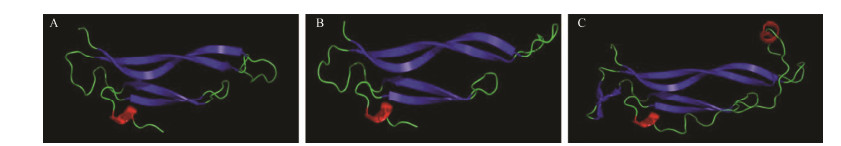

To further confirm their homology and better understand their potential functions in O. ocellatus, the 3D structure of OoIL-17 was established. The structure of OoIL-17 is almost identical to IL-17 in O. bimaculoides, including four β-strands and one α-helix. Both of them have one α-helix and two β-strands less than that of G. gallus (Fig. 3).

|

Fig. 3 The predicted 3D structure of IL-17 protein. (A), The 3D structure of IL-17 from O. ocellatus. (B), The 3D structure of IL-17 from O. bimaculoides. (C), The 3D structure of IL-17 from G. gallus. The blue part represents β-strand and the red part represents α-helix. The species and GenBank accession numbers or Ensembl numbers are as follows: Octopus ocellatus, ATB53128.1; Octopus bimaculoides, XP_014769330.1; Gallus gallus, CAD38489.1. |

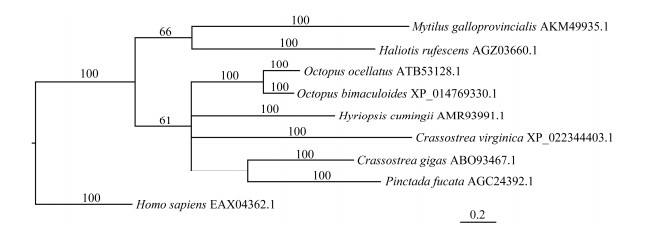

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using MrBayes method based on the encoding amino acids of OoIL-17 and IL-17 of other eight species including H. sapiens, P. fucata, C. gigas, Crassostrea virginica, Hyriopsis cumingii, O. bimaculoides, Haliotis rufescens, Mytilus galloprovinclalis, which was divided into invertebrates and vertebrates. OoIL-17 has the closest homology with O. bimaculoides, and is clustered with IL-17 of several shellfishes, including O. bimaculoides, C. gigas, H. cumingii, C. virginica and P. fucata. It is also clustered in invertebrates including M. galloprovincialis and H. rufescens. The H. sapiens IL-17 is used as outgroup (Fig. 4).

|

Fig. 4 Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of OoIL-17 with IL-17 of other invertebrates. A phylogram was constructed using MrBayes (mcmc = 200000 generations). |

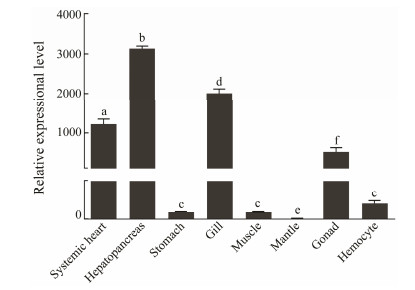

The expression of OoIL-17 in different tissues were detected using qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 5, the mRNA of OoIL-17 is constitutive at different levels in all the tissues tested in healthy O. ocellatus. The abundance of OoIL-17 mRNA is relatively higher in hepatopancreas, systemic heart and gill. OoIL-17 shows the highest expression in the hepatopancreas, which is extremely significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that in mantle. Additionally, the mRNA abundance in stomach, muscle, hemocytes and gonad is relatively lower, and the expression is the lowest in mantle.

|

Fig. 5 Relative expression of OoIL-17 in different tissues of O. ocellatus. qRT-PCR analysis was used to quantify OoIL-17 and β-actin mRNAs. The data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6). Columns with different letters show a significant difference (P < 0.05). |

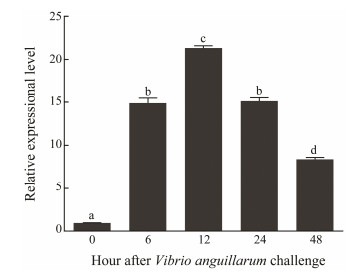

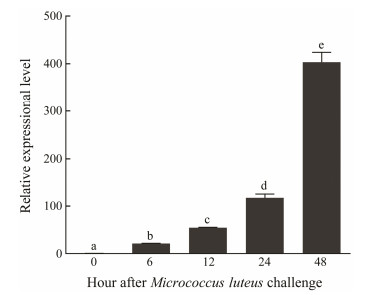

The temporal expression of OoIL-17 in O. ocellatus hemocytes after V. anguillarum or M. luteus challenge was monitored by qRT-PCR with β-actin as the reference. Both V. anguillarum and M. luteus up-regulated OoIL-17 mRNA abundance in hemocytes to different extents. In the V. anguillarum-stimulated group, the mRNA abundance of OoIL-17 is up-regulated, which peaked at 12 hps compared to that of the control. Subsequently, OoIL-17 mRNA abundance gradually decreased, but remained to be higher than that of control. The expression pattern of OoIL-17 stimulated by M. luteus is different from that by V. anguillarum. As shown in Fig. 7, the OoIL-17 expression level gradually increased, and maximized at 48 hps.

|

Fig. 6 Quantitative analysis of OoIL-17 expression in hemocytes after V. anguillarum challenge. qRT-PCR analysis was used to quantify OoIL-17 mRNA with β-actin as the reference. The data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6). Columns with different letters show a significant difference (P < 0.05). |

|

Fig. 7 Quantitative analysis of OoIL-17 expression in hemocytes after M. luteus challenge. qRT-PCR analysis was used to quantify OoIL-17 mRNA with β-actin as the reference. The data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6). Columns with different letters show a significant difference (P < 0.05). |

Invertebrates lack the adaptive immune system and they depend on innate immunity to defense against the pathogens. Innate immunity is the first line to protect hosts from pathogens and opportunistic microbial infections. Moreover, innate immunity involves an intracellular signaling pathway that leads to the transcription of soluble mediators such as cytokines (Chen et al., 2007). More and more researches have proved that IL-17 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that may play a central role in the inflammatory response in both vertebrates and invertebrates. The structure and function of IL-17 in vertebrates have been extensively studied in recent years. However, little is known about IL-17 in the invertebrates, especially in the mollusk.

In the present study, we isolated IL-17 from and analyzed its expression in O. ocellatus. Structural analysis revealed that it is similar with other animals' IL-17. OoIL-17 contains a typical mollusk IL-17 domain including four highly conserved cysteine residues Cys-116, -119, -162, -164 (Figs. 1 and 2), which are predicted to be involved in forming two disulfide bonds to stabilize the canonical cysteine knot that is similar to a motif exhibited in growth factors such as BMP and TGF-β (Moseley et al., 2003; Hymowitz, 2014). In addition to an IL-17 domain, the deduced IL-17 protein contains a predicted signal peptide with 24 amino acids (Fig. 1), indicating that it is a secreted protein via the Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum route (Pfeffer and Rothman, 1987). Multiple sequence alignment showed that OoIL-17 shares much higher similarity with other invertebrate IL-17 than vertebrate IL-17 (Fig. 2), indicating that OoIL-17 is a member of marine mollusk IL-17 family. In the phylogenetic analysis, OoIL-17 is firstly clustered with that of O. bimaculoides, and then clustered with other invertebrate IL-17. The 3D structures of IL-17 in O. ocellatus, O. bimaculoides and G. gallus also proved that the two different octopuses share a higher similarity and the IL-17 3D structure is highly conserved in both vertebrates and invertebrates (Fig. 3). Zhang et al. (2016) reported that H. cumingii IL-17 had a close relationship with IL-17 of M. galloprovincialis, P. fucata and C. gigas. Li et al. (2014) found that all invertebrate IL-17 genes belong to a single group. These results proved that all the invertebrate IL-17 genes are from one ancestral gene and the selection pressure resulted in the diversification of those genes within the invertebrate branch (Li et al., 2014). The results showed that OoIL-17 is a member of IL-17 family, and it may function in a similar way as its counterparts from other animals.

It is necessary to research the tissue-specific expression pattern of IL-17 in order to understand its functions. Like the tissue distribution of IL-17 genes in C. gigas, P. fucata, H. rufescens and H. cumingii (Roberts et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Valenzuela and Gallardo, 2014; Zhang et al., 2016), OoIL-17 transcripts were examined in all tested tissues. However, the expression level varied significantly among tissues and animals. The highest IL-17 expressions were observed in the gill of C. gigas (Roberts et al., 2008), the digestive gland of H. cumingii (Zhang et al., 2016), and the hemocytes of H. rufescens (Valenzuela and Gallardo, 2014). In this study, the hepatopancreas and gill showed the higher OoIL-17 expression than any other tissues examined. The wide tissue distribution of IL-17 transcript indicated that it may play an important role in immune defense against pathogens in mollusk. As hepatopancreas is an important immune-related organ in mollusk, the highest expression of OoIL-17 in hepatopancreas suggested that IL-17 may involve in the innate immune response in O. ocellatus. Considering the great exposure to aquatic environment surrounded by numerous bacteria and fungi, the relatively higher expression of OoIL-17 in the gill may explain the demand of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 in O. ocellatus.

More and more studies have concluded that IL-17 plays a critical role in the hosts' defense against external pathogens and is involved in the inflammatory response. The present study detected the immune response pattern of IL-17 in O. ocellatus stimulated by two pathogens, V. anguillarum and M. luteus, which can induce obvious expression of immune-related genes in marine mollusks (Kong et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2015). As hemocytes are believed to play a central role in innate immunity of invertebrates and the defense functions of various tissues are related to the presence of hemocytes (Roberts et al., 2008; Cerenius et al., 2010), the time-course gene expression of OoIL-17 was detected and analyzed in the hemocytes post bacterial challenges in O. ocellatus. In this study, Octopuses exposed to V. anguillarum have a rapid increase in OoIL-17 transcript abundance at 6 hps, and reach the highest at 12 hps, similar to the results of IL-17 expression in C. gigas after bacterial injection (Roberts et al., 2008), in P. fucata after LPS stimulation (Wu et al., 2013), and in H. rufescens challenged by V. anguillarum (Valenzuela and Gallardo, 2014), which suggested that IL-17 may respond at a early stage and regulate the expression of other immune-related genes upon pathogen exposure (Roberts et al., 2008). However, in the M. luteus-stimulated group, the OoIL-17 mRNA did not elevate obviously and was up-regulated gradually and reached the highest at 48 hps. This indicated that OoIL-17 expression in response to different bacterial infections is different, and it is more quickly triggered by V. anguillarum than by M. leteus. In addition, considering that O. ocellatus without shell protection is exposed to aquatic environment surrounded with different microorganisms and it has acute immune response, OoIL-17 may play an earlier role in the immune system. Toll and Imd pathways via NF-κB have been confirmed as the most important signal pathways in the immunity of vertebrates (Lemaitre and Hoffmann, 2007), and P. fucata IL-17 can activate NF-κB pathway in vitro by dual-luciferase reporter assays (Wu et al., 2013). Thus OoIL-17 can be involved in the innate immune response against foreign pathogens.

5 ConclusionsIn this study, an IL-17 homology from O. ocellatus was identified and analyzed. Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis revealed that OoIL-17 is a member of IL-17 family, and has the highly conserved cysteine residues similar with IL-17 of other invertebrates. As the expression analysis in the healthy tissues and the hemocytes stimulated by two bacteria indicated, OoIl-17 may play an important immunity function at the early stage of infection. This study will lay a solid foundation for further IL-17 as well as IL-17 family functional analysis in mollusks.

AcknowledgementsThis research was supported by the earmarked fund for the Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System (No. CARS-49), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2019BC052), and the Marine and Fisheries Science and Technology Innovation Program of Shandong Province (No. 2017YY04).

Aas, K., 2010. Treatment with a neutralizing anti-murine interleukin-17 antibody after the onset of collagen-induced arthritis reduces joint inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion. Arthritis Rheum, 50(2): 650-659. (  0) 0) |

Bagiolini, M., 1998. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature, 392(6676): 565-568. DOI:10.1038/33340 (  0) 0) |

Bessis, N. and Boissier, M. C., 2001. Novel pro-inflammatory interleukins: potential therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine Revue Du Rhumatisme, 68(6): 477-481. (  0) 0) |

Cerenius, L., Jiravanichpaisal, P., Liu, H. and Soderhall, I., 2010. Crustacean immunity. Oxygen Transport to Tissue XXXIII, 708(92): 239-259. (  0) 0) |

Chen, S., Chinnaswamy, A. and Biswas, S. K., 2007. Cell interaction knowledgebase: An online database for innate immune cells, cytokines and chemokines. Silico Biology, 7(6): 569-574. (  0) 0) |

Fujino, S., Andoh, A., Bamba, S., Ogawa, A., Hata, K. and Araki, Y., 2003. Increased expression of interleukin 17 in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut, 52(1): 65-70. DOI:10.1136/gut.52.1.65 (  0) 0) |

Gaffen, S. L., 2004. Biology of recently discovered cytokines: Interleukin-17-α unique inflammatory cytokine with roles in bone biology and arthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 6(6): 240. (  0) 0) |

Gaffen, S. L., 2009. Structure and signaling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nature Reviews Immunology, 9(11): 556-567. (  0) 0) |

Gerhardt, S., Abbott, W. M., Hargreaves, D., Pauptit, R. A., Davies, R. A. and Needham, M. R., 2009. Structure of IL-17A in complex with a potent, fully human neutralizing antibody. Journal of Molecular Biology, 394: 905-921. DOI:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.008 (  0) 0) |

Gunimaladevi, I., Savan, R. and Sakai, M., 2006. Identification, cloning and characterization of interleukin-17 and its family from zebrafish. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 21(4): 393-403. (  0) 0) |

Hymowitz, S. G., 2014. IL-17s adopt a cystine knot fold: Structure and activity of a novel cytokine, IL-17F, and implications for receptor binding. EMBO Journal, 20(19): 5332-5341. (  0) 0) |

Iwakura, Y., Ishigame, H., Saijo, S. and Nakae, S., 2011. Functional specialization of interleukin-17 family members. Immunity, 34(2): 149-162. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.012 (  0) 0) |

Kawaguchi, M., Adachi, M., Oda, N., Kokubu, F. and Huang, S. K., 2004. IL-17 cytokine family. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology, 114(6): 1265-1273. (  0) 0) |

Kazunori, H., Akira, A., Mitsue, S., Sanae, F., Shigeki, B. and Yoshio, A., 2002. IL-17 stimulates inflammatory responses via nf-kappab and map kinase pathways in human colonic myofibroblasts. American Journal of Physiology–Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 282(6): 10-35. (  0) 0) |

Kong, P. F., Zhang, H. and Wang, L. L., 2010. AiC1qDC-1, a novel gC1q-domain-containing protein from bay scallop Argopecten irradians with fungi agglutinating activity. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 34(8): 837-846. (  0) 0) |

Kono, T., Korenaga, H. and Sakai, M., 2011. Genomics of fish IL-17 ligand and receptors: A review. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 31(5): 635-6431. (  0) 0) |

Korenaga, H., Kono, T. and Sakai, M., 2010. Isolation of seven IL-17 family genes from the Japanese pufferfish Takifugu rubripes. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 28(5): 809-818. (  0) 0) |

Langrish, C. L., Chen, Y., Blumenschein, W. M., Mattson, J., Basham, B. and Sedgwick, J. D., 2005. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 201(2): 233-240. DOI:10.1084/jem.20041257 (  0) 0) |

Lemaitre, B. and Hoffmann, J., 2007. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annual Review of Immunology, 25(1): 697-743. (  0) 0) |

Li, J., Zhang, Y. and Zhang, Y., 2014. Genomic characterization and expression analysis of five novel IL-17 genes in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 40(2): 455-465. (  0) 0) |

Min, W. and Lillehoj, H. S., 2002. Isolation and characterization of chicken interleukin-17 cDNA. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research, 22(11): 1123-1128. (  0) 0) |

Moseley, T. A., Haudenschild, D. R. and Rose, L., 2003. Interleukin-17 family and IL-17 receptors. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews, 14(2): 155-174. (  0) 0) |

Nakae, S., Nambu, A., Sudo, K. and Iwakura, Y., 2003. Suppression of immune induction of collagen-induced arthritis in IL-17-deficient mice. Journal of Immunology, 171(11): 6173-6177. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6173 (  0) 0) |

Pappu, R., Ramirez-Carrozzi, V., Ota, N., Ouyang, W. and Hu, Y., 2010. The IL-17 family cytokines in immunity and disease. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 30(2): 185-195. DOI:10.1007/s10875-010-9369-6 (  0) 0) |

Park, H., Li, Z., Yang, X. O., Chang, S. H., Nurieva, R. and Wang, Y. H., 2005. A distinct lineage of cd4 t cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nature Immunology, 6(11): 1133-1141. DOI:10.1038/ni1261 (  0) 0) |

Pfeffer, S. R. and Rothman, J. E., 1987. Biosynthetic protein transport and sorting by the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 56(1): 829-852. (  0) 0) |

Riollet, C., Mutuel, D. and Duonorcérutti, M., 2006. Determination and characterization of bovine interleukin-17 cDNA. Journal of Interferon and Cytokine Research, 26(3): 141-149. DOI:10.1089/jir.2006.26.141 (  0) 0) |

Roberts, S., Gueguen, Y. and Lorgeril, J. D., 2008. Rapid accumulation of an interleukin 17 homolog transcript in Crassostrea gigas hemocytes following bacterial exposure. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 32(9): 1099-1104. (  0) 0) |

Rouvier, E., Luciani, M. F., Mattéi, M. G., Denizot, F. and Golstein, P., 1993. Ctla-8, cloned from an activated T cell, bearing au-rich messenger RNA instability sequences, and homologous to a Herpesvirus saimiri gene. Journal of Immunology, 150(12): 5445-5456. (  0) 0) |

Valenzuela, M. V. and Gallardo, E. C., 2014. Molecular cloning and expression of IRAK-4, IL-17 and I-κB genes in Haliotis rufescens challenged with Vibrio anguillarum. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 36(2): 503-509. (  0) 0) |

Wei, X., Xu, J. and Yang, J., 2015. Involvement of a Serpin serine protease inhibitor (OoSerpin) from mollusc Octopus ocellatus, in antibacterial response. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 42(1): 79-87. (  0) 0) |

Wei, X., Yang, J. and Yang, J., 2012. A four-domain Kunitztype proteinase inhibitor from Solen grandis is implicated in immune response. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 33(6): 1276-1284. (  0) 0) |

Witowski, J., Ksiazek, K. and Jörres, A., 2004. Interleukin-17: A mediator of inflammatory responses. Cellular & Molecular Life Sciences Cmls, 61(5): 567-579. (  0) 0) |

Wu, S. Z., Huang, X. D. and Li, Q., 2013. Interleukin-17 in pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata): molecular cloning and functional characterization. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 34(5): 1050-1056. (  0) 0) |

Yao, Z., Fanslow, W. C., Seldin, M. F., Rousseau, A. M., Painter, S. L. and Comeau, M. R., 1995. Herpesvirus saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity, 187(9): 811-821. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, R., Wang, M. and Xia, N., 2016. Cloning and analysis of gene expression of interleukin-17 homolog in triangle-shell pearl mussel, Hyriopsis cumingii, during pearl sac formation. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 52: 151-156. (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18