2) School of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne NE3 1QD, UK;

3) Institute of Oceanography, Zhejiang Geological Institute of China Metallurgical Geology Bureau, Quzhou 324000, China

Since 2007, the annual bloom of the seaweed Ulva prolifera has become a serious problem that induced severe green tide disasters in the southern Yellow Sea (SOA, 2016). A number of studies have successfully detected green algae occurrences using satellite instruments, including the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrora-diometer (MODIS; Hu and He, 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2017), Huan Jing-1 (HJ-1; Xing and Hu, 2016), and the Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI; Son et al., 2012, 2015). Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and floating algae index (FAI) were proposed to detect green algae outbreaks by using MODIS data from the Yellow Sea (Hu and He 2008; Hu, 2009). FAI is also available from Landsat 4-8, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite/NPOESS Preparatory Project (VIIRS/NPP), and other sensors which analyze red bands, near-infrared reflectance (NIR), and short-wave infrared reflectance (SWIR). However, this index cannot be obtained from HJ-1 and GOCI data due to their lack of the SWIR band. For the HJ-1 satellite with a spatial resolution of 30 m and a temporal coverage of 2 days, the Index of Virtual-Baseline Floating Algae Height (VB-FAH) was proposed to measure the height of NIR reflectance (Xing and Hu, 2016), using the green and red bands as the baseline. For the GOCI satellite, the index of floating green algae for GOCI (IGAG) was developed to monitor the change of Ulva prolifera (Son et al., 2012, 2015), with a spatial resolution of 500 m and temporal coverage of eight hours per day.

Accuracy in green algae detection based on the satellite images is highly depended on the method of atmospheric correction. Due to their high NIR reflectance, green algae can mistakenly be detected as clouds (Lee et al., 2010; Son et al., 2012; Lou and Hu, 2014), turbid water (Lou and Hu, 2014), or high aerosol optical thickness (Son et al., 2012), consequently leading to an overestimation of water signals from the blue to NIR bands (Son et al., 2012). If ocean reflectance values were retrieved by using atmospheric correction data of the NIR or SWIR bands, green algae could potentially be masked as blank pixels (Hu, 2009; Hu et al., 2017). Although an atmospheric correction was applied by using maritime aerosol (M90) and coastal aerosol (C50) parameters, the resultant uncertainty was 0.4% – 10% for MODIS-FAI. This uncertainty resulted in a biomass estimation error of 0.036 – 0.09 kg m−2 for FAI less than 0.2, and 0.0008 – 2.56 kg m−2 for FAI more than 0.2 (Hu et al., 2017). However, the Environment for Visualizing Images/Quick Atmospheric Correction (ENVI/ QUAC) model, an in-scene approach, is a promising technique that uses the retrieval of surface reflectance images for green algae detection, as it requires only approximate specification of sensor central wavelengths and their radiometric calibration (Jiang et al., 2014).

To date, the inversion of green algae biomass has only been reported in a study that simulated the relationship between FAI and biomass using MODIS data in the souern Yellow Sea (Hu et al., 2017). In their work annual dynamic growth of the green algae biomass was also demonstrated. However, critical data on daytime biomass changes on an hourly scale and its controlling factors have not been discussed. In this work, the GOCI is used to monitor green algae biomass. A new algorithm to get the Biomass Index of Green Algae for GOCI (BIGAG) is developed, based partly on previous work by Son et al. (2015), Xing and Hu (2016), Xiao et al. (2017), and Hu et al. (2017) to resolve its problems associated with the absence of the SWIR band.

2 Materials and MethodsIn order to construct an improved algorithm to get BIGAG, we first selected the 865 nm, 745 nm and 555 nm bands for atmospheric correction based on the ENVI/ QUAC method. Next, a simulation model, developed based on biomass measurements and the satellite-derived biomass index of green algae from Hu et al. (2017), was used to calculate green algae biomass from our BIGAG data. Finally, the derived biomass data were related with photosynthetically available radiation (PAR), temperature, and tidal levels to improve our understanding of daily biomass dynamic changes and their controlling factors.

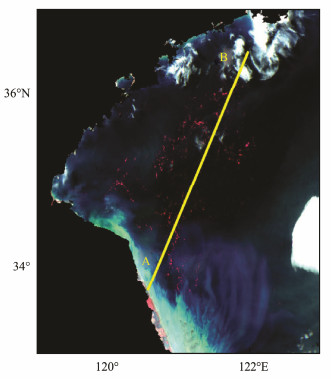

2.1 GOCI DataGOCI L1B data during severe green algae blooms on June 17 and 25, 2016 (SOA, 2016), were retrieved from the Korea Ocean Satellite Center (KOSC) website (http://kosc.kiost.ac.kr/). The Rayleigh corrected reflectance (Rrc) data in different bands were calculated by using GOCI Data Progressing Software (GDPS) (Ryu et al., 2012; Lou and Hu, 2014). Fig. 1 shows an enhanced surf remote sensing reflectance (Rsurf) data in RGB (864), with red color indicating the position of the green tide in the southern Yellow Sea.

|

Fig. 1 The enhanced RGB (864) image at UTC 07:28 on June 17, 2016 in the southern Yellow Sea. The transect AB is marked by the yellow line in image, where Rrc and Rsurf data are extracted and compared. |

Pyranometer data were retrieved from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) website (https://aeronet.gsfc.nasa.gov). In this paper, the Pyranometer data under the level 1.5 were screened to remove anomalies. Values for photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) were calculated by using the following equation:

| $PAR = \eta \times Py, $ | (1) |

where η is a fraction of 0.368 (Delgado-Bonal, 2017), denoting the ratio of PAR to the total solar emitted radiation Py, measured by the pyranometer at the Yonsei University site and retrieved from AERONET website. Since there is a one-hour time difference between the university site and the research area, the duration of retrieved data is therefore set between UTC 01:00 and 08:59. Hourly averages of the solar fluxes during the data acquisition period at the Yonsei University site were applied to calculate PAR, which is used to compare with the green algae biomass.

2.3 SST DataSea surface temperature (SST) L2 data were retrieved from the Advanced Very High-Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR), MODIS (Koner and Harris, 2016) and VIIRS/ NPP via the websites http://kosc.kordi.re.kr and https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov, respectively. Due to different resolution and transit times of these satellites, data were calculated at maximum (90%), minimum (10%), and average values (Table 1). In addition, green algae with high NIR can be wrongly interpreted as clouds (Remer et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2010; Son et al., 2012) when L2 products were processed. To reduce blank effects of clouds and green algae, average SST was therefore calculated over a large sea surface area (34°–37°N, 119°–122°E).

|

|

Table 1 Satellite identifier and some parameters for SST products from multiple satellites |

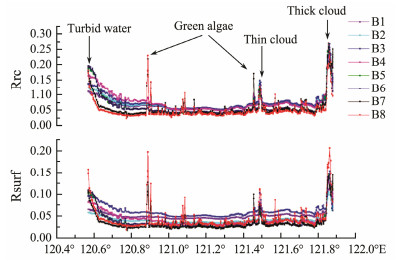

Rayleigh corrected reflectance data have been used to detect green algae and trace their movement by using bands of 555 nm, 660 nm, and 745 nm (Son et al., 2012, 2015), but adverse impacts on green algae detection because of different aerosol types and optical thicknesses can not be overlooked. Hu et al. (2017) proposed additional atmospheric correction with two aerosol types should be applied to retrieve credible Rsurf values from MODIS data. Here we used the ENVI/QUAC method to deduce Rsurf values from GOCI data (Module, 2009; Bernstein et al., 2012), and selected the Rsurf values larger than 0.07 at 412 nm to remove cloud effects. In comparison with Rrc data, the resolution in distinguishing green algae was significantly improved (Fig. 2)

|

Fig. 2 Comparison between Rrc and Rsurf data along the AB transect shown in Fig. 1 at UTC 07:28 on June 17, 2016. Rrc is Rayleigh corrected reflectance by GDPS software, and Rsurf is atmospheric corrected reflectance by ENVI/ QUAC method. B1, 412 nm; B2, 443 nm; B3, 490 nm; B4, 555 nm; B5, 660 nm; B6, 680 nm; B7, 745 nm; B8, 865 nm. |

The FAI was first proposed by Hu (2009) to measure NIR heights by using red and SWIR bands as the baseline:

| $FAI = {R_{{\rm{NIR}}}} - {R_{{\rm{RED}}}} - ({R_{{\rm{SWIR}}}} - {R_{{\rm{RED}}}}) \times\\ \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; ({\lambda _{{\rm{NIR}}}} - {\lambda _{{\rm{RED}}}})/({\lambda _{{\rm{SWIR}}}} - {\lambda _{{\rm{RED}}}}), $ | (2) |

where R is sea surface reflectance, λ is wavelength, and the subscripts RED, NIR, and SWIR represent the red, near infrared, and shortwave infrared bands, respectively.

The FAI is based on the SWIR band which is unavailable in GOCI images. NDVI and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) are not considered because they are affected by high chlorophyll-a and suspended materials. The IGAG is a type of Rrc data which is not processed by total atmospheric correction. Given these limitations, the ENVI/QUAC method was chosen to conduct atmospheric corrections.

Green algae can be identified by using reflectance values at 500 – 600 nm, 700 – 900 nm, and 1000 – 1100 nm because of their intimate correlations (Hu et al., 2017). Since the GOCI image lacks the 1000 – 1100 nm band, the 555 nm, 745 nm, and 865 nm bands were selected to calculate BIGAG:

| $BIGAG = {R_{745}} - {R_{555}} - ({R_{865}} - {R_{555}}) \times\\ \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;({\lambda _{745}} - {\lambda _{555}})/({\lambda _{865}} - {\lambda _{555}}), $ | (3) |

where R is sea surface reflectance and λ is wavelength.

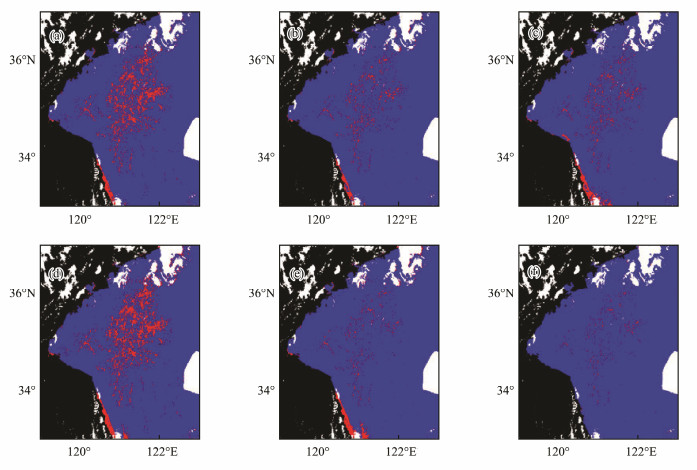

The indexes of IGAG, VB-FAI, and BIGAG were calculated from GOCI data on June 17, 2016, then they were atmospherically corrected by Rayleigh or ENVI/QUAC method (Fig. 3). It is apparent that the green algae distribution areas identified by the indexes VB-FAI, and BIGAG following Rayleigh correction are much larger than those by the ENVI/QUAC correction. These differences may result from the impacts of variable aerosol types and optical thicknesses ignored in the Rayleigh correction method. The density of green algae in the nearshore waters along the Subei coast (southeast shoreline in Fig. 3) was seemingly quite high except for that in Fig. 3f. However, this is considered to result from very high suspended sediment concentrations in the Subei coastal waters which IGAG and VB-FAI methods can not account for. For the offshore waters, the green algae distribution areas identified by the index IGAG were much larger than those by the indexes VB-FAI and BIGAG, due to the decrease of detecting ability for the IGAG method as the concentration of suspended matter increased (Son et al., 2012). In short, two steps of GOCI data processing procedures involving ENVI/QUAC correction and the index BIGAG are suggested for effectively detecting green algae distribution in the southern Yellow Sea and other similar settings with high concentrations of suspended matter.

|

Fig. 3 Comparison of green algae distribution detecting by different atmospheric correction and identifying indexes based on GOCI data at UTC 07:28 on June 17, 2016. Red pixels represent green algae identified by the IGAG > 0 (a, d), VB-FAI > 0.025 (b, e), and BIGAG > 0 (c, f) after Rrc (top row) and ENVI/QUAC (bottom row) atmospheric corrections, respectively. White, blue, and black pixel denote cloud, water, and land, respectively. |

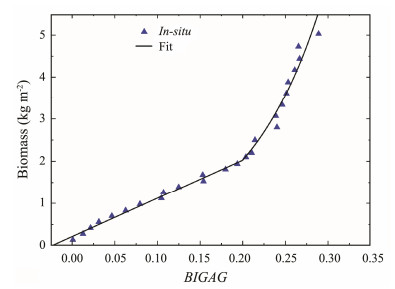

Two step-wise correlations are clearly shown in the scatter plot of green algae biomass vs. the index BIGAG, cited from Hu et al. 2017 (Fig. 4). Biomass increases slowly as BIGAG increases for values less than 0.2 kg m−2, with a linear fitting equation:

|

Fig. 4 The relationship between the green algae biomass and the dimensionless BIGAG (original data from Hu et al., 2017). |

| $Y = 9.0504X + 0.2165, $ | (4) |

where Y is biomass, X is BIGAG, and R2 = 0.9891. Biomass increases rapidly as BIGAG increases above 0.2 kg m−2, defined by an exponential fitting equation:

| $Y = 0.2056{{\rm{e}}^{11.384X}} + 0.020, $ | (5) |

where Y is biomass, X is BIGAG, and R2 = 0.9281.

The green algae biomass was calculated by using these two equations with BIGAG data on June 17 and 25, 2016. The results indicate that the number of pixels with BIGAG values larger than 0.2 is less than 300, representing only 0.1% of the green algae area. The reconstructed biomass ranged from 452 kt to 15363 kt on June 17, 2016, and from 784 kt to 1380 kt on June 25, 2016 in the study area.

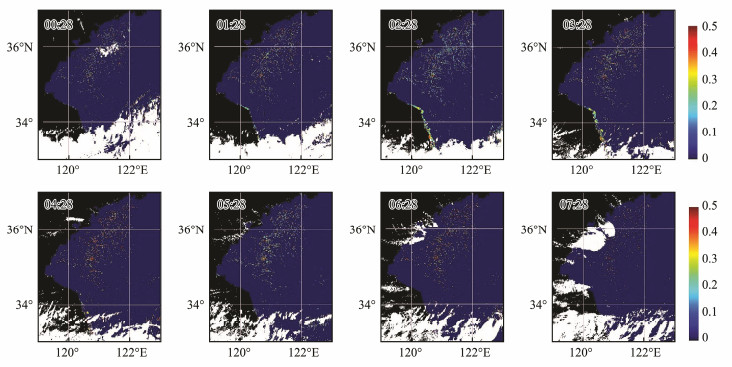

3 ResultsHourly changes in the green algae biomass were calculated based on its relationship with the BIGAG as shown in Fig. 4 on June 25, 2016 (Fig. 5). The green algae were mainly distributed in the northern part of the south Yellow Sea. The distribution area increased from 2125 km2 at UTC 00:28 to 3782 km2 at UTC 02:28 (a 77% increase), and then decreased to 1212 km2 at UTC 07:28. The area with the green algae biomass larger than 0.5 kg m−2 also reached its maximum of 612 km2 at UTC 02:28. It is interesting to note that similar daytime biomass variations in phytoplankton were also reported in Taihu Lake to the southwest of the Yellow sea (Xu et al., 2016), but they differ from the red tide on May 29 and 30 in the East China Sea (Lou and Hu, 2014). In addition to hourly variations, green algae biomass has been reported to change significantly over monthly and seasonal scales (Lee et al., 2012).

|

Fig. 5 Hourly variations in the green algae biomass (kg m−2) on June 25, 2016 from UTC 00:28 to 07:28. |

The growth rate of green algae biomass is usually expressed as the dynamic growth rate. We calculated the dynamic growth rate (α; Table 2) based on the hourly biomass data derived from the index BIGAG on June 25, 2016 using the following the formula:

|

|

Table 2 The growth rate (α), velocity (V), and parameter of biomass change (PBC) for the green algae bloom on June 25, 2016 |

| $\alpha (h + 1) = \frac{{B(h + 1) - B(h)}}{{B(h)}}, $ | (6) |

where B(h) and B(h+1) are the biomass at hour h and the following hour, respectively.

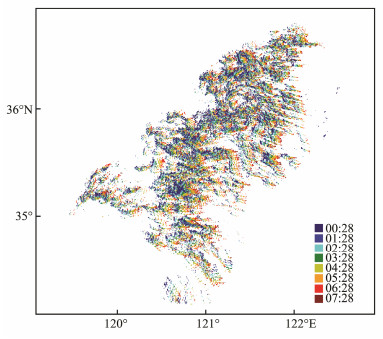

The patches of green algae were defined based on their densities. Green algae movements were monitored by using hourly spatial variations of single patch (Fig. 6). Mean movement velocity was calculated by the following equation that involved the moving distance of the geographical centers for each patch during one period and the subsequent period:

|

Fig. 6 The distribution and movement trajectory of green algae on June 25, 2016 from UTC 00:28 to 07:28. |

| $\bar V = \frac{{\sqrt {{{(\overline {X(h + 1)} - \overline {X(h)})}^2} + {{(\overline {Y(h + 1)} - \overline {Y(h)})}^2}} }}{{(h + 1) - h}}, $ | (7) |

where

The hourly change of biomass, that is the parameter of biomass change (PBC; Table 2), is defined as the ratio of the dynamic growth rate to the hourly movement velocity (dimensionless):

| $PBC = \alpha /\frac{{{\rm{d}}(x, y)}}{{{\rm{d}}t}} = \alpha /V, $ | (8) |

where x is longitude, y is latitude, and V is the average hourly movement velocity.

The results show that on June 25, 2016, the green algae moved eastward with an average velocity of 3.32 km h−1 from UTC 00:28 to 07:28 (Fig. 6; Table 2). Maximum and minimum velocities are 5.60 km h−1 during UTC 06:28 to 07:28 and 1.12 km h−1 during UTC 01:28 to 02:28, respectively (Table 2). The green algae distribution and movement trajectory displayed as a triangular shape defined by three corners (37°N, 122°E), (35°N, 119°E) and (34°N, 121°E). Most of green algae moved to the east or northeast, but at the southern part of study area, they tended to move to the southeast.

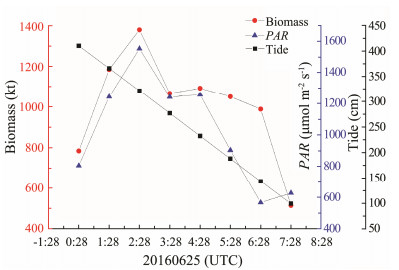

4 Discussion 4.1 Factors Affecting BiomassThe synchronous change between green algae biomass and PAR on a daily scale indicates that PAR is a key factor affecting green algae bloom (Xu et al., 2016; Pliego-Cortés et al., 2017; Fig. 7). Biomass was also observed to decrease as tidal level dropped after UTC 2:28, and the general eastward movement trajectory of green algae was consistent with the ebb current directions (Figs. 6, 7). Both PAR and tidal variations can exert significant control on green algae biomass distribution. Ebb tides tend to mix nearshore water masses with abundant green algae with an offshore water mass with less algae, resulting in the dilution effect (Lou and Hu, 2014). The pathway of green algae movement in the south Yellow Sea was also reported to be controlled by shelf circulation and wind direction (Son et al., 2015), following the detachment of the Subei coastal area (Liu et al., 2009, 2010).

|

Fig. 7 Hourly changes in biomass, PAR, and tidal level on June 25, 2016. Tidal data were retrieved from the Qingdao Harbor via http://app.cnss.com.cn. |

Sea surface temperature (SST), obtained from AVHRR, MODIS, and NPP data, was also one of the factors affecting the biomass. It can be seen that the SST varied between 20℃ and 26℃ from UTC 02:00 to 08:00 on June 25, 2016 (Table 2), which has been reported to be a suitable temperature range to support green algae bloom (Fan et al., 2013; Son et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2016). However, slight hourly changes in the average SST were not found to covary with marked hourly changes in the green algae biomass. In other words, SST may not play an important role in the biomass distribution on an hourly scale.

In addition, large spatiotemporal variations in the green algae biomass were also reported to be well correlated with the nutritional element abundance and types (Fan et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016), and trace element abundance (Shi et al., 2015; Dao and Beardall, 2016; Gao et al., 2017). Their potential influence on daily biomass changes has not been well documented, and is beyond the scope of this study.

4.2 Dynamic Changes in the Green Algae BiomassThe parameter of biomass change, PBC, is very crucial for monitoring spatiotemporal variations of green algae in the Yellow Sea by satellites (Table 2). Its values range from −0.01 t m−1 to 0.1 t m−1 (Table 2). A negative PBC implies that the water conditions inclined to suppress green algae growth, whereas a positive PBC indicates the setting is favorable for green algae bloom. Thus, PBC is considered to be more useful than the growth rate for an early warning indicator of green algae bloom.

5 ConclusionsMacroalgae blooms of Ulva prolifera (green tide) in the southern Yellow Sea were detected and tracked for the first time over an hourly scale by using the Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI). Two steps of GOCI data processing, involving ENVI/QUAC atmospheric correction and the identification based on the index BIGAG, gave the best estimation of green algae distributions in the southern Yellow Sea, and can potentially be applied to similar settings with high suspended loads. The green algae biomass was calculated from BIGAG data by using the fitting formula derived from the relationships between biomass measurements and satellite biomass indexes proposed by Hu et al. (2017) in the southern Yellow Sea. Hourly biomass variations were highly correlated with Photosynthetically Available Radiation (PAR) and tidal phases, but less with sea surface temperature variation on a daily scale. A new parameter of biomass change, PBC was proposed by dividing the biomass growth rate by the movement velocity to monitor high spatiotemporal variations of green algae. It could provide a near real-time index to assess and forecast green tide development in the southern Yellow Sea.

AcknowledgementsThis work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41776052, 41476031), the Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Marine Geology (No. MG20190104), and the China Scholarship Council (No. CSC201906260052). We thank KOSC, AERONET for providing the GOCI data and NOAA-SST, Pyranometer data respectively. We are grateful to the MODIS-SST and NPP-SST by NASA. We would also like to thank ShengHsiang (Carlo) Wang from Prof. Lin's group in AERONET Liulin site.

Bernstein, L. S., Jin, X. M., Gregor, B. and Adler-Golden, S. M., 2012. Quick atmospheric correction code: Algorithm description and recent upgrades. Optical Engineering, 51: 111719. (  0) 0) |

Dao, L. H. T. and Beardall, J., 2016. Effects of lead on growth, photosynthetic characteristics and production of reactive oxygen species of two freshwater green algae. Chemosphere, 147: 420-429. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.12.117 (  0) 0) |

Delgado-Bonal, A., 2017. Entropy of radiation: The unseen side of light. Scientific Reports, 7: 1642. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-01622-6 (  0) 0) |

Fan, X., Xu, D., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Cao, S., Mou, S. L. and Ye, N., 2014. The effect of nutrient concentrations, nutrient ratios and temperature on photosynthesis and nutrient uptake by Ulva prolifera: Implications for the explosion in green tides. Journal of Applied Phycology, 26: 537-544. DOI:10.1007/s10811-013-0054-z (  0) 0) |

Gao, G., Liu, Y., Li, X., Feng, Z., Xu, Z., Wu, H. and Xu, J., 2017. Expected CO2-induced ocean acidification modulates copper toxicity in the green tide alga Ulva prolifera. Environ-mental and Experimental Botany, 135: 63-72. DOI:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.12.007 (  0) 0) |

Hu, C. M., 2009. A novel ocean color index to detect floating algae in the global oceans. Remote Sensing of Environment, 113: 2118-2129. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2009.05.012 (  0) 0) |

Hu, C. M. and He, M. X., 2008. Origin and offshore extent of floating algae in Olympic sailing area. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 89: 302-303. DOI:10.1029/2008EO330002 (  0) 0) |

Hu, L. M., Hu, C. M. and Xia, H. E., 2017. Remote estimation of biomass of Ulva prolifera macroalgae in the Yellow Sea. Remote Sensing of Environment, 192: 217-227. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2017.01.037 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, B. B., Zhang, X. Y., Du, Y., and Huang, D. S., 2014. Establishing monitoring model of Haze event with multi-satel-lite data and application – A case: Yangtze River Delta. International Symposium on Optoelectronic Technology and Application 2014: Optics Remote Sensing and Technology and Applications. Beijing, 92991C.

(  0) 0) |

Koner, P. K. and Harris, A., 2016. Sea surface temperature retrieval from MODIS radiances using truncated total least squares with multiple channels and parameters. Remote Sensing, 8(9): 725-741. DOI:10.3390/rs8090725 (  0) 0) |

Lee, J., Kim, J., Song, C. H., Ryu, J. H., Ahn, Y. H. and Song, C. K., 2010. Algorithm for retrieval of aerosol optical properties over the ocean from the Geostationary Ocean Color Imager. Remote Sensing of Environment, 114: 1077-1088. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2009.12.021 (  0) 0) |

Lee, Z. P., Jiang, M., Davis, C., Pahlevan, N., Ahn, Y. H. and Ma, R., 2012. Impact of multiple satellite ocean color samplings in a day on assessing phytoplankton dynamics. Ocean Science Journal, 47: 323-329. DOI:10.1007/s12601-012-0031-5 (  0) 0) |

Li, H., Zhang, Y., Han, X., Shi, X., Rivkin, R. B. and Legendre, L., 2016. Growth responses of Ulva prolifera to inorganic and organic nutrients: Implications for macroalgal blooms in the southern Yellow Sea, China. Scientific Reports, 6: 26498. DOI:10.1038/srep26498 (  0) 0) |

Liu, D. Y., Keesing, J. K., Dong, Z., Zhen, Y., Di, B., Shi, Y. J., Fearns, P. and Shi, P., 2010. Recurrence of the worldos largest green-tide in 2009 in Yellow Sea, China: Porphyra yezoensis aquaculture rafts confirmed as nursery for macroalgal blooms. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 60: 1423-1432. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.05.015 (  0) 0) |

Liu, D. Y., Keesing, J. K., Xing, Q. and Shi, P., 2009. Worldos largest macroalgal bloom caused by expansion of seaweed aquaculture in China. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 58: 888-895. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.01.013 (  0) 0) |

Lou, X. L. and Hu, C. M., 2014. Diurnal changes of a harmful algal bloom in the East China Sea: Observation from GOCI. Remote Sensing of Environment, 140: 562-572. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2013.09.031 (  0) 0) |

Module, F. L. A. A. S. H., 2009. Atmospheric Correction Module: Quac and Flaash Useros Guide. ITT Visual Information Solutions Publishers, New York, 6-38.

(  0) 0) |

Pliego-Cortés, H., Caamal-Fuentes, E., Montero-Muñoz, J., Freile-Pelegrín, Y. and Robledo, D., 2017. Growth, biochemical and antioxidant content of Rhodymenia pseudopalmata (Rho-dymeniales, Rhodophyta) cultivated under salinity and irradiance treatments. Journal of Applied Phycology, 29: 2595-2603. DOI:10.1007/s10811-017-1085-7 (  0) 0) |

Remer, L. A., Kaufman, Y. J., Tanré, D., Mattoo, S., Chu, D. A., Martins, J. V., Li, R. R., Ichoku, C., Levy, R. C., Kleidman, R. G., Eck, T. F., Vermote, E. and Holben, B. N., 2005. The MODIS aerosol algorithm, products, and validation. Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 62: 947-973. DOI:10.1175/JAS3385.1 (  0) 0) |

Ryu, J. H., Han, H. J., Cho, S., Park, Y. J. and Ahn, Y. H., 2012. Overview of Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI) and GOCI Data Processing System (GDPS). Ocean Science Journal, 47: 223-233. DOI:10.1007/s12601-012-0024-4 (  0) 0) |

SOA, 2016. The public report on marine disaster of China. http://www.soa.gov.cn.

(  0) 0) |

Shi, R. J., Li, G., Zhou, L., Liu, J. and Tan, Y., 2015. The increasing aluminum content affects the growth, cellular chlorophyll a and oxidation stress of cyanobacteria Synechococcus sp. WH7803. Oceanological and Hydrobiological Studies, 44: 343-351. DOI:10.1515/ohs-2015-0033 (  0) 0) |

Son, Y. B., Choi, B. J., Kim, Y. H. and Park, Y. G., 2015. Tracing floating green algae blooms in the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea using GOCI satellite data and Lagrangian transport simulations. Remote Sensing of Environment, 156: 21-33. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2014.09.024 (  0) 0) |

Son, Y. B., Min, J. E. and Ryu, J. H., 2012. Detecting massive green algae (Ulva prolifera) blooms in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea using Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI) data. Ocean Science Journal, 47: 359-375. (  0) 0) |

Xiao, J., Zhang, X., Gao, C., Xiao, J., Zhang, X. H., Gao, C. L., Jiang, M. J., Li, R. X., Wang, Z. L., Li, Y., Fan, S. L. and Zhang, X. L., 2016. Effect of temperature, salinity and irradiance on growth and photosynthesis of Ulva prolifera. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 35: 114-121. DOI:10.1007/s13131-016-0891-0 (  0) 0) |

Xiao, Y., Zhang, J. and Cui, T., 2017. High-precision extraction of nearshore green tides using satellite remote sensing data of the Yellow Sea, China. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 38: 1626-1641. DOI:10.1080/01431161.2017.1286056 (  0) 0) |

Xing, Q. and Hu, C. M., 2016. Mapping macroalgal blooms in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea using HJ-1 and Landsat data: Application of a virtual baseline reflectance height technique. Remote Sensing of Environment, 178: 113-126. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2016.02.065 (  0) 0) |

Xu, D., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Fan, X., Miao, Y., Ye, N. H. and Zhuang, Z. M., 2016. Responses of photosynthesis and nitrogen assimilation in the green-tide macroalga Ulva prolifera to desiccation. Marine Biology, 163: 9. DOI:10.1007/s00227-015-2806-6 (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19