Kinesin superfamily proteins, most of them work as motors for anterograde transport along the microtubules to their plus ends, have been identified and characterized in various living species. So far, 45 kinds of kinesins have been found in mice. Based on phylogenetic analysis, Hirokawa and Tanaka (2015) classified kinesin proteins (KIFs) into 15 subfamilies, from kinesin I to kinesin-14B. Kinesin Ⅱ contains the heterotrimeric complex KIF3 and the homodimer complex KIF17s (Hirokawa and Takemura, 2004). The KIF3 motor is one of the most abundantly and ubiquitously expressed KIFs recently found in the testes. It is composed of KIF3A, either KIF3B or KIF3C, and an associated protein, KAP3 (reviewed by Hirokawa, 2010). The KIF3A and KIF3C heterodimer is usually in the brain, retina, and lungs (Yang and Goldstein, 1998). In contrast, KIF3A and KIF3B often form stable dimer with each other in different tissues and organs, especially in the testes (Henson et al., 1997; De et al., 2001; Berezuk and Schroer, 2004).

It is well known that KIF3A/3B carry different cargoes in highly polarized cells, such as fodrin-associated vesicles in neurons, melanosomese in pigment cells, and rod opsins in photoreceptor cells (Takeda et al., 2000; Gross et al., 2002). In addition, KIF3A/3B have been implicated in the plus-end-directed movement of late endosomes, lysosomes (Brown et al., 2010), Golgi/ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) membranes (Bot et al., 1998), Golgi-derived vesicles, and other proteins or protein complexes (Nishimura et al., 2004; Duangtum et al., 2011). Recent reports on photoreceptor cilia support the idea that KIF3A and KIF3B motors are required for rod opsin transport and cell viability, and play important roles in the formation of cilia and flagella in many species and cell types (Lopes et al., 2010; Trivedi et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2012). Such kinesins act indirectly on microtubule dynamics through the transport of specific factors (reviewed by Hirokawa and Noda, 2008; Hirokawa and Tanaka, 2015). It has been reported that the binding between the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumour suppressor and microtubules was enhanced by KIF3A (Lolkema et al., 2007). In Sand dollar sperm, heterotrimeric KIF3 firstly localized in the midpiece and flagellum (Henson et al., 1997). Several papers have recently reported on the expression of KIF3A and KIF3B genes and their localization during spermiogenesis in crustaceans (Lu et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2017), cephalopods (Wang et al., 2010; Dang et al., 2012), reptiles (Hu et al., 2012), and mammals (Lehti et al., 2013). Surprisingly, the latest knockout studies on KIF3A revealed the importance of KIF3 for nuclear deformation and flagella lengthening (Lehti et al., 2013).

Spermiogenesis is a complex process during the last phase of spermatogenesis, in which the spermatid changes into a mature sperm through early, middle, and late stages (O'donnell and O'bryan, 2014). This last phase includes the processes of nucleus deformation, chromatin condensation, and flagella lengthening (You et al., 2001; Fu et al., 2016). Notably, spermiogenesis is subject to gene regulation, and kinesin superfamily genes are one class of these regulatory genes. In recent years, research on kinesin genes related to reproduction in mammals has progressed rapidly, which in turn has enriched our knowledge about sperm vitality, fertilization, and development. Low abundance of kif2a mRNA in abnormal male semen was detected in clinical semen parameters using real-time quantitative PCR (Zhou et al., 2013). In rat spermatids, KLC3 (known as kinesin light chain 3) is able to bind to the mitochondrial sheath, and contributes to the transport of mitochondria from the cell periphery to the midpiece, which indicates that KLC3 plays a role in the development of midpiece (Zhang et al., 2012). A previous study also stated that KLC3 is highly synthesized in rat testes and accumulates in midpiece (Junco et al., 2001). Research has demonstrated that KIFC1 interacts with the microtubular sheath for chromatin condensation and the elongation of the nucleus (Yang et al., 2006).

Larimichthys crocea is a marine fish with high commercial value in China, to which people have attached a great importance in terms of research on its reproduction and development (Chen et al., 2010). Gonad development, spermatogenesis, and the ultrastructural features of spermatozoa of L. crocea have also been studied (You et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2014). However, the molecular mechanisms involved in spermiogenesis are still not well understood. According to previous studies, we hypothesize that kinesin-Ⅱ genes also function in spermiogenesis in L. crocea. In this study, we cloned kif3a/3b for the first time and described in detail the characteristics of the testes at different developmental stages through histomorphological observation. The spatiotemporal locations of kif3a and kif3b encoded proteins were also studied. The main aim of this work was to provide a detailed examination of the spatiotemporal mRNA abundance patterns of kif3a/3b during spermiogenesis of L. crocea.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 AnimalsExperimental L. crocea were collected from cages in Xiangshan Harbor, Ningbo, China. The fish fries were bred in early March, 2014. In total, 8 patches of healthy individuals were sampled from August, 2014 to June, 2015 (Table 1). Firstly, a total of 40, 30, 30 fish were separately sampled in the middle of August, October, and December of 2014, respectively. Their average body length was about 13 cm, 17 cm and 18 cm, respectively. Their average body weight was about 34 g, 83 g, and 113 g, respectively. Then 30, 30, 20, 10 fish were sampled from the middle of March to June of 2015 at the same location, respectively. Their average body length was 21 cm, 22 cm, 24 cm, and 24 cm, respectively. Their average body weight was about 149 g, 162 g, 215 g, and 242 g, respectively. Other 40 L. crocea individuals were randomly taken at 2015 generation at the end of June, 2015, whose body length and body weight were about 7 cm and 6 g. Finally, according to histological characteristics, the whole male individuals were selected to sampling.

|

|

Table 1 Testis development of L. crocea of the 2014 generation in the first sexual cycle |

In order to understand the gonad development stage of L. crocea, the testes were observed by paraffin section firstly. After the samples were dissected, the testes were subsequently removed and weighed. For light microscopy, the tissues were fixed in Bouin's fluid for about 24 hours, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and later immersed in paraffin. The serial sections were cut at a thickness of about 7 μm. These sections were examined using an light microscope (Olympus BX51) after HE staining.

2.3 Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)The ultrastructural change of testes during spermatogenesis of L. crocea was observed under transmission electron microscope. Testes were cut into small pieces and fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde at 4℃ for 2 h, and then post-fixed for 1–2 h in 1% osmium tetroxide. After being dehydrated, they were subsequently transferred to ascending concentrations of acetone, and finally embedded in Epon 812 for 1 h. Sections were cut with an ultramicrotome (LKB-α), and then stained with uranyl acetate for 40 min and counterstained with lead citrate for 1 min. For later examination, we used a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1200EX).

2.4 RNA Extraction and Reverse TranscriptionBased on manufacturer's instructions and established protocols in our laboratory (Zhang et al., 2017), we extracted the total RNA from six different tissues including gill, testis, liver, muscle, kidney and spleen, and the testes at four different developmental stages (Ⅱ–Ⅴ). The cryopreserved tissues that were frozen at −80℃ overnight were quickly grinded in mortars, and then were sequentially treated with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, USA), chloroform, isopropanol and 75% ethanol. Finally, the precipitated RNA was dissolved in 30 μL DEPC-treated H2O and detected the quality and concentration by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometer. At last the eligible RNAs were stored at −80℃ for reverse transcriptions.

The ordinary reverse transcription and RACE reverse transcription were performed using PrimeScript® RT Reagent Kit (Takara, China) and Smart RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, USA), respectively. For realtime quantitative PCR, the first strand cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript® RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, China).

2.5 Full-Length cDNA CloningAccording to the highly conserved regions of KIF3A/ 3B homologous proteins from various species, the first pair of degenerate primers F1/R1 (Table 2) and other primers were designed. Degenerate PCR was performed to get cDNA fragments with the following program: initial denaturation at 94℃ for 5 min, then 30 cycles (denaturation at 94℃ for 30 s, annealing at about 55℃ for 30 s, and extension at 72℃ for 30 s), and a finally extension at 72℃ for 10 min.

|

|

Table 2 All kif3a and kif3b primers used in the study |

In order to obtain the ends of kif3a/3b cDNA, nested-PCR was adopted. The specific primers (Table 2) were designed by Primer 5.0 software, and UPM and NUP were separately used as outer and inner primers in the two rounds of nested-PCR. The first round PCR was run according to the manufacturer's protocol. After the first round PCR, the amplified products were diluted 30 multiples to be used as the template of the second round PCR, which was run as follows: 94℃ for 5 min, 30 cycles of 94℃ for 30 s, 68℃ for 30 s, and 72℃ for 2 min, and a final extension of 72℃ for 10 min. Subsequently, the PCR products were separated using agarose electrophoresis and the bands were visualized by Gelview. The anticipated objective straps were extracted and purified using Quick-type DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Bioteke, Beijing, China). The purified fragments were ligated into the PMD-18Tvector (Takara, Dalian, China) and then transformed into competent cells (Escherichia coli DH5α), and sequenced by Beijing Genomics Institute (Beijing, China). Eventually, the full-length cDNA was established by combining the 5' RACE fragment, the originally derived fragment, and the 3' RACE fragment.

2.6 Sequence Analysis, Multiple Alignments and Phylogenetic AnalysisThe corresponding amino acid sequence was deduced online using ORF Finder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder). The secondary and tertiary structures of KIF3A/ 3B proteins were predicted using UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/) and I-TASSER (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/ITASSER/), respectively. Moreover, the chemical composition and physicochemical properties of KIF3A/ 3B proteins were analyzed using ExPASY ProtParam tool (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). All sequences used in the analysis were listed in Table 3. For the conservation analysis of KIF3A/3B proteins, the multiple sequence alignment of homogenous proteins from different species was performed using Vector NT 11.5. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA 5.1.

|

|

Table 3 List of the GenBank accession numbers of KIF3A/3B homologous sequences |

In the experiment, the expressions of kif3a and kif3b in six types of tissues (testis in stage Ⅳ, liver, gill, muscle, kidney and spleen) were measured by RT-PCR using β-actin as the reference gene. As shown in Table 2, the specific primers were as follows: KIF3A-S-F/R (5'-GGG ACCATAACAGTGAACAA-3', 5'-ACGGGTTAGTTTA GAGTTCCT-3'); KIF3B-S-F/R (5'-ATTGCTGAACAG AAACGACGAG-3', 5'-TTCTTGCCTGTTCTTGGTCG-3'). After PCR, the relative abundances of kif3a and kif3b mRNA in six tissues were analyzed using Quantity 1 software of Bio-RAP.

2.8 Real-Time PCR Analysis in Testes at Different Developmental StagesTo investigate the relative amounts of Kif3a/3b cDNA during testis development, a total of twelve different fish at four successive stages from stage Ⅱ to stage Ⅴ were selected, 3 fish individuals each stage and three parallel assays each fish individual. We performed the real-time PCR using SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM Ⅱ (Tli RNaseH Plus) in Bio-rad CFX96 Real-time PCR System, and β-actin was used as the reference. Two pairs of specific primers were used: KIF3A-T-F/R (5'-AGCAGTGCCA GAACTCCGA-3', 5'-CTTGTGTCACCCTCTGCCTTG-3'); KIF3B-T-F/R (5'-GCCAGTGAACTCCCCAAAATC-3', 5'-CCATTGAAGCCAAAAAGAACTG-3'). At the end, the abundances of Kif3a and Kif3b mRNA were calculated with 2−ΔΔCt method. All quantitative data were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). SPSS 17.0 (USA) was used for statistical analyses, and statistical significant difference of expressions was defined as P < 0.05.

2.9 Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH)FISH analysis was performed following the established protocol (Braubach et al., 2017). Sample treatment of the fresh L. crocea testes and preparation of frozen section were implemented with the methods established early (Zhang et al., 2017). The antisense probes were designed with Primer 5 and synthesized by Generay Biotechnology. For kif3a, the probe was labeled by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) at 5'-terminal (5'-TTCTC TATCATCTCCTGGTATTCCT), and for kif3b, the probe was labeled by Cy3 at 5'-terminal (5'-CGGCTCCTGAT ACTCTTTTGTG).

Frozen sections were placed in a non-enzymatic environment at room temperature (RT) for 10 minutes, then covered with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes and rinsed twice with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 10 min each time. Then the sections were covered with 1×PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20 for 30 min, followed by hybridization at 55℃ for 16 h in a lucifugal humidified chamber with 1 μmol L−1 probes in 1×PBS. After hybridization, the slides were washed with 1×PBS containing 0.1% TritonX-100 at 55℃ and then stained with DAPI (Beyotime) for 5 min, followed by anti-fluorescence quenching agent and blocking. Finally, stained tissue sections were observed under a Confocal Laser-scanning Microscope (LSM880) (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

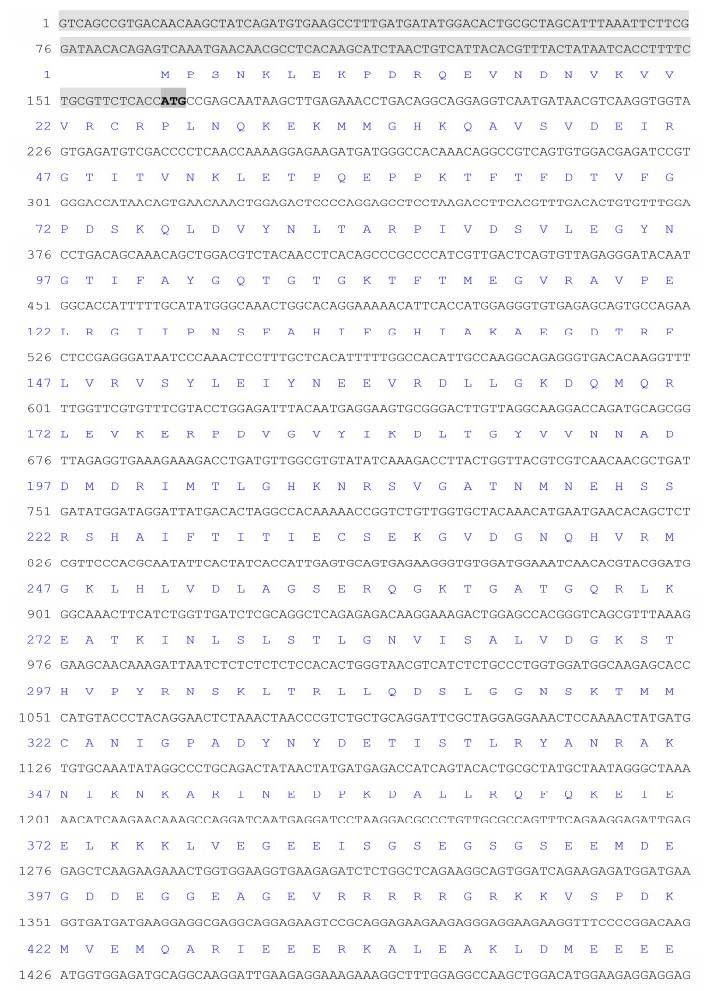

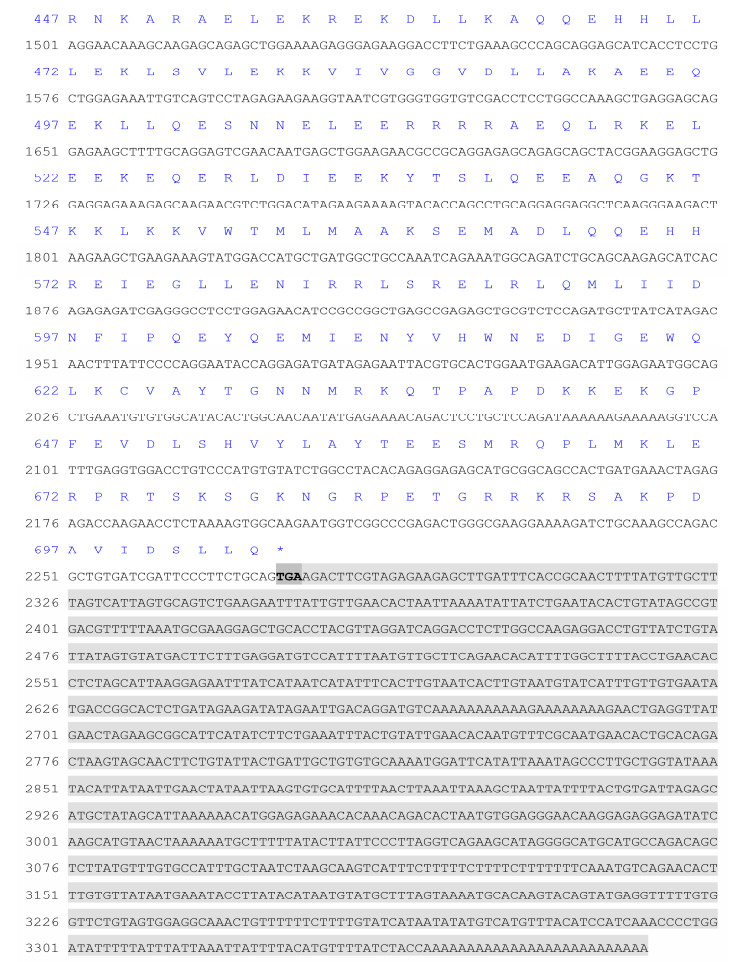

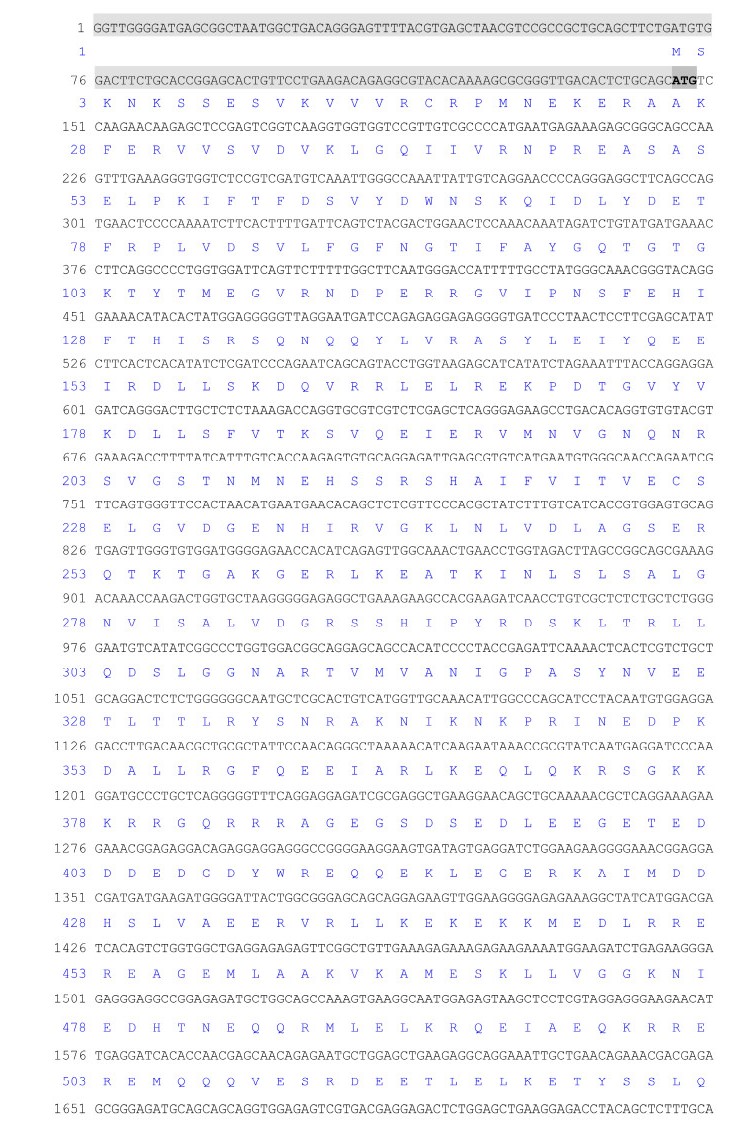

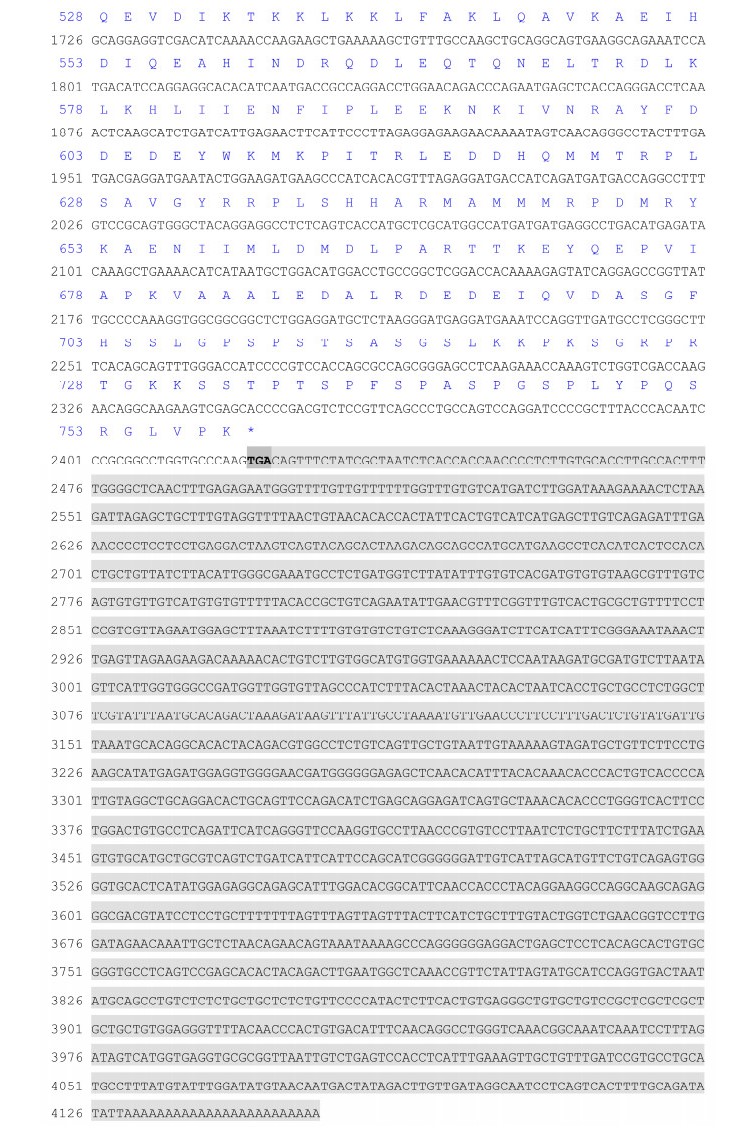

3 Results 3.1 Sequence Analysis and Protein Structure of KIF3A/3BThe complete kif3a cDNA from L. crocea was 3367 bp, including a 162 bp 5'-UTR, a 1090 bp 3'-UTR, and a 2115 bp open reading frame (ORF) encoding a 704 aa (amino acid) polypeptide (Fig. 1). The kif3b cDNA was 4153 bp, including a 145 bp 5'-UTR, a 1, 731 bp 3'-UTR, and a 2277 bp ORF encoding a 758-aa polypeptide (Fig. 2). Using the protein sequence alignment tools of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the similarity of KIF3A and KIF3B was determined to be about 52%. The N-terminal domains were found to be highly similar. An online analysis of KIF3A/3B using ExPASy Protparam showed that the molecular weight of two proteins was approximately 80.4 kDa and 86.7 kDa, respectively, with a predicted isoelectric point of 6.51 and 8.09, respectively. Compared with other amino acids, the content of glutamic acid in KIF3A/3B was the highest, about 11.9% and 10.4%, respectively.

|

Fig. 1A Kif3a full-length cDNA and amino acid sequence in L. crocea. The complete cDNA is 3367 bp in length, including a 162 bp 5' untranslated region, a 1090 bp 3' untranslated region and a 2115 bp open reading frame that encodes a polypeptide of 704 amino acids (blue sign). The shaded area represents 5'- and 3'-UTR, respectively. The initiation codon (ATG) and termination codon (TGA) (*) are set to bold. |

|

Fig. 1B Same as those in Fig. 1A. |

|

Fig. 2A Kif3b full-length cDNA and amino acid sequence in L. crocea. The complete cDNA is 4153 bp in length, including a 145 bp 5' untranslated region, a 1731 bp 3' untranslated region and a 2277 bp open reading frame that encodes a polypeptide of 758 amino acids (blue sign). The shaded area represents 5'- and 3'-UTR, respectively. The initiation codon (ATG) and termination codon (TGA) (*) are set to bold. |

|

Fig. 2B Same as those in Fig. 2A. |

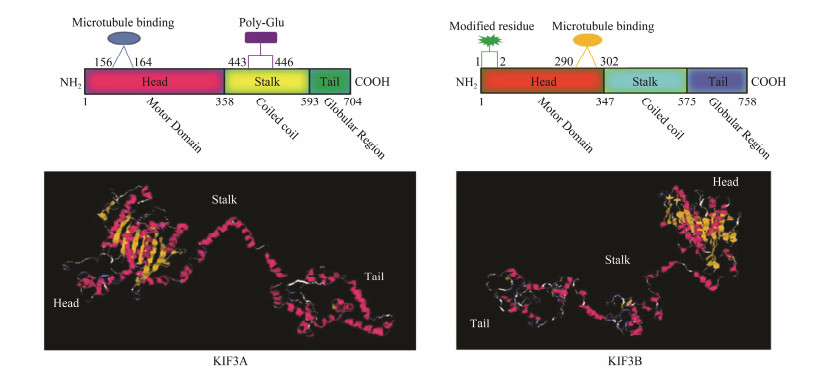

The prediction of KIF3A/3B structures using the UniProt and I-TASSER websites revealed that their secondary structures contain three domains, a motor domain, a coiled coil domain, and a tail domain (Figs. 3A and B). The N-terminus of KIF3A, 1–357 amino acids, forms a special head where a microtubule binding site (156–164 aa) and ATP binding sites (101–110, 220–224, and 254– 258 aa) exist. The 358–593 aa constitutes a spiral neck with a glutamate (Glu)-enriched zone (443–446 aa). The 594–704 aa forms the C-terminus, also known as the tail, that can carry different cargo molecules, in which a serine (S) (692 aa) is possibly phosphorylated. As for KIF3B, the N-terminus, stalk region, and C-terminus are separately composed of 1–346 aa, 347–575 aa, and 576–758 aa, respectively. Likewise, the motor domain is responsible for ATP-hydrolysis (12–18, 90–95, 97–104, and 232–253 aa) and microtubule binding (290–302 aa). Moreover, methionine (M) and serine (S), situated separately at the first and second aa position of the globular head, are potentially acetylated. In addition, the characteristics of the predicted tertiary structures of KIF3A/3B (Figs. 3C and D) are consistent with those of the secondary structure.

|

Fig. 3 Structural prediction of KIF3A/3B proteins in L. crocea. (A) Putative diagram of KIF3A secondary structure. (B) Putative diagram of KIF3B secondary structure. (C) Putative diagram of KIF3A tertiary structure. 3D source: http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/output/S238448/dm9o9e/. (D) Putative diagram of KIF3B tertiary structure. 3D source: http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/output/S238873/m6uwww/. |

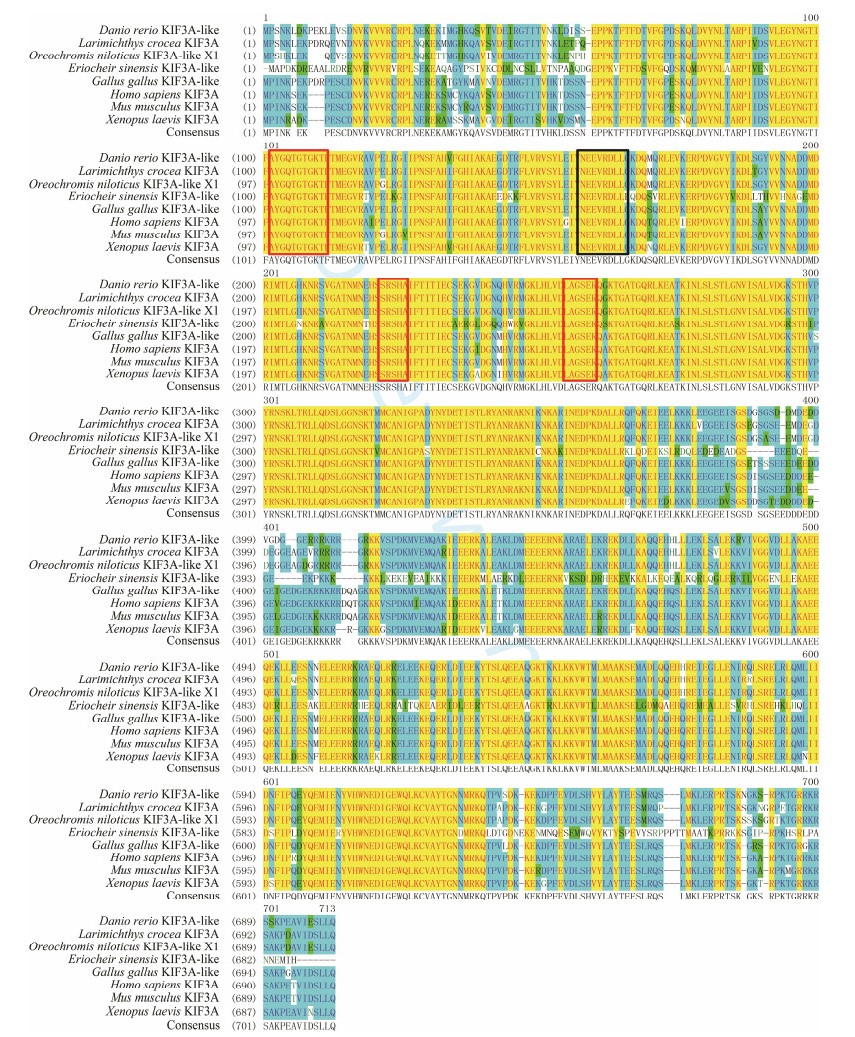

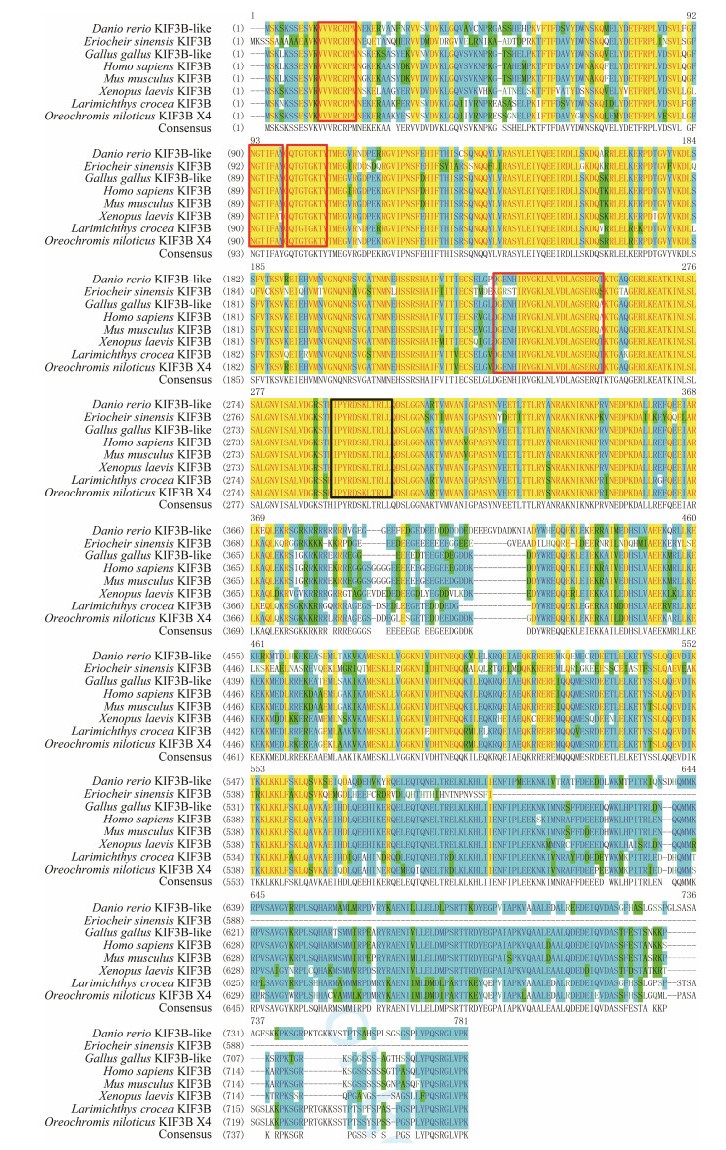

The homologous protein alignment of the deduced KIF3A/ 3B of L. crocea and other species revealed that these proteins were significantly conserved. The similarity between L. crocea KIF3A and Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Gallua gallus, Danio rerio, Oreochromis niloticus, Xenopus laevis, and Eriocheir sinensis KIF3A were 90%, 90%, 90%, 93%, 96%, 89%, and 66%, respectively. As in other KIFs, the encoded polypeptide of KIF3A of L. crocea also possessed three putative ATP-binding motifs (AYGQTGTGKT, SSRSH, and LAGSE) and one microtubule-binding motif (YNEEVRDLL) in the motor domain (Fig. 4). From the alignment of KIF3B, we found that KIF3B was 77%, 77%, 79%, 83%, 89%, 75%, and 65% similar with that of H. sapiens, M. musculus, G. gallus, D. rerio, O. niloticus, X. laevis, and E. sinensis, respectively. Similarly, in the motor domain of KIF3B, four assumed ATP-binding sites (VVVRCRP, NGTIFA, GQTGTGKT, and DGENHIRVGKLNLVDLAGSERQ) and one microtubule-binding site (HIPYRDSKLTRLL) were observed (Fig. 5).

|

Fig. 4 Multiple sequence alignment of KIF3A homologous proteins. Red frames indicate the putative ATP binding sites (AYGQTGTGKT, SSRSH, and LAGSE). Black frame indicates the putative microtubule binding site (YNEEVRDLL). |

|

Fig. 5 Multiple sequence alignment of KIF3B homologous proteins. Red frames indicate the putative ATP binding sites (VVVRCRP, NGTIFA, GQTGTGKT, and DGENHIRVGKLNLVDLAGSERQ). Black frame indicates the putative microtubule binding site (HIPYRDSKLTRLL). |

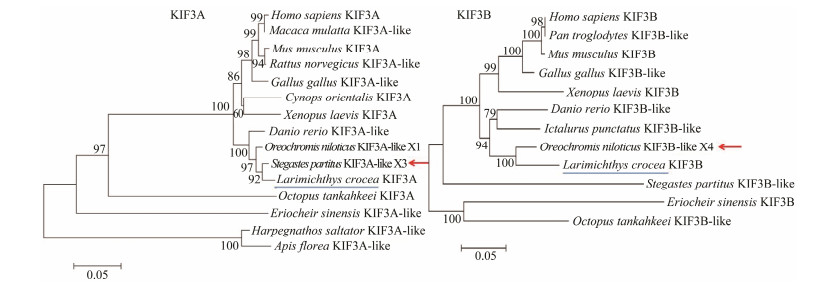

To characterize the evolutionary relationship of L. crocea KIF3A/3B and their homologues, phylogenetic trees were generated (Fig. 6). KIF3A from L. crocea was similar to the homologues of other teleost, and was most closely related to that of S. partitus. In contrast, the similarity was genetically distant from amphibians, birds, mammals, cephalopods, crustaceans, and insects. For KIF3B, a phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that the L. crocea and O. niloticus KIF3B appeared to be the most closely related. However, from amphibians, birds, mammals, and crustaceans to cephalopods, the genetic relationships decreased.

|

Fig. 6 Phylogenetic analysis of KIF3A/3B homologous protein sequences. As shown in the phylogenetic tree that was generated through neighbor-joining method (NJ 1000), the KIF3A of L. crocea (blue underline) is phylogenetically more closely related to that of S. partitus (red arrow), and the KIF3B of L. crocea (blue underline) is phylogenetically more closely related to that of O. niloticus (red arrow). Scale bar: 0.05 of branch length value. |

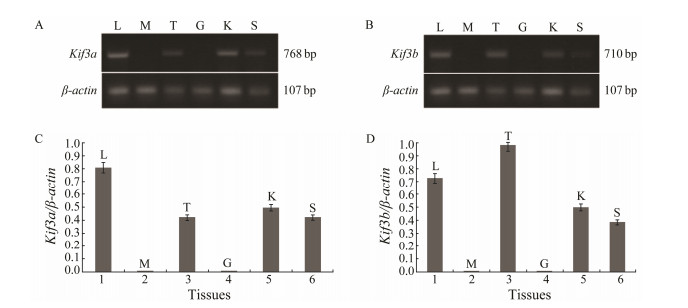

Different tissue samples from L. crocea were subjected to RT-PCR to analyze the distribution of kif3a/3b transcripts. In this experiment, a 768 bp kif3a and a 710 bp kif3b nucleotide fragments were amplified from six tissues. At the same time, a 107 bp actin was used as the control (Figs. 7A and B). When the tissue distributions of both kif3a and kif3b were compared, differences in the abundance of mRNA between certain tissues were apparent. They were expressed in all the tissues examined, except for the muscles and gills (Figs. 7C and D). High abundance kif3a mRNA was found in liver and kidney while lower abundance was found in testes and spleen (Fig. 7C). In contrast, kif3b was highly expressed in testes. However, its expression level in liver and kidney was low, and very low in spleen (Fig. 7D).

|

Fig. 7 Tissue-specific expressions of kif3a and kif3b mRNAs in L. crocea. (A) The tissue expression of kif3a in L. crocea. (B) The tissue expression of kif3b in L. crocea. (C) The quantitative analysis of kif3a mRNA abundance in L. crocea. (D) The quantitative analysis of kif3b mRNA in L. crocea. G, gill; T, testis; L, liver; M, muscle; K, kidney; S, spleen. |

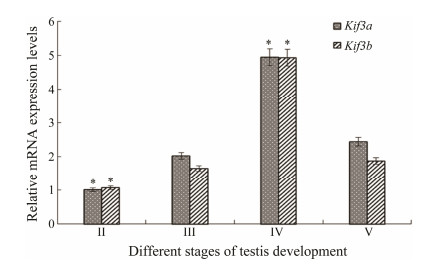

The qRT-PCR was performed for L. crocea testes to determine the temporal expression of kigf3a/3b at different developmental stages. An 84 bp mRNA fragment of kif3a and a 122 bp mRNA fragment of kif3b were detected in the testes via qRT-PCR at an annealing temperature of 60℃ and 59℃, respectively. The results showed that the overall trends of kif3a and kif3b expression during testis development were similar. From stage Ⅱ to stage Ⅴ, the expression levels of kif3a and kif3b increased initially and then fell before peaking at stage Ⅳ. Interestingly, mRNA abundances of both genes at stage Ⅴ were significantly lower, but still higher than those at stages Ⅱ and Ⅲ (Fig. 8).

|

Fig. 8 Kif3a/3b mRNA abundances at different stages of testis development. β-actin serves as an internal control. All data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference between the control and experimental group (P < 0.05). |

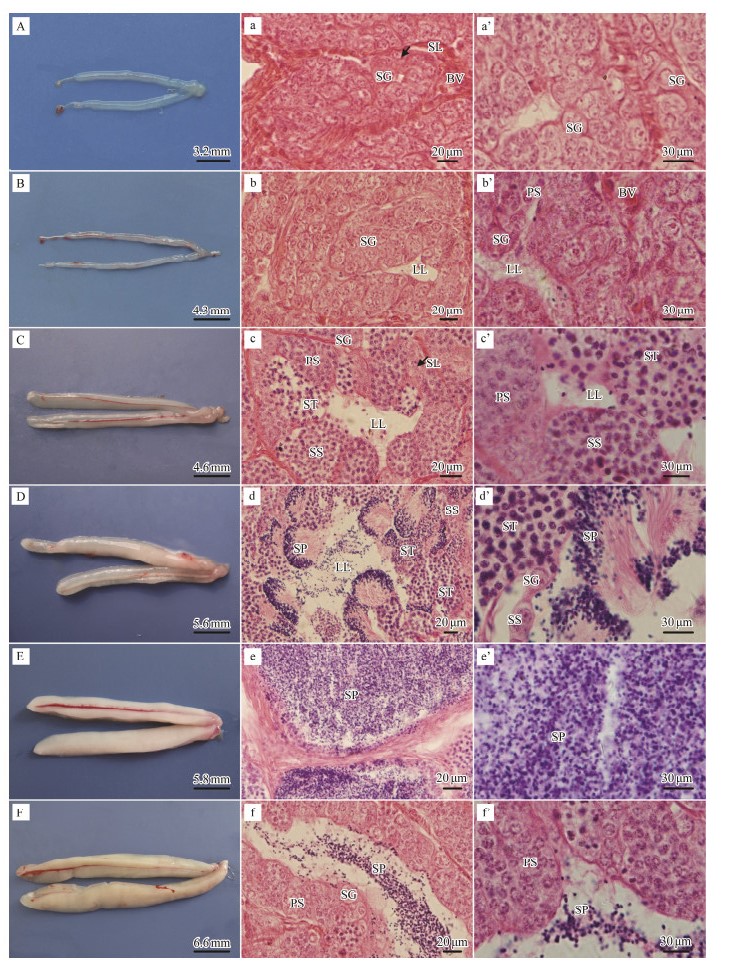

In order to understand the whole process of spermatogenesis of L. crocea, we first observed the reproductive cycle and testis development. The reproductive cycle of L. crocea testes was classified into stage Ⅰ to stage Ⅵ (Table 1), each had distinguishing features in appearance, volume, and color (Figs. 9A-F), and different spermatogenic cells had marked histological characteristics (Figs. 9a-f, Figs. 9a'-f').

|

Fig. 9 Anatomical and Histological images of testes at different development stages in L. crocea. (A) Stage Ⅰ testis. (B) Stage Ⅱ testis. (C) Stage Ⅲ testis. The flat-tape shaped testis is pale red owing to the development of blood vessels. (D) Stage Ⅳ testis. (E) Stage Ⅴ testis. (F) Stage Ⅵ testis. Scale bars: A = 3.2 mm; B = 4.3 mm; C = 4.6 mm; D = 5.6 mm; E = 5.8 mm; F = 6.6 mm. (a–a') Stage Ⅰ testis. Seminiferous lobules can be observed but the lobular cavity is not yet evident. Spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes can be observed. (b–b') Stage Ⅱ testis. The lobular cavity begins to appear. Spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes increase in significant numbers. The surface vessels are shown. (c–c') Stage Ⅲ testis. Seminiferous lobules are shown and the lobular cavity is evident. Spermatogonia, primary spermatocytes, secondary spermatocytes, and spermatids can be observed. Spermatogenic cysts (asterisks) show an independent distribution pattern. (d–d') Stage Ⅳ testis. Some spermatozoa are present in the lobular cavity. Primary spermatocytes, secondary spermatocytes, spermatids and spermatozoa can be observed. (e–e') Stage Ⅴ testis. The lobular cavity is filled with spermatozoa. A large number of spermatozoa can be observed. (f–f') Stage Ⅵ testis. The majority of spermatozoa have been discharged from the lobular cavity. Some spermatozoa remain in the lobular cavity. A–F: Enlarged images of a–f. SL, seminiferous lobule; LL, lobular lumen. |

As the result showed, stage Ⅰ in testis development only happens once in a lifetime (Table 1). It appears transparent and slimy, making it difficult to distinguish between males and females visually (Fig. 9A). For the microstructures, there are many irregular seminiferous lobules without cavities, which include abundant spermatogonia and a minority of primary spermatocytes (Figs. 9a and 9a'). The stage Ⅱ testis is translucent with a looming blood vessel (Fig. 9B). We can find the lobular cavity and increasing spermatocytes. In the meantime, spermatogonia are mainly distributed on the edges of the seminiferous lobules (Figs. 9b, 9b'). The stage Ⅲ testis is long and flat with an enlarged volume and appears reddish due to an abundance of blood vessels (Fig. 9C). Observation of slices showed that there are apparent lobular cavities and a variety of spermatogenic cysts, which contain different types of spermatids (Figs. 9c, 9c'). The stage Ⅳ testes take the form of a wide albescent strip (Fig. 9D). For the microstructures, the sperm begin to appear in the spermatogenic cysts (Figs. 9d, 9d'). The stage Ⅴ testes take the form of a milky ribbon and become turgid (Fig. 9E). When observing microstructures, they are full of sperm in the lobular cavity (Figs. 9e, 9e'). Nevertheless, the stage Ⅵ testes take the form of loose flavescens ribbon and appear smaller in size (Fig. 9F). A histopathological study showed that there are many empty lobular cavities because of the release of sperm (Figs. 9f, 9f').

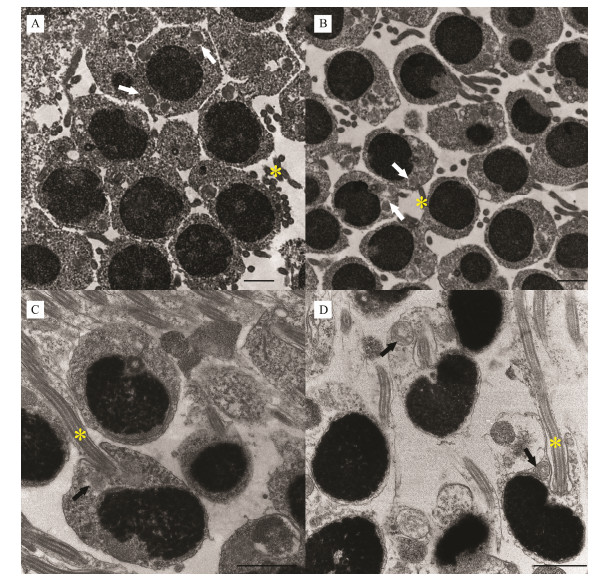

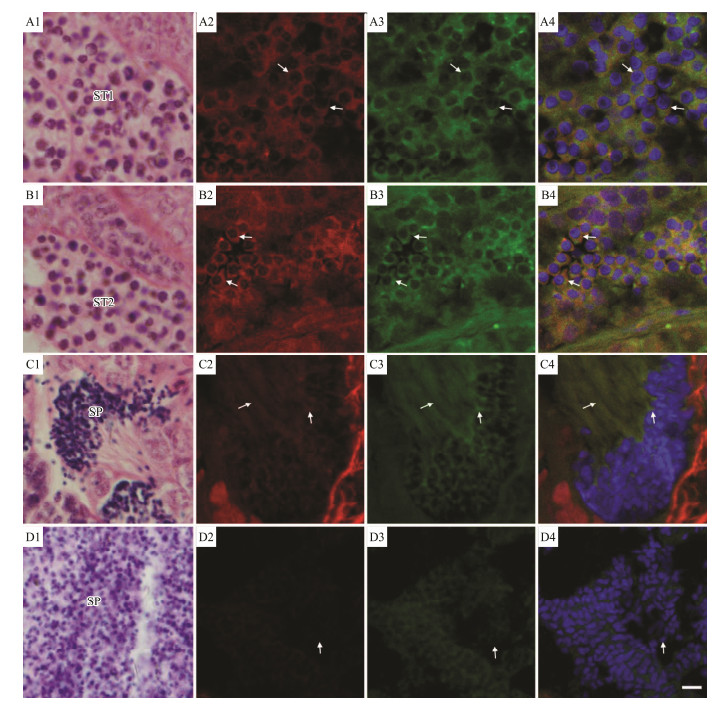

3.6 Spatiotemporal Expression Patterns of kif3a/3b During SpermiogenesisTo visualize the spatial expression patterns of kif3a/3b, fluorescence in situ hybridization was used in this study to localize nucleic acid sequences in tissue sections. In addition to a previous understanding of L. crocea spermatogenesis, the paraffin section and the transmission electron microscopy results showed that the process of spermiogenesis can be divided into four phases: early, medium, late, and mature (Fig. 10).

|

Fig. 10 The ultrastructure of spermiogenesis in L. crocea. A. In the early stage of spermatids, mitochondria are distributed around the nucleus and the flagellum begins to appear. B.In the middle stage of spermatids, the nucleus is skewed, mitochondria begin to migrate and the flagellum lengthen further. C. In the late stage of spermatids, mitochondria are clustered at the end of the nucleus. D. In the mature sperm, there are almost no cytoplasm and a few large mitochondria in the midpiece. The arrows indicate the mitochondria and the asterisk indicates the flagellum. Scale bars are 2 μm. |

As Figs. 10 and 11 showed, the shape of the early spermatid was characterized by a spheroidal head with a round or ovoid nucleus, in which the chromatin began to concentrate (Fig. 11A1). Various sizes of mitochondria were found around the nuclear membrane in the cytoplasm. Growing flagella began to appear (Fig. 10A). In this period, kif3a and kif3b mRNA were identified around the nuclear periphery (Figs. 11A2 and A3).

|

Fig. 11 Fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses of kif3a and kif3b mRNAs and structural charateristics of spermatid during spermiogenesis in L. crocea. A1–A4 show the early stage of spermatids. B1–B4 show the middle stage of spermatids. C1–C4 show the late stage of spermatids. D1–D4 show the mature sperms. A1, B1, C1 and D1 show the results through H.E. staining. A2, B2, C2 and D2 show the expression localization of kif3a (red). A3, B3, C3 and D3 show the expression localization of kif3b (green). A4, B4, C4 and D4 show the integration of kif3a and kif3b signals (yellow). The arrow indicates the typical signal. Scale bar was 5 μm. |

In the medium phase of spermatid, cells were found to be either round or oval, and had decreased in volume. The nucleus was also found to be round (Fig. 11B1). The chromatin was more condensed, and it was aggregated to one side in filamentous clusters. At this stage, mitochondria gradually became larger and transferred to one side of cell (Fig. 10B). In intermediate spermatid, the signals for expressed kif3a/3b mRNA were mainly localized to the periphery of the nuclear membrane and to one side of the nucleus (Figs. 11B2 and B3). In the late phase of spermatids, cells gradually changed in morphology, and the cytoplasmic volume was remarkably reduced (Fig. 11C1). Highly compacted chromatins were formed into numerous clusters with irregular outlines in the nucleus. The posterior of the nucleus was surrounded by multiple mitochondria to form a midpiece structure, and the flagellum lengthened during this stage (Fig. 10C). In late spermatid, the expression levels of kif3a/3b mRNA reached a peak, and the mRNA signals were concentrated on one end of nucleus and located in the tail (Figs. 11C2 and C3).

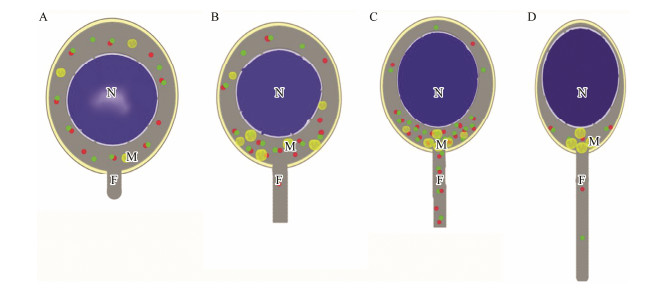

The mature spermatozoon was spherical, and the cytoplasmic volume was extremely reduced (Fig. 11D1). At this stage, the chromatin was completely condensed in the nucleus and mitochondria were only located in the midpiece (Fig. 10D). In mature spermatozoon, the mRNA signals of kif3a/3b were drastically weakened, but still distributed in the midpiece (Figs. 11D2 and D3). A negative control with sense probes showed no obvious hybridization signal (data not shown). Based on gene expression and transmission electron microscopy results, we constructed a model for the spatiotemporal expression of kif3a/3b during spermiogenesis in L. crocea (Fig. 12).

|

Fig. 12 Pattern diagram for the spatial-temporal expression analysis of kif3a/kif3b during spermiogenesis in L. crocea. A, an early spermatid. B, an intermediate spermatid. C, a late spermatid. D, a mature spermatozoon. Different shades in nucleus represent the degree of chromatin condensation. The dots in the figure indicate the mRNA signals of kif3a (red) and kif3b (green), respectively. Signal density corresponds to the abundance of mRNA. N, nucleus; M, mitochondria; F, flagellum. |

Spermiogenesis is a unique cell morphological developmental process, which is the basis of normal reproductive development and may be regulated by many different genes (Cooke et al., 1998). It is therefore important to study the molecular mechanism of spermiogenesis. KIF3A and KIF3B are important motor proteins with transport functions involved in this process. The reproductive and sperm structure of L. crocea has been reported early (You et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2010); however, information concerning the molecular mechanism of the morphological changes of the spermatid is still scant. Our study elucidated the reproductive cycle further and produced novel information regarding the expression of kif3a and kif3b in the kinesin-Ⅱ superfamily of proteins in L. crocea testes during spermiogenesis. To minimize individual differences, we used fish specimens from the same generation. Our findings suggested that kif3a and kif3b participate in spermiogenesis, and they may play key roles in the regulation of morphologic changes of the spermatid in L. crocea.

A wealth of evidences have indicated that the mRNAs encoding a number of kinesin-Ⅱ proteins are abundantly and extensively expressed in organisms (Cole et al., 1993; Berezuk and Schroer, 2004; Dishinger et al., 2010; Duangtum et al., 2011) and associated with the transport of membrane organelles, mitosis, meiosis, and differentiation of spermatid (spermiogenesis) (Le et al., 1998; Zou et al., 2002; Li et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Dang et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2012; Lehti et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2017). In our study, the full cDNA of kif3a and kif3b were cloned from L. crocea testes, and their expression levels were analyzed during the four stages of spermiogenesis.

In analyzing the motor domain of the deduced KIF3A and KIF3B of L. crocea, we found that KIF3A and KIF3B are 52% similar to one another, and they also have similar global tertiary structures consistent with other kinesin-Ⅱ proteins. In addition, they also have a coiled coil domain in the neck that may be attributed to certain interactions between KIF3A and KIF3B, which has been previously verified (Yamazaki et al., 1994; Yamazaki et al., 1996; De et al., 2001; Heinrich and Deshler, 2009). Analyzing the multiple sequence alignment and the phylogenetic tree of the deduced KIF3A and KIF3B, respectively, we found a high degree of similarity with other teleost fish. Interestingly, there was a low degree of similarity between the teleost fish L. crocea, the siphonopod O. tankahkeei, and the crustacean E. sinensis (data not shown). Since sequence determines structure and structure determines function, these differences imply that KIF3A and KIF3B in L. crocea testes may have diverse functions. Spermatogenesis varies from species to species. The morphology of sperm in O. tankahkeei is in the form of a slim column, which has a long cone acrosome and a long and slim flagellum (Zhu et al., 2006; Dang et al., 2012). The sperm of E. sinensis has no flagellum, but has a large acrosome (Lu et al., 2014). Compared to the sperm of E. sinensis and O. tankahkeei, that of L. crocea has no acrosome, but has a long and slim flagellum (You et al., 2001). This implied that KIF3A and KIF3B have different functions in L. crocea. However, the two homologous proteins are conserved in model organisms, in particular, regarding the N-terminal motor domain, although there are quite significant differences in the C-terminal motor domain. In O. tankahkeei testes, the N-terminals of KIF3A and KIF3B are more conserved than the C-terminals (Wang et al., 2010; Dang et al., 2012), whereas the two terminals of KIF3A in C. orientalis testes are both conserved (Hu et al., 2012). This difference between N-terminal and C-terminal domains in various species suggests that they may possess different functions. The tail domain can transport cargo molecules, such as various membranous organelles and protein complexes (Hirokawa et al., 1998; Hirokawa and Takemura, 2004), and the sequence differences of C-terminal domain may be related to cargo specificity (Campbell and Marlow, 2013). Structural prediction showed that the secondary and tertiary structures of KIF3A/3B in L. crocea are consistent, each contains three domains. Structurally, the ATP-binding site and microtubule-binding sites exist in the head, and the fold domain between the head and stalk can adjust the viability and motor direction. As for O. tankahkeei and E. sinensis, the structural features of KIF3A/3B proteins are similar to those of L. crocea (Dang et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2014), which suggest they work in a similar way. Research has shown that KIF3A and KIF3B often wind around each other to form a heterodimer, and they jointly serve an important biological function (Marszalek and Goldstein, 2000; Hirokawa and Tanaka, 2015). According to the predictive results for protein structure, we speculated that KIF3A and KIF3B of L. crocea may also form a dimer and work together.

The temporal and spatial expression patterns of kif3a/3b in spermiogenesis have been studied in siphonopods (Dang et al., 2012), crustaceans (Lu et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2017), amphibians (Hu et al., 2012), and mammals (Lehti et al., 2013). In this study, we described the temporal and spatial expression patterns in fish during spermiogenesis. RT-PCR showed that kif3a and kif3b mRNAs from L. crocea were detected in all of the tissues assayed, except muscle and gill (Fig. 7). In the testes, the level of kif3a mRNA was lower than that of kif3b mRNA, suggesting that kif3a and kif3b may both be involved in gonad development with different roles in L. crocea. Hu et al. (2012) also demonstrated that C. orientalis kif3a mRNA was detected in many of the organs examined, especially in the testes, which showed the highest abundance. However, kif3a and kif3b mRNAs showed low abundances in the testes of E. sinensis. It is possible that they have a different expression pattern in E. sinensis, whose sperms have no flagellum and maybe require very little kif3a/3b mRNA (Lu et al., 2014). Kif3a/3b mRNAs were also found in various tissues and organs of other species, such as nerve axons in mice and zebrafish (Yang and Goldstein, 1998; Raghupathy et al., 2016), and ciliary axonemes in sea urchin embryos (Morris and Scholey, 1997). Gene expression differences among various tissues may be caused by the particularity of the structure and function of different kinds of cells, especially germ cells.

Moreover, kif3a and kif3b transcripts were detected during testis development, which indicated that the overall trends of kif3a/3b mRNA abundances were similar. From stage Ⅱ to stage Ⅴ, kif3a/3b mRNA abundances both rose initially and then fell after reaching a peak at stage Ⅳ. Interestingly, mRNA levels of both genes were significantly decreased at stage Ⅴ, but were still higher than those at stages Ⅱ and Ⅲ. Furthermore, this varying regularity was consistent with the annual change of the testis gonadosomatic index in L. crocea. We can deduce that the increase and decrease of the abundances of kif3a/3b mRNAs change along with the development degree of testes, which can be determined by the type of cells in spermatogenic cysts. Thus, kif3a/3b can be considered to relate to spermatogenesis. In addition, according to the results of the microanatomy, stage Ⅳ testes, with the highest expression levels of both genes, contain abundant and multiple types of spermatids. Therefore, kif3a/3b may participate in the process of spermiogenesis. It has been reported that Kif3a/3b mRNAs were abundant in the testes of O. tankahkeei (Wang et al., 2010; Dang et al., 2012), E. sinensis (Lu et al., 2014), and Palaemon carincauda (Zhao et al., 2017), and kif3a mRNA was also found in C. orientalis testis (Hu et al., 2012). However, these studies did not investigate kif3a and kif3b mRNA abundances at different developmental stages of the testes, though the results indicated that kif3a and kif3b expressed during spermiogenesis. Spermiogenesis is a unique cell differentiation process controlled by many factors, among which gene regulation plays a vital role (Cooke et al., 1998; Li et al., 2003; Ge et al., 2008). Thus, from what has been discussed above, we speculated that kif3a/3b might participate in the process from spermatid forming to maturing into spermatozoa.

Spermatid development involves early, medium, and late stages, during which nuclear deformation is evident and where the tail gradually lengthens (You et al., 2001; Huszno and Klag, 2012; Papah et al., 2013; Fu et al., 2016). To detect the specific subcellular localization of kif3a/3b during spermiogenesis in L. crocea, we used fluorescence in situ hybridization technology which can detect a more pronounced distribution of signals than in situ hybridization technique in cells. In our study, we found that the dynamic expression patterns of kif3a and kif3b were consistent. In the early stage of spermatids, the expression levels of both kif3a and kif3b mRNAs in L. crocea were high, and increased in the intermediate spermatid. Subsequently, a weaker expression of kif3a/3b was detected in late spermatid, and the expression then weakened drastically in mature spermatozoon. In the final stages, kif3a was at an undetectable level in the mature sperm. In contrast, the expression levels of kif3a and kif3b were the highest in late spermatid in O. tankahkeei (Wang et al., 2010; Dang et al., 2012). It is worth of noting that in L. crocea the kif3b mRNA expression was higher than that of kif3a from early spermatids to mature spermatozoa, although kif3a and kif3b transcripts overlap with each other during the entire process of spermio-genesis. These results coincided well with the results of tissue-specific expression, which showed that kif3a and kif3b were both expressed in the testes but the expression levels of kif3b were higher (Fig. 7). In addition, both mRNA signals first appeared around the nuclear periphery, then at the side of the nuclei, and finally on the tail. This trend was similar to the changes observed in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of spermatids in previous reports (You et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2017). This expression pattern in sperm cells suggested that during spermiogenesis KIF3A and KIF3B might play roles during the deformation of the nucleus, as well as the enflagellation and migration of mitochondria. It has reported that other kinesin proteins, including KIFC1, KIF3C, KLC3, KIF1B β, and KIF5, were all involved in mitochondrial transport (Yang and Goldstein, 1998; Junco et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017). Studies have shown that KIF3A was co-localized with mitochondria and microtubules in the spermiogenesis of P. carincauda (Zhao et al., 2017) and E. sinensis (Lu et al., 2014). Additionally, the sperm tail structure has been shown to be disorganized with an abnormal manchette shape in KIF3A-knockout mice (Lehti et al., 2013). In O. tankahkeei and P. carincauda, KIF3A and KIF3B may be associated with nuclear deformation (Wang et al., 2010; Dang et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2017). As reported by Hu et al. (2012), kif3a mRNA was highly abundant in the tail of the C. orientalis sperm, and might participate in the differentiation of late spermatids. Moreover, Miller et al. (1999) reported that kinesin-Ⅱ only existed in the tail, and could be associated with the formation of sperm. Heterotrimeric kinesin-Ⅱ is required for the assembly of motile 9+2 ciliary axonemes and IFT20 is inclined to combine with KIF3B (Morris and Scholey, 1997). This suggests that KIF3A and KIF3B may interact as a dimer and participate in the transport of mitochondria, nuclear deformation, and the formation of the tail during spermiogenesis in L. crocea.

Though these studies are still static function analyses, some other technologies can be used to explore the function of KIF3A/3B in spermiogenesis, such as immunofluorescence, immune electron microscopy, and co-immunoprecipitation. RNA interference technology is widely used and allows for the efficient study of gene function by silencing specific target genes. However, this technology has not been widely applied in research related to kinesin function in spermiogenesis.

5 ConclusionsWe have cloned the kif3a/3b genes from L. crocea testes and constructed their expression patterns during the spermiogenesis. These findings suggested that KIF3A and KIF3B may play key roles in spermiogenesis, and potentially interact as a dimer to participate in the transport of mitochondria, nuclear deformation, and the formation of the tail in L. crocea.

AcknowledgementsWe would like to acknowledge Dr. Yaru Xu for the in situ hybridization technical assistance and Mr. Youfa Wang for valuable suggestions on picture processing. This work was financially supported by the Scientific and Technical Project of Zhejiang Province (Nos. 2016C02055-7, LY18C190007), the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (No. 2016A610081), the Scientific and Technical Project of Ningbo (No. 2015C110005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31602140), the Collaborative Innovation Center for Zhejiang Marine High-efficiency and Healthy Aquaculture, and the K. C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University.

Berezuk, M. A. and Schroer, T. A., 2004. Fractionation and characterization of kinesin ii species in vertebrate brain. Traffic, 5(7): 503-513. DOI:10.1111/j.1398-9219.2004.00197.x (  0) 0) |

Bot, N. L., Antony, C., White, J., Karsenti, E. and Vernos, I., 1998. Role of xklp3, a subunit of the xenopus kinesin ii heterotrimeric complex, in membrane transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and the golgi apparatus. Journal of Cell Biology, 143(6): 1559-1573. DOI:10.1083/jcb.143.6.1559 (  0) 0) |

Braubach, P., Lippmann, T., Raoult, D., Lagier, J. C., Anagnostopoulos, I., Zender, S., Länger, F. P., Kreipe, H. H., Kühnel, M. P. and Jonigk, D., 2017. Fluorescencein situhybridization for diagnosis of whipple's disease in formalin-fixed paraffinembedded tissue. Frontiers in Medicine, 4: 87. (  0) 0) |

Brown, C. L., Maier, K. C., Stauber, T., Ginkel, L. M., Wordeman, L., Vernos, I. and Schroer, T. A., 2010. Kinesin-2 is a motor for late endosomes and lysosomes. Traffic, 6(12): 1114-1124. (  0) 0) |

Campbell, P. D. and Marlow, F. L., 2013. Temporal and tissue specific gene expression patterns of the zebrafish kinesin-1 heavy chain family, kif5s, during development. Gene Expression Patterns, 13(7): 271-279. DOI:10.1016/j.gep.2013.05.002 (  0) 0) |

Chen, H., Lin, G. W., Liu, Z. K., Chen, W., Xie, Y. Q. and Wang, X. C., 2010. Study on growth characters of cultured Pseudosciaena crocea originated from eastern fujian. Marine Sciences, 34(11): 1-5. (  0) 0) |

Cole, D. G., Chinn, S. W., Wedaman, K. P., Hall, K., Vuong, T. and Scholey, J. M., 1993. Novel heterotrimeric kinesin-related protein purified from sea urchin eggs. Nature, 366(6452): 268-270. DOI:10.1038/366268a0 (  0) 0) |

Cooke, H., Hargreave, T. and Elliott, D., 1998. Understanding the genes involved in spermatogenesis: A progress report. Fertility & Sterility, 69(6): 989-995. (  0) 0) |

Dang, R., Zhu, J. Q., Tan, F. Q., Wang, W., Zhou, H. and Yang, W. X., 2012. Molecular characterization of a KIF3B-like kinesin gene in the testis of Octopus tankahkeei (Cephalopoda, Octopus). Molecular Biology Reports, 39(5): 5589-5598. DOI:10.1007/s11033-011-1363-4 (  0) 0) |

De, M. V., Burkhard, P., Le, B. N., Vernos, I. and Hoenger, A., 2001. Analysis of heterodimer formation by Xklp3A/B, a newly cloned kinesin-ii from Xenopus laevis. Embo Journal, 20(13): 3370-3379. DOI:10.1093/emboj/20.13.3370 (  0) 0) |

Dishinger, J. F., Kee, H. L., Jenkins, P. M., Fan, S., Hurd, T. W., Hammond, J. W., Truong, T. T., Margoils, B., Martens, J. R. and Verhey, K. J., 2010. Ciliary entry of the kinesin-2 motor KIF17 is regulated by importin-β2 and Ran-GTP. Nature Cell Biology, 12(7): 703. DOI:10.1038/ncb2073 (  0) 0) |

Duangtum, N., Junking, M., Sawasdee, N., Cheunsuchon, B., Limjindaporn, T. and Yenchitsomanus, P. T., 2011. Human kidney anion exchanger 1 interacts with kinesin family member 3B (KIF3B). Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications, 413(1): 69-74. (  0) 0) |

Fu, S. Y., Jiang, J. H., Yang, W. X. and Zhu, J. Q., 2016. A histological study of testis development and ultrastructural features of spermatogenesis in cultured Acrossocheilus fasciatus. Tissue & Cell, 48(1): 49-62. (  0) 0) |

Ge, S. Q., Kang, X. J., Liu, G. R. and Mu, S. M., 2008. Genes involved in spermatogenesis. Hereditas, 30(1): 3. (  0) 0) |

Gross, S. P., Tuma, M. C., Deacon, S. W., Serpinskaya, A. S., Reilein, A. R. and Gelfand, V. I., 2002. Interactions and regulation of molecular motors in Xenopus melanophores. Journal of Cell Biology, 156(5): 855. DOI:10.1083/jcb.200105055 (  0) 0) |

Heinrich, B. and Deshler, J., 2009. RNA localization to the balbiani body in Xenopus oocytes is regulated by the energy state of the cell and is facilitated by kinesin Ⅱ. Rna–A Publication of the Rna Society, 15(4): 524. (  0) 0) |

Henson, J. H., Cole, D. G., Roesener, C. D., Capuano, S., Mendola, R. J. and Scholey, J. M., 1997. The heterotrimeric motor protein kinesin-Ⅱ localizes to the midpiece and flagellum of sea urchin and sand dollar sperm. Cell Motility & the Cytoskeleton, 38(1): 29-37. (  0) 0) |

Hirokawa, N., 2010. Stirring up development with the heterotrimeric kinesin KIF3. Traffic, 1(1): 29-34. (  0) 0) |

Hirokawa, N. and Noda, Y., 2008. Intracellular transport and kinesin superfamily proteins, KIFs: Structure, function, and dynamics. Physiological Reviews, 88(3): 1089. DOI:10.1152/physrev.00023.2007 (  0) 0) |

Hirokawa, N. and Takemura, R., 2004. Kinesin superfamily proteins and their various functions and dynamics. Experimental Cell Research, 301(1): 50. (  0) 0) |

Hirokawa, N. and Tanaka, Y., 2015. Kinesin superfamily proteins (KIFs): Various functions and their relevance for important phenomena in life and diseases. Experimental Cell Research, 334(1): 16-25. (  0) 0) |

Hirokawa, N., Noda, Y. and Okada, Y., 1998. Kinesin and dynein superfamily proteins in organelle transport and cell division. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 10(1): 60. DOI:10.1016/S0955-0674(98)80087-2 (  0) 0) |

Hu, J. R., Xu, N., Tan, F. Q., Wang, D. H., Liu, M. and Yang, W. X., 2012. Molecular characterization of a KIF3A-like kinesin gene in the testis of the chinese fire-bellied newt Cynops orientalis. Molecular Biology Reports, 39(4): 4207-4214. DOI:10.1007/s11033-011-1206-3 (  0) 0) |

Hu, M., Miao, L., Li, M. Y., L., I., Zhang, H., Wang, J. H., Wang, T. Z. and Pan, N., 2014. Observation and comparison on the ultrastructure of the spermatozoon of Nibea albiflora and Pseudosciaena crocea. Journal of Biology, 31(2): 1-4 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Huszno, J. and Klag, J., 2012. The reproductive cycle in the male gonads of Danio rerio (teleostei, cyprinidae). Stereological analysis. Micron, 43(5): 666-672. DOI:10.1016/j.micron.2011.12.001 (  0) 0) |

Junco, A., Bhullar, B., Tarnasky, H. A. and Fa, V. D. H., 2001. Kinesin light-chain KLC3 expression in testis is restricted to spermatids. Biology of Reproduction, 64(5): 1320-1330. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod64.5.1320 (  0) 0) |

Le, B. N., Claude, A., Jamie, W., Eric, K. and Isabelle, V., 1998. Role of Xklp3, a subunit of the Xenopus kinesin Ⅱ heterotrimeric complex, in membrane transport between the Endoplasmic Reticulum and the Golgi Apparatus. Journal of Cell Biology, 143(6): 1559. DOI:10.1083/jcb.143.6.1559 (  0) 0) |

Lehti, M. S., Kotaja, N. and Sironen, A., 2013. KIF3A is essential for sperm tail formation and manchette function. Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology, 377(1-2): 44. (  0) 0) |

Li, B., Qi, X. Q., Chen, X., Huang, X., Liu, G. Y., Chen, H. R., Huang, C. G., Luo, C. and Lu, Y. C., 2010. Expression of targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2 is associated with progression of human malignant astrocytoma. Brain Research, 1352(1): 200-207. (  0) 0) |

Li, J. C., Jian, M. L., Jing, C., Ye, H. G., Zuo, R. Y., Dai, S. H., Zuo, M. Z. and Jia, H. S., 2003. NYD-SP16, a novel gene associated with spermatogenesis of human testis1. Biology of Reproduction, 68(1): 190-198. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.102.004242 (  0) 0) |

Lolkema, M. P., Mans, D. A., Snijckers, C. M., van Noort, M., van Beest, M., Voest, E. E. and Giles, R. H., 2007. The von Hippel–Lindau tumour suppressor interacts with microtubules through kinesin-2. Febs Letters, 581(24): 4571-4576. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.08.050 (  0) 0) |

Lopes, V. S., Jimeno, D., Khanobdee, K., Song, X., Chen, B., Nusinowitz, S. and Williams, D. S., 2010. Dysfunction of heterotrimeric kinesin-2 in rod photoreceptor cells and the role of opsin mislocalization in rapid cell death. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 21(23): 4076-4088. DOI:10.1091/mbc.e10-08-0715 (  0) 0) |

Lu, Y., Wang, Q., Wang, D. H., Zhou, H., Hu, Y. J. and Yang, W. X., 2014. Functional analysis of kIF3A and KIF3B during spermiogenesis of Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. PLoS One, 9(5): e97645. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0097645 (  0) 0) |

Marszalek, J. R. and Goldstein, L. S., 2000. Understanding the functions of kinesin-Ⅱ. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1496(1): 142. (  0) 0) |

Morris, R. L. and Scholey, J. M., 1997. Heterotrimeric kinesin-Ⅱ is required for the assembly of motile 9+2 ciliary axonemes on sea urchin embryos. Journal of Cell Biology, 138(5): 1009. DOI:10.1083/jcb.138.5.1009 (  0) 0) |

Nishimura, T., Kato, K., Yamaguchi, T., Fukata, Y., Ohno, S. and Kaibuchi, K., 2004. Role of the PAR-3-KIF3 complex in the establishment of neuronal polarity. Nature Cell Biology, 6(4): 328-334. DOI:10.1038/ncb1118 (  0) 0) |

O'donnell, L. and O'bryan, M. K., 2014. Microtubules and spermatogenesis. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 30(6): 45. (  0) 0) |

Papah, M. B., Kisia, S. M., Ojoo, R. O., Makanya, A. N., Wood, C. M., Kavembe, G. D., Maina, J. N., Johannsson, O. E., Bergman, H. L. and Laurent, P., 2013. Morphological evaluation of spermatogenesis in lake magadi tilapia (Alcolapia grahami): A fish living on the edge. Tissue & Cell, 45(6): 371-382. (  0) 0) |

Raghupathy, R. K., Zhang, X., Alhasani, R. H., Zhou, X., Mullin, M., Reilly, J., Li, W., Liu, M. and Shu, X., 2016. Abnormal photoreceptor outer segment development and early retinal degeneration in KIF3A mutant zebrafish. Cell Biochemistry & Function, 34(6): 429-440. (  0) 0) |

Takeda, S., Yamazaki, H., Seog, D. H., Kanai, Y., Terada, S. and Hirokawa, N., 2000. Kinesin superfamily protein 3 (KIF3A) motor transports fodrin-associating vesicles important for neurite building. Journal of Cell Biology, 148(6): 1255-1265. DOI:10.1083/jcb.148.6.1255 (  0) 0) |

Trivedi, D., Colin, E., Louie, C. M. and Williams, D. S., 2012. Live-cell imaging evidence for the ciliary transport of rod photoreceptor opsin by heterotrimeric kinesin-2. Journal of Neuroscience the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 32(31): 10587. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0015-12.2012 (  0) 0) |

Wang, W., Dang, R., Zhu, J. Q. and Yang, W. X., 2010. Identification and dynamic transcription of KIF3A homologue gene in spermiogenesis of Octopus tankahkeei. Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology Part A Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 157(3): 237-245. (  0) 0) |

Yamazaki, H., Nakata, T., Okada, Y. and Hirokawa, N., 1994. KIF3B forms a heterodimer with KIF3A and works as a new microtubule-based anterograde motor of membrane organelle transport. Neuroscience Research Supplements, 19: S84. (  0) 0) |

Yamazaki, H., Nakata, T., Okada, Y. and Hirokawa, N., 1996. Cloning and characterization of KAP3: A novel kinesin superfamily-associated protein of KIF3A/3B. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(16): 8443-8448. (  0) 0) |

Yang, W. X., Jefferson, H. and Sperry, A. O., 2006. The molecular motor KIFC1 associates with a complex containing nucleoporin NUP62 that is regulated during development and by the small GTPase RAN. Biology of Reproduction, 74(4): 684. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.105.049312 (  0) 0) |

Yang, Z. and Goldstein, L. S., 1998. Characterization of the KIF3C neural kinesin-like motor from mouse. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 9(2): 249. (  0) 0) |

You, Y., Lin, D. and Chen, L., 2001. Spermatogenesis of teleosts, Pseudosciaena crocea. Zoological Research, 22(6): 461-466 (in Chinese). (  0) 0) |

Zhang, D. D., Gao, X. M., Zhao, Y. Q., Hou, C. C. and Zhu, J. Q., 2017. The C-terminal kinesin motor KIFC1 may participate in nuclear reshaping and flagellum formation during spermiogenesis of Larimichthys crocea. Fish Physiology & Biochemistry, 43(5): 1351-1371. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y., Ou, Y., Cheng, M., Saadi, H. S., Thundathil, J. C. and Fa, V. D. H., 2012. KLC3 is involved in sperm tail midpiece formation and sperm function. Developmental Biology, 366(2): 101-110. DOI:10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.026 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, C., Omori, Y., Brodowska, K., Kovach, P. and Malicki, J., 2012. Kinesin-2 family in vertebrate ciliogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(7): 2388-2393. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1116035109 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Y. Q., Yang, H. Y., Zhang, D. D., Han, Y. L., Hou, C. C. and Zhu, J. Q., 2017. Dynamic transcription and expression patterns of KIF3A and KIF3B genes during spermiogenesis in the shrimp. Palaemon carincauda. Animal Reproduction Science, 184: 59-77. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2017.06.017 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, H., Dong, Y. and Sun, Y., 2013. Detection of KIF2A mRNA in male ejaculate by real-time fluorescence quantitative RT-PCR. Acta Universitatis Medicinalis Anhui, 48(11): 1387-1390. (  0) 0) |

Zhu, J. Q., Yang, W. X., You, Z. J., Wang, W. and Jiao, H. F., 2006. Ultrastructure of spermatogenesis of Octopus tankahkeei. Journal of Fisheries of China, 4(2): 161-169 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zou, Y., Millette, C. and Sperry, A., 2002. KRP3A and KRP3B: Candidate motors in spermatid maturation in the seminiferous epithelium. Biology of Reproduction, 66(3): 843-855. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod66.3.843 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18