2) Shanghai Merchant Ship Design and Research Institute, Shanghai 201203, China

Traditionally, ship designers have concentrated on the performance of ships during direct navigation in deep water, and less attention has been paid to oblique navigation in shallow waters. When a ship navigates in shallow-water areas such as ports, the development of the ship boundary layer and the pressure on the hull surface are influenced by the seabed. This influence can affect the ship's hydrodynamic performance and may lead to accidents such as grounding or running aground. Oblique flow, which causes changes in the hull wake, results in considerable alterations in the propeller thrust and torque characteristics curve. This situation decreases the propeller's open-water efficiency. Furthermore, oblique flow can induce substantial transverse forces and moments on the propeller, which can affect the safety of ship navigation. Therefore, studying the motion characteristics of ships in oblique flow and shallow water, as well as understanding the distribution of flow fields, is crucial for assessing the feasibility of ship operations in restricted waters and guaranteeing the safety of ship navigation in such areas.

Several studies have focused on the effects of drift angle and shallow-water conditions. For example, Xing et al. (2007) examined the vortical flow on KVLCC2 at large drift angles using several turbulence models; they found steady flows for the drift angles of 0˚ and 12˚ and unsteady flows for the drift angle of 30˚. In another paper, Xing et al. (2012) refined the mesh, applied DES (detached eddy simulation) method to the three drift angles on the flow around KVLCC2, and captured more complicated vertical structures from their DES simulation. Fureby et al. (2016) compared Reynolds Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS), hybrid RANS-LES, and LES, and observed several new vortex systems at oblique flow conditions while investigating the vortical structure of the KVLCC2 model. Regarding the shallow-water effect, Toxopeus et al. (2011) conducted extensive computational fluid dynamic (CFD) research on benchmark cases with varying water depths provided by SIMMAN-2008 and evaluated multiple CFD programs based on the results. Liu and Wan (2015) simulated the viscous flow field during a ship's roll motion under different water depths. Bechthold and Kastens (2020) examined the sinkage and trim characteristics of three container ships in shallow waters. Oud and Bedos (2022) conducted numerical simulations on the hydrodynamic performance and maneuverability of ships at different speeds and water depths, and Su et al. (2023) studied the influence of shallow-water effects on ship resistance and flow field, simulating the distribution of wave field, pressure field, and flow field under different water depth conditions.

Most of the existing research is focused on the oblique flow effect in deep water or the effect of shallow water in straight-ahead conditions. When a ship navigates near the shore or into a port, it may operate in shallow oblique flows. In such circumstances, the flow field around the ship is more complicated than that in shallow water but straight-ahead conditions or in deep oblique flow. The knowledge about the ship's dynamic response in shallow oblique flows remains limited despite a few research work on it. Okano et al. (2004) performed experimental research on a ship's hydrodynamic performance in varying water depths and a small range of drift angles. They also proposed a mathematical model to describe the hydrodynamic performance. Tian (2008) combined model experiments with numerical simulations to analyze the hydrodynamic performance and maneuverability of the KVLCC2 ship model within a drift angle range of 0˚ – 12˚ under varying water depths. Meng and Wan (2016) analyzed the variations in ship hydrodynamics, hull surface pressure distribution, and wake field of the KVLCC2M ship model within a drift angle range of 0˚ – 12˚ under varying water depth conditions. Zhou et al. (2016) proposed a predictive algorithm for forecasting a ship's hydrodynamic performance in restricted water areas and simulated ship passage through a dredged channel in a drifting configuration employing numerical methods.

The above research suggests that the hydrodynamic performances and wake characteristics of ships are complicated in oblique shallow water or restricted water areas. However, comprehensive research on the influence of shallow water and oblique flows is lacking because the above work only considered typical conditions and flow characteristics. For example, the wake field in oblique shallow water has not been systematically investigated.

This paper aims to explore the shallow-water effect on the hydrodynamic forces and wake characteristics of a ship in oblique flows by considering a wide range of drift angles and water depths. An international ship model, KVLCC2, is adopted as the computed object. The changes in the ship's hydrodynamic forces and wake characteristics are analyzed by varying the drift angle and water depth. The RANS method combined with the shear stress transport (SST) k-ω turbulence model is used to simulate numerous operating conditions. The computed longitudinal and transverse forces on the hull and the nominal wake distribution on the propeller center plane are compared between different water depths to analyze the influence of water depth. Section 2 outlines the geometric shape and dimensions of the ship model. Section 3 introduces the numerical methods employed. Section 4 compares and validates the computational results with the experimental data. Section 5 thoroughly analyzes and discusses the computed results. Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings and insights drawn from the study.

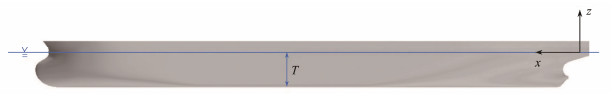

2 KVLCC2 Geometry and Principal DimensionsThe international ship model KVLCC2 is examined here, considering its sufficient experimental data available for CFD validation. Fig. 1 presents the geometry of KVLCC2 and the position and orientation of the coordinate system of the hull model. The origin of the coordinate system is set to the intersection point between the aft perpendicular and calm water surface, and the direction of the coordinate axes is presented in the figure, following the right-hand rule. The main parameters of the actual ship and the model are listed in Table 1. The design speed of the actual ship is 15.5 kn, which corresponds to the Froude number Fr = 0.142. The calculations in this paper are based on the model scale with a scale ratio of λ = 45.7.

|

Fig. 1 Geometry of the KVLCC2 model. |

|

|

Table 1 Principal dimensions of KVLCC2 |

In this study, the unsteady RANS method is adopted. Considering air and water as incompressible fluids and the flow around the ship's hull as a 3D steady flow, the governing equations are as follows:

| $ \frac{{\partial {{\bar u}_i}}}{{\partial {x_i}}} = 0, $ | (1) |

| $\begin{array}{l} \frac{{\partial \left({\rho {{\bar u}_i}} \right)}}{{\partial t}} + \frac{\partial }{{\partial {x_j}}}\left({\rho {{\bar u}_i}{{\bar u}_j}} \right) =\\ \;\;- \frac{{\partial \bar P}}{{\partial {x_i}}} + \frac{\partial }{{\partial {x_j}}}\left[ {\mu \left({\frac{{\partial {{\bar u}_i}}}{{\partial {x_j}}} + \frac{{\partial {{\bar u}_j}}}{{\partial {x_i}}}} \right)} \right] + \frac{\partial }{{\partial {x_j}}}\left({ - \rho \overline {{{u'}_i}{{u'}_j}} } \right) + {\bar f_i}, \end{array}$ | (2) |

where i and j are the coordinate components; ρ is the density of the fluid; μ is the viscosity of the fluid; P is the pressure; u is the velocity vector; f is the body force (in this study, f is the gravity); and

Different turbulence models can have certain effects on computational outcomes. The SST k-ω turbulence model employs the k-ω model in the near-wall region and the k-ε model in the far-field region; thus, it exhibits higher accuracy in both regions. In the SST k-ω model, the Reynolds stress term is approximated based on the Boussinesq hypothesis as follows:

| $ \frac{\partial }{{\partial {x_j}}}\left({ - \rho \overline {{{u'}_i}{{u'}_j}} } \right) = {\mu _T}\left({\frac{{\partial {{\bar u}_i}}}{{\partial {x_j}}} + \frac{{\partial {{\bar u}_j}}}{{\partial {x_i}}}} \right) - \frac{2}{3}{\delta _{ij}}\rho k, $ | (3) |

where

The simulation of the free surface in the computational domain employs the volume of fluid (VOF) method, and the governing equation of the VOF method is as follows:

| $ \frac{\partial }{{\partial t}}(f) + \frac{\partial }{{\partial {x_i}}}(f{u_i}) = 0 . $ | (4) |

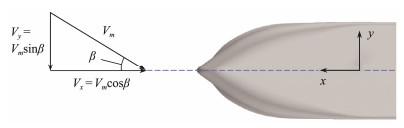

In the computations, the ship is stationary, and movements such as sink, trim, and square are not allowed, while the water comes from a far field with the ship's speed. The direction of the incoming flow is aligned with that of the oblique flow. The selection of the drift angle is based on the actual operating situation. A large bulk carrier's speed and propeller speed decrease as the drift angle increases. During the stable turn of the ship, the drift angle may exceed 20˚, but the speed in this case is much lower than the service speed. Hence, studying the hydrodynamic performance and hull wake at the service speed at a larger drift angle is unreasonable, and using a test matrix containing various ship speeds and drift angles to analyze the whole maneuvering is better. On the one hand, the calculation cost of the test matrix is extremely high. On the other hand, this paper focuses on the effect of the oblique flow on the hydrodynamic performance and hull wake rather than the effect of the oblique flow on the ship maneuvering. Thus, a range of drift angles from 0˚ to 20˚ with an interval of 5˚ is considered in this paper. Fig. 2 presents a diagram of the oblique flow condition setup, where β is the drift angle, Vm is the magnitude of inflow, and Vx and Vy are the velocity components.

|

Fig. 2 Oblique flow condition setting. |

When the bottom of the ship is close to the bottom of the water, it can cause changes in the flow field around the hull and the hydrodynamic performance of the ship. This phenomenon is referred to as the shallow-water effect. The water depth is typically quantified using the ratio of water depth (h) to ship draft (T), known as the water depth-to-draft ratio (h/T). According to h/T, water depths can be categorized into four (PIANC, 1992), as shown in Table 2. The 23rd International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC, 2002) Maneuvering Committee summarized the influence of water depth on a ship's hydrodynamic performance as follows: The effect of water depth on a ship's hydrodynamic performance becomes evident at moderate depth water. In shallow water, this influence is particularly substantial. In shallow water, water depth becomes the dominant factor affecting a ship's hydrodynamic performance. Twenty operating conditions are computed, and the simulation matrix is shown in Table 3.

|

|

Table 2 Division of water depth |

|

|

Table 3 Setting of operating condition |

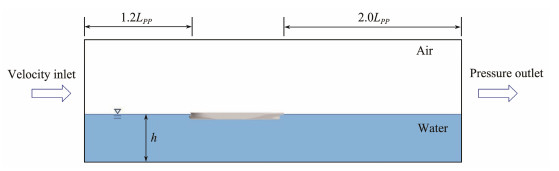

The computational domain is a rectangular box containing the hull, and its dimensions are shown in Fig. 3. The inlet is 1.2LPP upstream of the ship, the outlet is 2.0LPP downstream of the ship, and the width of the computational domain is 3.6LPP. The side and top boundaries are set to slip boundary conditions, and the bottom and hull surfaces are set as nonslip boundaries. For the still-water problem, the boundary of this computational domain is adequately far from the boat to be a reasonable range. Other studies on oblique flow or shallow-water effect, such as Xing et al. (2007, 2012), Meng (2020), and Zhang et al. (2020), used similar-sized computational domains. Under shallow-water conditions, the free surface may introduce considerable disturbances to the calculation results. The influence of the free surface must be considered, so the VOF method is adopted for simulating the free surface.

|

Fig. 3 Computational domain. |

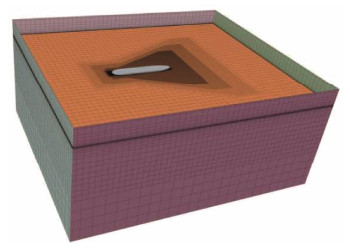

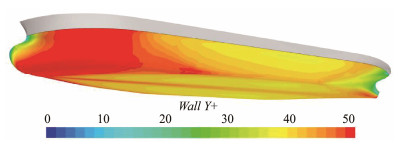

A set of unstructured hexahedral meshes was generated in STAR-CCM+, and Fig. 4 shows the mesh distribution in the computational domain. Multiple refinement levels were used around the hull to achieve a reasonable mesh distribution. The finest mesh was distributed in the wake region of the hull. Eight layers of prismatic meshes were generated on the hull surface to improve the boundary layer calculations. Fig. 5 presents the distribution of Wall Y+ on the hull surface. The Wall Y+ is between 30 and 50 for most of the hull surface. According to the user guide (CD-Adapco, 2014) of STAR-CCM+, the Wall Y+ value should be situated in the logarithmic region of the boundary layer (Wall Y+ > 30). Thus, the setting of the boundary layer grid is reasonable.

|

Fig. 4 Grid distribution of the computational domain. |

|

Fig. 5 Wall Y+ distribution on the wetted hull surface. |

To balance computational accuracy and efficiency, establishing suitable grid sizes is essential. Consequently, convergence verification was performed on five sets of distinct grids. The proportion between the ship hull grid and computational domain grid remained constant, whereas the base grid size was adjusted by an approximate growth rate of

| $ {C_X} = \frac{{{F_X}}}{{\frac{1}{2}\rho V_m^2{S_w}}}, $ | (5) |

|

|

Table 4 Verification results of grid convergence |

where FX is the longitudinal force with the same direction as Vx.

Table 4 shows that with the increase in grid resolution, the predicted longitudinal force coefficients gradually converge, and the differences in the coefficients predicted by Meshes 3 – 5 are already minimal. To conserve computational resources, the grid division method of Mesh 3 was selected for subsequent numerical simulation calculations. In deep-water conditions, the mesh at the bottom and near the bottom of the ship was not refined. However, in shallow-water conditions, the mesh in this area was refined to improve the accuracy of simulation calculations.

4.2 Validation of Method EffectivenessDue to the differing hydrodynamic characteristics between deep and shallow waters, experimental results (EFD) and numerical simulation results (CFD) for the longitudinal force coefficient CX, lateral force coefficient CY, and yaw moment coefficient CN, obtained from both types of waters were validated separately. Experimental data from Toxopeus et al. (2013) were selected for comparative analysis, and relative error was denoted as E. The vessel operated at low speed, with Vm = 0.5328 m s−1, corresponding to a Froude number Fr = 0.0643. The drift angle β values were set at 0˚ and 4˚, and the water depth-to-draft ratios h/T were 1.2 and 31.8, corresponding to shallow and deep waters, respectively. The validation results for hydrodynamic coefficients are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Fig. 6 compares the nominal wake velocity field obtained from Case 16 at the propeller plane (x/LPP = 0.023) and the experimental results from Kim et al. (2001), and the model ship speed Vm = 1.1794 m s−1 corresponded to a Froude number Fr = 0.142.

|

|

Table 5 Validation of shallow-water method |

|

|

Table 6 Validation of the deep-water method |

|

Fig. 6 Comparison of axial velocity component at the propeller plane (Case 6). (a), EFD; (b), CFD. |

CY, CN, and E are defined as follows:

| $ {C_Y} = \frac{{{F_Y}}}{{\frac{1}{2}\rho V_m^2{S_w}}}, $ | (6) |

| $ {C_N} = \frac{{{M_N}}}{{\frac{1}{2}\rho V_m^2{S_w}{L_{PP}}}}, $ | (7) |

| $ E = \frac{{CFD - EFD}}{{EFD}} \times 100\%, $ | (8) |

where FY is the transverse force with the same direction as Vy, and MN is the yaw moment positive turn to the port side.

Tables 5 and 6 show that the numerical simulation results in both water domains agree with the experimental results, and relative errors are all below 5.4%. In Fig. 6, the wake behind the hull displays a typical 'hook' pattern, which is well captured by the CFD simulation. The area of the low-speed region in the CFD prediction is also similar to the experimental results, indicating the feasibility of the numerical simulation method for subsequent calculations in this study.

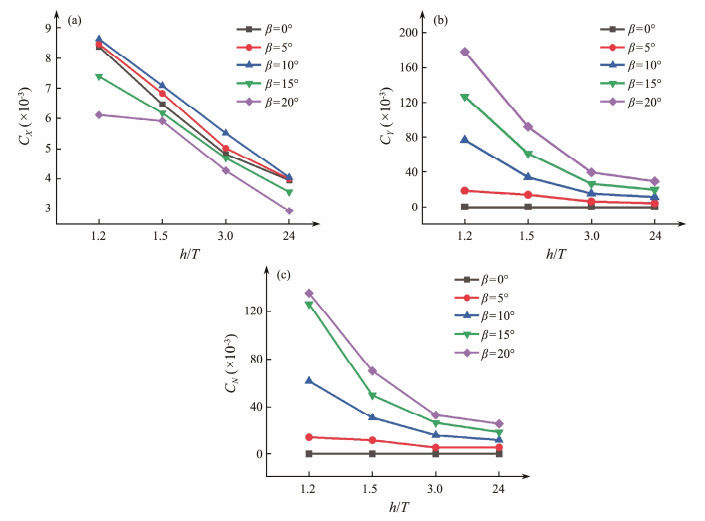

5 Results and Discussion 5.1 Hydrodynamic LoadsFig. 7 shows the variation curves of CX, CY, and CN with different water depths and drift angles. The shallow-water effect is substantial for CX and almost independent of drift angles. The CX in shallow water is higher than that in deep water. For example, the CX in shallow water (h/T = 1.2) is 2.1 times larger than that in deep water. In addition, drift angle has a weaker effect on CX with respect to water depth.

|

Fig. 7 Results of CX (a), CY (b), and CN (c) against water depth. |

The difference in CX between h/T = 1.2 and h/T = 1.5 is not considerable. This result could be attributed to the remarkable drift angle at this point. Compared with shallow-water effects, CX is mainly influenced by oblique flow.

The curves for CY and CN have similar trends with varying water depths and drift angles. The importance of the shallow-water effect depends on the drift angle. In cases of higher drift angles, the shallow-water effect is much more remarkable, where the CY and CN in shallow water are much larger than those in deep water. CY and CN increased by 504% and by 438%, respectively, compared with those in deep water. Moreover, the increase in CY and CN with decreasing water depth is strongly nonlinear. The smaller the water depth is, the faster the increase of CY and CN.

5.2 Dynamic Pressure on the Hull SurfaceThe distribution of dynamic pressure on the ship's hull surface is crucial for analyzing the forces acting on the ship. The pressure values are typically represented using the nondimensional pressure coefficient CP, which is defined as follows:

| $ {C_P} = \frac{P}{{\frac{1}{2}\rho V_m^2}}, $ | (9) |

where P represents the surface pressure on the ship's hull.

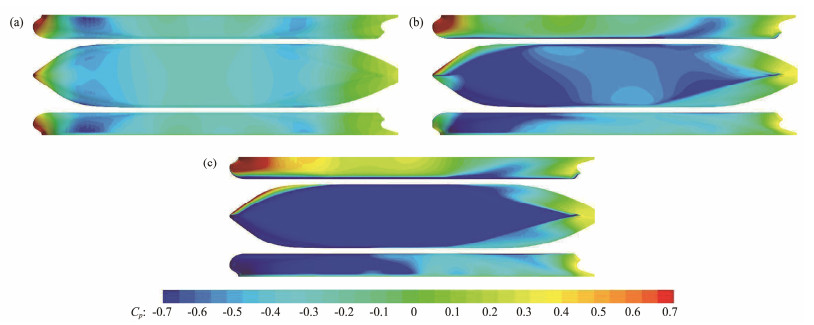

Figs. 8 and 9 illustrate the variation of the dynamic pressure on the hull surface with different drift angles in deep water (h/T = 24) and shallow water (h/T = 1.2), respectively. The hull surface pressure exhibits clear symmetry when β = 0˚ in deep water and shallow water. At the start and end of the parallel mid hull, low-pressure zones are observed, which may be due to the fast changes in the transverse area of the hull sections in these regions, leading to an increase in flow velocity. As the drift angle increases, the asymmetry in hull surface pressure distribution becomes more pronounced. The low-pressure region shifts toward the leeward side, whereas the high-pressure region shifts toward the windward side. Consequently, the pressure on the starboard side of the bow is lower than that on the port side, resulting in a transverse force directed toward the starboard side. Similarly, the pressure on the starboard side of the stern is higher than that on the port side, leading to a transverse force directed toward the port side. However, the distribution of pressure difference between the port and starboard sides, in terms of the affected area and magnitude, is primarily concentrated in the bow region. As a result, the entire ship experiences a transverse force toward the starboard side and a yaw moment, causing forward rotation. As the drift angle increases, the pressure difference at the bow and stern of the hull increases. However, the difference in pressure distribution near the bow increases rapidly and has a larger influencing area. Consequently, the transverse force acting on the entire ship increases and is directed toward the starboard side. Additionally, the yaw moment increases. Compared with deep-water conditions, in shallow water, the low-pressure region on the hull surface has a larger affected area. The asymmetry in hull surface pressure distribution is more pronounced, resulting in a greater pressure difference between the two sides of the hull. This situation leads to larger transverse forces and yaw moments on the ship in shallow water, which is unfavorable for ship maneuverability.

|

Fig. 8 Dynamic pressure on the hull surface for different drift angles at h/T = 24 (top, port side; middle, bottom of the ship; and bottom, starboard side). (a), β = 0˚; (b), β = 10˚; (c), β = 20˚. |

|

Fig. 9 Dynamic pressure on the hull surface for different drift angles at h/T = 1.2 (top, port side; middle, bottom of the ship; and bottom, starboard side). (a), β = 0˚; (b), β = 10˚; (c), β = 20˚. |

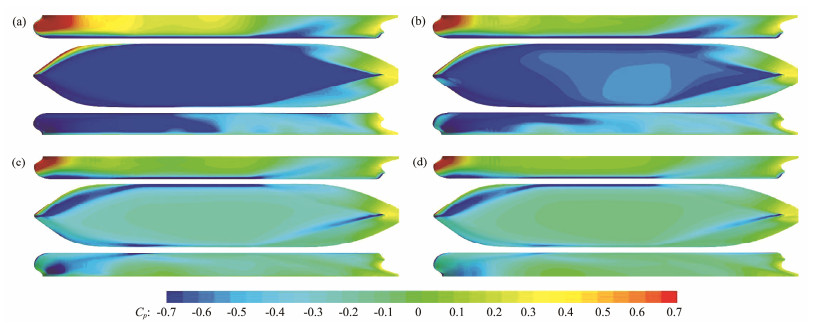

Fig. 10 presents the distribution of hull surface pressure at different water depths with β = 20˚. The computational results demonstrate a clear influence of water depth on the distribution of hull surface pressure. As the water depth decreases, the pressure on the bottom of the hull gradually decreases, and the low-pressure area increases. This outcome is primarily because when ships navigate in shallow waters, the reduced clearance between the water bottom and the ship's bottom causes an increase in flow velocity under the hull, leading to low pressure. This outcome can result in squatting, in which the ship sinks lower in the water, or even causes a grounding accident. Additionally, with decreasing water depth, the pressure difference between the two sides of the hull increases. This development leads to a larger transverse force and yaw moment acting on the ship. This reason also explains why the results for CY and CN in shallow water, as shown in Figs. 8(b) and 8(c), are higher than those in deep water. Comparing Figs. 10(c) and 10(d) reveals that the difference between the two is minimal, indicating that the influence of shallow-water effect on ship hydrodynamic performance is weak when h/T > 3.0.

|

Fig. 10 Dynamic pressure on the hull surface at different water depths for β = 20˚ (top, port side; middle, bottom of the ship; and bottom, starboard side). (a), h/T = 1.2; (b), h/T = 1.5; (c), h/T = 3.0; (d), h/T = 24. |

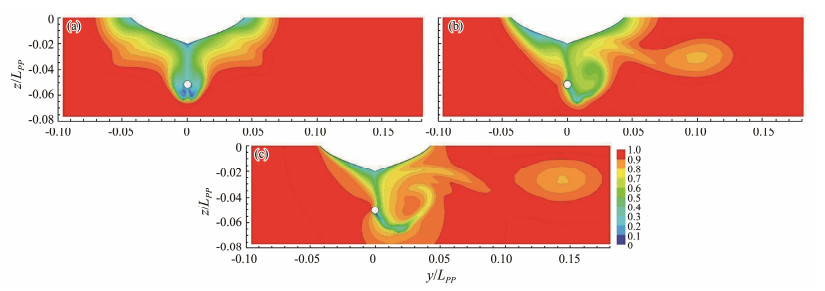

Figs. 11 and 12 show the nondimensional axial velocity (u/U) at the propeller disk plane (x/LPP = 0.023) in deep water (h/T = 24) and shallow water (h/T = 1.2) for different drift angles. The axial velocities are right-left symmetric for deep and shallow water in the case of β = 0˚. However, due to the blockage caused by the hull and water bottom, the axial velocity in h/T = 1.2 is much lower than that in h/T = 24. As the drift angle increases, the axial velocity on the windward side increases, and the axial velocity on the leeward side decreases. The low-speed area near the propeller center is deflected by the incoming oblique flow and moved out of the propeller disk. When the drift angle increases, the vortex strength increases, and the vortex core shifts toward the starboard side. The asymmetry of wake becomes evident, and the wake on the leeward side is more complex compared with that on the windward side. This asymmetry causes an increase in transverse force and yaw moment, which is unfavorable for ship stability. Additionally, this may lead to a movement of the maximum load position of the propeller blade and may affect the propeller efficiency.

|

Fig. 11 Axial velocity in h/T = 24 at the plane x/LPP = 0.023 for three drift angles. (a), β = 0˚; (b), β = 10˚; (c), β = 20˚. |

|

Fig. 12 Axial velocity in h/T = 1.2 at the plane x/LPP = 0.023 for three drift angles. (a), β = 0˚; (b), β = 10˚; (c), β = 20˚. |

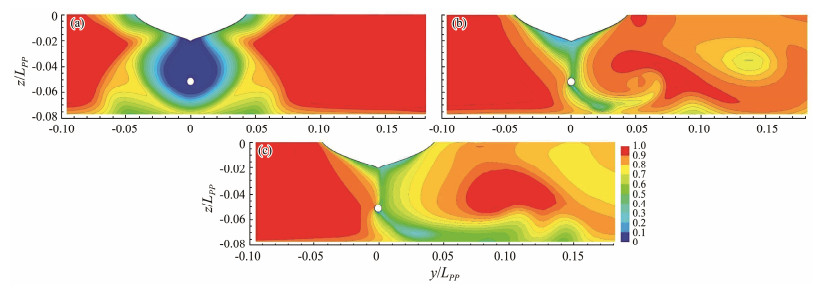

Fig. 13 illustrates the nondimensional axial velocity (u/U) at the propeller disk plane (x/LPP = 0.023) for different water depths in the case of β = 20˚. As the water depth decreases, the flow separation becomes more pronounced. The nonlinear effects of fluid viscosity and flow analysis remarkably influence the flow field of ships navigating in shallow waters. Furthermore, comparing Figs. 13(c) and 13(d) reveals a minimal difference between the two, further indicating that the shallow water effect can be neglected when h/T > 3.0.

|

Fig. 13 Axial velocity in β = 20˚ at the plane x/LPP = 0.023 for four water depths. (a), h/T = 1.2; (b), h/T = 1.5; (c), h/T = 3.0; (d), h/T = 24. |

The mean wake fraction is the average of Taylor wake fraction over the propeller plane, which is defined as follows:

| $ {\omega _x} = \frac{{\int_0^{2{\text{π }}} {\int_{{R_h}}^R {{W_T}r{\text{d}}r{\text{d}}\theta } } }}{{\int_0^{2{\text{π }}} {\int_{{R_h}}^R {r{\text{d}}r{\text{d}}\theta } } }}, $ | (10) |

where the origin of the coordinate system is in the propeller center, r is the coordinate in the radial direction, θ is the coordinate in the circumferential direction, Rh is the radius of the hub, and R is the radius of the propeller. WT is the Taylor wake fraction, defined as follows:

| $ {W_T} = 1 - \frac{{V(r, \theta)}}{{{V_m}}}, $ | (11) |

where V(r, θ) is the axial velocity.

Fig. 14 shows the variation of mean wake fraction with water depth for different drift angles. The results indicate that as the drift angle increases, the mean wake fraction decreases regardless of water depth. The shallow-water effect is not evident for larger drift angles but substantial for smaller drift angles. The primary reason for this is that as the drift angle increases, the transverse flow increases, whereas the axial velocity decreases markedly. In drift angles of β = 0˚ and β = 5˚, the shallow-water effect causes a nonlinear increase in the mean wake fraction. In straight sailing, the mean wake fraction decreases by 29% when water depth increases from h/T = 1.2 to h/T = 3.0.

|

Fig. 14 Variation of mean wake fraction with water depth for different drift angles. |

To analyze the effect of the shallow-water effect on the wake flow of the ship in oblique flow quantitatively, this section discusses the circumferential distribution of wake velocity. On the propeller plane, the wake at 0.7 times the propeller radius (r = 0.7R) is important to the propeller design. Fig. 15 shows the definition of the phase angle.

|

Fig. 15 Definition of the phase angle (stern view). |

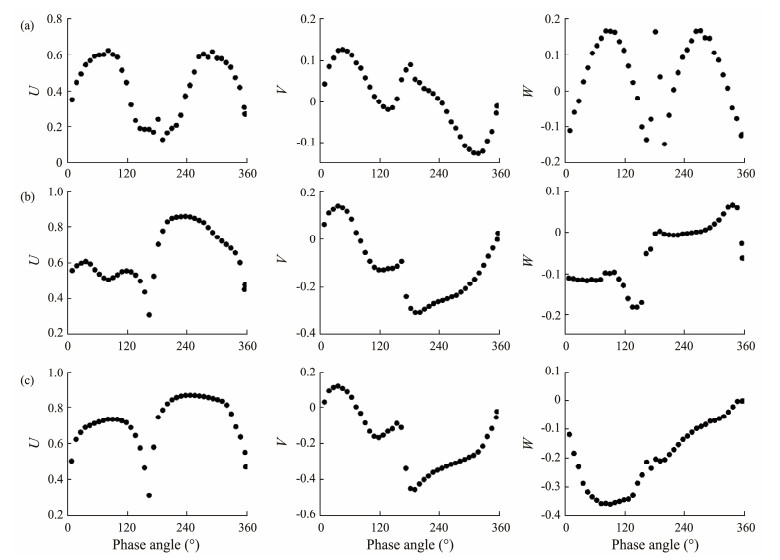

Figs. 16 and 17 illustrate the circumferential distribution of axial velocity U, tangential velocity V, and radial velocity W at the propeller disc (x/LPP = 0.023) for different drift angles in deep water (h/T = 24) and shallow water (h/T = 1.2). The drift angle greatly affects the circumferential distribution of wake velocity. In the case of β = 0˚, U and W are symmetric, and V is antisymmetric. However, due to the presence of a thicker boundary layer in this region, as shown in Fig. 12(a), the magnitudes of U, V, and W are lower in shallow water. As the drift angle increases, U, V, and W are substantially altered by the oblique flow, which no longer shows a symmetric or antisymmetric pattern. The velocity fluctuations within the 0˚ – 180˚ phase angle are particularly evident, and this phenomenon is related to the flow separation. When the drift angle increases, the windward side is mainly controlled by the incoming flow, and a large amount of vortices leaks from the leeward side, which leads to a more inhomogeneous velocity field on the back side.

|

Fig. 16 Circumferential distribution of the wake velocity for r = 0.7R in h/T = 24 for three drift angles. (a), β = 0˚; (b), β = 10˚; (c), β = 20˚. |

|

Fig. 17 Circumferential distribution of the wake velocity for r = 0.7R in h/T = 1.2 for three drift angles. (a), β = 0˚; (b), β = 10˚; (c), β = 20˚. |

Fig. 18 depicts the circumferential distribution of axial velocity U, tangential velocity V, and radial velocity W at a drift angle of β = 20˚ for different water depths. In the range of the windward side, the circumferential distribution of U, V, and W is mainly controlled by the incoming flow, and their variations are not substantial. However, on the leeward side, strong flow separation occurs, leading to fluctuations in U, V, and W. Moreover, comparing Figs. 18(c) and 18(d) reveals their differences are minimal, indicating that the influence of the shallow-water effect is extremely small.

|

Fig. 18 Circumferential distribution of wake velocity for r = 0.7R in h/T = 24 for four water depths. (a), h/T = 1.2; (b), h/T = 1.5; (c), h/T = 3.0; (d), h/T = 24. |

This paper presents a numerical study on the hydrodynamic performance and hull wake of the international ship model KVLCC2 at oblique flow and shallow-water conditions. CFD simulations are conducted based on the RANS method and the SST k-ω turbulence model. Twenty operating conditions with drift angles of β = 0˚, 5˚, 10˚, 15˚, and 20˚ and water depths of h/T = 1.2, 1.5, 3.0, and 24 are considered. The numerical approach is validated by comparing the ship's resistance and wake in deep water between CFD and model tests, revealing a good agreement. The numerical results present the following conclusions: ⅰ) The shallow-water effect is strong and results in nonlinear increases in the longitudinal force regardless of drift angles and on the transverse force and yaw moment only for high drift angles. ⅱ) Shallow water has an evident influence on the wake distribution in the propeller plane. Specifically, shallow water results in an increase in the mean wake fraction for small drift angles while enhancing the strength of the aft-body vortex on the leeward side for large drift angels. The maneuverability of a ship operating in shallow water is related to its hydrodynamic forces and wake characteristics in shallow-water circumstances. Therefore, the present numerical findings imply that special attention should be given to the shallow-water effect when estimating the maneuverability of a ship in shallow water.

AcknowledgementThe study is supported by the National Key R & D Plan Project (No. 2019YFD0901003).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Longsheng Wang and Yuxin Zhang. The draft of the manuscript was written by Longsheng Wang and revised by Liang Feng, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Bechthold, J., and Kastens, M., 2020. Robustness and quality of squat predictions in extreme shallow water conditions based on RANS-calculations. Ocean Engineering, 197: 106780. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2019.106780 (  0) 0) |

CD-Adapco, 2014. User Guide STAR-CCM+ Version 9.0. 2. CIMNE, Munich, 1028-1039.

(  0) 0) |

Fureby, C., Toxopeus, S. L., Johansson, M., Tormalm, M., and Petterson, K., 2016. A computational study of the flow around the KVLCC2 model hull at straight ahead conditions and at drift. Ocean Engineering, 118: 1-16. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2016.03.029 (  0) 0) |

ITTC, 2002. Final report and recommendations to the 23rd ITTC. Proceeding of the 23rd ITTC. The Manoeuvring Committee, Venezia, 153-200.

(  0) 0) |

Kim, W. J., Van, S. H., and Kim, D. H., 2001. Measurement of flows around modern commercial ship models. Experiments in Fluids, 31(5): 567-578. DOI:10.1007/s003480100332 (  0) 0) |

Liu, X., and Wan, D., 2015. Numerical simulation of ship yaw maneuvering in deep and shallow water. International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference; International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers. Hawaii, ISOPE-I-15: 005.

(  0) 0) |

Meng, Q. J., 2020. Numerical simulations of viscous flow around the ship maneuvering in restricted waters. PhD thesis. Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

(  0) 0) |

Meng, Q. J., and Wan, D. C., 2016. Numerical simulations of viscous flow around the obliquely towed KVLCC2M model in deep and shallow water. Journal of Hydrodynamics, 28(3): 506-518. DOI:10.1016/S1001-6058(16)60655-8 (  0) 0) |

Okano, S., Karasuno, K., Maekawa, K., and Fukuhara, K., 2004. Applications of a component-type mathematical model to maneuvering hydrodynamic forces acting on a ship hull in shallow water. Journal of the Kansai Society of Naval Architects, 241: 83-88. (  0) 0) |

Oud, G., and Bedos, A., 2022. CFD investigation of the effect of water depth on manoeuvring forces on inland ships. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Marine Energy, 8(4): 489-497. DOI:10.1007/s40722-022-00253-y (  0) 0) |

PIANC, 1992. Overview of simulation techniques, capability of ship maneuvering simulation models for approach channels and fairway in harbours. Report of Working Group No. 20 of Permanent Technical Committee, II. General Secretariat of PIANC, Brussels, Belgium, 49.

(  0) 0) |

Su, S. J., Wu, Y. J., Xiong, Y. P., Guo, F. X., Liu, H. B., and Cheng, Q. X., 2023. Experiment and numerical simulation study on resistance performance of the shallow-water seismic survey vessel. Ocean Engineering, 279: 113889. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.113889 (  0) 0) |

Tian, X. M., 2008. A numerical and experimental research on the viscous hydrodynamic forces acting on a ship in manoeuvring motion. Master thesis. Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

(  0) 0) |

Toxopeus, S. L., Simonsen, C. D., Guilmineau, E., Visonneau, M., and Stern, F., 2011. Viscous-flow calculations for KVLCC2 in manoeuvring motion in deep and shallow water. NATO RTO AVT-189 Specialists Meeting on Assessment of Stability and Control Prediction Methods for NATO Air and Sea Vehicles, Portsdown West, UK, 29: 151-169.

(  0) 0) |

Toxopeus, S. L., Simonsen, C. D., Guilmineau, E., Visonneau, M., Xing, T., and Stern, F., 2013. Investigation of water depth and basin wall effects on KVLCC2 in manoeuvring motion using viscous-flow calculations. Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 18(4): 471-496. DOI:10.1007/s00773-013-0221-6 (  0) 0) |

Xing, T., Bhushan, S., and Stern, F., 2012. Vortical and turbulent structures for KVLCC2 at drift angle 0, 12, and 30 degrees. Ocean Engineering, 55: 23-43. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2012.07.026 (  0) 0) |

Xing, T., Shao, J., and Stern, F., 2007. BKW-RS-DES of unsteady vortical flow for KVLCC2 at large drift angles. 9th International Conference on Numerical Ship Hydrodynamics. Ann Arbor, Michigan, 5-8.

(  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y. X., Chen, K., and Jiang, D. P., 2020. CFD analysis of the lateral loads of a propeller in oblique flow. Ocean Engineering, 202: 107153. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2020.107153 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, X., Sutulo, S., and Soares, C. G., 2016. A paving algorithm for dynamic generation of quadrilateral meshes for online numerical simulations of ship manoeuvring in shallow water. Ocean Engineering, 122: 10-21. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2016.06.008 (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24