2) Laboratory for Marine Biology and Biotechnology, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266237, China;

3) Institute of Evolution and Marine Biodiversity, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China

Actin, the principal component of the microfilament, is one of the most highly conserved proteins. The discovery of actin structural homologs in bacteria and archaea indicates that actin-like polymers are used by cells across the tree of life (Gunning et al., 2015). Bacterial actin-like proteins are characterized with one filament one function, and many of them are not readily identified from sequencebased homology searches (Doi et al., 1988; Addinall and Lutkenhaus, 1996; Jensen and Gerdes, 1997). The actin family may undergo rampant expansion during eukaryotic evolution with members extremely well conserved in sequence (Gunning et al., 2015). For example, there are two cytoplasmic actins (β and γ) and four muscle actins (α-cardiac, α-skeletal, α-smooth and γ-smooth) in humans. The actin family contains not only conventional actin but also actin-related proteins (ARPs) that have high similarity with the conventional ones (Machesky and May, 2001). The ARPs have well characterized roles in actin polymerization (ARP2/3), dynein motor activity (ARP1 and ARP 10), and chromatin remodeling (ARP4, ARP5, ARP6, ARP8), while the functions of some 'orphan' ARPs are still unknown (Machesky and May, 2001; Goodson and Hawse, 2002).

Muscle linage is specified by the expression of muscle structure gene such as muscle actin (Carmen et al., 2015). The expression of muscle actin depends on the myogenic regulatory factors (MRF) including Myf5, MyoD, Mrf4 and Myogenin in vertebrates by binding to the E-box motif (Tapscott, 2005). In vertebrates, Myf5 (Braun et al., 1989) and MyoD (Sassoon et al., 1989) play redundant roles in myoblast specification in the dorsal or ventral dermomyotome respectively; and Mrf4 (Braun et al., 1990) and Myogenin (Edmondson and Olson, 1989) instruct myoblasts for terminal differentiation. The sine oculis related homeobox group (Six) are required in the formation and development of cardiac muscle progenitors in a combinatorial fashion (Grifone et al., 2005). In mammals, Six1, Six2, Six4, and Six5 have a similar binding specificity to consensus sequence AACCTGA (Ohto et al., 1999) and are able to activate the target genes such as Pax3, MyoD, Mrf4, and Myogenin in myogenesis (Grifone et al., 2005). In addition, Tbx6-related gene is expressed in cells of the muscle lineage in ascidians and is involved in the maintenance of transcriptional activity of muscle-specific structural genes (Takada et al., 2002). Tbx6 belongs to T-box gene family encoding transcription factors which includes Brachyury, Tbx1, Tbx2/3/4/5, Tbx6 and Tbr/Eomes/TBX21, that play critical roles in various processes of development, particularly, mesoderm formation in chordate embryos (Takatori et al., 2004).

There are at least three distinct muscle actin isoforms expressed in the larval tail muscle, adult body-wall muscle and adult heart muscle in ascidians (Chiba et al., 2003). In Styela clava, at least four different muscle actin genes encoding the same actin isoforms are expressed in the larval tail muscle cells (Beach and Jeffery, 1992). Little is known about the expression of muscle actin genes in adult heart muscle, although they seem to be different from those which are expressed in the larval tail muscle (Kusakabe, 1997). A maternally localized zinc-finger type transcription factor Macho-1 activated the expression of Tbx6 (Kobayashi et al., 2003), which in turn regulates several downstream muscle-specific genes in both Halocynthia and Ciona embryos (Sawada et al., 2005; Yagi et al., 2005). Ascidians express a single MRF member Mrf that is equally related by sequence to the four vertebrate MRFs (Meedel et al., 2007). In Ciona spp, knockdown of Mrf results in the loss of tail muscle myofibrils at early stages (Meedel et al., 2007); however, some unknown factors other than Mrf may regulate the expression of tail muscle actin gene in Halocynthia roretzi (Satou and Satoh, 1996).

In this study, we identified three actin genes from the transcriptome data of C. savignyi, of which two coded for muscle actin isoforms and one for cytoplasmic actin. We focused on a novel non-tail muscle actin gene, Cs-SMA, to explore its temporal and spatial expression and to identify the factors that regulate its expression.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Experimental AnimalsC. savignyi adults were collected from the coast of Qingdao and Rongcheng, Shandong Province, China. The animals were maintained under constant light to induce oocyte maturation in the laboratory. Eggs and sperm were obtained surgically from several adult gonad ducts and mixed for fertilization. Larvae were collected at 22, 26, and 66 hours post fertilization (hpf) for in situ hybridization.

2.2 Phylogenetic AnalysisThe sequences of actin and ARPs of C. savignyi were obtained from previous RNA-seq data (Wei et al., 2017). Those from additional six species (Homo sapiens, Xenopus laevis, Danio rerio, Ciona intestinalis, Branchiostoma belcheri, Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans and Arabidopsis thaliana) were obtained from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGAX using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method. The resulting tree was graphed by the program in MEGAX, and was prepared for presentation by Adobe Illustrator 2018.

2.3 Whole-Mount in situ HybridizationThe Cs-SMA probe sequence was from coding region (86 bp – 691 bp) and was amplified with primers Cs-SMAF 5' CCGTCTTTCCATCCATCG 3' and Cs-SMA-R 5' CA GCGGTGCTCATTTCTT 3'. Digoxigenin-11-UTP (Roche, Germany)-labeled probes were synthesized by Sp6 or T7 RNA polymerase following the general protocol of the DIG RNA labeling kit (SP6/T7) (Roche, Germany). Probes were treated with DNase, extracted by ethanol precipitation, and used to examine gene expression in ascidian larval samples. The larvae were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.5 mol L−1 NaCl-MOPS (pH 7.0) buffer overnight at 4℃ and then permeabilized by digested with 12 μg mL−1 Proteinase K at 37℃ for 30 min. Subsequently, in situ hybridization was performed at 56℃ with 1 ng μL−1 antisense or sense Digoxigenin-11-UTP labeled probes. After hybridization, samples were washed in gradient saline-sodium citrate at the hybridization temperature. Finally, samples were incubated with anti-DIG-Alkaline Phosphatase antibody at a 1:2000 dilution and developed with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) (Roche, Germany).

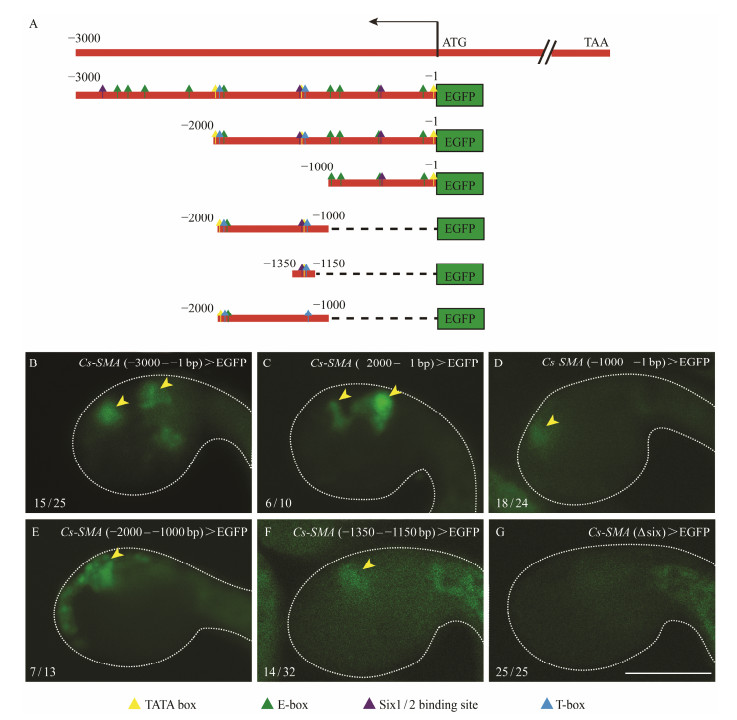

2.4 Generating GFP Reporter Constructs and Transfering Genes with ElectroporationPCR-amplified DNA fragments from 5' flanking sequence of gene Cs-SMA were cloned into pEGFP-C/N vectors using the One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, China) to produce reporter plasmids Cs-SMA (−3000 – −1 bp) > EGFP, Cs-SMA (−2000 – −1 bp) > EGFP, Cs-SMA (−1000 – −1 bp) > EGFP, Cs-SMA (−2000 – −1000 bp) > EGFP, Cs-SMA (−1350 – −1150 bp) > EGFP, respectively. Cs-SMA (∆Six) > EGFP were generated by internal deletion of Six1/2 binding motif on the base of Cs-SMA (−2000 – −1000 bp) > EGFP. PCRamplified DNA fragments from 5' flanking sequence of gene Six1/2 with specific primers were cloned into pEGFP-C/N vectors using the One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, China) to produce plasmids Cs-Six1/2 (−3000 – −1 bp) > EGFP. Then tdtomato replaced EGFP to generate the Cs-Six1/2 (−3000 – −1 bp) > tdtomato. Plasmids Cs-Mesp > tdtomato was constructed using the same way as above. All the primers used were listed in Table 1.

|

|

Table 1 Primers used in this study |

Eggs and sperm were obtained surgically from several adult gonad ducts and mixed for 5 min. Then the fertilized eggs were dechorionated in seawater with 1% sodium thioglycolate (Sigma, America) and 0.5% proteinase E (Sigma, America) and reared at 18℃ in Millipore-filtered seawater in agar-coated dishes for further development. For electroporation, 300 μL eggs were mixed with 500 μL mixture of 0.77 mol L−1 mannitol (Sigma, America) and 30 μg DNA in 0.4 cm electroporation cuvette. After electroporation at 2000 μF capacitance, 50 V voltage with Gene Pulser XcellTM (Bio-Rad Laboratories), the eggs were immediately resuspended in fresh seawater and cultured for development.

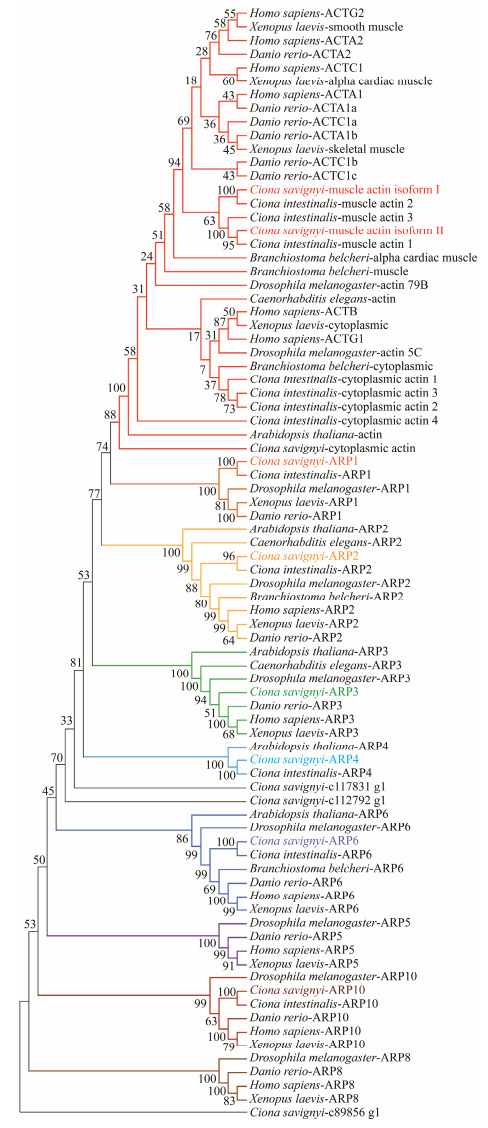

3 Results 3.1 Identification of Actin Encoding Genes in C. savignyiBased on the previously constructed cDNA libraries and the sequenced transcriptome from C. savignyi, we identified three conventional actin isoforms and nine ARPs by sequence blast. Phylogenetic analysis was performed to define evolutionary relationships of these identified actin isoforms and ARPs among C. savignyi and other fully sequenced organisms, including H. sapiens, X. laevis, D. rerio, D. melanogaster, C. intestinalis, B. belcheri, C. elegans and A. thaliana. The results showed that the actin superfamily contained at least nine subfamilies including the conventional actin subfamily and ARP subfamilies (Fig.1). At least one protein was characterized in C. savignyi for most of subfamilies, but no transcript were identified for Arp5 and Arp8 subfamily. Six ARPs encoding genes were grouped into Arp1, Arp2, Arp3, Arp4, Arp6 and Arp10 subfamilies, respectively. Three additional 'orphan' ARPs were identified, which were not grouped into any subfamilies. Two conventional actin encoding genes were grouped into chordate muscle actin, and one was grouped with cytoplasmic actin. The molecular phylogenetic analyses showed that the muscle actin isoforms from vertebrates were more closely related to each other than to their counterparts from the ascidians.

|

Fig. 1 Phylogenetic analysis of actin proteins and actin related proteins from vertebrates and invertebrates. Full lengths of actin protein sequences were aligned using the ClustalW program. The bootstrap test of phylogeny was performed with 1000 replicates to construct phylogenetic tree with neighbor-joining (NJ) method of MEGAX. The actin proteins and actin related proteins identified from C. savignyi are shown in different color. |

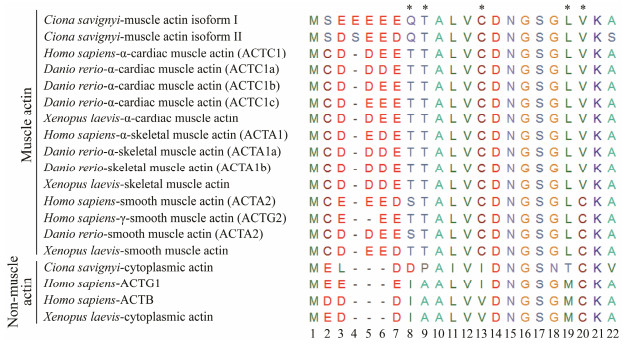

The actin family is an ancient and highly conserved group of proteins (Goodson and Hawse, 2002). Typing actin mostly relies on the length and highly variable sequence of the N-terminal regions among actin isoforms and in different species, and comparison of the diagnostic amino acids (Vandekerckhove and Weber, 1978c, 1978a, 1978b, 1981, 1984). We aligned the predicted amino acid sequence of two ascidian muscle actin isoforms against actins from other metazoans. The alignment suggested that they were more closely related to zebrafish and human cardiac and skeletal muscle actin with more than 96% identity. The alignment of N-terminal amino acid sequences of muscle actin from ascidians and other chordates reveals that Ciona muscle actin isoforms contain the characteristics of cardiac and skeletal muscle actin. These two Ciona muscle actin isoforms represented a cluster of more than four acidic amino acids (Glu) following the first two amino acids in the very end of N-terminus, similar to their counterparts in other species. However, they were distinct from the cytoplasmic actin characterized by no more than three successive acidic amino acids next to the first Met residue. In addition, muscle actin isoforms are different from smooth muscle actin by adopting Leu and Val at positions 19 and 20 (Fig.2), rather than Leu andc Cys in smooth muscle actin. The actin isoform II was similar to muscle actin expressed in the tail region of the ascidians based on the identical diagnostic residues (Table 2). In contrast, the isoform I distinguished it from tail muscle actin by different amino acids at position 103 and 176. It showed high similarity with C. intestinalis muscle actin 2 which is highly expressed in the adult heart and also in the body-wall muscle (Chiba et al., 2003). Therefore, we mainly focused on the muscle actin isoform I and aimed to uncover its expression pattern.

|

Fig. 2 N-terminal sequence alignment of multiple isoforms of actin from different species. Three types of actin are from C. Savignyi (muscle actin isoform I, muscle actin isoform II, and cytoplasmic actin); six from H. sapiens (ACTC1, ACTA1, ACTA2, ACTG2, ACTG1, ACTB); six from D. rerio (ACTC1a, ACTA1a, ACTC1b, ACTA1b, ACTA2, ACTC1c); and four from X. laevis (alpha cardiac muscle actin, smooth muscle actin, skeletal muscle actin, cytoplasmic actin). Amino acids are represented by a single letter code. Dashes represent gaps introduced into the sequence to optimize alignment. Diagnostic amino acids that distinguish the muscle actin from cytoplasmic actin are indicated by asterisks. The order numbers indicate the positions of amino acids from the beginning. |

|

|

Table 2 Comparison of diagnostic amino acid residues in ascidian and vertebrate actins |

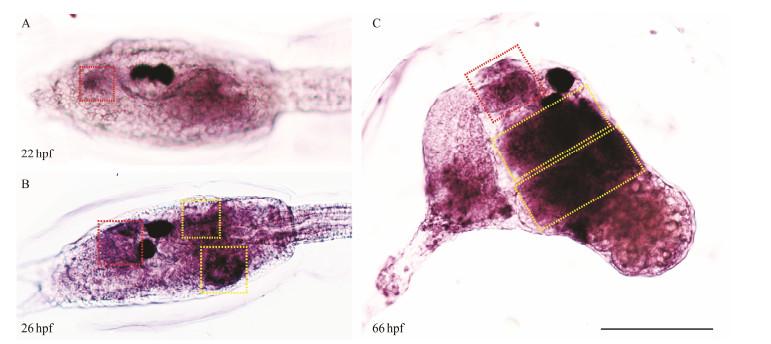

To examine the temporal and spatial expression of C. savignyi muscle actin isoform I, we performed in situ hybridization to detect its expression pattern in the Ciona larva. The expression of C. savignyi muscle actin isoform I appeared as early as 22 hpf at the anterior and posterior trunk in Ciona larvae in accordance with the location of oral and atrial siphon primordium, respectively (Fig.3A). At 26 hpf, muscle actin isoform I was clearly detected to express at the primordia of one oral siphon and two contralateral atrial siphons of the trunk when the siphon placodes began to invaginate (Fig.3B). After metamorphosis, the larvae tails were retracted and the siphon primordium formed tubular structure for feeding, when C. savignyi muscle actin isoform I was detected at the oral and two converging atrial siphons (Fig.3C). Based on the in situ hybridization data, we concluded that the muscle actin isoform 1 expressed at the oral and atrial siphon primordia and we hereby defined it as siphon-specific muscle actin coding gene (Cs-SMA).

|

Fig. 3 Expression patterns of Cs-SMA in Ciona larvae and juveniles. The expression of Cs-SMA possibly appears in the oral siphon at 22 hpf (A). The expression of Cs-SMA shows in the invaginating oral and atrial siphon at 26 hpf (B). The expression of Cs-SMA shows in the tubular oral and atrial siphon at 66 hpf (C). Red box indicates the oral siphon and yellow box indicates the atrial siphon. Scale bar represented 100 μm. |

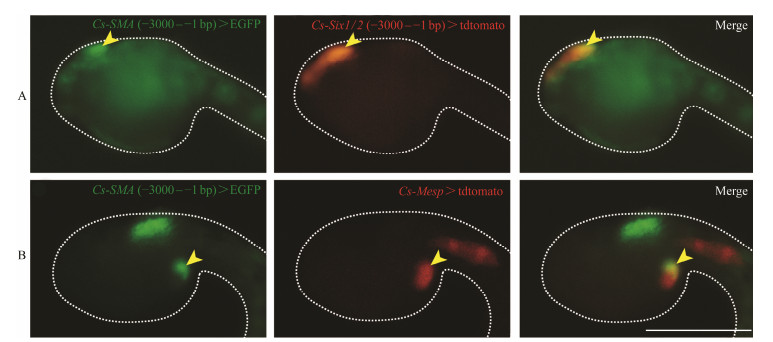

To further confirm the expression of Cs-SMA in Ciona larvae, we carried out the promoter driven GFP fusion constructs assay. The proximal upstream flanking regions of the Cs-SMA, including −3000 – −1 bp and −5000 – −1 bp, were fused to GFP and transferred into the fertilized eggs electroporation. We found that −3000 – −1 bp fragment was efficient to convey specific expression. In order to further confirm the expression pattern of Cs-SMA, we co-electroporated Cs-SMA promoter reporter with two known transcription factors Six1/2 and Mesp promoter reporter, which express at the oral siphon primordium and atrial siphon precursor cells that share the common cellular origin with cardiac primordium, respectively (Mazet et al., 2005; Abitua et al., 2015; Liu and Satou, 2019). The expression domains overlapped between Cs-SMA and the transcription factors Six1/2 and Mesp (Figs.4A, B). Taken together, we concluded that Cs-SMA is expressed at the primordia of oral and atrial siphon.

|

Fig. 4 Expression of Cs-SMA overlapped with Six1/2 and Mesp. (A) Both of the Cs-SMA and Six1/2 expressed at the oral siphon detected by GFP reporter, when Cs-SMA (−3000 – −1 bp) > EGFP and Cs-Six1/2 (−3000 – −1 bp) > tdtomato co-electroporated into the embryos. (B) The expression of Cs-SMA and Mesp overlapped at cardiac primordium which generates atrial siphon. when Cs-SMA (−3000 – −1 bp) > EGFP and Cs-Mesp > tdtomato co-electroporated into the embryos. The different expression pattern of Cs-SMA driven by promoter sequence −3000 – −1 bp are caused by mosaic development of ascidians. Figs.A and B represent two typical expression patterns, i.e., signal at the oral siphon or at the primordium of atrial siphon. Scale bar represents 100 μm. |

Computational prediction with JASPAR database of the effective transcription factor binding profiles from 0 to −3000 bp upstream of Cs-SMA showed that it contained duplicate muscle related cis-regulatory elements such as E-box, T-box and Six1/2 binding motif. To analyze the core cis-regulatory region, we constructed a series of truncated promoters by progressively deleting 1000 bp. It was worth noticing that we kept at least one copy of the above cis-regulatory element in the truncated promoters. The −2000 – −1 bp sequence drove the expression of GFP reporter gene at the oral or atrial siphon primordia as the same level as the −3000 – −1 bp sequence but was higher than the −1000 – −1 bp sequence (Figs.5B –D). Sequence −2000 – −1000 bp was confirmed to play fundamental roles in driving the expression of Cs-SMA (Fig.5E). Three conserved cis-regulatory elements, the classical muscle determinants E-box, T-box, and the Six1/2 binding motif were present in the sequence −2000 – −1000 bp. A truncated 201 bp sequence containing Six1/2 motif and T-box could drive the GFP expression at oral or atrial siphon at relatively low level (Fig.5F). In contrast, an internal deletion of Six1/2 motif from the promoter region −2000 – −1000 bp caused a specific loss of expression at siphons (Fig.5G). These results indicated that Six1/2 was necessary in controlling the siphon-specific expression of Cs-SMA.

|

Fig. 5 Expression patterns of Cs-SMA driven by different promoter truncations. (A) Schematic diagrams of truncated upstream sequences containing duplicate cis-elements. (B) GFP expression driven by promoter −3000 – −1 bp. 15/25 indicates 15 embryos represent GFP signal out of 25 embryos counted. (C) GFP expression driven by promoter −2000 – −1 bp, 6 out of 10 embryos show GFP signal. (D) GFP expression driven by promoter −1000 – −1 bp, 18 out of 24 embryos show GFP signal. (E) GFP expression driven by promoter −2000 – −1000 bp, 7 out of 13 embryos show GFP signal. (F) GFP expression driven by promoter −1350 – −1150 bp, 14 out of 32 embryos show GFP signal. (G) GFP expression driven by promoter −1350 – −1150 bp with internal deletion of Six1/2 binding site. No GFP expression in the trunk of the embryo out of 25 embryos counted. Arrowhead indicates the location of siphons. The GFP signals in the tail of embryos (F and G) are autofluorescence from tail muscle. Scale bar represent 100 μm. |

Actin, like many contractile protein genes, is encoded by a multigene family. It was postulated that an ancestral actin gene duplicated and gave rise to a cytoplasmic isoform and a muscle isoform (Kovilur et al., 1993; Kusakabe et al., 1999; Chiba et al., 2003). The muscle isoform underwent a second duplication resulting in striated muscle actin (skeletal and cardiac) and smooth muscle actin, respectively (Miwa et al., 1991). Our evolutionary analysis for actin subfamily based on the construction of phylogenetic tree, as well as the comparison of N-terminal sequences and diagnostic residues of the encoded proteins, suggested that the muscle and non-muscle subfamily arose by divergence prior to the vertebrate origin from a single common ancestral gene. The muscle actin isoforms from subphylum urochordate grouped together and were distinct from vertebrates, and so did muscle actins from cephalochordate. These suggested that vertebrate muscle actin gene family was established after the divergence of the vertebrate and urochordate and cephalochordate lineages.

Ascidians present three muscle actin types and the expression of each isoform characterizes a specific developmental stage or tissue during their life cycle: striated muscle actin in the tail, striated muscle actin in the adult heart, and non-striated muscle (commonly called smooth muscle) actin in the adult body-wall (Shinohara and Konishi, 1982; Nevitt and Gilly, 1986; Terakado and Obinata, 1987; Crowther and Whittaker, 1996; Chiba et al., 2003). The deduced three actin isoforms of C. savignyi fall to the striated muscle actin group and cytoplasmic actin group, respectively. The striated muscle actin isoform II was suspected to express in the tail region based on its high expression level (700 times more than Cs-SMA) and the composition of diagnostic amino acids (Table 1). Given its location, locomotory function, and ultrastructure, ascidian larval tail muscle actin is clearly homologous to vertebrate skeletal muscle actin (Meedel, 1997). Cs-SMA distinguished it clearly from cytoplasmic actin by the number of acidic amino acids and amino acid composition in N-terminal sequence (Fig.2). It presents high similarity with C. intestinalis muscle actin 2 which is almost exclusively expressed in the adult heart and also in adult body-wall muscle based on the comparison of diagnostic amino acids (Table 1) (Chiba et al., 2003). The muscle actin genes expressed in larval or adult heart muscle seem to be different from those expressed in the larval tail muscle (Kusakabe, 1997). Our results showed that Cs-SMA was clearly distinct from the tail muscle actin based on the comparison of diagnostic residues and the expression pattern. We did not identify any smooth muscle actin, perhaps because the transcriptome database of C. savignyi was from embryos before 42 hpf when they did not develop any adult muscle actin. The study of the different musculatures during the complete cycle of ascidians can be of interest from developmental and evolutionary perspectives, especially considering that the tunicates are the closest group to vertebrates (Delsuc et al., 2006).

ARPs, together with conventional actin, belong to the ancient and divergent actin superfamily (Frankel and Mooseker, 1996). All proteins in this superfamily form four conserved actin-like subdomains and contain a five-stranded beta sheet of identical topology, suggesting that the molecules may have evolved by gene duplication (Kabsch and Holmes, 1995). ARPs are clearly divergent from each other though the subfamilies of ARPs are conserved and can be recognizable among all eukaryotes (Muller et al., 2005). In this study, seven ARPs encoding genes from C. savignyi larvae were grouped into Arp1, Arp2, Arp3, Arp4, Arp6 and Arp10 subfamilies but no gene was identified for Arp5 and Arp8 subfamily. Previous studies have revealed that Arp5 and Arp8 are essential for chromatin remodeling including DNA binding, nucleosome mobilization and ATPase activity (Shen et al., 2003), so whether such activities were undertaken by other members of ARP subfamily needs further experiments to study. Three additional 'orphan' ARPs did not belong to any of these subfamilies, which suggested that there might be some unclassified ARPs whose features and functions have not yet been explored (Schafer and Schroer, 1999; Machesky and May, 2001).

4.2 Confined Expression of Cs-SMA in C. savignyiAnalysis of the effective promotor region from 0 to −3000 bp upstream of Cs-SMA showed that it contains duplicate muscle determinant cis-regulatory elements such as TATAbox, E-box, T-box and six1/2 binding motif, which may explain why sequence −2000 – −1000 bp was sufficient to direct the expression of Cs-SMA. It is conceivable that a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) regulatory factor, such as MyoD family, recognizes the E-box motif to induct the muscle transcriptional program. In Ciona spp., Mrf is the sole member of the MyoD family and is required for larval tail muscle development (Meedel et al., 2007). In the current study, a 201 bp sequence without Mrf binding motif E-box did not hamper the expression pattern of Cs-SMA, indicating that E-box is dispensable in controlling siphonspecific muscle actin expression in the early development embryos. This is consistent with the expression pattern of Mrf, whose transcripts are restricted to larval tail muscle precursors but not detectable in the cardiac lineage prior to settlement (Razy-Krajka et al., 2014). The lower level expression driven by the 201 bp promoter (−1350 – −1000 bp) may be the missing of fragment (−2000 – −1351 bp) compared with expression level driven by the promoter −2000 – −1000 bp. A further validation was needed to find out the functional elements.

Six family consists of Six1/2, Six3/6 and Six4/5 subfamilies. In deuterostomes, both Six1/2 and Six3/4 members and their cofactor Eya are involved in the formation of the myogenic lineage (Carmen et al., 2015). The Six-Eya transcription complex works in parallel with Pax3 and Pax7 factors which are expressed in muscle satellite cells and share with vertebrates a conserved role in muscle formation (Carmen et al., 2015). In C. intestinalis, the expression of Six1/2 was confined to oral siphon progenitor cells in mid-tailbud embryos, while its expression was activated in endoderm and in several lateral ectodermal domains in late-tailbud embryos. In larvae, the expression of Six1/2 could be detected in the invaginated oral siphon and atrial siphon primordia (Mazet et al., 2005). The confined expression of Cs-SMA at the oral and atrial siphon under the 201 bp promoter mostly depends on the existence of Six1/2 binding motif. As Six1/2 showed the same expression pattern of Cs-SMA, we propose that Six1/2 is the main trans-acting factor controlling Cs-SMA expression.

5 ConclusionsAs shown in the present study, a siphon-specific muscle actin coding gene (Cs-SMA) was identified from the RNA-seq data of Ciona savignyi embryos. It had high similarity with vertebrate cardiac and skeletal muscle actin. Cs-SMA is expressed at the primordia of oral and atrial siphon. And Six1/2 was necessary in controlling the siphonspecific expression of Cs-SMA.

AcknowledgementsThis research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2019YFE019 0900, 2018YFD0900705).

Abitua, P. B., Gainous, T. B., Kaczmarczyk, A. N., Winchell, C. J., Hudson, C., Kamata, K., et al., 2015. The pre-vertebrate origins of neurogenic placodes. Nature, 524: 462-465. DOI:10.1038/nature14657 (  0) 0) |

Addinall, S. G., and Lutkenhaus, J., 1996. FtsA is localized to the septum in an FtsZ-dependent manner. Journal of Bacteriology, 178: 7167. DOI:10.1128/jb.178.24.7167-7172.1996 (  0) 0) |

Beach, R. L., and Jeffery, W. R., 1992. Multiple actin genes encoding the same α-muscle isoform are expressed during ascidian development. Developmental Biology, 151: 55-66. DOI:10.1016/0012-1606(92)90213-Z (  0) 0) |

Braun, T., Bober, E., Winter, B., Rosenthal, N., and Arnold, H. H., 1990. Myf-6, a new member of the human gene family of myogenic determination factors: Evidence for a gene cluster on chromosome 12. The EMBO Journal, 9: 821-831. DOI:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08179.x (  0) 0) |

Braun, T., Buschhausen-Denker, G., Bober, E., Tannich, E., and Arnold, H. H., 1989. A novel human muscle factor related to but distinct from MyoD1 induces myogenic conversion in 10T1/2 fibroblasts. The EMBO Journal, 8: 701-709. DOI:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03429.x (  0) 0) |

Carmen, A., and Maria Ina, A., 2015. Too many ways to make a muscle: Evolution of GRNs governing myogenesis. Zoologischer Anzeiger – A Journal of Comparative Zoology, 256: 2-13. DOI:10.1016/j.jcz.2015.03.005 (  0) 0) |

Chiba, S., Awazu, S., Itoh, M., Chin-Bow, S. T., Satoh, N., Satou, Y., et al., 2003. A genomewide survey of developmentally relevant genes in Ciona intestinalis. Development Genes and Evolution, 213: 291-302. DOI:10.1007/s00427-003-0324-x (  0) 0) |

Crowther, R. J., and Whittaker, J. R., 1996. Developmental biology of ascidians. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 198: 147-148. DOI:10.1016/0022-0981(96)02531-2 (  0) 0) |

Delsuc, F., Brinkmann, H., Chourrout, D., and Philippe, H., 2006. Tunicates and not cephalochordates are the closest living relatives of vertebrates. Nature, 439: 965-968. DOI:10.1128/jb.170.10.4619-4624.1988 (  0) 0) |

Doi, M., Wachi, M., Ishino, F., Tomioka, S., Ito, M., Sakagami, Y., et al., 1988. Determinations of the DNA sequence of the mreB gene and of the gene products of the mre region that function in formation of the rod shape of Escherichia coli cells. Journal of Bacteriology, 170: 4619,DOI: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4619-4624.1988.

(  0) 0) |

Edmondson, D., and Olson, E., 1989. A gene with homology to the myc similarity region of MyoD1 is expressed during myogenesis and is sufficient to activate the muscle differentiation program. Genes & Development, 3: 628-640. DOI:10.1101/gad.3.5.628 (  0) 0) |

Frankel, S., and Mooseker, M. S., 1996. The actin-related proteins. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 8: 30-37. DOI:10.1016/S0955-0674(96)80045-7 (  0) 0) |

Goodson, H. V., and Hawse, W. F., 2002. Molecular evolution of the actin family. Journal of Cell Science, 115: 2619. DOI:10.1080/15216540290106495 (  0) 0) |

Grifone, R., Demignon, J., Houbron, C., Souil, E., Niro, C., Seller, M. J., et al., 2005. Six1 and Six4 homeoproteins are required for Pax3 and Mrf expression during myogenesis in the mouse embryo. Development, 132: 2235. DOI:10.1242/dev.01773 (  0) 0) |

Gunning, P. W., Ghoshdastider, U., Whitaker, S., Popp, D., and Robinson, R. C., 2015. The evolution of compositionally and functionally distinct actin filaments. Journal of Cell Science, 128: 2009. DOI:10.1242/jcs.165563 (  0) 0) |

Jensen, R. B., and Gerdes, K., 1997. Partitioning of plasmid R1.The ParM protein exhibits ATPase activity and interacts with the centromere-like ParR-parC complex. Journal of Molecular Biology, 269: 505-513. DOI:10.1006/jmbi.1997.1061 (  0) 0) |

Kabsch, W., and Holmes, K. C., 1995. The actin fold. FASEB Journal, 9: 167-174. DOI:10.1096/fasebj.9.2.7781919 (  0) 0) |

Kobayashi, K., Sawada, K., Yamamoto, H., Wada, S., Saiga, H., and Nishida, H., 2003. Maternal macho-1 is an intrinsic factor that makes cell response to the same FGF signal differ between mesenchyme and notochord induction in ascidian embryos. Development, 130: 5179. DOI:10.1242/dev.00732 (  0) 0) |

Kovilur, S., Jacobson, J. W., Beach, R. L., Jeffery, W. R., and Tomlinson, C. R., 1993. Evolution of the chordate muscle actin gene. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 36: 361-368. DOI:10.1007/BF00182183 (  0) 0) |

Kusakabe, R., Satoh, N., Holland, L. Z., and Kusakabe, T., 1999. Genomic organization and evolution of actin genes in the amphioxus Branchiostoma belcheri and Branchiostoma floridae. Gene, 227: 1-10. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00608-8 (  0) 0) |

Kusakabe, T., 1997. Ascidian actin genes: Developmental regulation of gene expression and molecular evolution. Zoological Science, 14: 707-718. DOI:10.2108/zsj.14.707 (  0) 0) |

Liu, B., and Satou, Y., 2019. Foxg specifies sensory neurons in the anterior neural plate border of the ascidian embryo. Nature Communications, 10: 4911. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-12839-6 (  0) 0) |

Machesky, L., and May, R., 2001. Arps: Actin-related proteins. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation, 32: 213-229. DOI:10.1007/978-3-540-46560-7_15 (  0) 0) |

Mazet, F., Hutt, J. A., Milloz, J., Millard, J., Graham, A., and Shimeld, S. M., 2005. Molecular evidence from Ciona intestinalis for the evolutionary origin of vertebrate sensory placodes. Developmental Biology, 282: 494-508. DOI:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.021 (  0) 0) |

Meedel, T. H., 1997. Development of ascidian muscles and their evolutionary relationship to other chordate muscle types. In: Reproductive Biology of Invertebrates, Vol. 7: Progress in Developmental Biology. Collier, J. R., ed., Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, 345pp.

(  0) 0) |

Meedel, T. H., Chang, P., and Yasuo, H., 2007. Muscle development in Ciona intestinalis requires the b-HLH myogenic regulatory factor gene Ci-MRF. Developmental Biology, 302: 333-344. DOI:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.043 (  0) 0) |

Miwa, T., Manabe, Y., Kurokawa, K., Kamada, S., Kanda, N., Bruns, G., et al., 1991. Structure, chromosome location, and expression of the human smooth muscle (enteric type) gammaactin gene: Evolution of six human actin genes. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 11: 3296. DOI:10.1128/MCB.11.6.3296 (  0) 0) |

Muller, J., Oma, Y., Vallar, L., Friederich, E., Poch, O., and Winsor, B., 2005. Sequence and comparative genomic analysis of actin-related proteins. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 16: 5736-5748. DOI:10.1091/mbc.e05-06-0508 (  0) 0) |

Nevitt, G., and Gilly, W. F., 1986. Morphological and physiological properties of non-striated muscle from the tunicate, Ciona intestinalis: Parallels with vertebrate skeletal muscle. Tissue and Cell, 18: 341-360. DOI:10.1016/0040-8166(86)90055-8 (  0) 0) |

Ohto, H., Kamada, S., Tago, K., Tominaga, S. I., Ozaki, H., Sato, S., et al., 1999. Cooperation of Six and Eya in activation of their target genes through nuclear translocation of Eya. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 19: 6815. DOI:10.1128/MCB.19.10.6815 (  0) 0) |

Razy-Krajka, F., Lam, K., Wang, W., Stolfi, A., Joly, M., Bonneau, R., et al., 2014. Collier/OLF/EBF-dependent transcriptional dynamics control pharyngeal muscle specification from primed cardiopharyngeal progenitors. Developmental Cell, 29: 263-276. DOI:10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.001 (  0) 0) |

Sassoon, D., Lyons, G., Wright, W. E., Lin, V., Lassar, A., Weintraub, H., et al., 1989. Expression of two myogenic regulatory factors myogenin and MyoDl during mouse embryogenesis. Nature, 341: 303-307. DOI:10.1038/341303a0 (  0) 0) |

Satou, Y., and Satoh, N., 1996. Two cis-regulatory elements are essential for the muscle-specific expression of an actin gene in the ascidian embryo. Development Growth & Differentiation, 38: 565-573. DOI:10.1046/j.1440-169X.1996.t01-1-00013.x (  0) 0) |

Sawada, K., Fukushima, Y., and Nishida, H., 2005. Macho-1 functions as transcriptional activator for muscle formation in embryos of the ascidian Halocynthia roretzi. Gene Expression Patterns, 5: 429-437. DOI:10.1016/j.modgep.2004.09.003 (  0) 0) |

Schafer, D. A., and Schroer, T. A., 1999. Actin-related proteins. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 15: 341-363. DOI:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.341 (  0) 0) |

Shen, X., Ranallo, R., Choi, E., and Wu, C., 2003. Involvement of actin-related proteins in ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Molecular Cell, 12: 147-155. DOI:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00264-8 (  0) 0) |

Shinohara, Y., and Konishi, K., 1982. Ultrastructure of the bodywall muscle of the ascidian Halocynthia roretzi: Smooth muscle cell with multiple nuclei. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 221: 137-142. DOI:10.1002/jez.1402210203 (  0) 0) |

Takada, N., Satoh, N., and Swalla, B. J., 2002. Expression of Tbx6, a muscle lineage T-box gene, in the tailless embryo of the ascidian Molgula tectiformis. Development Genes and Evolution, 212: 354-356. DOI:10.1007/s00427-002-0247-y (  0) 0) |

Takatori, N., Hotta, K., Mochizuki, Y., Satoh, G., Mitani, Y., Satoh, N., et al., 2004. T-box genes in the ascidian Ciona intes-

(  0) 0) |

tinalis: Characterization of cDNAs and spatial expression. Developmental Dynamics, 230: 743-753, DOI: 10.1002/dvdy.20082.

(  0) 0) |

Tapscott, S. J., 2005. The circuitry of a master switch: Myod and the regulation of skeletal muscle gene transcription. Development, 132: 2685. DOI:10.1242/dev.01874 (  0) 0) |

Terakado, K., and Obinata, T., 1987. Structure of multinucleated smooth muscle cells of the ascidian Halocynthia roretzi. Cell and Tissue Research, 247: 85-94. DOI:10.1007/BF00216550 (  0) 0) |

Vandekerckhove, J., and Weber, K., 1978a. Actin amino-acid sequences. European Journal of Biochemistry, 90: 451-462. DOI:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12624.x (  0) 0) |

Vandekerckhove, J., and Weber, K., 1978b. At least six different actins are expressed in a higher mammal: An analysis based on the amino acid sequence of the amino-terminal tryptic peptide. Journal of Molecular Biology, 126: 783-802. DOI:10.1016/0022-2836(78)90020-7 (  0) 0) |

Vandekerckhove, J., and Weber, K., 1978c. Mammalian cytoplasmic actins are the products of at least two genes and differ in primary structure in at least 25 identified positions from skeletal muscle actins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 75: 1106-1110. DOI:10.1073/pnas.75.3.1106 (  0) 0) |

Vandekerckhove, J., and Weber, K., 1981. Actin typing on total cellular extracts. European Journal of Biochemistry, 113: 595-603. DOI:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05104.x (  0) 0) |

Vandekerckhove, J., and Weber, K., 1984. Chordate muscle actins differ distinctly from invertebrate muscle actins: The evolution of the different vertebrate muscle actins. Journal of Molecular Biology, 179: 391-413. DOI:10.1016/0022-2836(84)90072-X (  0) 0) |

Wei, J., Wang, G., Li, X., Ren, P., Yu, H., and Dong, B., 2017. Architectural delineation and molecular identification of extracellular matrix in ascidian embryos and larvae. Biology Open, 6: 1383. DOI:10.1242/bio.026336 (  0) 0) |

Yagi, K., Takatori, N., Satou, Y., and Satoh, N., 2005. Ci-Tbx6b and Ci-Tbx6c are key mediators of the maternal effect gene Ci-macho1 in muscle cell differentiation in Ciona intestinalis embryos. Developmental Biology, 282: 535-549. DOI:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.029 (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21