2) Collaborative Innovation Center for Marine Food Deep Processing Dalian Polytechnic University, Dalian 116034, China

Abalone is a popular food because of its special texture, delicious taste and rich nutrition. An ever-increasing demand motivates the development of abalone aquaculture industry and annual increment of abalone production. In 2020, the production of abalone reached more than 200000 tons in China, and 76% of it came from Fujian Province (Wang and Wu, 2021). Though dried abalones reveal more unique flavor and taste, the process is time-consuming. Furthermore, fresh abalones are favored by consumers over dried ones for convenience in processing. With the fast development of cold chain logistics in China, the consumption area of abalone is enlarging. Cold storage is the most used method for storing fresh abalone, effectively prolong its shelf life and preserve good taste during transportation.

Free amino acids (FAAs) are major factors characterizing the taste of abalone (Brown et al., 2009). Taste-active amino acids such as glycine (Gly) and alanine (Ala) provide both sweetness and umami. Arginine (Arg) imparts slightly bitter but intensify thickened the whole flavor of abalone (Chiou and Lai, 2002). During cold storage of abalone, proteins are degraded to peptides by proteinases, such as matrix metalloproteinases and cathepsins (Tjáderhane et al., 2013). FAAs are then released by further degradation of various peptides (Azarnia et al., 2011).

Among enzymes responsible for FAAs production, aminopeptidases (APs) play critical roles as they prefer to remove amino acid residues from the N-terminal of peptides or polypeptides. APs are sorted for their enzymatic activity based on their preference for the N-terminal amino acid of the substrate, their position, sensitivity to inhibitors, and demand for divalent metal ions (Taylor, 1993; Li, 2015). Aminopeptidase A can only specifically hydrolyze the N-terminal first amino acid peptide (aspartic acid or glutamate). Leucine aminopeptidase has the highest hydrolysis efficiency for substrates with leucine at the N-terminus. Similarly, lysine aminopeptidase can effectively hydrolyze peptides with lysine and arginine at the N-terminus. The active center of aminopeptidase contains 1-2 metal ion(s), which play an important role in catalyzing and stabilizing protein structure.

FAAs released by the action of AP on peptides are significant for both taste and nutrition. Therefore, APs have attracted considerable attention due to their functions in the generation of FAAs and hydrolysis of bitter peptides, which would consequently improve flavor of the final products. During the process of ham drying, APs are major producers to the liberation of FAAs (Toldrá et al., 2000). Immobilized chicken intestinal mucosa was used as an AP source for debittering protein hydrolysates (Damle, 2010). Cheese treated with higher concentration of recombinant Leu-AP from Lactobacillus rhamnosus S93 revealed remarkably higher levels of soluble nitrogen and total FAAs during ripening, strongly suggesting the critical role of AP in the production of FAAs (Azarnia et al., 2011).

Though abalones are widely consumed in many countries, especially in China, little information is available regarding AP in abalone and its direct contribution to taste. Therefore, the purpose of this work is to investigate the relevance of AP activity and the accumulation of FAAs in abalone muscle during cold storage with a purpose to elucidate the relationship between AP and the generation of FAAs.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Materials 2.1.1 ChemicalsDEAE-Sepharose, Sephacryl S-300 and Phenyl-Sepharose were bought from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1, 10-phenanthroline monohydrate, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), ethylene glycol-bis (2-aminoethylether)-N, N, N, N-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), mixed amino acids standard, and bestatin hydrochloride were products of Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). All fluorogenic substrates (MCA substrates) were obtained from Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan). L-3-carboxy-trans-2, 3-epoxy-propionyl-L-leucine-4-guanidinobutylamide (E-64) was from Amresco (Solon, OH, USA). Pepstatin A was from Roche (Mannhem, Germany). Protein marker for sodium dodecyl sulfate-poly-acrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was a product of Fermentas (Lithuania). OPA and Zorbax Eclipse-AAA chromatographic column were products of Agilent Technologies (SCC, CA, USA). Methanol, acetonitrile for HPLC was of chromatographical pure, and other reagents were of analytical grade.

2.1.2 AbaloneAbalones (Haliotis discus hannai) with body weight of 75.5 g ± 9.1 g were bought alive from a seafood market in Xiamen from October, 2020 to January, 2021. The abalones were eviscerated, washed, and their muscle was collected for immediate experiment.

2.2 Methods 2.2.1 Cold storage of abalone muscleAfter washing, abalone muscle was sealed into individual bags, stored at a cold room (5 m × 3 m × 2.3 m) with temperature of 4℃ ± 0.5℃. Abalone samples were divided into eight groups, each group consisted of three abalones. Sampling was performed at regular intervals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 d) after cold storage.

2.2.2 FAAs analysis of abalone muscleFree amino acid was measured based on the method by Zhang et al. (2019) with some modifications. Minced abalone muscle was taken and 7.5 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added. The tissue was mashed and centrifuged at 12000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered through 0.22 μm membrane and transferred into sample bottle with pipette gun. Identification and quantification were carried out using a High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) instrument Agilent 1260 G1311C equipped with a VWD detector from Agilent Technologies Inc. O-Phthalic dicarboxaldehyde (OPA) was used as precolumn derivative agent, and the derivatized amino acids were analyzed in a Zorbax Eclipse-AAA chromatographic column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 150 mm, Agilent Technologies Inc.). Column temperature was 40℃, and detection wavelength was 338 nm.

2.2.3 Purification of APThe AP was purified according to the method of Wu et al. (2008) and Zhou et al. (2009) with some modifications. All the operation process were controlled at 4℃. About 160 g minced abalone muscle were homogenized in 4-fold (m/v) buffer A by a homogenizer (Kinematica, PT-2100, Switzerland), and centrifuged at 12000×g for 20 min. The supernatant was separated with 60% – 90% ammonium sulfate. The buffer solution was used for dialysis overnight and centrifuged with 12000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was applied to DEAE-Sepharose anion exchange column (2.5 cm × 10 cm). Active fractions were pooled and concentrated to 7 mL using a membrane with molecular weigh cutoff size of 50 kDa and then applied to a Sephacryl S-300 gel filtration column (2.5 cm × 98 cm). Active fractions were mixed, and ammonium sulfate was added to a final concentration of 0.8 mol L−1 followed by loading on Phenyl-Sepharose column (5 mL). Enzymatic active fractions were pooled and used for SDS-PAGE and enzymatic characterization.

2.2.4 Assay of AP activityAP activity was measured according to the method of Zhang et al. (2013) with some modifications. The reaction system including 50 µL enzyme, 900 µL of 20 mmol L−1 Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1 mmol L−1 DTT (buffer A) and 50 µL of 10 µmol L−1 substrate. The reaction was operated at 30℃ for 10 min.

2.2.5 Determination of protein concentrationProtein concentration was determined according to the method of Lowry et al. (2008). The absorbance was measured at 280 nm with a UV spectrophotometer.

2.2.6 SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)SDS-PAGE was performed under reduction conditions by 10% gel as described by Laemmli (1970). After electrophoresis, Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (CBB) was used for gel staining.

2.2.7 MALDI-TOF/TOF–MS/MS analysisThe purified protein was run on SDS-PAGE and stained with silver nitrate as described by Zhang et al. (2013). The target band was analyzed using 4800 plus MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS/MS analyzer (ABI, USA) by Shanghai Zhongke New Life Biotechnology Company Ltd. The results were further analyzed according to NCBI database.

2.2.8 Effect of temperature and pH on AP activityThe effect of temperature and pH was measured according to the method of Oszywa et al. (2013) with some modifications. The temperature was in the range of 15 – 60℃, while the pH was in the range of 4.0 – 10.0. The remaining activity was determined by the method as described above. All analyses were performed in triplicate and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

2.2.9 Effects of protease inhibitors and metal ionsThe effect of protease inhibitors and metal ions on aminopeptidase was measured according to the method of Li et al. (2015) with some modifications. Protease inhibitors including bestatin, 1, 10-phenanthroline, EDTA, EGTA, PMSF, E-64 and pepstatin A. They were used to study their effects on aminopeptidase. To identify the effect of metal ions on the aminopeptidase, different metal ions, including Mn2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Ca2+, Cu2+, and Fe2+, were mixed with enzyme solution independently and preincubated at room temperature for 30 min. The remaining activity of AP was determined by the method as described above. All analyses were carried out in triplicate, and the results were shown as average values ± standard deviation.

2.2.10 Substrate specificityVarious synthetic fluorogenic substrates, including Arg-MCA, Lys-MCA, Leu-MCA, Met-MCA, Phe-MCA, Ala-MCA, Boc-Phe-Ser-Arg-MCA, Boc-Leu-Arg-Arg-MCA, Boc-Glu-Lys-Lys-MCA, Suc-Gly-Pro-MCA were used to determine substrate specificity of the purified enzyme using the method described by Zhang et al. (2013).

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 Changes of Cathepsin L and Serine Proteinase Activity During Cold StorageDuring the cold storage, abalone, the action of endogenous proteinases in abalones play critical roles for breakdown of structural proteins. Cathepsin L (CL) primarily degrades myofibrillar proteins, while serine protease (SP) degrades both myofibrillar and connective tissue proteins (Zhong et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2020).

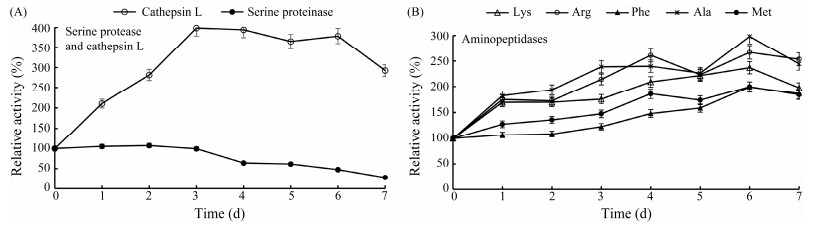

As shown in Fig. 1, cathepsin L activity increased significantly and reached 398% after 3 d, and the activity subsequently plateaued till the 6th day, then dropped. However, the activity of SP kept steady for the initial 3 d, decreased to 50% at the 4th day while retained a mere 20% at day 7. Quite possibly, the reduction of abalone muscle structural parameters during cold storage was ascribed to the degradation of muscular proteins by endogenous proteinases. Matrix metalloproteinases are responsible for the degradation of collagens (Xu et al., 2015), while cathepsin L and serine proteinase are active in myofibrillar protein decomposition (Liu et al., 2020). Aminopeptidase activity to five substrates, especially Phe-MCA and Ala-MCA, are closely relative to taste determined. The activity of AP gradually increased during the 7-day cold storage (Fig. 1B), strongly suggesting its contribution to FAAs accumulation.

|

Fig. 1 Protease activity (A) and aminopeptidase activity (B) in abalone muscle at different time intervals during the storage at 4℃. |

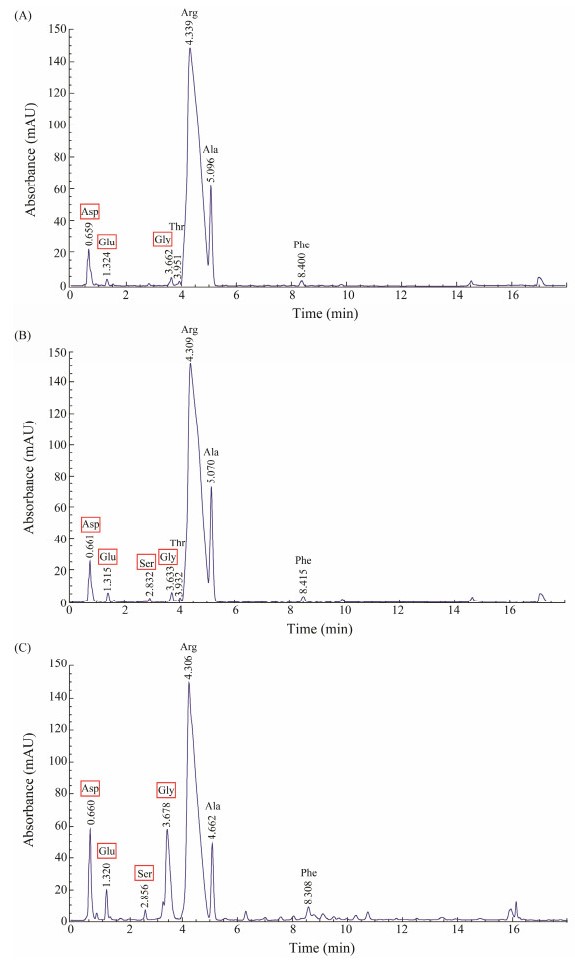

The variation of FAAs contents in abalone muscle during the cold storage process was shown in Fig. 2. When the abalones were fresh, the content of Arg was the highest (Fig. 2A). After cold storage for 1 d, the concentration of FAAs in abalone muscle increased slightly (Fig. 2B). The variety of FAAs increased significantly after 2 d, revealing a highest accumulation rate of Gly from 0 to 2 d (Fig. 2C).

|

Fig. 2 Variation of FAAs contents in abalone muscle during cold storage. A, 0 h; B, 24 h; C, 48 h. |

Quantification of FAAs at different time intervals were shown in Table 1. Compared with fresh abalone, the contents of Asp, Glu, and Ser in 2 d increased by 1.7-fold, 2.0-fold, and 3.0-fold, respectively. Asp and Glu contribute to umami taste while Ser, Gly, Thr and Ala contribute to sweet taste (Zhang et al., 2019). Significant increase (8.4-fold) in the content of Gly is most noticeable. Arg is relevant to an overall pleasant taste rather than bitterness (Chen et al., 2012). Though its content decreased from 12.48 mg (100 g)−1 on 0 d to 9.06 mg (100 g)−1 after 48 h, Arg is still the highest FAA. It was reported that FAAs could facilitate flavor directly and indirectly, the latter is a synergistic effect with other taste-active compounds, such as glycogen and AMP, IMP (Zhang et al., 2019). Moreover, FAAs could contribute as precursors of volatile flavor compounds, thus the increase of FAAs during cold storage directly enhances the delicious taste of abalone.

|

|

Table 1 Quantification of several taste-active FAAs at different time intervals during cold storage |

Accumulation of FAAs is the result of the catalysis of enzymes on proteins and peptides. During postmortem storage of meat, proteins were degraded by various endogenous proteases, causing the increment of peptides and FAAs. Serine proteinase (SP), cathepsin B, cathepsin L (CL) and calpain degraded myofibrillar proteins, tenderizing muscle, whereas aminopeptidase are involved in degrading peptides into smaller peptides and FAAs, which contributes significantly to flavor improvement (Nishimura, 1998; Xiong et al., 2019).

Increment of enzymatic activity is generally in positive relationship with the accumulation of FAAs. The cooperative effect of serine proteinase, cathepsin L and AP can directly contribute to the formation of flavor such as sweet, sour or bitter tastes, or indirectly act as precursors to volatile flavor compounds (Zhao et al., 2005; Li et al., 2015). The accumulation of FAAs, however, will produce a feedback inhibition on the activity of aminopeptidases to some degree (Flores et al., 1998).

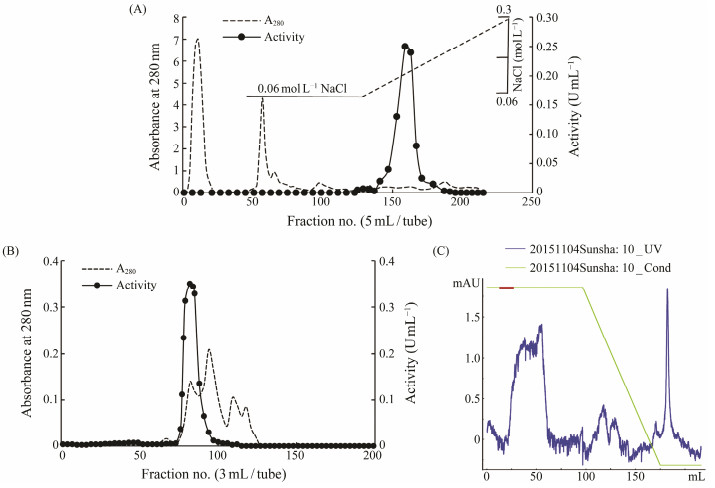

3.3 Purification of APIn the present study, an AP with wide substrate specificity was purified from abalone muscle through ammonium sulfate fractionation together with a series of column chromatographies (Fig. 3). During the whole purification process, the specific activity increased 402 folds with recovery of 11.45%. Approximately 0.7 mg purified AP was obtained from 160 g abalone muscle. The purified enzyme exhibited a single band of 100 kDa on SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, indicating a high degree of purification (Fig. 4A). The molecular mass of the AP from abalone was higher than APs from barley (58 kD) (Mane, 2011), bovine (60 kDa) (Asano, 2010), chicken (66 kDa) (Oszywa et al., 2013), yet smaller than those from human intestine (250 kDa) (Tykvart et al., 2015), and soybean cotyledons (56 – 510 kDa) (Ye and Ng, 2011) as these enzymes are polymerized in tissues, and similar to those from aquatic organisms, such as Litopenaeus vannamei, Pagrus major and Ctenopharyngodon idellus (Wu et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2013). All these results indicated that the molecular masses and structures of APs are different in different species.

|

Fig. 3 Chromatograms of the crude aminopeptidase from abalone muscle after purified with (A), DEAE-Sepharose; (B), Sephacryl S-300; (C), Phenyl-Sepharose. Fractions under the bar were pooled. |

|

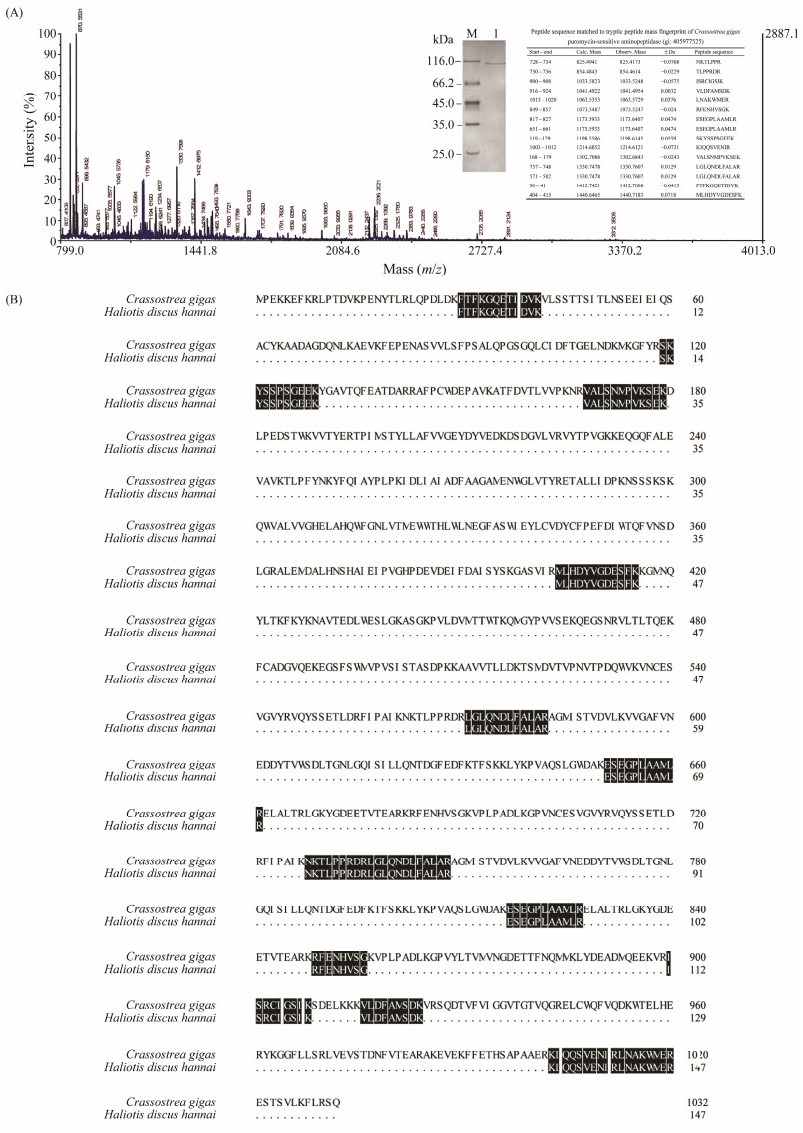

Fig. 4 Peptide mass fingerprinting of the purified enzyme. (A) The map of mass spectrometry (MS). The sequences of fifteen peptide fragments are shown in corresponding peaks. (B) Alignment of tryptic peptide fragments of the purified enzyme with puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase of Crassostrea gigas (gi|405977525). |

The purified enzyme was further identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) result of the purified enzyme was shown in Fig. 4A. Large quantity of peptide fragments were detected in the m/z range of 800 – 4000 Da, and were searched in the NCBI-Mollusk protein sequence database. Thirteen peptide fragments with a total of 147 amino acid residues were obtained and revealed 100% (147/147) identity to puromycin-sensitive AP from Crassostrea gigas (EKC41968.1), verifying that the purified enzyme is an AP (Fig. 4B).

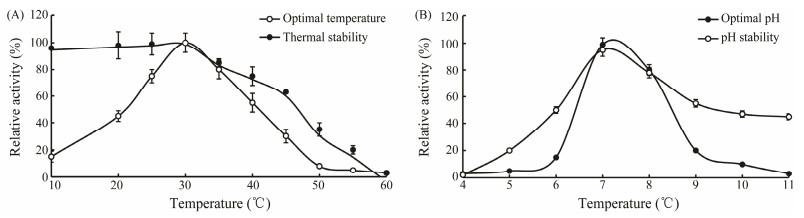

3.5 Effects of pH and Temperature on AP ActivityAs shown in Fig. 5A, the purified enzyme showed its optimum temperature of 30℃, which was in accordance with APs from aquatic organisms while lower than those from bovine (55℃) (Ye and Ng, 2011), chicken (45℃) (Mane et al., 2011). The AP from abalone is not thermal stable. When incubated at 40℃ for 30 min, the enzyme retained 80% of its initial activity, while only 10% initial activity retained if the AP was treated at 50℃. Such a weak tolerance to thermal condition might be elucidated by analyzing its structure. Generally, disulfide bonds within proteins and stronger hydrophobic interactions enhance their stability (Klomklao et al., 2009). The optimal pH of the enzyme was 7.5 and it was active in the limited pH range from 6.5 to 8.0 (Fig. 5B). The pH of activity measure during purification was 8.0, which was consistent with the optimal pH. The pH stability analyses showed a moderate loss of activity after incubation above pH 7.0, while a rapid activity reduction was observed after incubation under pH 6.0. These data indicated that the enzyme remain active at neutral or slightly alkaline pH condition. Among aminopeptidases, leucine aminopeptidase (LAP) exists the most widely. Though LAPs from different resources demonstrate diverse sensitivities to temperature, they are quite similar in pH sensitivity. LAPs are generally active under alkaline environment and inactive under acidic condition.

|

Fig. 5 Enzymatic properties of the purified enzyme. (A) Optimal temperature and thermal stability; (B) Optimum pH and pH stability. |

Kale et al. (2010) studied the structure-function relationships of LAP using X-ray crystallography. They found that the active site of LAP was in great disorder and two metal ions Zn2+ and Mn2+, which were essential for maintaining the region active, were absent under acidic condition (pH 5.2). This is probably due to complete protonation of one of the metal-interacting residues, explaining the inactivity of LAP at low pH.

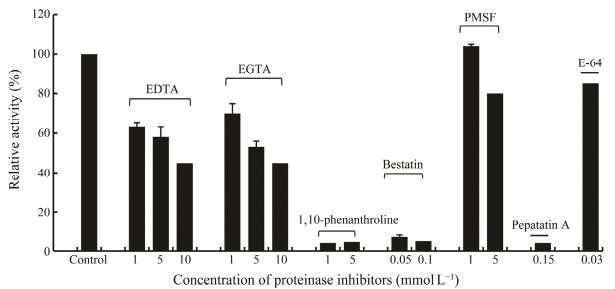

3.6 Effect of Protease Inhibitors on the Activity of Purified APVarious proteinase inhibitors were used to investigate the properties of the purified AP. As shown in Fig. 6, bestatin, a specific inhibitor of aminopeptidase, intensively inhibited the enzymatic activity at a concentration as low as 0.05 mmol L−1. Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1, 10-phenanthroline, suppressed the enzyme activity by 95% and EDTA inhibited 40% activity at 1 mmol L−1. EGTA, a Ca2+ selectively chelating agent, showed less inhibitory effect (30% inhibition) at 1 mmol L−1, and the inhibitory effect increased with the increase of EGTA concentration. On the contrary, serine proteinase inhibitor PMSF and cysteine proteinase inhibitor E-64 had negligible effects on the enzymatic activity. It was noteworthy that pepstatin A, a specific asparatic proteinase inhibitor, showed 96% inhibition effect at a final concentration of 0.15 mmol L−1. These results showed that the purified AP is an enzyme requiring metal ions for activity.

|

Fig. 6 Inhibitory effect of different proteinase inhibitors on the activity of the purified AP. |

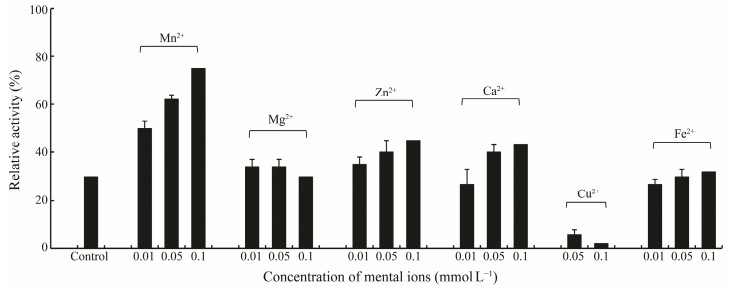

For some metal-dependent aminopeptidases, two metal ions from Zn2+, Co2+, Mn2+, Mg2+ are usually required for them to perform full activity. In several cases, only a single metal ion is indispensable for catalysis while the second metal ion has an uncertain effect in general on modulating activity (Lowther and Matthews, 2002). To analyze the effect of metal ions on AP activity, the purified enzyme was completely dialyzed against buffer A containing 1 mmol L−1 EDTA. It was shown that about 70% of the activity was lost after dialysis. However, approximately 60% of its initial activity could be recovered by 0.05 mmol L−1 Mn2+ and up to 75% at 0.1 mmol L−1 (Fig. 7). Zn2+ also had positive effect on restoring enzyme activity, but recovery rate was lower than that of Mn2+. We also found that Mg2+ and Fe2+ had negligible recovery effect, while Cu2+ showed a strong inhibitory effect. Our present data thus demonstrated that Mn2+ and Zn2+ are crucial to maintain the structure of the active site of AP from abalone. Recovery effect by Mn2+ and Zn2+ was also observed in AP from Litopenaeus vannamei (Zhang et al., 2013). Requirement of metal ions for AP to retain activity was solidly confirmed by its crystal structure (Nguyen et al., 2014). Mn2+ and Zn2+ in the active center were observed in APs isolated from mammal and Pseudomonas putida (Chen et al., 2012; Nguyen et al., 2014). Furthermore, the amino acid residues His, Asp, Glu, and Met that bind to metal ions were highly conserved (Kale et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012). Therefore, the inhibition effect of pepstatin A on AP might be explained as its association with Asp residue existed in the active center. However, Mn2+ and Zn2+ are not indispensable for all APs. Co2+ dependent M18 AP was identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Nguyen et al., 2014). Mg2+ binding at the activity site is involved in the reaction mechanism associated with endonuclease function of APE1 (Oezguen et al., 2011). The activity of glutamyl aminopeptidase is stimulated by Ca2+ (Glenner et al., 1962), suggesting the diverse demands of APs for metal ions.

|

Fig. 7 Rescuing effect of metal ions on the activity of the purified AP. |

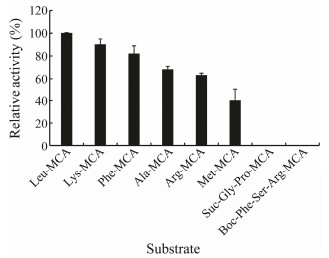

Several fluorogenic substrates were detected and the results were shown in Fig. 8. Among the tested substrates, AP cleaved Leu-MCA most effectively, followed by Lys-MCA and Phe-MCA. It hydrolyzed taste-active amino acid residues such as Ala and Arg with hydrolysis rates of 69% and 60%, respectively. However, the enzyme did not display any endopeptidase activity towards N-terminal-block ed substrates including Boc-Phe-Ser-Arg-MCA and Suc-Gly-Pro-MCA, confirming that it is an exopeptidase with a broad specificity. Similar substrate specificity was reported in LAPs from bovine lens (Taylor, 1993) and red sea bream (Pagrus major) skeletal muscle (Wu et al., 2008).

|

Fig. 8 Substrate specificity of the purified enzyme. |

Structural basis for substrate preferences of LAP was elucidated by X-ray crystallography, and the result revealed that combination of enzyme and substrate needs to meet the steric configuration and matching of charge and polarity (Chen et al., 2012; Nguyen et al., 2014). LAP prefers to hydrolyze substrates with S-configuration at their chiral Cα atom such as leucine and phenylalanine, allowing their α-amino and carbonyl groups to form metal-ligand bonds, while their Cα side chains fit tightly into hydrophobic S1 pockets (Kale et al., 2010). Although the physiological functions of aminopeptidases in abalone muscle have not been elucidated, their contributions to free amino acids increment during cold storage is noteworthy. Thus, further study on the relationship between aminopeptidase structure and the physiological functions in abalone muscle is necessary.

4 ConclusionsDuring cold storage of abalone muscle, the contents of FAAs, including Asp, Glu, Ser, and Gly, increased by 1.7-fold, 2.0-fold, 3.0-fold, and 8.4-fold in 48 h, respectively. The enzyme activity of cathepsin L increased nearly 4 folds and remained stable till the end of 7-day experiment. Aminopeptidase activity increased up to 170% of its initial one at the end of the cold storage process. A leucine amino-peptidase (LAP) with broad substrate specificity was purified from abalone muscle and it contributes to the accumulation of FAAs. Our present work elucidated a significant role of AP in FAAs production in abalone muscle during cold storage.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2018YFD0901004), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31772049).

Asano, M., Nakamura, N., and Kawai, M., 2014. Purification and characterization of an N-terminal acidic amino acid-specific aminopeptidase from soybean cotyledons (Glycine max). Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 74(1): 113-118. (  0) 0) |

Azarnia, S., Lee, B., St-Gelais, D., Kilcawley, K., and Noroozi, E., 2011. Effect of free and encapsulated recombinant aminopeptidase on proteolytic indices and sensory characteristics of cheddar cheese. LWT – Food Science and Technology, 44(2): 570-575. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2010.08.022 (  0) 0) |

Brown, M. R., Sikes, A. L., Elliott, N. G., and Tume, R. K., 2009. Physicochem factors of abalone quality: A review. Journal of Shellfish Research, 27(4): 835-842. (  0) 0) |

Chen, D. W., and Zhang, M., 2007. Non-volatile taste active compounds in the meat of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Food Chemistry, 104(3): 1200-1205. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.042 (  0) 0) |

Chen, Y., Farquhar, E. R., Chance, M. R., Palczewski, K., and Kiser, P. D., 2012. Insights into substrate specificity and metal activation of mammalian tetrahedral aspartyl aminopeptidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287(16): 13356-13370. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M112.347518 (  0) 0) |

Chiou, T. K., and Lai, M. M., 2002. Comparison of taste components in cooked meats of small abalone fed different diets. Fisheries Science, 68(2): 388-394. DOI:10.1046/j.1444-2906.2002.00437.x (  0) 0) |

Damle, M., Harikumar, P., and Jamdar, S., 2010. Debittering of protein hydrolysates using immobilized chicken intestinal mucosa. Process Biochemistry, 45(7): 1030-1035. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2010.03.016 (  0) 0) |

Flores, M., Aristoy, M., and Toldra, F., 1998. Feedback inhibition of porcine muscle alanyl and arginyl aminopeptidases in cured meat products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 46(12): 4982-4986. DOI:10.1021/jf9806863 (  0) 0) |

Glenner, G. G., McMillan, P. J., and Folk, J. E., 1962. A mammalian peptidase specific for the hydrolysis of N-terminal α-L-glutamyl and aspartyl residues. Nature, 194(4831): 867. (  0) 0) |

Kale, A., Pijning, T., Sonke, T., Dijkstra, B. W., and Thunnissen, A. M., 2010. Crystal structure of the leucine aminopeptidase from Pseudomonas putida reveals the mol. basis for its enantioselectivity and broad substrate specificity. Journal of Molecular Biology, 398(5): 703-714. DOI:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.042 (  0) 0) |

Klomklao, S., Kishimura, H., Nonami, Y., and Benjakul, S., 2009. Biochemistry properties of two isoforms of trypsin purified from the intestine of skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis). Food Chemistry, 115(1): 155-162. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.11.087 (  0) 0) |

Laemmli, U. K., 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227(15): 680-685. (  0) 0) |

Li, S. W., Lin, L. P., Chen, S. H., Fu, M. Y., and Wu, G. P., 2015. Purification and biochemical characterization of a puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase from black carp muscle. Process Biochemistry, 50(7): 1061-1067. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2015.04.002 (  0) 0) |

Liu, B., Liu, Z. Q., Li, D. Y., Yu, M. M., Liu, Y. X., Qin, L., et al., 2020. Action of endogenous protease on texture deterioration of the bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) adductor muscle during cold storage and its mechanism. Food Chemistry, 323: 126790. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126790 (  0) 0) |

Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Fan, A. L., and Randall, R. J., 1951. Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 193: 256-275. (  0) 0) |

Lowther, W., and Matthews, B., 2002. Metalloaminopeptidases: Common functional themes in disparate structural surroundings. Chemistry Reviews, 102: 4581-4607. DOI:10.1021/cr0101757 (  0) 0) |

Mane, S., Gade, W., and Jamdar, S., 2011. Purification and characterization of proline aminopeptidase from chicken intestine. Process Biochemistry, 46(6): 1384-1389. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2011.03.006 (  0) 0) |

Nguyen, D. D., Pandian, R., Kim, D., Ha, S. C., Yoon, H. J., Kim, K. S., et al., 2014. Structural and kinetic bases for the metal preference of the M18 aminopeptidase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 447(1): 101-107. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.109 (  0) 0) |

Nishimura, T., 1998. Mechanism involved in the improvement of meat taste during postmortem aging. Food Science and Technology International Tokyo, 4(4): 241-249. DOI:10.3136/fsti9596t9798.4.241 (  0) 0) |

Oezguen, N., Mantha, A. K., Izumi, T., and Schein, C. H., 2011. MD simulation and experimental evidence for Mg2+ binding at the b site in human AP endonuclease 1. Bioinformation, 7(4): 184-198. DOI:10.6026/97320630007184 (  0) 0) |

Oszywa, B., Makowski, M., and Pawełczak, M., 2013. Purification and partial characterization of aminopeptidase from barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) seeds. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 65C(6): 75-80. (  0) 0) |

Taylor, A., 1993. Aminopeptidases: Structure and function. The FASEB Journal, 7(2): 290-298. DOI:10.1096/fasebj.7.2.8440407 (  0) 0) |

Tjáderhane, L., Nascimento, F. D., Breschi, L., Mazzoni, A., Tersariol Ivarne, L. S., Geraldeli, S., et al., 2013. Optimizing dentin bond durability: Control of collagen degradation by matrix metalloproteinases and cysteine Cathepsins. Dental Materials, 29(1): 116-135. DOI:10.1016/j.dental.2012.08.004 (  0) 0) |

Toldrá, F., Aristoy, M. C., and Flores, M., 2000. Contribution of muscle aminopeptidases to flavor development in dry-cured ham. Food Research International, 33: 181-185. DOI:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00032-6 (  0) 0) |

Tykvart, J., Bařinka, C., Svoboda, M., Navrátil, V., Souček, R., Hubálek, M., et al., 2015. Structural and biochemistry characterization of a novel aminopeptidase from human intestine. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290(18): 11321-11336. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M114.628149 (  0) 0) |

Wang, D., and Wu, F. X., 2021. China Fishery Statistical Year-book. China Agriculture Press, Beijing: 21-27. (  0) 0) |

Wu, G. P., Cao, M. J., Chen, Y., Liu, B. X., and Su, W. J., 2008. Leucine aminopeptidase from red sea bream (Pagrus major) skeletal muscle: Purification, characterization, cellular location, and tissue distribution. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 56(20): 9653-9660. DOI:10.1021/jf801477r (  0) 0) |

Xiong, X., He, B. Y., Jiang, D., Dong, X. F., and Qi, H., 2019. Postmortem biochemistry and textural changes in the Patinopecten yessoensis adductor muscle (PYAM) during iced storage. International Journal of Food Properties, 22(1): 1024-1034. DOI:10.1080/10942912.2019.1625367 (  0) 0) |

Xu, C., Wang, C., Cai, Q. F., Zhang, Q., Weng, L., Liu, G. M., et al., 2015. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) plays a critical role in the softening of common carp muscle during chilled storage by degradation of type Ⅰ and Ⅴ collagens. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 63(51): 10948-10956. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03893 (  0) 0) |

Ye, X. J., and Ng, T. B., 2011. Purification and characterisation of an alanine aminopeptidase from bovine skeletal muscle. Food Chemistry, 124(2): 634-639. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.06.087 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, L., Cai, Q. F., Wu, G. P., Shen, J. D., Liu, G. M., Su, W. J., et al., 2013. Arginine aminopeptidase from white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) muscle: Purification and characterization. Europe Food Research Technology, 236(5): 759-769. DOI:10.1007/s00217-013-1941-x (  0) 0) |

Zhang, N. L., Wang, W. L., and Li, B., 2019. Non-volatile taste active compounds and umami evaluation in two aquacultured pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus and Takifugu rubripes). Food BioScience, 32: 100468. DOI:10.1016/j.fbio.2019.100468 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, G. M., Zhou, G. H., and Tian, W., 2005. Changes of alanyl aminopeptidase activity and free amino acid contents in biceps femoris during processing of Jinhua ham. Meat Science, 71: 612-619. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.05.006 (  0) 0) |

Zhong, C., Cai, Q. F., Liu, G. M., Sun, L. C., Hara, K., Su, W. J., et al., 2012. Purification and characterisation of cathepsin L from the skeletal muscle of blue scad (Decapterus maruadsi) and comparison of its role with myofibril-bound serine proteinase in the degradation of myofibrillar proteins. Food Chemistry, 133(4): 1560-1568. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.02.050 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, L. G., Liu, B. X., Sun, L. C., Hara, K., Su, W. J., and Cao, M. J., 2009. Identification of an aminopeptidase from the skeletal muscle of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 36(4): 953-962. (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22