2) Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Environmental Science, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266237, China;

3) University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

4) Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

Tintinnid ciliates are single-celled protozoa belonging to the subclass Choreotrichia and the class Spirotrichea (Lynn, 2008). They are important components of microzooplankon, and they feed on picoplankton and nanoplankton (Dolan et al., 2006). Although tintinnids represent a relatively small proportion of microzooplankton compare to aloricate ciliates (Dolan et al., 1999), they bloom occasionally, and certain species can dominate the planktonic ciliate community (e.g., Wickham et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2018).

The lorica oral diameter (LOD) is an important morphological characteristic used to identify tintinnid species, and its diversity is tightly related to taxonomic diversity (Dolan et al., 2006). The LOD of a species determines the size of food particles it can ingest, and its preferred prey size is approximately 25% of its LOD (Dolan, 2010). The LOD size varies considerably with tintinnid species, but different species can also have the same size LOD. Although several previous studies have focused on the LOD of tintinnids (e.g., Dolan et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2018), no previous studies have investigated the spatial variation in tintinnids' LOD from the Antarctic zone (AZ) near continent to the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC).

The Amundsen Sea lies within the Southern Ocean near Marie Byrd Land in West Antarctica. It is a dynamic region associated with rapid changes in the outlet glaciers (e.g., Shepherd et al., 2004; Thoma et al., 2008) and the highest production of Antarctic waters (Yager et al., 2012). Warm circumpolar deep water (CDW) intrudes close to the continental shelf in the Amundsen Sea (e.g., Jacobs et al., 1996; Moffat et al., 2009; Martinson and McKee, 2012; Walker et al., 2013). However, compare to other regions in the Southern Ocean, the Amundsen Sea has rarely been sampled, although the distribution of tintinnids has been studied in recent years (e.g., Wickham et al., 2011; Dolan et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2014, 2016a, 2016b).

Evidence shows that there are 161 widespread species (which are also found in north of 40°S) and 32 Southern Ocean endemic species (which are only found in south of 40°S) in Antarctic waters (Dolan et al., 2012). The vast area south of 40°S is hydrologically divided by PF into the Subantarctic Zone (SAZ) in the north and the AZ in the south (e.g., Whitworth, 1980; Pollard et al., 2002). Most tintinnid studies conducted in Antarctic waters have focused on the AZ (south of the PF) (e.g., Wickham et al., 2011; Dolan et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2014, 2016a, 2016b; Liang et al., 2018). However, the distribution characteristics of tintinnids from the AZ northwards to the PF have been rarely studied, and although some studies with large latitudinal ranges have been conducted near the Antarctic Peninsula or ice edge in the Weddell Sea (e.g., Boltovskoy et al., 1989; Alder and Boltovskoy, 1991a, 1991b; Boltovskoy and Alder, 1992), the PF has not been considered. In addition, some tintinnid species have been found to occur only in the SAZ or AZ, according to investigations of some transects from the Antarctic Peninsula to the Argentinian coast in the Atlantic section of the Southern Ocean (e.g., Thompson et al., 2001; Thompson, 2004; Thompson and Alder, 2005).

The mixing of species from the AZ and SAZ in the PF has not yet been studied. The PF zone has southern and northern boundaries. The southern boundary lies on the northern side of the AZ, and the minimum temperature layer of seawater descends northward as the temperature slowly increases (Orsi et al., 1995). In the northern PF boundary, the minimum temperature layer reaches 2℃ at a depth of 200 m (Sokolov and Rintoul, 2009). Liang et al. (2018) determined that the stratified sandwich structure in the AZ extends northward in austral summer until it meets the PF, where the water column become vertically well mixed. However, it has not yet been clarified how the tintinnid species in the different water masses extrude into the PF.

The aim of this study was to investigate tintinnid assemblages along a transect covering the SAZ, PF, and AZ to determine: 1) the distribution characteristics of tintinnid species in relation to the PF; 2) any differences between species and Antarctic and subantarctic assemblages.

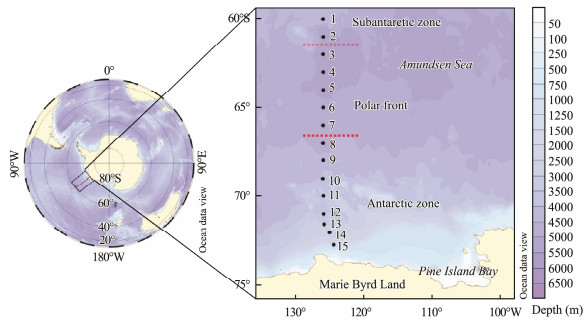

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Study AreaTintinnids were sampled at 15 stations along a meridional transect at approximately 126°W in open waters without sea ice in the Amundsen Sea (60°S–72°46'S) (Fig. 1) onboard the R/V Xuelong in early austral autumn (March 2–10, 2018). The minimum and maximum depths of sampling stations were 443 m at St.15 and 4850 m at St.6, respectively. Vertical profiles of temperature, salinity, and in vivo chlorophyll a (Chl a) fluorescence were obtained using the SBE911-conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) unit at each station from the sea surface to a depth of 200 m.

|

Fig. 1 Sampling stations in open water within Amundsen Sea (western Antarctica) during early austral autumn (March 2–10, 2018). The map was produced using ocean data view (Schlitzer, 2003); red dashed-lines indicate polar front boundaries. |

Water was sampled using 10-L Niskin bottles on a rosette CTD carrousel. Seawater samples of 1 L were collected from each sampling point (surface, 50, 100, 200 m at each station) and fixed with Lugol's solution (1% final concentration). A total of 60 samples were collected.

In the laboratory, each water sample was concentrated to approximately 100 mL by gently siphoning out the supernatant water after settling for at least 48 h. The settling and siphoning processes were repeated to concentrate each sample to a final volume of 25 mL. The concentrated sample was then settled in an Utermöhl counting chamber for at least 24 h. Tintinnids in the counting chambers were examined using an Olympus IX 71 inverted microscope (100× or 400×).

The entire concentrated sample was counted. If the microscopic view was blurred because of high phytoplankton concentrations, the 25-mL final volume was divided into at least two smaller parts and examined separately. As mechanical and chemical disturbances associated with collection and fixation procedures can provoke detachment of the protoplasma from the loricae (Paranjape and Gold, 1982; Alder, 1999), empty loricae of tintinnid species were enumerated in this study. It is acknowledged that as some loricae may be empty when sampled (Kato and Taniguchi, 1993; Dolan and Yang, 2017), the results in our study could be overestimated.

Each tintinnid species was identified according to lorica morphology and size using information from previous studies (Laackmann, 1910; Kofoid and Campbell, 1929, 1939; Hada, 1970; Boltovoskoy et al., 1990; Alder, 1999; Zhang et al., 2012; Dolan et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2018), and for each tintinnid species, the lorica size (particularly the length and oral diameter) of at least 20 individuals were measured (when possible). Southern Ocean endemic species were defined according to Dolan et al. (2012).

2.3 Data AnalysisData obtained at each station were pooled, and water column average abundances were calculated using total abundances divided by the total original water sample volumes. The occurrence frequency of each tintinnid species was calculated by dividing the total number of sampling points by the number of sampling points at which the species occurred.

Principle Components Analysis (PCA) was conducted using Canoco for Windows 4.5 software. For PCA, the environmental variables included seawater temperature, salinity, Chl a, and depth, and the biological variables consisted of tintinnid species abundance.

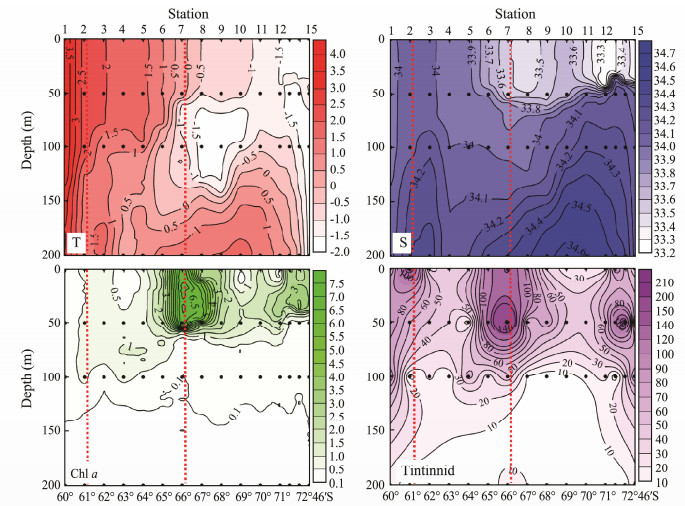

3 Results 3.1 HydrographyTemperature in the transect was found to vary within a range of -1.7 to 3.9℃ (Fig. 2). From St.7 to St.10, the summer surface water (SSW), winter water (WW), and circumpolar deep water (CDW) had a typical sandwich structure; from St.11 to St.15, the upper 50 m was occupied by cold water (< -1℃) on the top of CDW upwelling; and at the coastal side stations of Sts. 14 and 15, cold water occupied the water column down to 200 m. From St.7 to St.10, the temperature at a depth of around 100 m was stable and remains lower than -1℃ without any obvious descent (Fig. 2). From St.7 northward, the temperature minimum slowly increased from about -1℃ to about 1℃ at St.3 (Fig. 2), but the depth of the temperature minimum layer descended from about 75 m to 200 m (Fig. 2). Therefore, St.7 was selected as being the southern boundary of the PF. The minimum temperature layer was 2℃ at 200 m between St.1 and St.2; therefore, St.2 was selected as being representative of the northern PF boundary. The SAZ, PF, and AZ were thus divided (Fig. 1).

|

Fig. 2 Vertical distributions of temperature (T, ℃), salinity (S), in vivo chlorophyll a (Chl a, mg m-3) fluorescence, and tintinnid abundance (ind L-1) along transect in open water within Amundsen Sea. Dots indicate depths, at which tintinnids were sampled; red dashed-lines indicate northern and southern boundaries of polar front. |

Salinity was generally low at the surface but it increased with depth (Fig. 2). A halocline was identified at a depth of 50 m from St.6 to St.15, and salinity was at its lowest above the halocline. The upwelling of CDW at St.6–St.15 was identified by the 0℃ isotherm and 34.2 isohaline (Fig. 2).

The in vivo Chl a concentration decreased with depth and in a range of 0.04–7.03 mg m-3 (Fig. 2). High values (> 2 mg m-3) occurred in the upper 50 m above the halocline from St.6 to St.15, and the highest value was found within the southern boundary of the PF (Fig. 2).

3.2 Tintinnid CompositionIn the upper layers above the CDW, tintinnid abundance was > 20 ind L-1 (Fig. 2). The 30 ind L-1 isoline occurred approximately at the position of the 34.1 isohaline (Fig. 2). At both ends of the transect, where waters were mixed throughout the water column, high tintinnid abundances were distributed deeper in the transect than in the middle part (Fig. 2), and the average tintinnid abundance of the transect was 45.70 ind L-1 (Table 1). There were three regions of high tintinnid abundance (> 50 ind L-1) (Fig. 2). The maximum abundance (211 ind L-1) in the southern boundary of the PF occurred at St.7 at a depth of 50 m (Fig. 2). The maximum abundances in the northern and southern regions were 163 ind L-1 in the northern boundary of the PF and 169 ind L-1 near the Antarctic continent, respectively (Fig. 2).

|

|

Table 1 Distribution of tintinnid species in different assemblages (Fig. 8a) in open waters of Amundsen Sea |

|

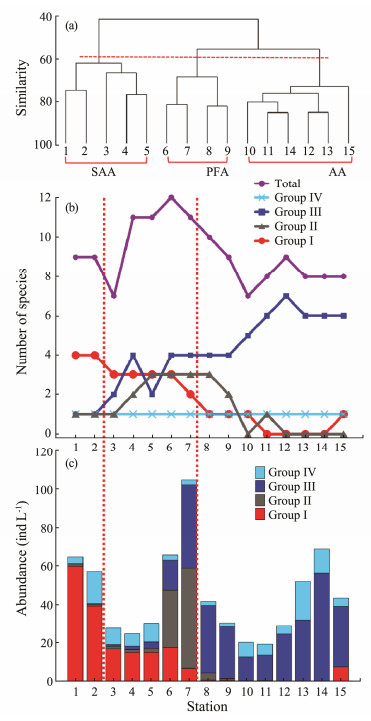

Fig. 8 (a) Cluster analysis of sampling stations using groupaverage linkage based on the Bray-Curtis similarity matrix of fourth root transformed tintinnid abundances. (b) Species richness and (c) abundance of four tintinnid groups along transect in open water in Amundsen Sea. SAA, subantarctic assemblage; PFA, polar frontal assemblage; AA, Antarctic assemblage. |

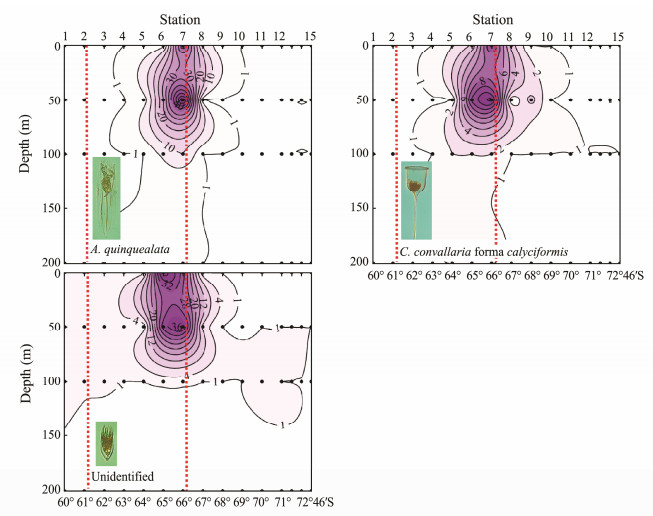

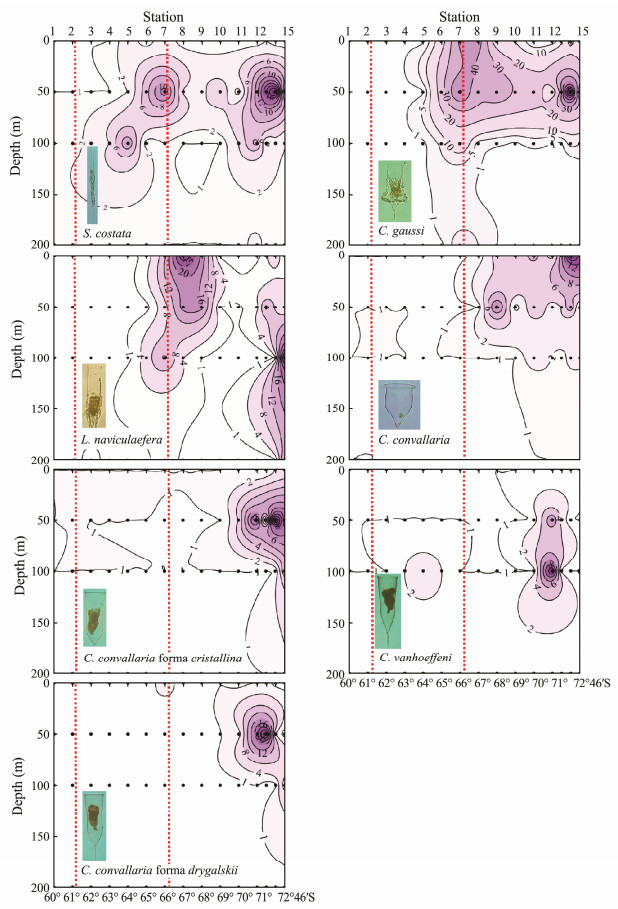

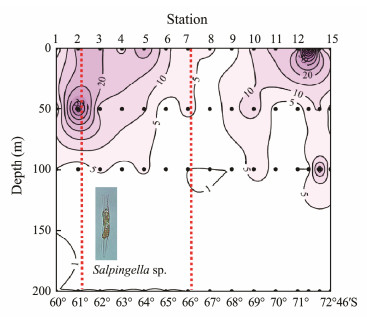

A total of 17 tintinnid species belonging to seven genera were identified, including one unidentified species (Table 1, online resource 1). Nine species were endemic to the Southern Ocean (Amphorellopsis quinquealata, Codonellopsis gaussi, Cymatocylis antarctica, C. convallaria, C. convallaria forma calyciformis, C. convallaria forma cristallina, C. convallaria forma drygalskii, C. vanhoeffeni, and Laackmanniella naviculaefera). The most abundant species was C. gaussi (21.7% of total tintinnid abundance) with a maximum abundance of 107 ind L-1 (Table 1), and the most frequent species was Salpingella sp., which occurred at 70% of sampling points. Amphorides laackmanni and Salpingella acuminata had very low abundances (average abundance and maximum abundance did not exceed 0.3 and 2 ind L-1, respectively, Table 1), they were not assigned a group. The other tintinnid species were divided into four groups according to their horizontal distribution characteristics described below (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6).

|

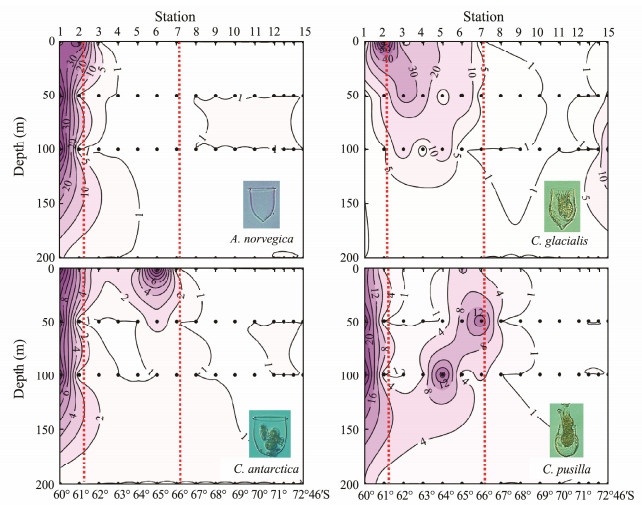

Fig. 3 Vertical distribution of abundance (ind L-1) of tintinnid species (Group Ⅰ) in open waters in Amundsen Sea. Dots indicate depth at which tintinnids were sampled; red dashed-lines indicate northern and southern boundaries of polar front. |

|

Fig. 4 Vertical distribution of abundance (ind L-1) of tintinnid species (Group Ⅱ) in open waters in Amundsen Sea. Dot symbols indicate the depth at which ciliates were sampled. The red dashed lines indicate north and south boundaries of polar front. |

|

Fig. 5 Vertical distribution of abundance (ind L-1) of tintinnid species (Group Ⅲ) in open waters in Amundsen Sea. Dot symbols indicate the depth at which ciliates were sampled. The red dashed lines indicate north and south boundaries of polar front. |

|

Fig. 6 Vertical distribution of abundance (ind L-1) of Salpingella sp. (Group Ⅳ) in open waters in Amundsen Sea. Dot symbols indicate the depth at which ciliates were sampled. The red dashed lines indicate north and south boundaries of polar front. |

Group Ⅰ comprised tintinnid species Acanthostomella norvegica, Codonellopsis glacialis, C. pusilla and C. antarctica, which mainly occurred near the northern boundary of the PF (Fig. 3). These organisms were primarily distributed in the SAZ north of the PF; they were also extruded southward into the PF along the transect but had very low abundances in the AZ. Vertically, the abundance distribution depths of A. norvegica, C. pusilla, and C. antarctica decreased from the SAZ to the PF, and they were limited to the area above the temperature minimum layer in the PF (Figs. 2, 3).

Group Ⅱ comprised tintinnid species A. quinquealata, C. convallaria forma calyciformis, and the unidentified species. These organisms were mainly found in the PF close to its south boundary (Sts.6, 7, 8; Fig. 4) where the cold water began to descend northward (Fig. 2). Vertically, they primarily occurred in the upper 100 m above the temperature minimum layer (Fig. 4).

Group Ⅲ comprised tintinnids Salpingella costata, C. gaussi, C. convallaria, C. convallaria forma cristallina, C. convallaria forma drygalskii, C. vanhoeffeni, and L. naviculaefera. These species primarily occurred in the AZ in the southern part of the transect near the Antarctic continent, and they extruded northward but did not exceed the northern boundary of the PF (Fig. 5). Most of these organisms are endemic to the Southern Ocean. Vertically, S. costata, C. convallaria forma cristallina, C. convallaria forma drygalskii and C. vanhoeffeni were mainly limited to the 50-m layer where the cold water was located (Fig. 5). The northward extension of these three species belonging to Cymatocylis was limited to the position of St.10 (Fig. 5). S. costata extended northward and descended with cold water in the PF; L. naviculaefera occurred in both cold water (a depth of about 50 m) and relatively warm water (surface) at stations north of St.10, but only in cold water at stations south of St.10 (Fig. 5); and C. gaussi and C. convallaria mainly occurred in the upper 50 m but C. gaussi extruded further north than C. convallaria (Fig. 5).

Group Ⅳ comprised Salpingella sp., which was distributed at all stations of the transect; vertically, it mainly occurred in the upper 50 m (Fig. 6).

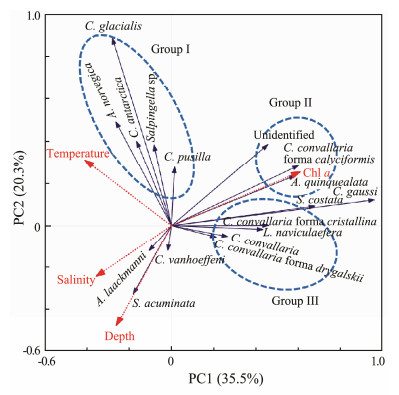

3.3 Relationships Between Tintinnid Species and Environmental FactorsPrinciple component analysis of the 60 samples and 17 tintinnid species was conducted to examine relationships between environmental factors and tintinnid species (Fig. 7). Two principle components discriminated the environmental conditions within three zones of the Amundsen Sea. As shown in Fig. 7, tintinnid species arrows are obviously gathered into three clusters, which correspond to three of the defined distribution groups (Figs. 3, 4, 5). The first two components can explain 55.8% of the tintinnid species variation (35.5% and 20.3%, respectively) and 72.8% of the species-environment correlations (Fig. 7).

|

Fig. 7 Principal component analysis (PCA) of tintinnid ciliate abundance and seawater samples associated with environmental variables. The x-axis is the first PCA axis, and the y-axis is the second PCA axis. Environmental variables and tintinnid species are indicated by red dashed arrows and blue solid arrows, respectively. Pearson correlation coefficients between the PCA axes and the environmental factors are indicated by the length and direction of the arrow. The angle between the arrows give the degree of correlation among the factors, with 0°, 90°, and 180° indicating R = 1, R = 0, and R = -1, respectively. |

The first principle component has a strong positive correlation with Chl a (R = 0.61) but negative correlations with temperature (R = -0.41), salinity (R = -0.36), and depth (R = -0.26, Fig. 7). The second principle component has negative correlations with water depth and salinity (R = -0.48 and -0.24, respectively) but positive correlations with temperature and Chl a (R = 0.31 and 0.25, respectively, Fig. 7). Tintinnid species in Group Ⅰ have positive correlations with temperature (Fig. 7) and mainly inhabit warm waters in the SAZ (Fig. 3). Tintinnid species in Group Ⅱ have strong positive correlations with Chl a but strong negative correlations with salinity and depth; therefore, these species were distributed in areas with a high Chl a concentration and low salinity in the upper waters of the PF (Fig. 4). The adaptation of tintinnid species in Group Ⅲ to environment is similar to that of Group Ⅱ; however, the species in Group Ⅲ are more sensitive to temperature (Fig. 7) and preferentially occur in cold waters in the AZ (Fig. 7).

3.4 Tintinnid AssemblagesCluster analysis was used to divide stations into three groups according to tintinnid abundance (Fig. 8a). Tintinnid species at Sts.1–5, Sts.6–9, and Sts.10–15 were identified as the subantarctic assemblage (SAA), polar frontal assemblage (PFA), and Antarctic assemblage (AA), respectively. Tintinnid species in Group Ⅰ, Group Ⅱ, and Group Ⅲ are the indigenous components of SAA, PFA, and AA, respectively. Tintinnid species richness and abundance were found to vary greatly in different assemblages along latitude. Both species richness and abundance increased from SAA to PFA and then decreased to AA (Fig. 8). Maximum species richness (12 species) and water column average abundance (105 ind L-1) occurred at St.6 and St.7, respectively (Figs. 8b, 8c).

Species richness of Group Ⅰ tintinnids generally decreased from SAA to AA, with a maximum of four species found in the SAZ (Fig. 8b). In contrast, species richness of Group Ⅲ declined from AA to SAA, with a maximum of seven species found at St.12 in the AZ (Fig. 8b). For Group Ⅱ, the peak value (3) of species richness was concentrated at the PFA near the southern boundary of the PF (Fig. 8b).

As with species richness variation, there was a similar trend for the abundances of different tintinnid groups from the SAA to AA. The tintinnid abundance of Group Ⅰ decreased southward along latitude, with the highest abundance (about 60 ind. L-1) found at St.1 (Fig. 8c). In contrast, the tintinnid abundance of Group Ⅲ decreased at first and then increased at the PFA in the middle of the transect in the PF, and then vanished in the northernmost SAZ. There were two high abundance values of 56 and 43 ind. L-1 in St.14 in the SAZ and at St.7 in PF, respectively (Fig. 8c). The tintinnid abundance of Group Ⅱ only occurred around the south boundary of the PF, with the highest value of 52 ind. L-1 at St.7 in the PF (Fig. 8c). The tintinnid abundance of Group Ⅳ was low (< 20 ind L-1) from the SAA to the AA (Fig. 8c).

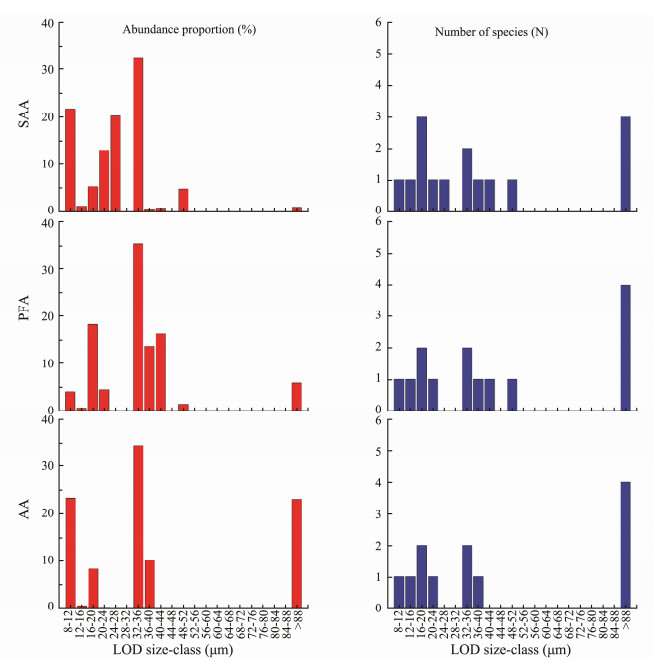

Tintinnid species were divided into 10 LOD size-classes with a step size of 4 μm from 8 to > 88 μm (Fig. 9). Generally, there was one tintinnid species in each LOD sizeclass, except for the classes of 16–20, 32–36, and > 88 μm (Fig. 9). The LOD size-class of > 88 μm had the highest number of species of all three assemblages, and the sizeclass of 32–36 μm had highest abundance proportion (about 35%) of all assemblages (Fig. 9). In addition, the abundance proportion of small LOD size-classes (< 32 μm) decreased from the northern end (SAA) to the southern end (AA) of the transect, while the large LOD size-classes (> 80 μm) increased. The abundance proportion of tintinnids in the < 32 μm LOD size-class was much higher in the SAA (> 60%) than other assemblages (< 33%, Fig. 9). In particular, there was a considerable decrease in the abundance proportion of the 20–24 and 24–28 μm LOD sizeclasses, and they vanished in the AA (Fig. 9). In addition, the abundance proportion of the > 80 μm size-class increased drastically from < 1% in SAA to > 23% in AA (Fig. 9).

|

Fig. 9 Abundance proportion and number of species belonging to different tintinnid LOD (lorica oral diameter) size-classes in different areas of open waters in Amundsen Sea. SAA, subantarctic assemblage; PFA, polar frontal assemblage; AA, Antarctic assemblage. |

This study discovered the occurrence of a new group of tintinnids existing within the PF. Generally, some of the species (Group Ⅱ) occurred only around the southern boundary of the PF and then vanished in other areas. Three indigenous species within the PFA were located between the SAA and the AA; these three species have rarely been recorded in previous studies (Thompson, 2004; Thompson and Alder, 2005; Dolan et al., 2013), and information about their distribution in Antarctic waters is inadequate. In the present study, these species were found to belong to a transitional assemblage inhabiting a limited area near the southern edge of the PF. It is also considered that as the PF surrounds the Antarctic continent, the organisms in Group Ⅱ may thus occur around Antarctica in the PF. We thus speculate that the scarcity of these species recorded in previous studies could be due to the small sampling area ranges employed in previous studies and the relatively small habitat of these organisms. These species, which have seldomly been recorded in the southwestern Atlantic (e.g., Thompson et al., 2001; Thompson, 2004; Thompson and Alder, 2005), are likely restricted to a narrow belt, because Drake Passage between the Antarctic Peninsula and South America is a relatively narrow space.

Only a few records of species such as A. quinquealata and C. convallaria forma calyciformis in the PF have been documented in previous studies in Antarctic waters. According to Dolan et al. (2013) (Table 3 in their paper), these two species occurred at the northern end (about 65°–68°S) of a transect (65°–74°S); therefore, only the southern limit (68°S) was defined. Thompson (2004) found these two species occurring at the southern end (55°–60°S) of a transect (35°–60°S); therefore, only the northern limit (55°S) was defined. Furthermore, C. convallaria forma calyciformis occasional appeared in the AZ south of 57°S in the study of Thompson and Alder (2005). Therefore, the results of our study with respect to the domain of these two species are consistent with those of previous data, and it can be verified that they occur in the middle of the Southern Ocean, especially in the PF.

In our study, Salpingella sp. in Group Ⅳ occurred in all zones. The widespread Salpingella sp. was identified according to the description of Liang et al. (2018), and it was the same as Salpingella sp. #1 in Buck et al. (1992). It has been documented that Salpingella sp. occurs in a limited latitudinal range from 65°S to 66°S of Weddell Sea (Buck et al., 1992) and in open waters near Prydz Bay (65°–67°S) (Liang et al., 2018). However, as this species is very small in size, it may not have been sampled by Thompson and Alder (2005) who used filtration with a 10-μm pore-size net. In the present study, we found that this species was distributed from the AZ to the subantarctic zone (SAZ).

In our study, there was only one transect, and only 1-L of seawater was collected at each sampling point; it is thus possible that some rare tintinnid species were missed.

4.2 Mixing of Tintinnid SpeciesLiang et al. (2018) predicted that Summer Surface Water (SSW) and Winter Water (WW) indigenous species will extend northward until they meet other tintinnid species in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). In the case of C. gaussi in our study, this SSW species met subantarctic species at the southern boundary of the PF (Sts.5, 6, 7). However, the WW indigenous species (e.g., C. convallaria forma drygalskii, C. vanhoeffeni) did not extend far enough northwards (they disappeared before the temperature minimum layer began to descend) to meet any subantarctic species, with the exception of S. costata. Therefore, our results differ slightly from those of Liang et al. (2018). We found that the different species in Groups Ⅰ and Ⅲ had different expansion abilities, and this resembles tintinnids in the East China Sea, where neritic and oceanic tintinnids have been divided into pioneer species and core species according to their different expansion abilities (Li et al., 2016).

Thompson and Alder (2005) used the PF as a line to divide the sampling area into the SAZ and AZ. However, our study provides details of tintinnid species mixing in the PF. In the present study, some species were found to cross the PF boundaries, but their abundances decreased from the PF to their distribution edges; for example, C. pusilla in Group Ⅰ (Fig. 3), and C. gaussi and L. naviculaefera in Group Ⅲ (Fig. 5). It is thus evident that the PF acts as an important boundary that limits tintinnid species in the SAZ and AZ; however, tintinnids in the SAZ and AZ can extend into the PF and mix therein.

4.3 Tintinnid AssemblagesThe study area of the Amundsen Sea is representative of an ecotone, which can be defined as an area of relatively rapid change that produces a narrow ecological zone between two different and relatively homogeneous community types (Attrill and Rundle, 2002). However, ecotones are rarely discussed in biological oceanography, and their boundaries are unclear in the marine environment (Longhurst, 2007; Ribalet et al., 2010). In the present study, tintinnid species in Group Ⅰ and Group Ⅲ correspond to two different assemblage types, and Sts.6–9 represent a transitional area that can be defined as a zone of interaction between neighboring communities (Kent et al., 1997). Therefore, the spatial distribution of tintinnids in Groups Ⅰ, Ⅱ, and Ⅲ match the ecotone theory: the species richness of tintinnids in Groups Ⅰ and Ⅲ decreased in the transitional area of the PF where indigenous species are distinct from the other zones.

The ecotone zone between the SAZ and AZ differs from that between neritic and oceanic assemblages in the continental shelf of the East China Sea, where the absence of endemic front tintinnid species results in low species richness in the transitional area between the oceanic and neritic zones (Li et al., 2016). From the Antarctic to the Arctic, the major tintinnid assemblages have been found to belong to austral, warm water, and boreal. However, no previous studies have examined whether any tintinnid species occur only in transitional zones.

The prey size of tintinnid is related to their LOD (Dolan et al., 2002). Their preferred food particle size is approximately 25% of their LOD, and the maximum tintinnid prey size ingested does not exceed 45% of the LOD (Heinbokel, 1978; Dolan et al., 2002). Tintinnids with a small LOD have higher growth rates than these with a large LOD (Montagnes, 2013). Tintinnid LOD is both a key ecological and taxonomic characteristic (Dolan et al., 2013). However, no previous reports have discussed tintinnid LOD distribution on a large scale in Antarctic waters. In the present study, the dominant LOD size-class was found to be 32–36 μm, and there were evident differences in the LOD composition among the SAA, PFA, and AA from the SAZ to the AZ in the Amundsen Sea. Tintinnids with small-sized LODs (< 32 μm) were mainly located in the SAA and tended to be distributed in the SAZ; those with large-sized LOD (> 88 μm) were mainly located in the AA and tended to inhabit the AZ; and those with small or large LOD mixed in the PFA (Fig. 9). Lee et al. (2012) reported that large-celled phytoplankton (> 20 μm, 64.1%) were dominant in the polynya near the Antarctic continent, and small-celled phytoplankton were mainly distributed northward to the non-polynya area in the Amundsen Sea. Therefore, the higher abundance proportion of the large tintinnid LOD size-class in the AZ may relate to the greater amount of large phytoplankton in this area.

5 ConclusionsIn summary, our study finds that the PF is an important dividing zone of Subantarctic and Antarctic tintinnid assemblages. Some tintinnid species occur only in the southern (or northern) boundary of the PF, but some species occur on both sides. The PF contains indigenous tintinnid species, and species in the AZ and SAZ have different expansion abilities. The species with the strongest expansion ability from the SAZ and AZ mixed in the PF. In addition to the species difference between the SAA and AA, larger LOD species are found in the AA rather than the SAA. Our study of tintinnid assemblages in the PF is based on data from only one transect; therefore, more investigations are required in the PF in other parts of the Southern Ocean, to determine any temporal and spatial variations.

AcknowledgementsWe thank the 34th CHINARE Antarctic expedition for providing logistical support and environmental data. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41576164), the CNRS-NSFC Joint Research Projects Program (No. 41711530149), the National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2017YFC14 04402), the Senior User Project of RV KEXUE (No. KE XUE2018G17), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41876217), the Chinese Polar Environment Comprehensive Investigation & Assessment Programmes (No. CHINARE2016-01-05), and the Scientific and Technological Innovation Project by Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (No. 2015ASK J02).

Alder, V. A., 1999. Tintinnoinea. In: South Atlantic Zooplankton. Boltovskoy, D., ed., Backhuys, Leiden, 321-384.

(  0) 0) |

Alder, V. A. and Boltovskoy, D., 1991a. Microplanktonic distributional patterns west of the Antarctic Peninsula, with special emphasis on the tintinnids. Polar Biology, 11(2): 103-112. (  0) 0) |

Alder, V. A. and Boltovskoy, D., 1991b. The ecology and biogeography of tintinnid ciliates in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean. Marine Chemistry, 35(1-4): 337-346. DOI:10.1016/S0304-4203(09)90026-3 (  0) 0) |

Attrill, M. J. and Rundle, S. D., 2002. Ecotone or ecocline: Ecological boundaries in estuaries. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science, 55(6): 929-936. DOI:10.1006/ecss.2002.1036 (  0) 0) |

Boltovskoy, D. and Alder, V. A., 1992. Microzooplankton and tintinnid species-specific assemblage structures: Patterns of distribution and year-to-year variations in the Weddell Sea (Antarctica). Journal of Plankton Research, 14(10): 1405-1423. DOI:10.1093/plankt/14.10.1405 (  0) 0) |

Boltovskoy, D., Alder, V. A. and Spinelli, F., 1989. Summer Weddell Sea microplankton: Assemblage structure, distribution and abundance, with special emphasis on the Tintinnina. Polar Biology, 9(7): 447-456. DOI:10.1007/BF00443232 (  0) 0) |

Boltovskoy, D., Dinofrio, E. O. and Alder, V. A., 1990. Intraspecific variability in Antarctic tintinnids: The species group. Journal of Plankton Research, 12(2): 403-413. (  0) 0) |

Buck, K. R., Garrison, D. L. and Hopkins, T. L., 1992. Abundance and distribution of tintinnid ciliates in an ice edge zone during the austral autumn. Antarctic Science, 4(1): 3-8. DOI:10.1017/S0954102092000038 (  0) 0) |

Dolan, J. R., 2010. Morphology and ecology in tintinnid ciliates of the marine plankton: Correlates of lorica dimensions. Acta Protozoologica, 49: 235-244. (  0) 0) |

Dolan, J. R. and Yang, E. J., 2017. Observations of apparent lorica variability in Salpingacantha (Ciliophora: Tintinnida) in the northern Pacific and Arctic Oceans. Acta Protozoologica, 56: 221-224. (  0) 0) |

Dolan, J. R., Claustre, H. and Vidussi, F., 1999. Planktonic ciliates in the Mediterranean Sea: Longitudinal trends. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅰ – Oceanographic Research Papers, 46: 2025-2039. DOI:10.1016/S0967-0637(99)00043-6 (  0) 0) |

Dolan, J. R., Claustre, H., Carlotti, F., Plounevez, S. and Moutin, T., 2002. Microzooplankton diversity: Relationships of tintinnid ciliates with resources, competitors and predators from the Atlantic coast of Morocco to the eastern Mediterranean. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅰ – Oceanographic Research Papers, 49(7): 1217-1232. DOI:10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00021-3 (  0) 0) |

Dolan, J. R., Jacquet, S. and Torreton, J. P., 2006. Comparing taxonomic and morphological biodiversity of tintinnids (planktonic ciliates) of New Caledonia. Limnology Oceanography, 51(2): 950-958. DOI:10.4319/lo.2006.51.2.0950 (  0) 0) |

Dolan, J. R., Pierce, R. W., Yang, E. J. and Kim, S. Y., 2012. Southern Ocean biogeography of tintinnid ciliates of the marine plankton. Journal Eukaryotic Microbiology, 59(6): 511-519. DOI:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00646.x (  0) 0) |

Dolan, J. R., Yang, E. J., Kang, S. H. and Rhee, T. S., 2016. Declines in both redundant and trace species characterize the latitudinal diversity gradient in tintinnid ciliates. ISME Journal, 10(9): 2174-2183. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2016.19 (  0) 0) |

Dolan, J. R., Yang, E. J., Lee, S. H. and Kim, S. Y., 2013. Tintinnid ciliates of the Amundsen Sea (Antarctica) plankton communities. Polar Research, 32: 19784. DOI:10.3402/polar.v32i0.19784 (  0) 0) |

Feng, M. P., Wang, C. F., Zhang, W. C., Zhang, G. T., Xu, H. L., Zhao, Y., Xiao, T., Wang, C. S., Wang, W. D., Bi, Y. X. and Liang, J., 2018. Annual variation of species richness and lorica oral diameter characteristics of tintinnids in a semi-enclosed bay of western Pacific. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science, 207: 164-174. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2018.04.003 (  0) 0) |

Hada, Y., 1970. The protozoan plankton of the Antarctic and subantarctic seas. JARE Scientific Reports, Series E, 31: 1-51. (  0) 0) |

Heinbokel, J., 1978. Studies on the functional role of tintinnids in the southern California bight. Ⅱ. Grazing rates of field populations. Marine Biology, 47(2): 191-197. DOI:10.1007/BF00395639 (  0) 0) |

Jacobs, S. S., Hellmer, H. H. and Jenkins, A., 1996. Antarctic ice sheet melting in the southeast Pacific. Geophysical Research Letters, 23(9): 957-960. DOI:10.1029/96GL00723 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, Y., Liu, Q., Yang, E. J., Wang, M., Kim, T. W., Cho, K. H. and Lee, S. H., 2016a. Pelagic ciliate communities within the Amundsen Sea polynya and adjacent sea ice zone, Antarctica. Deep Sea Research Ⅱ – Topical Studies in Oceanography, 123: 69-77. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.04.015 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, Y., Liu, Q., Yang, E. J., Wang, M., Lee, Y. J. and Lee, S. H., 2016b. An approach to bioassess pelagic ciliate biodiversity at different taxonomic resolutions in response to various habitats in the Amundsen Sea (Antarctica). Polar Biology, 39: 485-495. DOI:10.1007/s00300-015-1801-1 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, Y., Yang, E. J., Kim, S. Y., Kim, Y. N. and Lee, S. H., 2014. Spatial patterns in pelagic ciliate community responses to various habitats in the Amundsen Sea (Antarctica). Progress in Oceanography, 128: 49-59. DOI:10.1016/j.pocean.2014.08.006 (  0) 0) |

Kato, S. and Taniguchi, A., 1993. Tintinnid ciliates as indicator species of different water masses in the western North Pacific polar front. Fisheries Oceanography, 2(3-4): 166-174. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2419.1993.tb00132.x (  0) 0) |

Kent, M., Gill, W. J., Weaver, R. E. and Armitage, R. P., 1997. Landscape and plant community boundaries in biogeography. Progress in Physical Geography, 21(3): 315-353. DOI:10.1177/030913339702100301 (  0) 0) |

Kim, S. Y., Choi, J. K., Dolan, J. R., Shin, H. C., Lee, S. H. and Yang, E. J., 2013. Morphological and ribosomal DNA-based characterization of six Antarctic ciliate morphospecies from the Amundsen Sea with phylogenetic analyses. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 60(5): 497-513. DOI:10.1111/jeu.12057 (  0) 0) |

Kofoid, C. A., and Campbell, A. S., 1929. A Conspectus of the Marine and Fresh-Water Ciliata Belonging to the Suborder Tintinnoinea, with Description of the Suborder Tintinnoinea, with Description of New Species Principally from Agassiz Expedition to the Eastern Tropical Pacific, 1904–1905. University of California Press, California, 1-403.

(  0) 0) |

Kofoid, C. A., and Campbell, A. S., 1939. The Ciliata: The Tintinnoinea. Reports on the Scientific Results of the Expedition to the Eastern Tropical Pacific, 1904–1905. Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College, Cambridge, 1-474.

(  0) 0) |

Laackmann, H., 1910. Die Tintinnodeen der Deutschen Süd-polar-Expedition 1901–1903. Deutschen Stüdpolar – Expedition XI Zoologie Ⅲ, 11: 340-396. (  0) 0) |

Lee, S. H., Kim, B. K., Yun, M. S., Joo, H. T., Yang, E. J., Kim, Y. N., Shin, H. C. and Lee, S. H., 2012. Spatial distribution of phytoplankton productivity in the Amundsen Sea, Antarctica. Polar Biology, 35(11): 1721-1733. DOI:10.1007/s00300-012-1220-5 (  0) 0) |

Li, H. B., Zhao, Y., Chen, X., Zhang, W. C., Xu, J. H., Li, J. and Xiao, T., 2016. Interaction between neritic and warm water tintinnids in surface waters of East China Sea. Deep Sea Research Ⅱ – Topical Studies in Oceanography, 124: 84-92. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.06.008 (  0) 0) |

Liang, C., Li, H. B., Dong, Y., Zhao, Y., Tao, Z. C., Li, C. L., Zhang, W. C. and Gregori, G., 2018. Planktonic ciliates in different water masses in open waters near Prydz Bay (East Antarctica) during austral summer, with an emphasis on tintinnid assemblages. Polar Biology, 41(11): 2355-2371. DOI:10.1007/s00300-018-2375-5 (  0) 0) |

Longhurst, A., 2007. Ecological Geography of the Sea. Academic Press, New York, 1-35.

(  0) 0) |

Lynn, D. H., 2008. Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature. 3rd edition. Springer,, Berlin, 1-455.

(  0) 0) |

Martinson, D. and McKee, D., 2012. Transport of warm upper circumpolar deep water onto the western Antarctic Peninsula continental shelf. Ocean Science, 8: 433-442. DOI:10.5194/os-8-433-2012 (  0) 0) |

Moffat, C., Owens, B. and Beardsley, R. C., 2009. On the characteristics of circumpolar deep water intrusions to the west Antarctic Peninsula continental shelf. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 114: C05017. (  0) 0) |

Montagnes, D. J. S., 2013. Ecophysiology and behavior of tintinnids. In: The Biology and Ecology of Tintinnid Ciliates: Models for Marine Plankton. Dolan, J. R., et al., eds., WileyBlackwell, Oxford, 86-122.

(  0) 0) |

Orsi, A. H., Whitworth, T. and Nowlin, W. D., 1995. On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅰ – Oceanographic Research Papers, 42(5): 641-673. DOI:10.1016/0967-0637(95)00021-W (  0) 0) |

Paranjape, M. A. and Gold, K., 1982. Cultivation of marine pelagic protozoa. Annales de l' Institut Oceanographique (Paris), 58: 143-150. (  0) 0) |

Pollard, R. T., Lucas, M. I. and Read, J. F., 2002. Physical controls on biogeochemical zonation in the Southern Ocean. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ – Topical Studies in Oceanography, 49(16): 3289-3305. DOI:10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00084-X (  0) 0) |

Ribalet, F., Marchetti, A., Hubbard, K. A., Brown, K., Durkin, C. A., Morales, R., Robert, M., Swalwell, J. E., Tortell, P. D. and Armbrust, E. V., 2010. Unveiling a phytoplankton hotspot at a narrow boundary between coastal and offshore waters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(38): 16571-16576. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1005638107 (  0) 0) |

Schlitzer, R., 2003. Ocean Data View. http://www.awi-bremerhaven.de/GEO/ODV.

(  0) 0) |

Shepherd, A., Wingham, D. and Rignot, E., 2004. Warm ocean is eroding West Antarctic ice sheet. Geophysical Research Letters, 31(23): 1-4. (  0) 0) |

Sokolov, S. and Rintoul, S. R., 2009. Circumpolar structure and distribution of the Antarctic circumpolar current fronts: 1. Mean circumpolar paths. Journal of Geophysical Research, 114(C11): C11018. DOI:10.1029/2008JC005108 (  0) 0) |

Thoma, M., Jenkins, A., Holland, D. and Jacobs, S., 2008. Modelling circumpolar deep water intrusions on the Amundsen Sea continental shelf, Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters, 35: L18602. (  0) 0) |

Thompson, G. A., 2004. Tintinnid diversity trends in the southwestern Atlantic Ocean (29 to 60°S). Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 35(1): 93-103. (  0) 0) |

Thompson, G. A. and Alder, V. A., 2005. Patterns in tintinnid species composition and abundance in relation to hydrological conditions of the southwestern Atlantic during austral spring. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 40(1): 85-101. (  0) 0) |

Thompson, G. A., Alder, V. A. and Boltovskoy, D., 2001. Tintinnids (Ciliophora) and other net microzooplankton (> 30 µm) in southwestern Atlantic shelf break waters. Marine Ecology, 22(4): 343-355. DOI:10.1046/j.1439-0485.2001.01723.x (  0) 0) |

Walker, D. P., Jenkins, A., Assmann, K. M., Shoosmith, D. R. and Brandon, M. A., 2013. Oceanographic observations at the shelf break of the Amundsen Sea, Antarctica. Journal of Geophysical Research, 118(6): 2906-2918. (  0) 0) |

Whitworth, T., 1980. Zonation and geostrophic flow of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current at Drake Passage. Deep Sea Research Part A – Oceanographic Research Papers, 27(7): 497-507. DOI:10.1016/0198-0149(80)90036-9 (  0) 0) |

Wickham, S. A., Steinmair, U. and Kamennaya, N., 2011. Ciliate distributions and forcing factors in the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas (Antarctic). Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 62(3): 215-230. (  0) 0) |

Yager, P. L., Sherrell, R. M., Stammerjohn, S. E., Alderkamp, A. C., Schofield, O., Abrahamsen, E. P., Arrigo, K. R., Bertilsson, S., Garay, D. L., Guerrero, R., Lowry, K. E., Moksnes, P., Ndungu, K., Post, A. F., Randall-Goodwin, E., Riemann, L., Severmann, S., Thatje, S., van Dijken, G. L. and Wilson, S., 2012. ASPIRE: The Amundsen Sea polynya international research expedition. Oceanography, 25(3): 40-53. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, W. C., Feng, M. P., Yu, Y., Zhang, C. X. and Xiao, T., 2012. An Illustrated Guide to Contemporary Tintinnids in the World. Science Press, Beijing, 1-499.

(  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19