2) Ocean College, Zhejiang University, Zhoushan 316021, China;

3) Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China;

4) Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

As a basic form of seawater motion, tides play an important role in ocean mixing (Munk and Wunsch, 1998). Studies indicate that one-third of barotropic tidal energy is dissipated in the deep ocean, whereas the remaining energy is lost directly to bottom friction in shallow seas and on the continental shelf (Egbert and Ray, 2001; Carter et al., 2012). Strong tidal currents are reduced near the bottom, thus creating a vertical shear. Shear-generated turbulence enhances vertical mixing, contributing to upward nutrient transportation and biological activities (Thorpe, 2007). Therefore, the knowledge of turbulent mixing induced by tidal currents near the bottom is important for understanding both physical motions and biochemical processes.

The eddy viscosity is an important parameter for quantifying the mixing structure in the bottom boundary layer. The eddy viscosity is estimated from the observed quantities, such as current velocity. Attempts have been made where eddy viscosity profiles are specified as vertically constant or linear (Prandle, 1982; Soulsby, 1983), or investigated relying on the turbulence closure model (Werner et al., 2003). Yoshikawa and Endoh (2015) compared three methods for estimating turbulent mixing structures. These methods are considered because the mean velocity profiles are determined by the mean eddy viscosity in the bottom boundary layer. Therefore, the mean eddy viscosity can be estimated by solving the Ekman balance equations using the least squares methods. Cao et al. (2017) proposed an alternative scheme consisting of the bottom Ekman boundary layer model and its adjoint model as well as a minimization algorithm. They validated its performance with twin experiments but did not apply it to the practical context for lack of observations.

The East China Sea (ECS) boasts a vast continental shelf and strong tidal motions (Kang et al., 2002; Niwa and Hibiya, 2004). Many observations have been made to investigate the turbulence in this area (Liu et al., 2009; Lozovatsky et al., 2012, 2015; Song et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020); however, these observations are still limited compared to the vastness of the ECS. Therefore, the investigation of tidal motions and turbulent mixing induced by tides in various regions is important and beneficial in deepening our understanding of the dynamics in the ECS. In this study, based on three records of the current velocity measured by acoustic Doppler current profilers (ADCPs) in the western ECS, we estimated the eddy viscosity profiles in the bottom Ekman boundary layer for two purposes. First, we need to assess the performance of the scheme proposed by Cao et al. (2017) in the real sea and compare it with the performance of other schemes. Second, we need to provide a turbulent mixing structure in the western ECS near Yangtze Estuary.

The paper is organized as follows. The observations and methods for estimating eddy viscosity are introduced in Section 2. In Section 3, characteristics of tidal currents and turbulence mixing induced by tides at three stations are presented. Section 4 summarizes the paper.

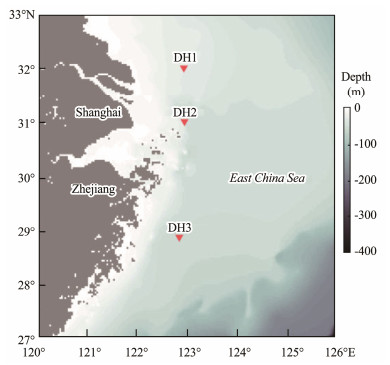

2 Data and Methods 2.1 Current DataCurrent data of Wang et al. (2019) were used in this study. The data were measured using moored ADCPs at three stations (Fig.1): Station DH1 located at 122˚56.149΄E, 31˚59.803΄N, where the water depth is 34.3 m; Station DH2 at 122˚56.882΄E, 31˚01.450΄N, with a depth of 47.0 m; and Station DH3 at 122˚50.684΄E, 28˚54.826΄N, with a depth of 61.8 m. The ADCPs deployed at the three stations operated from June 12 to August 22, June 11 to September 4, and June 12 to October 20, 2014, respectively. All velocity profiles were collected every 30 minutes with a 2.0-m bin size. The first available bin of ADCP is 4.8 m above the bottom of the ocean.

|

Fig. 1 Locations of three ADCP stations (DH1, DH2, and DH3) in the ECS. |

The measured current velocity was used to estimate the eddy viscosity because the mean velocity profiles are determined by the mean turbulent mixing in the bottom boundary layer where the turbulent mixing term is dominant in the momentum equations. The governing equation for velocity in the bottom Ekman boundary layer is

| $ \frac{{\partial w}}{{\partial t}} + {\text{i}}fw = \frac{\partial }{{\partial z}}\left[ {\mu (z)\frac{{\partial w}}{{\partial z}}} \right], $ | (1) |

where w = u + iv is the complex horizontal current vector, t is the time, f is the Coriolis frequency, z is the height above the seafloor, and μ is the eddy viscosity coefficient. Represent a tidal current of frequency ω by

| $ w(z, t) = W(z)\exp ({\text{i}}\omega t) . $ | (2) |

According to Yoshikawa and Endoh (2015),

| $ W(z) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \begin{gathered} \frac{{{A_U}\cos {g_U} + {A_V}\sin {g_V}}}{2} + {\text{i}}\frac{{{A_V}\cos {g_V} - {A_U}\sin {g_U}}}{2}, \hfill \\ {\text{ }}\omega > 0 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \\ \begin{gathered} \frac{{{A_U}\cos {g_U} - {A_V}\sin {g_V}}}{2} + {\text{i}}\frac{{{A_V}\cos {g_V} + {A_U}\sin {g_U}}}{2}, \hfill \\ {\text{ }}\omega < 0 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \end{array}} \right., $ | (3) |

where ω > 0 corresponds to the counterclockwise-rotating current component and ω < 0 corresponds to the clockwise-rotating component; AU (AV) and gU (gV) are the conventional tidal harmonic coefficients of the zonal (meridional) velocities. If the tides are barotropic in the interior layer, the boundary layer component W(z) can be calculated as follows:

| $ W(z) = \bar W(z) - \bar W(H + \delta), $ | (4) |

where

| $ {\text{i}}(f + \omega)W(z) = \frac{\partial }{{\partial z}}\left[ {\mu (z)\frac{\partial }{{\partial z}}W(z)} \right] . $ | (5) |

The discretized form of Eq. (5) is

| $\begin{align} {\text{i}}(f + {\omega _n}){W_{k + 1/2, n}}\Delta z = &{\mu _{k + 1}}\frac{{{W_{k + 3/2, n}} - {W_{k + 1/2, n}}}}{{\Delta z}} - \\& {\mu _k}\frac{{{W_{k + 1/2, n}} - {W_{k - 1/2, n}}}}{{\Delta z}}, \end{align}$ | (6) |

where n represents the tidal component (e.g., n = 1 is the clockwise component of the M2 tide) and k is the vertical level. The first two schemes used to estimate the eddy viscosity are based on the above equation and the least squares method.

2.2.1 Scheme 1Scheme 1 was first used by Yoshikawa et al. (2010). It assumes that errors are included in Eq. (6):

| $\begin{align} {\text{i}}(f + {\omega _n}){W_{k + 1/2, n}}\Delta z = &{\mu _{k + 1}}\frac{{{W_{k + 3/2, n}} - {W_{k + 1/2, n}}}}{{\Delta z}} - \\& {\mu _k}\frac{{{W_{k + 1/2, n}} - {W_{k - 1/2, n}}}}{{\Delta z}} + {\varepsilon _{k, n}} . \end{align}$ | (7) |

Note that εk, n is a complex number. The sum of the squared εk, n is defined as

| $ E = \sum\limits_{k, n} {{\varepsilon _{k, n}}\varepsilon _{k, n}^*}, $ | (8) |

where * denotes the complex conjugate. To minimize E, it is required that

| $ \frac{1}{2}\frac{{\partial E}}{{\partial {\mu _k}}} = 0, \frac{1}{2}\frac{{\partial E}}{{\partial {\mu _k}}} = 0{\text{ }}(2 \leqslant k \leqslant K - 1), \frac{1}{2}\frac{{\partial E}}{{\partial {\mu _1}}} = 0 . $ | (9) |

The above equations are solved to obtain μk for all vertical levels.

2.2.2 Scheme 2Scheme 2 was proposed by Yoshikawa and Endoh (2015). In this scheme, Eq. (6) is integrated from zk to zK = H, and the errors are assumed in the integrated equations:

| $\begin{array}{l} \sum\limits_{k' = k}^{K - 1} {{\text{i}}(f + {\omega _n}){W_{k' + 1/2, n}}\Delta z} = {\mu _K}\frac{{{W_{K + 1/2, n}} - {W_{K - 1/2, n}}}}{{\Delta z}} - \\ \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; {\mu _k}\frac{{{W_{k + 1/2, n}} - {W_{k - 1/2, n}}}}{{\Delta z}} + {\varepsilon _{k, n}} .\end{array} $ | (10) |

Taking partial derivatives of E with respect to μk and setting them equal to zero, μk can be obtained by solving the resulting equations:

| $ \frac{1}{2}\frac{{\partial E}}{{\partial {\mu _K}}} = 0, \frac{1}{2}\frac{{\partial E}}{{\partial {\mu _k}}} = 0{\text{ }}(1 \leqslant k \leqslant K - 1) . $ | (11) |

The third scheme used in the study is based on the adjoint method. Details can be found in Cao et al. (2017), and this scheme is also summarized as follows. The scheme is composed of the bottom Ekman boundary layer model and its adjoint model, as well as a minimization algorithm. The eddy viscosity profiles in the bottom Ekman boundary layer can be estimated by assimilating observations (harmonic constants of tidal currents).

The bottom Ekman boundary layer model is introduced above (Eqs. (1) – (6)).

The adjoint model development begins with the cost function calculation:

| $ J = \sum\limits_n {\left[ {{\beta _n}\int {\frac{{{M_{{\text{obs}}}}}}{{\text{2}}}({W_n} - {{\hat W}_n}){{({W_n} - {{\hat W}_n})}^*}{\text{d}}z} } \right]}, $ | (12) |

where βn is the weight coefficient, Wn is the simulated results of the bottom Ekman boundary layer model,

The Lagrangian function is constructed as

| $ L = J + \sum\limits_n {\left\{ {{\beta _n}\int {\lambda _n^*\left[ {{\text{i}}(f + {\omega _n}){W_n} - \frac{\partial }{{\partial z}}\left({\mu \frac{{\partial {W_n}}}{{\partial z}}} \right)} \right]{\text{d}}z} } \right\}}, $ | (13) |

where λn = λr, n + iλi, n is the complex adjoint variable of Wn.

The adjoint model is derived from

| $ \frac{\partial }{{\partial z}}\left({\mu \frac{{\partial \lambda _n^*}}{{\partial z}}} \right) - {\text{i}}(f + {\omega _n})\lambda _n^* = {M_{{\text{obs}}}}({W_n} - {\hat W_n}), $ | (14) |

with boundary conditions

| $ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {\lambda _n^* = 0, {\text{ at }}z = Z} \\ {\lambda _n^* = 0, {\text{ at }}z = 0} \end{array}} \right. . $ |

Assuming that Wn is a single-valued function of μ, when the simulated Wn approaches the observation, the estimated μ should be close to its real value. Therefore, there exists a minimization problem, min: J(μ), which can be solved by adopting the gradient descent algorithm. The gradient of the cost function with respect to the eddy viscosity coefficient is

| $ \frac{{\partial J}}{{\partial \mu }} = \sum\limits_n {\left[ {{\beta _n}{\rm{Re}} \left({\frac{{\partial \lambda _n^*}}{{\partial z}}\frac{{\partial {W_n}}}{{\partial z}}} \right)} \right]}, $ | (15) |

where Re indicates the real component. Considering that the eddy viscosity coefficients can vary by several orders of magnitudes in the bottom Ekman boundary layer, the gradient of the cost function with respect to the logarithm of the eddy viscosity coefficient is used in the minimization algorithm:

| $ \frac{{\partial J}}{{\partial {{\log }_{10}}\mu }} = \mu \ln 10\frac{{\partial J}}{{\partial \mu }} = \mu \ln 10\sum\limits_n {\left[ {{\beta _n}{\rm{Re}} \left({\frac{{\partial \lambda _n^*}}{{\partial z}}\frac{{\partial {W_n}}}{{\partial z}}} \right)} \right]} . $ | (16) |

According to the gradient descent algorithm,

| $ x_k^{t + 1} = x_k^t - {\alpha ^t}\nabla J(x_k^t), $ | (17) |

where x = log10 μ, α is the step factor, and ∇J(x) denotes the gradient of J with respect to x, and t is the index of iteration steps. The initial value

| $ {\alpha ^t} = \frac{{{\alpha ^0}}}{{{{\left\| {\nabla J(x_k^t)} \right\|}_2}}}, $ | (18) |

where α0 is a constant obtained through a trial-and-error procedure and

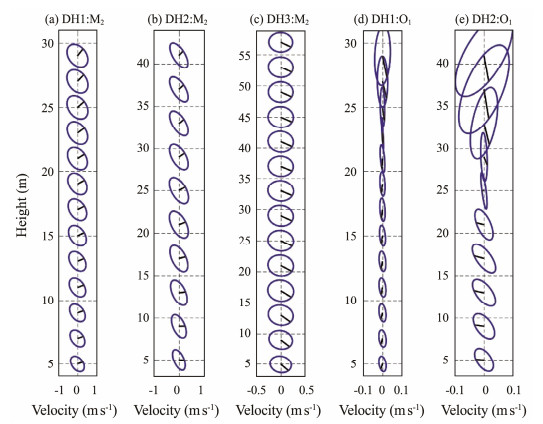

Harmonic analysis was first conducted on current velocity data to describe the characteristics of tides and to choose the tidal constitutes suitable for estimating the eddy viscosity. The t_tide toolbox (Pawlowicz et al., 2002) was applied to perform harmonic analysis (HA), which resolved 35 constituents based on the automated decision tree of Foreman (1977). Notably, only the M2 and O1 constituents were further analyzed according to the observing periods (for approximately 2 – 4 months). Additionally, the results of O1 at DH3 were ignored because of their small magnitudes and relatively large confidence intervals. Fig.2 shows the vertical structures of the M2 and O1 tidal ellipses at the three stations. At first glance, we find that the M2 tide is much stronger than the O1 tide, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Kang et al., 1998; Fang et al., 2004). The M2 tide is dominated by the barotropic component, displaying a uniform character throughout the water column except near the bottom, which is consistent with previous observations (Wang et al., 1999). The tidal ellipses at stations DH1 and DH2 are circular and aligned in the northwest-southeast directions. The M2 tide at station DH3 is weaker than those at the other two stations and shows a more circular shape. The O1 tide shows a different feature from the M2 tide. The O1 tides are surface intensified, and the variance of their Greenwich phase with depths is relatively large. The O1 tide is more rectilinear compared to the M2 tide. The major axis orientation of the O1 tide at station DH1 is mainly north-south. At station DH2, the direction changes downward from northeast-southwest to northwest-southeast. In a word, the O1 tides are much weaker and show more changes in the vertical direction.

|

Fig. 2 Vertical structures of the M2 and O1 tidal ellipses at the three stations. The ellipses are centered at their corresponding measurement depths. The lines from the center show the Greenwich phases. Note that the x-axis and y-axis limits in these subfigures are different. |

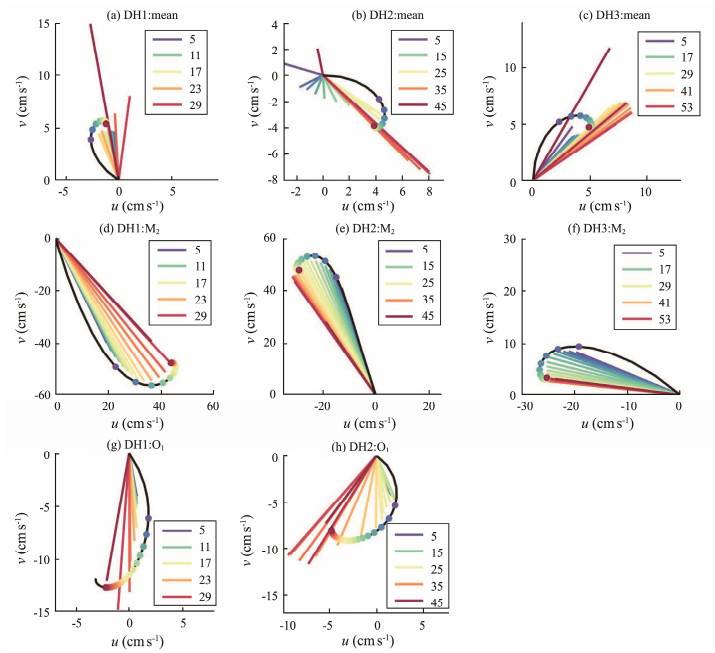

Fig.3 shows the vertical structures of the M2, O1, and mean currents (time average of the observed velocity during the entire period) at the three stations. The tidal velocity vector is displayed when the velocity at a 25-m height reaches its maximum. The classic Ekman solutions are also plotted for reference. They are calculated with a constant eddy viscosity of 10−3 m2 s−1 as follows:

| $ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {w = W\exp ({\text{i}}\omega t)\left({1 - \exp \left({ - (1 + i)\frac{z}{{{\delta _E}}}} \right)} \right), {\text{ for }}f + \omega > 0} \\ {w = W\exp ({\text{i}}\omega t)\left({1 - \exp \left({ - (1 - i)\frac{z}{{{\delta _E}}}} \right)} \right), {\text{ for }}f + \omega < 0} \end{array}} \right., $ | (19) |

|

Fig. 3 Vertical structure of the (top) mean currents, (middle) M2, and (bottom) O1 at stations (left) DH1, (middle) DH2, and (right) DH3. The tidal velocity vectors at various heights (label) are displayed when the velocity reaches its maximum at the height of 25 m. The analytical Ekman solutions are also shown by black lines, with colored dots representing the height from the bottom. |

where

| $ {\delta _E} = {\left({\frac{{2{\mu _0}}}{{\left| {f + \omega } \right|}}} \right)^{1/2}} . $ |

The features of the M2 tidal currents are consistent with the classical Ekman theory in the bottom boundary layer. The currents rotate clockwise downward, and their magnitudes change slightly above around 20 m and decrease near the bottom. The O1 tidal currents show a counterclockwise rotation with depth, which can be explained by the classical Ekman theory. However, their magnitude is much weaker than the M2 tide and deviates further from the corresponding theoretical solution. The mean currents are also feeble, which are less than 5 cm s−1 within 20 m height from the bottom. At stations DH1 and DH2, the mean current rotates clockwise with the increase of water depth, which is opposite to the direction predicted by the Ekman theory and can be attributed to small values (Yoshikwa et al., 2010). At station DH3, the rotation of the mean current is consistent with the theory.

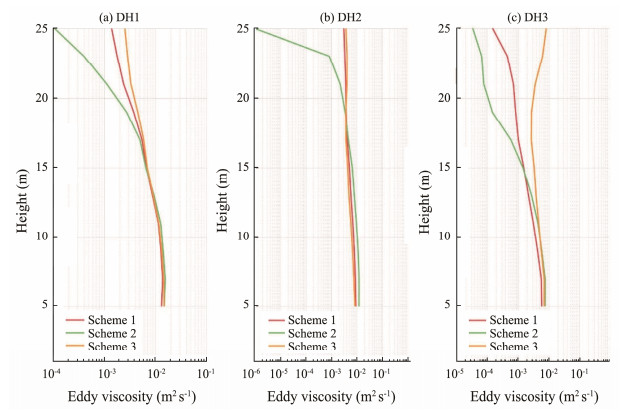

3.2 Eddy Viscosity in the Bottom Boundary LayerAccording to Yoshikawa and Endoh (2015) and Cao et al. (2017), the use of a stronger tidal constituent improves the eddy viscosity estimation. We use the M2 tide to estimate the eddy viscosity because it is strong and shows a typical bottom Ekman spiral.

The boundary layer height, H, needs to be given a priori to calculate the Ekman boundary layer velocity. Although depths at the three stations vary from 30 to 60 m, the vertical structures of the M2 tide in Figs.2 and 3 show that the velocity varies above the 20 m height, indicating that H at all these stations is similar. As suggested by Yoshikawa and Endoh (2015), we tried various values for H and set the top of the boundary layer at 25 m for all three stations. Fig.4 shows eddy viscosity profiles estimated from the three schemes at the ADCP stations. Overall, these profiles have a similar pattern – they show the maximum values at approximately 5 m height and decrease exponentially with the height (except that estimated by scheme 3 at EH3, which increases gradually above 20 m). The exponent decay rates are different because of various density profiles. At stations DH1 and DH2, results of the three schemes are close below the height of 20 m; however, near the top of the boundary layer, the eddy viscosity estimated by scheme 1 decreases to a value smaller than the other two schemes by 1 – 3 orders of magnitude. At station DH3, profiles estimated from the three schemes depart from each other above the height of 15 m, and their difference is larger compared to the other two stations. According to Yoshikawa and Endoh (2015), scheme 2 is susceptible to the balance error, which is relatively large in ADCP data observed in the ECS and which can account for the difference between estimation using scheme 2 and other schemes. The eddy viscosity profiles, even if estimated using the same schemes, differ at each station and from previous studies in the ECS (e.g., the first two schemes are used in Yoshikawa and Endoh (2015) to estimate eddy viscosity profiles at two stations in the ECS, the one located at 31˚45΄N, 127˚25΄E and the other at 31˚45΄N, 125˚30΄E), indicating that turbulence characteristics in the bottom boundary layer are site-independent and it is important to make more quantifications based on observations.

|

Fig. 4 Eddy viscosity profiles estimated from three schemes at stations (a) DH1, (b) DH2, and (c) DH3. |

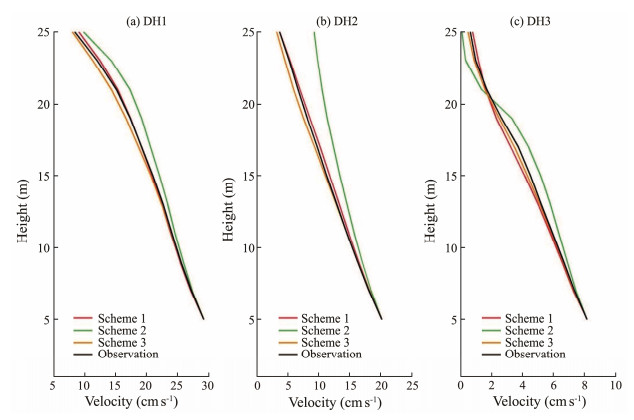

Velocity profiles were reproduced with the estimated eddy viscosity (according to Eq. (6)) and compared with the observations for validation because the true values of the eddy viscosity are unknown. The magnitudes of the M2 tide are shown in Fig.5. All the reproduced velocities show a decreasing trend with height, which is similar to the observations. The profiles estimated with schemes 1 and 3 are much closer to the observations than those estimated with scheme 2. The depth-averaged root mean square of the errors of schemes 1 and 3 are smaller than that of scheme 2 by one order of magnitude at DH1 and DH2 (e.g., 0.27, 1.33, and 0.45 cm s−1 for the three schemes, respectively, at DH1). At DH3, the error of scheme 2 is also the largest. The results indicate that the eddy viscosity profiles estimated from schemes 1 and 3 are close to the true values.

|

Fig. 5 Magnitude of the M2 tide reproduced with schemes 1, 2, and 3 at three stations. |

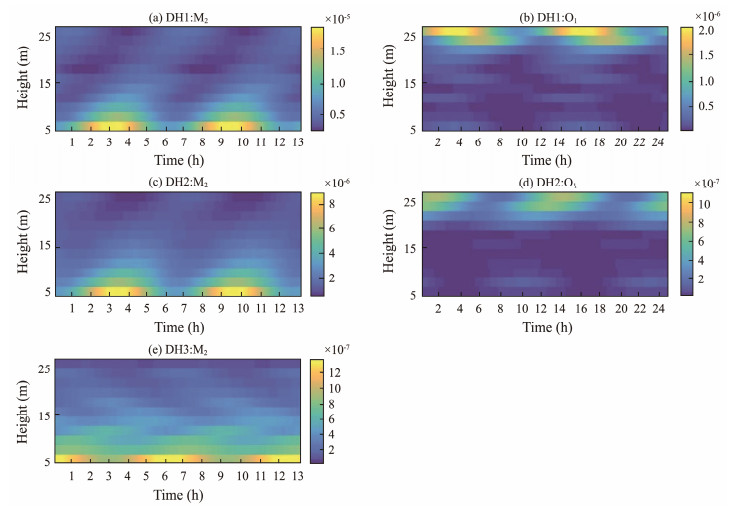

Based on the eddy viscosity estimated by scheme 3, the shear production of the turbulent kinetic energy of the M2 and O1 tides is calculated as follows:

| $ SPR = \mu (z)\left({{{\left({\frac{{\partial u}}{{\partial z}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left({\frac{{\partial v}}{{\partial z}}} \right)}^2}} \right) . $ | (20) |

The results are displayed in Fig.6. Both show a periodic character, which is consistent with the corresponding tidal constituents. However, their characteristics are different from each other. In terms of magnitude, the M2 shear production is larger than that of the O1 tide by 1 order of magnitude at each station. In terms of the vertical structure, the M2 shear production intensifies as it approaches the bottom, which is consistent with the theory of the bottom Ekman boundary layer. In contrast, the O1 shear production is larger within the layer of height 20 – 25 m.

|

Fig. 6 Shear production of the TKE of the M2 and O1 tides in a tidal period at three stations. |

In this study, tidal characteristics at three stations in the ECS are analyzed, and the velocity profiles are used to estimate the eddy viscosity in the bottom boundary layer. The M2 tide takes a dominant role and shows a barotropic feature, whereas the O1 tide is much weaker and shows more changes in the vertical direction. Based on the M2 tide, three schemes for estimating the eddy viscosity are compared. The results show that schemes 1 and 3 perform well in the western ECS near the Yangtze River. The estimated eddy viscosity shows the maximum values at approximately 5 m height and decreases exponentially with the height. The values vary within 10−4 – 10−2 m2 s−1. Shear production of the turbulent kinetic energy of the M2 and O1 tides shows unique characteristics in terms of structure and magnitude. The shear production of the M2 tide is much stronger than the diurnal tide and bottom intensified, whereas that of the O1 tide shows larger values within the 15 – 25 m height range.

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LY21D060005), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2022MD082), the Joint Project of Zhoushan Municipality and Zhejiang University (No. 2019C810060), the Open Fund Project of Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Information Technology and the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDA19060201).

Cao, A. Z., Chen, H., Fan, W., He, H. L., Song, J. B., and Zhang, J. C., 2017. Estimation of eddy viscosity profile in the bottom Ekman boundary layer. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 34(10): 2163-2175. DOI:10.1175/JTECH-D-17-0064.1 (  0) 0) |

Carter, G. S., Fringer, O. B., and Zaron, E. D., 2012. Regional models of internal tides. Oceanography, 25(2): 56-65. DOI:10.5670/oceanog.2012.42 (  0) 0) |

Egbert, G. D., and Ray, R. D., 2001. Estimates of M2 tidal energy dissipation from TOPEX/Poseidon altimeter data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C10): 22475-22502. DOI:10.1029/2000JC000699 (  0) 0) |

Fang, G., Wang, Y., Wei, Z., Choi, B. H., Wang, X., and Wang, J., 2004. Empirical cotidal charts of the Bohai, Yellow, and East China Seas from 10 years of TOPEX/Poseidon altimetry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 109: C11006. DOI:10.1029/2004JC002484 (  0) 0) |

Foreman, M. G. G., 1977. Manual for Tidal Heights Analysis and Prediction. Institute of Ocean Sciences, Patricia Bay, 101pp.

(  0) 0) |

Kang, S. K., Foreman, M. G., Lie, H. J., Lee, J. H., Cherniawsky, J., and Yum, K. D., 2002. Two-layer tidal modeling of the Yellow and East China Seas with application to seasonal variability of the M2 tide. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 107(C3): 6-1. (  0) 0) |

Kang, S. K., Lee, S. R., and Lie, H. J., 1998. Fine grid tidal modeling of the Yellow and East China Seas. Continental Shelf Research, 18(7): 739-772. DOI:10.1016/S0278-4343(98)00014-4 (  0) 0) |

Liu, Z. Y., Wei, H., Lozovatsky, I. D., and Fernando, H. J. S., 2009. Late summer stratification, internal waves, and turbulence in the Yellow Sea. Journal of Marine System, 77(4): 459-472. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2008.11.001 (  0) 0) |

Lozovatsky, I., Lee, J.-H., Fernando, H. J. S., Kang, S. K., and Jinadasa, S. U. P., 2015. Turbulence in the East China Sea: The summertime stratification. Journal of Geophysical Research, 120(3): 1856-1871. DOI:10.1002/2014JC010596 (  0) 0) |

Lozovatsky, I., Liu, Z. Y., Fernando, H., Armengol, J., and Roget, E., 2012. Shallow water tidal currents in close proximity to the seafloor and boundary-induced turbulence. Ocean Dynamics, 62(2): 177-191. DOI:10.1007/s10236-011-0495-3 (  0) 0) |

Munk, W., and Wunsch, C., 1998. Abyssal recipes Ⅱ: Energetics of tidal and wind mixing. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅰ: Oceanographic Research Papers, 45(12): 1977-2010. DOI:10.1016/S0967-0637(98)00070-3 (  0) 0) |

Niwa, Y., and Hibiya, T., 2004. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of M2 internal tides in the East China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research, 109: C04027. (  0) 0) |

Pawlowicz, R., Beardsley, B., and Lentz, S., 2002. Classical tidal harmonic analysis including error estimates in MATLAB using T_TIDE. Computers & Geosciences, 28(8): 929-937. (  0) 0) |

Prandle, D., 1982. The vertical structure of tidal currents. Geophysical & Astrophysical Fluid Dynamics, 22: 29-49. (  0) 0) |

Song, X., Wu, D., and Xie, X., 2019. Tides and turbulent mixing in the north of Taiwan Island. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, 36(3): 313-325. DOI:10.1007/s00376-018-8098-2 (  0) 0) |

Soulsby, R. L., 1983. The bottom boundary layer of shelf seas. In: Physical Oceanography of Coastal and Shelf Seas. Johns, B., ed., Elsevier, New York, 189-266.

(  0) 0) |

Thorpe, S. A., 2007. An Introduction to Ocean Turbulence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 240pp.

(  0) 0) |

Wang, J., Yu, F., Ren, Q., and Wei, C., 2020. Spatial and temporal variability of turbulent mixing in the near-field of the Changjiang River. Journal of Ocean and Limnology, 38: 1138-1152. DOI:10.1007/s00343-020-0008-7 (  0) 0) |

Wang, J., Yu, F., Ren, Q., Si, G., and Wei, C., 2019. The observed variations of the north intrusion of the bottom Taiwan Warm Current Inshore Branch and its response to wind. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 30: 100690. DOI:10.1016/j.rsma.2019.100690 (  0) 0) |

Wang, K., Fang, G., and Feng, S., 1999. A 3-D numerical simulation of M2 tides and tidal currents in the Bohai Sea, the Huanghai Sea and the East China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 21(4): 1-13 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Werner, S. R., Beardsley, R. C., Lentz, S. J., Hebert, D. L., and Oakey, N. S., 2003. Observations and modeling of the tidal bottom boundary layer on the southern flank of Georges Bank. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108(C11): 8005. DOI:10.1029/2001JC001271 (  0) 0) |

Yoshikawa, Y., and Endoh, T., 2015. Estimating the eddy viscosity profile from velocity spirals in the Ekman boundary layer. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 32: 793-804. DOI:10.1175/JTECH-D-14-00090.1 (  0) 0) |

Yoshikawa, Y., Endoh, T., Matsuno, T., Wagawa, T., Tsutsumi, E., Yoshimura, H., et al., 2010. Turbulent bottom Ekman boundary layer measured over a continental shelf. Geophysical Research Letter, 37: L15605. (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22