2) State Key Laboratory of Marine Geology, School of Ocean and Earth Science, Tongji University, Shanghai 200092, China;

3) Qingdao Institute of Marine Geology, China Geological Survey, Qingdao 266237, China

Rare earth elements (REE) serve as crucial geochemical tracers due to their immobility, similar geochemical behaviors, and overall stability in physicochemical properties. Generally, their compositions are controlled by source rocks and remain relatively unaffected during weathering, erosion, transportation, and deposition processes (McLennan, 1989; Chaillou et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2014). Consequently, REEs offer essential insights into sediment provenance and transport processes and find extensive applications in sourceto-sink studies (Bi et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023; Fang et al., 2024). The content and distribution patterns of the REE can reflect the geochemical characteristics and environmental conditions of different sources. By analyzing the REE characteristics in sediment cores, variations in sediment provenance throughout different geological histories can be elucidated.

In response to fluctuations in sea level during the Holocene high sea-level period, marginal seas have gradually formed on the Chinese continental shelf, giving rise to several muddy areas along the eastern Chinese shelf. One such area is the nearshore muddy area of the Shandong Peninsula. Yang and Liu (2007) identified an Ω-shaped distribution of the nearshore muddy area of the eastern Shandong Peninsula, with thickness reaching up to 40 m at local maxima. Numerous studies have employed sedimentology, geochemistry, mineralogy and other methods to trace the provenance of sediment in the nearshore muddy area off the Shandong Peninsula (Dou et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2022). These studies consistently reveal that sediment in the nearshore muddy area primarily originates from the input of material from the Yellow River, with contributions from small to medium-sized rivers influencing sediment composition in the region. Using heavy mineral analysis, Liu et al. (2016b) demonstrated that both the Yellow River-derived sediments and small river inputs along the coast contribute to the sediment provenance in the muddy area. Miao et al. (2018) utilized geochemical methods to conclude that aside from the Yellow River, a small portion of surface sediment in the northeastern Shandong Peninsula originates from river systems that flow directly into the sea. Employing high-resolution seismic profiling and mineralogical methods, Hu et al. (2018) and Ning et al. (2019) have respectively confirmed the contribution of small to medium-sized rivers to the sediment source in the muddy area off eastern Qingdao.

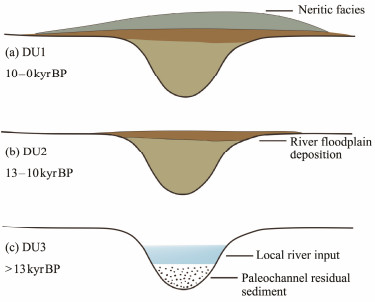

Previous studies, such as those by Liu et al. (2009) on the NYS-101 and NYS-102 core in the northern Shandong Peninsula, Chen et al. (2018) on the DLC70-2 core in the central North Yellow Sea, and Qiu et al. (2014) on the QDZ03 core in the eastern Qingdao, have made significant progress in investigating the late Quaternary stratigraphy and sedimentary environment in the nearshore muddy area of the Shandong Peninsula. Regarding the development of small-scale muddy areas off the southern Weihai, Liu et al. (2016a) integrated seismic stratigraphy, sediment lithology, sedimentary characteristics, AMS14C, and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating data. They then divided core WHZK01 into three sedimentary units, DU1 (0 - 14.91 m), DU2 (14.91 - 17.82 m), and DU3 (17.82 - 25.10 m), representing shallow marine facies, floodplain facies, and fluvial facies deposits, respectively. The sediments in the DU3 and DU2 layers originate from rivers along the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula, while sediments in the DU1 layer consist of fine-grained material transported by coastal currents, mostly from the Yellow River, with contributions from erosion material from coastal rivers and islands (Liu et al., 2018, 2022).

Building upon existing research, the present study utilizes the geochemical analysis of rare earth elements (REE) on the core WHZK01 to more effectively identify the material sources in the small-scale muddy area developed in southern Weihai. This material is chosen because the stable characteristics of REEs provide a reliable means of tracing sediment sources. Through comprehensive comparison with the material end-member characteristics of coastal small to medium-sized rivers and the Yellow River, this study distinguishes the contributions of the Yellow River and various small to medium-sized coastal rivers to different sedimentary units. Furthermore, this work reveals the material sources and sedimentary environment characteristics of the study area since the late Pleistocene, thereby supplementing existing research and enriching the understanding of sedimentary evolution in the small-scale muddy areas of the Shandong Peninsula.

2 Regional SettingsThe study area is located on the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula, in the Jiaodong Peninsula region east of the Jiaolai River. The terrain gradually descends from north to south, with plains distributed in bands along both sides of river valleys and coastal areas. The study area has a meandering coastline, and the southern Yellow Sea has experienced overall regression since the late Pliocene. Several marine transgressions and regressions occurred during the Quaternary, shaping the current geomorphological pattern through continuous marine transgressions until the Holocene (Qiu et al., 2015). Magmatic rocks are widely distributed, but tectonic activity is not highly developed. Below the strata lies the Proterozoic Jiaodong Group metamorphic rock series, with Quaternary deposits covering the entire area, including alluvial, fluvial, residual slope, and marine deposits, among others.

The water systems on the Shandong Peninsula are predominantly composed of mountainous streams flowing directly into the sea. These rivers generally have short lengths and steep gradients, with considerable variations in flow between rainy and dry seasons. Major rivers flowing into the sea in the southern Weihai include the Rushan, Huanglei, Muzhu, and Qinglong Rivers. Among these, the Rushan and Muzhu Rivers are relatively larger rivers compared with the others. The main characteristics of these rivers are summarized in Table 1.

|

|

Table 1 Hydrological characteristics of the main rivers in the south of Shandong Peninsula (modified after Liu et al. (2018)) |

The Shandong Peninsula experiences hot and rainy conditions resulting from the prevalence of southerly winds during the summer, while the winter is characterized by cold and dry weather dominated by northerly winds. The modern circulation system in the Yellow Sea was established after the last high sea level and is significantly influenced by the monsoon climate (Liu et al., 2010). The circulation in the Yellow Sea consists of the Yellow Sea Coastal Current (YSCC) and the Yellow Sea Warm Current (YSWC). The YSCC is a cold-water mass influenced by northerly winds flowing southward, while the YSWC carries warm and saline water along the western side of the Yellow Sea Trough flowing northward (Wang et al., 2022). The basic flow directions of the YSCC and YSWC remain relatively stable throughout the year, with the flow velocities exhibiting patterns of weaker currents in the summer and stronger currents in the winter.

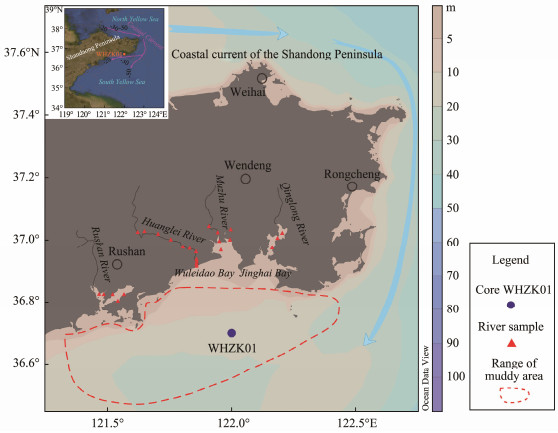

3 Materials and Methods 3.1 SamplingThe core WHZK01 (length: 25.1 m) was collected from the muddy area off the southern Weihai (36˚42΄N, 122˚00΄ E; Fig.1), with a water depth of 15.8 m. Simultaneously, samples were collected from four coastal rivers (Qinglong, Muzhu, Huanglei, and Rushan Rivers) (Fig.1). Most of the samples were taken from fine-grained sediments on the banks, with some samples obtained from riverbed sediments.

|

Fig. 1 Locations of core WHZK01 and river sampling sites (modified from Liu et al., 2022). |

For grain size analysis, 0.1 g of sample was placed into a 10 mL centrifuge tube, followed by the addition of 8 mL of 10% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and 0.1 mol L−1 hydrochloric acid (HCl) to ensure complete reaction and elimination of organic matter and carbonate. Subsequently, 5 mL of 0.5 mol L−1 sodium hexametaphosphate (Na(PO3)6) was added, after which the mixture was thoroughly dispersed by ultrasonic shaking for 10 min. Grain size analysis was conducted using a laser particle size analyzer (Malvern Mastersizer-2000, UK), with a particle size resolution of 0.01 Φ and a measurement range of 0.02 - 2000 μm. The method of Folk and Ward (1957) was used to calculate the grain size parameters.

For the REE analysis, the samples were dried at a temperature of 60℃ and grounded to 200 mesh. The powder samples were digested using a two-step acid digestion method (4 mL HNO3 + 1 mL HClO4, followed by 4 mL HF + 1 mL HClO4) and then extracted with 10 mL of HNO3 and diluted to volume. MnO, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF, Bruker S4 PIONEER, Germany). SC and REE were determined by an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP- MS, Thermo Fisher IRIS Intrepid II XSP, USA). All analyses were conducted at the Marine Geological Laboratory of the Ministry of Natural Resources of China. The analysis quality was monitored using the national geostandard (GBW07315), which revealed that the relative standard deviations of all elements were below 5%.

3.2.2 δEu and δCe calculation methodsδEu and δCe, which reflect the degree of weathering in the source area, are commonly employed for tracing geochemical processes and physiochemical conditions. The calculation methods for δEu and δCe are given respectively as follows (Nesbitt, 1979a):

| $ {\text{δ Eu}} = \frac{{{\text{E}}{{\text{u}}_{\text{N}}}}}{{\sqrt {{\text{S}}{{\text{m}}_{\text{N}}}{\text{G}}{{\text{d}}_{\text{N}}}} }}, $ | (1) |

| $ {\text{δ Ce}} = \frac{{{\text{C}}{{\text{e}}_{\text{N}}}}}{{\sqrt {{\text{L}}{{\text{a}}_{\text{N}}}{\text{P}}{{\text{r}}_{\text{N}}}} }} . $ | (2) |

In the equations, EuN, SmN, GdN, CeN, LaN, and PrN represent the normalized values of chondrite (CN) or the upper continental crust (UCC).

3.2.3 Discriminant function FDThe discriminant function is used to assess the proximity of samples to riverine material. The calculation formula is as follows (Wang et al., 2001):

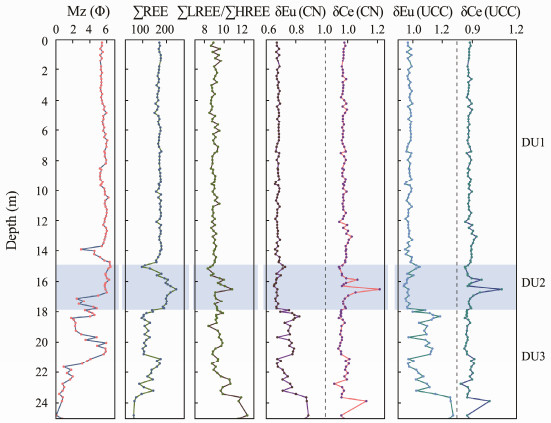

The contents of the 14 REEs of the core WHZK01 sediment are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The vertical variation characteristics are illustrated in Fig.2. The total content of the REEs (ΣREE) in sediment varies significantly, ranging from 61.72 to 241.47 μg g−1, with an average of 156.97 μg g−1. Specifically, the ΣREE content of core WHZK01 is higher than those of the Huanglei River (78.11 μg g−1) and Yellow River (137.76 μg g−1) but lower than that of the Rushan River (208.08 μg g−1), Qinglong River (197.41 μg g−1), and Yangtze River (167.10 μg g−1). The ΣREE is slightly lower than the average ΣREE content of the Muzhu River (164.66 μg g−1) and close to the average ΣREE content of the UCC in eastern China (153.46 μg g−1). Vertically, the ΣREE of layer DU1 remains relatively stable with no significant fluctuation, while the ΣREE of layer DU2 shows a large fluctuation amplitude, increasing to a peak value with increasing depth before gradually decreasing. Layer DU3 exhibits slight fluctuations in ΣREE.

|

|

Table 2 REE compositions of core WHZK01 and surrounding rivers |

|

|

Table 3 Main parameters of core WHZK01 |

|

Fig. 2 Vertical variation curves of the REE-related parameters in core WHZK01. |

The total content of light REEs (LREE: La-Eu) ranges from 57.09 to 220.97 μg g−1, with an average of 141.48 μg g−1. These values indicate relative enrichment, accounting for approximately 90% of the total rare earth content. The total content of heavy REEs (HREE: Gd-Lu) ranges from 4.63 to 21.54 μg g−1, with an average of 15.49 μg g−1, indicating lower abundance, thus accounting for approximately 10% of the total rare earth content. As shown in these findings, the ΣLREE/ΣHREE values exhibit complex and frequent fluctuations.

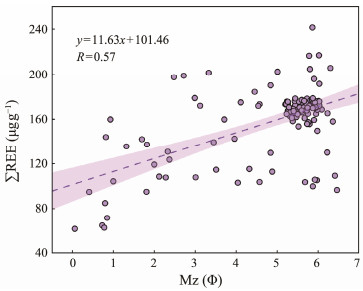

The vertical variations of ΣREE and Mz in the core WHZK01 sediment reveal a consistent trend, with higher ΣREE content observed in layers with finer particles. The correlation analysis between average particle size and ΣREE (Fig.3) shows a moderate correlation (R = 0.57), indicating a positive relationship between ΣREE content and Mz. This implies that finer particles tend to have higher REE content. The enrichment of REE elements generally follows the grain size control rule (Zhao, 1983).

|

Fig. 3 Correlation between average particle size of sediment and ΣREE in core WHZK01. |

δEu reflects the degree of differentiation of sediment. After normalization to chondrite in the core WHZK01 sediment (Table 3), the δEu values range from 0.65 to 0.89, with an average of 0.70, indicating a significant Eu anomaly. Relative to the chondrite, the core sediment has undergone significant differentiation, with a differentiation degree close to that of upper continental crust material in eastern China (δEu = 0.74), thus reflecting the continental nature of the sediment source area. After normalization to the UCC, the δEu values range from 0.94 to 1.27, with an average of 1.01. These values show almost no Eu anomaly, indicating that there has been no significant differentiation relative to the UCC material. Ce anomalies typically occur during rock weathering under weakly acidic conditions and marine sedimentation processes. In the former case, Ce4+ is prone to hydrolysis and precipitation, leading to a low Ce content in the leachate and the occurrence of Ce anomalies (Nesbitt, 1979). In the latter case, Ce3+ is easily oxidized to Ce4+ in seawater and precipitated as CeO2, leading to Ce anomalies in the sediment (Yang and Li, 1999a). The values of δCe (CN) range from 0.91 to 1.22, with an average of 0.98, thus indicating no obvious Ce anomalies. In comparison, the values of δCe (UCC) range from 0.82 to 1.10, with an average of 0.88, indicating a weak Ce anomaly.

5 Discussion 5.1 REE Differentiation PatternThe climate change during the Holocene had a significant impact on the sedimentary environment in the study area. The fluctuation of sea levels has led to various complex physicochemical changes in the sediment during deposition and transport processes, resulting in diverse sources and mixed compositions of the sediment.

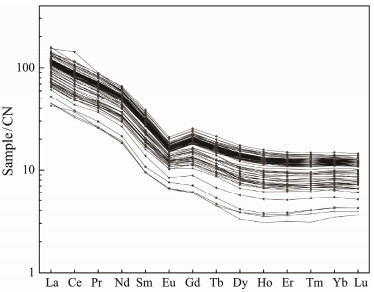

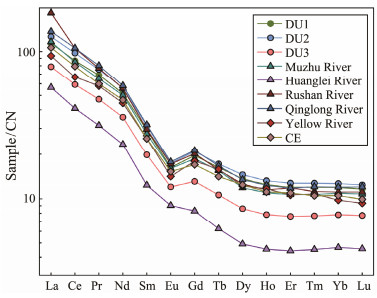

Standardized distribution curves can effectively reflect the geochemical characteristics of the REEs in sediment and can thus be used to infer sediment provenance and reconstruct paleoenvironments. Chondrite is generally considered a primitive material from the early Earth formation, without differentiation. Therefore, REE contents can reflect the degree of differentiation of sediment relative to the original Earth material after chondrite normalization. Previous research has shown that LREEs are more abundant in terrestrial materials than in biogenic and volcanic sources, whereas HREEs are more prevalent in volcanic sources compared to biogenic and terrestrial materials (Liu and Meng, 2004; Li et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2022). Volcanic materials typically exhibit pronounced positive Eu anomalies and relative enrichment in HREE, while biogenic materials tend to be enriched in MREE. Based on the normalized REE distribution patterns of samples shown in Fig.4, the sediment in core WHZK01 exhibits characteristics of LREE enrichment. Therefore, the sediment in the study area predominantly originates from terrestrial sources.

|

Fig. 4 REE differentiation patterns normalized by chondrite for sediments from core WHZK01. |

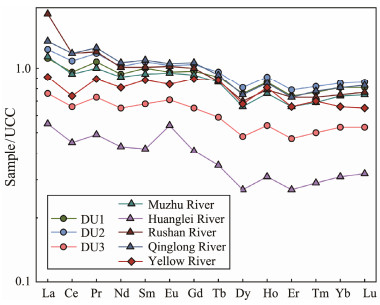

In addition, the morphology of REE distribution curves can also be used to identify sediment provenance. Standardization using the UCC as a reference facilitates the study of the effects of mixing, homogenization, and differentiation of sediment samples during their deposition process. Therefore, in this study, the samples from core WHZK 01 were normalized to CN and UCC standards, with the results shown in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively.

|

Fig. 5 The chondrite-normalized REE curves for sediments from core WHZK01 and related rivers. |

|

Fig. 6 The upper continental crust-normalized REE curves for sediments from core WHZK01 and related rivers. |

While absolute concentrations may vary, sediments from the same source typically exhibit similar patterns in their distribution curves. Therefore, attention should be focused on the geometric shapes of the curves rather than absolute abundances when interpreting the standardized distribution patterns of the REEs in sediments (Yang and Li, 1999a).

The REE chondrite-normalized (CN) distribution curves (Fig.5) reveal that the sediments from the DU1 and DU2 layers of core WHZK01 exhibit remarkably similar distribution curves. In comparison, the distribution curve of the DU3 layer shows slight variations from the other two layers while still maintaining a similar distribution pattern. Notably, all three layers display a right-skewed negative slope pattern. The fractionation degree between LREE and HREE can be measured by the La/Yb (CN) ratio, which is approximately 10 in the sediments from core WHZK01 (Table 3), thus indicating significant LREE and HREE fractionation relative to chondrite.

The fractionation degree among the HREE can be reflected by the Gd/Yb (CN) ratio. In the sediments of core WHZK01, the average Gd/Yb (CN) ratio is 1.65, indicating a weak fractionation degree. The La-Eu curve is steep, while the Eu-Lu curve is flat, showing an overall rightskewed pattern with a 'V' shape at Eu, revealing a moderate negative Eu anomaly. The consistency in the morphology of the distribution curves between the DU1 and DU2 layers of core WHZK01 and sediments from the Muzhu, Qinglong, and Yellow Rivers and the Eastern UCC suggests a potential common source area for these sediments, possibly from the surrounding rivers. However, the differences in the distribution curves among the sediments from DU1, DU2, and DU3 layers also indicate the distinct characteristics associated with different terrestrial sources.

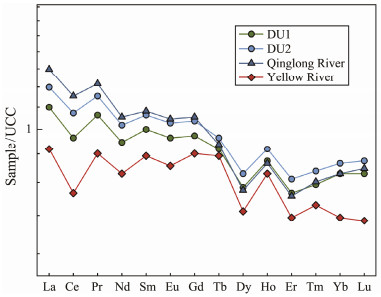

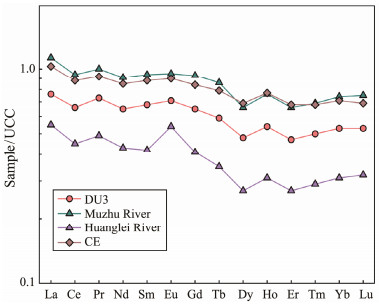

As the UCC-normalized curves exhibit a greater resemblance to the REE contents in terrestrial detrital sediments, they generally provide a more accurate representation of the subtle variations in the REE compositions of sediments. In contrast, the CN curves tend to mask these subtle differences. While the CN curves display similar shapes across different layers, the UCC-normalized curves of core WHZK 01 demonstrate distinct patterns at various layers, characterized primarily by two types (Figs. 7 and 8, respectively).

|

Fig. 7 UCC-normalized distribution curves of the REEs from the DU1 and DU2 layers of core WHZK01 and selected river sediments. |

|

Fig. 8 UCC-normalized distribution curves of the REEs in sediments from the DU3 layer of core WHZK01, along with selected river sediments. |

In Fig.7, the sediments from the DU1 and DU2 layers exhibit a consistent UCC-normalized distribution pattern characterized by negative Ce and Eu anomalies. The average La/Yb (UCC) ratio is 1.38, and the average Gd/Yb (UCC) ratio is 1.21, indicating that there is no significant fractionation between LREE and HREE. The variations in the REE contents along the curves at different layers are relatively large, likely induced by fluctuations in grain size. The UCC-normalized distribution patterns of the REEs in the DU1 and DU2 layers are similar to those of sediments from the Qinglong and Yellow Rivers but show some differences compared with other river sediments.

In Fig.8, the UCC-normalized distribution curve of the sediment from the DU3 layer is presented. This curve exhibits a similar pattern to that observed in sediments from the Muzhu and Huanglei Rivers and the UCC of eastern China. These sediments display a negative Ce anomaly and a positive Eu anomaly. The average La/Yb (UCC) ratio is 1.47, and the average Gd/Yb (UCC) ratio is 1.24, indicating that there is no significant differentiation. However, it is worth noting that the UCC-normalized distribution curves of the REEs from the Rushan River differ from those observed in the DU1, DU2, and DU3 layers.

Overall, there is no significant differentiation observed in the REE composition relative to the UCC in the study area despite the differences in the REE distribution patterns between different layers of core WHZK01 and the surrounding rivers. Therefore, it is inferred that the source area exhibits characteristics of continental crust.

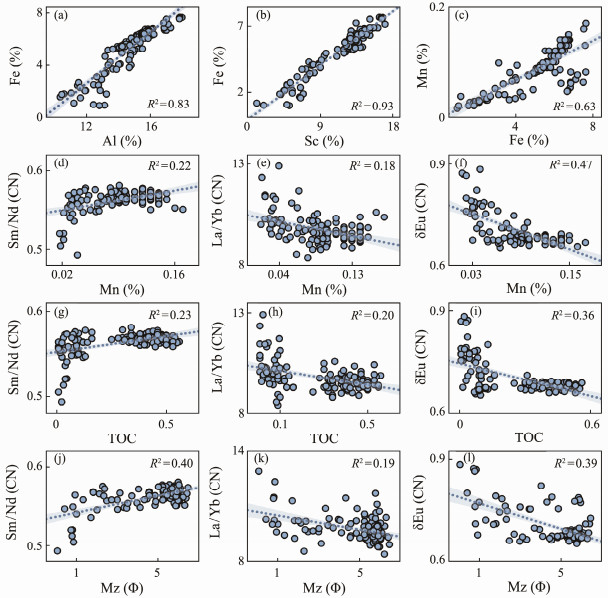

5.2 Investigating the Factors Affecting REE ContentApart from source control and particle size, the presence of organic matter and authigenic Fe-Mn oxides significantly affects REE concentrations (Cullen, 1981; Yang and Li, 1999b; Li et al., 2016). Therefore, it is crucial to consider the potential impacts resulting from these factors before utilizing REE-related parameters for provenance discrimination. Yang et al. (2003) conducted extensive geochemical tracer studies on surface sediment provenance in the South Yellow Sea, concluding that REE fractionation parameters (La/Yb) and some REE ratios can be effectively used to trace and distinguish the material inputs from rivers surrounding the Yellow Sea. Based on previous studies (Yang et al., 2003; Kong et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2014, 2016; Bi et al., 2016), the present paper selects three parameters - Sm/Nd (CN), La/Yb (CN), and δEu (CN) for subsequent provenance discrimination analysis.

Initially, we examined the impact of organic matter on REE concentrations. Generally, sediments with higher organic carbon content have the potential to adsorb more REEs (Meng and Fu, 2006). However, the total organic carbon (TOC) content in the sediment of core WHZK01 is very low, ranging from 0.007% to 0.56%, with an average value of 0.28%. As shown in Fig.9, there is a low correlation between TOC and Sm/Nd (CN), as well as La/Yb (CN), suggesting that organic matter has little impact on the sediment in the study area.

|

Fig. 9 Correlation between Fe, Al, Mn, Sc, Sm/Nd (CN), La/Yb (CN), δEu (CN), TOC, and Mz for the sediments. Sm/Nd (CN) and La/Yb (CN) represent the ratios of Sm to Nd and La to Yb, respectively, after chondrite normalization. |

Previous studies have shown that REE composition can be affected by authigenic Fe-Mn oxides (Tripathy et al., 2014). Fe-Mn oxides, such as deep-sea nodules, have the capacity to accumulate significant amounts of REEs (Elderfield and Greaves, 1982). There are two sources of Fe- Mn oxides: terrigenous and authigenic marine (Wang et al., 2015). As shown in Fig.9, the Fe content in the sediments is highly correlated with typical terrestrial elements, such as Al and Sc (R2 > 0.83), suggesting the terrigenous nature of the Fe in the samples from the study area. The correlation coefficient between Fe and Mn is relatively high (R2 = 0.63), indicating a similarity between Fe and Mn in the sediments. This implies that authigenic Fe-Mn oxides are almost absent in the sediments. Furthermore, the correlation coefficients between Sm/Nd (CN) and Mn, as well as that between La/Yb (CN) and Mn, are very low (R2 < 0.22). Therefore, it can be inferred that the authigenic Fe- Mn oxides could not affect the composition and differentiation characteristics of the REEs in the study area.

Overall, the Sm/Nd (CN) and La/Yb (CN) ratios in the samples are not substantially affected by TOC or Fe-Mn oxides. Thus, these ratios can be effectively used for tracing the sediment sources in the study area.

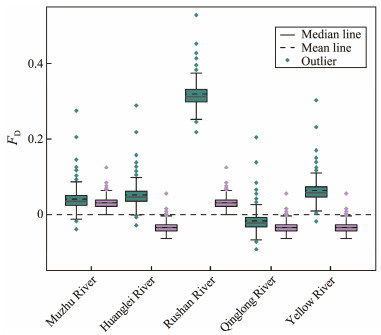

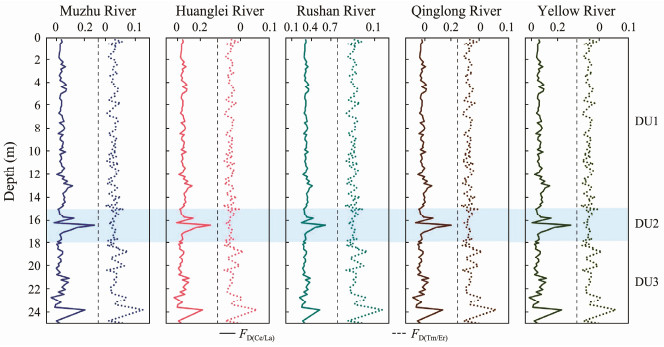

5.3 Identifying Sediment Provenance 5.3.1 Identifying sediment provenance by discriminant functionConsidering the previous analysis, it is evident that both the Yellow River and the small to medium-sized rivers along the coast contribute to the sediment input in the study area. Discriminant function (FD) can be utilized to trace the material sources in the study area. End-member elements should preferably be selected based on their stable geochemical properties while considering the influence of grain size on elemental abundance. In accordance with previous studies (Kong et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2014, 2016; Bi et al., 2016), we selected Ce/La and Tm/Er as contrasting elemental pairs and calculated the values using the Yellow River and the small to medium-sized rivers along the coast as end-members, respectively. The results are presented in Table 4 and Fig.10, while the longitudinal variations are illustrated in Fig.11.

|

|

Table 4 Average values of the discriminant function (FD) calculated for the REEs from core WHZK01 |

|

Fig. 10 Box-plot of the discriminant function (FD) for the REEs from core WHZK01. The green color represents FD(Ce/La), while the purple color represents FD(Tm/Er). |

|

Fig. 11 Vertical variation of the FD values from core WHZK01. |

From Table 4, Figs. 10, and 11, it can be observed that the FD(Ce/La) values are consistently below 0.1 when using the Muzhu, Huanglei, Qinglong, and Yellow Rivers as endmembers, whereas the FD(Ce/La) value is relatively larger at 0.3179 when using the Rushan River as an end-member. This finding indicates that the sediment material in the study area is more similar to that of the other four rivers compared to the Rushan River. Combining this analysis with the distribution patterns from previous figures, we can infer that the sediment in core WHZK01 originates from the material carried by the surrounding small and mediumsized rivers flowing into the sea, as well as material from the Yellow River.

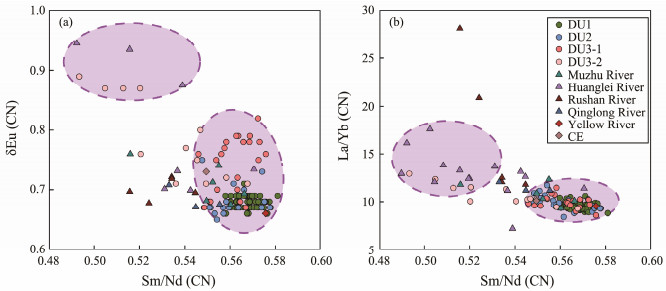

5.3.2 Identifying sediment provenance by end-membersAside from the FD function, the end-member method is also commonly employed for identifying the sources of marine sediments (Liu et al., 2009; Song and Choi, 2009; Lim et al., 2014). To validate and compare the research results, this study employed the Sm/Nd (CN)-δEu (CN) and Sm/Nd (CN)-La/Yb (CN) indices. Source discrimination diagrams were plotted using data from core WHZK01, the Yellow River and nearby small and medium-sized rivers flowing into the sea (Fig.12). From Fig.9, it is observed that δEu is slightly influenced by grain size and exhibits relatively high correlations with Mn and TOC. In contrast, La/Yb (CN) shows lower correlations with Mz, indicating that this parameter is less affected by grain size and better preserves the weathering characteristics of the source area. Therefore, La/Yb (CN) is considered an effective indicator for source discrimination.

|

Fig. 12 Source discrimination of sediments from core WHZK01 and nearby rivers, including the Yellow River. |

From Fig.12, it can be observed that sediments from DU1, DU2, and DU3-1 are projected within the same region as samples from the Qinglong and Yellow Rivers. Furthermore, a significant portion of sediments from the Muzhu River is also projected within this region. Sediments from DU3-2 exhibit elemental ratios projected within the same region as sediments from the Huanglei River.

Combining the FD results, previous patterns observed in the chondrite-normalized diagrams, and UCC-normalized diagrams, we can infer the following: sediments from DU1 and DU2 are significantly influenced by materials from the Qinglong and Yellow Rivers, while sediments from DU3 are mainly influenced by materials from the Huanglei River. Conversely, the influence of sediments from the Rushan River on core WHZK01 is relatively minor. Therefore, the sediment in core WHZK01 results from the combined influence of materials transported by the Yellow Sea Coastal Current, including those from the Yellow River and nearby riverine sources.

5.4 Sources of Materials and Depositional Environment for Different Units of Core WHZK01The DU3 layer (Fig.13c), formed approximately 42 to 22 kyr BP, represents late-stage fluvial deposition during Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS3) (Liu et al., 2018). The sediment source of this layer is mainly derived from local rivers, with a significant influence from the Huanglei River. During the MIS3a period, the climate was warm and humid, with the sea level positioned approximately 35 - 60 m below the current level. Precipitation in the eastern coastal regions of China was generally higher than now. Significant transgressions occurred in the lower reaches of the Haihe River, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Delta. Core WHZK01 is located at a position where it intersects with a coastal mountain stream-type river, experiencing seasonal variations in river flooding and low flow, which drive the formation and evolution of different types of riverbed subfacies. The DU3 layer consists of two parts: the 1) DU3-2 layer, which represents residual sediment of early buried ancient river channels and is characterized by diverse sediment types, including mud, sand, and gravel, and 2) DU3-1 layer, which represents later-stage river fill sediment with slightly finer particles. These layers represent strong hydraulic conditions and relatively uniform sediment source characteristics from the river (Liu et al., 2016a, 2018).

|

Fig. 13 Sedimentary environment evolution profile of core WHZK01. |

The DU2 layer (Fig.13b), formed approximately 13 to 10 kyr BP, represents deposition in the late stage of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). This layer is characterized by river floodplain and estuarine sedimentation (Liu et al., 2016a). The sediment is primarily derived from local rivers, with a significant influence from the Qinglong River and the Yellow River. During the MIS2 period, the global climate cooled, and the sea level dropped to below 120 m of the present sea level. Particularly around 19 kyr BP, during the peak of the LGM, sea levels further declined to between 135 and 150 m below the current level. This resulted in significant exposure of the eastern continental shelf of China. Notably, a pronounced sedimentary hiatus is observed between the DU3 and DU2 layers, indicating prolonged weathering erosion at the location of core WHZK01 between 22 and 13 kyr BP. During this period, the terrestrial sediment at the core site was largely eroded until the onset of the Younger Dryas event (YD) event, when the core site transitioned to a marine-influenced depositional environment.

The DU1 layer (Fig.13a), formed approximately 10 to 0 kyr BP, represents marine-phase deposition during the Holocene (Liu et al., 2016a). The sediment is primarily derived from the Yellow River, with some influence from input by coastal rivers. During the early Holocene, rapid sea-level rise occurred due to the MWP-1C event (9.8 - 9.0 kyr BP) (Liu and Milliman, 2004) and the 8.2 kyr event (8.4 - 8.2 kyr BP) (Alley et al., 1997). During 9.6 - 8.5 kyr BP, the Yellow River was diverted into the South Yellow Sea, and a large amount of material accumulated in the estuary to form a delta, resulting in a serious lack of material supply in the southern Shandong Peninsula, which led to the emergence of an erosion surface at 14.66 - 14.91 m in core WHZK01, resulting in a sedimentary hiatus of 3 kyr. After 8.5 kyr BP, the Yellow River was injected into the Bohai Sea again, the sea level rose rapidly, and the strong tidal power in the North Yellow Sea carried large amounts of Yellow River materials to the north and east of Shandong Peninsula, thus forming a mud area with a large thickness of rapid accumulation, while the material supply in the south of Shandong Peninsula was still lacking. By approximately 6.5 kyr BP, the sea level had risen to its maximum, leading to the formation of the modern circulation pattern in the Yellow Sea (Liu et al., 2004). Coastal currents along the Shandong Peninsula transported large amounts of sediment from the Yellow River to the study area, resulting in significant influence from the Yellow River material on the DU1 layer. Following the maximum marine transgression, the sea level stabilized, and the stable weak depositional environment, coupled with the continued supply of material by coastal currents, facilitated the development of the mud wedge in the southern Weihai region (Liu et al., 2016a).

6 ConclusionsThis study focused on the sedimentary samples from core WHZK01 and aimed to investigate their provenance by analyzing geochemical element data, particularly the characteristic parameters of the REEs. By examining various geochemical indicators, the study reconstructs ancient environments and draws the following understandings and conclusions:

1) Sediments in the study area indicate significant enrichment in LREE. The REEs show clear differentiation compared to chondrite, with a differentiation degree similar to that of the upper crustal material in eastern China. However, there is no significant differentiation in the REEs compared to the upper crustal material, indicating that the sediment has a terrestrial origin.

2) Combining the provenance discrimination diagram, the REE distribution patterns, and the discriminant function (FD), we can infer that the sediments in the DU1 and DU2 layers are mainly influenced by materials from the Qinglong and Yellow Rivers, while sediments in the DU3 layer are primarily influenced by materials from the Huanglei River. The impact of the Rushan River on the study area is less pronounced. Therefore, it can be considered that the sediment in core WHZK01 is the result of the combination of materials carried by the Yellow Sea coastal current from the Yellow River and material inputs from nearby rivers entering the sea.

AcknowledgementsThe corresponding author Jinqing Liu, is deeply grateful to his alma mater, Ocean University of China, and his supervisors, for their steadfast guidance and comprehensive support during his master's and doctoral studies from 2009 to 2016. As the university celebrates its centennial, we extends our heartfelt congratulations and wish it continued prosperity and celebrated achievements. This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2022MD114), and the Project of Global Earth Observation on Asian Delta and Estuary Corresponding to Anthropogenic Impacts and Climate Changes (No. 2019YFE0127200).

Alley, R. B., Mayewski, P. A., Sowers, T., Stuiver, M., Taylor, K. C., and Clark, P. U., 1997. Holocene climatic instability: A prominent, widespread event 8200 yr ago. Geology, 25: 483-486. (  0) 0) |

Bi, D., Zhai, S., Zhang, D., Xiu, C., Liu, X., Liu, X., et al., 2019. Geochemical characteristics of the trace and rare earth elements in reef carbonates from the Xisha Islands (South China Sea): Implications for sediment provenance and paleoenvironment. Journal of Ocean University of China, 18: 1291-1301. DOI:10.1007/s11802-019-3790-0 (  0) 0) |

Bi, S., Kong, X., Zhang, Y., Zhang, X., and Ma, X., 2016. Geochemical characteristics of REEs of shallow sediments in the mud area of southern DingZi Bay and their provenance implications. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 36: 153-162 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Boyton, W., 1984. Geochemistry of the rare Earth elements: Meteorite studies. In: Developments in Geochemistry. Henderson, P., ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 63-114.

(  0) 0) |

Chaillou, G., Anschutz, P., Lavaux, G., and Blanc, G., 2006. Rare earth elements in the modern sediments of the Bay of Biscay (France). Marine Chemistry, 100: 39-52. DOI:10.1016/j.marchem.2005.09.007 (  0) 0) |

Chen, X., Li, R., Lan, X., and Wang, Y., 2018. Stratigraphy of late Quaternary deposits in the mid-western North Yellow Sea. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 36: 2130-2153. DOI:10.1007/s00343-019-7146-9 (  0) 0) |

Cullen, J. L., 1981. Microfossil evidence for changing salinity patterns in the Bay of Bengal over the last 20000 years. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 35: 315-356. DOI:10.1016/0031-0182(81)90101-2 (  0) 0) |

Dou, Y., Li, J., and Yang, S., 2012. Element compositions and provenance implication of surface sediments in offshore areas of the eastern Shandong Peninsula in China. Haiyang Xuebao, 34: 109 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Elderfield, H., and Greaves, M. J., 1982. The rare earth elements in seawater. Nature, 296: 214-219. DOI:10.1038/296214a0 (  0) 0) |

Fang, T., Liu, S., Wu, K., Zhang, H., Cao, P., Huang, M., et al., 2024. Sediment provenance variations driven by sea level in the eastern Arabian Sea since the MIS 9 period: Evidence from geochemical proxies. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 266: 106121. DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2024.106121 (  0) 0) |

Folk, R. L., and Ward, W. C., 1957. A study in the significance of grain-size parameters. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 27: 3-27. DOI:10.1306/74D70646-2B21-11D7-8648000102C1865D (  0) 0) |

Hu, G., Xu, K., Clift, P. D., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Qiu, J., et al., 2018. Textures, provenances and structures of sediment in the inner shelf south of Shandong Peninsula, western South Yellow Sea. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science, 212: 153-163. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2018.07.018 (  0) 0) |

Kong, X., Liu, J., Li, W., Zhang, X., and Liang, Y., 2007. Geochemistry of REE and provenance of surface sediments in the littoral area of the northeastern Shandong Peninsula. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 27: 51-59 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Li, D., Xu, X., Liu, X., Cheng, H., Xu, S., and Jiang, X., 2023. Grain size and geochemistry characteristics of core S01-10 from the central Okinawa Trough since 14 ka: Indications for sediment source and the East Asian winter monsoon. Marine Geology, 460: 107053. DOI:10.1016/j.margeo.2023.107053 (  0) 0) |

Li, J., Liu, S., Feng, X., Sun, X., and Shi, X., 2016. Rare earth element geochemistry of surface sediments in mid-Bengal Bay and implications for provenance. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 36: 41-50 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Lim, D., Jung, H. S., and Choi, J. Y., 2014. REE partitioning in riverine sediments around the Yellow Sea and its importance in shelf sediment provenance. Marine Geology, 357: 12-24. DOI:10.1016/j.margeo.2014.07.002 (  0) 0) |

Liu, J. P., and Milliman, J. D., 2004. Reconsidering melt-water pulses 1A and 1B: Global impacts of rapid sea-level rise. Journal of Ocean University of China, 3: 183-190. DOI:10.1007/s11802-004-0033-8 (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Liu, Y., Yin, P., Gao, F., Cao, K., and Chen, X., 2022. Composition, source and environmental indication of clay minerals in sediments from mud deposits in he southern Weihai offshore, northwestern shelf of the South Yellow Sea, China. Journal of Ocean University of China, 21: 1161-1173. DOI:10.1007/s11802-022-4863-z (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Saito, Y., Kong, X., Wang, H., and Zhao, L., 2009. Geochemical characteristics of sediment as indicators of postglacial environmental changes off the Shandong Peninsula in the Yellow Sea. Continental Shelf Research, 29: 846-855. DOI:10.1016/j.csr.2009.01.002 (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Saito, Y., Kong, X., Wang, H., Xiang, L., Wen, C., et al., 2010. Sedimentary record of environmental evolution off the Yangtze River Estuary, East China Sea, during the last 13000 years, with special reference to the influence of the Yellow River on the Yangtze River Delta during the last 600 years. Quaternary Science Reviews, 29: 2424-2438. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.016 (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Song, H., Yin, P., Zhang, Y., and Cao, Z., 2018. Characteristics of heavy mineral assemblage and its indication of provenance in the mud area off the southern coast of Weihai since the late Pleistocene. Haiyang Xuebao, 40: 129 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Wang, H., Li, S. Q., and Jin, X. M., 2004. Postglacial transgressive sedimentary records of muddy sedimentary areas in the north of the South Yellow Sea. Marine Geology and Quaternary Geology, 24: 1-10 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Yin, P., Chen, X., Cao, Z., Wang, S., Wu, Z., et al., 2016a. Sedimentary environmental evolution of mud area off the southern coast of Weihai since late Pleistocene. Marine Geology and Quaternary Geology, 36: 199-209 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Zhang, Y., Yin, P., Song, H., Bi, S., and Liu, S., 2016b. Distribution and provenance of heavy minerals in surface sediments of the Qingdao offshore area. Marine Geology and Quaternary Geology, 36: 69-78 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Liu, N., and Meng, X., 2004. Characteristics of rare earth elements in surface sediments from the middle Okinawa Trough: Implications for provenance of mixed sediments. Marine Geology and Quaternary Geology, 24: 37-43 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

McLennan, S., 1989. Rare earth elements in sedimentary rocks: Influence of provenance and sedimentary processes. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 21: 169-200. (  0) 0) |

Meng, Y., and Fu, M., 2006. Capacity change of marine sediments with and without organic matter for absorption of rare earth elements. Journal of Tropical Oceanography, 25: 20 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Miao, X. M., Zhu, L. H., Liu, Z. J., Hu, R. J., Jiang, S. H., and Zhang, Z. H., 2018. Distribution pattern and source of trace elements in the surface sediments offshore the northestern Shandong Peninsula. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 48(S1): 82-92 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Nesbitt, H. W., 1979. Mobility and fractionation of rare-earth elements during weathering of a granodiorite. Nature, 279: 206-210. (  0) 0) |

Ning, Z., Han, Z. Z., and Lin, X. H., 2019. Provenance response of detrital minerals from medium and small rivers in offshore southern Shandong Peninsula. Marine Geology Frontiers, 35: 57-68 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Qiu, J., Liu, J., Saito, Y., Yang, Z., Yue, B., Wang, H., et al., 2014. Sedimentary evolution of the Holocene subaqueous clinoform off the southern Shandong Peninsula in the western South Yellow Sea. Journal of Ocean University of China, 13: 747-760. (  0) 0) |

Qiu, J., Zhang, Y., Kong, X., Xu, G., and Wang, S., 2015. Shallow acoustic stratigraphy of late Quaternary in the coastal and offshore areas of southern of Shandong Peninsula. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 35: 1-10 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Song, Y. H., and Choi, M. S., 2009. REE geochemistry of finegrained sediments from major rivers around the Yellow Sea. Chemical Geology, 266: 328-342. (  0) 0) |

Taylor, S. R., and McLennan, S. M., 1985. The continental crust: Its composition and evolution. The Journal of Geology, 94(4): 632-633. (  0) 0) |

Tripathy, G. R., Singh, S. K., and Ramaswamy, V., 2014. Major and trace element geochemistry of Bay of Bengal sediments: Implications to provenances and their controlling factors. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 397: 20-30. (  0) 0) |

Wang, A. M., Wu, X., Bi, N., Ralston, D. K., Wang, C., and Wang, H., 2022. Combined effects of waves and tides on bottom sediment resuspension in the southern Yellow Sea. Marine Geology, 452: 106892. (  0) 0) |

Wang, A. P., Yang, S. Y., and Li, C. X., 2001. Elemental geochemistry of the Nanjing Xiashu loess and the provenance study. Journal of Tongji University, 29: 657-661 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Wang, S., Magalhães, V. H., Pinheiro, L. M., Liu, J., and Yan, W., 2015. Tracing the composition, fluid source and formation conditions of the methane-derived authigenic carbonates in the Gulf of Cadiz with rare earth elements and stable isotopes. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 68: 192-205. (  0) 0) |

Yan, M., Chi, Q., Gu, T., and Wang, C., 1997. Chemical composition of upper crust in eastern China. Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences, 40: 530-539 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang, S. Y., and Li, C. X., 1999a. Research progress in REE tracer for sediment source. Advances in Earth Science, 14: 164 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang, S. Y., and Li, C. X., 1999b. REE geochemistry and tracing application in the Yangtze River and the Yellow River sediments. Geochimica, 28: 374-380 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang, S. Y., Jung, H. S., Lim, D. I., and Li, C. X., 2003. A review on the provenance discrimination of sediments in the Yellow Sea. Earth-Science Reviews, 63: 93-120. (  0) 0) |

Yang, Z. S., and Liu, J. P., 2007. A unique Yellow River-derived distal subaqueous delta in the Yellow Sea. Marine Geology, 240: 169-176. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, X., Bi, S., Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Liu, S., Kong, X., et al., 2016. Provenance analysis of surface sediments in the Holocene mud area of the southern coastal waters off Shandong Peninsula, China. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 35: 124-133. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, X., Han, Z., Ai, L., Liu, J., and Ning, Z., 2018. Characteristics and significance of heavy minerals in the surface sediments of the Holocene mud of the Yellow Sea. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 48: 108-118 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Kong, X., Li, A., Liu, S., Chu, H., et al., 2014. Rare earth elements analysis for provenance study of surface sediments off South Shandong Peninsula. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 34: 57-66 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Y., 1983. Some geochemical patterns of shelf sediments of the China Seas. Chinese Journal of Geology, 18: 307-314 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhu, Y., Bao, R., Zhu, L., Jiang, S., Chen, H., Zhang, L., et al., 2022. Investigating the provenances and transport mechanisms of surface sediments in the offshore muddy area of Shandong Peninsula: Insights from REE analyses. Journal of Marine Systems, 226: 103671. (  0) 0) |

2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23