2) Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China

In recent years, offshore oil and gas exploitation has been transferred to deep- and ultra-deepwater. The increase in the length of traditional steel catenary risers (SCRs) results in a significant increase in the top tension. In addition, severe top floater motions (TFMs) and harsh environmental conditions will lead to high levels of structural stress, dynamic buckling, and serious fatigue damage accumulation at the hang-off point and touchdown zone (TDZ). Thus, traditional SCRs may not be suitable for deepwater oil and gas exploitation (Wu and Huang, 2007; Yang and Li, 2011; Kim et al., 2015).

Accordingly, wave risers (WRs) emerge as the times require, which mainly include lazy wave risers (LWRs) and steep wave risers (SWRs). By installing several buoyancy modules to the middle section of traditional SCRs to form an arc bend section, WRs greatly reduce the tension at the hang-off point. The dynamic response between the top floater and TDZ is decoupled, so the adaptability of the WRs to the TMF is greatly improved. Among WRs, the configuration of SWRs is steeper, the horizontal span is smaller, and the bottom of the riser is almost perpendicular to the seabed, which can effectively avoid the problem of seabed stability. In addition, SWRs are well adapted to situations where the internal flow density changes, so they have significant advantages in deepwater oil and gas production (Bai and Bai, 2014). However, the design and analysis of SWRs face many prominent difficulties, such as complex overall configuration and nonlinear coupling of the internal flow. Moreover, SWRs will have large deformation and rotation angle under harsh environmental conditions, which will produce a significant geometric non-linearity. This condition further increases the difficulty of model establishment and structural dynamic analysis.

Extensive studies have been performed on traditional SCRs and LWRs, including static responses, dynamic behaviors, and pipe-soil interactions (Kirk and Etok, 1979; Fu and Yang, 2010; Yang and Li, 2011; Wang et al., 2012; Elosta et al., 2013; Ruan et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Bai et al., 2015; Kim and Kim, 2015; Wang et al., 2018; Liu and Guo, 2019; Cheng et al., 2020), whereas studies on SWRs are relatively fewer.

Santillan et al. (2010) simplified an SWR into a slender elastic rod and analyzed the static and dynamic responses of the SWR through the finite difference method (FDM). Sun and Qi (2011) conducted a global analysis of an SWR using OrcaFlex and presented a parameter analysis on the dynamic response of SWR under different current velocities and lengths of the buoyancy module. Based on the large deformation beam theory and mechanics equilibrium principle, Qiao et al. (2016) established the motion equations of SWRs and combined the FDM and shooting method to perform a static analysis of SWRs under current. Liu and Guo (2018) established a numerical SWR model with an internal flow based on the slender rod model. In addition, they performed a series of parameter sensitivity analyses on the static and dynamic responses of SWRs.

All the studies reviewed here indicate that the nonlinear dynamic response of SWRs has not been studied in detail and comprehensively. Most of the present studies have ignored the role of internal flows and simplified waves and TFMs to harmonic motion, which is inconsistent with actual ocean conditions. In addition, present studies on the dynamic response of SWRs are extremely lacking. There are few reports on the nonlinear dynamic analysis and fatigue study of SWRs under the combined excitation of internal flows, irregular waves, and TFMs.

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the nonlinear dynamic behavior and fatigue damage of SWRs subjected to irregular waves and TFMs and provide a certain reference significance for the practical engineering applications of SWRs. Considering the internal flow, the governing equations of SWR are established based on the slender rod model. The finite element method (FEM) is applied to discretize governing equations, and the Newton-Raphson and Newmark-β methods are used to solve the nonlinear static and dynamic responses, respectively. Moreover, the Palmgren-Miner rule, a specified S-N curve, and rainflow counting method are applied to estimate the fatigue damage of SWRs.

This paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, the numerical model of SWRs is briefly described. In Section 3, the accuracy of the DRSWR is verified by comparing its results with those of OrcaFlex. In Section 4, the nonlinear dynamic response and fatigue damage of SWRs under the combined excitation of irregular waves and TFMs are presented. A series of sensitivity analyses are performed to investigate the influencing parameters in the fatigue damage of SWRs. Finally, in Section 5, the conclusions are summarized.

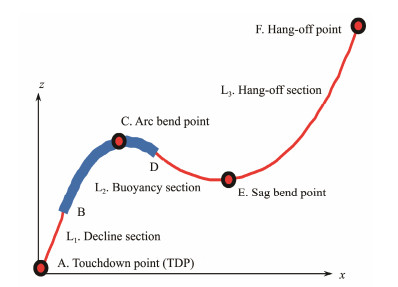

2 Mathematical Models 2.1 SWR ModelA typical SWR model is presented in Fig.1. The riser consists of three parts: decline section A - B, buoyancy section B - C - D, and hang-off section D - E - F. The decline section A - B is suspended in water from the touchdown point (TDP) to the beginning of the buoyancy section, which is almost perpendicular to the seabed near the TDP. The upward buoyancy of the buoyancy section is greater than the downward gravity. Thus, an arc bend is generated, and the peak of the arc bend is called the arc bend point. The hang-off section represents the riser section from the end of the buoyancy section to the hang-off point, which has a sag bend, and the lowest point is called the sag bend point. The hang-off point of the riser is connected with a floater, and the TDP is connected with a subsea base.

|

Fig. 1 Typical configuration of an SWR. |

In recent years, a special elastic rod theory based on absolute coordinates has been widely applied to the numerical simulations of slender flexible structures (Ruan et al., 2014, 2016; Kim and Kim, 2015; Cheng et al., 2020). This theory eliminates the process of converting physical parameters from local coordinates to global coordinates, which is necessary for commercial software (e.g., OrcaFlex and Flexcom 3D), making the numerical model efficient. Thus, based on the slender rod model (Garrett, 1982), i.e., an absolute coordinate approach as mentioned above, the governing equations of SWR are established.

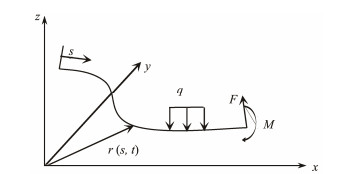

As shown in Fig.2, the centerline of the rod deformed state is represented by the space curve r (s, t), which is a function of the arc length s and time t. Assuming that the arc length of the rod does not change, the internal force state of any point on the rod can be completely represented by the resultant force F and bending moment M. Moreover, the effects of the moment of inertia and shear deformation are ignored. From the conservation of linear and angular momenta, the motion equations of the rod with the internal flow can be obtained (Garrett, 1982).

| $ \boldsymbol{F}^{\prime}+\boldsymbol{q}=\left(\rho+m_{f}\right) \ddot{\boldsymbol{r}} $ | (1) |

| $\boldsymbol{M}^{\prime}+\boldsymbol{r}^{\prime} \times \boldsymbol{F}+\boldsymbol{m}=\bf{0}$ | (2) |

|

Fig. 2 Slender rod model. |

where ρ and mf are the mass of the rod and internal flow per unit length, q is the external force per unit length, and m is the external moment per unit length. According to the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory, M can be expressed as

| $ \boldsymbol{M}=\boldsymbol{r}^{\prime} \times E I \boldsymbol{r}^{\prime \prime}+H \boldsymbol{r}^{\prime} $ | (3) |

where EI is the bending stiffness and H is the section torque. Generally, the effects of the uniform torque and distributed external torque can be ignored for SWRs. Thus, the motion equations of rod can be written as

| $ -\left(E I \boldsymbol{r}^{\prime \prime}\right)^{\prime \prime}+\left(\lambda \boldsymbol{r}^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}+\boldsymbol{q}=\left(\rho+m_{f}\right) \ddot{\boldsymbol{r}},$ | (4) |

where λ = Te - EIκ2 and

Assuming that the SWR is extensible and the elongation is small, the deformation compatibility equation of SWR can be obtained:

| $ \frac{1}{2}(\boldsymbol{r}' \times \boldsymbol{r}' - 1) = \frac{T}{{EA}} \approx \frac{\lambda }{{EA}}, $ | (5) |

where EA is the axial tensile stiffness of the riser.

2.3 Simulations of TFMs and Irregular WavesThe motion analysis of the top floater is directly related to the sea surface motion. The response of the top floater to the significant wave height is generally estimated by the response amplitude operators. In this paper, only the surge effect of the top floater is considered. The motion response of the top floater can be expressed by the motion model recommended by Sexton and Agbezuge (1976):

| $S(t) = {S_0} + {S_L}\sin (\frac{{2{\text{π }}t}}{{{T_L}}} - {\alpha _L}) +\\ \sum\limits_{i = 1}^N {{S_n}\cos ({k_n}S(t) - {\omega _n}t + {\phi _n} + {\alpha _n})} . $ | (6) |

The three terms at the right end of the equation are the mean offset, low-frequency motion, and wave-frequency motion, where S0 is the mean offset; SL is the single amplitude of the vessel drift; TL is the period of the vessel drift; αL is a phase angle between the drift motion and wave, which is usually taken as 0; Sn is the amplitude response of the vessel to a specific wave (period: Tn = 2π/ωn, amplitude: An); and kn, φn, and αn are the wave number, wave phase angle, and phase angle between the TFM response and wave period, respectively.

The JONSWAP spectrum can be used in a wide range and applied to waves at different growth stages. Thus, the JONSWAP spectrum recommended in DNV RP C205 (DNV, 2007) is selected to simulate irregular waves:

| $ {S_J}(\omega) = {A_\gamma } \cdot {S_{PM}}(\omega) \cdot {\gamma ^{\exp \left({ - 0.5{{\left({\frac{{\omega - {\omega _P}}}{{\sigma {\omega _P}}}} \right)}^2}} \right)}}, $ | (7) |

| $ {S_{PM}}(\omega) = \frac{5}{{16}} \cdot {H_S}^2{\omega _P}^4 \cdot {\omega ^{ - 5}}\exp \left({ - \frac{4}{5}{{\left({\frac{\omega }{{{\omega _P}}}} \right)}^{ - 4}}} \right), $ | (8) |

where Aγ = 1 - 0.287lnγ is a normalizing factor, Hs is the significant wave height, ωp = 2π/Tp is the angular spectral peak frequency, Tp is the peak period, and γ is the nondimensional peak shape parameter. For γ=1, the JONSWAP spectrum reduces to the PM spectrum. For the values of γ, the following value can be applied:

| $ \gamma {\text{ = }}\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} 5&{({T_P}/\sqrt {{H_s}} \leqslant 3.6)} \\ {\exp (5.75 - 1.15{{{T_p}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{T_p}} {\sqrt {{H_s}} }}} \right. } {\sqrt {{H_s}} }}){\text{ }}}&{(3.6 < {T_p}/\sqrt {{H_s}} < 5)} \\ 1&{(5 \leqslant {T_p}/\sqrt {{H_s}})} \end{array}} \right.. $ |

The irregular waves and corresponding water particle kinematics are simulated by the Longuet-Higgins model (Borgman, 1969) from their respective spectra.

2.4 Load AnalysisFor an SWR in a marine environment, the external load q can be expressed as follows:

| $ \boldsymbol{q}=\boldsymbol{w}+\boldsymbol{F}^{S}+\boldsymbol{F}^{d}, $ | (9) |

where w is the weight per unit length, Fs and Fd are the hydrostatic and hydrodynamic loads per unit length, respectively.

| $ \boldsymbol{F}^{s}=\boldsymbol{B}+\left(P_{\mathrm{res}} \boldsymbol{r}^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}, $ | (10) |

where B is the buoyancy force per unit length, and the second term at the right end of the equation is the load caused by the pressure difference between the two ends of the riser, where Pres = poAo-piAi is the hydrostatic pressure.

The hydrodynamic force mainly includes the inertial force and drag force, which can be calculated by the Morrison equation:

| $ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{F}^{d}=&-C_{A} \ddot{\boldsymbol{r}}^{n}+\rho_{w} \frac{\pi D^{2}}{4}\left(\dot{\boldsymbol{V}}+C_{a} \dot{\boldsymbol{V}}^{n}\right)+\\ & \frac{1}{2} C_{D} \rho_{w} D\left|\boldsymbol{V}^{n}-\dot{\boldsymbol{r}}^{n}\right|\left(\boldsymbol{V}^{n}-\dot{\boldsymbol{r}}^{n}\right)=-C_{A} \dot{\boldsymbol{r}}^{n}+\overline{\boldsymbol{F}}^{d}, \end{aligned}$ | (11) |

where ρw is the density of seawater, D is the outer diameter of SWR, CA = Ca ρw·πD2/4 is the added mass per unit length, Ca is the added mass coefficient, CD is the drag coefficient,

In this study, the plug flow model is applied for the internal flow. The model assumes that the internal flow is a slender cylinder with the same velocity U at any point in a cross section. The force induced by the internal flow on the riser can be expressed as follows (Païdoussis, 2004):

| $ q(s, t) = - {m_f}\frac{{{D^2}{\boldsymbol{r}}}}{{{D^2}t}} \\ = - {m_f}\left({\frac{{{\partial ^2}{\boldsymbol{r}}}}{{{\partial ^2}t}} + 2U\frac{{{\partial ^2}{\boldsymbol{r}}}}{{\partial s\partial t}} + {U^2}\frac{{{\partial ^2}{\boldsymbol{r}}}}{{\partial {s^2}}}} \right) . $ | (12) |

The right-end terms of the equation are as follows: inertial force, Coriolis force, and centripetal force caused by fluid maintaining the same curvature as the riser.

2.5 Finite Element Model (FEM)The numerical analysis methods of risers mainly include the lumped-mass method (e.g., OrcaFlex), FDM, and FEM. Among them, the FEM is employed in this study given that it is an accessible approach to handle complicated configurations and boundary conditions and has good continuity. Due to the nonlinear governing equations, the equations are expressed in the tensor form for convenience:

| $ - (\rho + {m_f}){\ddot r_i} - (EI{r_i}^{\prime \prime })'' + (\bar \lambda {r_i}^\prime)' + {\bar w_i} + F_i^d = 0, $ | (13) |

| $ \frac{1}{2}({r'_n} \cdot {r'_n} - 1) - \frac{{\bar \lambda - {P_{{\text{res}}}} + {m_f}{U^2}}}{{EA}} = 0. $ | (14) |

The quadratic and cubic Hermit interpolation functions are used for discretization, and then the Galerkin method is used to obtain the differential equations in matrix form for SWRs as follows:

| $ \begin{aligned} &\left(\boldsymbol{M}_{i j l k}+\boldsymbol{M}_{i j l k}^{a}\right) \ddot{\boldsymbol{U}}_{j k}+\boldsymbol{C}_{i j l k}^{f} \dot{\boldsymbol{U}}_{j k}+ \\ &\left(\boldsymbol{K}_{i j l k}^{1}+\overline{\boldsymbol{\lambda}}_{n} \boldsymbol{K}_{n i j l k}^{2}\right) \boldsymbol{U}_{j k}-\boldsymbol{F}_{i l}=0 \end{aligned} $ | (15) |

| $ \boldsymbol{G}_{m}=\boldsymbol{A}_{m i l} \boldsymbol{U}_{k i} \boldsymbol{U}_{k l}-\boldsymbol{B}_{m}-\boldsymbol{C}_{m n} \overline{\boldsymbol{\lambda}}_{n}+\boldsymbol{C}_{m n} \boldsymbol{h}_{n}=0, $ | (16) |

where

| $ \begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{A}_{m i l}=\frac{1}{2} \int_{0}^{L} P_{m} A_{i}^{\prime} A_{l}^{\prime} \mathrm{d} s, \quad \boldsymbol{B}_{m}=\frac{1}{2} \int_{0}^{L} P_{m} \mathrm{~d} s, \\ &\boldsymbol{C}_{m n}=\frac{1}{E A} \int_{0}^{L} P_{m} P_{n} \mathrm{~d} s, \end{aligned}$ |

where Ai, Al, Pm, and Pn are interpolation functions. hn is the pressure difference between the inside and outside of the riser. For 3D problem, i, j = 1, 2, 3 represents the three directions of node motion (i.e., x, y, z). l, k, s, t = 1, 2, 3, 4 are the numbers of the cubic Hermite interpolation functions (Al/k/s/t). m, n = 1, 2, 3, corresponding to the number of the quadratic Hermite interpolation functions (Pm/n).

2.6 Static and Dynamic AnalysesNeglecting the inertial force, Eqs. (16) - (17) constitute the governing equations for the static analysis of risers.

| $\boldsymbol{R}_{i l}=\left(\boldsymbol{K}_{i j l k}^{1}+\boldsymbol{\lambda}_{n} \boldsymbol{K}_{n i j k}^{2}\right) \boldsymbol{U}_{j k}-\boldsymbol{F}_{i l}=0. $ | (17) |

Fil is composed of gravity, drag force caused by current, and other static loads. These nonlinear algebraic equations are solved through the Newton-Raphson method, which is a classical method for solving nonlinear equations.

On the basis of static analysis, the governing equations of dynamic analysis are obtained by considering various dynamic loads. In a dynamic analysis, Fil is composed of static loads and dynamic loads. Taking the equilibrium shape of the riser as the initial condition, the dynamic response of SWRs is solved using the predictor-corrector Newmark-β method.

2.7 Fatigue Damage AnalysisThe stress calculation equation of an SWR can be expressed as follows:

| $ \sigma = \frac{{{T_e}}}{A} + \frac{{ED}}{2}\kappa, $ | (18) |

where Te is the effective tension, A is the cross-sectional area, E is the modulus of elasticity, D is the outer diameter of an SWR, and κ is the curvature.

The stress time history of SWRs is processed through the rainflow counting method (Anzai and Endo, 1979) and the Goodman empirical formula to obtain the equivalent zero-mean stress.

| $ {S_{ij}} = \frac{{{\sigma _b}{S_{ai}}}}{{{\sigma _b} - {S_{mj}}}}, $ | (19) |

where Sij is the equivalent zero-mean stress, Sai is the i-th stress amplitude, Smj is the j-th mean stress, and σb is the ultimate strength.

According to the S-N curve, for a constant stress range, the number of failure stress cycles can be expressed as follows:

| $ \log N = \log a - m\log S, $ | (20) |

where S is the stress amplitude, loga is the interception of the S-N curve in double logarithmic coordinates, m is the slope of the S-N curve in double logarithmic coordinates.

Referring to DNV RP C203 (DNV, 2008), the D curve without cathodic protection in seawater environment is selected in this study: loga = 11.687 and m = 3.

According to the Palmgren-Miner linear cumulative damage theory, the global fatigue damage should meet the following formula:

| $ {D_t} = \sum\limits_i^{} {\frac{{n({S_i})}}{{N({S_i})}}} \leqslant \eta, $ | (21) |

| $ {D_c} = \frac{{60 \times 60 \times 24 \times 365}}{{{T_t}}} \times {D_t}, $ | (22) |

where Dt is the cumulative measure of the fatigue damage during the calculation time, Dc is the cumulative measure of the fatigue damage during a year, n(Si) is the stress cycle counts obtained by the rainflow counting method, N(Si) is the number of fatigue failure cycles determined by the corresponding S-N curve, Si is the stress amplitude of the riser, η = 1/DFF is the usage factor, DFF is the design fatigue factor (according to the DNV RP F204 (DNV, 2005), DFF = 10), and Tt is the calculation time.

Based on the above theory, a calculation program of SWRs was written on MATLAB, which is referred to as 'DRSWR' in this paper.

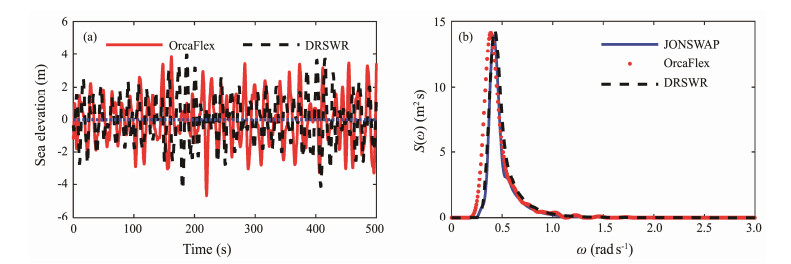

3 Model Validation 3.1 Verification of an Irregular Wave SimulationThe detailed physical parameters of a SWR are shown in Table 1. In this study, the irregular wave parameters proposed by Li et al. (2010) are selected as follows: Hs = 6.5 m and Tp = 12.82 s. The significant wave height Hs and frequency spectrum of irregular waves simulated by the DRSWR are compared with those simulated by OrcaFlex under the conditions of the same parameters, as shown in Fig.3. Fig.3(a) shows that the irregular waves simulated by the DRSWR are basically consistent with those of Orca-Flex in Hs, and the standard deviation between the Hs of OrcaFlex and DRSWR is only approximately 0.08 after the calculation. Fig.3(b) shows the comparison of the JON-SWAP theory spectrum, OrcaFlex simulation spectrum, and DRSWR simulation spectrum. The results of DRSWR and OrcaFlex agree well with each other. Therefore, the accuracy of the wave simulation of the DRSWR can be used for dynamic calculations.

|

Fig. 3 The results of the DRSWR compared with those of OrcaFlex. (a), time history of the wave elevation; (b), irregular wave spectrum. |

|

|

Table 1 Physical parameters of a SWR |

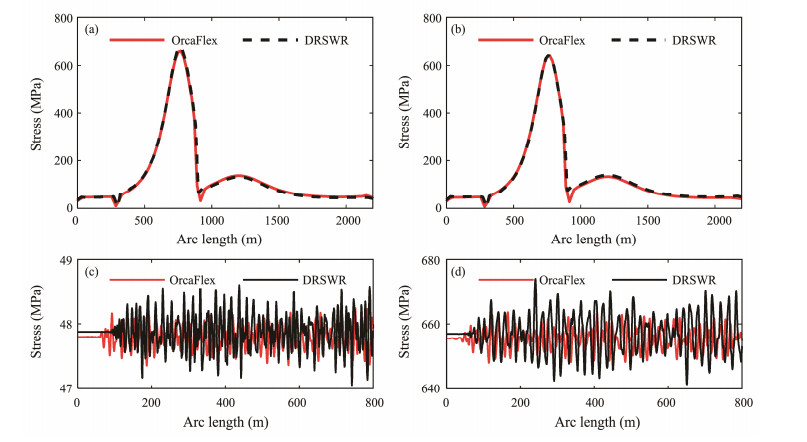

The DRSWR is applied to calculate the stress response of SWRs under an irregular wave. The irregular-wave data are the same as above. The calculation results of the DR-SWR are compared with those of OrcaFlex under the same conditions. As shown in Fig.4, the calculation results of the DRSWR are in good agreement with those of Orca-Flex.

|

Fig. 4 The calculation results of the DRSWR compared with those of OrcaFlex under the same conditions. (a), maximum stress envelope; (b), minimum stress envelope; (c), time history of the stress at 150 m; (d), time history of the stress at 760 m. |

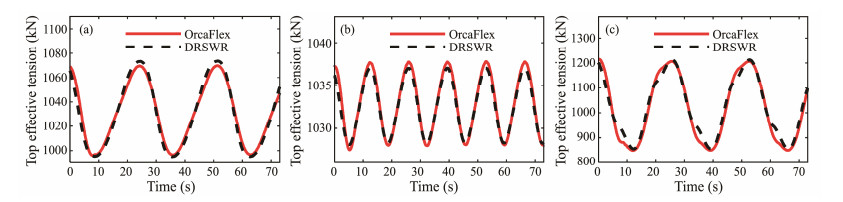

Because the size of the top floater is negligible as compared with the water depth, the TFM is transformed into the dynamic boundary condition of the top node of the SWR. Based on the cases shown in Table 2, the time history of the SWR top tension is calculated by the DRSWR. The calculation results are compared with those of OrcaFlex. As shown in Fig.5, the calculation results are basically consistent.

|

Fig. 5 The calculation results compared with those of OrcaFlex. (a), Case 1; (b), Case 2; (c), Case 3. |

Larsen (1992) presented a description and comparison of the flexible pipe static/dynamic analysis programs. The research results indicated that the calculation results of each program are different to some extent. Moreover, the methods of OrcaFlex and DRSWR are different, so there are some differences in the calculation results, but the difference is completely acceptable. Thus, the accuracy of the DRSWR in calculating the nonlinear dynamic response of SWR under irregular waves and TFMs meets the requirements.

|

|

Table 2 TFM case |

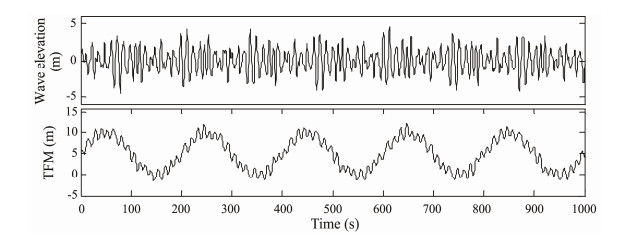

In this section, the dynamic response of SWR under the combined excitation of irregular waves and TFMs is calculated and analyzed. The SWR parameters are shown in Table 1. The basic parameters of the environmental load condition in the analysis are as follows: significant wave height Hs = 6.5 m, peak period Tp = 12.82 s, top floater mean offset S0 = 5 m, single amplitude of the top floater drift SL = 5 m, and period of the top floater drift TL = 200 s (Li et al., 2010). The time history of the irregular wave elevation and TFMs simulated by the DRSWR are presented in Fig.6, where obvious randomness can be observed.

|

Fig. 6 Time history of the wave elevation and TFM. |

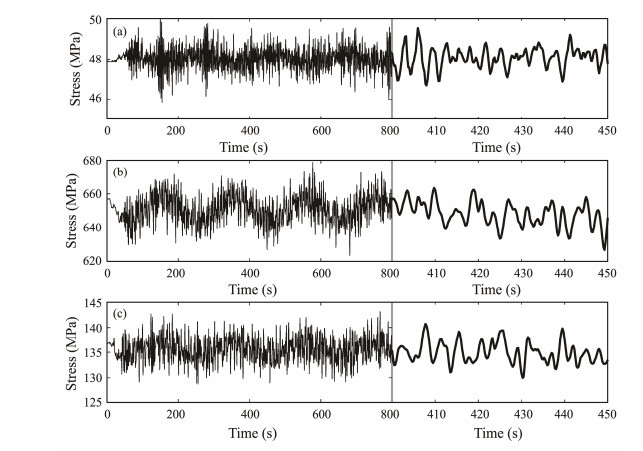

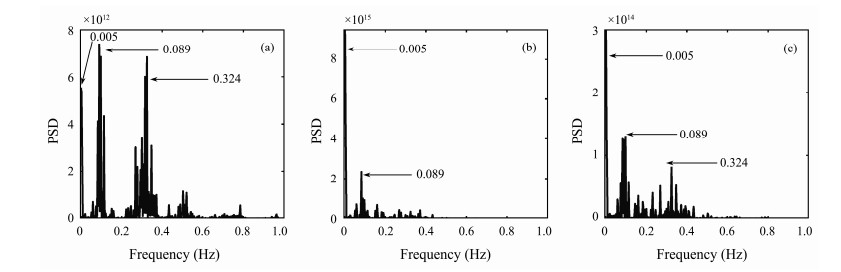

The long-term stress responses of the SWR at locations 150 m (decline section), 760 m (buoyancy section), and 1192.5 m (hang-off section) from the TDP of SWRs and the corresponding power spectra are shown in Figs.7 - 8.

|

Fig. 7 Time history of the SWR stresses at a location of 150 m (a), 760 m (b) and 1192.5 m (c). |

|

Fig. 8 Power spectrum of stress at 150 m (a), 760 m (b) and 1192.5 m (c) of the SWR. |

As can be seen from the fluctuation of the stress time-history curve in Fig.7, the stress variation ranges of the hang-off section and buoyancy section are relatively large, whereas that of the decline section is relatively small. This is mainly because the incident wave velocity decays exponentially along with the water depth and the most violent irregular wave occurs on the surface of the ocean. Moreover, the TFM is directly applied to the hang-off point. Therefore, the stress drastically changes in the hang-off section. Due to the introduction of buoyancy modules, the buoyancy section is subjected to a high hydrodynamic load, which leads to a large range of stress variation in this section. The stress amplitude of the decline section is not evident because the buoyancy section decouples the dynamic response between the TFM and decline section. In addition, the irregular wave has little effect on the decline section. The above results show that SWRs can reduce the stress variation amplitude of the TDP and improve the fatigue life of the TDP.

Fig.7 also shows that the slow drift motion of the top floater has the most significant influence on the dynamic response of the buoyancy section, followed by the hang-off section. This phenomenon disagrees with what we intuitively predicted: the TFM acts directly on the hang-off section but has the most significant effect on the buoyancy section distal to it. A possible explanation for this is that the arched configuration of the buoyancy section is more susceptible to TFM. Moreover, the TFM has the slightest influence on the decline section, which is also due to the decoupling effect of the buoyancy section.

As shown in Fig.8, a multi-frequency response is observed in each section. That is, the slow drift frequency (i.e., 0.005 Hz) and multiple frequencies (i.e., 0.089 Hz and 0.324 Hz) are excited by the irregular waves. As can be seen from the values of the PSD in Fig.8, the decline section mainly vibrates at the wave frequency due to the decoupling effect of the buoyancy section. The vibration frequencies of the hang-off and buoyancy sections are both dominated by the TFM and the wave-induced frequency is less proportional. However, the hang-off section, which is closer to the sea surface, has a higher wave-frequency proportion than the buoyancy section. Based on the above frequency analysis, the influence degree of TFM on each riser section is different. This result is consistent with the analysis indicated in Fig.7. The comparison between the response frequency and SWR natural frequency is further performed. The above response frequencies (i.e., 0.005, 0.089, and 0.324 Hz) are close to the 1st (i.e., 0.0082 Hz)-, 29th (i.e., 0.0875 Hz)-, and 94th (i.e., 0.3224 Hz)-order natural frequencies of the SWR, respectively. That is, the SWR is prone to low-order and high-order resonances under the combined excitation of the TFMs and irregular waves, which further leads to an increase in the range and frequency of the stress variation and consequently to greater fatigue damage.

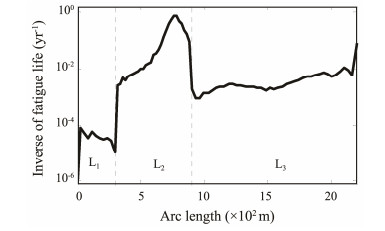

4.2 Fatigue Damage Study on SWRsThe fatigue damage curve of the SWRs under the combined excitation of irregular waves and TFMs is presented in Fig.9. The fatigue damage degree of the SWR is high under the irregular waves and TFMs. Therefore, the fatigue damage analysis has an important reference value to ensure that the SWRs can achieve their expected function.

|

Fig. 9 Fatigue damage of the SWR. |

The greatest fatigue damage occurs in the buoyancy section. According to the above stress analysis, the stress level and variation amplitude of the buoyancy section are higher than those of the other riser sections. This high level of stress cycle leads to serious fatigue damage. The critical points of the fatigue damage of the SWRs are the arc bend point and hang-off point. The stress level of the hang-off point is relatively high, and it is directly affected by the irregular waves and TFMs, so the fatigue damage of this point is great. The above analysis conclusions are consistent with the fatigue damage analysis results of WRs in Li and Nguyen (2010) and Yang and Li (2011).

Particularly, the WRs can reduce the effective tension of the hang-off point and improve the adaptability to the TFM by forming a buoyancy section, but the fatigue damage of the buoyancy section greatly increases. Therefore, some trade-offs should be considered during the design process of SWRs, and some necessary fatigue reduction measures should be applied to the buoyancy section.

4.2.1 Effect of irregular waves1) Sensitivity to the significant wave height Hs

In this study, the environmental parameters in Section 4.1 (i.e., Hs = 6.5 m, Tp = 12.82 s, S0 = 5 m, SL = 5 m, and TL = 200 s) are taken as the basic parameters. In a sensitivity analysis for a specific parameter, only the value of that parameter will be changed, and all the other parameters will be identical to the basic parameter.

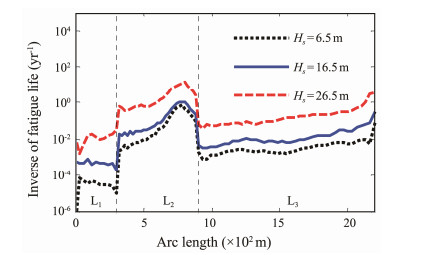

Fig.10 presents the fatigue damage of the SWR for three values of significant wave height Hs = 6.5, 16.5, and 26.5 m at a peak period Tp = 12.82 s, wave incidence angle θ = 0°, and current velocity V = 0 m s-1.

|

Fig. 10 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of Hs. |

Fig.10 shows that the global fatigue damage of the SWR significantly increases with the increase in Hs. For every 10 m increase in Hs, the fatigue damage increases by approximately one order of magnitude. The location of the minimum fatigue life point is mainly near the arc bend point and gradually moves to the hang-off point with the increase in Hs.

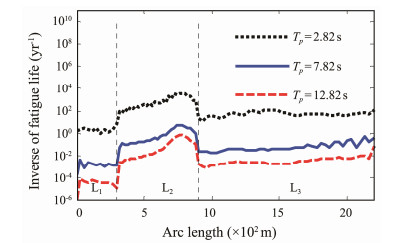

2) Sensitivity to the peak period Tp

Hs = 6.5 m and other parameters are kept constant. The fatigue damage of the SWR with peak period Tp = 2.82, 7.82, and 12.82 s are calculated. The calculation results are shown in Fig.11. The results show that the global fatigue damage of the SWR is highly sensitive to the variation of Tp, and the fatigue damage level greatly decreases with the increase in Tp. For every 5 s increase in Tp, the fatigue damage decreases by approximately 1-3 orders of magnitude. In addition, the fatigue life of the SWR is extremely low at a low Tp, and the minimum fatigue life location is always at a location of 780 m.

|

Fig. 11 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of Tp. |

Based on the parameter analysis of the irregular waves, the irregular wave has a significant impact on the global fatigue damage of the SWR, and the severe wave environment will cause extremely serious fatigue damage to the SWR. Therefore, it is necessary to take wave attenuation measures for the SWR during the in-service period in actual engineering.

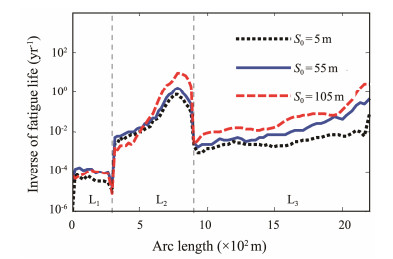

4.2.2 Effect of the TFM1) Sensitivity to the top floater mean offset S0

Fig.12 presents the fatigue damage of the SWR for three different mean offsets S0, i.e., 5, 55, and 105 m. The fatigue damage of the SWR increases with the increase in S0. For every 50 m increase in S0, the fatigue damage increases by approximately one order of magnitude. The fatigue damage of the hang-off section is most easily affected by this parameter, especially near the hang-off point. The main reason is that the stress level of the hang-off section mainly depends on the effective tension level. The increase in S0 leads to a significant increase in the tension of the hang-off section. Accordingly, the stress level of this section rapidly increases and then induces great fatigue damage.

|

Fig. 12 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of S0. |

2) Sensitivity to low-frequency TFMs

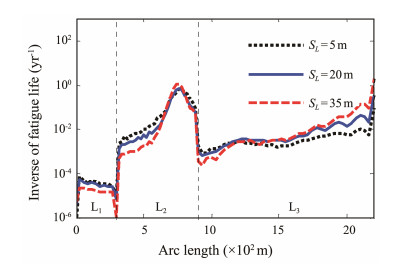

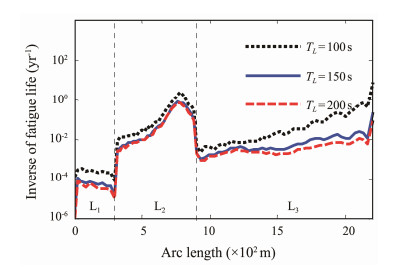

With other parameters unchanged, the fatigue damage of SWRs under different low-frequency TFMs is obtained. The results are shown in Figs.13-14. The three different low-frequency motion amplitudes SL = 5, 20, and 35 m and periods TL = 100, 150, and 200 s are selected. Essentially, the increase in SL and decrease in TL will aggravate the fatigue damage of the SWR. Each 15 m increase in SL or 50 s decrease in TL causes an increase in fatigue damage of approximately one order of magnitude. Moreover, compared with other sections, the hang-off section is more sensitive to low-frequency TFMs. With the increase in SL and decrease in TL, the minimum fatigue location is transferred from the arc bend point to the hang-off point, which is mainly due to the direct contact between the hang-off point and top floater. Accordingly, a high stress cycle and fatigue damage level are induced by the violent TFM.

|

Fig. 13 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of SL. |

|

Fig. 14 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of TL. |

The above parameter analysis results show that TFMs mainly affect the fatigue damage of the hang-off section. Moreover, the sensitivity of the SWRs to the irregular wave variation is much higher than that of the TFMs, which further indicates that the SWRs have excellent adaptability to the TFMs.

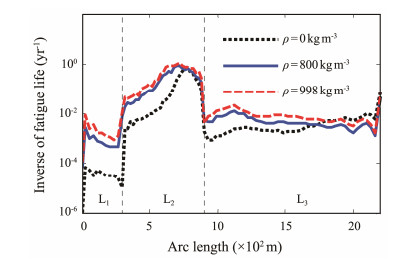

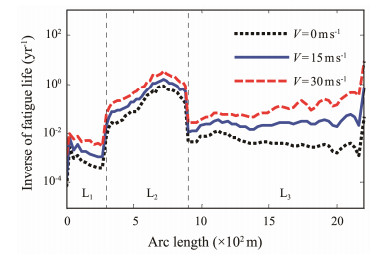

4.2.3 Effect of the internal flowFigs.15 - 16 present the fatigue damage of SWRs for different internal flow velocities and densities. The three different internal flow densities of 0, 800, and 998 kg m-3 and internal flow velocities of 0, 15, and 30 m s-1 at an internal flow density ρ = 800 kg m-3 are selected.

|

Fig. 15 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of the internal flow density. |

|

Fig. 16 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of the internal flow velocity. |

The results show that the fatigue damage of the SWR gradually increases with the increase in the internal flow density and velocity, which is consistent with the analysis conclusions of WR in Yang and Li (2011). For every 15 m s-1 increase in internal flow velocity, the fatigue damage increases by approximately one order of magnitude. The variation of the internal flow density has a significant influence on the fatigue damage near the TDP, arc bend point, and sag bend point. The main reason is that with the variation of the internal flow density, the global configuration of the SWR significantly changes, which leads to a significant change in the curvature of these points. Meanwhile, the variation of the internal flow velocity only has a significant impact on the hang-off point. In addition, the minimum life point of SWRs is always located in the buoyancy section and moves toward the hang-off point with the increase in internal flow density and velocity.

Based on the above analysis of the internal flow, the internal flow has a great impact on the fatigue damage of SWRs, and the internal flow with high density and velocity will cause serious fatigue damage. However, the influence of the internal flow is seldom considered in the current research on SWRs, and corresponding protection measures should be taken according to the internal transport medium of SWRs during the design stage.

As mentioned earlier, the buoyancy section is the fatigue risk region of the SWR, therefore, it is necessary to perform sensitivity analysis on the primary parameters of this section.

4.2.4 Effect of the buoyancy section1) Sensitivity to the buoyancy section length

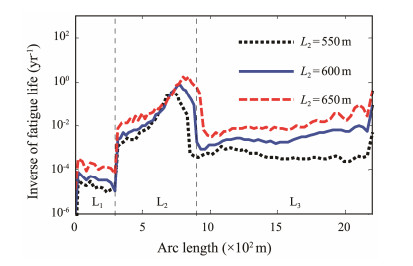

As shown in Fig.17, different SWR buoyancy section lengths are investigated, and the buoyancy section lengths L2 used in the numerical simulation are 550, 600, and 650 m.

|

Fig. 17 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of L2. |

The results show that the fatigue damage of the SWR is relatively sensitive to the variation of L2. The increase in L2 leads to the aggravation of the fatigue damage of the SWR. For every 50 m increase in L2, the fatigue damage increases by approximately one order of magnitude. In addition, with the increase in L2, the minimum fatigue life location is always near the arc bend point and moves toward the hang-off point, which is mainly attributed to the change in the global configuration of the SWR due to the increase in L2, resulting in the arc bend point moving toward the hang-off point.

2) Sensitivity to the buoyancy factor

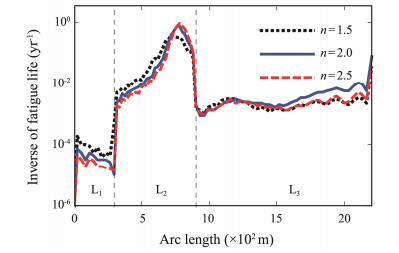

W is defined as the wet weight per unit length of the hang-off section and decline section, and Wf is the wet weight per unit length of the buoyancy section and buoyancy factor n = -Wf/W.

When buoyancy factor n = 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5, the fatigue damage of the SWR is calculated. The results are shown in Fig.18, where the minimum fatigue life of the SWR decreases with the increase in the buoyancy factor. The fatigue damage of the buoyancy section shows a high sensitivity to the variation of the buoyancy factor. The increase in the buoyancy factor will reduce the fatigue life at the arc bend point, mainly because the larger buoyancy factor will lead to the steeper global configuration of the SWR, which means greater curvature and higher bending stress level at the arc bend point. Moreover, with the increase in the buoyancy factor, the minimum fatigue life location is always at the arc bend point.

|

Fig. 18 Fatigue damage of the SWR with the variation of n. |

Although research (Sun and Qi, 2011; Qiao et al., 2016a) has demonstrated that the increase in the buoyancy section length and buoyancy factor can reduce the effective tension of the hang-off point. According to the above parameter analysis, they can, however, also lead to an increase in the SWR fatigue damage. Thus, the two parameters should be designed in detail.

5 ConclusionsBased on the slender rod model and FEM, the nonlinear dynamic analysis model of the SWR is established in this study, which can give full consideration to the geometric nonlinearity and internal flow nonlinear coupling of SWRs. The Newmark-β method is adopted to solve the dynamic behavior. Moreover, the Palmgren-Miner rule, a specified S-N curve, and rainflow counting method are applied to estimate the fatigue damage. Based on these, a calculation process, DRSWR, is programmed with MAT-LAB. In this study, the nonlinear dynamic response and fatigue damage of SWR under the combination of irregular waves, TFMs, and internal flows is calculated and analyzed. Moreover, the effect of irregular waves (significant wave height and peak period), TFMs (top floater mean offset and low-frequency TFM), and buoyancy section (buoyancy section length and buoyancy factor) on the fatigue damage of SWRs are investigated, and the following conclusions are obtained.

1) Under the combination of irregular waves and TFMs, the dynamic response of each section of the SWR exhibits multi-frequency characteristics (i.e., slow drift frequency and multiple frequencies excited by irregular waves). The effect of irregular waves on the sections of SWRs gradually decreases along the water depth. As for TFMs, they act directly on the hang-off section but have the most significant effect on the buoyancy section distal to it.

2) The buoyancy section of SWRs has the highest global stress level, stress variation amplitude, and fatigue damage. The peak point of stress is located at the arc bend point and sag bend point, and the critical points of fatigue damage are mainly concentrated in the arc bend point and hang-off point.

3) The global fatigue damage of SWRs presents a high sensitivity to the variation of the irregular wave, and the increase in the significant wave height and decrease in the peak period increase the global fatigue damage of SWRs. For every 10 m increase in Hs, the fatigue damage increases by approximately one order of magnitude. Moreover, for every 5 s increase in Tp, the fatigue damage decreases by approximately 1-3 orders of magnitude. Thus, severe irregular waves tend to cause severe fatigue damage, and it is essential to take wave attenuation measures at the sea surface in practical engineering.

4) The sensitivity of SWRs to TFMs is significantly lower than that of irregular waves. In addition, the influence of the top floater mean offset on the SWR is greater than that of low-frequency TFMs. The maximum fatigue damage of SWRs increases with the increase in the top floater mean offset. The low-frequency TFM with large amplitude and low period can increase the fatigue damage of SWRs and transfer the critical point from the buoyancy section to the hang-off point. Each 50 m increase in S0, 15 m increase in SL, or 50 s decrease in TL causes an increase in the fatigue damage of approximately one order of magnitude.

5) The internal flow with high density and velocity will produce high-level fatigue damage, and the increase in the internal flow velocity will transfer the minimum fatigue life point from the buoyancy section to the hang-off point. For every 15 m s-1 increase in the internal flow velocity, the fatigue damage increases by approximately one order of magnitude. Therefore, attention should be paid to the internal flow during the SWR service.

6) The increase in the buoyancy section length and buoyancy factor will lead to an increase in the SWR fatigue damage. For every 50 m increase in L2, the fatigue damage increases by approximately one order of magnitude. In addition, the increase in the buoyancy section length will move the minimum fatigue life point toward the hang-off point. In practice, the top tension can be significantly reduced by increasing the two parameters, and the serious fatigue damage they produce should be noted.

AcknowledgementsThe study is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Nos. ZR2019MEE032 and ZR2020ME261), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U2006226 and 51979257), and the Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering (No. kloe202002).

Anzai, H., and Endo, T.. 1979. On-site indication of fatigue damage under complex loading. International Journal of Fatigue, 1(1): 49-57. DOI:10.1016/0142-1123(79)90044-6 (  0) 0) |

Bai, X. L., Huang, W. P., Vaz, M. A., Yang, C., and Duan, M.. 2015. Riser-soil interaction model effects on the dynamic behavior of a steel catenary riser. Marine Structures, 41: 53-76. DOI:10.1016/j.marstruc.2014.12.003 (  0) 0) |

Bai, Y., and Bai, Q., 2014. Subsea Pipelines and Risers. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 401-413.

(  0) 0) |

Borgman, L. E.. 1969. Ocean wave simulation for engineering design. Journal of the Waterways and Harbors Division, 95(4): 557-583. DOI:10.1061/JWHEAU.0000665 (  0) 0) |

Cheng, Y., Tang, L., and Fan, T.. 2020. Dynamic analysis of deepwater steel lazy wave riser with internal flow and seabed interaction using a nonlinear finite element method. Ocean Engineering, 209: 107498. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2020.107498 (  0) 0) |

DNV, 2007. Environmental conditions and environmental loads. Recommended Practice DNV-RP-C205. Det Norske Veritas, 31-37.

(  0) 0) |

DNV, 2005. Riser fatigue. Recommended Practice DNV-RP-F204. Det Norske Veritas, 19-25.

(  0) 0) |

DNV, 2008. Fatigue design of offshore steel structures. Recommended Practice DNV-RP-C203. Det Norske Veritas, 12-17.

(  0) 0) |

Elosta, H., Shan, H., and Incecik, A.. 2013. Dynamic response of steel catenary riser using a seabed interaction under random loads. Ocean Engineering, 69: 34-43. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2013.05.022 (  0) 0) |

Fu, J. J., and Yang, H. Z.. 2010. Fatigue characteristic analysis of deepwater steel catenary risers at the touchdown point. China Ocean Engineering, 24(2): 291-304. (  0) 0) |

Garrett, D. L.. 1982. Dynamic analysis of slender rods. Journal of Energy Resources Technology, 104(4): 302-306. DOI:10.1115/1.3230419 (  0) 0) |

Kim, S., and Kim, M.-H.. 2015. Dynamic behaviors of conventional SCR and lazy-wave SCR for FPSOs in deepwater. Ocean Engineering, 106: 396-414. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2015.06.039 (  0) 0) |

Kim, S., Kim, M. -H., Shim, S., and Im, S., 2015. Structural performance of deepwater lazy-wave steel catenary risers for FPSOs. The Twenty-Fourth International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference. Busan, Korea, ISOPE-I-14-224: 8.

(  0) 0) |

Kirk, C. L., and Etok, E. U.. 1979. Wave induced random oscillations of pipelines during laying. Applied Ocean Research, 1(1): 51-60. DOI:10.1016/0141-1187(79)90008-7 (  0) 0) |

Larsen, C. M.. 1992. Flexible riser analysis - Comparison of results from computer programs. Marine Structures, 5(2-3): 103-119. DOI:10.1016/0951-8339(92)90024-J (  0) 0) |

Li, S. C., and Nguyen, C., 2010. Dynamic response of deepwater lazy-wave catenary riser. Proceedings of Deep Offshore Technology International. Amsterdam, Netherlands. 页码?

(  0) 0) |

Li, X. M., Guo, H. Y., and Meng, F. S.. 2010. Stress analysis of top tensioned riser under random waves and vessel motions. Journal of Ocean University of China, 9(3): 251-256. DOI:10.1007/s11802-010-1719-8 (  0) 0) |

Liu, Z., and Guo, H. Y.. 2018. Sensitivity analysis of steep wave riser with internal flow. Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 26(4): 541-551. (  0) 0) |

Liu, Z., and Guo, H. Y.. 2019. Dynamic response study of steel catenary riser based on slender rod model. China Ocean Engineering, 33(1): 57-64. DOI:10.1007/s13344-019-0006-8 (  0) 0) |

Païdoussis, M., 2004. Fluid-Structure Interactions: Slender Structures and Axial Flow (Vol. 2). Academic Press, California, 196-276.

(  0) 0) |

Qiao, H. D., Ruan, W. D., Shang, Z. H., and Bai, Y., 2016. Non-linear static analysis of 2D steep wave riser under current load. ASME 2016 35th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering. Busan, Korea, OMAE2016-54460, V005T04A052, 9pp.

(  0) 0) |

Ruan, W. D., Bai, Y., and Cheng, P.. 2014. Static analysis of deepwater lazy-wave umbilical on elastic seabed. Ocean Engineering, 91: 73-83. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2014.08.017 (  0) 0) |

Ruan, W. D., Liu, S. H., Li, Y. Y., Bai, Y., and Yuan, S., 2016. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of deepwater steel lazy wave riser subjected to imposed top-end excitations. International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering. Busan, Korea, OMAE2016-54111, V005T04A046, 8pp.

(  0) 0) |

Santillan, S. T., Virgin, L. N., and Plaut, R. H.. 2010. Static and dynamic behavior of highly deformed risers and pipelines. Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, 132(2): 021401. DOI:10.1115/1.4000555 (  0) 0) |

Sexton, R. M., and Agbezuge, L. K., 1976. Random wave and vessel motion effects on drilling riser dynamics. Offshore Technology Conference. Houston, Texas, OTC-2650-MS.

(  0) 0) |

Sun, L. P., and Qi, B.. 2011. Global analysis of a flexible riser. Journal of Marine Science Application, 10(4): 478-484. DOI:10.1007/s11804-011-1094-x (  0) 0) |

Wang, J. L., Duan, M. L., and He, R. Y.. 2018. A nonlinear dynamic model for 2D deepwater steel lazy-wave riser subjected to top-end imposed excitations. Ships and Offshore Structures, 13(3): 330-342. DOI:10.1080/17445302.2017.1382663 (  0) 0) |

Wang, J. L., Duan, M. L., He, T., and Jing, C.. 2014. Numerical solutions for nonlinear large deformation behaviour of deepwater steel lazy-wave riser. Ships and Offshore Structures, 9(6): 655-668. DOI:10.1080/17445302.2013.868622 (  0) 0) |

Wang, L. Z., Yuan, F., Guo, Z., and Li, L. L.. 2012. Analytical prediction of pipeline behaviors in J-lay on plastic seabed. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, Ocean Engineering, 138(2): 77-85. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)WW.1943-5460.0000109 (  0) 0) |

Wu, M., and Huang, K., 2007. The comparison of various SCR configurations for bow turret moored FPSO in West Africa. The Seventeenth International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference. Lisbon, Portugal, ISOPE-I-07-054.

(  0) 0) |

Yang, H. Z., and Li, H. J.. 2011. Sensitivity analysis of fatigue life prediction for deepwater steel lazy wave catenary risers. Science China Technological Sciences, 54(7): 1881-1887. DOI:10.1007/s11431-011-4424-y (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21