2) Faculty of Science, Alexandria University, Moharam Bey 21511, Egypt

Dinoflagellates are important primary producers, together with diatoms and coccolithophorids, they constitute a major part of the marine eukaryotic phytoplankton. Many dinoflagellate species have a non-motile stage during their life cycle and following sexual reproduction, during which the cell is protected within a calcareous or organicwalled cyst. Dinoflagellate cysts have a high preservation potential and can rest in/on the sediments for decades (Belmonte et al., 1995). About half of all dinoflagellate taxa are phototrophic, acquiring energy by photosynthesis. Phototrophic dinoflagellates take advantage of ocean environments with low nutrient levels, whereas heterotrophic dinoflagellates depend on food availability (e.g., Taylor and Pollingher, 1987; Gaines and Elbraechter, 1987). Heterotrophic cysts are usually very abundant in high productivity zones (de Vernal and Marret, 2007) and are therefore used to indicate trends in productivity. However, they are also the most sensitive to oxygenation (Zonneveld et al., 2001; Versteegh and Zonneveld, 2002). Dinocysts are sensitive recorders of environmental conditions of the surface waters, therefore their fossil assemblages, concentrations and accumulation rates in marine sediments can be successfully employed to reconstruct palaeoenvironmental surface water conditions, providing information on nutrient availability, productivity, temperature, salinity, stratification, and oxygenation (e.g., Dale, 1996; de Vernal, 2007; Zonneveld et al., 2008, 2012).

Benthic foraminifera are the most abundant, diverse and widely spread invertebrates in all marine environments. They are durable as their tests are known to exhibit a high fossilization potential, and they are easily collected and separated from sediment samples (Murray, 1991). Therefore they are good ecosystem monitors. There is comprehensive information on their ecology from different marine environments, which provide many valuable clues to their ecosystems. Several studies confirmed that benthic foraminifera is affected by environmental variation particularly productivity, bottom water oxygenation, thermo-haline structure of the water body and its bottomwater circulation (e.g., Mackensen et al., 1994; Schmiedl et al., 1998; Bickert and Wefer 1999; Badawi, 2015).

In the present study, dinoflagellate cyst assemblages and foraminiferal analyses are used to interpret paleoenvironmental and paleohydrographic changes of the Holocene in marine core offshore Egypt corresponds to 101.5 km from Damietta Harbor, southeastern Mediterranean Sea. Up to now, little micropalaentological studies have been done in the study area (e.g., Kholeif, 2008; Kholeif and Mudie, 2009; Kholeif and Ibrahim, 2010; Mojtahid et al., 2015). In these previous studies, they used dinoflagellate cysts, pollen or foraminifera as palaeoenvironmental proxies. In the current study, the combination of two integrative complementary proxies (dinoflagellate and foraminiferal assemblages) reflects more comprehensive paleoenvironmental view.

2 Study AreaThe Mediterranean Sea is one of the most oligotrophic seas in the world (Yacobi et al., 1995). It is 4000 km long, 1000 km wide and 1500 m deep (Candela, 1991). It is a landlocked marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean and it is divided by the Strait of Sicily into two main sub basins; the Western and Eastern Mediterranean. Surface waters of both the Western and Eastern Mediterranean Sea are mainly oligotrophic, leading to low bioproductivity which is distincted by low chlorophyll-a concentrations (Psarra et al., 2000; Krom et al., 2003). Although, there is a notable west-east trophic gradient with surface waters becoming increasingly oligotrophic in an eastward direction (Turley et al., 2000; Psarra et al., 2005).

The most important river that passes through the north Africa and discharge in the eastern Mediterranean Sea is the Nile River that is the one of most distinguishing features of the eastern Mediterranean. It has a large drainage basin, and linking several different climatic zones (Foucault and Stanley, 1989; Williams et al., 2000). Although the Nile has the largest catchment area of all rivers entering the Mediterranean Sea, the Aswan High Dam construction in 1964 lead to a major reduction in discharge. The Nile floods and enhanced rainfall over the eastern Mediterranean basin reinforce productivity and increase the stratification of the water column and organic matter preservation. This natural process resulted in sapropel formation (Rohling, 1994; Cramp and O'Sullivan, 1999). The sapropels are episodic dark-colored, organic carbon-rich sediments that are unique and reoccurring features of the Quaternary sediment record of the Mediterranean Sea. The eastern Mediterranean Holocene Sapropel (S1) event extended for a period spanning the 6270–9500 years Before Present (yr BP). The sapropel layers and flood intervals that supposedly led to their formation have often been correlated with climate cycles and periodic African monsoon intensification (Rossignol-Strick, 1985; Gasse, 2000; Scrivner et al., 2004).

3 Material and Methods 3.1 Sampling and Sediment AnalysisThe current study is based on multi-core (core st#786) sediment samples from the Eastern Mediterranean Sea were taken during METEOR cruise M70b in October 2006. The studied Eastern Mediterranean core (core st#786) is about 46 cm long and was taken at a depth of 1130 m. The location of the core is 32˚22x6.84xxN, 31˚42x21.3xxE (Fig. 1). Sediment grain size analysis was performed by sieve and pipette methods according to Sweet et al. (1998). Organic carbon was determined by using acid/dichromate titration method as described by Gaudette et al. (1974).

|

Fig. 1 The location of the studied core in the southeastern Mediterranean Sea. |

The age of the studied core is compared and correlated with the dated core NC core 2 according to Kholeif and Mudie (2009); since the both cores are located nearly in the same area. Their core is located at 32˚20x42xxN, 31˚39x0xxE. It is 170 cm long and was taken at depth 1030 m (Kholeif and Mudie, 2009). Sedimentation rate of their core is relatively uniform around 14 cm Kyr−1, but decrease at the top of the core. They recorded AMS shell age of 6270 ±40 yr BP at the top 30–45 cm. Sapropel S1 has been dated in previous studies of southeastern Mediterranean cores around 9500-6000 yr BP (Murat and Got, 2000). This age is comparable with the data of the well-dated core of Stanley and Maldonado (1977) from the same area and similar water depth (1026 m), northeast of the Damietta Branch of the Nile Delta. Kholeif and Ibrahim (2010) has adopted this age model as well. When comparing this age model with neighboring inland delta lake age model, we found that the inland lake has somehow different sedimentation rate. For example, it ranges between 0.08–0.37 cm yr−1 during the last 7000 year in Burullus Lagoon (Bernhardt et al., 2012).

3.2 Palynological Analysis 3.2.1 Dinoflagellate cyst analysisTwelve samples were prepared, covering 0–46 cm in the core st#786. The samples were separated by 2 cm intervals. The samples were dried at 60℃ for 24 h, weighed and they were processed using standard technique. Cold 10% HCl was added to remove carbonates, followed by neutralization of the sample by KOH 10%. The material was treated with 40% cold HF, to remove silicates and agitated for 2 h. It was left in HF for an additional two days without agitation. After HF treatment, the material was neutralized by the addition of KOH 40%. The neutral material was homogenized (i.e., shaken for 2 min), sonified for l–2 min to disaggregate, and sieved over a 20 mm stainless steel sieve to retain the 20 mm fraction. Each residue was centrifuged in a glass tube (8 min, 3300 rpm) and transferred to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. After second centrifuging (6 min, 3300 rmin−1), the material was concentrated to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. A 50 mL of the homogenized sample residue was put on a slide with an Eppendorf automatic micropipette. The material was embedded in glycerin jelly and insulated from air by paraffin wax. A minimal amount of 100 cysts per slide have been counted when possible. Three slides of each sample were examined using Zeiss research microscope at a magnification of 40 x. The taxonomy according to Zonneveld and Pospelova (2015) was adopted. Brigantedinium spp. includes all smooth-walled spherical brown cysts. The relative abundances of dinocysts species are calculated and plotted.

3.2.2 Foraminiferal analysisFor micropaleontological (foraminiferal) analysis samples were soaked, washed with tap water over a 63 µm sieve, and were dried at 60℃. Total assemblages were determined in fractions of spilt samples including at least 300 specimens. Stereomicroscope was used to examine and identify the planktic and benthic foraminifera, whereas scanning electron microscope was used to photograph represented species. Foraminiferal species are identified according to Loeblich and Tappan (1987). Two foraminiferal parameters are calculated to identify changes in species diversity by using: Fisher alpha index (α) (Fisher et al., 1943; α = n1/x, where N is the number of individuals, x is constant having a value < 1 and n1 can be calculated from N (1−x)), and Shannon index (H) (Shannon, 1948; H = −pi ln pi, where pi is the proportion of each species). In the current study, sinistral and dextral coiling of Globigerinoides ruber was used to determine the cold and warm periods throughout the studied core sediments

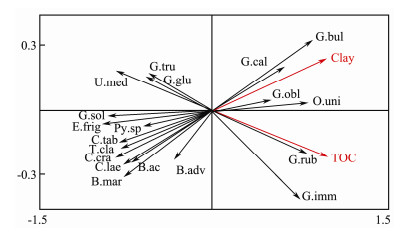

Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) was carried out to determine whether species manifest a unimodal or linear response to an environmental gradient (Leps and Smilauer, 2005; Leyer and Wesche, 2007). The short gradient length of the first axis (1.71 SD) suggests the usage of linear response model for the species. Redundancy Analysis (RDA) was performed for species-environment relationships analyses in the second step to asses and quantify the relationship between the distribution of species and ecological parameters such as TOC% and clay content using the software package Canoco version 4.5a (Ter-Braak and Smilauer, 2002; Leps and Smilauer, 2005).

4 Results 4.1 Granulometric ParametersSediment of core st#786 has mud to clayey texture trend, the highest value of clay 97.5% is recorded at 40-42 cm but the lowest one is 52% recorded at 12-14 cm. There is a marked increase of clay content recorded in the lower part of the core (Table 1, Fig. 2). In core st#786, the highest TOCx% is recorded at 40-42 cm (2%), while the lowest value is recorded at 0-2 cm (0.2%). The highest TOCx% values through the core are recorded at the lower part of the core which are parallel with the highest clay content (Table 1, Fig. 2).

|

|

Table 1 Percentage of TOC%, sand, silt and clay in core st#786 |

|

Fig. 2 Relative abundances of the main dinocysts, TOC% and clay content versus core depth throughout the investigated core st#786. |

Cyst diversity is low in the core, with only 15 identified dinocyst species. These species are listed in table 2. The counts of Dinoflagellate cysts are found to be low, the total count of dinoflagellate cyst in core st#786 vary by an order of magnitude from 487 cyst at depth 4-6 cm to 2939 cyst at depth 40-42 cm (Appendix 1). The maximum of the total count of dinoflagellate cysts is recognized in the lower part of the core. Dinoflagellate cyst assemblages are dominated by autotrophic dinoflagellates mainly Impagidinium aculeatum that may form up to 23.2% of the assemblage. Other species that occur in high percentage are Spiniferites spp. (15.8%) and Brigantedinium spp. (18.4%). The later species exceeds Impagidinium spp. in sapropel layer (about 24%). The majority of cyst types belonging to the order Gonyaulacales. Cysts of heterotrophic dinoflagellates, most of the protoperidinioids form less than 5% of the total assemblage of the post-sapropel deposition. Within the sapropel, protoperidinioids are relatively more abundant than other species and represent up to 24% of the assemblage (Fig. 2).

|

|

Table 2 List of dinocyst taxa, benthic and planktic foraminiferal species recorded in core st#786 |

The association of dinoflagellate cyst shows two depositional phases in the sediment. The first phase is the sapropel layer (organic rich and oxygen depleted sediments), which represents the depth between 28-46 cm. The second phase is the post-sapropelic layer (the upper oxidized low organic sediments), which represents the depth between 0-28 cm. The first phase (sapropel layer S1) is characterized by a distinct increase in the relative abundance of Brigantedinium spp., Echinidinium aculeatum, Echinidinium delicatum, Echinidinium granulatum (Fig. 2). Autotrophic dinoflagellates species dominates the organic walled cyst association in the second postsapropel sediment layer such as: Operculodinum iseralianium, Operculodinum spp., Polysphaeridium zoharyi and Impagidinium species specially I. patulum. Nematosphaeropsis labyrinthus, Operculodinum centrocarpum and Spiniferites spp. are shown in both sediments of the two phases. Percentages of heterotrophic species as different Echinidinium species and Brigantedinium spp. show a sharp decrease and even barren at the upper oxidized sediments (Fig. 2). Lingulodinium machaerophorum, autotrophic dinoflagellates species, has higher relative abundance in sapropel layer compared to post-sapropelic layer. Peak of the dinocysts Bitectatodinium tepikiense is recorded at the beginning of the sapropel; since it reaches to 3% of the total dinocyst assocciations (Fig. 2).

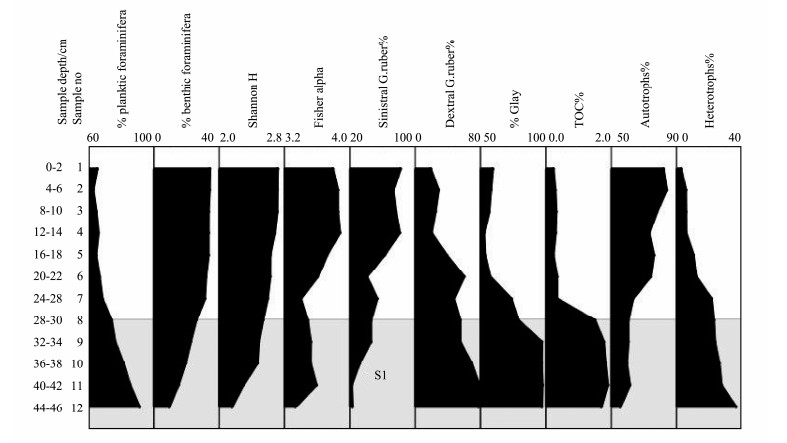

4.3 Planktic and Benthic Foraminiferal AssociationsNineteen Foraminiferal species have been identified in the present study. Ten species belonging to benthic foraminifera and 9 species to planktic one (Figs. 3-5). The identified planktic and benthic foraminiferal species are listed alphabetically in Table 2. The foraminiferal assemblage of planktic and benthic foraminifera has moderate density throughout the investigated core. At core st#786, the standing foraminiferal assemblage is ranging from 870 individual per 10 g sediment at 0-2 cm to 600 individual per 10 gram sediment at 44-46 cm. Nearly all benthic foraminiferal species have high relative abundance in the upper part of the core, while they decrease significantly in sapropel layer (Fig. 6). Most planktic foraminiferal species have high relative abundance in the lower part of the core (S1) especially Orbulina universa, Globigerina bulloides, Globigerina calida, Globigerinoides ruber and Globigerinoides immaturus (Fig. 7). In contrast, Turborotalia clarkei, Globorotalia truncitulinoides, and Globigerinita glutinata show high relative abundances in the upper part of the core, while Globigerinoides obliquus shows variable abundances through the core. The percentage of sinistral coiling of Globigerinoides ruber decreases sharply in sapropel layer S1 (Fig. 7). Shannon diversity index (H) for core st#786 ranges from 2.148 at depth 44-46 cm to 2.718 at depth 0-2 cm (Figs. 6-7). Fisher alpha index for core st#786 has values range from 3.320 at depth 46-44 cm to 3.792 at 0-2 cm. Both diversity indices decrease in sapropel layer S1 (Figs. 6-7).

|

Fig. 3 SEM photomicrograph of some selected benthic foraminifera. 1, Bolivina acuminate (Natland, 1946); 2, Bolivina advena (Cushman, 1925); 3, Bulimina marginata (d'Orbigny, 1826); 4-5, Cassidulina crassa (d'Orbigny, 1839); 6, Cassidulina laevigata (d'Orbigny, 1826); 7-8, Cibicides tabaensis (Perelis and Reiss, 1975); 9-10, Gyroidina soldanii (d'Orbigny, 1826); 11-12, Uvigerina mediterranea (Hofker, 1932). |

|

Fig. 4 SEM photomicrograph of some selected planktic foraminifera. 1-2, Globigerina bulloides (d'orbigny, 1826); 3-4, Globigerinoides calida (Parker, 1962); 5, Globigerinita glutinata (Egger, 1895); 6-7, Globigerinoides immature (Le Roy, 1939); 8, Globigerinoides obliquus (Bolli, 1957); 9-10, Globigerinoides ruber (d'Orbigny, 1839); 11, Globorotalia truncitulinoides (d'Orbigny, 1839); 12, Orbulina universa (d'Orbigny, 1839); 13-14, Turborotalia clarkei (Rogl and Bolli, 1973). |

|

Fig. 5 SEM photomicrograph of sinistral and dextral of Globigerinoides ruber (d'Orbigny, 1839). |

|

Fig. 6 Relative abundance of benthic foraminifera, diversity indices, TOC%, clay content and sapropel layer S1 (shaded patterns) in the investigated samples of core st#786. |

|

Fig. 7 Relative abundance of planktic foraminifera, diversity indices, percentage of dextral and sinistral coiling of Globigerinoides ruber, TOC%, clay content, and sapropel layer S1 (shaded patterns) in the investigated samples of core st#786. |

RDA analysis shows two main groups of foraminiferal assemblages depending on the changes of TOC% and clay content. The first group has positive loading on the x axis, while the second group is ordinated on the negative part of the x axis. The first group contains the planktic species such as: Orbulina universa, Globigerina bulloides, Globigerina calida, Globigerinoides obliquus, Globigerinoides ruber and Globigerinoides immaturus. The assemblages of this group have positive correlation with TOC% and clay content. Globigerinoides obliquus has moderate positive correlation with clay and TOC%. The second group composes of Uvigerina mediterranea, Bolivina acuminate, Bolivina advena, Bulimina marginata, Cassidulina crassa, Cassidulina laevigata, Cibicides tabaensis, Eponides frigidus, Gyroidina soldanii, Pyrgo sp, and the planktic species of Globigerinita glutinata, Globorotalia truncitulinoides, and Turborotalia clarkei. These assemblage have negative correlation with the high TOC% and clay content. Bolivina advena has moderate negative correlation with TOC% (Fig. 8).

|

Fig. 8 Ordination diagram generated from RDA for core st#786. Species abbreviations: B.ac = Bolivina acuminate, B.adv = Bolivina advena, B.mar = Bulimina marginata, C.cra = Cassidulina crassa, C.lae = Cassidulina laevigata, C.tab = Cibicides tabaensis, E.frig = Eponides frigidus, G.sol = Gyroidina soldani, Py.sp = Pyrgo sp, G.bul = Globigerina bulloides, G.cal = Globigerina calida, G.glu = Globigerinita glutinata, G.imm = Globigerinoides immaturus, G.obl = Globigerinoides obliquus, G.rub = Globigerinoides ruber, G.tru = Globorotalia truncitulinoides, O.uni = Orbulina universa, T.cla = Turborotalia clarkei, U.med = Uvigerina mediterranea. |

Fig. 9 summarizes the most important findings of the current study. Granulometry and TOC% results differenttiate between two layers. The first sapropelic layer (28-46 cm) is an organic carbon-rich sediment, with clayey texture (clay content percent up to 97.5%). The second layer (0-28 cm) has low organic carbon content (0.2%-0.35%) with silty clay texture, which is considered as an oxidized layer (Fig. 9).

|

Fig. 9 Summarized figure of the relative abundance of planktic foraminifera, benthic foraminifera, diversity indices, percentage of dextral and sinistral coiling of Globigerinoides ruber, TOC%, clay content, heterotrophic dinoflagellate species, autotrophic dinoflagellate species, and sapropel layer S1 (shaded patterns) in the investigated samples of core st#786. |

Total dinocyst counts are low in the studied core, which is comparable with the low dinocysts concentrations in the surface sediment from different Mediterranean regions as reported by Elshanawany et al. (2010). They found that the total dinoflagellate cyst concentrations vary from 44 cysts g−1 to 267 cysts g−1 in different Mediterranean sites. Most of the recorded dinocyst species in the current study are recognized in modern sediments along the Egyptian coast (Kholeif, 2008). A maximum recorded total dinoflagellate cysts and TOC% content can be considered as an indicator of maximum marine productivity, which is reached at the beginning of the formation of sapropel S1. Laskar et al. (2004) reported that this productivity coincides with maximum summer insolation at 30˚N, and indicative independently of maximum Nile discharge.

The association of dinoflagellate cyst association reflects two depositional phases in the sediment; sapropel layer (organic rich sediment and oxygen-depleted condition) represents depth from 28 to 46 cm; where heterotrophic taxa dominate and the post-sapropelic layer (the upper oxidized sediments) represents depth 0-28 cm; where autotrophic taxa dominate (Fig. 9). Previous studies reported the increased relative abundance of heterotrophic dinoflagellate cysts with the increasing marine productivity (Pospelova et al., 2004). Pospelova and Kim (2010) reported that the heterotrophic taxa such as Protoperidinium spp., Brigantedinium spp., Echinidinium spp. and Dubridinium spp. are recorded at sites with highest nutrient levels. The increase in the relative abundances of heterotrophic protoperidiniods species in sapropelic layer compared to post-sapropelic sediments suggested that they are characterized as being very sensitive to aerobic decay and can also be considered as tolerant species of the absence of oxygen which provide a signal of both enhanced marine productivity and improved the preservation of organic matter (Dale, 1976; Wall et al., 1977; Bradford and Wall, 1984; Marret, 1994; Marret and de Vernal, 1997; Harland et al., 1998; Rochon et al., 1999; Zonneveld et al., 2001, 2008, 2012). The results of present dinoflagellate cysts data are comparable with core PS009PC, recovered from the southeastern part of the Levantine Basin (van Helmond et al., 2015), at which the oxidation sensitive heterotrophic protoperidinioids and the highest total influx data for the dinocysts are recorded in the sapropel layers. This can be considered as one of the hypotheses of the formation of sapropel; where organic matter was preserved and anoxic conditions were formed at the bottom water.

The relative increase of the abundance of autotrophic species (e.g., Operculodinum iseralianium, Operculodinum spp., and Impagidinium species) and decreasing that of heterotrophic species with lowering TOC% show low primary productivity because of low flow of Nile water. This leads to the decreasing of water stratification and increasing of salinity and density of water, so it is suggest an oxic and well-ventilated conditions through this period. Elshanawany et al. (2010) considered Operculodinum iseralianium and different Impagidinium species as oligotrophic species from Mediterranean sediments and reported negative correlation with their abundances and Chl-a. Kholeif and Mudie (2009) recorded the highest relative abundances of Impagidinium patulum, Impagidinium aculeatum, and Impagidinium sphaericum in conditions of low nutrient concentration. Their high resistance to decay in oxidized sediments also distinguishes these species (Zonneveld et al., 2001). Dinoflagellate assemblage composition is differentially affected by changes in the redox potential of the sediments; since all dinocysts are well represented in anaerobic sapropel layers but with subsequent differential loss of oxidation-sensitive species during post-depositional oxidative diagenesis of the sapropel (Zonneveld et al., 2001, 2008).

The present study shows that the relative abundance of Lingulodinium machaerophorum is low within the post-sapropel oxidized layer but they show higher percentage during the pluvial periods (sapropel) where there is increase in nutrient availability in surface water when the salinity was reduced due to increased Nile river discharge. Marret and Zonneveld (2003) marked Lingulodium machreophorum as an indicator of warm stratified surface water and an indicator of rising of nutrient input. High occurrences of L. machaerophorum have been found in eutrophic areas under the effect of plumes of rivers and in areas where (seasonal) stratification occurs (Sangiorgi and Donders, 2004; Sangiorgi et al., 2005; Zonneveld et al., 2009). Elshanawany et al. (2010) reported the distribution of L. machaerophorum is related to the presence of Nile river-influenced surface water and considered that this species form a suitable marker to trace past variations in Nile river discharge. Zonneveld et al. (2001) grouped these species as being moderately sensitive species. Polysphaeridium zoharyi is a neritic species in temperate areas, most commonly found in subtropical waters and occurs in higher percentages in the sapropel sediments (Marret and Zonneveld, 2003; Marret et al., 2007). In the current study, its peak is recorded in post-sapropelic layer. The peak of Bitectatodinium tepikiense at the beginning of the sapropel may indicate a sharp temperature gradients and high seasonal thermal contrast in the upper water column as suggested by Rochen et al. (1999) and Sangiorgi et al. (2002).

5.3 Foraminiferal DiversityHigh foraminiferal diversity is recorded at depth 0-28 cm, which is matched with the decreasing TOC%. This high diversity could reflect well oxygenated environment (oxic conditions according to Jorissen et al. (1995). Low foraminiferal diversity is recorded at depth 28-46 cm (Fig. 9). This is matched with the increase of TOC% which indicates increasing of the marine productivity (eutrophication) and decreasing of oxygen level (anoxic conditions) (Fig. 9). Jorissen et al. (1995) showed that highest diversities have occurred in mesotropic and well-ventilated environmental while diversities found to be low in extremely oligotrophic, but also in eutrophic and oxygen-depleted benthic ecosystems. Furthermore, stable ecosystems enable highly diverse foraminiferal species to develop and increase. On the other hand, in ecosystems with wide environmental alterations, the foraminiferal diversities found to be decreased. In contrast to our results, Jain et al. (2007) reported that both benthic foraminiferal diversity and paleoproductivity maintained a positive relationship in the Caribbean; decreased paleoproductivity led to decreased benthic foraminiferal diversity.

5.4 Planktic CoilingIn this study sinistral and dextral coiling of Globigerinoides ruber illustrated the warm periods and cold periods throughout the studied core sediments. In the studied core st# 786, higher percentages of dextral coiling of G. ruber than sinistral coiling is recorded in the lower core part (S1) which indicates warm water (Fig. 9). Accordingly, warm water stratification is proved during the period of sapropel S1 deposition. The coiling results of present study are in agreement with Bolli (1950), Jenkins (1967) and Abdel-Kireem (1984). Jenkins (1967) recorded that Globorotalia pachyderma is sinistrally coiled in polar and subpolar seas and dextrally coiled towards lower latitudes. Abdel-Kireem (1984) reported Globigerinoides obliquus is dexterally coiled in the lower Pliocene sequence of Nile Delta (warm period), while in the middle Pliocene they are mainly sinistral (cold period).

5.5 Redundancy Analysis (RDA) and Foraminiferal assemblagesAccording to the RDA Analysis, there are two assemblages of foraminiferal species. The first assemblage correlated positively with clay content and TOC% and contains mainly planktic foraminiferal species. The composition of planktic foraminiferal species observed at a specific time-interval and location is related to the interaction between biological, hydrological (e.g., temperature, turbidity, water column stratification, salinity), and other ecological factors (e.g., food availability) (e.g., Bé and Tolderlund, 1971; Bijma et al., 1990; Schmidt et al., 2004). The first assemblage composed of Orbulina universa, Globigerina bulloides, Globigerina calida, Globigerinoides obliquus, Globigerinoides ruber and Globigerinoides immaturus. This means that these species increase with increasing terrigenous input and increasing Nile river freshwater discharge that synchronized with warm periods. These results are consistent with Zargouni et al. (2010) and Aurahs et al. (2011); they considered Orbulina universa, Globigerinoides obliquus, and Globigerinoides ruber as warm species. Globigerinoides immaturus has the same ecological niche of Orbulina universa and Globigerinoides ruber, which is considered as warm species (Nikolaev et al., 1998). In contrast, some previous studies reported that Globigerinoides ruber is a tropical-subtropical symbiont-bearing species generally inhabiting oligotrophic surface waters and tolerating a larger salinity gradient than other species (Bé and Tolderlund, 1971; Schmuker and Schiebel, 2002).

The second foraminiferal assemblage contains the planktic species of Globigerinita glutinata, Turborotalia clarkei, and Globorotalia truncitulinoides and most of benthic foraminiferal species such as Bolivina acuminate, Bolivina advena, Bulimina marginata, Cassidulina crassa, Cassidulina laevigata, Cibicides tabaensis, Eponides frigidus, Gyroidina soldanii, Pyrgo sp., and Uvigerina mediterranea. This assemblage correlates negatively with TOC% and clay content. This means that these species increase with the decreasing of the terrigenous input, which associated with decreasing of fresh water discharge of River Nile and decreasing of productivity during arid periods. de Rijk et al. (2000) reported that in the Mediterranean Sea, the distribution of C. crassa is associated with oligotrophic to mesotrophic and well ventilated conditions. In contrast, Kuhnt et al. (2007) considered the presence of C. crassa likely indicates enhanced flux rates of organic matter and high oxygen concentration in the bottom and pore waters. They reported that Cassidulina laevigata, Bulimina marginata and Uvigerina mediterranea have the same ecological niche of C. crassa. Some previous studies confirmed that Bolivinid species typically occur in high productivity areas, often combined with oxygen-depleted environments (Sen Gupta and Machain-Castillo, 1993; Bernhard and Sen Gupta, 1999). Elshanawany et al. (2011) reported high abundances of Bolivina species in eutrophic region with high organic content along the Egyptian coast.

The results of present benthic foraminifera data was in agreement with that of core LC31, 2300 m depth in Levantine Basin (Abu-Zeid et al., 2008), who recorded the oxidation sensitivity of benthic foraminifera and presence of the highest total influx data for the benthic foraminifera are in the post-sapropel layers. Also the results of studied planktic foraminifera was found to be in agreement with that of core PS009PC located in the southeastern Levantine Basin (Mojtahid et al., 2015); who observed increase of planktic foraminifera diversity and enhanced size of Globigerinoides ruber which are interpreted as a response to environmental stress caused by low saline waters during the sapropel.

5.6 Paleoclimatic InterpretationThe obtained data showed two different paleoclimatic periods; 1-Holocene pluvial S1 period; with warmer temperature and anoxic conditions. 2-Post-sapropelic oxygenated period; with normal temperature as today.

The first Holocene pluvial S1 period is highlighted by: 1) Elevation of organic content TOC% and clay content. 2) Low foraminiferal diversity. 3) Low abundance of benthic foraminifera and high abundance of planktic foraminifera. 4) Higher percentage of dextral coiling of Globigerinoides ruber than sinistral coiling which indicate warm periods. 5) Dominance of sensitive aerobic heterotrophic species rather than the resistant aerobic dinoflagellate cysts species (Fig. 9).

Sapropelic layer indicates the increase of Blue Nile suspended particulate matter discharge and related surface freshwater supply resulting in decrease of salinity and density of surface waters, and enhancing water-column stratification in the Mediterranean. So, deep waters became anoxic, leading to the formation of sapropel S1 during summer monsoon (pluvial periods). This humid period is characterized by an intensification of the geographical African monsoon, resulting from ITCZ shifting toward the north, causing an amplification and increasing of rainfall over the Ethiopian highlands, which intensify the summer floods of the River Nile (Rohling et al., 2015).

The second period has been demonstrated by low organic content TOC%, low clay content but high percentage of sand and silt, high abundance and diversity of benthic foraminifera than planktic species, higher percentage of sinistral coiling, dominance of autotrophic species of dinoflagellate cyst species and lacking of heterotrophic ones (Fig. 9).

The second period is properly characterized by reduction of Blue fresh water and related suspended particulate matter discharge supply leading to increases of salinity and density of water. The low flow of the Nile decrease the stratification of water masses in the Levantine Basin, promote the seabed re-oxygenation, decrease the terrigenous Nilotic input and therefore decrease nutrients primary productivity (Rohling et al., 2015).

6 ConclusionThe Mediterranean Basin is generally oligotrophic and well-ventilated, and its surface sediments are poor in organic carbon However, the Eastern Mediterranean sedimentary record is characterized by the widespread and distinctly periodical occurrence of organic carbon-rich layers, called sapropels. The currently accepted model for the formation of most Eastern Mediterranean sapropels proposes that maxima in insolation during precession minima caused an intensification of the monsoon system on the North African continent. Subsequently, enhanced river discharge largely impacted the Mediterranean water circulation, resulting in stratification of the water column, slowdown or total shutdown of deep-water formation resulted in enhanced preservation of organic matter at the sea floor. The current study assessed the past environmental changes in trophic state and temperature using paleontological analysis of Holocene core samples located in the middle slope of the eastern Mediterranean Sea. The multi-core st#786, offshore Egypt, was used to study grain size, total organic carbon, planktic foraminifera, benthic foraminifera, and dinoflagellate cysts. The obtained paleontological and sedimentological analyses data showed two different paleoclimatic periods; Holocene pluvial sapropel S1 period and post-sapropelic oxygenated period. Sapropel S1 layer is highlighted by the elevation of TOC%, clayey texture of the sediment content, dominance of planktic foraminifera compared to benthic foraminifera, increase of the percentage of dextral coiling of Globigerinoides ruber than sinistral coiling, decrease of foraminiferal diversity, and dominance of heterotrophic dinoflagellate cysts species.

AcknowledgementsMany thanks to Suzan Kholeif, the professor in National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries NIOF for providing the core samples of METEOR cruise M70b (October 2006).

Abdel-Kireem, M. R., 1984. Planktonic foraminifera of Mokattam Formation (Eocene) of Gebel Mokattam, Cairo, Egypt. Revue de Micropaleontologie, 28: 77-96. (  0) 0) |

Abu-Zied, R. H., Rohling, E. J., Jorissen, F. J., Fontanier, C., James, S. L., Casford, J. S. L. and Cooke, S., 2008. Benthic foraminiferal response to changes in bottom-water oxygenation and organic carbon flux in the eastern Mediterranean during LGM to recent times. Marine Micropaleontology, 67: 46-68. DOI:10.1016/j.marmicro.2007.08.006 (  0) 0) |

Aurahs, R., Treis, Y., Darling, K. and Kucera, M., 2011. A revised taxonomic and phylogenetic concept for the planktonic foraminifer species Globigerinoides ruber based on molecular and morphometric evidence. Marine Micropaleontology, 79: 1-14. DOI:10.1016/j.marmicro.2010.12.001 (  0) 0) |

Badawi, A., 2015. Late quaternary glacial/interglacial cyclicity models of the Red Sea. Environmental Earth Sciences, 73: 961-977. DOI:10.1007/s12665-014-3446-8 (  0) 0) |

Bé, A. W. H., and Tolderlund, D. S., 1971. Distribution and ecology of living planktonic foraminifera in surface waters of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In: The Micropaleontology of Oceans. Funnel, B. M., and Riedel, W. R., eds., 105-149.

(  0) 0) |

Belmonte, G., Castello, P., Piccinni, M. R., Quarta, S., Rubino, F., Boero, F., and Geraci, S., 1995. Resting stages in marine sediments off the Italian coasts. In: Biology and Ecology of Shallow Coastal Waters. Eletheriou, A., Ansell, A. D., and Smith, C. J., eds., Olsen and Olsen, Fredensborg, 53-58.

(  0) 0) |

Bernhard, J., and Sen Gupta, B., 1999. Foraminifera of oxygen-depleted environments. In: Modern Foraminifera. Gupta, S., ed., Kluwer Acaemic Publishers, New York, 201-216.

(  0) 0) |

Bernhardt, C., Horton, B. P. and Stanley, D. J., 2012. Nile Delta response to holocene climate variability. Geology, 40(7): 615-618. DOI:10.1130/G33012.1 (  0) 0) |

éthoux, J. P. and Pierre, C., 1999. Mediterranean functioning and sapropel formation: Respective influences of climate and hydrological changes in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Marine Geology, 153: 29-39. DOI:10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00091-7 (  0) 0) |

Bickert, T. and Wefer, G., 1999. South Atlantic and benthic foraminifer δ13C deviations: Implications for reconstructing the Late Quaternary deep-water circulation. Deep Sea Research Ⅱ, 46: 437-452. DOI:10.1016/S0967-0645(98)00098-8 (  0) 0) |

Bijma, J., Erez, J. and Hemleben, C., 1990. Lunar and semi-lunar reproductive cycles in some spinose planktonic foraminifers. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 20: 117-127. DOI:10.2113/gsjfr.20.2.117 (  0) 0) |

Bolli, H. M., 1950. The direction of coiling in the evolution of some Globorotaliidae. Contributions from the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research, 1: 82-89. (  0) 0) |

Bradford, M. R. and Wall, D. A., 1984. The distribution of organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts in the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, and northwestern Arabian Sea. Paleontographica, 192: 16-84. (  0) 0) |

Candela, J., 1991. The Gibraltar Strait and its role in the dynamics of the Mediterranean Sea. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans, 15: 267-299. DOI:10.1016/0377-0265(91)90023-9 (  0) 0) |

Cramp, A. and O'Sullivan, G., 1999. Neogene sapropel in the Mediterranean: A review. Marine Geology, 153: 11-28. DOI:10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00092-9 (  0) 0) |

Dale, B., 1976. Cyst formation, sedimentation, and preservation: Factors affecting dinoflagellate assemblages in recent sediments from Trondheimsfjord, Norway. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 22: 39-60. DOI:10.1016/0034-6667(76)90010-5 (  0) 0) |

Dale, B., 1996. Dinoflagellate cyst ecology: Modeling and geological applications. In: Palynology: Principles and Applications. Jansonius, J., and McGregor, D. C., eds., American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists Foundation, Dallas, 1249-1276.

(  0) 0) |

de Rijk, S., Jorissen, F., Rohling, E. and Troelstra, S., 2000. Organic flux control on bathymetric zonation of Mediterranean benthic foraminifera. Marine Micropalaeotology, 40: 151-166. DOI:10.1016/S0377-8398(00)00037-2 (  0) 0) |

de Vernal, A., and Marret, F., 2007. Organic-walled dinoflagellates: Tracers of sea-surface conditions. In: Proxies in Late Cenozoic Paleoceanography. Hillaire-Marcel, C., and de Vernal, A., eds., Elsevier, 371-408.

(  0) 0) |

Elshanawany, R., Zonneveld, K., Ibrahim, M. L. and Kholeif, S. E., 2010. Distribution patterns of recent organic-walled dinoflagellate cyst in relation to environmental parameters in the Mediterranean Sea. Palynology, 2: 233-260. (  0) 0) |

Elshanawany, R., Ibrahim, M. I., Milker, Y., Schmiedl, G., Kholeif, S. E., Badr, N. and Zonneveld, K. A., 2011. Anthropogenic impact on benthic foraminifera, Abu-Qir Bay, Alexandria, Egypt. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 41: 326-348. DOI:10.2113/gsjfr.41.4.326 (  0) 0) |

Fisher, R. A., Corbet, A. S. and Williams, C. B., 1943. The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. Journal of Animal Ecology, 12: 42-58. DOI:10.2307/1411 (  0) 0) |

Foucault, A. and Stanley, D., 1989. Late Quaternary paleoclimatic oscillations in East Africa recorded by heavy minerals in the Nile delta. Nature, 399: 44-46. (  0) 0) |

Gaines, G., and Elbraechter, M., 1987. Heterotrophic nutrition. In: The biology of dinoflagellates. Taylor, F. J. R., ed., Blackwell Scientific, Oxford, 224-281.

(  0) 0) |

Gasse, F., 2000. Hydrological changes in the African tropics since the Last Glacial Maximum. Quaternary Science Reviews, 19: 189-211. DOI:10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00061-X (  0) 0) |

Gaudette, H., Flight, W., Toner, L. and Folger, D., 1974. An inexpensive titration method for the determination of organic carbon in recent sediments. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 44: 249-253. (  0) 0) |

Harland, R., Pudsey, C. J., Howe, J. A. and Fitzpatrick, M. E., 1998. Recent dinoflagellate cysts in a transect from the Falklands through to the Weddell Sea, Antarctica. Palaeontology, 41: 1093-1131. (  0) 0) |

Jain, S., Collins, L. S. and Hayek, L. C., 2007. Relationship of benthic foraminiferal diversity to paleoproductivity in the Neogene Caribbean. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 255: 223-245. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.017 (  0) 0) |

Jenkins, D., 1967. Recent distribution, origin, and coiling ratio changes in Globorotalia pachyderma (Ehrenberg). Micropaleontology, 13: 195-203. DOI:10.2307/1484670 (  0) 0) |

Jorissen, F. J., De Stigter, H. and Widmark, J., 1995. A conceptual model explaining benthic foraminiferal microhabitats. Marine Micropaleontology, 26: 3-15. DOI:10.1016/0377-8398(95)00047-X (  0) 0) |

Kholeif, S. E. A., 2008. Palynofacies is a useful tool to study the palaeoenvironmental conditions of the water columin: An example from southeastern Mediterranean. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic research, 34: 110-126. (  0) 0) |

Kholeif, S. E. A. and Mudie, P. J., 2009. Palynomorph and amorphous organic matter records of climate and oceanic conditions in Late Pleistocene and Holocene sediments of the Nile Cone, southeastern Mediterranean. Palynology, 32: 1-24. (  0) 0) |

Kholeif, S. E. A. and Ibrahim, M. I., 2010. Palynofacies Analysis of Inner Continental Shelf and Middle Slope Sediments offshore Egypt, South-eastern Mediterranean. Geobios, 43: 333-347. DOI:10.1016/j.geobios.2009.10.006 (  0) 0) |

Krom, M. D., Groom, S., and Zohary, T., 2003. The Eastern Mediterranean. In: the Biogeochemistry of Marine Systems. Black, K. D. S. G. B., ed., Blackwell, 91-126.

(  0) 0) |

Kuhnt, T., Schmiedl, G., Ehrmann, W., Hamann, Y. and Hemleben, C., 2007. Deep-sea ecosystem variability of the Aegean Sea during the past 22 kyr as revealed by Benthic Foraminifera. Marine Micropaleontology, 64: 141-162. DOI:10.1016/j.marmicro.2007.04.003 (  0) 0) |

Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correia, A. C. M. and Levrard, B., 2004. A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the earth. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 428: 261-285. DOI:10.1051/0004-6361:20041335 (  0) 0) |

Leps, J., and Smilauer, P., 2005. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data Using CANOCO. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 269pp.

(  0) 0) |

Leyer, I., and Wesche, K., 2007. Multivariate Statistik in der Ökologie. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 221pp.

(  0) 0) |

Loeblich, A. R., and Tappan, H., 1987. Foraminiferal General and their Classification. van Nostrand Reinhold Comp., New York, 1182pp.

(  0) 0) |

Mackensen, A., Grobe, H., Hubberten, H. W., and Kuhn, G., 1994. Benthic foraminiferal assemblages and the 13C signal in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean: Glacial to interglacial contrasts. In: Carbon Cycling in the Glacial Ocean: Constraints on the Ocean's Role in Global Change, NATO ASI Series I. Zahn, R., Pedersen, T. F., Kaminski, M. A. and Labeyrie, L., eds., 105-144.

(  0) 0) |

Marret, F., 1994. Distribution of Dinoflagellate cysts in recent marine sediments from the east Equatorial Atlantic (Gulf of Guinea). Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 84: 1-22. DOI:10.1016/0034-6667(94)90038-8 (  0) 0) |

Marret, F. and de Vernal, A., 1997. Dinoflagellate cyst distribution in surface sediments of the southern Indian Ocean. Marine Micropaleontology, 29: 367-392. DOI:10.1016/S0377-8398(96)00049-7 (  0) 0) |

Marret, F. and Zonneveld, K. A., 2003. Atlas of Modern organic-walled dinoflagellate cyst distributions. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 125: 1-200. DOI:10.1016/S0034-6667(02)00229-4 (  0) 0) |

Marret, F., Mudie, P. J., Aksu, A. E. and Hiscott, R., 2007. A Holoscene dinocyst record of a two-step transformation of the Neoeuxinian brackish water lake into the Black Sea. Quaternary International, 197: 72-86. (  0) 0) |

Mojtahid, M., Manceau, R., Schiebel, R., Hennekam, R. and De Lange, G. J., 2015. 13000 years of southeastern Mediterranean climate variability inferred from an integrative planktic foraminiferal-based approach. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 30: 402-422. (  0) 0) |

Murray, J. W., 1991. Ecology and paleoecology of benthonic foraminifera, 397pp. London, New York, Longman Scientific and Technical/Wiley.

(  0) 0) |

Murat, A. and Got, H., 2000. Organic carbon variations of the eastern Mediterranean Holocene sapropel: A key for understanding formation processes. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 158: 241-257. DOI:10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00052-3 (  0) 0) |

Nikolaev, S., Oskina, N., Blyum, N. and Bubenshchikova, N., 1998. Neogene-Quaternary variations of the 'Pole-Equator' temperature gradient of the surface oceanic waters in the North Atlantic and North Pacific. Global and Planetary Change, 18: 85-111. DOI:10.1016/S0921-8181(98)00009-5 (  0) 0) |

Pospelova, V., Chmura, G. L. and Walker, H. A., 2004. Environmental factors influencing the spatial distribution of dinoflagellate cyst assemblages in shallow lagoons of southern New England (USA). Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 128: 7-34. DOI:10.1016/S0034-6667(03)00110-6 (  0) 0) |

Pospelova, V. and Kim, S. J., 2010. Dinoflagellate cysts in recent estuarine sediment from aquaculture sites of southern South Korea. Marine Micropaleontology, 76: 37-51. DOI:10.1016/j.marmicro.2010.04.003 (  0) 0) |

Psarra, S., Tselepidesa, A. and Ignatiades, L., 2000. Primary productivity in the oligotrophic Cretan Sea (NE Mediterranean): Seasonal and interannual variability. Progress in Oceanography, 46: 187-204. DOI:10.1016/S0079-6611(00)00018-5 (  0) 0) |

Psarra, S., Zohary, T., Krom, M. D., Fauzi-Mantoura, R. F. C., Polychronaki, T., Stambler, N., Tanaka, T., Tselepides, A. and Thingstad, T. F., 2005. Phytoplankton response to a Lagrangian phosphate addition in the Levantine Sea (Eastern Mediterranean). Deep Sea Research Ⅱ, 52: 2944-2960. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2005.08.015 (  0) 0) |

Rochon, A., de Vernal, A., Turon, J. L., Matthiessen, J. and Head, M. J., 1999. Distribution of recent dinoflagellate cysts in surface sediments from the North Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas in relation to sea-surface sediments parameters. American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists Contribution Series, 35: 1-150. (  0) 0) |

Rohling, E. J., 1994. Review and new aspects concerning the formation of eastern Mediterranean sapropels. Marine Geology, 122: 1-28. DOI:10.1016/0025-3227(94)90202-X (  0) 0) |

Rohling, E. J., Marino, G. and Grant, K. M., 2015. Mediterranean climate and oceanography, and the periodic development of anoxic events (sapropels). Earth-Science Reviews, 143: 62-97. DOI:10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.01.008 (  0) 0) |

Rossignol-Strick, M., 1985. Mediterranean Quaternary sapropels, an immediate response of the African monsoon to variation of insolation. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 49: 237-263. DOI:10.1016/0031-0182(85)90056-2 (  0) 0) |

Sangiorgi, F. and Donders, T. H., 2004. Reconstructing 150 years of eutrophication in the north western Adriatic Sea (Italy) using dinoflagellate cysts, pollen and spores. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 60: 69-79. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2003.12.001 (  0) 0) |

Sangiorgi, F., Capotondi, L. and Brinkhuis, H., 2002. Acentennial scale organic walled dinoflagellate cyst record of the last deglaciation in the South Adriatic Sea (Central Mediterranean). Paleogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 186: 199-216. DOI:10.1016/S0031-0182(02)00450-9 (  0) 0) |

Sangiorgi, F., Capotondi, L., Combourieu Nebout, N., Vigliotti, L., Brinkhuis, H., Giunta, S., Lotter, A. F., Morigi, C., Negri, A. and Reichart, G. J., 2005. Holocene seasonal sea-surface temperature variations in the southern Adriatic Sea inferred from a multiproxy approach. Journal of Quaternary Science, 18: 723-732. (  0) 0) |

Schmidt, D. N. S., Renaud, J., Bollmann, R., Schiebel, H. R. and Thierstein, R., 2004. Size distribution of Holocene planktic foraminifer assemblages: Biogeography, ecology and adaptation. Marine Micropaleontology, 50: 319-338. DOI:10.1016/S0377-8398(03)00098-7 (  0) 0) |

Schmiedl, G., Hemleben, C., Keller, j. and Segl, M., 1998. Impact of climatic changes on the benthic foraminiferal fauna in the Ionian Sea during the last 330, 0000 years. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 13: 447-458. (  0) 0) |

Schmuker, B. and Schiebel, R., 2002. Planktic foraminifers and hydrography of the eastern and northern Caribbean Sea. Marine Micropaleontology, 46: 387-403. DOI:10.1016/S0377-8398(02)00082-8 (  0) 0) |

Scrivner, A. E., Vance, D. and Rohling, E. J., 2004. New neodymium isotope data quantify Nile involvement in Mediterranean anoxic episodes. Geology, 32: 565-568. DOI:10.1130/G20419.1 (  0) 0) |

Sen Gupta, B. and Machain-Castillo, M., 1993. Benthic foraminifera on oxygen-poor habitats. Marine Micropaleontology, 20: 183-201. DOI:10.1016/0377-8398(93)90032-S (  0) 0) |

Shannon, C. E., 1948. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal, 27: 379-423, 623-656. DOI:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x (  0) 0) |

Stanley, D. J. and Maldonado, A., 1977. Nile Cone: Late quaternary stratigraphy and sediment dispersal. Nature, 266: 129-135. DOI:10.1038/266129a0 (  0) 0) |

Sweet, S., Laswell, S., and Wade, T., 1998. Sediment grain size analysis: Gravel, sand, silt and clay. In: Sampling and Analytical Methods of the National Status and Trends Program Mussel Watch Project 1993-1996 Update.

(  0) 0) |

Lauenstein, G. G., and Cantillo, A. Y., eds., NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA, 130pp.

(  0) 0) |

Taylor, F. J. R., and Pollingher, U., 1987. The ecology of dinoflagellates. In: The Biology of Dinoflagellates. Taylor, F. J. R., ed., Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 398-529.

(  0) 0) |

Ter-Braak, C. J. F., and Smilauer, P., 2002. CANOCO Reference Manual and CanoDraw for Windows User's Guide (Version 4.5). Microcomputer power Ithaka, NY, 500pp.

(  0) 0) |

Turley, C. M., Bianchi, M., Christaki, U., Conan, P., Harris, J. R. W., Psarra, S., Ruddy, G., Stutt, E. D., Tselepides, A. and van Wambeke, F., 2000. Relationship between primary producers and bacteria in an oligotrophic sea - the Mediterranean and biogeochemical implications. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 193: 11-18. DOI:10.3354/meps193011 (  0) 0) |

van Helmond, N. A. G. M., Hennekam, R., Donders, T. H., Bunnik, F. P. M., de Lange, G. J., Brinkhuis, H. and Sangiorgi, F., 2015. Marine productivity leads organic matter preservation in sapropel S1: Palynological evidence from a core east of the Nile River outflow. Quaternary Science Reviews, 108: 130-138. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.11.014 (  0) 0) |

Versteegh, G. J. M. and Zonneveld, K. A. F., 2002. Use of selective degradation to separate preservation from productivity. Geology, 30: 615-618. DOI:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0615:UOSDTS>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Wall, D., Dale, B., Lohman, G. P. and Smith, W. K., 1977. The environmental and climatic distribution of dinoflagellate cysts in the North and South Atlantic Oceans and adjacent seas. Marine Micropaleontology, 12: 121-200. (  0) 0) |

Williams, M., Adamson, D., Cock, B. and Mc Evedy, R., 2000. Late quaternary environments in the White Nile region, Sudan. Global and Planetary Change, 26: 305-316. DOI:10.1016/S0921-8181(00)00047-3 (  0) 0) |

Yacobi, Y. Z., Zohari, T., Kress, N., Hecht, A., Robarts, R. D., Waiser, M., Wood, A. M. and Li, W. K. W., 1995. Chlorophyll distribution throughout the southeastern Mediterranean in relation to the physical structure of the water mass. Journal of Marine System, 6: 179-189. DOI:10.1016/0924-7963(94)00028-A (  0) 0) |

Zargouni, I., Turon, J., Londeix, L., Essallami, L., Kallel, N. and Sicre, M., 2010. Environmental and climatic changes in the central Mediterranean Sea (Siculo-Tunisian Strait) during the last 30 ka based on dinoflagellate cyst and planktonic foraminifera assemblages. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 285: 17-29. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.10.015 (  0) 0) |

Zonneveld, K. A. F., Versteegh, G. J. M. and de Lange, G. J., 2001. Palaeoproductivity and postdepositional aerobic organic matter decay reflected by dinoflagellate cyst assemblages of the eastern Mediterranean S1 sapropel. Marine Geology, 172: 181-195. DOI:10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00134-1 (  0) 0) |

Zonneveld, K. A. F., Versteegh, G. J. M. and Kodrans-Nsiah, M., 2008. Preservation and organic chemistry of Late Cenozoic organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts: A review. Marine Micropaleontology, 68: 179-197. DOI:10.1016/j.marmicro.2008.01.015 (  0) 0) |

Zonneveld, K. A. F, Chen, L., Möbius, J. and Mahmoud, M. S., 2009. Environmental significance of dinoflagellate cysts from the proximal part of the Po-river discharge plume (off southern Italy, Eastern Mediterranean). Journal of Sea Research, 62: 189-213. DOI:10.1016/j.seares.2009.02.003 (  0) 0) |

Zonneveld, K. A. F., Chen, L., Elshanawany, R., Fischer, H. W., Hoins, M., Ibrahim, M. I., Pittauerova, D. and Versteegh, G. J., 2012. The use of dinoflagellate cysts to separate human-induced from natural variability in the trophic state of the Po-River discharge plume over the last two centuries. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 64: 114-132. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.10.012 (  0) 0) |

Zonneveld, K. A. F. and Pospelova, V., 2015. A determination key for modern dinoflagellate cysts. Palynology, 39: 387-409. DOI:10.1080/01916122.2014.990115 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18