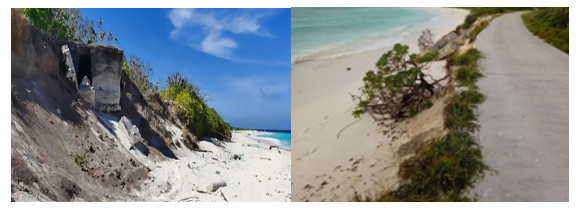

The flow-slip damage of calcareous sand slopes, triggered by tidal or wave scouring, presents a major engineering challenge for the construction of islands and reefs in the South China Sea. This damage occurs because pore water seepage in calcareous sand slopes increases pore water pressure under constant shear stress. This condition reduces the mean effective stress along the potential damage surface and leads to flow-slip deformation. The rapid and severe nature of flow-slip damage inflicts considerable damage on near-coastal constructions, as exemplified in Fig.1. Concrete structural measures such as breakwaters, dykes, and seawalls are currently used to protect shore slopes from wave erosion. These methods cost-effectively reduce sand losses from sandy shorelines. However, they disturb the natural sediment transport regime on the shore slope, causing new erosion problems and damaging the nearshore ecosystem. Besides, constructing these structures requires large amounts of concrete, which introduces pollutants into the environment due to its chemical composition (Kim et al., 2009). Therefore, a new slope protection method is urgently needed, one that prioritizes energy efficiency, environmental friendliness, and sustainability.

|

Fig. 1 Coastal slope flow-slip damage. |

Recent research highlights microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) as a groundbreaking and sustainable approach to slope protection (Ivanov and Chu, 2008; DeJong et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023b). This fast, efficient, and controllable technology, characterized by a simple operating principle and high environmental tolerance, aligns well with the needs of ecological island and reef construction initiatives (Whiffin et al., 2007; Chou et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2021; He et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023a). Bacillus subtilis, known for its exceptional urease production, is the microorganism of choice for MICP because of its natural abundance and environmental friendliness (Liu et al., 2023). Highly active urease enzymes within the bacterial cells break down urea into NH4+, CO32−, and other ions, inducing the precipitation of calcium carbonate crystals around the cell wall. This process results from the interaction between the CO32− and Ca2+ adsorbed onto the bacterial surface from the surrounding environment. The specific reaction process can be written as

| $ {\text{C}}{{\text{a}}^{2 + }} + {\text{Cell}} \to {\text{Cell}} - {\text{C}}{{\text{a}}^{2 + }}, $ | (1) |

| $ {\text{N}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}} - {\text{CO}} - {\text{N}}{{\text{H}}_2} + 2{{\text{H}}_2}{\text{O}}\xrightarrow{{{\text{Ureases}}}}2{\text{NH}}_4^ + + {\text{CO}}_{\text{3}}^{{\text{2}} - }, $ | (2) |

| $ {\text{CO}}_{\text{3}}^{{\text{2}} - } + {\text{Cell}} - {\text{C}}{{\text{a}}^{{\text{2 + }}}} \to {\text{Cell}} - {\text{CaC}}{{\text{O}}_3} \downarrow . $ | (3) |

The generated calcium carbonate, usually in the form of calcite, fills soil pores and binds soil particles, thereby increasing soil strength and improving its physical and mechanical properties (DeJong et al., 2010; Van Paassen et al., 2010; Montoya and DeJong, 2015; O'Donnell and Kavazanjian, 2015; Choi et al., 2019; Roksana et al., 2023). The MICP method effectively fortifies sand slopes against the erosive forces of wave scour (Shanahan and Montoya, 2016; Xiao et al., 2018; Chek et al., 2021; Kou et al., 2022). For example, Lin et al. (2016) showed that MICP treatment significantly enhances the shear strength and cohesion of quartz sand specimens while reducing their compressibility through triaxial compression tests. Liu et al. (2019) showed the remarkable potential of MICP in boosting the mechanical performance of calcareous sand, particularly enhancing its strength and stiffness, through laboratory tests such as unconfined compressive and consolidated drainage triaxial tests. Arboleda-Monsalve et al. (2019) revealed, through K0 triaxial tests, that soil compressibility significantly reduces after MICP treatment. These studies investigate the mechanical behavior of MICP-treated sands using triaxial tests under standard stress paths. However, triaxial tests, although valuable, are inadequate for capturing the nuanced interplay of low-stress conditions and complex geometries that drive coastal slope instability. The constant shear drained (CSD) test simulates the combined effects of rising pore water pressure and decreasing mean effective stress, making it a valuable choice for replicating the mechanisms of coastal slope failure. To the authors' knowledge, studies on the destabilization of calcareous sandy coastal slopes under constant shear stress are limited. Hang et al. (2019) used CSD tests to investigate the influence of microbial curing and relative density on the mechanical performance of quartz sands. They demonstrated that biocementation effectively increases the shear strength of the specimens and improves the stability of the sand against water infiltration or liquefaction. Hang et al. (2022) employed CSD tests to unveil the remarkable potential of microbial curing in enhancing the resilience of quartz sand slopes to submerged erosion. However, a critical gap still remains in understanding the behavior of microbially treated calcareous sand slopes under diverse cell pressure scenarios. The precise mechanisms behind their enhanced stability are not fully explained. A comprehensive experimental study on the stability performance of MICP-treated calcareous sandy coastal slopes under the flow-slip stress path is necessary.

The main objectives of this study are to comprehensively assess the effect of microbial treatment on the flow-slip stability of calcareous sand slopes and elucidate its underlying mechanisms and potential applications in coastal slope stabilization. The study first analyzed the effects of treatment (T), initial relative density (Dr), initial cell pressure (σ0), and initial stress ratio (q/p') on the stability of calcareous sand slopes through CSD tests. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was then used to look into the intricate microstructure of the treated specimens, revealing the mechanisms by which microbial treatment enhances flow-slip stability.

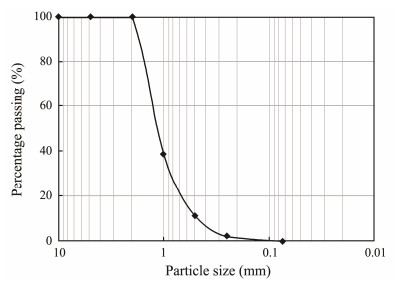

2 Materials and Specimen Preparation 2.1 Calcareous SandThe sand used in this study was sourced from a coral island area in the South China Sea. It comprises fine calcareous material enriched with coral fragments. To ensure homogeneity and remove potential biases, the collected sand was air-dried and sieved through a 2.0 mm mesh to remove oversized particles, such as marine organism residues. The cumulative particle-size distribution curve and main parameters of the sand sample are depicted in Fig.2 and Table 1, respectively. The sand sample exhibited good particle homogeneity (ASTM D2487).

|

Fig. 2 Particle size distribution of calcareous sand. |

|

|

Table 1 Main parameters of the tested sand |

Sporosarcina pasteurii (ATCC1 1859) was used for MICP tests owing to its strong mineralization deposition capacity (Sharma et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2024). The microbial cultivation method was similar to those in published studies (Kou et al., 2022, 2023). The urease activity in the bacterial solution was around 2.0 ms cm−1 min−1. The cementation solution contained 0.5 mol L−1 urea and 0.5 mol L−1 CaCl2 (Sharma et al., 2019, 2021; Liufu et al., 2023). The fixative solution was CaCl2 at a concentration of 0.05 mol L−1.

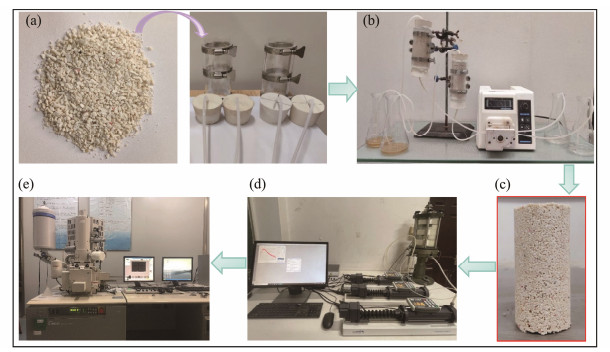

2.3 Specimen PreparationTwo sand samples with varied initial relative densities (20% and 40%) were prepared to depict the loose and medium-dense states of sand under field conditions. A cylindrical mold, 100 mm in height and 50 mm in inner diameter, was used to prepare the specimens (Fig.3a) for triaxial tests. The mold's inner wall was first lined with a transparent PVC sheet secured by a bottom rubber stopper. Additionally, a layer of filter paper was placed at the bottom of the mold to prevent sand particles from clogging the grout pipe. The material required for each layer was weighed and poured into the mold, with each specimen manually compacted into three separate layers. Last, rubber plugs and filter paper were placed on the top of the specimen to complete the filling process.

|

Fig. 3 Test procedures. (a), filling molds; (b), grouting processes; (c), treated specimen; (d), CSD test setup; (e), SEM test setup. |

Fig.3b details the grouting process, where a peristaltic pump injects an initial 50 mL of fixative solution to enhance the utilization of bacterial solution. Next, 100 mL (1.5 pore volumes) of bacterial solution was carefully injected into the specimen through the mold's top at a rate of 3 mL min−1. After the bacterial solution injection phase for 8 h, 100 mL of cementation solution was injected into the specimen at the same rate to finalize the adhesion. The specimen was then set aside for 12 h to complete the first round of grouting. This grouting process was conducted twice for each group of calcareous sand samples. Afterward, the specimen was incubated in a constant temperature box for 48 h, as displayed in Fig.3c, yielding the treated specimen.

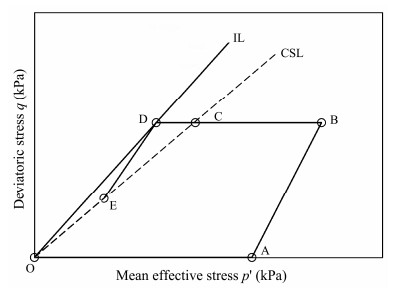

3 Test Methods 3.1 Constant Shear Drained TestThe CSD test aligns closely with the complex stress strain behavior observed in slope instability scenarios. The CSD tests were carried out on a Standard Stress Path Triaxial Test System (model: STDTTS-X, serial number: Y) manufactured by GDS Instruments Ltd. (UK), as shown in Fig. 3d. Fig.4 illustrates the stress path test principle of CSD tests (Chu et al., 2012), involving 1) soil consolidation (O – A); 2) compression drainag shear test under conventional conditions (A – B), and 3) constant shear stress development (B – C).

|

Fig. 4 Diagram of effective stress path of constant shear drained (CSD). OA, isotropic compression stage; AB, compression drainage (CD) shear stage; BC, constant shear stress development stage; CD, unstable stage; DE, flow-slip damage process. |

Following established protocols, the CSD test specimens were saturated within a pressure chamber using the backpressure saturation method. This saturation was achieved when the Skempton B coefficient exceeded 0.98. Consolidation was subsequently performed on the saturated specimens at 50, 100, and 200 kPa effective pressures. The cell pressure and back pressure were maintained constantly for drainage shear. While maintaining the constant total stress, the back pressure was incremented at 6.5 kPa min−1 until the specimen's axial strain reached 25%. Twentyfour groups of CSD tests were conducted in this study. The CSD test investigated the effects of four factors on the mechanical behavior of the sand: microbial treatment (T), initial relative density (Dr), initial cell pressure (σ0), and initial stress ratio (q/p'). These factors are summarized in Table 2.

|

|

Table 2 Test schemes |

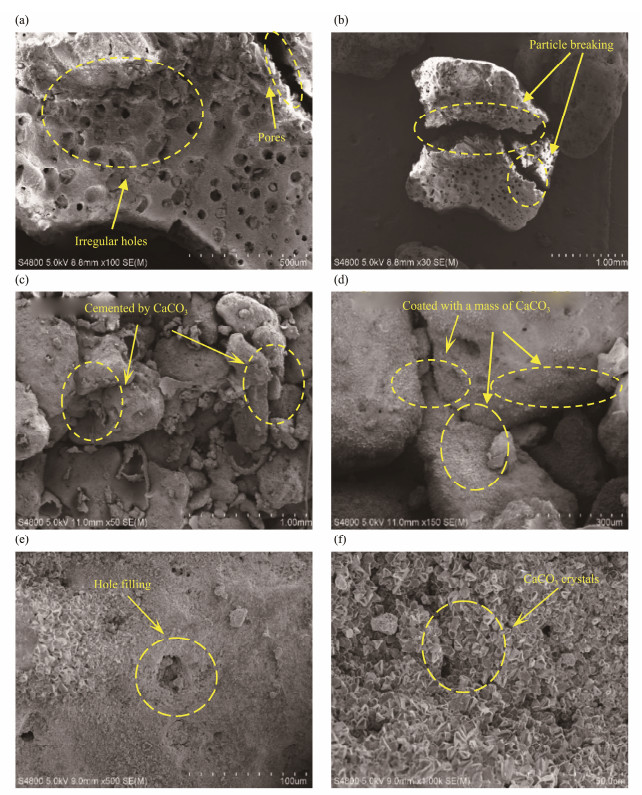

To study the microscopic morphology of the specimens under different treatment conditions, an SEM test was conducted using a HITACHIS-4800 field emission scanning electron microscope, as shown in Fig.3e. A flat and representative cross-section of the specimen was prepared for this test. After drying in a 60℃ oven, each specimen was mounted on a metal base using a conductive adhesive. Specimens were coated with a conductive film followed by gold sputtering to enhance surface conductivity and enable clear observation of the micro-morphology. The magnifications used in this study were 30×, 50×, 100×, 150×, 500×, and 1000×.

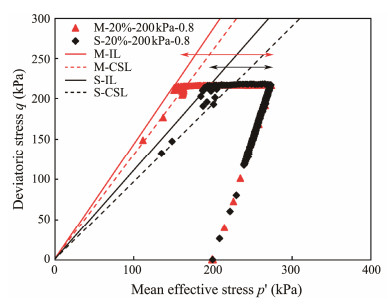

4 Results and Discussion 4.1 Effect of Microbial Treatment on Flow-Slip StabilityFig.5 illustrates the effective stress path of calcareous sands for shear damage under flow-slip stress (T = 0, 1) for Dr = 20%, q/p' = 0.8, and σ0 = 200 kPa. The black solid and dotted lines represent the instability line (IL) and critical state line (CSL) for untreated calcareous sand, respectively. Similarly, the red solid and dotted lines denote the IL and CSL for microbial-treated sand (Castro, 1975; Leroueil, 2001), respectively. Within the CSD path, the specimen exhibits instability characterized by a sharp drop in deviatoric stress. The microbial-treated specimen maintains a longer stress path for stabilization. The slopes of the ILs for untreated and microbial-treated specimens are 1.10 and 1.43, respectively. The slope of the IL for the microbial-treated specimen was larger than that of the untreated specimen, indicating that the microbial treatment evidently enhances the stability of calcareous sand.

|

Fig. 5 Effective stress path curves of calcareous sand (T = 0, 1). |

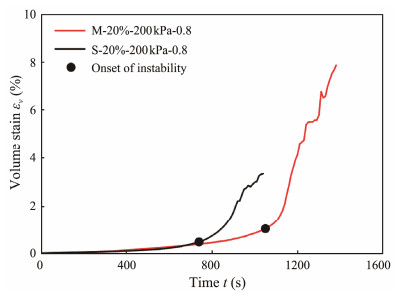

Fig.6 presents the volumetric strain curves of calcareous sand (T = 0, 1) under flow-slip stress-induced shear damage. The onset of instability in calcareous sand is marked by a sharp rise in volumetric strain. Microbial treatment significantly extends the time to reach instability. For instance, the time increased from 740 s (T = 0) to 1050 s (T = 1), representing roughly a 1.4-fold increase in the time to reach instability because of microbial treatment. Moreover, the microbial treatment (T = 1) significantly increases the with-standable volumetric strain during instability from 0.50% (T = 0) to 1.05%. The results show that the microbial-treated specimens need more time to reach instability and can withstand greater volumetric strain. The microbial treatment significantly enhances the stability of specimens under constant shear stress. This enhancement is attributed to the calcium carbonate precipitate induced by microorganisms, which fills the intergranular voids within the sand matrix to cement adjacent particles together. This changes the internal pore structure and particle grading of the specimens, improving the flow-slip stability of the calcareous sands.

|

Fig. 6 Volumetric strain curves of calcareous sand (T = 0, 1). |

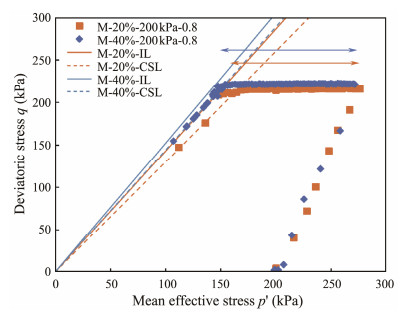

Fig.7 exhibits the effective stress path of microbial-treated specimens with different initial relative densities under the conditions of σ0 = 200 kPa and q/p' = 0.8. The wedge-shaped region enclosed by the IL and CSL is referred to as the unstable region (Lade, 1992). For the same cell pressure and initial stress ratio conditions, the mean effective stress at the point of instability decreases as the initial relative density increases. The mean effective stresses at destabilization are 159.7 and 151.0 kPa for Dr = 20% and Dr = 40%, respectively. A higher initial relative density results in a longer path of maintained stabilizing stress. Moreover, the unstable region of the specimens with higher initial relative density shifts toward the upper left of the coordinate axis compared with the specimens with lower initial relative density. Furthermore, the region of instability enclosed by the solid and dashed lines is smaller for the specimens with Dr = 40%, indicating that the internal structure of specimens with higher initial relative density is more stable.

|

Fig. 7 Effective stress path curves of microbial-treated specimens with different initial relative densities. |

Fig.8 displays the volumetric strain of microbial-treated specimens with different initial relative densities under the conditions of σ0 = 200 kPa and q/p' = 0.8. The required time to reach instability and the critical volumetric strain increase as the initial relative density increases. For Dr = 20% and Dr = 40%, the required time to reach instability varies from 1050 to 1310 s, and the critical volumetric strains are 1.05% and 1.19%, respectively. This is because of the fewer voids and closer inter-particle contact in mediumdense calcareous sand specimens. In addition, the sand skeleton can bear prolonged periods of constant shear stress. Therefore, actively increasing the density of coastal slopes becomes a crucial engineering priority to enhance stability in practical engineering applications.

|

Fig. 8 Volumetric strain curves of microbial-treated specimens with different initial relative densities. |

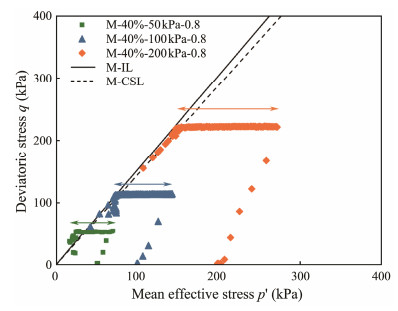

Fig.9 presents the effective stress path for microbial-treated specimens with varying initial cell pressures under the conditions of Dr = 40% and q/p' = 0.8. Initial cell pressure (σ0) significantly influences the flow-slip stability of the specimens. Increased cell pressure enhances the stability. For σ0 = 50, 100, and 200 kPa, the microbial-treated specimens lose their stability when the mean effective stresses equal to 24.54, 75.24, and 154.55 kPa, respectively. The increased cell pressure leads to a longer stable stress path, indicating that the specimens are more stable under the condition of high cell pressures. There is only one destabilization line for each group of specimens across different initial cell pressures, consistent with the test results of Daouadji et al. (2010). For the same group of specimens under constant shear stress paths, destabilization occurs independently of the initial cell pressure.

|

Fig. 9 Effective stress path curves of microbial-treated specimens with different initial cell pressures. |

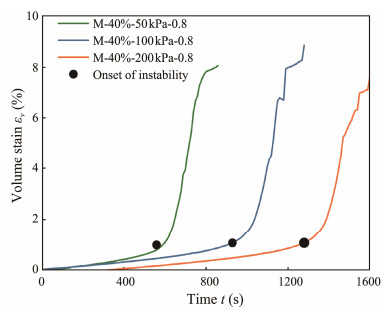

Fig.10 shows the variation of volumetric strain over time with different initial cell pressures under the conditions of Dr = 40% and q/p' = 0.8. Microbial-treated specimens with σ0 = 50, 100, and 200 kPa lose stability at 560, 930, and 1310 s, with corresponding tolerated volumetric strains of 0.98%, 1.05%, and 1.19%, respectively. This is because higher initial cell pressures result in a reduced void ratio and denser particle arrangement. The particles' movement is restricted, enabling the specimens to withstand larger strains without damage. Therefore, under high cell pressure conditions, specimens require more time to reach instability and the specimen can withstand greater volumetric strain. This phenomenon indicates that under high lateral stress conditions, the stability of calcareous sand slopes is higher. This is consistent with the observation that the sliding surface of calcareous sand landslides rarely occurs in deeper soil layers.

|

Fig. 10 Volumetric strain curves of microbial-treated specimens with different initial cell pressures. |

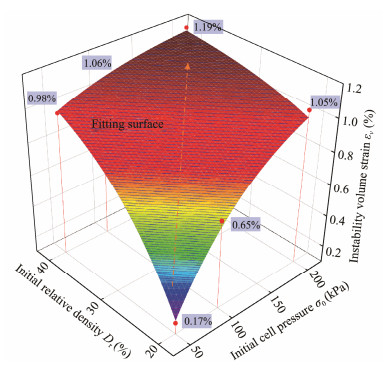

The magnitude of volumetric strain at instability indicates the effectiveness of microbial treatment. The greater the volumetric strain that the specimen can withstand, the more effective the microbial treatment. Fig.11 shows the evolution of the volumetric strain with initial cell pressure and initial relative density during instability. Calcareous sands tend to undergo greater volumetric strain because of microbial treatment with increased density or cell pressure. Analysis shows that the maximum volumetric strain that the specimen can withstand is 1.19% when the initial cell pressure is 200 kPa, and the initial relative density is 40%. Initial relative density significantly affects volumetric strain during instability at low cell pressures but has minimal effect at high cell pressures.

|

Fig. 11 Evolution of volumetric strain during instability with initial cell pressure and initial relative density. |

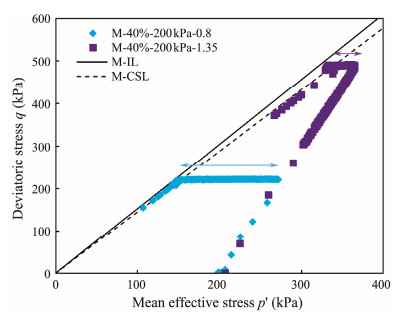

Fig.12 illustrates the effective stress path of microbial-treated specimens with different initial shear stress ratios under the conditions of Dr = 40% and σ0 = 200 kPa. The initial stress ratio (q/p') significantly affects the flow-slip stability of calcareous sand slopes. When q/p' = 0.8, the onset of constant shear stress is located outside the unstable region. When q/p' = 1.35, the onset of constant shear stress is located near the unstable region. Higher initial stress ratios shorten the stable stress path, causing the specimen to enter the unstable zone more quickly, resulting in rapid flow-sliding instability.

|

Fig. 12 Effective stress path curves of microbial-treated specimens with different initial shear stress ratios. |

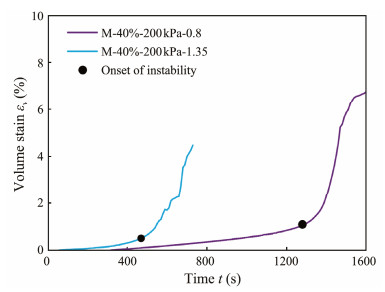

Fig.13 shows the volumetric strain of microbial-treated specimens with different initial shear stress ratios under the conditions of Dr = 40% and σ0 = 200 kPa. The time to reach instability and the critical volumetric strain tend to decrease as the initial stress ratio increases. Compared with q/p' = 1.35, the time required for the onset of instability increases from 470 to 1290 s, and the volumetric strain at the onset of instability increases from 0.52% to 1.10% for specimens with q/p' = 0.8. The above phenomenon is due to the small constant shear stress, which has a trivial shear effect on the specimens. As pore pressure increases, the specimens can maintain stability longer and thus can withstand larger volumetric strains.

|

Fig. 13 Volumetric strain curves of microbial-treated specimens with different initial shear stress ratios. |

Fig.14 presents representative selections of SEM micrographs that highlight key morphological changes induced by the MICP technique in calcareous sand, which contribute to enhanced stability. Fig.14a shows many irregular voids on the surface of calcareous sand particles, making them easier to move, rotate, and re-arrange under external stresses. Fig.14b shows cracks due to the brittle nature of the calcareous sands. According to Xiao et al. (2017), compared with specimens with higher relative density, those with lower relative density are more prone to rupture, with larger particle-to-particle pores. However, microbial-induced calcium carbonate precipitation may not fill the pores or form structures with strong cementation. This is the reason specimens with lower initial relative density in Section 4.2 have unstable internal structures and are susceptible to flow-slip damage.

|

Fig. 14 SEM image of untreated sands and microbial-treated sands. (a), T = 0, irregular holes and pores; (b), T = 0, particle breaking; (c), T = 1, cemented by CaCO3; (d), T = 1, coated with a mass of CaCO3; (e), T = 1, hole filling; (f), T = 1, CaCO3 crystals. |

Figs.14c – e show that microbially induced calcium carbonate crystals are deposited on particle surfaces. CaCO3 is generated on the surface of the sand grains. CaCO3 also fills in between the sand grains, bonding loose sand grains together. Some calcium carbonate crystals fill and reduce the pores inside the calcareous sand grains. It enhances the strength and stability of calcareous sands. Weak cementation between the sand particles and CaCO3 causes the sample to break down first under flow-slip stresses. Shear-induced relative displacement then destroys surface-deposited CaCO3, exposing damaged particle surfaces. Without MICP treatment, the rapid development of relative sliding surfaces causes the specimen to lose stability. Fig.14f shows that microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitate forms granular regular crystals. These interlocking crystals prevent the sand particles from moving, slipping, and tumbling. As a result, the shear strength is enhanced. This clarifies why microbial-treated sand specimens take longer to reach instability and exhibit greater anti-slip stability.

5 ConclusionsIn this study, the GDS standard stress path triaxial system was utilized to conduct the CSD tests to reveal the mechanism of microbial treatment-induced stability enhancement in calcareous sands against flow slides. The main conclusions are as follows:

1) Under the same test conditions, the microbial-treated specimen (T = 1) had a longer stress path to remain stable, took longer to lose stability, and withstood a larger volumetric strain. This finding indicates that the microbial treatment effectively improves the stability of sandy slopes under constant shear drainage conditions.

2) The stability of microbial-treated calcareous sands under flow-sliding stress depends on the initial relative density (Dr), initial cell pressure (σ0), and shear stress ratio (q/p') of the specimen.

3) The initial relative density of the specimen dominates its critical state. The initial cell pressure and initial stress ratio have a minimal effect on the final critical state.

4) The microbial-treated calcareous sand particles were encapsulated and cemented by CaCO3 crystals, which fill the voids among particles. This increases the shear strength of the specimen, thereby enhancing its capacity against flow slides.

AcknowledgementsWe would like to acknowledge gratefully that the work presented in this paper is supported by the Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province, China (No. tsqn202306 098). This research is also supported by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (No. 52171282), and the Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Plan, China (No. 2021ZLGX04).

Arboleda-Monsalve, L. G., Zapata-Medina, D. G., and Galeano-Parra, D., 2019. Compressibility of biocemented loose sands under constant rate of strain, loading, and pseudo K0-triaxial conditions. Soils and Foundations, 59(5): 1440-1455. DOI:10.1016/j.sandf.2019.06.008 (  0) 0) |

Castro, G., 1975. Liquefaction and cyclic mobility of saturated sands. Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, 101(6): 551-569. DOI:10.1061/AJGEB6.0000173 (  0) 0) |

Chek, A., Crowley, R., Ellis, T. N., Durnin, M., and Wingender, B., 2021. Evaluation of factors affecting erodibility improvement for MICP-treated beach sand. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 147(3): 04021001. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0002481 (  0) 0) |

Choi, S., Chu, J., and Kwon, T., 2019. Effect of chemical concentrations on strength and crystal size of biocemented sand. Geomechanics and Engineering, 17(5): 465-473. (  0) 0) |

Chou, C. W., Seagren, E. A., Asce, A. M., Aydilek, A. H., Asce, M., and Lai, M., 2011. Biocalcification of sand through ureolysis. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 137(12): 1179-1189. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000532 (  0) 0) |

Chu, J., Leong, W. K., Loke, W. L., and Wanatowski, D., 2012. Instability of loose sand under drained conditions. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 138(2): 207-216. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000574 (  0) 0) |

Daouadji, A., AlGali, H., and Darve, F., 2010. Instability in granular materials: Experimental evidence of diffuse mode of failure for loose sands. Journal of Engineering Mechanics, 136(5): 575-588. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0000101 (  0) 0) |

DeJong, J. T., Mortensen, B. M., Martinez, B. C., and Nelson, D. C., 2010. Bio-mediated soil improvement. Ecological Engineering, 36(2): 197-210. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.12.029 (  0) 0) |

DeJong, J. T., Soga, K., Kavazanjian, E., Burns, S. E., and Van Paassen, L. A., 2013. Biogeochemical processes and geotechnical applications: Progress, opportunities and challenges. Geotechnique, 63(4): 287-301. DOI:10.1680/geot.SIP13.P.017 (  0) 0) |

Guo, L., Wang, B., Guo, J., Guo, H., Jiang, Y., Zhang, M., et al., 2024. Experimental study on improving hydraulic characteristics of sand via microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Geomechanics for Energy and the Environment, 37: 100519. DOI:10.1016/j.gete.2023.100519 (  0) 0) |

Hang, L., Gao, Y., He, J., and Chu, J., 2019. Mechanical behaviour of biocemented sand under triaxial consolidated undrained or constant shear drained conditions. Geomechanics and Engineering, 17(5): 497-505. (  0) 0) |

Hang, L., Gao, Y., Van Paassen, L. A., He, J., Wang, L., and Li, C., 2022. Microbially induced carbonate precipitation for improving the internal stability of silty sand slopes under seepage conditions. Acta Geotechnica, 18(5): 2719-2732. (  0) 0) |

He, J., Fang, C., Mao, X., Qi, Y., Zhou, Y., Kou, H., et al., 2022. Enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation for the protection of earthen dikes and embankments under surface runoff: Laboratory investigations. Journal of Ocean University of China, 21(2): 306-314. DOI:10.1007/s11802-022-4821-9 (  0) 0) |

Ivanov, V., and Chu, J., 2008. Applications of microorganisms to geotechnical engineering for bioclogging and biocementation of soil in situ. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 7(2): 139-153. DOI:10.1007/s11157-007-9126-3 (  0) 0) |

Kim, J. S., Lee, I. M., Jang, J. H., and Choi, H., 2009. Groutability of cement-based grout with consideration of viscosity and filtration phenomenon. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics, 33(16): 17711797. (  0) 0) |

Kou, H., He, X., Li, Z., Fang, W., Zhang, X., An, Z., et al., 2023. Effect of drying-wetting cycles on the durability of calcareous sand reinforced by MICP and recycled shredded coconut coir (RSC). Biogeotechnics, 1(3): 100038. DOI:10.1016/j.bgtech.2023.100038 (  0) 0) |

Kou, H., Liu, J., Zhang, P., Wu, C., Ni, P., and Wang, D., 2022. Ecofriendly improvement of coastal calcareous sandy slope using recycled shredded coconut coir (RSC) and bio-cement. Acta Geotechnica, 17(12): 5375-5389. DOI:10.1007/s11440-022-01560-2 (  0) 0) |

Lade, P. V., 1992. Static instability and liquefaction of loose fine sandy slopes. Journal of Geotechnical Engineering – ASCE, 118(1): 51-71. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9410(1992)118:1(51) (  0) 0) |

Leroueil, S., 2001. Natural slopes and cuts: Movement and failure mechanisms. Geotechnique, 51(3): 197-243. DOI:10.1680/geot.2001.51.3.197 (  0) 0) |

Li, Y., Guo, Z., Wang, L., and Yang, H., 2023a. A coupled biochemo-hydro-wave model and multi-stages for MICP in the seabed. Ocean Engineering, 280: 114667. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.114667 (  0) 0) |

Li, Y., Li, Y., Guo, Z., and Xu, Q., 2023b. Durability of MICP-reinforced calcareous sand in marine environments: Laboratory and field experimental study. Biogeotechnics, 1(2): 100018. DOI:10.1016/j.bgtech.2023.100018 (  0) 0) |

Lin, H., Suleiman, M. T., Brown, D. G., and Kavazanjian, E., 2016. Mechanical behavior of sands treated by microbially induced carbonate precipitation. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 142(2): 04015066. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001383 (  0) 0) |

Liu, H., Chu, J., and Kavazanjian, E., 2023. Biogeotechnics: A new frontier in geotechnical engineering for sustainability. Biogeotechnics, 1(1): 100001. DOI:10.1016/j.bgtech.2023.100001 (  0) 0) |

Liu, L., Liu, H., Stuedlein, A. W., Evans, T. M., and Xiao, Y., 2019. Strength, stiffness, and microstructure characteristics of biocemented calcareous sand. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 56(10): 1502-1513. DOI:10.1139/cgj-2018-0007 (  0) 0) |

Liufu, Z., Yuan, J., Shan, Y., Cui, J., Tong, H., and Zhao, J., 2023. Effect of particle size and gradation on compressive strength of MICP-treated calcareous sand. Applied Ocean Research, 140: 103723. DOI:10.1016/j.apor.2023.103723 (  0) 0) |

Montoya, B. M., and DeJong, J. T., 2015. Stress strain behavior of sands cemented by microbially induced calcite precipitation. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 141(6): 04015019. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001302 (  0) 0) |

O'Donnell, S. T., and Kavazanjian, E., 2015. Stiffness and dilatancy improvements in uncemented sands treated through MICP. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 141(11): 02815004. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001407 (  0) 0) |

Roksana, K., Hewage, S. A., Lomboy, M. M., Tang, C., Xue, W., and Zhu, C., 2023. Desiccation cracking remediation through enzyme induced calcite precipitation in fine-grained soils under wetting drying cycles. Biogeotechnics, 1(4): 100049. DOI:10.1016/j.bgtech.2023.100049 (  0) 0) |

Shanahan, C., and Montoya, B. M., 2016. Erosion reduction of coastal sands using microbial induced calcite precipitation. Geo-Chicago 2016. American Society of Civil Engineers, Chicago, 42-51.

(  0) 0) |

Sharma, M., Satyam, N., and Reddy, K. R., 2019. Investigation of various gram-positive bacteria for MICP in Narmada Sand, India. International Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, 15: 220-234. (  0) 0) |

Sharma, M., Satyam, N., and Reddy, K. R., 2021. Rock-like behavior of biocemented sand treated under non-sterile environment and various treatment conditions. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 13(3): 705-716. DOI:10.1016/j.jrmge.2020.11.006 (  0) 0) |

Sharma, M., Satyam, N., and Reddy, K. R., 2022. Comparison of improved shear strength of biotreated sand using different ureolytic strains and sterile conditions. Soil Use and Management, 38(1): 771-789. DOI:10.1111/sum.12690 (  0) 0) |

Van Paassen, L. A., Ghose, R., Der Linden, T. J., Der Star, W. R., and Van Loosdrecht, M. C., 2010. Quantifying biomediated ground improvement by ureolysis: Large-scale biogrout experiment. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 136(12): 1721-1728. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000382 (  0) 0) |

Wang, L., Chu, J., and Wu, S., 2021. Stress-dilatancy behavior of cemented sand: Comparison between bonding provided by cement and biocement. Acta Geotechnica, 16: 1441-1456. DOI:10.1007/s11440-021-01146-4 (  0) 0) |

Whiffin, V. S., Van Paassen, L. A., and Harkes, M. P., 2007. Microbial carbonate precipitation as a soil improvement technique. Geomicrobiology Journal, 24(5): 417-423. DOI:10.1080/01490450701436505 (  0) 0) |

Xiao, P., Liu, H., Xiao, Y., Stuedlein, A. W., and Evans, T. M., 2018. Liquefaction resistance of bio-cemented calcareous sand. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 107: 9-19. DOI:10.1016/j.soildyn.2018.01.008 (  0) 0) |

Xiao, Y., Liu, H., Chen, Q., Ma, Q., Xiang, Y., and Zheng, Y., 2017. Particle breakage and deformation of carbonate sands with wide range of densities during compression loading process. Acta Geotechnica, 12(5): 1177-1184. DOI:10.1007/s11440-017-0580-y (  0) 0) |

2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23