2) College of Chemical Engineering, Hebei Normal University of Science and Technology, Qinhuangdao 066600, China;

3) School of Chemical Engineering, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin 300130, China

Uranium resources are regarded as nuclear power and strategic resource of national defense construction (Yang et al., 2019). Uranium extraction from seawater has been listed as one of the seven chemical separations to change the world (Sholl and Lively, 2016). The mining, separation and enrichment of uranium are of great significance for the sustainable development and long-term exploitation of nuclear energy. Moreover, during nuclear materials production and utilization, waste products have radiochemical and toxicological impact. Thus, the extraction of uranium from aqueous solution and disposal of uranium-contaminated water are imperative in view of limited terrestrial ores and unacceptable environmental cost (Wang et al., 2013; Ji et al., 2017). The adsorption is considered to be a more effective, easy operation, economic and environmental friendly method with high potential for removing uranium from aqueous solution (Mellah et al., 2006; Webb et al., 2006; Jang et al., 2007; Pang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). The high capacity, selective and reusable adsorbents have to be developed for the adsorption process. Compared to other inorganic materials, SBA-15 mesoporous material exhibits perfect performance for uranium uptake owing to its ordered structure, wide channel system, large specific surface area and high hydrothermal stability (Sujandi et al., 2006; Kango et al., 2013). Its high surface silanol densities are deemed to be a potential base support for further functionalization to improve the selectivity and adsorption capacity (Yang et al., 2005; Ojeda-López et al., 2015; Zienkiewicz- Strzałka et al., 2018). Among many functional groups, amidoxime group modified on various struts has received the most attention for uranium capture (Zhao et al., 2014; Bayramoglu and Arica, 2016; Yang et al., 2016; Dai et al., 2017). The acidic and basic ligands incorporated into the scheme of amidoxime group lead to strong binding ability with UO22+ cation. Due to high affinity and selectivity towards U(VI) ions induced by stable coordination, amidoxime group has been utilized for extraction of uranium from aqueous solution.

Chen et al. (2011) have found that the platelet SBA-15 with short channels are superior to the conventional SBA- 15 with rod or fiber morphology in adsorption rate attributing to the smaller possibility of pore-blockage. Our previous studies also showed that the platelet SBA-15 with short channels used as adsorbent or the support of functional adsorbent exhibited higher adsorption capacity than the conventional SBA-15 (Wang et al., 2013; Ji et al., 2017). However, when adsorption equilibrium was reached on the fresh SBA-15 adsorbent, only 80% loaded U(VI) could be eluted after regeneration. The similar phenomenon was also observed in the adsorption study of Yang's group (Ren et al., 2016). Owing to the difficulty in dispersion of uranium ions inside the adsorbent pores which was partially occupied by the loaded uranium ions, the adsorption capacity of regenerated adsorbent was sharply reduced. The amount of effective active sites, adsorption rate and incorporated organic groups are highly dependent on the mesoporous size of materials. Commendable reuse of adsorbent requires efficient uranium stripping without evident degradation and loss of adsorption capacity. Therefore, it is necessary to seek an avenue to adjust the porous size for promising uranium adsorbent. The textural characteristics can be pre-designed through the conceptual selection of enlarging the pore system. Expanded mesopores will decrease the convey resistance in diffusion paths and contributes to the efficient utilization of adsorbent during recycling adsorption-desorption process (Xing et al., 2017). Additionally, the larger pores of adsorbent will benefit for increasing the density of organic functional groups. The mesopores can be enlarged by means of adding co-solvents and co-surfactants to hydrothermal synthesis solution. Wang and Noguchi (Wang et al., 2001) have expanded the diameter of SBA-15 from 3.6–5.5 nm to 8.4–12 nm by combining post-synthesis heat treatment after reaction of triblock co-polymer and tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) in weakly acidic condition with addition of trimethylbenzene (TMB) before reaction. It is reported that TMB as co-surfactant had higher solubility in hydrophobic side of co-polymer surfactant. Furthermore, TMB is easy to obtain and dissociate.

In this paper, pore expanded platelet SBA-15 was synthesized using a facile procedure by adding TMB to short channel platelet SBA-15 synthesis solution. Then the mesoporous structure was analyzed and measured by various characterized methods. Adsorption performance including pH value, contact time and elution rate were studied. Afterwards, amidoxime-functionalization on pore expanded platelet SBA-15 was implemented and characterized.

2 Materials 2.1 MaterialsTetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) and ZrOCl·8H2O were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical reagent Co., Ltd. Trimethylbenzene (TMB) was purchased from Shanghai Kefeng Industry & Commerce Co., Ltd. Poly(ethylene oxide)-block-poly(propylene oxide)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) triblock copolymer (EO20PO70EO20, P123, Mavg = 5800) was provided by Sigma-Aldrich. Other agents used here are of AR grade as received.

2.2 Synthesis of Short Channel Platelet SBA-15 and Pore Expanded Platelet SBA-15The short channel platelet SBA-15 particles were synthesized as following: 0.64 g ZrOCl·8H2O and 4.00 g P123 were di ssolved in 160.00 g HCl solution (2 mol L−1) under stirring. Subsequently, 8.45 g TEOS was added dropwise to above solution, followed by stirring at 35℃ for 22 h, which was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave for aging at 100℃ for 24 h. Then, the product was recovered by filtering and air-dried at 60℃ for 6 h. Finally, the resulting product was calcined at 550℃ for 6 h in air, the product was label as SBA-15.

Besides the addition of TMB, the reactant ratio and synthesis process of pore expanded platelet SBA-15 were same with the above SBA-15.2.00 g TMB was added to the mixed solution after pre-hydrolysis of TEOS for 25 min (Chen et al., 2011). After the addition of TMB, the preparation process was same with the above SBA-15. The resultant product was named as ESBA-15.

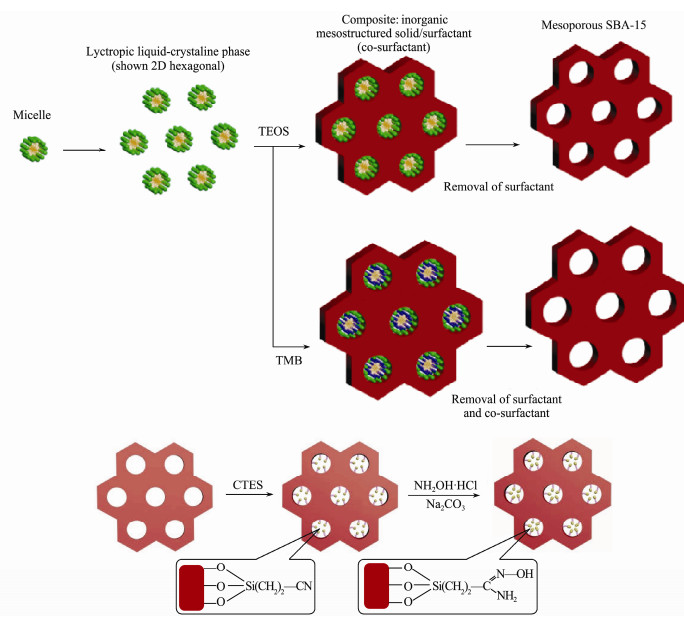

The preparation schematic of SBA-15 and ESBA-15 are shown in the top of Fig. 1.

|

Fig. 1 Formation schematic: SBA-15 and ESBA-15 (top); cyano-functionalized and amidoxime-functionalized composites (bottom). |

SBA-15 and ESBA-15

The amidoxime-functionalized material was prepared by amidoximation reaction between the hydroxylamine and cyano-functionalized material. A schematic presentation of the synthesis is given in the bottom of Fig. 1. The specific steps are described as below (Ji et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019):

Step 1: Cyano-functionalization

The cyano-functionalized material prepared by postgrafting method was obtained by refluxing of pristine material SBA-15 or ESA-15 (1.0 g) and 2-cyanoethyltriethoxysilane (CTES, 4.35 g) in dry toluene (60 mL) for 12 h under N2 atmosphere at 110℃. After suction filtration, the product was washed with methanol and dried in oven at 60℃.

Step 2: Amidoxime-functionalization

In the typical procedure, 3.56 g hydroxylamine hydrochloride was dissolved with 22 mL deionized water in a three-neck boiling flask under N2 atmosphere. 2.72 g anhydrous sodium carbonate was added and completely dissolved into the flask, and 1.0 g cyano-functionalized material was then added to the homogeneous solution. The reactant mixture was stirred at 70℃ under N2 atmosphere for 3 h, the product was filtered and washed with deionized water until the filtrate did not decolorize KMnO4, and was dried in vacuum at 60℃ for 12 h.

2.4 Adsorption ExperimentsThe performances of adsorbents were studied under a series of adsorption conditions. The concentration of the free U(VI) ions was measured on UV-spectrophotometer (Shanghai Metash Instruments Co., Ltd., UV-5500PC). Adsorption capacity Qt (mg-U g−1) and equilibrium adsorption capacity Qe (mg-U g−1) were calculated by using the following equations (Ji et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019):

| $ {Q_t} = \frac{{{C_0} - {C_t}}}{m} \times V, $ | (1) |

| $ {Q_e} = \frac{{{C_0} - {C_{\rm{e}}}}}{m} \times V, $ | (2) |

where, C0 (mg L−1) is initial uranium concentration, Ct (mg L−1) and Ce (mg L−1) are the uranium concentration at time t and equilibrium time, V (L) is bulk of adsorption solution, m (g) is the mass of adsorbents.

2.5 Desorption ExperimentsThe adsorbent particles loaded with U(VI) were filtered and gently washed with deionized water. Then, the adsorbent particles were eluted by 2 mol L−1 HNO3 solution for 2 h under magnetic stirring at ambient temperature. The adsorbent particles were regenerated by filtering and washing to neutral. Elution rate E (%) was calculated as following:

| $ E(\%) = \frac{{{\rm{Mass of U(VI) desorbed}}}}{{{\rm{Mass of U(VI) adsorbed}}}} \times 100\% . $ | (3) |

The morphology of the samples was characterized by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, S-4800 and SU8010, Hitachi, Japan). Transmission electron microscope (TEM) image was obtained using TECNAI G2 F20 microscope. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra were carried on Tensor27 FTIR spectrometer. Powder X-ray diffraction pattern was recorded on the Rigaku D/MAX 2500 powder diffraction system using Cu Kα radiation. X-ray photoelectron spectra measurement was performed with an ESCALAB 250Xi spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer, USA) with a monochromated Al-Kα X-ray source (hv = 1486.6 eV). N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms were carried out by Micromeritics ASAP2020. The specific surface areas and pore size distributions were respectively calculated using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method and Barret-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) model on the desorption process. Thermogravimetric analysis was conducted on Mettler TGA/DSC 3+ Thermal Gravimetric Analyzer under the following operational conditions: the samples were heated from ambient temperature to 1000℃ with a ramp rate of 6℃ min−1 in the presence of purified nitrogen. Elemental analysis was carried out by Elementar Vario PE2400 apparatus.

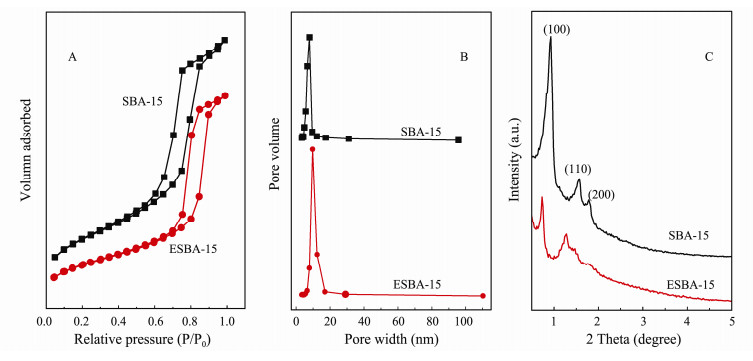

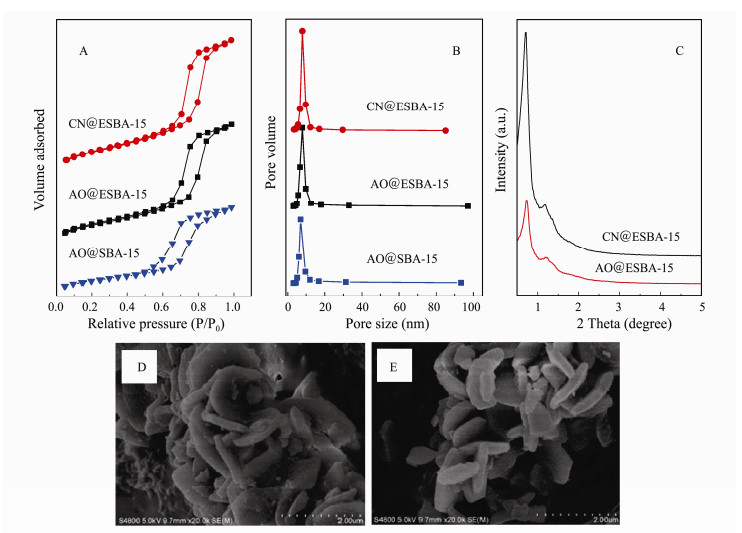

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 Characterization of SBA-15 and ESBA-15Figs. 2(A, B) reveals the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and the corresponding pore size distribution curves of SBA-15 and ESBA-15. As shown in Fig. 2(A), the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of both SBA-15 and ESBA-15 confirm to type-IV with H1 hysteretic loops according to IUPAC classification. The results demonstrate that the prepared SBA-15 and ESBA-15 possess mesopores with uniform and narrow pore size distribution proved by the pore size distribution curves (Fig. 2(B)). The hysteretic loop of ESBA-15 shifted to higher P/P0 than SBA-15, indicating the pore size of ESBA-15 is larger than SBA-15. The pore structure parameters are listed in Table 1 according to BET method and BJH model. The pore size and pore volume of ESAB-15 are clearly higher than SBA-15, achieving 9.75 nm and 1.15 cm3 g−1. The pore size and volume increased by 23.57% and 22.34% respectively, displaying that mesopores of SBA-15 can be indeed enlarged by means of adding TMB co-surfactant.

|

|

Table 1 Results of physicochemical properties of platelet SBA-15 and ESBA-15 |

|

Fig. 2 N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms (A), pore size distribution curves (B) and X-ray diffraction patterns (C) of synthesized SBA-15 and ESBA-15. |

Fig. 2(C) indicates the powder small-angle XRD patterns of SBA-15 and ESBA-15. As shown in Fig. 2(C), one intense peak (0.93˚) and two weak peaks (1.57˚ and 1.79˚) are observed in SBA-15 corresponding to the (100), (110) and (200) reflections of a two-dimensional hexagonal p6mm symmetry. The typical diffraction peaks imply the well-ordered mesoporous structure of SBA-15. Meanwhile, three diffraction peaks still appear in ESBA- 15, suggesting that the sample maintain highly ordered mesochannels after pore expanded with TMB. Additionally, the positions of peaks slightly shift to lower angles, which are attributed to the increased pore size after adding swelling agent in the prepared sample. The (110) reflection is weaker for the ESBA-15 which could indicate thicker walls as demonstrated by Feuston and Higgins (1994). The wall thickness calculated from XRD data by Bragg equation, is 4.03 nm for ESBA-15, and 3.20 nm for SBA-15 (Table 1), indicating high framework stability. As outlined in scheme (Fig. 1), both the pore size and wall thickness are extended by the addition of nonpolar molecule TMB. The mechanism of the expanding effect is that: the nonpolar organic molecular added in the surfactant aqueous solution has swollen the micelle due to the solubilization. TMB molecules could penetrate into the hydrophobic part of the micelle center, resulting in increase of apparent diameter and volume of micelle which cause the increased pore diameter of the materials. During the formation of larger micelles, the gap between the micelles could be expanded, which is reasonable for the increase of wall thickness.

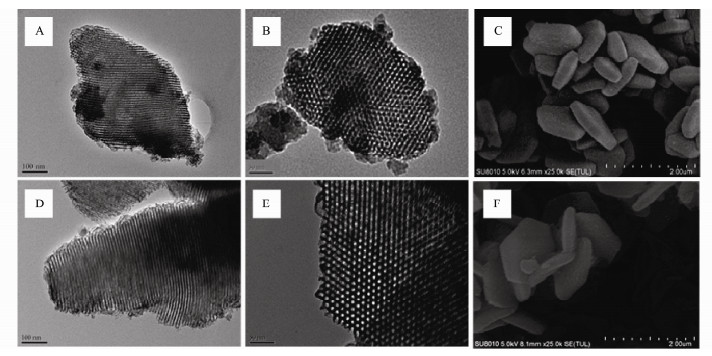

Figs. 3(A, D) are viewing normal to the pore axis and Figs. 3(B, E) are along the pore axis. As can be observed in TEM images, SBA-15 and ESBA-15 present well-ordered and uniform mesopores arranged in a 2D hexagonal p6mm, noting that ESBA-15 maintains the highly ordered mesoporous structure and no mesopore collapse. The SEM images of the SBA-15 and ESBA-15 samples are shown in Figs. 3(C, F). It can be seen that the morphology of ESBA-15 exhibits platelet-like shape similar with SBA-15. This confirms that TMB has little influence on the morphology and pore structure. The abovementioned information demonstrates that the pore size of well-developed sample successfully enlarged by adding TMB and the platelet-like morphology and well-ordered 2D hexagonal mesoporous structure are maintained.

|

Fig. 3 TEM images of SBA-15 (A, B) and ESBA-15 (D, E); SEM images of SBA-15 (C) and ESBA-15 (F). |

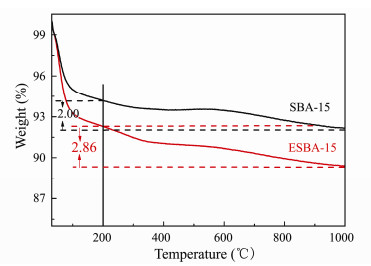

The effective adsorption of the pristine adsorbent on uranium ions is achieved through coordination with silanol. Moreover, the grafting of functional groups onto the support is realized through the reaction of organosilanes with the silanol on the surface. Although above results of SEM, TEM and XRD demonstrate that the texture of the material after pore-expanded is optimized, the change of silanol amount on the surface of the material remains undetermined. Thus, the silanol densities on SBA-15 and ESBA-15 samples were analyzed by thermogravimetry. According to the existing literature (Wang and Yang, 2011; Benamor et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2016), the weight loss below 100℃ and the loss between 100℃ and 200℃ are respectively assigned to the remove of physically adsorbed and chemically adsorbed water. The weight loss above 200℃ mainly belonged to the dehydroxylation by the condensation of silanols. As shown in Fig. 4, ESBA-15 has a steeper weight loss than SBA-15 below 200℃, indicating that the larger pore channel supports the adsorption of water. Furthermore, the total weight loss above 200℃ of ESBA-15 and SBA-15 is 2.86% and 2.00%, respectively. The weight loss of ESBA-15 is higher than that of SBA-15 above 200℃, confirming that apparently more silanol groups are present on ESBA-15 than SBA-15.

|

Fig. 4 Thermogravity curves of SBA-15 and ESBA-15. |

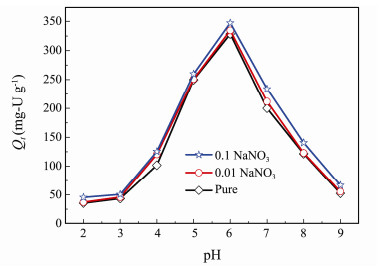

The initial pH has a great impact on the uranium adsorption capacity, which was carried out ranging from 2 to 9. As displayed in Fig. 5, the extracting amount of U(VI) increases with the increase pH of the solution from 2 to 6, and reaches the maximum adsorption at pH = 6. The adsorption capacity subsequently decreases as pH continued to rise from 6 to 9. This might be ascribed to the large quantities of H+ and U(VI) ion hydrolysis in the aqueous solution. Generally, existence of uranium in aqueous solution is six-valence state, thus the separation of uranium from aqueous solution mainly depends on the extraction of U(VI). Furthermore, the existence state of U(VI) in aqueous solution is closely related to the change of pH. At low pH (pH < 4), UO22+ ion is the dominant species. The low adsorption capacity can be explained that H+ and H3O+ compete with U(VI) on the adsorption sites on the surface of adsorbent. What's more, H+ causes protonation of adsorbent and increases the adsorbent electrostatic repulsion of U(VI), leading to the reduction of adsorption capacity. When the pH increases to neutral region, U(VI) ion occurs hydrolysis with a complex species, such as UO2(OH)+, (UO2)2(OH)22+ and (UO2)3(OH)5+. The result reduces the amount of H+ and H3O+ and support the U(VI) adsorption on more exposed adsorption sites. As pH value is higher than 8, U(VI) eventually hydrolyzes and forms UO2(OH)3− and (UO2)3(OH)7− ions, and UO2(OH)2 precipitation. The appearance of vast hydroxide products of U(VI) cause the electrostatic repulsion between these anions and the negatively charged adsorbent, as a result, the lower adsorption capacity is obtained (Wang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2014).

|

Fig. 5 Effect of initial pH and ionic strength on U(VI) adsorption by ESBA-15 (C0 = 100 mg-U L−1, V = 100 mL and T = 25℃). |

The effect of ionic strength on U(VI) is also displayed in Fig. 5. The U(VI) adsorption on ESBA-15 exhibits weak ionic strength dependence at all pH values. During the adsorption process, the sensitivity to the ionic strength of inner-sphere complexation is weaker than that of outersphere complexation (Lützenkirchen, 1997; Goldberg, 2005; Yang, 2012; Yang et al., 2020). It was deduced that the dominant mechanism was consistent with inner-sphere surface complexes. As the pore channel of the mesoporous silica was broadened, it is beneficial to exert the adsorption activity of the inner site of the adsorbent.

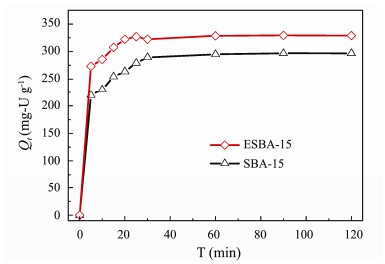

3.3 Effect of Contact TimeAdsorption rate plays an important role in evaluation the performance of adsorbents. The sorption operation should be as fast as possible in practical application. The effect of contact time on U(VI) adsorption behavior is shown in Fig. 6. When the contact time reached 5 min, the adsorption capacity of ESBA-15 is 270 mg-U g−1, which is 23% higher than SBA-15 (220 mg-U g−1). The equilibrium adsorption of ESBA-15 and SBA-15 are achieved within 20 min and 30 min, with the adsorption capacity of 326 and 297 mg-U g−1, respectively. The ESBA-15 shows relatively faster adsorption rate and higher adsorption capacity than SBA-15. The aforementioned results of BET and TG show that ESBA-15 possesses larger pore size and more silanol groups than that of SBA-15. It is believed that the larger pore size reduces mass transfer resistance and supplies more effective adsorption sites, which contributes to shortening equilibrium adsorption time and enhancing the adsorption capacity.

|

Fig. 6 Effect of contact time on U(VI) adsorption of SBA- 15 and ESBA-15 (C0 = 100 mg-U L−1, pH = 6, V = 100 mL, T = 25℃). |

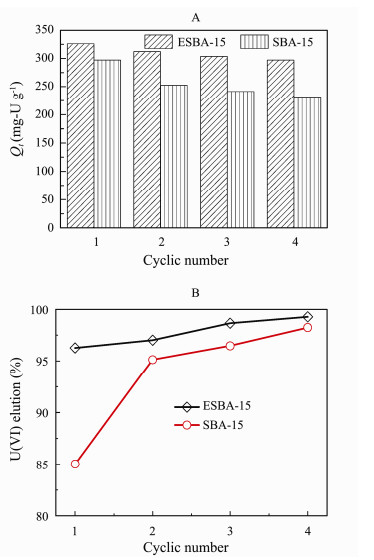

The reusability of adsorbent is an essential index from the perspective of reducing cost and environmental sustainability. Therefore, recycling adsorption performance and elution rate are adopted to evaluate the reusability of SBA-15 and ESBA-15 in U(VI) uptake. Nitric acid (HNO3) was selected as eluent used in regeneration experiments for the elution of loaded U(VI) from adsorbent.

As illustrated in Fig. 7(A), the adsorption capacity of pristine SBA-15 and ESBA-15 is 297 mg-U g−1 and 326 mg-U g−1, respectively. The adsorption capacity of the second cycle for SBA-15 and ESBA-15 after regeneration is 252 mg-U g−1 and 312 mg-U g−1, and the adsorption capacity decreased by 15.2% and 4.3%, respectively. The adsorption capacity of third cycle for SBA-15 and ESBA-15 is 241 mg-U g−1 and 304 mg-U g−1, which reduced by 4.4% and 2.6% compared with the second cycle, respectively. The adsorption capacity of fourth cycle for SBA-15 and ESBA-15 decreased 4.1% and 2.3%, respectively. After four consecutive adsorption and desorption test, the adsorption capacity of SBA-15 pronouncedly decreases from 297 mg-U g−1 to 231 mg-U g−1, while adsorption capacity of ESBA-15 slightly drops from 326 mg-U g−1 to 297 mg-U g−1. The adsorption capacity of ESBA-15 decreased by 8.9% in comparison with the fresh adsorbent far lower than 22.2% reduction of SBA-15. This result is related to high elution rate of regeneration over 96% for the fresh ESBA-15 (Fig. 7(B)), indicating that almost whole attached U(VI) was desorbed. On the contrary, adsorption capacity reduction of fresh SBA-15 was enlarged in the next cycles owing to lower elution rate (about 85%). The elution rate of ESBA-15 still achieved 99% after four times' cycles with higher adsorption capacity of 297 mg-U g−1, implying the impressive stability of adsorbent. This phenomenon can be explained that the larger pore size and pore volume supply more available adsorption sites and facilitated the elution of attached U(VI) from adsorbent. The ESBA-15 can conduce to continuous utilization in the recovery of U(VI) from aqueous medium with low renewal cost.

|

Fig. 7 Reusability performance (A) and elution rate (B) of SBA-15 and ESBA-15 (Experimental conditions for the reusability in Fig.A: C0 = 100 mg-U L−1, pH = 6, V = 100 mL, t = 7 h, T = 25℃; elution condition in Fig.B: CHNO3 = 2 mol L−1, t = 2 h). |

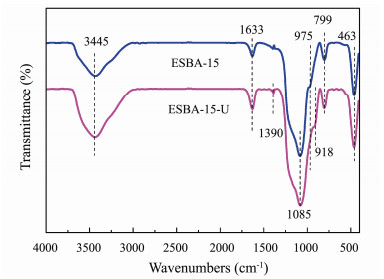

Fig. 8 shows FTIR absorbance peaks of ESBA-15 before and after adsorption of U(VI). The absorption peaks situate at 799 cm−1, 1085 cm−1 and 463 cm−1 belongs to symmetric, asymmetric stretching and bending vibration and of Si-O-Si respectively (Kamari et al., 2009). The wide and strong absorption band at 3445 cm−1 is ascribed to stretching vibrations of hydro-bonded silanol group perturbed by physically adsorbed water in ESBA-15. A shoulder-like band that appears at 975 cm−1 represents vibration of Si-OH (Yuan et al., 2012). The absorption peak at 1633 cm−1 is attributed to the inplane bending vibration of Si-OH (Guo et al., 2013). After the adsorption of uranium, some bands (918 cm−1 and 1390 cm−1) appeare in FTIR spectrum of ESBA-15-U while the band of 975 cm−1 weakens. The band located at 918 cm−1 is attributed to asymmetric vibration of ν3UO22+ (Li et al., 2014). The characteristic peaks at 1390 cm−1 is assigned to the formation of U-OH group. These results demonstrate the chemisorption of uranium on adsorbent ESBA-15, which mainly relies on Si-OH group.

|

Fig. 8 The FTIR spectra of ESBA-15 and ESBA-15. |

Mesoporous Materials

The removal performance including adsorption capacity (qmax) and the required equilibrium time play an important role in application potential of an adsorbent. The prepared ESBA-15 presented a higher adsorption capacity and shorter equilibrium time than those U(VI) adsorption on other inorganic materials listed in Table 2. The excellent property of ESBA-15 is due to platelet-like morphology, short channel pore structure and expanded pore size.

|

|

Table 2 Comparison of U(VI) adsorption capacity of ESBA-15 with reported adsorbents |

Functionalized ESBA-15 3.7.1 Structural and texture characterization

The content of C, H and N in the modified SBA-15 and ESBA-15 samples was determined by elemental analysis. The C and N elements contained in cyano-functionalized material should be attributed to cyanoethyl group. After amidoximation reaction, the content of C and H elements decrease distinctly while the content of N element increases apparently. Therefore, N element was selected to express the functionalized characteristic element. Grafting rate (mmol g−1) of –CN group was calculated by Eq. (4) (Wang et al., 2014):

| $ G = \frac{{{n_{{\rm{CN}}}}}}{{{m_{{\rm{CN}}@{\rm{SBA - }}15}}}} \times 1000, $ | (4) |

where, nCN is the molar mass of –CN group, mCN@SBA-15 is the mass of material.

The detailed calculation method of grafting rate for –AO group (mmol g−1) was given as follows:

| $ \frac{{\left({{n_{{\rm{CN}}}} + {n_{{\rm{AO}}}}} \right) \times 14}}{{{m_{{\rm{AO@SBA - 15}}}}}} = {N_{{\rm{AO}}}}({\rm{wt\%)}}, $ | (5) |

| $ \frac{{{n_{{\rm{CN}}}} \times 14}}{{{m_{{\rm{AO@SBA - 15}}}} - {n_{{\rm{AO}}}} \times 33}} = {N_{{\rm{CN}}}}({\rm{wt}}\%), $ | (6) |

| $ G = \frac{{{n_{{\rm{AO}}}}}}{{{m_{{\rm{AO@SBA - 15}}}}}} \times 1000, $ | (7) |

where, NCN and NAO are mass fraction of N element, nCN and nAO are the molar mass of –CN group and –AO group, mAO@SBA-15 is set as 1 g. During calculation, the nAO is quantified by solving simultaneous equations of (5) and (6).

As listed in Table 3, the content of –CN on the CN@ESBA-15 is 7% higher than that of CN@SBA-15, which is due to the enlarged pore and more silanol groups on ESBA-15 allowing to graft more CTES. Compared with AO@SBA-15, the content of –AO group for AO@ESBA-15 increased more than 55%, attributing to the more –CN grafting amount and expanded pore allowing more –CN groups deep in the pore to transform into –AO group. From the above results, it can be concluded that the expanded mesoporous materials can effectively increase the grafting amount of functional groups on the materials.

|

|

Table 3 Elements analysis of functionalized mesoporous silica composites by post-grafting |

The changes of mesoporous structure and textural properties after modification were analyzed using the nitrogen adsorption-desorption test. The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and corresponding pore size distribution curves of CN@ESBA-15, AO@ESBA-15 as well as AO@SBA-15 are displayed in Fig. 9.

|

Fig. 9 N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms (A) and pore size distribution curves (B), X-ray diffraction patterns (C), SEM images of CN@ESBA-15 (D) and AO@ESBA-15 (E). |

As presented in Fig. 9(A), isotherms obtained for all the samples exhibits typical type IV with H1 hysteretic loops according to the IUPAC classification. This characteristic belongs to mesoporous materials with uniform pore size and narrow pore size distributions (Fig. 9(B)). The calculated BET specific surface area, pore size and pore volume are listed in Table 4. It is found that all the values of CN@ESBA-15 evidently diminish compared with ESBA- 15 (Table 1), which is attributed to the occupation of grafted –CN groups on the surface and inner space onto the mesoporous framework. The pore size, specific surface area and pore volume of AO@ESBA-15 are distinctly larger than AO@SBA-15. The results show that the excellent pore expanded modification can effectively retain higher specific surface area and pore volume of the materials after grafting organic groups, which could provide a larger space for U(VI) adsorption.

|

|

Table 4 Data of physicochemical properties of samples |

Fig. 9(C) shows powder small-angle XRD patterns of CN@ESBA-15 and AO@ESBA-15. The intense diffraction peak in the region of 2θ = 0.7-0.8˚ and weak peaks located at 2θ = 1.1-1.3˚ corresponding to the (100), (110) and (200) crystallographic planes can be distinguished in the samples, indicating the ordered mesoporous structures of two-dimensional hexagonal symmetry. Figs. 9(D, E) reveals the morphological message for CN@ESBA-15 and AO@ESBA-15, determined by SEM images. After incorporation of –CN and –AO groups, the samples still present regular hexagonal platelet-like nanoparticles with a height of 200 nm and a diameter of 1-1.5 μm similar with the unmodified ESBA-15 (Fig. 3(F)). This validates that the modification has little influence on mesoporous structure. It exhibits that pore expanded SBA-15 is stable after post-grafting of the –CN groups and followed by amidoxime functionalization.

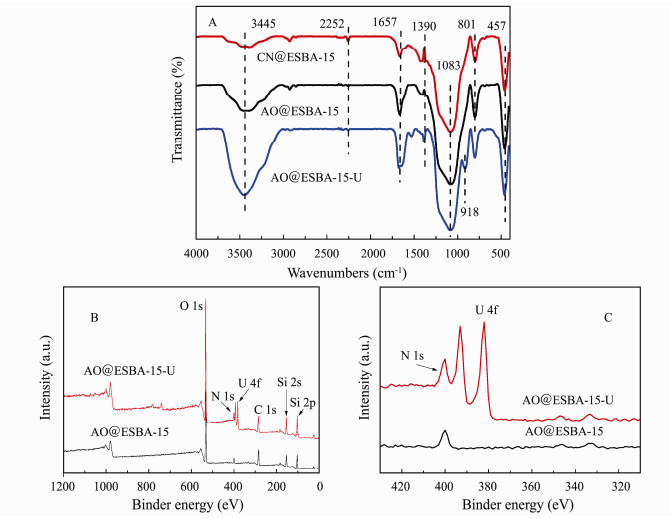

3.7.2 A nalysis of FTIR and XPSFig. 10(A) shows the FTIR spectra of CN@ESBA-15, AO@ESBA-15 and AO@ESBA-15 loaded with U(VI) (AO@ESBA-15-U). The spectra of modified products reserve the characteristic peak of substrate. The typical intense bands at 801 cm−1 and 1083 cm−1 are assigned to asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibration of Si-O-Si and Si-O-H, and 457 cm−1 is ascribed to bending mode vibration of O-Si-O. Compared with pure ESBA-15 (Fig. 8), the characteristic peak of CN@ESBA-15 located at 2251 cm−1 is attributed to stretching vibration of cyano groups (–C≡N). While the broad adsorption band around 3445 cm−1 notably decreases, demonstrating that the cyano groups are anchored on the surface by means of silanol groups. The weakened band of cyano groups is obviously displayed in the spectrum of AO@ESBA-15. Meanwhile, the strong absorption peak at 1657 cm−1 is relevant to the stretching vibration of –C=N bond. Additionally, the adsorption band of AO@ESBA-15 around 3445 cm−1 become broader and intense, which might be caused by vibration of –OH and –NH2 groups belonged to amidoxime groups. The results confirm that a large number of cyano groups have been converted to amidoxime groups by amidoximation reaction.

|

Fig. 10 The FTIR spectra (A) of CN@ESBA-15, AO@ESBA-15 and AO@ESBA-15-U; the whole range XPS spectra (B, C) of AO@ESBA-15 and AO@ESBA-15-U. |

As shown in FTIR spectrum of AO@ESBA-15 loaded with uranium (AO@ESBA-15-U), two new adsorption bands appear at 918 cm−1 and 1390 cm−1, which correspond to the asymmetric vibration peak of ν3 UO22+ and the formation of U-OH bonds, respectively. Therefore, it can be assumed that uranium binding are performed through chemical absorption onto AO@ESBA-15.

In order to further understand the adsorption process for U(VI) ions on AO@ESBA-15, XPS spectra were conducted to analyze the adsorption mechanism after the load of U(VI). As expected, the corresponding peaks of C 1s, N 1s and O 1s appear at binder energy of 485-550 eV in the survey spectra after adsorption (Fig. 10(B)). Furthermore, two new characteristic peaks of uranium appear at 381.88 eV and 392.73 eV after U(VI) uptake (Fig. 10(C)), evidencing the successful adsorption of U(VI) (Kowal-Fouchard et al., 2004; Schindler et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2015; Yin et al., 2020).

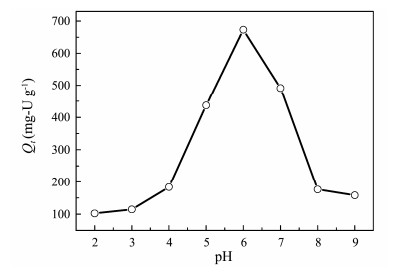

3.7.3 Effect of pHThe pH value of aqueous solution which is a significant indicator for adsorption study influences speciation of metal ions, surface charge and adsorption sites to a great degree. Here, U(VI) adsorption on AO@ESBA-15 as a function of pH ranging from 2 to 9 was performed to evaluate the effect. As shown in Fig. 11, the adsorption capacity on U(VI) rapidly ascends when the augmentation of pH ranged from 2 to 6. The adsorption capacity reaches 674 mg-U g−1 at pH = 6, whereas U(VI) adsorption sharply reduces with pH higher than 6. Similar behavior for the pH effect has also been found by other researchers (Bryant et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003). They provided the analysis of the trend: amidoxime groups can form a bidentate coordination system with UO22+ ions. The lone pair of electrons on the oxime group and amino groups are donated to form a five-ring complex between the positively charged uranyl ion centers and amidoxime groups. Oxygen bond of oxime is protonated under the action of metals:

| $ {\rm{R - C(N}}{{\rm{H}}_{\rm{2}}}{\rm{)N - OH}} \leftrightarrow {\rm{R - C(N}}{{\rm{H}}_{\rm{2}}}{\rm{)N - }}{{\rm{O}}^{\rm{ - }}}{\rm{ + }}{{\rm{H}}^{\rm{ + }}}{\rm{, }} $ | (8) |

| $ {\rm{2R - C(N}}{{\rm{H}}_{\rm{2}}}{\rm{)N - }}{{\rm{O}}^{\rm{ - }}}{\rm{ + UO}}_2^{{\rm{2 + }}}{\rm{U}}{{\rm{O}}_{\rm{2}}}{{\rm{(R - C(N}}{{\rm{H}}_{\rm{2}}}{\rm{)N - O)}}_{\rm{2}}}, $ | (9) |

|

Fig. 11 Effect of initial pH on U(VI) adsorption by AO@ ESBA-15 (C0 = 100 mg-U L−1, V = 100 mL, T = 25℃). |

At lower pH, amino groups and hydroxyl groups of oxime groups on the grafted amidoxime groups are highly protonated and positively charged, resulting in weak affinity to UO22+ (the main existence form of U(VI)). As the pH value increase, H+ in the aqueous solution is neutralized, leading to deprotonation of binding sites on adsorbent. Then, the positively charged U(VI) ions coordinate with functionalized groups along with waning electrostatic repulsion. When pH value is higher than 8, multi- U(VI) hydrolysis species, which can not coordinate with binding site, such as UO2(OH)3− and (UO2)3(OH)7−, are the dominant formed complexes. The electrostatic repulsion is generated with the negatively charged adsorbent, reducing the adsorption capacity. The adsorption capacity of AO@ESBA-15 is significantly higher than that of pure silica ESBA-15 materials at different pH values, indicating that grafted amidoxime groups possess strong affinity with U(VI).

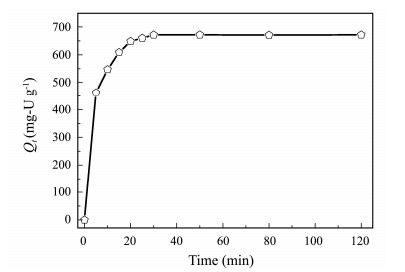

3.7.4 Effect of contact timeThe adsorption capacity of U(VI) on AO@ESBA-15 as function of the contact time is depicted in Fig. 12. It can be observed that the adsorption of U(VI) on AO@ESBA- 15 increase dramatically at the beginning, with 69% of the equilibrium capacity in the initial 5 min. Then, the adsorption slow down and equilibrium is acquired within 30 min. The above results present that the U(VI) adsorption process is very fast, which is mainly caused by strong coordination between amidoxime group and U(VI) ions and large space of expanded mesochannels after modification.

|

Fig. 12 Effect of contact time on U(VI) adsorption by AO@ ESBA-15 (C0 = 100 mg-U L−1, pH = 6, V = 100 mL, T = 25℃). |

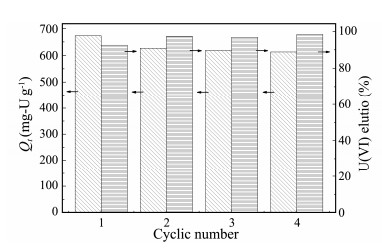

In order to check the reproducibility of AO@ESBA-15 material, experiments for several loading and elution (HNO3) were performed to study relationship between adsorption capacity and the corresponding cyclic regeneration times. Fig. 13 presents four successive cycles of adsorption and desorption test. During the first cycle, the adsorption capacity decreases by 6.9% (from 674 to 627 mg-U g−1). Obviously it is due to the incomplete U(VI) desorption of which the elution rate just reaches 92.5%. This phenomenon might be caused by decreasing size of mesopores functionalized with amidoxime groups, which increase the difficulty in the elution of loaded U(VI) inside the adsorbent mesopores. Whereas, due to the elution rate maintain high and constant after 4 times' repeated use, the adsorption capacity in the subsequent cyclic test just exhibits a slight decrease. This facile test evidences the feasibility of recycling the amidoxime-functionalized ESBA-15 for U(VI) adsorption.

|

Fig. 13 Reusability performance and U(VI) elution of AO@ESBA-15 (Experimental condition for the reusability: C0 = 100 mg-U L−1, pH = 6, V = 100 mL, T = 25℃; elution condition: CHNO3 = 2 mol L−1, t = 2 h). |

On comparing the efficiency of U(VI) ions adsorption using AO@ESBA-15 with other functionalized silica-adsorbents including our previous work, it is noteworthy that AO@ESBA-15 displays preferable adsorption performance at the comparable initial U(VI) concentration and temperature (Table 5). The adsorption capacity of AO@ESBA-15 reaches 674 mg-U g−1, which shows superior efficiency and promising application in uranium recovery.

|

|

Table 5 Adsorption performances of various materials for uranium |

The pore expanded SBA-15 material was synthesized by addition of TMB to conventional synthesis solution. The larger pore size and pore volume of resultant can form more available active sites for adsorption, favoring diffusion rate and the elution of attached U(VI) from adsorbent. A series of tests identify that the adsorption properties of ESBA-15 greatly enhance on the factors, the expanded pore channel structure and the increased density of modified groups. In addition, AO@ESBA-15 exhibits considerable adsorption capacity from uranium-containing aqueous medium and splendid recycling performance. The results show that ESBA-15 and amidoximation product deserve to a potential and alternative U(VI) separation and recovery materials from uranium enriched solution such as enriched seawater after desalination and nuclear polluted sewage.

AcknowledgementsThis work is financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 201964 020), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U1607124).

Bayramoglu, G. and Arica, M. Y., 2016. MCM-41 silica particles grafted with polyacrylonitrile: Modification in to amidoxime and carboxyl groups for enhanced uranium removal from aqueous medium. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 226: 117-124. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.12.040 (  0) 0) |

Benamor, T., Michelin, L., Lebeau, B. and Marichal, C., 2012. Flash induction calcination: A powerful tool for total template removal and fine tuning of the hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance in SBA-15 type silica mesoporous materials. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 147: 334-342. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.07.004 (  0) 0) |

Bryant, D. E., Stewart, D. I., Kee, T. P. and Barton, C. S., 2003. Development of a functionalized polymer-coated silica for the removal of uranium from groundwater. Environmental Science & Technology, 37: 4011-4016. (  0) 0) |

Chen, S. Y., Chen, Y. T., Lee, J. J. and Cheng, S., 2011. Tuning pore diameter of platelet SBA-15 materials with short mesochannels for enzyme adsorption. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 21: 5693-5703. DOI:10.1039/c0jm03591b (  0) 0) |

Cheng, Y. H., Zhou, L. B., Xu, J. X., Miao, C. X., Hua, W. M., Yue, Y. H. and Gao, Z., 2016. Chromium-based catalysts for ethane dehydrogenation: Effect of SBA-15 support. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 234: 370-376. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.07.031 (  0) 0) |

Dai, Y., Jin, J., Zhou, L., Li, T., Li, Z., Liu, Z., Huang, G., and Adesina, A. A., 2017. Preparation of hollow SiO2 microspheres functionalized with amidoxime groups for highly efficient adsorption of U(VI) from aqueous solution. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 311: 2029-2037.

(  0) 0) |

Fasfous, I. I. and Dawoud, J. N., 2012. Uranium(VI) sorption by multiwalled carbon nanotubes from aqueous solution. Applied Surface Science, 259: 433-440. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.07.062 (  0) 0) |

Feuston, B. P. and Higgins, J. B., 1994. Model structures for MCM-41 materials: A molecular dynamics simulation. Journal of Physical Chemistry, 98: 4459-4462. DOI:10.1021/j100067a037 (  0) 0) |

Goldberg, S., 2005. Inconsistency in the triple layer model description of ionic strength dependent boron adsorption. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 285(2): 509-517. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2004.12.002 (  0) 0) |

Guo, W., Chen, R., Liu, Y., Meng, M., Meng, X., Hu, Z. and Song, Z., 2013. Preparation of ion-imprinted mesoporous silica SBA-15 functionalized with triglycine for selective adsorption of Co(II). Colloid Surface A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 436: 693-703. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.08.011 (  0) 0) |

Jang, J. H., Dempsey, B. A. and Burgos, W. D., 2007. A modelbased evaluation of sorptive reactivities of hydrous ferric oxide and hematite for U(VI). Environmental Science & Technology, 41: 4305-4310. (  0) 0) |

Ji, G. J., Zhu, G. R., Wang, X. H., Wei, Y. L., Yuan, J. S. and Gao, C. J., 2017. Preparation of amidoxime functionalized SBA-15 with platelet shape and adsorption property of U(VI). Separation and Purification Technology, 174: 455-465. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2016.10.048 (  0) 0) |

Kamari, A., Ngah, W. S. W., Chong, M. Y. and Cheah, M. L., 2009. Sorption of acid dyes onto GLA and H2SO4 crosslinked chitosan beads. Desalination, 249: 1180-1189. DOI:10.1016/j.desal.2009.04.010 (  0) 0) |

Kango, S., Kalia, S., Celli, A., Njuguna, J., Habibi, Y. and Kumar, R., 2013. Surface modification of inorganic nanoparticles for development of organic-inorganic nanocomposites-A review. Progress in Polymer Science, 38: 1232-1261. DOI:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.02.003 (  0) 0) |

Kowal-Fouchard, A., Drot, R., Simoni, E. and Ehrhardt, J. J., 2004. Use of spectroscopic techniques for Uranium(VI)/ Montmorillonite interaction modeling. Environmental Science & Technology, 38: 1399-1407. (  0) 0) |

Li, X., Ding, C., Liao, J., Lan, T., Li, F., Zhang, D., Yang, J., Yang, Y., Luo, S., Tang, J. and Liu, N., 2014. Biosorption of uranium on Bacillus sp.dwc-2: Preliminary investigation on mechanism. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity, 135: 6-12. (  0) 0) |

Lützenkirchen, J., 1997. Ionic strength effects on cation sorption to oxides: Macroscopic observations and their significance in microscopic interpretation. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 195(1): 149-155. DOI:10.1006/jcis.1997.5160 (  0) 0) |

Mellah, A., Chegrouche, S. and Barkat, M., 2006. The removal of uranium(VI) from aqueous solutions onto activated carbon: Kinetic and thermodynamic investigations. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 296: 434-441. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2005.09.045 (  0) 0) |

Ojeda-López, R., Pérez-Hermosillo, I. J., Esparza-Schulz, J. M., Cervantes-Uribe, A. and Domínguez-Ortiz, A., 2015. SBA- 15 materials: Calcination temperature influence on textural properties and total silanol ratio. Adsorption, 21: 659-669. DOI:10.1007/s10450-015-9716-2 (  0) 0) |

Pang, H. W., Wu, Y. H., Wang, X. X., Hu, B. W. and Wang, X. K., 2019. Recent advances in composites of graphene and layered double hydroxides for water remediation: A review. Chemistry-An Asian Journal, 14: 2542-2552. DOI:10.1002/asia.201900493 (  0) 0) |

Rahmati, A., Ghaemi, A. and Samadfam, M., 2012. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies of uranium (VI) adsorption using Amberlite IRA-910 resin. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 39: 42-48. DOI:10.1016/j.anucene.2011.09.006 (  0) 0) |

Ren, Y. M., Yang, R. Z., Shao, L., Tang, H., Wang, S. F., Zhao, J. L., Zhong, J. R. and Kong, C. P., 2016. The removal of aqueous uranium by SBA-15 modified with phosphoramide: A combined experimental and DFT study. RSC Advances, 6: 68695-68704. DOI:10.1039/C6RA12269H (  0) 0) |

Schindler, M., Hawthorne, F. C., Freund, M. S. and Burns, P. C., 2009. XPS spectra of uranyl minerals and synthetic uranyl compounds.I: The U 4f spectrum. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 73: 2471-2487. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2008.10.042 (  0) 0) |

Sholl, D. S. and Lively, R. P., 2016. Seven chemical separations to change the world. Nature, 532: 435-437. DOI:10.1038/532435a (  0) 0) |

Sujandi, P. S. E., Han, D. S., Han, S. C., Jin, M. J. and Ohsuna, T., 2006. Amino-functionalized SBA-15 type mesoporous silica having nanostructured hexagonal platelet morphology. Chemical Communications, 27: 4131-4133. (  0) 0) |

Wang, L. F. and Yang, R. T., 2011. Increasing selective CO2 adsorption on amine-grafted SBA-15 by increasing silanol density. Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 115: 21264-21272. DOI:10.1021/jp206976d (  0) 0) |

Wang, X. H., Zhu, G. R. and Guo, F., 2013. Removal of uranium(VI) ion from aqueous solution by SBA-15. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 56: 151-157. DOI:10.1016/j.anucene.2013.01.041 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X. J., Ji, G. J., Zhu, G. R., Song, C. H., Zhang, H. and Gao, C. J., 2019. Surface hydroxylation of SBA-15 via alkaline for efficient amidoxime-functionalization and enhanced uranium adsorption. Separation and Purification Technology, 209: 623-635. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2018.07.039 (  0) 0) |

Wang, X. X., Chen, L., Wang, L., Fan, Q. H., Pan, D. Q., Li, J. X., Chi, F. T., Xie, Y., Yu, S. J., Xiao, C. L., Luo, F., Wang, J., Wang, X. L., Chen, C. L., Wu, W. S., Shi, W. Q., Wang, S. A. and Wang, X. K., 2019. Synthesis of novel nanomaterials and their application in efficient removal of radionuclides. Science China Chemistry, 62: 933-967. DOI:10.1007/s11426-019-9492-4 (  0) 0) |

Wang, Y., Gu, Z., Yang, J., Liao, J., Yang, Y., Liu, N. and Tang, J., 2014. Amidoxime-grafted multiwalled carbon nanotubes by plasma techniques for efficient removal of uranium(VI). Applied Surface Science, 320: 10-20. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.08.182 (  0) 0) |

Wang, Y. L., Song, L. J., Zhu, L., Guo, B. L., Chen, S. W. and Wu, W. S., 2014. Removal of uranium(VI) from aqueous solution using iminodiacetic acid derivative functionalized SBA-15 as adsorbents. Dalton Transactions, 43: 3739-3749. DOI:10.1039/c3dt52610k (  0) 0) |

Wang, Y., Noguchi, M., Takahashi, Y. and Ohtsuka, Y., 2001. Synthesis of SBA-15 with different pore sizesand the utilization as supports of high loading of cobalt catalysts. Catalysis Today, 68: 3-9. DOI:10.1016/S0920-5861(01)00317-0 (  0) 0) |

Webb, S. M., Fuller, C. C., Tebo, B. M. and Bargar, J. R., 2006. Determination of Uranyl incorporation into biogenic Manganese oxides using X-ray absorption spectroscopy and scattering. Environmental Science & Technology, 40: 771-777. (  0) 0) |

Xing, S. Y., Lv, P. M., Fu, J. Y., Wang, J. Y., Fan, P., Yang, L. M. and Yuan, Z. H., 2017. Direct synthesis and characterization of pore-broadened Al-SBA-15. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 239: 316-327. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.10.018 (  0) 0) |

Yang, L., Lei, W., Bo, L., Zhang, M., Rui, W., Guo, X., Xing, L., Ji, Z., Li, S. and Ma, L., 2016. Pore-free matrix with cooperative chelating of hyperbranched ligands for high-performance separation of uranium. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 8: 28853-28861. (  0) 0) |

Yang, L. M., Wang, Y. J., Luo, G. S. and Dai, Y. Y., 2005. Functionalization of SBA-15 mesoporous silica with thiol or sulfonic acid groups under the crystallization conditions. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 84: 275-282. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2005.05.037 (  0) 0) |

Yang, P., Chen, R., Liu, Q., Zhang, H., Liu, J., Yu, J., Liu, P., Bai, X. and Wang, J., 2019. The efficient immobilization of uranium(VI) by modified dendritic fibrous nanosilica (DFNS) using mussel bioglue. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 6: 746-755. DOI:10.1039/C8QI01351A (  0) 0) |

Yang, P. P., Liu, Q., Liu, J. Y., Chen, R. R., Li, R. M., Bai, X. F. and Wang, J., 2019. Highly efficient immobilization of uranium(VI) from aqueous solution by phosphonate-functionalized dendritic fibrous nanosilica (DFNS). Journal of Hazardous Materials, 363: 248-257. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.09.062 (  0) 0) |

Yang, S. T., Zong, P. F., Ren, X. M., Wang, Q. and Wang, X. K., 2012. Rapid and highly efficient preconcentration of Eu(III) by core-shell structured Fe3O4@humic acid magnetic nanoparticles. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 4(12): 6891-6900. (  0) 0) |

Yang, S. Y., Li, Q., Chen, L., Chen, Z. S., Hu, B. W., Wang, H. H. and Wang, X. K., 2020. Synergistic removal and reduction of U(VI) and Cr(VI) by Fe3S4 micro-crystal. Chemical Engineering Journal, 385: 123909. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123909 (  0) 0) |

Yin, L., Hu, B. W., Zhuang, L., Fu, D., Li, J., Hayat, T., Alsaedi, A. and Wang, X. K., 2020. Synthesis of flexible cross-linked cryptomelane-type manganese oxide nanowire membranes and their application for U(VI) and Eu(III) elimination from solutions. Chemical Engineering Journal, 381: 122744. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122744 (  0) 0) |

Yuan, L. Y., Liu, Y. L., Shi, W. Q., Li, Z. J., Lan, J. H., Feng, Y. X., Zhao, Y. L., Yuan, Y. L. and Chai, Z. F., 2012. A novel mesoporous material for uranium extraction, dihydroimidazole functionalized SBA-15. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 22: 17019-17026. DOI:10.1039/c2jm31766d (  0) 0) |

Zhang, A., Asakura, T. and Uchiyama, G., 2003. The adsorption mechanism of uranium(VI) from seawater on a macroporous fibrous polymeric adsorbent containing amidoxime chelating functional group. Reactive & Functional Polymers, 57: 67-76. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Y. G., Li, J. X., Zhang, S. W. and Wang, X. K., 2014. Amidoxime-functionalized magnetic mesoporous silica for selective sorption of U(VI). RSC Advances, 4: 32710-32717. DOI:10.1039/C4RA05128A (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Y. G., Li, J. X., Zhao, L. P., Zhang, S. W., Huang, Y. S., Wu, X. L. and Wang, X. K., 2014. Synthesis of amidoxime-functionalized Fe3O4@SiO2 core-shell magnetic microspheres for highly efficient sorption of U(VI). Chemical Engineering Journal, 235: 275-283. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2013.09.034 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Y. G., Wang, X. X., Li, J. X. and Wang, X. K., 2015. Amidoxime functionalization of mesoporous silica and its high removal of U(VI). Polymer Chemistry, 6: 5376-5384. DOI:10.1039/C5PY00540J (  0) 0) |

Zhe, W., Chao, X., Lu, Y., Wu, F., Gang, Y., Wei, G., Sun, T. and Jing, C., 2017. Visualization of adsorption: Luminescent mesoporous silica-carbon dots composite for rapid and selective removal of U(VI) and in-situ monitoring the adsorption behavior. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 9: 7392-7398. (  0) 0) |

Zheng, H., Zhou, L. M., Liu, Z. R., Le, Z. G., Ouyang, J. B., Huang, G. L. and Shehzad, H., 2019. Functionalization of mesoporous Fe3O4@SiO2 nanospheres for highly efficient U(VI) adsorption. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 279: 316-322. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.12.038 (  0) 0) |

Zienkiewicz-Strzałka, M., Deryło-Marczewska, A. and Kozakevych, R. B., 2018. Silica nanocomposites based on silver nanoparticles-functionalization and pH effect. Applied Nanoscience, 8: 1649-1668. (  0) 0) |

Zou, H., Zhou, L., Huang, Z., Liu, Z. and Luo, T., 2017. Characteristics of equilibrium and kinetic for U(VI) adsorption using novel diamine-functionalized hollow silica microspheres. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 311: 269-278. DOI:10.1007/s10967-016-4937-8 (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19