2) State Key Laboratory of Marine Food Processing and Safety Control, College of Food Science and Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266404, China;

3) Qingdao Key Laboratory of Food Biotechnology, Qingdao 266404, China;

4) Key Laboratory of Biological Processing of Aquatic Products, China National Light Industry, Qingdao 266404, China;

5) Laboratory for Marine Drugs and Bioproducts of Laoshan Laboratory, Qingdao 266237, China

Chitin is a naturally occurring linear polysaccharide composed of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) linked by β-1, 4-glycosidic bonds (Islam et al., 2017). It is the second most abundant biological macromolecule in nature after cellulose (Pham et al., 2024), with an estimated annual production of 1012 – 1014 tons (Yadav et al., 2019). Chitin exists in crustaceans, insect shells, fungal cell walls, mollusk cartilage, and some algae (Tsurkan et al., 2021). Currently, shrimp and crab shells are the primary raw materials for the industrial production of chitin (Younes and Rinaudo, 2015). Chitin, as a macromolecular polymer, is greatly limited in its widespread applications due to its high crystallinity and insolubility (Rinaudo, 2006). However, N-acetyl chitooligosaccharides (NCOSs) and GlcNAc, the degradation products of chitin, have better water solubility and biological functions than chitin, such as hypoglycemic, antioxidant, anti-tumor, anti-fungal and so on (Fratter et al., 2014; Ganan et al., 2021; Tabassum et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023). NCOSs and GlcNAc with specific degrees of polymerization (DP) have received extensive attention and have been used in agriculture, environmental protection, food, cosmetics, and medicine (Bhattacharya et al., 2007; Yin et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). The favorable characteristics of NCOSs and GlcNAc indicate promising market potential, highlighting the importance of chitin degradation in producing high-value and premium-quality products.

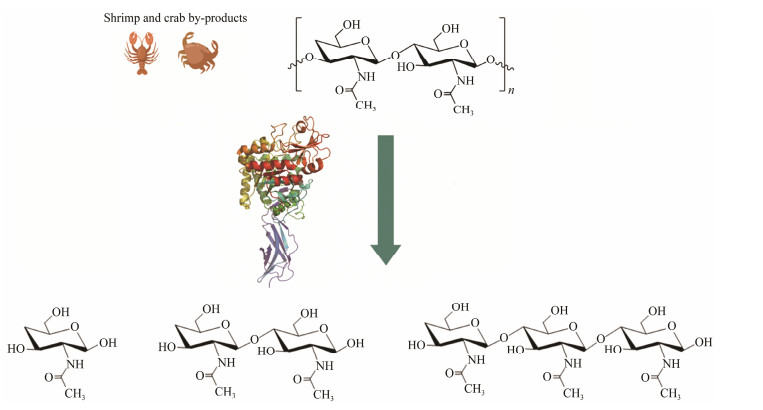

The traditional approach to degrading crystalline chitin involves the use of strong acids and alkalis, which lead to environmental pollution and make it challenging to control the reaction process and resulting products due to their violent reaction (Kumar et al., 2021). In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on biological methodologies (Fig.1) (Pan et al., 2023). Chitinase (EC 3.2.2.14) is central to the bioconversion of crystalline chitin. Despite the significant advantages of catalyzed hydrolysis by chitinase over traditional chemical acid-base degradation in terms of reaction conditions, environmental protection, and product specificity, chitinase is still hindered by the dense structure of crystalline chitin, which acts as a barrier to degradation (Pan et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2023). Therefore, when employing chitinase for chitin degradation, to enhance the accessibility and conversion efficiency of enzymes, pretreatment with acids and bases (to prepare colloidal chitin) (Wang et al., 2023), ionic liquids (e.g., 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, etc.) (Li et al., 2019), and physical methods (e.g., ball milling, ultrasound, etc.) (Hou et al., 2020; Duhsaki et al., 2023) are generally used to reduce the crystallinity of crystalline chitin. The direct biodegradation of recalcitrant crystalline chitin without pretreatment has continuously attracted extensive attention and interest from researchers. Because the direct degradation of crystalline chitin by biological methods will avoid additional environmental pollution and energy consumption, it will serve as a sustainable and eco-friendly strategy to innovate chitin industrialization technology (Gao et al., 2018; Mukherjee et al., 2020; Mathew et al., 2021; Qiu et al., 2022). Excitingly, enzymes and microorganisms that can directly convert crystalline chitin have been successively reported (Sun et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023b), which significantly advances the application prospects for chitin biodegradation.

|

Fig. 1 Approximate process of biodegradation of chitin. |

In recent years, our group has been active in the field of chitin degradation, such as the discovery and screening of new chitinases (Gao et al., 2018; Xing et al., 2023), pretreating chitin with ionic liquid (Li et al., 2019), engineering the chitinase domain (Su et al., 2021), physical milling for preparing chitin nanofibers to aid enzymatic conversion of chitin for NCOS preparation (Xing et al., 2024), and using lytic polysaccharides monooxygenases (LPMOs) to drive chitin degradation (Zhao et al., 2024). At present, in the field of chitinase and comprehensive utilization of chitin resources, there have been relevant reviews on the research progress on the enzymatic preparation of NCOSs and GlcNAc (Gao et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023b), the biological activities and applications of NCOSs and GlcNAc (Liu et al., 2023b), catalytic mode and mechanism of chitinase (Huang et al., 2023), and research progress on the chitin degradation (Mahajan et al., 2024). However, there is still a gap in the review on the biotransformation of crystalline chitin, while a comprehensive critical review of the direct biodegradation of crystalline chitin to NCOS and GlcNAc is still required. The review could provide valuable insights into the unique characteristics of this process and potentially pave the way for developing more efficient technical solutions for chitin biodegradation. In this paper, we will review the current status of the whole process of biological methods for degradation of crystalline chitin.

2 Chitinase Degrade Crystalline ChitinThe majority of reported chitinases demonstrate robust activity against colloidal chitin treated with concentrated hydrochloric acid, yet they show significantly reduced activity against crystalline chitin. Table 1 summarizes current chitinases capable of directly degrading crystalline chitin, and engineered chitinases are also included. For example, chitinases Chia 4287, Chib 0431, and Chib 0434 from Pseudoalteromonas flavipulchra DSM 14401T can degrade crystalline chitin to produce (GlcNAc)2 (N, N'-diacetylchitobiose), yet their activities were only 0.17 U mg−1, 0.04 U mg−1 and 0.01 U mg−1, respectively (Ren et al., 2022). Even if the activity of some chitinases towards crystalline chitin is considerable, it is nearly 10 times lower than that on colloidal chitin. The activity of ChiTg from Trichoderma gamsii R1 against colloidal chitin was 36.9 U mg−1, whereas it was 5.7 U mg−1 against crystalline chitin (Wang et al., 2023). Furthermore, the activity of ChiE1 from Coprinopsis cinerea on crystalline chitin was only 9.65% of that on colloidal chitin (Zhou et al., 2018). With the characterization of more and more chitinases, it has been found that some chitinases with special structural components can efficiently degrade crystalline chitin. Typically, chitinase consists of catalytic domain (CD) and chitin-binding domain (CBD) (Liu et al., 2023a). CBD specifically recognizes and binds chitin, and then brings the CD to its substrate for hydrolysis (Itoh et al., 2006). Studies have shown that CBD can improve the catalytic efficiency of chitinase by destroying the internal structure of crystalline chitin or by directly binding more substrates (Xu et al., 2017; Su et al., 2021). For example, BaChiA from Bacillus aryabhattai has two N-terminal CBDs, and its enzymatic activity against crystalline chitin is 625 U mg−1 (Subramani et al., 2022, 2024). Similarly, CsChiE, cloned from Chitiniphilus shinanonensis, also has two N-terminal CBDs, enabling CsChiE to efficiently degrade chitin flakes within 9 h, yielding a mixture containing 0.35 mmol L−1 of GlcNAc and (GlcNAc)2 (Rani et al., 2020). The catalysis efficiency of chitinase not only enhanced by multiple CBDs, but also influenced by the function of the CD, which is influenced by the crystallinity of chitin. Lower crystallinity means that chitin can be more effectively degraded by chitinase directly. The trimodular chitinase Jd1381 cloned from Jonesia peculficans contains one CBD, along with an LPMO domain and a chitinase CD. LPMO has been shown to reduce the crystallinity of crystalline chitin, so Jd1381 can also efficiently degrade crystalline chitin (Mekasha et al., 2020).

|

|

Table 1 Summary of chitinase capable of directly degrading crystalline chitin |

From the above examples, chitinases with special structural compositions, such as multiple CBDs, tend to have higher catalytic efficiency. Therefore, investigations into the structural composition of chitinases, including CBD and CD, can facilitate the discovery of more efficient methods for degrading crystalline chitin. The majority of the studied chitinases typically utilize colloidal chitin as the substrate, yet their capability of directly degrading crystalline chitin has not been extensively studied.

3 Engineering Chitinase to Degrade Crystalline ChitinWhile certain chitinases can degrade crystalline chitin, their efficiency is constrained by the structure of chitin, leading to low degradation efficiency. This limitation presents a significant challenge to both the environmentally sustainable production of GlcNAc and NCOSs, as well as the efficient utilization of chitin. Therefore, it is essential to employ strategies that enable the efficient utilization of locally sourced chitin. Structurally, chitinase usually consists of CD and CBD between N and C terminals, and CBD typically binds with the substrate, while CD catalyzes its degradation (Zhang et al., 2023). Fig.2A illustrates typical arrangements of the CDs and CBDs commonly found in bacterial chitinases. Many chitinases often feature a fibronectin type III (FnIII) domain located between the CD and CBD domains. The FnIII domain acts as a spacer, regulating the positioning of the CD on the chitin surface (Malecki et al., 2020). Optimization of the CBD of chitinase can significantly enhance its chitin degradation efficiency (Takashima et al., 2018). In addition, CD serves as the primary site where chitinase directly degrades the substrate (Juárez-Hernández et al., 2019). Therefore, the engineering of both CBD and CD is crucial for enhancing chitinase activity and addressing the challenges of degrading and utilizing crystalline chitin. Currently, many researchers have made significant advances in this field.

|

Fig. 2 Typical configurations of CDs and CBDs in chitinases, and engineered modifications of CBDs. (A), typical configurations of CDs and CBDs in chitinases; (B), common strategies for engineering CBDs. Single CD and CBD are used here as examples. |

Due to the importance of CBD for the effective degradation of crystalline chitin, researchers have focused on engineering CBDs to enhance the efficiency of chitinase in degrading crystalline chitin. Fig.2B depicts a common approach currently used in engineering CBD. Currently, the primary approach involves increasing the number of CBDs and substituting the original CBDs to enhance chitinase binding and disrupt the substrate. For example, by replacing the original CBD of SaChiA4 with ChiA1 CBD from Bacillus circulans WL-12, known for its specific binding capability to crystalline chitin, the variant exhibited enhanced binding affinity to insoluble substrates, resulting in a 54% increase in catalytic efficiency on crystalline chitin (Su et al., 2021). Study has incorporated a CBD into the chitinase Chit42 from Trichoderma aeruginosa, which originally did not possess a CBD. Consequently, the chimeric chitinase exhibits an activity of 2.4 U mL−1 for degrading crystalline chitin, while it is 1.4 U mL−1 for Chit42 (Matroodi et al., 2013). Hashimoto et al. (2000) compared the binding affinity of chitinase ChiA1 and the truncated form A1ΔCBD lacking the CBD to crystalline chitin and colloidal chitin. Interestingly, they found that both ChiA1 and A1ΔCBD exhibited the highest affinity for colloidal chitin. However, the reduced binding ability of A1ΔCBD to crystalline chitin was significantly more pronounced compared to its binding to colloidal chitin, which further underscores the significance of CBD for the activity of chitinase on crystalline chitin. CBD also can disrupt the structure of insoluble polysaccharides and promote the generation of additional insoluble reducing ends, while most CBDs attach and slide on the surface of crystalline chitin and probe for any surface defects, such as bends, turns, interstices between chains, and micro-cracks. They then wedge themselves into the defects, which increases the production of reducing ends of insoluble substrate, and provides more sites to effectively degrade the crystalline chitin (Bernardes et al., 2019). Indeed, CBDs that focus on chitin disruption typically result in greater improvements in efficiency compared to those that enhance enzyme-substrate binding. For example, Sun et al. (2023) removed the original CBD from ActChi and then fused the CBD from Pyrococcus furiosus, which can destroy the structure of crystalline chitin, to the N-terminus of CD.

The resulting chimeric enzyme, CBD-CDchi, exhibited a 400% increase in degradation efficiency compared to that of ActChi. This suggests that the CBD derived from Pyrococcus furiosus demonstrates superior capability in detroying the structure of crystalline chitin to improve the activity of chitinase on crystalline chitin compared to the original CBD. Similarly, Deng et al. (2020) fused 10 CBD candidates from bacterial glycosidases to either Cor N-terminus of chitinase Chit46. Among them, only three chimeric enzymes fused to the C-terminus were successfully expressed, with Chit46-CBD3 showing the highest enzyme activity for degrading crystalline chitin, reaching 219% of the activity of Chit46.

3.2 Engineering CDEnzymes typically catalyze specific reactions by interacting with substrate molecules through their CD (Tallant et al., 2010). In the hydrolysis process of crystalline chitin, the CD of chitinase cleaves the β-1, 4-glycosidic bonds within chitin molecules, resulting in the degradation of chitin into smaller units. Multiple studies have demonstrated that amino acid residues in the active center of chitinase play a pivotal role in sustaining its catalytic process (Horn et al., 2006). Therefore, researchers have sought to enhance the efficiency of chitinase on crystalline chitin by modifying key amino acid residues within its CD. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on three relatively conserved aromatic amino acids (Phe-48, Tyr-286, and Tyr-209) and eight polar amino acids (Lys-53, Arg-11, Asp-137, Glu-287, Arg-264, Asp-208, Lys-186, Asp-180, and Glu-346) at the catalytic site of chitinase SsChi18A from Streptomyces speciales F-3. Among the 17 mutants tested, the activities of the single mutants F48W, double mutants F48W/Y209F, F48W/Y286W against crystalline chitin increased by 35%, 16%, and 36%, respectively. However, the activities against colloidal chitin were significantly reduced. The results suggest that mutations in aromatic amino acids Phe-48,

Tyr-286, and Tyr-209 might have sped up the movement of chitinase along the crystalline chitin surface (Zhao et al., 2023b). However, mutations are inherently random, and sometimes unpredictable mutations can lead to undesirable outcomes. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on three aromatic amino acids (Trp-167, Trp-275, and Phe-396) in the catalytic center of chitinase from Seratella marcescens. This resulted in the creation of three single mutants and one double mutant, all of which showed reduced activity against crystalline chitin (Zakariassen et al., 2009). Therefore, engineering CD to enhance the enzymatic activity for hydrolyzing crystalline chitin requires extensive screening efforts to achieve desirable outcomes.

The engineering of chitinase aims to address the challenge of efficiently degrading crystalline chitin. Researchers can seek methods to improve the enzyme's efficiency in degrading crystalline chitin by concentrating on its core structures, CD and CBD. This approach holds promise for converting abundant chitin resources into valuable products such as NCOSs and GlcNAc.

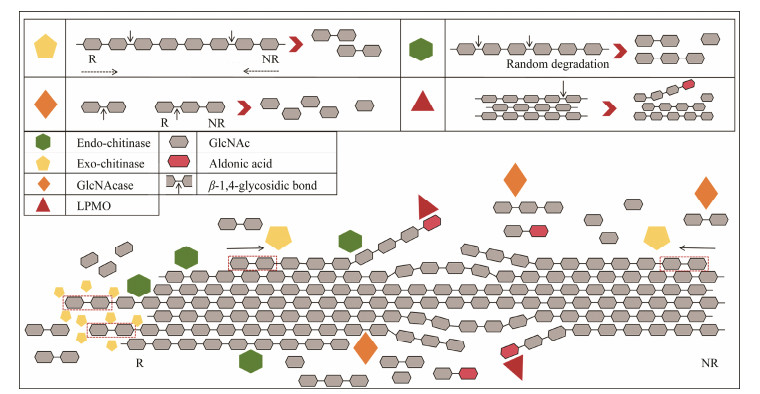

4 Synergistic Degradation of Crystalline Chitin by Multi-EnzymesChitin has multiple binding sites and can be targeted and catalyzed by a variety of enzymes (Zhang et al., 2023). Therefore, numerous studies have utilized different enzymes in combination with chitinase to degrade crystalline chitin. Multi-enzyme synergy typically involves different combinations of enzymes with distinct mechanisms, including endo- and exo-chitinase (Zhou et al., 2018), chitinase and N-acetylglucosaminidase (GlcNAcase) (Han et al., 2024), as well as chitinase and LPMO (Zhao et al., 2024). Different combinations exhibit distinct mechanisms of action and degradation efficiencies. Fig.3 illustrates the functional diversity of various chitinases and elucidates their synergistic mechanisms.

|

Fig. 3 Schematic representation of various chitinase functions and their synergistic interactions. |

Endo-chitinase creates NCOSs and GlcNAc by degrading chitin with a random cleavage mode, while exo-chitinase produces (GlcNAc)2 by acting on the reducing end or nonreducing end of chitin (Poria et al., 2021). Studies have suggested that the synergistic effect of endo- and exochitinase is due to the open and flat substrate-binding cleft in endo-chitinase, which makes it easier for the enzyme to attach to the rough and disordered fibrils on the surface of crystalline chitin. This also facilitates the movement of exochitinase on the chitin surface, as well as the generation of more reduced ends by endo-chitinase. These reduced ends act as starting points for exo-chitinase activity, leading to its accumulation at various points of chitin degradation and the formation of protein clusters spanning multiple chitin chains. This process creates additional starting points for exo-chitinase, significantly enhancing the efficiency of crystalline chitin degradation (Qu et al., 2020). Both endo- and exo-chitinases have been found in some microorganisms. For example, endo- and exo-chitinase from Penicilum k10 can degrade crystalline chitin into GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, and (GlcNAc)3 (Xie et al., 2021). Compared with the use of ChiE1 and ChiIII alone, the combined use of exo-chitinase ChiE1 and endo-chitinase ChiIII from Coprinopsis cinerea can increase the release of reducing sugars from chitin powder by approximately 120% (Zhou et al., 2018). When exochitinase VhChit2 and endo-chitinase VhChit6 in Vibrio harveyi synergistically degraded crystalline chitin, the amount of reduced sugar in the product increased by 75% (Zhang et al., 2023). Studies have shown that multiple endo- and endo-chitinases can also work synergistically. Mukherjee et al. (2020) used six different endo- and exo-chitinases to degrade 5 mg mL−1 of α- and β-chitin, respectively. The α-chitin reaction system produced 0.1 mmol L−1 of GlcNAc and 0.55 mmol L−1 of (GlcNAc)2 within 96 h, the β-chitin re- action system produced 2.3 mmol L−1 GlcNAc and 7 mmol L−1 (GlcNAc)2 in 72 h.

4.2 Chitinase and GlcNAcaseGlcNAcases have been shown to cleave highly crystalline chitin and NCOSs, thereby enhancing the susceptibility of chitin to chitinase (Han et al., 2024). The chitinase ScChiC and GlcNAcase from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) synergistically convert crystalline chitin into GlcNAc effectively, achieving a conversion rate of over 90% within 8 h (Nhung and Doucet, 2016). Han et al. (2024) constructed a two-enzyme catalytic system comprising GlcNAcase and the chitinase mPbChi70 that was cloned from Paenibacillus barengoltzii, and the system could directly convert powdered chitin into GlcNAc with a conversion efficiency of up to 71.9%. When only using mPbChi70 to hydrolyze powdered chitin, the conversion efficiency was 18.34%. They also employed Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to observe and calculate the crystallinity of chitin powder treated with GlcNAcase and mPbChi70, which was 14.8% lower than that of powder treated with mPbChi70 alone. Additionally, chitinase SaChiB that was cloned from Streptomyces alfalfae ACCC 40021, when combined with Glc-NAcases SaHEX, exhibited a remarkably high conversion rate of 95.2% from chitin powder to GlcNAc within 8 h (Lv et al., 2021). However, the precise mechanism through which GlcNAcase and chitinase synergistically degradation of crystalline chitin remains unclear. Therefore, it is necessary to further investigate and reveal the catalytic mechanism of GlcNAcase and chitinase synergy.

4.3 Chitinase and LPMOLPMOs are copper ion-dependent oxidases. LPMOs can depolymerize chitin by oxidatively breaking the glycosidic bonds in chitin, thereby exposing more chitinase binding sites to achieve synergistic degradation of crystalline chitin (Pan et al., 2023). Because LPMOs can greatly increase the hydrolysis efficiency of polysaccharides by glycoside hydrolases, they have garnered widespread attention from researchers globally (Hemsworth et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2022). The synergistic effect of LPMO cloned from Trichoderma guizhouense and commercial chitinase mixture increased the degradation efficiency of α-chitin and β-chitin by 39.9% and 288.2%, respectively (Ma et al., 2021). Similarly, the synergistic effect of LPMO and chitinase cloned from Aeromonas salmonicida could increase the degradation efficiency of chitin powder by more than two times (Pentekhina et al., 2020). It has been discovered that the combined catalytic efficiency of three chitinases (ChiA, ChiB, and ChiC) together with Oceanobacillus sp. J11TS1 (OsLPMO10A) for crystalline chitin degradation was 2.03 times higher than that without LPMOs (Zhao et al., 2024). In addition, Li's group and Nakagawa's group demonstrated that the presence of LPMO can increase the activity of chitinase on crystalline chitin (Li et al., 2017; Nakagawa et al., 2020). Differently, Sato et al. (2023) discovered that Chitiniphilus shinanonensis SAY3T possesses three types of enzymes with different activities: endo-chitinase, GlcNAcase, and LPMOs.

Certainly, various enzymes cooperatively degrade crystalline chitin to alleviate competition for substrate binding sites. They degrade crystalline chitin to produce NCOS and GlcNAc through different synergistic ways using different mechanisms and modes of action (Zhou et al., 2018; Song et al., 2020). Studies have confirmed the effective synergistic degradation of crystalline chitin by multiple enzymes, attracting more researchers to investigate the effective methods for biodegradation of crystalline chitin from the viewpoint of multi-enzyme synergy.

5 Degradation of Crystalline Chitin by MicroorganismsFor a long time, the absence of chitin accumulation on Earth suggests the presence of microorganisms capable of degrading chitin in nature (Gutiérrez-Román et al., 2014). Microorganisms inherently possess a diverse array of enzymes, and strains capable of degrading chitin can be regarded as intricate multi-enzyme systems. For example, three chitinases that effectively degrade crystalline chitin, SmChi-A, SmChi-B, and SmChi-C, were identified in the extensively studied chitin-degrading bacterium Serratia marcescens (Gutiérrez-Román et al., 2014). A chitinasedegrading bacterium Streptomyces chilikensis RC 1830 isolated from Chilika Lake, India, identified 89 genes involved in chitin degradation (Behera et al., 2022). In addition to the microbe that is equivalent to a multi-enzyme system capable of more efficient chitin degradation, microorganisms also possess metabolic systems that further facilitate efficient chitin degradation. In addition to the direct degradation, microorganisms can also play a significant role in the depolymerization of crystalline chitin. For example, crystalline chitin treated by Chitinolyticbacter meiyuanensis SYBC-H1 can be completely degraded to GlcNAc by chitinase within 6 h (Zhang et al., 2018). Penicillium oxalicum K10, isolated from a medium containing chitin powder, exhibits the ability to degrade colloidal chitin to GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, and (GlcNAc)3. Although only experiments on colloidal chitin degradation were conducted, it can be inferred that Penicillium oxalicum K10 is capable of degrading crystalline chitin (Xie et al., 2021). Paenibacillus LS1 was obtained by screening in a medium containing crystalline chitin. During Paenibacillus LS1's 10-day growth cycle, observation of ectoprotein secretion revealed that Paenibacillus LS1 grown on crystalline chitin had nearly ten times lower extracellular protein concentration compared to Paenibacillus LS1 grown on colloidal chitin. This suggests that Paenibacillus LS1 has limited ability to degrade crystalline chitin. The mixed enzyme system secreted by Paenibacillus LS1 was applied to degrade crystalline chitin. Then the product was analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and it was identified that the products are GlcNAc and (GlcNAc)2, with less than 1% conversion of crystalline chitin within 72 h (Mukherjee et al., 2020). Despite the poor performance of some microorganisms, researchers have discovered microorganisms in certain environments exhibiting efficient degradation of crystalline chitin. Cellvibrionaceae KSP-S5-2, isolated from estuarine sediment in the mangrove, demonstrated remarkable chitin degradation ability. When incubated in a medium containing 1% crystalline chitin for 10 days, it achieved an outstanding degradation rate of 90.1% (Nyok-Sean and Furusawa, 2024).

The degradation efficiency of crystalline chitin varies among different microorganisms, obviously influenced by their environment. Therefore, exploring specialized environments is one of the most effective approaches for discovering microorganisms that can efficiently degrade crystalline chitin. Microorganisms with low efficiency in degrading crystalline chitin can enhance their degradation capabilities through a deeper understanding of the degradation process and the application of genetic engineering techniques, meeting the requirements of industrial manufacturing. With the advancements in science and technology and the thorough exploration by researchers, the utilization of crystalline chitin will reach unprecedented heights.

6 Conclusions and Future PerspectivesThe primary challenge in chitin degradation stems from its high degree of crystallinity, which arises from its intricate hydrogen bonding network. Recently, there has been increasing interest in discovering eco-friendly and efficient methods for degrading crystalline chitin. This paper aims to provide an overview of current advances in this field. Complete biological methods are the most promising approach for the degradation of crystalline chitin. In contrast to physical and chemical methods, which are plagued by issues such as environmental pollution, high costs, and complex operations, biological degradation distinguishes itself with its environmentally friendly, efficient, and manageable reactions. This article summarizes several chitinases that feature multiple CBDs or other domains capable of efficiently degrading crystalline chitin. Researchers drew inspiration from these chitinases with multiple CBDs and designed the CBDs of chitinase to improve catalytic efficiency. Further-more, we discuss the efficiency of multi-enzyme synergy in the degradation of crystalline chitin, highlighting its significance in the biodegradation process of insoluble substrates. Microorganisms contain many enzymes, and chitindegrading strains can be considered as specialized forms of multi-enzyme systems that degrade crystalline chitin. However, the progress in finding green and efficient methods for degrading crystalline chitin still needs to be further explored. There is an urgent need for new approaches to boost efficiency, fully leverage chitin's beneficial biological properties, and unlock the high-value potential of abundant chitin resources. To the best of our knowledge, the topics listed below are key challenging issues that need to be addressed in future researches.

First, the current efficiency of biological methods in degrading crystalline chitin is generally low. To address the challenge, it is crucial to explore and discover new chitinase. Furthermore, there is considerable potential in employing genetic engineering and protein engineering to design chitinase in a more rational manner. This approach could substantially enhance the activity and catalytic efficiency of chitinase, and facilitate more effective degradation of crystalline chitin.

Second, the current understanding of the mechanism behind multi-enzyme synergy is limited, particularly about its capacity to enhance the degradation of crystalline chitin. This lack of understanding complicates the determination of the most effective enzyme combinations for synergistic degradation. To tackle this issue, deeper investigation into the mechanisms of multi-enzyme synergy is necessary. With a more thorough understanding, researchers can develop more precise strategies for synergistic degradation, ultimately enhancing the degradation efficiency towards crystalline chitin while also regulating the DP of the resulting products.

Third, the industrial application of biodegradable chitin requires further cost reduction. There is a need to explore methods for stabilizing enzymes and enhancing catalytic efficiency through immobilization and cascade reactions, as well as advancing enzyme recycling catalysis to meet industrial production demands. Furthermore, the development of safe, efficient, and high-purity industrial production methods of NCOSs and GlcNAc involving microorganisms is essential.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFD2401 504), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U21A20271, 32225039), the Key R & D Program of Shandong Province (No. 2022TZXD001), the Earmarked Fund for CARS (No. CARS-48), and the Qingdao Shinan District Science and Technology Plan Project (No. 2022-3-010-SW).

Behera, H. T., Mojumdar, A., Kumari, K., Gouda, S. K., Das, S., and Ray, L., 2022. Exploration of genomic and functional features of chitinolytic bacterium Streptomyces chilikensis RC1830, isolated from Chilika Lake, India. 3 Biotech, 12: 120. DOI:10.1007/s13205-022-03184-5 (  0) 0) |

Bernardes, A., Pellegrini, V. O. A., Curtolo, F., Camilo, C. M., Mello, B. L., Johns, M. A., et al., 2019. Carbohydrate binding modules enhance cellulose enzymatic hydrolysis by increasing access of cellulases to the substrate. Carbohydrate Polymers, 211: 57-68. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.01.108 (  0) 0) |

Bhattacharya, D., Nagpure, A., and Gupta, R. K., 2007. Bacterial chitinases: Properties and potential. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 27(1): 21-28. DOI:10.1080/07388550601168223 (  0) 0) |

Deng, J. J., Zhang, M. S., Li, Z. W., Lu, D. L., Mao, H. H., Zhu, M. J., et al., 2020. One-step processing of shrimp shell waste with a chitinase fused to a carbohydrate-binding module. Green Chemistry, 22(20): 6862-6873. DOI:10.1039/d0gc02611e (  0) 0) |

Duhsaki, L., Mukherjee, S., and Madhuprakash, J., 2023. Improving the efficiency and sustainability of chitin bioconversion through a combination of Streptomyces chitin-active-secretomes and mechanical-milling. Green Chemistry, 25(17): 6832-6844. DOI:10.1039/d3gc01084h (  0) 0) |

Fratter, A., Frare, C., Uras, G., Bonini, M., Bariani, E. C., Ragazzo, B., et al., 2014. New chitosan salt in gastro-resistant oral formulation could interfere with enteric bile salts emulsification of diet fats: Preliminary laboratory observations and physiologic rationale. Journal of Medicinal Food, 17(6): 723-729. DOI:10.1089/jmf.2013.0131 (  0) 0) |

Ganan, M., Lorentzen, S. B., Gaustad, P., and Sorlie, M., 2021. Synergistic antifungal activity of chito-oligosaccharides and commercial antifungals on biofilms of clinical Candida isolates. Journal of Fungi, 7: 718. DOI:10.3390/jof7090718 (  0) 0) |

Gao, K., Qin, Y. K., Liu, S., Wang, L. S., Xing, R. E., Yu, H. H. et al., 2023. A review of the preparation, derivatization and functions of glucosamine and N-acetyl-glucosamine from chitin. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications, 5: 100 296. DOI:10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100296 (  0) 0) |

Gao, L., Sun, J. A., Secundo, F., Gao, X., Xue, C. H., and Mao, X. Z., 2018. Cloning, characterization and substrate degradation mode of a novel chitinase from Streptomyces albolongus ATCC 27414. Food Chemistry, 261: 329-336. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.04.068 (  0) 0) |

Guo, X., An, Y. J., Liu, F. F., Lu, F. P., and Wang, B., 2022. Lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase – A new driving force for lignocellulosic biomass degradation. Bioresource Technology, 362: 127803. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127803 (  0) 0) |

Gutiérrez-Román, M. I., Dunn, M. F., Tinoco-Valencia, R., Holguín-Meléndez, F., Huerta-Palacios, G., and Guillén-Navarro, K., 2014. Potentiation of the synergistic activities of chitinases ChiA, ChiB and ChiC from Serratia marcescens CFFSURB2 by chitobiase (Chb) and chitin binding protein (CBP). World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, 30(1): 33-42. DOI:10.1007/s11274-013-1421-2 (  0) 0) |

Han, S. S., Xue, Y. B., Yan, Q. J., Jiang, Z. Q., and Yang, S. Q., 2024. Development of a two-enzyme system in Aspergillus niger for efficient production of N-acetyl-β-D-glucosamine from powdery chitin. Bioresource Technology, 393: 130024. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2023.130024 (  0) 0) |

Hashimoto, M., Ikegami, T., Seino, S., Ohuchi, N., Fukada, H., Sugiyama, J., et al., 2000. Expression and characterization of the chitin-binding domain of chitinase A1 from Bacillus circulans WL-12. Journal of Bacteriology, 182(11): 3045-3054. DOI:10.1128/JB.182.11.3045-3054.2000 (  0) 0) |

Hemsworth, G. R., Johnston, E. M., Davies, G. J., and Walton, P. H., 2015. Lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases in biomass conversion. Trends in Biotechnology, 33(12): 747-761. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.09.006 (  0) 0) |

Horn, S. J., Sikorski, P., Cederkvist, J. B., Vaaje-Kolstad, G., Sorlie, M., Synstad, B., et al., 2006. Costs and benefits of processivity in enzymatic degradation of recalcitrant polysaccharides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(48): 18089-18094. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0608909103 (  0) 0) |

Hou, F. R., Ma, X. B., Fan, L. H., Wang, D. L., Ding, T., Ye, X. Q., et al., 2020. Enhancement of chitin suspension hydrolysis by a combination of ultrasound and chitinase. Carbohydrate Polymers, 231: 115669. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115669 (  0) 0) |

Huang, H., Zhou, G. P., Luo, S. J., and Xie, S. Q., 2023. Catalytic upgrading of chitin: Advances, mechanistic insights, and prospect. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 128: 127-142. DOI:10.1016/j.jiec.2023.08.014 (  0) 0) |

Islam, S., Bhuiyan, M. A. R., and Islam, M. N., 2017. Chitin and chitosan: Structure, properties and applications in biomedical engineering. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 25(3): 854-866. DOI:10.1007/s10924-016-0865-5 (  0) 0) |

Itoh, Y., Watanabe, J., Fukada, H., Mizuno, R., Kezuka, Y., Nonaka, T., et al., 2006. Importance of Trp59 and Trp60 in chitinbinding, hydrolytic, and antifungal activities of Streptomyces griseus chitinase C. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 72(6): 1176-1184. DOI:10.1007/s00253-006-0405-7 (  0) 0) |

Juárez-Hernández, E. O., Casados-Vázquez, L. E., Brieba, L. G., Torres-Larios, A., Jimenez-Sandoval, P., and Barboza-Corona, J. E., 2019. The crystal structure of the chitinase ChiA74 of Bacillus thuringiensis has a multidomain assembly. Scientific Reports, 9: 2591. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-39464-z (  0) 0) |

Kumar, M., Madhuprakash, J., Balan, V., Singh, A. K., Vivekanand, V., and Pareek, N., 2021. Chemoenzymatic production of chitooligosaccharides employing ionic liquids and Thermomyces lanuginosus chitinase. Bioresource Technology, 337: 125399. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125399 (  0) 0) |

Li, J., Huang, W. C., Gao, L., Sun, J. A., Liu, Z., and Mao, X. Z., 2019. Efficient enzymatic hydrolysis of ionic liquid pretreated chitin and its dissolution mechanism. Carbohydrate Polymers, 211: 329-335. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.02.027 (  0) 0) |

Li, Z., Pan, X., Yang, Y., Liu, Z., Xu, L., He, S., et al., 2017. Studies on the efficient secretion of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases CBP21 and its synergism with chitinase. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 19(1): 58-65. (  0) 0) |

Liu, J. W., Xu, Q., Wu, Y., Sun, D., Zhu, J. R., Liu, C., et al., 2023a. Carbohydrate-binding modules of ChiB and ChiC promote the chitinolytic system of Serratia marcescens BWL1001. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 162: 110118. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2022.110118 (  0) 0) |

Liu, Y. H., Qin, Z., Wang, C. L., and Jiang, Z. Q., 2023b. N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-based oligosaccharides from chitin: Enzymatic production, characterization and biological activities. Carbohydrate Polymers, 315: 121019. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121019 (  0) 0) |

Lv, C. Y., Gu, T. Y., Ma, R., Yao, W., Huang, Y. Y., Gu, J. G., et al., 2021. Biochemical characterization of a GH19 chitinase from Streptomyces alfalfae and its applications in crystalline chitin conversion and biocontrol. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 167: 193-201. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.11.178 (  0) 0) |

Ma, L., Liu, Z. Y., Kong, Z. J., Wang, M. M., Li, T., Zhu, H., et al., 2021. Functional characterization of a novel copper-dependent lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase TgAA11 from Trichoderma guizhouense NJAU 4742 in the oxidative degradation of chitin. Carbohydrate Polymers, 258: 117708. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117708 (  0) 0) |

Mahajan, G., Sharma, V., and Gupta, R., 2024. Chitinase: A potent biocatalyst and its diverse applications. Biocatalysis and Biotransformation, 42(2): 85-109. DOI:10.1080/10242422.2023.2218524 (  0) 0) |

Malecki, P. H., Bejger, M., Rypniewski, W., and Vorgias, C. E., 2020. The crystal structure of a Streptomyces thermoviolaceus thermophilic chitinase known for its refolding efficiency. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21: 2892. DOI:10.3390/ijms21082892 (  0) 0) |

Mathew, G. M., Madhavan, A., Arun, K. B., Sindhu, R., Binod, P., Singhania, R. R., et al., 2021. Thermophilic chitinases: Structural, functional and engineering attributes for industrial applications. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 193(1): 142-164. DOI:10.1007/s12010-020-03416-5 (  0) 0) |

Matroodi, S., Motallebi, M., Zamani, M., and Moradyar, M., 2013. Designing a new chitinase with more chitin binding and antifungal activity. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, 29(8): 1517-1523. DOI:10.1007/s11274-013-1318-0 (  0) 0) |

Mekasha, S., Tuveng, T. R., Askarian, F., Choudhary, S., Schmidt-Dannert, C., Niebisch, A., et al., 2020. A trimodular bacterial enzyme combining hydrolytic activity with oxidative glycosidic bond cleavage efficiently degrades chitin. Journal of Biolo- gical Chemistry, 295(27): 9134-9146. DOI:10.1074/jbc.RA120.013040 (  0) 0) |

Mukherjee, S., Behera, P. K., and Madhuprakash, J., 2020. Efficient conversion of crystalline chitin to N-acetylglucosamine and N, N′-diacetylchitobiose by the enzyme cocktail produced by Paenibacillus sp. LS1. Carbohydrate Polymers, 250: 116889. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116889 (  0) 0) |

Nakagawa, Y. S., Kudo, M., Onodera, R., Ang, L. Z. P., Watanabe, T., Totani, K., et al., 2020. Analysis of four chitin-active lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases from Streptomyces griseus reveals functional variation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 68(47): 13641-13650. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05319 (  0) 0) |

Nhung, N. T., and Doucet, N., 2016. Combining chitinase C and N-acetylhexosaminidase from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) provides an efficient way to synthesize N-acetylglucosamine from crystalline chitin. Journal of Biotechnology, 220: 25-32. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.12.038 (  0) 0) |

Nyok-Sean, L., and Furusawa, G., 2024. Polysaccharide degradation in Cellvibrionaceae: Genomic insights of the novel chitin-degrading marine bacterium, strain KSP-S5-2, and its chitinolytic activity. Science of the Total Environment, 912: 169134. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169134 (  0) 0) |

Pan, D. L., Liu, J. Z., Xiao, P. Y., Xie, Y. K., Zhou, X. L., and Zhang, Y., 2023. Research progress of lytic chitin monooxygenase and its utilization in chitin resource fermentation transformation. Fermentation-Basel, 9: 754. DOI:10.3390/fermentation9080754 (  0) 0) |

Pentekhina, I., Hattori, T., Tran, D. M., Shima, M., Watanabe, T., Sugimoto, H., et al., 2020. Chitinase system of Aeromonas salmonicida, and characterization of enzymes involved in chitin degradation. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 84(9): 1936-1947. DOI:10.1080/09168451.2020.1771539 (  0) 0) |

Pham, T. A., Luu, T. H., Dam, T. H., and To, K. A., 2024. Bioconversion of shrimp waste into functional lipid by a new oleaginous Sakaguchia sp. Molecular Biotechnology. DOI:10.1007/s12033-023-01014-4 (  0) 0) |

Poria, V., Rana, A., Kumari, A., Grewal, J., Pranaw, K., and Singh, S., 2021. Current perspectives on chitinolytic enzymes and their agro-industrial applications. Biology-Basel, 10: 1319. DOI:10.3390/biology10121319 (  0) 0) |

Qiu, S. T., Zhou, S. P., Tan, Y., Feng, J. Y., Bai, Y., He, J. C., et al., 2022. Biodegradation and prospect of polysaccharide from crustaceans. Marine Drugs, 20(5): 310. DOI:10.3390/md20050310 (  0) 0) |

Qu, M., Watanabe-Nakayama, T., Sun, S. P., Umeda, K., Guo, X. X., Liu, Y. S., et al., 2020. High-speed atomic force microscopy reveals factors affecting the processivity of chitinases during interfacial enzymatic hydrolysis of crystalline chitin. ACS Catalysis, 10(22): 13606-13615. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c02751 (  0) 0) |

Rani, T. S., Madhuprakash, J., and Podile, A. R., 2020. Chitinase-E from Chitiniphilus shinanonensis generates chitobiose from chitin flakes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 163: 1037-1043. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.052 (  0) 0) |

Ren, X. B., Dang, Y. R., Liu, S. S., Huang, K. X., Qin, Q. L., Chen, X. L., et al., 2022. Identification and characterization of three chitinases with potential in direct conversion of crystalline chitin into N, N′-diacetylchitobiose. Marine Drugs, 20(3): 165. DOI:10.3390/md20030165 (  0) 0) |

Rinaudo, M., 2006. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applica- tions. Progress in Polymer Science, 31(7): 603-632. DOI:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.06.001 (  0) 0) |

Sato, H., Sonoda, N., Nakano, M., Matsuyama, Y., Shizume, A., Arai, R., et al., 2023. Multi-enzyme machinery for chitin de- gradation in the chitinolytic bacterium Chitiniphilus shinano- nensis SAY3T. Current Microbiology, 80(11): 360. DOI:10.1007/s00284-023-03489-5 (  0) 0) |

Song, W., Zhang, N., Yang, M., Zhou, Y. L., He, N. S., and Zhang, G. M., 2020. Multiple strategies to improve the yield of chi- tinase a from Bacillus licheniformis in Pichia pastoris to obtain plant growth enhancer and GlcNAc. Microbial Cell Factories, 19: 181. DOI:10.1186/s12934-020-01440-y (  0) 0) |

Su, H. P., Gao, L., Sun, J. A., and Mao, X. Z., 2021. Engineering a carbohydrate binding module to enhance chitinase catalytic efficiency on insoluble chitinous substrate. Food Chemistry, 355: 129462. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129462 (  0) 0) |

Subramani, A. K., Ramachandra, R., Thote, S., Govindaraj, V., Vanzara, P., Raval, R., et al., 2024. Engineering a recombinant chitinase from the marine bacterium Bacillus aryabhattai with targeted activity on insoluble crystalline chitin for chitin oligo- mer production. International Journal of Biological Macro- molecules, 264(Pt 2): 130499. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024 (  0) 0) |

Subramani, A. K., Raval, R., Sundareshan, S., Sivasengh, R., and Raval, K., 2022. A marine chitinase from Bacillus aryabhattai with antifungal activity and broad specificity toward crystalline chitin degradation. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology, 52(10): 1160-1172. DOI:10.1080/10826068.2022.2033994 (  0) 0) |

Sun, B., Zhao, X. C., Xu, B. R., Su, E. Z., Kovalevsky, A., Shen, Q. R., et al., 2023. Discovering and designing a chimeric hyperthermophilic chitinase for crystalline chitin degradation. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 11(12): 4690-4698. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c07050 (  0) 0) |

Tabassum, N., Ahmed, S., and Ali, M. A., 2021. Chitooligosaccharides and their structural-functional effect on hydrogels: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers, 261: 117882. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117882 (  0) 0) |

Takashima, T., Ohnuma, T., and Fukamizo, T., 2018. NMR analysis of substrate binding to a two-domain chitinase: Comparison between soluble and insoluble chitins. Carbohydrate Research, 458: 52-59. DOI:10.1016/j.carres.2018.02.004 (  0) 0) |

Tallant, C., Marrero, A., and Gomis-Rüth, F. X., 2010. Matrix metal-loproteinases: Fold and function of their catalytic domains. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Molecular Cell Research, 1803(1): 20-28. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.04.003 (  0) 0) |

Thomas, R., Fukamizo, T., and Suginta, W., 2022. Bioeconomic production of high-quality chitobiose from chitin food wastes using an in-house chitinase from Vibrio campbellii. Bioresources and Bioprocessing, 9(1): 86. DOI:10.1186/s40643-022-00574-8 (  0) 0) |

Tran, D. M., Huynh, T. U., Nguyen, T. H., Do, T. O., Pentekhina, I., Nguyen, Q. V., et al., 2022. Expression, purification, and basic properties of a novel domain structure possessing chitinase from Escherichia coli carrying the family 18 chitinase gene of Bacillus velezensis strain RB. IBE 29. Molecular Biology Reports, 49(5): 4141-4148. DOI:10.1007/s11033-022-07471-5 (  0) 0) |

Tran, T. N., Doan, C. T., Nguyen, M. T., Nguyen, V. B., Vo, T. P. K., Nguyen, A. D., et al., 2019. An Exochitinase with N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase-like activity from shrimp head conversion by Streptomyces speibonae and its application in hydrolyzing β-Chitin powder to produce N-acetyl-D-glucosamine. Polymers, 11(10): 1600. DOI:10.3390/polym11101600 (  0) 0) |

Tsurkan, M. H., Voronkina, A. L. N., Khrunyk, Y. L. Y., Wysokowski, M. R. C., Petrenko, A., and Ehrlich, E. M., 2021. Progress in chitin analytics. Carbohydrate Polymers, 252: 117204. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117204 (  0) 0) |

Wang, C. Y., Chen, X. M., Zhou, N., Chen, Y., Zhang, A. L., Chen, K. Q., et al., 2022. Property and function of a novel chitinase containing dual catalytic domains capable of converting chitin into N-acetyl-D-glucosamine. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13: 790301. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.790301 (  0) 0) |

Wang, J. R., Zhu, M. J., Wang, P., and Chen, W., 2023. Biochemical properties of a cold-active chitinase from marine Trichoderma gamsii R1 and its application to preparation of chitin oligosaccharides. Marine Drugs, 21(6): 332. DOI:10.3390/md21060332 (  0) 0) |

Wu, X., Wang, J., Shi, Y. Q., Chen, S., Yan, Q. J., Jiang, Z. Q., et al., 2017. N-acetyl-chitobiose ameliorates metabolism dysfunction through Erk/p38 MAPK and histone H3 phosphorylation in type 2 diabetes mice. Journal of Functional Foods, 28: 96-105. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2016.11.012 (  0) 0) |

Xie, X. H., Fu, X., Yan, X. Y., Peng, W. F., and Kang, L. X., 2021. A broad-specificity chitinase from Penicillium oxalicum k10 exhibits antifungal activity and biodegradation properties of chitin. Marine Drugs, 19(7): 356. DOI:10.3390/md19070356 (  0) 0) |

Xing, A., Secundo, F., Xue, C., Hu, Y., and Mao, X., 2024. Green and efficient preparation of nano-chitin for enzymatic preparation of N-acetylchitooligosaccharides. ACS Sustainable Resource Management, 1(1): 88-96. DOI:10.1021/acssusresmgt.3c00044 (  0) 0) |

Xing, A. J., Hu, Y., Wang, W., Secundo, F., Xue, C. H., and Mao, X. Z., 2023. A novel microbial-derived family 19 endochitinase with exochitinase activity and its immobilization. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 107(11): 3565-3578. DOI:10.1007/s00253-023-12523-2 (  0) 0) |

Xu, S. Q., Qiu, M. L., Zhang, X. Y., and Chen, J. H., 2017. Expression and characterization of an enhanced recombinant heparinase I with chitin binding domain. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 105: 1250-1258. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.158 (  0) 0) |

Yadav, M., Goswami, P., Paritosh, K., Kumar, M., Pareek, N., and Vivekanand, V., 2019. Seafood waste: A source for preparation of commercially employable chitin/chitosan materials. Bioresources and Bioprocessing, 6: 8. DOI:10.1186/s40643-019-0243-y (  0) 0) |

Yin, H., Du, Y. G., and Dong, Z. M., 2016. Chitin oligosaccharide and chitosan oligosaccharide: Two similar but different plant elicitors. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7: 522. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2016.00522 (  0) 0) |

Younes, I., and Rinaudo, M., 2015. Chitin and chitosan preparation from marine sources. Structure, properties and applications. Marine Drugs, 13(3): 1133-1174. DOI:10.3390/md13031133 (  0) 0) |

Zakariassen, H., Aam, B. B., Horn, S. J., Vårum, K. M., Sorlie, M., and Eijsink, V. G. H., 2009. Aromatic residues in the catalytic center of chitinase A from Serratia marcescens affect processivity, Enzyme activity, and biomass converting efficiency. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284(16): 10610-10617. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M900092200 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, A., Wei, G. G., Mo, X. F., Zhou, N., Chen, K. Q., and Ouyang, P. K., 2018. Enzymatic hydrolysis of chitin pretreated by bacterial fermentation to obtain pure N-acetyl-D-glucosamine. Green Chemistry, 20(10): 2320-2327. DOI:10.1039/c8gc00265g (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Q., Zhang, X. Y., He, Y. C., and Li, Y. C., 2023. The synergistic action of two chitinases from Vibrio harveyi on chitin degradation. Carbohydrate Polymers, 307: 120640. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.120640 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, W. J., Ma, J. W., Yan, Q. J., Jiang, Z. Q., and Yang, S. Q., 2021. Biochemical characterization of a novel acidic chitinase with antifungal activity from Paenibacillus xylanexedens Z2-4. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 182: 1528-1536. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.111 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, H. J., Su, H. P., Sun, J. A., Dong, H., and Mao, X. Z., 2024. Bioconversion of α-Chitin by a lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase OsLPMO10A coupled with chitinases and the synergistic mechanism analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 72(13): 7256-7265. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c08688 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Q., Fan, L. Q., Deng, C., Ma, C. Y., Zhang, C. Y., and Zhao, L. M., 2023a. Bioconversion of chitin into chitin oligosaccharides using a novel chitinase with high chitin-binding capacity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 244: 125 241. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125241 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, S., Liu, M. Y., Sun, X. M., Jiang, X. K., Li, Y. J., Wu, X. Y., et al., 2023b. Engineering the relatively conserved residues in active site architecture of thermophilic chitinase SsChi18A enhanced catalytic activity. Biomacromolecules, 25(1): 238-247. DOI:10.1021/acs.biomac.3c00936 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, J. S., Chen, L. L., Kang, L. Q., Liu, Z. H., Bai, Y., Yang, Y., et al., 2018. ChiE1 from Coprinopsis cinerea is characterized as a processive exochitinase and revealed to have a significant synergistic action with endochitinase Chilll on chitin degradation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 66(48): 12773-12782. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04261 (  0) 0) |

2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23