2) First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao 266061, China;

3) Technology Innovation Center for Ocean Telemetry, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao 266061, China

Oceanic internal waves widely exist in all major oceans of the world; as a special internal wave, internal solitary waves (ISWs) are crucial aspects of seawater motion (Alford et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021). With the development of satellite remote sensing technology, owing to their advantages of wide spatial coverage, rich data sources, relatively high resolution, simple access to information, and intuitive information recorded on the images, remote sensing image data are increasingly utilized in the observation and research of ISWs (Jackson, 2007).

Free surface displacement has been confirmed to be attributed to ISWs. With the development of remote sensing technology, this phenomenon has also been proven by the research of altimeters on ISWs. The synergistic effect of satellite altimeter data and SAR images detected by synthetic aperture radar have been used to identify ISWs, revealing that traditional altimeters could be used to detect ISWs (Da Silva and Cerqueira, 2016; Magalhaes and Da Silva, 2017). The SAR altimeter on Sentinel-3A can be used to detect short-period ISWs; the surface waves induced by ISWs result in considerable perturbations in the SAR altimeter echoes in the presence of ISWs, and the maximum amplitude of the surface waves corresponds to the maximum value of the sea level anomaly (Santos-Ferreira et al., 2018). Zhang et al. (2022) conducted laboratory experiments and UG simulations to investigate the role of the surface waves induced by ISWs in optical imaging. They found that different surface waves are induced by various types of ISWs, with the concave ISWs creating the convex surface waves, revealing the bright-dark mode in the optical image. By contrast, the concave surface waves are formed by the convex ISWs, exhibiting the dark-bright mode.

Cox and Munk analyzed sunglint using aerial photographs by statistics to the slope surface of the distribution. They found that the ocean surface roughness and imaging geometry (the position of the sun, sensors, the observation direction) influence the intensity of sunglint, which can be described by the probability distribution of reflective surface slope and the approximation distribution of Gaussian distribution (Cox and Munk, 1954, 1956; Munk et al., 2000). Chapman (1981) used the theory of Cox and Munk, which utilizes the root mean square slope of the sea surface to describe the relative visibility of ocean surface disturbances, to develop a model of the observed conditions and sea surface parameters. Melsheimer and Kwoh (2001) examined the relationships between the brightness and darkness of sea surface elements in optical remote sensing images and the roughness of the ocean surface. They found that the tilted water surface mirror reflected the sunlight into the sensor at an appropriate angle and that the tilt of the sea surface elements changed with the sea surface roughness, leading to variations in brightness and darkness of the ISWs in the optical remote sensing images.

Jackson and Alpers (2010) utilized MODIS remote sensing images to analyze the ISWs in the Andaman Sea and found various orders of bright and dark bands in different internal waves. They also explained sunglint and nonsunglint zones by defining the concept of critical sensor viewing angle and reversing the bright and dark features of ISWs during the passage of imaging geometry through this critical angle, that is, when the imaging position was in sunglint and nonsunglint zones, respectively. From the perspective of experiments, Zhang et al. (2019) revealed the reasons for the different imaging modes in sunglint and nonsunglint in optical remote sensing images. They found that under a fixed zenith angle of the light source, if the zenith angle of the sensor was between the two critical angles, then the ISWs would display the dark-bright mode; otherwise, it would be the bright-dark mode. Hu et al. (2021) analyzed the internal waves in the Celebes Sea area and studied the brightness reversal phenomenon of these waves in the continuous remote sensing images of the geostationary meteorological satellite Himawari-8. They found differences in the band characteristics of the internal waves in sunglint and the nonsunglint.

Scholars have discovered the different imaging characteristics of ISWs in the sunglint and nonsunglint, and the influence of the zenith angle of the light source on optical imaging characteristics of ISWs in sunglint is also a problem to be solved. However, available studies on this phenomenon are currently limited. This paper will investigate the optical imaging characteristics of ISWs with different zenith angles of light sources in sunglint based on physical simulation methods, providing a scientific basis for the design of optical remote sensing imaging in the future.

2 Design of ExperimentThe variation of the optical imaging characteristics of ISWs in sunglint with different zenith angles of the light source was studied in this paper based on the ISW simulation platform. As shown in Fig. 1, the main body of the simulation platform in the laboratory is a long straight tank with a rectangular cross-section, which is 500 cm long, 35 cm wide, and 80.6 cm high. Instead of the sun, a light-emitting diode (LED) light source is placed above the tank, and capturing the propagation process and optical images of ISWs relies on two CCDs. Instead of the sensor, one of the CCSDs is placed above the tank (i.e., CCD1) to obtain the optical images of ISWs, while the other one is located at the side of the tank (i.e., CCD2) to capture the propagation process of ISWs and obtain their waveforms. Computer control can be used to synchronize the two CCDs at 35 frames per second. In experiments, the gravitational collapse of stratified fluids in the tank typically generates ISWs. A baffle is positioned 20 cm away from the right edge of the tank, which is regarded as the wave-making area. With the quick vertical lifting of the baffle, the two layers of water with different gravitational potential energy will rapidly mix and form ISWs propagating to the left.

|

Fig. 1 Schematic of the simulation experiment platform. |

The consistency of irrelevant variables in multiple experiments is guaranteed by setting the depths of the upper layer −h1 and lower layer −h2 as −5 and −60 cm (minus for underwater), respectively, and the densities of the upper layer ρ1 and lower layer ρ2 as 1.02 and 1.06 g cm−3, respectively. After setting the required hydrological conditions, the zenith angles of the light source are adjusted by changing CCD1 and LED based on the principle of specular reflection. The relative azimuth angle is controlled to 180˚; that is, CCD1, LED, and the tank are in the same plane. Each group of experiments must take samples at a fixed position within the sunglint to ensure consistency in the background gray level of each experiment. The relative position of the sampling line within sunglint is scaled to the LED in equal proportion, and the imaging light source of the sampling line is defined by this position. H1 denotes the vertical distance from the imaging light source to the water surface, and L1 is the distance between the projection of this position on the water surface and the sampling line within sunglint. Similarly, the vertical distance from CCD1 to the water surface is denoted by H2, and the distance between the projection of CCD1 on the water surface and the sampling line within sunglint is denoted by L2. α and β are the sensor and light source zenith angles, respectively, which can be obtained by L1, L2, H1 and H2. In the experiment, LED and CCD1 can move in the X and Y directions, respectively, and their pitch angles can be modified. Therefore, controlling the relative positions of CCD1 and LED and their angles relative to the water surface enables the adjustment of the LED zenith angle in the experiment.

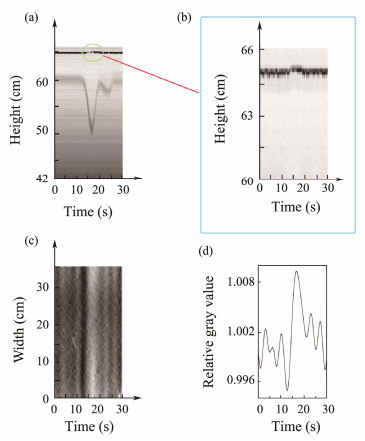

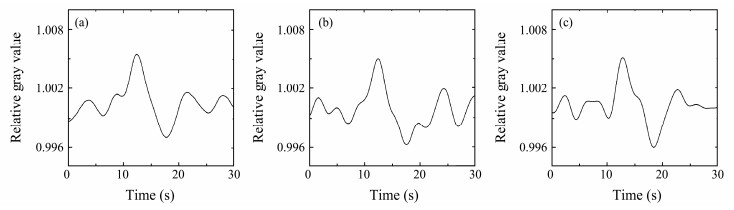

Ten sets of experiments are conducted in this paper to explore the influence of the change of the zenith angle of the light source on the optical imaging characteristics of ISWs in sunglint, and 10 zenith angles of the light source, which are 23.8˚, 32.7˚, 42.5˚, 50.7˚, 52.8˚, 57.9˚, 61.3˚, 62.5˚, 71.9˚, and 80.6˚, are set. The experiment generated mode-1 depression ISWs. As shown in Fig. 2, 1050 images are extracted from each group of experiments at the sampling locations to produce side waveform and surface optical images and analyze the characteristics of mode-1 depression ISWs. Fig. 2(a) is the waveform of mode-1 depression ISWs. In addition to the surface flow field variations ge-nerated by ISWs, the surface waves induced by ISWs also have a certain impact on the optical image characteristics, and the waveform of the surface wave is presented in Fig. 2(b). Fig. 2(c) is the band induced by the propagation of mode-1 depression ISWs in an optical image. The gray value of 20 lines at the center of the band in Fig. 2(c) is averaged, and the gray value is then compared with the background gray value to obtain the relative gray value curve, which is the result in Fig. 2(d).

|

Fig. 2 Mode-1 depression ISWs and the optical imaging of physical simulation. (a) Waveform of mode-1 depression ISWs. (b) Waveform of the surface wave caused by ISWs. (c) Optical imaging of mode-1 depression ISWs. (d) Relative gray value curve of the band in optical imaging. |

This section discusses the effects of different zenith angles of the light source on the imaging characteristics in the optical images of ISWs, such as the order of the band in images, symmetry of dark and bright bands, the relative gray value difference, and contrast degree of dark and bright bands.

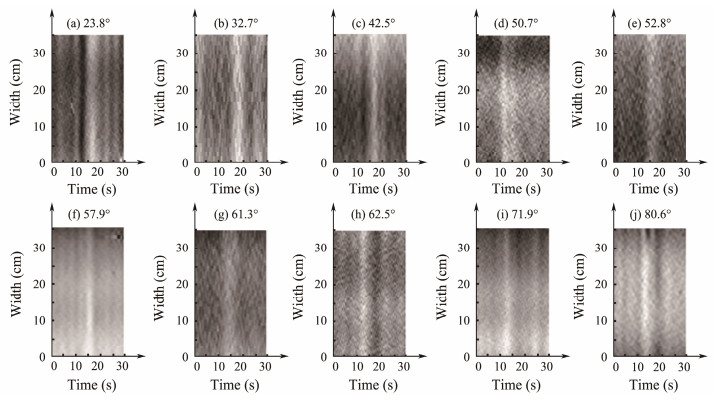

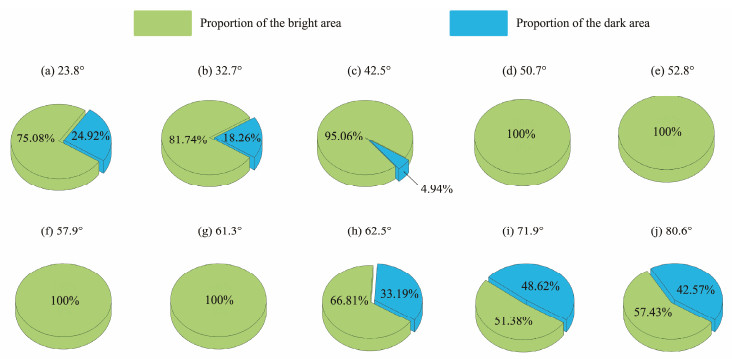

3.1 Effect of Different Zenith Angles of the Light Source on Image BandsThe zenith angles of the light source at 23.8˚, 32.7˚, 42.5˚, 50.7˚, 52.8˚, 57.9˚, 61.3˚, 62.5˚, 71.9˚, and 80.6˚ generated ISWs, and the height of collapse is fixed at 20 cm. The bands in the optical images of ISWS are shown in Fig. 3. This figure reveals that the process of increasing the zenith angle of the light source induces gradual changes in the order of the bands in the optical images of ISWs from the clear dark-bright mode to the single bright bands, and then progressively to the bright-dark mode. The three features of the bands in the optical images indicate that the 10 angles are divided into area a (23.8˚, 32.7˚, 42.5˚), area b (50.7˚, 52.8˚, 57.9˚, 61.3˚), and area c (62.5˚, 71.9˚, 80.6˚).

|

Fig. 3 Optical images of ISWs at 10 zenith angles of the light source. (a)–(j) are the optical images of ISWs at the zenith angles of 23.8˚, 32.7˚, 42.5˚, 50.7˚, 52.8˚, 57.9˚, 61.3˚, 62.5˚, 71.9˚, and 80.6˚, respectively. |

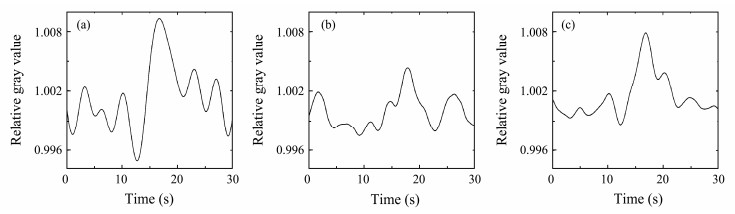

Figs. 4a–c shows the relative gray value curves for the three zenith angles corresponding to the bands in Fig. 3 when the zenith angle of the light source is small, that is, 23.8˚, 32.7˚, and 42.5˚ (called area a) in this experiment. Figure 4 reveals the visible orders of the bands in the optical images of ISWs, revealing the clear dark-bright mode and the two symmetrical peaks of the gray value at the bands to the background. As shown in Fig. 4, considering the relative gray curve corresponding to the band at the zenith angle of 23.8˚, the symmetry of its two peaks relative to the background is superior to that under the zenith angles of 32.7˚ and 42.5˚, and the difference between the peak of the relative gray curve and the background is also large. However, the relative gray curve of the zenith angle of 32.7˚ is worse than that of the zenith angle of 42.5˚. An assumption lies in the deterioration of optical imaging under the zenith angle of 32.7˚ due to external factors.

|

Fig. 4 Relative gray value curves of the bands in optical imaging corresponding to ISWs in Fig. 3 when the zenith angles of the light source are 23.8˚ (a), 32.7˚ (b), and 42.5˚ (c). |

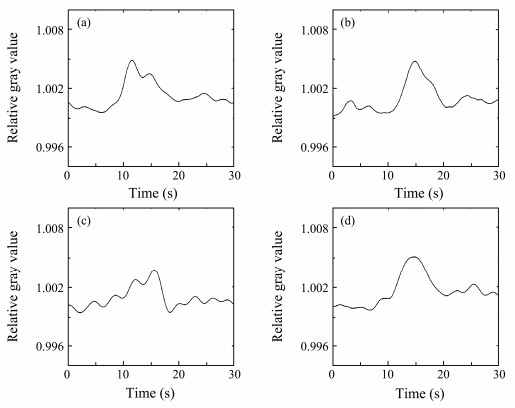

The relative gray value curve of the band is different from that of area a when the zenith angle of the light source increases. The relative gray value curves when the zenith angles of the light source are 50.7˚, 52.8˚, 57.9˚, and 61.3˚ (called area b) are shown in Fig. 5. Determining the orders of bands in optical images is challenging. In addition, considering the background, the relative gray value curves at the band display poor symmetry. These curves only demonstrated the part brighter than the background, while the part darker than the background cannot be observed. That is, compared with the background, the relative gray value curves have only one peak value, and only a single bright band can be characterized. The relative gray value curve of the band changes compared with that at area a as the zenith angle of the light source increases.

|

Fig. 5 Relative gray value curves of the bands in optical imaging corresponding to ISWs in Fig. 3 when the zenith angles of the light source are 50.7˚ (a), 52.8˚ (b), 57.9˚ (c), and 61.3˚ (d). |

The order of the bands in the optical imaging of ISWs changes again with the increase in the zenith angle of the light source, that is, 62.5˚, 71.9˚, and 80.6˚ (called area c) in this experiment. Figs. 6(a)–(d) shows the relative gray curves corresponding to the bands in Fig. 3 under the four zenith angles. Compared with area b, Fig. 6 shows that the bands of ISWs become visible again, and the symmetry between the two peaks of the relative gray value curve at the band and the background is as good as that of area A. However, the order of the bands is the bright-dark mode, which is the opposite of area A. The orders of the bands in the optical imaging of ISWs are reversed compared with that of areas A and B when the zenith single of the light source is large.

|

Fig. 6 Relative gray value curves of the bands in optical imaging corresponding to ISWs in Fig. 3 when the zenith angles of the light source are 62.5˚ (a), 71.9˚ (b), and 80.6˚ (c). |

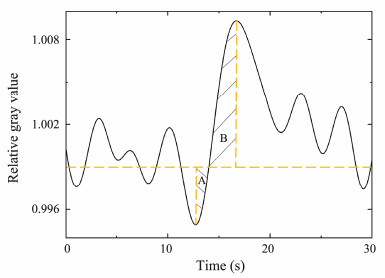

Taking the relative gray value curve when the zenith angle of the light source is 23.8˚ as an example, Fig. 7 shows the calculation of the intersection area between the two peaks of the relative gray value curve and the background. The areas of regions A and B are the dark and bright parts, respectively. Fig. 8 illustrates pie charts of the proportions of the bright and dark areas under 10 zenith angles of the light source in the experiment to explore the contrast degree of bright and dark parts of the bands in the optical images of ISWs under different zenith angles of the light source. In this figure, the green part denotes the significance of the proportion of the area of region B to the sum of the areas of A and B in Fig. 7, that is, the percentage of the bright area. Similarly, the proportion of the area of region A to the sum of the areas of A and B in Fig. 7 is denoted by the blue, that is, the proportion of the dark area. Fig. 8 shows that when in area A, the proportion of the bright area is larger than that of the dark area, and the dif-ference between the two gradually increases with the angle. This finding explains that from Figs. 3(a)–(c), the bright band gradually emerges, and the dark band becomes increasingly blurred. The proportion of the bright area in area B reaches 100%; that is, the relative gray value curves of the band in the optical images can only observe the brighter part than the background, and the darker part cannot be observed. This finding is also consistent with the pheno-menon in Figs. 3(d)–(f); that is, the optical image only demonstrates one bright band. The proportion of the bright part gradually decreases when the zenith angle of the light source is in area C. However, the proportion of the dark area suddenly increases when the zenith angle of the light source is 71.9˚, presumably due to external interference, which should actually be consistent with the trend of gradually decreasing the percentage of the bright part. Figs. 3(g)–(j) also demonstrates this phenomenon; that is, the dark bands are becoming increasingly evident.

|

Fig. 7 Schematic of the proportion of bright and dark areas when the zenith angle of the light source is 23.8˚. |

|

Fig. 8 Proportion of the dark and bright bands in ISW optical imaging when the zenith angle of the light source is different. (a)–(j) Pie chart of the percentage of the bright and dark areas in the optical imaging of ISWs under 10 zenith angles of the light source in the experiment. |

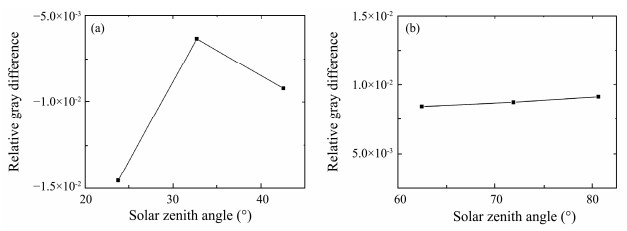

Establishing a curve of the relative gray difference with the variation of the zenith angle of the light sources is necessary to investigate the variation effect of the zenith angle of the light sources in areas A and C on the relative gray difference of the bands in the optical images in the experiment. The variation of the relative gray difference with the zenith angle of the light source in areas A and C is shown in Figs. 9(a) and (b), respectively. The relative gray difference is negative when the zenith angle of the light source is small, and the bands show the dark-bright mode. Moreover, the absolute value of the relative gray difference is large when the zenith angle is small. However, the absolute value of the relative gray difference under the condition of 32.7˚ is smaller than that under the condition of 42.5˚, which may be due to external factors. When the zenith angle of the light source is large, that is, in area B, the relative gray difference is positive, and the bands display the bright-dark mode, and the absolute value of the relative gray difference shows a gradually increasing trend. This finding can also explain the phenomenon in Fig. 3; that is, the contrast between the bright and dark bands in optical images in area C gradually increases with the zenith angle of the light source.

|

Fig. 9 Variation of relative gray difference of the bands in optical images of ISWs in area A (a) and area C (b). |

This section compares the curves simulated by KdV (Korteweg-de Vries), eKdV (extended KdV), mKdV (modified KdV), BO (Buchdahl-Osborne), and MCC (Miyata-Choi-Camassa) with the waveforms in the experiment. The relationship between the brightness-darkness distance and the characteristic half-width in SAR images based on the eKdV theory is derived, and the relationships between the brightness-darkness distance and the characteristic half-width in the optical images of ISWs in the experiment are analyzed.

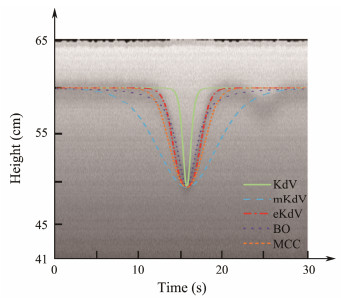

4.1 Experimental and Theoretical Comparison of the Waveform of ISWsFig. 10 shows the propagation process of ISWs captured by CCD2 when the zenith angle of the light source is 71.9˚. The waveform reveals that the amplitude of ISWs is approximately 9.8 cm. The curves simulated by the KdV, eKdV, mKdV, BO, and MCC theories, which correspond to the waveform of ISWs, are obtained by taking the same time. The curve simulated by the eKdV theory is close to the experimental result because the amplitude of ISWs generated by the above stratification in the experiment is close to the condition of medium amplitude. The curves simulated by the KdV and BO theories are suitable for small amplitude, while the curve simulated by the mKdV theory is suitable for large amplitude. The MCC theory is more suitable for strong nonlinear conditions than for weak nonlinear conditions in experiments. In addition, the groups of experiments still maintained the water depth, density, and other conditions despite changes in the zenith angles of the light source. Therefore, the amplitudes of ISWs generated in each group are approximately equal, and the waveforms are all suitable for the curves simulated by the eKdV theory.

|

Fig. 10 ISW waveform captured by CCD2 at the zenith angle of the light source of 71.9˚ and curves simulated by five equations. The green solid line denotes the result of the KdV theory, the red dash-dot line denotes the result of the eKdV theory, the blue dash line denotes the result of the mKdV theory, the violet dot line denotes the result of the BO theory, and the orange short dash line denotes the result of the MCC theory. |

The balance between the nonlinear and dispersion effects on a certain scale results in the stable propagation of ISWs, which can be described by theoretical models such as KdV, eKdV, and mKdV. Among them, the solution of the eKdV equation provides information on the wave pattern, propagation velocity, and characteristic half-width of ISWs (Helfrich and Melville, 2006).

| $ \eta (x, t) = \frac{{{\eta _0}}}{{B + (1 - B){{\cosh }^2}\left[ {\left({x - {c_{\text{e}}}_{{\text{KdV}}}t} \right)/{L_{\text{e}}}_{{\text{KdV}}}} \right]}}, $ | (1) |

| $ {c_0} = {\left({\frac{{g({\rho _2} - {\rho _1}){h_1}{h_2}}}{{{\rho _2}{h_1} + {\rho _1}{h_2}}}} \right)^{1/2}}, $ | (2) |

| $ {c_{eKdV}} = {c_0} + \frac{{{\eta _0}}}{3}\left({\alpha + \frac{{{\alpha _1}{\eta _0}}}{2}} \right), $ | (3) |

| $ {{\text{L}}_{eKdV}} = \sqrt {\frac{{12\beta }}{{{\eta _0}\left({\alpha + {\alpha _1}{\eta _0}/2} \right)}}}, $ | (4) |

| $ \alpha = \frac{3}{2}\frac{{{c_0}}}{{{h_1}{h_2}}}\frac{{{\rho _2}h_1^2 - {\rho _1}h_2^2}}{{{\rho _2}{h_1} + {\rho _1}{h_2}}}, $ | (5) |

| $ \beta = \frac{{{{\text{c}}_0}{h_1}{h_2}}}{6}\frac{{{\rho _1}{h_1} + {\rho _2}{h_2}}}{{{\rho _2}{h_1} + {\rho _1}{h_2}}}, $ | (6) |

| $ {\alpha _1} = \frac{{{c_0}}}{{h_1^2h_2^2}}\left[ {\frac{7}{8}\left({\frac{{{\rho _1}h_2^2 - {\rho _2}h_1^2}}{{{\rho _2}{h_1} + {\rho _1}{h_2}}}} \right) - \left({\frac{{{\rho _2}h_1^3 + {\rho _1}h_2^3}}{{{\rho _2}{h_1} + {\rho _1}{h_2}}}} \right)} \right], $ | (7) |

| $ B = \frac{{ - {\alpha _1}{\eta _0}}}{{2\alpha + {\alpha _1}{\eta _0}}}, $ | (8) |

where η(x, y) is the vertical displacement in the boundary layer of water, η0 is the maximum displacement of ISWs, c0 is the linear phase speed of ISWs, ceKdV is the nonlinear phase speed of ISWs, LeKdV is the characteristic half width of ISWs, and B is a parameter. In the equation, α is the nonlinear coefficient, α1 is the second-order nonlinear coefficient, and β represents the dispersion coefficient. These nonlinear and dispersion coefficients can be calculated by the thickness of the upper layer of water −h1, the thickness of the lower layer of water −h2, and the average density ρ1 of the upper layer of water and the average density ρ2 of the lower layer of water.

The passage of ISWs will facilitate changes in the sea surface flow field, and the velocity of its surface flow in the x-direction can be expressed as (Zheng et al., 1993, 2001):

| $ {U_x} = - {c_0}\eta /{h_1}. $ | (9) |

Integrating Eq. (1) into Eq. (9), the following can be obtained:

| $ {U_x} = \frac{{{c_0}{\eta _0}}}{{B + (1 - B){{\cosh }^2}\left[ {\left({x - {c_{\text{e}}}_{{\text{KdV}}}t} \right)/{L_{\text{e}}}_{{\text{KdV}}}} \right]}} . $ | (10) |

In the formula, the descending ISWs are indicated by the positive sign, and the ascending ISWs are represented by the negative sign. In the two-layer model, considering the Bragg scattering model, the modulation effect of the flow field produced by the ISWs on the ocean surface wave and the difference between the propagation direction of the ISWs and the viewing angle of the radar, the final ratio of the backscattered cross-section of the ISW flow field to that of the background field is (Hughes, 1978):

| $ \frac{{\Delta {\sigma ^0}}}{{\sigma _0^0}} = - \frac{{4 + \gamma }}{\mu }{\cos ^2}\varphi \frac{{\partial {U_x}}}{{\partial x}}, $ | (11) |

where γ is the ratio of Bragg wave group velocity to the phase velocity. For gravity wave, γ = 1/2; for the surface tension wave, γ = 2/3. Substituting Eq. (10) into Eq. (11), the following can be obtained (Jia et al., 2019):

| $ \frac{{\Delta {\sigma ^0}}}{{\sigma _0^0}} = \pm \frac{{4 + \gamma }}{\mu }\frac{{{c_0}{\eta _0}}}{{{h_1}}}{\cos ^2}\varphi \frac{{\sinh \left[ {2\left({x - {c_e}_{KdV}t} \right)/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right]}}{{B + (1 - B){{\cosh }^2}{{\left[ {\left({x - {c_e}_{KdV}t} \right)/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right]}^2}}}. $ | (12) |

Therefore, the relative variation of the gray values of the bands in the SAR image during the propagation of ISWs can be expressed as

| $ \frac{{\Delta I}}{I} = \frac{{\Delta {\sigma ^0}}}{{\sigma _0^0}} = E\frac{{\sinh \left({2x'/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right)}}{{{{\left[ {B + (1 - B){{\cosh }^2}\left({x'/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right)} \right]}^2}}}, $ | (13) |

where

According to Eq. (13), the maximum value (the brightest point) and the minimum value (the darkest point) of the gray value of ISW bands in the SAR images can be expressed as

| $ \frac{\partial }{{\partial x}}\left({\frac{{\Delta I}}{{{I_0}}}} \right) = E \times \frac{{2\cosh \left({2x'/{L_{KdV}}} \right)}}{{L \times {{\left[ {B - (B - 1){{\cosh }^2}\left({x'/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right)} \right]}^2}}} + \frac{{4\cosh \left({x'/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right)\sinh \left({x'/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right)\sinh \left({2x'/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right)\left({B - 1} \right)}}{{L \times {{\left[ {B - (B - 1){{\cosh }^2}\left({x'/{L_e}_{KdV}} \right)} \right]}^2}}} = 0. $ | (14) |

Eq. (8) shows the relationship between the parameter B and the amplitude. Therefore, according to the peak-to-peak method (Zheng et al., 2001), substituting the hydrological conditions in the experiment can help determine the relationship between the distance between the two peaks of the gray curves of the bands of ISWs (i.e., the brightness-darkness distance D) and the characteristic half width LeKdV (represented by D/LeKdV) on the SAR images with different amplitudes.

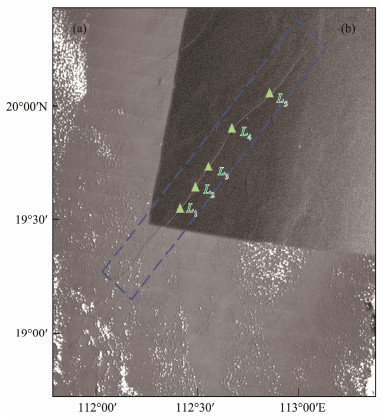

The relationship between D and LeKdV is derived from SAR images. Analyzing the relationship between D of the same ISWs on optical remote sensing and SAR images is necessary. The same ISWs observed in the southern part of Hainan Island by MODIS and ASAR images with a time difference of 53 min are shown in Fig. 11. This figure also shows the brightness-darkness distance calculated bythe two images at five positions (L1 19.50˚N, 112.35˚E; L2 19.60˚N, 112.44˚E; L3 19.72˚N, 112.48˚E; L4 19.91˚N, 112.66˚E; L5 20.11˚N, 112.90˚E). In the MODIS image, the brightness-darkness distance at L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5 are 664, 1288, 615, 988 and 615 m, respectively. In the ASAR image, the brightness-darkness distance at L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5 are 641, 1287, 589, 923, and 603 m, respectively. Variations in spatial resolution and temporal variations due to changes in ISWs can be attributed to the slight differences in the bright-dark distances at each location between the two images. The brightness-darkness distance of the same ISWs in the same position is similar in the two images because the convergence and divergence due to the same ISWs have the same effect in the two images. Therefore, the results obtained by Eq. (14) are applicable to optical images (Huang and Zhao, 2014).

|

Fig. 11 Same ISWs (located within the blue dashed box) are captured by MODIS image (a) at 03:15 UTC on May 31, 2011, and ASAR image (b) at 02:22 UTC on May 31, 2011 (Zhang and Li, 2022). The positions of five green triangles represent the locations of different extracted data. |

The hydrological conditions with different zenith angles of the light source are set similarly, but the amplitudes of ISWs generated by each group are slightly different. The relationship between D and LeKdV must be substituted into the amplitude according to the eKdV theory. Thus, the D/LeKdV under different amplitudes are calculated, and the D/LeKdV obtained from the images under different zenith angles of the light source in the experiment are counted, as shown in Table 1. The relative errors between the two are also computed under different zenith angles of the light source. The relative errors are between 7.7% and 13.2%, and the mean relative error is 9.8%. Therefore, the D/LeKdV calculated in the experiment is approximately consistent with the theoretical results; that is, the ISWs generated in the experiment are consistent with the eKdV theory.

|

|

Table 1 D/LeKdV and the relative errors from the eKdV theory and the experiment |

This paper is dedicated to investigating the various cha-racteristics of the optical images of ISWs in sunglint at different zenith angles. The laboratory tank performed simulations of real ocean conditions, generating ISWs. Ten sets of experiments with light source zenith angles of 23.8˚, 32.7˚, 42.5˚, 50.7˚, 52.8˚, 57.9˚, 61.3˚, 62.5˚, 71.9˚, and 80.6˚ are conducted by changing the position and angle of pitch of CCD1 and light source to obtain the optical image characteristics of ISWs at different zenith angles of the light source. This approach helps broaden the range of the angle in real remote sensing and provides a scientific basis for the design of optical remote sensing imaging in the future.

According to the different imaging characteristics, the zenith angles of the light source in the experiment are divided into areas A, B, and C. The experimental results show the following:

a) Varying zenith angles of light sources contribute to differences in the order of the bright and dark bands in optical imaging of ISWs. The pattern of the band is in the dark-bright mode when the zenith angle of the light source is in area A, and the relative gray curves of the bands have poor symmetry compared with the background. The relative gray value curve of the band is only brighter than the background when the zenith angle of the light source is in area B, and only a single bright band can be observed. The pattern of the band is the bright-dark mode when the zenith angle of the light source is in area C. The symmetry of the relative gray value curve of the band relative to the background improves as the zenith angle of the light source increases.

b) Under the condition of different zenith angles of the light source, the contrast degree between bright and dark bands of optical images of ISWs is different. When the zenith angle of the light source increases from small to large, the bright characteristics of the bands initially emerge until the proportion of bright bands reaches 100%, and then the proportion of bright bands is gradually comparable to that of dark bands.

c) As the zenith angle of the light source increases in area A, the absolute value of the relative gray difference will decrease. A deviation will be observed when the zenith angle is 32.7˚, which may be due to the interference of other factors in the experiment. As the zenith angle of the light source increases in area C, the absolute value of the relative gray difference increases.

d) Observation results of the same ISWs on the MODIS and ASAR images reveal similarities in the brightness-darkness distance. Therefore, the relationship between the brightness-darkness distance and the characteristic half-width derived from the SAR image can be applied to the optical image.

e) The relationship between D/LeKdV calculated by the experiment is consistent with that derived from the eKdV theory under different amplitude conditions. The difference between the two is small, and the mean relative error is only 9.8%. Thus, the ISWs generated in the experiment satisfy the eKdV theory. This finding indicates that ISWs with the large amplitude generated in the experiment satisfy the eKdV theory.

Overall, changes in the imaging characteristics of ISWs in sunglint can be attributed to differences in the zenith angles of the light source. Undoubtedly, the results of this study will help improve the understanding of optical images of ISWs in different seas and provide a scientific basis for the interpretation of optical remote sensing images of ISWs.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 61871353 and 42006 164) for their support.

Alford, M. H., Mickett, J. B., Zhang, S., MacCready, P., Zhao, Z., and Newton, J. A., 2012. Internal waves on the Washington continental shelf. Oceanography, 25: 66-79. DOI:10.5670/oceanog.2012.43 (  0) 0) |

Chapman, R. D., 1981. Visibility of rms slope variations on the sea surface. Applied Optics, 20(11): 1959-1966. DOI:10.1364/AO.20.001959 (  0) 0) |

Cox, C. S., and Munk, W. H., 1954. Measurement of the roughness of the sea surface from photographs of the Sun's glitter. Journal of the Optical Society of America, 44(11): 838-850. DOI:10.1364/JOSA.44.000838 (  0) 0) |

Cox, C. S., and Munk, W. H., 1956. Slopes of the sea surface de-duced from photographs of sun glitter. Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 69: 401-478. (  0) 0) |

Da Silva, J. C. B., and Cerqueira, A., 2016. A note on radar alti-meter signatures of internal solitary waves in the ocean. Conference on Remote Sensing of the Ocean, Sea Ice, Coastal Waters, and Large Water Regions. Edinburgh, 9999: 2-4.

(  0) 0) |

Helfrich, K. R., and Melville, W. K., 2006. Long nonlinear internal waves. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 38: 395-425. DOI:10.1146/annurev.fluid.38.050304.092129 (  0) 0) |

Hu, B. L., Meng, J. M., Sun, L. N., and Zhang, H., 2021. A study on brightness reversal of internal waves in the Celebes Sea using Himawari-8 images. Remote Sensing, 13(19): 3831. DOI:10.3390/rs13193831 (  0) 0) |

Huang, X. D., and Zhao, W., 2014. Inversion of internal solitary wave information based on MODIS image: A case study of the deep water area in the northern South China Sea. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 44(7): 19-23 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Hughes, B. A., 1978. The effect of internal waves on surface wind waves 2. Theoretical analysis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 83(C1): 455-465. DOI:10.1029/JC083iC01p00455 (  0) 0) |

Jackson, C. R., 2007. Internal wave detection using the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS). Journal of Geophysical Research, 112(C11): C11012. (  0) 0) |

Jackson, C. R., and Alpers, W., 2010. The role of the critical angle in brightness reversals on sunglint images of the sea surface. Journal of Geophysical Research, 115(C9): 19-28. (  0) 0) |

Jia, T., Liang, J., Li, X. M., and Fan, K., 2019. Retrieval of internal solitary wave amplitude in shallow water by tandem spaceborne SAR. Remote Sensing, 11(14): 1706. DOI:10.3390/rs11141706 (  0) 0) |

Magalhaes, J. M., and Da Silva, J. C. B., 2017. Satellite altime-try observations of large-scale internal solitary waves. IEEE Geoence and Remote Sensing Letters, 14(4): 534-538. DOI:10.1109/LGRS.2017.2655621 (  0) 0) |

Melsheimer, C., and Kwoh, L. K., 2001. Sun glitter in SPOT images and the visibility of oceanic phenomena. Proceedings of the 22nd Asian Conference on Remote Sensing. Singapore, 5 (9): 1-6.

(  0) 0) |

Munk, W., Armi, L., Fischer, K, and Zachariasen, F., 1997. Spi-rals on the sea. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 456: 1217-1280. (  0) 0) |

Santos-Ferreira, A. M., Da Silva, J. C. B., and Magalhaes, J. M., 2018. SAR mode altimetry observations of internal solitary waves in the tropical ocean Part 1: Case studies. Remote Sensing, 10(4): 644. DOI:10.3390/rs10040644 (  0) 0) |

Sun, L. N., Zhang, J., and Meng, J. M., 2021. Study on the propagation velocity of internal solitary waves in the Andaman Sea using Terra/Aqua-MODIS remote sensing images. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 39: 2195-2208. DOI:10.1007/s00343-020-0280-6 (  0) 0) |

Yang, Y. C., Huang, X. D., Zhao, W., Zhou, C., Huang, S. W., Zhang, Z. W., et al., 2021. Internal solitary waves in the Andaman Sea revealed by long-term mooring observations. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 51(12): 3609-3627. DOI:10.1175/JPO-D-20-0310.1 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, M., Wang, J., Chen, X., Mei, Y., and Zhang, X. D., 2019. An experimental study on the characteristic pattern of internal solitary waves in optical remote-sensing images. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 40(18): 7017-7032. DOI:10.1080/01431161.2019.1597308 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, M., Wang, J., Li, Z. X., Liang, K. D., and Chen, X., 2022. Laboratory study of the impact of the surface solitary waves created by the internal solitary waves on optical imaging. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 127(2): e2021JC017800. DOI:10.1029/2021JC017800 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, X. D., and Li, X. F., 2022. Satellite data-driven and know-ledge-informed machine learning model for estimating global internal solitary wave speed. Remote Sensing of Environment, 283: 113328. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2022.113328 (  0) 0) |

Zheng, Q. A., Yan, X. H., and Klemas, V., 1993. Statistical and dynamical analysis of internal waves on the continental shelf of the middle Atlantic bight from space shuttle photographs. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 98(C5): 8495-8504. DOI:10.1029/92JC02955 (  0) 0) |

Zheng, Q. A., Yuan, Y. L., Klemas, V., and Yan, X. H., 2001. Theoretical expression for an ocean internal soliton synthetic aperture radar image and determination of the soliton characteristic half width. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C12): 31415-31423. DOI:10.1029/2000JC000726 (  0) 0) |

2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23