2) Key Laboratory of Coastal Science and Engineering, Beibu Gulf, Guangxi, Beibu Gulf University, Qinzhou 535011, China;

3) Guangxi Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Science, Guangxi Beibu Gulf Marine Research Center, Guangxi Academy of Sciences, Nanning 530007, China;

4) Scientific and Technical Information Institution of Qinzhou City, Qinzhou 535011, China;

5) Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Resources Use in Beibu Gulf, Ministry of Education, Nanning Normal University, Nanning 530001, China

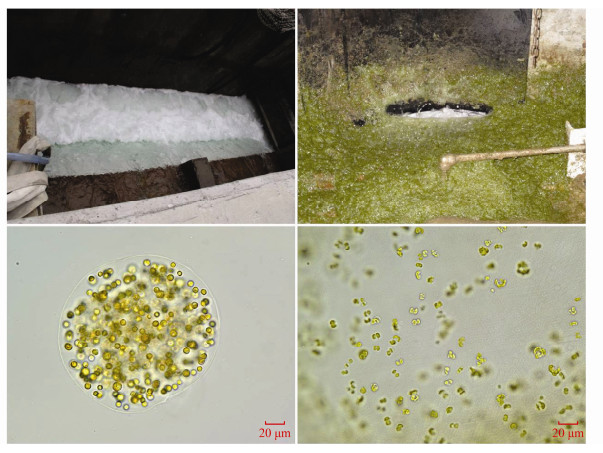

Rapid urbanization and industrial development, agriculture, mariculture, inshore eutrophication has become increasingly apparent (Kaiser et al., 2013; Lai et al., 2014), and the scale and duration of red tide have also significantly increased in the Beibu Gulf (Xu et al., 2019) in recent decades. Over the past eight years, a large scale of Phaeocystis globosa bloom occurred annually off Guangxi coastal waters in the Beibu Gulf (Gong et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019). The most striking feature of P. globosa is that it forms gel-like colonies ranging from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter (Verity et al., 2003), and produces viscous, slimy, and springy brown jelly layers, thus modifying the rheological properties of seawater. During the thermal test of the Fangchenggang Nuclear Power Plant (FCGNPP) from December 2014 to January 2015, there was an extensive outbreak of P. globosa bloom in Guangxi coastal waters, with a large number of high-density, high-colloid colonies blocking the cooling water filter system (Fig. 1) (Xu et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2018), posing a threat to the operational safety of the FCGNPP. This was the first case where the red tide organism affected the operational safety of a nuclear power plant around the world, and became surprising to the local government and the scientists because the Guangxi coastal waters is always regarded as the last 'clean ocean' and one of the most abundant fishing grounds in China (Chen et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2019).

|

Fig. 1 The cooling water entry ditch of nuclear power plant (Top left); The cooling water entry filter (Top right); The Phaeocystis globosa colony (Bottom left); The Phaeocystis globosa non-flagellate cells (Bottom right). Photos: Junxiang Lai |

Under normal circumstances, seawater could be described as a Newtonian fluid, in which its viscosity is mainly affected by temperature and salinity (Miyake et al., 1948). On the other hand, seawater may become a non- Newtonian fluid (Jenkinson et al., 1986) when it is under the influence of organic exopolymeric substances, including mucilage, which is derived mostly from phytoplankton (Jenkinson et al., 1995, 2015; Seuront et al., 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010). The presence of tiny particles and polymers in the marine environment can make seawater a more viscous and elastic medium. Wide biologically induced modifications of seawater viscosity during Phaeocystis bloom were observed in the Mediterranean in 1986 and 1987 (Jenkinson et al., 1993), German Bight and North Sea in 1988 (Jenkinson et al., 1995), eastern English Channel in 2002, 2003 and 2004 (Kesaulya et al., 2008; Seuront et al., 2006, 2007 2008), and East Antarctica (30-80˚E) in 2006 (Seuront et al., 2010).

At present, red tide monitoring mainly depends on the in situ measurements of chemical and biological properties of water samples from a research vessel, and/or remote sensing from aircraft and satellites (Anderson et al., 2001, 2017; Stumpf et al., 2003; Gohin et al., 2008). However, there exist some limitations of the above methods in the monitoring of P. globosa bloom. Moreover, the temporal and spatial changes of algal blooms can not be reflected in real-time due to the fact that sample handling and analytical processes will take at least 2-3 d. Additionally, the flagellated cells of P. globosa are very difficult to recognize due to their characteristic small sizes (3-8 μm) under the light microscope, and various fixatives (such as Lugol's Solution, aldehydes, or saline ethanol) that are used for preservation may damage the cells, rendering their enumeration imprecise (Houliez et al., 2011). Although the distribution of red tide organisms could be monitored through remote sensing over larger spatial scale, the high-cost, cloud cover and the need for high-resolution imagery obviates the use of remote sensing for localized P. globosa bloom studies (Anderson et al., 2001, 2012).

Since the 1990s, the automatic monitoring technology of marine water quality has developed rapidly, and the technology for HABs monitoring using the ocean buoys has gradually emerged (Cullen et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2006; Shibata et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2005). Although automatic water quality monitoring from a buoy can reflect real-time water quality variation in the monitoring area, some experts have shown that the automatic water quality monitoring buoy is not suitable for the monitoring of the P. globosa bloom (Li et al., 2015). Comparing the monitoring data of Guinardia flaccida bloom in February 2012 with P. globosa bloom in February 2014 obtained by automatic monitoring buoy in the Beibu Gulf in Guangxi, Li (2015) found that an automatic monitoring buoy could play a good role in the monitoring of red tide of a high Chl-a containing phytoplankton, such as diatom. However, the use of automatic monitoring buoys in the monitoring of pico-phytoplankton bloom, mixed and heterotrophic nutrition species, such as P. globosa bloom in the Beibu Gulf is scarce and should be studied.

Microalgal blooms are known to clog the entrance of the cooling water filtration system of many industrial plants (e. g., by spring diatom blooms in coastal and fresh waters), and have caused the closure of up to 18 desalination plants in the Arabian Gulf (by dinoflagellate blooms of Cochlodinium) (Richlen et al., 2010; Berktay et al., 2011; Villacorte et al., 2015a; Villacorte et al., 2015b; Anderson et al., 2017). This study shows that the haptophyte flagellate P. globosa is causing problems at the entrance of a cooling water filtration system of a nuclear plant in China. The daily cooling water consumption of the FCGNPP is 10.37 million m3 (Equivalent to 120 m3 s-1 water inflow), which is a large amount of seawater through the cooling water filter. An outbreak of P. globosa bloom will block the filter, thus threatening the safe operation of the FCGNPP. From this perspective, there is a clear demand for methods that can simplify the dynamic monitoring of P. globosa bloom adjacent to the FCGNPP. The aim of this work was to explore the effects of abiotic factors (temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen), and biological factors (Chl-a, phytoplankton community, P. globosa colony and transparent exopolymer particles) on the seawater viscosity, and to test the possibility of using seawater viscosity to monitor the P. globosa bloom.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Study Area and SamplingQinzhou Bay is located in the south of Guangxi province, China, and situated at the northern Beibu Gulf. The climate of the region is an example of a subtropical marine monsoon climate. The average annual water temperature and rainfall is 22.4℃ and about 2100 mm, respectively (Meng et al., 2016). Its water area is 380 km2 (Gu et al., 2015). Generally, the depth of the bay is between 2 m and 18 m, and the maximum water depth is 29 m (Huang et al., 2019). The Bay is dominated by diurnal tide, with an average tidal range of 2.5 m and a maximum tidal range of 5.5 m (Meng et al., 2016). The FCGNPP is located in the coastal zone of the northwest edge of the Qinzhou Bay basin.

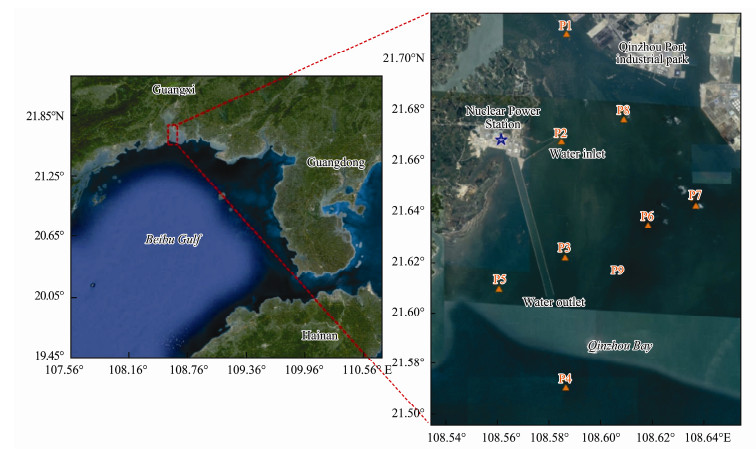

As shown in Fig. 2, the blue star represents the location of the FCGNPP. Qinzhou Port is oppositely located to the FCGNPP, and is the nearest bonded port between China and the Asean countries. Sampling sites are shown in Fig. 2 (orange triangles). Site P1 is located upstream of the FCGNPP, representing the environmental condition of the inner Qinzhou Bay. Site P2 is located near the water inlet of the FCGNPP, which represents the environmental condition unaffected by the FCGNPP. Sites P3 and P5 are located on either side of the water outlet of the FCGNPP, representing the influence of heated water on the environment. Site P4 is located downstream of the FCGNPP and represents the environmental condition outside of Qinzhou Bay. Sites P6, P7, and P8 are located near the Qinzhou Port, representing the environmental condition of the Qinzhou Port. At each site, both surface (about 0.5 m depth) and near-bottom (about 1 m above the sediment) water samples were collected with a 5 L plexiglass water sampler. The CTD (conductivity, temperature, pressure (depth) sensors, RBRconcerto, Canada) was used to measure water temperature, salinity and DO during the sampling campaign. Sampling was conducted during the high tide, before (25 October 2017, 11 November 2017, and 28 November 2017), during (28 December 2017 and 15 January 2018) and after (1 February 2018) the P. globosa bloom adjacent to the FCGNPP, respectively.

|

Fig. 2 Study area (red dashed box) and location of the sampling sites (orange triangles) adjacent to the Fangchenggang Nuclear Power Plant (blue star) in Qinzhou Bay, northern Beibu Gulf, China |

Chl-a concentrations were measured from 500 mL sea water sample following Suzuki (1990). Samples were filtered through 0.45 μm Whatman GF/F glass fiber filters. Chl-a was extracted by direct immersion of the filters in 5 mL of N, N-dimethylformamide at 5℃ in the dark for 24 h, and the extractions were analyzed with fluorescence spectrophotometer (F-4500, Hitachi Co., Japan) with excitation wavelength at 450 nm and emission wavelength at 685 nm after centrifugation, and the concentrations were calculated using equations proposed by (Standardization Administration, 2007).

2.3 Phytoplankton Community AnalysisThe collected algal samples were preserved with Lugol's solution. Phytoplankton enumeration was carried out with an inverted biological microscope (Olympus CKX53, Japan). Phytoplankton net samples were also taken and used to assist identification. Phytoplankton Shannon-Weiner diversity index (H'e) (Shannon-Wiener, 1949), Simpson's species evenness index (D) (Gleason, 1922), Pielou's species evenness index (Jsw) (Pielou, 1966), and Margalef species richness index (DMG) were calculated using the respective formulae.

2.4 Seawater Viscosity MeasurementAfter the ship arrived at the designated site, the surface sea water (below 0.5 m of the water surface) and the bottom sea water (over 1 m of the seafloor) were collected with a 5 L plexiglass water collector, and then 1 L of sea water was stored in a polyethylene bottle to avoid light and temperature. Seawater viscosity was measured immediately using ViscoLab4000 viscometer (Cambridge Applied Systems Inc., Boston) in the laboratory following the procedure detailed in Seuront Laurent (2006). Before determining each sample, the temperature control system equipped with the viscometer was used to control the sample measurement temperature to the in situ temperature (the temperature value derived from the CTD instrument). First, a 5 mL seawater sample placed in the sampling bottle in the dark was taken with a pipette; the impurities and zooplankton were removed by filteration through 200 μm filter, and then the visible P. globosa colonies were removed with a pipette under a dissecting microscope (100 × magnification, Olympus SZX7, Japan). Secondly, a 3 mL treated sample was injected into the measuring chamber with a pipette to measure the viscosity. There is a low mass stainless steel piston in the viscometer-measuring chamber. After the viscosity measurement begins, the piston moves back and forth in the chamber under the action of a magnetic field. The smaller the viscosity of the liquid measured, the shorter the time it takes for the piston to reach equilibrium in the liquid, and vice versa. Finally, the viscosity of the measured liquid can be known according to the readings on the viscometer screen. Each sample was measured three times, and then the average value was taken. Between each sample measurement, the viscometer chamber was carefully rinsed with deionized water in order to avoid any potential dilution of the next sample.

Because the viscosity is mainly affected by temperature, salinity, and phytoplankton cell secretions, the measured viscosity,

| $ \eta_{m}=\eta_{T, S}+\eta_{B i o}. $ | (1) |

The

| $ \eta_{B i o}=\eta_{m}-\eta_{T, S}. $ | (2) |

The relative excess viscosity,

| $ \eta=\left(\eta_{m}-\eta_{T, S}\right) / \eta_{T, S}. $ | (3) |

The concentrations of TEP in the seawater sample was determined by Alcian blue staining spectrophotometry following the method of Passow (1995). Briefly, a 500 mL water sample was filtered through a 0.4 μm polycarbonate filter membrane to collect the particulate matter. During filtration, the negative pressure was maintained below 0.02 MPa to avoid the breakage of large particles and the penetration of small particles. After that, deionized water was used to rinse the particles three times, and 0.5 mL of 0.02% Alcian blue (8GX, Sigma-Aldrich) with a pH of 2.5 was added for staining for 2 min. The filter membrane containing the stained particles was washed with deionized water and transferred to a beaker. 6 mL 80% H2SO4 solution was added to the beaker and the particles were soaked for 2 h. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation; a small amount of the supernatant was taken and placed in a 1 mL colorimetric dish, and the absorbance of the solution was measured at wavelength of 787 nm with Ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Unico UV-4802, China). The TEP concentration was calculated through the standard curve. In the experiment, xanthan was used as the standard material to make the standard curve, and the TEP concentration was expressed as xanthan equivalent (Xeq), with the unit of μg L-1 (Xeq).

2.6 Statistical AnalysesThe Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) (Version 24.0; SPSS Inc., IBM) was used for data analyses. Multiple comparison procedure based on one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine which dates were significantly different from each other regarding the environmental parameters (temperature, salinity and DO) and seawater viscosity

The temporal and spatial variations of seawater viscosity and P. globosa have been studied in the waters adjacent to the Fangchenggang nuclear power plant. There were three phases of P. globosa bloom in the research area: the pre-bloom stage (B0) was between October 25 and November 28, the bloom stage (B1) was between November 29 and January 15, and the post-bloom stage (B2) was between January 16 and February 1. No vertical stratification phenomenon was found in the temperature, salinity and DO profiles, indicating a well-mixed water column over the course of the survey. The average surface temperature fluctuated from 24.59℃ on October 25 to 12.86℃ on February 1, exhibiting a clear monthly change (Table 1). In contrast, the average surface salinity did not exhibit any characteristic pattern but fluctuated from 27.18 on October 25 to 27.48 on February 1 (Table 1). DO was relatively lower in the early B0 stage with a value of 6.95 mg L-1, increased continuously in the B1 stage, reached 9.13 mg L-1 at the peak of the bloom on January 15, and at the same time decreased gradually in B2 stage (Table 1).

|

|

Table 1 Time course of seawater temperature (℃), salinity, DO (mg L-1), |

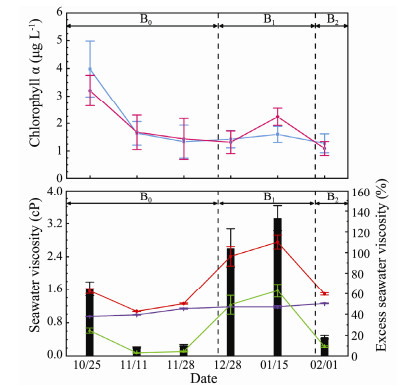

Overall, Chl-a in surface water exhibited a decreasing trend in the B0 stage, a slightly increasing trend in the B1 stage and a declined moderately in the B2 stage (Fig. 3). The first peak occurred on October 25, with an average value of 3.98 μg L-1 (caused by diatoms), while the second peak occurred on January 15, with average value 1.75 μg L-1 (caused by P. globosa). Chl-a in the surface and bottom water layer had a similar variation tendency but the concentration was distinctly lower in the bottom layer than the surface layer on October 25, and higher in the bottom layer on January 15. This indicates that diatoms, the dominant species in the B0 stage were mainly located in the surface layer, while P. globose, the dominant species during the B1 stage were mainly located in the bottom layer.

|

Fig. 3 Time course of Chl-a concentration (μg L-1) and seawater viscosity (cP). The light blue line represents the Chl-a in surface water, and the pink line represents the Chl-a in bottom water (the top graph); the red line represents the |

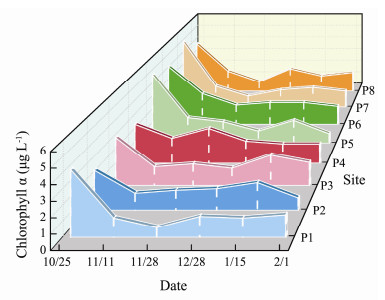

In terms of spatial distribution (Fig. 4), Chl-a concentration was relatively higher on October 25 than that in other dates and the high-value zones were located at sites P1, P5, P6, P7 and P8 with values ranging from 4.0 to 5.3 μg L-1. In the B1 stage, Chl-a increased slightly and reached a secondary high value on January 15 at site P3 with 3.1 μg L-1. In the B2 stage, Chl-a concentration decreased slightly with high-value zones located at sites P3 and P8, with an average value of 1.6 μg L-1.

|

Fig. 4 Spatial and temporal distribution of Chl-a concentration (μg L-1) in surface water in the study area |

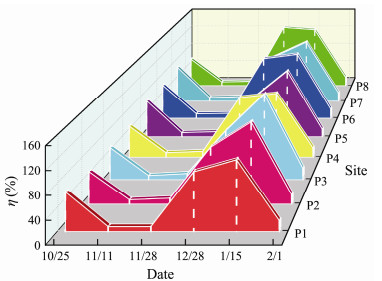

The temporal variation of seawater viscosity is shown in Fig. 3. The

The η was relatively high with an average of 64.67% and the high-value zones were at sites P5 (72.3%) and P7 (74.6%) (Fig. 5). This was due to diatom dominant species, such as skeletonema costatum, chaetoceros curvisetus and thalassionema nitzschioides existing in the waters (Fig. 6a). The η then exhibited a sharp decrease, with an average of 8.56% and lasted about one-month corresponding to the decrease in diatoms. Theη increased sharply during the B1 stage. The average peak occurred on January 15 with 133.13% during the P. globosa bloom stage, with high values at sites P5 (132.5%) and P6 (134.7%). Finally, the η decreased significantly to an average of 18.34% on February 1 that coincided with the P. globosa bloom fading away and returning of seawater to normal state.

|

Fig. 5 Spatial and temporal distribution of the η(%) in surface water in the study area |

|

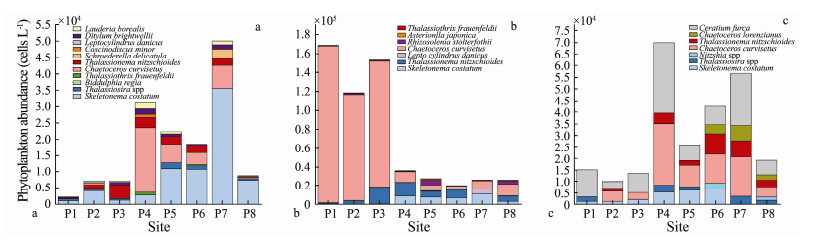

Fig. 6 Phytoplankton abundance (cells L-1) in surface water in the study area during (a) the B0 stage; (b) the B1 stage; and (c) the B2 stage |

In the B0 stage, the number of phytoplankton species was at the highest level (11 species), and the dominant species were skeletonema costatum and chaetoceros curvisetus. Skeletonema costatum was found at every site, and the maximum value (about 3.56×104 cells L-1) occurred at site P7. Chaetoceros curvisetus was found near the outer bay, and the maximum value (about1.99×104 cells L-1) occurred at site P4 (Fig. 6a). The highest values of species richness index, DMG, were at sites P2 (0.56) and P4 (0.58), respectively, and the lowest values were at sites P3 (0.45) and P8 (0.44), respectively. This indicated that the most abundant phytoplankton species existed at sites P2 and P4, while relatively lower phytoplankton species existed at sites P3 and P8. From the perspective of species evenness index, JSW and D, the values were relatively higher at sites P1 and P5, but were relatively lower at sites P7 and P8. This indicated that phytoplankton species at sites P1 and P5 were evenly distributed, while those at sites P7 and P8 were dominated by some species.

In the B1 stage, the number of phytoplankton species decreased to seven, but the amount of phytoplankton individuals increased significantly per site. The total phytoplankton individuals varied from 1.48×105 cells L-1 at the B0 stage to 2.54×105 cells L-1 at the B1 stage. Chaetoceros curvisetus, which replaced skeletonema costatum as the dominant species, was found at every site, especially at sites P1, P2, and P3, and with an average density of 1.5× 105 cells L-1 (Fig. 6b). The highest value (0.59) of DMG was at sites P5 and P8, and the lowest value (0.30) was at site P6. From the perspective of JSW, D and Shannon-Weiner diversity index,

In the B2 stage, the number of total phytoplankton species was seven, which was the same as that in the B1 stage, but the amount of phytoplankton individuals decreased significantly at each site. The most distinct characteristic was that ceratium furca (dinoflagellate) became the dominant species at the research area and occurred at every site, especially at sites P4 and P7, with the average density being 3.0×104 cells L-1. The highest value of DMG was 0.51 at site P8, while the lowest value was 0.21 at site P1 (Fig. 6c). From the perspective of JSW, D and

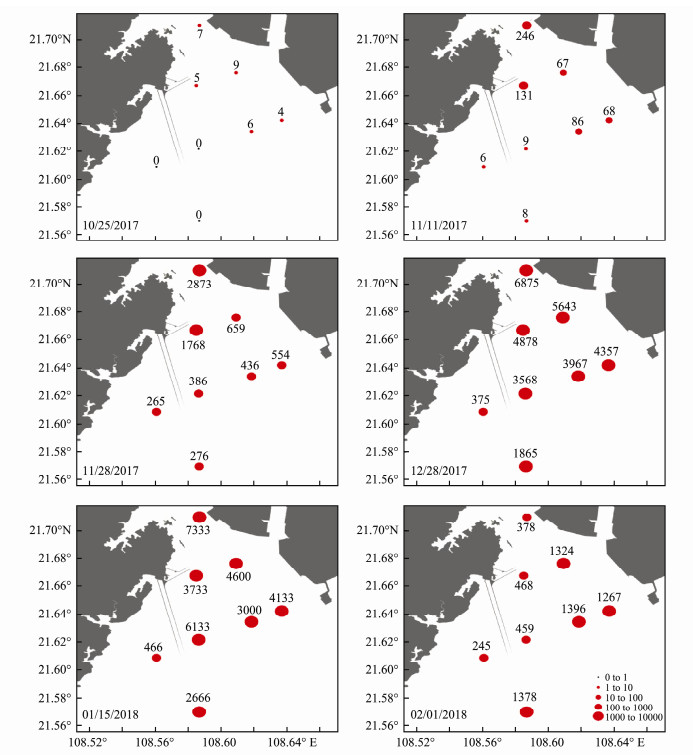

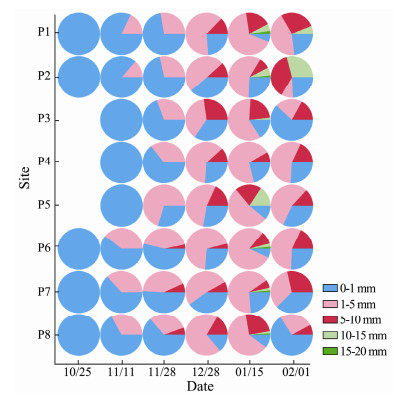

According to the spatial distribution variation of P. globosa colonies over time (Figs. 7, 8), there were sporadic colonies in Qinzhou Port on October 25, with an average of 6 colonies m-3, and the size of these colonies was 0-1 mm. No colonies were found in the outer sea area during this time, indicating that P. globosa originated in the eutrophic waters around the Qinzhou Port. On November 11, the number of colonies near the Qinzhou port continued to increase to hundreds, reaching 246 colonies m-3 at site P1, and the colonies' size was still dominated by 0-1 mm, with the colonies of 1-5mm being formed in the Qinzhou port. On November 28, the number of colonies near the Qinzhou port had reached thousands, and many colonies had gathered at the entrance area of the nuclear power plant, with about 1768 colonies m-3 at site P3. The colonies of 0~1mm at sites P1-P4 still had an absolute advantage over others. The size of colonies was mainly 1-5 mm at site P5, and 5-10 mm at sites P6, P7, and P8, which were nearer to the industrial park. During the P. globosa bloom period on December 28 and January 15, the number of colonies was maintained at thousands at the study area, with an average of 4000 colonies m-3. The colony size was mainly 1-5 mm, accounting for 60%; 5-10 mm accounted for 20%, 10-15 mm accounted for about 3%, and 15-20 mm only occurred at some sites. On February 1, during the decline period of P. globosa bloom, the number of colonies in the inlet and outlet area of the nuclear power plant was hundreds, with an average of 400 colonies m-3, and it was thousands in the outer sea, reaching about 1378 colonies m-3 at site P4, with the colonies size ranging from 0-1 mm and 1-5 mm.

|

Fig. 7 The horizontal distribution of P. globosa colony abundance (colonies m-3) in the adjacent waters of the FCGNPP |

|

Fig. 8 The relative proportions of P. globosa colonies with different diameters during the different bloom stages in the study area |

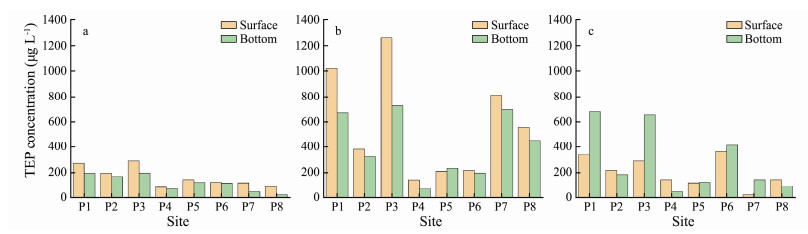

The mechanism behind Chl-a concentration and seawater viscosity variation is also consistent with the dynamics of TEP produced by P. globosa. In the B0 stage, TEP was relatively low, with an average of 165 μg L-1 in the surface layer and 118 μg L-1 in the bottom layer. TEP was significantly higher at sites P1, P2 and P3 than in other sites (Fig. 9a). In the B1 stage, TEP increased abruptly at all the investigated sites, with an average of 576 μg L-1 in the surface layer, 248% higher than that in the B0 stage, and 422 μg L-1 in the bottom layer, 256% higher than that in the B0 stage. Sites P1, P3, P7, and P8 were the high-value areas of TEP (Fig. 9b). In the B2 stage, the value of TEP was lower than that in the previous stage. The average TEP value was 206 μg L-1 in the surface layer and 293 μg L-1 in the bottom layer. The TEP value was significantly higher in the bottom layer than that in the surface layer at sites P1 and P3 (Fig. 9c).

|

Fig. 9 Variation of Transparent exopolymer particles (TEP) concentrations (μg L-1) in the study area during (a) the B0 stage; (b) the B1 stage; and (c) the B2 stage |

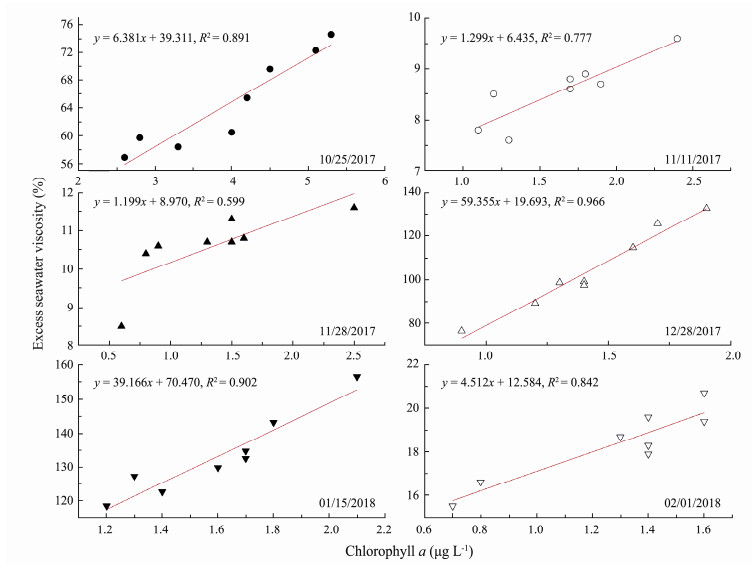

There was an extremely significant negative correlation between the

|

|

Table 2 Pearson correlation matrix for the seawater viscosity and physicochemical parameters in the study area |

|

Fig. 10 The relationship between excess seawater viscosity |

As liquid flows, particles move relative to each other and the liquid micelle is forced to deform, thus creating the internal stress that resists the deformation velocity, which is known as viscosity (Jenkinson at al., 2010, 2015). The existence of fine particles and polymers in the marine environment makes seawater become a mixture of 'hydrogel' and 'organic matter'. Seawater viscosity is composed of two parts, the

The

|

|

Table 3 Comparisons of the range of |

Accompanied by the global ocean warming (Chen et al., 2018), phytoplankton biomass (Anderson et al., 2012), marine mucilage, and large marine aggregates (Danovaro et al., 2009) are increasing in many coastal waters. The amount of mucilage has increased exponentially over the past 20 years, which is closely associated with the temperature anomalies (Danovaro et al., 2009). Ocean warming reduced

Jenkinson first measured a 400-fold increase in viscosity in the phytoplankton cultures (Jenkinson et al., 1986). Since then, more and more researchers have found that organisms can induce the modification of seawater viscosity, especially the ubiquitous oceanic phytoplankton (P. globosa) can significantly change the seawater viscosity (Jenkinson et al., 1995, 2014, 2015; Kesaulya et al., 2008; Seuront et al., 2007, 2008, 2010, 2016.).

P. globosa exists a complex polymorphic life cycle that alternates between solitary flagellated cells and gelatinous colonies (Rousseau et al., 1994). The morphological transformation of P. globosa from solitary cells into small colonies usually needs a solid substrate for attachment (Peperzak, 2000a; Riegman, 1996). A large number of Chaetoceros (Peperzak et al., 2000b) appeared during the pre-bloom period, and many newly-formed colonies were found on the setae of Chaetoceros, suggesting that Chaetoceros plays a key-role in Phaeocystis bloom inception (Rousseau et al., 1994). In the present research, before the appearance of P. globosa cells in the waters, seawater viscosity variation seemed to be dependent on other phytoplankton. Considering that the dominant diatoms, skeletonema costatum and chaetoceros curvisetus reached 3.6 × 104 and 2.0 × 104 cells L-1 respectively, seawater viscosity could thus be phytoplankton concentration dependent as previously suggested (Jenkinson et al., 1995). However, although the mucilage producer skeletonema costatum and chaetoceros curvisetus were often observed, the lower abundance compared to P. globosa suggested that their contribution to total mucus production was negligible.

Jenkinson (1995) measured viscosity and elasticity in seawater and found that viscosity was positively related to Chl-a levels. A positive correlation was reported between seawater viscosity and Chl-a concentration during Phaeocystis blooms in the German Bight and the North Sea (Seuront et al., 2006). More specifically, there were positive and negative correlations between Chl-a concentration and seawater viscosity before and after foam formation, respectively in the eastern English Channel (Seuront et al., 2006). This was because the mucopolysaccharide colonies of P. globosa affected the seawater viscosity, while the flagellated cells affected the Chl-a concentration, during the bloom decline; flagellated cells in the colony left their own mucus to swim in the zones relatively free of it, so there was a negative correlation between seawater viscosity and Chl-a.

The dynamics of seawater viscosity was also consistent with the TEP production. TEP mainly was exuded by phytoplankton, and derived from dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (Passow et al., 2002). During P. globosa bloom, TEP originated from two distinct sources: one from coagulation of DOC during the growing phase of P. globosa bloom, and the other from the mucilaginous matrix of P. globosa colonies released in the medium after disruption (Mari et al., 2005).

A positive correlation (Seuront et al., 2010) was also found between elevated seawater viscosity and bacteria abundance, which is consistent with the correlations between heterotrophic bacterial abundance and the amount of TEP in seawater (Corzo et al., 2005). As with phytoplankton, bacteria may modify the viscosity of seawater by producing polymeric materials. However, the relationship between bacteria and TEP is quite complex. TEP production or decomposition depends on environmental conditions (Grossart et al., 1999).

4.3 Application of Seawater Viscosity in P. globosa Bloom MonitoringThe coastal nuclear power plant needs to pump seawater into the cooling system to take away the excess energy released by the nuclear reactor, while the thick mucus layer of P. globosa blocks the water filter in the cooling system. This slows the heat removal process, which is very detrimental to the safe operation of the nuclear power plant. More importantly, the occurrence of P. globosa bloom increases the viscosity of seawater. The nuclear power plant pumps the seawater into the cooling system through a pipeline, and the pressure difference of the pumping pipe inlet increases when the seawater viscosity increases, and there is a risk of explosion of the cooling system due to the high pressure at any time. The following are the results of the calculation based on Poiseuille's law of fluid:

| $ Q=\frac{\pi R^{4}\left(p_{1}-p_{2}\right)}{8 \eta l} \Rightarrow \Delta p=\frac{8 Q \eta l}{\pi R^{4}}, $ | (4) |

where

| $ \Delta p=\frac{8 \times 120 \times 2.907 \times 10^{-3} \times 10^{4}}{3.14 \times 1}=8887.64 \mathrm{Pa}. $ | (5) |

According to the above calculation results, assuming that the P. globosa bloom intensity in the waters adjacent to the FCGNPP was similar to the eastern English Channel, the pipe pressure of the cooling water inlet system will increase exponentially. Therefore, accurate and timely prediction of P. globosa bloom is very important to the safe operation of the nuclear power plant.

Although Chl-a is a key index for monitoring red tide, it is not accurate in the P. globosa bloom monitoring. This is because P. globosa contains many major pigments, including Chl c3, Chl c1+2, fucoxanthin, 19'-hexanoyloxy- fucoxanthin (hex-fuco) and Chl-a, with minor carotenoids such as 19'-butanoyloxyfucoxanthin(but-fuco), diadinoxanthin, and diatoxanthin (Riegman et al., 1996; Lai et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2019). The ratios Chl c1+2/Chl-a (between 10.22 and 12.44% w/w), fucoxanthin/Chl-a (between 57.4 and 72.4% w/w), and hex-fuco/Chl-a are very high and showed an increase in the late exponential growth phase and stationary phase (Buma et al., 1991). Since the 1980s, hex-fuco has been reported as a proxy to estimate P.globosa abundance (Bjørnland et al., 1988; Zapata et al., 2004). Antajan (2004) found that but-fuco and hex-fuco were undetectable in the P. globosa strain isolated from field samples in 2001 in Belgian coastal waters. It was found that there was no significant correlation between hex-fuco concentration and P. globosa biomass in the water column by comparying pigments and phytoplankton from field samples. Furthermore, Chl-a concentration per cell varied during Phaeocystis bloom, which was 0.5 pg cell-1 during the first period of the bloom, then increased towards the summer with the maximum value of 1.4 pg cell-1, and finally declined to 0.8 pg cell-1 (Buma et al., 1991). The use of pigments as indicators for P. globosa bloom monitoring should be carefully applied. For example, if hex-fuco should be used as a distinctive criterion for the identification of Phaeocystis species, the effect of temperature and growth phase on the presence and proportion of this pigment must be well defined (Buma et al., 1991).

In the present research, the concentration of Chl-a was very high, but seawater viscosity was not high in the early stage of P. globosa bloom. The abundance of skeletonema costatum and chaetoceros curvisetus contributes to the increase in the correlation between Chl-a concentration and seawater viscosity. During the outbreak period of P. globosa, the concentration of Chl-a was not high, but the abundance of P. globosa was very high, and the corresponding seawater viscosity was also very high. There was a good corresponding relationship between P. globose and seawater viscosity, which provided a good basis for the prediction of P. globosa bloom.

Seawater viscosity can be used as a new reference index for P. globosa bloom monitoring. Strong supporting evidences (Jenkinson et al., 1993, 1995, 2015; Kesaulya et al., 2008; Seuront et al., 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010) including the following. 1) Under non-bloom conditions, seawater viscosity varies slightly with temperature. 2) Although other phytoplankton may change seawater viscosity, this could be ignored as compared with the effect of P. globosa on seawater viscosity. 3) During the P. globosa bloom, seawater viscosity correlated positively with the colony numbers, especially significantly correlated with the TEP excreted by P. globosa. To sum up, seawater viscosity has a certain advantage and potential value in the monitoring of P. globosa bloom. Due to the fragility of P. globosa colonies, during the sampling process, and/or during the viscosity measurement with the viscometer, these processes should be carefully operated in practical application to avoid breaking colonies and releasing additional mucus into solution, which may lead to a biased increase in seawater viscosity.

5 ConclusionsIn this study, the abiotic and biological factors affecting seawater viscosity were analyzed, and the deficiency of Chl-a (one of the traditional red tide monitoring indexes) and the feasibility and superiority of seawater viscosity in P. globosa bloom monitoring was discussed, which provides a new method and idea for the monitoring and early warning of P. globosa bloom. 1) Chl-a value could only be used to reflect the variation of total phytoplankton and not suitable for P. globosa bloom monitoring. 2) The changes of physical seawater viscosity have little effect on the changes of total seawater viscosity. 3) The increase in phytoplankton abundance, especially the outbreak of P. globosa and a large amount of mucus produced by the colonies can significantly increase seawater viscosity. 4) The biological seawater viscosity was completely consistent with the occurrence process of P. globosa bloom and could be used as a valuable index for P. globosa bloom monitoring. However, the visible colonies need to be removed in the process of measuring seawater viscosity to avoid the fragmentation of the colonies, and increase the measurement deviation of seawater viscosity.

AcknowledgementsWe are sincerely grateful to the undergraduates from the marine ecology laboratory for their help in the field sampling and Cole Rampy for checking the grammatical errors in the article. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41966007, 41706083, 41966002), the Science and Technology Major Project of Guangxi (No. AA1720 2020), the Science and Technology Plan Projects of Guangxi Province (No. 2017AB43024), the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (Nos. 2016GXNSFBA380108, 2017 GXNSFBA198135, 2018GXNSFDA281025, and 2018 GXNSFAA281295), the Guangxi 'Marine Ecological Environment' Academician Work Station Capacity Building (No. Gui Science AD17129046), the Distinguished Experts Programme of Guangxi Province, and the University's Scientific Research Project (No. 2014XJKY-01A, 2016PY-GJ07).

Anderson, D. M., Andersen, P., Bricelj, V. M., Cullen, J. J., and Rensel, J. J., 2001. Monitoring and management strategies for harmful algal blooms in coastal waters: APEC #201- MR-01.1, Asia Pacific Economic Program, Singapore, and Intergovernmental Oceanographie Commission Technical Series No.59, Paris.

(  0) 0) |

Anderson, D. M., Boerlage, S. F., and Dixon, M. B. E., 2017. Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) and Desalination: A Guide to Impacts, Monitoring, and Management: Paris, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO, 539 pp. (IOC Manuals and Guides No.78.)(English.) (IOC/2017/MG/78).

(  0) 0) |

Anderson, D. M., Cembella, A. D. and Hallegraeff, G. M., 2012. Progress in understanding harmful algal blooms: Paradigm shifts and new technologies for research, monitoring, and management. Annual review of marine science, 4: 143-176. DOI:10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081121 (  0) 0) |

Antajan, E., Chrétiennot-Dinet, M. J., Leblanc, C., Daro, M. H. and Lancelot, C., 2004. 19'-Hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin may not be the appropriate pigment to trace occurrence and fate of Phaeocystis: The case of P. globosa in Belgian coastal waters. Journal of Sea Research, 52(3): 165-177. (  0) 0) |

Berktay, A., 2011. Environmental approach and influence of red tide to desalination process in the Middle East region. International Journal of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 2(3): 183-188. (  0) 0) |

Bjørnland, T., Guillard, R. R. and Liaaen-Jensen, S., 1988. Phaeocystis sp. clone 677-3 - A tropical marine planktonic prymnesiophyte with fucoxanthin and 19o-acyloxyfuco-xanthins as chemosystematic carotenoid markers. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 16(5): 445-452. DOI:10.1016/0305-1978(88)90042-7 (  0) 0) |

Buma, A., Bano, N., Veldhuis, M. and Kraay, G., 1991. Comparison of the pigmentation of two strains of the prymnesiophyte Phaeocystis sp. Netherlands Journal of Sea Research, 27(2): 173-182. DOI:10.1016/0077-7579(91)90010-X (  0) 0) |

Chen, X. and Tung, K. K., 2018. Global surface warming enhanced by weak Atlantic overturning circulation. Nature, 559(7714): 387-392. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0320-y (  0) 0) |

Chen, Z. Z., Cai, W. G. and Xu, S. N., 2011. Risk assessment of coastal ecosystem in Beibu Gulf, Guangxi of South China. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 22(11): 2977-2986 (in Chinese). (  0) 0) |

Corzo, A., Rodríguez-Gálvez, S., Lubian, L., Sangrá, P., Martínez, A. and Morillo, J., 2005. Spatial distribution of transparent exopolymer particles in the Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Journal of Plankton Research, 27(7): 635-646. DOI:10.1093/plankt/fbi038 (  0) 0) |

Cullen, J. J., Ciotti, A. M., Davis, R. F. and Lewis, M. R., 1997. Optical detection and assessment of algal blooms. Limnology and Oceanography, 42(5part2): 1223-1239. DOI:10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1223 (  0) 0) |

Danovaro, R., Umani, S. F. and Pusceddu, A., 2009. Climate change and the potential spreading of marine mucilage and microbial pathogens in the Mediterranean Sea. PLoS One, 4(9): e7006. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0007006 (  0) 0) |

Gleason, H. A., 1922. On the relation between species and area. Ecology, 3(2): 158-162. (  0) 0) |

Gohin, F., Saulquin, B., Oger-Jeanneret, H., Lozac'h, L., Lampert, L., Lefebvre, A., Riou, P. and Bruchon, F., 2008. Towards a better assessment of the ecological status of coastal waters using satellite-derived chlorophyll-a concentrations. Remote Sensing of Environment, 112(8): 3329-3340. DOI:10.1016/j.rse.2008.02.014 (  0) 0) |

Gong, B., Wu, H., Ma, J., Luo, M., Li, X., Gong, B. and Wu, H., 2018. The algae community in taxon Haptophyceae at the early bloom stage of Phaeocystis globosa in Northern Beibu Gulf in winter. BioRxiv: 492454. (  0) 0) |

Grossart, H. P., 1999. Interactions between marine bacteria and axenic diatoms (Cylindrotheca fusiformis, Nitzschia laevis, and Thalassiosira weissflogii) incubated under various conditions in the lab. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 19(1): 1-11. (  0) 0) |

Gu, Y. G., Lin, Q., Yu, Z. L., Wang, X. N., Ke, C. L. and Ning, J. J., 2015. Speciation and risk of heavy metals in sediments and human health implications of heavy metals in edible nekton in Beibu Gulf, China: A case study of Qinzhou Bay. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 101(2): 852-859. (  0) 0) |

Houliez, E., Lizon, F., Thyssen, M., Artigas, L. F. and Schmitt, F. G., 2011. Spectral fluorometric characterization of Haptophyte dynamics using the FluoroProbe: An application in the eastern English Channel for monitoring Phaeocystis globosa. Journal of Plankton Research, 34(2): 136-151. (  0) 0) |

Huang, S. L., Peng, C., Chen, M., Wang, X., Jefferson, T. A., Xu, Y., Yu, X., Lao, Y., Li, J. and Huang, H., 2019. Habitat configuration for an obligate shallow-water delphinid: The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin, Sousa chinensis, in the Beibu Gulf (Gulf of Tonkin). Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 29(3): 472-485. DOI:10.1002/aqc.3000 (  0) 0) |

Jenkinson, I. R., 1986. Oceanographic implications of non- newtonian properties found in phytoplankton cultures. Nature, 323(6087): 435-437. DOI:10.1038/323435a0 (  0) 0) |

Jenkinson, I. R., 1993. Bulk-phase viscoelastic properties of seawater. Oceanologica Acta, 16(4): 317-334. (  0) 0) |

Jenkinson, I. R. and andBiddanda, B. A., 1995. Bulk-phase viscoe- lastic properties of seawater: Relationship with plankton components. Journal of Plankton Research, 17(12): 2251-2274. DOI:10.1093/plankt/17.12.2251 (  0) 0) |

Jenkinson, I. R. and Sun, J., 2010. Rheological properties of natural waters with regard to plankton thin layers. A short review.. Journal of Marine Systems, 83(3-4): 287-297. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2010.04.004 (  0) 0) |

Jenkinson, I. R. and Sun, J., 2014. Drag increase and drag reduction found in phytoplankton and bacterial cultures in laminar flow: Are cell surfaces and EPS producing rheological thickening and a Lotus-leaf Effect?. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 101: 216-230. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.05.028 (  0) 0) |

Jenkinson, I. R., Sun, X. X. and Seuront, L., 2015. Thalas-sorheology, organic matter and plankton: Towards a more viscous approach in plankton ecology. Journal of Plankton Research, 37(6): 1100-1109. (  0) 0) |

Kaiser, D., Unger, D., Qiu, G., Zhou, H. and Gan, H., 2013. Natural and human influences on nutrient transport through a small subtropical Chinese estuary. Science of the Total Environment, 450: 92-107. (  0) 0) |

Kesaulya, I., Leterme, S. C., Mitchell, J. G. and Seuront, L., 2008. The impact of turbulence and phytoplankton dynamics on foam formation, seawater viscosity and chlorophyll concentration in the eastern English Channel. Oceanologia, 50(2): 167-182. (  0) 0) |

Kim, B. C., Kim, Y. H. and Chang, S. M., 2004. Development of red-tide prediction technique using quartz crystal oscillator. Journal of Navigation and Port Research, 28(6): 573-578. DOI:10.5394/KINPR.2004.28.6.573 (  0) 0) |

Kim, G., Lee, Y. W., Joung, D. J., Kim, K. R. and Kim, K., 2006. Real-time monitoring of nutrient concentrations and red-tide outbreaks in the southern sea of Korea. Geophysical Research Letters, 33(13): L13607-L13610. DOI:10.1029/2005GL025431 (  0) 0) |

Lai, J., Jiang, F., Ke, K., Xu, M., Lei, F. and Chen, B., 2014. Nutrients distribution and trophic status assessment in the northern Beibu Gulf, China. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 32(5): 1128-1144. DOI:10.1007/s00343-014-3199-y (  0) 0) |

Li, B., Lan, W., Li, T. and Li, M., 2015. Variation of environmental factors during Phaeocystis globosa blooms and its implications for the bloom decay. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 34(5): 1351-1358 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Li, T., Lan, W., Lu, Y. and Xie, X., 2015. Application of automatic monitoring buoy in early warning for algal blooms in offshore area. Marine Forecasts, 32: 70-78 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Mari, X., Rassoulzadegan, F., Brussaard, C. P. D. and Wassmann, P., 2005. Dynamics of transparent exopolymeric particles (TEP) production by Phaeocystis globosa under N- or P-limitation: A controlling factor of the retention/export balance. Harmful Algae, 4(5): 895-914. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2004.12.014 (  0) 0) |

Meng, X., Xia, P., Li, Z. and Meng, D., 2016. Mangrove degradation and response to anthropogenic disturbance in the Maowei Sea (SW China) since 1926 AD: Mangrove-derived OM and pollen. Organic Geochemistry, 98: 166-175. DOI:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2016.06.001 (  0) 0) |

Miyake, Y., 1948. The measurement of the viscosity coefficient of sea water. Journal of Marine Research, 7: 63-66. (  0) 0) |

Passow, U., 2002. Transparent exopolymer particles (TEP) in aquatic environments. Progress in Oceanography, 55(3-4): 287-333. DOI:10.1016/S0079-6611(02)00138-6 (  0) 0) |

Passow, U. and andAlldredge, A., 1995. A dye-binding assay for the spectrophotometric measurement of transparent exopolymer particles (TEP). Limnology and Oceanography, 40(7): 1326-1335. DOI:10.4319/lo.1995.40.7.1326 (  0) 0) |

Peperzak, L., Colijn, F., Vrieling, E., Gieskes, W. and Peeters, J., 2000a. Observations of flagellates in colonies of Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesiophyceae): A hypothesis for their position in the life cycle. Journal of Plankton Research, 22(12): 2181-2203. DOI:10.1093/plankt/22.12.2181 (  0) 0) |

Peperzak, L., Gieskes, W., Duin, R. and Colijn, F., 2000b. The vitamin B requirement of Phaeocystis globosa (Prymnesio- phyceae). Journal of Plankton Research, 22(8): 1529-1537. DOI:10.1093/plankt/22.8.1529 (  0) 0) |

Pielou, E. C., 1966. Species-diversity and pattern-diversity in the study of ecological succession. Journal of theoretical biology, 10(2): 370-383. DOI:10.1016/0022-5193(66)90133-0 (  0) 0) |

Richlen, M. L., Morton, S. L., Jamali, E. A., Rajan, A. and Anderson, D. M., 2010. The catastrophic 2008-2009 red tide in the Arabian Gulf region, with observations on the identification and phylogeny of the fish-killing dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides. Harmful Algae, 9(2): 163-172. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2009.08.013 (  0) 0) |

Riegman, R. and Van Boekel W., 1996. The ecophysiology of Phaeocystis globosa: A review. Journal of Sea Research, 35(4): 235-242. DOI:10.1016/S1385-1101(96)90750-9 (  0) 0) |

Rousseau, V., Vaulot, D., Casotti, R., Cariou, V., Lenz, J., Gunkel, J. and Baumann, M., 1994. The life cycle of Phaeocystis (Prymnesiophycaea): Evidence and hypotheses. Journal of Marine Systems, 5(1): 23-39. DOI:10.1016/0924-7963(94)90014-0 (  0) 0) |

Seuront, L., Lacheze, C., Doubell, M. J., Seymour, J. R., Van Dongen-Vogels, V., Newton, K., Alderkamp, A. C. and Mitchell, J. G., 2007. The influence of Phaeocystis globosa on microscale spatial patterns of chlorophyll a and bulk-phase seawater viscosity. Biogeochemistry, 83(1-3): 173-188. DOI:10.1007/s10533-007-9097-z (  0) 0) |

Seuront, L., Leterme, S. C., Seymour, J. R., Mitchell, J. G., Ashcroft, D., Noble, W., Thomson, P. G., Davidson, A. T., van den Enden, R. and Scott, F. J., 2010. Role of microbial and phytoplanktonic communities in the control of seawater viscosity off East Antarctica (30-80˚E). Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 57(9-10): 877-886. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.09.018 (  0) 0) |

Seuront, L. and Vincent, D., 2008. Increased seawater viscosity, Phaeocystis globosa spring bloom and Temora longicornis feeding and swimming behaviours. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 363: 131-145. DOI:10.3354/meps07373 (  0) 0) |

Seuront, L., Vincent, D. and Mitchell, J. G., 2006. Biologically induced modification of seawater viscosity in the Eastern English Channel during a Phaeocystis globosa spring bloom. Journal of Marine Systems, 61(3-4): 118-133. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2005.04.010 (  0) 0) |

Shannon-Wiener, C., Weaver, W., and Weater, W., 1949. The mathematical theory of communication. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. EUA: University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

(  0) 0) |

Shibata, H., Miyake, H., Tokimune, H., Hamasaki, A., and Matsuyama, Y., 2015. A study of the Red-tide Monitoring System Using Drifting Buoy and Wireless Networks. Paper presented at the The Twenty-fifth International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference.

(  0) 0) |

Smith, K., Glancey, J., Thorson, G. and Huerta, S., 2005. Realtime surveillance of shallow depth estuaries for water quality and harmful algal bloom detection. Managing Watersheds for Human and Natural Impacts: Engineering, Ecological, and Economic Challenges: 1-12. (  0) 0) |

Standardization Administration P. R. China. 2007. Specifications for Oceanographic Survey Part 6: Marine Biological Survey GB/T 12763.6-2007. Standards Press of China, Beijing.

(  0) 0) |

Stumpf, R., Culver, M., Tester, P., Tomlinson, M., Kirkpatrick, G., Pederson, B., Truby, E., Ransibrahmanakul, V. and Soracco, M., 2003. Monitoring Karenia brevis blooms in the Gulf of Mexico using satellite ocean color imagery and other data. Harmful Algae, 2(2): 147-160. DOI:10.1016/S1568-9883(02)00083-5 (  0) 0) |

Suzuki, R. and Ishimaru, T., 1990. An improved method for the determination of phytoplankton chlorophyll using N, N-dimethylformamide. Journal of the Oceanographical Society of Japan, 46(4): 190-194. DOI:10.1007/BF02125580 (  0) 0) |

Verity, P. G. and Medlin, L. K., 2003. Observations on colony formation by the cosmopolitan phytoplankton genus Phaeocystis. Journal of Marine Systems, 43(3-4): 153-164. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2003.09.001 (  0) 0) |

Villacorte, L. O., Tabatabai, S., Dhakal, N., Amy, G., Schippers, J. C. and Kennedy, M. D., 2015a. Algal blooms: An emerging threat to seawater reverse osmosis desalination. Desalination and Water Treatment, 55(10): 2601-2611. DOI:10.1080/19443994.2014.940649 (  0) 0) |

Villacorte, L. O., Tabatabai, S. A. A., Anderson, D. M., Amy, G. L., Schippers, J. C. and Kennedy, M. D., 2015b. Seawater reverse osmosis desalination and (harmful) algal blooms. Desalination, 360: 61-80. DOI:10.1016/j.desal.2015.01.007 (  0) 0) |

Williams, G., Nicol, S., Aoki, S., Meijers, A., Bindoff, N., Iijima, Y., Marsland, S. and Klocker, A., 2010. Surface oceanography of BROKE-West, along the Antarctic margin of the south-west Indian Ocean (30-80˚E). Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 57(9-10): 738-757. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.04.020 (  0) 0) |

Wright, S. W., van den Enden, R. L., Pearce, I., Davidson, A. T., Scott, F. J. and Westwood, K. J., 2010. Phytoplankton community structure and stocks in the Southern Ocean (30-80˚E) determined by CHEMTAX analysis of HPLC pigment signatures. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 57(9-10): 758-778. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.06.015 (  0) 0) |

Xu, Y. X., Zhang, T. and Zhou, J., 2019. Historical occurrence of algal blooms in the northern Beibu Gulf of China and implications for future trends. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10: 451. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00451 (  0) 0) |

Yu, R. C., Lv, S. H., and Liang, Y. B., 2018. Harmful algal blooms in the coastal waters of China Global Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms, 309-316, Springer.

(  0) 0) |

Zapata, M., Jeffrey, S., Wright, S. W., Rodríguez, F., Garrido, J. L. and Clementson, L., 2004. Photosynthetic pigments in 37 species (65 strains) of Haptophyta: Implications for oceanography and chemotaxonomy. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 270: 83-102. DOI:10.3354/meps270083 (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19