2) Laboratory for Marine Geology, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266061, China;

3) Department of Ocean Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, China

The eastern continental shelf of China is one of the broadest continental shelves in the world. The west side of the shelf is Eurasia. A huge amount of water and sediment brought by large rivers such as the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers can link the land and the sea. Along the east side of the continental shelf is the Kuroshio Current, which is a strong west Pacific boundary current, with its sub-branches of the Taiwan Warm Current and the Yellow Sea Warm Current realizing the connection between the ocean and the continental shelf. The rivers and the currents help to form the grand source and sink sedimentary system in the Western Pacific Ocean. The annual sediment input of the Yellow River to the ocean reaches as much as 1.08×109 t (Wang et al., 2011), playing an important role in the system. At the same time, the Yellow River is a wandering river, its lower reaches having migrated frequently, with abundant sediment and less water. The latest major channel shift of the Yellow River took place in AD 1855, making the Yellow River Estuary shift from the Yellow Sea to the Bohai Sea (Xu and Ma, 2009; Xin et al., 2013). Since the Yellow River estuary moved to the Bohai Sea in 1855, a giant delta lobe with an area of 36272 km2 has developed on the west coast of the Bohai Sea, and the abandoned Yellow River Delta in the South Yellow Sea (SYS) has suffered continual erosion and thus has retreated (Milliman and Syvitski, 1992; Watersheds of the World, 2005; Wang et al., 2011). Previous researches on the Yellow River shift in 1855 have mainly focused on the abandoned delta in the north Jiangsu coastal area and the modern delta in the western Bohai coastal area, which directly resulted from the river shift (Saito et al., 2000; Xue et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2016). Recently, a few documents have reported on the possible influence of the river shift on the East China shelf. Evidences from grain size and element signals in core sediments indicate that the river shift could influence the provenance supplying the middle of the Bohai Sea and SYS (Zhao et al., 2014; Liao et al., 2015). Isotopic compositions of organic matters in core sediments show that the river shift could even affect the material supply in the East China Sea, which is far away from the Yellow River estuary (Yang et al., 2009). It seems the diversion of the Yellow River in 1855 not only influenced the sedimentation in the estuary, but also affected the material supply of the whole East China Shelf. Because of multiple clues included in the chemical signals and a lack of dating data for supporting in these documents, the influence of shift of the Yellow River in 1855 on the eastern China shelf seas remains ambiguous.

As the connection between the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea and as the channel for Yellow River materials entering the East China Sea (He et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2015; Duan et al., 2016), the north Yellow Sea (NYS) plays a unique role in the source-sink system. The NYS has developed a mud deposit zone and stable sedimentary environment since the high-stand sea level after the Last Glacial Maximum was achieved, which makes it a good area for paleoenvironment and paleoclimate reconstruction (Liu et al., 2004; Yang and Liu, 2007). Moreover, it is possible to record changes in the mass flux accurately from the Bohai Sea (Huang et al., 2014). Whether the Yellow River entered the Bohai Sea or not could profoundly affect the material exchange between the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea, hence the muddy area of the NYS has become a good object for studying the diversion of the Yellow River in 1855. On the other hand, foraminifera often have been used as a sensitive proxy in paleoclimate and paleoenvironment construction (Fiorini et al., 2010; Székely and Filipescu, 2016). For the East China shelf, foraminifera were used to reconstruct the history of the East Asian winter monsoon (EAWM) (Li et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014b; Lei et al., 2015; Du et al., 2016; Lei and Li, 2016), sea surface temperature (Tian et al., 2010), and paleoenvironmental changes (Xiang et al., 2008). These studies show that foraminiferal assemblages have a good response to East Asian monsoon fluctuation, but the diversion of the Yellow River, which caused sudden changes in sea water, sediment, and nutrient levels, was a stronger driving force than the monsoon fluctuation for the environmental change. In the other words, foraminifera should have a more pronounced response to the diversion of the Yellow River.

In this study, we used foraminifera and their assemblage in core H205 from the NYS to reveal the variation of sedimentary environment from before to after the diversion of the Yellow River in 1855 and to discuss the relationships among the foraminifera assemblage, Yellow River diversion, runoff fluctuations in the Yellow River and EAWM. This will provide a scientific basis for understanding the impact of the Yellow River on the deposition of the continental shelf and the source-to-sink process in the eastern China Seas.

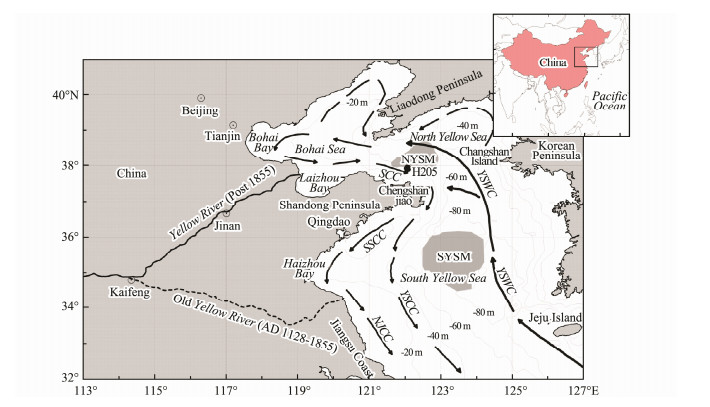

2 Study AreaThe Yellow River is the second largest river in China. It is famous for its small volume of runoff but abundant sediment loads, different sources for water and sediment, uneven space-time distribution, and so on. The Yellow River flows from west to east: originating from the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau; sequentially flowing through the Inner Mongolia Plateau, Loess Plateau, and North China Plain; and finally entering the Bohai Sea in the northern part of the Shandong Peninsula. The Yellow River drains a wide basin of 75244 km2, has a total length of 5464 km (Wang et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2014), and carries great loads of sediment into the ocean every year, accounting for about 5.5% of the suspended sediment flux to the oceans from the world's rivers, with an average annual runoff of 49 km3 (Milliman and Meade, 1983). However, with the impact of human activities in recent years, such as dams and agricultural irrigation in the upper reaches of the Yellow River, the runoff and sediment discharge entering to the Bohai Sea have greatly decreased. The Yellow River sediment flux has dropped, with an average of 0.29×109 t yr-1 since 1986 (Wu et al., 2015). The lower reaches of the Yellow River are very unstable, varying frequently. Historically, more than 20 large-scale diversions have taken place in the lower reaches of the Yellow River. In AD 1128, the Southern Song Dynasty fought against the Jin soldiers which came from north. In order to stop them, the government artificially broke the river bank of the lower reaches in Liguling. The Yellow River flowed through the northeast of Henan and Shandong Provinces, from Huai River to the Yellow Sea, and continued as such until 1855, which led to the formation of the old Yellow River Delta although abandoned now. In 1855, the Yellow River broke its banks in Tongwaxiang (near Kaifeng City), thus entering the Bohai Sea through Lijin from the south and forming the modern Yellow River Delta, which has continued growing to this day (Liu et al., 2009; Fig. 1).

|

Fig. 1 Map of the study area including bathymetry and water circulation patterns in the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea and collection site of core H205 (Modified after Liu et al., 2010). NYSM, North Yellow Sea Muddy area; SYSM, South Yellow Sea Muddy area; YSWC, Yellow Sea Warm Current; SCC, Shandong Coastal Current; SSCC, South Shandong Coastal Current; NJCC, North Jiangsu Coastal Current; YSCC, Yellow Sea Coastal Current. |

The Yellow Sea is located between the mainland of China and the Korean Peninsula and is a semi-closed shallow sea. It is divided into southern and northern sections, known as the SYS and the NYS, respectively, according to the boundary line from Chengshan Jiao at the eastern tip of the Shandong Peninsula to the Changshan Islands of the Korean Peninsula. The NYS is located east of the Bohai Sea and northeast of the Shandong Peninsula, with an average water depth of 38 m and a total surface area of 71000 km2. It is the link of the substance and energy exchange between the Bohai Sea and the SYS (Liu et al., 1998). The coast of the NYS mostly comprises bed-rock coast, and there are many bays along the coast of the Shandong Peninsula, forming a sandy coastline. The NYS is a shallow sea basin and extends along east-west direction. The topography is relatively flat, with gentle inclination from the north, west, and southwest to the middle and gentle inclination from the middle to the south. The water is deep in the middle of the NYS, and an argillaceous sedimentary area has developed (NYSM in Fig. 1). In this muddy area, sedimentation is continuous; the sedimentary environment is stable and the sediments are mainly composed of silty clay; and the grain size parameters fluctuate very little in the vertical direction. Studies have shown that this muddy area comprises multiple mud deposit zones, of which the Yellow River is the main source of materials (Liu et al., 2004; Li et al., 2014a).

The study area is dominated by tidal currents and has complicated hydrodynamic conditions. The Yellow Sea Warm Current (YSWC) and the coastal current system are present in this region. The basic flow is relatively stable, with a velocity that is high in winter but low in summer. The YSWC is a branch of the Tsushima Current that carries warm, salty water and flows into the Yellow Sea passing through the southeast of Jeju Island, roughly along the Yellow Sea trough, to the northwest at a slow rate of flow. On its way north, it is gradually weakened by topographical, hydrological, and meteorological conditions. A branch of the YSWC diverged at the east of Chengshan Jiao and converged with the South Korean Coast Current (SKCC) moving southward, and another branch of the YSWC converged with the Shandong Coastal Current (SCC) moving southward while the remainder of the YSWC turned west to the Bohai Sea through the Laotieshan Channel in the northern part of the strait. The Yellow Sea Coastal Current (YSCC) is a diluted current, whose direction does not change seasonally, that flows along the Shandong and Jiangsu coastlines. The YSCC begins from Bohai Bay, and then moves along the coast of the northern part of the Shandong Peninsula and through the southern Bohai Strait to Chengshan Jiao. Then, it mixes with the branch of the YSWC, turning southwest around the tip of the Shandong Peninsula. It branches into the South Shandong Coastal Current (SSCC), which eventually reaches the north Jiangsu coast. The YSWC has been enhanced by the diluted water and affected by the bottom topography of Haizhou Bay, and flows directed roughly along the 40–50 m isobath to the south. The YSWC flows to the north and the YSCC flows southward, together forming the cyclonic circulation patterns in the study area, which are considered to be the controlling factors in the formation of the muddy area of the NYS (Hu et al., 2012; Tana et al., 2017).

3 Materials and Methods 3.1 Sample CollectionThe main study object of this research is the sediment core H205, which was collected using a gravity sampler aboard the 'Dong Fang Hong 2' scientific research vessel in May 2009. The length of the core was 240 cm, and the water depth where the core was collected was 40 m. The sampling location was just outside the NYSM in southwest NYS (122.08˚E, 37.92˚N; Fig. 1). There was no apparent disturbance or missing for the process of core collection.

3.2 Analytical Methods 3.2.1 Grain sizeThe grain size composition was analyzed using a laser particle size analyzer. Before the grain size had been analyzed, the core was cut at 0.25 cm intervals firstly. Then 0.5–1 g of subsample was placed in a 100 mL beaker and pretreated with 5 mL 30% H2O2 for 24 h to remove any organic matter. Afterward, 3 mL of dispersant (0.5 mol L-1 sodium hexametaphosphate) was added and the mixture was treated with ultrasound for 30 minutes to ensure adequate dispersion. Grain size analyses were conducted using a Mastersizer 2000 laser particle size analyzer (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK) with the measurement range of 0.02–2000 μm and the resolution of 0.01 Φ. The measuring error was within 3%. Grain size parameters were calculated using the McManus moment formula (McManus, 1988).

3.2.2 Elemental analysisThe elemental concentrations were measured using an energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) spectro-meter (Liu and Fan, 2011). First, the core sediments were split at 0.5 cm intervals. Approximately 4 g of subsample was dried and grinded to below 200 mesh (63 μm), and then was put in a polyethylene ring with a diameter is 32 mm and compacted. At the bottom of the ring is a special transparent film. The bottom film and sample were confirmed to be smooth for testing on the machine. The elemental concentrations were measured using a desktop polarization EDXRF spectrometer (SPECTRO XEPOS, SPEC-TRO Analytical Instruments, Germany). In the course of this testing, a high pure nitrogen aeration rate of 90 L h-1 was maintained. Quality control was accomplished using National Standard (GBW 07314, offshore sediment) and duplicate samples. Testing was performed in replicates to ensure reliable results obtained. Relative standard deviations (RSDs) of the standards for most elements generally were within 2%.

3.2.3 Paleontological identification of foraminiferaThe core was cut at 5 cm intervals. Samples for foraminiferal analysis were oven-dried at 60℃, of which 20 g was placed in a 500 mL beaker and pretreated with 10% H2O2 to remove any organic matter and ensure adequate sample dispersion until the reaction ended. Then, the samples were washed over a 63 μm sieve in order to eliminate mud particles and then oven-dried at 60℃. The quantitative analysis and identification of foraminifera was carried out using an Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope via handpicking of aliquots of dry sediments obtained by splitting the residue into subsamples containing at least 200 specimens. The main references for the identification of genus and species were other studies in the regions near the current study area that provided descriptions of foraminifera found (e.g., Zheng, 1988).

3.2.4 Radionuclide analysisThe activities of radioactive isotope 210Pb in the sediment were measured using a high-purity germanium γ spectrometer (EG & G Ortec Ltd., USA). The details of the relevant analytical method are summarized as follows: first, 5–10 g of dried sample was sealed in a closed box for 15 days to reach radioactive balance, and once achieved. The sample was analyzed directly using the γ analytical method. The relative error was within 10% (Liu et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2014). The excess 210Pb activity was obtained by subtracting the 226Ra activity from the total 210Pb activity. The University of Liverpool, UK, provided a standard sample of 210Pb. The China Institute of Atomic Energy provided Standard samples of 226Ra. The experiment was performed at the Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

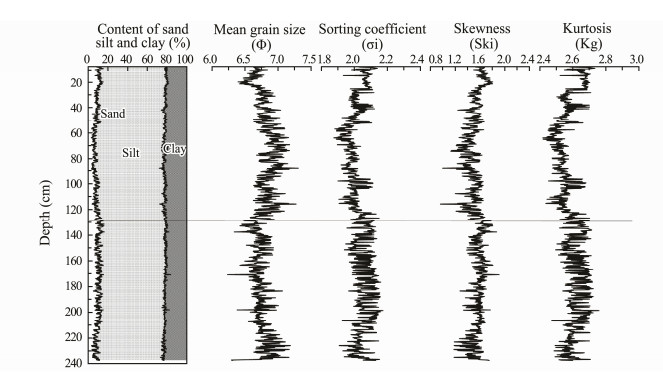

4 Results 4.1 Lithologic Characteristics and Ages 4.1.1 Grain size compositionsSediments in core H205 were composed of clayey silt, of which the range of sand content was between 3.52% and 16.62%, with an average value of 9.48%; the silt content ranged 62.97%–73.50%, with a mean value of 68.20%; and the clay content was between 16.39% and 27.94%, 22.32% on average. The grain size compositions were stable in the vertical direction, the changes were not evident. The average particle size of the core sediments was 6.23–7.31 Φ, and the mean value was 6.78 Φ. The mean grain size changed gently in the core. As the coarse-grained sediments had an increasing trend from 235 to 130 cm, the mean grain size decreased. The mean grain size increased sharply from 130 to 50 cm, because the coarse-grained sediments reduced and the content of silt increased obviously. Sand content increased from 50 cm to the top, so mean grain size decreased again. The sediment sorting coefficient (σi) was between 1.88 and 2.17, with a mean value of 2.03, indicating relatively poor sorting. The sorting coefficient had a little change along the core, and the variation trend was consistent with the mean grain size. From 235 to 130 cm, the values of sorting coefficient were relatively large. From 130 to 50 cm, the sorting coefficient was small and decrease upward, and it was the best sorting part in the core. And the sorting coefficient increased evidently from 50 cm to the top. The skewness (Ski) of the core sediments was in the range of 0.96–1.91, with a mean value of 1.54, indicating a positively skewed distribution. The sediment kurtosis (Kg) varied between 2.42–2.76, with an average of 2.59, meaning sharp kurtosis. Ski and Kg changed gently along the core, and the change trend is generally the same as that of the sorting coefficient (Fig. 2).

|

Fig. 2 Grain size composition and parameters in the sediment core H205. |

Grain size composition and parameters in core H205 changed a little, which reflects the relatively stable sedimentary environment and the weak hydrodynamic conditions in the study area. The core can be divided into the upper and the lower segments at 130 cm below sea floor, as there is a slight difference in the average grain size and grain size parameters between these two parts.

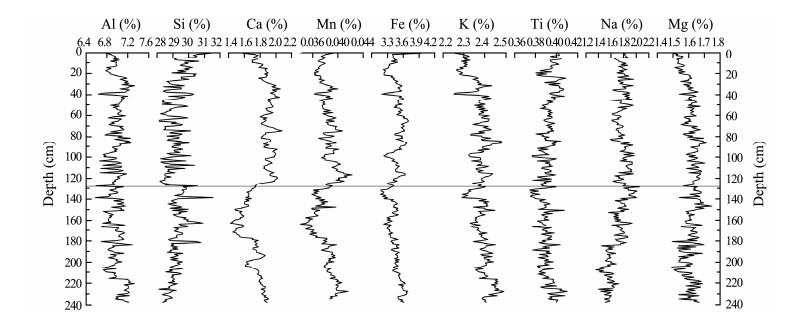

4.1.2 Geochemical elementsThe contents of major elements, such as Al, Si, Fe, Ca, Na, K, Mg, Mn, and Ti, in the sediments from core H205 are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3. The average contents of the two elements Al and Si were 6.99% and 29.2% respectively, indicating they are the main elements. The contents of these two elements were relatively stable in the core sediments, and changes in their contents were not apparent, which also illustrates that the core was located in a relatively stable sedimentary environment. Similarly, the contents of Fe, Na, K, Mg, and Ti displayed very little fluctuation throughout the core and were relatively stable. The two elements of Ca and Mn showed obvious changes in their contents at the depth of 128 cm, and the contents of these two elements are high in the sediments above the depth. The changes in these two elements may be related to the changes of sediment supply and the physicochemical state of the sedimentary environment, which will be discussed further in the next Section (5.1).

|

|

Table 1 Contents of major elements in the sediments from core H205 |

|

Fig. 3 Variation of major elemental compositions in core H205. |

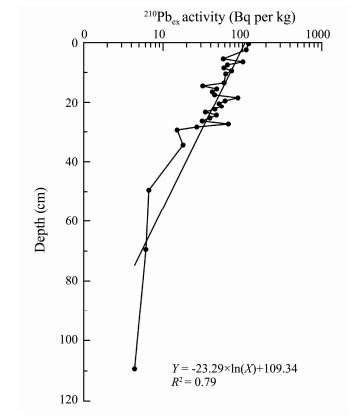

The activities of excess 210Pb in the sediments from core H205 are shown in Fig. 4. There was no obvious mixing layer in the upmost core. Excess 210Pb exponentially declined with depth from 0 to 70 cm. For 70–110 cm, the radioactivity of excess 210Pb was nearly constant, and corresponded to the secular equilibrium of the decay system. Through the linear fitting of excess 210Pb with depth, the average deposition rate was estimated to be 0.72 cm yr-1, with a correlation coefficient R2 of 0.79, which is inconsistent with the sedimentation rate in this area reported in other studies (Alexander et al., 1991; Tu et al., 2016).

|

Fig. 4 Excess 210Pb profiles and its linear fitting in the core. |

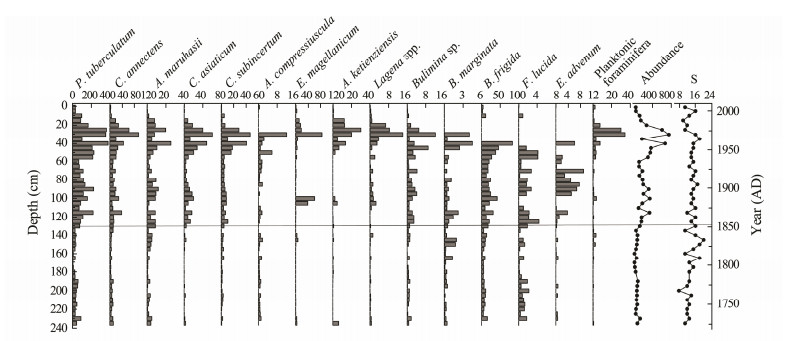

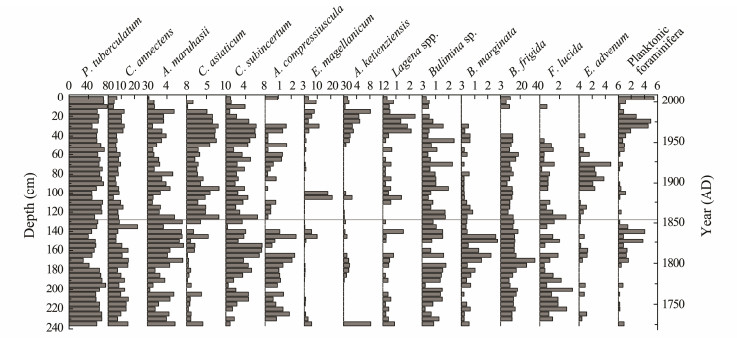

In total, 19326 foraminiferal shells were identified from 48 samples from core H205, with an average of 411 shells in each sample. After statistical analysis, we identified 39 benthic foraminiferal species belonging to 29 genera, indicating an enrichment of benthic foraminifera and the lack of planktonic foraminifera. The absolute abundance of foraminifera varied greatly in the range of 15–753 per gram, and the abundance tended to gradually increase from the bottom to the top (Fig. 5). The simple diversity (S, Species) did not change much overall, ranging between 8 and 20. Regarding the composition of the foraminiferal shells, most were hyaline shells, some agglutinated shells were also found, yet no porcelaneous shells were present in the core.

|

Fig. 5 Absolute abundance, total abundance (unit: N g-1), and species diversity (S) of the foraminifera in core H205. |

The benthic foraminifera in H205 were mainly neritic and offshore species. The dominant benthic foraminiferal species, i.e., comprising more than 1% of the group, appearing in the core were Protelphidium tuberculatum, Buccella frigida, Cavarotalia annectens, Elphidium magellanicum, Cribrononion subincertum, Cribrononion asiaticum, Ammonia maruhasii, Ammonia ketienziensis, and Bulimina sp. (Table 2). Their average absolute abundances ranged from several to tens per gram, with relative contents of 1%–59% (Fig. 6). Other benthic foraminifera, such as Ammonia compressiuscula, Elphidium advenum, Fissurina lucida, Lagenaspp., and Bulimina marginata, appeared only sporadically, with their absolute abundances not exceeding 12 per gram and an average relative abundance of less than 1%. In addition, Hanzawaia mantaensis, Nonionella atlantica, Astrononion tasmaniensis, Ammonia convexidorsa, Eggerella advena, Sigmomorphina undulosa, Bolivina robusta, etc. were found in samples from one or two core sections, with their combined relative contents less than 1%. Planktonic foraminifera were present in small amounts in the core, with a maximum of no more than 34 per gram in the samples from 20–40 cm section and more than 2% at 140 and 150 cm, in the lower part of the core.

|

|

Table 2 Foraminiferal abundance and the difference between the upper and lower segments in core H205 |

|

Fig. 6 Variation of relative abundance of foraminifera in the core (unit: %). |

In most samples, the dominant species in this core were neritic offshore water species, such as P. tuberculatum, E. magellanicum, and B. frigida. They (P. tuberculatum, E. magellanicum, and B. frigida) are all common species in the Bohai Sea, the Yellow Sea, and the East China Sea continental shelf and coastal area during the Quaternary Period and are typical representatives of low temperature and low salinity environments. Distribution of E. advenum and C. annectens was affected by sediment grain size and sensitive to the bottom environment, where fine-grained sedimentary environments dominate. C. subincertum appeared in the inner continental shelf near shore, in shallow water, in the intertidal zone, and in the estuary. Nevertheless, A. ketienziensis, A. compressiuscula, and B. marginata were living in relatively deep-water environments. A. ketienziensis mostly existed in the Yellow Sea and it was controlled by the cold water mass. A. compressiuscula was mainly distributed in the area where the water depth is greater than 20 m, especially 20–50 m, in the northwestern part of the SYS. B. marginata was a cold and narrow salt shelf, shallow-water specie that lived in the continental shelf at a water depth of more than 40 m. A. maruhasii reflects the warmer water (Hao, 1980; Wang, 1980).

The benthic foraminifera showed two characteristics in their vertical distribution: jump and fluctuation. The jump occurred at about 130 cm below the seafloor in the core, and the absolute abundance of most foraminifera above increased. The mean absolute abundance was 247 per gram. For P. tuberculatum, C. annectens, A. maruhasii, C. subincertum, and C. asiaticum the abundance increased more obviously, with average abundances of 148, 21, 7, 10, and 14 per gram, respectively. However, the mean abundance of foraminifera below the boundary of 130 cm was only 58 per gram, with absolute abundances for P. tuberculatum, C. annectens, A. maruhasii, C. subincertum, and C. asiaticum of 34, 6, 2, 2, and 1 per gram, respectively. The foraminiferal absolute abundance ratio between the upper and lower segments was up to 16 (Table 2). Excluding those with small abundances, the foraminifera had small amplitude fluctuations for individual species in the layers below 130 cm, but most of the benthic foraminifera have the abundances apparently fluctuated in the layers above 130 cm. For samples from the segment of 130–80 cm, foraminiferal abundance increased upward first and then decreased, but there was a lower value layer interbedded in the depth around 110 cm. The absolute abundance decreased obviously at the intervals of 80–60 cm. And from 60 to 20 cm, the abundance increased strikingly, reaching the maximum value in the entire core. Above 20 cm, the abundance continued to decrease upward, similar to the abundance below 130 cm. In contrast, there was no jump for F. lucida, which only showed irregular fluctuation throughout the core.

5 Discussion 5.1 Changes of Sedimentary Features Owing to the Yellow River Diversion and the Revised Core ChronologyThe reason that the element contents of Ca and Mn changed sharply at 128 cm, as mentioned in the previous Section (4.1.2), are suggested as follows. We speculated that the jump of Ca content was related to the change of source of sediments. Other studies have shown that sediments from the Yellow River are characteristically high in Ca, which is mainly enriched in silt and clay, and its content is significantly higher than that in sediments from the Yangtze River and other sources (Fan et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2010). For cases of no clear change in the depositional environment, a sudden increase of Ca content in the sediments should be related to an increase of the source materials from the Yellow River, which may result from the diversion of the Yellow River from the Yellow Sea to the Bohai Sea. Element Mn in sediment mainly exists in oxide form, and it enriches in the oxidizing environment (Qiao et al., 2007; Chun et al., 2010). The sudden increase of Mn at 128 cm reflects the oxidation environment of the seafloor and may be related to the enhancement of the coastal current. In addition, when the Yellow River was diverted to the Bohai Sea, the steady supply of fresh water strongly promoted the development of the coastal currents. For the elements Si, Fe, K, Ti, and Na, it was found that their contents also changed at 128 cm. Thus, it was concluded that the abrupt change at 128 cm suggested the change of the sediment source in the study area because of the Yellow River diversion. Based on these elemental changes, the interface was formed when the Yellow River shifted its route in 1855. Therefore, the average deposition rate in the core since 1855 can be estimated to be 0.83 cm yr-1, which is close to that calculated using excess 210Pb. As 210Pb can be adsorbed easily by fine particles and disturbed by bioturbation as well as mixing of the upper sediments (Fan et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2015), it is difficult to eliminate these interferences to get good age data. Therefore, we used the interface of elemental content jump to demarcate the age of the core.

5.2 Response of Foraminiferal Changes to the Yellow River DiversionAs mentioned above, the foraminiferal compositions showed abrupt change at 130 cm in core H205, and the abundance of most of the foraminifera increased sharply above that interface. Since the high sea level of the last glacial period, the sedimentary environment of the East China continental shelf has been in a stable period of development, with the stabilizing current system composed of the YSWC, SCC, and YSCC (Xu et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016). In the course of the same period, the East Asian monsoon fluctuated periodically, with interannual and interdecadal variations and increasing trends (Zhou et al., 2014; Li and Morrill, 2015). In the last 200 years, the fluctuation of the EAWM has been small, with the intensity varying from -2.53 to 2.08, i.e., there is no dramatic change. EAWM is not the cause of the change of foraminiferal compositions. It is speculated that there are other reasons for the jump of foraminiferal curve in core H205. According to the dating results, the abrupt foraminiferal change coincided with the Yellow River diversion in the year of 1855, suggesting that the jump of foraminiferal curve at 130 cm was caused by the diversion of the Yellow River.

When the Yellow River was diverted to the Bohai Sea, large quantities of water had been carried via the Yellow River. The river water entered the Bohai Sea, moved southward and mixed with the water mass in the middle of the NYS, and became a part of the circulation current system that consisted of the SCC and the remainder of the YSWC. Some of the water from the Yellow River flows along with the SCC, enters into the NYS and the SYS through the Bohai Strait. In comparison with the continental shelf seawater, the water in the Yellow River is rich in various nutrients, and the contents of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN), dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP), and dissolved silicon (DSi) were 304.7, 0.23, and 122.9 μmol L-1, respectively (Gong et al., 2014). The addition of this river water promotes an increase of offshore primary productivity, which is beneficial to the development of foraminifera, resulting in a significant increase of the abundance of most foraminifera. Additionally, owing to the addition of the Yellow River water, based on the analysis of mass conservation, the SCC is strengthened, and because the coastal current is mainly composed of cold water, it is more favorable for low temperature and offshore species of foraminifera. The absolute abundance of a great variety of foraminifera increased above 130 cm in core H205, but the assemblage of foraminifera did not change much, indicating that the area was still in the offshore shallow water environment as it was prior to 1855. Moreover, the increase in absolute abundance occurred because the river delivered a large amount of nutrients, which promoted the development of foraminifera. At the same time, the relative abundance of dominant species, such as P. tuberculatum, C. annectens, and B. frigida, did not vary much between the two segments divided by the 130 cm interface, showing that the area was still predominantly a cold shallow water environment. The relative abundance of A. maruhasii decreased above 130 cm in the core, indicating that the warm water mass in this area had been weakened after the diversion. The relative abundances of the two species C. asiaticum and C. subincertum regularly changed above 130 cm, indicating that the species living in the inland coastal shelf, inshore, intertidal and estuarine areas were more adapted to the environment after the diversion.

It should be noted that the absolute abundances of foraminifera in the sediments above 15 cm, which is roughly equivalent to the deposition after 1990, were very low and less than any other section above 130 cm in the core H205, which may be due to the strong influence of human activities. Since the year of 1990, the amount of water inflow and sediment discharge from the Yellow River has been sharply reduced. Especially in the 1990s, the Yellow River dried up, with the longest break more than 200 days (Wang et al., 2007). The effect of the Yellow River drying up is almost same as that the Yellow River diversion, which further proves that the input of the Yellow River has an important influence on the development of foraminifera in this area.

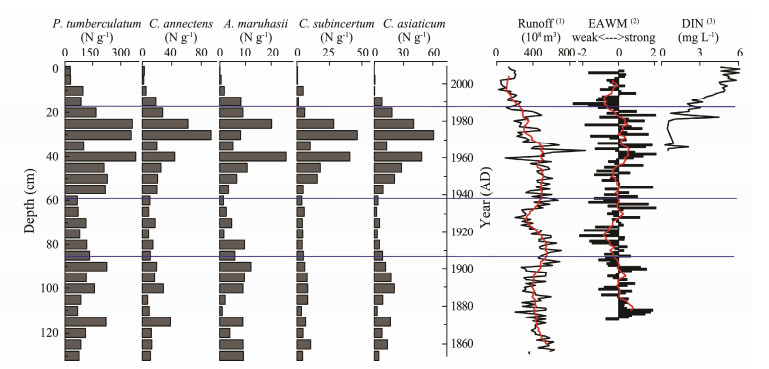

5.3 Succession of Foraminiferal Assemblages and Response to Flow Changes of the Yellow River and EAWM Since 1855Investigation of the changes in foraminiferal abundance since 1855 showed that several foraminiferal species had similar distribution patterns (Fig. 7), and the change corresponded well with the change of runoff volume into the sea from the Yellow River. When the runoff reaching the sea increased, the abundance of foraminifera was high and vice versa. According to this correspondence, the foraminiferal evolution in the core can be divided into the following four stages.

|

Fig. 7 Variations of absolute abundances of the five common foraminiferal species since 1855 with corresponding physical data. (1) Runoff of Yellow (Huanghe) River (Shi and Zhang, 2005); (2) East Asian winter monsoon (EAWM) (Gang et al., 2011; Qiao et al., 2011); (3) Variations of dissolved inorganic nitrogen concentration in the Yellow River (Li, 2010; Tao et al., 2010). Red lines are the running average curves. |

1855–1908: In this stage, the Yellow River was just diverted to the Bohai Sea, and the water of the Yellow River began to influence the area. The absolute abundance of foraminifera in the sediments from this segment was much higher than that below 130 cm, and C. asiaticum and C. subincertum, which represent nearshore shallow water species, had relatively high absolute abundances. The runoff of the Yellow River decreased in the middle of this period, and the abundances of foraminifera decreased too, with all reaching the low values at the depth around 110 cm.

1908–1938: This stage is the low discharge period for the Yellow River, with low absolute abundance and low relative abundance of the common foraminiferal species in the core. Species representing the low salt environments in the offshore shallow water zone, estuaries, and the intertidal zone, such as C. asiaticum and C. subincertum, were markedly reduced. A few foraminifera, such as E. advenum, a species sensitive to changes in grain size, increased during this period, which may be relevant to the variation of grain size of the bottom sediments.

1938–1988: This stage is the period with high runoff volume from the Yellow River, with an annual average flow flux of 418.86×108 m3. The maximum value appeared around the year of 1960. It is also the period when absolute abundance of foraminifera reached its maximum. At this stage, the absolute abundances of foraminifera were also the highest in the whole core, with an average abundance of 402 per gram. Excluding E. advenum, the absolute abundance of each foraminiferal species was high during this stage. The relative abundances of C. asiaticum and C. subincertum have ever increased by 1.9 and 2.7 times at the two stages of 1855–1908 and 1908–1938 respectively. However, such a high increase in the abundance coupled with the great increase of the Yellow River runoff did not occur as it did in this stage, which may be related to the influence of human activities in the Yellow River basin at this stage. The human activities were strongly influential in this area during this period, and the nutrients entering the Yellow River were significantly increased. The addition of high nutrient water effectively promoted the increase of the primary productivity in the estuary and offshore areas (Fig. 7), thus contributing to the development of benthic foraminifera.

1988–2009: Owing to the human influence such as dam construction and agricultural irrigation in the upstream of the Yellow River, the runoff entering the Bohai Sea decreased sharply during this period. Since 1990, the days that the Yellow River has been drying up are more and more every year, thus river runoff and sediment discharge are greatly reduced, which also greatly reduces the nutrients brought into the Yellow Sea via the Yellow River. Although the nutrients in the river have been increasing, it cannot promote the growth of foraminifera. The runoff of the Yellow River into the Bohai Sea has been limited to 144.46×108 m3 per year, about 1/3 of the volume during the previous stage. Accordingly, the absolute abundance of foraminifera decreased rapidly at this period and was even reduced to a level close to that before the Yellow River diversion, when only a small amount of a few individuals of foraminifera, such as P. tuberculatum, and planktonic shells were present.

The East Asian monsoon is an important control factor of the environment in coastal waters of China. Its strong and weak fluctuations directly affect the state of the offshore current system, especially the impact of the EAWM being more prominent (Saito, 2006; Tu et al., 2016). When the EAWM is strong, the coastal currents are strengthened, facilitating material transport from the Yellow River into the open sea; when the EAWM is weak, the coastal currents are simultaneously weakened, which is unfavorable to the transport of river water and substances into the sea (Liu et al., 2010; Li et al., 2014a). During the past century, the EAWM experienced four major decadal changes: 1884–1902 was a normal period; 1902–1924 was a weak monsoon period; 1928–1954 was another normal period; and 1958–1982 started as a strong monsoon period, but decreased in recent years (Ding et al., 2014). Comparing the abundance curves of five foraminiferal species (Fig. 7) with the monsoon strength curve, we can find that these curves show somewhat different distribution pattern except the good correspondence for the position of high value points. It can be seen that the high value point of foraminiferal abundance corresponds to the high value point of the EAWM (1960s), and at the same time coincides with the high value of runoff of the Yellow River. Combining the abrupt increase of foraminiferal abundance since the year 1855, it can be suggested that the EAWM could also promote the development of nearshore foraminiferal species by enhancing the coastal currents.

6 ConclusionsIn this study, it was shown that the absolute abundance of foraminiferal assemblages in core sediments from the NYS had good response to the diversion of the Yellow River in 1855. Before the diversion, the Yellow River flowed into the SYS, thus the river water hardly affected the NYS, and shallow water assemblages dominated the foraminifera with very low absolute abundance for all foraminiferal species. Since the diversion, the Yellow River has flowed into the Bohai Sea, carrying abundant nutrients and affecting the study area along with the coastal currents. Furthermore, the absolute abundance of most foraminiferal species increased sharply, with a maximum increase of 16 times. The coastal shallow water species are still dominant, but the microenvironment has changed slightly. Since the diversion of the Yellow River from the SYS to the Bohai Sea, accompanying with the fluctuation of runoff, the absolute abundance of foraminifera in the NYS has also changed with the same pattern. According to the core H205, the change of foraminiferal abundances can be divided into the following four stages: 1) In 1855– 1908, high values of foraminiferal abundances and river runoff appeared when the Yellow River was diverted to the Bohai Sea, with higher EAWM. 2) In 1908–1938, there were relative low foraminiferal abundances, matching the low Yellow River runoff and the EAWM intensity. 3) In 1938–1988, the absolute abundance of foraminifera reached its maximum value, and the runoff of the Yellow River was also larger. The extreme value of runoff and the extreme intensity of EAWM corresponded to the maximum abundance of foraminifera. 4) From 1988 to 2009, the runoff decreased rapidly, and the foraminiferal abundances also decreased rapidly, approaching a level close to that before the Yellow River was diverted from the SYS. Among these stages, the impact of human activities is superimposed on the third stage. Meanwhile, the EAWM could also promote the development of nearshore foraminifera in the NYS by enhancing the coastal currents.

The results suggest that the Yellow River diversion was an important geological event for the East China continental shelf and had significant impact on the marine ecological environment in this area.

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank the crew of the 'R/V Dong Fang Hong 2' for kindly assisting in sedimentary core sampling on the cruise in May, 2009. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 41530966) and Key Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2016YFA0600904).

Alexander, C. R., Demaster, D. J. and Nittrouer, C. A., 1991. Sediment accumulation in a modern epicontinental-shelf setting: The Yellow Sea. Marine Geology, 98(1): 51-72. (  0) 0) |

Chen, B., Zheng, Z., Huang, K., Zheng, Y., Zhang, G., Zhang, Q. and Huang, X., 2014. Radionuclide dating of recent sediment and the validation of pollen-environment reconstruction in a small watershed reservoir in southeastern China. Catena, 115(4): 29-38. (  0) 0) |

Chun, C. O. J., Delaney, M. L. and Zachos, J. C., 2010. Paleoredox changes across the Paleocene – Eocene thermal maximum, Walvis Ridge (ODP Sites 1262, 1263, and 1266): Evidence from Mn and U enrichment factors. Paleoceanography, 25(4): 389-413. (  0) 0) |

Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Liang, S., Ma, X., Zhang, Y., Si, D., Liang, P., Song, Y. and Zhang, J., 2014. Interdecadal variability of the East Asian winter monsoon and its possible links to global climate change. Journal of Meteorological Research, 28(5): 693-713. DOI:10.1007/s13351-014-4046-y (  0) 0) |

Du, S., Li, B., Chen, M., Xiang, R., Niu, D. and Si, Y., 2016. Paleotempestology evidence recorded by eolian deposition in the Bohai Sea coastal zone during the last interglacial period. Marine Geology, 379: 78-83. DOI:10.1016/j.margeo.2016.05.013 (  0) 0) |

Duan, L. Q., Song, J. M., Yuan, H. M., Li, X. G. and Li, N., 2016. Distribution, partitioning and sources of dissolved and particulate nitrogen and phosphorus in the North Yellow Sea. Estuarine Coastal & Shelf Science, 181: 182-195. (  0) 0) |

Fan, D., Yang, Z. and Guo, Z., 2000. Review of 210Pb dating in the continental shelf of China. Advance in Earth Sciences, 15(3): 297-302 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Fan, D., Yang, Z. and Wang, W., 2002. Composition and difference of carbonate in sediments of Yangtze River and the Yellow River. Progress in Natural Science, 12(1): 60-64 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Fiorini, F., Scott, D. B. and Wach, G. D., 2010. Characterization of paralic paleoenvironments using benthic foraminifera from lower Cretaceous deposits (Scotian shelf, Canada). Marine Micropaleontology, 76(1): 11-22. (  0) 0) |

Gang, Z., Wang, W. C., Sun, Z. S. and Li, Z. L., 2011. Atmospheric circulation cells associated with anomalous East Asian winter monsoon. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, 28(4): 913-926. DOI:10.1007/s00376-010-0100-6 (  0) 0) |

Hao, Y. C., 1980. Foraminifera. Science Press, Beijing, 1-224 (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

He, Y., Zhou, X., Liu, Y., Yang, W., Kong, D., Sun, L. and Liu, Z. H., 2014. Weakened Yellow Sea warm current over the last 2–3 centuries. Quaternary International, 349: 252-256. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.09.039 (  0) 0) |

Hu, B. Q., Yang, Z. S., Zhao, M. X., Yoshiki, S., Fan, D. J. and Wang, L. B., 2012. Grain size records reveal variability of the East Asian winter monsoon since the middle Holocene in the central Yellow Sea mud area, China. Science China Earth Sciences, 55(10): 1656-1668. DOI:10.1007/s11430-012-4447-7 (  0) 0) |

Huang, P., Li, T. G., Li, A. C., Yu, X. K. and Hu, N. J., 2014. Distribution, enrichment and sources of heavy metals in surface sediments of the North Yellow Sea. Continental Shelf Research, 73(2): 1-13. (  0) 0) |

Lei, Y. L., Li, T. G., Bi, H., Cui, W. L., Song, W. P., Li, J. Y. and Li, C. C., 2015. Responses of benthic foraminifera to the 2011 oil spill in the Bohai Sea, PR China. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 96(1-2): 245-260. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.05.020 (  0) 0) |

Lei, Y. L. and Li, T. G., 2016. Atlas of Benthic Foraminifera from China Seas. Science Press, Beijing, 1-378.

(  0) 0) |

Li, L. W., 2010. Effects of exchange fluxes of nutrients at the sediment and water interface and the Huanghe input on nutrient dynamics of the Bohai Sea. PhD thesis. Ocean University of China.

(  0) 0) |

Li, T. G., Nan, Q. Y., Jiang, B., Sun, R. T., Zhang, D. Y. and Li, Q., 2009. Formation and evolution of the modem warm current system in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea since the last deglaciation. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 27(2): 237-249. DOI:10.1007/s00343-009-9149-4 (  0) 0) |

Li, G., Li, P., Liu, Y., Qiao, L., Ma, Y., Xu, J. and Yang, Z., 2014a. Sedimentary system response to the global sea level change in the East China Seas since the last glacial maximum. Earth-Science Reviews, 139: 390-405. DOI:10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.09.007 (  0) 0) |

Li, G., Qiao, L., Dong, P., Ma, Y., Xu, J., Liu, S., Liu, Y., Li, J. C., Li, P., Ding, D., Wang, N., Dada, O. A. and Liu, L., 2016. Hydrodynamic condition and suspended sediment diffusion in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121: 6204-6222. DOI:10.1002/2015JC011442 (  0) 0) |

Li, Y. and Morrill, C., 2015. A Holocene East Asian winter monsoon record at the southern edge of the Gobi Desert and its comparison with a transient simulation. Climate Dynamics, 45(5-6): 1219-1234. DOI:10.1007/s00382-014-2372-5 (  0) 0) |

Li, Z. Y., Liu, D. S. and Long, H. Y., 2014b. Living and dead benthic foraminifera assemblages in the Bohai and northern Yellow Seas: Seasonal distributions and paleoenvironmental implications. Quaternary International, 349(12): 113-126. (  0) 0) |

Liao, Y. J., Fan, D. J., Liu, M., Wang, W. W., Zhao, Q. M. and Chen, B., 2015. Sedimentary records correspond to relocation of Huanghe River in Bohai Sea. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 45(2): 88-100 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Liu, F., Yang, Q., Chen, S., Luo, Z., Yuan, F. and Wang, R., 2014. Temporal and spatial variability of sediment flux into the sea from the three largest rivers in China. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 87(12): 102-115. (  0) 0) |

Liu, J. P., Milliman, J. D., Gao, S. and Cheng, P., 2004. Holocene development of the Yellow River's subaqueous delta, North Yellow Sea. Marine Geology, 209(1-4): 45-67. DOI:10.1016/j.margeo.2004.06.009 (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Saito, Y., Kong, X., Wang, H., Xiang, L., Wen, C. and Nakashima, R., 2010. Sedimentary record of environmental evolution off the Yangtze River Estuary, East China Sea, during the last 13, 000 years, with special reference to the influence of the Yellow River on the Yangtze River Delta during the last 600 years. Quaternary Science Reviews, 29(17): 2424-2438. (  0) 0) |

Liu, J., Saito, Y., Wang, H., Zhou, L. and Yang, Z., 2009. Stratigraphic development during the late Pleistocene and Holocene offshore of the Yellow River Delta, Bohai Sea. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 36(4-5): 318-331. DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2009.06.007 (  0) 0) |

Liu, M. and Fan, D. J., 2011. Geochemical records in the subaqueous Yangtze River Delta and their responses to human activities in the past 60 years. Chinese Science Bulletin, 56(6): 552-561. DOI:10.1007/s11434-010-4256-3 (  0) 0) |

Liu, Z. X., Xia, D. X., Berne, S., Wang, K. Y., Marsset, T., Tang, Y. X. and Bourillet, J. F., 1998. Tidal deposition systems of China's continental shelf, with special reference to eastern Bohai Sea. Marine Geology, 148(1-2): 225-253. (  0) 0) |

Liu, Z., Pan, S., Yin, Y., Ma, R., Gao, J., Xia, F. and Yang, X., 2013. Reconstruction of the historical deposition environment from 210Pb and 137Cs records at two tidal flats in China. Ecological Engineering, 61(5): 303-315. (  0) 0) |

Ma, C., Chen, J., Zhou, Y. and Wang, Z., 2010. Clay minerals in the major Chinese coastal estuaries and their provenance implications. Frontiers of Earth Science, 4(4): 449-456. DOI:10.1007/s11707-010-0130-5 (  0) 0) |

Mcmanus, J., 1988. Grain size determination and interpretation. In: Techniques in Sdimentology. Blackwell Science Pubilication, Oxford, 63-95.

(  0) 0) |

Milliman, J. D. and Meade, R. H., 1983. World-wide delivery of river sediment to the oceans. Journal of Geology, 91(1): 1-21. (  0) 0) |

Milliman, J. D. and Syvitski, J. P. M., 1992. Geomorphic/tectonic control of sediment discharge to the ocean: The importance of small mountainous rivers. Journal of Geology, 100(5): 525-544. DOI:10.1086/629606 (  0) 0) |

Qiao, S., Yang, Z., Liu, J., Sun, X., Xiang, R., Shi, X., Fan, D. and Saito, Y., 2011. Records of late-Holocene East Asian winter monsoon in the East China Sea: Key grain-size component of quartz versus bulk sediments. Quaternary International, 230(1-2): 106-114. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.01.020 (  0) 0) |

Qiao, S., Yang, Z., Pan, Y. and Guo, Z., 2007. Metals in suspended sediments from the Changjiang (Yangtze River) and Huanghe (Yellow River) to the sea, and their comparison. Estuarine Coastal & Shelf Science, 74(3): 539-548. (  0) 0) |

Saito, Y., 2006. East Asia winter monsoon changes inferred from environmentally sensitive grain-size component records during the last 2300 years in mud area southwest off Cheju Island, ECS. Science China Earth Sciences, 49(6): 604-614. DOI:10.1007/s11430-006-0604-1 (  0) 0) |

Saito, Y., Wei, H. L., Zhou, Y. Q., Nishimura, A., Sato, Y. and Yokota, S., 2000. Delta progradation and chenier formation in the Huanghe (Yellow River) Delta, China. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 18(4): 489-497. DOI:10.1016/S1367-9120(99)00080-2 (  0) 0) |

Shi, C. and Zhang, D. D., 2005. A sediment budget of the lower Yellow River, China, over the period from 1855 to 1968. Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 87(3): 461-471. DOI:10.1111/j.0435-3676.2005.00271.x (  0) 0) |

Székely, S.F. and Filipescu, S., 2016. Biostratigraphy and paleoenvironments of the late Oligocene in the north-western Transylvanian Basin revealed by the foraminifera assemblages. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 449: 484-509. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.02.043 (  0) 0) |

Ta, na, Fang, Y., Liu, B. C., Sun, S. W. and Wang, H., 2017. Dramatic weakening of the ear-shaped thermal front in the Yellow Sea during 1950s–1990s. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 36(5): 51-56. DOI:10.1007/s13131-016-0885-y (  0) 0) |

Tao, Y., Wei, M., Ongley, E., Li, Z. C., Chen, J. S. and Chen, Z. Y., 2010. Long-term variations and causal factors in nitrogen and phosphorus transport in the Yellow River, China. Estuarine Coastal & Shelf Science, 86(3): 345-351. (  0) 0) |

Tian, J., Huang, E. and Pak, D. K., 2010. East Asian winter monsoon variability over the last glacial cycle: Insights from a latitudinal sea-surface temperature gradient across the South China Sea. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 292(1): 319-324. (  0) 0) |

Tu, L., Zhou, X., Cheng, W., Liu, X., Yang, W. and Wang, Y., 2016. Holocene East Asian winter monsoon changes reconstructed by sensitive grain size of sediments from Chinese coastal seas: A review. Quaternary International, 440: 82-90. (  0) 0) |

Wang, P. X., 1980. Papers on Marine Micropaleontology. Ocean Press, Beijing, 1-204.

(  0) 0) |

Wang, H., Saito, Y., Zhang, Y., Bi, N., Sun, X. and Yang, Z., 2011. Recent changes of sediment flux to the western Pacific Ocean from major rivers in East and Southeast Asia. Earth-Science Reviews, 108(1): 80-100. (  0) 0) |

Wang, H., Yang, Z., Saito, Y., Liu, J. P., Sun, X. and Wang, Y., 2007. Stepwise decreases of the Huanghe (Yellow River) sediment load (1950–2005): Impacts of climate change and human activities. Global & Planetary Change, 57(3): 331-354. (  0) 0) |

Watersheds of the World, 2005. Data source: World Resources Institute. Available at http://earthtrends.wri.org/.

(  0) 0) |

Wu, X., Bi, N., Kanai, Y., Saito, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, Z., Fan, D. J. and Wang, H. J., 2015. Sedimentary records off the modern Huanghe (Yellow River) Delta and their response to deltaic river channel shifts over the last 200 years. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 108: 68-80. DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2015.04.028 (  0) 0) |

Xiang, R., Yang, Z., Saito, Y., Fan, D., Chen, M., Guo, Z. and Chen, H., 2008. Paleoenvironmental changes during the last 8400 years in the southern Yellow Sea: Benthic foraminiferal and stable isotopic evidence. Marine Micropaleontology, 67(1-2): 104-119. DOI:10.1016/j.marmicro.2007.11.002 (  0) 0) |

Xin, Z., Nan, J., Cheng, W., Wang, Y. and Sun, L., 2013. Relocation of the Yellow River Estuary in 1855 AD recorded in the sediment core from the northern Yellow Sea. Journal of Ocean University of China, 12(4): 624-628. DOI:10.1007/s11802-013-2199-4 (  0) 0) |

Xu, B., Bianchi, T. S., Allison, M. A., Dimova, N. T., Wang, H., Zhang, L., Diao, S., Jiang, X., Zhen, Y., Yao, P., Chen, H., Yao, Q., Dong, W., Sui, J. and Yu, Z., 2015. Using multi-radiotracer techniques to better understand sedimentary dynamics of reworked muds in the Changjiang River Estuary and inner shelf of East China Sea. Marine Geology, 370(2): 76-86. (  0) 0) |

Xu, J. X. and Ma, Y. X., 2009. Response of the hydrological regime of the Yellow River to the changing monsoon intensity and human activity. International Association of Scientific Hydrology Bulletin, 54(1): 90-100. DOI:10.1623/hysj.54.1.90 (  0) 0) |

Xu, Z., Lim, D., Choi, J., Li, T., Wan, S. and Rho, K., 2014. Sediment provenance and paleoenvironmental change in the Ulleung Basin of the East (Japan) Sea during the last 21 kyr. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 93: 146-157. DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2014.07.026 (  0) 0) |

Xue, C., Liu, J. and Kong, X., 2011. Channel shifting of lower Yellow River in 1128–1855 AD and its influence to the sedimentation in Bohai, Yellow and East China Seas. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 31(5): 25-36 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang, W., Chen, M., Li, G., Cao, J., Guo, Z., Ma, Q., Liu, J. and Yang, J., 2009. Relocation of the Yellow River as revealed by sedimentary isotopic and elemental signals in the East China Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 58(6): 923-927. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.03.019 (  0) 0) |

Yang, Z. S. and Liu, J. P., 2007. A unique Yellow River-derived distal subaqueous delta in the Yellow Sea. Marine Geology, 240(1-4): 169-176. DOI:10.1016/j.margeo.2007.02.008 (  0) 0) |

Yao, G., Yao, Q. and Yu, Z., 2014. Impact of the water-sediment regulation and a rainstorm on nutrient transport in the Huang-he River. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 32(1): 140-147. DOI:10.1007/s00343-014-3113-7 (  0) 0) |

Zeng, X., He, R., Xue, Z., Wang, H., Wang, Y., Yao, Z., Guan, W. and Warrillow, J., 2015. River-derived sediment suspension and transport in the Bohai, Yellow, and East China Seas: A preliminary modeling study. Continental Shelf Research, 111: 112-125. DOI:10.1016/j.csr.2015.08.015 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, L., Zhao, G. T., He, Y. Y., Xu, C. L., Qi, Q. and Long, X. J., 2014. Characteristics of heavey mineral in the B03 core on the north of the Yellow Sea and provenance implication. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 44(9): 72-81 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhao, X., Tao, S., Zhang, R., Zhang, H., Yang, Z. and Zhao, M., 2013. Biomarker records of phytoplankton productivity and community structure changes in the central Yellow Sea mud area during the mid-late Holocene. Journal of Ocean University of China, 12: 639-646. DOI:10.1007/s11802-013-2271-0 (  0) 0) |

Zheng, S. Y., 1988. Cementation and Ceramic Foraminifera in the East China Sea. Science Press, Beijing (in Chinese).

(  0) 0) |

Zhou, L., Liu, J., Saito, Y., Gao, M., Diao, S., Qiu, J. and Pei, S. F., 2016. Modern sediment characteristics and accumulation rates from the delta front to prodelta of the Yellow River (Huanghe). Geo-Marine Letters, 36(4): 247-258. DOI:10.1007/s00367-016-0442-x (  0) 0) |

Zhou, X., Yang, W., Xiang, R., Wang, Y. and Sun, L., 2014. Reexamining the potential of using sensitive grain size of coastal muddy sediments as proxy of winter monsoon strength. Quaternary International, 333(4): 173-178. (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18