2) Institute of Tropical Biodiversity and Sustainable Development, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Nerus 21030, Malaysia;

3) Pertubuhan Pelindung Alam Malaysia, Casa Green Cheras 43200, Malaysia;

4) Horseshoe Crab Research Group, Faculty of Science and Marine Environment, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Nerus 21030, Malaysia

Organisms living in coastal environments, which are exposed to environmental changes in day to night (24.0 h) and tidal (12.4 h) cycles, could adapt to complex environmental changes in comparison with terrestrial organisms (for reviews, see Palmer, 1976; Naylor, 2010). Although activity cycles of various terrestrial organisms have been investigated, information on organisms living in coastal environments is limited. In recent decades, physiological and biochemical experiments have been conducted to investigate the presence of biological clocks for intertidal arthropods (Naylor, 2010; Chabot and Watson, 2014). As a welldocumented model species, American horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus has been used to understand the horseshoe crab biology in a global view. In brief, horseshoe crabs (class Merostomata) comprise an ancient marine arthropod group that only evolved minutely in their external morphology since the Cretaceous period (Botton et al., 1996). The four surviving species are assigned to three genera and two families, in which L. polyphemus is the only extant species of family Limulidae. This arthropod lingers in the intertidal zone along the eastern coast of North America (Sekiguchi and Shuster Jr., 2009). Earlier, artificial light/dark (24.0 h) and tidal (12.4 h) cycles were experimentally tested on L. polyphemus (Chabot et al., 2004, 2007, 2008). Considering that locomotion activities synchronize with the amplitude of artificial tidal cycles, L. polyphemus could only react toward an endogenous tidal (12.4 h) clock. Based on these field observations, L. polyphemus possess a daily pattern of activity, which is being active either during the daytime or nighttime (Chabot et al., 2004, 2007). Later experiments have revealed that temperature and photoperiod trigger the locomotion activity of L. polyphemus (Chabot and Watson, 2010). By identifying two daily bouts in the L. polyphemus activity, researchers believe that locomotion is driven by two separates, where independent circatidal rhythms for each (circalunidian) clock are active for a period of 24.8 h (Chabot and Watson, 2010, 2014).

The variety of activity patterns expressed by each L. polyphemus population is due to genetic variations after being exposed to tidal conditions in different regions (Thomas et al., 2020). Thus, evolution and adaptation are responsible for the activity patterns (locomotion and reaction) of horseshoe crabs. The locomotion of L. polyphemus is studied using boxes and running wheels, whereas horseshoe crab is restrained in water tanks (normal depth is less than 0.5 m) in laboratory experiments (Chabot et al., 2004, 2007, 2008). However, the sea surface in natural environments does not have consistent heights because tidal heights depend on lunar cycles. In addition, the capacity of experimental devices could only accommodate small (male) horseshoe crabs. Thus, the spawning activity expressed by the females cannot be investigated in experimental conditions. In some field works, the activity of adult L. polyphemus was monitored by acoustic transmitters and fixed receivers in natural habitats. Adult horseshoe crabs have strong bimodal rhythms of activity. Therefore, the arthropod is significantly active during high tide (Watson and Chabot, 2010; Watson et al., 2016).

In comparison with L. polyphemus, the activity cycles of the other three Asiatic Merostomata (Tachypleus tridentatus, T. gigas, and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda) are poorly studied. The difference between Asiatic and American lineages may occur during the Jurassic period and result in at least 100 million years of behavioral isolation between the two groups of horseshoe crabs (Botton et al., 1996). Recently, the activity cycle of tri-spine horseshoe crab (T. tridentatus) has been investigated using animal-borne data loggers in natural conditions of the Seto Inland Sea (Watanabe et al., 2022). The use of animal-borne data loggers (a.k.a. biologging) to study the physiology and behavior of various species has increased over the past decades, thereby providing new insights into the behavior of these animals in their natural habitats (for reviews, see Cooke, 2008; Ropert-Coudert et al., 2009). In the Seto Inland Sea (West Japan), the activity cycle of T. tridentatus is affected by day to night and tidal cycles. These species are primarily nocturnal and more active during the nighttime tide rise. The activity of T. tridentatus occurs during daytime and nighttime during the spawning season in July and August (Watanabe et al., 2022).

Tachypleus tridentatus broadly ranges in distribution from North (34°N in Japan) to South (7°S in Indonesia) Asia (see the distribution map in the IUCN Red List, Laurie et al., 2019). Although the center of distribution is in the tropical region of Southeast Asia, the activity cycles of this species has not been reported in Sabah. Moreover, T. tridentatus in Kudat (north) and Kunak (east), which are isolated and less studied, have wide carapace measurements, whereas crabs from Semporna (southeast) are relatively smaller in size (Mohamad et al., 2021).

In this study, the activity cycles of T. tridentatus in the southeastern coast of Sabah (4°N), Malaysian Borneo were investigated from late September to early November in 2015. Then, the locomotion activity and surrounding environment of free-ranging adult T. tridentatus were recorded using biologging devices (acceleration and depth-temperature loggers). This study aimed i) to provide information for the activity cycles of T. tridentatus in Sabah, a tropical region; ii) to compare the results with that in western Japan, a temperate region; and iii) to present a preliminary understanding of the ecological importance and evolutionary significance of the activity cycles of T. tridentatus.

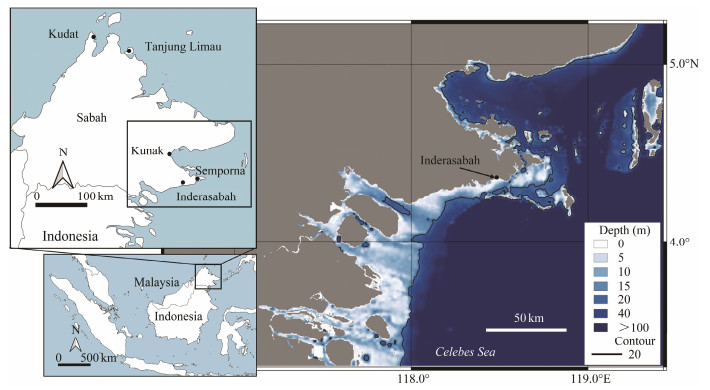

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Field SamplingThis study was conducted in a fishing village located in Inderasabah (4.30°N, 118.18°E), southeast Sabah (Malaysian Borneo), facing the Celebes Sea (Fig. 1). The bathymetric data used the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO 2021), and contour lines with 20 m depths were produced using QGIS ver. 3 (https://qgis.org). In the map, a shallow sandy and muddy bottom area (depth < 20 m) located around 5-15 km offshore from the coast falls within the vicinity of the village where approximately 3000 residents inhabit, and most of them are fishermen.

|

Fig. 1 Map showing the location of study site, Inderasabah in Southeast Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. The contour lines with 20-m depth are shown on the bathymetric chart of the Celebes Sea. |

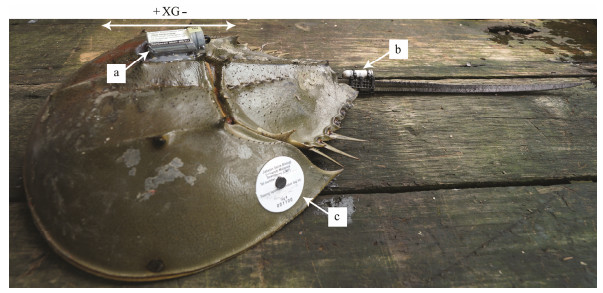

This study site was used to estimate the population size of T. tridentatus using a standard mark-recapture method (Manca et al., 2017). A total of 18 adult T. tridentatus (8 females and 10 males) were collected from September 16 to 18, 2015, and used for this study. Horseshoe crabs were captured using 4-inch gill nets deployed into the sea down to 5-10 m depth, approximately 1-3 km off-shore. Then, they were marked with a white button tag on the left side of the prosoma, which had a unique individual number and researcher's phone number (Fig. 2). The detailed information of sampling is described by Manca et al. (2017). With this method, 15 mark-recapture samples were collected between 2014 and 2015, from which 182 to 1095 sexually active adult T. tridentatus were retrieved from this water (Manca et al., 2017). Our study was conducted at the end of the survey, from which sexually mature horse-shoe crabs were presented in amplexus and sexed by observing the presence of rounded (males) or elongated (females) pincers in the first and second appendage.

|

Fig. 2 A female horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus with (a) an acceleration logger: HOBO Pendant G logger, (b) a depth-temperature logger: DST milli, and (c) a white button tag with the ID number and the researcher's phone number. |

Two types of biologging devices were used for this study (Fig. 2). An acceleration logger (HOBO Pendant G logger, 58 mm × 33 mm × 23 mm, 18 gram in air, Onset Corporation, Pocasset, MA) was used to record the locomotion activity of a horseshoe crab. The acceleration logger was set to record acceleration along the longitudinal axis at 1 min intervals, which had a memory capacity of 64000 data points (Watanabe et al., 2022). A depth-temperature logger (DST milli, 13 mm × 39 mm, 5 g in water, Star-Oddi Co., Reykjavik, Iceland) was used to record the surrounding environmental conditions. The depth-temperature logger had a memory capacity of 698800 depth and temperature data points with accuracies of 0.27 m and 0.1℃, respectively. The depthtemperature logger was set to record depths and temperature at 3 and 15 min intervals for 3 years. All devices were set to start recording at 0:00 on September 20, approximately 2-4 d after horseshoe crabs were released (Table 1).

|

|

Table 1 Summary of logger data recorded on free-ranging tri-spine horseshoe crabs in the southeastern coast of Sabah, Borneo |

Both types of data loggers were fixed on a meshed PVC sheet (4 cm × 6 cm) using two plastic cable ties and attached to horseshoe crabs using two-component epoxy glue. The acceleration loggers were attached on the dorsal carapace of eight female and 10 male T. tridentatus. Meanwhile, the depth-temperature loggers were attached on the telson of five female horseshoe crabs. After the glue was cured, all animals were released into the water at the captured point.

The tagged horseshoe crabs were recapture (as bycatch) passively through local fishing activities. We advertised the fishermen and other local people in Inderasabah to check the ID number on the white button tag and retrieve the data loggers. Then, compensation (postage fees) was provided upon receiving the loggers.

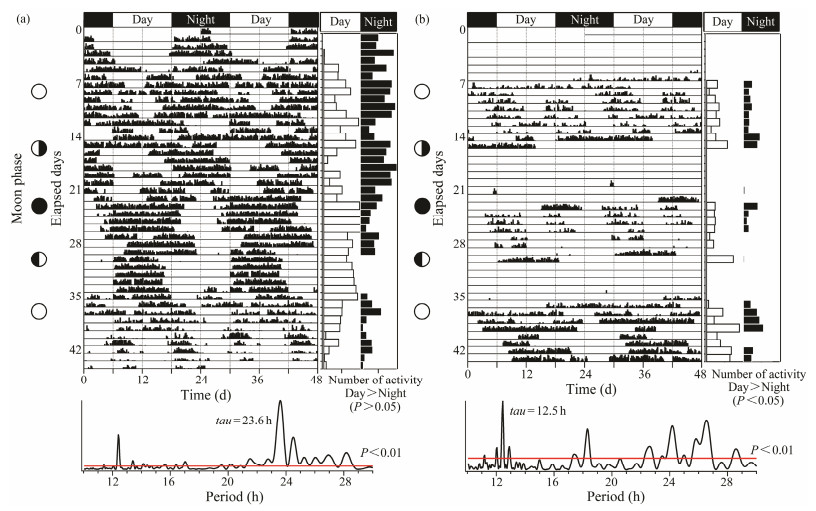

2.3 Data AnalysisData from retrieved loggers were read out by using HOBO ware Pro for Pendant G logger (Onset Corporation, Pocasset, MA) or SeaStar for DST milli (Star-Oddi Co., Reykjavik, Iceland), and saved in ASCII format for further processing. Data processing was performed using custombuild macro programs in IGOR Pro ver. 6.0 (Wave Metrics, Inc., Lake Oswego, OR). Based on the acceleration data, we determined whether the animal was 'active' or 'inactive' by the minute. Acceleration signals were reflected by accelerations related to changes in the movements of animals, that is, dynamic accelerations and gravitational acceleration, resulting from changes in body posture (Yoda et al., 2001). The resolution of the acceleration sensor was 0.025 g (0.245 m s-2), which was sufficient to determine whether an animal was active or inactive. This practice was adopted from Watanabe et al. (2022). Changes between consecutive data points and longitudinal acceleration (delta XG) were calculated. 0.1 G (0.98 m s-2) was used as an 'active' or 'inactive' criterion as the bimodal distribution with high values (> 0.1 G) corresponded to walking or digging on the seafloor. Active point numerals were summed into 10 min bins for the construction of double-plotted actograms that represented rhythmicity (activity patterns are described in Fig. 3).

|

Fig. 3 Examples of activity cycles with a peak in the 24.0-h (a: HC14) and in the 12.4-h (b: HC08) expressed by free-ranging adult horseshoe crabs Tachypleus tridentatus in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Upper left panel: actograms double-plotted, black/white bars at the top indicate daytime (06:00-18:00) and nighttime (18:00-06:00). Upper right panel: cumulated number of activity points during each of daytime and nighttime. Lower panel: Lomb-Scargle periodogram analyses of the actogram; vertical scale is relative power. Largest peak value above horizontal line of significance (P < 0.01) indicated by numerical value (tau). |

Double-plotted actograms and Lomb-Scargle periodograms (Lomb, 1976) were created for each animal to examine their individual activity cycles as described in Chabot et al. (2008). The maximum value of primary periodicity components (tau, P < 0.01) was determined by using a periodogram with tau nearly equal to 24.0 h (Fig. 3a) or 12.4 h (Fig. 3b). We calculated a cumulative number of active points from each daytime (06:00-18:00) and nighttime (18:00-6:00) period to determine whether each horseshoe crab exhibited a diurnal or nocturnal activity. The proportion of active points during nighttime (nocturnal activity rate) was also calculated for each horseshoe crab as an index for the degree of nocturnality (Watanabe et al., 2022).

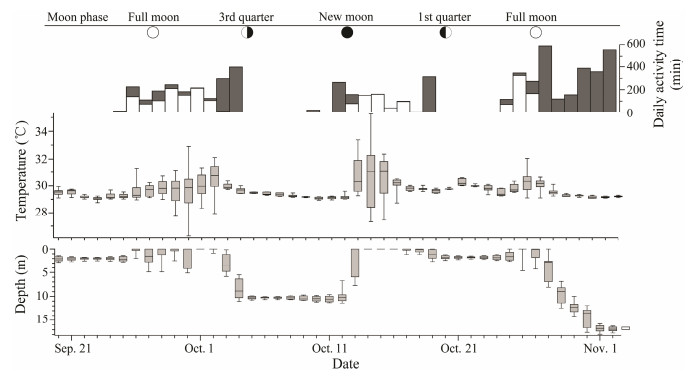

Based on the depth and temperature data, boxplots with 10, 25, 50, 75, and 90 percentiles were created in each daily bin and then compared with the daily total activity times. The daily total activity time in shallow water (< 0.3 m, the accuracy of depth sensor) was estimated for the spawning activity of T. tridentatus. This approach promoted T. tridentatus arrival into the water edge (shore) or otherwise, where it remained in slightly deeper waters within the intertidal zone. In addition, daytime and nighttime water depth (average values) and active points (0 means inactive; > 0 means active) in each hourly bin were compared. Then, Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Zar, 2010) was used to determine the statistical significance (P < 0.05) among the average values because all data were non-parametric.

3 ResultsFor 10-49 days after horseshoe crabs were released, five male T. tridentatus with acceleration loggers and one female with acceleration and depth-temperature loggers were recaptured as bycatch through local fishing activities in Inderasabah (recapture rate: 33.3%, Table 1). The loggers were active for 7-45 days, from which an overall 194 activity days were achieved for the six horseshoe crabs (Table 1). Periodogram analyses indicated four individuals with significant activity peaks in the 24.0 h range (23.0-24.0 h, e.g., Fig. 3a) and two individuals with peaks in the 12.4 h range (Fig. 3b, Table 1). Nocturnal activity rates that range from 0.364 to 0.775 only indicated two T. tridentatus (HC 06 and 08) with different daytime and nighttime activities (Table 1). Nocturnal activity rates of 0.364 and 0.467 (P < 0.05) indicated that two horseshoe crabs exhibited daytime locomotion. However, based on the actogram, all six T. tridentatus were active during the daytime and nighttime.

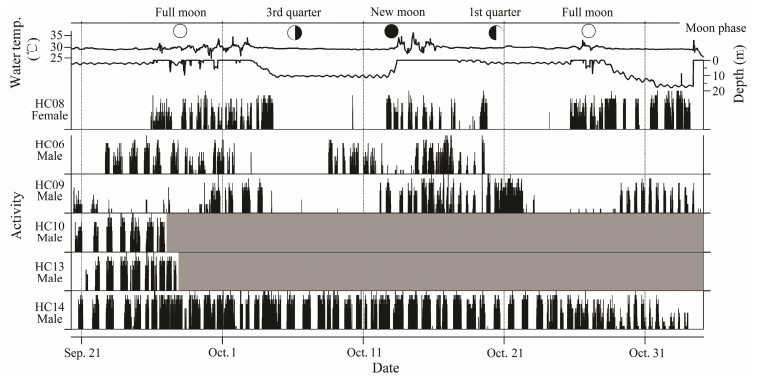

Four horseshoe crabs (HC06, 08, 09, and 14) with activity records for more than 40 days revealed that one male (HC14) was active daily, whereas the other crabs were dormant around the first and third quarter moon (Fig. 4). Meanwhile, the active and dormant periods of female (HC08) crabs were consistent with the moon phases (Fig. 5). For female T. tridentatus, the marked movement was witnessed at least 1-2 days before the new moon or full moon, and its locomotion continued to the next first or third quarter moon. However, episodes of dormancy were observed during the active periods, which began from the first and third quarter moon and continued for more than 5 days.

|

Fig. 4 Temporal changes of data recorded by biologging devices on free-ranging adult horseshoe crabs Tachypleus tridentatus in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo in September to November 2015. Water depth and temperature data was recorded on the female (HC08). |

|

Fig. 5 Daily changes of activity, water temperature and depth, recorded on an adult female horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus (HC08). |

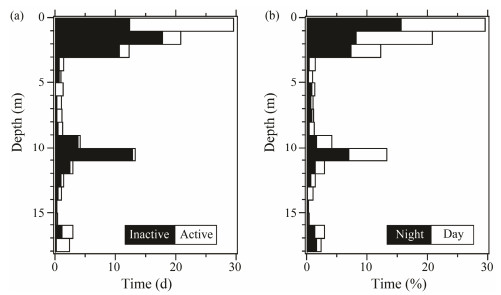

During the new and full moon, the female spent all the active periods in deeper water for at least 1-2 days before the first and third quarter moon (October 3 to 4 and October 18, respectively) and for 6 days after the second full moon (October 28 to November 2, Fig. 5). The female moved in the range of 0-18 m depth with bimodal peaks at 0-3 m and 9-12 m, respectively (Fig. 6). During the active periods, the female moved in a wide range of depth from shallow to deep water (depth 0-18 m, Fig. 5). The female was inactive when approaching deeper water (Z = 94313, P < 0.001) either during the daytime or the nighttime (Z = 139574, P = 0.7372; Fig. 6).

|

Fig. 6 Comparisons of histograms of water depth between active and inactive time (a) and between daytime and nighttime (b) recorded on an adult female horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus (HC08). |

In this study, 6 to 18 (recapture rate: 33%) tagged horseshoe crabs were recaptured within 49 days after being released. In 15 mark-recapture samplings of T. tridentatus in Inderasabah, four were recaptured as bycatch (recapture rate: 1.5%, Manca et al., 2017). Low recapture rates by mark-recapture samplings were also reported on T. gigas populations in the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia (6%, Mohamad et al., 2015) and on L. polyphemus populations in the American coasts with negligible tides (7%, Swan, 2005) and within a semi-closed bay (11%, James-Pirri, 2010). In the semi-closed bay, depth-temperature loggers were attached to 15 adult L. polyphemus, from which only one female (7% of tagged crabs) was recovered as a carcass on the beach (James-Pirri, 2010). Compared with these studies, the recapturing of tagged horseshoe crabs became more efficient with the use of local fisheries.

4.2 Daily Periodicity of ActivityIn this study, the majority (four of six, 67%) of T. tridentatus exhibited 24.0 h (circadian) cycles for their activity. This finding is similar to the discovery in western Japan, where the activity of this arthropod coincides with natural photoperiods and tidal cycles (Watanabe et al., 2022). In the laboratory, artificial light or dark and tidal cycles revealed that L. polyphemus exhibited 12.4 h activity cycles (Chabot et al., 2007). In addition, their activity was synchronized with rising tides during the light and dark periods. Therefore, after this experiment, L. polyphemus was associated with an endogenous circatidal (12.4 h) clock that triggered its locomotion activity (Chabot et al., 2008). Unlike L. polyphemus, T. tridentatus possessed an endogenous circadian (24.0 h) clock.

However, the daily activity patterns of T. tridentatus were different in Sabah (Borneo) and the Seto Inland Sea (Japan). In this study, of the six individuals, only two showed significant differences by being more active during the daytime. None of the recaptured T. tridentatus showed nocturnal activity. This activity pattern was similar to L. polyphemus. In the experimental study on L. polyphemus, only two of the eight individuals exhibited significantly more activities during the light period than during the dark period. On the contrary, the remaining six L. polyphemus were not significantly active under light or dark conditions (Chabot et al., 2008). More than half (57%) of T. tridentatus from western Japan exhibited nocturnal activity, whereas the others showed neither nocturnal nor diurnal activity (Watanabe et al., 2022).

Considering that L. polyphemus were fed on bivalves, polychaetes, crustaceans, and gastropods (Botton, 2009), we hypothesized that T. tridentatus also predated on benthic polychaetes in western Japan. Considering that T. tridentatus were mostly available during the nighttime, we could piece the prey searching using T. tridentatus nocturnal activity (Watanabe et al., 2022). In the present study, the female (HC08) spent all the active periods in deeper water after the spawning season, and the male (HC14) was active aside from the spawning ritual (Section 4.4). Thus, T. tridentatus in Inderasabah were primarily active for foraging during the non-spawning season. In addition to daytime catching and size classifications (Mohamad et al., 2016; Manca et al., 2017; Mohamad et al., 2021), the food habits of adult T. tridentatus have not been reported in the tropical region. Thus, the regional chronotype differences in T. tridentatus may suggest that feeding habits during evolution have made temperate and tropical populations unique.

4.3 Dormant and Active PeriodsIn this study, prolonged inactive (dormant) periods for more than 5 days were found, which indicated that the moon or lunar phases were responsible for the arthropod's locomotion into shallow water. T. tridentatus in western Japan behaves similarly under lunar periodicity. In the temperate environment of Japan, T. tridentatus was active during the spring tides after the new moon and full moon. This arthropod would become dormant for 2-3 days during the neap tides after the first and third quarter moon (Watanabe et al., 2022). However, for T. tridentatus in Sabah, their dormant periods were longer than those in western Japan (Fig. 4).

In Sabah, the spawning sites of T. tridentatus are found in Tanjung Limau, the northern part of Sabah facing the Sulu Sea (Fig. 1). The inaccessible knee-deep muddy terrain of Inderasabah might be the nests in this vicinity (Mohamad et al., 2016). In Tanjung Limau, the number of amplexus that relocate themselves into shallow water for their spawning activity will remain high for at least 2-3 days after the new moon or full moon days. This finding coincides with our data and indicates that female T. tridentatus will become active for at least several days prior to the spawning ritual.

On the contrary, the reduced activity of T. tridentatus may be related to the dormant periods. Low temperature is crucial for horseshoe crabs to conserve their energy before reproducing. For instance, we observed that the lowest temperature of the Seto Inland Sea is 18℃ from November to May as previous report (Nishii, 1975). However, the average temperature of tropical waters around Inderasabah is 29.7℃± 0.81℃ (mean ± SD, range 24.7-36.3℃). Given the contrasting exceed of the lower limit, the dormant behavior in T. tridentatus is unlikely triggered by temperature dips. Hence, for populations in Inderasabah, the upper limit of temperature tolerance of this species is unclear. Moreover, female T. tridentatus remained active when the logger recorded a temperature higher than 35℃ (Fig. 4). Thus, a water temperature of 29℃ indicates a completely submerged T. tridentatus. Considering that temperature spikes (above 30℃) only occur during the daytime of new and full moon periods (Fig. 4), T. tridentatus has reached water fringe and exposed the logger to the air. Given the depthtemperature logger on the female (HC08), its presence in shallow water (depth 0.1-0.3 m) during lunar days would indicate its role in the spawning ritual (Section 4.4).

Female T. tridentatus was constantly mobile in shallow water (depth < 1 m) during the daytime and nighttime and completely rested (inactive) in deeper water (depth > 9 m) during several semi-lunar days (Fig. 6). Based on water depth and temperature data, we found that HC08 avoided shallow areas (depth < 1 m) during dormancy because water temperatures were exceeding 30℃, particularly during the daytime tide fall. Thus, female T. tridentatus might opt to become dormant in deeper yet temperature-stable waters during the non-breeding periods for energy conservation.

4.4 Lunar Periodicity of ActivityIn general, T. tridentatus spawns in shallow waters (Sekiguchi, 1988; Laurie et al., 2019). It coincides with the movement of female T. tridentatus in such conditions (depth < 0.3 m) during the new moon and full moon periods. Considering that more T. tridentatus emerge into shallow waters as amplexus from April to October (Mohamad et al., 2016), November should be the late spawning season. In West Japan, the spawning activity of T. tridentatus is associated with diurnal and nocturnal high tides. The spawning activity of T. tridentatus peaks during lunar spring tides (Sekiguchi, 1988). Therefore, the female HC08, which was in shallow water during daytime and nighttime lunar tide rise, could exhibit 12.4 h (circatidal) activity cycles.

During a spawning ritual, the male would latch onto the opisthosoma of the female by using its first and second modified pincers. This act does not obstruct the movement of the female (Sekiguchi, 1988). In this study, we found that two male T. tridentatus had their activity synchronized with the new moon and full moon days. These males were latching (in amplexus) onto their respective suitors. Hence, the semi-lunar periodicity in their activity is conclusive for spawning. However, the activity of one male (HC14) did not follow the moon phases. With more activities (periodicity in locomotion), the distance proximity and short read lengths within the acceleration graphs during the first and third lunar quarter moon indicate that this outlier (HC14) is solitary or alone. Although this study is based on the limited information obtained from one female and five male T. tridentatus, we were able to develop a baseline for the behavioral ecology of T. tridentatus in southeast Sabah. In addition, later studies have good recapture efficiency, which indicates that the high percentage of biologging device retrieval would rectify the knowledge gaps concerning the life history of T. tridentatus outlined in this study.

AcknowledgementsThis study was funded by the Sabah Biodiversity Center, SaBC (No. TJ 66917). The authors thank the villagers/fishermen in Inderasabah, especially Mr. Jeffri and his family, for their help during the sampling period and particularly for the recoveries of biologging devices.

Botton, M. L., 2009. The ecological importance of horseshoe crabs in estuarine and coastal communities: A review and speculative summary. In: Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. Tanacredi, J., et al., eds., Springer, Heidelberg, 45-63.

(  0) 0) |

Botton M. L., Shuster Jr. C. N., Sekiguchi K., Sugita H.. 1996. Amplexus and mating behavior in the Japanese horseshoe crab, Tachypleus tridentatus. Zoological Science, 13: 151-159. DOI:10.2108/zsj.13.151 (  0) 0) |

Chabot C. C., Watson Ⅲ W. H.. 2010. Circatidal rhythms of locomotion in the American horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus: Underlying mechanisms and cues that influence them. Current Zoology, 56: 499-517. DOI:10.1093/czoolo/56.5.499 (  0) 0) |

Chabot, C. C., and Watson Ⅲ, W. H., 2014. Biological rhythms in intertidal animals. In: Annual, Lunar and Tidal Clocks Patterns and Mechanisms of Nature's Enigmatic Rhythms. Numata, H., and Helm, B., eds., Springer, New York, 41-64.

(  0) 0) |

Chabot C. C., Betournay S. H., Braley N. R., Watson Ⅲ W. H.. 2007. Endogenous rhythms of locomotion in the American horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 345: 79-89. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2007.01.009 (  0) 0) |

Chabot C. C., Kent J., Watson Ⅲ W. H.. 2004. Circatidal and circadian rhythms of locomotion in Limulus polyphemus. Biological Bulletin, 207: 72-75. DOI:10.2307/1543630 (  0) 0) |

Chabot C. C., Skinner S. J., Watson Ⅲ W. H.. 2008. Rhythms of locomotion expressed by Limulus polyphemus, the American horseshoe crab: Ⅰ. synchronization by artificial tides. Biological Bulletin, 215: 34-45. DOI:10.2307/25470681 (  0) 0) |

Cooke S. J.. 2008. Biotelemetry and biologging in endangered species research and animal conser-vation: Relevance to regional, national, and IUCN Red List threat assessments. Endangered Species Research, 4: 165-185. DOI:10.3354/esr00063 (  0) 0) |

General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, 2020. The gridded bathymetric data set (the GEBCO_2020 Grid). Available at: https://www.gebco.net/data_and_products/gridded_bathymetry_data/. Accessed 5th September 2021.

(  0) 0) |

James-Pirri M. J.. 2010. Seasonal movement of the American horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus in a semi-enclosed bay on Cape Cod, Massachusetts (USA) as determined by acoustic telemetry. Current Zoology, 56: 575-586. DOI:10.1093/czoolo/56.5.575 (  0) 0) |

Laurie, K., Chen, C. P., Cheung, S. G., Do, V., Hsieh, H., John, A., et al., 2019. Tachypleus tridentatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e. T21309A149768986, DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T21309A149768986.en.

(  0) 0) |

Lomb N. R.. 1976. Least-squares frequency analysis of unequally spaced data. Astrophysics and Space Science, 39: 447-462. DOI:10.1007/BF00648343 (  0) 0) |

Manca A., Mohamad F., Ahmad A., Sofa A. M., Ismail N.. 2017. Tri-spine horseshoe crab, Tachypleus tridentatus (L.) in Sabah, Malaysia: The adult body sizes and population estimate. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 10: 355-361. DOI:10.1016/j.japb.2017.04.011 (  0) 0) |

Mohamad, F., Ismail, N., Ahmad, A. B., Manca, A., Rahman, M. Z. F. A., Bahri, M. F. S., et al., 2015. The population size and movement of horseshoe crab (Tachypleus gigas Müller) on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. In: Changing Global Perspectives on Horseshoe Crab Biology, Conservation and Management. Carmichael, R. H., et al., eds., Springer, Heidelberg, 213-228.

(  0) 0) |

Mohamad F., Manca A., Ahmad A., Fawwaz M., Sofa A. M., Alia'm A. A., et al. 2016. Width-weight and length-weight relationships of the tri-spine horseshoe crab, Tachypleus tridentatus (Leach 1819) from two populations in Sabah, Malaysia: Implications for population management. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, 11: 1-13. (  0) 0) |

Mohamad R., Paul N. A., Isa N. S., Damanhuri J. H., Shahimi S., Pati S., et al. 2021. Using applied statistics for accurate size classification of the endangered Tachypleus tridentatus horseshoe crab. Journal of Ecological Engineering, 22(4): 273-282. DOI:10.12911/22998993/132432 (  0) 0) |

Naylor E.. 2010. Chronobiology of Marine Organisms. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 252pp.

(  0) 0) |

Nishii H.. 1975. Kabutogani-Jiten (Encyclopedia of the Horseshoe Crabs). Private publication, Kasaoka, 221pp.

(  0) 0) |

Palmer J. D.. 1976. An Introduction to Biological Rhythms. Academic Press, New York, 375pp.

(  0) 0) |

Ropert-Coudert Y., Beaulieu M., Hanuise N., Kato A.. 2009. Diving into the world of biologging. Endangered Species Research, 10: 21-27. DOI:10.3354/esr00188 (  0) 0) |

Sekiguchi K.. 1988. Biology of Horseshoe Crabs. Science House Co., Tokyo, 428pp.

(  0) 0) |

Sekiguchi, K., and Shuster Jr., C. N., 2009. Limits on the global distribution of horseshoe crabs (Limulacea): Lessons learned from two lifetimes of observations: Asia and America. Biology and conservation of horseshoe. In: Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. Tanacredi, J., et al., eds., Springer, Heidelberg, 5-24.

(  0) 0) |

Swan B. L.. 2005. Migrations of adult horseshoe crabs, Limulus polyphemus, in the middle Atlantic Bight: A 17-year tagging study. Estuaries, 28: 28-40. DOI:10.1007/BF02732751 (  0) 0) |

Thomas T. N., Watson Ⅲ W. H., Chabot C. C.. 2020. The relative influence of nature vs. nurture on the expression of circatidal rhythms in the American horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 649: 83-96. DOI:10.3354/meps13454 (  0) 0) |

Watanabe, S., Oyamada, S., Mizuta, K., Azumakawa, K., Morinobu, S., and Souji, N., 2022. Activity rhythm of the tri-spine horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus in the Seto Inland Sea, western Japan, monitored with acceleration data-loggers. In: International Horseshoe Crab Conservation and Research Efforts: 2007-2020. Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs Species Globally. Tanacredi, J. T., et al., eds., Springer, Heidelberg (in press).

(  0) 0) |

Watson W. H., Chabot C. C.. 2010. High resolution tracking of adult horseshoe crabs Limulus polyphemus in a New Hampshire Estuary using fixed array ultrasonic telemetry. Current Zoology, 56: 599-610. DOI:10.1093/czoolo/56.5.599 (  0) 0) |

Watson W. H., Johnson S. K., Whitworth C. D., Chabot C. C.. 2016. Rhythms of locomotion and seasonal changes in activity expressed by horseshoe crabs in their natural habitat. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 542: 109-121. DOI:10.3354/meps11556.ar (  0) 0) |

Yoda K., Naito Y., Sato K., Takahashi A., Nishikawa J., Ropert-Coudert Y., et al. 2001. A new technique for monitoring the behaviour of free-ranging Adélie penguins. Journal of Experimental Biology, 204: 685-690. DOI:10.1242/jeb.204.4.685 (  0) 0) |

Zar J. H.. 2010. Biostatistical Analysis. 5th edition. Prentice Hall/Pearson, NJ, 960pp.

(  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21