2) Fourth Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Beihai 536007, China;

3) South China Sea Institute of Planning and Environmental Research, Ministry of Natural Resources, Guangzhou 510310, China;

4) Key Laboratory of Exploration Technologies for Oil and Gas Resources, Ministry of Education, Yangtze University, Wuhan 430100, China

As a type of large igneous provinces, oceanic plateaus are underwater basaltic mountains with anomalously thick crust (Coffin and Eldholm, 1994). The size and volume of oceanic plateaus are on the order of millions of square kilometers and tens of millions of cubic kilometers, respectively, and dwarf almost all other igneous marine features (Ingle and Coffin, 2004). Oceanic plateaus typically form over the course of a few million years, and the rapid emplacement and high effusion of lava flows cause them to have low flank slopes of 1°-2° (Coffin and Eldholm, 1994). Oceanic plateaus account for 5% of the heat and mass flux from the Earth's mantle to its surface and are the surface expression of an integral part of mantle dynamics (Sleep, 1990).

Oceanic plateau formation is not readily explained by plate tectonics, and although some oceanic plateau formation models exist, none can explain all of their features without reservation (Foulger, 2007). One such model is the plume-head hypothesis, in which a bulbous plume head 800 km in diameter ascends from deep in the mantle until it melts at the base of the lithosphere (Richards et al., 1989; Duncan and Richards, 1991; Mahoney and Spencer, 1991; Coffin and Eldholm, 1994; Courtillot et al., 2003; Campbell and Davies, 2006). A thin conduit of magma, called the plume tail, follows the plume head and erupts with waning volcanic output (Duncan and Richards, 1991). This model is attractive because it explains the high volumes and emplacement rates that characterize oceanic plateaus as well as the age progressive island chains that are commonly seen appending them. The plume-head model also predicts that the plume's deep mantle origin carries rare platinum group elements to the crust, and that the plume's thermal buoyancy causes the volcanic construct to form in a sub-aerial environment. However, there are noticeable exceptions to this, namely the Ontong Java Plateau and Shatsky Rise, which show no signs of having ever been in a subaerial environment (Korenaga, 2005; Ingle and Coffin, 2004; Sager et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). Furthermore, core samples from Shatsky Rise do not exhibit expected chemical signature in keeping with a mantle plume source (Mahoney et al., 2005; Sano et al., 2012; Heydolph et al., 2014). Another widely accepted model is the plate model, in which mantle heterogeneities with anomalously low melting temperatures erupt at weak and fractured sections in the ocean crust (Foulger, 2007). The plate model is characterized by decompression melting of fertile upper mantle material. However, the plate model is still young currently and lacks an explanation for the large melt volumes and high emplacement rates characteristic of oceanic plateaus (Foulger, 2007).

Shatsky Rise, located in the northwest Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1), is the oldest and one of the largest oceanic plateaus (Coffin and Eldholm, 1994). It is comprised of three broad dome-like features (massifs) named Tamu, Ori, and Shirshov in which each features gentle slopes of 0.5°-1.5° and follows a northeast trend (Sager et al., 1999, 2013). Following the massifs is Papanin Ridge, a long volcanic ridge with the same northeast trend (Sager et al., 1999). In total, it covers an area of 5.33×105 km2 (Zhang et al., 2016). Unlike most oceanic plateaus, Shatsky Rise formed during a time of magnetic reversals, allowing the reconstruction of its tectonic evolution (Sager et al., 1988; Nakanishi et al., 1999). Tamu massif, the largest edifice within Shatsky Rise, formed first, followed by Ori massif, Shirshov massif, and finally Papanin Ridge. Magnetic anomalies show that volcanic emplacement was rapid (a few million years for each volcanic event) and followed the propagation of a ridge-ridge-ridge triple junction (Sager and Han, 1993; Nakanishi et al., 1999). Moreover, the separation between the Tamu, Ori, and Shirshov massifs as well as the progressive decrease in both size and age northeastward imply that each massif was created from episodic volcanism and the volcanic output decreased over time (Sager et al., 1999).

|

Fig. 1 Bathymetry and magnetic lineations of Shatsky Rise. Magnetic anomalies are shown as thick orange lines. Secondary cones selected from multibeam sonar data are shown as large spheroids. Secondary cones predicted by Hillier and Watts (2007) are shown as triangle. Secondary Cones on Shatsky Rise appear to have been emplaced randomly all over the flanks. They do not appear to have any obvious relation to local seafloor spreading. Heavy red tick marks denote the locations of large down-to-basin faults seen on the multichannel seismic profiles. The fault strikes are estimated from bathymetry data in this study. |

Although geophysical and geochemical observations over Shatsky Rise provide partial supports for either the plume or plate model hypotheses, neither can fully explain all observations. For example, bathymetric and magnetic data show the progressive formation of isolated volcanic edifices within Shatsky Rise, implying a transition from plume head to plume tail. Thick sheet basalts cored from IODP (Sager et al., 2010) and intrabasement structure imaged from multichannel seismic reflection (Sager et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015) indicate that highly effusive lava flows erupted from the volcano center and spread massively to the surrounding ocean basins. Ocean Bottom Seismometer (OBS) profiles reveal that the largest edifice within Shatsky Rise (Tamu massif) has a deep crustal root down to 30 km beneath the seafloor (Korenaga and Sager, 2012). These findings are consistent with the plume model that infers voluminous and rapid eruptions. In contrast, velocity model from OBS data suggests an unexpected negative correlation between the crustal thickness and velocity, interpreted as a chemical heterogeneity within colder, shallower mantle material (versus active thermal plume). IODP drilled basement rocks show geochemical and isotopic signatures similar to mid-ocean-ridge basalt (MORB), suggesting the formation by seafloor spreading analogous to mid-ocean ridges (Sano et al., 2012; Heydolph et al., 2014). The ridge-ridge-ridge triple junction setting of Shatsky Rise and the linear magnetic anomalies across Tamu and Ori massifs also favor the plate model (Sager et al., 1988; Nakanishi et al., 1999). Hence, neither the plume nor the plate model is a solid solution. Plume-ridge interaction is likely to be the answer but requires more investigations (Ito et al., 2003; Dordevic and Georgen, 2016; Zhang and Chen, 2017).

Besides large volcanoes (massifs), many small volcanic cones are observed within Shatsky Rise. Recently-collected bathymetry data show a number of conic features on the flanks of the massifs (Zhang et al., 2017). Additionally, modern seismic reflection data reveal several cones at the massif summits that are buried by sediments (Zhang et al., 2015). These cones are smaller in size and have steeper slopes in comparison to the massifs. Such discrepancies in morphology and structure imply that cones may be formed by different volcanism from the primary building of Shatsky Rise that constructed the high edfices. Dating of dredged basaltic samples from a topical cone around Toronto Ridge, a summit ridge atop Tamu massif, indicate a 15 Myr elapse postdating the massif basement (Heaton and Koppers, 2014), implying cones come from late-stage volcanism, namely secondary cones. Moreover, IODP drilled into a cone on the north flank of Tamu massif and found volcaniclastics (Sager et al., 2010), implying explosive volcanism and volcaniclastic formation as another significant type of late-stage volcanism atop Shatsky Rise. Despite robust viability, it is currently unknown what relation the secondary cones have to the triple junction. It is also unclear how many secondary cones actually exist on Shatsky Rise, how they are spatially distributed, or what similarities they might have with other seamounts in the oceans. One formation hypothesis for these cones is related to rifting during seafloor spreading or along rifted zones on the surface of large volcanoes (MacDonald and Abbott, 1970, 1983). This hypothesis seems to infer a link between cones and faults around Shatsky Rise. In this paper, we test this hypothesis by a comprehensive analysis of secondary cones in shape, population and distribution.

2 Data and MethodsWhile direct surveying of all seamounts is ideal, a complete bathymetric mapping of the ocean with all capable ships would take 200 years and cost billions of dollars (Smith and Sandwell, 2004). Because of this expense, 90% of the ocean remains uncharted at 1 arc-minute resolution, and only 25% of all identified seamounts have > 10% bathymetric coverage (Kim and Wessel, 2011). One method of mapping seamount distributions is by searching the typical bull-eye gravitational signature (Wessel, 2001). Because seamounts are small enough to rest on top of the lithosphere without sinking into the mantle, they form gravitational anomalies that resemble their topography (Dixon et al., 1983). This extra gravity attracts water toward it and forms tiny hills of water on the surface of the ocean (Dixon et al., 1983). In this sense, seafloor bathymetry can be predicted by running a geophysical inversion based on the topography of the surface of the ocean measured from satellites (Smith and Sandwell, 1997). However, this method does not work for large marine features, such as oceanic plateau, which are in isostatic equilibrium with the mantle, nor does it work for very deep features whose gravitational signatures are too greatly attenuated (Smith and Sandwell, 1997). Hillier and Watts (2007) offered another method of identifying seamounts. They searched all single beam bathymetric datasets for seamount shaped bathymetric anomalies. Although this method is able to detect deep seamounts as well as volcanic cones on oceanic plateaus, it is to some extend limited due to false positives over canyons, ridges, and abyssal hills.

We used a complied bathymetry dataset to observe secondary cones on Shatsky Rise. Multibeam sonar bathymetry data from two recent cruises (MGL1004 and MGL1206 cruises in 2010 and 2012, respectively, and both collected on the R/V Marcus G. Langseth by a Simrad-Kongsberg EM122 multi-beam echo sounder) were merged into the bathymetric dataset predicted from satellite altimetry (Smith and Sandwell, 1997) at 200 m horizontal resolution to create a gridded bathymetric dataset of Shatsky Rise. Because the thick sedimentary caps on top of Tamu, Ori, and Shirshov massifs are likely to bury any cones on their summits (Zhang et al., 2015; Clark et al., 2018), only the flanks were considered. The area of the surveyed region was calculated by multiplying the area of a single data point in the gridded bathymetry (200 m2) by the total number of data points. The total area surveyed (As) is 1.09×109 km2. Secondary cones were visually identified as approximately circular edifices with at least 50 m relief and 75% bathymetric coverage. We separated them from the rest of the bathymetry grid by taking only points inside a polygon that circumscribes their base. We found their axis of elongation by using a least-square fit to the data points of each cone, and constructed a cross-sectional profile along this line. We approximated each cone as a flat-topped cone by fitting the flanks with straight lines and connecting these lines with a horizontal top and bottom at the summit and base, respectively. Cone height (h) was calculated as the difference between the shallowest and deepest points. Summit diameter (Ds) was found as the horizontal distance between the two flanks at the summit, and basal diameter (Db) as the horizontal distance between the two flanks at the base. Secondary cone flatness (f) was calculated as f = Ds/Db. Slope (Φ) was calculated as the average slope of the two lines fitting the flanks.

The secondary cones found in single beam sonar data by Hillier and Watts (2007) were also used. However, only the height and coordinates of these cones were available. Depths of cones from Hiller and Watt's dataset were estimated by using bathymetry-derived ones from satellite altimetry (Smith and Sandwell, 1997). Both the manually selected cones and those identified by Hillier and Watts (2007) were used when finding the average height, but only the cones identified in this study were used when finding the average slope and flatness. Averages for these parameters are listed in Table 1 with uncertainties represented by ± one standard deviation.

|

|

Table 1 Morphologic statistic parameters of secondary cones within Shatsky Rise and comparison with seamounts in other oceans |

An exponential population model was used to fit the secondary cone population of Shatsky Rise. The exponential population model from Jordan et al. (1983) was given as v(H) = v0e−βH, where H is critical height in meters, v(H) is the total number of cones with height h < = H, v0 is the cone population density with units m-1, and β-1 is the characteristic height.

3 ResultsThe locations of all cones identified in this study are shown in Fig. 1, in which 51 cones are identified from our new multi-beam bathymetry data and 235 cones are predicted from the single beam bathymetry data by Hillier and Watts (2007). A particularly striking feature is the two parallel lines of large cones in the southeast corner of Tamu massif that intersect two similarly space magnetic anomalies at an angle (Fig. 2). Generally, the rest of the cones appear to be randomly distributed, and their positions do not appear to be related to the locations of major magnetic anomalies. Secondary cones appear to be distributed with rough uniformity along the flanks of the massifs and are absent from the massifs' summits because of thick sediment coverage (Zhang et al., 2015; Clark et al., 2018).

|

Fig. 2 Oblique perspective view of Tamu massif, Ori massif, Helios Basin, Toronto Ridge, cooperation seamounts and secondary cones. Note that secondary cones have steeper flank slopes and much smaller size than the massifs. Three enlargements show secondary cones with various shapes, from left to right, spiky, flat-topped, round with hummocky top. |

From a statistic of total 286 secondary cones over Shatsky Rise, their height, population density, characteristic height, mean flatness, mean slope and comparison with seamounts in other oceans are shown in Table 1. Heights of cones range from 102 to 1923 m and the characteristic height is 420 m. Both are close to those of the Pacific Ocean (Smith and Jordan, 1987, 1988; Abers et al., 1988; Benmis and Smith, 1993; Scheirer and Macdonald, 1995; Scheirer et al., 1996; Rappaport et al., 1997; Abers et al., 1998a), but significantly greater than those of the Atlantic Ocean (Smith and Cann, 1990, 1992; Magde and Smith, 1995). Population density of cones is 0.56 per thousand square kilometers. This number is underestimated because a number of cones are buried by sediments at the massif summits (Zhang et al., 2015; Clark et al., 2018). However, the number of buried cones is unclear due to limited seismic data for sub-sediment imaging over large areas of the massif summits. That is one of the reasons why Shatsky Rise has much less cone density than the Mid-Atlantic Rise (Smith and Cann, 1990, 1992; Magde and Smith, 1995) and the East Pacific Rise (Scheirer and Macdonald, 1995; Scheirer et al., 1996). Mean flatness of Shatsky Rise cones is 0.25 ± 0.20, which is slightly smaller than those of the Mid-Atlantic Rise and the East Pacific Rise. Meanwhile, mean slope of 6.1° ± 4.4° is obviously lower than those in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Fig. 3 shows a histogram of secondary cone heights with bins of 100 m. The secondary cone population of Shatsky Rise fits the exponential population model suggested by Jordan et al. (1983). The population constants v0 and β-1 are found by finding the line that best fits the natural log of the secondary cone height count (Fig. 4). These constants are listed in Table 1. Multiplying v0 by the area of Shatsky Rise yields a total of 286 secondary cones, which equals to the number observed from bathymetry.

|

Fig. 3 Histogram of secondary cone heights with 100 m wide bins. The plot shows that the sample population of secondary cones has a highly exponential population size frequency. |

|

Fig. 4 Constants v0 and β-1 were found by approximating the log of the secondary cone counts with a best fitting line. |

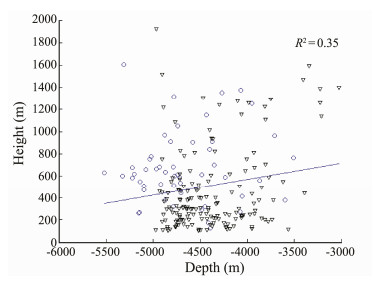

Secondary cones located closer to the summit of a massif have a shallower depth than does a cone located at a massif's base. Depth is used to represent a secondary cone's distance from the base of a massif in Fig. 5. There is a considerable scatter in the heights of secondary cones with respect to depth, implying that secondary cones of any height may form at any position on the flanks of the massifs.

|

Fig. 5 Secondary cone height is plotted as a function of distance from the base of the massif (represented by depth). The weak relation suggests that magma bodies are probably not located beneath the plateaus crustal root. |

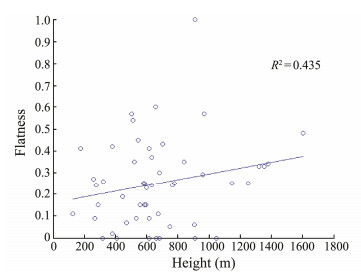

Cone flatness is plotted as a function of height in Fig. 6. The plot shows cone flatness to be generally scattered. The relationship between flatness and height is weak, and 43% of the increase in secondary cone flatness can be described by an increase in height.

|

Fig. 6 Secondary cone flatness is plotted as a function of height. The weak relationship suggests that the magma bodies cannot provide enough magma to enable the cone to reach its critical height. |

Secondary cones are apparently different from oceanic plateaus in size, shape, distribution, and abundance (Figs. 1 and 2). A clear understanding of the distribution of secondary cones and their morphologies is important because they are the surface expressions of poorly understood latestage volcanism and mantle processes. We conduct a census of Shatsky Rise's secondary cone population from available bathymetry data and estimate that 286 secondary cones exist on Shatsky Rise, allowing a qualitative investigation into the shape and distribution of the secondary cones (Table 1). Implications for the formation conditions of the secondary cones are found by their bathymetric characteristics as well as comparing their morphology statistics to those of better-understood analogues, such as seamounts found in intraplate and near-ridge settings.

One of our goals in this paper is to test whether secondary cones are related to rifting during seafloor spreading due to Shatsky Rise's mid-ocean ridges triple junction setting. The secondary cones, nevertheless, do not appear to have preferential orientation with the magnetic lineations, implying that they did not form from seafloor spreading. Together with the orientation of the basement faults parallel to Shatsky Rise's contours rather than the magnetic lineations (Fig. 1), this suggests that seafloor spreading had little influence if any on Shatsky Rise's late-stage volcanic and tectonic environments. One apparent exception is Cooperation Seamounts in the Helios Basin between the Tamu and Ori massifs. They appear to be linear volcanoes following the basin axis and parallel to the magnetic lineations, which would be expected to be formed by seafloor spreading as the volcanoes might occur with the splitting of the Tamu and Ori massifs by rifting. However, seismic data show few rifting-related faults in the Helios Basin, implying that it is not a rift basin but a gap between two massive volcanic eruptions (Zhang et al., 2015). No large normal faults cutting the volcano's edges are found in the seismic profile, implying that Cooperation Seamounts are not associated with seafloor spreading. Instead, they are small volcanic pulses between the two large volcanoes (i.e., the Tamu and Ori massifs). Their morphology is similar to other secondary cones within Shatsky Rise. It may well be that they also result from late-stage volcanism.

Another interesting point is that Shatsky Rise cones feature a lower average slope than other seamounts. One possible explanation is that the magma that formed the secondary cones was more effusive than those of the seamounts in other studies. High effusion rates are thought to be responsible for the gentle slopes of Shatsky Rise proper (Sager et al., 2010, 2013). Perhaps as the main volcanic episode wound down, secondary cones were emplaced in a final burst with effusion rates that are lower than Shatsky Rise proper, but still higher than those in most ocean ridge environments.

Seamounts occur at ocean ridge settings that connect with magma bodies emplaced in the newly formed seafloor (Madge and Smith, 1995). Seamounts with less height are typically found on thin seafloor, while larger seamounts are found in thicker oceanic crust (Kim and Wessel, 2011). This suggests that cones located higher on the flanks of the massifs should be taller than those located at lower positions due to the extra weight of the massif pressing down on the magma body. If this is true for Shatsky Rise, Fig. 5 would show a strong positive correlation between depth and cone height; however, this is not the case. It is possible that the cones formed from residual bodies of magma are located at random positions inside the massifs. Although if this is indeed the case, it is unclear how these residual magma bodies could have stayed molten after the massif had crystallized. Perhaps they could have a different composition from the rest of the massif, giving them a lower melting point and higher viscosity. This might be possible if the plume head were to carry with it either mantle heterogeneities or pieces of lithosphere during its ascent.

Barone and Ryan (1990) suggest that one way by which seamounts can become flat without undergoing subaerial is that after a critical height is reached (determined by magma pressure, composition and volatile content), magma emanating from a generally pointy seamount will build outward and create a flat top. This assumes that the body supplying the magma is large enough for the seamount to reach its critical height. If this scenario occurs on Shatsky Rise, the secondary cones should show either a positive correlation between height and flatness, or that small and large cones center on their own respective mean flatness. Fig. 6 shows that neither scenario is the case. There is a great deal of scatter in the plot, and it appears that on Shatsky Rise flatness and height may only be very weakly related. Cones with heights less than 1000 m (82% of the cones with measured flatness) feature flatness with considerable scatter. It is possible that the cones of Shatsky Rise do not reach their critical height, implying that the magma bodies that feed the cones are volume limited. Another interpretation is that the magma bodies' physical parameters at such critical height are much greater than other at locations. In addition, Madge and Smith (1995) found that seamounts on the mid-Atlantic Ridge became both taller and more flat as they approached the Icelandic hotspot and credited this trend to the greater supply of magma from the hotspot. The characteristic height of the cones in this study (420 m) is greater than that of the seamounts close to the Icelandic hotspot (68 m).

5 ConclusionsThis study provides a quantitative and statistic analysis on the volcanic cones and implications for late-stage volcanism atop an immense oceanic plateau, Shatsky Rise in the northwest Pacific Ocean as the world's third largest. The late-stage output of volcanic cones on Shatsky Rise does not resemble the volcanic conditions seen at midocean ridges. This seems to be the case for mid-ocean ridges of all types, regardless of the rates at which they spread (EPR, fast; MAR, slow) or whether or not they are in the proximity of hotspot activity (Iceland). Volcanoes that form at mid-ocean ridges are more densely populated than the secondary cones of Shatsky Rise, and tend to have steeper slopes. There is no clear evidence that supports the seafloor spreading that occurred at Shatsky Rise and had an important effect on the emplacement or formation of the cones. The volcanic cones do not increase in height as they get closer to the summits of the massifs as the increase in hydraulic pressure would suggest. Week relationship between cone height and flatness implies that limited remaining magma supply after main-stage eruptions could not feed the late-stage volcanoes to reach their critical height.

AcknowledgementsWe thank William W. Sager, Jun Korenaga, the Captain, crew, and technical staff of the R/V Marcus G. Langseth for assisting in collection of geophysical data during two cruises. We thank William J. Durkin and Chris F. Paul for helping with the multi-beam sonar acquisition, data processing and figure plotting. This research was supported by the National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2018YFC0309800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 91628301, U1606401, 41606069, 41776058), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province in China (No. 2017A030313243), the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Nos. Y4SL021001, QYZDY-SSWDQC005) and the China Association of Marine Affairs (No. CAMAZD201714).

Abers, G. A., Parsons, B. and Wessel, J. K., 1988. Seamount abundances and distributions in the southeast Pacific. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 871: 137-151. (  0) 0) |

Barone, A. M. and Ryan, W. B., 1990. Single plume model for asynchronous formation of the Lamont Seamounts and adjacent East Pacific Rise terrains. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 95(B7): 10801-10827. DOI:10.1029/JB095iB07p10801 (  0) 0) |

Benmis, K. G. and Smith, D. K., 1993. Production of small volcanoes in the Superswell region of the South Pacific. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 118: 251-262. DOI:10.1016/0012-821X(93)90171-5 (  0) 0) |

Campbell, I. H. and Davies, G. F., 2006. Do mantle plumes exist. Episodes, 29(3): 162-168. DOI:10.18814/epiiugs/2006/v29i3/001 (  0) 0) |

Clark, R. W., Sager, W. W. and Zhang, J., 2018. Seismic stratigraphy of the Shatsky Rise sediment cap, northwest Pacific, and implications for pelagic sedimentation atop submarine plateaus. Marine Geology, 397: 43-59. DOI:10.1016/j.margeo.2017.11.019 (  0) 0) |

Coffin, M. F. and Eldholm, O., 1994. Large igneous provinces: Crustal structure, dimensions, and external consequences. Reviews of Geophysics, 321: 1-36. (  0) 0) |

Courtillot, V., Davaille, A., Besse, J. and Stock, J., 2003. Three distinct types of hotspots in the Earth's mantle. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2053: 295-308. (  0) 0) |

Dixon, T. H., Naraghi, M., McNutt, M. K. and Smith, S. M., 1983. Bathymetric prediction from Seasat altimeter data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 88(C3): 1563-1571. DOI:10.1029/JC088iC03p01563 (  0) 0) |

Dordevic, M. and Georgen, J., 2016. Dynamics of plume-triple junction interaction: Results from a series of three-dimensional numerical models and implications for the formation of oceanic plateaus. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 121: 1316-1342. DOI:10.1002/2014JB011869 (  0) 0) |

Duncan, R. A. and Richards, M. A., 1991. Hotspots, mantle plumes, flood basalts, and true polar wander. Reviews of Geophysics, 291: 31-50. (  0) 0) |

Foulger, G. R., 2007. The 'plate' model for the genesis of melting anomalies. Special Paper of the Geological Society of America, 430: 1. (  0) 0) |

Heaton, D. E., and Koppers, A. A., 2014. Constraining the rapid construction of Tamu massif at a 145 Myr old triple junction, Shatsky Rise. Goldschmidt International Geochemistry Conference. Sacramento, 4093.

(  0) 0) |

Heydolph, K., Murphy, D. T., Geldmacher, J., Romanova, I. V., Greene, A., Hoernle, K., Weis, D. and Mahoney, J., 2014. Plume versus plate origin for the Shatsky Rise oceanic plateau (NW Pacific): Insights from Nd, Pb and Hf isotopes. Lithos, 200-201: 49-63. DOI:10.1016/j.lithos.2014.03.031 (  0) 0) |

Hillier, J. K. and Watts, A. B., 2007. Global distribution of seamounts from ship-track bathymetry data. Geophysical Research Letters, 34(13): 173-180. (  0) 0) |

Ingle, S. and Coffin, M. F., 2004. Impact origin for the greater Ontong Java Plateau. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2181: 123-134. (  0) 0) |

Ito, G., Lin, J. and Graham, D., 2003. Observational and theoretical studies of the dynamics of mantle plume-Mid-ocean ridge interaction. Reviews of Geophysics, 77: 1041-1042. (  0) 0) |

Jordan, T. H., Menard, H. W. and Smith, D. K., 1983. Density and size distribution of seamounts in the eastern Pacific inferred from wide-beam sounding data. Journal of Geophysical Research, 88: 10508-10518. DOI:10.1029/JB088iB12p10508 (  0) 0) |

Kim, S. S. and Wessel, P., 2011. New global seamount census from altimetry-derived gravity data. Geophysical Journal International, 1862: 615-631. (  0) 0) |

Kleinrock, M. C. and Brooks, B. A., 1994. Construction and destruction of volcanic knobs at the Cocos-Nazca Spreading System near 95°W. Geophysical Research Letters, 2121: 2307-2310. (  0) 0) |

Korenaga, J., 2005. Why did not the Ontong Java Plateau form subaerially. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 234: 385-399. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.03.011 (  0) 0) |

Korenaga, J. and Sager, W. W., 2012. Seismic tomography of Shatsky Rise by adaptive importance sampling. Journal of Geophysical Research, 117: 70-83. (  0) 0) |

MacDonald, G. A., and Abbott, A. T., 1970. Volcanoes in the Sea. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1-441.

(  0) 0) |

MacDonald, G. A. and Abbott, A. T., 1983. The Geology of Hawaii: Volcanoes in the Sea. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1-505.

(  0) 0) |

Magde, L. S. and Smith, D. K., 1995. Seamount volcanism at the Reykjanes Ridge: Relationship to the Iceland hot spot. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 100(B5): 8449-8468. DOI:10.1029/95JB00048 (  0) 0) |

Mahoney, J. J., Duncan, R. A., Tejada, M. L. G., Sager, W. W. and Bralower, T. J., 2005. Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary age and mid-ocean-ridge type mantle source for Shatsky Rise. Geology, 333: 185-188. (  0) 0) |

Mahoney, J. J. and Spencer, K. J., 1991. Isotopic evidence for the origin of the Manihiki and Ontong Java oceanic plateaus. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 104: 196-210. DOI:10.1016/0012-821X(91)90204-U (  0) 0) |

Nakanishi, M., Sager, W. W. and Klaus, A., 1999. Magnetic lineations within Shatsky Rise, northwest Pacific Ocean: Implications for hot spot-triple junction interaction and oceanic plateau formation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 104(B4): 7539-7556. DOI:10.1029/1999JB900002 (  0) 0) |

Rappaport, Y., Naar, D. F., Barton, C. C., Liu, Z. J. and Hey, R. N., 1997. Morphology and distribution of seamounts surrounding easter island. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 102(B11): 24713-24728. DOI:10.1029/97JB01634 (  0) 0) |

Richards, M. A., Duncan, R. A. and Courtillot, V. E., 1989. Flood basalts and hot-spot tracks: Plume heads and tails. Science, 246(4926): 103-107. DOI:10.1126/science.246.4926.103 (  0) 0) |

Sager, W. W. and Han, H. C., 1993. Rapid formation of the Shatsky Rise oceanic plateau inferred from its magnetic anomaly. Nature, 364(6438): 610-613. DOI:10.1038/364610a0 (  0) 0) |

Sager, W. W., Handschumacher, D. W., Hilde, T. W. C. and Bracey, D. R., 1988. Tectonic evolution of the northern Pacific Plate and Pacific-Farallon-Izanagi triple junction in the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous (M21-M10). Tectonophysics, 155: 345-364. DOI:10.1016/0040-1951(88)90274-0 (  0) 0) |

Sager, W. W., Kim, J., Klaus, A., Nakanishi, M. and Khankishieva, L. M., 1999. Bathymetry of Shatsky Rise, northwest Pacific Ocean: Implications for ocean plateau development at a triple junction. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 104(B4): 7557-7576. DOI:10.1029/1998JB900009 (  0) 0) |

Sager, W. W., Sano, T., Geldmacher, J., and the Expedition 324 Scientists, 2010. Proceedings of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, Volume 324. Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Management International, Inc., Tokyo, 1-68.

(  0) 0) |

Sager, W. W., Zhang, J., Korenaga, J., Sano, T., Koppers, A. A. P., Mahoney, J. and Widdowson, M., 2013. An immense shield volcano within Shatsky Rise oceanic plateau, northwest Pacific Ocean. Nature Geoscience, 10: 1-6. (  0) 0) |

Sano, T., Shimizu, K., Ishikawa, A., Senda, R., Chang, Q., Kimura, J. I., Widdowson, M. and Sager, W. W., 2012. Variety and origin of magmas on Shatsky Rise, northwest Pacific Ocean. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems, 13: 34-47. (  0) 0) |

Scheirer, D. S. and Macdonald, K. C., 1995. Near-axis seamounts on the flanks of the East Pacific Rise, 8°N to 17°N. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 100(B2): 2239-2259. DOI:10.1029/94JB02769 (  0) 0) |

Scheirer, D. S., Macdonald, K. C., Forsyth, D. W. and Shen, Y., 1996. Abundant seamounts of the Rano Rahi seamount field near the southern East Pacific Rise, 15°S to 19°S. Marine Geophysical Researches, 181: 13-52. (  0) 0) |

Sleep, N. H., 1990. Hotspots and mantle plumes: Some phenomenology. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 95(B5): 6715-6736. DOI:10.1029/JB095iB05p06715 (  0) 0) |

Smith, D. K. and Cann, J. R., 1992. The role of seamount volcanism in crustal construction at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge 24°-30°N. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 97(B2): 1645-1658. DOI:10.1029/91JB02507 (  0) 0) |

Smith, D. K. and Cann, J. R., 1990. Hundreds of small volcanoes on the median valley floor of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at 24°-30°N. Nature, 348(6297): 152-155. DOI:10.1038/348152a0 (  0) 0) |

Smith, D. K. and Jordan, T. H., 1987. The size distribution of Pacific seamounts. Geophysical Research Letters, 1411: 1119-1122. (  0) 0) |

Smith, D. K. and Jordan, T. H., 1988. Seamount statistics in the Pacific Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 93(B4): 2899-2918. DOI:10.1029/JB093iB04p02899 (  0) 0) |

Smith, W. H. and Sandwell, D. T., 1997. Global sea floor topography from satellite altimetry and ship depth soundings. Science, 277(5334): 1956-1962. DOI:10.1126/science.277.5334.1956 (  0) 0) |

Smith, W. H. and Sandwell, D. T., 2004. Conventional bathymetry, bathymetry from space, and geodetic altimetry. Oceanography, 17(1): 8-23. DOI:10.5670/oceanog.2004.63 (  0) 0) |

Wessel, P., 2001. Global distribution of seamounts inferred from gridded Geosat/ERS-1 altimetry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 106(B9): 19431-19441. DOI:10.1029/2000JB000083 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, J. and Chen, J., 2017. Geophysical implications for the formation of the Tamu massif-The Earth's largest single volcano-within the Shatsky Rise in the northwest Pacific Ocean. Science Bulletin, 62: 69-80. DOI:10.1016/j.scib.2016.11.003 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, J., Sager, W. W. and Durkin, W. J., 2017. Morphology of Shatsky Rise oceanic plateau from high resolution bathymetry. Marine Geophysical Research, 38: 1-17. DOI:10.1007/s11001-017-9308-5 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, J., Sager, W. W. and Korenaga, J., 2015. The Shatsky Rise oceanic plateau structure from two-dimensional multichannel seismic reflection profiles and implications for oceanic plateau formation. Special Paper of the Geological Society of America, 511: 103-126. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, J., Sager, W. W. and Korenaga, J., 2016. The seismic Moho structure of Shatsky Rise oceanic plateau, northwest Pacific Ocean. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 441: 143-154. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.02.042 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18